Submitted:

27 January 2023

Posted:

30 January 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. Problem statement

1.2. Research questions

- How does degradation of Atiwa forest reserve affect the achievement of SDGs and increase poverty in the Eastern region?

- How does Sustainable Forest management ensure socioeconomic development?

- How does Sustainable Forest management ensure environmental development and preserves biodiversity?

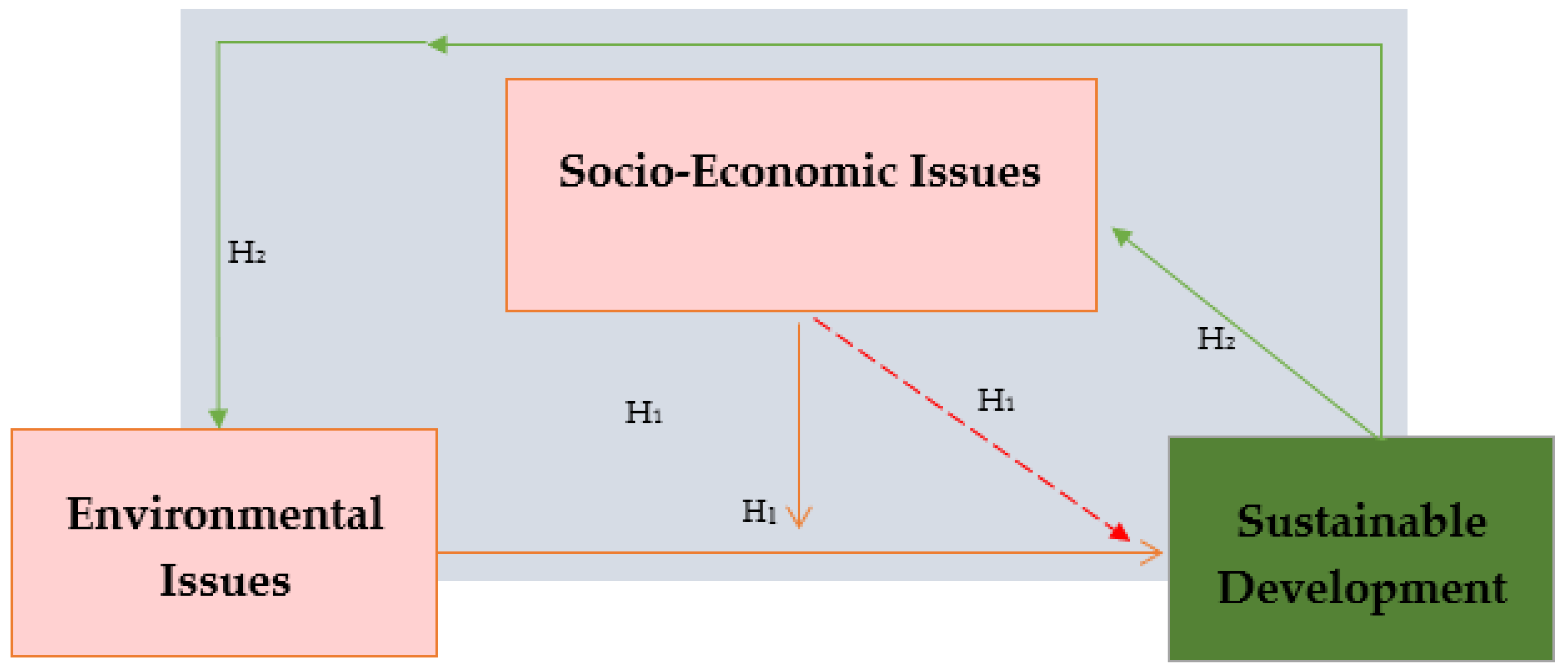

1.3. Conceptualization

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Guide for Focus Group Discussions

- Gender of participant

- Age of participant

- Occupation/sector

- Sources of goods

- What is/are your derivative(s) of the forests?

- What is your annual income range?

- Do you pay taxes?

- Means of tax payment.

- Do you know of any government policies regarding your business activities?

- Are you part of any recognized organization?

- What challenges do you face in your industry?

