Submitted:

17 February 2023

Posted:

17 February 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

| Ref. | TJ structure | Growth method | VF (V) | Rs (Ωcm2) |

| [20] | n+-GaN/GaInN/p+-GaN | PAMBE | 3.05 @100 A/cm2 | 1.2 × 10-4 |

| [21] | n+-GaN/p+-Ga0.6In0.4N | MOVPE | 4.0 × 10-3 | |

| [22] | n+-GaN/p+-GaN | MOVPE+NH3-MBE | ~5 @100 A/cm2 | 2.3 × 10-4 |

| [23] | n+-GaN/p+-GaN | MOVPE | 5.92 @2 A/cm2 | 2.6 × 10-1 |

| [24] | n+-GaN/p+-GaN µ-LED | MOVPE | ~4 @20 A/cm2 | 2.5 × 10-5 |

| [25] | n+-GaN/p+-GaN | MOVPE | ~4 @100 A/cm2 | 2.4 × 10-4 |

| [26] | n+-Al0.55Ga0.45N/ Ga0.8In0.2N /p+-Al0.55Ga0.45N |

PAMBE | 6.8 @10 A/cm2 | 1.5 × 10-3 |

| [27] | n+-AlGaN/ Ga0.8In0.2N /graded p-AlGaN |

PAMBE | 10.2 @10 A/cm2 | N/A |

| [28] | graded n+-AlGaN / Ga0.8In0.2N/p+-Al0.65Ga0.35N |

PAMBE | 10.5 @20 A/cm2 | 1.9 × 10-3 |

| [29] | n+-Al0.65Ga0.35N/GaN /p+-Al0.65Ga0.35N |

PAMBE | ~10 @100 A/cm2 | N/A |

| [30] | n+-Al0.5Ga0.5N/GaN /p+-Al0.5Ga0.5N |

MOVPE+NH3-MBE | ~9 @100 A/cm2 | 1.2 × 10-3 |

| [30] | n+-Al0.5Ga0.5N/p+-Al0.5Ga0.5N | MOVPE+NH3-MBE | ~11 @100 A/cm2 | 1.7 × 10-3 |

| [31] | n+-Al0.65Ga0.35N/n+-GaN /p+-Al0.65Ga0.35N |

MOVPE | ~20 | (4-6) × 10-3 |

| [31] | n+-Al0.65Ga0.35N /p+-Al0.65Ga0.35N |

MOVPE | ~50 | N/A |

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results and Discussions

3.1. AlGaN homoepitaxial tunnel-junction deep-UV LEDs with n-type AlGaN based on suppressed complex defect formation

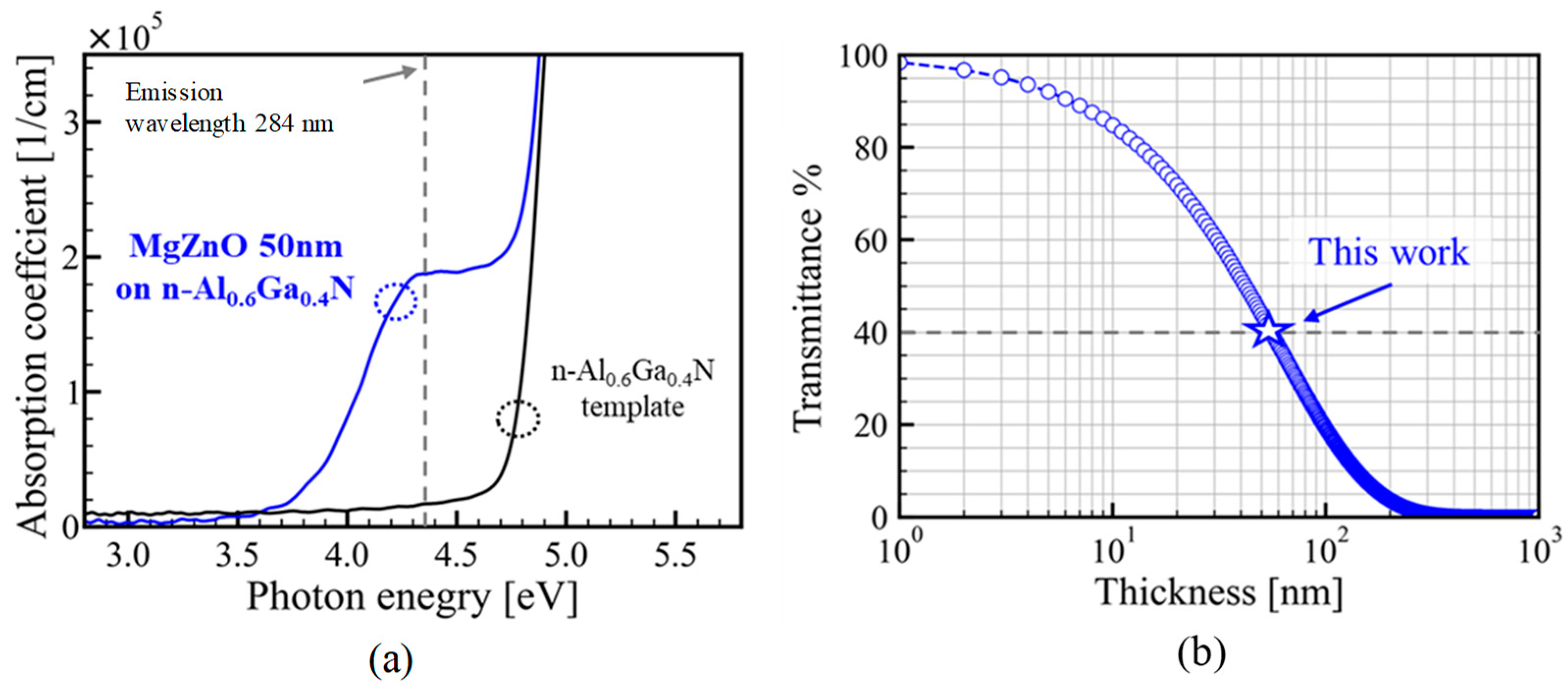

3.2. Sputtered polycrystalline MgZnO/Al reflective electrodes for enhanced light emission in AlGaN-based homoepitaxial tunnel junction DUV-LED

