Submitted:

25 December 2022

Posted:

05 January 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Eligibility

2.2. Patients

2.3. MR Imaging

2.4. BD score analysis

2.5. CT Imaging

2.6. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

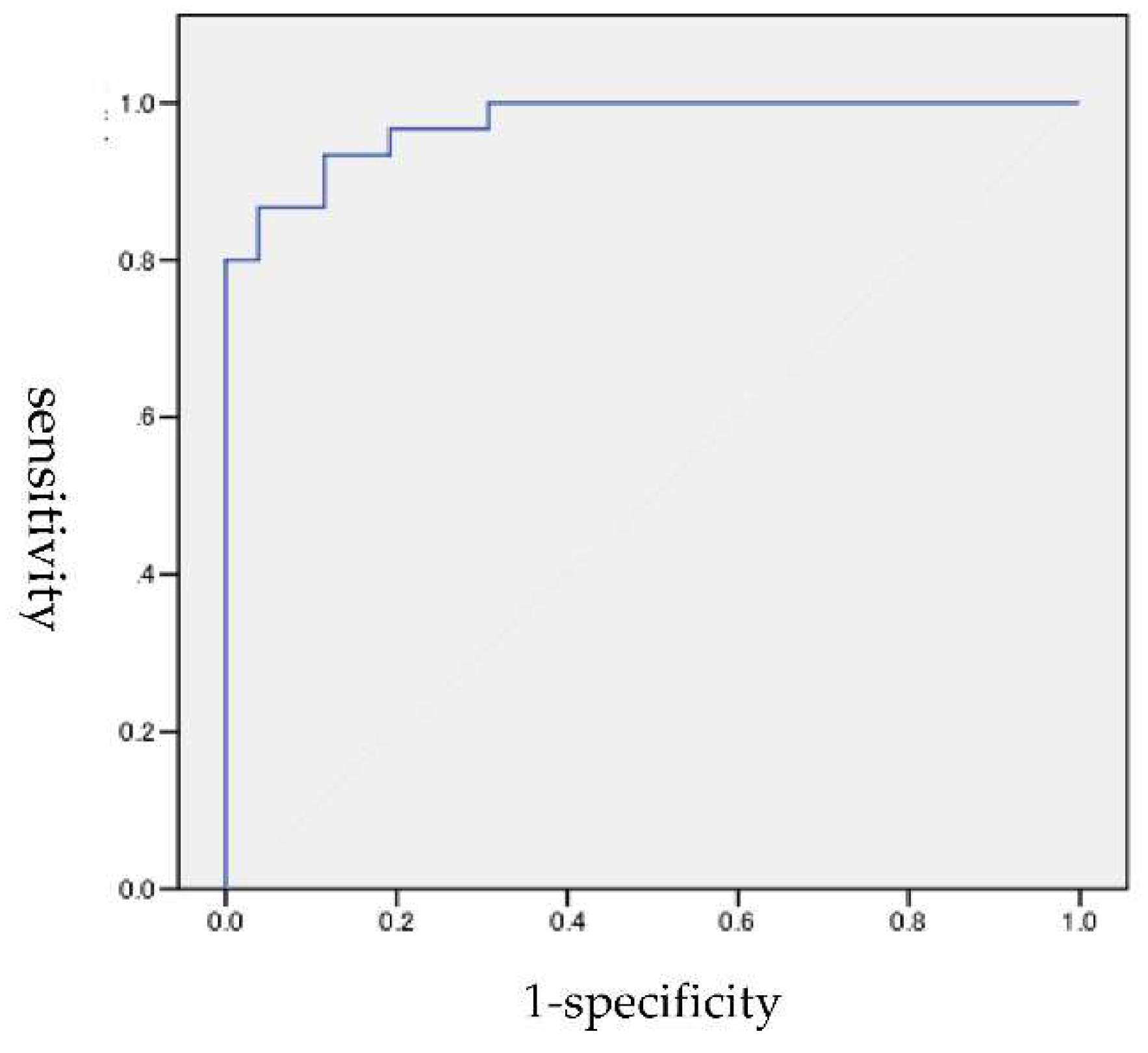

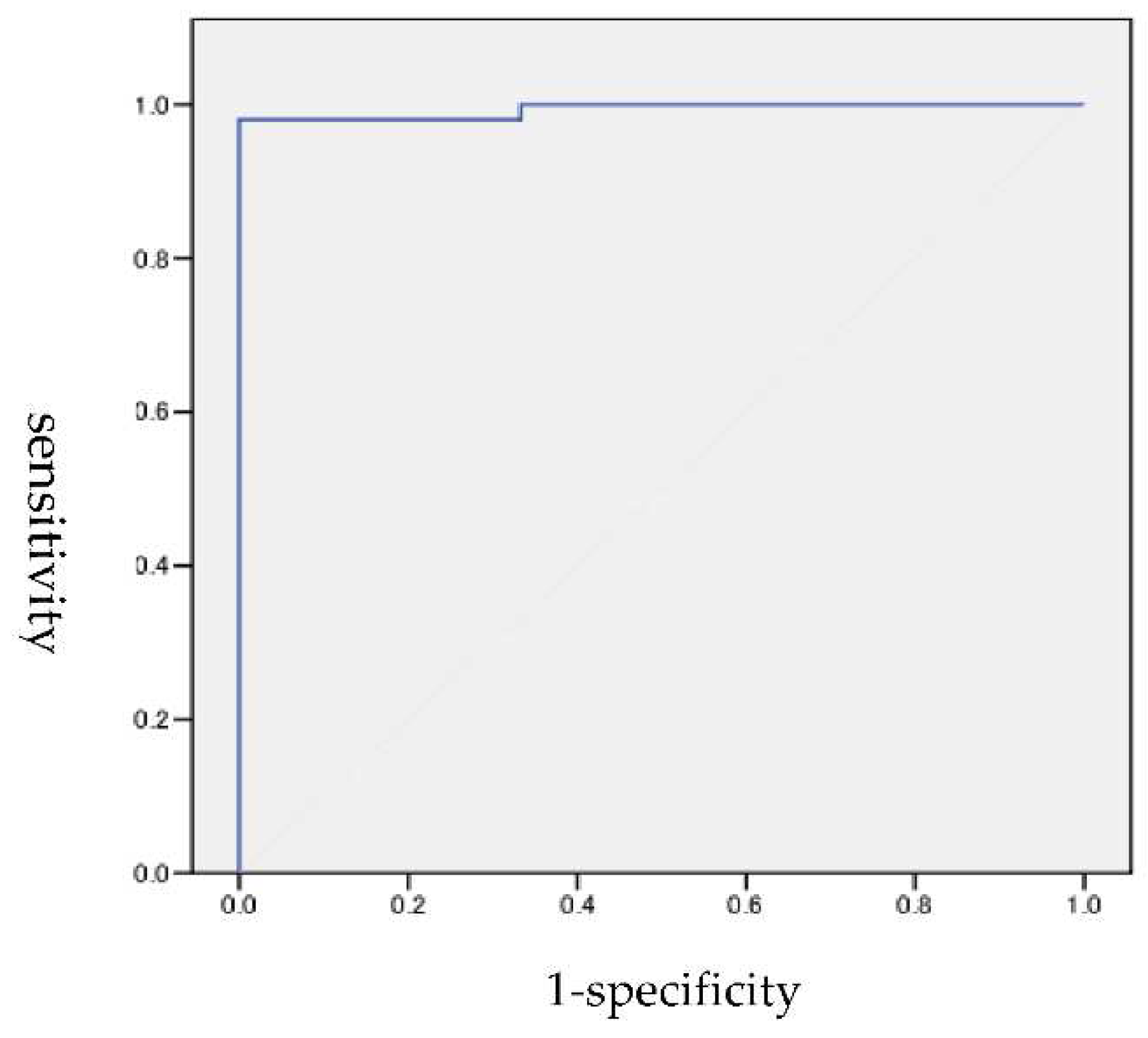

3.1. ROC analysis

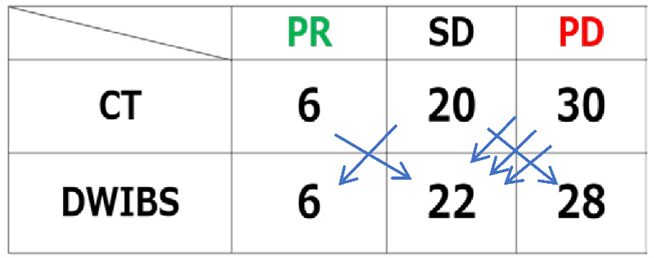

3.2. Treatment effectiveness determination by CT based on RECIST and DWIBS by BD score

