1. Introduction

Many rural areas are now being challenged as never before by urban sprawl and agricultural restructuring [

1]. To revive rural areas, rural tourism has been described as an approach to revitalize rural space in developed countries and regions such as Japan, Australia, and France, and more recently in China, Romania, Mexico, and other developing countries and regions [

2,

3,

4,

5]. Rural tourism is adopted by peripheral areas to achieve socio-economic regeneration and development that can benefit all communities in rural spaces [

6]. Accordingly, rural tourism has been increasingly considered and applied as a silver bullet to creating leisure space [

3], exploring sustainable development opportunities [

7], inheriting local cultures [

8], conserving heritage, and protecting ecology [

2]. More recently, the outbreak of the Coronavirus disease (COVID) pandemic highlighted the need for rural tourism for domestic and local communities due to disrupted international tourism and travel [

9].

Tourists are attracted to rural areas by a wide range of natural and cultural resources, associated infrastructure, interpretative facilities, and provided goods and services [

9,

10]. Although culture and tourism are always inextricably linked [

11,

12], it is believed that deliberately integrating culture into rural tourism can add more attractions, such as folklore and valued landscapes, to existing natural landscapes, and this has been more broadly and increasingly adopted [

13,

14]. Additionally, cultural integration also preserves traditional and local cultures and merges them with the modern world to co-produce new products, services, knowledge, and skills [

15,

16,

17].

However, cultural integration is not always successful. For example, the development of cultural tourism in Bali, especially the Benoa Bay reclamation project, has destroyed the local culture in many aspects, including traditional buildings and sacred locations for Indigenous ceremonies [

18]. Cultural tourism has shown no respect for local communities and the country, and local people feel that they and their cultures are a public display of bodies, similar to animal tourism in zoos and aquariums [

18].

Some poorly directed attempts at integration have damaged or destroyed original natural resources and traditional cultures. For example, trophy hunting was introduced in Khunjerab National Park in Pakistan as a sustainable approach that could both enhance the local peoples’ livelihood and conserve ecology [

19]. However, the trophy hunting has been poorly managed and the wildlife has been harvested unsustainably. In addition, it has unbalanced the food chain and disturbed the wildlife habitats, increasing human–wildlife conflicts, including between local villagers and snow leopards [

19].

Some cultural integration practices have not helped the conservation of natural landscapes or culture inheritance but have destroyed original cultural historic sites and resilient ecosystems. For example, the Xiagei Hot Spring in Shangri-La County, China, is a typical geological landscape formed by a hot spring and is known for its marvelous spectacles, such as the hot gas injection hole. However, without a clear understanding of the geological structure, tourism developers attempted to turn the air jet hole into a “sauna” and destroyed the hot gas injection area, resulting in serious damage to the rare geological landscape [

20]. In addition, Fjaðrárgljúfur (also known as feather river canyon) in southeast Iceland has experienced increased vandalism, littering, and noise caused by the growth in tourism, especially after the release of

Game of Thrones in 2017 [

21]. Some local people have also been priced out of the housing market due to increasing housing prices and more buyers [

21].

Approaches such as integrated rural tourism [

22] and community-led tourism [

23] have been proposed to empower or center the local community in planning and managing tourism development to integrate cultures sustainably and in parallel with territory development, culture inheritance, and ecology conservation [

24,

25]. Empowering local communities has become another silver bullet and differs from managing competing values among diverse stakeholders in tourism development. Although most included studies have reported the benefits of cultural integration in rural tourism, the reported successful cases may only represent a small proportion of all cultural integration cases. The cases that have been relatively less reported may require at least the same amount of attention, which is the reason a scoping review study is urgently needed.

Integrating culture into rural tourism is multifaceted [

24,

26]. Local communities have often been regarded as homogeneous, and different internal voices are selectively presented or re-interpreted by powers, such as local governments and capitalists [

23,

26]. Uncovering why and how culture has been integrated helps us to identify the winners and losers of tourism development and further explore more just approaches to developing tourism.

This study aims to dismantle the homogeneous view of cultural integration in rural tourism and asks three questions. First, what are the aims and motives of each stakeholder to integrate cultural concepts into rural tourism? Second, who has participated in the cultural integration process and what are their attitudes? Third, how have cultures been integrated into rural tourism? Discussing these three questions helps to advance the understanding of rural tourism and its management by exploring the complex attitudes of and the interactions among different stakeholders. The rest of this paper is divided into four parts. First, a general overview of the considerations and practices of integrating culture into rural tourism and different themes of cultural integration in different countries and regions are presented. Second, the roles of a range of stakeholders participating in tourism management and how they affect cultural integration in tourism are identified. Third, examples of cultural integration into rural tourism from the available literature are categorized into three levels. The paper finishes by synthesizing the findings and providing policy implications.

2. Materials and Methods

Scoping studies (or reviews) are an increasingly popular approach to reviewing evidence to convey the breadth and depth of a field [

27,

28]. Scoping reviews differ from narrative reviews and systematic reviews because they aim to determine the coverage of a body of evidence on a given topic rather than to synthesize the literature in a systematic approach [

29]. Identifying and mapping the available evidence is the focus of scoping studies [

30].

The authors adopted a scoping review approach because we wanted to map the landscape of different stakeholders’ values and interactions among them in the process of integrating culture into rural tourism development. Additionally, a scoping review approach also allowed us to interpret the literature analytically [

29]. Thus, a scoping review was undertaken based on the framework of Arksey and O’Malley [

31] to understand how and why cultures are integrated into rural tourism. The following sections outline the five steps of our scoping review.

Step 1: Identifying the Research Question

This step requires identifying a guiding research question based on the research goals. The research question needs to include three elements: population, intervention, and outcomes [

31]. Our research question was “What is known from the existing literature about the aims and motives (outcome) of integrating cultures (intervention) into rural tourism (population)?”

Step 2: Identifying Relevant Studies

A search string was made using Boolean operators (including OR, AND, NOT, quotation marks, wildcards, and brackets): ("rural tour*" OR "rustic* tour*" OR "countryside tour*" OR "exurban tour*" OR "out-country tour*" OR "undeveloped tour*" OR "arcadian tour*" OR "out-of-town tour*") AND ("cultur* attraction*" OR "minorit* cultur*" OR "ethnic cultur*" OR "indigenous cultur*" OR "aboriginal cultur*" OR "local cultur*" OR heritage OR "tradition* cultur*" OR festival* OR “cultur* activit*” OR “cultur* event*”) AND (plan OR aim* OR animus OR intent* OR purpos* OR thinking OR object* OR occasion* OR cause* OR reason* OR rational* OR why OR incentiv* OR motiv* OR impetu* OR stimul* OR encourage* OR induce*). The search string was applied to the Web of Science (WoS) Core Collection (1900–present) on 8th March 2022.

