Submitted:

11 January 2023

Posted:

13 January 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

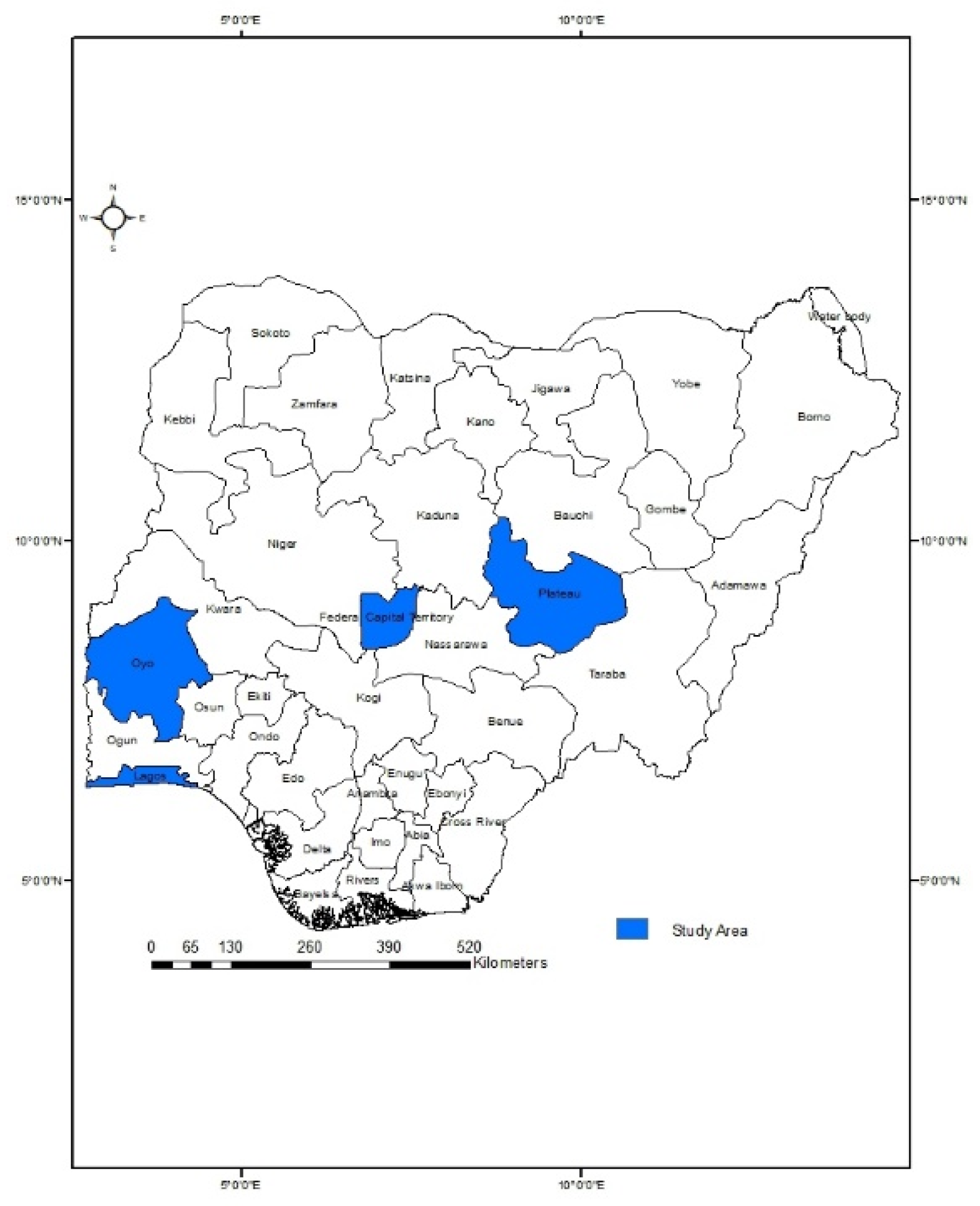

2. Materials and Methods

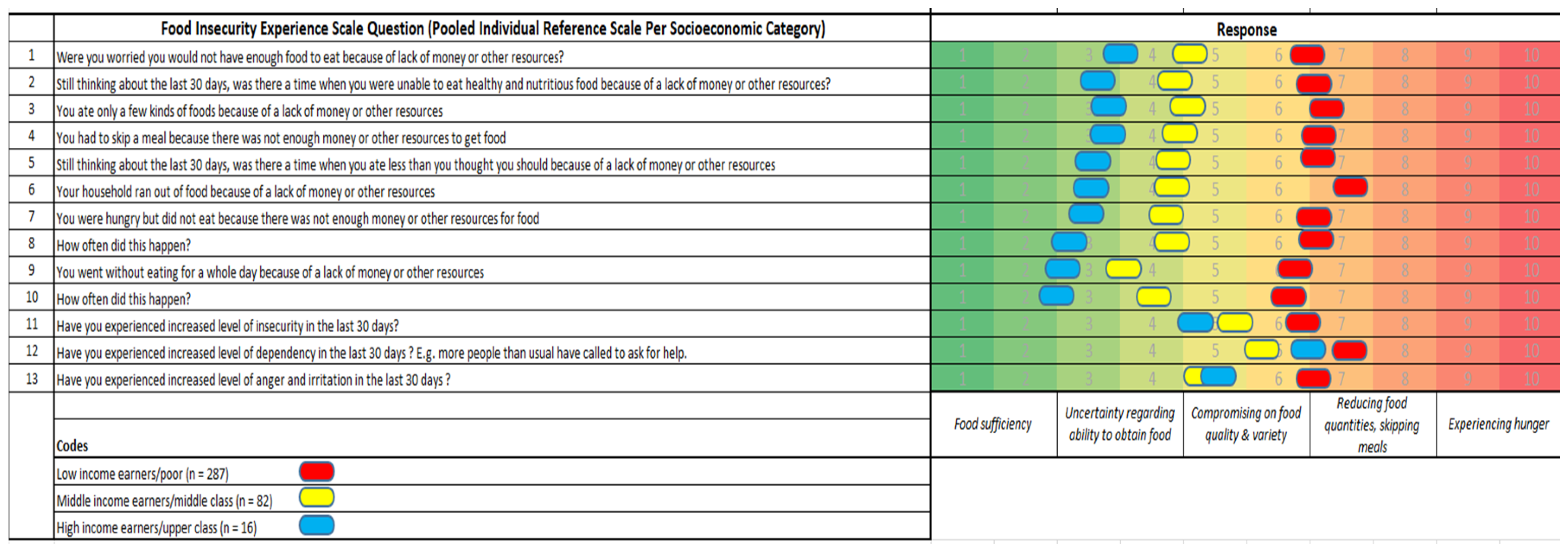

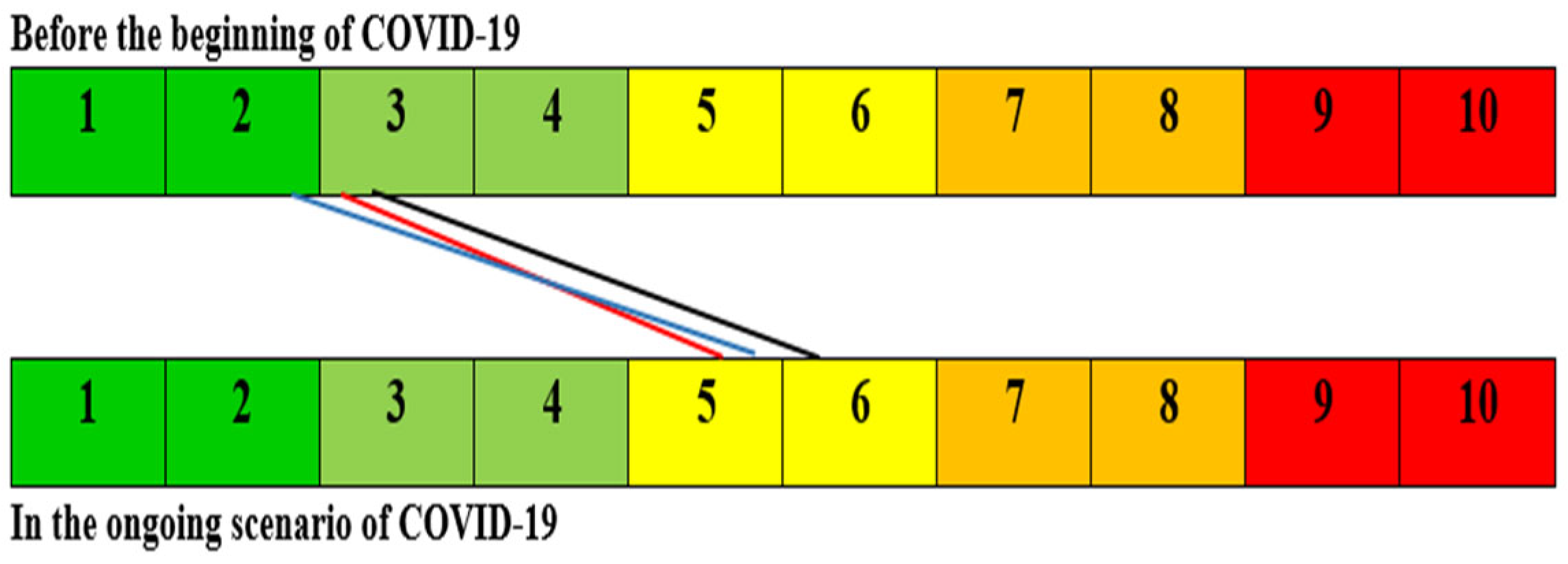

2.1. Questionnaire Design

2.2. Field Interview

2.3. Data Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

4.1. Study Limitations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Huang, C.; Wang, Y.; Li, X.; Ren, L.; Zhao, J.; Hu, Y.; et al. Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China. Lancet 2020; 395 (10223), 497 – 506. [CrossRef]