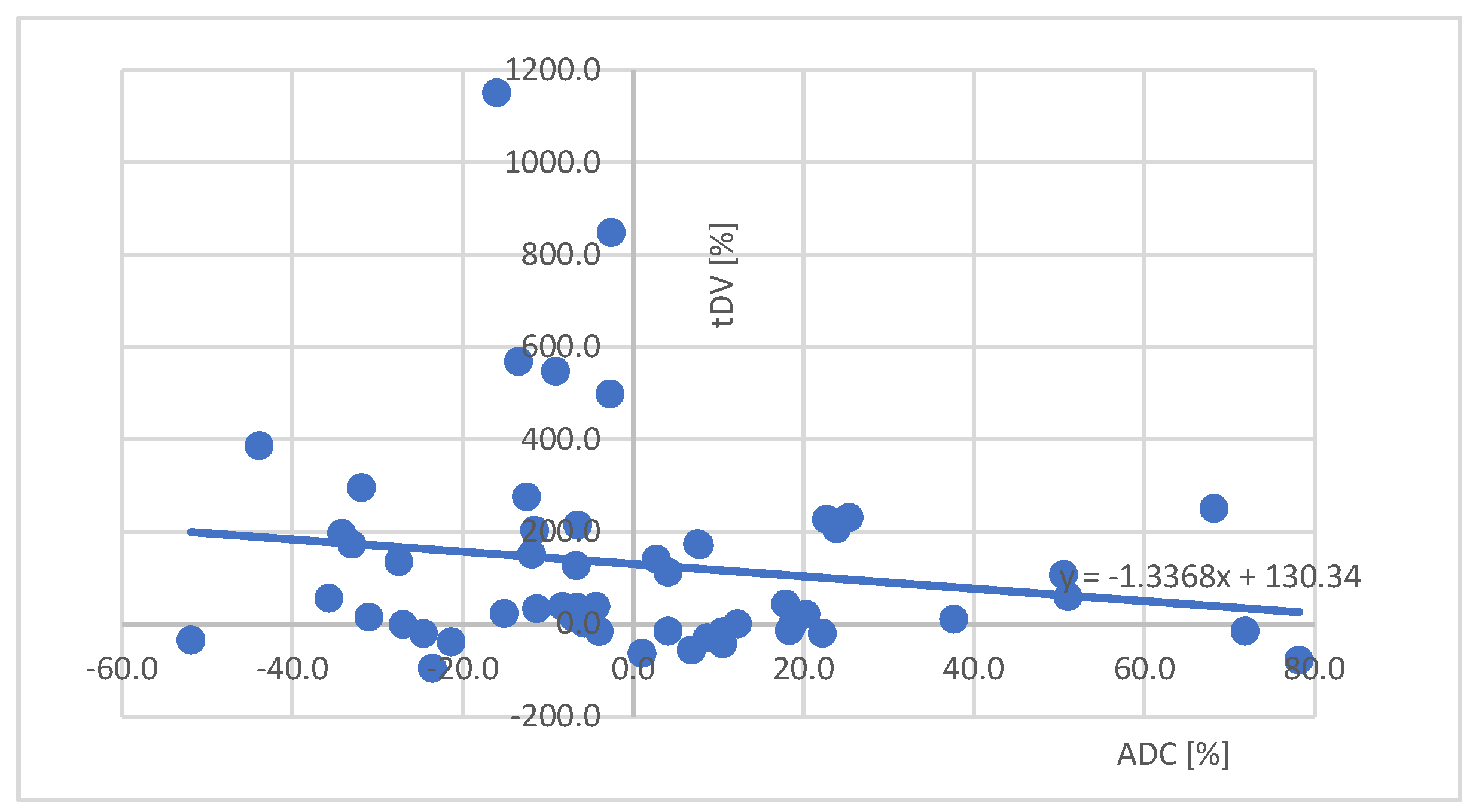

3.3. Approximate curve

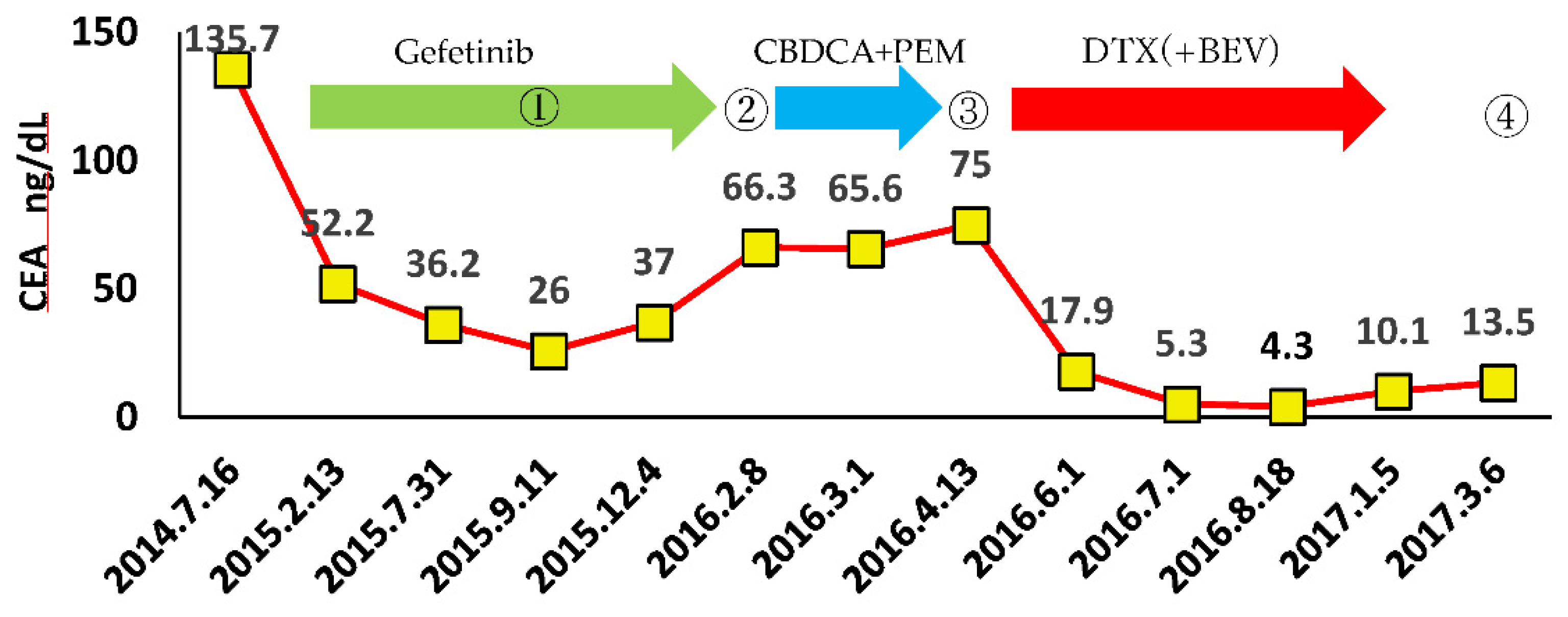

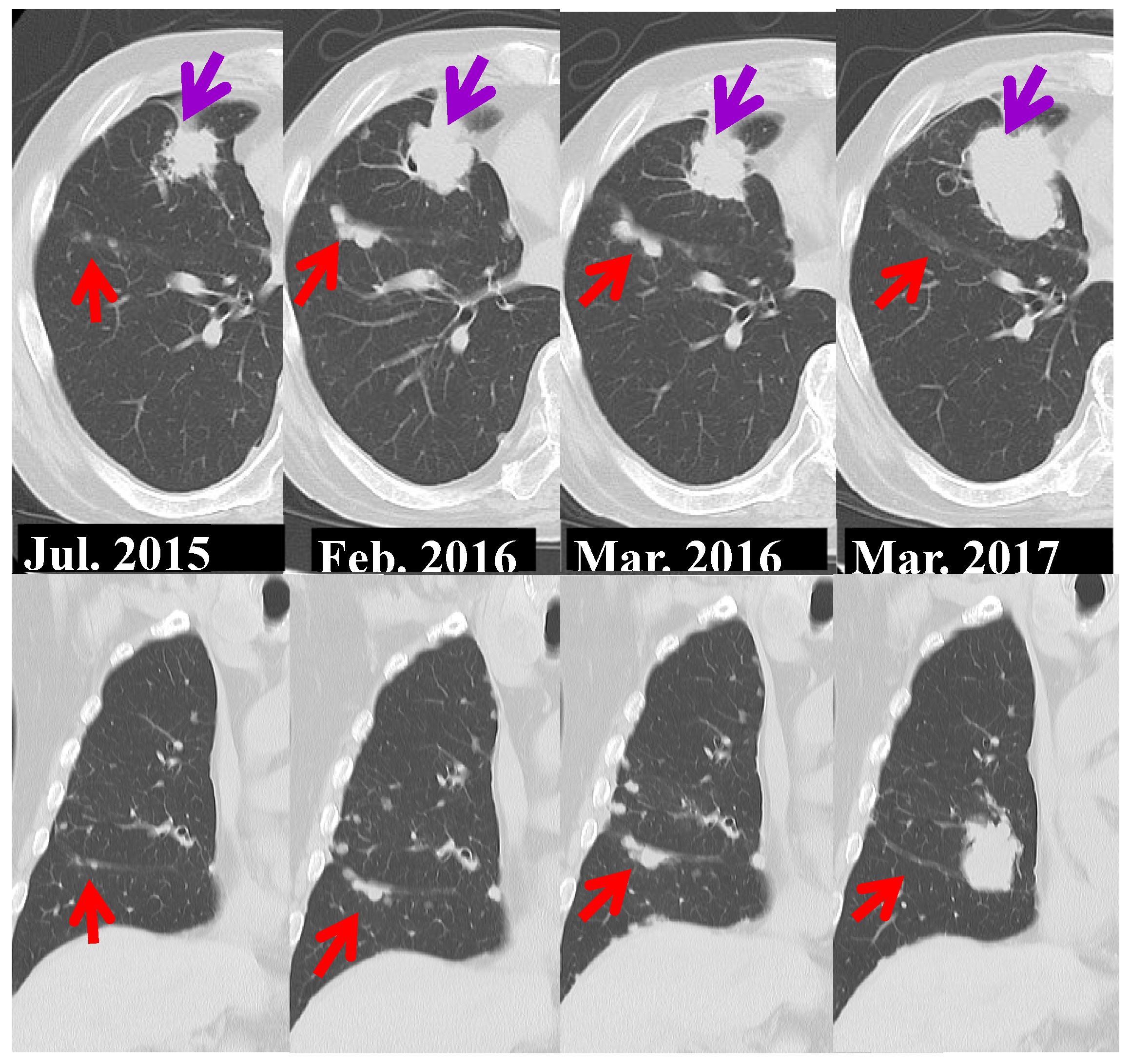

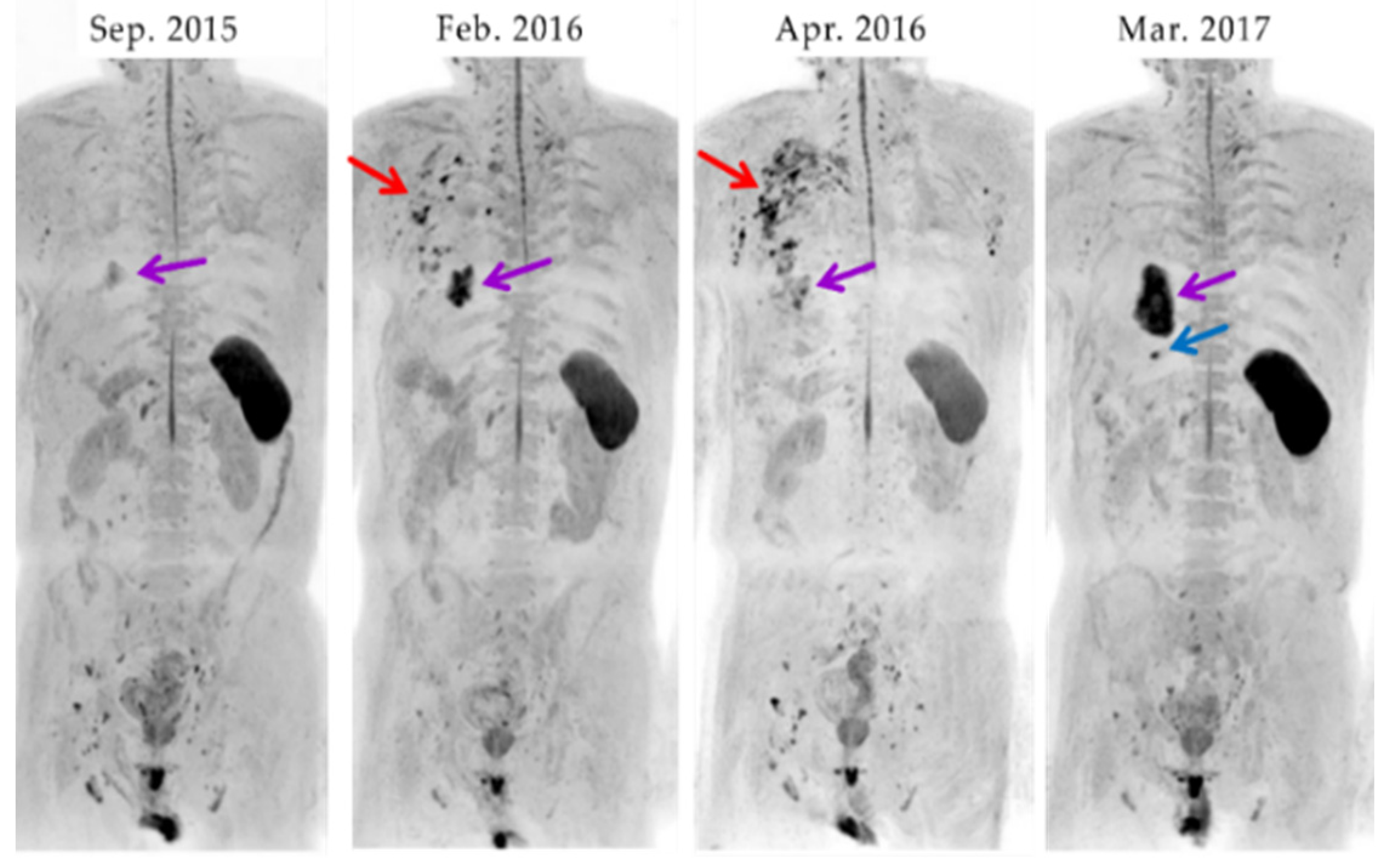

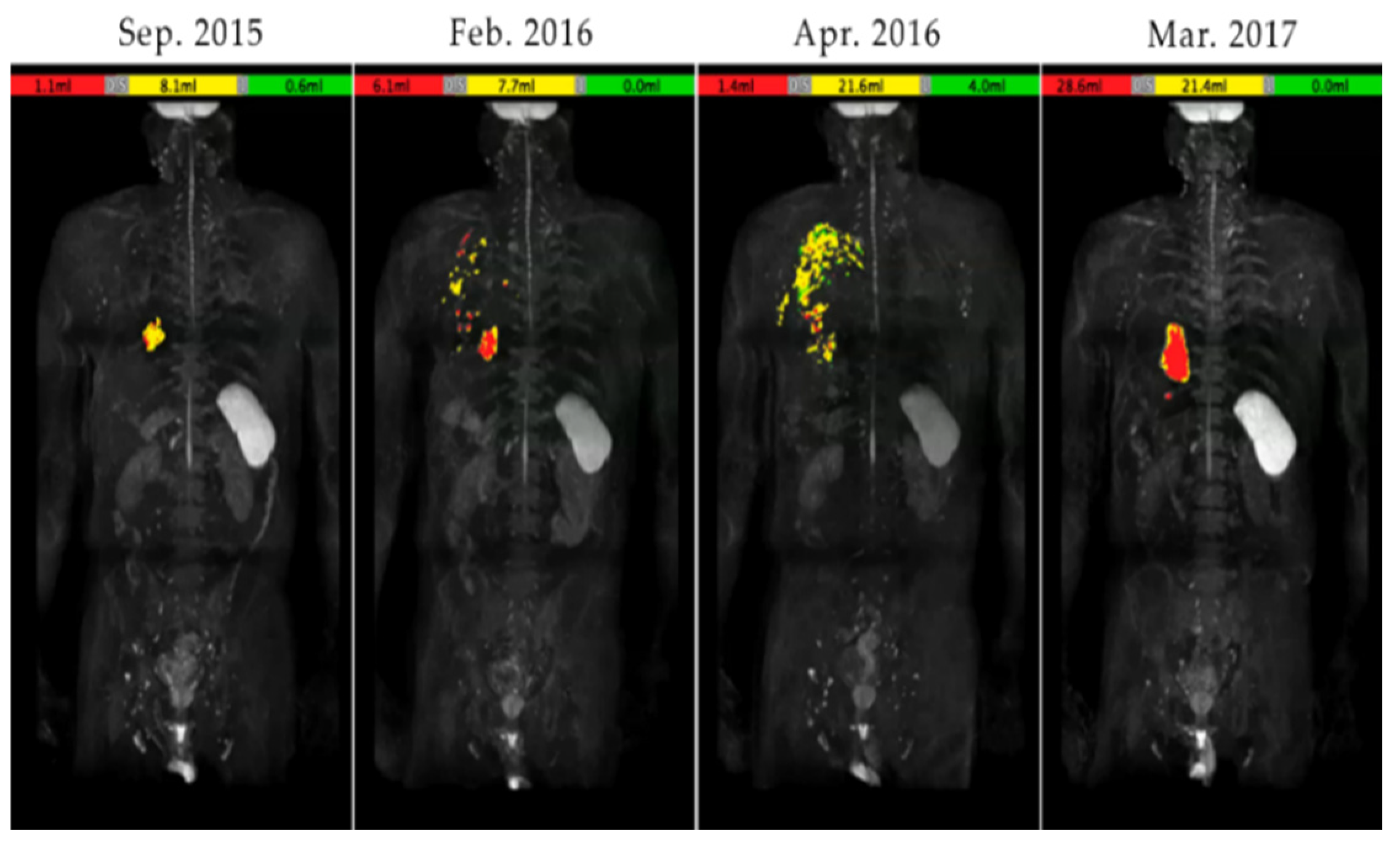

3.4. A case of suspected pseudoprogression in the present study

- through ④ indicate when DWIBS was performed.

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Henler T, Goldstraw P, Wenz F, et.al: Perspectives of novel imaging techniques for staging, therapy response assessment, and monitoring of surveillance in lung cancer summary of the Dresden 2013 Post WCLC-IASLC State-of-the-Art Imaging Workshop. J Thorac Oncol 2015, 10, 237-249. [CrossRef]

- Nishino M, Cardarella S, Dahlberg SE, et al: Radiographic assessment and therapeutic decisions at RECIST progression in EGFR-mutant NSCLC treated with EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitors. Lung Cancer 2013, 79, 283-288. [CrossRef]

- Chikara A; Diffusion weighted MRI. shujunsya, 2006, 166-169.

