1. Introduction

Heart failure (HF) represents one of the chronic conditions with the greatest global health and economic impact. It is estimated to affect approximately 60 to 64.3 million people worldwide [

1,

2]. This prevalence exhibits marked variability in epidemiological studies, significantly increasing with age and exceeding 10% in individuals over 70 years old and 14% in those over 75 years old [

3,

4,

5,

6].

Beyond its clinical consequences, HF imposes a considerable economic burden on healthcare systems. HF remains the leading cause of hospitalization in patients aged 65 years or older. Furthermore, it is recognized as the third leading cause of cardiovascular mortality, contributing up to 20% of deaths from this cause. Compounding this situation, annual rehospitalization rates for HF patients can reach up to 50%. Each new hospitalization not only severely deteriorates patients’ quality of life but also independently increases the risk of mortality by 20%. This hospitalization-mortality cycle represents a critical vulnerability in the current HF care pathway. The high rate of rehospitalizations, often triggered by acute HF decompensation, is a key factor contributing to the economic burden and morbidity of the disease. Recent data from Spain confirm this burden, with in-hospital mortality and readmission rates remaining alarmingly high despite advances in pharmacological treatment [

7].

Despite this reality, a significant proportion, nearly 40%, of patients are discharged prematurely after an HF hospitalization [

8]. This situation highlights a critical discontinuity in the continuum of care, suggesting that existing discharge criteria, patient education, or post-discharge support mechanisms are often insufficient to prevent early adverse events, including symptomatic worsening or rehospitalizations. The current system’s inability to effectively manage patients after discharge results in a considerable financial burden on healthcare systems, as recurrent hospitalizations are costly. More importantly, it imposes a profound human cost, leading to repeated deterioration in patients’ quality of life and increased mortality. This precarious situation creates an urgent need to implement additional and more effective measures for the outpatient follow-up of HF patients. Robust outpatient monitoring is crucial to bridge the gap between acute hospital care and stable long-term management, with the ultimate goal of reducing rehospitalizations, improving patient quality of life, and lowering overall healthcare costs.

In this context, lung ultrasound (LUS) has rapidly emerged as a non-invasive, fast, and accurate tool for recognizing and monitoring pulmonary congestion in patients with heart failure for detecting pulmonary congestion, primarily through the identification of B-lines [

9,

10]. The utility of LUS extends beyond initial diagnosis; it is increasingly used to guide diuretic therapy, monitor congestion resolution during treatment, and predict adverse outcomes. Its diagnostic and prognostic value in the outpatient setting has been supported by studies showing strong correlation with natriuretic peptides and echocardiographic parameters [

11,

12]. Its bedside applicability is well established in various settings, including emergency departments, critical care units, and outpatient clinics [

13,

14]. LUS offers a unique opportunity to shift the paradigm of HF management from reactive (treating overt decompensation) to proactive (preventing decompensation). By enabling the detection of subclinical pulmonary congestion, LUS is a substantial improvement over subjective clinical assessment [

15]. However, international clinical practice guidelines on heart failure still do not incorporate standardized interpretation criteria for the predictive value of B-lines [

16,

17]. Challenges persist for its widespread adoption and consistent application, including operator dependency, variability in B-line interpretation, equipment differences, and the inherent difficulty in distinguishing overlapping pulmonary conditions. Consequently, physician adoption and interpretation of LUS findings remain suboptimal.

In parallel with advances in imaging modalities, the HEFESTOS score has been validated in several European countries as a useful predictive model in primary care for stratifying the risk of death or hospitalization within 30 days post-cardiac decompensation [

18]. A key strength of the HEFESTOS score lies in its reliance on clinical variables that are easily accessible and obtainable in a community setting, making it highly practical for routine use in primary care. The score’s primary utility lies in its ability to guide clinical decision-making by providing a quantitative, evidence-based assessment of short-term prognosis for patients experiencing HF decompensation in the primary care setting. This addresses a critical unmet need in primary care: the ability to quickly identify patients at high risk of adverse outcomes immediately following a decompensation event.

Currently, there is a significant gap in scientific evidence regarding the efficacy of B-lines (detected by LUS) as a hospital discharge criterion in patients admitted for decompensated HF or in outpatient follow-up [

13,

14]. Similarly, the prognostic relevance of combining B-lines with other clinical scores, such as the HEFESTOS score, in monitoring HF patients is unknown. Furthermore, there is a notable absence of specific indications or guidelines for leveraging the predictive value of their combined use in guiding outpatient therapeutic interventions during HF decompensation episodes. This lack of evidence on combining LUS (an objective physiological measure of congestion) and HEFESTOS (a clinical risk score based on historical and clinical factors) suggests that an opportunity for a more comprehensive and nuanced risk assessment is being missed. The potential of combining multiparametric ultrasound strategies with clinical scores to improve risk stratification in HF has been recently highlighted in outpatient cohorts [

19].

