Submitted:

19 January 2023

Posted:

20 January 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

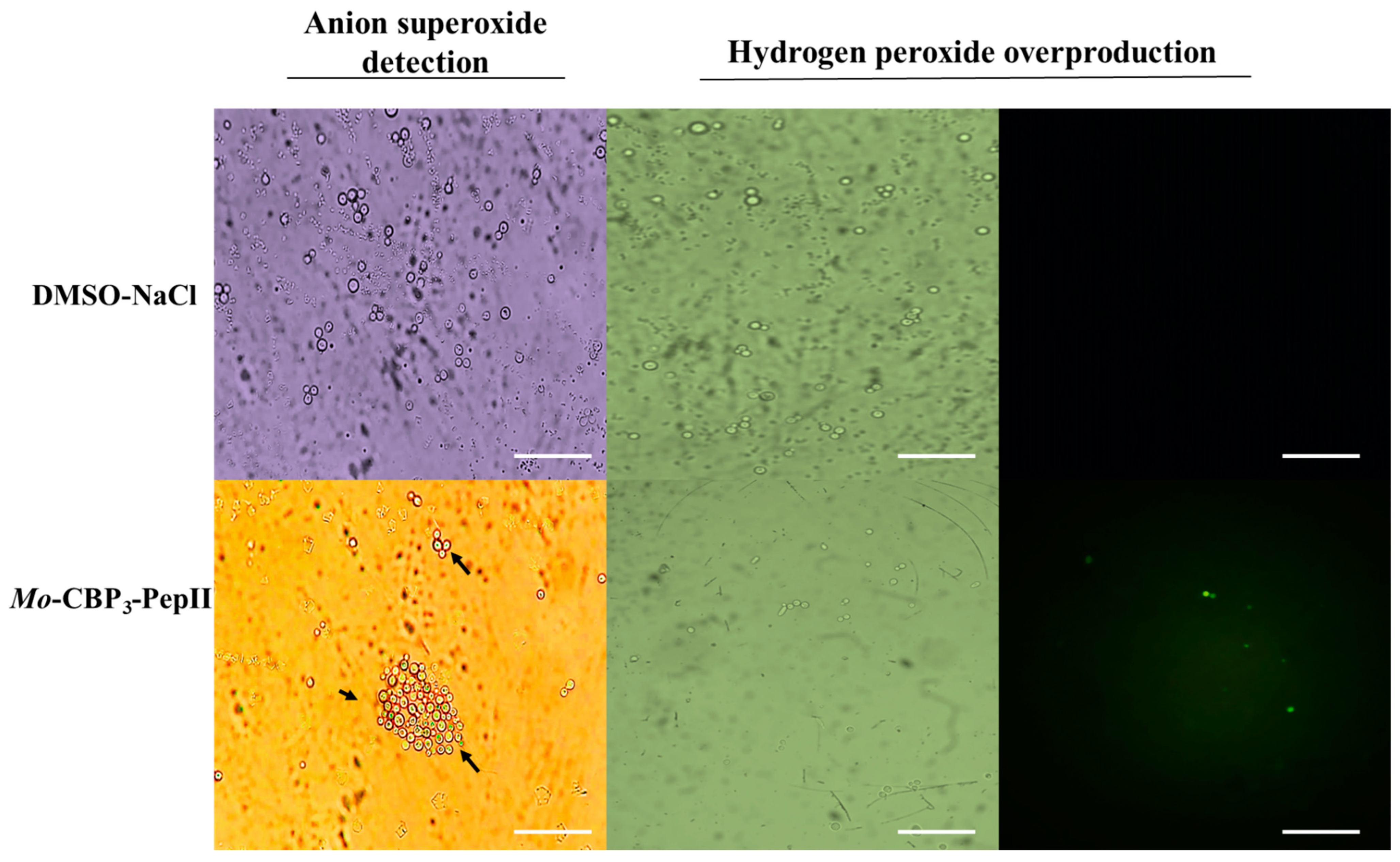

2.1. Mo-CBP3-PepII Induced ROS Overaccumulation in C. neoformans Cells

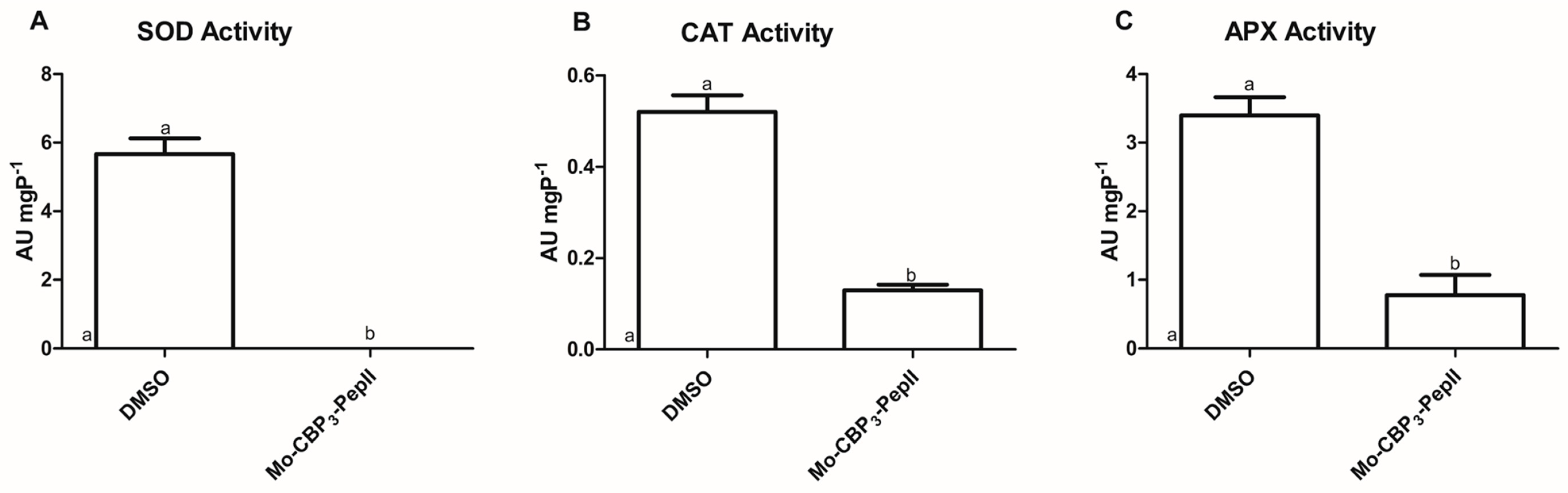

2.2. Mo-CBP3-PepII Affects the Activity of Redox System Enzymes

2.3. Ascorbic Acid (AsA) Affects the Anticryptococcal Potential of Mo-CBP3-PepI

2.4. Mo-CBP3-PepII Interferes in the Biosynthesis of Ergosterol

2.5. Energetic Metabolism is Affected in C. neoformans Treated with Mo-CBP3-PepII

2.6. Mo-CBP3-PepII Promotes Several Changes in the Cell Structure of C. neoformans

2.7. Proteomic Profile of C. neoformans Treated with Mo-CBP3-PepII

2.7.1. Overview

2.7.2. DNA and RNA Binding Proteins

2.7.3. Ligase- and Amino Acid Metabolism-Related Proteins

2.7.4. Oxidoreductase-Related Proteins

2.7.5. Protein Binding-Related Proteins

2.7.6. Transferase-Related Proteins

2.7.7. Transport or Structural Activity-Related Proteins

2.7.8. Energetic Metabolism-Related Proteins

2.7.9. Pathogenicity-Related Proteins

3. Conclusion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Fungal Strains, Chemicals, and Synthetic Peptides

4.2. Antifungal Assay

4.3. Detection of Mo-CBP3-PepII-Induced Overproduction of ROS

4.4. Protein Extraction from C. neoformans Cells

4.5. Activity Redox System Enzymes

4.5.1. Ascorbate Peroxidase (APX) Activity

4.5.2. Catalase (CAT) Activity

4.5.3. Superoxide Dismutase (SOD) Activity

4.6. Ergosterol Inhibition Synthesis

4.7. Lactate Dehydrogenase (LDH) Activity

4.8. Cytochrome C Release

4.9. Atomic Force Microscopy (AFM)

4.10. Gel-Free Proteomic Analysis

4.11. Protein Identification

4.12. Statistical Analysis

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Seiler, G.T.; Ostrosky-Zeichner, L. Investigational Agents for the Treatment of Resistant Yeasts and Molds. Curr. Fungal Infect. Rep. 2021, 15, 104–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stewart, A.G.; Paterson, D.L. How Urgent Is the Need for New Antifungals? Expert Opin. Pharmacother. 2021, 22, 1857–1870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Organization, W.H. WHO Fungal Priority Pathogens List to Guide Research, Development and Public Health Action 2022, 1–48.