- Munster, V.J.; Koopmans, M.; van Doremalen, N.; van Riel, D.; de Wit, E. A Novel Coronavirus Emerging in China — Key Questions for Impact Assessment. N Engl J Med 2020; 382, 692 – 694. [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Guan, X.; Wu, P.; Wang, X.; Zhou, L.; Tong, Y.; et al. Early transmission dynamics in Wuhan, China, of novel coronavirus–infected pneumonia. N Engl J Med 2020; 382, 1199 – 1207. [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization (WHO). WHO Coronavirus (COVID-19) Dashboard, 2022. Available from: https://covid19.who.int/.

- Brooks, S.K.; Webster, R.K.; Smith, L.E.; Woodland, L.; Wessely, S.; Greenberg, N.; Rubin, G.J. The psychological impact of quarantine and how to reduce it: rapid review of the evidence. Lancet, 2020;395 (10227), 912-920. [CrossRef]

- International Labour Organization (ILO). COVID-19 and the world of work: Sectoral impact, responses and recommendations, 2020. Available from: https://www.ilo.org/global/topics/coronavirus/sectoral/lang--en/index.htm.

- Otekunrin, O.A.; Otekunrin, O.A. Healthy and Sustainable Diets: Implications for Achieving SDG2. In Zero Hunger. Encyclopedia of the UN Sustainable Development Goals; Leal FW, Azul A, Brandli OP,Wall T. Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2021.

- FAO, IFAD, UNICEF, WFP, WHO. The State of Food Security and Nutrition in the World 2021. In Transforming Food Systems for Food Security, Improved Nutrition and Affordable Healthy Diets for All; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2021.

- FAO, IFAD, UNICEF, WFP, WHO. The State of Food Security and Nutrition in the World 2022. Repurposing food and agricultural policies to make healthy diets more affordable. Rome, FAO.

- Otekunrin, O.A.; Otekunrin, O.A. Nutrition outcomes of under-five children of smallholder farm households: Do higher commercialization levels lead to better nutritional status? Child Ind Res, 2022; 15(6), 2309-2334. [CrossRef]

- World Data Lab. 2021. Available from: https://worldpoverty.io/headline (accessed on 12 October 2021).

- Otekunrin, O.A.; Otekunrin, OA; Sawicka, B.; Pszczółkowski, P. Assessing Food Insecurity and Its Drivers among Smallholder Farming Households in Rural Oyo State, Nigeria: The HFIAS Approach. Agriculture, 2021a; 11, 1-20. [CrossRef]

- Andam, K.; Edeh, H.; Oboh, V.; Pauw, K. Impacts of COVID-19 on food systems and poverty in Nigeria. Adv Food Sec Sustainability, 2020; 5, 145-173. [CrossRef]

- Otekunrin, O.A.; Otekunrin, O.A.; Fasina, F.O.; Omotayo, A.O.; Akram, M. Assessing the Zero Hunger Readiness in Africa in the Face of COVID-19 Pandemic. Caraka Tani J Sustain Agric, 2020; 35, 213–227. [CrossRef]

- Inegbedion, H.E. COVID-19 lockdown: implication for food security. J Agribus Dev Emerg Economies, 2020; 11(5): 437-451. [CrossRef]

- Ibukun, C.O, Adebayo AA. Household food security and the COVID-19 in Nigeria. African Dev Review, 2021; 33 (S1): 575-587. [CrossRef]

- Otekunrin O.A.; Fasina, F.O.; Omotayo, O.A, Otekunrin OA.; Akram, M. COVID-19 in Nigeria: Why continuous spike in cases? Asian Pac. J. Trop. Med, 2021b; 14, 1–4. [CrossRef]

- Balana, B.B.; Ogunniyi, A.; Oyeyemi, M.; Fasoranti, A.; Edeh, H.; Andam, K. COVID-19, food insecurity and dietary diversity of households: Survey evidence from Nigeria. Food Security, 2022; 1-23. [CrossRef]

- The World Bank. World Bank Country and Lending Groups – Country Classification, 2022. Available from: https://datahelpdesk.worldbank.org/knowledgebase/articles/906519-world-bank-country-and-lending-groups.

