1. Introduction

The infectious disease of the COVID-19 pandemic has affected all aspects of human life, including business, research, education, health, economics, sports, transportation, worship, social interactions, politics, governance, and entertainment (1). Research that tried to capture the effects of the pandemic has concluded that the new coronavirus (SARS-CoV-2) and the corresponding disease (COVID-19) have had a major impact on people's mental health and behavior (2).

There are a multitude of studies that have analyzed the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on student learning. These studies showed that the emergence of the COVID-19 pandemic generated major changes in almost all aspects of society, which led to the emergence of negative effects in the educational process in higher education (3). Likewise, these studies showed that the period in which university courses were exclusively online had an impact on the motivation and involvement of students in the educational process (4). Along with the previously mentioned aspects, the researchers also identified a series of problems related to the limited access to educational technological tools and accessing online platforms due to the precarious financial situation, especially in the case of developing countries, arguing that the emergence of the COVID pandemic-19 has negatively affected the education of students causing educational institutions to adapt their teaching and learning methods (5).

Starting from March 11, 2020, the Romanian Ministry of Education and Research decided to suspend face-to-face courses in the pre-university education system. As a result of this decision, combined with the evolution of the pandemic at the national level, the "1 December 1918" University in Alba Iulia decided that from March 18, 2020, to suspend face-to-face activities for a short period of time and reorient itself towards new ways of communication and learning through which to ensure the continuity of learning, using online platforms. Considering the rapid evolution of the pandemic, it was subsequently decided that the online education process should be extended until the end of the academic year.

Under these circumstances, a series of logistical, pedagogical, technical, and content impediments inevitably arose in the field of many school subjects (6). Digital technology supported the continuation of online teaching activities throughout the suspension of face-to-face classes, even if the teaching staff drew attention to the fact that some of the teaching activities, such as those in the laboratories, could not be carried out in the online system because they can have a negative impact on the acquisition of basic knowledge in the studied fields. (7-9).

Studies on the effects of the Covid-19 pandemic have identified different issues related to the assessment process and examination modalities compared to the forms of assessment used before the pandemic. The data of the studies showed that the education process with a low level of relationship for students and the absence of consultation with teachers when they encountered difficulties in going through, understanding, or memorizing didactic materials, led to a decrease in performance in semester exams with an impact on the grades they received (10). Online student assessments have had many challenges and errors, insecurity and inaccuracy among teachers and students (11).

Current research has highlighted the fact that the emergence of the Covid 19 pandemic also had remarkable consequences on the economic, social and psychological situation of students (11). Students had to change their learning method from the traditional classroom model to the online teaching system. Specialists in the field of education have captured how the traditional education process, carried out face-to-face in classrooms, has turned into an education process carried out at the student's home using the online system based on accessing some specialized platforms in this field (12, 13).

Online learning through dedicated platforms was used to conduct courses and transmit information, which raised some problems among students from the perspective of the fact that accommodation had to be done quickly. This aspect led to a psychological impact on the students. According to the researchers who studied this phenomenon, it should be emphasized that the psychological effects left by the pandemic can be long-lasting (14-17), due to quarantine periods, social isolation, and travel restrictions. Although all these measures have been implemented to prevent and reduce the spread of COVID-19 pandemic, their psychological consequences are many (18-20).

One of the mechanisms for adapting to the stress caused by this pandemic period also refers to coping. Researchers in the field of behavioral psychology define coping as "constantly changing cognitive and behavioral efforts to manage specific external and/or internal demands that are appraised as taxing or exceeding the resources of the person" (21). Coping strategies can be classified into adaptive strategies that include active adaptation skills manifested by solving problems but also by maintaining social and emotional support to overcome stressful situations (22).

Another classification of coping strategies refers to maladaptive strategies aimed at avoidance, self-blame and sometimes the emergence of addictions especially among adolescents and young people (23). This type of maladaptive coping can generate many psychological problems and lead to depressive symptoms (24) or anxiety-related problems for adults (23).

2. Materials and Methods

The present study aims to identify the educational and social impact produced by the pandemic period by moving from face-to-face education to exclusively online education of students and master's students majoring in Social Work, Occupational Therapy and Design and Management of Social and Health Services from the Department of Social Sciences of the Faculty of Law and Social Sciences of the University "1 December 1918" in Alba Iulia, Romania and also to discover existing support methods for them, making it easier for them to adapt to this new type of learning, considering the fact that, despite the setback of the pandemic, the online system is still used for education.

2.1. Participants

To conduct the study, an interview guide was designed and distributed to students using Google Docs - Blank Quiz. From the total number of students of the previously mentioned specializations (127 students), a number of 79 students answered, which represents 62%. The participation in the study was voluntary and the answers were anonymous, the students being informed from the beginning what was the purpose of the study.

2.2. The research tool

The interview guide included general questions about their year of study and specialization and questions related to the difficulties encountered by them during online activities, both regarding knowledge and familiarity with online platforms and the consequences of excessive use of these platforms.