- Woo, Y.H.; Martinez, L.R. Cryptococcus Neoformans –Astrocyte Interactions: Effect on Fungal Blood Brain Barrier Disruption, Brain Invasion, and Meningitis Progression. Crit. Rev. Microbiol. 2021, 47, 206–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coelho, C.; Casadevall, A. Cryptococcal Therapies and Drug Targets: The Old, the New and the Promising. Cell. Microbiol. 2016, 18, 792–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maligie, M.A.; Selitrennikoff, C.P. Cryptococcus Neoformans Resistance to Echinocandins: (1,3)β-Glucan Synthase Activity Is Sensitive to Echinocandins. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2005, 49, 2851–2856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souza, P.F.N.; Marques, L.S.M.; Oliveira, J.T.A.; Lima, P.G.; Dias, L.P.; Neto, N.A.S.; Lopes, F.E.S.; Sousa, J.S.; Silva, A.F.B.; Caneiro, R.F.; et al. Synthetic Antimicrobial Peptides: From Choice of the Best Sequences to Action Mechanisms. Biochimie 2020, 175, 132–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Erak, M.; Bellmann-Sickert, K.; Els-Heindl, S.; Beck-Sickinger, A.G. Peptide Chemistry Toolbox – Transforming Natural Peptides into Peptide Therapeutics. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2018, 26, 2759–2765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kundu, R. Cationic Amphiphilic Peptides: Synthetic Antimicrobial Agents Inspired by Nature. ChemMedChem 2020, 15, 1887–1896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguiar, T.K.B.; Neto, N.A.S.; Freitas, C.D.T.; Silva, A.F.B.; Bezerra, L.P.; Malveira, E.A.; Branco, L.A.C.; Mesquita, F.P.; Goldman, G.H.; Alencar, L.M.R.; et al. Antifungal Potential of Synthetic Peptides against Cryptococcus Neoformans: Mechanism of Action Studies Reveal Synthetic Peptides Induce Membrane–Pore Formation, DNA Degradation, and Apoptosis. Pharmaceutics 2022, 14, 1678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, J.T.A.; Souza, P.F.N.; Vasconcelos, I.M.; Dias, L.P.; Martins, T.F.; Van Tilburg, M.F.; Guedes, M.I.F.; Sousa, D.O.B. Mo-CBP3-PepI, Mo-CBP3-PepII, and Mo-CBP3-PepIII Are Synthetic Antimicrobial Peptides Active against Human Pathogens by Stimulating ROS Generation and Increasing Plasma Membrane Permeability. Biochimie 2019, 157, 10–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mittler, R. ROS Are Good. Trends Plant Sci. 2017, 22, 11–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Z.; Chen, Y.; Li, B.; Chen, T.; Tian, S. Reactive Oxygen Species: A Generalist in Regulating Development and Pathogenicity of Phytopathogenic Fungi. Comput. Struct. Biotechnol. J. 2020, 18, 3344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, J.; Hwang, I. sok; Choi, H.; Hwang, J.H.; Hwang, J.S.; Lee, D.G. The Novel Biological Action of Antimicrobial Peptides via Apoptosis Induction. J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2012, 22, 1457–1466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- do Nascimento Dias, J.; de Souza Silva, C.; de Araújo, A.R.; Souza, J.M.T.; de Holanda Veloso Júnior, P.H.; Cabral, W.F.; da Glória da Silva, M.; Eaton, P.; de Souza de Almeida Leite, J.R.; Nicola, A.M.; et al. Mechanisms of Action of Antimicrobial Peptides ToAP2 and NDBP-5.7 against Candida Albicans Planktonic and Biofilm Cells. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, J.; Lee, D.G. Oxidative Stress by Antimicrobial Peptide Pleurocidin Triggers Apoptosis in Candida Albicans. Biochimie 2011, 93, 1873–1879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maurya, I.K.; Pathak, S.; Sharma, M.; Sanwal, H.; Chaudhary, P.; Tupe, S.; Deshpande, M.; Chauhan, V.S.; Prasad, R. Antifungal Activity of Novel Synthetic Peptides by Accumulation of Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS) and Disruption of Cell Wall against Candida Albicans. Peptides 2011, 32, 1732–1740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Uhl, L.; Gerstel, A.; Chabalier, M.; Dukan, S. Hydrogen Peroxide Induced Cell Death: One or Two Modes of Action? Heliyon 2015, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, M.; Wang, R.; Ding, N.; Liu, X.; Zheng, N.; Fu, B.; Sun, L.; Gao, P. Reactive Oxygen Species-Mediated Caspase-3 Pathway Involved in Cell Apoptosis of Karenia Mikimotoi Induced by Linoleic Acid. Algal Res. 2018, 36, 48–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keyer, K.; Imlay, J.A. Superoxide Accelerates DNA Damage by Elevating Free-Iron Levels. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1996, 93, 13635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguiar, T.K.B.; Neto, N.A.S.; Silva, R.R.S.; Freitas, C.D.T.; Mesquita, F.P.; Alencar, L.M.R.; Santos-oliveira, R.; Goldman, G.H.; Souza, P.F.N. Behind the Curtain : In Silico and In Vitro Experiments Brought to Light New Insights into the Anticryptococcal Action of Synthetic Peptides. 2023, 1–18.