- Nishino M, Hatabu H, Johnson BE, et al: State of the art: response assessment in lung cancer in the era of genomic medicine. Radiology 2014, 271: 6-27. [CrossRef]

- Eisenhauer, E.A.; Therasse, P.; Bogaerts, J.; Schwartz, L.H.; Sargent, D.; Ford, R.; Dancey, J.; Arbuck, S.; Gwyther, S.; Mooney, M.; et al. New response evaluation criteria in solid tumours: Revised RECIST guideline (version 1.1). Eur. J. Cancer 2009, 45, 228–247. [CrossRef]

- Eisenhauer, E.A.; Therasse, P.; Bogaerts, J.; Schwartz, L.H.; Sargent, D.; Ford, R.; Dancey, J.; Arbuck, S.; Gwyther, S.; Mooney, M.; et al. New response evaluation criteria in solid tumours: Revised RECIST guideline (version 1.1). Eur. J. Cancer 2009, 45, 228–247. [CrossRef]

- RL Wahl, H Jacene, Y Kasamon, MA Lodge From RECIST to PERCIST: Evolving Considerations for PET response criteria in solid tumors. J Nucl Med, 50 (Suppl. 1) (2009), pp. 122S-150S. [CrossRef]

- Oxnard, G.R.; Zhao, B.; Sima, C.S.; Ginsberg, M.S.; James, L.P.; Lefkowitz, R.A.; Guo, P.; Kris, M.G.; Schwartz, L.H.; Riely, G.J. Variability of Lung Tumor Measurements on Repeat Computed Tomography Scans Taken Within 15 Minutes. J. Clin. Oncol. 2011, 29, 3114–3119. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, B.; James, L.P.; Moskowitz, C.S.; Guo, P.; Ginsberg, M.S.; Lefkowitz, R.A.; Qin, Y.; Riely, G.J.; Kris, M.G.; Schwartz, L.H.; et al. Evaluating Variability in Tumor Measurements from Same-day Repeat CT Scans of Patients with Non–Small Cell Lung Cancer. Radiology 2009, 252, 263–272. [CrossRef]

- Nishino M, Guo M, Jackman DM, et al: CT tumor volume measurement in advanced non-small-cell lung cancer: performance characteristics of an emerging clinical tool. Acad Radiol. 2011, 18, 54-62. [CrossRef]

- Greenberg V, Lazarev I, Frank Y, et al: Semi-automatic volumetric measurement of response to chemotherapy in lung cancer patients: how wrong are we using RECIST? Lung Cancer 2017, 108: 90-95. [CrossRef]

- Dinkel J, Khalilzadehd O, Hintzee C, et al: Interobserver reproducibility of semi-automatic tumor diameter measurement and volumetric analysis in patients with lung cancer. Lung Cancer 2013, 82: 76-82. [CrossRef]

- Hayes SA, Pietanz MC, O'Driscoll D, et al: Comparison of CT volumetric measurement with RECIST response in patients with lung cancer. EJR 2016, 85: 524-533. [CrossRef]

- Takahara, T.; Imai, Y.; Yamashita, T.; Yasuda, S.; Nasu, S.; Van Cauteren, M. Diffusion weighted whole body imaging with background body signal suppression (DWIBS): technical improvement using free breathing, STIR and high resolution 3D display.. 2004, 22, 275–82.

- Kwee, T.C.; Takahara, T.; Ochiai, R.; Nievelstein, R.A.J.; Luijten, P.R. Diffusion-weighted whole-body imaging with background body signal suppression (DWIBS): features and potential applications in oncology. Eur. Radiol. 2008, 18, 1937–1952. [CrossRef]

- Usuda, K.; Iwai, S.; Funasaki, A.; Sekimura, A.; Motono, N.; Matoba, M.; Doai, M.; Yamada, S.; Ueda, Y.; Uramoto, H. Diffusion-weighted magnetic resonance imaging is useful for the response evaluation of chemotherapy and/or radiotherapy to recurrent lesions of lung cancer. Transl. Oncol. 2019, 12, 699–704. [CrossRef]

- Ohno, Y.; Koyama, H.; Onishi, Y.; Takenaka, D.; Nogami, M.; Yoshikawa, T.; Matsumoto, S.; Kotani, Y.; Sugimura, K. Non–Small Cell Lung Cancer: Whole-Body MR Examination for M-Stage Assessment—Utility for Whole-Body Diffusion-weighted Imaging Compared with Integrated FDG PET/CT. Radiology 2008, 248, 643–654. [CrossRef]

- Takenaka D, Ohno Y, Matsumoto K, Aoyama N, Onishi Y, Koyama H, et al. Detection of bone metastases in non-small cell lung cancer patients: comparison of whole-body diffusion-weighted imaging (DWI), whole-body MR imaging without and with DWI, whole-body FDG-PET/CT, and bone scintigraphy. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2009; 30(2): 298– 308. [CrossRef]

- Sommer, G.; Wiese, M.; Winter, L.; Lenz, C.; Klarhöfer, M.; Forrer, F.; Lardinois, D.; Bremerich, J. Preoperative staging of non-small-cell lung cancer: comparison of whole-body diffusion-weighted magnetic resonance imaging and 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose-positron emission tomography/computed tomography. Eur. Radiol. 2012, 22, 2859–2867. [CrossRef]