This study proposes to evaluate the efficacy of this combined use of LUS and the HEFESTOS score during primary care follow-up will reduce the combined risk of symptomatic worsening and/or adverse events in heart failure patients.

This study aimed to analyze the characteristics and clinical course of patients diagnosed with HF through the combined use of the HEFESTOS score and LUS. Specifically, we sought to (1) evaluate the prognostic utility of the HEFESTOS score beyond the 30-day follow-up period; (2) analyze the prognostic significance of LUS findings during HF follow-up; and (3) determine the concordance between the degree of pulmonary congestion detected by LUS and the HEFESTOS-based risk stratification for hospitalization or death.

2. Materials and Methods

This study is designed as an observational, prospective cohort study with a longitudinal and analytical approach. It involves the systematic follow-up of a group of patients over time, allowing for the recording and analysis of clinical outcomes and their association with baseline characteristics and diagnostic tools applied at the outset. The main objective was to evaluate the combined use of the HEFESTOS score and lung ultrasound for managing HF patients in an outpatient setting. The primary outcome measured was HF decompensation, which was defined as worsening symptoms requiring medical attention, emergency care, hospitalization, or death.

At inclusion, each patient underwent a baseline assessment that included the application of the HEFESTOS risk calculator and a LUS (LUS) examination. Follow-up was carried out through regular review of electronic health records (EHRs) to identify episodes of heart failure decompensation, including primary care consultations, emergency department visits, hospital admissions, and deaths.

2.1. Setting

The study was conducted at the “EAP Tortosa-Est – CAP El Temple” primary care center, part of the public healthcare network of the Spanish National Health System, managed by the Institut Català de la Salut (ICS) within the Catalan Health System (CatSalut). This center is located in the city of Tortosa and provides healthcare to a predominantly urban population. An EAP (Equip d’Atenció Primària) is a functional unit of the Catalan public health system, composed of a multidisciplinary team of healthcare professionals.

Tortosa is situated in the southernmost region of Catalonia, known as

Terres de l’Ebre. Terres de l’Ebre is characterized by a markedly aging population, with the highest aging index in Catalonia (174.0), compared to the Catalan average (142.6) [

20] and the Spanish average (142.3) [

21]. Furthermore, the average income per inhabitant in the region represents only 78.1% of the Catalan average, reflecting notable socioeconomic disparities [

22].

2.2. Inclusion Criteria

Age ≥ 18 years. Participants had to be adults, defined as individuals aged 18 years or older at the time of inclusion in the study, to ensure legal capacity for providing informed consent and to reflect the typical age range of heart failure patients managed in primary care.

Documented diagnosis of heart failure. Only patients with a confirmed diagnosis of heart failure recorded in their electronic health records were eligible. This included both heart failure with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF) and heart failure with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF), as coded using standard ICD-10 classifications. All patients were required to have undergone a transthoracic echocardiogram to support diagnosis and classification, following the diagnostic criteria established by the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) guidelines [

23].

Ability to provide informed consent. Participants had to demonstrate sufficient cognitive and communicative capacity to understand the nature and objectives of the study, and to voluntarily agree to participate by signing an informed consent form.

Patients with a documented diagnosis of heart failure, coded using standard ICD-10 classifications, were identified through a review of electronic health records. Those who met the inclusion criteria were subsequently contacted by telephone and invited to participate in the study on a voluntary basis.

2.3. Exclusion Criteria

Patients enrolled in the ATDOM (home care) program. These individuals typically present with significant functional dependence, complex chronic conditions, or severe mobility limitations that prevent regular attendance at the primary care center. Although portable ultrasound devices were available, these patients were excluded due to the clinical and logistical complexity of ensuring consistent follow-up.

Patients identified as MACA (

Malaltia Crònica Avançada) according to the criteria established by the Catalan Health Department [

24]. These patients present advanced chronic conditions with limited life expectancy, high clinical complexity, and are primarily candidates for palliative care rather than active monitoring of decompensation risk.

Refusal to participate or inability to provide informed consent (e.g., cognitive impairment without a legal representative).

2.4. Study Period

The inclusion of patients in the cohort was carried out progressively between April 2023 and April 2025, alongside routine clinical practice at the EAP Tortosa-Est primary care center. Each patient underwent an initial assessment with LUS and the HEFESTOS risk calculator at the time of inclusion. In 2025, electronic health records were reviewed retrospectively to identify the first episode of HF decompensation occurring after each patient’s inclusion in the study. Patients without any recorded decompensation were followed administratively up to April 2025.

2.5. Informed Consent

All participants provided written informed consent prior to their inclusion in the study. The study protocol was reviewed and approved by the Clinical Research Ethics Committee of IDIAP Jordi Gol (reference 22/143P). Participants were informed about the objectives, procedures, potential risks, and benefits of the study, and their right to withdraw at any time without affecting the quality of their medical care.