3. Results

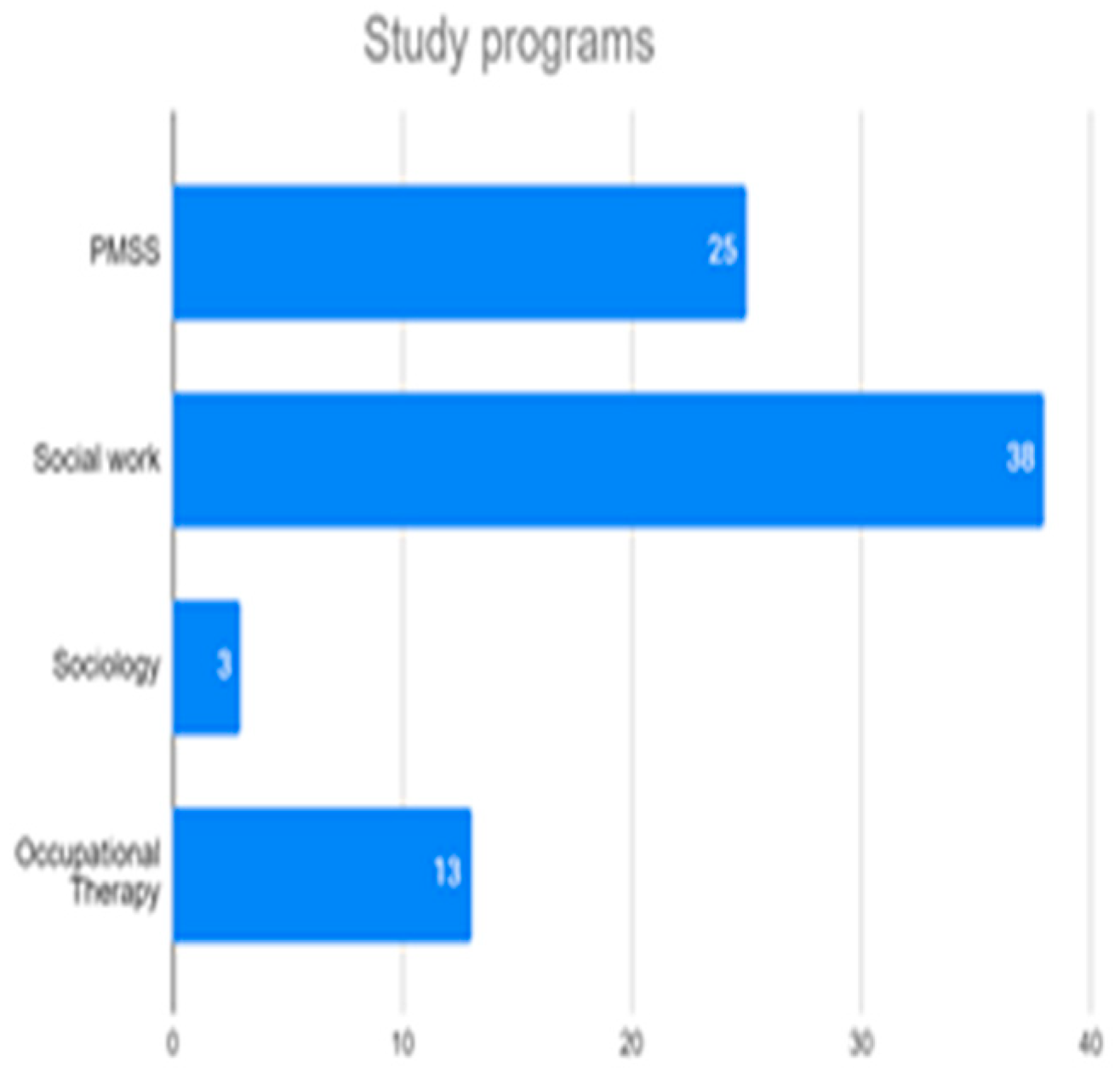

Out of the total of 79 responses, the most are given by students from the Social Work (AS) specialization, 38 responses (48.1%), and which is a bachelor's level specialization, followed by the Social Services Design and Management specialization and Health (PMSS) with 25 responses (31.6%) and which is a master's degree in the field of Social Assistance (AS). There were 13 (16.5%) responding students of the Occupational Therapy specialization and 3 answers (3.8%) were received from the Sociology specialization. The small number of responses received from the Occupational Therapy and Sociology specializations is because the number of students is not very high, rarely exceeding 25 students per study group. The distribution of students according to the specialization followed is shown in figure 1.

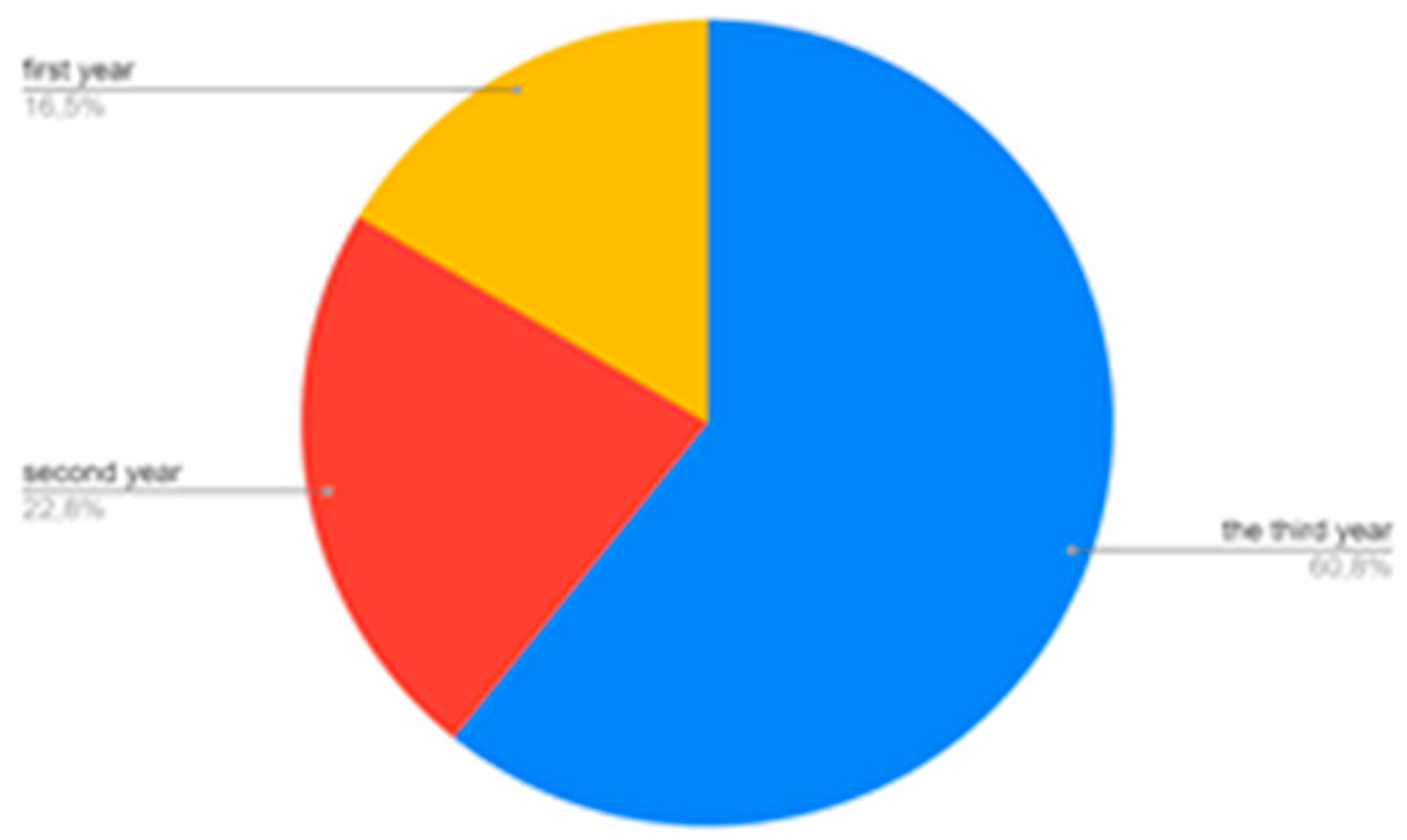

Most of the respondents are from the students of the third year of study, 48 (60.8%), because they spent the most time in online activities. There are also a larger number of second-year students, 18 respondents (22.8%), especially since within this segment there are also master's degree students. There are also 13 (16.5%) first-year students in the master's profile, as they attended online courses during their undergraduate studies. The selection of students according to the year of study followed the integration in the study of the respondents who participated in the didactic activities and the evaluation process in our university.

