1. Introduction

National development, a form of expansion that ensures a better quality of life for present and future generations, is the ultimate goal of sustainable development. Sustainable development is based on three fundamental dimensions: economic growth, societal well-being and environmental quality, without prioritising any one over the other. In summary, economic development will only be sustainable if it has a positive impact on the social environment and the quality of our surroundings. In 2015, the United Nations (UN) adopted the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) (17 goals and 169 targets), which cover three dimensions: social, economic and environmental. The economic objectives are: to promote sustained, inclusive and sustainable economic growth, productive employment and decent work; to build resilient infrastructure, foster inclusive industrialisation and promote innovation; to reduce inequalities between and within countries; and to ensure sustainable consumption and production patterns.

Upon analysis of scientific literature, it has been observed that some researchers identify the development of a country with the process of modernisation of that nation and to assess the trajectory of economic development, they develop an index of structural modernisation, which combines the dimensions of structural change and technological catch-up [

1]. Other authors describe economic modernisation as 'a directed process of economic change aimed at the achievement of certain defined goals or objectives' and is 'conceived as a process by which the economy’s own tendency towards dynamism is realised' [

2].

The authors highlight that the direct correlation between the trend towards modernisation and a sustainable economic environment calls for an interdisciplinary scientific debate. The study shows that many instruments are utilised to assess the economic environment; however, there is an absence of a deeper complex analysis in the context of the sustainability of the economic environment, which would indicate the theoretical constructs of the country’s modernisation, as well as the empirical data. Based on this methodological stance, the research questions are: how does this conceptual shift reflect the changes in the country’s modernisation in the context of the sustainability of the economic environment, and what are the implications for the country?

The aim of the article is to analyse the development of modernisation of Lithuania from the perspective of a sustainable economic environment and to form a complex system of indicators for the formation of purposeful management of a modern country. Reflecting on the purpose of the research, three main fields of analysis are distinguished, which influence the modernisation of the country in the context of a sustainable economic environment:

Developed networking of digital efficiency, infrastructure, environment and natural resources;

Growing interest in the possibilities of renewable energy and its benefits;

Residents are more guided and apply EU ecological trends for the quality of life.

The following (second) section presents the relevant academic literature on the aspects of a country’s development, modernisation, and a sustainable economic environment. The third section provides a methodological framework for the methods used. The fourth section discusses the results, and presents the contribution and limitations of the study, and offers perspectives for future research.

2. Country Development

In the academic literature on modernisation processes, there is a general consensus that the driving force behind modernisation has, in any case, been economic or economic development [

3]. The 20th century is distinguished by several economic theories (see

Table 1).

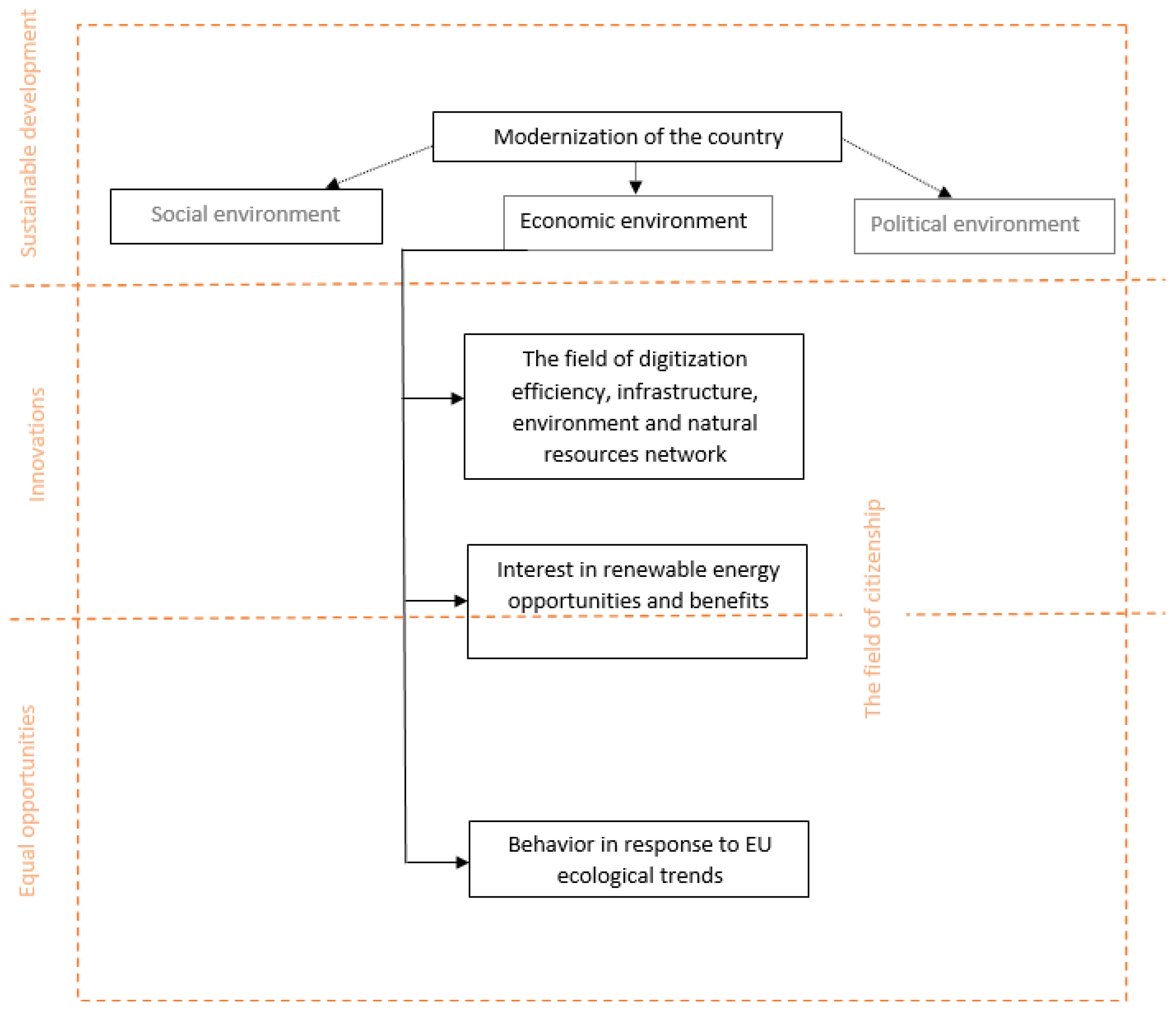

The authors have devised a flowchart for the study of modernisation in the country, considering the analysis of the scientific literature and the National Progress Plan [

5] (see

Figure 1).

