1. Introduction

Corporate identity has played a vital role in the Halal industry to create a strong foundation for its reputation in the long run. Corporate Identity is one of the major catalysts that contribute to more impactful outcomes for the organisation to reap from it, which includes promoting transparency in the communication among stakeholders and contributing to positive morale and retention of the highly skilled employee (Melewar et al., 2005).

Halal (permissible) and Thoyyibban (wholesome) are two (2) fundamental pillars of Islam, both of which are clearly mentioned in the Holy Quran (Al-Baqarah, 2:168-174). Halal is an Arabic term that implies acceptable or accepted under Sharia (Islamic) law (Noordin et al., 2009). Thoyyibban, on the other hand, denotes the high quality, safety, cleanliness, nutrition, and authenticity (Mariam, 2006).

Corporate Identity Management (CIM) in the corporate industry has been extensively discussed and acknowledged as well in literature as an important area of study (Melewar et al., 2017; Simões et al., 2005; Simões & Sebastiani, 2017). In Malaysia Halal Industry Master Plan 2030 (HIMP 2030) stated four major objectives to be achieved which are a robust and diversified domestic Halal industry; simplifying the business model; competitive business participation and internationalisation of the Halal Malaysia brand. The objective of this study is to examine the relationships between corporate identity management (CIM) in the Halal industry and employee brand support and also the relevant underlying mechanisms in a Malaysian Halal industry context.

Corporate Identity Management (CIM) is crucial in organisations, and numerous re- searches has been conducted on it. Unfortunately, few studies have been conducted to demonstrate the influence of the CIM on the Halal industry. The majority of research in the halal food production business is centred on supply chain management and halal certification as a procedure (Masrom, Rasi, At, & Daut, 2017; Noordin, Noor, Hashim, & Samicho, 2009; Noordin, Noor, & Samicho, 2014).

According to the State of the Global Islamic Economy Report (2018/2019) that stated the identity of halal is crucial to be understood as a core value for the company’s brand identity. A strong brand identity is crucial in upholding the global halal industry and its aim to become one of the biggest industries in the world. However, the under-par performance of organisations especially Small and Medium Enterprises (SMEs) is the biggest obstacle that needs to be focused on to achieve the aim itself. In Malaysia’s Halal industry setting, poor adoption of communication technology and confusion in the information of Halal and obscurity in the understanding of halal management process among SMEs are the challenges in achieving a good brand identity (Mohd Shahwahid et al., 2015; Pauzi & Man, 2018).

A reputation for high-quality goods and services, a solid financial performance, harmony and an accommodating workplace atmosphere, and a reputation for social and environmental responsibility are all elements of a successful corporate identity (Erkmen, & Hancer, 2015; Einwiller & Will, 2002). According to Safiullin, Galiullina, and Shabanove (2016), the manufacturing of goods and services in accordance with Halal criteria is currently a global trend. This is the main reason for the industry to excel fast in the global market right now as mentioned above that it has already acquired 21.1 % of the market share. The process of globalisation of trade in separate segments of commodity markets shows table development. That segment is the product made in accordance with the requirements of Halal. Hence, competition is no longer limited to national borders.

Good identity management starts from a good relationship with the internal stakeholders. Internal stakeholders have a significant influence in shaping the organisation's corporate identity. In their study on a conceptual model for corporate identity management in the healthcare industry, Rutitis, Batraga, Skiltere, and Ritovs (2014) put a significant emphasis on the management of corporate identity factors with respect to the use of visual identity structures, active integration and utilisation of regulations as a part of patient service culture, and active use of multiple communication guidelines. All of this demonstrates that internal communication has a substantial influence on information distribution via a communication channel in everyday operations. Good internal communication aims to provide access to benefits the important employee self-service, especially for quality perceptions. Managers benefit from the functionality of electronic service de- livery channels in employee self-service arrangements. Employees also have direct and quick self-directed access to their benefits and pay information, which is likely to result in higher levels of satisfaction, which may translate into considerable benefits for the organisation in terms of motivation, performance, and job retention. Consequently, a communication system is meant to assure employees' continuous and inspired commitment to the organisational objective through the direct supply of required support services and benefits goods (Yang et al., 2011).

As halal standards have to become a global standard, a good identity needs to be constructed and become a halal marketing strategy for the standard akin to all Muslims as well as non-Muslims. However, this presents several challenges for the halal industry such as coming out with a globalised identity and promotional strategies. For example, in the tourism business, hotels and places that cater to Muslim visitors do not want to attract solely the Muslim traveller demographic while leaving the other market segments, creating a conundrum over what their identity and marketing approach should be (Elasraq, 2016). This motivates the halal business to create an efficient structure, such as internal communication, to assist employees in improving their marketing effectiveness. As a result, the quality and efficiency of their goods and services improve (Tooley et al., 2003). Following that, study findings revealed that customers' perceptions of halal logistics, halal concerns, and media attention all had a favourable and significant impact on consumers' willingness to pay for halal logistics.

The willingness to pay and the level of demand for halal logistics certification have a favourable link (Fathi, Zailani, Iranmanesh, and Kanapathy, 2016). However, they emphasised that, while halal logistics is important in maintaining the halal quality of food, request for these services is minimal. This is a challenge for the halal business in terms of setting goals for strategic planning, assessing performance, and supporting stakeholders (Hazelkorn, 2007). In Malaysia, it is expected that the Halal industry would contribute around 8.1 per cent of the country's GDP by 2025. Because Malaysia aspires to be the world's top halal centre, as specified in the Halal Industry Master Plan 2030, suitable infrastructure and a robust support base are critical. A well-trained staff capable of enabling knowledge and expertise is essential for a quick entry into the global halal market. As a result of this issue, Malaysia has begun to invest extensively in programmes to strengthen its halal brand in the field. Effectively maintained corporate identity may help a company gain a competitive edge over its competitors (Olins, 2017). As a result, an increasing number of businesses have begun to create and execute corporate identity management as part of their strategic growth and expansion (Baker and Balmer, 1997). Many scholars feel that one of the primary outcomes of corporate identity management is a greater understanding of its origins, such as corporate culture and internal brand. Corporate culture, employee values, and internal brand are intangible characteristics that can assist organisational health by recruiting and keeping great employees (Goodman and Loh, 2011) and offering a significant competitive advantage to the organisation (Sadri and Lees, 2001). Many management studies have demonstrated the importance of such factors in the organisational structure.

Communication is paramount when it comes to building a strong employee brand support and CIM acts as a catalyst in the communication of the determinant factors. The industry has invested millions in developing the brand. However, the lack of attention given to developing and enhancing the CIM in the halal manufacturing industry despite the positive outcome mentioned above is the most apparent problem in the halal industry. This is due to the reluctance of the employees to adapt to the system in internal communication (Ab Talib et al., 2015).

2. Literature Review

2.1. Corporate Identity Management (CIM)

There are extrinsic and intrinsic elements of corporate identity management suggested by previous scholars. The extrinsic elements such as corporate design (visual identity), symbolism, theme/ visual and structure significantly influence the construction of the organisation’s identity which eventually suggests the form of brand appearance that the internal members integrate into. The intrinsic elements such as behaviour, culture and expression of the brand influence internal members to believe and uphold the brand identity of the organisation (Melewar & Jenkins, 2002; Batraga, & Rutitis, 2012; Cornelissen & Elving, 2003; Melewar, 2003; Maurya, Mishra, Anand & Kumar, 2015; Melewar & Karaosmanoglu, 2006; Coleman, de Chernatony & Christodoulides, 2011; Buil, Catalan, & Eva Martínez, 2016).

These elements have been discussed by past scholars in determining their relation- ship. There is still a lack of study in discussing the relationship between these two variables and since then, many scholars came out with findings that support a strong relation- ship between these variables (Simoes et al., 2015; Demenint, van der Vlist & Allegro, 1989; Judson et al., 2006; Whisman, 2009).

2.2. Internal Brand (IB)

Branding programs, branding activities, training and management developments are suggested initiatives by previous scholars to nurture a favourable behaviour of employees towards the identity built by the organisation. A well-informed employee will recognize the brand identity of the organisation and this will be a crucial influential factor to the external public (Hatch & Schultz, 2001; Ind, 1997, 2007; Tosti & Stotz, 2001; Vallaster & de Chernatony, 2004; Schmidt & Ludlow, 2002; Burmann & Konig, 2011; Punjaisri & Wilson, 2007; Pranjal & Sarkar, 2020; Whisman, 2009; Naude & Ivy, 1999; Ivy, 2001; Jevons, 2006; Stensaker, 2005; Schiffenbauer, 2001; Judson et al., 2006). These elements have been discussed by past scholars in determining their relationship. It is suggested that favourable behaviour of employees towards the organisation’s identity is the fundamental indicator of healthy internal brand and good governance in identity management (Urde, 2003; Melewar & Jenskin, 2002; Mohamad et al., 2009; Vallaster & de Chernatony, 2005; Tourky et al., 2020; Gambetti, Melewar, & Martin, 2017).

2.3. Corporate Culture (CC)

Fourteen aspects have been suggested by previous scholars on a good corporate culture which is vision, values, practices, people, narratives (history), place, liabilities of the organisation in relation to the employees, task evaluation, career planning, control system, decision making, level of responsibility, person’s interest and shared a total of granted assumptions (Coleman, 2013; Ouchi, 1981; Schein, 1999). All these aspects are combined to form good identity management for the organisation where it forms patterns that help employees to understand the function of the organisation and influences the decisions making to achieve organisational objectives and principles. This outcome is the product of the synchronisation of CIM and corporate culture (Deshpande & Webster, 1989; Smith, 1966; Tourky et al., 2020). These aspects have been discussed by past scholars in determining their relationship. From the discussion above, it has been suggested by past scholars that corporate culture significantly influenced good corporate identity management (CIM).

2.4. Antecedents and Employee Brand Support (EBS)

Brand training activities are fundamental for internal and external stakeholders to nurture a favourable attitude and behaviour towards the brand upheld by the organisation. Specific planned activities for internal stakeholders should be different from external stakeholders since the approach is different. Having a good internal branding will yield a massive influential factor in representing the brand to external stakeholders in brand marketing activities (Hatch & Schultz, 2001; Ind, 1997, 2007; Tosti & Stotz, 2001; Vallaster & de Chernatony, 2004; Schmidt & Ludlow, 2002; Burmann & Konig, 2011; Punjaisri & Wil- son, 2007; Pranjal & Sarkar, 2020; Whisman, 2009; Naude & Ivy, 1999; Ivy, 2001; Jevons, 2006; Stensaker, 2005; Schiffenbauer, 2001; Judson et al., 2006). As a result of good internal branding activities, the organisation will enjoy a strong brand commitment and positive behaviour from employees since they received adequate brand support which develops values for employees (de Chernatony, 2002; Vallaster & de Chernatony, 2004; Hankinson, 2004; Aurand et al., 2005; Burmann & Zeplin, 2005; Vallaster & de Chernatony, 2005, 2006; Punjaisri & Wilson, 2007; Burmann & Zeplin, 2005; Karmark, 2005). Previous researchers have explored these features in order to determine their link and claimed that internal brand greatly affected excellent employee brand support, based on the explanation above.

All aspects that have been suggested by previous scholars on a good corporate culture which are vision, values, practices, people, narratives (history), place, liabilities of the organisation in relation to the employees, task evaluation, career planning, control system, decision making, level of responsibility, person’s interest and shared a total of granted assumptions (Coleman, 2013; Ouchi, 1981; Schein, 1999). From a good corporate culture, the organisation will have greater identification from external stakeholders since the brand identity developed by the organisation portraits a desirable, proper, or appropriate embedded with a socially constructed system of norms, values, beliefs and definitions included in a culture which is a product for having employees with adequate brand support (Bravo, Buil, Chernatony & Martinez 2017; Barney, 1986 & Schein, 1999; Kapferer, 1992; Kates, 2004; Bravo, Buil, Chernatony & Martinez 2017; Barney, 1986 & Schein, 1999). These aspects have been discussed by past scholars in determining their relationship. From the discussion above, it has been suggested by past scholars that corporate culture significantly influenced good employee brand support.

