Introduction

Henipaviruses pose continuous threat to both animals and humans [

1]. Infectious disease experts have long warned that climate change and environmental damage will increase the risk of the spread of viruses from animals to humans [

2]. Since animal interaction accounts for the transmission of around 70% of all newly identified infectious illnesses [

3]. Climate change contributes to zoonotic outbreaks by altering host-pathogen interactions [

4]. According to the US, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), three out of every four new or emerging infectious diseases in humans are caused by animals [

5]. It is projected that in the upcoming days, the alarming patterns of virus spillovers, would get worse. Almost three years after the identification of the novel SARS-CoV-2 virus in China, a new zoonotic virus has been found in the Shandong and Henan provinces, with 35 cases identified so far [

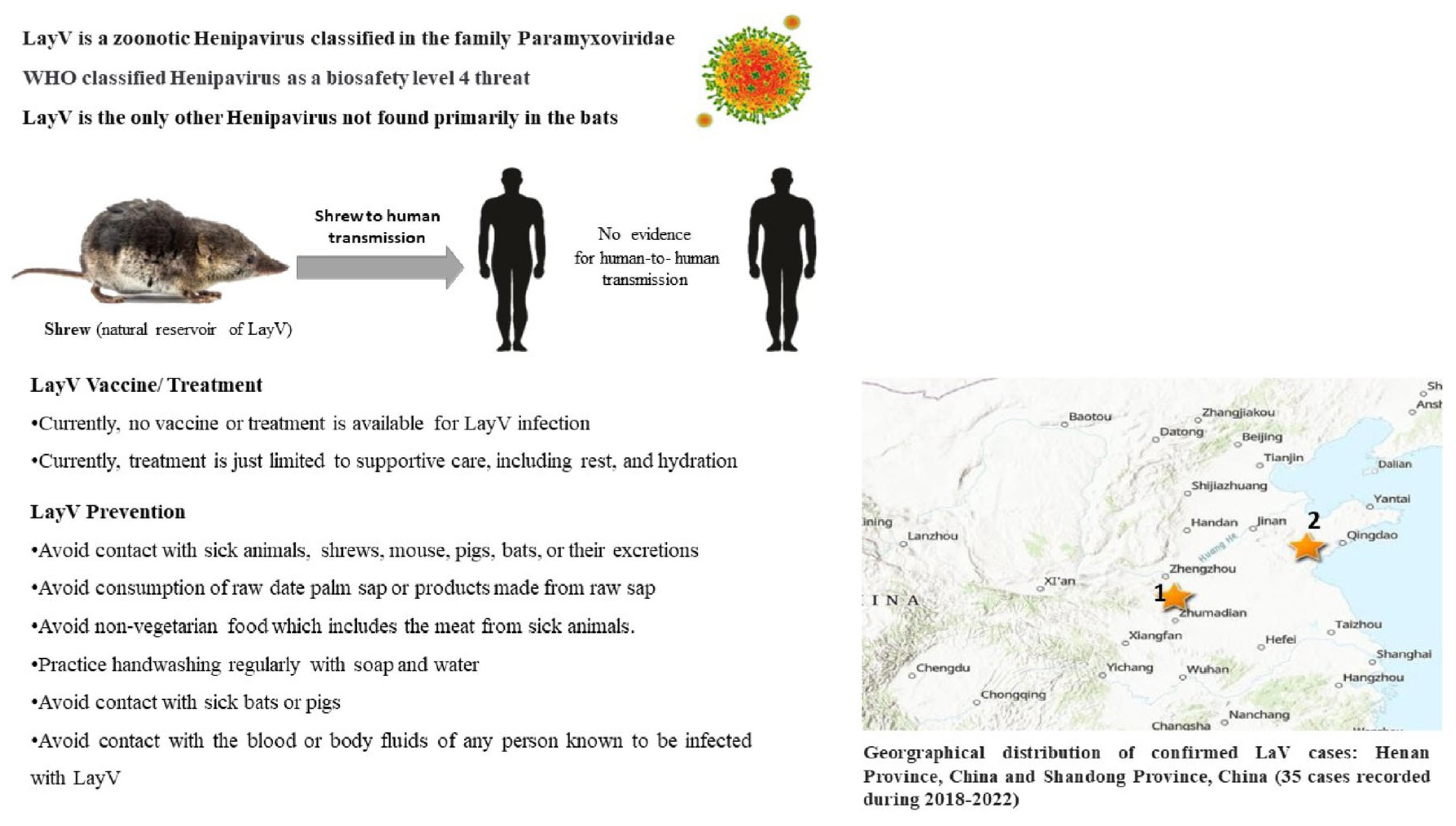

6]. This novel phylogenetically distinct Henipavirus strain is known as the Langya Henipavirus or the LayV, and various aspects of this virus and the disease it causes, zoonotic public health concerns and whether it is a virus sitting on tip of the iceberg for causing any major public health concerns need to be investigated with further explorative researches and disease surveillance findings [7-15]. There are several Henipaviruses already identified among them Hendra virus and Nipah virus are two of the already known henipaviruses; the other kinds include cedar virus, mojiang virus, and the ghanaian bat virus, which are all considerably less virulent. The Cedar virus, Ghanaian bat virus, and Mojiang virus are not known to cause human disease, according to the United States, Centres for Disease Control. However, Hendra and Nipah infect humans and can cause severe sickness [10, 16]. Phylogenetic differences with other Henipaviruses, unknown history of occurrence, infection in humans, no early indication of human-to-human transmission, zoonotic involvements, less severity but considerable immune response raises concerns about future risks of LayV and possibility as potential pandemic pathogen [11, 14, 15, 17, 18].

Langya Virus

