Submitted:

14 January 2023

Posted:

25 January 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study design, participants, and procedure

2.2. Study Instruments

2.3. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Characteristics of the participants

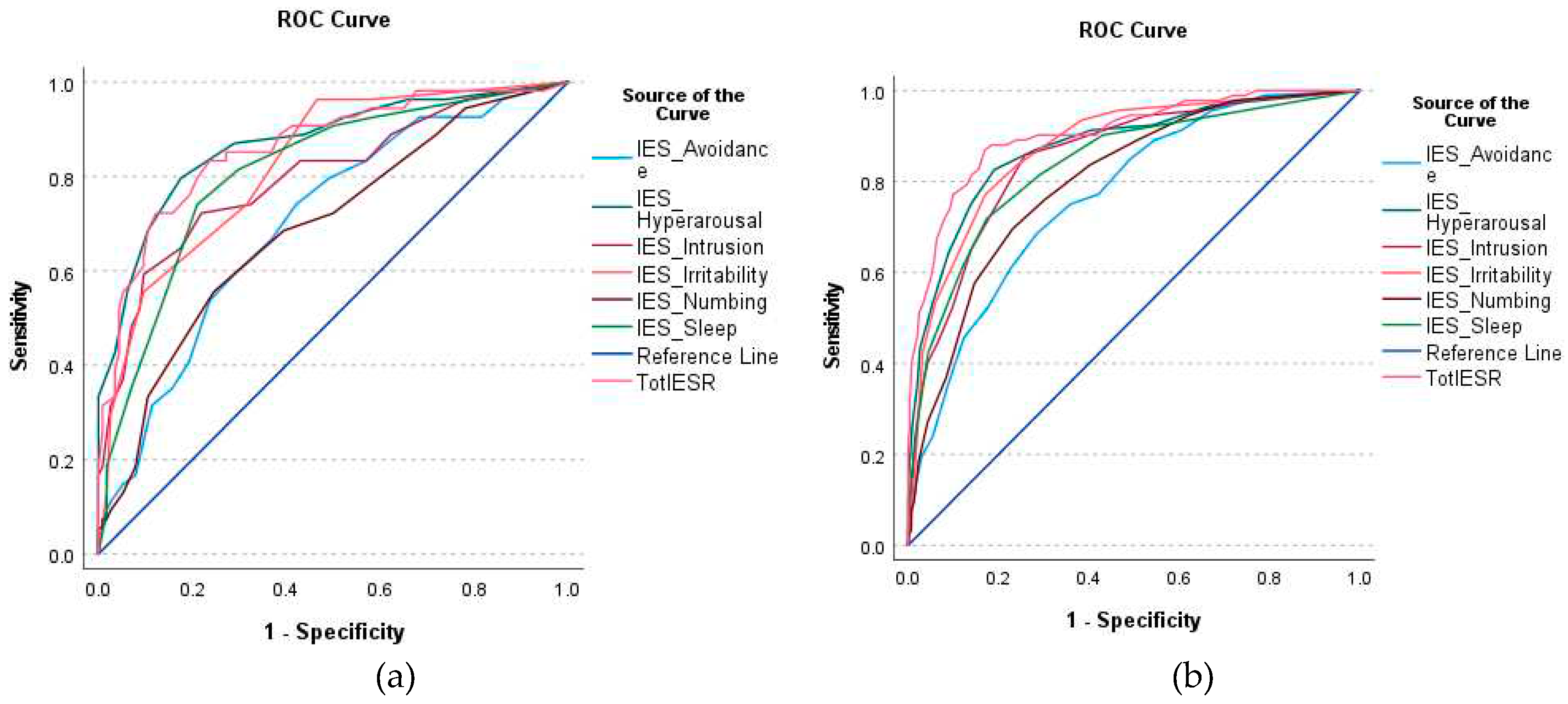

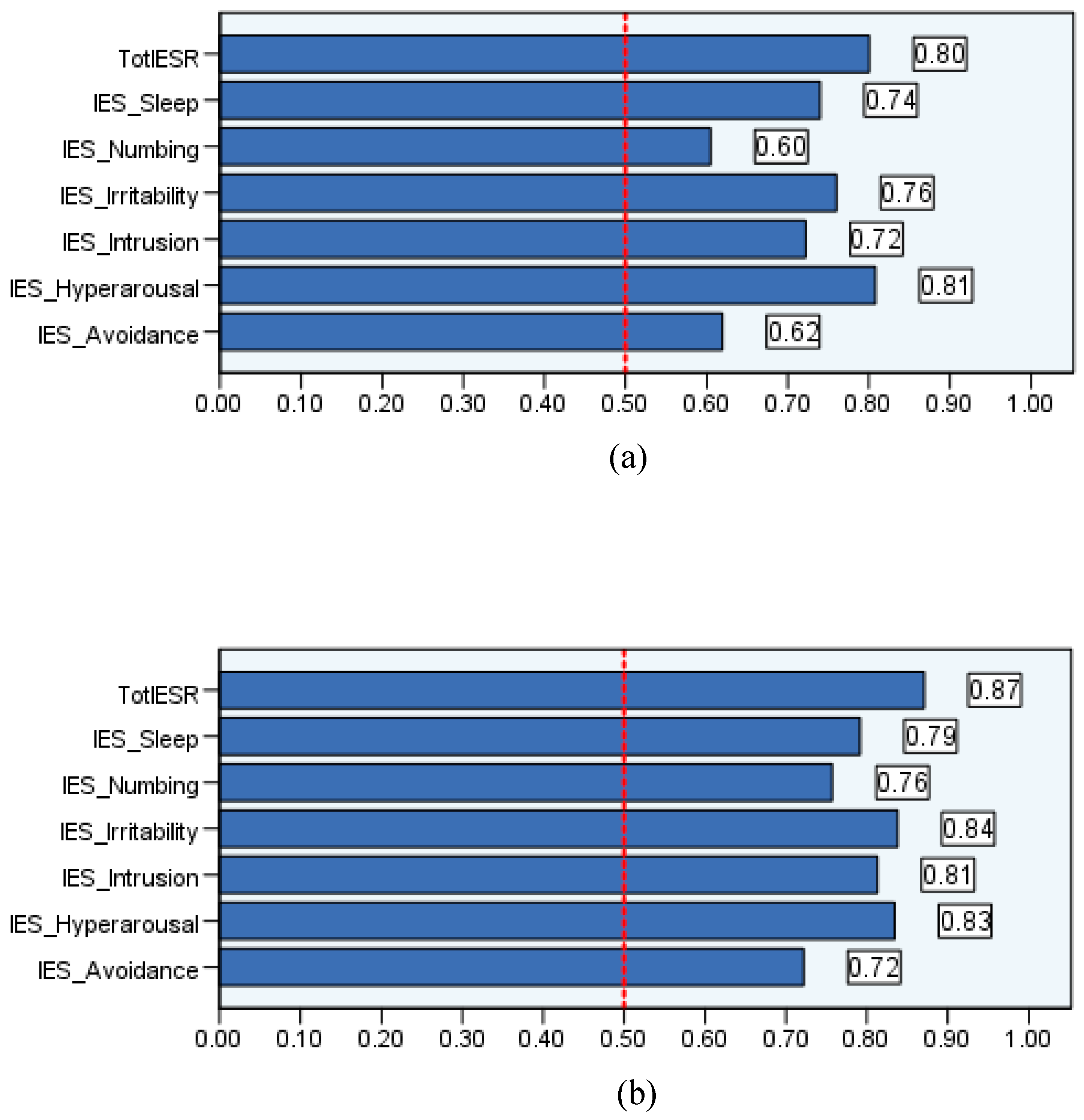

3.2. Receiver-operating characteristic (ROC) determining the cutoff of the Arabic version of the Impact of Event Scale-Revised (IES-R)