The data on this aspect were systematized and presented in diagrams (

Figure 1 and

Figure 2).

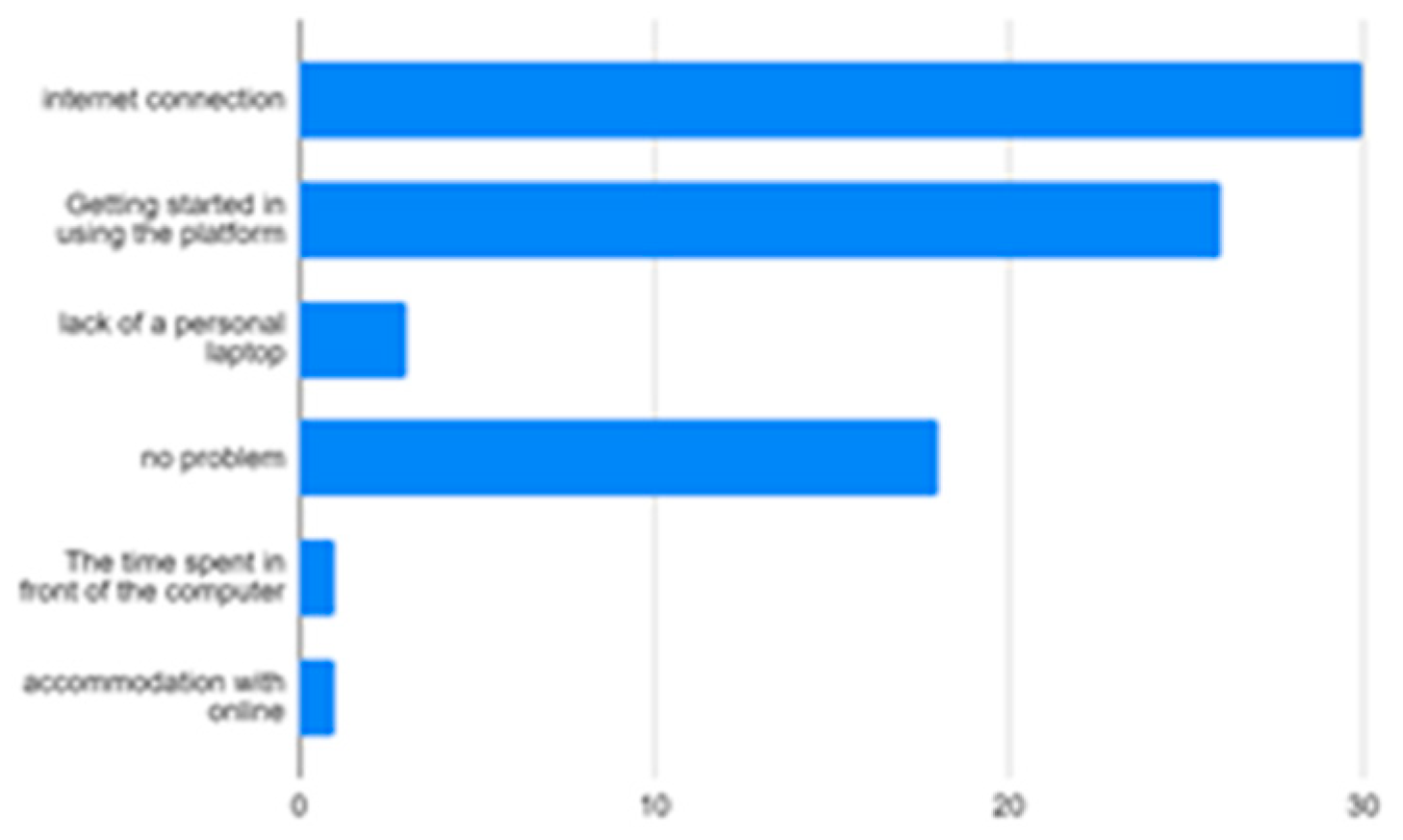

In the first part of the interview guide, we wanted to know the problems faced by the students both at the beginning of the online activities and during these activities in order to have a clearer picture of the difficulties encountered. Starting from the investigation of these aspects, we can have a realistic vision of how the students were able to manage the stressful situations generated by the online education period in conjunction with the protective measures established by the competent institutions in the field of public health.

Most of the problems were related to the quality of the Internet service, which in some areas, especially in the mountainous areas, had a poor quality, which generated frequent interruptions of the classes, leading to the lack of important information for students. The students also confirmed the fact that the use of a new and unknown platform by them led to the emergence of situations of non-fulfillment of the tasks requested by the teaching staff or non-compliance with the teaching period of these tasks.

This information was systematized and presented in diagrams (

Figure 3 and

Figure 4).

