Submitted:

14 January 2023

Posted:

25 January 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

Methods

Results

Discussion

INTRODUCTION

METHODS

Participants

Procedure

Design

Materials/Measures

Data Analysis

RESULTS

Demographics

Thresholds and mean scores

Correlation between fibromyalgia score and autistic traits

Correlations between food symptoms and other variables

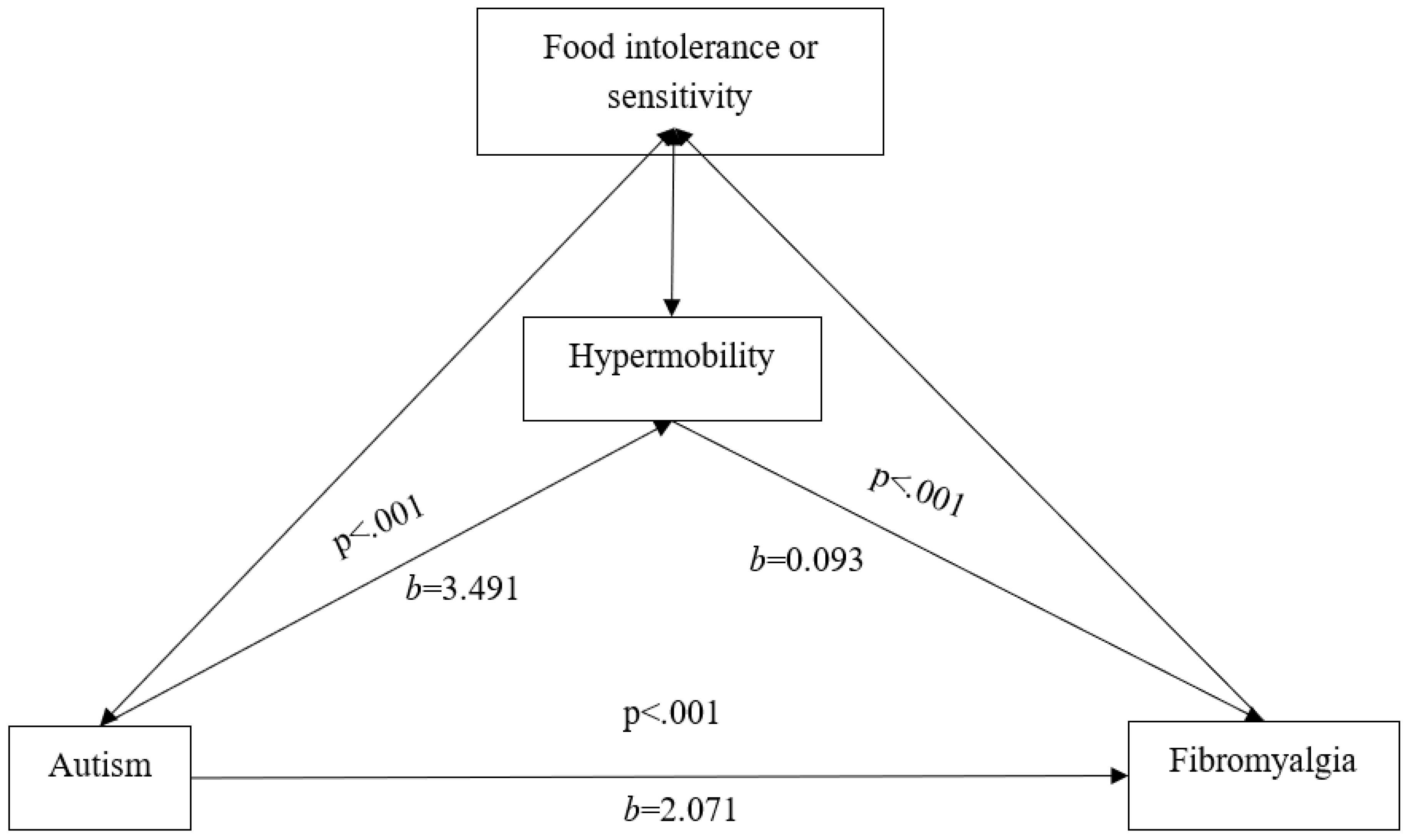

Regressions and variance

DISCUSSION

Limitations

Future Research

CONCLUSIONS

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

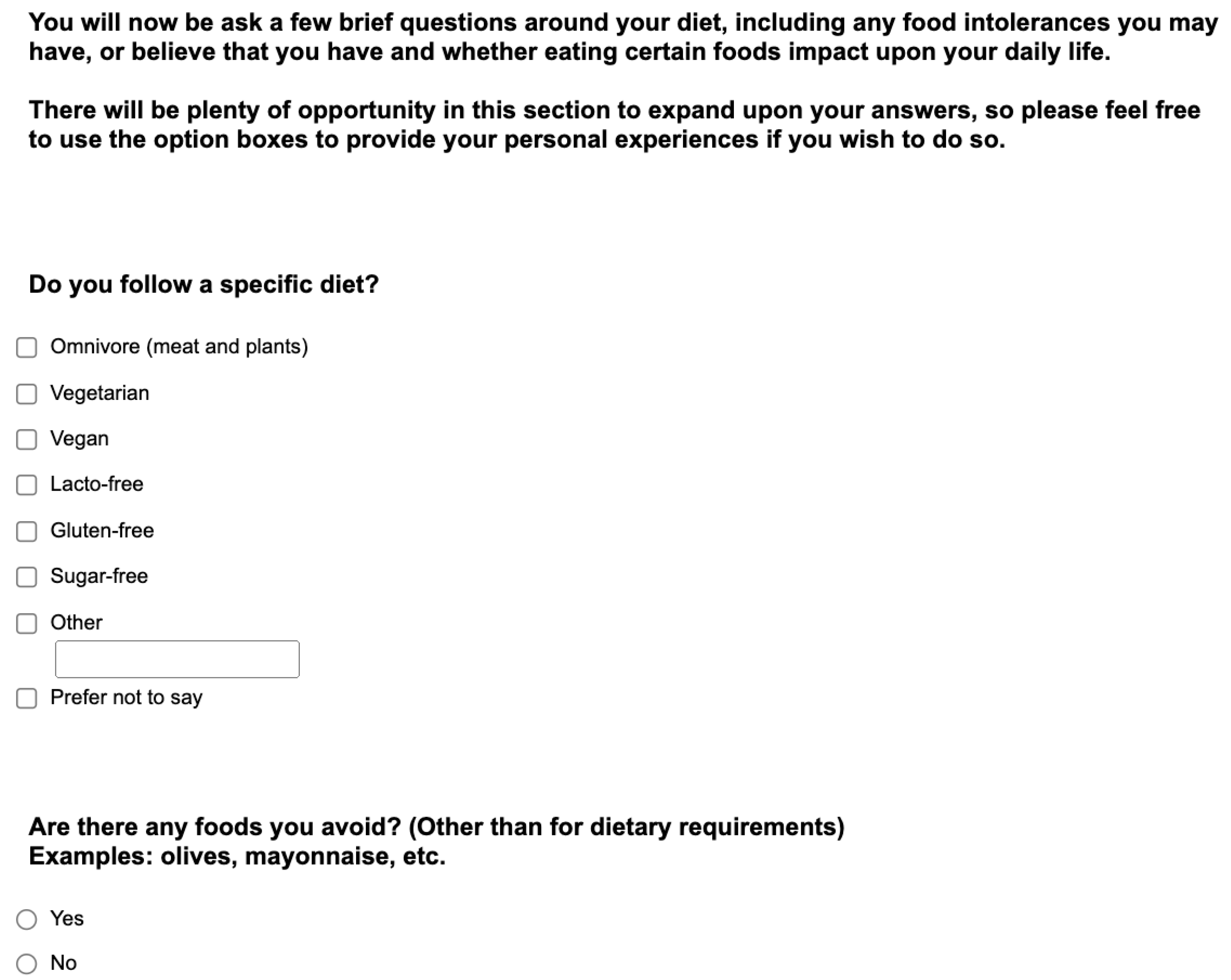

