Introduction

Malaria is a life-threatening protozoan disease caused by parasites of the genus Plasmodium and transmitted through the bite of an infectious female anopheles’ mosquito. Malaria during pregnancy is a major public health problem not only to the pregnant mother but also her fetus if not prevented or treated. It is estimated to affect 228 million people globally with an estimated incidence rate of 57 cases per 1000 population at risk (Zekar & Sharman, 2020) and 435 000 deaths worldwide. The WHO African Region accounts for 94% of all malaria deaths in Africa with pregnant women, children, and immune compromised individuals having the highest morbidity and mortality with Africa bearing the heaviest burden (Thornton, 2020). In 2018, an estimated 11 million pregnant women in Sub-Saharan Africa were infected with malaria which resulted into nearly 900,000 children born with a low birth weight (Zekar & Sharman, 2020). According to a study conducted in Ethiopia it revealed that Uganda has got the highest prevalence rate of malaria among the risk groups at 87.9% compared to other parts of the world (Tegegne et al., 2019).

In Uganda, malaria is the leading cause of morbidity and mortality among the general population especially pregnant women (Kigozi et al., 2016), in all ages accounting for 12.5% of all OPD attendances causing 3,077 deaths in Uganda (Yeka et al., 2012). Despite malaria being endemic in over 95 % of the country, different regions of the country experience varying transmission intensities, some have been historically among the highest in the world (Kigozi et al., 2016). In addition Uganda bears a particularly large burden from the disease which is limited by a lack of reliable data, but it is clear that the prevalence of malaria infection, incidence of disease, and mortality from severe malaria all remain very high (Yeka et al., 2012). The Uganda National Malaria strategic plan set targets by 2015, 85% of pregnant women should receive two doses of IPT or more, by 2017, achieve and sustain protection of at least 85% of the population at risk through recommended malaria prevention strategies among others. All this is to be attained through various activities like: distribution of LLINs, IPT , indoor residual spraying, urban malaria control, larval source management (Health, 2014). Malaria in pregnancy contributes to significant peri-natal morbidity and mortality. Infections are known to cause higher rates of miscarriages, intra uterine demise, premature delivery, low birth weight and neo-natal death (De Beaudrap et al., 2016).

Iganga district is one of the districts in Uganda with a high burden of malaria that’s the prevalence rate at 46.2% in the general population, 78.2% of pregnant women received IPT1, 60.0% for IPT2 and IPT3 more than 64.8% (DHO, 2020). The MOH through the National Malaria Control Programme has put in place guidelines for the minimum service package for all levels of Primary Health Care that’s by 2015, 80% of pregnant women should receive two doses of IPT or more, by 2017, achieve and sustain protection of at least 80% of the population at risk through recommended malaria prevention strategies among others. In addition is the Second National Malaria Strategic Plan (2001-2005) identified IPT as a key intervention that was upgraded to a more comprehensive and integrated package (IPT, case management and use of ITNs) for malaria in pregnancy. However, while the Strategic Plan and guideline exists and being implemented at various health facility that provide ANC in Iganga district, the malaria prevalence is still high at 46.2% in the general population including pregnant women (DHO, 2020). The current level of uptake of IPT and malaria prevalence among pregnant women by age group has not been assessed in Iganga district (District Health Office Report, 2019). Therefore, this study assessed the uptake of intermittent preventive treatment among pregnant women in Iganga district in order to generate evidence-based information to scale up IPT uptake and hence reduce malaria prevalence among pregnant women in the Iganga district.

Methodology

Study Design

The research used a cross-sectional study design that employed quantitative data collection to assess the uptake of IPT and prevalence of malaria for financial year 2019/2020 in nine Public Health Centre IIIs and one Public Health Centre IV. Secondary data from HMIS was obtained and analyzed to assess the uptake of intermittent preventive treatment and the prevalence of malaria among pregnant women was determined using proportions.

Study site

The study was conducted in Iganga District located in Busoga sub-region being bordered by Kaliro District to the north, Namutumba District to the northeast, Bugiri District to the east, Mayuge District to the south, Jinja District to the southwest, and Luuka District to the west. It covers an area of approximately 1,046.75 sqkm with a total population of 408,300 (UBOS projection 2020). Administratively Iganga District Health sector is divided into 3 Health sub-district thus Kigulu North, Kigulu South and Iganga Municipality. It has 50 health centres both public and Private not for Profit thus 2 Hospitals, 1 HC IV, 10 HC IIIs and 36 HC IIs. These HCs form the base from which the population access health services.

