Submitted:

27 January 2023

Posted:

30 January 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

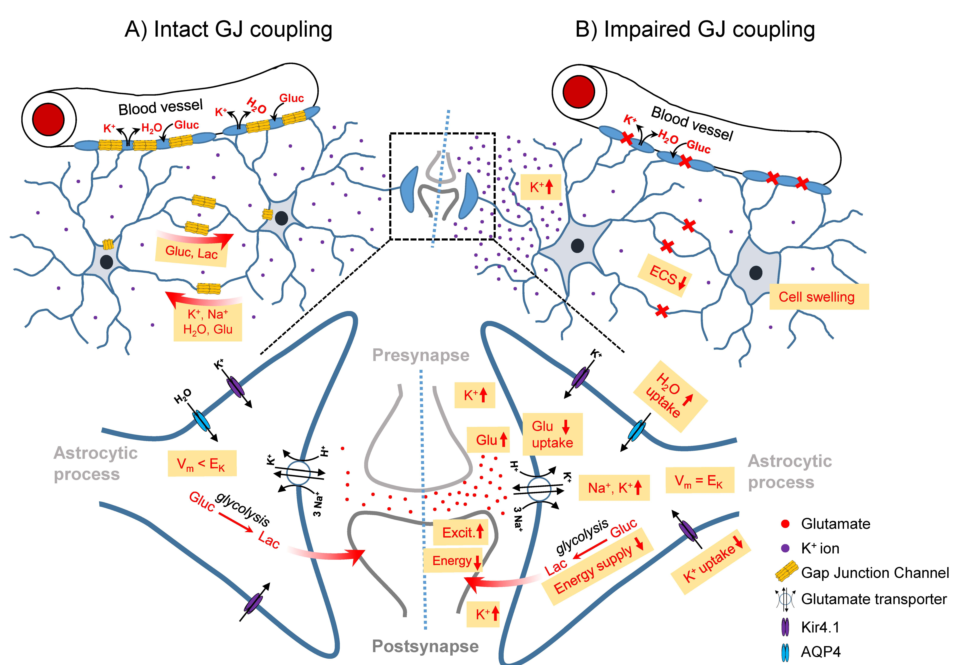

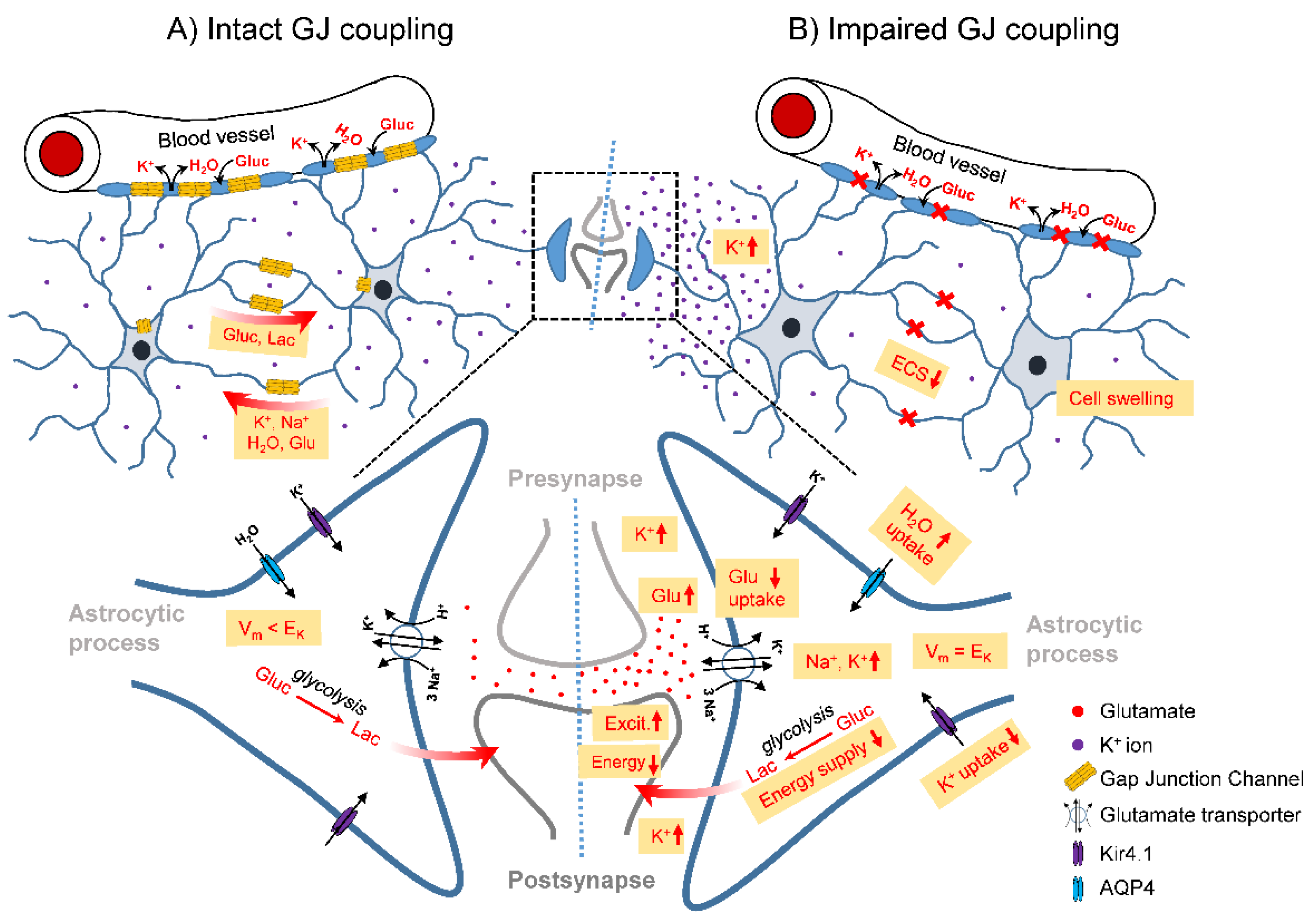

2. Role of glial Cx channels in epilepsy

3. Connexin expression and GJ coupling in human epilepsy

4. Connexin expression, communication and regulation in experimental epilepsy

5. Impact of glial Cx gene knockout on neuronal excitability and epileptogenesis

6. Therapeutic potential of targeting glial Cx channels in epilepsy

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Fisher, R.S.; Acevedo, C.; Arzimanoglou, A.; Bogacz, A.; Cross, J.H.; Elger, C.E.; Engel, J.; Forsgren, L.; French, J.A.; Glynn, M.; et al. ILAE Official Report: A Practical Clinical Definition of Epilepsy. Epilepsia 2014, 55, 475–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fiest, K.M.; Sauro, K.M.; Wiebe, S.; Patten, S.B.; Kwon, C.-S.; Dykeman, J.; Pringsheim, T.; Lorenzetti, D.L.; Jetté, N. Prevalence and Incidence of Epilepsy: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of International Studies. Neurology 2017, 88, 296–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Löscher, W.; Potschka, H.; Sisodiya, S.M.; Vezzani, A. Drug Resistance in Epilepsy: Clinical Impact, Potential Mechanisms, and New Innovative Treatment Options. Pharmacol Rev 2020, 72, 606–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stafstrom, C.E. Mechanisms of Action of Antiepileptic Drugs: The Search for Synergy. Current Opinion in Neurology 2010, 23, 157–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boison, D.; Steinhäuser, C. Epilepsy and Astrocyte Energy Metabolism. Glia 2018, 66, 1235–1243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Binder, D.K.; Steinhäuser, C. Astrocytes and Epilepsy. Neurochem Res 2021, 46, 2687–2695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verkhratsky, A.; Nedergaard, M. Physiology of Astroglia. Physiol Rev 2018, 98, 239–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giaume, C.; Naus, C.C.; Sáez, J.C.; Leybaert, L. Glial Connexins and Pannexins in the Healthy and Diseased Brain. Physiological Reviews 2020, 101, 93–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giaume, C.; Koulakoff, A.; Roux, L.; Holcman, D.; Rouach, N. Astroglial Networks: A Step Further in Neuroglial and Gliovascular Interactions. Nat Rev Neurosci 2010, 11, 87–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gosejacob, D.; Dublin, P.; Bedner, P.; Hüttmann, K.; Zhang, J.; Tress, O.; Willecke, K.; Pfrieger, F.; Steinhäuser, C.; Theis, M. Role of Astroglial Connexin30 in Hippocampal Gap Junction Coupling. Glia 2011, 59, 511–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griemsmann, S.; Höft, S.P.; Bedner, P.; Zhang, J.; von Staden, E.; Beinhauer, A.; Degen, J.; Dublin, P.; Cope, D.W.; Richter, N.; et al. Characterization of Panglial Gap Junction Networks in the Thalamus, Neocortex, and Hippocampus Reveals a Unique Population of Glial Cells. Cereb Cortex 2015, 25, 3420–3433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deshpande, T.; Li, T.; Herde, M.K.; Becker, A.; Vatter, H.; Schwarz, M.K.; Henneberger, C.; Steinhäuser, C.; Bedner, P. Subcellular Reorganization and Altered Phosphorylation of the Astrocytic Gap Junction Protein Connexin43 in Human and Experimental Temporal Lobe Epilepsy. Glia 2017, 65, 1809–1820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bedner, P.; Jabs, R.; Steinhäuser, C. Properties