These conclusions and findings from past literature show there is a relationship between corporate culture and employee brand support.

The hypothesis that has been constructed based on the literature review is as follow:

H1:

There is a positive relationship between Corporate Identity Management (CIM) as the mediator between Internal Brand and Corporate Culture (antecedents) with Employee Brand Support (consequence).

3. Methodology

3.1. Quantitative Data Collection Procedure

The study used a quantitative approach with two data collection methods which are self-administered questionnaires and knowledge-mining of journal databases through machine learning (ML) technique. As proposed by Churchill, the initial data gathering approach, the instrument for self-administered surveys, was designed in four stages (1979). The first stage is item generation, which is used to generate a pool of items by recognising the object using existing scales. The second stage entails going over the operationalization of variables from previous literature. This was done to identify elements that have previously been utilised in publications. The third step entails the scale of content and face validity process. The basic process, as will be detailed in further detail in the following parts, is to have panels of judges certify the legitimacy of items based on their representativeness and clarity. Based on their placement items with a low score could be eliminated. Finally, the combination of various scales after the content and face validity processes are ready for the instrument testing stage. The instrument (questionnaire) was delivered to a small sample of respondents to provide an early indication of the reliability of the scales. Based on the results, each component that does not add to the dependability of the scales is removed, and the instrument is field-tested. According to Bryman and Cramer (1997), Cronbach's alpha computed the average of all possible split-half dependability coefficients. As a general rule, reliability coefficients of 0.8 or above are considered satisfactory. The reliability test was carried out using a total of 43 samples from the pilot test. Cronbach's Alpha was calculated and found to be quite high at 0.9. This result is consistent with the characteristics of a dependable instrument; hence the instrument is verified.

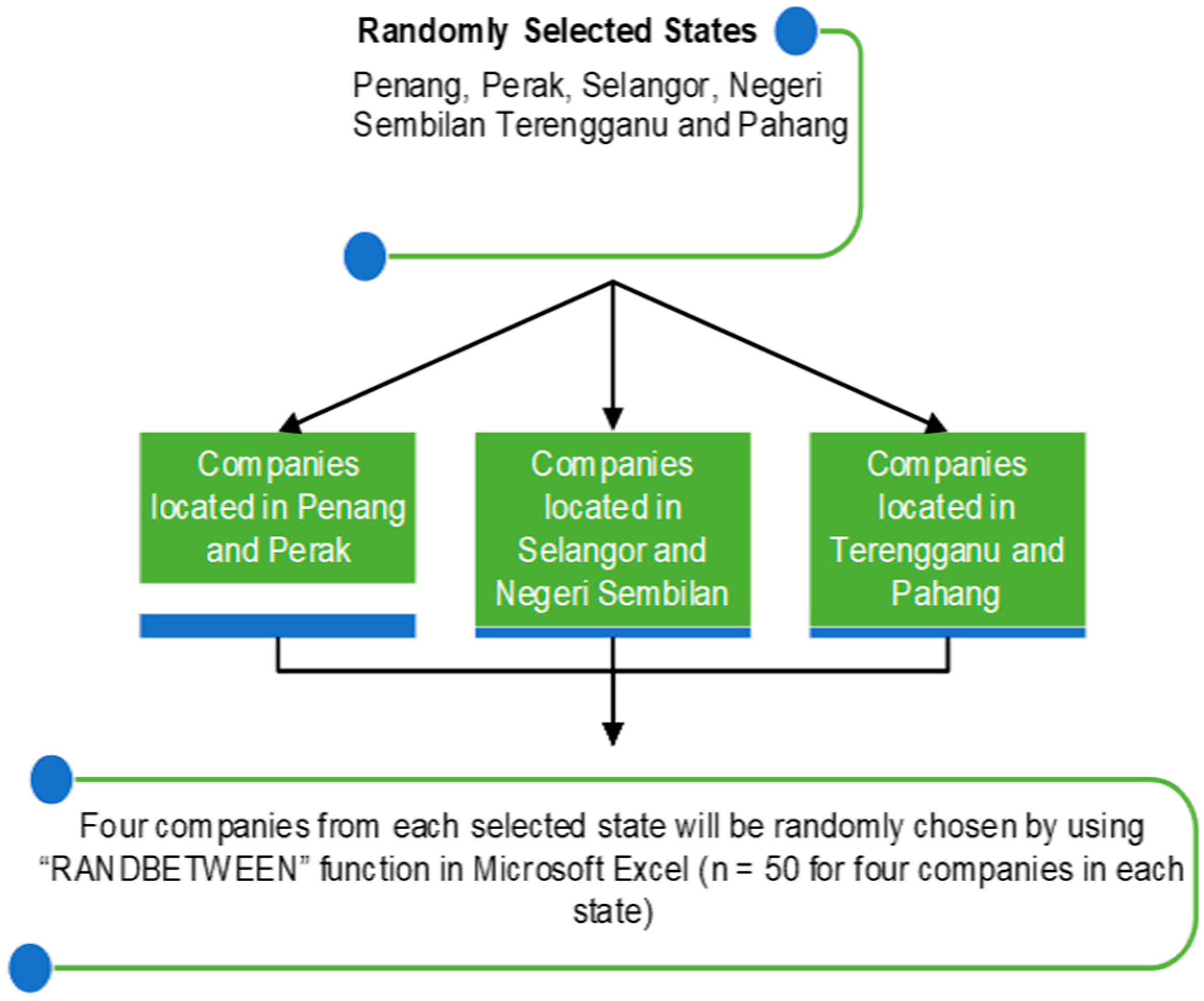

A multi-stage sampling technique was used to identify the sampling for this study. Multistage sampling meant that resources and efforts could be concentrated in a limited number of areas of the country, and the number of samplings was equally distributed between the chosen states (Sedgwick, 2015).

The multistage sampling technique in this study was able to balance sampling numbers in each of the selected states to avoid biases in the distribution of sampling numbers. The Multi-stages sampling technique will ensure the quality of the sampling is met to gain reliable data from the respondents.

Multistage sampling consists of at least two random sample phases depending on the nature of natural clusters within the targeted population (Sedgwick, 2015). Clusters are groups of people who share the same features or characteristics, identified by the researcher. In this study, the group of individuals chosen as respondents all share the same characteristic: they work in a Halal industry SME. In this study, the selected states were chosen at random initially, followed by the firms in each chosen state. The states in Peninsular Malaysia have been chosen for the location of the study since most of the Halal SMEs are concentrated in the states of Peninsular Malaysia (SME Corporation Annual Report, 2017). All the states have been clustered based on the provinces which are north, south, central and west coast. The table below summarises the states based on the mentioned clusters:

Table 1.

Clustered States Based on the Provinces.

Table 1.

Clustered States Based on the Provinces.

| North Province |

South Province |

Central Province |

West Coast Province |

| Perlis |

Johor |

Selangor |

Kelantan |

| Kedah |

|

Negeri Sembilan |

Terengganu |

| PenangPerak |

|

Melaka |

Pahang |

The states that clustered above will be chosen for the data collection location. Selection bias needs to be avoided to give an equal chance for each of the states to be chosen as the location of data collection in this study (Winship, 1992). ‘Randomised Between’ function (“RANDBETWEEN”) in Microsoft Excel will be used to randomly choose the state based on the cluster above. This will ensure that all states will have an equal opportunity to be chosen. Once each state represents each province has been chosen, the list of companies will be clustered based on each selected state. The companies will undergo the same process of randomised picking by using the ‘Randomised Between’ function (“RANDBETWEEN”) in Microsoft Excel. Four companies in each selected state will be randomly chosen using the same mentioned technique. With this sampling procedure applied in this study, it will ensure a fair sampling distribution across the location of the study and selection bias can be avoided through randomised selection of states and companies. The figure below summarises the multi-stage sampling in a more understandable manner:

Figure 1.

Multi-stage Sampling Procedure of the Study (adapted from Sedgwick, 2015).

Figure 1.

Multi-stage Sampling Procedure of the Study (adapted from Sedgwick, 2015).

Once the states have been chosen, the same process was repeated to determine which company will be included in this study based on the states selected. The researcher man- aged to acquire the list of the registered SMEs for each state from IKS.my, JAKIM and Halal Development Corporation (HDC). The list of SMEs will be compared and cross- checked with each acquired list to ensure only the companies that fulfil the criteria are included in the data collection process. Once companies have been identified, the number of samples will be divided equally amongst states and companies to have balanced samplings in each of the companies. The selection process for the location of the study is fundamental since this process will ensure that the data is collected fashionably.

In determining the sample size, two tests that this study used to determine the ap- propriate sampling size. The first one is Power value analysis through A priori sample size estimation and Monte Carlo Simulation in determining the sample size. Power analysis is based on the acceptable value of the effect size (f2) and acceptable significant error value (α value) in determining a power value (1 – β). The determined f2, α and β values will estimate the appropriate sample size to achieve a statistical significance that will suit the determined f2, α and β (Cohen, 1988). The first test in determining appropriate sample size, A Priori power analysis to determine the appropriate sampling size was used. Since this study is using Partial Least Squares - Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM), this test will determine a minimum sample size that will give statistical significance for this study. G*Power analysis calculator version 3.1.9.7 was used by the researcher for this purpose. This calculator is a good program that can be utilised by researchers who are adopting PLS-SEM in their data analysis (Hair et al. 2013).

By estimating that this study will yield an absolute effect size (f2) value of 0.15, alpha (α) value for significant error of 0.05 and determine power (β) value of 0.8 (a minimum value required for statistical significance) it was determined that minimum 77 samples were required to achieve statistical significance for the proposed model in this study (Faul, Erdfelder, Buchner & Lang, 2009).

Monte Carlo Simulation experiments using the inverse square root and gamma-exponential approaches were used as the second test to confirm the number of samplings in this study (Kock & Hadaya, 2018). The inverse square root approach requires a minimum sample number of 160, whereas the gamma-exponential method requires a minimum sample number of 146. The inverse square root technique tends to slightly overestimate the minimum necessary sample size, but the gamma-exponential method offers a more exact estimate (Kock & Hadaya, 2018). Thus, after a careful evaluation based on the con- firmed values mentioned, it is determined that 200 is the appropriate sample size for this study. The actual data collection was able to get a total of 206 respondents.

3.2. Statistical Analysis

This study intended to predict the model used by past researchers in a new setting thus, using the statistical package to test the model in a different setting which is Small and Medium Enterprises (SMEs) in Malaysia’s Halal industry. Thus, using PLS-SEM is more suitable since the objective of the study is to test the model in a different setting. Smart-PLS was chosen as a data statistical package to be used in this study.

To verify the instrument, SPSS will be utilised for Exploratory Factor Analysis (EFA). To finalise the scales, validation adjusted measurement scales using exploratory factor analysis (EFA) (Marsh et al., 1988). The data analysis for this research was divided into two parts: (1) assessing the measurement model for convergent and discriminant validity, and (2) assessing a structural model using Structural Equation Modeling (SEM), as recommended by Henseler et al (2009). The first step is to create an appropriate measuring model. Outer loading (> 0.7), Cronbach's Alpha (> 0.7), Dijkstra-Henseler (Rho-a) (> 0.7), composite reliability (> 0.7), and average variance extracted (AVE) (> 0.5) will be tested for convergent validity in PLS-SEM. Then it follows by the measurement of discriminant validity that will include these criteria which are cross-loading, Fornell-Larcker Criterion and Heterotrait-Monotrait value (< 0.9). Once the measurement model is validated, the second part is conducted to examine the structural model for all constructs by using SmartPLS 3. It starts with the measurement of the outer loading of the observed variables. The measurement of the outer loadings must be more than 0.7 (> 0.7). Then, Cronbach's Alpha value was determined and the value must be more than 0.7 (> 0.7). Dijkstra- Henseler (Rho-a) value needs to be more than 0.7 (> 0.7). Next, followed by the value of composite reliability (CR) and it needs to be greater than 0.7 (> 0.7). Finally, for the convergent validity, the average variance extracted was measured and the value must be greater than 0.5 (> 0.5).