Study site

The study was conducted in Iganga District located in Busoga sub-region being bordered by Kaliro District to the north, Namutumba District to the northeast, Bugiri District to the east, Mayuge District to the south, Jinja District to the southwest, and Luuka District to the west. It covers an area of approximately 1,046.75 sqkm with a total population of 408,300 (UBOS projection 2020). Administratively Iganga District Health sector is divided into 3 Health sub-district thus Kigulu North, Kigulu South and Iganga Municipality. It has 50 health centres both public and Private not for Profit thus 2 Hospitals, 1 HC IV, 10 HC IIIs and 36 HC IIs. These HCs form the base from which the population access health services.

Study Population

The study population included pregnant mothers who attended ANC in all public IIIs and IVs in Iganga District.

Sample size

Census of health facilities offering ANC services was done and a total of all the 10 public health facilities (Health centre nine IIIs and one IV) were selected out of the 50 health facilities (both private and public) in Iganga District. All the medical records of pregnant women who met the inclusion criteria were reviewed.

Sampling method and procedures

The patients included were purposively selected basing on having attended ANC with in any of the ten public health facilities (nine Health Centre IIIs and one Health Centre IV) during the financial year 2019 / 2020. It’s because of representation and avoidance of bias, these public health centers were chosen as they are easily accessible and in addition, they offer free ANC services hence high attendance compared to Private Health Centres. Hospital(s) were excluded because they act as referral points hence not representative and biased data. A total of observations about IPT uptake and malaria prevalence among all pregnant mothers who attended ANC in these selected 10 public health facilities for financial year 2019 / 2020 in the HIMS were studied.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

All pregnant women taking IPT during ANC attendance and those laboratory tested for malaria using either RDT or Blood smear (BS) in all the 10 Public Health Centre IIIs and IV accredited to offer ANC services in Iganga district in financial year 2019/2020 were included in the study.

Exclusion criteria

All public health facilities not accredited to offer ANC services in Iganga district. All pregnant women who were attending ANC in Private Health facilities IIIs and IV were excluded from the study. Also pregnant women who attended ANC but didn’t take IPT and clinically diagnosed with malaria with no laboratory confirmatory test results during the study period at the 10 public health facilities IIIs and IV in Iganga district because it wasn’t the researcher’s interest.

Study variables

The independent variables were the age and level of health facility.

Dependent variables

The dependent variable was the uptake of Intermittent Preventive Treatment.

Data collection methods and procedures

A data abstraction form was used to abstract pregnant mother’s information from HMIS forms of the health facilities which compile monthly, quarterly and annual reports which are submitted to the District Biostatician. Data elements captured included; patients’ age, doses of IPT, malaria test results by use of RDT or Blood smear (BS), health facility where the patient was diagnosed. Quantitative data comprised of retrospective review of prospectively collected data of all pregnant women who attended ANC for financial year 2019 / 2020.

Data management and analysis

All the data collected was edited and checked for consistency. The data was entered, cleaned and analyzed in the Microsoft excel version 16 data capture sheet. All the three objectives were determined using frequencies and proportions.

Ethical considerations

Permission to conduct the study was obtained from Makerere University School of Public Health and approval for the study was obtained from Iganga District Health Office and the information obtained was kept confidential by the investigator and anonymity was maintained throughout the study by not attaching any name to all data elements captured.

Dissemination

The report containing the results of this study were submitted as a field study report in partial fulfilment of the award of a Master’s Degree in Public Health of Makerere University. Copies of the report were submitted to Makerere University School of Public Health, Iganga District Health Office, Health facility in-charges and Iganga-Mayuge Demographic surveillance site. Presentations of these results will be made in MakSPH seminar series.

Limitations of the study

This study relied on secondary data extracted from the DHOs HMIS, DHIS2 forms and could have suffered a challenge of inaccuracies and missing data from health facilities. However, this was addressed by comparison with health facility OPD registers and their carbon copies of the HMIS forms to capture missing information that was missing in the DHOs HMIS forms. In addition, since the study relied on secondary data analysis, the researcher was limited with other individual background characteristics (e.g. Education level, cultural valves) and other variables in the conceptual framework which might have an influence on the uptake of IPT.