of Human Astrocytes and NG2 Glia. Glia 2020, 68, 756–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Valiunas, V.; Manthey, D.; Vogel, R.; Willecke, K.; Weingart, R. Biophysical Properties of Mouse Connexin30 Gap Junction Channels Studied in Transfected Human HeLa Cells. The Journal of Physiology 1999, 519, 631–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Valiunas, V.; Weingart, R.; Brink, P.R. Formation of Heterotypic Gap Junction Channels by Connexins 40 and 43. Circ Res 2000, 86, E42–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solan, J.L.; Lampe, P.D. Connexin43 Phosphorylation: Structural Changes and Biological Effects. Biochemical Journal 2009, 419, 261–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manthey, D.; Banach, K.; Desplantez, T.; Lee, C.G.; Kozak, C.A.; Traub, O.; Weingart, R.; Willecke, K. Intracellular Domains of Mouse Connexin26 and -30 Affect Diffusional and Electrical Properties of Gap Junction Channels. J. Membrane Biol. 2001, 181, 137–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Magnotti, L.M.; Goodenough, D.A.; Paul, D.L. Functional Heterotypic Interactions between Astrocyte and Oligodendrocyte Connexins. Glia 2011, 59, 26–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giaume, C.; Leybaert, L.; Naus, C.; Sáez, J.-C. Connexin and Pannexin Hemichannels in Brain Glial Cells: Properties, Pharmacology, and Roles. Front. Pharmacol. 2013, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vinken, M.; Decrock, E.; Leybaert, L.; Bultynck, G.; Himpens, B.; Vanhaecke, T.; Rogiers, V. Non-Channel Functions of Connexins in Cell Growth and Cell Death. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Biomembranes 2012, 1818, 2002–2008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kunze, A.; Congreso, M.R.; Hartmann, C.; Wallraff-Beck, A.; Hüttmann, K.; Bedner, P.; Requardt, R.; Seifert, G.; Redecker, C.; Willecke, K.; et al. Connexin Expression by Radial Glia-like Cells Is Required for Neurogenesis in the Adult Dentate Gyrus. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2009, 106, 11336–11341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steinhäuser, C.; Seifert, G.; Bedner, P. Astrocyte Dysfunction in Temporal Lobe Epilepsy: K+ Channels and Gap Junction Coupling. Glia 2012, 60, 1192–1202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bedner, P.; Steinhäuser, C. Altered Kir and Gap Junction Channels in Temporal Lobe Epilepsy. Neurochemistry International 2013, 63, 682–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bedner, P.; Dupper, A.; Hüttmann, K.; Müller, J.; Herde, M.K.; Dublin, P.; Deshpande, T.; Schramm, J.; Häussler, U.; Haas, C.A.; et al. Astrocyte Uncoupling as a Cause of Human Temporal Lobe Epilepsy. Brain 2015, 138, 1208–1222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Henning, L.; Unichenko, P.; Bedner, P.; Steinhäuser, C.; Henneberger, C. Overview Article Astrocytes as Initiators of Epilepsy. Neurochem Res 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Orkand, R.K. Introductory Remarks: Glial-Interstitial Fluid Exchange. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences 1986, 481, 269–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walz, W. Role of Astrocytes in the Clearance of Excess Extracellular Potassium. Neurochemistry International 2000, 36, 291–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kofuji, P.; Newman, E.A. Potassium Buffering in the Central Nervous System. Neuroscience 2004, 129, 1043–1054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Breithausen, B.; Kautzmann, S.; Boehlen, A.; Steinhäuser, C.; Henneberger, C. Limited Contribution of Astroglial Gap Junction Coupling to Buffering of Extracellular K+ in CA1 Stratum Radiatum. Glia 2020, 68, 918–931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wallraff, A.; Köhling, R.; Heinemann, U.; Theis, M.; Willecke, K.; Steinhäuser, C. The Impact of Astrocytic Gap Junctional Coupling on Potassium Buffering in the Hippocampus. J. Neurosci. 2006, 26, 5438–5447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henneberger, C. Does Rapid and Physiological Astrocyte–Neuron Signalling Amplify Epileptic Activity? The Journal of Physiology 2017, 595, 1917–1927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Langer, J.; Stephan, J.; Theis, M.; Rose, C.R. Gap Junctions Mediate Intercellular Spread of Sodium between Hippocampal Astrocytes in Situ. Glia 2012, 60, 239–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kirischuk, S.; Parpura, V.; Verkhratsky, A. Sodium Dynamics: Another Key to Astroglial Excitability? Trends in Neurosciences 2012, 35, 497–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rose, C.R.; Felix, L.; Zeug, A.; Dietrich, D.; Reiner, A.; Henneberger, C. Astroglial Glutamate Signaling and Uptake in the Hippocampus. Front Mol Neurosci 2017, 10, 451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Riquelme, J.; Wellmann, M.; Sotomayor-Zárate, R.; Bonansco, C. Gliotransmission: A Novel Target for the Development of Antiseizure Drugs. Neuroscientist 2020, 26, 293–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, J.; Timmermann, A.; Henning, L.; Müller, H.; Steinhäuser, C.; Bedner, P. Astrocytic GABA Accumulation in Experimental Temporal Lobe Epilepsy. Front Neurol 2020, 11, 614923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pannasch, U.; Vargová, L.; Reingruber, J.; Ezan, P.; Holcman, D.; Giaume, C.; Syková, E.; Rouach, N. Astroglial Networks Scale Synaptic Activity and Plasticity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2011, 108, 8467–8472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bazzigaluppi, P.; Weisspapir, I.; Stefanovic, B.; Leybaert, L.; Carlen, P.L. Astrocytic Gap Junction Blockade Markedly Increases Extracellular Potassium without Causing Seizures in the Mouse Neocortex. Neurobiology of Disease 2017, 101, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EbrahimAmini, A.; Bazzigaluppi, P.; Aquilino, M.S.; Stefanovic, B.; Carlen, P.L. Neocortical in Vivo Focal and Spreading Potassium Responses and the Influence of Astrocytic Gap Junctional Coupling. Neurobiology of Disease 2021, 147, 105160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hösli, L.; Binini, N.; Ferrari, K.D.; Thieren, L.; Looser, Z.J.; Zuend, M.; Zanker, H.S.; Berry, S.; Holub, M.; Möbius, W.; et al. Decoupling Astrocytes in Adult Mice Impairs Synaptic Plasticity and Spatial Learning. Cell Rep 2022, 38, 110484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rouach, N.; Koulakoff, A.; Abudara, V.; Willecke, K.; Giaume, C. Astroglial Metabolic Networks Sustain Hippocampal Synaptic Transmission. Science 2008, 322, 1551–1555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Philippot, C.; Griemsmann, S.; Jabs, R.; Seifert, G.; Kettenmann, H.; Steinhäuser, C. Astrocytes and Oligodendrocytes in the Thalamus Jointly Maintain Synaptic