LayV for the first time was noticed during surveillance testing of individuals with fever and a recent history of animal exposure in eastern part of China [6, 9]. It was detected and isolated in a throat swab sample from a 53-year-old woman patient after metagenomic analysis and virus isolation. Researchers sequence all genetic material, remove "known" sequences (such as human DNA), and then hunt for "unknown" sequences that could constitute a new virus. LayV is an enveloped virus and has a single-stranded RNA genome with a negative orientation as in other viruses of the genus Henipavirus in the family Paramyxoviridae [18, 19]. This genome codes for six structural proteins (3’ end to 5’ end): nucleocapsid (N), phosphoprotein (P), matrix protein (M), surface glycoprotein (G), fusion protein (F), and large viral RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (L) [20]. This new virus appears to be a close relative of two prominent human viruses: Nipah virus and Hendra virus. LayV's genome contains 18,402 nucleotides and is organized similarly to those of other henipaviruses (11). RNA editing is an unusual process that henipaviruses utilize to produce many proteins from a single gene. After translation, the messenger RNA encoding the P gene in Henipaviruses engages in a novel mechanism that involves the incorporation of new guanosine sequences [21]. Both Nipah and Hendra viruses are zoonotic and constitute a persistent threat to livestock animals and people, but not LayV. Nipah and Hendra viruses are biosafety level-4 (BSL-4) pathogens, thus LayV may require BSL-4 facilities until its real risk is established [

1]. Gnomically LayV is more closely related to Mojianghenipavirus (MojV) which is a rat-borne virus [

6]. Phylogenetic analysis of structural proteins have revealed closeness of LayV and MojV [

6]. There are three common polymorphic sites (at nucleotide positions 13521, 13574, and 13643) in L gene sequence however its relevance in disease severity is yet to be established [18].

The virus was named after the town of Langya in Shandong, where she grew up. Further genomic study of LayV has shown that it is almost similar to Mojianghenipavirus, a rat-borne virus discovered in 2012 in the southern Chinese province of Yunnan [22]. The Wuhan Institute of Virology received serum from the miners who have passed away and confirmed that none of the samples tested positive for Ebola, Nipah, or Covid. The plight of the miners in China resulted in the isolation and detection of the Mojiangparamyxo virus in rats [23]. Many different henipaviruses have been detected in bats, rats, and shrews from Australia to South Korea and China, but only Hendra, Nipah, and now LayV infect humans [22].

