1. Introduction

This work presents the results of an experimental socio-economic study conducted in a shanty town of Messina as part of a systemic urban regeneration and fight against poverty program called Capacity. This multidimensional policy is aimed at expanding of shanty town inhabitants’ substantive freedoms in the main human functioning areas, particularly regarding housing.

The analysis of this experiment’s results, using calculation of individual payoffs over time, has allowed to describe and correlate components of real-choice mechanisms with some other components, not exclusively associated with economic rationality. Changes in functioning and attitudes have been measured through the construction and validation of the ECCA test.

The study has shown that the development of a positive attitude towards the future and the confidence in others are associated with the development of the riskiest option, which is the one that can give the highest pay-off. The paper also illustrates the expected and unexpected outcomes of projects for individuals and the community, as well as the economic benefits for the public administration and the society of a strategy that reduces the reliance on social welfare measures as well as the local control exercised by organized crime.

2.1. Conceptual Framework

This paper proposes an experimental study, which has been developed in Messina as part of a systemic program that is methodologically inspired by human development theories and implemented according to the Capabilities Approach (CA) pioneered by Amartya Sen and Marta Nussbaum, (Sen 1999; Alkire 2005; Robeyns 2006). The program was aimed at overcoming the deprived housing, social and economic conditions of individuals who have lived for decades in Messina. As argued by Trang Pham (2018) the CA can be used as an evaluation framework to evaluate Community Driven Development programs more effectively” which have many similarities with the Capacity urban regeneration program designed by Community Foundation of Messina along with Municipality of Messina and a broad partnership of local actors.

In the CA the freedom to achieve well-being should be understood in terms of people’s capabilities expansion, that is, their opportunity to choose and to be what they have reason to value (Robeyns 2016).

The objective of the study is to analyse the mechanisms of choice in a real CA-based experiment. More precisely, we will analyse the outcomes of the socio-economical experiment and, through the calculation of individual payoffs over time, how some components, not exclusively associated with economic rationality, have influenced actual decision-making mechanisms.

There is now an extensive literature on the need to include elements that are outside the rational sphere when explaining people’s decision-making dynamics (see for example Kahneman 1994; Kahneman et al. 2004). What has just been said is expected to be not only true, but decisive, in local contexts that are trapped under the poverty line. It is indeed plausible to expect people in conditions of extreme deprivation to manifest socio-economic decisions characterized by a high degree of economic irrationality.

Therefore, effective policies that have as beneficiaries/protagonists people in multidimensional poverty conditions, such as the ones we are studying, must be based on more complex anthropological models than reductionist assumptions of perfect rationality.

On these issues, and on the need to adopt complex anthropological approaches as the basis of socio-economic theories, Amartya Sen himself has authoritatively intervened several times (see for example Sen 1977, 1985, 1997).

2.2. Housing and Capability Relationship: A Literature Survey

The concept of well-being is a multidimensional concept (Nussbam,2002), in the sense that it must simultaneously consider several factors that are not necessarily homogeneous to each other. It is not just a matter of income or wealth, but is linked to the ability to have the tools to realise a life project. In this sense, well-being is more correctly linked to capability, that is, to being able to have a standard of living that safeguards the dignity of the human being.

The relationship between housing and capability is in this light central because housing and living are elements that have a relevant and very important weight in the possibility of planning for the long term and more generally one of the elements that determine a basic minimum of dignity. Housing insecurity is one of the elements that most jeopardises the possibility of guaranteeing long-term well-being.

The literature on the relationship between housing and capacitation has therefore undergone considerable development in recent years, also highlighting that while there is a vast literature of a theoretical nature, empirical analyses are a field that has yet to be explored also due to the difficulty of finding robust statistical data.

Fayard et al., (2021), intending to propose a model representing the well-being of individuals using Sen's capability approach (CA), showing that the capability approach can be very useful for decision support, especially if the gap between theory and empirical work is bridged.

In Anand P. et al., (2009), the growing interest in the capability approach is highlighted even though it is limited by the scarcity of statistical data measuring capabilities at the individual level. In particular, it considers a much-discussed concept of normatively desirable capabilities that constitute a good life.

Claassen (2015) discusses the question of whether a capability-based theory of justice should accept a basic “capability to possess property”. Answering this question is crucial to bridging the gap between abstract capacity theories of justice and their institutional implications in real economies.

Quetela et al, (2022), point out that to build resilience, poor households need policies that protect them and help them out of poverty, and that decision-making processes require the involvement of people. Individuals need to be questioned about their perception and management of risks and threats, both in everyday life and in exceptional circumstances. This socially informed, place-specific and multilevel approach makes it possible to identify interventions for poverty reduction by promoting development and cooperation programs that meet people's expectations.

In Alkire S, Foster J., (2011), a new methodology for multidimensional poverty measurement is proposed that consists of an identification method that extends the traditional intersectional and merging approaches, and a class of poverty measures. This paper highlights the significant weight of housing within attempts at multidimensional poverty measurement.

This theme is taken up by Boram Kimhur, (2020) who point out that housing plays a significant role in increasing inequality. Therefore, the debate on the overall evaluation of housing policies should be reviewed in the light of the concept of empowerment. The conclusion of the paper is capacitation-oriented housing policies produce relevant results.

Coates et al. (2015) investigate the connections between housing and quality of life, investigating whether a wide range of capabilities and activities associated with housing can have a detectable impact on housing satisfaction and whether housing satisfaction contributes to overall life satisfaction. The results indicate that dwelling satisfaction is indeed related to overall life satisfaction and that a wide range of different types of variables appear to have an impact on dwelling satisfaction itself.

Very interesting is the work of Irving (2021) that explores the relationship between housing conditions and well-being, using Nussbaum's previously mentioned approach on CA as a basis for analysis. It is based on data from a qualitative study conducted in the UK on the experiences of people residing in privately run hostels in the North of England. The analysis reveals great diversity in terms of the ways in which residents perceive their housing conditions and the impact of these on the performance of key functions, despite all living in similar environmental conditions. This highlights the highly subjective and complex nature of the relationship between housing conditions and well-being. The paper also points out that a more robust understanding of the key factors mediating this relationship is needed if the potential of ca to advance research and evaluation on housing is to be further realised.