According to

Figure 1, three environments are identified: social, economic and political. The economic environment covers three other areas: the efficiency of digitisation, infrastructure, environment and natural resources interoperability; interest in the opportunities and benefits of renewable energy; and behaviour in line with the EU’s environmental trends. The flowchart also contains three horizontal dimensions: sustainable development, innovation and equal opportunities.

2.1. A Sustainable Economic Environment

The basic principles of sustainable development were formulated and endorsed at the 1992 United Nations World Conference on Environment and Development in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. However, to date, scholars have defined sustainable development in different ways. Sustainable development is a form of development that meets the needs of today without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs; a development that improves the quality of life of people while preserving the ecosystem; development that ensures the environmental, economic and social well-being of all members of society without threatening the systems that provide that well-being; development that promotes the economic and social progress of humanity and ensures that this progress is accompanied by progress in other areas [

6]. Sustainability refers to a state of dynamic equilibrium, where a long-term balance between the components of the economic environment and social well-being is sought [

7]. Sustainable development is understood as a nation’s efforts to reconcile and ensure a vibrant economy, a healthy environment and ecology, social well-being, and the active and participatory involvement of the urban community in all phases of the city’s development [

8]. Melnik highlighted that the phenomena, problems and issues of sustainable development can be examined in the following dimensions: encompassing different spatial scales (differently defined regions, individual countries or groups of countries, the world), as well as different systems (different organisations, groups of organisations, systems to be defined in different ways); incorporating into the totality of sustainable development processes different combinations of processes, phenomena, factors and circumstances of social, economic and political development, scientific and technological progress; prioritising different manifestations, consequences or circumstances of sustainable development that are social, economic, ecological, technological, as well as political in nature and otherwise characterised; taking into account the governance characteristics of the various development and progress processes and the multiplicity of the different actors and their interests involved in governance [

9]. Sustainable development is a key priority in creating and improving the macroeconomic environment of organisations [

10].

Masser identified the following principles of sustainable development [

11]: partnership and accountability; active participation and transparency; a systems approach; a link to the future; equity and justice; ecological constraints; the link between the local and the global; and local relevance.

According to the 2015 United Nations Resolution Transforming Our World: the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development is an action plan for people, the planet and prosperity [

12] to be implemented by all countries and stakeholders working together as partners. To achieve the objectives of sustainable development, Lithuania has adopted a National Progress Plan, which identifies the smart economy axes: to move towards sustainable economic development based on scientific knowledge, advanced technologies, innovations and to increase the country’s international competitiveness; to improve transport, energy and digital internal and external connectivity; to ensure a good quality of the environment and the sustainability of the use of natural resources, to protect biodiversity, to mitigate the impact of climate change in Lithuania and to increase its resistance to its effects; to ensure a sustainable and balanced development of Lithuania’s territory and to reduce regional exclusion; to strengthen national security [

5]. Competitiveness and advanced technology and innovation are rarely used in isolation, as well as by distinguishing them from competitors. The usefulness and high potential of understanding, experimenting and learning about competitiveness at different levels, from product, company, industry to group, city or country, especially in large emerging economies increased [

13]. Different researchers have undertaken different studies looking for a link between competitiveness and innovation [

14,

15,

16,

17,

18].

The complexity of the concept of competitiveness stems from the fact that it is used at different levels and in numerous scientific fields. Several scholars have examined competitiveness from the perspective of the employee [

19,

20,

21], the company [

22,

23,

24], the village, the city, the region or the country [

8], [

25,

26,

27,

28,

29], and the industry [

30], [

31]. From an economic standpoint, competitiveness can be analysed in the context of a number of different indicators (level of technology, capital, skills of the company’s workforce, productive capacity, etc.). From an economic and managerial point of view, there are four types of competitiveness: cost competitiveness, price competitiveness, technological competitiveness and structural competitiveness. From a strategic management perspective, competitiveness is when a company has the relevant resources, i.e. employee skills, assets, cash flow, capital and investment, flexibility, balance and dynamism in the organisation’s structure, interaction between the organisation and the environment, as well as company-specific variables (competence, product imitation capabilities, information system, value added and quality).

Infrastructure is a key prerequisite for the development of national, regional and urban economies and for meeting their needs [

32]. Physical infrastructure typically includes roads, pipelines, airports, railways, power lines, gas pipelines, sewerage/drainage systems, information technology and telecommunications infrastructure. The majority of researchers use physical expressions of infrastructure indicators in their studies, i.e. assessing the relationship between the length of roads, the length of pipelines, the number of telecommunication lines, or the number of telephone subscribers, and the impact on economic indicators. However, qualitative indicators equally as important, because the development of an eco-social system does not depend on physical infrastructure alone. Their quality (reliability, timeliness and ease of use) becomes an important characteristic. The scientific literature focuses on the development and security of energy networks. The energy network is the system that supplies electricity, heat and gas to a city. The dependence of energy networks on a single market presents a threat to the city’s economic vulnerability and the city’s economic power, and to the loss of competitive advantages for companies due to increased production costs. Researchers have shown that road length per 1,000 inhabitants, per capita exports, per capita education spending and physical capital stock contribute positively to economic growth [

33]. The development of road infrastructure has a positive impact on economic growth [

34,

35,

36]. The primary role identified for road infrastructure is mobility, which ensures the movement of people, goods and services. It also improves access to certain markets for goods and services. However, countries have sustainable transport targets to achieve the Sustainable Development Goals, i.e. to ensure good environmental quality and sustainable use of natural resources. Sustainable transport aims to ensure that environmental, social and economic factors influence all decisions related to the transport system [

37].

Shemme et al. investigated the role of the transport sector in the energy system and the challenges this poses. They also proposed an assessment for an effective implementation strategy for a future, ideally GHG-neutral, transport sector to meet the European Commission’s Energiewende and Energy Roadmap 2050 targets [

38].

The concept of economic security was introduced by the US President Franklin D. Roosevelt in 1934 with the creation of the Federal Committee on Economic Security [

39]. The objects of economic security can be the state, society, citizens, companies, institutions and organisations, territories and individual objects. The main actor in economic security is the state, which exercises its functions in the field of economic security through the legislative, executive and judicial branches. The economic security aspect is particularly prominent in the three groups of threats to Lithuania’s national security: the eighth (economic and energy dependence, economic and economic vulnerability), the tenth (social and regional exclusion, poverty), and the eleventh (demographic crisis) [

40].