The next process in the assessment of the measurement model for PLS-SEM is deter- mining the discriminant validity of the measurement model. Three criteria need to be fulfilled by the measurement model of this study which is cross-loading, Fornell – Larcker criterion and heterotrait and monotrait (HTMT) value. In the case of cross-loading, the value of each indicator representing its variable is supposed to be larger than the sum of all cross-loadings (Chin, 1998; Gotz et al., 2009; Henseler, Ringle & Sinkovics, 2009). Ac- cording to the Fornell–Larcker criteria (Fornell & Larcker, 1981), a latent variable has more variance with its assigned indicators than with any other latent variable. Statistically, the AVE of each latent variable should be larger than the greatest squared correlation of the latent variable with any other latent variable (Henseler, Ringle & Sinkovics, 2009).

Heterotrait and monotrait (HTMT) value is a new criterion in determining the discriminant validity of measurement models in PLS-SEM (Henseler, Ringle & Sarstedt, 2015). For HTMT value, it should be significantly lower than one (< 1) or a good value of HTMT should be lower than 0.9 (< 0.9) (Heseler, Hubona & Ray, 2015; Henseler, Ringle & Sar- stedt, 2015). These three criteria need to be fulfilled to achieve the discriminant validity of the measurement model.

The data analysis approach permits the link between continuous or discrete independent variables and dependent variables in a PLS-SEM structural equation model. As a result, SEM provides the most relevant, versatile, and competent estimating approach for combining a number of different multiple regression equations into a single statistical test (Hair et al., 2010). The variance of a group of indicators that may be explained by the existence of one unobserved variable (the common factor) and individual random error is used by PLS-SEM to determine the overall path coefficients and significance (structural model) (Henseler, Hubona & Ray, 2016) and generating estimation on common factors and composites, which makes it a good data analysis option for behavioural constructs as well as design constructs (Henseler, 2017). PLS-SEM can verify the consistency of a theoretical model and the estimated model (Diamantopoulos and Siguaw, 2006; Hair et al., 2010; Tabachnick & Fidell, 2007).

The first step for structural assessment for PLS-SEM analysis is to assess the multi- collinearity through Variance Inflation Factor (VIF). The value of inner and outer VIF should be lower than 3.3 (< 3.3) (Kock, 2015).

Next, the assessment of the path coefficient significance is determined through p- value (p < 0.05) and T value (T > 1.96; 95% CI) (Garson, 2016). After path coefficient signif- icance has been determined, the mediating effect was analysed. The full mediation effect is determined if the p-value for the total effect is less than (< 0.05) and the t value is more than 1.96 (> 1.96) (Garson, 2016). Next, the effect size is determined based on Cohen’s effect size rule of thumb (1988) as below:

- a)

.02 represents a “small” effect size

- b)

.15 represents a “medium” effect size

- c)

.35 represents a “high” effect size

The predictive accuracy is determined after the effect size, predictive accuracy is measured to predict the contribution of antecedents to consequence in the whole model accuracy. The predictive accuracy is determined based on these criteria, substantial (≥ 0.75), moderate (0.5 – 0.74), weak (0.25 – 0.49) and non-accurate (≤ 0.24) (Henseler, Ringle & Sinkovics, 2009).

The final analysis for structural model assessment is to determine the predictive relevance. The determining criteria are below as suggested by Henseler, Ringle and Sinkovics (2009):

0.02 ≤ Q² < 0.15 = Low Relevancy

0.15 ≤ Q² < 0.35 = Medium Relevancy

Q² ≥ 0.35 = High Relevancy

4. Result

4.1. Descriptive Analysis of Quantitative Data

The demographic profile of the respondents which include gender, ethnicity, age, education level, marital status, work position, working status, income, and year(s) of work included in the instrument. The demographic details of the respondents are tabulated in the table below:

Table 2.

The demographic of the respondent based on its frequency.

Table 2.

The demographic of the respondent based on its frequency.

| Profile |

|

Frequency |

Percentage (%) |

| Gender |

Male |

79 |

38.30 |

| |

Female |

127 |

61.70 |

| Ethnicity |

Malay |

188 |

91.262 |

| |

Chinese |

15 |

7.282 |

| |

India |

3 |

1.456 |

| Age |

16-22 |

54 |

26.214 |

| |

23-29 |

74 |

35.922 |

| |

30-36 |

30 |

14.563 |

| |

37-43 |

12 |

5.825 |

| |

44-50 |

17 |

8.252 |

| |

52-58 |

13 |

6.311 |

| |

≥59 |

6 |

2.913 |

| Education Level |

No Formal Education |

1 |

0.485 |

| |

Primary School |

4 |

1.942 |

| |

PMR/ SRP/ LCE |

17 |

8.252 |

| |

SPM/ SPMV/ MCE |

95 |

46.117 |

| |

Tertiary Education (Certification, STPM, bachelor’s degree, master’s degree, PhD) |

89 |

43.204 |

| Marital Status |

Single |

116 |

56.311 |

| |

Married |

84 |

40.78 |

| |

Divorced |

6 |

2.913 |

| Working Position |

Higher Management |

32 |

15.534 |

| |

Middle Management |

45 |

21.845 |

| |

Operational |

105 |

50.971 |

| |

Executioner |

24 |

11.65 |

| Working Status |

Permanent |

158 |

76.699 |

| |

Contract |

48 |

23.301 |

| Household Income |

≤ 1,000 |

45 |

21.845 |

| |

1,001 – 2,000 |

83 |

40.291 |

| |

2,001 – 3,000 |

33 |

16.019 |

| |

3,001 – 4,000 |

22 |

10.68 |

| |

≥ 4,001 |

23 |

11.165 |

| Working Year(s) |

1 – 9 |

176 |

85.437 |

| |

10 – 18 |

21 |

10.194 |

| |

19 – 27 |

6 |

2.913 |

| |

28 – 36 |

2 |

0.971 |

| |

≥ 37 |

1 |

0.485 |

The table above describes the demographic of the respondent based on its frequency and percentage. The majority of the respondents who took part in the data collection process are female with a total of 127 (61.70 %). This phenomenon yielded a result that in Halal SMEs, the workforce is dominated by females compared to male workers. Male workers comprise not even half of the workforce with a total of 79 (38.30 %). In terms of ethnicity, it is predicted that the industry has been monopolised by Malay 188 (91.262 %) as respondents in this study. The rest of the respondents represent Chinese and India with 15 (7.282 %) and 3 (1.456 %) respectively. This result is in line with the majority of the Muslim population in this country which is represented by Malay.

The key indicator shown in this demographic table is the working position where the operational workers represent more than half of the respondents with a total number of 105 (50.971 %). This may give the researcher an insight into their perception of the identity of the organisation that they attached to. This is crucial for the result where the researcher will formulate the finding on the brand support received by the employees, especially the operational workers which may provide information on their understanding of the brand that the organisation upholds.

The majority of the respondents are permanent workers with a total of 158 (76.699 %) and the rest of the respondents are contractual workers with a total of 48 (23.301 %). In terms of household income, 83 respondents (40.291 %) are having a household income between 1,001 – 2,000 monthly. This information supports the report from the Department of Statistics Malaysia (2011), which stated that the average monthly income for workers in the SMEs industry is RM 1,500.00.

As for the years of working, the majority of the respondents with a total of 176 (85.437%) working in the industry between 1 to 9 years. Only 1 respondent has worked in the industry for 44 years.

4.2. Assessment of Measurement Model

There are two stages of measurements in PLS-SEM which were used in this study which are the Reflective Measurement Model and the Structural Model. In the reflective measurement model, the convergent validity and discriminant validity of constructs were measured. For convergent validity, it starts with measuring the outer loading of the observed variables. All outer loadings must have a value > 0.7 as a minimum criterion loading (Ringle, 2006). All observed variables that have a value below 0.7 were deleted. Next, Cronbach’s Alpha value of each construct was calculated. In a model adequate for exploratory purposes, composite reliabilities should be equal to or greater than .6 (Chin, 1998; Höck & Ringle, 2006: pp. 15). As for construct reliability and validity, this study applied a benchmark value for Cronbach’s Alpha, Rho-a and composite reliability equal to or greater than .70 and Average Variance Extracted value of > 0.5 to confirm the convergent validity (Henseler, Ringle, & Sarstedt, 2012: pp. 269). The table below showed all accepted variables to confirm the convergent validity.

Table 3.

Convergent Validity of the Constructs.

Table 3.

Convergent Validity of the Constructs.

| |

AVE |

CR |

Rho-A |

| Internal Brand |

0.649 |

0.881 |

0.825 |

| Corporate Culture |

0.575 |

0.931 |

0.919 |

| Corporate Identity Management (CIM) |

0.574 |

0.89 |

0.853 |

| Employee Brand Support |

0.646 |

0.879 |

0.818 |

Total of 24 indicators of the constructs were accepted and all values are fulfilling the requirement for convergent validity of constructs.

Following that, the discriminant validity of notions was established. The Fornell– Larcker discriminant validity criterion was used to assess the discriminant validity of this investigation. The square root of AVE occurs in the diagonal cells of the Fornell-Larcker criterion table, and correlations appear below it. In absolute value words, discriminant validity exists if the top number (which is the square root of AVE) in any factor column is greater than the numbers (correlations) below it. Cross-loadings are also useful in establishing discriminant validity (Garson, 2016). The first factor in discriminant validity is determining the cross-loading values for all variables. The value of each variable and its indicators must be higher than other variables (Garson, 2016). Thus, this table below showed the cross-loading values for all variables and its indicators.

Table 4.

Cross-Loading Values of Variables.

Table 4.

Cross-Loading Values of Variables.

| |

Internal Brand |

Corporate Culture |

Corporate Identity Management (CIM) |

Employee Brand Support (EBS) |

| IBC2 |

0.736 |

0.587 |

0.591 |

0.326 |

| BTD4 |

0.795 |

0.412 |

0.474 |

0.141 |

| BTD5 |

0.839 |

0.489 |

0.534 |

0.263 |

| BTD6 |

0.849 |

0.486 |

0.592 |

0.315 |

| CC3 |

0.432 |

0.786 |

0.517 |

0.425 |

| CC4 |

0.444 |

0.748 |

0.490 |

0.453 |

| CC5 |

0.439 |

0.720 |

0.401 |

0.333 |

| CC7 |

0.418 |

0.764 |

0.483 |

0.376 |

| CC8 |

0.534 |

0.818 |

0.560 |

0.410 |

| CC9 |

0.536 |

0.765 |

0.542 |

0.395 |

| CC10 |

0.443 |

0.739 |

0.529 |

0.407 |

| CC11 |

0.535 |

0.803 |

0.553 |

0.410 |

| CC12 |

0.467 |

0.733 |

0.526 |

0.405 |

| CC13 |

0.455 |

0.701 |

0.460 |

0.431 |

| MVD7 |

0.581 |

0.469 |

0.727 |

0.273 |

| CII4 |

0.532 |

0.483 |

0.748 |

0.311 |

| VII1 |

0.448 |

0.519 |

0.741 |

0.375 |

| VII2 |

0.564 |

0.551 |

0.812 |

0.366 |

| VII3 |

0.544 |

0.561 |

0.798 |

0.324 |

| VII4 |

0.456 |

0.458 |

0.713 |

0.348 |

| EBS2 |

0.296 |

0.422 |

0.335 |

0.788 |

| EBS3 |

0.224 |

0.407 |

0.343 |

0.798 |

| EBS4 |

0.312 |

0.456 |

0.342 |

0.824 |

| EBS5 |

0.246 |

0.432 |

0.391 |

0.805 |

As shown in the table above, the highlighted values of cross-loading for each variable are significantly higher compared to the others. Thus, the cross-loading values are accepted.