Activity by Supplying Metabolites. Cell Rep 2021, 34, 108642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gómez-Gonzalo, M.; Losi, G.; Chiavegato, A.; Zonta, M.; Cammarota, M.; Brondi, M.; Vetri, F.; Uva, L.; Pozzan, T.; de Curtis, M.; et al. An Excitatory Loop with Astrocytes Contributes to Drive Neurons to Seizure Threshold. PLoS Biol. 2010, 8, e1000352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nielsen, B.S.; Hansen, D.B.; Ransom, B.R.; Nielsen, M.S.; MacAulay, N. Connexin Hemichannels in Astrocytes: An Assessment of Controversies Regarding Their Functional Characteristics. Neurochem Res 2017, 42, 2537–2550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walrave, L.; Pierre, A.; Albertini, G.; Aourz, N.; Bundel, D.D.; Eeckhaut, A.V.; Vinken, M.; Giaume, C.; Leybaert, L.; Smolders, I. Inhibition of Astroglial Connexin43 Hemichannels with TAT-Gap19 Exerts Anticonvulsant Effects in Rodents. Glia 2018, 66, 1788–1804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walrave, L.; Vinken, M.; Leybaert, L.; Smolders, I. Astrocytic Connexin43 Channels as Candidate Targets in Epilepsy Treatment. Biomolecules 2020, 10, 1578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, A.; Zhang, H.; Li, H.; Chiu, A.; García-Rodríguez, C.; Lagos, C.F.; Sáez, J.C.; Lau, C.G. Inhibition of Connexin Hemichannels Alleviates Neuroinflammation and Hyperexcitability in Temporal Lobe Epilepsy. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2022, 119, e2213162119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scemes, E. Modulation of Astrocyte P2Y1 Receptors by the Carboxyl Terminal Domain of the Gap Junction Protein Cx43. Glia 2008, 56, 145–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikolic, L.; Nobili, P.; Shen, W.; Audinat, E. Role of Astrocyte Purinergic Signaling in Epilepsy. Glia 2020, 68, 1677–1691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vezzani, A.; Ravizza, T.; Bedner, P.; Aronica, E.; Steinhäuser, C.; Boison, D. Astrocytes in the Initiation and Progression of Epilepsy. Nat Rev Neurol 2022, 18, 707–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pannasch, U.; Freche, D.; Dallérac, G.; Ghézali, G.; Escartin, C.; Ezan, P.; Cohen-Salmon, M.; Benchenane, K.; Abudara, V.; Dufour, A.; et al. Connexin 30 Sets Synaptic Strength by Controlling Astroglial Synapse Invasion. Nature Neuroscience 2014, 17, 549–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aronica, E.; Gorter, J.A.; Jansen, G.H.; Leenstra, S.; Yankaya, B.; Troost, D. Expression of Connexin 43 and Connexin 32 Gap-Junction Proteins in Epilepsy-Associated Brain Tumors and in the Perilesional Epileptic Cortex. Acta Neuropathol 2001, 101, 449–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Collignon, F.; Wetjen, N.M.; Cohen-Gadol, A.A.; Cascino, G.D.; Parisi, J.; Meyer, F.B.; Marsh, W.R.; Roche, P.; Weigand, S.D. Altered Expression of Connexin Subtypes in Mesial Temporal Lobe Epilepsy in Humans. Journal of Neurosurgery 2006, 105, 77–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Naus, C.C.G.; Bechberger, J.F.; Paul, D.L. Gap Junction Gene Expression in Human Seizure Disorder. Experimental Neurology 1991, 111, 198–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Das, A.; Wallace, G.C.; Holmes, C.; McDowell, M.L.; Smith, J.A.; Marshall, J.D.; Bonilha, L.; Edwards, J.C.; Glazier, S.S.; Ray, S.K.; et al. Hippocampal Tissue of Patients with Refractory Temporal Lobe Epilepsy Is Associated