Results

Proportion of pregnant women who received two or less doses of IPT for FY 2019 / 2020

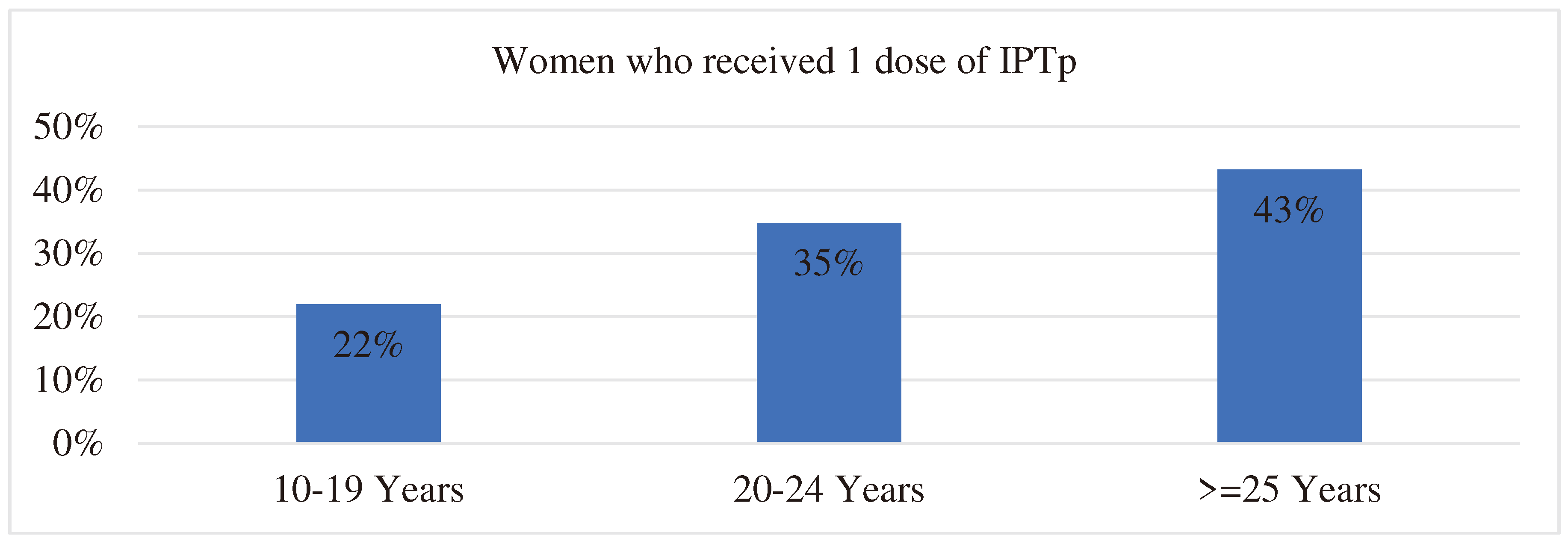

Table 1 below shows the number of pregnant women who received two or less doses of IPT in Health Centre IIIs and IVs in Iganga district. A total of 1671 (25%) of the pregnant women who enrolled for ANC received 2 or less doses of IPT. With 367 (22%) aged 10-19 years, 582 (35%) 20-24 years and 722 (43%) >=25 years.

Figure 1.

Number of women who received two or less doses of IPT.

Figure 1.

Number of women who received two or less doses of IPT.

Proportion of pregnant women who received at least three or more doses of IPT for FY 2019 / 2020