The Fornell–Larcker discriminant validity criteria follow, in which the AVE value is compared to the prior group. Each variable's AVE value must be greater than the previous variable's AVE value in the table. The table illustrates the degree of correlation between the exogenous latent variables. The covariances table is no longer necessary because data has been standardised, making covariances equivalent to correlations (Garson, 2016). The Fornell–Larcker discriminant validity criteria for all variables are shown in the table below.

Table 5.

Fornell–Larcker Discriminant Validity Criterion.

Table 5.

Fornell–Larcker Discriminant Validity Criterion.

| |

Corporate Culture |

Corporate Identity Management (CIM) |

Employee Brand Support (EBS) |

Internal Brand |

| Corporate Culture |

0.758 |

|

|

|

| Corporate Identity Management (CIM) |

0.671 |

0.757 |

|

|

| Employee Brand Support (EBS) |

0.535 |

0.439 |

0.804 |

|

| Internal Brand |

0.622 |

0.689 |

0.336 |

0.806 |

In the table above, it is clear that the AVE value for each variable is well significant compared to the previous AVE value. Thus, the Fornell–Larcker Discriminant Validity Criterion was confirmed. Next, Heterotrait-Monotrait Ratio (HTMT) was confirmed to finally confirm the discriminant validity for all variables in this study. The value of HTMT for each variable must be lower < 0.9 in order for the discriminant validity to be accepted. The table below showed the value of HTMT of this study.

Table 6.

Heterotrait-Monotrait Ratio (HTMT).

Table 6.

Heterotrait-Monotrait Ratio (HTMT).

| HTMT |

Corporate Culture |

Corporate Identity Management (CIM) |

Employee Brand Support (EBS) |

| Corporate Culture |

|

|

|

| Corporate Identity Management (CIM) |

0.755 |

|

|

| Employee Brand Support (EBS) |

0.615 |

0.527 |

|

| Internal Brand |

0.705 |

0.814 |

0.395 |

As shown in the table above, the HTMT value for each variable is well under < 0.9 as per highlighted. Thus, the discriminant validity is confirmed.

4.3. Assessment of Structural Model

Structural model of PLS-SEM in this study started with the Multicollinearity Assessment where inner and outer Variance Inflation Factor value (VIF) is measured. Multicollinearity in Ordinary Least Squares (OLS) regression increases standard errors, renders significance tests of independent variables inaccurate, and inhibits the researcher from determining the relative importance of one independent variable vs another. A popular rule of thumb is that when the variance inflation factor (VIF) coefficient is more than 4.0, serious multicollinearity may arise (some use the more lenient cut-off of 5.0). VIF is the inverse of the tolerance coefficient, and when tolerance is less than.25, multicollinearity is detected (some use the more lenient cut-off of .20). Another indicator as proposed by O, Brien (2017), VIF of 10 or even one as low as 4 (equivalent to a tolerance level of 0.10 or 0.25) have been used as a rule of thumb to indicate excessive or serious multicollinearity. These principles for excessive multicollinearity are famously employed to call into doubt the outcomes of statistically valid investigations.

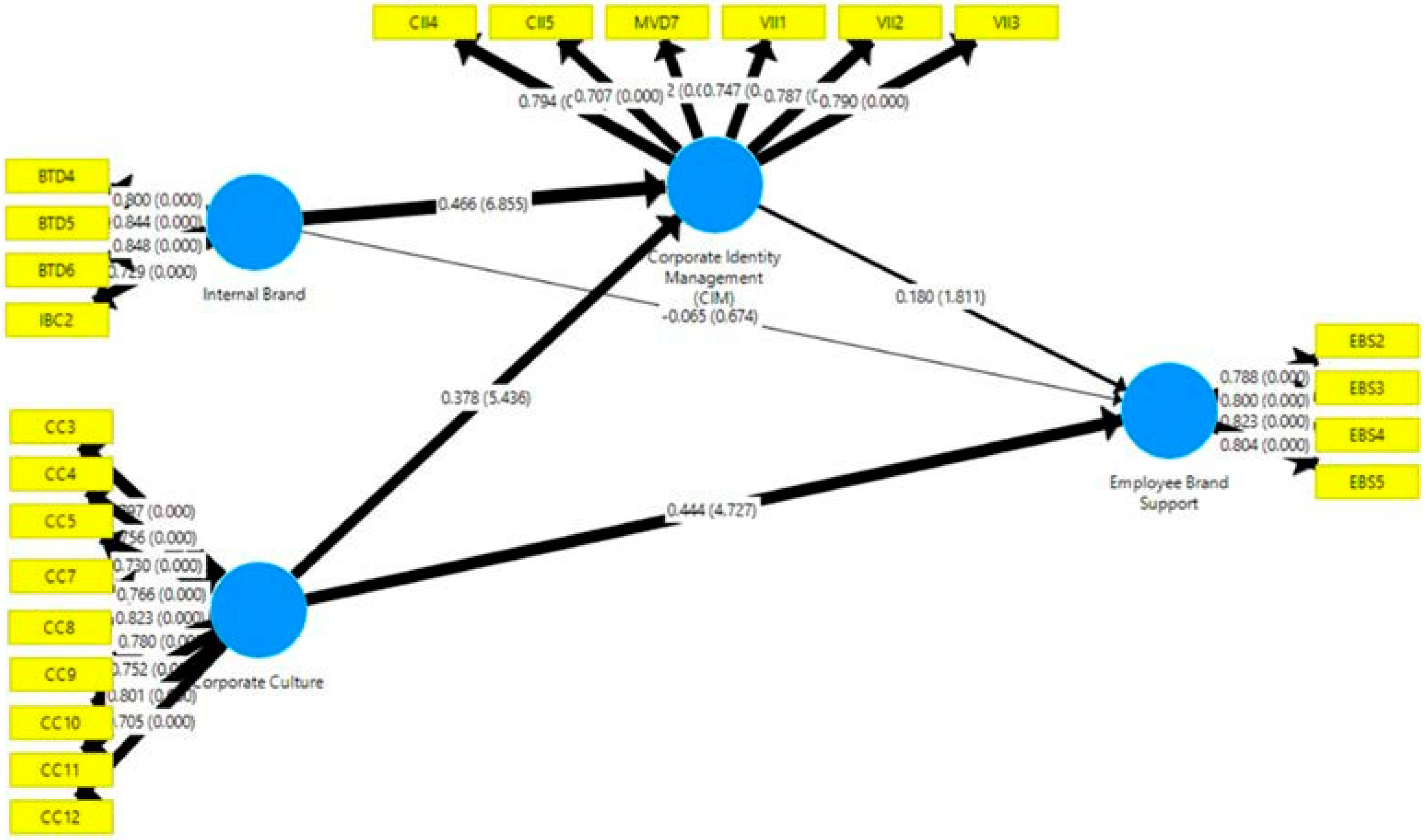

Figure 2.

Structural Model of the Study (source from the study).

Figure 2.

Structural Model of the Study (source from the study).

This study used stricter indicators as proposed by Kock (2015) stating that if all VIFs resulting from a full collinearity test are equal to or lower than 3.3 (≤ 3.3), the model can be considered free of common method bias. This result also indicates that common method bias (CMB) is rejected from this study as mentioned previously.

Next, the bootstrapping process is conducted to measure the Path Coefficient Significance in this study. Structural path coefficients (loadings), illustrated in the path diagram are the path weights connecting the factors to each other. As data are standardised, path loadings vary from 0 to 1. These loadings should be significant. The path is significant if the P-value is lower < 0.05 and the T value is larger > 1.96 (Garson, 2016).

It is predicted that CIM partially mediates the relationships between one of the proposed antecedents which is the internal brand and the consequence in this study. The t- value and p-value through the bootstrapping technique in Smart PLS indicate that there is no significant indirect effect influenced by CIM as the mediation variable in this study. However, to confirm the result further, the variance accounted for (VAF) is calculated to indicate partial mediation in the proposed model. The mediation effect should be analysed further by calculating VAF if no full mediation effect occurs to identify if there is partial mediation in the proposed model (Hair et al., 2017). Based on the result above, it is confirmed that the relationship between internal brand and employee brand support is partially mediated by CIM with a total VAF of 0.531 (0.2 ≤ 0.531 ≤ 0.8).

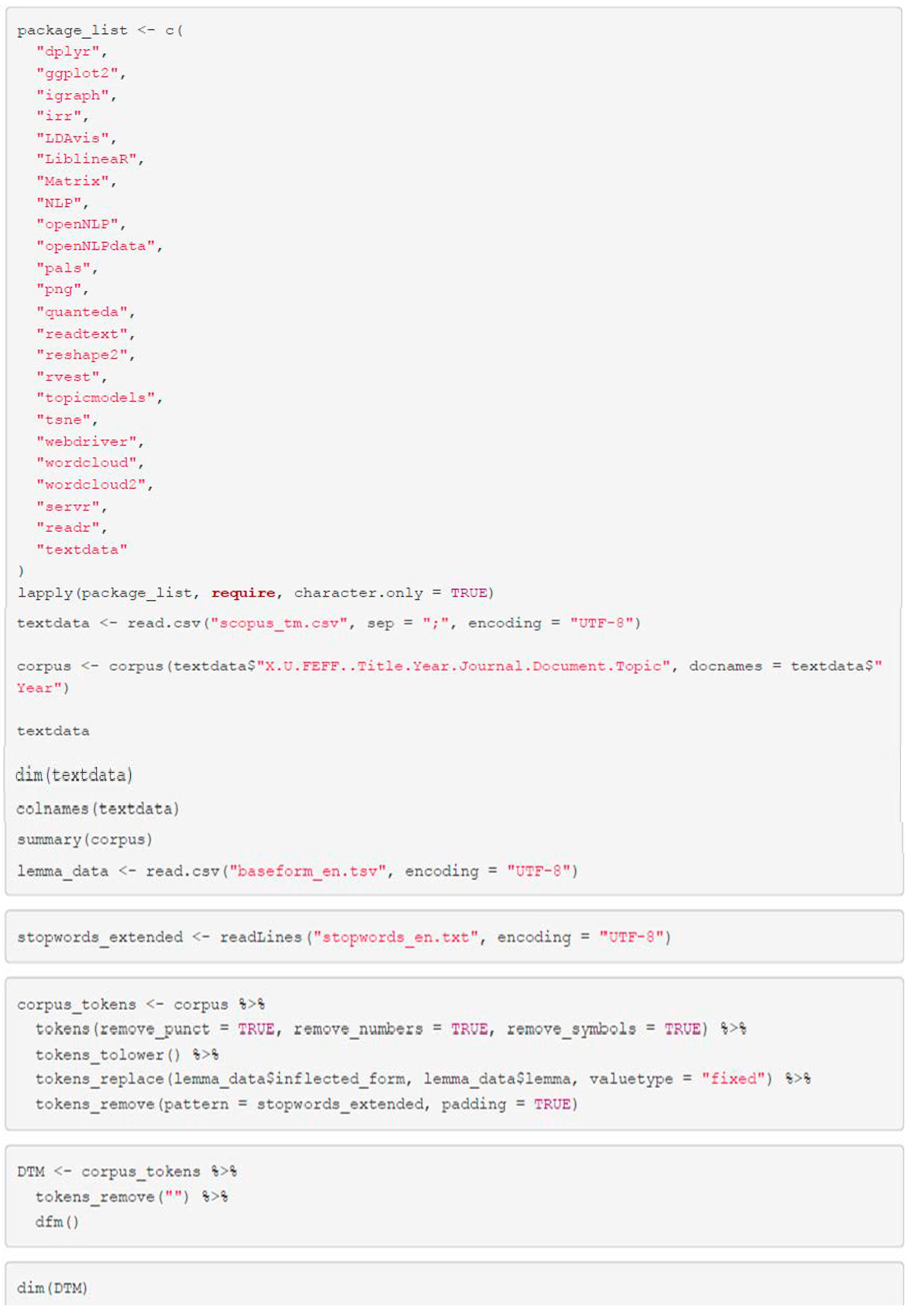

4.4. Knowledge Mining through Machine Learning

The outstanding improvement of AI in machine learning is a revelation to data accessibility, affecting all types of human tasks. The availability of these massive amounts of data spawned new methods for processing and extracting valuable, task-oriented information from them (Kaufman & Michalski, 2005). Knowledge mining is one of the methodologies that gained its foundation in social science studies is the machine-assisted reading of text corpora to discover patterns through recorded knowledge in a database. This methodology is crucial in identifying the evolution patterns of knowledge, confirming discovery and supporting newly explored novelty in research (Karami et al., 2020; Roberts et al., 2019).