Step 3: Study Selection and Charting the Data

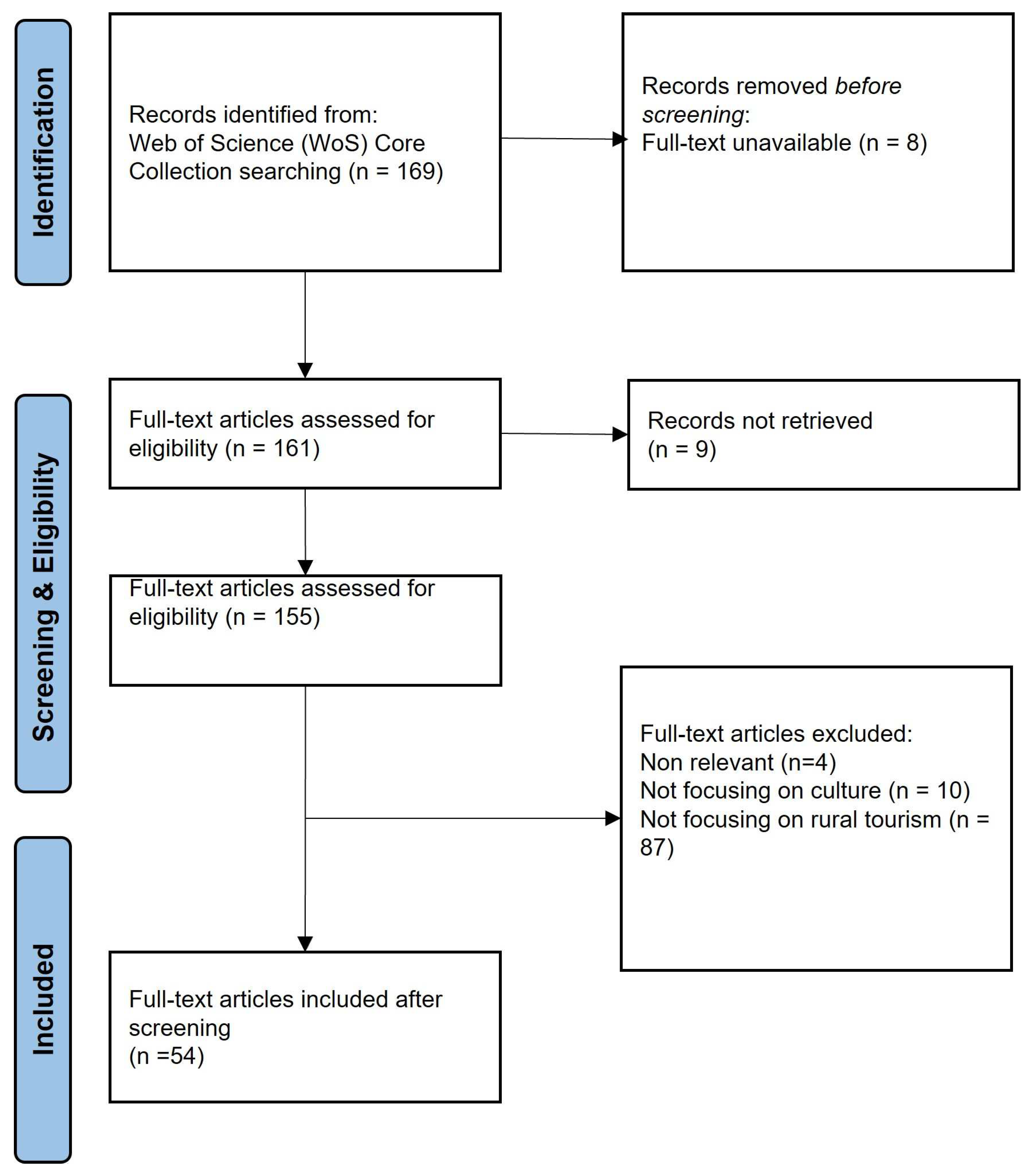

After the searched records (n = 169) were exported from the WoS Core Collection, they were screened following the procedures in

Figure 1. Only peer-reviewed journal articles were included. The exclusion criteria specified articles including both culture and rural tourism. The searched records were first read and assessed by every author independently. All authors then gathered and discussed the assessment results. Articles were included only when agreements were reached among all authors.

Step 4: Collating, Summarizing, and Reporting the Results

Eighty-seven articles were included in this study after screening. The screening outcomes are presented in

Supplementary Document 1. All articles were then categorized based on a narrative or thematic approach, proposed by Arksey and O’Malley [

31], to present a narrative account of the existing research. This is because scoping studies tend to summarize and present themes and findings evenly, including theoretical or conceptual positions adopted by authors [

29]. This approach fits our purpose of identifying the holistic landscape of culture-integrated rural tourism by considering the different geographical locations, participating stakeholders, and integration forms.

3. Results

3.1. Roles of Cultural Integration to Sustain Rural Tourism

Although rural areas provide abundant natural attractions, including landscapes, fresh air, natural views, plants, and wildlife, cultural elements can bring additional opportunities for tourism development and preserve unique connections between tourists and destinations [

32].

Culture is defined by the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) as “the set of distinctive spiritual, material, intellectual and emotional features of society or a social group, and that it encompasses, in addition to art and literature, lifestyles, ways of living together, value systems, traditions and beliefs” [

33]. Thus, cultural integration can offer new experiences of tourism since cultural tourism contributes to the conservation of cultural assets [

34]. Local cultures and heritage can be better preserved to build sustainability in rural tourism, relying less on the exploitation of resources, such as deforestation, commercial farming, and destructive recreational activities [

13]. For example, cultural tourism has induced a new trend for accommodation in the traditional countryside. The Hobbit House, Bag End, the Mill, the Party Book, the Green Dragon Inn, and other settings from The Lord of the Rings and The Hobbit fantasy movies attract millions of tourists with the unique culture of Hobbiton [

35].

In addition, culture-integrated rural tourism opens a window for cross-culture communication and the invention of new cultures, such as a new school of arts. Tourism activities with a mixture of local resources and culture are unique attractions to tourists, and they can also be regarded as part of a larger process of the rediscovery of traditional local architecture and functional components of rural space [

36]. For example, the Cologne Art Fair in 2022, is an eye-catching mix of old and new, modern and traditional, antique curios and modern sculpture, mahogany collections and modern brand designs, attracting people who are interested in arts to visit Germany as tourists [

37]. Not only can this kind of tourism strengthen the communication and connection of tourists and destination and of memory and culture, but it also creates a bridge between ancient and modern society, leading to innovative achievements.

However, cultural integration will also commodify local cultures and diminish the local identity of communities with the development of tourism consumption [

11]. Capital-intensive development will raise the social cost, with local communities largely excluded from the decision-making. For example, to attract more tourists, the local villagers living in the Yellow Silk Village in Ala Town, Fenghuang County, were forced to relocate from their original villages to a new place for the development of the historical rampart built in 687 A.D. during the Tang Dynasty as a new tourism attraction [

38]. In the following sections, we present why culture has been integrated into rural tourism by different countries, the views of different stakeholders during the integration process, and how culture has been integrated.

3.2. Lessons from Different Geographical Locations

We categorized the literature into different countries and explored why cultures have been integrated into rural tourism. The full results are presented in

Table A1 in the Supplementary Materials.