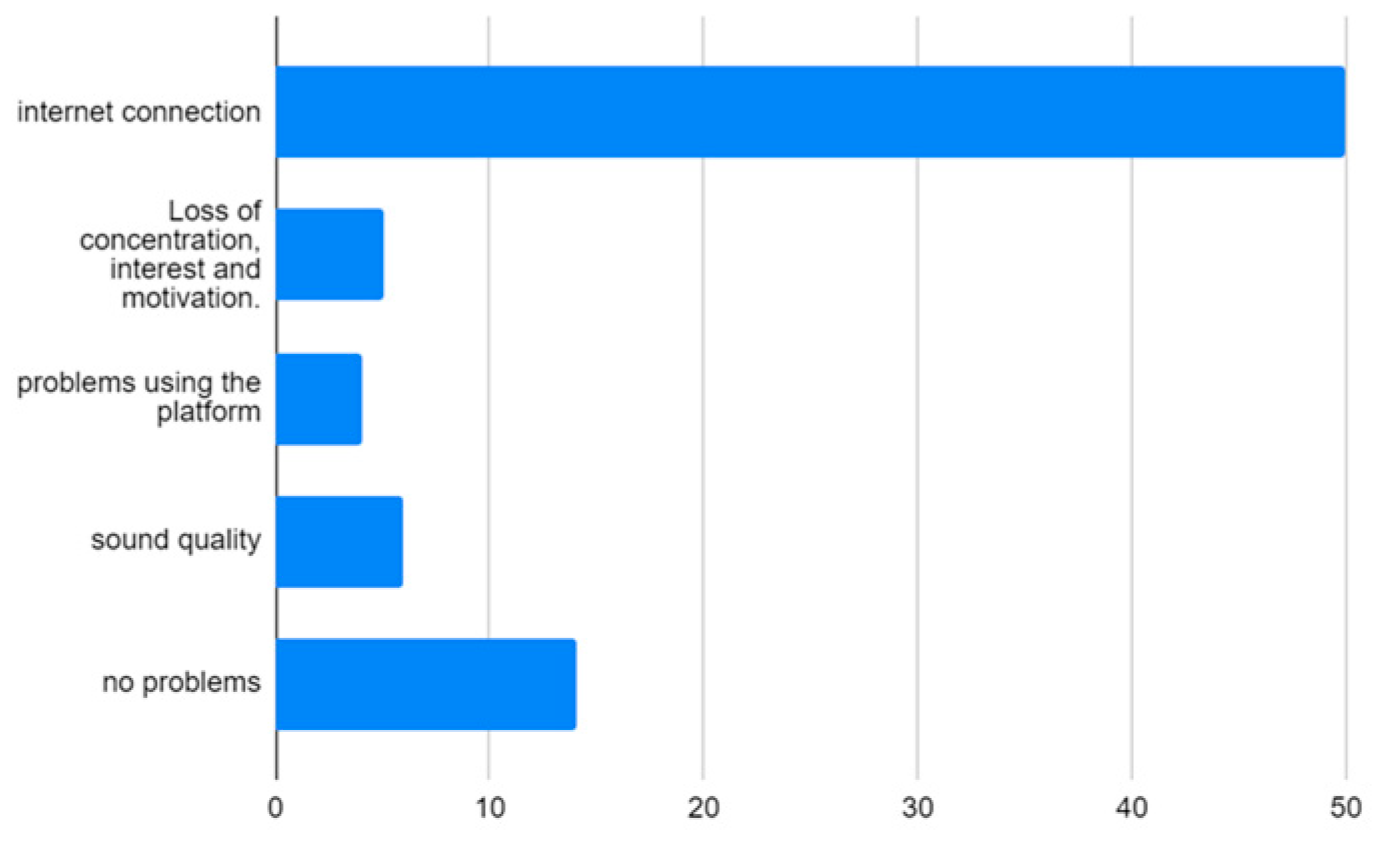

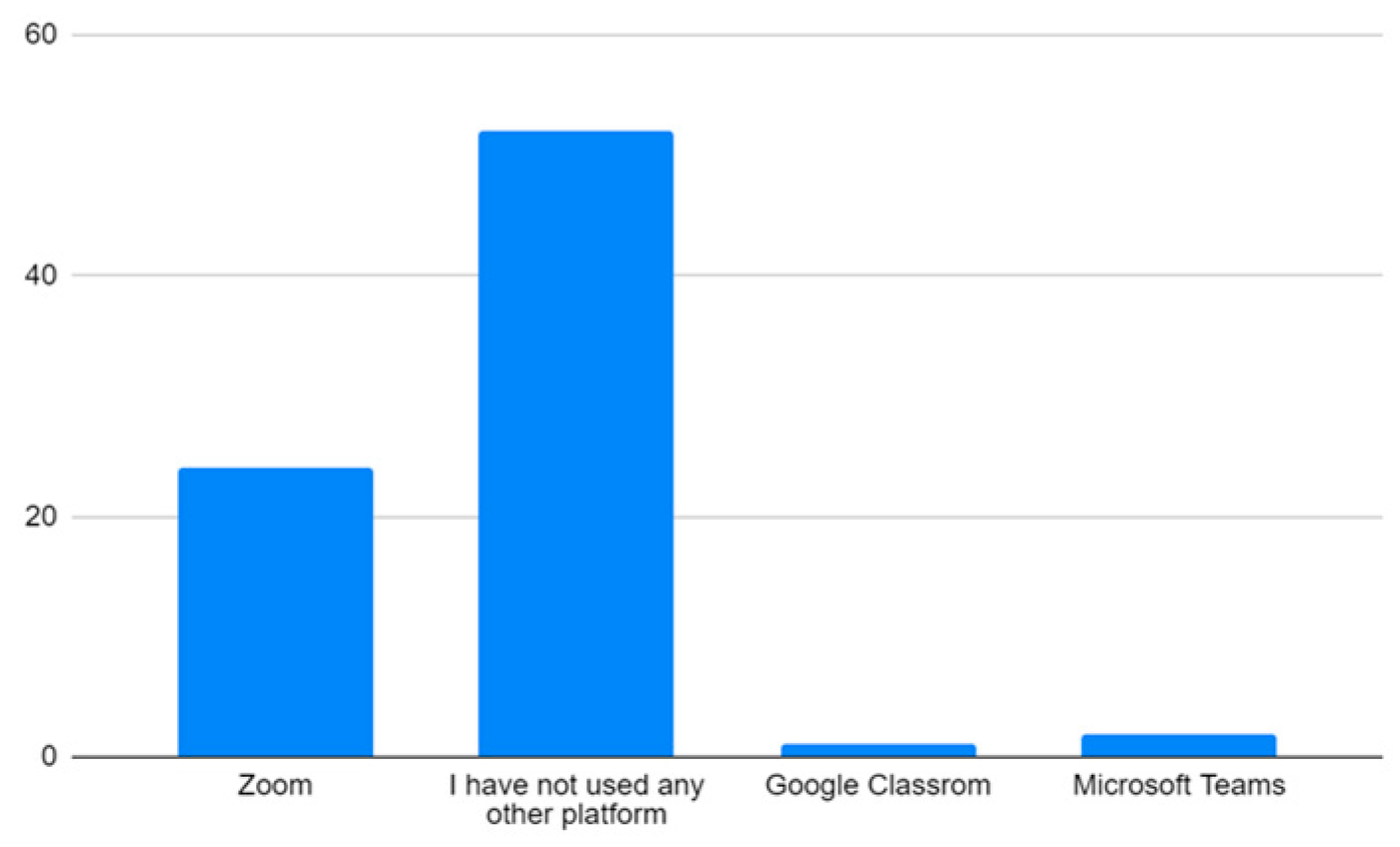

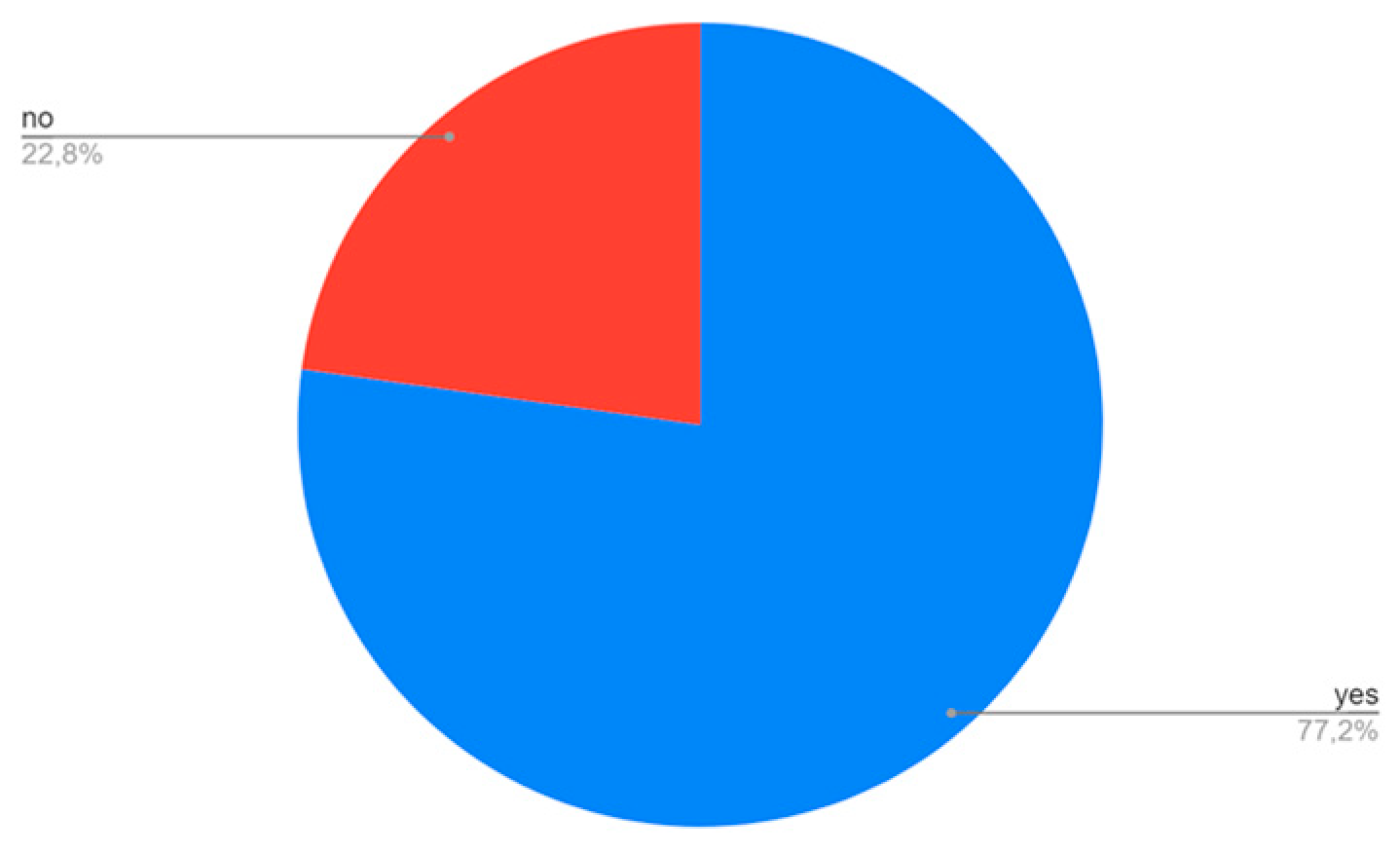

The period of online education among students meant a challenge, because in a very short time they had to familiarize themselves and learn to use new electronic platforms. The interviewed students confirmed in significant numbers that they had not used online platforms before the start of the pandemic, and those who had used platforms stated that they had used the ZOOM platform. Due to this fact, a large part of the respondents needed support and guidance in understanding the functions of the platform used in our university, namely Microsoft Teams.

Student responses were systematized and transcribed into diagrams (

Figure 5 and

Figure 6).

The problems mentioned by the investigated students in relation to the use of online platforms were, for the most part, related to the ways of posting information, uploading materials, or sharing screens in most cases. All these encountered difficulties, especially during the seminar activities, created a series of stressful situations among the students.

They mentioned that they needed technical assistance either from peers or even from teachers.

All the stressful situations, to which the students were subjected during the period of accommodation to a new way of education, and respectively to online education, could generate problems in the socialization process that suffered due to the lack of interaction with colleagues and teachers. It is important to remember that school is a complex socializing agent that, through the values transmitted, places an important emphasis on the personality of the students.

Students were asked about the lack of direct interaction with peers and teachers and how this lack affected them. 73% of the interviewed students answered that they were affected due to the following situations: the lack of interaction with teachers and colleagues, which was a favorite activity for them, expressing themselves in front of a screen and implicitly the lack of feedback from colleagues or the teaching staff, spending a long time in front of the computer led to a decrease in interest and attention. For the students who started in year 1 directly in an online education process it was even more difficult because in the absence of direct interaction with colleagues and teaching staff, they admitted that they did not feel part of the academic system.