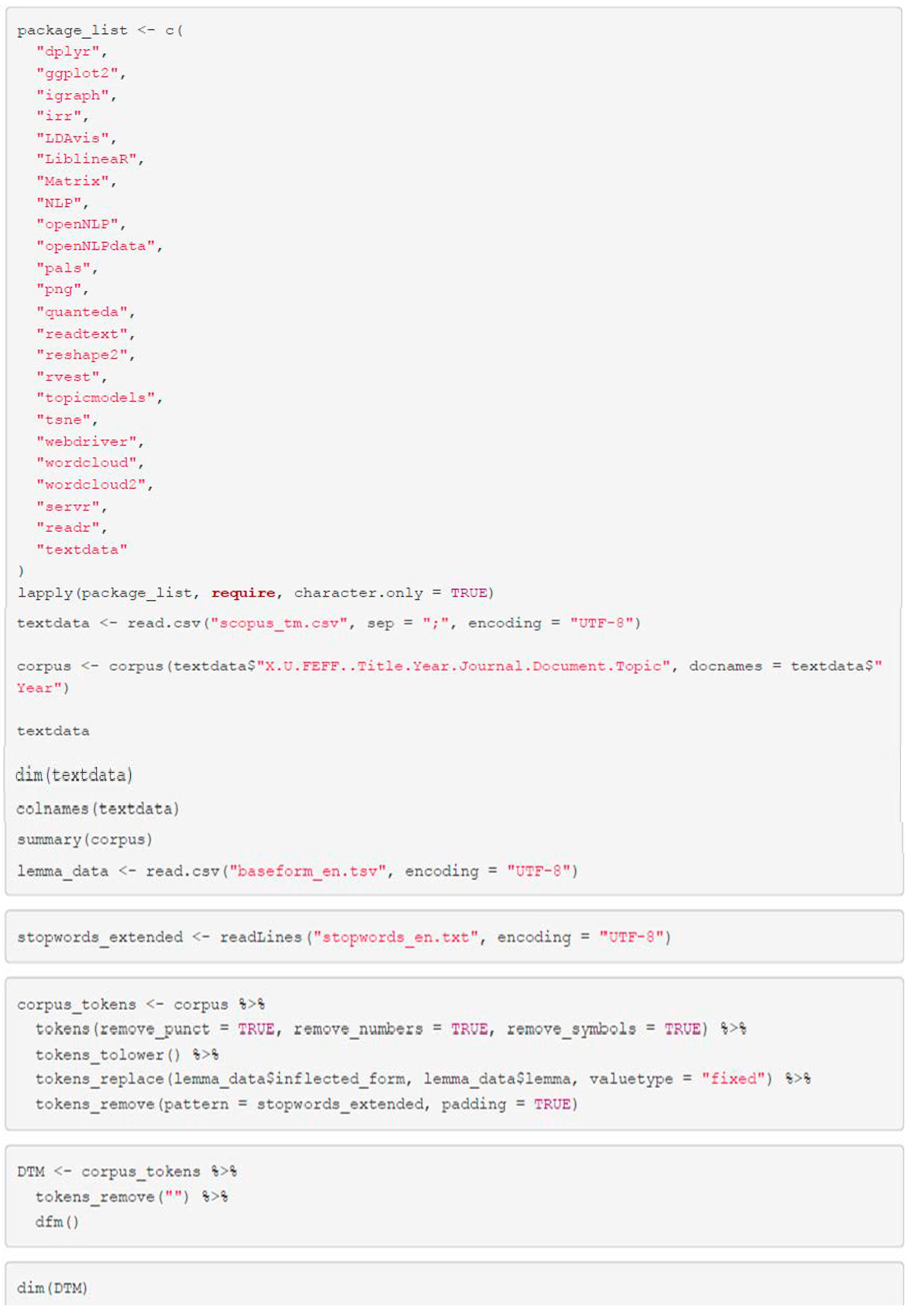

The second data collection method is the knowledge-mining technique of a journal database through the machine learning (ML) technique that was used to mine the massive amount of text data from the Scopus database. Knowledge mining is one of the method- ologies that gained its foundation in social science studies is the machine-assisted reading of text corpora to discover patterns through recorded knowledge in a database. This methodology is crucial in identifying the evolution patterns of knowledge, confirming discovery and supporting newly explored novelty in research (Karami et al., 2020; Roberts et al., 2019, Benchimol et al., 2021). In this study, Knowledge mining is applied in identifying topic patterns of past literature surrounding the Halal field.

Programming language of R for statistical computing and graphics in Integrated Development Environment (IDE) called RStudio (RStudio Team, 2021). There is a combination of packages that have been utilised using R in this study which starts with the creation of text corpus and ends with result visualisation. A total of 1091 articles from the year 1992 – 2021 were able to be retrieved from the Scopus database. Scopus database was the only database used in retrieving the articles with a massive number of articles presence which was enough to identify a strong topic pattern surrounding the Halal field. Only a single keyword was used which was (“halal”) in the articles’ retrieval process since its aim was to retrieve as many articles as possible across all fields of studies.

Topic modeling through Latent Dirichlet Allocation (LDA) in “topic models” of R is used in developing topic models in this study. LDA is the generative probabilistic algorithm developed by Blei et al. in 2003 used in machine learning for collections of discrete data such as text corpora. This three-level hierarchical Bayesian model represents each item in a collection as a finite mixture over an underlying set of subjects. Each subject is thus represented as an infinite mixture over a collection of topic probabilities. The topic probabilities give an explicit representation of a document in the context of text modeling (Blei et al., 2003). The text corpus (a document containing plain unformatted text files) was built in R by configuring the file path's directory source. All articles included are combined into one text corpus. This will ensure the programming software is able to run the process algorithm across all articles without any bias in the number of occurrences of each word (Blei et al., 2003).

Next is the pre-processing stage where the structure of words in the corpus undergoes the cleaning process. All punctuations, extra blank spaces, numbers, stop words, capital letters and signs are eliminated and replaced with the appropriate lowercase and white space. This process is to ensure only valuable words are left in the corpus with a uniform structure. However, if the corpus contains a massive data size, this process needs to be repeated until the corpus is fairly clean and the researcher is able to detect and interpret the word frequency in the document-term matrix.

The next figure shows the developed codes for the pre-processing stage.

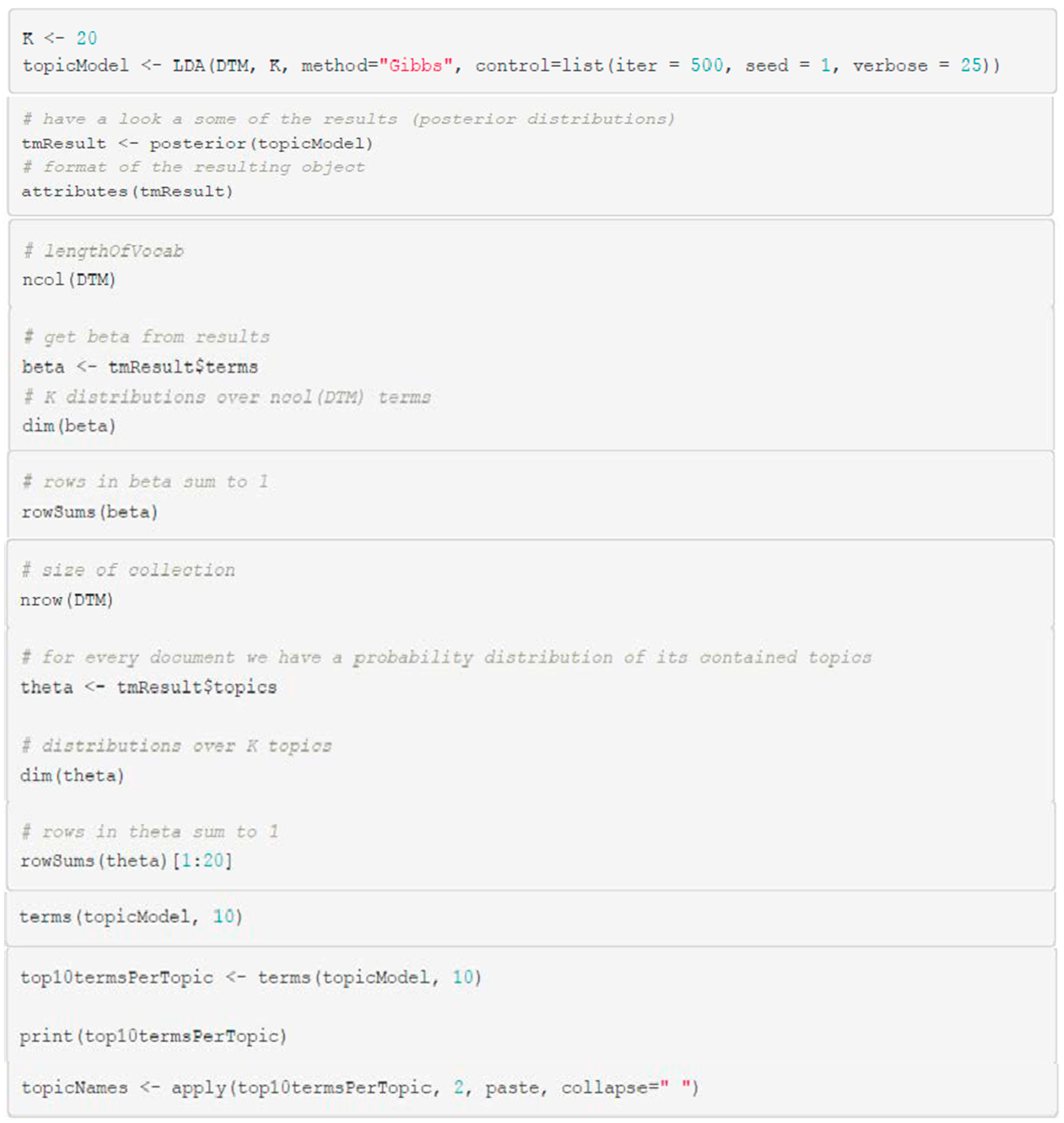

4.5. Topic Modeling

Topic modeling in this study that has been developed through the knowledge mining process has recorded 1091 articles in the Scopus database dated from 1992 until 2021. Mining process was made possible with the R programming language of the machine learning utilisation in this study.