3. Results

3.1. Focus Group Discussion 1

3.2. Focus Group Discussion 2

4. Discussions

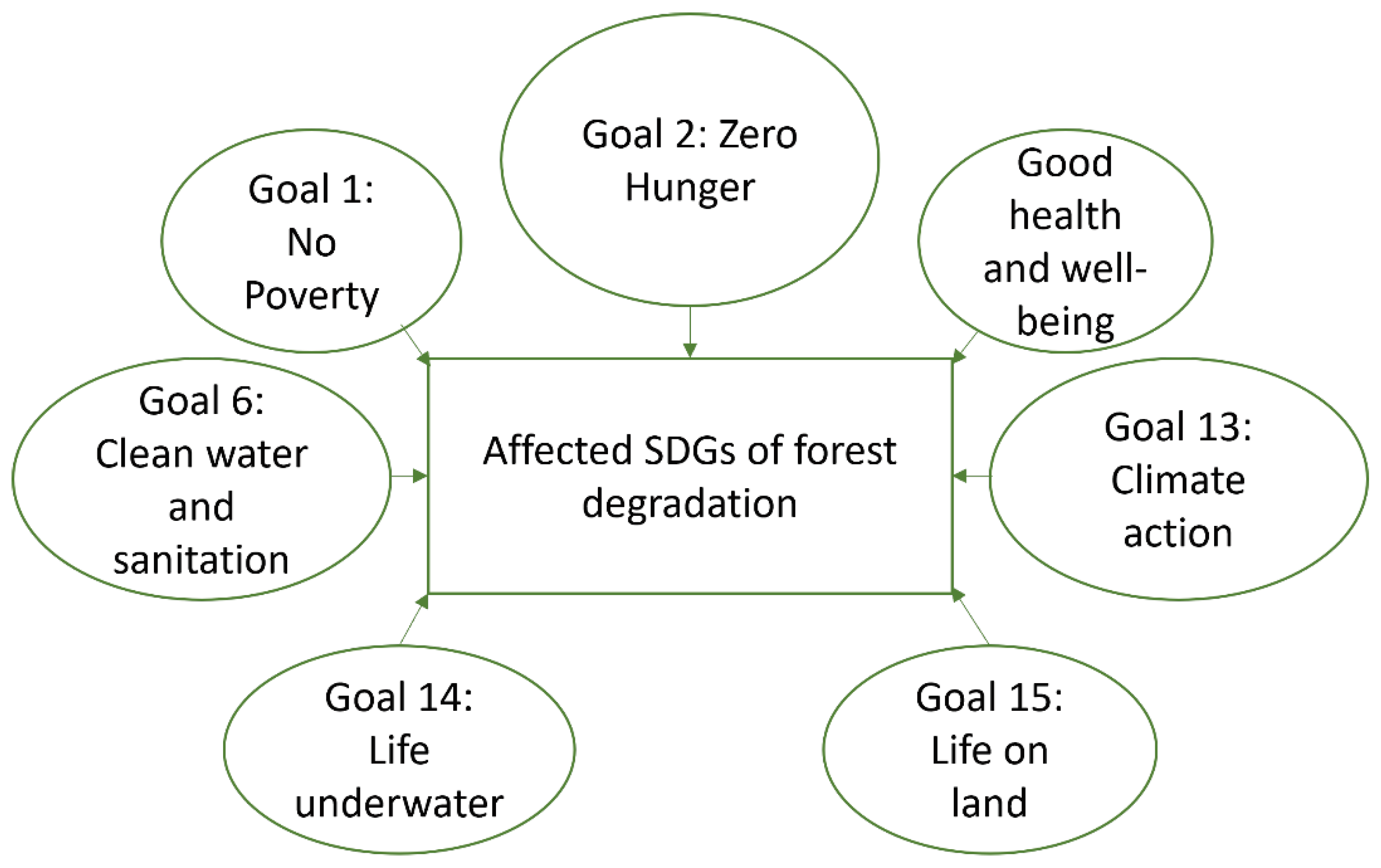

4.1. Degradation of Atiwa forest reserve and its impact on the achievement of SDGs and poverty in the Eastern Region

4.2. Sustainable Forest management and socioeconomic development.

4.3. Impact of Sustainable Forest management on environmental development and biodiversity preservation

5. Conclusions and policy recommendation

5.1. Sustainable, regulated, and authorized harvesting of NTFPs/ NWFPs

5.2. Community/User empowerment

5.3. Sectoral education and training programmes:

5.3.1. Education/trainings on mushroom farming

5.3.2. Plant medicine trainings for informal practitioners

5.3.3. Apicultural education/trainings in rural areas

5.4. Increasing Local Government powers for jobs creation

5.5. Adopting new measures to enforce existing policies

Appendix A

| Local/Twi name | Name of wood | Botanical Name |

|---|---|---|

| Sese | False rubber tree |

Holarrhena floribunda (G.Don) T.Durand & Schinz |

| Gyenegyene | Scented guarea | Guarea cedrata (A. Chev.) Pellegrin |

| Dua Tweneboa | Cordia | Cordia gandensis (S.Moore) |

| Hyedua | Daniellia | Daniellia ogea (Harms) Rolfe ex Holland |

| Esa | Natal white stinkwood | Celtis mildbraedii (Engl.) |

| Onyamedua | Stool wood | Alstonia boonei (De Wild.) |

| Odum | African teak | Milicia excelsa (Welw.) C.C. Berg |

| Mansonia | Mansonia | Mansonia altissima (A.Chev.) |

| Asamfena | Aningeria | Aningeria altissima (Aubrev. et Pellegr.) |

| Dahoma | Piptadenia | Piptadeniastrum africanum (Hook.f.) Brenan |

| Local/Twi Name | Name of Bushmeat | Binomial name |

|---|---|---|

| Otwe | Grey rhebok | Pelea capreolus (Forster) |

| Akranteɛ | Grasscutter | Thryonomys swinderianus (Temminck) |

| Aprawa | Ground Pangolin | Smutsia temminckii (Smuts) |

| Nwansane | Bushbuck | Tragelaphus scriptus (Pallas) |

| Kwakuo | Mangabey monkey | Cercocebus atys (Audebert) |