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Informed Consent Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Oguma, K.; Rattanakul, S. UV inactivation of viruses in water: its potential to mitigate current and future threats of viral infectious diseases. Jpn. J. Appl. Phys. 2021, 60, 110502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minamikawa, T.; Koma, T.; Suzuki, A.; Nagamatsu, K.; Yasui, T.; Yasutomo, K.; Nomaguchi, M. Inactivation of SARS-CoV-2 by deep ultraviolet light emitting diode: A review. Jpn. J. Appl. Phys. 2021, 60, 090501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muramoto, Y.; Kimura, M.; Kondo, A. Verification of inactivation effect of deep-ultraviolet LEDs on bacteria and viruses, and consideration of effective irradiation methods. Jpn. J. Appl. Phys. 2021, 60, 090601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inagaki, H.; Saito, A.; Sugiyama, H.; Okabayashi, T.; Fujimoto, S. Rapid inactivation of SARS-CoV-2 with deep-UV LED irradiation. Emerging Microbes Infect. 2020, 9, 1744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saito, Y.; Wada, S.; Nagata, K.; Makino, H.; Boyama, S.; Miwa, H.; Matsui, S.; Kataoka, K.; Narita, T.; Horibuchi, K. Efficiency improvement of AlGaN-based deep-ultraviolet light-emitting diodes and their virus inactivation application. Jpn. J. Appl. Phys. 2021, 60, 080501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amano, H.; Collazo, R.; Santi, C. D.; Einfeldt, S.; Funato, M.; Glaab, J.; Hagedorn, S.; Hirano, A.; Hirayama, H.; Ishii, R.; Kashima, Y.; Kawakami, Y.; Kirste, R.; Kneissl, M.; Martin, R.; Mehnke, F.; Meneghini, M.; Ougazzaden, A.; J Parbrook, P.; Rajan, S.; Reddy, P.; Römer, F.; Rusche, J.; Sarkar, B.; Scholz, F.; J Schowalter, L. Shields, P.; Sitar, Z.; Sulmoni, L.; Wang, T.; Wernicke, T.; Weyers, M.; Witzigmann, B.; Wu, Y.; Wunderer, T.; and Zhang, Y.; The 2020 UV emitter roadmap. J. Phys. D: Appl. Phys. 2020, 53, 503001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ichikawa, M.; Endo, S.; Sagawa, H.; Fujioka, A.; Kosugi, T.; Mukai, T.; Uomoto, M.; Shimatsu, T. High-output-power deep ultraviolet light-emitting diode assembly using direct bonding. ECS Trans. 2016, 75, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muth, J. F.; Brown, J. D.; Johnson, M. A. L.; Yu, Z.; Kolbas, R. M.; Cook, Jr J. W.; Schetzina, J. F. Absorption coefficient and refractive index of GaN, AlN and AlGaN alloys. MRS Internet J. Nitride Semicond. Res. 1999, 4S1, G5.2. [Google Scholar]