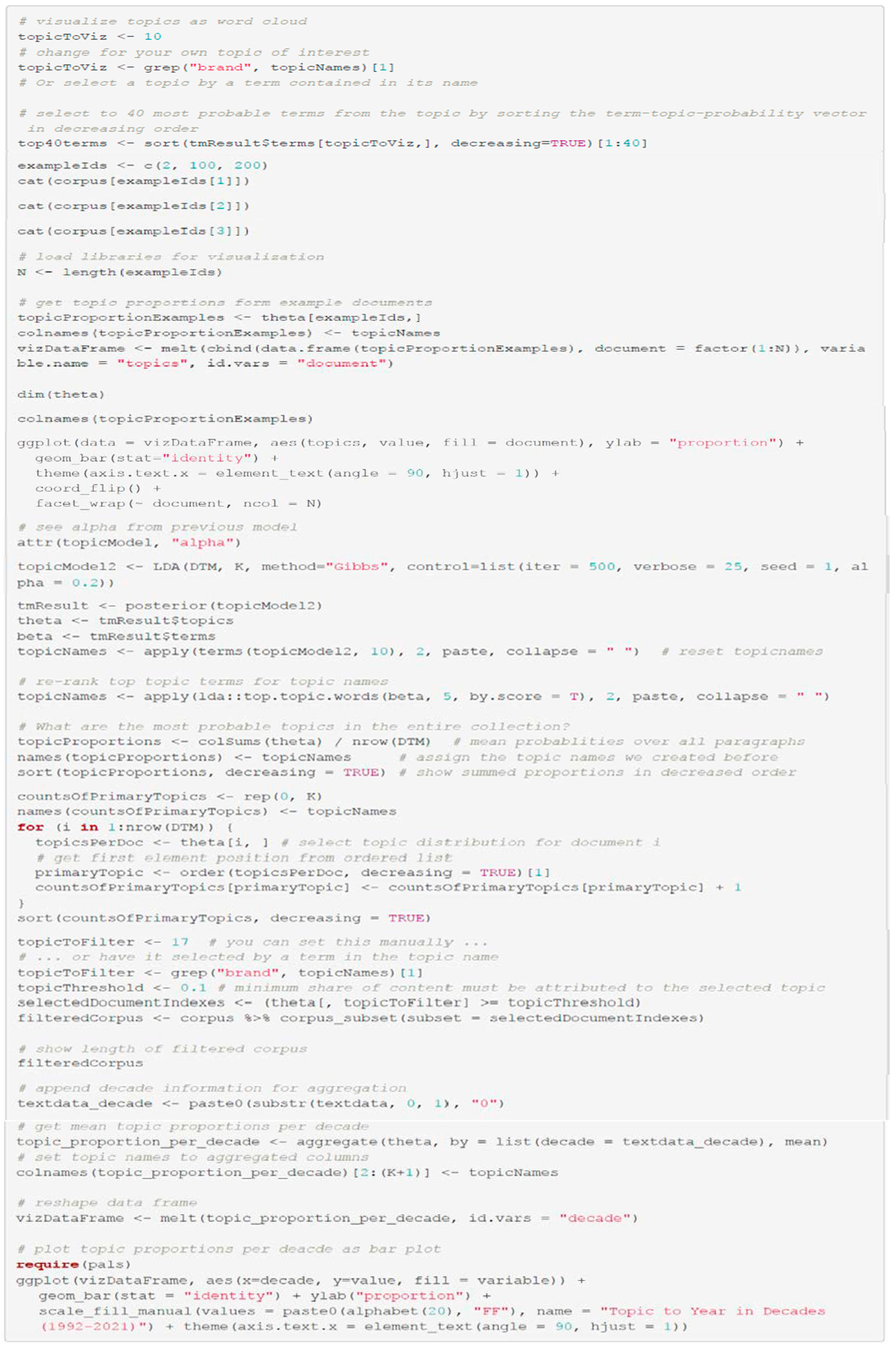

Figure 3.

Developed codes for Topic Modeling.

Figure 3.

Developed codes for Topic Modeling.

‘Gibbs’ sampling algorithm was executed to calculate the estimated topic derived from the document-term matrix. Once the calculation iterations were completed (default iterations are used which is 500) the estimated topics with terms were visualised.

Figure 4.

Developed codes for Topic Modeling visualisation.

Figure 4.

Developed codes for Topic Modeling visualisation.

The results of the developed topic modeling in this study were visualised in cloud words as the first result as shown in the figure below.

Figure 5.

Cloud word visual of estimated topics in Halal.

Figure 5.

Cloud word visual of estimated topics in Halal.

The word cloud above shows the terms that were highly associated with the identity as the topic of studies in Halal field. The top six terms that are highly associated with the topic of identity in the Halal field are brand, consumption, Muslim, image, branding and model. This result indicates that two of the highly associated topics in identity as the topic in Halal are brand and branding which aligned with the result from our structural model assessment. As an outcome of the structural model evaluation, it is projected that CIM partially mediates the interactions between internal brand and employee brand support in this study. However, the link is frail since CIM can only partially moderate the impact of internal brand on employee brand support in Malaysia's Halal food SMEs. The next figure shows the predicted topic proportions to documents to identify the topic proportions in all articles that focus on Malaysia's Halal food SMEs.

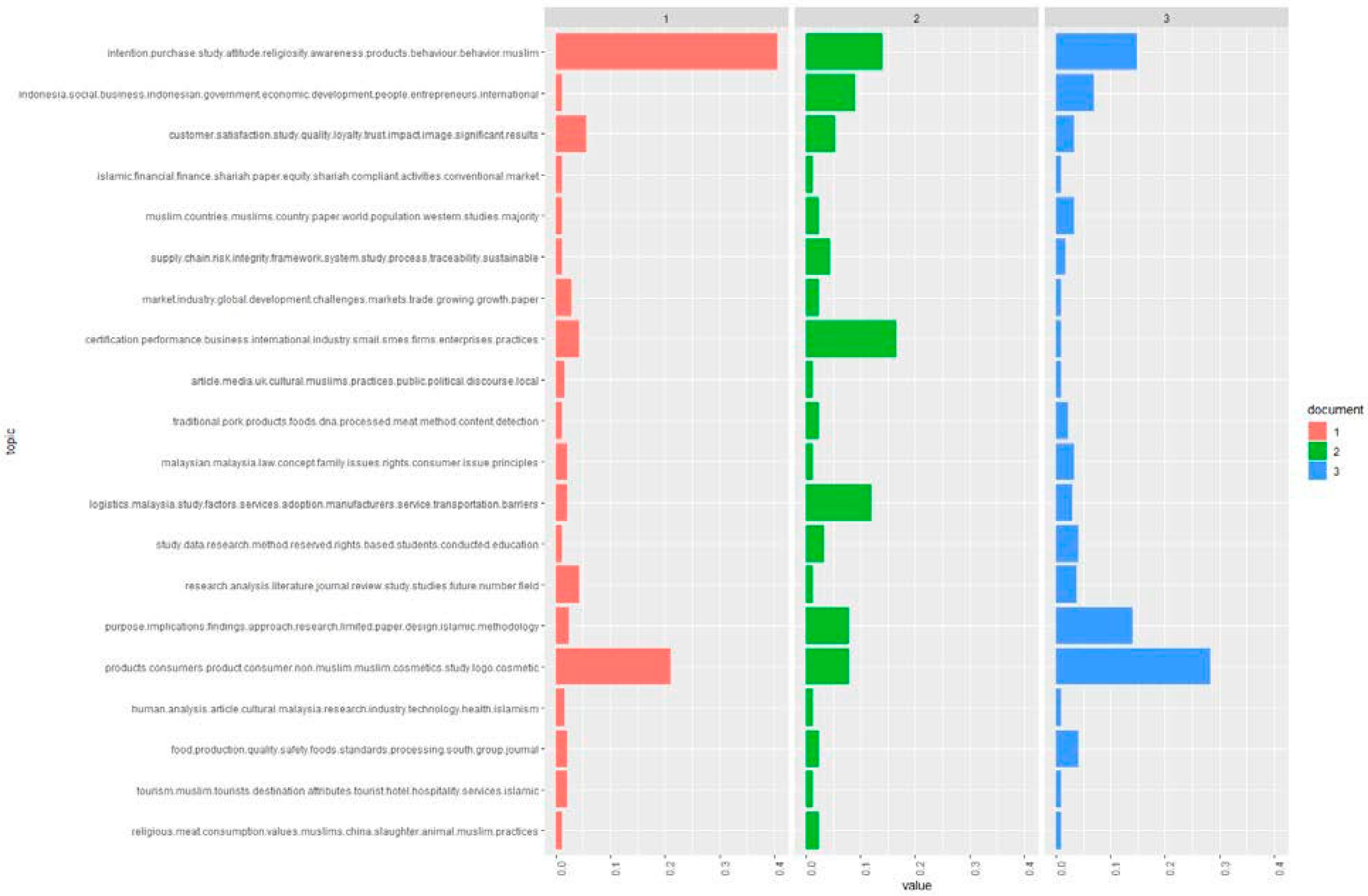

Figure 6.

Topic proportions to documents of estimated topics in Halal SMEs.

Figure 6.

Topic proportions to documents of estimated topics in Halal SMEs.

Based on the figure above, SMEs emerged as the topic together with certification, performance, business and practices in the group of identical documents (highest green bar value in document group 2). In all 1091 articles mined, the identical group of articles were discussing the topic of Halal SMEs the mentioned topics above that emerged together with SMEs in Halal.

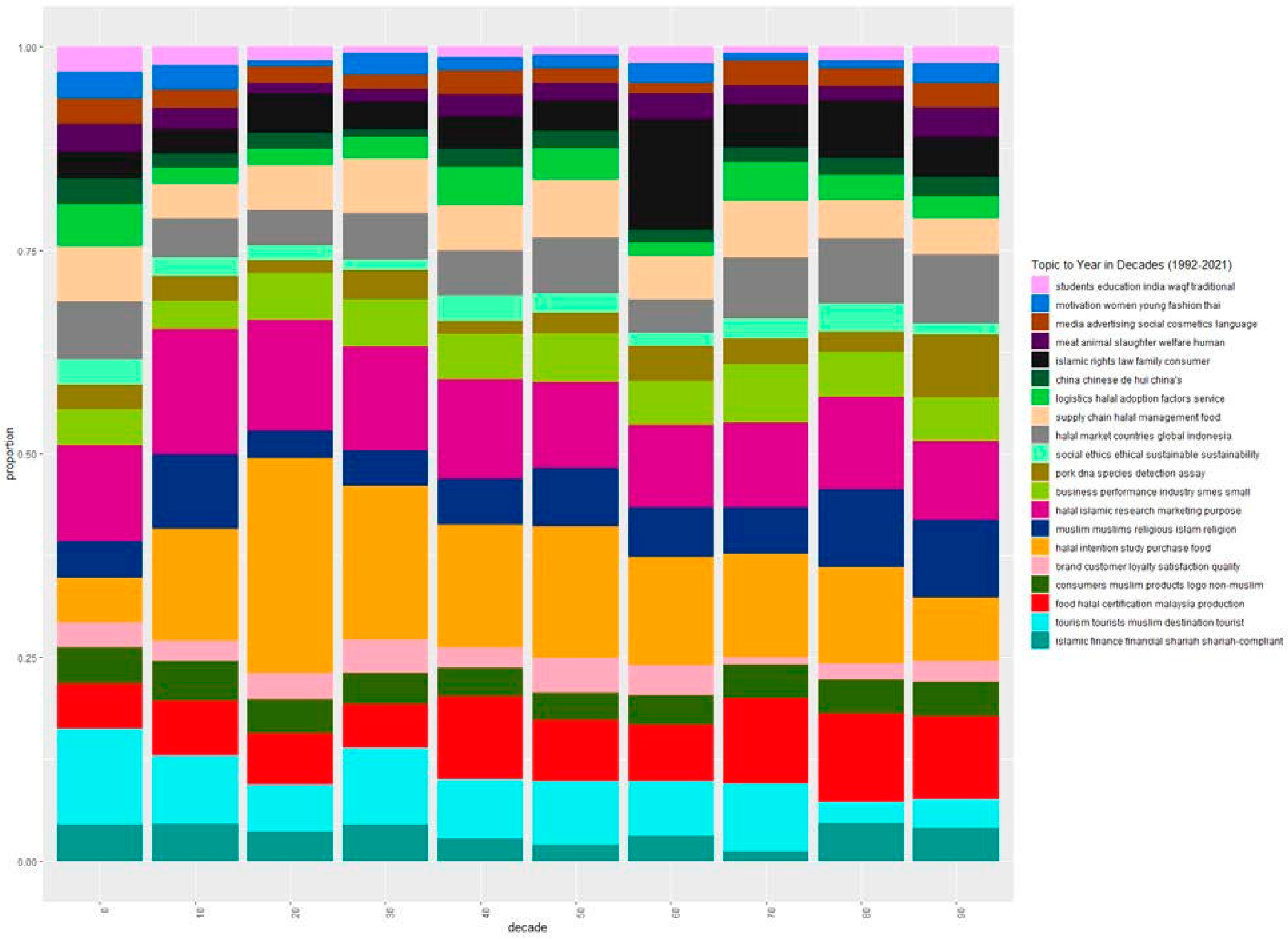

The next figure below visualises the result of the predicted evolution of topic proportions in a one-decade timeline interval. All 1091 articles included in the analysis date earliest in 1992 until now (the year of 2021). The figure below predicts the evolution of the identified topics up to nine decades (90 years). Thus, the focused results should be in the first three columns that represent three decades which the year 1992 until 2021.