2.2. In Lithuania

According to a report published by the Bank of Lithuania [

41], global GDP forecasts are deteriorating (a drop of 0.4 for 2022 and 0.7 for 2023 between April and July). In the case of the major markets, there is a drop for 2023, i.e. USA - 1.3, China - 0.5, Eurozone - 1.1.

Tracking Lithuania’s key monthly indicators of economic activity, two sectors are experiencing growth, i.e. market services and construction, while the rest, i.e. manufacturing, retail trade, exports of goods of Lithuanian origin, are in decline. Monitoring the unemployment rate and comparing it with the unemployment rate in Q1 to Q3 2022 and 2021, there is a decrease in the unemployment rate; however, if the unemployment rate is monitored in 2022, there is a decrease of 0.9 in Q1 to Q2 and a slight yet visible increase of 0.5 in Q3. There is also a decrease in vacancies in Q3 2022 compared to Q1 2022 by around 2.5%.

The National Industrial Digitalisation Platform 'Industry 4.0', established on the initiative of the Ministry of Economy and industry representatives, will contribute to the accelerated growth of the GVA generated by the industrial sector, to the promotion of the introduction of digital processes in industry, and to the improvement of the international competitiveness of Lithuanian industry and the accelerated growth of the Lithuanian economy [

42].

Gross income per household member in 2021 compared to 2020 has increased in all Lithuanian counties with the exception of Telšiai (a decrease of €57 per household member), with the highest growth in Marijampolė, Vilnius and Alytus counties.

The risk of poverty in 2021 has decreased compared to 2020, both in urban and rural areas. By examining the distribution of households according to the percentage of households that are well or very well off, it is clear that the share of those who are well or very well off increased by 3.3% in 2021 compared to 2020, while the share of those who are very well off decreased by 0.7% in the same period.

Expenditure on research and experimental activities increased by approximately 10% in 2021 compared to 2021.

The largest increases in passenger turnover in Q2 2022 compared to Q2 2022 are observed for inland waterway, maritime, air and rail transport. Upon monitoring the freight turnover of all modes of transport, it is clear there is a significant drop of over 40% in rail freight transport in Q2 2022, whereas there is a slight increase in freight turnover by road, with an increase in inland waterway volumes of around 79%. The decrease in pipeline freight traffic was around 27% over the period under review.

Lithuania is undergoing the Fourth Industrial Revolution, enabling the creation and shaping of a life in which virtual and material production systems interact flexibly. The most intense part of the Fourth Industrial Revolution is in the manufacturing sector. According to the breakdown of enterprises, small and medium-sized enterprises account for 99.8% of all enterprises operating in Lithuania, of which 9.2% are in manufacturing [

42].

The balance of international trade in goods is negative for all commodity groups except: unprocessed industrial goods n.e.c.; processed food and beverages for household consumption; transport equipment for non-industrial use; durable consumer goods n.e.c..; short-term consumer goods n.e.c.; and petrol and commodities n.e.c.

Lithuania’s direct investment abroad increased by €80.87 million. If we analyse investments in the European Union, Lithuanians invest mainly in Latvia and Estonia. Foreign direct investment in Q2 2022 increased by around €450.27 million compared to Q1 2022. The main investors in Lithuania are Germany, the Netherlands, Estonia and Sweden.

The general government deficit in 2021 is €554.8 million and gross debt (nominal value at the end of the period) is €24,535.5 million.

Looking at the monthly business trends using the Economic Assessment Indicator (the arithmetic weighted average of the five component indicators of confidence in the consumer, industry, construction, trade and services sectors (the weights in the EU’s Joint Harmonised EU Programme of Business and Consumer Surveys are 20, 40, 5, 5, 30%, respectively)) as a percentage of GDP), it can be seen that the indicator has a negative trend from March 2022 to November, increasing from -3.9 to -11.9%.

3. Methodology

3.1. Sample and Data Collection Procedure

A representative survey of the Lithuanian population was conducted between 22 November and 30 November 2022 by the Lithuanian-British market and public opinion research company Baltijos tyrimai (Baltic Research) according to a questionnaire agreed with the client. The survey involved 1,015 Lithuanians (age 18 and older).

The results of this survey apply to Lithuanians who are at least 18 years old. The survey was carried out through individual interviews. The age range of this population was chosen in line with the practice of population opinion surveys (ESOMAR) in the EU and to compare the survey results with those of previous studies on this subject.

The respondents of the population survey were chosen using multistage stratified random sampling. 1,015 Lithuanians who were at least 18 years of age participated in the survey. The maximum margin of error allowed by this sample is +- 3.1%. Multiple steps were followed in the selection of respondents:

Determining the proportion of respondents in the districts. All counties are included in this study. The percentage of those surveyed in each county in the overall sample corresponds to the percentage of Lithuania's population over the age of 18 that reside in that county;

Determining the proportion of respondents in different size areas in each county. The categories of settlements used in this study are: Vilnius, large cities (over 50,000 inhabitants), towns (2,000 to 50,000 inhabitants), rural areas (up to 2,000 inhabitants). The number of respondents in the different sizes of each county corresponds to the proportion of the population aged 18 years and over living among the total population of that age in the county;

The selection of particular settlements for the survey is made in the next stage. The areas to be surveyed are chosen at random from the list of settlements in each category (by population size) in each county;

Purposive sampling is used to select respondents. A path is created in each community by altering a certain step in the choice of the residence where the survey is conducted. The nearest birthday rule is used to determine which household responder will be selected. There may be up to 3 attempts (visits) per interview. This method of choosing respondents guarantees the greatest amount of random sampling and the same participation probability.

The survey was carried out between 22 November and 30 November 2022 at 111 sampling points (31 towns and 49 villages). The demographic and social characteristics of the respondents (a total of 1,015 respondents aged 18 years and older) are presented in

Table 2.

Important sociodemographic characteristics of the survey data are compared (age, gender, income groups, type of settlement, social status, and education). With a 50% response rate and a confidence level of 0.95, the margin of error for the survey results cannot be greater than 3.1%. (see

Appendix A). With a 95% confidence level, the margin of error is calculated for a given sample size and response rate.

3.2. Data Analysis Methodology

Nineteen survey questions (statements) were created based on the literature analysis. Questions in the survey's questionnaire are rated on a 5-point Likert scale, from strongly disagree to strongly agree.

First, confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was performed to see if the factor structure could be done in the dataset of 1,015 participants. Second, path analysis (PA) is used for a causal modelling approach to explore the correlations within a defined network of these factors. Goodness-of-fit index (GFI), Chi-square value (CMIN), normed fit index (NFI), relative fit index (RFI), incremental fit index (IFI), Tucker-Lewis index (TLI), comparative fit index (CFI), and approximation root mean square error (RMSEA) were used to evaluate the goodness-of-fit of the network (model) [

43,

44]. Next, multiple group analysis (MGA) was applied to examine differences in the structure of how variables are related between groups [

45].

The Windows statistical package SPSS 28.0 and SPSS Amos 26 were used for CFA and other calculations.

4. Results

4.1. Preliminary Data Analysis

The representation of the sample of a population was first summarized using descriptive statistics. Between means and medians of the variables, there are no significant variances.

38.7% (30.4 and 8.3 cumulative frequency in percent) of respondents believe that they often use the latest technologies, and 48.1% noted that the implementation of new technologies in trade or service supply companies and elsewhere does not bother them, and they are happy to try innovations.

38.7% (30.4 and 8.3 cumulative frequency in percent) of respondents believe that they often use the latest technologies, and 48.1% noted that the introduction of new technologies in trade or service supply companies and elsewhere does not bother them, and they are happy to try innovations.

26.3% (21.8 and 4.5 cumulative frequency in percent) of the respondents agree that they are interested in the latest EU ecological trends, and 33.3% – neither agree nor disagree.

27.4% (24.9 and 2.5 cumulative frequency in percent) of the respondents agree that they have all the opportunities to participate in public activities in Lithuania, 40.5% – neither agree nor disagree. Respondents' participation in some kind of civic activities in the last few years: 30.9% of respondents donated money, things to charity or otherwise supported individuals, public organizations or civic initiatives, 13.1% - participated in environmental management taluks, 3.8 - participated in local community activities.

45.7% (38.8 and 6.9 cumulative frequency in percent) of the respondents agree that they feel safe in Lithuania, 37.4% – neither agree nor disagree. 44.4% (35.3 and 9.1 cumulative frequency in percent) of the respondents agree that they feel completely safe because Lithuania is a member of NATO, 37.1% – neither agree nor disagree. 34.8% (30.7 and 4.1 cumulative frequency in percent) of the respondents agree that they feel completely safe because they believe that the Lithuanian army is adequately prepared, 42.2% – neither agree nor disagree. 23.6% (22.4 and 1.2 cumulative frequency in percent) of the respondents agree that they know how to act in case of mobilization, 37.4% – neither agree nor disagree.

43.0% of the respondents would not do anything if an economic crisis erupted in Lithuania and the standard of living deteriorated significantly, while 16.3% would participate in demonstrations and other protest actions. 30.8% of respondents would stay in Lithuania and do nothing if a hostile state attacks Lithuania or there is a real threat of attack, 25.2% would stay in Lithuania and contribute to the defense of the country by other means (e.g., work in a hospital, contribute to the dissemination of information).

4.2. Results of the Confirmatory Factor Analysis and Path Analysis

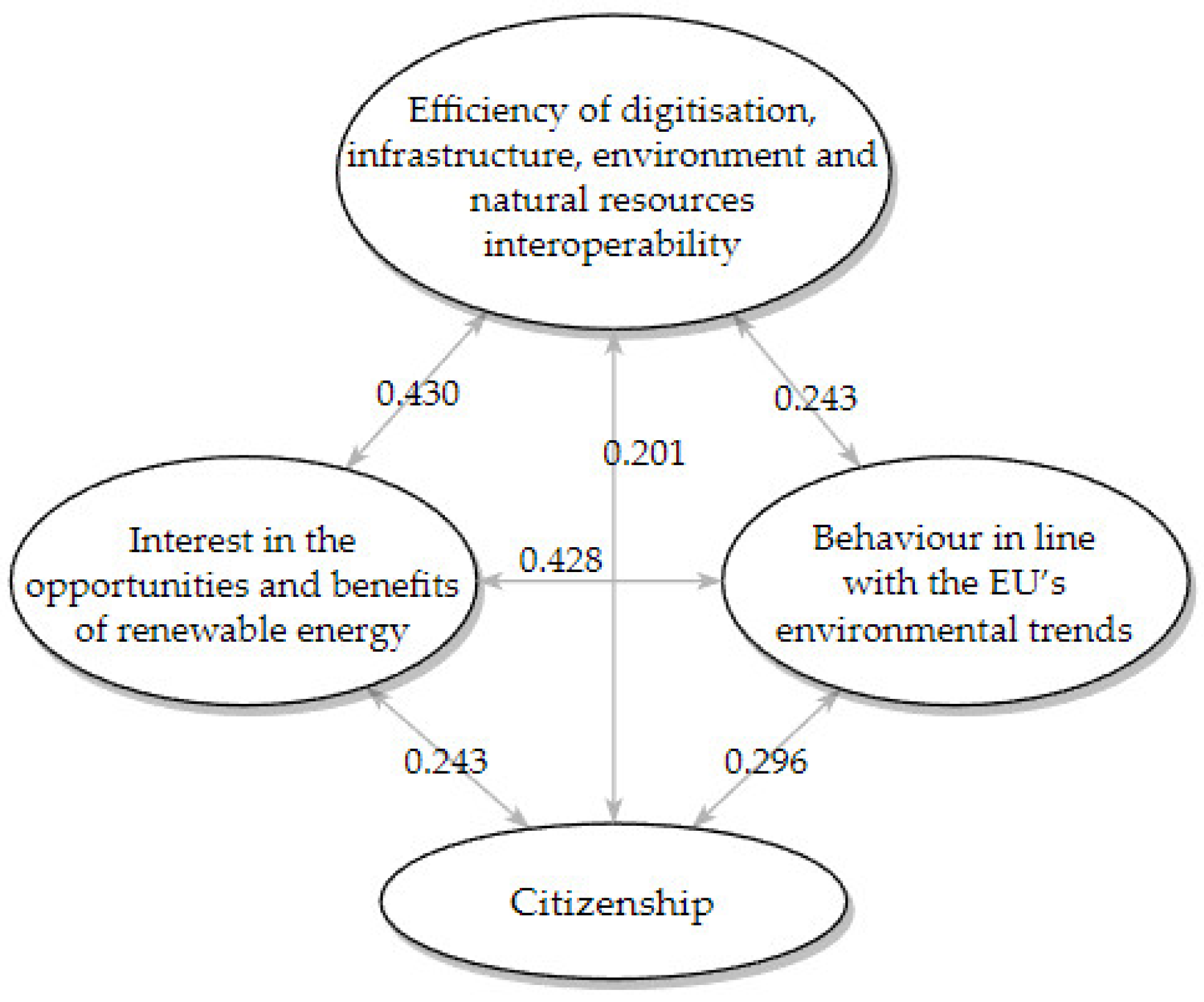

First, according to the flowchart for the study on the modernisation of a country from the perspective of the economic environment, the statements of the survey were grouped into four factors using a factor analysis technique [

46]. Furthermore, variables with factor loadings less than 0.708 were excluded from the further confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) [

47].