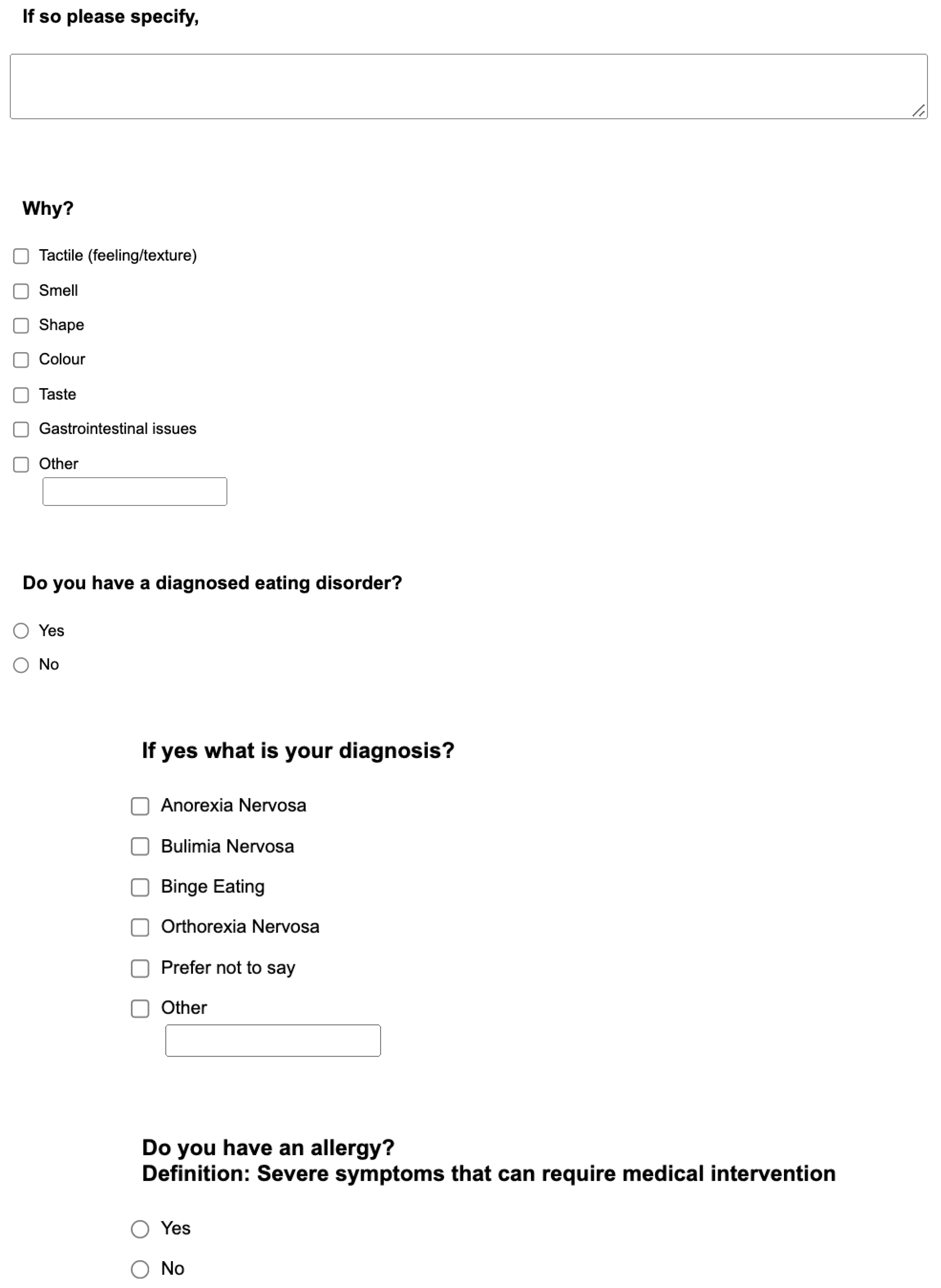

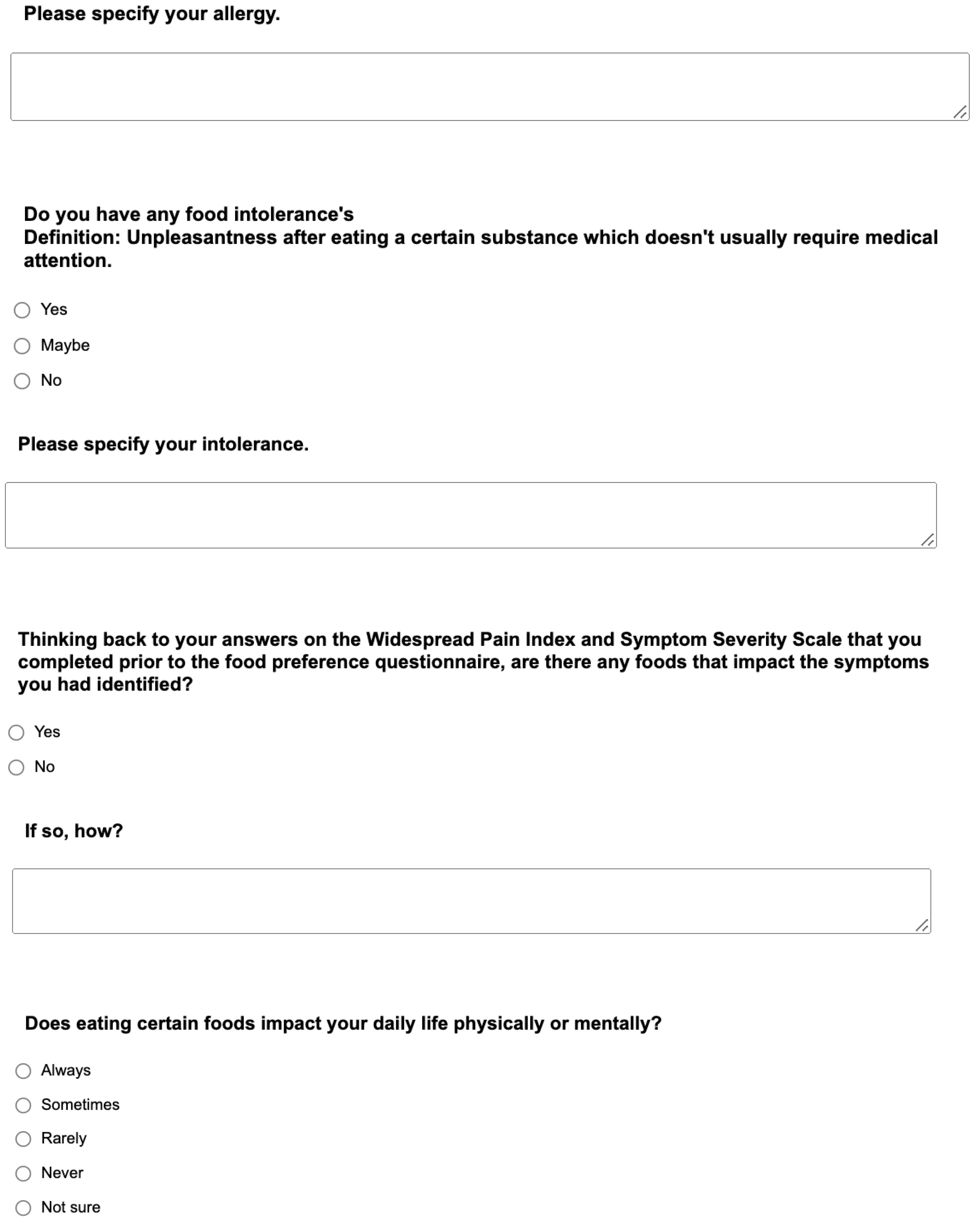

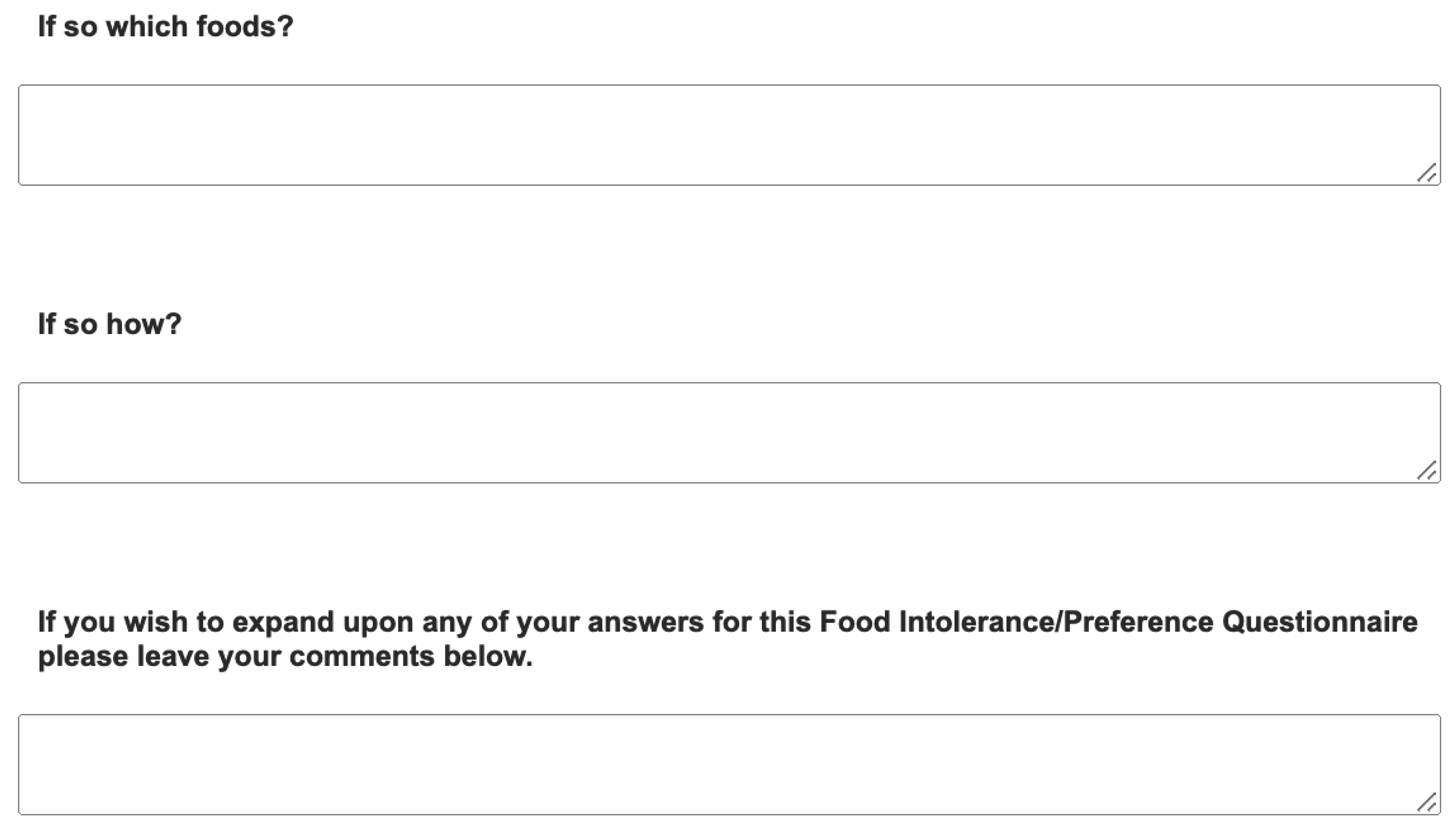

Appendix. Food preference questionnaire

References

- Wolfe, F., Clauw, D. J., Fitzcharles, M. A., et al. (2010). The American College of Rheumatology preliminary diagnostic criteria for fibromyalgia and measurement of symptom severity. Arthritis care and research, 62(5), 600-610. [CrossRef]

- Walitt, B., Nahin, R. L., Katz, R. S., Bergman, M. J., & Wolfe, F. (2015). The prevalence and characteristics of fibromyalgia in the 2012 National Health Interview Survey. PloS one, 10(9), e0138024. [CrossRef]