2.6. Variables Collected

Several clinical and diagnostic variables were recorded for each patient at baseline and during follow-up, with the aim of characterizing the cohort and identifying potential predictors of HF decompensation:

Sociodemographic and clinical characteristics: Age and sex were recorded, as well as the etiology of HF (underlying cause, such as ischemic heart disease or hypertension) and the type of heart failure (HFrEF or HFpEF), as documented in the electronic health record. The baseline evaluation for the study, including LUS and HEFESTOS score calculation was performed on the date of each patient’s inclusion.

Lung Ultrasound (LUS) Score: The main ultrasonographic marker of pulmonary congestion is the B-line, a vertical hyperechoic artifact that originates at the pleural line and extends down to the bottom of the screen without fading, moving synchronously with respiration. These artifacts are generated by the reverberation of ultrasound waves at air-fluid interfaces in the lung, typically in the setting of interstitial edema. In this study, the chest was examined following a standardized 28-zone protocol [

25], scanning anterior, lateral, and posterior regions of both lungs. The total number of B-lines observed across all zones was used to quantify pulmonary congestion and assign a LUS score, which was classified into three categories: mild (0–14 B-lines), moderate (15–29 B-lines), and severe congestion (≥30 B-lines). A detailed description of the LUS scanning protocol, including patient positioning, probe type, scanning technique, and B-line grading criteria, is provided in

Table 1.

HEFESTOS Risk Score: HEFESTOS score is a validated clinical tool used to estimate the short-term (30-day) risk of HF decompensation [

18]. It is based on 8 variables related to the patient’s symptoms, vital signs, and treatment at the time of consultation: gender; history of hospital admission due to HF within the past year (yes or no); heart rate (≤100 or >100 beats per minute); presence of pulmonary crackles on auscultation (yes or no); paroxysmal nocturnal dyspnea (yes or no); orthopnea (yes or no); New York Heart Association (NYHA) functional class (I or II vs. III or IV); dyspnea as the main reason for the medical encounter (yes or no); and oxygen saturation measured by pulse oximetry (≤90% or >90%). Each item scores 1 point, with a maximum total of 8 points. Based on the total score, patients are stratified into three risk categories—low risk (0–3 points), with an estimated 30-day risk of decompensation <5%; moderate risk (4–7 points), with an estimated risk of 5–20%; and high risk (>7 points), with an estimated risk >20%—as shown in

Table 2.

Heart failure decompensation: HF decompensation is defined as a clinical worsening of a previously stable patient, usually due to fluid overload, increased pulmonary or systemic congestion, or inadequate cardiac output. These episodes typically require a change in medical management or healthcare utilization. In this study, decompensation was identified through retrospective review of electronic health records and included any of the following events occurring after the date of inclusion:

Consultations in primary care for symptoms consistent with HF worsening (e.g., dyspnea, orthopnea, weight gain, peripheral edema).

Emergency department visits where HF was noted as the main reason for consultation or part of the diagnostic impression.

Hospital admissions with a primary or secondary diagnosis of HF decompensation, coded according to standard ICD-10 classifications.

All-cause mortality, whether related or unrelated to HF, as recorded in the health system database.

Only the first decompensation event per patient after their inclusion was considered for analysis, in line with the study’s objective of evaluating predictive tools at baseline.

3. Results

A total of 107 patients with HF (HF) were included. The mean age was 77.3 years, and 55.1% were male. HF with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF) was more frequent (55.1%) than with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF) (45.8%). The main etiologies were hypertension (62,06%), arrhythmias (44,94%), and ischemic heart disease (24,61%). A detailed overview of the participants’ demographic and clinical characteristics is presented in

Table 3.