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Qiu, J.; Shen, B.; Zhao, M.; Wang, Z.; Xie, B.; Xu, Y. A nationwide survey of psychological distress among Chinese people in the COVID-19 epidemic: implications and policy recommendations. Gen Psychiatr 2020, 33, e100213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, C.; Pan, R.; Wan, X.; Tan, Y.; Xu, L.; McIntyre, R.S.; Choo, F.N.; Tran, B.; Ho, R.; Sharma, V.K., et al. A longitudinal study on the mental health of general population during the COVID-19 epidemic in China. Brain Behav Immun 2020, 87, 40–48. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nagarajan, R.; Krishnamoorthy, Y.; Basavarachar, V.; Dakshinamoorthy, R. Prevalence of post-traumatic stress disorder among survivors of severe COVID-19 infections: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Affect Disord 2022, 299, 52–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Amer, R.; Malak, M.Z.; Burqan, H.M.R.; Stănculescu, E.; Nalubega, S.; Alkhamees, A.A.; Hendawy, A.O.; Ali, A.M. Emotional Reaction to the First Dose of COVID-19 Vaccine: Postvaccination Decline in Anxiety and Stress among Anxious Individuals and Increase among Individuals with Normal Prevaccination Anxiety Levels. Journal of Personalized Medicine 2022, 12, 912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chew, Q.H.; Wei, K.C.; Vasoo, S.; Chua, H.C.; Sim, K. Narrative synthesis of psychological and coping responses towards emerging infectious disease outbreaks in the general population: practical considerations for the COVID-19 pandemic. Singapore Med J 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Z.; Ge, J.; Yang, M.; Feng, J.; Qiao, M.; Jiang, R.; Bi, J.; Zhan, G.; Xu, X.; Wang, L., et al. Vicarious traumatization in the general public, members, and non-members of medical teams aiding in COVID-19 control. Brain Behav Immun 2020, 88, 916–919. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karbasi, Z.; Eslami, P. Prevalence of post-traumatic stress disorder during the COVID-19 pandemic in children: a review and suggested solutions. Middle East Current Psychiatry 2022, 29, 74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, A.M.; Hendawy, A.O.; Almarwani, A.M.; Alzahrani, N.; Ibrahim, N.; Alkhamees, A.A.; Kunugi, H. The Six-item Version of the Internet Addiction Test: Its development, psychometric properties, and measurement invariance among women with eating disorders and healthy school and university students. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2021, 18, 12341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ali, A.M.; Hori, H.; Kim, Y.; Kunugi, H. Predictors of nutritional status, depression, internet addiction, Facebook addiction, and tobacco smoking among women with eating disorders in Spain. Frontiers in Psychiatry 2021, 12, 2001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trnka, R.; Lorencova, R. Fear, anger, and media-induced trauma during the outbreak of COVID-19 in the Czech Republic. Psychol Trauma 2020, 12, 546–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ali, A.M.; Alkhamees, A.A.; Elhay, E.S.A.; Taha, S.M.; Hendawy, A.O. COVID-19-related psychological trauma and psychological distress among community-dwelling psychiatric patients: people struck by depression and sleep disorders endure the greatest burden. Frontiers in Public Health 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andhavarapu, S.; Yardi, I.; Bzhilyanskaya, V.; Lurie, T.; Bhinder, M.; Patel, P.; Pourmand, A.; Tran, Q.K. Post-traumatic stress in healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychiatry Res 2022, 317, 114890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, W.; Zhao, N.; Yan, X.; Xu, X.; Zou, S.; Wang, H.; Li, Y.; Du, X.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, Q., et al. Network Analysis of Depression, Anxiety, Posttraumatic Stress Symptoms, Insomnia, Pain, and Fatigue in Clinically Stable Older Patients With Psychiatric Disorders During the COVID-19 Outbreak. J Geriatr Psychiatry Neurol 2022, 35, 196–205. [CrossRef]

- Idoiaga, N.; Legorburu, I.; Ozamiz-Etxebarria, N.; Lipnicki, D.M.; Villagrasa, B.; Santabárbara, J. Prevalence of Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) in University Students during the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Meta-Analysis Attending SDG 3 and 4 of the 2030 Agenda. Sustainability 2022, 14, 7914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, R.; Zhou, X. Differences in posttraumatic stress disorder networks between young adults and adolescents during the COVID-19 pandemic. Psychol Trauma 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders: DSM-5-TR. 2022.