Figure 7.

Predicted topic proportions evolution in decade.

Figure 7.

Predicted topic proportions evolution in decade.

From the figure above in Malaysia, the most influential topics that have noticeable predicted proportions on the topic if not the strongest were represented by Halal, intention, purchase and food (orange coloured bar). Topics such as halal, certification, food and production (red coloured bar) were predicted to be revolved in Malaysia. Based on the word cloud figure above identity as the topic was highly associated with the terms brand where the predicted proportions on the topic show a weak evolution pattern (pink coloured bar).

This identified topic pattern clearly shows an evident lack of studies on the Halal brand identity which is not even predicted to be present in Malaysian SMEs. The primary finding of this study, which is the hypothesis testing of the proposed research framework through PLS-SEM data analysis, indicates CIM was predicted to partially mediate the relationship between IB and EBS which aligned with the predicted topic patterns.

5. Discussion

Based on the result yielded from the data analysis process, it is confirmed that CIM does play a mediating role in the proposed relationship. However, the mediation effect is only partially affecting the IB as the antecedent and EBS (consequence). CIM in Malaysia's Halal SMEs setting is not mediating the CC (antecedent) and EBS (consequence).

In-depth discussion regarding this result is strongly related to the literature from past studies which are extensively discussed in Chapter 2 of this study. IB is partially mediated by CIM in affecting the EBS. Basically, all respondents in this study reached a consensus on the importance of internal branding initiatives in equipping them with extensive knowledge on Halal as a brand positioning for the organisation. However, although the majority of respondents agreed on the importance of the mentioned variable, lack of expertise and knowledge on CIM and its dimensions (mission and values dissemination, consistent image implementation, and visual identity implementation). The most fundamental dimension in CIM is mission and values dissemination where the top-level management team in the organisation strategically planned a driving force for the organisation's unique corporate philosophy, which is reflected in its mission, values, and goals (Balmer 1994; Gray and Balmer 1997; Olins 1991). Top-level management’s wisdom, experience and expert knowledge in developing the strategic direction of the organisation which directly reflects its mission, core values that uphold corporate identity in its brand, planned short and long-term goals in sustaining the organisation's brand in the market are massively critical for the survivability of the organisation. The organisation’s hierarchical structure in Malaysia’s Halal industry SMEs is relatively composed of basic functional units such as human resources (HR), finance, and operation. Furthermore, most Halal industry SMEs are controlled by one leading figure in the organisation which is usually the owner and there is no board of directors that comprises an array of expert knowledge and experience. Thus, a single lack of knowledge and experience leader figures in the organisation making all core decisions indecisively without any form of review from a group of members. Therefore, creating a dilemma in their identity and ultimately deterring the organisation’s marketing strategy (Elasraq, 2016). The further challenge that emerges from this is the lack of attention given to developing and enhancing the consistent image implementation and visual identity implementation in the halal manufacturing industry which is the most apparent problem in the halal industry. A weak direction set by the leader resulted in confusion in the organisation's brand identity causing the reluctance of the employees to adapt to the system in internal communication (Ab Talib et al., 2015). It is concluded that in Malaysia’s Halal industry SMEs are still structurally weak in terms of setting the course of the organisation in its mission and values dissemination by top- level figures since lack of experienced experts, particularly in CIM. Even with a good level of awareness amongst employees on the importance of IB, confusion and reluctance exist thus making them not able to fully understand the organisation’s brand and not able to comprehend the message on brand identity which has mostly been neglected in the internal communication system.

CC is not mediated by CIM in affecting EBS based on the result of data analysis in this study. A good corporate culture in an organisation only able to be achieved through a consistent practice of good governance in brand identity since organisational culture is a complex phenomenon that moulds everyday organisational life that only can be achieved through the course of time that creates many success stories (Barney, 1986; Coleman, 2013; Schein, 1999). This is a massive challenge facing Malaysia's Halal industry SMEs.

Corporate culture is a foreign term in Halal SMEs since there is a lack of adequate quality improvement in their company practices (Hardin et al., 2019). The vast majority of Malaysia’s Halal industry SMEs are facing this massive adequality caused by two major factors which are lack of financial strength to hire an experienced workforce to manage organisation’s brand identity and misplaced enforcement power to the inarticulate governing body in managing the Halal brand values. Malaysia has recently been challenged by the latest controversy involving imported frozen foods bearing a forged Halal label. On December 28, 2020, Saiful Yazan Alwi, Director-General of the Malaysian Quarantine and Inspection Services Department (MAQIS), said in a local TV interview that 122,000 tonnes of frozen halal meat were legally imported into the nation between January and November of this year (Abdullah, 2020). This newest controversy involving imported meats bearing a bogus Halal logo has sparked outrage among Malaysia's Muslim com- munity, which constitutes the majority of the population.

The Muslim community in Malaysia started questioning the role of law enforcement and JAKIM was heavily criticized by them and been labelled incompetent. This scandal is heavily scrutinised by international media agencies such as The Straits Times, Arab Newsand Bloomberg. The image and reputation of Malaysia which was considered as one of the forefronts in the Global Halal industry was shattered and lost global confidence in the Malaysian Halal certification system (Whitehead, 2021). Malaysian Halal certification laws are already holistically adequate in determining the Halal status of a product. However, a major flaw can be seen in the delegation of enforcement power and awareness of the responsibilities of authority agencies (Abdullah, 2020). A lack of clarity by officials creates major confusion on Halal food companies on how they should respond to this scandal adding more scars to Malaysian Halal brand values (Whitehead, 2021). A major crisis such as this will jeopardise the organisational image and reputation that have been built throughout decades and desirable proper, or appropriate brand of Malaysian Halal values was tainted since brand values are heavily embedded with the socially constructed system of norms, values, beliefs and definitions included in culture (Kates, 2004; Bravo, Buil, Chernatony & Martinez 2017; Barney, 1986 & Schein, 1999; Kapferer, 1992).

The latest scandal involving Malaysian Halal brand values indicates there is a need for a major overhaul in the delegation of power in managing and monitoring all aspects in the Halal industry that will massively influence the corporate culture of involved authorised governing bodies and Malaysian Halal industry SMEs. This will decide the fate of Malaysian Halal brand image and reputation since its identity is heavily questioned not only by Muslim-majority locals but also by the global stakeholders as well.

To achieve a good internal brand understanding to all internal members of the organisation, good governance in CIM must be achieved through strategic planning and consistent communication efforts (Coleman, de Chernatony & Christodoulides, 2011; Buil, Catalan, & Eva Martínez, 2016).

Based on the data analysis, it is predicted that there is no direct relationship between IB (antecedent) with EBS (consequence). This study concluded that most respondents in this study agreed that an effective internal brand activity was mediated by CIM. However, because of the lack of infrastructure, expertise and investment from SMEs in Malaysia’s Halal industry in developing and acquiring resources in managing corporate identity, CIM was unable to function optimally in Malaysian Halal industry SME settings. Thus, this indicates a major weakness in Malaysia’s Halal SMEs in managing their brand.

CIM relies heavily on the abundance of resources, especially in financial, workforce, and expertise to develop an appealing and favourable corporate design for industry identity, hiring expertise for managing and monitoring organisational communication process, consistently instilling good governance in corporate culture in which resulting in nurturing commendable behaviour amongst internal members, providing state-of-the-art structure to support communication system, and appointing experience top-level management members in deciding the long term roadmap of the organisation (Melewar, 2003; Maurya, Mishra, Anand & Kumar, 2015; Witt & Rode, 2005; Maurya, Mishra, Anand & Kumar, 2015; Melewar & Karaosmanoglu, 2006; Batraga, & Rutitis, 2012). With the current condition and ability of most SMEs in the Malaysian Halal industry, the mentioned conducive settings will not be achievable caused by a gargantuan challenge for SMEs to pro- vide enough capital for investment.

In the current market scenario, CIM is heavily relying on technological adaptation in infrastructure that needs to be built by the organisation to create and maintain good communication in the organisation. This is crucial to nurture a good corporate culture the pursuit of consistent expression on the brand image through the communication effort (Melewar, 2003; Maurya, Mishra, Anand & Kumar, 2015; Simoes, Dibb & Fisk, 2005; Melewar & Karaosmanoglu, 2006; Batraga, & Rutitis, 2012; Coleman, de Chernatony & Christodoulides, 2011; Buil, Catalan, & Eva Martínez, 2016).

6. Conclusions

The results yielded from this study have implications for the relationship between stakeholders in the Malaysian Halal industry SMEs. The results of this study can come out with a strong prediction with the support from past literature from the application of machine learning through knowledge mining in developing the topic modeling.

From the study that has been conducted, there are vast numbers of opportunities for future researchers to study. This study is predicting the CIM model in mediating the an- tecedents' influence of the consequence. If the proposed environment model is accepted to be used as a blueprint for halal management, a follow–up study needs to be done to empirically prove the benefits of having a good CIM.

It is suggested to future researchers also to replicate this study by expanding it to different antecedents such as crisis management, employee motivational factors and lead- ership quality in providing brand support to the employees in Malaysian Halal industry SMEs by having that, the basic infrastructures and supports from authority bodies are sufficient for CIM to be adapt and adopt by SMEs.

References

- Ab Talib, M. S., Abdul Hamid, A. B., & Chin, T. A. (2015). Motivations and limitations in implementing Halal food certification: A Pareto analysis. British Food Journal, 117(11). https://www.emeraldinsight.com/doi/abs/10.1108/eb026897.

- Baker, M. J., & Balmer, J. M. T. (1997). Visual identity: Trappings or substance? European Journal of Marketing, 31(5/6), 366–382. [CrossRef]

- Batraga, A., & Rutitis, D. (2012). Corporate identity within the health care industry. Economics and Management, 17, 1545–1551. [CrossRef]

- Benchimol, J., Kazinnik, S., & Saadon, Y. (2021). Text mining methodologies with R: An application to central bank texts. [CrossRef]

- Blei, D. M., Ng, A. Y., & Jordan, M. I. (2003). Latent Dirichlet Allocation. J. Mach. Learn. Res., 3(null), 993–1022.

- Buil, I., Catalán, S., & Martínez, E. (2016). The importance of corporate brand identity in business management: An application to the UK banking sector. BRQ Business Research Quarterly, 19, 3–12. [CrossRef]

- Burmann, C., & König, V. (2011). Does internal brand management really drive brand commitment in shared-service call centers? Journal of Brand Management, 18(6), 374– 393. [CrossRef]

- Burmann, C., & Zeplin, S. (2005). Building brand commitment: A behavioural approach to internal brand management. Brand Management, 12(4), 279–300. [CrossRef]

- Cochran, L. (1994). What is a career problem? The Career Development Quarterly,. [CrossRef]

- Coleman, D., de Chernatony, L., & Christodoulides, G. (2011). B2B service brand identity: Scale development and validation. Industrial Marketing Management, 40(7), 1063–1071. [CrossRef]

- Cornelissen, J., & Elving, W. (2003). Managing corporate identity: An integrative framework of dimensions and determinants. Corporate Communications: An International Journal, 8, 114– 120. [CrossRef]

- Demenint, M. I., van der Vlist, R., Allegro, J. T., Boonstra, J. J., Demenint, M. I., & Steensma, O. (1989). Organizations in a dynamic world. Organiseren En Veranderen in Een Dynamische Wereld, 15–31.