We also tried to follow up if the students, as a result of the lack of direct interaction, experienced behavioral or emotional changes. Thus, 57% of the students who wanted to respond to this interview admitted that they felt changes both behaviorally and emotionally. The respondents also mentioned that "in terms of communication with those around me, I have become a more withdrawn and shyer person. There is the fear of not being able to string together a coherent and fully understood sentence", "Emotional yes, I can't explain why I feel embarrassed when connecting with video and it seems more tiring to sit in front of the computer for 2 hours". There were also answers that again captured the problem related to the lack of direct interaction with colleagues and teachers or that of adapting to a new educational model that generated in most cases a decrease in interest in the education process as it was specified by a respondent "I realized that I am no longer as attentive and focused as I was in face-to-face classes".

Towards the end of the interview, we also wanted to find out some aspects related to how the students’ felt changes regarding the number of tasks for independent activities. After analyzing the answers, we found that 62% of the students stated that during the period of online didactic activities they received more tasks to complete than in the previous period. These tasks included the completion of various projects and portfolios that mostly required time spent in front of the computer. All these aspects led the student to spend a large part of his time in front of electronic devices, affecting him both physically and mentally.

Likewise, an important element in the study was to know if, in the opinion of the students, online learning activity contributed to the increase of the educational act, compared to the face-to-face learning activities. The students' answers showed that, in a proportion of 60.8%, in their opinion the period of online education did not have any important contribution in the education process. Most of the negative responses received sounded the alarm about the lack of attention and concentration in online classes. Thus, we mention answers such as: "The student is much „looser” behind the screens. That is, he no longer has the sense of responsibility to wake up and go to classes; he turns on the laptop and falls asleep instead. He is not paying attention, especially if he is with the camera and the sound off. In conclusion, I consider that the online learning activity did not contribute to the increase of the educational act, compared to the face-to-face learning activities" or "I do not think that the online learning activity contributes to the increase of the quality of the educational act, because there are many things which cannot be covered online. I don't think we're seeing the effects now, but they're definitely there."