- FAO’s Food Insecurity Experience Scale (FIES), 2021. Available from: http://www.fao.org/3/a-bl354e.pdf.

- FAO. FAO's support to mitigate impact of COVID-19 on food and agriculture in Asia and the Pacific (Version 2.0), internal report, 2020.

- Van Hoof, E. Lockdown is the world's biggest psychological experiment - and we will pay the price. World Economic Forum (WE Forum) Global Agenda (Global Health), 2020. Available from: https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2020/04/this-is-the-psychological-side-of-the-covid-19-pandemic-that-were-ignoring/. Accessed 14 April 2020.

- Piolanti, A.; Offidani, E, Guidi, J.; Gostoli, S.; Fava, G.A.; Sonino, N. Use of the psychosocial index: A sensitive tool in research and practice. Psychotherapy & Psychosomatics, 2016;85:337–345. [CrossRef]

- Odetokun, I.A.; Akpabio, U.; Alhaji, N.B.; Biobaku, K.T.; Oloso, N.O.; Ghali-Mohammed I et al. Knowledge of antimicrobial resistance among veterinary students and their personal antibiotic use practices: A national cross-sectional survey. Antibiotics, 2019; 8(4): 1-15. [CrossRef]

- Hager, E.; Odetokun, I.A.; Bolarinwa, O.; Zainab, A.; Okechukwu, O.; Al-Mustapha, AI. Knowledge, attitude, and perceptions towards the 2019 coronavirus pandemic: a bi-national survey in Africa. PLoS One, 2020; 29; 15(7): e0236918. [CrossRef]

- Odetokun, IA.; Alhaji, N.B.; Akpabio, U.; Abdulkareem, M.A.; Bilat, G.T.; Subedi, D.; Ghali-Mohammed, I.; Elelu, N. Knowledge, risk perception, and prevention preparedness towards COVID-19 among a cross-section of animal health professionals in Nigeria. Pan African Medical Journal, 2022; 41(20). 1-17. [CrossRef]

- Odetokun IA, Al-Mustapha AI, Elnadi H, Subedi D, Ogundijo OA, Oyewo M. The COVID-19 pandemic: A multi-regional cross-sectional survey of public knowledge, attitudes, and perceptions. PLOS Glob Public Health, 2022;2(7):e0000737. [CrossRef]

- Dean, A.G.; Sullivan, K.M.; Soe, M.M.; OpenEpi: Open Source Epidemiologic Statistics for Public Health, Version. Available from: www.OpenEpi.com, updated 2013/04/06.

- Anon. GraphPad QuickCalcs®. Available from: https://www.graphpad.com/quickcalcs/.

- Pickett, K.E.; Wilkinson, R.G. Income inequality and health: a causal review. Soc Sci Med. 2015; 128:316-26. [CrossRef]

- Okpani, A.I.; Abimbola, S. Operationalizing universal health coverage in Nigeria through social health insurance. Nigerian Med J, 2015; 56(5), 305–310. [CrossRef]

- Adeniji, F. Burden of out-of-pocket payments among patients with cardiovascular disease in public and private hospitals in Ibadan, South West, Nigeria: a cross-sectional study. BMJ Open, 2021; 11: e044044. [CrossRef]

- Amu H, Dickson KS, Kumi-Kyereme A, Darteh EKM (2018) Understanding variations in health insurance coverage in Ghana, Kenya, Nigeria, and Tanzania: Evidence from demographic and health surveys. PLoS ONE 13(8): e0201833. [CrossRef]

- Alam K, Mahal A. Economic impacts of health shocks on households in low and middle income countries: a review of the literature. Global Health, 2014;10, 21. [CrossRef]

- Barasa E, Kairu A, Ng'ang'a W, Maritim M, Were V, Akech S, Mwangangi M. Examining unit costs for COVID-19 case management in Kenya. BMJ Global Health 2021; 6: e004159. [CrossRef]

- Gelburd R. Profiles of COVID-19 Patients: A Study of Private Health Care Claims. Available from: https://www.ajmc.com/view/profiles-of-covid19-patients-a-study-of-private-health-care-claims.

- Muanya C, Salau G, Osakwe F. COVID-19: Cost of treatment above N100, 000 per patient as cases climb to 4, 000. Available from: https://guardian.ng/news/covid-19-cost-of-treatment-above-n100-000-per-patient-as-cases-climb-to-4-000/.