- Branco, L.A.C.; Souza, P.F.N.; Neto, N.A.S.; Aguiar, T.K.B.; Silva, A.F.B.; Carneiro, R.F.; Nagano, C.S.; Mesquita, F.P.; Lima, L.B.; Freitas, C.D.T. New Insights into the Mechanism of Antibacterial Action of Synthetic Peptide Mo-CBP3-PepI against Klebsiella Pneumoniae. Antibiotics 2022, 11, 1753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belozerskaya, T.A.; Gessler, N.N. Reactive Oxygen Species and the Strategy of Antioxidant Defense in Fungi: A Review. Appl. Biochem. Microbiol. 2007, 43, 506–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asakura, H.; Kitahora, T. Antioxidants and Polyphenols in Inflammatory Bowel Disease: Ulcerative Colitis and Crohn Disease. Polyphenols Prev. Treat. Hum. Dis. 2018, 279–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Staerck, C.; Gastebois, A.; Vandeputte, P.; Calenda, A.; Larcher, G.; Gillmann, L.; Papon, N.; Bouchara, J.-P.; Fleury, M.J.J. Microbial Antioxidant Defense Enzymes. Microb. Pathog. 2017, 110, 56–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shigeoka, S.; Ishikawa, T.; Tamoi, M.; Miyagawa, Y.; Takeda, T.; Yabuta, Y.; Yoshimura, K. Regulation and Function of Ascorbate Peroxidase Isoenzymes. J. Exp. Bot. 2002, 53, 1305–1319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Silva Neto, J.X.; da Costa, H.P.S.; Vasconcelos, I.M.; Pereira, M.L.; Oliveira, J.T.A.; Lopes, T.D.P.; Dias, L.P.; Araújo, N.M.S.; Moura, L.F.W.G.; Van Tilburg, M.F.; et al. Role of Membrane Sterol and Redox System in the Anti-Candida Activity Reported for Mo-CBP2, a Protein from Moringa Oleifera Seeds. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2020, 143, 814–824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cirac, A.D.; Moiset, G.; Mika, J.T.; Koçer, A.; Salvador, P.; Poolman, B.; Marrink, S.J.; Sengupta, D. The Molecular Basis for Antimicrobial Activity of Pore-Forming Cyclic Peptides. Biophys. J. 2011, 100, 2422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lipkin, R.; Lazaridis, T. Computational Studies of Peptide-Induced Membrane Pore Formation. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 2017, 372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dupont, S.; Lemetais, G.; Ferreira, T.; Cayot, P.; Gervais, P.; Beney, L. Ergosterol Biosynthesis: A Fungal Pathway for Life on Land? Evolution 2012, 66, 2961–2968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farhana, A.; Lappin, S.L. Biochemistry, Lactate Dehydrogenase. StatPearls 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Ow, Y.L.P.; Green, D.R.; Hao, Z.; Mak, T.W. Cytochrome c: Functions beyond Respiration. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2008, 9, 532–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Swan, C.L.; Sistonen, L. Cellular Stress Response Cross Talk Maintains Protein and Energy Homeostasis. EMBO J. 2015, 34, 267–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishida, K.; Cipriano, T.F.; Rocha, G.M.; Weissmüller, G.; Gomes, F.; Miranda, K.; Rozental, S. Silver Nanoparticle Production by the Fungus Fusarium Oxysporum: Nanoparticle Characterisation and Analysis of Antifungal Activity against Pathogenic Yeasts. Mem. Inst. Oswaldo Cruz 2014, 109, 220–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wenzel, M.; Chiriac, A.I.; Otto, A.; Zweytick, D.; May, C.; Schumacher, C.; Gust, R.; Albada, H.B.; Penkova, M.; Krämer, U.; et al. Small Cationic Antimicrobial Peptides Delocalize Peripheral Membrane Proteins. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2014, 111, 1409–1418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Senges, C.H.R.; Stepanek, J.J.; Wenzel, M.; Raatschen, N.; Ay, Ü.; Märtens, Y.; Prochnow, P.; Hernández, M.V.; Yayci, A.; Schubert, B.; et al. Comparison of Proteomic Responses as Global Approach to Antibiotic Mechanism of Action Elucidation. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2021, 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maaß, S.; Bartel, J.; Mücke, P.A.; Schlüter, R.; Sura, T.; Zaschke-Kriesche, J.; Smits, S.H.J.; Becher, D. Proteomic Adaptation of Clostridioides Difficile to Treatment with the Antimicrobial Peptide Nisin. Cells 2021, 10, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsakou, F.; Jersie-Christensen, R.; Jenssen, H.; Mojsoska, B. The Role of Proteomics in Bacterial Response to Antibiotics. Pharmaceuticals 2020, 13, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moyer, T.B.; Purvis, A.L.; Wommack, A.J.; Hicks, L.M. Proteomic Response of Escherichia Coli to a Membrane Lytic and Iron Chelating Truncated Amaranthus Tricolor Defensin. BMC Microbiol. 