Already Carol Mcnaughton Nicholls, (2010), in the context of a survey of homeless people in the UK of homelessness conducted in the UK showed how housing was closely related, albeit in a complex way, to the possibility of getting out of distress, highlighting the role that housing has in enabling a 'well-lived' life.

Haffner et al. (2019) present findings from the RE-InVEST 1 project that aimed to advance both theoretical reflection and empirical testing of the capability approach. The case of people living in absolute poverty in the city of Rotterdam was studied. From the study of this case, it was possible to understand. what were the best opportunities to reduce their housing deprivation, which was a fundamental problem of their situation, demonstrating that the definition of housing policies starting from the definition of the individual's well-being instead of 'paternalistic' policy objectives, which are mostly based on combating monetary deprivation gives better results.

Soiata et al., (2021), carried out an interesting survey through a systematic literature search, on housing-related publications, highlighting the following five strategic conditions: ontological, ideological, institutional, legitimising devices and contingency drawing policy recommendations that go in the direction of the necessity, in order to achieve better results, of a deeper engagement with the people affected by the policies.

Grenwood et al. (2020) demonstrate in the paper how having a homeless service agency improves capacity. Staying within the capacities approach (CA). Homelessness has been defined as a situation of 'capacity deprivation' and the extent to which homelessness services restore or improve capacity is of increasing interest. A large study on homelessness in Europe, conducted in eight countries, investigated homeless people's perceptions of policies to improve their capabilities. Participants engaged in Housing First (HF) programs perceived homeless service agencies as more likely to improve capacity than participants receiving regular policies.

The interesting work of Olive McCarthy et al. (2021), then highlighted the need to improve the financial capacity of social housing tenants and address the root causes of financial exclusion. The conclusion is that more appropriate financial services need to be designed for those on lower incomes.

Several points can be highlighted from this brief literature review:

(a) The relationship between capability and housing is robust and within capability the role of housing is prominent.

b) Housing policies are crucial both for improving the well-being of individuals and for helping them out of destitution.

c) Housing policies must be mediated to achieve better results

d) If it is true that from a theoretical point of view the issue of capacitation has been widely declined from an empirical point of view, further analyses are needed to better understand the functioning of policies aimed at improving capacitation, with reference to housing policies.

The experiment carried out in Messina constitutes an original and innovative attempt at empirical measurement of the effects of social housing policies which aim, by means of accompaniment by external facilitators, to help those who find themselves in a situation of deprivation, not only to resolve their contingent problem linked to housing, but also to reset their own existence, freeing themselves from the logic and contexts of degradation and crime, in order to achieve a higher level of well-being.

In the light of what has been said, we can better position the value of the experiment on innovative social housing policies that has been carried out in the city of Messina and the results obtained.

3.-Methodology

3.1. Social Context and Experiment Design

The focus of the Capacity program, implemented between 2018 and 2021, was the urban regeneration of two housing settlements, the Fondo Saccà and Fondo Fucile slums, in the III district of the Municipality of Messina. The two slums had the highest incidence rate of families with potential economic hardship in the city. School dropouts in the 2nd year 2017/2018 are 10 times higher than the average value for the Region of Sicily (4.1% against 0.4%). The population living in these settlements lived on average 7 years less than the inhabitants of the other areas of the city. 3.7 per cent of deaths occurred during the first months of life and this is 4 times higher. After multiple complaints to the Judiciary in 2018, the Regional Council (19/09/2018) decreed the socio-health and environmental emergency of the two areas.

The systemic urban regeneration and anti-poverty intervention carried out in the city of Messina with the Capacity Program was achieved thanks to co-programming processes between local authorities and the third sector in which the Messina Community Foundation played a central governance role. The multidimensional policy adopted by Capacity (which includes technical and financial services, technological innovation, social mediation, etc.) has aimed at generating alternatives on the most important aspects of people's lives (living, work/income, sociability, knowledge) and expanding the inhabitants' substantial freedom of choice, while respecting environmental sustainability criteria.

Capacity Program was aimed at testing local welfare systems, achieving sustainable development, acting on complex and stock-generating information bases, redistributing material and immaterial wealth in highly degraded areas in a demographically depressed metropolitan area that been under the poverty trap line for years. For this reason, among other things, tests have been made with innovative social housing mechanisms which have enabled people/families in multidimensional conditions of deep poverty to acquire a freely chosen home.

These are contexts where environmental degradation, organised crime control and poor health conditions have led to poverty traps. The hypothesis was that, by significantly increasing the knowledge stocks, relational, trust and material assets (the home owned) of households, and in particular of children, in conditions of severe deprivation, a significant leap in life prospects could be generated along with, as a further impact, a boost to the development of the socio-economic dynamics of the entire community.

During the programming phase of the Capacity Program proposal, an integrated strategy was adopted, with a significant density of interventions based on the principle of concentration and integration of investments (area-based). Capacity program idea was constructed according to approaches capable of structuring correlations among educational systems, welfare systems, economic-productive systems, cultural systems, scientific and technological research, and the social capabilities of the territories.

A multi-pronged policy has been adopted, trying to set as external constraints the logic of maximizing the economic profit of territorial agents, the expansion of the substantive freedoms of the weakest people, the progressive growth of social capital, environmental responsibility and the construction of beauty.

From a functional-operational point of view, Capacity program has adopted, in an interdependent way, a dual focus acting on contexts and individual households via:

- (1)

the creation of quality urban and socio-economic systems, capable of generating alternatives regarding human functions related to dwelling, income/work, sociality and knowledge;

- (2)

the implementation of personalized and community socio-cognitive mediation projects, which have facilitated people who lived in the city’s shanty towns in situations of strong material and cultural deprivation in seizing the new opportunities by choosing those more functional to their gradually increasing well-being..