- Keshinro, S.O.; Awolola, N.A.; Adebayo, L.A.; Mutiu, W.B.; Saka, B.A.; Abdus-Salam, I.A. Full autopsy in a confirmed COVID-19 patient in Lagos, Nigeria - A case report. Human pathology (New York), 2021; 24, 200524. [CrossRef]

- Olwande, J.; Njagi, T.; Ayieko, M.; Maredia, M.K.; Tschirley, D. Urban and rural areas have seen similar impacts from COVID-19 in Kenya: Policy Research Note #2, 2021. Available from: https://www.canr.msu.edu/prci/publications/Policy-Research-Notes/PRCI_PRN_2_Urban%20and%20Rural%20Areas%20Have%20Seen%20Similar%20Impacts%20From%20COVID-19%20in%20Kenya.pdf.

- Otekunrin, O.A.; Ayinde, I.A.; Momoh, S.; Otekunrin, O.A. How far has Africa gone in achieving the Zero Hunger Target? Evidence from Nigeria. Glob Food Secur, 2019; 22, 1-12. [CrossRef]

- Otekunrin, O.A. Investigating food insecurity, health and environment-related factors, and agricultural commercialization in Southwestern Nigeria: evidence from smallholder farming households. Environmental Science and Pollution Research, 2022; 29 (34), 51469-51488. [CrossRef]

- Anon. United States: Pandemic Impact on People in Poverty – Current System Leaves Needs Unmet; Lasting Reforms Needed, 2021. Available from: https://www.hrw.org/news/2021/03/02/united-states-pandemic-impact-people-poverty.

- Eranga, I.O. COVID-19 Pandemic in Nigeria: Palliative Measures and the Politics of Vulnerability. Int J MCH and AIDS, 2020; 9(2), 220–222. [CrossRef]

- Amzat, J.; Aminu, K.; Kolo, V.I.; Akinyele, A.A.; Ogundairo, J.A.; Danjibo, M.C. Coronavirus outbreak in Nigeria: Burden and socio-medical response during the first 100 days. Int J Infect Dis, 2020; 98, 218–224. [CrossRef]

- Demirgüç-Kunt, A.; Klapper, L.F.; Prasad, N. Measuring the Effectiveness of Service Delivery: Delivery of Government Provided Goods and Services in India (September 27, 2017). World Bank Policy Research Working Paper No. 8207, Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3044151.

- Giusti, E.M.; Pedroli, E.; D'Aniello, G.E.; Stramba Badiale, C.; Pietrabissa, G.; Manna, C.; et al. The Psychological Impact of the COVID-19 Outbreak on Health Professionals: A Cross-Sectional Study. Front Psychol, 2020; 11:1684. [CrossRef]

- aved, B.; Sarwer, A.; Soto, E.B.; Mashwani, Z.U. The coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic's impact on mental health. Int J Health Plan Mgmt, 2020; 35(5), 993–996. [CrossRef]

- Uphoff, EP.;Lombardo, C.; Johnston, G.; Weeks, L.; Rodgers, M.; Dawson, S.; et al. Mental health among healthcare workers and other vulnerable groups during the COVID-19 pandemic and other coronavirus outbreaks: A rapid systematic review. PLoS ONE, 2021; 16(8): e0254821. [CrossRef]

- Bareeqa, S.B.; Ahmed, S.I.; Samar, S.S.; Yasin, W.; Zehra. S.; Monese, G.M.; Gouthro, R.V. Prevalence of depression, anxiety and stress in china during COVID-19 pandemic: A systematic review with meta-analysis. Int J Psychiatry Med, 2021; 56(4):210-227. [CrossRef]

- Oyewunmi, A.E.; Oyewunmi, O.A.; Iyiola, O.O.; Ojo, A.Y. Mental health and the Nigerian workplace: Fallacies, facts and the way forward. Int J Psychol Counsel, 2015; 7(7), 106-111. [CrossRef]

- Rudenstine, S.; McNeal, K.; Schulder, T.; Ettman, C.K., Hernandez, M.; Gvozdieva, K.; Galea, S. Depression and Anxiety during the COVID-19 Pandemic in an Urban, Low-Income Public University Sample. J Trauma Stress, 2021; 34(1):12-22. [CrossRef]

| Variable (n) | Classification | Number (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Marital status* (412) | Single | 132 (32.04) |