2021, 21, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santi, L.; Beys-Da-Silva, W.O.; Berger, M.; Calzolari, D.; Guimarães, J.A.; Moresco, J.J.; Yates, J.R. Proteomic Profile of Cryptococcus Neoformans Biofilm Reveals Changes in Metabolic Processes. J. Proteome Res. 2014, 13, 1545–1559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Noronha Souza, P.F.; Abreu Oliveira, J.T.; Vasconcelos, I.M.; Magalhães, V.G.; Albuquerque Silva, F.D.; Guedes Silva, R.G.; Oliveira, K.S.; Franco, O.L.; Gomes Silveira, J.A.; Leite Carvalho, F.E. H2O2Accumulation, Host Cell Death and Differential Levels of Proteins Related to Photosynthesis, Redox Homeostasis, and Required for Viral Replication Explain the Resistance of EMS-Mutagenized Cowpea to Cowpea Severe Mosaic Virus. J. Plant Physiol. 2020, 245, 153110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shen, L.L.; Baranowski, J.; Fostel, J.; Montgomery, D.A.; Lartey, P.A. DNA Topoisomerases from Pathogenic Fungi: Targets for the Discovery of Antifungal Drugs. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 1992, 36, 2778–2784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa-Silva, H.M.; Resende, B.C.; Umaki, A.C.S.; Prado, W.; da Silva, M.S.; Virgílio, S.; Macedo, A.M.; Pena, S.D.J.; Tahara, E.B.; Tosi, L.R.O.; et al. DNA Topoisomerase 3α Is Involved in Homologous Recombination Repair and Replication Stress Response in Trypanosoma Cruzi. Front. cell Dev. Biol. 2021, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pommier, Y.; Redon, C.; Rao, V.A.; Seiler, J.A.; Sordet, O.; Takemura, H.; Antony, S.; Meng, L.H.; Liao, Z.Y.; Kohlhagen, G.; et al. Repair of and Checkpoint Response to Topoisomerase I-Mediated DNA Damage. Mutat. Res. - Fundam. Mol. Mech. Mutagen. 2003, 532, 173–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saita, S.; Shirane, M.; Nakayama, K.I. Selective Escape of Proteins from the Mitochondria during Mitophagy. Nat. Commun. 2013 41 2013, 4, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pérez-Treviño, P.; Velásquez, M.; García, N. Mechanisms of Mitochondrial DNA Escape and Its Relationship with Different Metabolic Diseases. Biochim. Biophys. Acta - Mol. Basis Dis. 2020, 1866, 165761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, P.; Yu, T.; Yoon, Y. Mitochondrial Clustering Induced by Overexpression of the Mitochondrial Fusion Protein Mfn2 Causes Mitochondrial Dysfunction and Cell Death. Eur. J. Cell Biol. 2007, 86, 289–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fields, S.D.; Arana, Q.; Heuser, J.; Clarke, M. Mitochondrial Membrane Dynamics Are Altered in CluA- Mutants of Dictyostelium. J. Muscle Res. Cell Motil. 2002, 23, 829–838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, Q.; Hulen, D.; Liu, T.; Clarke, M. The CluA- Mutant of Dictyostelium Identifies a Novel Class of Proteins Required for Dispersion of Mitochondria. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1997, 94, 7308–7313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nicoloff, H.; Hubert, J.C.; Bringel, F. In Lactobacillus Plantarum, Carbamoyl Phosphate Is Synthesized by Two Carbamoyl-Phosphate Synthetases (CPS): Carbon Dioxide Differentiates the Arginine-Repressed from the Pyrimidine-Regulated CPS. J. Bacteriol. 2000, 182, 3416–3422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, X.; Cai, Y.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, H.; Zheng, X.; Zhang, Z. Carbamoyl Phosphate Synthetase Subunit MoCpa2 Affects Development and Pathogenicity by Modulating Arginine Biosynthesis in Magnaporthe Oryzae. Front. Microbiol. 2016, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- W, P.; CG, P.; G, M. Shut-down of Translation, a Global Neuronal Stress Response: Mechanisms and Pathological Relevance. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2007, 13, 1887–1902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domínguez, J.M.; Kelly, V.A.; Kinsman, O.S.; Marriott, M.S.; Gómez De Las Heras, F.; Martín, J.J. Sordarins: A New Class of Antifungals with Selective Inhibition of the Protein Synthesis Elongation Cycle in Yeasts. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 1998, 42, 2274–2278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Signalling between Mitochondria and the Nucleus Regulates the Expression of a New D-lactate Dehydrogenase Activity in Yeast - Chelstowska - 1999 - Yeast - Wiley Online Library. Available online: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/pdf/10.1002/%28SICI%291097-0061%2819990930%2915%3A13%3C1377%3A%3AAID-YEA473%3E3.0.CO%3B2-0 (accessed on 17 January 2023).