- Bryant, R.A. Post-traumatic stress disorder as moderator of other mental health conditions. World Psychiatry 2022, 21, 310–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, N.; Chung, M.C.; Zhang, J.; Fang, S. Network analysis on the relationship between posttraumatic stress disorder, psychiatric co-morbidity and posttraumatic growth among Chinese adolescents. J Affect Disord 2022, 309, 461–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, F.; Zhang, D.; Wu, L.; Mu, H. Predicting Psychological State Among Chinese Undergraduate Students in the COVID-19 Epidemic: A Longitudinal Study Using a Machine Learning. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat 2020, 16, 2111–2118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Debowska, A.; Horeczy, B.; Boduszek, D.; Dolinski, D. A repeated cross-sectional survey assessing university students' stress, depression, anxiety, and suicidality in the early stages of the COVID-19 pandemic in Poland. Psychol Med 2020, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, M.-J.; Paek, S.-H.; Kwon, J.-H.; Park, S.-H.; Chung, H.-J.; Byun, Y.-H. Changes in Suicide Rate and Characteristics According to Age of Suicide Attempters before and after COVID-19. Children 2022, 9, 151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ali, A.M.; Al-Amer, R.; Atout, M.; Ali, T.S.; Mansour, A.M.H.; Khatatbeh, H.; Alkhamees, A.A.; Hendawy, A.O. The Nine-Item Internet Gaming Disorder Scale (IGDS9-SF): Its Psychometric Properties among Sri Lankan Students and Measurement Invariance across Sri Lanka, Turkey, Australia, and the USA. Healthcare 2022, 10, 490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beck, J.G.; Grant, D.M.; Read, J.P.; Clapp, J.D.; Coffey, S.F.; Miller, L.M.; Palyo, S.A. The impact of event scale-revised: psychometric properties in a sample of motor vehicle accident survivors. J Anxiety Disord 2008, 22, 187–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Creamer, M.; Bell, R.; Failla, S. Psychometric properties of the Impact of Event Scale - Revised. Behav Res Ther 2003, 41, 1489–1496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Craparo, G.; Faraci, P.; Rotondo, G.; Gori, A. The Impact of Event Scale - Revised: psychometric properties of the Italian version in a sample of flood victims. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat 2013, 9, 1427–1432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eid, J.; Larsson, G.; Johnsen, B.H.; Laberg, J.C.; Bartone, P.T.; Carlstedt, B. Psychometric properties of the Norwegian Impact of Event Scale-revised in a non-clinical sample. Nord J Psychiatry 2009, 63, 426–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Asukai, N.; Kato, H.; Kawamura, N.; Kim, Y.; Yamamoto, K.; Kishimoto, J.; Miyake, Y.; Nishizono-Maher, A. Reliability and validity of the Japanese-language version of the impact of event scale-revised (IES-R-J): four studies of different traumatic events. J Nerv Ment Dis 2002, 190, 175–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gargurevich, R.; Luyten, P.; Fils, J.F.; Corveleyn, J. Factor structure of the Impact of Event Scale-Revised in two different Peruvian samples. Depress Anxiety 2009, 26, E91–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morina, N.; Böhme, H.F.; Ajdukovic, D.; Bogic, M.; Franciskovic, T.; Galeazzi, G.M.; Kucukalic, A.; Lecic-Tosevski, D.; Popovski, M.; Schützwohl, M., et al. The structure of post-traumatic stress symptoms in survivors of war: confirmatory factor analyses of the Impact of Event Scale--revised. J Anxiety Disord 2010, 24, 606–611. [CrossRef]