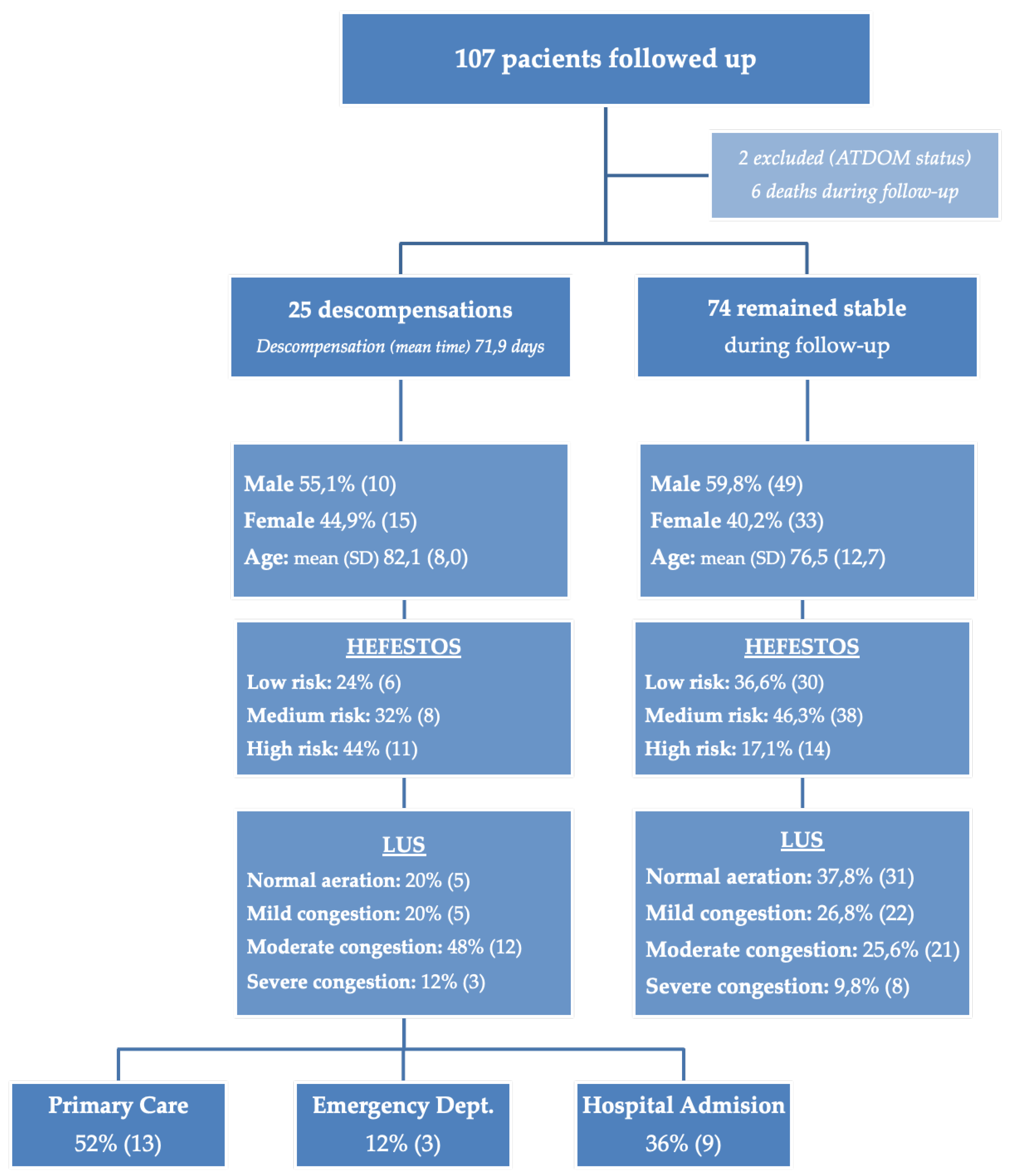

During the follow-up period, 25 patients (23.36%) experienced cardiac decompensation (

Figure 1). This included 16.9% of men (95% CI: 6.52%–27.27%) and 31.2% of women (95% CI: 17.09%–45.4%). No statistically significant differences were observed between sexes (p = 0.131).

In the initial evaluation, according to the HEFESTOS score, 36 patients (33.6%) were classified as low risk, 46 (43.0%) as medium risk, and 25 (23.4%) as high risk. Regarding the initial LUS assessment, 36 patients (33.6%) showed an aerated lung pattern, 27 (25.2%) presented a mild interstitial pattern, 33 (30.8%) had a moderate interstitial pattern, and 11 patients (10.3%) displayed a severe interstitial pattern. A summary of the risk stratification based on HEFESTOS and the initial LUS findings is provided in

Table 4.

To evaluate the agreement between HEFESTOS risk classification and LUS findings, both tools were dichotomized clinically: HEFESTOS into “Low risk” and “Medium–high risk”, and LUS into “Normal Aereation and Mild congestión” and “Moderate and severe congestion” (

Table 5). The unweighted Cohen’s Kappa index yielded a value of 0.456 (95% CI: 0.315–0.597; p < 0.001), indicating a moderate level of agreement between the two tools. The predictive power of using both scores is statistically significant (p = 0.005), with their primary utility being in the stratification of low-risk individuals.

The area under the curve (AUC) was 0.677 (95% CI: 0.552–0.801; p < 0.005), demonstrating moderate discriminative capacity. Sensitivity was 81.7% (95% CI: 72.7–90.7), specificity 63.9% (95% CI: 48.2–79.6), positive predictive value 81.7%, and negative predictive value 63.9%, with the same confidence intervals. The correlation between the total LUS score and the HEFESTOS scale was also assessed, showing a Pearson correlation coefficient of 0.489, a Spearman rank correlation of 0.514, and an intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) of 0.390 — suggesting a low to moderate correlation between the two continuous measures.

In the group of 25 patients with decompensated HF, a significant association was observed between LUS findings and the HEFESTOS risk score. Among the 10 patients with an aerated or mild pattern on LUS, 6 were classified as low risk by HEFESTOS and 4 as moderate or high risk. Conversely, all 15 patients with a moderate or severe LUS pattern were categorized as moderate or high risk according to HEFESTOS. This corresponded to a sensitivity of 78.95% (95% CI: 60.62–97.28) and a specificity of 100% (95% CI: 86.07–100.00) for LUS in detecting patients at moderate-to-high risk based on the HEFESTOS score. The positive predictive value (PPV) was 100%, and the negative predictive value (NPV) was 60.0% (95% CI: 29.64–90.36).