This operational strategy had previously been the subject of modelling (G. Giunta et al 2014; A. Giunta et al. 2021), evaluation and validation (Giunta and Leone 2014).

The social and urban regeneration pilot project was aimed at experimenting with hybridization of socio-economic contexts policies and practices in order to promote wealth redistribution processes along with the right to a dignified living (to work, to knowledge and to sociality) for the population who has been confined for decades in shanty towns. To analyse the overall description and the complexity of the Capacity program, see the text of Liliana Leone and Gaetano Giunta (2019). Focusing only into the ‘functioning of living’, the experimental socio-economical project proposes two possible alternatives were envisaged for the shanty town dwellers’ right to housing:

- A.

acquisition by the beneficiaries of an owned home thanks to the benefits coming from the establishment of a Personal Capacity Capital (PCC). This instrument consists of a one-off contribution that makes it possible to purchase a house chosen by the beneficiaries themselves. The PCC represents, therefore, in a symbolic and physical way, the concrete possibility to take back one’s own life by co-planning, with the project’s technical and socio-economic operators, paths to regain one’s civil rights on an individual and socio-economic and community level;

- B.

purchase by the Municipality of Messina of housing units on the city’s real estate market and subsequent allocation to the beneficiaries of the project through participatory practices and according to the standards set by the law on residential constructions in Italy and Sicily. In this case, the beneficiaries are considered to be tenants who are required to pay a modest rent;

The PCC is determined as the sum of a percentage of the purchase of the house, which may not exceed 75% of the gross purchase value; the economic estimate, determined by means of a rigorous technical calculation, of the value of the self-recovery activities implemented by the beneficiaries; and the resources needed to transfer the energy efficiency and home automation prototypes resulting from the program’s research measures to the new houses. The total value of the CCP may never exceed €80,000.00.

The PCC is contractually bound to the purchase of the house and is paid directly to the owner of the property from whom the purchase is made.

Beneficiary families could buy their own home using, in part, the PCC, and, for the remaining part, either their own resources or the support of financial services and/or ethical micro-finance instruments consistent with the project policy. The PCC was associated with a legality pact, which was set out, among other things, in the notarial sales deed:

no problems with justice due to convictions for mafia crimes;

housing acquired with the contribution of the PCC cannot be sold for 10 years and in any case for a period not less than the period of amortization of any mortgage taken out;

in case of final conviction of the beneficiary for mafia crimes in the years following the purchase of the house, the ownership will automatically pass to the Municipality Messina.

The concrete possibility for the inhabitants of the Fondo Saccà and Fondo Fucile shanty towns to choose between one of the two options related to living, A or B (it should be noted that since the area was being cleared there was no “stay and choose not to leave” option), was intended as an extension of the substantive freedoms and the freedom of choice of individuals. The possibility of a real option was strongly accompanied and supported by the set of project actions described above, which were intended to transform a theoretical opportunity to a real one, intended to be exploited by households.

3.2.-Model of Beneficiaries

This study’s aim is to analyse the choices of the beneficiaries and to model the beneficiaries’ choice mechanisms in relation to the housing alternatives generated by the Capacity Program and, more specifically, to those identified with the letter A. (purchased by the beneficiaries).

With regard to the first objective, the overall choice outcomes of the real experiment (the Capacity Program) will be shown.

Subsequently, a subgroup will be analysed of beneficiaries of the project living in Messina’s shanty town who have opted to buy a house of their own, benefitting of their personal capability capital and a complementary ethical finance component.

The main aim of this second part of research is to investigate the type of relationship between the choice of buying a home, quantified through the economic value of the pay-off, and a series of attitudes concerning levels of trust, perception of well-being, level of hope, perceptions about health and risks derived from the environment in which one lives. The study hypothesis is that a positive attitude towards the future and confidence in others is associated with developing the choice of the riskiest alternative, but also capable of ensuring the highest pay-off.

The elements that characterize the chosen model are essentially three:

- (1)

A group of agents: the inhabitants of Fondo Saccà shanty town, who are the beneficiaries of the Capacity Program;

- (2)

two possible strategies that coincide with the previously detailed alternatives, A. and B., generated by the Capacity Program;

- (3)

an individual pay-off function that quantifies the usefulness for each possible (alternative) strategy available to the agents.

The developed model has dynamic characteristics, precisely because it is studied over time. Each agent has access to all the information related to the alternatives that can be accessed and to the choices of the other beneficiaries, thanks to the personalized social mediation services mentioned above and to the strong interactions existing in the social group.

Below are the first parameters used in the model:

N= 20 represents the number of individuals/families belonging to a subgroup that, at the time of the interview, lived in the shanty town and that chose option A.

T indicates the entire project period (three years). It should be noted that the survey was conducted by submitting a test after the choice was made (hereinafter called “POST”) and, in general, at the time of purchase of the house. In the same survey, attitudes registered before the choice development were also evaluated (hereinafter referred to as “PRE”). Indicatively, represents the start of the project operations; time corresponds to about one year after the start of the project; time corresponds to about two years after the start of the project operations.

The time analysis makes it possible to understand how individual choices change during the dynamics of the real experiment and how they influence the choices of other agents. For example, if many beneficiaries decide to implement the strategy of “participating with confidence” at time , it is expected that other agents, at the same time still sceptical about fully participating in the project, may change their minds and implement, for example at the time , a more collaborative strategy.

Player pay-offs are estimated using contingent evaluation. Since it is, in fact, a real experiment, and knowing, therefore, the choices made by individuals and the variables that have most influenced their choice, we can proceed through a backwards model. The main reward in the process is the house.

To assess the attitudes towards the future of the beneficiaries, a face-to-face test was administered during an interview to a sample of 20 householders during the last step, when they were about to buy their home thanks to the PCC of the project Capacity. This sample includes only people who chose the alternative A) and bought their own home during the first two years of the project.

The ECCA (Emotional Climate and Consumptions Attitude)

1 test, built and validated as part of the evaluation of the Capacity program (Leone and Giunta 2019, 27-28), was based on the semantic differential and aimed at detecting in a standardized way the perceptions of the prevailing experience in the household and the pre-post choice/purchase variations. The test indirectly detects some human functions: being insecure, poor, confident, unhappy, brave, or rather, on the ‘doing’ side, living in an unhealthy environment or in an inadequate home.