- Davey, C.; Heard, R.; Lennings, C. Development of the Arabic versions of the Impact of Events Scale-Revised and the Posttraumatic Growth Inventory to assess trauma and growth in Middle Eastern refugees in Australia. Clinical Psychologist 2015, 19, 131–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, A.M.; Al-Amer, R.; Kunugi, H.; Stănculescu, E.; Taha, S.M.; Saleh, M.Y.; Alkhamees, A.A.; Hendawy, A.O. The Arabic version of the Impact of Event Scale – Revised: Psychometric evaluation in psychiatric patients and the general public within the context of COVID-19 outbreak and quaran-tine as collective traumatic events. Jounal of Personalized Medicine 2022, 12, 681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ali, A.M.; Ahmed, A.H.; Smail, L. Psychological Climacteric Symptoms and Attitudes toward Menopause among Emirati Women. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 5028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ali, A.M.; Hori, H.; Kim, Y.; Kunugi, H. The Depression Anxiety Stress Scale 8-items expresses robust psychometric properties as an ideal shorter version of the Depression Anxiety Stress Scale 21 among healthy respondents from three continents. Front Psychol 2022, 13, 799769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ali, A.M.; Alkhamees, A.A.; Hori, H.; Kim, Y.; Kunugi, H. The Depression Anxiety Stress Scale 21: Development and Validation of the Depression Anxiety Stress Scale 8-item in Psychiatric Patients and the General Public for Easier Mental Health Measurement in a Post-COVID-19 World. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 10142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ali, A.M.; Hendawy, A.O.; Al-Amer, R.; Shahrour, G.; Ali, E.M.; Alkhamees, A.A.; Ibrahim, N.; Ahmed, A.H.; Lamadah, S.M.T. Psychometric evaluation of the Depression Anxiety Stress Scale 8 among women with chronic non-cancer pelvic pain. Scientific Reports 2022. accepted. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- King, D.W.; Orazem, R.J.; Lauterbach, D.; King, L.A.; Hebenstreit, C.L.; Shalev, A.Y. Factor structure of posttraumatic stress disorder as measured by the Impact of Event Scale–Revised: Stability across cultures and time. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy 2009, 1, 173–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, G.F.; Shi, W.; Elhai, J.D.; Montag, C.; Chang, K.; Jackson, T.; Hall, B.J. Gaming to cope: Applying network analysis to understand the relationship between posttraumatic stress symptoms and internet gaming disorder symptoms among disaster-exposed Chinese young adults. Addictive Behaviors 2022, 124, 107096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Flory, J.D.; Yehuda, R. Comorbidity between post-traumatic stress disorder and major depressive disorder: alternative explanations and treatment considerations. Dialogues Clin Neurosci 2015, 17, 141–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morina, N.; Ehring, T.; Priebe, S. Diagnostic utility of the impact of event scale-revised in two samples of survivors of war. PLoS One 2013, 8, e83916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kawamura, N.; Kim, Y.; Asukai, N. Suppression of cellular immunity in men with a past history of posttraumatic stress disorder. Am J Psychiatry 2001, 158, 484–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ali, A.M.; Hendawy, A.O.; Elhay, E.S.A.; Ali, E.M.; Alkhamees, A.A.; Kunugi, H.; Hassan, N.I. The Bergen Facebook Addiction Scale: Its psychometric properties and invariance among women with eating disorders. BMC Women’s Health 2022, 22, 99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dalgleish, T.; Power, M.J. Emotion-specific and emotion-non-specific components of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD): implications for a taxonomy of related psychopathology. Behav Res Ther 2004, 42, 1069–1088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salehinejad, M.A.; Azarkolah, A.; Ghanavati, E.; Nitsche, M.A. Circadian disturbances, sleep difficulties and the COVID-19 pandemic. Sleep Med 2021, 91, 246–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Psychiatric patients (N = 168) | Healthy adults (N = 992) | |