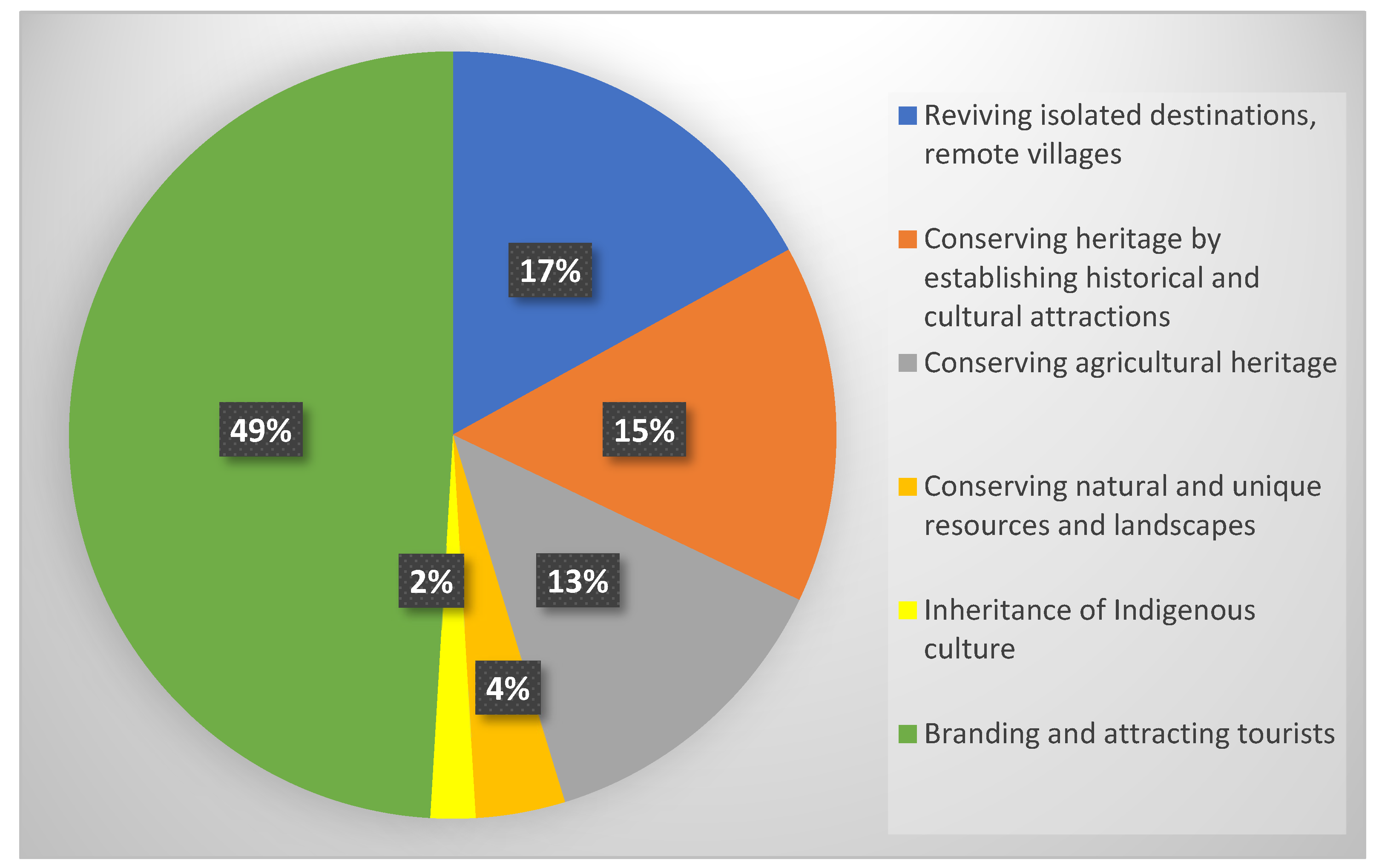

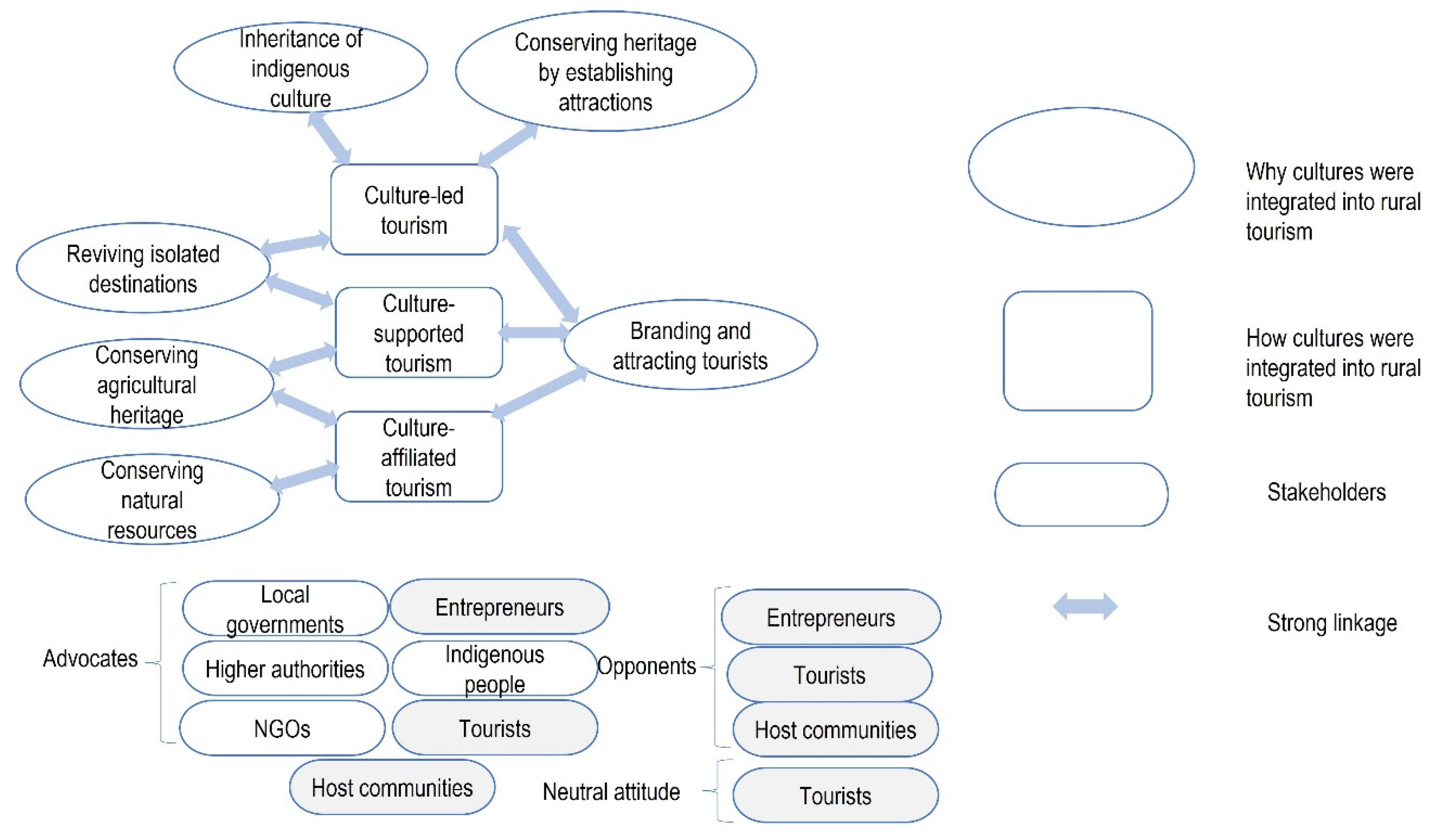

Figure 2, below, summarize a narrative account of six themes: (1) reviving isolated destinations and remote villages; (2) conserving heritage by establishing historical and cultural attractions; (3) conserving agricultural heritage; (4) conserving natural resources and landscape; (5) inheritance of Indigenous culture; and (6) branding and attracting tourists.