It presented 8 items drawn on a paper in form of a ten-point self-anchored scale. Each respondent rates himself on the continuum. The test aimed to measure attitudes and perceptions at the times , as better defined above.

The Cronbach’s alpha coefficient of the scale’s internal consistency have been calculated and three items were selected in order to obtain a scale with a high coefficient of Cronbach’s α in both the PRE (0.916) and POST (0.709) versions. The final score of the ‘Positive Attitude’ Scale is obtained by adding together the scores of three items: n.1 Happiness; n.2 Trust; n.3 Courage. Finally, we built two measures: the first named Scale of ‘Positive Attitude’ to assess the psychological attitude towards the future and trust in others, the second named ‘healthiness’ based on the value of the item n.7 to assess the perception of healthiness of the current home.

3.4. Payoffs Estimation

To quantify the value of the variables over time, it is necessary to calculate the dynamic pay-offs of the model, and, more specifically, a sort of discount rate with respect to the value of the house:

where:

= conventional value of the house (€ 100,000.00)

= discount rate

= positive attitude coefficient (Trust, Happiness, Courage);

= healthiness coefficient

So, note that: If If, instead

The individual coefficients (

) are calculated as follows:

Where:

We will therefore have that the pay-off is greatest when = 0 and the discount rate is equal to 1;

The pay-off instead will be equal to 0 and therefore will be at a minimum when , since in this case the discount rate will be 0. So, the discount rate will be between 0 and 1:

Clearly, the pay-offs calculated in this way will be different for each agent because, while the value of the house is conventionally chosen as a constant, the discount rates, functions of the variables taken into account, are entirely subjective.

4. Results

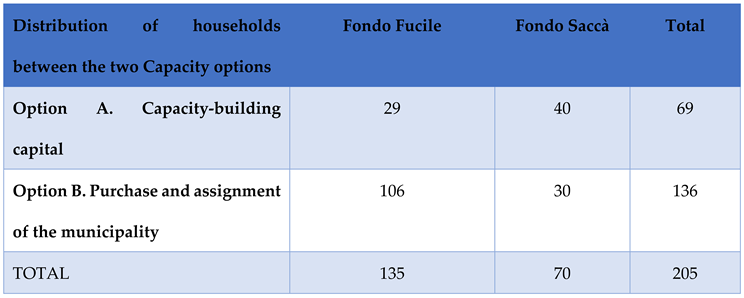

Below are the results of the choices made by the beneficiaries with respect to the alternatives generated by the housing project.

63 non-bankable households had access to regular credit for debt restructuring and home purchase and thus greatly reduced the risk of usury. There were 38 microcredit interventions and 25 loans granted by ethical and social finance partners.