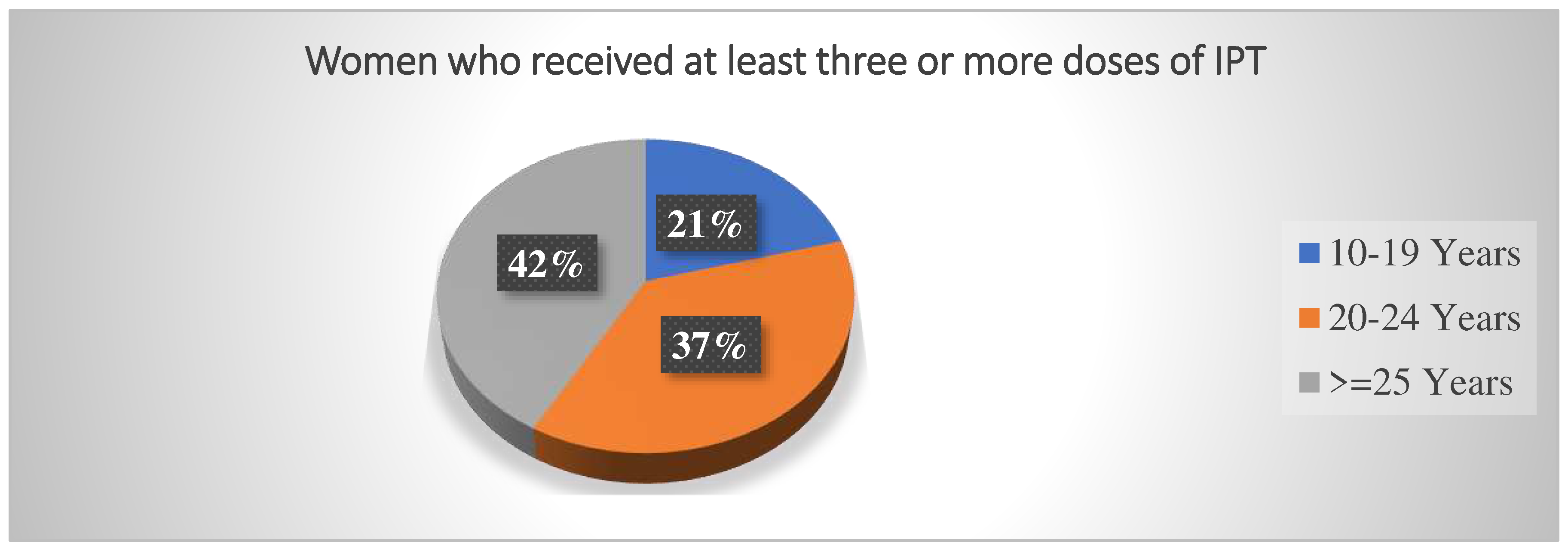

In FY 2019/2020, a total of 3,085 (46%) of pregnant women received at least three or more doses of IPT. The highest proportion was those above 25 years 1288 (42%), those aged 20-24 years 1157 (37%) and finally those aged 10-19 years 640 (21%).

Table 2.

Number of women who received at least three or more doses of IPT.

Table 2.

Number of women who received at least three or more doses of IPT.

| |

10-19 Years |

20-24 Years |

>=25 Years |

| July 2019 to June 2020 |

640 |

1157 |

1288 |

Figure 2.

Number of women who received at least three or more doses of IPT.

Figure 2.

Number of women who received at least three or more doses of IPT.