- Katsuragawa, M.; Sota, S.; Komori, M.; Anbe, C.; Takeuchi, T.; Sakai, H.; Amano, H.; Akasaki, I. Thermal ionization energy of Si and Mg in AlGaN. J. Cryst. Growth 1998, 189/190, 528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeon, S. R.; Ren, Z.; Cui, G.; Su, J.; Gherasimova, M.; Han, J.; Cho, H. K.; Zhou, L. Investigation of Mg doping in high-Al content 𝑝-type Al𝑥Ga1−𝑥N. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2005, 86, 082107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakarmi, M. L.; Kim, K. H.; Khizar, M.; Fan, Z. Y.; Lin, J. Y.; Jiang, H. X. Electrical and optical properties of Mg-dopedAl0.7Ga 0.3N alloys. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2005, 86, 092108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakarmi, M. L.; Nepal, N.; Ugolini, C.; Altahtamouni, T. M.; Lin, J. Y.; Jiang, H. X. Correlation between optical and electrical properties of Mg-doped AlN epilayers. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2006, 89, 152120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szabó, Á; Son, N. T.; Janzén, E.; Gali, A. Stampfl, C.; Neugebauer, J.; Group-II acceptors in wurtzite AlN: A screened hybrid density functional study. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2010, 96, 192110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyons, J. L.; Janotti, A.; Van de Walle, C. G. Shallow versus Deep Nature of Mg Acceptors in Nitride Semiconductors. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2012, 108, 156403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takano, T.; Mino, T.; Sakai, J.; Noguchi, N.; Tsubaki, K.; Hirayama, H. Deep-ultraviolet light-emitting diodes with external quantum efficiency higher than 20% at 275 nm achieved by improving light-extraction efficiency. Appl. Phys. Exp. 2017, 10, 03100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.Y.; Han, D.S.; Lee, Y.G.; Choi, K.K.; Oh, J.T.; Jeong, H.H.; Seong, T.Y.; Amano, H. Heavy Mg doping to form reliable Rh reflective ohmic contact for 278 nm deep ultraviolet AlGaN-based light-emitting diodes. ECS J. Solid State Sci. Technol. 2020, 9, 065016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- France, R.; Xu, T.; Chen, P.; Chandrasekaran, R.; Moustakas, T. Vanadium-based Ohmic contacts to n-AlGaN in the entire alloy composition. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2007, 90, 062115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mori, K.; Takeda, K.; Kusafuka, T.; Iwaya, M.; Takeuchi, T.; Kamiyama, S.; Akasaki, I.; Amano, H. Low-ohmic-contact-resistance V-based electrode for n-type AlGaN with high AlN molar fraction. Jpn. J. Appl. Phys. 2016, 55, 05FL03. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagata, N.; Senga, T.; Iwaya, M.; Takeuchi, T.; Kamiyama, S.; Akasaki. I. Reduction of contact resistance in V-based electrode for high AlN molar fraction n-type AlGaN by using thin SiNx intermediate layer. Phys. Status Solidi c 2016, 14, 1600243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krishnamoorthy, S.; Akyol, F.; Park, P.S.; Rajan, S. Low resistance GaN/InGaN/GaN tunnel junctions. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2013, 102, 113503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minamikawa, D.; Ino, M.; Kawai, S.; Takeuchi, T.; Kamiyama, S.; Iwaya, M.; Akasaki, I. GaInN-based tunnel junctions with high InN mole fractions grown by MOVPE. Phys. Status Solidi B 2014, 252, 1127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yonkee, B.P.; Young, E.C.; Lee, C.; Leonard, J.T.; DenBaars, S.P; Speck, J.S.; Nakamura, S. Demonstration of a III-nitride edge-emitting laser diode utilizing a GaN tunnel junction contact. Opt. Express 2016, 24, 7816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neugebauer, S.; Hoffmann, M.P.; Witte, H.; Bläsing, J.; Dadgar, A.; Strittmatter, A.; Niermann, T.; Narodovitch, M.; Lehmann, M. All metalorganic chemical vapor phase epitaxy of p/n-GaN tunnel junction for blue light emitting diode applications. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2017, 110, 102104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, D.; Mughal, A.J.; Wong, M.S.; Alhassan, A.I.; Nakamura, S.; DenBaars, S.P. Micro-light-emitting diodes with III–nitride tunnel junction contacts grown by metalorganic chemical vapor deposition. Appl. Phys. Exp. 2018, 11, 012102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akatsuka, Y.; Iwayama, S.; Takeuchi, T.; Kamiyama, S.; Iwaya, M.; Akasaki, I. Doping profiles in low resistive GaN tunnel junctions grown by metalorganic vapor phase epitaxy. Appl. Phys. Exp. 2019, 12, 025502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Krishnamoorthy, Y.; Akyol, F.; Allerman, A.A.; Moseley, M.W.; Armstrong, A.M.; Rajan, S. Design and demonstration of ultra-wide bandgap AlGaN tunnel junctions. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2016, 109, 121102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Krishnamoorthy, S.; Akyol, F.; Bajaj, S.; Allerman, A.A.; Moseley, M.W.; Armstrong, A.M.; Rajan, S. Tunnel-injected sub-260 nm ultraviolet light emitting diodes. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2017, 110, 201102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Jamal-Eddine, Z.; Akyol, F.; Bajaj, S.; Johnson, J.M.; Calderon, G.; Allerman, A.A.; Moseley, M.W.; Armstrong, A.M.; Hwang, J.; Rajan, S. Tunnel-injected sub 290 nm ultra-violet light emitting diodes with 2.8% external quantum efficiency. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2018, 112, 071107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandey, A.; Shin, W.J.; Gim, J.; Hovden, R.; Mi, Z. High-efficiency AlGaN/GaN/AlGaN tunnel junction ultraviolet light-emitting diodes. Photon. Res. 2020, 8, 331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan Arcara, V.; Damilano, B.; Feuillet, G.; Vézian, S.; Ayadi, K.; Chenot, S.; Duboz, J.Y. Ge doped GaN and Al0.5Ga0.5N-based tunnel junctions on top of visible and UV light emitting diodes. J. Appl. Phys. 2019, 126, 224503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuhn, C.; Sulmoni, L.; Guttmann, M.; Glaab, J.; Susilo, N.; Wernicke, T.; Weyers, M.; Kneissl, M. MOVPE-grown AlGaN-based tunnel heterojunctions enabling fully transparent UVC LEDs. Photon. Res. 2019, 7, B7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakamura, S.; Mukai, T.; Senoh, M.; Iwasa, N. Thermal annealing effects on P-type Mg-doped GaN Films. Jpn. J. Appl. Phys. 1992, 31, L139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakamura, S.; Iwasa, N. , Senoh, M.S.; Mukai, T. Hole compensation mechanism of P-type GaN Films. Jpn. J. Appl. Phys. 1992, 31, 1258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Limpijumnong, S.; Northrup, J.E.; Van de Walle, C.G. Identification of hydrogen configurations in p-type GaN through first-principles calculations of vibrational frequencies. Phys. Rev. B 2003, 68, 075206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narita, T.; Yoshida, H.; Tomita, K.; Kataoka, K.; Sakurai, H.; Horita, M.; Bockowski, M.; Ikarashi, N.; Suda, J.; Kachi, T.; Tokuda, Y. Progress on and challenges of p-type formation for GaN power devices. J. Appl. Phys. 2020, 128, 090901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nam, K. B.; Nakarmi, M. L.; Lin, J. Y.; Jiang, H. X. Photoluminescence studies of Si-doped AlN epilayers. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2005, 86, 222108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nepal, N.; Nakarmi, M. L.; Lin, J. Y.; Jiang, H. X. Photoluminescence studies of impurity transitions in AlGaN alloys. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2006, 89, 092107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chichibu, S. F.; Miyake, H.; Ishikawa, Y.; Tashiro, M.; Ohtomo, T.; Furusawa, K.; Hazu, K.; Hiramatsu, K.; Uedono, A. The origins and properties of intrinsic nonradiative recombination centers in wide bandgap GaN and AlGaN. J. Appl. Phys. 2013, 113, 213506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryan, I.; Bryan, Z.; Washiyama, S.; Reddy, P.; Gaddy, B.; Sarkar, B.; Breckenridge, M. H.; Guo, Q.; Bobea, M.; Tweedie, J.; Mita, S.; Irving, D.; Collazo, R.; Sitar, Z. The role of transient surface morphology on composition control in AlGaN layers and wells. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2018, 112, 062102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