Epidemiology and Transmission

This new virus is still poorly understood, and the reported cases are likely only the tip of the iceberg, however public health concerns need to be monitored for any future threat [9, 12, 14, 15]. Just 35 persons have contracted the disease since 2018 making it apparent, that there was no connection between any of the cases. There are currently no indications that the virus can spread from person to person [24]. Over 25% of the 262 shrews examined were positive for LayV, while 2% of domestic goats and 5% of dogs also tested positive for LayV antibodies, suggesting that shrews were a virus source [25]. Predominantly white-toothed Crociduralasiura shrews have been found positive for LayV. The patients did not show any signs of belonging to a larger epidemiological trend. Given that many of the affected patients are farmers, this would lend support to the notion of sporadic zoonotic transmission [17]. Like Nipah and Hendra, which are frequently transferred by fruit bats, LayV might be spread by the shrew [26, 27]. Higher prevalence of Lay viral RNA in shrews compared to rodents and domestic and pet animals (dog) have indicated shrews as primary reservoirs of LayV [18]. Climate change aggravated by deforestation, extinctions, more human invasions and animal interactions are making pandemics more likely in future [28-30]. Researchers further investigated whether the virus originated in domestic or wild animals. Although they detected a small number of previously infected domestic goats and dogs, there was more direct evidence that a significant proportion of wild shrews were affected. This suggests that humans may have caught the virus from wild shrews [22]. However, route of transmission has not been established. Direct transmission from shrews or involvement of another intermediate host is not known [6, 18].

Several virologists believe that LayV is transmitted directly to humans or through an intermediate animal, as none of the cases appear to be linked [19]. According to their finding, there was no evidence of LayV spreading between people, as there were no clusters of cases in the same family, within a short time frame, or in close geographical proximity. The study only performed contact tracing on 15 family members of 9 sick individuals, making it hard to specify how the individuals were exposed. In addition, Deputy Director-General Chuang Jen-hsiang of Taiwan's Centres for Disease Control (CDC) stated that human-to-human transmission of the virus has not yet been reported. According to him, the 35 affected individuals did not have close contact or a common history of exposure. Contact tracing also revealed no viral transmission between close contacts however Taiwan's laboratories must first develop a standardized nucleic acid testing procedure to keep track of human infections because the virus is new. Nonetheless, the CDC has not yet eliminated human-to-human transmission [31].

To understand the potential impact of the LayV, the existing risk needs to be assessed and potential containment steps to mitigate the same need to be outlined [9, 12]. Although scientists claim that the virus's chance of spreading to humans is low, it shares a close relationship with the two others human henipaviruses (Hendra and Nipah viruses) known to cause respiratory illnesses and even death, for instance Nipah, has a 90% mortality rate [

5].