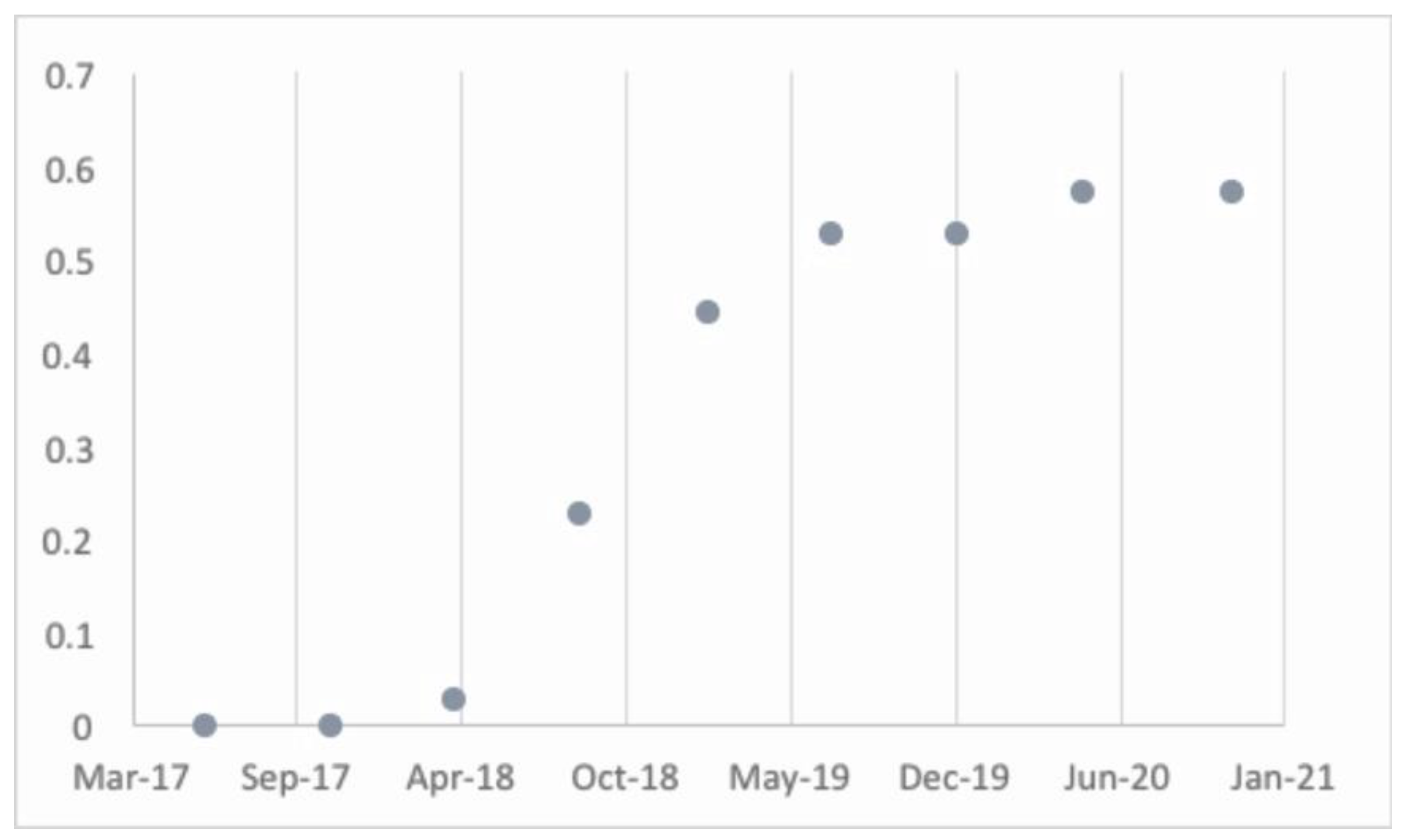

The

Figure 1 shows the cumulative frequency of the beneficiaries who chose the PCC option (Option A.) limited to one of the two slums under intervention: Fondo Saccà. The functional trend is typical of dynamics and thus of learning curves, as will be better discussed in the next chapter

From now on, quantitative analyses will always concern the Fondo Saccà slum. Regarding the investigation of the relationship between the choice of buying a home, quantified through the economic value of the pay-off, and a series of attitudes concerning levels of trust, perception of well-being, level of hope, perceptions about health and risks derived from the environment in which one lives, has been developed a dynamic model over three time periods.

If only one of the beneficiaries had decided to undertake particularly violent demonstrative actions, which are common in the shanty towns of the city (e.g. squatting of the houses built under the Capacity pilot, or other), there would be a high risk of the project being interrupted by the local authority or by the co-financing bodies, first of all the Italian Government’s Prime Minister’s Office.

The dynamic in its preliminary phase, was a simultaneous action, i.e. all agents choose their strategy simultaneously. The various socio-economic agents involved in the process came to a coalition agreement, determined by the fact that most of them considered it useful to explore the project’s process, to understand if there were real chances of achieving the announced objectives.

The dynamics of choices in the second phase were sequential, in fact not all beneficiaries chose at the same time.

Once the continuity of the project was guaranteed, the individual agents i could adopt one of the two strategies available to them i.e. continue to cooperate with confidence (A.) or with low confidence (B.). In addition, since the dynamic process and the pay-off function were based on the time T, one could study how players’ choices varied within the three times .

Below is the calculation of pay-offs (

Table 2), with values in euros, of the N agents taken into consideration:

The data in the

Table 2 have been calculated by obtaining the parameters in formulas (1) and (2), necessary to calculate the discount rates, through the decoding of the test submitted to the players, i.e. to the inhabitants of the shanty towns, at time

t0,

t1 and t2.

As it can be seen from the pay-off table of the subgroup of beneficiaries examined, of these, 8 have made the decision at time and the other 12 at time. This result shows how many people were initially sceptical about the actual viability of such an alternative, or at least showed fear in facing such a radical change in their lives. So, 12 players showed a wait-and-see tactic, allowing themselves to be positively influenced by the moves of the other beneficiaries who first believed in the project’s possibilities.

Another evidence that stands out immediately from the table above concerns the value of pay-offs, which, at the time of the purchase choice, changes scale, showing a positive leap in its numerical value. From an analytical point of view, this result is determined by the rapid growth of subjective variables that influence people’s choices: positive attitude coefficient (Trust, Happiness, Courage) and healthiness coefficient.

The case identified with the number 15 is conditioned by the healthiness coefficient, which, due to the health conditions of the beneficiary, determines an overall high value of the coefficient , maintaining a small value of the discount rate and therefore of the pay-off over time, despite the positive attitude coefficient signals a gradual full confidence and adherence to the initiative.

5. Discussion

The aim of the study was to verify whether the development of a positive attitude towards the future and the growth of bonds of trust towards others would contribute to the development of choices regarding dwelling. In particular, the decision-making processes concerning the purchase of a house by the inhabitants of a shanty town of in the city of Messina in southern Italy have been studied. The purchase decision, although substantially supported by financial help and social-technical and financial advisory and mediation, was indeed the riskiest alternative. At the same time, this option was the one capable of guaranteeing the highest pay-off and ensuring a property stock available for future generations. Housing is a core and self-evident capability that allows a person to expand other capabilities such as education and health of all household members (Kimhur 2019).

The financial cost of the investment in the case of the purchase decision is quite high, especially when compared to disposable income, which hardly exceeds 1,000 euros net per month. Analysing the data of the loans requested for the purchase, an average value of 206 euros comes out, with an average duration of 8.5 years. 206 euros is about 20 per cent of disposable income. The alternative of choice (subsidised rent) envisaged an average cost of 75 euro, largely amortised by the lower incidence of taxation and the zeroing of extraordinary maintenance costs, which would be borne by the municipality of Messina. The data that emerges is that the choice of investing in the purchase is, from a monetary point of view, the least economically advantageous choice in the short term, because it means accepting a substantial reduction in one's disposable income, which, since it is close to the poverty threshold, entails the need to reduce some essential consumption. The rational choice of a low-income individual is to give greater weight to the possibility of consumption in the short run, in spite of the possibility of consumption in the long run. The choice of most agents to invest in purchasing therefore stands outside the traditional concept of rationality of a strictly economic nature, suggesting that the decision sphere has certainly had a rational component, but it has also been linked to other factors. The decision-making mechanisms were structured around an 'object mediation' (the house) and have certainly been conditioned by a psycho-social dimension (needs, beliefs) and by a psychological dimension built around a dynamic and personal non-balance that oscillated between the desires, or rather the new desires, and the fears of each individual. The weight that everyone has attributed to his or her own fears and desires, expectations and needs, with respect to the real prospect of coming out of poverty and deprivation and going to live in a chosen house, potentially owned, has certainly depended on personal conditions (for example, reference is made to involvement in criminal contexts) and environmental conditions (for example, healthiness). At the same time, and this appears to be of particular interest, the decision-making mechanisms have proved to be strongly correlated with the dynamic evolution of trust and perception of the physical and relational microclimate, continuously modified by the project’s actions and interactions aimed at creating new stocks of relational assets, knowledge, including technical and financial knowledge, and by community relations within the group of beneficiaries.