The first theme describes the remote and isolated regions with heritage that have utilized their local cultures to attract tourists and ultimately revive the local economy. For example, the local wisdom regarding musical instruments and managing the physical and spiritual environment of the people living in Tugu Utara Village has been translated into tourist attractions, facilitating the tourism development of West Java [

39]. Tourists are fascinated with the unique local characteristics and philosophical values, including proverbs, handicrafts, architecture, culinary, kesenia reog, lute fultue, and traditional keris weapons [

39]. Tourists are willing to spend long periods of time at different destinations and experience diverse cultural activities. The revenue and employment opportunities brought about by tourists have improved the local economy and increased the popularity of the local culture.

The second theme describes the tourism managers who have adopted culture as an approach to attracting tourists and branding. Such integration attracts global tourists by providing local food, special festivals, and other cultural resources. For example, local food and related festivals could attract tourists with a preference for food to stay at the destination to taste different local foods and celebrate festivals with the locals. Cultural integration can also increase the lengths of stay of tourists at destinations [

40]. Moreover, having culturally diverse activities is an opportunity to increase touristic experiences, meeting the tourists’ demands for rich experiences while traveling [

40].

Conserving heritage by establishing historical and cultural attractions is the third theme identified from the literature. This approach aims to use tourism to attract resources and attention to conserve the local heritage. For example, mural-based tourism, filled with ancient stories and elements, is a specific strategy that has been used to conserve the historical and cultural heritage of Saskatchewan communities [

41].

Conserving agricultural heritage by providing manifold agricultural activities to tourists is the fourth motive for integrating cultures into rural tourism. Agricultural traditions are important parts of the way of life and culture of local people living in rural areas. Conserving agricultural heritage can provide new tourism activities, such as fishing, fruit picking, and food making, helping to sustain local people’s traditional way of living [

42]. For example, many family farmers around the world have transformed their farms into agritourism destinations by providing fruit-picking activities [

43,

44,

45]. This business model helps to conserve agricultural heritage and brings opportunities for little-known agricultural destinations and resources [

43].

The fifth theme describes the motive for culture-integrated rural tourism to conserve natural and unique landscapes. Local cultures, such as the sounds of waterwheels and Indigenous rock arrangements, can be integrated into natural landscapes to create unique cultural scapes, such as soundscapes, to offer fresh experiences to tourists [

46,

47]. This approach offers additional value to existing landscapes and provides more incentives to conserve the landscapes. For example, a specific garden in Brazil was designed by famous designers and collectors who utilized the local topography and collected local plants that were transplanted into the new rural garden. Such a method can help conserve unique natural resources because of the care provided by the garden’s managers since they have a responsibility to guarantee a sufficient flow of tourists to the garden [

48].

The last theme introduces the motive for rural tourism of inheriting Indigenous culture. For example, Uygur has its own minority culture, including art, music, festivals, food, and costumes [

49]. However, these have been neglected by tourism managers in the past, which hampers the inheritance of minority cultures. Nowadays, tourism in Uygur pays attention to such integration [

49]. Uygur performers, who wear traditional Uygur costumes—the chapan (jacket), koynek (shirt), and doppa (skullcap)—perform songs (naksha) and a series of energetic traditional dances accompanied by Uygur instrumentalists for tourists [

49]. This prevents the loss of this valuable culture, such as has occurred at other common tourism destinations.

3.3. Stakeholder Analysis

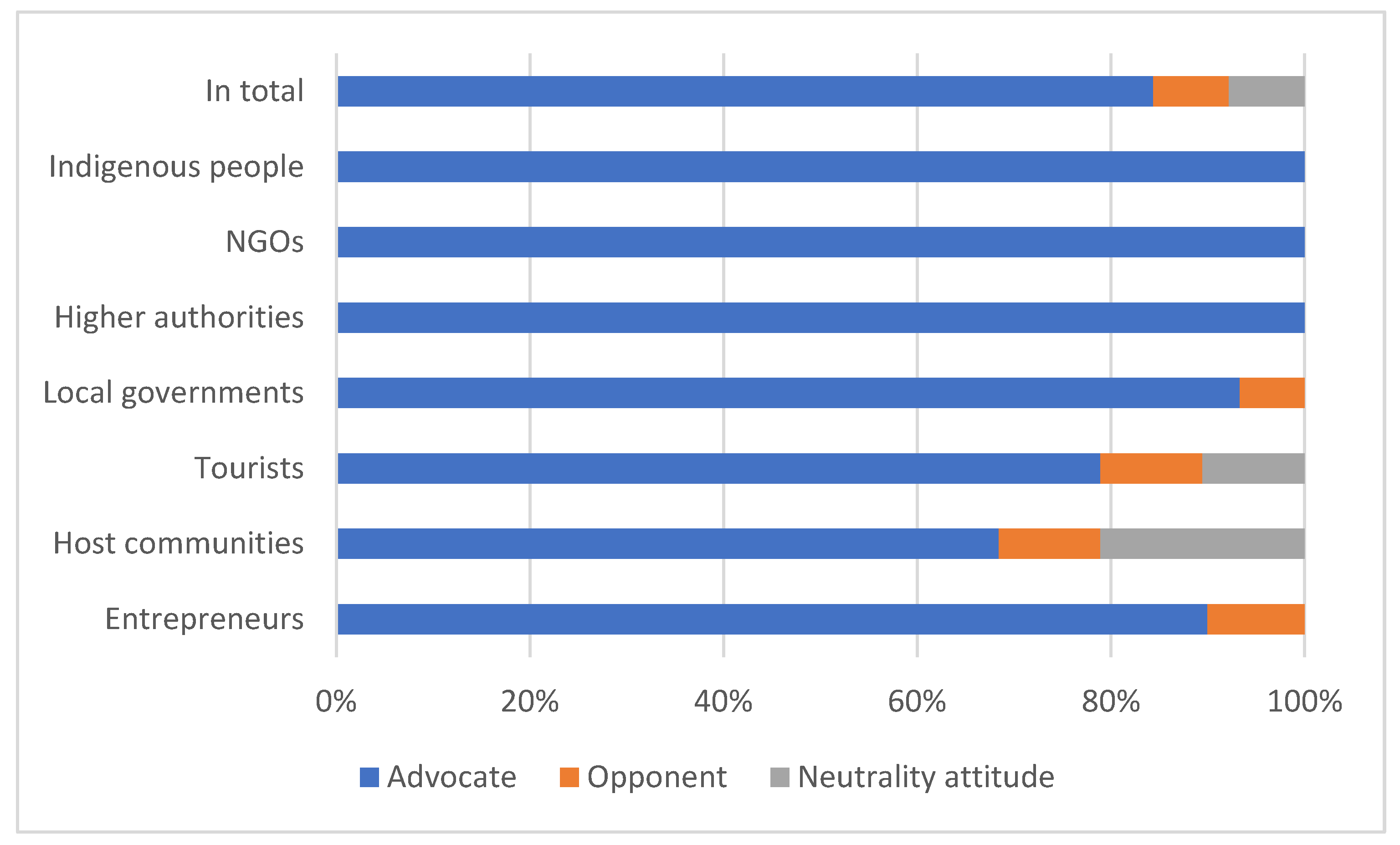

Advocates, opponents, and people preserving an attitude of neutrality represent three different views among stakeholders on integrating culture into rural tourism. As shown in

Figure 3 below, more than 84% of the identified stakeholders in the literature are advocates. Opponents and people with a neutral attitude only comprise around 8% each. Advocates are found in all stakeholder groups in literature. Many higher authorities, NGOs, and Indigenous people are advocates because, as stated in the literature, they believe cultural integration can promote tourism, conserve the environment, and preserve local heritage (

Table A2 in the Supplementary Materials).