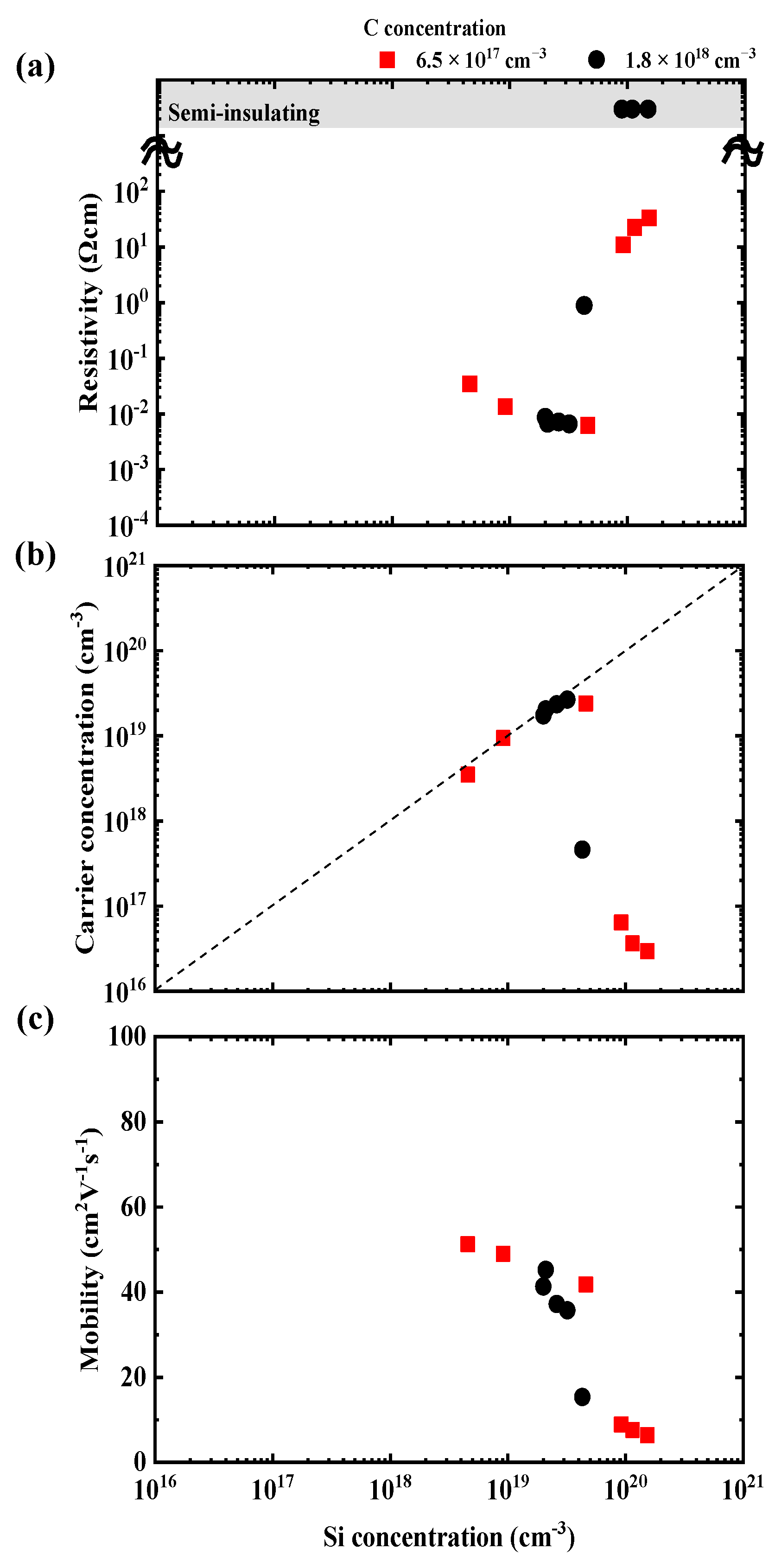

- Nagata, K.; Makino, H.; Yamamoto, T.; Kataoka, K.; Narita, T.; Saito, Y. Low resistivity of highly Si-doped n-type Al0.62Ga0.38N layer by suppressing self-compensation. Appl. Phys. Exp. 2020, 13, 025504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kataoka, K.; Narita, T.; Nagata, K.; Makino, H.; Saito, Y. Electronic degeneracy conduction in highly Si-doped Al0.6Ga0.4N layers based on the carrier compensation effect. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2020, 117, 262103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piao, G.; Ikenaga, K.; Yano, Y.; Tokunaga, H.; Mishima, A.; Ban, Y.; Tabuchi, T.; Matsumoto, K. Study of carbon concentration in GaN grown by metalorganic chemical vapor deposition. J. Cryst. Growth 2016, 456, 137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sawada, N.; Narita, T.; Kanechika, M.; Uesugi, T.; Kachi, T.; Horita, M.; Kimoto, T.; Suda, J. Sources of carrier compensation in metalorganic vapor phase epitaxy-grown homoepitaxial n-type GaN layers with various doping concentrations. Appl. Phys. Exp. 2018, 11, 041001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanegae, K.; Fujikura, H.; Otoki, Y.; Konno, T.; Yoshida, T.; Horita, M.; Kimoto, T.; Suda, J. Deep-level transient spectroscopy studies of electron and hole traps in n-type GaN homoepitaxial layers grown by quartz-free hydride-vapor-phase epitaxy. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2019, 115, 012103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narita, T.; Tomita, K.; Kataoka, K.; Tokuda, Y.; Kogiso, T.; Yoshida, H.; Ikarashi, N.; Iwata, K.; Nagao, M.; Sawada, N.; Horita, M.; Suda, J.; Kachi, T. Overview of carrier compensation in GaN layers grown by MOVPE: toward the application of vertical power devices. Jpn. J. Appl. Phys. 2020, 59, SA0804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyons, J.L.; Janotti, A.; Van de Walle, C.G. Effects of carbon on the electrical and optical properties of InN, GaN, and AlN. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2014, 89, 035204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagasawa, Y.; Hirano, A. A review of AlGaN-based deep-ultraviolet light-emitting diodes on sapphire. Appl. Sci. 2018, 8, 1264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ichikawa, M.; Fujioka, A.; Kosugi, T.; Endo, S.; Sagawa, H.; Tamaki, H.; Mukai, T.; Uomoto, M.; Shimatsu, T. High-output-power deep ultraviolet light-emitting diode assembly using direct bonding. Appl. Phys. Exp. 2016, 9, 072101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, S.; Liu, X.; Gao, Y.; Liu, Y.; Liu, M.; Liu, Z.; Gui, C.; Liu, S. Numerical and experimental investigation of GaN-based flip-chip light-emitting diodes with highly reflective Ag/TiW and ITO/DBR Ohmic contacts. Opt. Exp. 2017, 25, 26615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, S.; Zheng, C.; Lv, J.; Gao, Y.; Wang, R.; Liu, S. GaN-based flip-chip LEDs with highly reflective ITO/DBR p-type and via hole-based n-type contacts for enhanced current spreading and light extraction. Opt. Laser Technol. 2017, 92, 95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mizuhashi, M. Electrical properties of vacuum-deposited indium oxide and indium tin oxide films. Thin Solid Films, 1980, 70, 91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Wu, D.; Zeng, S. Influence of temperature and layers on the characterization of ITO films. J. Mater. Process Technol. 2009, 209, 3943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.; Chaudhary, S.; Pandya, D.K. High conductivity indium doped ZnO films by metal target reactive co-sputtering. Acta Materialia 2016, 111, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Y.; Miao, L.; Tanemura, S.; Tanemura, M.; Kuno, Y.; Hayashi, Y.; Mori, Y. Optical properties of indium-doped ZnO films. Jpn. J. Appl. Phys. 2006, 45, 1623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, P.M.R.; Kartha, C.S.; Vijayakumar, K.P.; Abe, T.; Kashiwaba, Y.; Singh, F.; Avasthi, D.K. On the properties of indium doped ZnO thin films. Semicond. Sci. Technol. 