Those who have chosen to buy their own home have exceeded the individual pay-off threshold of about 90,000 Euros and have redesigned many social functions (Leone and Giunta 2019). We are referring, for example, to the processes and skills needed to find the resources complementary to the PCC (e.g.: activation of microcredit) to make the purchase of a house possible. Among the people who exceeded the pay-off threshold value, in fact, paths of financial inclusion have been developed, thanks to the project’s ethical finance partners, as well as the abandonment of illegal labour, thanks to the coaching of social mediators. Abandoning illegal labour was necessary to access financial services and thus to achieve the goal of a home ownership. The need to develop long-term family planning for the first time has structurally changed the concept of time in many beneficiaries. In the same way, the possibility of monetizing the self-restoration of new housing has led many beneficiaries to re-evaluate their manual skills, with positive consequences in terms of self-esteem.

The fact of generating viable alternatives for people, has pushed the beneficiaries to modify in an evolutionary sense their outlook and desires and, therefore, also the sphere of real expectations, experiencing a paradigmatic leap in the dynamics of change.

The preliminary phase, as already mentioned, was characterized by a coalition agreement among the inhabitants, which allowed the Capacity beneficiaries to access the alternative measures provided by the project and therefore to be able to choose between the different opportunities it generated. This coalition agreement was reasonable because the Fondo Saccà shanty town was not included in the city’s recovery plans and therefore the individual prior pay-offs, i.e. in the run-up to the start of the project, can be considered substantially 0 for all participants. In addition, the strong demand for healthiness has led to a sufficient basic level of cooperation to allow the process to begin. The above-mentioned average life expectancy data (Leone and Giunta 2019; Mondello 2020) and the results of the interviews with the beneficiaries give quantitative elements, making it possible to state that the need for health was perhaps the most important variable in determining the choice to join the project.

This rational evidence and the expectation, though weak, or rather initially disillusioned, of a possible growth of the individual pay-off over time has substantially consolidated agreement and allowed the dynamic process to begin.

Of course, the way the value of the individual beneficiaries’ pay-offs evolved, and, therefore, the conclusion reached by the real experiment, critically depended on the evolution of the trust factor, the cultural and social changes that this factor has nurtured, the project’s lawfulness constraints and also on the imitative effects that have taken place during the dynamic.

By way of example, at the time of the interview one of them stated: “...Almost everyone in my neighbourhood has the house now, but beforehand they were suspicious, they thought they were going to get screwed...”.

The buying choice model, which showed (

Figure 1) an evolutionary dynamic of learning, suggests how such a real experiment can be modelled through the game theory. In fact, in general,

a game (Morgenstern and Von Neumann 1944), just like the project, is characterized by three elements:

- (1)

a set of players. In our case the inhabitants of the shanty town, the beneficiaries of the Capacity Program;

- (2)

a set of strategies available to each player. In our case the strategies coincide with options A. and B. generated by the Capacity Program and detailed above;

- (3)

a pay-off for each player, namely the winnings for every possible end of the game and therefore for every (alternative) strategy available to the player.

The case at hand seems to have all the typical features of an evolutionary game (McKenze 2019), at the basis of which, however, there are no pure rationality hypotheses.

People’s choices are based, as widely discussed, on “environmental”, not individual dynamic balances; more precisely, on collective dynamics (Aoki 2001). If people perceive, around them, contexts dominated by hawks, it is easier for choices to be trapped by fears and needs; if, on the contrary, they perceive contexts dominated by doves, i.e. warm, supportive, then mechanisms of sharing, cooperation and openness towards the future, they are more easily triggered. Therefore, the perception of contexts, which evolves along learning curves, affects the choices of individuals, and thus the local social and economic dynamics.

The policy which inspired Capacity has surely produced structural changes in people’s living conditions. (Leone and Giunta 2019, 74). This project represents an experiment in social innovation explicitly based on the capability approach (Chiappero-Martinetti et al. 2017; Howaldt, Jurgen, and Schuarz 2017; Bellucci, Biggeri and Testi 2017).But, we must also mention some of the limitations of the work and possible future in-depth studies: the experimentation has been concomitant with the implementation of the city’s urban regeneration program, which, by its very nature, is a complex path from a political and operational point of view and presents several management uncertainties. Research in the field had to adapt to respect for privacy, time constraints, feasibility and opportunity limitations. The optimal solution would have been to also test contrary hypotheses on the other sample of citizens who chose not to buy their own home. However, with these households it was only possible to carry out field interviews at a stage prior to the allocation of social housing, without being able to detect attitudes before and after the purchase decision.

6. Conclusions

In this socio-economic experiment there is a clear overcoming of the dilemma of urban poverty policies faced by European cities and policymakers about to what extent to invest into poor people or into poor places and what type of interventions to choose (Tosics 2019). Although Capacity is an area-based policy with a focus on specific geographic unit and very poor neighbourhoods, called Fondo Saccà and Fondo Fucile, the main actions are not only ‘hard measures’, such as physical demolition and renovation or improved social infrastructures, but also a mix of strategies aimed at enhancing the freedom of choice and capabilities of people living in poverty. In this program, the people are not forced to change their house according to the choice of local housing agency, but they can buy their house in the free market.

The project outcomes give us clear indications in order to operationalize the capability approach in housing policies (Coates et al. 2015). The policy indications that can be drawn from this experiment relate in particular to how managing housing emergencies typical of the outskirts in large urban centres. Thanks to the adoption of a solution based on the transfer of a stock of resources for the direct benefit of households in extremely difficult housing conditions, the traditional instruments entrusted to temporary accommodation facilities or public housing with capped rents have been overcome. The constraints placed on the allocation of these resources and the adoption of the innovation strategy underpinning Capacity are such that the wider dissemination, on a larger scale and in other contexts or targets, of the experimentation presented in the article should be thoroughly and carefully considered.