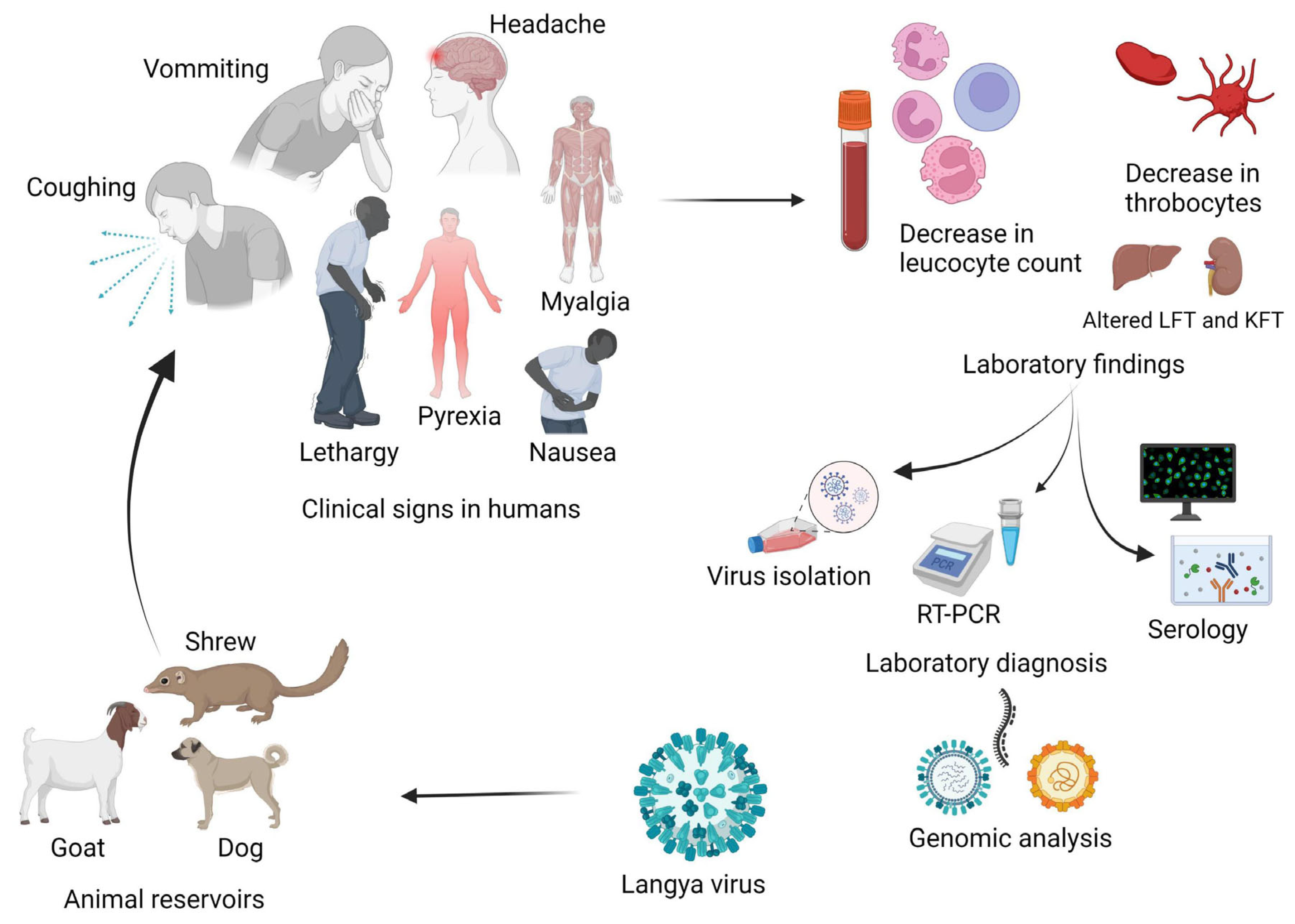

LayV is transmitted from Henan and Shandong Province in China, as depicted in the info-graphics below (

Figure 1: Info-graphics of Langya Henipavirus (LayV) Virus Transmission in China). Shrews serve as a natural reservoir for LayV. Humans can contract viruses from shrews, dogs and goats. Close contact with a person who is infected with LayV cannot spread the virus to other people.

An overview on salient features of Langya virus and info-graphics of its transmission in China are presented in

Figure 1.

Public Health Concerns

However, there is no need for panic because people who are known to have been infected with LayV have not yet been documented to have been fatal or very serious. Nevertheless, Wang Linfa, a professor at the Duke-NUS Medical School Program who specializes in emerging infectious diseases, noted it is still a matter of concern. He participated in the study and said that many viruses found in nature can have uncertain effects when they infect people, so it would be premature to act carelessly [32]. Though there have been no recorded fatalities in any of the known affected individuals some of the infected individuals experienced pneumonia, but the researchers do not specify the severity of the condition. According to Olivier Restiff of the University of Cambridge, as henipaviruses do not normally pass between humans, hence it is unlikely that LayV will become a pandemic. The Nipah virus is the only henipavirus with evidence of human-to-human transmission, and it requires very close contact. Further, he believes this infection does not have significant epidemic potential. According to other key findings from a recently published paper the new LayV, presumably shares a tick vector with another virus in China. Six of nine individuals were coinfected with LayV and were also infected with the tick-borne virus known as severe fever with thrombocytopenia syndrome (SFTS) bunyavirus. Based on the data, we know that both viruses have been observed in shrews in China, albeit in different species, and were most commonly discovered in agricultural settings in the provinces of Henan and Shandong, located in eastern China. Notably, earlier in 2015, a cluster of SFTS virus infections among nine individuals in Shandong province was connected to blood contact without personal protective equipment was reported [33]. The fact that there have been so few cases over many years implies that the LayV virus is not spreading rapidly states Francois Balloux of University College London. However, he believes that a virus that transfers from animals to people will be the most likely cause of any future pandemic as animals are the source of the great majority of our infections [

7]. Nonetheless, nothing in the data raises the spectra of a pandemic threat as the virus is unlikely to be contagious and can trigger an outbreak with relative ease [22].

Clinical Symptoms

Surprisingly, LayV primarily affected farm owners, and there are no apparent connections between the cases. The symptoms range from severe pneumonia to coughing [

8]. Those infected with LayV almost universally displayed the symptom of fever along with respiratory symptoms like cough and exhaustion, but no one has died as a result of it [19]. In Shandong and Henan provinces, out of the total 35 cases of LayV infection, it was found that 26 of them manifested symptoms including fever, cough, fatigue, irritability, loss of appetite, headache, muscle pain, nausea, and vomiting [9, 34]. All such 26 cases had a high temperature, 54% complained of fatigue, 50% had a cough, and 38% were nauseated. In addition, 35% of the overall population of 26 reported nausea with vomiting and recurring episodes of headaches. Additionally, the researchers discovered that certain affected individuals had leukopenia, or a lack of white blood cells needed by human bodies to combat infection, which was present in more than half of cases i.e 54%. A low number of platelets, the blood-clotting cells, were present in 35% of people, one third i.e. 35% experienced liver function issues, and 8% as renal function issues as well [