Second, the reliability of internal consistency is measured by the Cronbach’s alpha coefficient. All values of the Cronbach’s alpha coefficients are greater than 0.7 and lower than 0.9, which is the acceptable range [

48,

49]. To accommodate the validity of the discriminant, the extracted average variance (AVE) and composite reliability (CR) indices are also evaluated. As seen in

Table 3, their values are greater than 0.5 and 0.7, respectively, which means that items (factors) are considered in agreement with the survey statements [

50].

The path analysis (PA) is then performed. The result of the chi-square goodness of fit test indicates an exact-fitting model, χ

2 = 249.12, p < 0.001. The indicators of at least an acceptable model fit [

51]: NFI is equal to 0.936, RFI is equal to 0.907, IFI is equal to 0.954, TLI is equal to 0.933, CFI is equal to 0.953. RMSEA is considered an 'absolute fit index' and is equal to 0.49, and is less than 0.05, so the network (model) is generally considered indicative of a close-fitting model [

52,

53]. The four-factor network is presented in

Figure 2.

According to data from the Political Participation Index [

54], the activity or passivity of political participation can be partially described by demographic characteristics: more politically active persons are more educated, have higher incomes, have prestigious professions, and are more interested in politics. The earlier study [

55] identified several factors, including family income per month, as relevant for citizenship activities. For example, the higher the family income of the respondents per month, the more active the participation of the respondents in citizenship activities. For this reason, the difference between the sample comprised of respondents whose family income per month is above 1800 EUR (the first group) and the sample comprised of respondents whose family income per month is less than 1000 EUR (the second group) could be examined using multigroup path analysis to distinguish the archived results of the four-factor network for economic environment.

5. Discussion and conclusions

Our research showed that the most important construct in shaping civil society modernisation is the efficiency of digitisation, infrastructure, environment, and natural resources interoperability, as it has a direct impact on all other constructs investigated, namely: Interest in the opportunities and benefits of renewable energy, behaviour in line with the environmental trends of the EU, citizenship. So our findings contribute to the theoretical sprout that states that the ‘hard’ determinants [

56,

57] rather than the ‘soft’ determinants [

58] are the focal point in deciding the development paths of the country and its civil society. These arguments reveal an interesting fact. In the scientific literature, there is consensus that ‘hard’ determinants are more important for the least or developing countries to rule their modernisation trajectories [

59]. It is widely accepted that when the country reaches the level of a developed nation, the ‘soft’ determinants begin to prevail in driving the country’s modernisation further. Lithuania is considered a developed country [

60] with a high income economy [

61]. Although, as our investigation shows, its modernisation is still driven mainly by ‘hard’ factors. This finding not only adds scientific novelty to modernization theory [

62], showing that the modernization of the developed country can still be shaped by the ‘hard’ factors, but also indicates a new and prospective scientific avenue. It would be scientifically sound to investigate why modernisation in some developed countries is driven by ‘hard’ and some by ‘soft’ factors. What are the reasons for determining this difference?

We also prove that the increase in citizenship is affected by all three other constructs investigated. Environmental awareness of society, which is considered one of the indicators of modern society [

63], was split into two distinct constructs, namely interest in the opportunities and benefits of renewable energy and behaviour in line with EU environmental trends. It was done intentionally in an attempt to reveal what is more important in the formation of modern society – the forcefully imposed rules which are being followed by very transparent and strict retribution (behaviour in line with the EU’s environmental trends – ‘hard’ determinant) or ‘soft’ determinants - Interest in the opportunities and benefits of renewable energy. Once again, the ‘hard’ determinant showed a stronger influence on civil society modernisation compared to the ‘soft’ one (correlation coefficients 0.296 vs. 0.243). Although the differences in coefficients are not very hard, it once again confirms [

64] arguments about the importance of the strict rules in achieving the desired attitudes or behavior in the post-Soviet countries. Therefore, our findings confirm the statements of [

65] on the role of cultural legacy in shaping the country’s development in the coming decades. It is worth noting that the correlation coefficients between behaviour according to the environmental trends of the EU and interest in the opportunities and benefits of renewable energy are rather lower, which means that these constructs are not influenced by each other but are driven by different factors. The identification and further investigation of factors behind the above-mentioned constructs could also be a prospective research idea in the area of society modernization studies.

One of the possible limitations of our study lay in the methodology applied. We researched the country’s modernisation through the lens of its main constituent part, the perspective of the citizens. Although we agree that country’s modernization is a very complicated and multifaceted process and its thorough investigation may require the involvement of some experts who could provide the evaluation of some sophisticated processes in the society emerging during the modernisation development. This could also be a valuable future research idea.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, O.N., I.M.-K., R.Č., M.M. and A.V.; methodology, O.N., I.M.-K., R.Č., M.M. and A.V.; software, O.N.; validation, O.N., I.M.-K., R.Č., M.M. and A.V.; formal analysis, O.N., I.M.-K., R.Č., M.M. and A.V.; investigation, O.N., I.M.-K., R.Č., M.M. and A.V.; resources, O.N., I.M.-K., R.Č., M.M. and A.V.; data curation, O.N., I.M.-K., R.Č., M.M. and A.V.; writing—original draft preparation, O.N., I.M.-K., R.Č., M.M. and A.V.; writing—review and editing, O.N., I.M.-K., R.Č., M.M. and A.V.; visualization, O.N., I.M.-K., R.Č., M.M. and A.V.; supervision, O.N.; project administration, O.N.; funding acquisition, O.N. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Research Council of Lithuania (LMTLT) under project agreement No S-MOD-21-10. The funder had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data of this study is available from the authors upon request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest. The funder had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Calculation Table of Answers Errors.

Table A1.