In the multivariate model with decompensation as the dependent variable, which included age, sex, HEFESTOS risk, and LUS score, only the HEFESTOS risk maintained a statistically significant association with decompensation (95% CI [1.01–1.06]; p = 0.01). LUS score, age, and sex were not statistically significant.

Table 6 summarizes the statistical analyses comparing the HEFESTOS risk classification with LUS findings, including measures of agreement, diagnostic accuracy, correlation, and multivariate predictive value.

4. Discussion

Findings included that 25 patients (23.3%) experienced decompensation during a mean follow-up of 72 days. The HEFESTOS score was found to be a statistically significant predictor of decompensation in a multivariate analysis, supporting its prognostic value beyond the initial 30-day period. LUS demonstrated moderate discriminative capacity (AUC = 0.677), with high sensitivity (81.7%) and positive predictive value (81.7%) in identifying patients at higher risk. The study also found a moderate agreement (Cohen’s Kappa = 0.456) and a low to moderate correlation (Pearson coefficient = 0.489) between the HEFESTOS and LUS scores.

LUS is described as a rapid, mobile, and non-invasive method to monitor dynamic changes in pulmonary congestion, which may identify those at high risk for adverse events [

26,

27,

28,

29] more accurately than physical examination and lung X-ray [

30,

31]; additionally, it adds discriminative value to neuropeptides for the diagnosis, prognosis, and treatment of patients with decompensated HF with the use of a new CA19 biomarker [

32,

33,

34,

35]. Despite the evidence, there is currently no systematic implementation of LUS for standard monitoring of HF patients in primary care. Despite a recommendation (Class I, level B) by the ESC Guidelines [

10,

36], which suggests an intensive strategy involving the initiation and rapid up-titration of evidence-based treatment before discharge, along with frequent and careful follow-up visits in the first 6 weeks following HF hospitalization to reduce the risk of HF rehospitalization or all-cause death at 180 days, it does not specifically advocate the use of LUS for detecting pulmonary congestion in out-patients with HF.

The updated consensus reflects the advancements in LUS technology and its applications, providing a contemporary framework for practitioners. Ultimately, a clinical consensus statement of the European Association of Cardiovascular Imaging [

37] becomes the reference standard in HF care and facilitates the exclusion of other highly prevalent conditions that may mimic or overlap with HF. Despite these strides, there remains a need for further research and exploration, particularly in the context of outpatient monitoring of HF patients in primary care.

Although current literature does not explicitly detail the combined use of the HEFESTOS score and LUS, these two tools focus on similar clinical aspects and patient types, especially in HF decompensation. HEFESTOS score offers a simple, validated method for identifying high-risk patients based on clinical symptoms and history, making it highly applicable in primary care. In contrast, LUS provides an immediate, objective, and dynamic measure of pulmonary congestion—often preceding overt symptoms—and can serve as a physiologic complement to HEFESTOS-based risk stratification. Our findings suggest a synergistic value when both tools are applied together. Clinically, this allows for a practical clinical decision-making framework: when both HEFESTOS and LUS indicate low risk (HEFESTOS ≤3, aerated or mildly congested lung), the patient can be safely managed and maintain routine follow-up. If LUS shows moderate-to-severe congestion despite a low HEFESTOS score, clinicians should suspect subclinical congestion and consider early treatment intensification. Conversely, a high HEFESTOS score with minimal LUS findings may reflect risk driven by non-congestive mechanisms, warranting closer clinical surveillance and short-term reassessment.

Table 7 summarizes this proposed clinical algorithm, outlining follow-up recommendations according to the combined results of HEFESTOS and LUS at baseline.

Moreover, because LUS can be repeated easily and interpreted dynamically, its use is particularly valuable in transitional care programs or in patients flagged as high risk by HEFESTOS. This dual-strategy offers a nuanced and individualized approach to risk assessment, bridging clinical scoring with physiologic monitoring to better anticipate—and potentially prevent—heart failure decompensation.

By designing the study to be inclusive of all HF phenotypes, regardless of ejection fraction, the research seeks to establish a universally applicable management strategy. This is particularly crucial for HFpEF patients, for whom effective, evidence-based therapies are still less defined compared to HFrEF. Demonstrating efficacy across the spectrum of ventricular function would significantly enhance the generalizability and clinical relevance of the study’s findings, making the proposed intervention a more robust and widely adoptable approach for the diverse and growing HF patient population.