Prevalence of malaria among pregnant women during FY 2019 / 2020

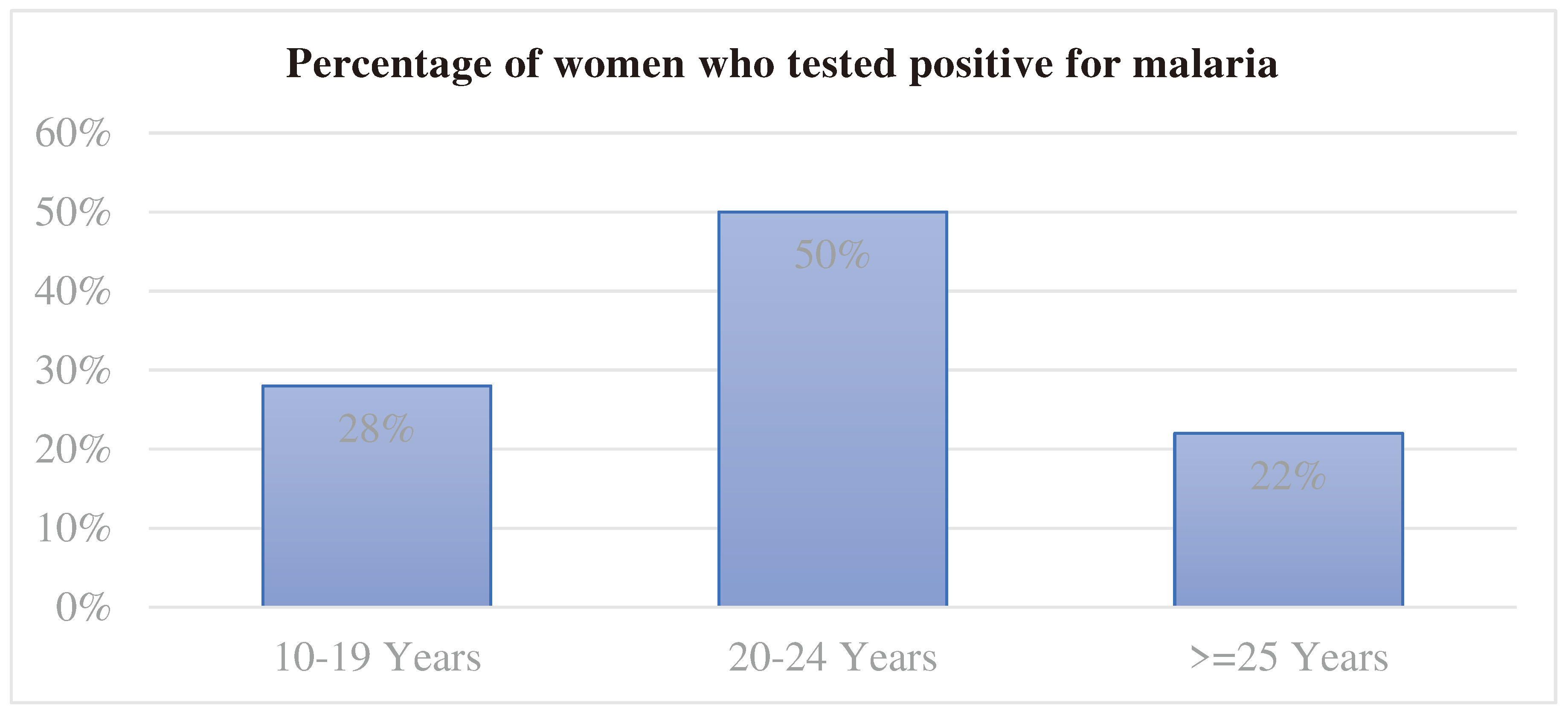

Table 3 below shows pregnant women who tested positive per Health Centre. Nambale H/C III had a high positivity rate of 95.4% among pregnant mothers aged 10-19 years, Bunyiiro H/C III it was 96.1% among 20-24 years and 25>= years the positive rate was highest at Nawandala H/C III.

Figure 3.

Percentage of pregnant women who tested positive for malaria.

Figure 3.

Percentage of pregnant women who tested positive for malaria.

In FY 2019/2020, a total of 3,435 (50%) pregnant women tested positive for malaria. The highest proportion was those aged 20-24 years 1747(50%), those aged 10-19 years 949 (37%) and finally those aged 25 years and above 739 (22%).

Discussion

Proportion of pregnant women who received two or less doses of IPT for F/Y 2019 / 2020

Overall, the study found that 25% women who enrolled for ANC received two or less doses of IPT. These study findings concur with a study done in Tanzania where a smaller number of women received only 1 dose of IPT (Orish et al., 2015). The findings of our study is way below the Uganda National malaria strategic plan target which states it that by 2015, 85% of pregnant women should receive at least three or more doses of IPT or more. The low uptake of IPT may be associated with place of receiving ANC. A study done in East-Central Uganda suggests that women who received ANC from lower level facilities had a 69% less likelihood of receiving optimal doses of IPT and 66% less likelihood of receiving partial doses of IPT than women who received ANC from hospitals (Okethwangu et al., 2019). This could be because in hospitals IPT is mandatory on first visit, there are incentives given like mosquito nets to every pregnant mother (Tackie et al., 2020) and there is a possibility that these pregnant women might lack information about the IPT side effects at the beginning or first visit.

Our study findings also show that majority (43%) of the pregnant women who received two or less doses of IPT were aged 25 years and above. These results are similar to findings in the Uganda Demographic and Health Survey 2016, where older age groups were associated with reduced chances of optimal uptake of IPT that is 3 or more doses (Okethwangu et al., 2019).

Proportion of pregnant women who received at least three or more doses of IPT for F/Y 2019 / 2020

The study findings showed that 46% of pregnant women received at least three or more doses of IPT. Contrary to these findings, a study done in Cameroon showed that a greater number of women 81.7% received three or more doses of IPT (OBI, 2016). The same study shows that uptake of adequate SP dosage varied significantly according to type of medical facility, timing of ANC initiation and number of clinical visits.