5]. Among the 26 patients with LayV infection, four pneumonia patients had the highest viral load in serum and throat swabs. High viral load in the serum indicated the possibility of blood-borne transmission [33]. Additional study is required to understand the severity of the infection, its mode of transmission, and its potential prevalence in China and other regions [24]. High rates of gingival bleeding have been predicted as a result of the novel LayV infection, which is in line with the thrombocytopenia issue associated with the condition. Gingival bleeding may be an indicator of a more significant health problem, according to recent studies. It is proposed that further study be conducted to confirm this observation [35].

An overview of clinical symptoms and pathology of Langya virus infection in humans is presented in

Figure 2.

Diagnosis

Isolation followed by molecular and serological tests are being used for diagnosis purposes. For viral isolation, cell culture assays are used. Human alveolar basal epithelial (A549), African green monkey kidney (Vero) and baby hamster kidney (BHK-21) cell lines have been used for viral isolation [6, 18]. Reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) targeting LayV L gene RNA has been developed [

6]. RT-PCR in association with nested RT-PCR and Sanger sequencing of the amplified L gene fragment has helped in confirmation of LayV RNA [6, 18]. Indirect immunofluorescence (IFA) IgG antibody detection assay targeting LayV has also been used for diagnostic purpose [

6]. Serum, whole blood, throat swabs are the samples required [6, 18]. For surveillance purposes sera in domestic animals (cattle, goat) and dog and tissue, intestine contents and urine samples from rodents and shrews have been evaluated [6,18]. The majority of the 35 reported cases during the latest LayV outbreak in China were found to be farmers or factory workers, and LayV was identified as a possible culprit in 26 patients (74% of the cases). The majority of samples (86%) collected during the convalescent phase of the illness had IgG titers that were four times greater than the IgG titers in samples collected during the acute phase of the infection. A total of 14 individuals provided serum samples at the onset and resolution of their infection. Recently diagnosed patients with acute viral infections were found to have viremia. Viral loads in patients with pneumonia and without pneumonia from sera and throat swabs have also proven diagnostic with higher loads in pneumonic patients than non-pneumonic patients [6, 9, 18].

Prevention and Control Measures

Recent data have not shown anything that would lead researchers to believe that LayV would become a pandemic threat. But scientists must carry out routine tests on humans and animals to keep this virus under control. Other than supportive care to address any consequences, there is presently no specific treatment or vaccination for LayV. When no alternative treatments for viral infections are available, ribavirin may be a viable option. Ribavirin has been shown to be helpful against the Hendra and Nipah viruses. Additionally, the antimalarial drug chloroquine may be used to treat these two. Therefore, if required, these two drugs may also aid in the management of LayV [36]. Supportive therapy for respiratory and neurological complications as practiced in other Henipavirus infections can be tried [1, 37]. Natural medicines like black seeds (Nigella Sativa) may have beneficial effects against LayV [38]. Further looking at the situation the development of innovative vaccines against reemerging viral infections is urgently needed. A vaccine against HeV infection in equines, antivirals, monoclonal antibodies and vaccines against HeV and NiV in humans are being evaluated [39].

The scarcity of adequate information and low number of cases detected till date indicate that presently there is no need to fear a worldwide health crisis or a pandemic caused by LayV, however proactive measures are required to be adopted after judging that we are not sitting at the edge of any iceberg, therefore need to be ready to counter any feasible future threat and / possible pandemic potential [11-15]. Strengthening of diagnostic facilities and surveillance activities are essential for monitoring the newer infections and risks of spread of LayV. Researchers and diagnosticians must do routine testing on animals and humans to discover the virus at an early stage and keep the viral infection under control. Standardized laboratories with nucleic acid testing capabilities are necessary for identifying LayV, which will aid in tracking virus infection in humans.