- Sarzi-Puttini, P., Giorgi, V., Marotto, D., & Atzeni, F. (2020). Fibromyalgia: an update on clinical characteristics, aetiopathogenesis and treatment. Nature Reviews Rheumatology, 16(11), 645-660. [CrossRef]

- Eccles, J. A., Thompson, B., Themelis, K., et al. (2021). Beyond bones: The relevance of variants of connective tissue (hypermobility) to fibromyalgia, ME/CFS and controversies surrounding diagnostic classification: an observational study. Clinical Medicine, 21(1), 53. [CrossRef]

- Bonaz B, Lane RD, Oshinsky ML, Kenny PJ, Sinha R, Mayer EA, Critchley HD. Diseases, Disorders, and Comorbidities of Interoception. Trends Neurosci. 2021 Jan;44(1):39-51. PMID: 33378656. [CrossRef]

- Whealy, M., Nanda, S., Vincent, A., Mandrekar, J., & Cutrer, F. M. (2018). Fibromyalgia in migraine: A retrospective cohort study [Abstract]. The Journal of Headache and Pain, 19(1). [CrossRef]

- Clauw DJ. Fibromyalgia and related conditions. Mayo Clin Proc. 2015 May;90(5):680-92. PMID: 25939940. [CrossRef]

- Isasi C, Colmenero I, Casco F, Tejerina E, Fernandez N, Serrano-Vela JI, W al. Fibromyalgia and non-celiac gluten sensitivity: a description with remission of fibromyalgia. Rheumatol Int. 2014 Nov;34(11):1607-12. Epub 2014 Apr 12. PMID: 24728027; PMCID: PMC4209093. [CrossRef]

- Slim, M, Calandre, E, Garcia-Leiva, J, Rico-Villademoros, F, Molina-Barea, R, Rodriguez-Lopez, C et al. The Effects of a Gluten-free Diet Versus a Hypocaloric Diet Among Patients With Fibromyalgia Experiencing Gluten Sensitivity-like Symptoms: A Pilot, Open-Label Randomized Clinical Trial. [Article] Journal of Clinical Gastroenterology. 51(6):500-507, July 2017.

- Rossi A, Di Lollo AC, Guzzo MP, Giacomelli C, Atzeni F, Bazzichi L, et al. Fibromyalgia and nutrition: what news? Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2015 Jan-Feb;33(1 Suppl 88):S117-25. Epub 2015 Mar 18. PMID: 25786053.

- Marum AP, Moreira C, Saraiva F, Tomas-Carus P, Sousa-Guerreiro C. A low fermentable oligo-di-monosaccharides and polyols (FODMAP) diet reduced pain and improved daily life in fibromyalgia patients. Scand J Pain. 2016 Oct;13:166-172. Epub 2016 Aug 22. PMID: 28850525. [CrossRef]

- Silva AR, Bernardo A, Costa J, Cardoso A, Santos P, de Mesquita MF, et al. Dietary interventions in fibromyalgia: a systematic review. Ann Med. 2019;51(sup1):2-14. PMID: 30735059; PMCID: PMC7888848. [CrossRef]

- Leader, G., Tuohy, E., Chen, J. L., Mannion, A., & Gilroy, S. P. (2020). Feeding problems, gastrointestinal symptoms, challenging behaviors and sensory issues in children and adolescents with autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 50(1), 1401–1410. [CrossRef]

- Cermak SA, Curtin C, Bandini LG. Food selectivity and sensory sensitivity in children with autism spectrum disorders. J Am Diet Assoc. 2010 Feb;110(2):238-46. PMID: 20102851; PMCID: PMC3601920. [CrossRef]

- Buckley, Julie A., Herbert, Martha R., (2013). Autism and dietary therapy: case report and review of the literature. Journal of Child Neurology. [CrossRef]

- Lange KW, Hauser J, Reissmann A. Gluten-free and casein-free diets in the therapy of autism. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care. 2015 Nov;18(6):572-5. PMID: 26418822. [CrossRef]

- Mulloy, A. et al., (2010), Gluten-Free and Casein free diets in the treatment of autism spectrum disorders: A systematic review. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorder, Vol 4 (3), pp.328-339.

- Hyman SL, Stewart PA, Foley J, Cain U, Peck R, Morris DD, Wang H, Smith T. The Gluten-Free/Casein-Free Diet: A Double-Blind Challenge Trial in Children with Autism. J Autism Dev Disord. 2016 Jan;46(1):205-220. PMID: 26343026. [CrossRef]

- Kelly C, Davies M. A Review of Anorexia Nervosa, Its Relationship to Autism and Borderline Personality Disorder, and Implications for Patient Related Outcomes. Journal of Psychiatry and Psychiatric Disorders 3 (2019): 207-215. Review Article Volume 3, Issue 4. [CrossRef]

- van Rensburg R, Meyer HP, Hitchcock SA, Schuler CE. Screening for Adult ADHD in Patients with Fibromyalgia Syndrome. Pain Med. 2018;19(9):1825-1831. [CrossRef]

- Moyano S, Berrios W, Gandino IJ, et al. Prevalence of Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder Among Patients with Fibromyalgia [abstract]. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2018;70 (suppl 10).