Our study findings also show that older age groups above 25 years received three or more doses of IPT (42%) compared to those aged 20-24 years (37%) and those aged 10-19 years (21%). Our study findings concur with a study done by (Martin M.K, 2020) where older age groups were associated with more uptake of IPT. It is therefore imperative that interventions to increase uptake of optimal doses of IPT among pregnant women of older age groups.

Prevalence of malaria among pregnant women attending public facilities in Iganga district for F/Y 2019/2020

The study showed that a total of 3,435 pregnant women tested positive for malaria which brings the prevalence to 50%. Our study findings almost concur with a study conducted in Nigeria where it was found out that the high prevalence of malaria in pregnant women was 45.38% (Yakubu et al., 2018), which is slightly lower than our findings of 50%.This prevalence is high and therefore calls for more efforts in malaria prevention among pregnant women. Our study findings also highlighted the highest prevalence among women aged 20-24 years at 50%. This may be explained by the optimal uptake of IPT and adherence to ANC among pregnant women in older age groups and thus calls for more effort in malaria prevention among younger age groups.

The study also revealed public Health center IIIs to be having the highest positivity rates among other health center levels. These health centers could be having an effective health system in place that is able to screen and detect all the true positives of malaria. This is supported with a study which revealed that the effectiveness of the health system in providing the enabling environment and the integration of the diagnostic tool into routine service delivery is critical to identifying the true malaria positives (Asiimwe et al., 2012).

Recommendations

We recommend Ministry of Health-Uganda to conduct qualitative research on the barriers and facilitators to the uptake of IPT recommended doses among pregnant women. In addition, Iganga district health offices and facility in-charges to design strategies to increase uptake of IPT among pregnant women especially those of younger age groups through sensitization of the public. Lastly, to the Iganga community especially pregnant women to sleep under insecticide treated nets, remove mosquito bleeding sites, and practice good health-seeking behaviors to enable early diagnosis and treatment of malaria to prevent severe malaria with its related complications.

Conclusion

The study showed that the uptake of IPT was low among women of lower age groups and the prevalence of malaria among pregnant women is relatively high. Therefore, the existing prevention and control measures should be strengthened for example health education regarding proper usage of LLIN, application of IRS for controlling the vector and early diagnosis and treatment of pregnant women should be adopted.

References

- Asiimwe, C., Kyabayinze, D. J., Kyalisiima, Z., Nabakooza, J., Bajabaite, M., Counihan, H., & Tibenderana, J. K. (2012). Early experiences on the feasibility, acceptability, and use of malaria rapid diagnostic tests at peripheral health centres in Uganda-insights into some barriers and facilitators. Implementation Science, 7(1), 1-12. [CrossRef]

- Berendsen, M. L., Van Gijzel, S. W., Smits, J., De Mast, Q., Aaby, P., Benn, C. S., . . . Van Der Ven, A. J. (2019). BCG vaccination is associated with reduced malaria prevalence in children under the age of 5 years in sub-Saharan Africa. BMJ global health, 4(6).

- Bouyou-Akotet, M. K., Mawili-Mboumba, D. P., & Kombila, M. (2013). Antenatal care visit attendance, intermittent preventive treatment and bed net use during pregnancy in Gabon. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth, 13(1), 52. [CrossRef]

- De Beaudrap, P., Turyakira, E., Nabasumba, C., Tumwebaze, B., Piola, P., Boum II, Y., & McGready, R. (2016). Timing of malaria in pregnancy and impact on infant growth and morbidity: a cohort study in Uganda. Malaria journal, 15(1), 92.

- DHO. (2020). Iganga District DHIS2 Jan to May 2020 report on malaria indicators. Retrieved from Iganga.

- Dosoo, D. K., Chandramohan, D., Atibilla, D., Oppong, F. B., Ankrah, L., Kayan, K., . . . Amenga-Etego, S. (2020). Epidemiology of malaria among pregnant women during their first antenatal clinic visit in the middle belt of Ghana: a cross sectional study. Malaria journal, 19(1), 1-12. [CrossRef]

- Ejike, B., Ohaeri, C., Amaechi, E., Ejike, E., Okike-Osisiogu, F., Irole-Eze, O., & Belonwu, A. (2017). Prevalence of falciparum malaria amongst pregnant women in Aba South Local Government Area, Abia State, Nigeria. Nigerian Journal of Parasitology, 38(1), 48-52. [CrossRef]

- Health, M. o. (2014). Malaria Reduction Strategic Plan 2014-2020 (UMRSP) Kampala: Ministry of health.