The study has several limitations that affect the interpretation and generalizability of its findings. On one hand, the study population consisted of 107 patients. While this allowed for group comparisons, the small sample size may limit the statistical power and the ability to generalize the results to a broader population. On other hand, the study found a statistically significant positive correlation between both scores, but the correlation coefficients were moderate. This indicates that while a relationship exists, suggesting other factors are far more influential. Finally, the use of the LUS scale for B-line quantification, while a standard clinical tool, is a rating-based method that may be less sensitive or objective due to its dependence on the individual clinical experience of the operator.

5. Conclusions

HEFESTOS score was independently associated with heart failure decompensation in this cohort, confirming its prognostic relevance beyond the initial 30-day timeframe and supporting its routine use for risk stratification in the outpatient setting.

Although lung ultrasound (LUS) did not retain independent prognostic value in multivariate analysis, it showed good sensitivity and moderate discriminative ability. Its capacity to detect pulmonary congestion and its moderate agreement with HEFESTOS suggest a valuable complementary role, particularly in cases of diagnostic uncertainty or for early identification of subclinical congestion.

These findings support the use of HEFESTOS score in primary care and highlight the potential utility of integrating LUS into individualized follow-up strategies. Further studies are warranted to define the most effective ways to combine clinical scoring systems with physiologic monitoring tools in real-world HF management.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Rosa Caballol-Angelats, Maylin Montelongo-Sol, Laura Conangla-Ferrin and José María Verdú-Rotellar; Data curation, Jose Fernández-Saez; Formal analysis, Josep Lluís Clua-Espuny; Funding acquisition, Rosa Caballol-Angelats and Josep Lluís Clua-Espuny; Investigation, José María Verdú-Rotellar; Methodology, Laura Conangla-Ferrin; Project administration, Rosa Caballol-Angelats; Resources, Marcos Haro-Montoya; Software, Jose Fernández-Saez; Supervision, Victoria Cendrós-Cámara; Validation, Victoria Cendrós-Cámara; Writing – original draft, Marcos Haro-Montoya; Writing – review & editing, Rosa Caballol-Angelats.

Funding

This research was funded by the Dr. Ferran 2022 Grant for the best research project (Beca Dr. Ferran 2022 al millor projecte d’Investigació), with a total amount of €3,000, (Tortosa, Spain). More information about the award is available at https://fundacioferran.org/acte-de-lliurement-de-la-convocatoria-2022.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Clinical Research Ethics Committee of IDIAP Jordi Gol (reference 22/143P).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

During the preparation of this study, the authors used AI for translation purposes. The authors have reviewed and edited the output and take full responsibility for the content of this publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| HF |

Heart failure |

| LUS |

Lung Ultrasound |

| NYHA |

New York Heart Association |

| ATDOM |

Home care program |

References

- Bragazzi, N.L.; Zhong, W.; Shu, J.; Abu Much, A.; Lotan, D.; Grupper, A.; Younis, A.; Dai, H. Burden of heart failure and underlying causes in 195 countries and territories from 1990 to 2017. Eur. J. Prev. Cardiol. 2021, 28, 1682–1690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Savarese, G.; Lund, L.H. Global Public Health Burden of Heart Failure. Card. Fail. Rev. 2017, 1, 7–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Díez-Villanueva, P.; Jiménez-Méndez, C.; Alfonso, F. Heart failure in the elderly. J. Geriatr. Cardiol. 2021, 18, 219–232. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Sicras-Mainar, A.; Sicras-Navarro, A.; Palacios, B.; Varela, L.; Delgado, J.F. Epidemiología de la insuficiencia cardiaca en Espana: Estudio PATHWAYS-HF. Rev. Esp. Cardiol. 2022, 75, 31–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santos, P.M.; Freire, R.B.; Fernández, A.E.; Sobrino, J.L.B.; Pérez, C.F.; Somoza, F.J.E.; Miguel, C.M.; Vilacosta, I. Mortalidad hospitalaria y reingresos por insuficiencia cardiaca en Espana. Un estudio de los episodios índice y los reingresos por causes cardiacas a los 30 días y al ano. Rev. Esp. Cardiol. 2019, 72, 998–1004. [Google Scholar]

- Groenewegen, A.; Rutten, F.H.; Mosterd, A.; Hoes, A.W. Epidemiology of heart failure. Eur. J. Heart Fail. 2020, 22, 1342–1356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martínez Santos P, Bover Freire R, Esteban Fernández A, Bernal Sobrino JL, Fernández Pérez C, Elola Somoza FJ, et al. Mortalidad hospitalaria y reingresos por insuficiencia cardiaca en España. Rev Esp Cardiol. 2019;72(12):998–1004. [CrossRef]