When it comes to the expectations of these stakeholders, tourism providers, such as entrepreneurs, need business opportunities for inbound tourism, and larger operating spaces are important for marketing reciprocal tourism. Tourism managers, such as the local government, need to promote and manage local resources and services. Tourism demanders, i.e., tourists, look forward to new activities they cannot experience in cities, such as unique soundscapes, a clean environment, beautiful scenery, and cultural festivals.

To uncover the complex process of cultural integration, opponents and their views need to be understood and highlighted. Opponents are found in stakeholder groups of entrepreneurs, host communities, tourists, and local governments (

Figure 3). Some entrepreneurs are concerned that cultural integration requires large new investments but results in little profit. New local businesses are also concerned about the competitive local real estate market. For example, the popularity of hotels was promoted by the revitalization of a peripherical village in Mértola, which has led to an increase in the number of chain hotels, reducing the profits entrepreneurs make [

50]. In addition, entrepreneurs may be concerned about the trend of agritourism transforming standard farms, for example, whether tourists will be attracted to Nova Scotia to pick fruits [

36].

Similarly, some tourists also worry about the increasing costs in rural destinations after cultural integration. For example, some culture-integrated trips will add additional costs for the tourists and may make them less interested. Ecological environments, rather than cultural products or heritage, are more popular with tourists when visitor traffic increases and costs rise [

51]. In addition, tourists may not be interested in some of the cultural integration activities; for example, some people prefer to visit the natural landscape of Chengdu Plain rather than enjoy the local food, so they are unwilling to pay for the latter [

51].

Local governments may also be concerned about whether large-scale cultural integration projects will become a new financial burden. Cultural integration often requires investments in improving the landscape and heritage elements. For example, the Chengdu Municipal Government in China expressed concerns about more funds and efforts to refurbish the original site. It is uncertain if tourism revenue can offset the financial cost [

51]. Higher authorities are aware of non-consensus emerging and growing among different stakeholders during cultural integration [

15]. Moreover, host communities may not be satisfied with the cultural integration process and outcomes [

52]. Host communities are uncertain about the benefits and costs brought about by cultural integration, such as environmental impacts [

15]. They are also concerned about the cumulative impacts of the quick influx of capital, such as their voices disappearing in the decision-making process [

53].

3.4. Integration Levels of Cultural Considerations in Rural Tourism

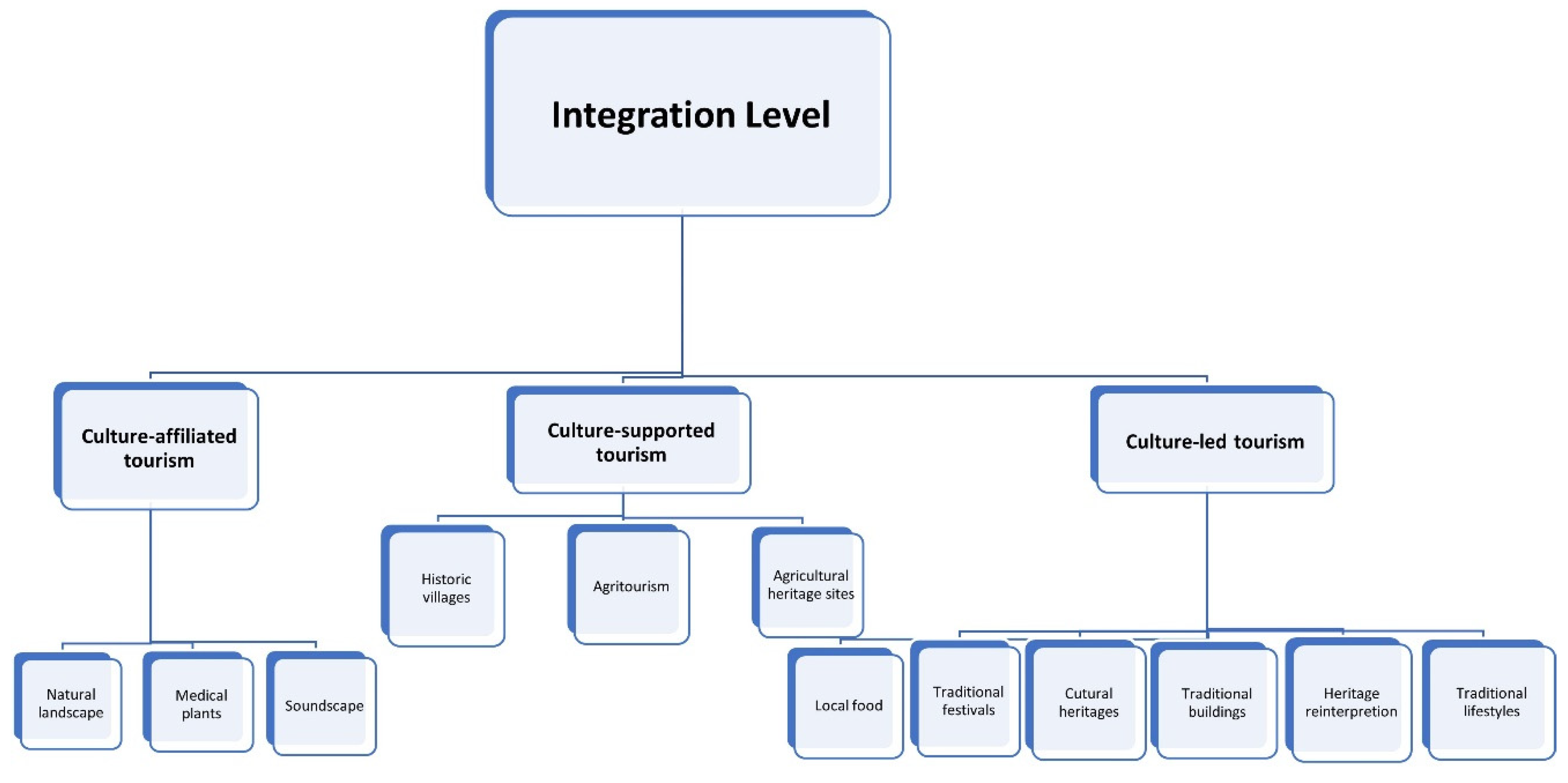

Cultures have been widely and increasingly integrated into rural tourism, but how cultures are integrated remains a complicated issue. Based on the included 54 studies, we identified three different levels of integration (

Figure 4), which are culture-affiliated tourism, culture-supported tourism, and culture-led tourism (

Table A3 in the Supplementary Materials).