| Married | 255 (61.89) | |

| Separated/Divorced | 6 (1.46) | |

| Widowed | 18 (4.37) | |

| Total number of persons in the household (405) | 1 – 4 | 190 (46.91) |

| 5 – 8 | 187 (46.17) | |

| 9 – 12 | 23 (5.68) | |

| > 12 | 5 (1.23) | |

| Age (411) | ≤ 20 years | 7 (1.70) |

| 21 – 30 years | 105 (25.55) | |

| 31 – 40 years | 151 (36.74) | |

| 41 – 50 years | 104 (25.30) | |

| > 50 years | 44 (10.71) | |

| Gender (411) | Male | 239 (58.15) |

| Female | 172 (41.85) | |

| Level of education of household head (358) | ≤ primary | 25 (6.99) |

| Secondary | 69 (19.27) | |

| Diploma – first degree | 193 (53.91) | |

| MSc and PhD | 71 (19.83) | |

| Work hours per day (382) | 2 – 6 hours | 24 (6.28) |

| 7 – 9 hours | 205 (53.66) | |

| 10 – 12 hours | 62 (16.23) | |

| > 12 hours | 91 (23.82) | |

| ∞Family income based on society class (411) | Low | 295 (71.78) |

| Medium | 97 (23.60) | |

| High | 19 (4.62) | |

| Previously hospitalized for severe illness/surgery (405) | Yes# | 61 (15.06) |

| No | 344 (84.94) | |

| Allergic to medication** (401) | Yes | 42 (10.47) |

| No | 359 (89.53) | |

| Drink alcohol routinely or periodically (410) | Yes | 44 (10.73) |

| No | 366 (89.27) | |

| Smoke routinely or periodically (410) | Yes | 18 (4.39) |

| No | 392 (95.61) | |

| Take recreational drugs routinely or periodically (410) | Yes | 12 (2.93) |

| No | 398 (97.07) | |

| Drink coffee and tea regularly (410) | Yes | 311 (75.85) |

| No | 99 (24.15) |

| Variable (n) | Classification | Number (%) | Unsatisfactoryexperience | Satisfactory experience | p value (χ2) | OR | 95% CI | p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Marital status* (412) | Single | 132 (32.04) | 72 | 60 | 0.669 | - | - | - |

| Married | 255 (61.89) | 127 | 128 | - | - | - | ||

| Separated/Divorced | 6 (1.46) | 4 | 2 | - | - | - | ||

| Widowed | 18 (4.37) | 10 | 8 | - | - | - | ||

| Total number of persons in the household (405) | 1 – 4 | 190 (46.91) | 107 | 83 | 0.158 | - | - | - |

| 5 – 8 | 187 (46.17) | 90 | 97 | - | - | - | ||

| 9 – 12 | 23 (5.68) | 10 | 13 | - | - | - | ||

| > 12 | 5 (1.23) | 1 | 4 | - | - | - | ||

| Age (411) | ≤ 20 years | 7 (1.70) | 4 | 3 | 0.991 | - | - | - |

| 21 – 30 years | 105 (25.55) | 56 | 49 | - | - | - | ||

| 31 – 40 years | 151 (36.74) | 77 | 74 | - | - | - | ||

| 41 – 50 years | 104 (25.30) | 54 | 50 | - | - | - | ||

| > 50 years | 44 (10.71) | 22 | 22 | - | - | - | ||

| Gender (411) | Male | 239 (58.15) | 111 | 128 | 0.012α | 1.00 | - | - |

| Female | 172 (41.85) | 102 | 70 | 0.59 | 0.40, 0.88 | 0.013α | ||

| Level of education of household head (358) | ≤ primary | 25 (6.99) | 20 | 5 | 0.000α | 1.00 | - | - |

| Secondary | 69 (19.27) | 54 | 15 | 1.11 | 0.36, 3.46 | >0.999 | ||

| Diploma – first degree | 193 (53.91) | 85 | 108 | 5.08 | 1.83, 14.1 | 0.001α | ||

| MSc and PhD | 71 (19.83) | 21 | 50 | 9.52 | 3.16, 28.74 | <0.001α | ||

| Work hours per day (382) | 2 – 6 hours | 24 (6.28) | 16 | 8 | 0.006α | 1.00 | - | - |

| 7 – 9 hours | 205 (53.66) | 112 | 93 | 1.66 | 0.68, 4.05 | 0.366 | ||

| 10 – 12 hours | 62 (16.23) | 38 | 24 | 1.26 | 0.47, 3.40 | 0.838 | ||

| > 12 hours | 91 (23.82) | 34 | 57 | 3.35 | 1.29, 8.66 | 0.019α | ||

| ∞Family income based on society class (411) | Low | 295 (71.78) | 185 | 110 | 0.000α | 1.00 | - | - |

| Medium | 97 (23.60) | 27 | 70 | 4.36 | 2.64, 7.21 | <0.001α | ||

| High | 19 (4.62) | 1 | 18 | 30.27 | 3.99, 229.90 | <0.001α | ||

| Previously hospitalized for severe illness/surgery (405) | Yes# | 61 (15.06) | 179 | 165 | 0.579 | - | - | - |

| No | 344 (84.94) | 29 | 32 | - | - | - | ||

| Allergic to medication** (401) | Yes | 42 (10.47) | 25 | 17 | 0.330 | - | - | - |

| No | 359 (89.53) | 183 | 176 | - | - | - | ||

| Drink alcohol routinely or periodically (410) | Yes | 44 (10.73) | 26 | 18 | 0.341 | - | - | - |