- Pallanti S, Porta F, Salerno L. Adult attention deficit hyperactivity disorder in patients with fibromyalgia syndrome: Assessment and disabilities. J Psychiatr Res. 2021;136:537-542. [CrossRef]

- Karaş H, Çetingök H, İlişer R, et al. Childhood and adult attention deficit hyperactivity disorder symptoms in fibromyalgia: associations with depression, anxiety and disease impact. Int J Psychiatry Clin Pract. 2020;24(3):257-263. [CrossRef]

- Türkoğlu G. Attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder symptoms and quality of life in female patients with fibromyalgia. Turk J Med Sci. 2021;51(4):1747-1755. Published 2021 Aug 30. [CrossRef]

- Holman AJ, Neiman RA, Ettlinger RE. Preliminary efficacy of the dopamine agonist, pramipexole for fibromyalgia: the first, open label, multicenter experience. _J Musculoskeletal Pain.2004;12(1):69-74.

- Critchley, H. D., & Eccles, J. A. (2020). Increased rate of joint hypermobility in autism and related neurodevelopmental conditions is linked to dysautonomia and pain. MedRxiv. [CrossRef]

- Dietz, P. M., Rose, C. E., McArthur, D., & Maenner, M. (2020). National and state estimates of adults with autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 50(12), 4258-4266. [CrossRef]

- Eccles, J. A., Iodice, V., Dowell, N. G., et al. (2014). Joint hypermobility and autonomic hyperactivity: relevance to neurodevelopmental disorders. Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery & Psychiatry, 85(8), e3-e3. [CrossRef]

- Baeza-Velasco C, Cohen D, Hamonet C, Vlamynck E, Diaz L, Cravero C, Cappe E, Guinchat V. Autism, Joint Hypermobility-Related Disorders and Pain. Front Psychiatry. 2018 Dec 7;9:656. PMID: 30581396; PMCID: PMC6292952. [CrossRef]

- Casanova EL, Baeza-Velasco C, Buchanan CB, Casanova MF. The Relationship between Autism and Ehlers-Danlos Syndromes/Hypermobility Spectrum Disorders. J Pers Med. 2020 Dec 1;10(4):260. PMID: 33271870; PMCID: PMC7711487. [CrossRef]

- Asztély K, Kopp S, Gillberg C, Waern M, Bergman S. Chronic pain and health-related quality of life in women with autism and/or ADHD: a prospective longitudinal study. J Pain Res. (2019) 12:2925–32. [CrossRef]

- Csecs, J. L., Iodice, V., Rae, C. L., et al. (2022). Joint Hypermobility Links Neurodivergence to Dysautonomia and Pain. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 2568. [CrossRef]

- Cederlöf, M., Larsson, H., Lichtenstein, P., Almqvist, C., Serlachius, E., and Ludvigsson, J. F. (2016). Nationwide population-based cohort study of psychiatric disorders in individuals with Ehlers–Danlos syndrome or hypermobility syndrome and their siblings. BMC psychiatry, 16(1), 1-7. [CrossRef]

- Wolfe, F., Ross, K., Anderson, J., Russell, I. J., & Hebert, L. (1995). The prevalence and characteristics of fibromyalgia in the general population. Arthritis & Rheumatism: Official Journal of the American College of Rheumatology, 38(1), 19-28. [CrossRef]

- Castori, M., Morlino, S., Pascolini, G., Blundo, C., & Grammatico, P. (2015, March). Gastrointestinal and nutritional issues in joint hypermobility syndrome/Ehlers–Danlos syndrome, hypermobility type. In American Journal of Medical Genetics Part C: Seminars in Medical Genetics (Vol. 169, No. 1, pp. 54-75). [CrossRef]

- Ryan L, Beer H, Thomson E, Philcox E and Kelly CA. Neurodivergent traits correlate with chronic musculoskeletal pain: a self-selected population-based survey. In press Neurobiology; 2022.

- Wolfe F., Clauw D.J., Fitzcharles M.A., Goldenberg D.L., Häuser W., Katz R.S., Mease P., Russell A.S., Russell I.J., Winfield J.B. Fibromyalgia criteria and severity scales for clinical and epidemiological studies: A modification of the ACR preliminary diagnostic criteria for fibromyalgia. JRheumatol. 2011; 38:1113–1122. [CrossRef]

- Aguirre Cárdenas C, Oñederra MC, Esparza Benavente C, Durán J, González Tugas M, Gómez-Pérez L. Psychometric Properties of the Fibromyalgia Survey Questionnaire in Chilean Women With Fibromyalgia. J Clin Rheumatol. 2021 Sep 1;27(6S):S284-S293. PMID: 32897990. [CrossRef]

- Ritvo, R. A., Ritvo, E. R., Guthrie, D., et al. (2011). The Ritvo Autism Asperger Diagnostic Scale-Revised (RAADS-R): a scale to assist the diagnosis of autism spectrum disorder in adults: an international validation study. Journal of autism and developmental disorders, 41(8), 1076-1089. [CrossRef]