with Astrocyte Activation, Inflammation, and Altered Expression of Channels and Receptors. Neuroscience 2012, 220, 237–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elisevich, K.; Rempel, S.A.; Smith, B.J.; Edvardsen, K. Hippocampal Connexin 43 Expression in Human Complex Partial Seizure Disorder. Experimental Neurology 1997, 145, 154–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fonseca, C.G.; Green, C.R.; Nicholson, L.F.B. Upregulation in Astrocytic Connexin 43 Gap Junction Levels May Exacerbate Generalized Seizures in Mesial Temporal Lobe Epilepsy. Brain Research 2002, 929, 105–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garbelli, R.; Frassoni, C.; Condorelli, D.F.; Salinaro, A.T.; Musso, N.; Medici, V.; Tassi, L.; Bentivoglio, M.; Spreafico, R. Expression of Connexin 43 in the Human Epileptic and Drug-Resistant Cerebral Cortex. Neurology 2011, 76, 895–902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heinemann, U.; Gabriel, S.; Jauch, R.; Schulze, K.; Kivi, A.; Eilers, A.; Kovacs, R.; Lehmann, T.-N. Alterations of Glial Cell Function in Temporal Lobe Epilepsy. Epilepsia 2000, 41, S185–S189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jauch, R.; Windmüller, O.; Lehmann, T.-N.; Heinemann, U.; Gabriel, S. Effects of Barium, Furosemide, Ouabaine and 4,4′-Diisothiocyanatostilbene-2,2′-Disulfonic Acid (DIDS) on Ionophoretically-Induced Changes in Extracellular Potassium Concentration in Hippocampal Slices from Rats and from Patients with Epilepsy. Brain Research 2002, 925, 18–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kivi, A.; Lehmann, T.-N.; Kovács, R.; Eilers, A.; Jauch, R.; Meencke, H.J.; Deimling, A.V.; Heinemann, U.; Gabriel, S. Effects of Barium on Stimulus-Induced Rises of [K+]o in Human Epileptic Non-Sclerotic and Sclerotic Hippocampal Area CA1. European Journal of Neuroscience 2000, 12, 2039–2048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hinterkeuser, S.; Schröder, W.; Hager, G.; Seifert, G.; Blümcke, I.; Elger, C.E.; Schramm, J.; Steinhäuser, C. Astrocytes in the Hippocampus of Patients with Temporal Lobe Epilepsy Display Changes in Potassium Conductances. European Journal of Neuroscience 2000, 12, 2087–2096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blümcke, I.; Beck, H.; Lie, A.A.; Wiestler, O.D. Molecular Neuropathology of Human Mesial Temporal Lobe Epilepsy. Epilepsy Research 1999, 36, 205–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Löscher, W.; Schmidt, D. Modern Antiepileptic Drug Development Has Failed to Deliver: Ways out of the Current Dilemma. Epilepsia 2011, 52, 657–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jefferys, J.; Steinhäuser, C.; Bedner, P. Chemically-Induced TLE Models: Topical Application. Journal of Neuroscience Methods 2016, 260, 53–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rusina, E.; Bernard, C.; Williamson, A. The Kainic Acid Models of Temporal Lobe Epilepsy. eNeuro 2021, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Condorelli, D.F.; Mudò, G.; Trovato-Salinaro, A.; Mirone, M.B.; Amato, G.; Belluardo, N. Connexin-30 MRNA Is Up-Regulated in Astrocytes and Expressed in Apoptotic Neuronal Cells of Rat Brain Following Kainate-Induced Seizures. Molecular and Cellular Neuroscience 2002, 21, 94–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Condorelli, D.F.; Trovato-Salinaro, A.; Mudò, G.; Mirone, M.B.; Belluardo, N. Cellular Expression of Connexins in the Rat Brain: Neuronal Localization, Effects of Kainate-Induced Seizures and Expression in Apoptotic Neuronal Cells. European Journal of Neuroscience 2003, 18, 1807–1827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussein, A.M.; Abbas, K.M.; Abulseoud, O.A.; El-Hussainy, E.