It was found that there were also a number of students (39.2%) who considered this period opportune to increase the quality of the educational act. These things are because a significant part of the students of these specializations are full-time employees, and this period of online education has facilitated their access to classes. But these aspects could have also been against them because the access to the learning platform was done from the workplace and most of the time the student could not participate actively and attentively in the classes and seminar, being focused on the required tasks of the workplace. So, I received the following answers: "Yes because there are many students who work and cannot be present at the classes, but at the same time there was no face-to-face interaction", "I work, it was easier for me to participate on -line, than physically and I was more present than in the physical system".

If we make a connection with the previous question, we can see that the percentages are quite close, which can lead us to state that during the entire period of online education, students experienced different difficulties that had an impact on the educational act and even if the number of tasks received by students increased during that period, this did not lead to an increase in the quality of the educational act, nor to higher grades received by students at the completion of the classes.

To complete our study, we wanted to see if students have preferences related to face-to-face or online education. In this regard, they were asked whether online meetings can take the place of face-to-face meetings, and they were asked to justify the answer provided. Most of the students answered that online meetings cannot replace the face-to-face education process, specifying that "face-to-face interaction is important in understanding and explaining the subject", "you cannot communicate as effectively as when you communicate face-to-face" or "there is a lack in direct communication, the optimal relationship with teachers and colleagues, the feedback necessary for a good understanding".

We can conclude, from the analysis of the answers received, that many students encountered difficulties during the online activities both from a logistical, emotional, and personal development point of view.

The strategies used by students to cope with the changes produced by the pandemic were more often maladaptive than adaptive because they preferred not to confront the stressors, they were subjected to but to accept and adapt to them (25).

The results of this study help us to understand what the students felt emotionally and socially during the online education process and how they managed to cope with these problems. Most of the time they preferred to use different strategies to be able to get over the crisis periods. If students' problems are not treated correctly and realistically intervened, the effects of crisis periods become acute and become a chronic condition (17). To support students, universities are forced to offer help in any form to facilitate their free expression of what they feel while maintaining their confidentiality.

4. Discussion

This study examined the impact produced by the transition of the instructional-educational process from the traditional, face-to-face, to the online one on students as a result of the Covid 19 pandemic. In these conditions, it became a priority for the staff in university education to identify alternative education paths and strategies to support students and facilitate their access to continuing education. The strategies thought up by them wanted to maintain the mental and emotional health of the students as well as the teaching staff, focusing on the transmission of relevant information, optimizing communication, reducing periods of inactivity, making the educational process as attractive as possible and supporting an engaging and efficient atmosphere.

The effects of the pandemic have produced changes in the Romanian educational system, challenging teachers and students to develop their digital skills, having the opportunity to continue using digital technology even after the resumption of "face-to-face" courses, within the educational act (26).

As a result of the emergence of the COVID-19 pandemic, several studies were conducted that aimed to measure the psychological impact on students as a result of the transition from traditional classrooms to online learning. These aspects were also pointed out by the researchers who considered that the learning process can be done anywhere due to the lack of space and time constraints (26). The online instructional-educational process was the best choice in the case of the COVID-19 pandemic, even if this type of education has a negative effect on students (27-30) especially in the case of those who have difficulties connecting to the internet or use of electronic devices. Problems during online classes, in some cases, affected the grades received by students in the exam session, causing them to develop depression and anxiety (31, 32).

Accordingly, digital learning was expected to significantly improve cognitive achievement, skills, competencies, attitudes, and learning outcomes for higher education students during COVID-19 pandemic (33). Conversely, recent studies in many countries showed adverse online influences amid COVID-19 pandemic among students in higher education; for example, in the Philippines, students experienced different drawbacks to learning online issues such as low cognitive achievement, insufficient skills, and negative attitudes (34,35). In China, research results showed a significant lack of students’ extrinsic motivation, intrinsic motivation, and deep cognitive engagement (36,37). In Pakistan, educators experienced various constraints in executing their duties and responsibilities amid COVID-19 pandemic, which affected learning outcomes (38,39). In India, the usage of online during the COVID-19 pandemic has increased the lack of skills, time management, the lack of infrastructure/resources, poor communication at various levels, negative attitude, and student engagement (40). In Saudi Arabia, despite the availability of an excellent technological infrastructure, investigators have reported on several of the adverse influences of online among higher education students amid COVID-19 pandemic: low self-efficacy, lack of engagement and motivation, negative attitudes, cognitive load, and absence of goals (41,42,43); also, they students mainly concerned about passing exams amid this educational situation (44).

Following the outbreak of this pandemic, all the people involved in the educational process (teachers, students) had to have new experiences generated by the rules imposed due to social distancing and different sanitation rules. So that the studies that will be carried out later will have to document the experiences lived by those involved in the education process in order to be able to identify effective strategies that contribute to the improvement of the instructive-educational process, especially in such situations such as the occurrence of a pandemic.

The most appropriate strategies that we can use are those related to coping, and especially the adaptive ones that are based on the identification of social support as shown by other studies undertaken previously (25, 45). Social support is achieved when a person tells their problems to another person, a fact that, most of the time, is interpreted as a weakness or vulnerability (45). Most often, seeking social support was associated with high levels of anxiety, while the accepted coping strategies were associated with low levels of anxiety (18). Although the pandemic is coming to an end, the effects of the period full of restrictions are being felt among students through the need to adapt to a new way of life or a "new normal". This, in turn, can affect students' academic performance. (18).

Moreover, several studies (46,47) showed that online learning is often undertaken without fully considering the students’ cognitive load, which may lead to decreased competencies, the inability to retain and understand information, the absence of mental goals, and increased negative attitudes. Correspondingly, cognitive load depends on the chosen method of presenting information, student motivation, student involvement, and academic concern (48). According to Chandler and Sweller (49), cognitive load refers to the method in which cognitive mental resources are focused and employed through learning and problem solving. Skulmowski and Xu (50) added that cognitive load is a consequence of the learning path and the critical factors determining the learning outcomes. Therefore, a student feels cognitive load when they cannot process the information and knowledge received during learning (51). Hence, understanding occurs when all learning elements related to the educational contents are processed simultaneously by the working memory (49). Consequently, if the educational contents have multiple factors that cannot be processed simultaneously in the working memory, the learning situation becomes challenging and is not understood, and cognitive load is formed (52). Thus, higher education educators should enhance mental load distribution during online learning (53).

The current article includes some limitations that could be handled in future investigation, including the relationship between online learning sustainability and to maintain the mental and emotional health of the students as well as the teaching staff (54).

5. Conclusions

This study presented how the students at the University of Alba Iulia, within the social specializations, felt the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic in the process of education and professional training. Thus, the impact produced by this period of insecurity was identified both from an emotional and behavioral point of view, although most of the problems identified referred to the education process. Thus, the interviewed students specified numerous problems arising during face-to-face education, starting from difficulties in connecting to educational platforms and up to the increase of student workloads at the expense of the increase in the educational act.