- Kleiner Shochat, M.; Fudim, M.; Kapustin, D.; Kazatsker, M.; Kleiner, I.; Weinstein, J.M.; Panjrath, G.; Rozen, G.; Roguin, A.; Meisel, S.R. Early Impedance-Guided Intervention Improves Long-Term Outcome in PatientsWith Heart Failure. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2021, 78, 1751–1752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al Sattouf, A.; Farahat, R.; Khatri, A.A. Effectiveness of Transitional Care Interventions for Heart Failure Patients: A Systematic Review with Meta-Analysis. Cureus 2022, 14, e29726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- A McDonagh, T.; Metra, M.; Adamo, M.; Gardner, R.S.; Baumbach, A.; Bohm, M.; Burri, H.; Butler, J.; Cˇ elutkiene˙, J.; Chioncel, O.; et al. 2023 Focused Update of the 2021 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure. Eur. Heart J. 2023, 44, 3627–3639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miglioranza MH, Gargani L, Sant’Anna RT, Rover MM, Martins VM, Mantovani A, et al. Lung ultrasound for the evaluation of pulmonary congestion in outpatients: a comparison with clinical assessment, natriuretic peptides, and echocardiography. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2013;6(11):1141–51. [CrossRef]

- Pugliese NR, Pellicori P, Filidei F, Del Punta L, De Biase N, Balletti A, et al. The incremental value of multi-organ assessment of congestion using ultrasound in outpatients with heart failure. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Imaging. 2023;24(7):961–71. [CrossRef]

- Panisello-Tafalla A, Haro-Montoya M, Caballol-Angelats R, Montelongo-Sol M, Rodriguez-Carralero Y, Lucas-Noll J, Clua-Espuny JL. Prognostic Significance of Lung Ultrasound for Heart Failure Patient Management in Primary Care: A Systematic Review. J Clin Med. 2024 Apr 23;13(9):2460. [CrossRef]

- Verdu-Rotellar JM, Abellana R, Vaillant-Roussel H, Gril Jevsek L, Assenova R, Kasuba Lazic D, Torsza P, Glynn LG, Lingner H, Demurtas J, Thulesius H, Muñoz MA; HEFESTOS group. Risk stratification in heart failure decompensation in the community: HEFESTOS score. ESC Heart Fail. 2022 Feb;9(1):606-613. [CrossRef]

- Rivas-Lasarte, M.; Maestro, A.; Fernández-Martínez, J.; López-López, L.; Solé- González, E.; Vives-Borrás, M.; Montero, S.; Mesado, N.; Pirla, M.J.; Mirabet, S.; et al. Prevalence and prognostic impact of subclinical pulmonary congestion at discharge in patients with acute heart failure. ESC Heart Fail. 2020, 7, 2621–2628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Conangla L, Domingo M, Lupón J, Wilke A, Juncà G, Tejedor X, et al. Lung Ultrasound for Heart Failure Diagnosis in Primary Care. J Card Fail. 2020;26(10):824–31. [CrossRef]

- Domingo M, Conangla L, Lupón J, Wilke A, Juncà G, Revuelta-López E, et al. Lung ultrasound and biomarkers in primary care: Partners for a better management of patients with heart failure? J Circ Biomark. 2020;9:8–12. [CrossRef]

- Verdu-Rotellar JM, Abellana R, Vaillant-Roussel H, Gril Jevsek L, Assenova R, Kasuba Lazic D, et al; HEFESTOS group. Risk stratification in heart failure decompensation in the community: HEFESTOS score. ESC Heart Fail. 2022 Feb;9(1):606–613. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Masarone D, Kittleson MM, Pollesello P, Marini M, Iacoviello M, Oliva F, et al. Use of Levosimendan in Patients with Advanced Heart Failure: An Update. J Clin Med. 2022;11(21):6408. [CrossRef]

- Idescat: Institut d’Estadísitica de Catalunya. Indicadors demogràfics i de territori 2024. Estructura per edats, envelliment i dependència. Anuario Estadístico de Cataluña; 2024. Available online: https://www.idescat.cat/pub/?id=inddt&n=915&geo=at (accessed on day month year).

- INE: Instituto Nacional de Estadística. Indicadores de Estructura de la Población. Índice de Envejecimiento por Comunidad Autónoma; 2024. Available online: https://www.ine.es/jaxiT3/Datos.htm?t=1452#_tabs-tabla (accessed on day month year).

- Idescat: Institut d’Estadísitica de Catalunya. Anuari estadístic de Catalunya. Renda familiar disponible bruta. RFDB i RFDB per habitant. Comarques i Aran, i àmbits; 2022. Available online: https://www.idescat.cat/indicadors/?id=aec&n=15917 (accessed on day month year).

- McDonagh TA, Metra M, Adamo M, Gardner RS, Baumbach A, Böhm M, et al. 2023 Focused Update of the 2021 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure: Developed by the task force for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) With the special contribution of the Heart Failure Association (HFA) of the ESC. Eur Heart J. 2023 Oct 1;44(37):3627–39. [CrossRef]

- Catalan Health Service. Conceptual bases of the model of care for people with frailty and advanced complex chronic conditions. Barcelona: Servei Català de la Salut. Departament de Salut. Generalitat de Catalunya; 2021. Available online: https://scientiasalut.gencat.cat/bitstream/handle/11351/7007/bases_conceptuals_model_atencio_persones_fragils_cronicitat_complexa_avancada_2020_ang.pdf (accessed on day month year).