-H.M.A. Effects of Ferulic Acid on Oxidative Stress, Heat Shock Protein 70, Connexin 43, and Monoamines in the Hippocampus of Pentylenetetrazole-Kindled Rats. Can J Physiol Pharmacol 2017, 95, 732–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kinjo, E.R.; Higa, G.S.V.; Morya, E.; Valle, A.C.; Kihara, A.H.; Britto, L.R.G. Reciprocal Regulation of Epileptiform Neuronal Oscillations and Electrical Synapses in the Rat Hippocampus. PLOS ONE 2014, 9, e109149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCracken, C.B.; Roberts, D.C.S. A Single Evoked Afterdischarge Produces Rapid Time-Dependent Changes in Connexin36 Protein Expression in Adult Rat Dorsal Hippocampus. Neurosci Lett 2006, 405, 84–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pannasch, U.; Dossi, E.; Ezan, P.; Rouach, N. Astroglial Cx30 Sustains Neuronal Population Bursts Independently of Gap-Junction Mediated Biochemical Coupling. Glia 2019, 67, 1104–1112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Söhl, G.; Güldenagel, M.; Beck, H.; Teubner, B.; Traub, O.; Gutiérrez, R.; Heinemann, U.; Willecke, K. Expression of Connexin Genes in Hippocampus of Kainate-Treated and Kindled Rats under Conditions of Experimental Epilepsy. Molecular Brain Research 2000, 83, 44–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takahashi, D.K.; Vargas, J.R.; Wilcox, K.S. Increased Coupling and Altered Glutamate Transport Currents in Astrocytes Following Kainic-Acid-Induced Status Epilepticus. Neurobiology of Disease 2010, 40, 573–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, X.L.; Tang, Y.C.; Lu, Q.Y.; Xiao, X.L.; Song, T.B.; Tang, F.R. Astrocytic Cx 43 and Cx 40 in the Mouse Hippocampus during and after Pilocarpine-Induced Status Epilepticus. Exp Brain Res 2015, 233, 1529–1539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khan, D.; Dupper, A.; Deshpande, T.; Graan, P.N.E.D.; Steinhäuser, C.; Bedner, P. Experimental Febrile Seizures Impair Interastrocytic Gap Junction Coupling in Juvenile Mice. Journal of Neuroscience Research 2016, 94, 804–813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choy, M.; Dubé, C.M.; Ehrengruber, M.; Baram, T.Z. Inflammatory Processes, Febrile Seizures, and Subsequent Epileptogenesis. Epilepsy Curr 2014, 14, 15–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vezzani, A.; Balosso, S.; Ravizza, T. Neuroinflammatory Pathways as Treatment Targets and Biomarkers in Epilepsy. Nat Rev Neurol 2019, 15, 459–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Même, W.; Calvo, C.-F.; Froger, N.; Ezan, P.; Amigou, E.; Koulakoff, A.; Giaume, C. Proinflammatory Cytokines Released from Microglia Inhibit Gap Junctions in Astrocytes: Potentiation by β-Amyloid. The FASEB Journal 2006, 20, 494–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Retamal, M.A.; Froger, N.; Palacios-Prado, N.; Ezan, P.; Sáez, P.J.; Sáez, J.C.; Giaume, C. Cx43 Hemichannels and Gap Junction Channels in Astrocytes Are Regulated Oppositely by Proinflammatory Cytokines Released from Activated Microglia. J. Neurosci. 