Calculation Table of Answers Errors.

| Sample size (n) |

|---|

| Responses (%) |

10 |

40 |

75 |

100 |

150 |

200 |

250 |

300 |

350 |

400 |

450 |

500 |

600 |

700 |

800 |

900 |

1000 |

| 0.1 |

1.96 |

0.98 |

0.72 |

0.62 |

0.51 |

0.44 |

0.39 |

0.36 |

0.33 |

0.31 |

0.29 |

0.28 |

0.25 |

0.23 |

0.22 |

0.21 |

0.20 |

| 0.5 |

4.37 |

2.19 |

1.60 |

1.38 |

1.13 |

0.98 |

0.87 |

0.80 |

0.74 |

0.69 |

0.65 |

0.62 |

0.56 |

0.52 |

0.49 |

0.46 |

0.44 |

| 1.0 |

6.17 |

3.08 |

2.25 |

1.95 |

1.59 |

1.38 |

1.23 |

1.13 |

1.04 |

0.98 |

0.92 |

0.87 |

0.80 |

0.74 |

0.69 |

0.65 |

0.62 |

| 2.0 |

8.68 |

4.34 |

3.17 |

2.74 |

2.24 |

1.94 |

1.74 |

1.58 |

1.47 |

1.37 |

1.29 |

1.23 |

1.12 |

1.04 |

0.97 |

0.91 |

0.87 |

| 3.0 |

10.57 |

5.29 |

3.86 |

3.34 |

2.73 |

2.36 |

2.11 |

1.93 |

1.79 |

1.67 |

1.58 |

1.50 |

1.36 |

1.26 |

1.18 |

1.11 |

1.06 |

| 4.0 |

12.15 |

6.07 |

4.43 |

3.84 |

3.14 |

2.72 |

2.43 |

2.22 |

2.05 |

1.92 |

1.81 |

1.72 |

1.57 |

1.45 |

1.36 |

1.28 |

1.21 |

| 5.0 |

13.51 |

6.75 |

4.93 |

4.27 |

3.49 |

3.02 |

2.70 |

2.47 |

2.28 |

2.14 |

2.01 |

1.91 |

1.74 |

1.61 |

1.51 |

1.42 |

1.35 |

| 6.0 |

14.72 |

7.36 |

5.37 |

4.65 |

3.80 |

3.29 |

2.94 |

2.69 |

2.49 |

2.33 |

2.19 |

2.08 |

1.90 |

1.76 |

1.65 |

1.55 |

1.47 |

| 7.0 |

15.81 |

7.91 |

5.77 |

5.00 |

4.08 |

3.54 |

3.16 |

2.89 |

2.67 |

2.50 |

2.36 |

2.24 |

2.04 |

1.89 |

1.77 |

1.67 |

1.58 |

| 8.0 |

16.81 |

8.41 |

6.14 |

5.32 |

4.34 |

3.76 |

3.36 |

3.07 |

2.84 |

2.66 |

2.51 |

2.38 |

2.17 |

2.01 |

1.88 |

1.77 |

1.68 |

| 9.0 |

17.74 |

8/87 |

6.48 |

5.61 |

4.58 |

3.97 |

3.55 |

3.24 |

3.00 |

2.80 |

2.64 |

2.51 |

2.29 |

2.12 |

1.98 |

1.87 |

1.77 |

| 10.0 |

18.59 |

9.30 |

6.79 |

5.88 |

4.80 |

4.16 |

3.72 |

3.39 |

3.14 |

2.94 |

2.77 |

2.63 |

2.40 |

2.22 |

2.08 |

1.96 |

1.86 |

| 15.0 |

22.13 |

11.07 |

8.08 |

7.00 |

5.71 |

4.95 |

4.43 |

4.04 |

3.74 |

3.50 |

3.30 |

3.13 |

2.26 |

2.65 |

2.47 |

2.33 |

2.12 |

| 20.0 |

24.79 |

12.40 |

9.05 |

7.84 |

6.40 |

5.54 |

4.96 |

4.53 |

4.19 |

3.92 |

3.70 |

3.51 |

3.20 |

2.96 |

2.77 |

2.61 |

2.48 |

| 25.0 |

26.84 |

13.42 |

9.80 |

8.49 |

6.93 |

6.00 |

5.37 |

4.90 |

4.54 |

4.24 |

4.00 |

3.80 |

3.46 |

3.21 |

3.00 |

2.83 |

2.68 |

| 30.0 |

28.40 |

14.20 |

10.37 |

8.98 |

7.33 |

6.35 |

5.68 |

5.19 |

4.80 |

4.49 |

4.23 |

4.02 |

3.67 |

3.39 |

3.18 |

2.99 |

2.84 |

| 35.0 |

29.56 |

14.78 |

10.79 |

9.35 |

7.63 |

6.61 |

5.91 |

5.40 |

5.00 |

4.67 |

4.41 |

4.18 |

3.82 |

3.56 |

3.31 |

3.12 |

2.96 |

| 40.0 |

30.36 |

15.18 |

11.09 |

9.60 |

7.84 |

6.79 |

6.07 |

5.54 |

5.13 |

4.80 |

4.53 |

4.29 |

3.92 |

3.63 |

3.39 |

3.20 |

3.04 |

| 45.0 |

30.83 |

15.42 |

11.26 |

9.75 |

6.89 |

6.89 |

6.17 |

5.63 |

5.21 |

4.88 |

4.60 |

4.36 |

3.98 |

3.69 |

3.45 |

3.25 |

3.08 |

| 50.0 |

30.99 |

15.50 |

11.32 |

9.80 |

8.00 |

6.93 |

6.20 |

5.66 |

5.24 |

4.90 |

4.62 |

4.38 |

4.00 |

3.70 |

3.46 |

3.27 |

3.10 |

References

- A. Lavopa and A. Szirmai, “Structural modernisation and development traps. An empirical approach,” World Dev., vol. 112, pp. 59–73, Dec. 2018. [CrossRef]

- Collective Monograph, ECONOMIC MODERNISATION: CHALLENGES, PROBLEMS, SOLUTIONS, vol. 568. 2020.

- M. R. BAIRAŠAUSKAITĖ Tamara, MEDIŠAUSKIENĖ Zita, “AR PAVYKO (PAVYKS) ATSKLEISTI MODERNĖJIMĄ LIETUVOS MODERNĖJIMO ISTORIJOJE?,” 2011.

- S. A. Martišius, “Ekonominių teorijų raida 1870-1970 metais,” Dev. Econ. Theor. 1870-1970, pp. 47–57, 2005.

- LIETUVOS RESPUBLIKOS VYRIAUSYBĖ, “NUTARIMAS DĖL 2021–2030 METŲ NACIONALINIO PAŽANGOS PLANO PATVIRTINIMO,” 2020. https://e-seimas.lrs.lt/portal/legalAct/lt/TAD/c1259440f7dd11eab72ddb4a109da1b5?jfwid=32wf90sn.