Explorative researches are required to investigate any severity of LayV infection, the means of transmission, and the appraisal of the virus's feasible overall spread in China and the world as a whole [11-15]. Infectious disease researchers have been sounding the alarm for a while now about the potential for zoonotic virus spillovers due to the climate catastrophe and the reckless destruction of natural resources. The LayV epidemic is a prime illustration of this phenomenon. As a result, fighting zoonotic infections calls for combined health and conservation efforts. To further reduce the possibility of an emerging virus becoming a global health concern, it is essential to conduct active surveillance in a transparent and internationally coordinated fashion. Notably, the results of the investigation of LayV infections are based on a relatively small number of instances. It is yet unknown if and how LayV can be transmitted from person to person. Therefore, more research and exploratory studies are needed to better understand the microbiological and epidemiological characteristics of LayV infection.

Though it is believed that LayV does not meet the criteria of Koch’s postulates and their relevance in the modern era, however the present situation of involving only a small number of disease cases with significant immune response to virus and viral load compared to healthy ones have raised concerns about this virus [40]. These findings are based on a small number of cases, thus additional inquiry and research will be necessary to better understand the epidemiological and microbiological aspects of the disease and virus. The detection of LayV belonging to the genus Henipavirus has not before been reported earlier; thus this highlights the ongoing threat posed by the upcoming new virus [41].

The discovery of LayV is significant because it demonstrates how easily zoonotic viruses may be transferred undetected from animals to humans and suggests that animal viruses are routinely leaking in hidden ways into people around the globe. Although LayV has not yet been shown to spread easily between humans and is not lethal, researchers believe that shrews are reservoirs for the virus and that shrews may have infected humans either directly or indirectly through the transmission of the virus from shrew to human. Therefore, more research is recommended to understand the spillover occurrences and learn how the virus spreads in shrews and how it can be transmitted to humans [9, 12].

To avoid further pandemics like the one caused by COVID-19, a global surveillance system capable of detecting emerging pathogens and rapidly transmitting the results is urgently needed. These zoonotic spillover episodes happen all the time, so the world must wake up [22]. This highlights the need of keeping an eye out for animal infections that could cause the next pandemic in humans. It is imperative that transparent, international, cooperative active surveillance be carried out in the event of a newly emerging virus in order to lessen the likelihood of a health catastrophe.

Conclusions and Future Prospects

Since LayV was just recently discovered, much remains to be investigated in order to learn more about this newly recognized henipavirus of likely animal origin and the febrile sickness it causes. Increased efforts should be made to conduct research on LayV, as well as to critically extend surveillance and monitoring activities, to determine the hosts and reservoir animal species of LayV, and to adopt a unifying health concept to reduce the amount of animal-human contact. Further in-depth studies and extensive epidemiological investigations are needed to determine whether or whether the disease severity is relatively low, as demonstrated by limited instances / low sample size, or how much feasible threats it could bring to humans. However, we must be prepared in advance by adopting appropriate preventative measures and implementing proactive control strategies for limiting its possible spread to other regions and countries.

References

- Kummer S, Kranz DC. Henipaviruses-A constant threat to livestock and humans. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2022 Feb 18; 16(2):e0010157. [CrossRef]

- Santana C. COVID-19, other zoonotic diseases and wildlife conservation. Hist Philos Life Sci. 2020 Oct 8; 42(4):45.

- Keatts LO, Robards M, Olson SH, Hueffer K, Insley SJ, Joly DO, et al. Implications of Zoonoses From Hunting and Use of Wildlife in North American Arctic and Boreal Biomes: Pandemic Potential, Monitoring, and Mitigation. Frontiers in Public Health [Internet]. 2021 [cited 2022 Aug 29]; 9. Available from: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpubh.2021.627654.

- Leal Filho W, Ternova L, Parasnis SA, Kovaleva M, Nagy GJ. Climate Change and Zoonoses: A Review of Concepts, Definitions, and Bibliometrics. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022 Jan 14; 19(2):893. [CrossRef]

- Five things you need to know about Langya virus [Internet]. [cited 2022 Aug 29]. Available from: https://www.gavi.org/vaccineswork/five-things-you-need-know-about-langya-virus.

- Zhang XA, Li H, Jiang FC, Zhu F, Zhang YF, Chen JJ, et al. A Zoonotic Henipavirus in Febrile Patients in China. New England Journal of Medicine. 2022 Aug 4; 387(5):470–2. [CrossRef]

- #author.fullName}. Langya virus: How serious is the new pathogen discovered in China? [Internet]. New Scientist. [cited 2022 Aug 27]. Available from: https://www.newscientist.com/article/2333107-langya-virus-how-serious-is-the-new-pathogen-discovered-in-china/.