Culture-affiliated tourism describes rural tourism led by unique sightseeing that does not have a direct relationship with the local culture. The main attractions for tourists are the natural components, including the natural resources, natural aesthetic, and soundscape. Culture plays an accessory role in attracting tourists, such as higher ratings [

54] and ecotourism trips [

55]. For example, Shenquan Ecotourism Scenic Spot, located in Toketo County, Hohhot city, Inner Mongolia, attracts tourists with its earned national AAAA certificate [

56]. The biggest highlight of the scenic area is the unique wetland–grassland around the Yellow River in the Kubuqi Desert, but it also has the sacred springs and Yunzhong ancient county cultural and historical tourism resources, which are based on the special topography [

56].

Culture-supported tourism normally includes a significant cultural part, such as Indigenous herbal knowledge [

2]. However, it also closely relies on natural resources or landscapes, such as the Tiger Leaping Gorge along the Jinsha River, China [

57].

Stonehenge is a famous cultural temple site of prehistoric times in Europe, which was built with the method of “soil collection” [

58]. Although there are many historic stories of the establishment of Stonehenge, it is primarily famous for its location and the natural scenery: on the summer solstice each year, two stones line up with the sun rising on the other side of the horizon [

58]. Farm tourism also plays an important role in culture-supported tourism. Tourists can escape from the urban environment and get more in touch with nature by following farming traditions, such as fruit picking [

59]. For example, more than 80% of the accommodations in the rural areas of East Germany are provided by farms [

60].

Culture-led tourism represents rural tourism led by local cultures and heritage, including Indigenous knowledge, arts, cultural souvenirs, food, historical landscapes, and cultural landmarks. The main attractions for tourists are the diversity and differences in cultures. Indigenous knowledge and the wisdom of herbs, water, land, animals, and seasons offer new experiences for tourists to understand the world and communicate with nature [

61,

62,

63]. For example, Indigenous knowledge of the underwater environment could contribute to the development of diving tourism in Indonesia [

64]. Local food is also a major attraction for tourists in this sort of tourism. For example, around 57% tourists surveyed in the Norwegian region said that local food is significant for their trips to visit rural destinations [

65].

4. Discussion

As shown in the previous section, cultural integration is not a panacea to solve all of the development problems of rural areas. It involves a complicated integration process involving different stakeholders. Win-win solutions are not always possible. To further highlight the significance of why and how culture is integrated into rural tourism, we synthesized the results in

Section 3.1,

Section 3.2,

Section 3.3, and

Section 3.4 in

Figure 5 below.

Branding and attracting tourists are closely related to many types of integration. Motivation and satisfaction are two notions broadly studied in tourism academia, and the core of these two concepts is the tourist [

66]. This is why the consensus objectives of most culture-integrating actions are to meet the different demands of tourists. Tourists are the main sources of all kinds of tourism; only when they come to these destinations can culture-integrated tourism have the expected effects. Therefore, collaborating to create a strong and positive perception of tourism destinations is fundamental to all culture-led, culture-supported, and culture-affiliated tourism. However, tourists are not a single group in which everyone has the same values, interests, and beliefs. As shown in

Figure 5, they can have rather different views on culture-integrating actions. For example, tourists who are not interested in the local food vacillate between advocates and opponents. An oversimplification of tourists and their participation in tourism as consumers is ill-directed and may overlook the complex interaction among different stakeholders, as shown in

Section 3.

The inheritance of Indigenous culture and conserving heritage by establishing attractions play significant roles in promoting culture-led tourism. Culture-led tourism attracts tourists mostly based on the cultural component. Indigenous culture and local heritage are diverse and able to offer a range of different experiences. For example, tourists flock to some famous historical sites, museums, and temples, such as the Angkor Wat, the Prambanan Temple, the Borobudur Temple, and Potala Palace, and are exposed to unique local cultural beliefs about history, offerings, and worship [

67,

68]. Symbolized cultural elements, such as Indigenous festivals, Indigenous music, Indigenous paintings, Indigenous artefact, cultural activities, and food, are also popular cultural elements that are integrated into rural tourism to attract specific groups of tourists who have a strong interest in different cultures [

39,

40]. Using local wisdom as a tourist attraction can promote sustainable tourism paradigms and extend the tourists’ stays [

39,

69].

Reviving isolated destinations is closely related to culture-supported and culture-led tourism and is based on the complementarity between natural resources and the cultural background. Isolated villages usually have affluent Indigenous cultures and untouched natural land, such as lakes and forests, which can appeal to many visitors [

1,

70]. Thus, reviving these destinations can increase their visibility and develop tourism through publicity. This is mainly achieved by providing local accommodations with cultural elements, including food or souvenirs. Additionally, agricultural tourism has become increasingly popular among tourists who enjoy agricultural activities, such as picking fruits [

42,

71]. Agricultural tourism is mainly led by local farms and it is an important approach for promoting culture-supported and culture-affiliated tourism to conserve agricultural heritage [

71]. Conserving natural resources is closely related to cultural-affiliated tourism whose cultural component is the least. For example, Lake Taupō in New Zealand, Pink Lake in Australia, and Black Sand Beach in Iceland are not only known for their beautiful natural landscapes but also for their appearances in famous books, movies, videos, and songs [

72,

73].

Win-win solutions are not always possible in cultural integration. Some poorly designed integrating operations, as shown, have destroyed cultural heritage, polluted native environments, and violated the human rights of local communities. Winners and losers are not always fixed and are largely dependent on the forms of integration and the expectations of different stakeholders. For example, entrepreneurs advocate for integrated projects mainly because of individual profits, which they can earn by integrating the local culture and investing in heritage projects such as historic buildings. However, they could also disagree with the refurbishment of historical structures if they cannot earn money. Businesspeople may not think cultural integration is always lucrative, and there may not be enough financial support from the government (

Figure 5). Conflicts of interest among different stakeholders are often hard to avoid. For example, conflicts between foreign tour operators and the Vietnamese Government suppressed the development of tourism [

74]. The Government was more concerned about the impacts of booming foreign capital and tourists on national security and state-owned tourism companies and restricted the licenses for activities and attractions. To meet tourist demand, foreign operators have had to rely on their personalized social networks to provide tourism offerings outside of the formal regulatory frameworks [

74].

5. Conclusions and Policy Implications

Rural tourism is one of the most significant approaches to sustaining rural areas. Most tourism is based on different cultures, so it is important to utilize the local culture to enrich tourism attractions, activities, and arts. While there have been many cases showing that culture benefits rural tourism, some destinations are not beneficiaries of culture-integrated tourism because it is ineffective, and some even are destroyed by such integration; for example, they lose their cultural identity, or there is a discrepancy between the supply and demand. As a result, we must better understand why and how to integrate culture into rural tourism.

To address this issue, we conducted a scoping review to answer the following questions: What is known from the existing literature about the aims and motives (outcome) of integrating cultures (intervention) into rural tourism (population)? We then divided this question into three components: different regional motivations, stakeholder attitudes, and different levels of integration. We found that different countries have different starting points, which is mainly because of their different cultural backgrounds and geographical environments. There are six motives: (1) reviving isolated destinations and remote villages; (2) conserving heritage by establishing historical and cultural attractions; (3) conserving agricultural heritage; (4) conserving natural resources and landscapes; (5) the inheritance of Indigenous culture; and (6) branding and attracting tourists. In addition, the stakeholders include tourism providers, managers, and consumers. They tend to maximize their own interests while considering others. Thus, their attitudes towards cultural tourism are also different from each other, and even the same stakeholder will change his/her attitude according to different interests. According to the degree to which culture and natural scenery are involved in tourism, we divided the degree of integration into three categories: culture-support, culture-affiliate, and culture-led tourism.