- E. Bivainis and T. Tamošiūnas, “Darnus regionų vystymasis: teorinis diskursas,” Ekon. ir Vadyb. Aktual. ir Perspekt., vol. 1, no. 8, pp. 30–36, 2007, [Online]. Available: http://www.su.lt/bylos/mokslo_leidiniai/ekonomika/7_8/bivainis.pdf.

- S. W. Yoon and D. K. Lee, “The development of the evaluation model of climate changes and air pollution for sustainability of cities in Korea,” Landsc. Urban Plan., vol. 63, no. 3, pp. 145–160, Apr. 2003. [CrossRef]

- R. Činčikaitė and N. Paliulis, “Assessing Competitiveness of Lithuanian Cities,” Econ. Manag., vol. 18, no. 3, pp. 490–500, 2013. [CrossRef]

- B. Melnikas, “DARNI PLĖTRA GLOBALIŲ TRANSFORMACIJŲ SĄLYGOMIS :,” pp. 4–26, 2011.

- A. Makštutis, D. Prakapienė, D. Dudzevičiūtė, and B. Melnikas, PLĖTROS OPTIMIZAVIMAS: Kolektyvinė monografija. 2016.

- Masser, “Managing our urban future: the role of remote sensing and geographic information systems,” Habitat Int., vol. 25, no. 4, pp. 503–512, Dec. 2001. [CrossRef]

- JTO, “Generalinė Asamblėja,” 2015.

- J. Cantwell, Innovation and Competitiveness. Oxford University Press, 2006.

- J. Clark and K. Guy, “Innovation and competitiveness: a review,” Technol. Anal. Strateg. Manag., vol. 10, no. 3, pp. 363–395, Jan. 1998. [CrossRef]

- L. M. Fonseca and V. M. Lima, “Countries three wise men: Sustainability, Innovation, and Competitiveness,” J. Ind. Eng. Manag., vol. 8, no. 4, Oct. 2015. [CrossRef]

- A. Ollo-López and M. E. Aramendía-Muneta, “ICT impact on competitiveness, innovation and environment,” Telemat. Informatics, vol. 29, no. 2, pp. 204–210, May 2012. [CrossRef]

- S. Şener and E. Sarıdoğan, “The Effects Of Science-Technology-Innovation On Competitiveness And Economic Growth,” Procedia - Soc. Behav. Sci., vol. 24, pp. 815–828, 2011. [CrossRef]

- A. Barrichello, R. S. Morano, P. R. Feldmann, and R. R. Jacomossi, “The importance of education in the context of innovation and competitiveness of nations,” Int. J. Educ. Econ. Dev., vol. 11, no. 2, p. 204, 2020. [CrossRef]

- S. L. Albrecht, A. B. Bakker, J. A. Gruman, W. H. Macey, and A. M. Saks, “Employee engagement, human resource management practices and competitive advantage,” J. Organ. Eff. People Perform., vol. 2, no. 1, pp. 7–35, Mar. 2015. [CrossRef]

- V. Kumar and A. Pansari, “Competitive Advantage through Engagement,” J. Mark. Res., vol. 53, no. 4, pp. 497–514, Aug. 2016. [CrossRef]

- N. Al Mehrzi and S. K. Singh, “Competing through employee engagement: a proposed framework,” Int. J. Product. Perform. Manag., vol. 65, no. 6, pp. 831–843, Jul. 2016. [CrossRef]

- B. N. Gerasimov, V. A. Vasyaycheva, and K. B. Gerasimov, “Identification of the factors of competitiveness of industrial company based on the module approach,” Entrep. Sustain. Issues, vol. 6, no. 2, pp. 677–691, Dec. 2018. [CrossRef]

- C.-D. Hategan, R.-I. Pitorac, V.-P. Hategan, and C. M. Imbrescu, “Opportunities and Challenges of Companies from the Romanian E-Commerce Market for Sustainable Competitiveness,” Sustainability, vol. 13, no. 23, p. 13358, Dec. 2021. [CrossRef]

- D. Kafetzopoulos, K. Gotzamani, and V. Gkana, “Relationship between quality management, innovation and competitiveness. Evidence from Greek companies,” J. Manuf. Technol. Manag., vol. 26, no. 8, pp. 1177–1200, Oct. 2015. [CrossRef]

- A. Pabedinskaitė and A. K. Renata Činčikaitė, “EVALUATION OF SMART CITIES,” Manag. engeneering’16, vol. 1, no. October, pp. 273–283, 2016.

- J. Bruneckienė and R. Činčikaitė, “Šalies Regionų Konkurencingumo Vertinimas Regionų Konkurencingumo Indeksu: Tikslumo Didinimo Aspektas,” Ekon. ir Vadyb., vol. 14, pp. 700–709, 2009.

- R. Činčikaitė and I. Meidute-Kavaliauskiene, “An Integrated Competitiveness Assessment of the Baltic Capitals Based on the Principles of Sustainable Development,” Sustainability, vol. 13, no. 7, p. 3764, Mar. 2021. [CrossRef]

- R. Činčikaitė and I. Meidute-Kavaliauskiene, “Assessment of Social Environment Competitiveness in Terms of Security in the Baltic Capitals,” Sustainability, vol. 13, no. 12, p. 6932, Jun. 2021. [CrossRef]

- J. Bruneckiene, A. Guzavicius, and R. Cincikaite, “Measurement of Urban Competitiveness in Lithuania,” vol. 21, no. 5, pp. 493–508, 2010.

- K. S. Momaya, S. Bhat, and L. Lalwani, “Institutional Growth and Industrial Competitiveness: Exploring the Role of Strategic Flexibility Taking the Case of Select Institutes in India,” Glob. J. Flex. Syst. Manag., vol. 18, no. 2, pp. 111–122, Jun. 2017. [CrossRef]

- S. Evans, M. A. Mehling, R. A. Ritz, and P. Sammon, “Border carbon adjustments and industrial competitiveness in a European Green Deal,” Clim. Policy, vol. 21, no. 3, pp. 307–317, Mar. 2021. [CrossRef]

- R. Vitkūnas, R. Činčikaitė, and I. Meidute-Kavaliauskiene, “Assessment of the Impact of Road Transport Change on the Security of the Urban Social Environment,” Sustainability, vol. 13, no. 22, p. 12630, Nov. 2021. [CrossRef]

- C. P. Ng, T. H. Law, F. M. Jakarni, and S. Kulanthayan, “Road infrastructure development and economic growth,” IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng., vol. 512, p. 012045, Apr. 2019. [CrossRef]

- Canning and E. Bennathan, “The Social Rate of Return on Infrastructure Investments,” World Bank Policy Res. Work. Pap., vol. 44, no. 4, pp. 348–361, 2000, [Online]. Available: http://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=630763.