- Lu D. Newly identified Langya virus tracked after China reports dozens of cases. The Guardian [Internet]. 2022 Aug 10 [cited 2022 Aug 27]; Available from: https://www.theguardian.com/science/2022/aug/10/newly-identified-langya-virus-tracked-after-china-reports-dozens-of-cases.

- Sah R, Mohanty A, Chakraborty S, Dhama K. Langya Virus: A Newly Identified Zoonotic Henipavirus. Journal of Medical Virology [Internet]. [cited 2022 Aug 29];n/a(n/a). Available from: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1002/jmv.28095.

- Explained: What is Langya, a new zoonotic virus that has infected 35 people in China? [Internet]. The Indian Express. 2022 [cited 2022 Aug 27]. Available from: https://indianexpress.com/article/explained/explained-health/what-is-langya-virus-discovered-in-china-8081659/.

- Hanif M, Huang H, Sonkar V, Jaiswal V. The recent emergence of Langya henipavirus in China: Should we be concerned? Ann Med Surg (Lond). 2022 Nov 12; 84:104896. [CrossRef]

- Chakraborty S, Chandran D, Mohapatra RK, Islam MA, Alagawany M, Bhattacharya M, Chakraborty C, Dhama K. Langya virus, a newly identified Henipavirus in China - Zoonotic pathogen causing febrile illness in humans, and its health concerns: Current knowledge and counteracting strategies - Correspondence. Int J Surg. 2022 Sep 5; 105:106882. [CrossRef]

- Taseen S, Abbas M, Nasir F, Wania Amjad S, Asghar MS. Tip of the iceberg: Emergence of Langya virus in the postpandemic world. J Med Virol. 2022 Sep 25. [CrossRef]

- Tabassum S, Naeem A, Rehan ST, Nashwan AJ. Langya virus outbreak in China, 2022: Are we on the verge of a new pandemic? J Virus Erad. 2022 Sep 17; 8(3):100087. [CrossRef]

- Quarleri J, Galvan V, Delpino MV. Henipaviruses: an expanding global public health concern? Geroscience. 2022 Oct 11:1–13. [CrossRef]

- Henipaviruses - Chapter 4 - 2020 Yellow Book | Travelers’ Health | CDC [Internet]. [cited 2022 Aug 30]. Available from: https://wwwnc.cdc.gov/travel/yellowbook/2020/travel-related-infectious-diseases/henipaviruses.

- ECDC 2022. Langya henipavirus under ECDC monitoring. https://www.ecdc.europa.eu/en/news-events/langya-henipavirus-under-ecdc-monitoring. Accessed on 4th Sept. 2022.

- PHO 2022. Ontario Agency for Health Protection and Promotion (Public Health Ontario). Risk assessment for langya henipavirus (LayV) in Ontario. Toronto, ON: Queen's Printer for Ontario; 2022. https://www.publichealthontario.ca/-/media/Documents/L/2022/langya-henipavirus-risk-assesment-ontario.pdf?sc_lang=en. Accessed 4th Sept. 2022.

- Choudhary OP, Priyanka, Fahrni ML, Metwally AA, Saied AA. Spillover zoonotic “Langya virus”: Is it a matter of concern? Veterinary Quarterly. 2022 Aug 24; 0(ja):1–4.

- Lawrence P, Escudero-Pérez B. Henipavirus immune evasion and pathogenesis mechanisms: lessons learnt from natural infection and animal models. Viruses. 2022; 14(5):936. Available from: https://doi.org/10.3390/v14050936.

- Akash S, Rahman MM, Islam MR, Sharma R. Emerging global concern of Langya Henipavirus: Pathogenicity, Virulence, Genomic features, and Future perspectives. J Med Virol. 2022 Sep 6. [CrossRef]

- Mallapaty S. New ‘Langya’ virus identified in China: what scientists know so far. Nature. 2022 Aug 11; 608(7924):656–7.

- Wu Z, Yang L, Yang F, Ren X, Jiang J, Dong J, et al. Novel Henipa-like Virus, Mojiang Paramyxovirus, in Rats, China, 2012. Emerg Infect Dis. 2014 Jun; 20(6):1064–6. [CrossRef]

- US AC The Conversation. What Is the New Langya Virus, and Should We Be Worried? [Internet]. Scientific American. [cited 2022 Aug 29]. Available from: https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/what-is-the-new-langya-virus-and-should-we-be-worried/.