2005, 20, 120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahmane, S.; Djouadi, M.A.; Aida, M.S.; Barreau, N.; Abdallah, B.; Hadj Zoubir, N. Power and pressure effects upon magnetron sputtered aluminum doped ZnO films properties. Thin Solid Films 2010, 519, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiménez-González, A.E.; Urueta, J.A.S.; Suárez-Parra, R. Optical and electrical characteristics of aluminum-doped ZnO thin films prepared by solgel technique. J. Cryst. Growth 1998, 192, 430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minami, T.; Miyata, T.; Yamamoto, T.; Toda, H. Origin of electrical property distribution on the surface of ZnO:Al films prepared by magnetron sputtering. J. Vac. Sci. Technol. A 2000, 18, 1584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, B.H.; Im, H.B.; Song, J.S.; Yoon, K.H. Optical and electrical properties of Ga2O3-doped ZnO films prepared by r.f. sputtering. Thin Solid Films 1990, 193-194, 712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, P.K.; Watanabe, M.; Kon, M.; Mitsui, A.; Shigesato, Y. Electrical and optical properties of gallium-doped zinc oxide films deposited by dc magnetron sputtering. Thin Solid Films 2002, 411, 82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Saito, K.; Tanaka, T.; Nishio, M.; Nagaoka, T.; Arita, M.; Guo, Q. Energy band bowing parameter in MgZnO alloys. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2015, 107, 022111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Saito, K.; Tanaka, T.; Nishio, M.; Guo, Q. Lower temperature growth of single phase MgZnO films in all Mg content range. J. Alloys Compd. 2015, 627, 383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kushimoto, M.; Sakai, T.; Ueoka, Y.; Tomai, S.; Katsumata, S.; Deki, M.; Honda, Y.; Amano, H. Effect of annealing on the electrical and optical properties of MgZnO films deposited by radio frequency magnetron sputtering. Phys. Status Solidi A 2020, 217, 1900955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borysiewicz, M.A.; Wzorek, M.; Gołaszewska, K.; Kruszka, R.; Pągowska, K.D.; Kamińska, E. Nanocrystalline sputter-deposited ZnMgO:Al transparent p-type electrode in GaN-based 385 nm UV LED for significant emission enhancement. Materials Science and Engineering: B 2015, 200, 93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borysiewicz, M.A. ZnO as a functional material, a review. Crystals 2019, 9, 505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imura, M.; Nakano, K.; Fujimoto, N.; Okada, N.; Balakrishnan, K.; Iwaya, M.; Kamiyama, S.; Amano, H.; Akasaki, I.; Noro, T.; Takagi, T.; Bandoh, A. Dislocations in AlN Epilayers Grown on Sapphire Substrate by High-Temperature Metal-Organic Vapor Phase Epitaxy. Jpn. J. Appl. Phys. 2007, 46, 1458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagata, K.; Makino, H.; Yamamoto, T.; Saito, Y.; Miki, H. Origin of optical absorption in AlN with air voids. Jpn. J. Appl. Phys. 2019, 58, SCCC29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuwano, Y.; Kaga, M.; Morita, T.; Yamashita, K.; Yagi, K.; Iwaya, M.; Takeuchi, T.; Kamiyama, S.; Akasaki, I. Lateral hydrogen diffusion at p-GaN layers in nitride-based light emitting diodes with tunnel junctions. Jpn. J. Appl. Phys. 2013, 52, 08JK12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alhassan, A. I.; Young, E. C.; Alyamani, A. Y.; Albadri, A.; Nakamura, S.; DenBaars, S. P.; Speck, J. S. Reduced-droop green III–nitride light-emitting diodes utilizing GaN tunnel junction. Appl. Phys. Exp. 2018, 11, 042101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narita, T.; Tomita, K.; Yamada, S.; Kachi, T. Quantitative investigation of the lateral diffusion of hydrogen in p-type GaN layers having NPN structures. Appl. Phys. Exp. 2019, 12, 011006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