- Kalinjuma, A. V., Darling, A. M., Mugusi, F. M., Abioye, A. I., Okumu, F. O., Aboud, S., . . . Fawzi, W. W. (2020). Factors associated with sub-microscopic placental malaria and its association with adverse pregnancy outcomes among HIV-negative women in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania: a cohort study. BMC Infectious Diseases, 20(1), 1-13. [CrossRef]

- Kigozi, R., Zinszer, K., Mpimbaza, A., Sserwanga, A., Kigozi, S. P., & Kamya, M. (2016). Assessing temporal associations between environmental factors and malaria morbidity at varying transmission settings in Uganda. Malaria Journal, 15(1), 511. [CrossRef]

- Martin M.K, V. K. B., Patrick .N. Bernard.K.Keith. (2020). (Mbonye K. Martin, 2020). Malaria journal.

- OBI, K. M. C. (2016). THE EFFECT OF HEALTH INSURANCE SCHEME ON THE UTILIZATION OF HEALTH CARE SERVICES BY ANGLICAN CHURCH WORKERS IN ANAMBRA STATE. PUBLIC HEALTH.

- Okethwangu, D., Opigo, J., Atugonza, S., Kizza, C. T., Nabatanzi, M., Biribawa, C., . . . Ario, A. R. (2019). Factors associated with uptake of optimal doses of intermittent preventive treatment for malaria among pregnant women in Uganda: analysis of data from the Uganda Demographic and Health Survey, 2016. Malaria journal, 18(1), 250. [CrossRef]

- Orish, V. N., Onyeabor, O. S., Boampong, J. N., Afoakwah, R., Nwaefuna, E., Acquah, S., . . . Iriemenam, N. C. (2015). Prevalence of intermittent preventive treatment with sulphadoxine-pyrimethamine (IPTp-SP) use during pregnancy and other associated factors in Sekondi-Takoradi, Ghana. African health sciences, 15(4), 1087-1096. [CrossRef]

- Tackie, V., Seidu, A.-A., & Osei, M. (2020). Factors influencing the uptake of intermittent preventive treatment of malaria among pregnant women: a cross-sectional study. Journal of Public Health, 1-9. [CrossRef]

- Tegegne, Y., Asmelash, D., Ambachew, S., Eshetie, S., Addisu, A., & Jejaw Zeleke, A. (2019). The prevalence of malaria among pregnant women in Ethiopia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of parasitology research, 2019. [CrossRef]

- Thornton, J. (2020). Covid-19: Keep essential malaria services going during pandemic, urges WHO: British Medical Journal Publishing Group. [CrossRef]

- Umemmuo, M. U., Agboghoroma, C. O., & Iregbu, K. C. (2020). The efficacy of intermittent preventive therapy in the eradication of peripheral and placental parasitemia in a malaria-endemic environment, as seen in a tertiary hospital in Abuja, Nigeria. International Journal of Gynecology & Obstetrics, 148(3), 338-343.

- Wafula, S. T., Mendoza, H., Nalugya, A., Musoke, D., & Waiswa, P. (2021). Determinants of uptake of malaria preventive interventions among pregnant women in eastern Uganda. Malaria journal, 20(1), 5. [CrossRef]

- WHO. (2016). World Malaria Report 2015.

- Yakubu, D., Kamji, N., & Dawet, A. (2018). Prevalence of Malaria Among Pregnant Women Attending Antenatal Care at Faith Alive Foundation, Jos, Plateau State, Nigeria. Noble International Journal of Scientific Research, 2(4), 19-26.

- Yeka, A., Gasasira, A., Mpimbaza, A., Achan, J., Nankabirwa, J., Nsobya, S., . . . Talisuna, A. (2012). Malaria in Uganda: challenges to control on the long road to elimination: I. Epidemiology and current control efforts. Acta tropica, 121(3), 184-195. [CrossRef]

- Zekar, L., & Sharman, T. (2020). Plasmodium Falciparum Malaria: StatPearls Publishing, Jan.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).