- Elasrag, H. (2016). Halal industry: Key challenges and opportunities. SSRN Electronic Journal, 1-33.

- Erkmen, E., & Hancer, M. (2015). Do your internal branding efforts measure up?: consumers’ response to brand supporting behaviours of hospitality employees. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 27, 878-895. [CrossRef]

- Einwiller, S., & Will, M. (2002). Towards an integrated approach to corporate branding- Findings from an empirical study. Corporate Communications: An International Journal, 7 (2), 100–109. [CrossRef]

- Fathi, E., Zailani, S., Iranmanesh, M., & Kanapathy, K. (2016). Drivers of consumers’ willingness to pay for halal logistics. British Food Journal, 118(2), 464–479.

- Gambetti, R. C., Melewar, T. C., & Martin, K. D. (2017). Guest editors’ introduction: Ethical management of intangible assets in contemporary organizations. Business Ethics Quarterly, 27(3), 381–392. [CrossRef]

- Garson, G. D. (2016). Validity & Reliability, 2016 Edition. Asheboro, NC: Statistical Associates Publishers.

- Goodman, E., & Loh, L. (2011). Organizational change: A critical challenge for team effectiveness. Business Information Review, 28(4), 242–250. [CrossRef]

- Hair, J. F., Ringle, C. M., & Sarstedt, M. (2011). PLS-SEM: Indeed a silver bullet. Journal of Marketing theory and Practice, 19(2), 139-152. [CrossRef]

- Hair, J. F., Sarstedt, M., Ringle, C. M., & Mena, J. A. (2012). An assessment of the use of partial least squares structural equation modeling in marketing research. Journal of the academy of marketing science, 40(3), 414-433. [CrossRef]

- Hardin, Suriadi, Dewi, I. K., Yurfiah, Nuryadin, C., Arsyad, M., Darwis, Akhsan, Diansari, P., & Nurlaela. (2019). Marketing of innovative products for environmentally friendly small and medium enterprises. IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science, 235(1). [CrossRef]

- Hatch, M. J., & Schultz, M. (2001). Are the strategic stars aligned for your corporate brand. Harvard Business Review, 79(2), 128–134.

- Hazelkorn, E. (2007). The impact of league tables and ranking systems on higher education decision making. [CrossRef]

- Retrieved from https://doi.org/https://doi.org/ https://doi.org/10.1787/hemp-v19art12- en. [CrossRef]

- Henseler, J., Dijkstra, T. K., Sarstedt, M., Ringle, C. M., Diamantopoulos, A., Straub, D. W., ... & Calantone, R. J. (2014). Common beliefs and reality about PLS: Comments on Rönkkö and Evermann (2013). Organizational research methods, 17(2), 182-209. [CrossRef]

- Henseler, J., Hubona, G., & Ray, P. A. (2016). Using PLS path modeling in new technology research: updated guidelines. Industrial management & data systems.

- Henseler, J., Ringle, C. M., & Sarstedt, M. (2016). Testing measurement invariance of composites using partial least squares. International marketing review. [CrossRef]

- Henseler, J., Ringle, C. M., & Sarstedt, M. (2015). A new criterion for assessing discriminant validity in variance-based structural equation modeling. Journal of the academy of marketing science, 43(1), 115-135. [CrossRef]

- Henseler, J., Ringle, C. M., & Sinkovics, R. R. (2009). The use of partial least squares path modeling in international marketing. In New challenges to international marketing. Emerald Group Publishing Limited.

- Ind, N. (1997). The corporate brand. In The corporate brand (pp. 1–13). London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Ind, N. (2007). Living the brand: How to transform every member of your organization into a brand champion. Kogan Page Publishers.

- Ivy, J. (2001). Higher education institution image: A correspondence analysis approach. International Journal of Educational Management, 15(6), 276-282. [CrossRef]

- Judson, K. M., Gorchels, L., & Aurand, T. W. (2006). Building a university brand from within: A comparison of coaches’ perspectives of internal branding. Journal of Marketing for Higher Education, 16(1), 97– 114. [CrossRef]

- Karami, A., Lundy, M., Webb, F., & Dwivedi, Y. K. (2020). Twitter and Research: A Systematic Literature Review through Text Mining. IEEE Access, 8, 67698–67717. [CrossRef]

- Kurth, L., & Glasbergen, P. (2017). Full-Serving a heterogeneous Muslim identity? Private governance arrangements of halal food in the Netherlands. Agric Hum Values, 34, 103–118. [CrossRef]

- Mariam, A. (2006). Halal certification and import requirements in Malaysia. 2nd International Halal Food Conference, Malaysia.

- Maurya, U. K., Mishra, P., Anand, S., & Kumar, N. (2015). Corporate identity, customer orientation and performance of SMEs: Exploring the linkages. IIMB Management Review, 27(3), 159–174. [CrossRef]

- Masrom, N. R., Rasi, Z., At, B., & Daut, T. (n.d.). Issue in Information Sharing of Halal Food Supply Chain. [CrossRef]

- Melewar, T. C., Foroudi, P., Gupta, S., Kitchen, P. J., & Foroudi, M. M. (2017). Integrating identity, strategy and communications for trust, loyalty and commitment. European Journal of Marketing, 51(3), 572–604. [CrossRef]

- Melewar, T. C., Karaosmanoglu, E., & Paterson, D. (2005). Corporate identity: Concept, components and contribution. Journal of General Management, 31(1), 59–81. [CrossRef]

- Melewar, T. C. (2003). Determinants of the corporate identity construct: A review of the literature. Journal of Marketing Communications, 9(4), 195–220. [CrossRef]

- Melewar, T. C., & Jenkins, E. (2002). Defining the corporate identity construct. Corporate Reputation Review, 5(1), 76–90. [CrossRef]

- Mohd Shahwahid, F., Abdul Wahab, N., Syed Ager, S. N., Abdullah, M., Abdul Hamid, N. ‘Adha ’Adha, Saidpudin, W., Miskam, S., Othman, N., Syed Ager, Syaripah Nazirah Abdullah, M., Abdul Hamid, N. ‘Adha ’Adha, Saidpudin, W., Surianom, M., & Othman, N. (2015). Peranan Agensi Kerajaan Dalam Mengurus Industri Halal di Malaysia. World Academic and Research Congress, December, 224– 239.

- Naude, P., & Ivy, J. (1999). The marketing strategies of universities in the United Kingdom. International Journal of Educational Management, 13(3), 126-134.

- Noordin, N., Noor, N. L. M., Hashim, M., & Samicho, Z. (2009). Value Chain of Halal Certification System: A Case of the Malaysia Halal Industry. European and Mediterranean Conference on Information Systems 2009 (EMCIS2009),2009(2008), 1–14.

- Noordin, N., Noor, N. L. M., & Samicho, Z. (2014). Strategic Approach to Halal Certification System: An Ecosystem Perspective. Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences, 121,79–95. [CrossRef]

- O'Brien, R. M. (2017). Dropping highly collinear variables from a model: why it typically is not a good idea. Social Science Quarterly, 98(1), 360-375. [CrossRef]

- Olins, W. (2017). The new guide to identity: How to create and sustain change through managing identity. United Kingdom: Routledge. [CrossRef]

- Ouchi, W. G. (1981). Organizational paradigms: A commentary on Japanese management and Theory Z organizations. Organizational Dynamics, 9(4), 36–43. [CrossRef]

- Pauzi, N., & Man, S. (2018). Perkembangan pentadbiran pensijilan halal di Malaysia 1974- 2016: satu tinjauan. 5(1), 1–7. [CrossRef]

- Pranjal, P., & Sarkar, S. (2020). Corporate brand alignment in business markets: A practice perspective. Marketing Intelligence and Planning, 38(7), 907-920.

- Roberts, M. E., Stewart, B. M., & Tingley, D. (2019). Stm: An R package for structural topic models. Journal of Statistical Software, 91(2). [CrossRef]

- RStudio Team. (2021). RStudio: Integrated Development Environment for R. http://www.rstudio.com/.

- Rutitis, D., Batraga, A., Skiltere, D., & Ritovs, K. (2014). Evaluation of the Conceptual Model for Corporate Identity Management in Health Care. Procedia - Social and Behavioural Sciences. [CrossRef]

- Safiullin, L. N., Galiullina, G. K., & Shabanova, L. B. (2016). State of the market production standards ‘halal’ in Russia and Tatarstan: Hands-on review. Academy of Marketing Studies Journal, 20, 88–95.

- Saifuddeen, M., & Sobian, A. (2006). Food and technological progress: An Islamic perspective. Malaysia: MPH Group Publication.

- Schein, E. (2010). Organizational culture and leadership. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass. Schiffenbauer, A. (2001). Study all of a brand’s constituencies. Marketing News, 35(11), 17.

- Schmidt, R. (1995). Consciousness and foreign language learning: A tutorial on the role of attention and awareness in learning. Attention and Awareness in Foreign Language Learning, 9, 1–63.169.

- Schultz, M., & Ervolder, L. (1998). Culture, identity and image consultancy: crossing boundaries between management, advertising, public relations and design. Corporate Reputation Review, 2(1), 29–50.

- Schwepker, C. H., & Good, D. J. (2007). Sales management’s influence on employment and training in developing and ethical sales force. Journal of Personal Selling and Sales Management, 27(4), 325–339.

- Schwepker, C. H., & Hartline, M. D. (2005). Managing the ethical climate of customer-contact service employees. Journal of Service Research, 7(4), 377–397. [CrossRef]

- Sedgwick, P. (2015). Multistage sampling. British Medical Journal (Online), 351(July), 1–2. Simões, C., Dibb, S., & Fisk, R. P. (2005). Managing corporate identity: An internal perspective. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 33(2), 153–168. [CrossRef]

- Simões, C., & Sebastiani, R. (2017). The nature of the nelationship between corporate identity and corporate sustainability: Evidence from the tetail industry. Business Ethics Quarterly, 27(03), 423– 453. [CrossRef]

- Tooley, J., Dixon, P., & Stanfield, J. (2003). Delivering better education: Market solutions to education. Adam Smith Institute Better Education Project.

- Tosti, D. T., & Stotz, R. D. (2001). Brand: Building your brand from the inside out. Marketing Management, 10(2), 28.

- Tourky, M., Kitchen, P., & Shaalan, A. (2020). The role of corporate identity in CSR implementation: An integrative framework. Journal of Business Research, 117(January 2018), 694–706.

- Urde, M. (2003). Core value based corporate brand building. European Journal of Marketing, 7, 1017- 1040.

- Vallaster, C. (2004). Internal brand building in multicultural organisations: A roadmap towards action research. Qualitative Market Research: An International Journal, 7, 100-113. [CrossRef]

- Vallaster, C., & de Chernatony, L. (2004). How much do leaders matter in internal brand building?An international perspective. The Icfaian Journal of Management Research, III (12), 71-81.

- Vallaster, C., & De Chernatony, L. (2005). Internationalisation of services brands: The role of leadership during the internal brand building process. Journal of Marketing Management, 21(1–2), 181–203. [CrossRef]

- Whisman, R. (2009). Internal branding: A university’s most valuable intangible asset. Journal of Product & Brand Management, 18(5), 367-370.

- Winship, C. (1992). Models for sample selection bias. Annual Review of Sociology, 18(1), 327–350. [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y., Stafford, T. F., & Gillenson, M. (2011). Satisfaction with employee relationship management systems: The impact of usefulness on systems quality perceptions. European Journal of Information Systems, 20(2), 221–236. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).