- Choudhary OP, Priyanka, Fahrni ML, Metwally AA, Saied AA. Spillover zoonotic “Langya virus”: Is it a matter of concern? Veterinary Quarterly. 2022 Aug 24; 0(ja):1–4. [CrossRef]

- Langya Henipavirus found in China: Is the new virus fatal? And six other questions answered. The Economic Times [Internet]. 2022 Aug 10 [cited 2022 Aug 29]; Available from: https://economictimes.indiatimes.com/news/new-updates/langya-henipavirus-found-in-china-is-the-new-virus-fatal-and-six-other-questions-answered/articleshow/93481224.cms.

- Novel Langya henipavirus: Infection may have spread through rodent-like mammals [Internet]. [cited 2022 Aug 29]. Available from: https://www.downtoearth.org.in/news/health/novel-langya-henipavirus-infection-may-have-spread-through-rodent-like-mammals-84237.

- Maxmen, A. Bats are global reservoir for deadly coronaviruses. Nature 546, 340 (2017). [CrossRef]

- Gilbert N. 2022. Climate change will force new animal encounters — and boost viral outbreaks. Nature 605, 20 (2022). [CrossRef]

- Tollefson J. 2022. Why deforestation and extinctions make pandemics more likely. Nature 584, 175-176 (2020). [CrossRef]

- Langya Henipavirus: All you need to know about new zoonotic virus that’s infected 35 people [Internet]. Business Today. 2022 [cited 2022 Aug 29]. Available from: https://www.businesstoday.in/latest/economy/story/langya-henipavirus-all-you-need-to-know-about-new-zoonotic-virus-thats-infected-35-people-344274-2022-08-10.

- August 10 PT of IB, August 10 2022UPDATED:,Ist 2022 08:18. New ‘Langya’ virus hits China, 35 people infected [Internet]. India Today. [cited 2022 Aug 29]. Available from: https://www.indiatoday.in/world/story/langya-virus-china-35-infected-henipavirus-shandong-henan-infection-1986012-2022-08-10.

- FIDSA DRL MD, MPH. Langya virus and SFTS virus coinfections in China mean a shared tick vector is likely [Internet]. [cited 2022 Aug 29]. Available from: https://www.idsociety.org/science-speaks-blog/2022/langya-virus-and-sfts-virus-coinfections-in-china-mean-a-shared-tick-vector-is-likely/.

- China reports cases of Langya virus. What is this new zoonotic disease that has infected over 30 people? [Internet]. Financialexpress. [cited 2022 Aug 29]. Available from: https://www.financialexpress.com/healthcare/news-healthcare/china-reports-cases-of-langya-virus-what-is-this-new-zoonotic-disease-that-has-infected-over-30-people/2624570/.

- Mungmunpuntipantip R, Wiwanitkit V. Gingival bleeding in Langya Henipavirus and severity of infection: A concern. J Stomatol Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2022 Aug 24:S2468-7855(22)00237-3. [CrossRef]

- Benisek A. What Is Langya Henipavirus? [Internet]. WebMD. [cited 2022 Aug 29]. Available from: https://www.webmd.com/lung/langya-henipavirus.

- Shoemaker T, Choi MJ. Henipaviruses. In: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention CDC yellow book 2020: health information for international travel [Internet]. New York: Oxford University Press; 2017 [cited 2022 Aug 18]. Available from: https://wwwnc.cdc.gov/travel/yellowbook/2020/travelrelated-infectious-diseases/henipaviruses.

- Maideen NMP. Probable beneficial effects of black seeds (Nigella Sativa) in the management of langyahenipavirus infection. Food Health. 2022;4(4):17. [CrossRef]

- Clayton BA, Wang LF, Marsh GA. Henipaviruses: an updated review focusing on the pteropid reservoir and features of transmission. Zoonoses Public Health. 2013; 60(1):69-83. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1863-2378.2012.01501.x. [CrossRef]

- Cheng A. 2022. What Is This New Langya Virus? Do We Need to Be Worried? The Scientist. Accessed 4th Sept. 2022. https://www.the-scientist.com/news-opinion/what-is-this-new-langya-virus-do-we-need-to-be-worried-70352.

- Langya henipavirus under ECDC monitoring [Internet]. European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. 2022 [cited 2022 Aug 29]. Available from: https://www.ecdc.europa.eu/en/news-events/langya-henipavirus-under-ecdc-monitoring.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).