- Becker-Kettern, J.; Paczia, N.; Conrotte, J.F.; Kay, D.P.; Guignard, C.; Jung, P.P.; Linster, C.L. Saccharomyces Cerevisiae Forms D-2-Hydroxyglutarate and Couples Its Degradation to d-Lactate Formation via a Cytosolic Transhydrogenase. J. Biol. Chem. 2016, 291, 6036–6058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- DH, L.; AL, G. Proteasome Inhibitors: Valuable New Tools for Cell Biologists. Trends Cell Biol. 1998, 8, 397–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, J. The Proteasome: Structure, Function, and Role in the Cell. Cancer Treat. Rev. 2003, 29, 3–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tanaka, K. The Proteasome: Overview of Structure and Functions. Proc. Jpn. Acad. Ser. B. Phys. Biol. Sci. 2009, 85, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duan, C.G.; Wang, X.; Zhang, L.; Xiong, X.; Zhang, Z.; Tang, K.; Pan, L.; Hsu, C.C.; Xu, H.; Tao, W.A.; et al. A Protein Complex Regulates RNA Processing of Intronic Heterochromatin-Containing Genes in Arabidopsis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2017, 114, E7377–E7384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calvanese, E.; Gu, Y. Towards Understanding Inner Nuclear Membrane Protein Degradation in Plants. J. Exp. Bot. 2022, 73, 2266–2274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zargari, A.; Boban, M.; Heessen, S.; Andréasson, C.; Thyberg, J.; Ljungdahl, P.O. Inner Nuclear Membrane Proteins Asi1, Asi2, and Asi3 Function in Concert to Maintain the Latent Properties of Transcription Factors Stp1 and Stp2. J. Biol. Chem. 2007, 282, 594–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awad, A.M.; Nag, A.; Pham, N.V.B.; Bradley, M.C.; Jabassini, N.; Nathaniel, J.; Clarke, C.F. Intragenic Suppressor Mutations of the COQ8 Protein Kinase Homolog Restore Coenzyme Q Biosynthesis and Function in Saccharomyces Cerevisiae. PLoS One 2020, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarke, C.F. Insights into an Ancient Atypical Kinase Essential for Biosynthesis of Coenzyme Q. Cell Chem. Biol. 2018, 25, 123–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, K.A.; Bobay, B.G.; Sarachan, K.L.; Sims, A.F.; Bilbille, Y.; Deutsch, C.; Iwata-Reuyl, D.; Agris, P.F. NMR-Based Structural Analysis of Threonylcarbamoyl-AMP Synthase and Its Substrate Interactions. J. Biol. Chem. 2015, 290, 20032–20043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Swinehart, W.; Deutsch, C.; Sarachan, K.L.; Luthra, A.; Bacusmo, J.M.; de Crécy-Lagard, V.; Swairjo, M.A.; Agris, P.F.; Iwata-Reuyl, D. Specificity in the Biosynthesis of the Universal TRNA Nucleoside N6-Threonylcarbamoyl Adenosine (T6A)—TsaD Is the Gatekeeper. RNA 2020, 26, 1094–1103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, H.Y.; Kim, D.K.; Bae, S.H.; Gwak, H.R.; Jeon, J.H.; Kim, J.K.; Lee, B. Il; You, H.J.; Shin, D.H.; Kim, Y.H.; et al. Farnesyl Diphosphate Synthase Is Important for the Maintenance of Glioblastoma Stemness. Exp. Mol. Med. 2018, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernandez, S.M.S.; Kellogg, B.A.; Poulter, C.D. Farnesyl Diphosphate Synthase. Altering the Catalytic Site to Select for Geranyl Diphosphate Activity. Biochemistry 2000, 39, 15316–15321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thulasiram, H. V.; Poulter, C.D. Farnesyl Diphosphate Synthase: The Art of Compromise between Substrate Selectivity and Stereoselectivity. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006, 128, 15819–15823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dhar, M.K.; Koul, A.; Kaul, S. Farnesyl Pyrophosphate Synthase: A Key Enzyme in Isoprenoid Biosynthetic Pathway and Potential Molecular Target for Drug Development. N. Biotechnol. 2013, 30, 114–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szymiczek, A.; Carbone, M.; Pastorino, S.; Napolitano, A.; Tanji, M.; Minaai, M.; Pagano, I.; Mason, J.M.; Pass, H.I.; Bray, M.R.; et al. Inhibition of the Spindle Assembly Checkpoint Kinase Mps-1 as a Novel Therapeutic Strategy in Malignant Mesothelioma. Oncogene 2017, 36, 6501–6507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maia, A.R.R.; De Man, J.; Boon, U.; Janssen, A.; Song, J.Y.; Omerzu, M.; Sterrenburg, J.G.; Prinsen, M.B.W.; Willemsen-Seegers, N.; De Roos, J.A.D.M.; et al. Inhibition of the Spindle Assembly Checkpoint Kinase TTK Enhances the Efficacy of Docetaxel in a Triple-Negative Breast Cancer Model. Ann. Oncol. Off. J. Eur. Soc. Med. Oncol. 