The results of this study could be used by the Information, Counseling and Career Guidance Centers within the universities, by initiating support and support programs for students, especially for those who face various problems of adapting to the new education system. The methods of support offered must be closely related to the issue captured by this study in order to provide adequate and effective support to students with the aim of supporting them during the online educational process. It should also be considered that these changes in the educational process can cause the emergence of adaptation problems, which can serve as support for future studies, with the aim of creating personalized intervention plans dedicated to students with problems of this type.

Funding

This research received no external funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data are not publicly available due to confidentiality reasons.

Acknowledgments

No financial support was received for this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

References

- Orfan, S.N.& Elmyar, A.H. (2020). Public knowledge, practices and attitudes towards covid-19 in Afghanistan. Public Health of Indonesia, 6 (4), 104-115. [CrossRef]

- da Silva ML, Rocha RSB, Buheji M, Jahrami H, Cunha KDC. A systematic review of the prevalence of anxiety symptoms during coronavirus epidemics. J Health Psychol. 2021 Jan; 26(1):115-125. Epub 2020 Aug 23. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Byrnes, Y.M., Civantos, A.M., Go, B.C., McWilliams, T. L., & Rajasekaran, K. (2020). Effect of the COVID-19 pandemic on medical student career perceptions: a national survey study. Medical education online, 25(1), 1798088. [CrossRef]

- Onyema, E.M., Eucheria, N.C., Obafemi, F A., Sen, S., Atonye, F.G., Sharma, A.& Alsayed, A.O. (2020). Impact of Coronavirus pandemic on education. Journal of Education and Practice, 11(13), 108-121. [CrossRef]

- Winters, N. & Patel, K.D. (2021). Can a reconceptualization of online training be part of the solution to addressing the COVID-19 pandemic? Journal of Interprofessional Care, 35(2), 161-163. [CrossRef]

- Botnariuc P., Cucoș, C., Glava C., Iancu D.E., Ilie M.D., Istrate O., Labăr A.V., Pânișoară I.-O., Ștefănescu D., Velea S., (2020), Online school elements for educational innovation, Evaluative research report, Bucharest University Publishing House, p.8.

- Abdulrahim, H.; Mabrouk, F. COVID-19 and the Digital Transformation of Saudi Higher Education. Asian J. Distance Educ. 2020, 15, 291–306. [Google Scholar]

- Sobaih, A.E.E.; Hasanein, A.M.; Abu Elnasr, A.E. Responses to COVID-19 in higher education: Social media usage for sustaining formal academic communication in developing countries. Sustainability 2020, 12, 6520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sobaih, A.E.E.; Palla, I.A.; Baquee, A. Social Media Use in E-Learning amid COVID 19 Pandemic: Indian Students’ Perspective. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 5380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sintema, E.J. (2020). Effect of COVID-19 on the performance of grade 12 students: Implications for STEM education. Eurasia Journal of Mathematics, Science and Technology Education, 16(7), em1851. [CrossRef]

- Pokhrel, S. & Chhetri, R. (2021). A Literature Review on Impact of COVID-19 Pandemic on Teaching and Learning. Higher Education for the Future, 8 (1), 133-141. [CrossRef]

- Sutarto, S., Sari, D.P. & Fathurrochman, I. (2020). Teacher Strategies in Online Learning to Increase Students’ Interest in Learning during COVID-19 Pandemic. Jurnal Konseling dan Pendidikan, 8, 129-137. [CrossRef]

- Nasir., M.K.M., Mansor, A.Z. & Rahman, M.J.A. (2018). Measuring Malaysian Online University Student Social Presence in Online Course Offered. Journal of Advanced Research in Dynamical and Control Systems, 10, 1442-1446.

- Irawan, A.W., Dwisona, D. & Lestari, M. (2020). Psychological Impacts of Students on Online Learning during the Pandemic COVID-19. KONSELI: Jurnal Bimbingan dan Konseling (E-Journal), 7, 53-60. [CrossRef]

- Chung, E., Noor, N. M., & Mathew, V. N. (2020). Are You Ready? An Assessment of Online Learning Readiness among University Students. International Journal of Academic Research in Progressive Education and Development, 9, 301-317.

- Chung, E., Subramaniam, G., & Dass, L. C. (2020). Online Learning Readiness among University Students in Malaysia amidst COVID-19. Asian Journal of University Education, 16, 46-58. [CrossRef]

- Kamaludin, K., Chinna, K., Sundarasen, S., Khoshaim, H. B., Nurunnabi, M., Baloch, G.M., Sukayt, A., & Hossain, S.F.A. (2020). Coping with COVID-19 and Movement Control Order (MCO): Experiences of University Students in Malaysia. Heliyon, 6, e05339. [CrossRef]

- Matias, T., Dominski, F.H. & Marks, D.F. (2020). Human needs in COVID-19 isolation. Journal of health psychology, 25(7), 871-882. [CrossRef]

- Brooks, S.K., Webster, R.K., Smith, L.E., Woodland, L., Wessely, S., Greenberg, N. & Rubin, G.J. (2020). The psychological impact of quarantine and how to reduce it: rapid review of the evidence. The lancet, 395(10227), 912-920. [CrossRef]

- Tull, M.T., Edmonds, K.A., Scamaldo, K.M., Richmond, J.R., Rose, J.P. & Gratz, K.L. (2020). Psychological outcomes associated with stay-at-home orders and the perceived impact of COVID-19 on daily life. Psychiatry research, 289, 113098. [CrossRef]

- Lazarus, R.S., & Folkman, S. (1984). Stress, appraisal, and coping. Springer publishing company, p.141.

- Carver, C.S., Scheier, M.F. & Weintraub, J.K. (1989). Assessing coping strategies: a theoretically based approach. Journal of personality and social psychology, 56(2), 267. [CrossRef]

- Mahmoud, J.S., Staten, R.T., Lennie, T.A. & Hall, L.A. (2015). The relationships of coping, negative thinking, life satisfaction, social support, and selected demographics with anxiety of young adult college students. Journal of Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Nursing, 28(2), 97-108. [CrossRef]

- Main, A., Zhou, Q., Ma, Y., Luecken, L.J., & Liu, X. (2011). Relations of SARS-related stressors and coping to Chinese college students' psychological adjustment during the 2003 Beijing SARS epidemic. Journal of counseling psychology, 58(3), 410. [CrossRef]

- Carrieri, D., Mattick, K., Pearson, M., Papoutsi, C., Briscoe, S., Wong, G. & Jackson, M. (2020). Optimizing strategies to address mental ill-health in doctors and medical students: ‘Care Under Pressure realist review and implementation guidance. BMC medicine, 18(1), 1-10. [CrossRef]

- Bugnariu, A.I., (2020), The impact of the coronavirus pandemic (COVID-19) on the educational system in Romania, PANGEEA, NR. 20.