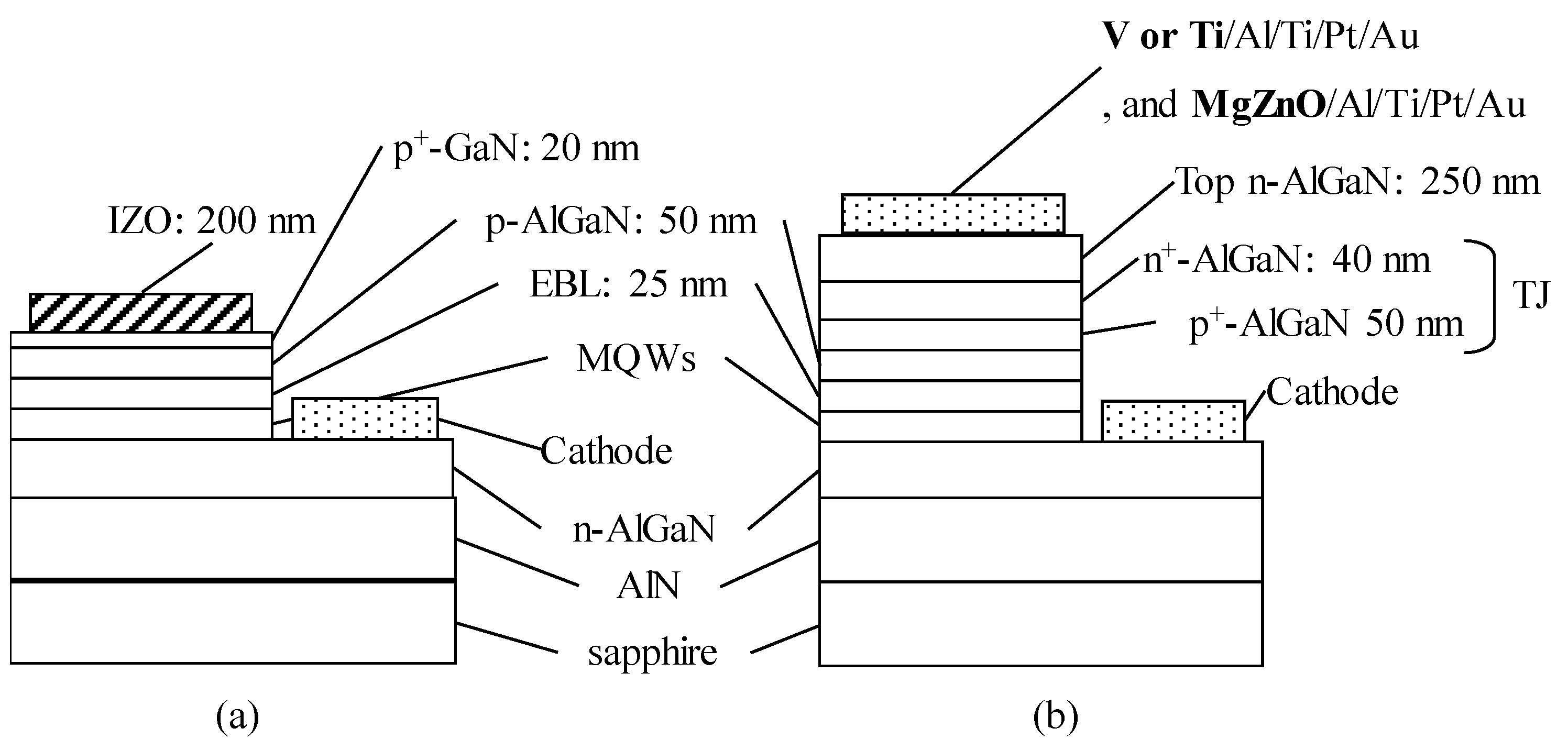

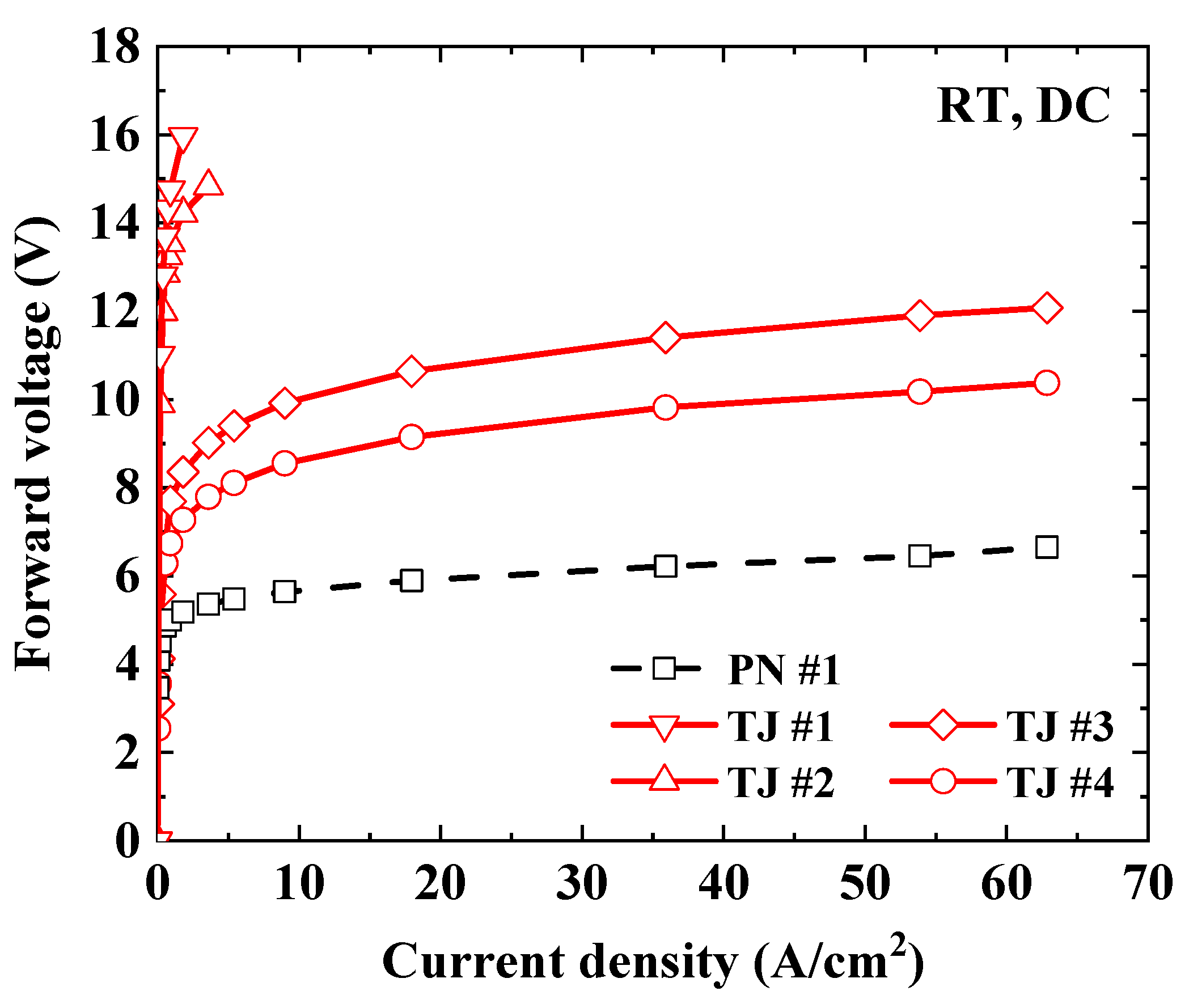

- Nagata, K.; Makino, H.; Miwa, H.; Matsui, S.; Boyama, S.; Saito, Y.; Kushimoto, M.; Honda, Y.; Takeuchi, T.; Amano, H. Reduction in operating voltage of AlGaN homojunction tunnel junction deep-UV light-emitting diodes by controlling impurity concentrations. Appl. Phys. Exp. 2021, 14, 084001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inazu, T.; Fukahori, S.; Pernot, C.; Kim, M. H.; Fujita, T.; Nagasawa, Y.; Hirano, A.; Ippommatsu, M.; Iwaya, M.; Takeuchi, T.; Kamiyama, S.; Yamaguchi, M. Honda, Y.; Amano, H.; Akasaki, I. Improvement of light extraction efficiency for AlGaN-based deep ultraviolet light-emitting diodes. Jpn. J. Appl. Phys. 2011, 50, 122101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sung, Y. J.; Kim, M.; Kim, H.; Choi, S.; Kim, Y. H.; Jung, M.; Choi, R.; Moon, Y.; Oh, J.; Jeong, H.; Yeom, G. Y. Light extraction enhancement of AlGaN-based vertical type deep-ultraviolet light-emitting-diodes by using highly reflective ITO/Al electrode and surface roughening. Opt. Exp. 2019, 27, 29930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nagata, K.; Anada, S.; Saito, Y.; Kushimoto, M.; Honda, Y.; Takeuchi, T.; Yamamoto, K.; Hirayama, T.; Amano, H. Visualization of depletion layer in AlGaN homojunction p–n junction. Appl. Phys. Exp. 2022, 15, 036504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagata, K.; Anada, S.; Miwa, H.; Matsui, S.; Boyama, S.; Saito, Y.; Kushimoto, M.; Honda, Y.; Takeuchi, T.; Amano, H. Structural design optimization of 279 nm wavelength AlGaN homojunction tunnel junction deep-UV light-emitting diode. Appl. Phys. Exp. 2022, 15, 044003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