| No | 366 (89.27) | 187 | 179 | - | - | - | ||

| Smoke routinely or periodically (410) | Yes | 18 (4.39) | 9 | 9 | 1.000 | - | - | - |

| No | 392 (95.61) | 204 | 188 | - | - | - | ||

| Take recreational drugs routinely or periodically (410) | Yes | 12 (2.93) | 8 | 4 | 0.385 | - | - | - |

| No | 398 (97.07) | 205 | 193 | - | - | - | ||

| Drink coffee and tea regularly (410) | Yes | 311 (75.85) | 154 | 157 | 0.084 | - | - | - |

| No | 99 (24.15) | 59 | 40 | - | - | - |

| Variable (n) | Yes (%) | No (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Selected experience | ||

| Death of a family member (407) | 20 (4.91) | 387 (95.09) |

| Separation from spouse or long-term relationship (407) | 41 (10.07) | 366 (89.93) |

| Recent change of job/loss of job (407) | 47 (11.55) | 360 (88.45) |

| Financial difficulties (408) | 177 (43.38) | 231 (56.62) |

| Movement/change of location within the same city (311) | 55 (17.68) | 256 (82.32) |

| Movement to another city (407)) | 44 (10.81) | 363 (89.19) |

| Legal problem (407) | 17 (4.18) | 390 (95.82) |

| Begin a new relationship (409) | 59 (14.43) | 350 (85.57) |

| Well-being | ||

| Satisfaction with job (384) | 231 (60.16) | 153 (39.84) |

| Felt more under pressure at work (382) | 99 (25.91) | 283 (74.08) |

| Have more problem with colleagues at work (378) | 38 (10.05) | 340 (89.95) |

| Retired person or student (349) | 49 (14.04) | 300 (85.96) |

| Felt under pressure during the day (352) | 48 (13.64) | 304 (86.36) |

| Unable to find a job due to COVID-19 (355) | 34 (9.58) | 321 (90.42) |

| Have serious arguments with close relatives (358) | 36 (10.06) | 322 (89.94) |

| Have serious arguments with other people (261) | 23 (8.81) | 238 (91.19) |

| Close relatives been seriously ill due to COVID-19 (363) | 27 (7.44) | 336 (92.56) |

| Felt tension at home (365) | 61 (16.71) | 304 (83.29) |

| Live by oneself (367) | 75 (20.44) | 292 (79.56) |

| Felt lonely (369) | 55 (14.91) | 314 (85.09) |

| Variable (n) | Income category | Not at all (%) | Only a little (%) | Somewhat much (%) | A great deal (%) |

| It takes a long time to fall asleep | Low (294) | 159 (54.08) | 77 (26.19) | 47 (15.99) | 11 (3.74) |

| Medium (96) | 62 (64.58) | 21 (21.88) | 9 (9.38) | 4 (4.17) | |

| High (19) | 12 (63.16) | 4 (21.05) | 3 (15.79) | 0 (0.00) | |

| Restless sleep | Low (294) | 152 (51.70) | 77 (26.19) | 53 (18.03) | 12 (4.08) |

| Medium (96) | 64 (66.67) | 26 (27.08) | 3 (3.13) | 3 (3.13) | |

| High (19) | 16 (84.21) | 2 (10.53) | 0 (0.00) | 1 (5.26) | |

| Waking too early and not being able to fall asleep again | Low (294) | 146 (49.66) | 83 (28.23) | 42 (14.29) | 23 (7.82) |

| Medium (96) | 54 (56.25) | 27 (28.13) | 7 (7.29) | 8 (8.33) | |

| High (19) | 15 (78.95) | 1 (5.26) | 1 (5.26) | 2 (10.53) | |

| Feeling tired on waking up | Low (294) | 168 (57.14) | 81 (27.55) | 33 (11.22) | 12 (4.08) |

| Medium (96) | 45 (46.88) | 40 (41.67) | 8 (8.33) | 3 (3.13) | |

| High (19) | 16 (84.21) | 0 (0.00) | 2 (10.53) | 1 (5.26) | |

| Chest, stomach or abdominal pain | Low (294) | 220 (74.83) | 54 (18.37) | 17 (5.78) | 3 (1.02) |

| Medium (96) | 81 (84.38) | 11 (11.46) | 3 (3.13) | 1 (1.04) | |

| High (19) | 18 (94.74) | 1 (5.26) | 0 (0.00) | 0 (0.00) | |

| Heart beating quickly or strongly (palpitation) without a reason like exercise | Low (294) | 243 (82.65) | 36 (12.24) | 13 (4.42) | 2 (0.68) |