- Jambrik Z, Monti S, Coppola V, Agricola E, Mottola G, Miniati M, et al. Usefulness of ultrasound lung comets as a nonradiologic sign of extravascular lung water. Am J Cardiol. 2004 May 15;93(10):1265–70. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Picano, E.; Scali, M.C.; Ciampi, Q.; Lichtenstein, D. Lung ultrasound for the cardiologist. JACC Cardiovasc. Imaging 2018, 11, 1692–1705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bekgoz, B.; Kilicaslan, I.; Bildik, F.; Keles, A.; Demircan, A.; Hakoglu, O.; Coskun, G.; Demir, H.A. BLUE protocol ultrasonography in Emergency Department patients presenting with acute dyspnea. Am. J. Emerg. Med. 2019, 37, 2020–2027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wooten, W.M.; Hamilton, L.A. Bedside ultrasound versus chest radiography for detection of pulmonary edema: A prospective cohort study. J. Ultrasound. Med. 2019, 38, 967–973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gullett, J.; Donnelly, J.P.; Sinert, R.; Hosek, B.; Fuller, D.; Hill, H.; Feldman, I.; Galetto, G.; Auster, M.; Hoffmann, B. Interobserver ultrasound. J. Crit. Care 2015, 30, 1395–1399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chiem, A.T.; Chan, C.H.; Ander, D.S.; Kobylivker, A.N.; Manson, W.C. Comparison of expert and novice sonographers’performance in focused lung ultrasonography in dyspnea (FLUID) to diagnose patients with acute heart failure syndrome. Acad.Emerg. Med. 2015, 22, 564–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prosen, G.; Klemen, P.; Štrnad, M.; Grmec, S. Combination of lung ultrasound (a comettail sign) and Nterminal probrain natriurètic peptide in differentiating acute heart failure from chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and asthma as cause of acute dyspn.

- Núnez, J.; de la Espriella, R.; Rossignol, P.; Voors, A.A.; Mullens, W.; Metra, M.; Chioncel, O.; Januzzi, J.L.; Mueller, C.; Richards, A.M.; et al. Congestion in heart failure: A circulating biomarker-based perspective. A review from the BiomarkersWorking Group of the Heart Failure Association, European Society of Cardiology. Eur. J. Heart Fail. 2022, 24, 1751–1766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Núnez, J.; Llàcer, P.; García-Blas, S.; Bonanad, C.; Ventura, S.; Núnez, J.M.; Sánchez, R.; Fácila, L.; de la Espriella, R.; Vaquer, J.M.; et al. CA125-Guided Diuretic Treatment Versus Usual Care in Patients with Acute Heart Failure and Renal Dysfunction. Am. J.Med. 2020, 133, 370–380.e4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Núnez, J.; Bayés-Genís, A.; Revuelta-López, E.; Ter Maaten, J.M.; Minana, G.; Barallat, J.; Cserkóová, A.; Bodi, V.; Fernández-Cisnal, A.; Núnez, E.; et al. Clinical Role of CA125 in Worsening Heart Failure: A BIOSTAT-CHF Study Subanalysis. JACC Heart Fail. 2020, 8, 386–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McDonagh, T.A.; Metra, M.; Adamo, M.; Gardner, R.S.; Baumbach, A.; Bohm, M.; Burri, H.; Butler, J.; Cˇ elutkiene˙, J.; Chioncel, O.; et al. 2021 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure: Developed by the Task Force for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) With the special contribution of the Heart Failure Association (HFA) of the ESC. Eur. Heart J. 2021, 42, 3599–3726. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Platz, E.; Jhund, P.S.; Girerd, N.; Pivetta, E.; McMurray, J.J.V.; Peacock, W.F.; Masip, J.; Martin-Sanchez, F.J.; Miró, ..; Price, S.; et al.Expert consensus document: Reporting checklist for quantification of pulmonary congestion by lung ultrasound in heart failure. Eur. J. Heart Fail. 2019, 21, 844–851.

- Gargani L, Girerd N, Platz E, Pellicori P, Stankovic I, Palazzuoli A, Pivetta E, Miglioranza MH, Soliman-Aboumarie H, Agricola E, Volpicelli G, Price S, Donal E, Cosyns B, Neskovic AN; This document was reviewed by members of the 2020–2022 EACVI Scientific Documents Committee. Lung ultrasound in acute and chronic heart failure: a clinical consensus statement of the European Association of Cardiovascular Imaging (EACVI). Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Imaging. 2023 Nov 23;24(12):1569-1582. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Routine follow-up.

Routine follow-up. Intensify treatment.

Intensify treatment.  Frequent clinical reassessment. Monitor for non-congestive mechanisms.

Frequent clinical reassessment. Monitor for non-congestive mechanisms. Intensive follow-up.

Intensive follow-up.