- Usuda K, Zhao XT, Sagawa M, Matoba M, Kuginuki Y, Taniguchi M, et al. Diffusion-weighted imaging is superior to PET in the detection and nodal assessment of lung cancers. Ann Thorac Surg. 2011; 91(6): 1689– 95. [CrossRef]

- Usuda, K.; Sagawa, M.; Motono, N.; Ueno, M.; Tanaka, M.; Machida, Y.; Maeda, S.; Matoba, M.; Kuginuki, Y.; Taniguchi, M.; et al. Diagnostic Performance of Diffusion Weighted Imaging of Malignant and Benign Pulmonary Nodules and Masses: Comparison with Positron Emission Tomography. Asian Pac. J. Cancer Prev. 2014, 15, 4629–4635. [CrossRef]

- Kosucu P, Tekinbas C, Erol M, Sari A, Kavgaci H, Öztuna F, et al. Mediastinal lymph nodes. Assessment with diffusion-weighted MR imaging. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2009; 30(2): 292– 7. [CrossRef]

- Nomori, H.; Mori, T.; Ikeda, K.; Kawanaka, K.; Shiraishi, S.; Katahira, K.; Yamashita, Y. Diffusion-weighted magnetic resonance imaging can be used in place of positron emission tomography for N staging of non–small cell lung cancer with fewer false-positive results. J. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 2008, 135, 816–822. [CrossRef]

- Usuda, K.; Iwai, S.; Funasaki, A.; Sekimura, A.; Motono, N.; Matoba, M.; Doai, M.; Yamada, S.; Ueda, Y.; Uramoto, H. Diffusion-Weighted Imaging Can Differentiate between Malignant and Benign Pleural Diseases. Cancers 2019, 11, 811. [CrossRef]

- Yabuuchi, H.; Hatakenaka, M.; Takayama, K.; Matsuo, Y.; Sunami, S.; Kamitani, T.; Jinnouchi, M.; Sakai, S.; Nakanishi, Y.; Honda, H.; et al. Non–Small Cell Lung Cancer: Detection of Early Response to Chemotherapy by Using Contrast-enhanced Dynamic and Diffusion-weighted MR Imaging. Radiology 2011, 261, 598–604. [CrossRef]

- Nunes, T.F.; Szejnfeld, D.; Szejnfeld, J.; Kater, C.E.; Faintuch, S.; Castro, C.H.M.; Goldman, S.M. Assessment of Early Treatment Response With DWI After CT-Guided Radiofrequency Ablation of Functioning Adrenal Adenomas. Am. J. Roentgenol. 2016, 207, 804–810. [CrossRef]

- Koh, D.-M.; Scurr, E.; Collins, D.; Kanber, B.; Norman, A.; Leach, M.O.; Husband, J.E. Predicting Response of Colorectal Hepatic Metastasis: Value of Pretreatment Apparent Diffusion Coefficients. Am. J. Roentgenol. 2007, 188, 1001–1008. [CrossRef]

- Heijmen, L.; Verstappen, M.C.; ter Voert, E.E.; Punt, C.J.; Oyen, W.J.; de Geus-Oei, L.-F.; Hermans, J.J.; Heerschap, A.; van Laarhoven, H.W. Tumour response prediction by diffusion-weighted MR imaging: Ready for clinical use?. Crit. Rev. Oncol. 2012, 83, 194–207. [CrossRef]

- Chiou VL, Burotto M: Pseudoprogression and immunerelated response in solid tumors. J Clin Oncol 2015, 33, 3541-3543. [CrossRef]

- Tazdait M, Mezquita L, Lahmar J, et al: Patterns of responses in metastatic NSCLC during PD-1 or PDL-1 inhibitor therapy: comparison of RECIST 1.1, irRECIST and iRECIST criteria. Eur J Cancer 2018, 88: 38-47. [CrossRef]

- Usuda, K.; Iwai, S.; Yamagata, A.; Iijima, Y.; Motono, N.; Matoba, M.; Doai, M.; Yamada, S.; Ueda, Y.; Hirata, K.; et al. Diffusion-weighted whole-body imaging with background suppression (DWIBS) is effective and economical for detection of metastasis or recurrence of lung cancer. Thorac. Cancer 2021, 12, 676–684. [CrossRef]

- Usuda, K.; Iwai, S.; Yamagata, A.; Iijima, Y.; Motono, N.; Matoba, M.; Doai, M.; Hirata, K.; Uramoto, H. Whole-Lesion Apparent Diffusion Coefficient Histogram Analysis: Significance for Discriminating Lung Cancer from Pulmonary Abscess and Mycobacterial Infection. Cancers 2021, 13, 2720. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).