- Juul-Kristensen B, Schmedling K, Rombaut L, Lund H, Engelbert RH. Measurement properties of clinical assessment methods for classifying generalized joint hypermobility-A systematic review. Am J Med Genet C Semin Med Genet. 2017 Mar;175(1):116-147. PMID: 28306223. [CrossRef]

- Bockhorn, L. N., Vera, A. M., Dong, D., Delgado, D. A., Varner, K. E., & Harris, J. D. (2021). Interrater and intra-rater reliability of the Beighton score: A systematic review. Orthopaedic Journal of Sports Medicine, 9(1), 2325967120968099. [CrossRef]

- https://www.statisticshowto.com/probability-and-statistics/correlation-coefficient-formula/.

- Yunus, M. B., Inanici, F. A. T. M. A., Aldag, J. C., & Mangold, R. F. (2000). Fibromyalgia in men: comparison of clinical features with women. The Journal of rheumatology, 27(2), 485-490. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/10685818.

- Guzzo, M. P., Iannuccelli, C., Gerardi, M. C., Lucchino, B., Valesini, G., & Di Franco, M. (2017). AB0925 Gender difference in fibromyalgia: comparison between male and female patients from an italian monocentric cohort. [CrossRef]

- Stubbs D, Krebs E, Bair M, Damush T, Wu J, Sutherland J, et al. Sex Differences in Pain and Pain-Related Disability among Primary Care Patients with Chronic Musculoskeletal Pain. Pain Medicine. 2010;11(2):232–9. pmid:20002591.

- Wilbarger, J. L., & Cook, D. B. (2011). Multisensory hypersensitivity in women with fibromyalgia: implications for well being and intervention. Archives of physical medicine and rehabilitation, 92(4), 653-656. [CrossRef]

- Bair, M. J., & Krebs, E. E. (2020). Fibromyalgia. Annals of internal medicine, 172(5), ITC33-ITC48. [CrossRef]

- Häuser, W., Ablin, J., Fitzcharles, M. A., Littlejohn, G., Luciano, J. V., Usui, C., & Walitt, B. (2015). Fibromyalgia. Nature reviews Disease primers, 1(1), 1-16. [CrossRef]

- English, B. (2014). Neural and psychosocial mechanisms of pain sensitivity in fibromyalgia. Pain Management Nursing, 15(2), 530-538. [CrossRef]

- Littlejohn G., Guymer E. Key milestones contributing to the understanding of the mechanisms underlying fibromyalgia. Biomedicines. 2020;8:223. [CrossRef]

- Slim, M., Calandre, E. P., & Rico-Villademoros, F. (2015). An insight into the gastrointestinal component of fibromyalgia: clinical manifestations and potential underlying mechanisms. Rheumatology international, 35(3), 433-444. [CrossRef]

- Losurdo G, Principi M, Iannone A, Amoruso A, Ierardi E, Di Leo A, Barone M. Extra-intestinal manifestations of non-celiac gluten sensitivity: An expanding paradigm. World J Gastroenterol. 2018 Apr 14;24(14):1521-1530. PMID: 29662290; PMCID: PMC5897856. [CrossRef]

- Minerbi A, Gonzalez E, Brereton NJB, et al. Gut microbiota may play a pivotal role in fibromyalgia. Pain. 2019 Nov;160(11):2589-2602. [CrossRef]

- Erdrich, S., Hawrelak, J.A., Myers, S.P. et al. Determining the association between fibromyalgia, the gut microbiome and its biomarkers: A systematic review. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 21, 181 (2020). [CrossRef]

- Rondanelli, M., Faliva, M., Miccono, A., Naso, M., Nichetti, M., Riva, A et al. (2018). Food pyramid for subjects with chronic pain: Foods and dietary constituents as anti-inflammatory and antioxidant agents. Nutrition Research Reviews, 31(1), 131-151. [CrossRef]

- Pagliai G, Giangrandi I, Dinu M, Sofi F, Colombini B. Nutritional Interventions in the Management of Fibromyalgia Syndrome. Nutrients. 2020 Aug 20;12(9):2525. PMID: 32825400; PMCID: PMC7551285. [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Araque A, Verde Z, Torres-Ortega C, Sainz-Gil M, Velasco-Gonzalez V, González-Bernal JJ, et al. Effects of Antioxidants on Pain Perception in Patients with Fibromyalgia-A Systematic Review. J Clin Med. 2022 Apr 27;11(9):2462. PMID: 35566585; PMCID: PMC9099826. [CrossRef]

- Lowry E, Marley J, McVeigh JG, McSorley E, Allsopp P, Kerr D. Dietary Interventions in the Management of Fibromyalgia: A Systematic Review and Best-Evidence Synthesis. Nutrients. 2020 Aug 31;12(9):2664. PMID: 32878326; PMCID: PMC7551150. [CrossRef]

- Tomaino L, Serra-Majem L, Martini S, Ingenito MR, Rossi P, La Vecchia C, et al. Fibromyalgia and Nutrition: An Updated Review. J Am Coll Nutr. 2021 Sep-Oct;40(7):665-678. Epub 2020 Sep 9. PMID: 32902371. [CrossRef]