- K. Gunasekera, W. Anderson, and T. R. Lakshmanan, “Highway-Induced Development: Evidence from Sri Lanka,” World Dev., vol. 36, no. 11, pp. 2371–2389, Nov. 2008. [CrossRef]

- Z. Xueliang, “Has Transport Infrastructure Promoted Regional Economic Growth?— With an Analysis of the Spatial Spillover Effects of Transport Infrastructure,” Soc. Sci. China, vol. 34, no. 2, pp. 24–47, May 2013. [CrossRef]

- K. Kazemzadeh and T. Koglin, “Electric bike (non)users’ health and comfort concerns pre and peri a world pandemic (COVID-19): A qualitative study,” J. Transp. Heal., vol. 20, p. 101014, Mar. 2021. [CrossRef]

- S. Schemme, R. C. Samsun, R. Peters, and D. Stolten, “Power-to-fuel as a key to sustainable transport systems – An analysis of diesel fuels produced from CO 2 and renewable electricity,” Fuel, vol. 205, pp. 198–221, Oct. 2017. [CrossRef]

- K. Monografija, VISUOMENĖS SAUGUMAS IR DARNI PLĖTRA: VISUOMENĖS SAUGUMO AKTUALIJOS IR PROBLEMINIAI KLAUSIMAI, vol. 5, no. 3. Kaunas, 2017.

- D. Generolo Jono Žemaičio Lietuvos karo akademija, Borisas Melnikas, Vladas Tumalavičius, Alvydas Šakočius, Mantas Bileišis, Svajūnė Ungurytė-Ragauskienė, Vidmantė Giedraitytė, Dalia Prakapienė, Jūratė Guščinskienė, Jadvyga Čiburienė, Gediminas Dubauskas, SAUGUMO IŠŠŪKIAI : SAUGUMO IŠŠŪKIAI : 2020.

- Lietuvos Bankas, “Lietuvos ekonomikos raida ir perspektyvos,” Eurosistema, pp. 1–5, 2020.

- “Jungtinių Tautų darnaus vystymosi darbotvarkės iki 2030 m. įgyvendinimo Lietuvoje ataskaita,” 2018.

- Byrne, B. M. Structural Equation Modeling with Amos: Basic Concepts, Applications, and Programming (2nd ed.). New York: Taylor and Francis Group, 2010.

- Schumacker, E., Lomax, G. A Beginner’s Guide to Structural Equation Modelling. 4th edtn, 2016.

- Little, Todd D., and David W. Slegers. "Factor analysis: Multiple groups." Encyclopedia of statistics in behavioral science, 2005.

- Woods, C.M.; Edwards, M.C. Factor Analysis and Related Methods. Essential Statistical Methods for Medical Statistics; Rao, C.R., Miller, J.P, B., Rao, D.C.; Elsevier: North-Holland, 2011; Volume 27, pp. 174–201.

- Hair Jr, J. F., Howard, M. C., & Nitzl, C. (2020). Assessing measurement model quality in PLS-SEM using confirmatory composite analysis. Journal of Business Research, 109, 101-110.

- DeVellis, R. Scale development: theory and applications: theory and application. Sage: Thousand Okas, CA, 2003.

- Streiner, D. Starting at the beginning: an introduction to coefficient alpha and internal consistency. Journal of personality assessment 2003, 80, 99–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hair, J.F., Hult, G.T.M., Ringle, C.M., Sarstedt, M., Danks, N.P., Ray, S. (2021). Evaluation of Reflective Measurement Models. In: Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM) Using R. Classroom Companion: Business. Springer, Cham. [CrossRef]

- Pituch, K. A., & Stevens, J. P. Applied Multivariate Statistics for the Social Sciences (6th ed.). New York: Routledge, 2016.

- Kline, R. B. Principles and practice of structural equation modeling (4th ed.). New York: The Guilford Press, 2016.

- Whittaker, T. A. Structural equation modeling. Applied Multivariate Statistics for the Social Sciences (6th ed.). Routledge: New York. 639-746, 2016.

- J. Imbrasaitė, “Politinis dalyvavimas ir socialinė aplinka Lietuvoje,” Sociol. Mintis ir veiksmas, vol. 10, pp. 81–89, 2002. [CrossRef]

- Navickienė, O.; Meidutė-Kavaliauskienė, I.; Činčikaitė, R.; Morkūnas, M.; Valackienė, A. Modernisation of the Country in the Context of Social Environmental Sustainability: Example of Lithuania. Preprints 2023.

- Häusermann, S. (2010). The politics of welfare state reform in continental Europe: Modernization in hard times. Cambridge University Press.

- Pelevin, S. I. (2019). Technogization of Society as a Factor of Socio-Cultural Modernization. Logos et Praxis, 18(4).

- Inglehart, R. (2020). Modernization and postmodernization: Cultural, economic, and political change in 43 societies. Princeton university press.

- Huntington, S. P. (2017). The change to change: modernization, development, and politics. In Analyzing the Third World (pp. 30-69). Routledge.

- Panda, S. (2018). Constraints faced by women entrepreneurs in developing countries: review and ranking. Gender in Management: An International Journal.

- Islam, N., Shkolnikov, V. M., Acosta, R. J., Klimkin, I., Kawachi, I., Irizarry, R. A., ... & Lacey, B. (2021). Excess deaths associated with covid-19 pandemic in 2020: age and sex disaggregated time series analysis in 29 high income countries. bmj, 373.

- Swami, V. (2015). Cultural influences on body size ideals: Unpacking the impact of Westernization and modernization. European Psychologist, 20(1), 44.

- Wiryomartono, B. (2022). Sustainability and the Built Environment: The Search for Ethics Based on Environmental Awareness and Social Responsibility. In Architectural Humanities in Progress (pp. 229-244). Springer, Cham.

- Crotty, J., & Hall, S. M. (2014). Environmental awareness and sustainable development in the Russian Federation. Sustainable Development, 22(5), 311-320.

- Xie, Y., & Peng, M. (2018). Attitudes toward homosexuality in China: Exploring the effects of religion, modernizing factors, and traditional culture. Journal of Homosexuality, 65(13), 1758-1787.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).