| Osanka | African Hog | Hylochoerus meinertzhageni (Thomas) |

| Adowa | Antilope/Dik Dik | Antilope saltiana (Desmarest) |

| Local/Twi Name | Plant name (Botanical name) | Medicinal uses |

|---|---|---|

| Tuoantini | Paullinia (Paullinia pinnata | waist pain, rheumatism, ulcer, sexual weakness, piles, impotency, bone fracture, fatigue, fever, stroke, HIV/AIDS |

| Kakapenpen | Mahogany (Khaya ivorensis) | cough, anaemia, fever, wounds, ulcers, and tumours, rheumatic symptoms, sores, lumbago. |

| Nim dua | African Neem (Azadirachta indica | tuberculosis, cancer, malaria, wounds, worm infections |

| Moringa | Moringa (Moringa oleifera) | ulcer, hypertension, fever, malaria, blood tonic, typhoid, urine retention, diarrhoea, bilharzia |

| Mmpampro | Schrad (Bambusa vulgaris) | Hypertension, malaria, cancer |

| Ahomakyem | Planch (adenia cissampeloides) | fever, wounds, numbness, gastro-intestinal disease hypertension, wound, malaria |

| Awobε or Abε aduro | (Phyllanthus floribundus) | wounds, inflammation, menstrual disorders, pains, fevers |

| Nyankama | Monkey fruit (Myrianthus arboreus) | reproduction, kidney pain, diabetes |

| Wisa | Black pepper (Piper nigrum) | cancers, malaria, excipient |

| Hwenetia | Ethiopian pepper (Xylopia aethiopica) | Stomach-ache, Chicken Pox, Bladder Trouble, Leprosy, Diabetes mellitus, Strengthening Pregnancy, Asthma, Mental illness, Convulsions, Arthritis, Inflammation |

References

- Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. Global Forest Resources Assessment 2000. Rome, Italy, 2014. Available online: http://www.fao.org/forest-resources-assessment/past-assessments/fra-2000/en/ (accessed on 9 July 2022).

- Dokken, T.; Angelsen, A. Forest reliance across poverty groups in Tanzania Ecological Economics, 2015, 117: 203-211. Available online: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolecon.2015.06.006 (accessed on 12 September 2022).