2007, 27, 13781–13792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haghikia, A.; Ladage, K.; Hinkerohe, D.; Vollmar, P.; Heupel, K.; Dermietzel, R.; Faustmann, P.M. Implications of Antiinflammatory Properties of the Anticonvulsant Drug Levetiracetam in Astrocytes. Journal of Neuroscience Research 2008, 86, 1781–1788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Henning, L.; Antony, H.; Breuer, A.; Müller, J.; Seifert, G.; Audinat, E.; Singh, P.; Brosseron, F.; Heneka, M.T.; Steinhäuser, C.; et al. Reactive Microglia Are the Major Source of Tumor Necrosis Factor Alpha and Contribute to Astrocyte Dysfunction and Acute Seizures in Experimental Temporal Lobe Epilepsy. Glia 2023, 71, 168–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.; Deshpande, T.; Henning, L.; Bedner, P.; Seifert, G.; Steinhäuser, C. Cell Death of Hippocampal CA1 Astrocytes during Early Epileptogenesis. Epilepsia 2021, 62, 1569–1583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Löscher, W.; Friedman, A. Structural, Molecular, and Functional Alterations of the Blood-Brain Barrier during Epileptogenesis and Epilepsy: A Cause, Consequence, or Both? International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2020, 21, 591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- David, Y.; Cacheaux, L.P.; Ivens, S.; Lapilover, E.; Heinemann, U.; Kaufer, D.; Friedman, A. Astrocytic Dysfunction in Epileptogenesis: Consequence of Altered Potassium and Glutamate Homeostasis? J. Neurosci. 2009, 29, 10588–10599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cacheaux, L.P.; Ivens, S.; David, Y.; Lakhter, A.J.; Bar-Klein, G.; Shapira, M.; Heinemann, U.; Friedman, A.; Kaufer, D. Transcriptome Profiling Reveals TGF-β Signaling Involvement in Epileptogenesis. J. Neurosci. 2009, 29, 8927–8935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Braganza, O.; Bedner, P.; Hüttmann, K.; von Staden, E.; Friedman, A.; Seifert, G.; Steinhäuser, C. Albumin Is Taken up by Hippocampal NG2 Cells and Astrocytes and Decreases Gap Junction Coupling. Epilepsia 2012, 53, 1898–1906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Henning, L.; Steinhäuser, C.; Bedner, P. Initiation of Experimental Temporal Lobe Epilepsy by Early Astrocyte Uncoupling Is Independent of TGFβR1/ALK5 Signaling. Front Neurol 2021, 12, 660591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Theis, M.; Jauch, R.; Zhuo, L.; Speidel, D.; Wallraff, A.; Döring, B.; Frisch, C.; Söhl, G.; Teubner, B.; Euwens, C.; et al. Accelerated Hippocampal Spreading Depression and Enhanced Locomotory Activity in Mice with Astrocyte-Directed Inactivation of Connexin43. J. Neurosci. 2003, 23, 766–776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teubner, B.; Michel, V.; Pesch, J.; Lautermann, J.; Cohen-Salmon, M.; Söhl, G.; Jahnke, K.; Winterhager, E.; Herberhold, C.; Hardelin, J.-P.; et al. Connexin30 (Gjb6)-Deficiency Causes Severe Hearing Impairment and Lack of Endocochlear Potential. Human Molecular Genetics 2003, 12, 13–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chever, O.; Dossi, E.; Pannasch, U.; Derangeon, M.; Rouach, N. Astroglial Networks Promote Neuronal Coordination. Sci. Signal. 2016, 9, ra6–ra6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deshpande, T.; Li, T.; Henning, L.; Wu, Z.; Müller, J.; Seifert, G.; Steinhäuser, C.; Bedner, P. Constitutive Deletion of Astrocytic Connexins Aggravates Kainate-Induced Epilepsy. Glia 2020, 68, 2136–2147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bedner, P.; Steinhäuser, C.; Theis, M. Functional Redundancy and Compensation among Members of Gap Junction Protein Families? Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Biomembranes 2012, 1818, 1971–1984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vessey, J.P.; Lalonde, M.R.; Mizan, H.A.; Welch, N.C.; Kelly, M.E.M.; Barnes, S. Carbenoxolone Inhibition of Voltage-Gated Ca Channels and Synaptic Transmission in the Retina. Journal of Neurophysiology 2004, 92, 1252–1256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suadicani, S.O.; Pina-Benabou, M.H.D.; Urban-Maldonado, M.; Spray, D.C.; Scemes, E. Acute Downregulation of Cx43 Alters P2Y Receptor Expression Levels in Mouse Spinal Cord Astrocytes. Glia 2003, 42, 160–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ransom, C.B.; Ye, Z.; Spain, W.J.; Richerson, G.B. Modulation of Tonic GABA Currents by Anion Channel and Connexin Hemichannel Antagonists. Neurochem Res 2017, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rekling, J.C.; Shao, X.M.; Feldman, J.L. Electrical Coupling and Excitatory Synaptic Transmission between Rhythmogenic Respiratory Neurons in the PreBötzinger Complex. J. Neurosci. 2000, 20, RC113–RC113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rouach, N.; Segal, M.; Koulakoff, A.; Giaume, C.; Avignone, E. Carbenoxolone Blockade of Neuronal Network Activity in Culture Is Not Mediated by an Action on Gap Junctions. The Journal of Physiology 2003, 553, 729–745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chepkova, A.N.; Sergeeva, O.A.; Haas, H.L. Carbenoxolone Impairs LTP and Blocks NMDA Receptors in Murine Hippocampus. Neuropharmacology 2008, 55, 139–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tovar, K.R.; Maher, B.J.; Westbrook, G.L. Direct Actions of Carbenoxolone on Synaptic Transmission and Neuronal Membrane Properties. Journal of Neurophysiology 2009, 102, 974–978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volnova, A.; Tsytsarev, V.; Ganina, O.; Vélez-Crespo, G.E.; Alves, J.M.; Ignashchenkova, A.; Inyushin, M. The Anti-Epileptic Effects of Carbenoxolone In Vitro and In Vivo. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2022, 23, 663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Onodera, M.; Meyer, J.; Furukawa, K.; Hiraoka, Y.; Aida, T.; Tanaka, K.; Tanaka, K.F.; Rose, C.R.; Matsui, K. Exacerbation of Epilepsy by Astrocyte Alkalization and Gap Junction Uncoupling. J. Neurosci. 2021, 41, 2106–2118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Engstrøm, T.; Nepper-Christensen, L.; Helqvist, S.; Kløvgaard, L.; Holmvang, L.; Jørgensen, E.; Pedersen, F.; Saunamaki, K.; Tilsted, H.-H.; Steensberg, A.; et al. Danegaptide for Primary Percutaneous Coronary Intervention in Acute Myocardial Infarction Patients: A Phase 2 Randomised Clinical Trial. Heart 2018, 104, 1593–1599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dhein, S.; Hagen, A.; Jozwiak, J.; Dietze, A.; Garbade, J.; Barten, M.; Kostelka, M.; Mohr, F.-W. Improving Cardiac Gap Junction Communication as a New Antiarrhythmic Mechanism: The Action of Antiarrhythmic Peptides. Naunyn-Schmied Arch Pharmacol 2010, 381, 221–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freitas-Andrade, M.; Bechberger, J.; Wang, J.; Yeung, K.K.C.; Whitehead, S.N.; Shultz Hansen, R.; Naus, C.C. Danegaptide Enhances Astrocyte Gap Junctional Coupling and Reduces Ischemic Reperfusion Brain Injury in Mice. Biomolecules 2020, 10, 353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).