Multi-stakeholder and multi-perspective analysis is needed to map how and why cultures are integrated into rural tourism. While cultural integration is complicated, injustice and conservation effects do not have to be a consequence of integrating cultures into rural tourism. Multi-way communication among tourism providers, managers, and consumers can mitigate disruptive outcomes and unlock positive social outcomes. Tourism managers, especially higher authorities, should determine the administrative subject of tourism management, arrange clear management authority, and clarify the guiding and supervisory role of the government in tourism management. Local governments must understand the guidelines well and investigate the actual situation on the ground. The management and ownership of scenic spots should be clearly divided, which can promote the capital being invested into their proper management and development. Thus, problems such as source guarantees and insufficient funds can be solved. Tourism suppliers should limit passenger flow during peak tourism periods because the excess passenger flow will lead to the over-consumption and destruction of local resources. Specifically, taking the management of tourists seriously before they enter tourist destinations is an efficient prevention method. This approach includes regulating scenic spot season promotions, reasonable positioning of the target market, and making full use of price leverage. The use of the mass media to disseminate information and close cooperation with travel agencies and other tourism agencies are the perfect ways to develop local tourism. In addition, tourism development should follow a trustworthy and participatory approach that engages and empowers dispersed communities and displaced members to embrace, grow, and re-interpret their traditional cultures [

75]. Tourists should also honestly and respectably express their tourism experiences and proactively and constructively present their comments and suggestions to tourism suppliers and managers.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on

Preprints.org.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, H.X. and M.T.; methodology, H.X. and M.T.; software, H.X. and M.T.; validation, M.T. and H.X.; formal analysis, M.T. and H.X.; investigation, M.T. and H.X.; resources, M.T. and H.X.; data curation, M.T. and H.X.; writing—original draft preparation, M.T.; writing—review and editing, M.T. and H.X.; visualization, H.X. and M.T.; supervision, H.X.; project administration, H.X.; funding acquisition, H.X. and M.T. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Data Availability Statement

Some or all data, models, or code that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Xu, H.; Pittock, J.; Danniell, K. China: a new trajectory prioritizing rural rather than urban development? Land 2021, 10, 514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ysunza-Ogazon, A. From biological diversity to cultural diversity: A proposal for rural tourism in Mexico. WIT Transactions on Ecology and the Environment 2008, 115. [Google Scholar]

- Mioara, B.; Teodora, M.I. The Implication of International Cooperation in the Sustainable Valorisation of Rural Touristic Heritage. Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences 2015, 188, 222–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohe, Y. Community-based rural tourism in super-ageing Japan: challenges and evolution. Anais Brasileiros de Estudos Turísticos: ABET 2016, 6, 28–41. [Google Scholar]

- Rosalina, P.D.; Dupre, K.; Wang, Y. Rural tourism: A systematic literature review on definitions and challenges. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Management 2021, 47, 134–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, W.-T. Rural Tourism, in Tourism in Emerging Economies: The Way We Green, Sustainable, and Healthy, W.-T. Fang, Editor. Springer Singapore: Singapore. 2020; pp. 103–129.

- McAreavey, R.; McDonagh, J. Sustainable rural tourism: Lessons for rural development. Sociologia ruralis 2011, 51, 175–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bigaran, F.; Mazzola, A.; Stefani, A. Enhancing territorial capital for developing mountain areas: The example of Trentino and its use of medicinal and aromatic plants. Acta geographica Slovenica 2013, 53, 379–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabriel-Campos, E.; et al. Community eco-tourism in rural Peru: Resilience and adaptive capacities to the Covid-19 pandemic and climate change. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Management 2021, 48, 416–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saxena, G.; et al. Conceptualizing Integrated Rural Tourism. Tourism Geographies 2007, 9, 347–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mousavi, S.S.; et al. Defining cultural tourism. in International Conference on Civil, Architecture and Sustainable Development. 2016.

- Richards, G. Cultural tourism: A review of recent research and trends. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Management 2018, 36, 12–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacDonald, R.; Jolliffe, L. Cultural rural tourism: Evidence from Canada. Annals of Tourism Research 2003, 30, 307–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mwesiumo, D.; Halfdanarson, J.; Shlopak, M. Navigating the early stages of a large sustainability-oriented rural tourism development project: Lessons from Træna, Norway. Tourism Management 2022, 89, 104456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assumma, V.; Ventura, C.. Role of Cultural mapping within local development processes: a tool for the integrated enhancement of rural heritage. in Advanced Engineering Forum. 2014. Trans Tech Publ.

- Gravari-Barbas, M.; Bourdeau, L.; Robinson, M. World Heritage and tourism: from opposition to co-production, in World Heritage, Tourism and Identity. Routledge: London, UK. 2016; pp. 13-36.

- Madanaguli, A.; et al. The innovation ecosystem in rural tourism and hospitality – a systematic review of innovation in rural tourism. Journal of Knowledge Management 2022, 26, 1732–1762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khamdevi, M.; Bott, H. Rethinking tourism: Bali’s failure. IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science 2018, 126, 012171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rashid, W.; et al. Issues and Opportunities Associated with Trophy Hunting and Tourism in Khunjerab National Park, Northern Pakistan. Animals 2020, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W. Disruptive tourism development destroys ecology, Yunnan’s last pure land is doomed, in China Youth. 2005, China Youth Daily Beijing, China.

- Sorrell, E.; Plante, A.F. Dilemmas of Nature-Based Tourism in Iceland. Case Studies in the Environment 2021, 5, 964514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cawley, M.; Gillmor, D.A. Integrated rural tourism:: Concepts and Practice. Annals of Tourism Research 2008, 35, 316–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simpson, M.C. Community Benefit Tourism Initiatives—A conceptual oxymoron? Tourism Management 2008, 29, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zielinski, S.; et al. Factors that facilitate and inhibit community-based tourism initiatives in developing countries. Current Issues in Tourism 2020, 23, 723–739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marzo-Navarro, M.; Pedraja-Iglesias, M.; Vinzón, L. Key variables for developing integrated rural tourism. Tourism Geographies 2017, 19, 575–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blackstock, K. A critical look at community based tourism. Community Development Journal 2005, 40, 39–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colquhoun, H.L.; et al. Scoping reviews: time for clarity in definition, methods, and reporting. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology 2014, 67, 1291–1294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vogliano, C.; et al. Progress towards SDG 2: Zero hunger in melanesia – A state of data scoping review. Global Food Security 2021, 29, 100519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levac, D.; Colquhoun, H.; O’Brien, K.K. Scoping studies: advancing the methodology. Implementation Science 2010, 5, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Munn, Z.; et al. Systematic review or scoping review? Guidance for authors when choosing between a systematic or scoping review approach. Bmc Medical Research Methodology 2018, 18, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arksey, H.; O’Malley, L. Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. International journal of social research methodology 2005, 8, 19–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, T.H.; Hsieh, H.-P. Indicators of sustainable tourism: A case study from a Taiwan’s wetland. Ecological Indicators 2016, 67, 779–787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pessoa, J.; Deloumeaux, L.; Ellis, S. The 2009 UNESCO Framework for Cultural Statistics (FCS). 2009, Montreal, Quebec: UNESCO Institute for Statistics.