- Almutairi NM, Hilal FM, Bashawyah A, Dammas FA, Yamak Altinpulluk E, Hou JD, et al. Efficacy of Acupuncture, Intravenous Lidocaine, and Diet in the Management of Patients with Fibromyalgia: A Systematic Review and Network Meta-Analysis. Healthcare (Basel). 2022 Jun 23;10(7):1176. PMID: 35885703; PMCID: PMC9320380. [CrossRef]

- Demori I, Molinari E, Rapallo F, Mucci V, Marinelli L, Losacco S, et al. Online Questionnaire with Fibromyalgia Patients Reveals Correlations among Type of Pain, Psychological Alterations, and Effectiveness of Non-Pharmacological Therapies. Healthcare (Basel). 2022 Oct 9;10(10):1975. PMID: 36292422; PMCID: PMC9602604. [CrossRef]

- Kelly C, Martin R and Saravanan V. The links between fibromyalgia, hypermobility and neurodivergence. TouchReviews March 15th 2022.

- Clark, C. J., Khattab, A. D., & Carr, E. C. (2014). Chronic widespread pain and neurophysiological symptoms in joint hypermobility syndrome (JHS). International Journal of Therapy and Rehabilitation, 21(2), 60-67. [CrossRef]

- Critchley, H. D., & Davies, K. A. (2021). Beyond bones: The relevance of variants of connective tissue (hypermobility) to fibromyalgia, ME/CFS and controversies surrounding diagnostic classification: an observational study. Clinical Medicine, 21(1), 53. [CrossRef]

- Song, R; Liu, J PhD; Kong, X. Autonomic Dysfunction and Autism: Subtypes and Clinical Perspectives. N A J Med Sci. 2016;9(4):172-180. DOI: 10.7156/najms.2016.0904172.

- Puri BK, Lee GS. Clinical Assessment of Autonomic Function in Fibromyalgia by the Refined and Abbreviated Composite Autonomic Symptom Score (COMPASS 31): A Case-Controlled Study. Rev Recent Clin Trials. 2022;17(1):53-57. PMID: 34126910. [CrossRef]

- Brent Goodman. Autonomic Dysfunction in Autism Spectrum Disorders (ASD) (P5.117) Neurology Apr 2016, 86 (16 Supplement) P5.117-9.

- Mari-Bauset, S., Zazpe, I., Mari-Sanchis, A., Llopis-Gonzalez, A., Morales-Suarez-Varel, M. (2014). Food selectivity in autism spectrum disorders: A systematic review. Journal of Child Neurology, 29(11), 1554–1561. [CrossRef]

- Jyonouchi H. Food allergy and autism spectrum disorders: is there a link? Curr Allergy Asthma Rep. 2009 May;9(3):194-201. PMID: 19348719.. [CrossRef]

- Kuschner, E. S., Eisenberg, I. W., Orionzi, B., Simmons, W. K., Kenworthy, L., Martin, A., et al.. (2015). A preliminary study of self-reported food selectivity in adolescents and young adults with autism spectrum disorder. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 15–16, 53–59. [CrossRef]

- Buie T. The relationship of autism and gluten. Clin Ther. 2013 May;35(5):578-83. PMID: 23688532. [CrossRef]

- Sumathi T, Manivasagam T, Thenmozhi AJ. The Role of Gluten in Autism. Adv Neurobiol. 2020; 24:469-479. PMID: 32006368. [CrossRef]

- Croall ID, Hoggard N, Hadjivassiliou M. Gluten and Autism Spectrum Disorder. Nutrients. 2021 Feb 9;13(2):572. PMID: 33572226; PMCID: PMC7915454. [CrossRef]

- Pubylski-Yanofchick, W., Zaki-Scarpa, C., LaRue, R.H. et al. Treatment of Food Selectivity in an Adult With Autism Spectrum Disorder. Behav Analysis Practice 15, 796–803 (2022). [CrossRef]

- Macfarlane, G.J. and Beasley, M. (2015), Alcohol Consumption in Relation to Risk and Severity of Chronic Widespread Pain: Results From a UK Population-Based Study. Arthritis Care & Research, 67: 1297-1303. [CrossRef]

- Durán, Josefina MD, MS∗; Zitko, Pedro PhD†,‡; Barrios, Paola MD∗; Margozzini, Paula MD, MS‡. Chronic Musculoskeletal Pain and Chronic Widespread Pain in Chile: Prevalence Study Performed as Part of the National Health Survey. JCR: Journal of Clinical Rheumatology 27(6S):p S294-S300, September 2021.

- Paul Whiteley (2014) Nutritional management of (some) autism: a case for gluten and casein free diets? The Proceedings of the Nutritional Society, Vol. 74 (3), pp. 202-207 .

| Food sensitivity | Food allergy | Food intolerance | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fibromyalgia RAADS-R |

.240*** .172** |

.182*** .125* |

.380*** .148** |

| Beighton | .041 | .135** | .157** |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).