- Angelstam, P.; Elbakidze, M. Sustainable Forest management in Europe’s East and West: Trajectories of development and the role of traditional knowledge. International Union of Forest Research Organizations (IUFRO). Conference proceedings, 2006, 2, 76.

- Food and Agriculture Organisation. Forest products. FAO Statistics Yearbook, Rome, 2018. (ISSN 1020-458X).

- World Bank. SABER: Equity and Inclusion Brief, 2016. World Bank, Washington, DC. Available online: https://bit.ly/3zW9jJJ (accessed on 27 August 2022).

- FAO. Economic and social significance of forests for Africa’s sustainable development. Nature et Faune, 2011, 25(2). ISSN: 2026-5611. Available online: https://bit.ly/3OVwYxZ (accessed on 9 July 2022).

- Akomaning, Y.O. Effects of Degradation of the Atiwa Forest Reserved on the Socioeconomic Development of the Atiwa District of Ghana. Master’s Thesis, Mendel University in Brno, Brno, Czech Republic, 2018.

- International Energy Agency (IEA). World Energy outlook. Flagship report. 2013. Available online: https://www.iea.org/reports/world-energy-outlook-2013 (accessed on 7 June 2022).

- Food and Agriculture Organization. Global Forest Resources Assessment 2010; Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations: Rome, Italy, 2015. Available online: https://bit.ly/2ZpXIm5 (accessed on 9 July 2022).

- Gondo, P. Financing sustainable forest management in Africa: an overview of the current situation and experiences. Southern Alliance for Indigenous Resources (SAFIRE), 2010. Available online: https://bit.ly/3vBEY08 (accessed on 3 May 2022).

- FAO. State of the world’s forests 2016: Forests and agriculture: land use challenges and opportunities, Ghana. FAO, 2016, 125p, Rome, Italy, ISBN: 978-92-5-109208-8. Available online: https://bit.ly/3Jq1L4Z (accessed on 9 July 2022).

- Bondé, L.; Ouédraogo, O.; Traoré, S.; Thiombiano, A.; Boussim, J. I. Impact of environmental conditions on fruit production patterns of shea tree (Vitellaria paradoxaC.F.Gaertn) in West Africa. African Journal of Ecology, 2019, 57: 353-362.

- Ghana Statistical Service. Pattern and Trends of Poverty in Ghana. Accra: Ministry of Finance and Economic Planning, 2018.

- World Bank, Ghana Poverty Assessment. World Bank, 2020, Washington, DC. World Bank. Available online: https://bit.ly/3eqGdtw (accessed on 21 August 2022).

- McCullough, J; Alonso, E. L.; Naskrecki, P.; Wright, E. H.; Osei-Owusu, Y. An Ecological, Socio-Economic and Conservation Overview of the Atiwa Range Forest Reserve, Ghana. Conservation International, Center for Applied Biodiversity Science, 2007. Available online: https://bit.ly/2GP2jW1 (accessed on 1 September 2022).

- Ghana Business News. Reconsider the Decision to Mine in Atiwa Forest—CSOs to Government. [Online: 15 March 2019] Available online: https://bit.ly/3qFbMlp (accessed on 4 June 2022).

- Yoda, A. S. S. “We Have Cut Them All”: Ghana Struggles to Protect Its Last Old-Growth Forests. Mongabay Series: Forest Trackers, 2019. Available online: https://bit.ly/2GVf9C1 (accessed on 4 July 2022).

- Birdlife International. Major Manufacturing Companies Oppose Mining in Atiwa Forest, Ghana. Available online: https://bit.ly/2ZHOrD2 (accessed on 10 August 2022).

- Mishra, L. Focus Group Discussion in Qualitative Research. Journal on Educational Technology, 2016, 6: 1-5. [CrossRef]

- Krueger, R. A.; Casey, M. A. Focus groups: A practical guide for applied research. 2008, 4th edition. New York: SAGE.