| Medium (96) | 78 (81.25) | 10 (10.42) | 5 (5.21) | 3 (3.13) | |

| High (19) | 15 (78.95) | 3 (15.79) | 0 (0.00) | 1 (5.26) | |

| Feeling dizzy or like fainting | Low (293) | 240 (81.91) | 36 (12.29) | 16 (5.46) | 1 (0.34) |

| Medium (95) | 86 (90.53) | 6 (6.32) | 2 (2.11) | 1 (1.05) | |

| High (19) | 15 (78.95) | 2 (10.53) | 2 (10.53) | 0 (0.00) | |

| Feeling pressure or tightness in the head or body | Low (292) | 215 (73.63) | 61 (20.89) | 13 (4.45) | 3 (1.03) |

| Medium (96) | 75 (78.13) | 16 (16.67) | 4 (4.17) | 1 (1.04) | |

| High (19) | 16 (84.21) | 1 (5.26) | 0 (0.00) | 2 (10.53) | |

| Breathing difficulties or feeling of not having enough air | Low (292) | 243 (83.22) | 29 (9.93) | 17 (5.82) | 3 (1.03) |

| Medium (96) | 83 (86.65) | 8 (8.33) | 5 (5.21) | 0 (0.00) | |

| High (19) | 16 (84.21) | 2 (10.53) | 0 (0.00) | 1 (5.26) | |

| Feeling tired or lack of energy | Low (294) | 190 (64.63) | 55 (18.71) | 28 (9.52) | 21 (7.14) |

| Medium (96) | 61 (63.54) | 26 (27.08) | 7 (7.29) | 2 (2.08) | |

| High (19) | 16 (84.21) | 2 (10.53) | 1 (5.26) | 0 (0.00) | |

| Irritable | Low (294) | 192 (65.31) | 73 (24.83) | 24 (8.16) | 5 (1.70) |

| Medium (96) | 73 (76.04) | 16 (16.67) | 7 (7.29) | 0 (0.00) | |

| High (19) | 14 (73.70) | 4 (21.05) | 0 (0.00) | 1 (5.26) | |

| Sad or depressed | Low (293) | 175 (59.73) | 87 (29.69) | 21 (7.17) | 10 (3.41) |

| Medium (96) | 65 (67.71) | 23 (23.96) | 5 (5.21) | 3 (3.13) | |

| High (19) | 14 (73.70) | 3 (15.79) | 2 (10.52) | 0 (0.00) | |

| Feeling tensed or ‘wound up’ | Low (293) | 188 (63.95) | 56 (19.05) | 41 (13.95) | 8 (13.95) |

| Medium (97) | 67 (69.07) | 21 (21.65) | 7 (7.22) | 2 (2.06) | |

| High (19) | 16 (84.21) | 2 (10.52) | 0 (0.00) | 1 (5.26) | |

| Lost interest in most things | Low (293) | 201 (68.60) | 60 (20.48) | 22 (7.51) | 10 (3.41) |

| Medium (97) | 67 (69.07) | 21 (21.65) | 6 (6.19) | 3 (3.09) | |

| High (19) | 16 (84.21) | 2 (10.52) | 1 (5.26) | 0 (0.00) | |

| Attack or panic | Low (294) | 232 (78.91) | 38 (12.92) | 22 (7.48) | 2 (0.68) |

| Medium (97) | 85 (87.63) | 8 (8.25) | 4 (4.12) | 0 (0.00) | |

| High (19) | 18 (94.73) | 1 (5.26) | 0 (0.00) | 0 (0.00) | |

| Perception of having a physical COVID-19 related problem wrongly diagnosed | Low (293) | 256 (87.37) | 27 (9.21) | 9 (3.07) | 1 (0.34) |

| Medium (97) | 88 (90.72) | 7 (7.22) | 2 (2.06) | 0 (0.00) | |

| High (19) | 19 (100.00) | 0 (0.00) | 0 (0.00) | 0 (0.00) | |

| After reading or hearing about COVID-19, feeling of having similar symptoms | Low (293) | 251 (85.67) | 22 (7.50) | 19 (6.48) | 1 (0.34) |

| Medium (97) | 83 (85.57) | 10 (10.31) | 2 (2.06) | 2 (2.06) | |

| High (19) | 18 (94.73) | 1 (5.26) | 0 (0.00) | 0 (0.00) | |

| When I noticed a sensation in your nose, nostrils, trachea or chest, or I coughed, I find it difficult to think of something else | Low (293) | 240 (81.91) | 31(10.58) | 13 (4.44) | 9 (3.07) |

| Medium (97) | 75 (77.32) | 13 (13.40) | 4 (4.12) | 5 (5.15) | |

| High (19) | 15 (78.95) | 2 (10.52) | 1 (5.26) | 1 (5.26) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).