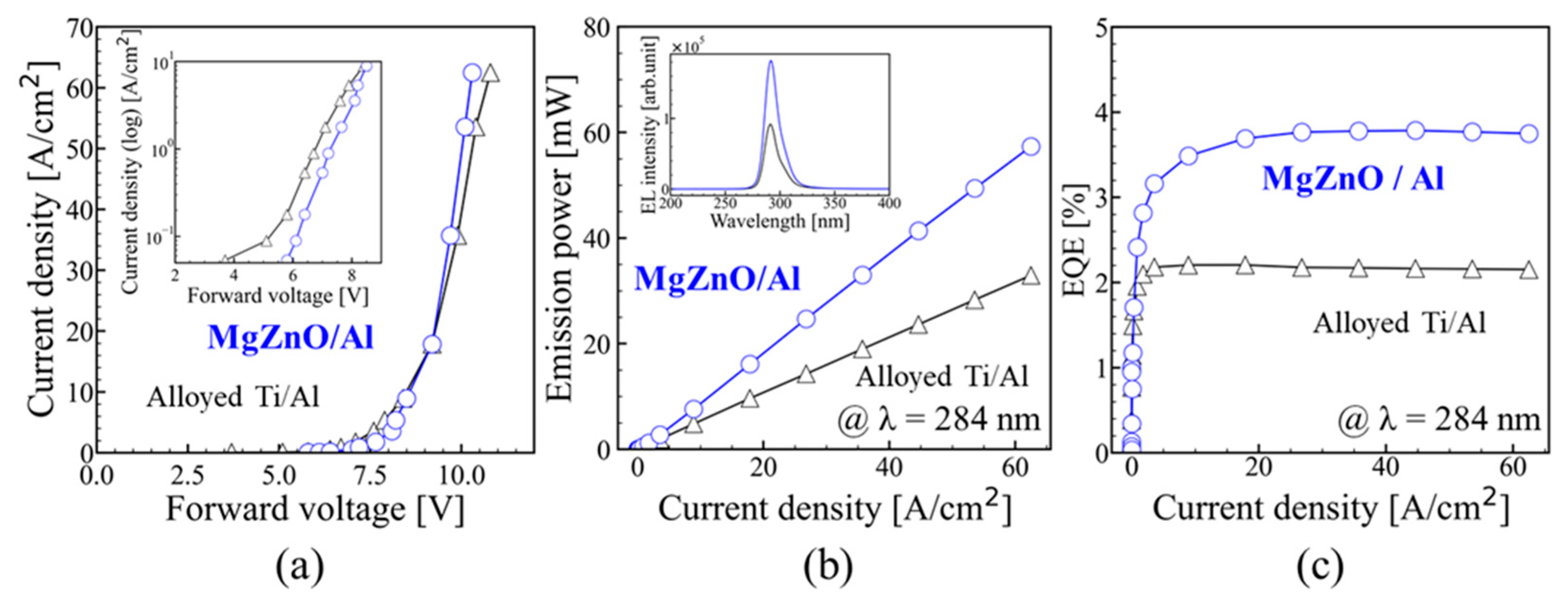

- Matsubara, T.; Nagata, K.; Kushimoto, M.; Tomai, S.; Katsumata, S.; Honda, Y.; Amano, H. Sputtered polycrystalline MgZnO/Al reflective electrodes for enhanced light emission in AlGaN-based homojunction tunnel junction DUV-LED. Appl. Phys. Exp. 2022, 15, 044001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen Y., C.; Wierer, J. J.; Krames, M. R.; Ludowise, M. J.; Misra, M. S.; Ahmed, F. Kim, A. Y.; Mueller, G. O.; Bhat, J. C.; Stockman, S. A.; Martin, P. S. Optical cavity effects in InGaN/GaN quantum-well-heterostructure flip-chip light-emitting diodes. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2003, 82, 2221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsukura, Y.; Inazu, T.; Pernot, C.; Shibata, N.; Kushimoto, M.; Deki, M.; Honda, Y.; Amano, H. Improving light output power of AlGaN-based deep-ultraviolet light-emitting diodes by optimizing the optical thickness of p-layers. Appl. Phys. Exp. 2021, 14, 084004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Sample | p-AlGaN | p+-AlGaN | n+-AlGaN | ||

| Al composition | [Si] (cm−3) | [C] (cm−3) | |||

| PN | #1 | 50% | 50% | ||

| #2 | 50% | 50% | |||

| TJ | #1 | 50% | 50% | 6.3×1019 | 1.8×1018 |

| #2 | 50% | 50% | 1.3×1020* | 1.8×1018* | |

| #3 | 50% | 50% | 6.3×1019 | 3.1×1017 | |

| #4 | 50% | 50% | 1.3×1020 | 3.1×1017 | |

| #5 | 60% | 60% | 1.3×1020* | 3.1×1017* | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).