|---|---|---|

| No (%) | No (%) | |

| Gender | ||

| Females | 119 (70.8) | 622 (62.7) |

| Males | 49 (29.2) | 370 (37.3) |

| Age (years) | ||

| 18-30 | 87 (51.8) | 448 (45.2) |

| >31 | 81 (48.2) | 544 (54.8) |

| Marital status | ||

| Married | 77 (45.8) | 553 (55.7) |

| Single/widowed/divorced | 91 (54.2) | 439 (44.3) |

| Education | ||

| School degree | 51 (30.4) | 263 (26.5) |

| University degree | 105 (62.5) | 605 (61.0) |

| Post-graduate degree | 12 (7.1) | 124 (12.5) |

| DASS-8 MD (IQR) | 9 (2.0-17.0) | 2 (0.0-7.0) |

| IES-R MD (IQR) | 30.0 (14.0-43.0) | 18.0 (7.0-29.0) |

| Avoidance MD (IQR) | 8.0 (4.0-12.0) | 6.0 (1.0-10.0) |

| Intrusion MD (IQR) | 5.0 (2.0-9.0) | 3.0 (1.0-6.0) |

| Numbing MD (IQR) | 4.0 (2.0-7.0) | 3.0 (0-6.0) |

| Hyperarousal MD (IQR) | 4.0 (2.0-8.0) | 2.0 (0-4.0) |

| Sleep disturbance MD (IQR) | 2.0 (0-5.0) | 0 (0-2.0) |

| Irritability MD (IQR) | 3.0 (0-4.0) | 1.0 (0-3.0) |

| Sample | AUC | SE | AUC 95% CI | Cutoff | Sensitivity | Specificity | Youden index | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IES-R | Sample 1 | 0.86 | 0.03 | 0.80 to 0.92 | 39.5 | 0.85 | 0.73 | 0.58 |

| Sample 2 | 0.91 | 0.02 | 0.87 to 0.94 | 30.5 | 0.87 | 0.83 | 0.70 | |

| Avoidance | Sample 1 | 0.70 | 0.04 | 0.62 to 0.79 | 7.5 | 0.74 | 0.58 | 0.32 |

| Sample 2 | 0.77 | 0.02 | 0.72 to 0.82 | 8.5 | 0.69 | 0.72 | 0.41 | |

| Intrusion | Sample 1 | 0.80 | 0.04 | 0.72 to 0.87 | 6.5 | 0.72 | 0.78 | 0.50 |

| Sample 2 | 0.85 | 0.02 | 0.81 to 0.89 | 5.5 | 0.86 | 0.74 | 0.60 | |

| Numbing | Sample 1 | 0.69 | 0.04 | 0.60 to 0.78 | 5.5 | 0.56 | 0.75 | 0.31 |

| Sample 2 | 0.80 | 0.02 | 0.76 to 0.85 | 5.5 | 0.70 | 0.77 | 0.47 | |

| Hyperarousal | Sample 1 | 0.87 | 0.03 | 0.81 to 0.93 | 5.5 | 0.80 | 0.83 | 0.63 |

| Sample 2 | 0.88 | 0.02 | 0.83 to 0.92 | 4.5 | 0.83 | 0.81 | 0.64 | |

| Sleep | Sample 1 | 0.81 | 0.04 | 0.74 to 0.88 | 3.5 | 0.74 | 0.79 | 0.53 |

| Sample 2 | 0.84 | 0.02 | 0.79 to 0.88 | 2.5 | 0.72 | 0.83 | 0.55 | |

| Irritability | Sample 1 | 0.83 | 0.03 | 0.76 to 0.89 | 1.5 | 0.96 | 0.54 | 0.50 |

| Sample 2 | 0.87 | 0.02 | 0.84 to 0.91 | 3.5 | 0.77 | 0.83 | 0.60 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).