2015, 26, 2180–2192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marston, A.L.; Wassmann, K. Multiple Duties for Spindle Assembly Checkpoint Kinases in Meiosis. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2017, 5, 109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kitajima, K.T.; Chiba, Y.; Jigami, Y. Mutation of High-Affinity Methionine Permease Contributes to Selenomethionyl Protein Production in Saccharomyces Cerevisiae. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2010, 76, 6351–6359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaumontet, C.; Azzout-Marniche, D.; Blais, A.; Piedcoq, J.; Tomé, D.; Gaudichon, C.; Even, P.C. Low-Protein and Methionine, High-Starch Diets Increase Energy Intake and Expenditure, Increase FGF21, Decrease IGF-1, and Have Little Effect on Adiposity in Mice. Am. J. Physiol. Regul. Integr. Comp. Physiol. 2019, 316, R486–R501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Agrellos, O.A.; Calderone, R. Histidine Kinases Keep Fungi Safe and Vigorous. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 2010, 13, 424–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Defosse, T.A.; Sharma, A.; Mondal, A.K.; de Bernonville, T.D.; Latgé, J.P.; Calderone, R.; Giglioli-Guivarc’h, N.; Courdavault, V.; Clastre, M.; Papon, N. Hybrid Histidine Kinases in Pathogenic Fungi. Mol. Microbiol. 2015, 95, 914–924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nostadt, R.; Hilbert, M.; Nizam, S.; Rovenich, H.; Wawra, S.; Martin, J.; Küpper, H.; Mijovilovich, A.; Ursinus, A.; Langen, G.; et al. A Secreted Fungal Histidine- and Alanine-Rich Protein Regulates Metal Ion Homeostasis and Oxidative Stress. New Phytol. 2020, 227, 1174–1188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Doige, C.A.; Ames, G.F.L. ATP-Dependent Transport Systems in Bacteria and Humans: Relevance to Cystic Fibrosis and Multidrug Resistance. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 1993, 47, 291–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hundal, T.; Norling, B.; Ernster, L. The Oligomycin Sensitivity Conferring Protein (OSCP) of Beef Heart Mitochondria: Studies of Its Binding to F1 and Its Function. J. Bioenerg. Biomembr. 1984, 16, 535–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parker, J.H.; Trimble, I.R.; Mattoon, J.R. Oligomycin Resistance in Normal and Mutant Yeast. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1968, 33, 590–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devenish, R.J.; Prescott, M.; Boyle, G.M.; Nagley, P. The Oligomycin Axis of Mitochondrial ATP Synthase: OSCP and the Proton Channel. J. Bioenerg. Biomembr. 2000, 32, 507–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kozubowski, L.; Panek, H.; Rosenthal, A.; Bloecher, A.; DeMarini, D.J.; Tatchell, K. A Bni4-Glc7 Phosphatase Complex That Recruits Chitin Synthase to the Site of Bud Emergence. Mol. Biol. Cell 2003, 14, 26–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Larson, J.R.; Kozubowski, L.; Tatchell, K. Changes in Bni4 Localization Induced by Cell Stress in Saccharomyces Cerevisiae. J. Cell Sci. 2010, 123, 1050–1059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marchant, R.; Smith, D.G. Bud Formation in Saccharomyces Cerevisiae and a Comparison with the Mechanism of Cell Division in Other Yeasts. J. Gen. Microbiol. 1968, 53, 163–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lima, P.G.; Souza, P.F.N.; Freitas, C.D.T.; Oliveira, J.T.A.; Dias, L.P.; Neto, J.X.S.; Vasconcelos, I.M.; Lopes, J.L.S.; Sousa, D.O.B. Anticandidal Activity of Synthetic Peptides: Mechanism of Action Revealed by Scanning Electron and Fluorescence Microscopies and Synergism Effect with Nystatin. J. Pept. Sci. 2020, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gandhi, M.; Goode, B.L. Coronin: The Double-Edged Sword of Actin Dynamics. Subcell. Biochem. 