- Muijeen, K.; Kongvattananon, P.; Somprasert, C. "The key success factors in focus group discussions with the elderly for novice researchers: a review", Journal of Health Research, 2020, 34: 4, 359-371. [CrossRef]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Thematic analysis. In H. Cooper, P. M. Camic, D. L. Long, A. T. Panter, D. Rindskopf, and K. J. Sher (Eds), APA handbook of research methods inpsychology, 2, Research designs: Quantitative, qualitative, neuropsychological, and biological (57-71), 2012, American Psychological Association. Washington, DC.

- United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs (UNDESA). UN International Strategy for Disaster Reduction (UNISDR), 2008, Available online: https://bit.ly/3o6wUSn (accessed on 17 September 2022).

- Mohr, J. A. Toolkit for Mapping Relationships among the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), 2016, Available online: https://bit.ly/36MQM2M (accessed on 17 July 2022).

- Akomaning, Y.O.; Hlaváčková, P.; Darkwah, S.A.; Živělová, I.; Sujová, A. Socioeconomic Impact of Mining in the Atiwa Forest Reserve of Ghana on Fringe Communities and the Achievement of SDGs: Analysis from the Residents’ Perspective. Forests 2021, 12, 1395. [CrossRef]

- Nyame, F. K.; Grant, J. A.; Yakovleva, N. Perspectives on migration patterns in Ghana’s mining industry. Resour. Policy, 2009, 34: 6–11. [CrossRef]

- Verma, S. K.; Paul, S. K. Sustaining the non-timber forest products (NTFPs) based rural livelihood of tribal’s in Jharkhand: Issues and challenges. Jharkhand J Dev Manag Stud., 2016, 14: 6865-6883.

- Ammal, A.; Mariam, M. Contribution of non-timber forest products to livelihood of rural communities in Kumbungu District of Northern Ghana. Asian J For, 2020, 4: 10-14.

- Kamanga, P.; Vedeld, P.; Sjaastad, E. Forest incomes and rural livelihoods in Chiradzulu District, Malawi. Ecological Economics, 2009, 68: 613-624. [CrossRef]

- IUCN. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2022, Version 2022-1. ISSN 2307-8235. Available online: https://bit.ly/3SsHI9Z (accessed on 3 September 2022).

- Millennium Ecosystem Assessment Board (MEAB). Ecosystems and Human Well-Being: Policy Responses, 2005, Volume 3. Available online: https://wedocs.unep.org/20.500.11822/7848 (Accessed on 3 March 2022).

- Nasi, R.; Brown, D.; Wilkie, D.; Bennett, E.; Tutin, C.; van Tol, G.; Christophersen, T. Conservation and use of wildlife-based resources: the bushmeat crisis. CBD Technical Series No.33. Montreal, Canada, Secretariat of the Convention on Biological Diversity and Center for International Forestry Research (CIFOR), Bogor, Indonesia, 2008, 50p. ISBN: 92-9225-083-3.

- United Nations. Resolution adopted by the General Assembly 62/98: Non legally binding instruments on all types of forests, 2008. Available online: https://bit.ly/3oVzaep (accessed on 30 September 2022).

- D’Cruze, N.; Assou, D.; Coulthard, E.; Norrey, J.; Megson, D.; Macdonald, D. W.; Harrington, L. A.; Ronfot, D.; Segniagbeto, G. H.; Auliya, M. Snake oil and pangolin scales: insights into wild animal use at “Marché des Fétiches” traditional medicine market, Togo. Nature Conservation 39, 2020, 45-71. [CrossRef]

- Ahenkan. A.; Boon, E. K. Non-Timber Forest Products (NTFPs): Clearing the Confusion in Semantics. Journal of Human Ecology. 2011. Vol. 33, pp 1 - 9. [CrossRef]

- Barimah, K. B. Traditional healers in Ghana: So near to the people, yet so far away from basic health care system. Humanitas Medicine, 2016, 6(2): 1-6. [CrossRef]

- Kiros, W.; Tsegay, T. Honey-bee production practices and hive technology preferences in Jimma and Illubabor Zone of Oromiya Regional State, Ethiopia. Acta Universitatis Sapientiae, Agriculture and Environment, 2017, 9(1), pp 31-43. [CrossRef]

- Hanspal, J. Ghana: Can bees be key to sweetening the economy? The Africa Report.Com, 2022. Available online: https://bit.ly/3bqRj0n (accessed on 29 September 2022).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).