Indeed, not only management and social welfare services costs have been reduced, but this has also initiated expansion processes of individuals’ capabilities on different dimensions of living, knowledge, health and sociality, and some mechanisms typical of poverty trap conditions have been curtailed.

Moreover, the economic-social innovations introduced by the Capacity Program in the real experiment developed in Messina, allow a significant expansion of the beneficiaries’ capabilities, and also ensure sustainability over time. They have proved to be much more effective and efficient for the public welfare system and have generated significant positive impacts on the more complex socio-economic dynamics of an area characterized by extreme inequalities.

The results of the real experiment seem to confirm what was predicted by the model-theoretic study, which among other things inspired Capacity's mechanisms (A. Giunta et al, 2021). The study, based on numerical simulations of economic agents interacting according to random algorithms, showed the existence of two macroscopic phases characterizing socio-economic dynamics, depending on the initial distribution of wealth stocks, separated by a threshold region. The simulations predict that for initial values of wealth stock, above the threshold values, the economic system will evolve towards configurations characterised by a progressive concentration of wealth and thus a few dominant attractor nodes. In such phase, economic dynamics will progressively become trapped. Conversely, for maximum values of wealth stock below the transition region, the economic system activates/re-activates durable random walk dynamics.

The Capacity Program made it possible to redefine the initial conditions of wealth endowment of the territorial socio-economic system, thus reactivating its dynamics. Choosing with confidence has made fruitful a policy that can rightly be reread as a sort of exogenous shock capable of determining a significant redistribution of material wealth (home ownership), knowledge and social capital in favour of the poorest and most depressed. The process has allowed the system to be relocated to the sub-critical phase and thus overcome poverty trap trajectories.

A promising outcome of the study relates to the preliminary results discussed above, which connect social justice and CA theories with game theory, and which will be the subject of a further theoretical work. Game theory, in fact, appears to be a conceptually adequate tool to model working hypotheses based on CA, and therefore on the generation of alternatives regarding the main areas of human functioning, precisely because it allows to analyse choice mechanisms, and the mutual influence processes between beneficiaries/players, and more generally between them and the external environment, and the consequent evolutionary dynamics of personalized learning.

References

- Alkire, S. 2005. “Measuring the freedom aspects of capabilities”. Paper Global Equity Initiative, Harvard University.

- Alkire S, Foster J., 2011, Counting and multidimensional poverty measurement, Journal of Public Economics, ISSN 0047-2727 Volume 95, Issues 7–8, August 2011, Pages 476-487. [CrossRef]

- Paul Anand P., et.al. (2009): The Development of Capability Indicators, Journal of Human Development and Capabilities, 10:1, 125-152. [CrossRef]

- Aoki, M. “Modeling Aggregate Behavior and Fluctations in Economics”. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2001. [CrossRef]

- Gobillon A. N., L, Goffette-Nagot F., and Wolman H.. “Housing Economics and Urban Policies”. Annals of Economics and Statistics, 130, (2018):35-38. [CrossRef]

- Bellucci, M., M. Biggeri, and E. Testi. “Enabling Ecosystems for Social Enterprises and Social Innovation: A Capability Approach Perspective”. Journal of Human Development and Capabilities 18 (2) (2017). [CrossRef]

- Blau, D. M., N. L. Haskell, and D. R. Haurin. 2019. “Are housing characteristics experienced by children associated with their outcomes as young adults?” Journal of Housing Economics, 46 101631. [CrossRef]

- Chiappero-Martinetti, E., C. Houghton Budd, and R. Ziegler. 2017. “Social Innovation and the Capability Approach—Introduction to the Special Issue”, Journal of Human Development and Capabilities, 18:2, 141-147, 2017. [CrossRef]

- Claassen T. (2015) The Capability to Hold Property. Journal of Human Development and Capabilities, Taylor & Francis Journals, vol. 16(2), pages 220-236, May. [CrossRef]

- Coates, D., P. et al.. 2015. “A capabilities approach to housing and quality of life: The evidence from Germany”, Open Discussion Papers in Economics, The Open University”, Economics Department, Milton Keynes, 78. Available at: https://www.econstor.eu/handle/10419/147529.

- Fayard N., Mazri,C., TsoukiàsIs A, 2021,. the Capability approach a useful tool for decision aiding in public policy making? Dauphine University Paris, Laboratoire d’Analyses et Modélisation de Systèmes pour l’Aide à la Décision UMR 7243, CAHIER DU LAMSADE 398. [CrossRef]

- Galster, G., D.E. Marcotte, and M.B. Mandell. 2007. “The Impact of Parental Homeownership on Children's Outcomes during Early Adulthood.” Housing Policy Debate 18(4):785-827. [CrossRef]

- Giunta A. 2019. “Implementazione client-server di un simulatore di economia chiusa”. Thesis degree, Messina: Messina University.

- Giunta, A., G. Giunta, D. Marino, and F. Oliveri. 2021. “Market behaviour and evolution of wealth distribution: a simulation model based on artificial agents”. Mathematical and Computational Applications. [CrossRef]

- Giunta, G., and L. Leone. 2014. Sviluppo è coesione e libertà: Il caso del distretto sociale evoluto di Messina, [Development is cohesion and freedom: The case of the evolved social district of Messina]. Messina: HDE Civil Economy.

- Giunta, G., G. Giunta, L. Leone, D. Marino, G. Motta, and A. Righetti. 2014. “A Community Welfare Model Interdependent with Productive, Civil Economy Clusters: A New Approach.” Modern Economy, 5(8). [CrossRef]

- Gobillon, L., Goffette-Nagot, F. 2018. “Introduction: Housing Economics and Urban Policies”. Annals of Economics and Statistics, 130, (2018):35-38. [CrossRef]

- Haffner, M., & Elsinga, M., 2019,. Housing deprivation unravelled: application of the capability approach. European Journal of Homelessness, 13(1), 13-28, ISSN 2030-3106.

- Harkness, J.M., and S.J. Newman. 2003. ‘Effects of homeownership on children: the role of neighborhood characteristics and family income’, Economic Policy Review, 9(2): 87-107.