2008, 48, 72–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cai, L.; Makhov, A.M.; Bear, J.E. F-Actin Binding Is Essential for Coronin 1B Function in Vivo. J. Cell Sci. 2007, 120, 1779–1790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cai, L.; Marshall, T.W.; Uetrecht, A.C.; Schafer, D.A.; Bear, J.E. Coronin 1B Coordinates Arp2/3 Complex and Cofilin Activities at the Leading Edge. Cell 2007, 128, 915–929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nicholson, D.W.; Neupert, W. Import of Cytochrome c into Mitochondria: Reduction of Heme, Mediated by NADH and Flavin Nucleotides, Is Obligatory for Its Covalent Linkage to Apocytochrome C. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1989, 86, 4340–4344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dumont, M.E.; Cardillo, T.S.; Hayes, M.K.; Sherman, F. Role of Cytochrome c Heme Lyase in Mitochondrial Import and Accumulation of Cytochrome c in Saccharomyces Cerevisiae. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1991, 11, 5487–5496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dumont, M.E. Mitochondrial Import of Cytochrome C. Adv. Mol. Cell Biol. 1996, 17, 103–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NICHOLSON, D.W.; KÖHLER, H.; NEUPERT, W. Import of Cytochrome c into Mitochondria. Cytochrome c Heme Lyase. Eur. J. Biochem. 1987, 164, 147–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Plapp, B. V.; Green, D.W.; Sun, H.W.; Park, D.H.; Kim, K. Substrate Specificity of Alcohol Dehydrogenases. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 1993, 328, 391–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reid, M.F.; Fewson, C.A. Molecular Characterization of Microbial Alcohol Dehydrogenases. Crit. Rev. Microbiol. 1994, 20, 13–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fu, H.; Chung, K.R.; Liu, X.; Li, H. Aaprb1, a Subtilsin-like Protease, Required for Autophagy and Virulence of the Tangerine Pathotype of Alternaria Alternata. Microbiol. Res. 2020, 240, 126537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bryant, M.K.; Schardl, C.L.; Hesse, U.; Scott, B. Evolution of a Subtilisin-like Protease Gene Family in the Grass Endophytic Fungus Epichlo Festucae. BMC Evol. Biol. 2009, 9, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souza, P.F.N.; vanTilburg, M.F.; Mesquita, F.P.; Amaral, J.L.; Lima, L.B.; Montenegro, R.C.; Lopes, F.E.S.; Martins, R.X.; Vieira, L.; Farias, D.F.; et al. Neutralizing Effect of Synthetic Peptides toward SARS-CoV-2. ACS Omega 2022, 7, 16222–16234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dias, L.P.; Souza, P.F.N.; Oliveira, J.T.A.; Vasconcelos, I.M.; Araújo, N.M.S.; Tilburg, M.F. V; Guedes, M.I.F.; Carneiro, R.F.; Lopes, J.L.S.; Sousa, D.O.B. RcAlb-PepII, a Synthetic Small Peptide Bioinspired in the 2S Albumin from the Seed Cake of Ricinus Communis, Is a Potent Antimicrobial Agent against Klebsiella Pneumoniae and Candida Parapsilosis. Biochim. Biophys. Acta - Biomembr. 2020, 1862, 183092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, H.S.; Kim, J.W.; Cha, Y.; Kim, C. A Quantitative Nitroblue Tetrazolium Assay for Determining Intracellular Superoxide Anion Production in Phagocytic Cells. J. Immunoass. Immunochem. 2006, 27, 31–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MM, B. A Rapid and Sensitive Method for the Quantitation of Microgram Quantities of Protein Utilizing the Principle of Protein-Dye Binding. Anal. Biochem. 1976, 72, 248–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souza, P.F.N.; Silva, F.D.A.; Carvalho, F.E.L.; Silveira, J.A.G.; Vasconcelos, I.M.; Oliveira, J.T.A. Photosynthetic and Biochemical Mechanisms of an EMS-Mutagenized Cowpea Associated with Its Resistance to Cowpea Severe Mosaic Virus. Plant Cell Rep. 2017, 36, 219–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souza, P.F.N.; Vasconcelos, I.M.; Silva, F.D.A.; Moreno, F.B.; Monteiro-Moreira, A.C.O.; Alencar, L.M.R.; Abreu, A.S.G.; Sousa, J.S.; Oliveira, J.T.A. A 2S Albumin from the Seed Cake of Ricinus Communis Inhibits Trypsin and Has Strong Antibacterial Activity against Human Pathogenic Bacteria. J. Nat. Prod. 2016, 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).