- Emekli, G.; Baykal, F. Opportunities of utilizing natural and cultural resources of Bornova (Izmir) through tourism. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences 2011, 19, 181–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peaslee, R.M. One ring, many circles: The Hobbiton tour experience and a spatial approach to media power. Tourist Studies 2011, 11, 37–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colton, J.W.; Bissix, G. Developing Agritourism in Nova Scotia: Issues and Challenges. Journal of Sustainable Agriculture 2005, 27, 91–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgner, C. The Art Fair as Network. The Journal of Arts Management, Law, and Society 2014, 44, 33–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, X. Who benefits?: tourism development in Fenghuang County, China. Human organization 2008, 67, 207–220. [Google Scholar]

- Nofiyanti, F.; et al. Local Wisdom for Sustainable Rural Tourism: The Case Study of North Tugu Village, West Java Indonesia. in E3S Web of Conferences. EDP Sciences. 2021. 2021.

- Zhang, T.; Chen, J.; Hu, B. Authenticity, Quality, and Loyalty: Local Food and Sustainable Tourism Experience. Sustainability 2019, 11, 3437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koster, R.L. Mural-based tourism as a strategy for rural community economic development, in Advances in culture, tourism and hospitality research, A.G. Woodside, Editor. Emerald Group Publishing Limited: Bingley, UK. 2008.

- Sun, Y.-h.; et al. Conserving agricultural heritage systems through tourism: Exploration of two mountainous communities in China. Journal of Mountain Science 2013, 10, 962–975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Broccardo, L.; Culasso, F.; Truant, E. Unlocking Value Creation Using an Agritourism Business Model. Sustainability 2017, 9, 1618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Che, D. Select Michigan: Local food production, food safety, culinary heritage, and branding in Michigan agritourism. Tourism Review International 2006, 9, 349–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, X.; et al. Factors Affecting the Income of Agritourism Operations: Evidence from an Eastern Chinese County. Sustainability 2022, 14, 8918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.; et al. Acoustic environment management in the countryside: A case study of tourist sentiment for rural soundscapes in China. Journal of Environmental Planning and Management 2021, 64, 2154–2171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norris, R.P.; et al. Wurdi Youang: an Australian Aboriginal stone arrangement with possible solar indications. Rock Art Research: The Journal of the Australian Rock Art Research Association (AURA) 2013, 30, 55–65. [Google Scholar]

- Petry, C. Rural origins in creations of resident landscapers. in XXIX International Horticultural Congress on Horticulture: Sustaining Lives, Livelihoods and Landscapes (IHC2014): V 1108. 2014.

- Keyim, P.; Yang, D.; Zhang, X. Study of Rural Tourism in Turpan, China. Chinese Geographical Science 2005, 15, 377–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Delgado, F.J.; Martínez-Puche, A.; Lois-González, R.C. Heritage, tourism and local development in peripheral rural spaces: mértola (baixo alentejo, portugal). Sustainability 2020, 12, 9157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cong, L.; et al. Understanding Tourists’ Willingness-to-Pay for Rural Landscape Improvement and Preference Heterogeneity. Sustainability 2019, 11, 7001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moutela, J.A.; Carreira, V.A.; Martínez-Roget, F. Authenticity in Portugal’s Interior Rural Areas, in Authenticity & Tourism, J.M. Rickly and E.S. Vidon, Editors. Emerald Publishing Limited. 2018.

- Kastenholz, E.; Eusébio, C.; Carneiro, M.J. Segmenting the rural tourist market by sustainable travel behaviour: Insights from village visitors in Portugal. Journal of Destination Marketing & Management 2018, 10, 132–142. [Google Scholar]

- Deng, J.; King, B.; Bauer, T. Evaluating natural attractions for tourism. Annals of Tourism Research 2002, 29, 422–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kimmel, J.R. Ecotourism as Environmental Learning. The Journal of Environmental Education 1999, 30, 40–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Zhou, Z. The details exploration of intangible cultural heritage from the perspective of cultural tourism industry: a case study of Hohhot City in China. Canadian Social Science 2016, 12, 30–36. [Google Scholar]

- Hayes, J.P. The Recent Environmental History of Tiger Leaping Gorge: environmental degradation and local land development in northern Yunnan. Journal of Contemporary China 2007, 16, 499–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mason, P.; Kuo, I.L. Visitor Attitudes to Stonehenge: International Icon or National Disgrace? Journal of Heritage Tourism 2008, 2, 168–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Roget, F.M.J.A.A.U.R.X.A.T.I. Length of Stay and Sustainability: Evidence from the Schist Villages Network (SVN) in Portugal. Sustainability 2020, 12, 4025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caust, J.; Vecco, M. Is UNESCO World Heritage recognition a blessing or burden? Evidence from developing Asian countries. Journal of Cultural Heritage 2017, 27, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wheeler, J.V. Climate Change, Watershed Management, and Resiliency to Flooding: A Case Study of Papeno’o Valley, Tahiti Nui (French Polynesia). University of Hawai’i at Manoa: Ann Arbor. 2018; p. 112.

- Cajete, G. Look to the mountain: Reflections on Indigenous ecology, in Applied Ethics. Routledge: New York, US. 2017; pp. 557-564.

- McGinnis, G.; Harvey, M.; Young, T. Indigenous Knowledge Sharing in Northern Australia: Engaging Digital Technology for Cultural Interpretation. Tourism Planning & Development 2020, 17, 96–125. [Google Scholar]

- Prasetyo, N.; Filep, S.; Carr, A. Towards culturally sustainable scuba diving tourism: an integration of Indigenous knowledge. Tourism Recreation Research 2021, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frisvoll, S.; Forbord, M.; Blekesaune, A. An Empirical Investigation of Tourists’ Consumption of Local Food in Rural Tourism. Scandinavian Journal of Hospitality and Tourism 2016, 16, 76–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devesa, M.; Laguna, M.; Palacios, A. The role of motivation in visitor satisfaction: Empirical evidence in rural tourism. Tourism Management 2010, 31, 547–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richards, G. Cultural tourism: Global and local perspectives. New York, US: Psychology Press. 2007.

- Emekli, G.; Baykal, F. Opportunities of utilizing natural and cultural resources of Bornova (Izmir) through tourism. Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences 2011, 19, 181–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Roget, F.; Moutela, J.A.; Rodríguez, X.A. Length of Stay and Sustainability: Evidence from the Schist Villages Network (SVN) in Portugal. Sustainability 2020, 12, 4025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fonseca, F.P.; Ramos, R.A.R. Heritage Tourism in Peripheral Areas: Development Strategies and Constraints. Tourism Geographies 2012, 14, 467–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ćurčić, N.; et al. The Role of Rural Tourism in Strengthening the Sustainability of Rural Areas: The Case of Zlakusa Village. Sustainability 2021, 13, 6747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birns, N. Introduction to John Kinsella’s PINK LAKE. Thesis Eleven 2019, 155, 3–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mills, M. Pou Rewa: The Liquid Post, Maori Go Digital? Third Text 2009, 23, 241–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lloyd, K. Tourism and transitional geographies: Mismatched expectations of tourism investment in Vietnam*. Asia Pacific Viewpoint 2004, 45, 197–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rankin, P.; Hansteen-Izora, R.; Packer, L. Living Cultural Storybases: Selfempowering narratives for minority cultures. Aen journal 2007, 2. [Google Scholar]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).