- Haurin, D.R. 2012. Home Ownership. “The impact of homeownership on child and teenage Outcome”. International Encyclopedia of Housing and Home. [CrossRef]

- Helderman, A., and C.H. Mulder. 2019. “Intergenerational Transmission of Homeownership: The Roles of Gifts and Continuities in Housing Market Characteristics.” Urban Studies 44(2):231-247,. [CrossRef]

- Howaldt, J., and M. Schwarz. 2017. “Social Innovation and Human Development—How the Capabilities Approach and Social Innovation Theory Mutually Support Each Other”. Journal of Human Development and Capabilities, 18 (2): 1-18. [CrossRef]

- Irving A., 2021,: Exploring the relationship between housing conditions and capabilities: a qualitative case study of private hostel residents, Housing Studies, ISSN: 0267-3037. [CrossRef]

- Kaas, L., G. Kocharkov, and E. Preugschat. 2019. “Wealth Inequality and Homeownership in Europe”. Annals of Economics and Statistics , 136, 27-54. [CrossRef]

- Kahneman, D. 1994. “New Challenges to the Rationality Assumption”. Journal of Institutional and Theoretical Eco- nomics (JITE), 150(1), 18-36. https://www.jstor.org/stable/40753012. [CrossRef]

- Kahneman, D., A.B. Krueger, D. Schkade, N. Schwarz, and A. Stone. 2004. “Toward National Well-Being Accounts”. The American Economic Review, 94(2), 429-434. [CrossRef]

- Kimhur, B. 2019. “How to Apply the Capability Approach to Housing Policy? Concepts, Theories and Challenges”. Theory and Society, 37:3, 257-277. [CrossRef]

- Kimhur B. ,2020, Capabilities, Housing, and Basic Justice: An Approach to Policy Evaluation Reply, - HOUSING THEORY & SOCIETY, ISSN: 1403-6096.

- Leone, L., and G. Giunta. 2019. Riqualificazione urbana e lotta alla povertà: l’approccio delle capacitazioni nella valutazione di impatto del progetto Capacity [Urban regeneration and poverty fight: the capacity approach in the Capacity project impact assessment]. Messina: HDE Civil Economy.

- McCarthy O. et al., 2021, Financial Inclusion Among Social Housing Tenants, Cluid Housing.

- McKenzie, AJ. Evolutionary Game Theory, The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Summer 2019 Edition), Edward N. Zalta (ed.), Accessed 22 december 2020. https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/sum2019/entries/game-evolutionary.

- Mcnaughton Nicholls C., 2010, Housing, Homelessness and Capabilities, Housing, Theory and Society, 27:1, 23-41, ISSN: 1403-6096. [CrossRef]

- Mela, A., and A. Toldo. 2019. “Socio-Spatial Inequalities in Contemporary Cities, Springer Briefs in Geography”. [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, Ann, and Macció, J. 2018. “Evaluation of the effect of emergency housing on multidimensional poverty: The case of TECHO-Argentina”. Presented at the annual conference of the HDCA, Buenos Aires, Argentina. .

- Mondello, S. 2020. “Mapping urban segregation and health disparities: a case study of two slums in Messina (Sicily)”. Presented at 16th World Congress on Public Health, 12-16 ottobre.

- Morgenstern, O., and J. Von Neumann. 1944. The Theory of Games and Economic Behavior, Princeton University Press. [CrossRef]

- Musterd, S., S. Marcińczak, M. van Ham, and T. Tammaru. 2017. “Socioeconomic segregation in European capital cities. Increasing separation between poor and rich” Urban Geography, 38:7, 1062-1083. [CrossRef]

- Nussbaum M., 2002, Capabilities and Social Justice, International Studies Review, Volume 4, Issue 2, Pages 123–135. [CrossRef]

- Pham, T. 2018. “The Capability Approach and Evaluation of Community-Driven Development Programs.” Journal of Human Development and Capabilities, 19(2), 166-180. [CrossRef]

- PON Metro 2014-2020, Multi-fund National Operational Program Metropolitan Cities.

- Quétela C. R. et al, 2021, On the Nature and Determinants of Poor Households’ Resilience in Fragility Contexts. JOURNAL OF HUMAN DEVELOPMENT AND CAPABILITIES, VOL. 23, NO. 2, 252-269. [CrossRef]

- Robeyns, I. 2006. “The Capability Approach in Practice” The Journal of Political Philosophy, 14(3): 351-376. [CrossRef]

- Robeyns, I. 2016. "The Capability Approach", The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Winter 2016 Edition), Edward N. Zalta (ed.).

- Seiler, Y. , and G. Wanzenried. 2019. “Are Homeowners Happier than Tenants? Empirical Evidence for Switzerland”, Wealth(s) and Subjective Well-Being, Social Indicators Research Series 76:305-321. [CrossRef]

- Sen, Amartya. 1977. “Rational Fools: A Critique of the Behavioural Foundations of Economic Theory”, Philosophy and Public Affairs 6(4): 317-344. https://www.jstor.org/stable/2264946.

- Sen, Amartya. 1985. “Rationality and Uncertainty”. Theory and Decision 18: 109-27. [CrossRef]

- Sen, Amartya. 1997. “Maximization and Act of Choice”. Econometrica 64(4): 745-780. [CrossRef]

- Sen Amartya. 1999. Development as freedom (1st ed.). New York: Oxford University Press.

- Soaita A. M. et al., 2021, Policy movement in housing research: a critical interpretative synthesis, Housing Studies ISSN: 0267-3037. [CrossRef]

- Tosics, I. 2019. The dilemma of fighting urban poverty: invest into poor people or into poor places? URBACT EU Operational Program, 3 July 2019. Accessed 22 december 2020. https://urbact.eu/dilemma-fighting-urban-poverty.

| 1 |

For more information about the methodology for the construction of the ECCA Test and the interviews see chapter 2 of Leone Liliana ‘La valutazione del progetto: obiettivi, quesiti valutativi, approcci e metodi’ In: Leone Liliana, Giunta Gaetano (2019). |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).