- Sujarwo, Sukmawati, & Yahrif, M. (2019). Model-Model Pembelajaran: Pendekatan Saintifik dan Inovatif (Jalal, Ed.). Serang Banten: CV.AA.Rizky. http://www.aarizky.com/.

- Aboagye, E., Yawson, J. A., & Appiah, K. N. (2020). COVID-19 and e-Learning: The Challenges of Students in Tertiary Institutions. Social Education Research, 2, 1-8. [CrossRef]

- Putra, P., Liriwati, F.Y., Tahrim, T., Syafrudin, S. & Aslan, A. (2020). The Students Learning from Home Experiences during Covid-19 School Closures Policy in Indonesia. Jurnal Iqra’: Kajian Ilmu Pendidikan, 5, 30-42. [CrossRef]

- Sufian, S.A., Nordin, N.A., Tauji, S.S.N. & Nasir, M.K.M. (2020). The Impact of Covid-19 on the Malaysian Education System. International Journal of Academic Research in Progressive Education & Development, 9, 764-774. [CrossRef]

- Kalok, A., Sharip, S., Abdul Hafizz, A.M., Zainuddin, Z.M., & Shafiee, M.N. (2020). The Psychological Impact of Movement Restriction during the COVID-19 Outbreak on Clinical Undergraduates: A Cross-Sectional Study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17, 8522. [CrossRef]

- Odriozola-González, P., Planchuelo-Gómez, á, Irurtia, M.J. & de Luis-García, R. (2020). Psychological Effects of the COVID-19 Outbreak and Lockdown among Students and Workers of a Spanish University. Psychiatry Research, 290, 113108. [CrossRef]

- Gan, W.Y., Nasir, M.T.M., Zalilah, M.S., & Hazizi, A.S. (2011). Direct and indirect effects of sociocultural influences on disordered eating among Malaysian male and female university students. A mediation analysis of psychological distress. Appetite, 56(3), 778-783. [CrossRef]

- Al-Nofaie, H. Saudi University Students’ perceptions towards virtual education During Covid-19 PANDEMIC: A case study of language learning via Blackboard. Arab World Engl. J. (AWEJ) 2020, 11, 4–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oducado, R.M.F.; Soriano, G.P. Shifting the education paradigm amid the COVID-19 pandemic: Nursing students’ attitude to E learning. Afr. J. Nurs. Midwifery 2021, 23, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Catacutan-Bangit, A.E.; Bringula, R.P.; Ulfa, S. Predictors of Online Academic Self-Concept of Computing Students. In Proceedings of the TENCON 2021–2021 IEEE Region 10 Conference (TENCON), Auckland, New Zealand, 7–10 December 2021; pp. 11–16. [Google Scholar]

- Mok, K.H.; Xiong, W.; Bin Aedy Rahman, H.N. COVID-19 pandemic’s disruption on university teaching and learning and competence cultivation: Student evaluation of online learning experiences in Hong Kong. Int. J. Chin. Educ. 2021, 10, 22125868211007011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, J.-C.; Lee, Y.-F.; Ye, J.-H. Procrastination predicts online self-regulated learning and online learning ineffectiveness during the coronavirus lockdown. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2021, 174, 110673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mushtaque, I.; Awais-E-Yazdan, M.; Waqas, H. Technostress and medical students’ intention to use online learning during the COVID-19 pandemic in Pakistan: The moderating effect of computer self-efficacy. Cogent Educ. 2022, 9, 2102118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ansar, F.; Ali, W.; Khattak, A.; Naveed, H.; Zeb, S. Undergraduate students’ perception and satisfaction regarding online learning system amidst COVID-19 Pandemic in Pakistan. J. Ayub. Med. Coll. Abbottabad. 2020, 32, S644–S650. [Google Scholar]

- Nimavat, N.; Singh, S.; Fichadiya, N.; Sharma, P.; Patel, N.; Kumar, M.; Chauhan, G.; Pandit, N. Online medical education in India–different challenges and probable solutions in the age of COVID-19. Adv. Med. Educ. Pract. 2021, 12, 237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salem, M.A.; Alsyed, W.H.; Elshaer, I.A. Before and Amid COVID-19 Pandemic, Self-Perception of Digital Skills in Saudi Arabia Higher Education: A Longitudinal Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 9886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moawad, R.A. Online learning during the COVID-19 pandemic and academic stress in university students. Rev. Românească Pentru Educ. Multidimens. 2020, 12, 100–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahyoob, M. Challenges of e-Learning during the COVID-19 Pandemic Experienced by EFL Learners. Arab World Engl. J.(AWEJ) 2020, 11, 351–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanafy, S.M.; Jumaa, M.I.; Arafa, M.A. A comparative study of online learning in response to the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic versus conventional learning. Saudi Med. J. 2021, 42, 324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahari, A. Challenges and Affordances of Cognitive Load Management in Technology-Assisted Language Learning: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Hum.–Comput. Interact. 2022, 39, 85–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, Y.; Lee, H. Psychometric Properties for Multidimensional Cognitive Load Scale in an E-Learning Environment. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 5822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afify, M.K. Effect of interactive video length within e-learning environments on cognitive load, cognitive achievement and retention of learning. Turk. Online J. Distance Educ. 2020, 21, 68–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandler, P.; Sweller, J. Cognitive load theory and the format of instruction. Univ. Wollongong 1991, 8, 293–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skulmowski, A.; Xu, K.M. Understanding cognitive load in digital and online learning: A new perspective on extraneous cognitive load. Educ. Psychol. Rev. 2021, 24, 171–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, D.; Kalyuga, S. Confirmatory factor analysis of cognitive load ratings supports a two-factor model. Tutor. Quant. Methods Psychol. 2020, 16, 216–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmeck, A.; Opfermann, M.; Van Gog, T.; Paas, F.; Leutner, D. Measuring cognitive load with subjective rating scales during problem solving: Differences between immediate and delayed ratings. Instr. Sci. 2015, 43, 93–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thees, M.; Kapp, S.; Altmeyer, K.; Malone, S.; Brünken, R.; Kuhn, J. Comparing two subjective rating scales assessing cognitive load During technology-enhanced STEM laboratory courses. In Recent Approaches for Assessing Cognitive Load from a Validity Perspective; Frontier in Education, Frontiers Media SA, 2022. [CrossRef]

- Salem MA, Sobaih AEE. ADIDAS: An Examined Approach for Enhancing Cognitive Load and Attitudes towards Synchronous Digital Learning Amid and Post COVID-19 Pandemic. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(24):16972. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).