Submitted:

22 February 2023

Posted:

23 February 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

Methods

Results and Discussion

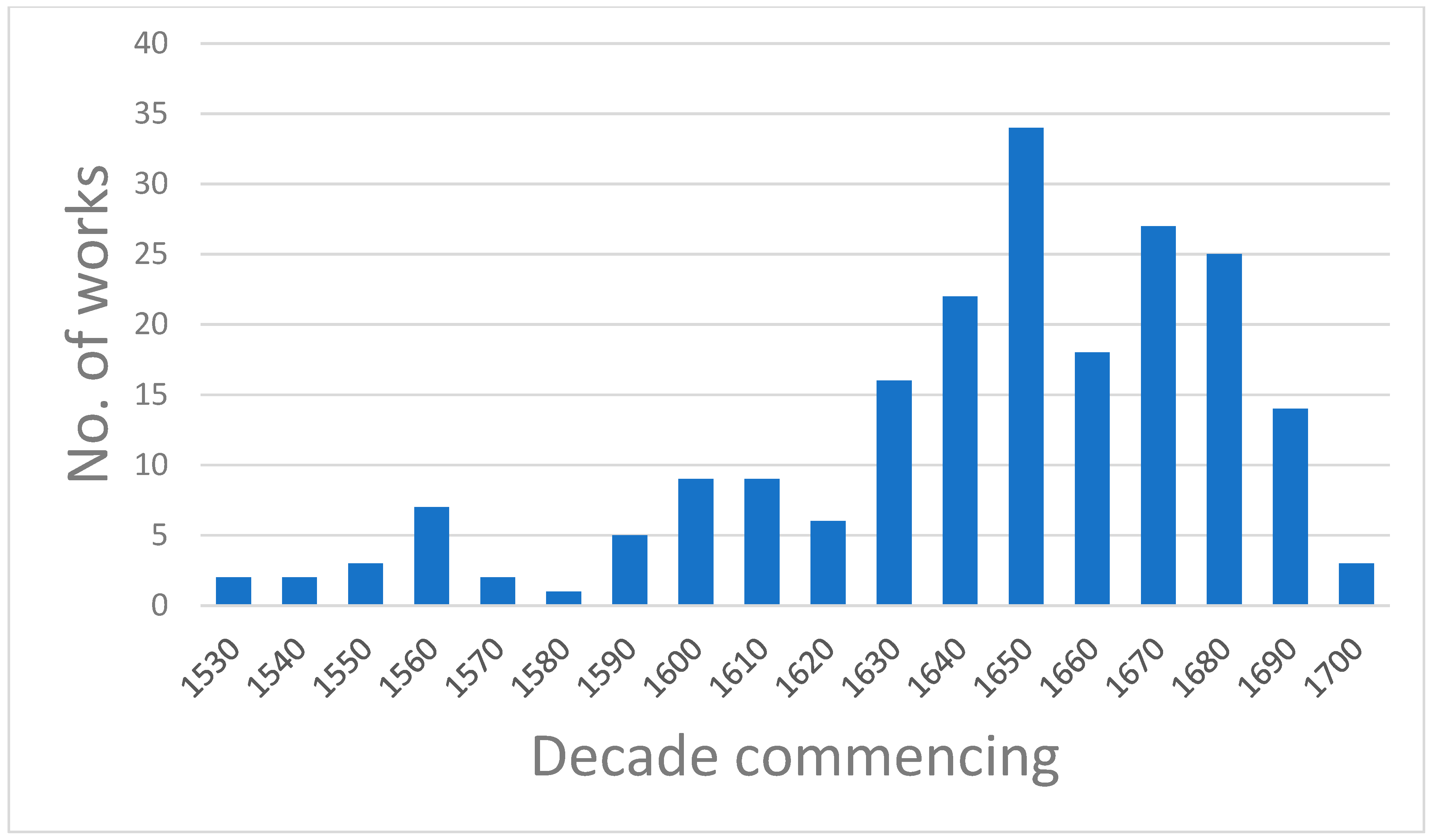

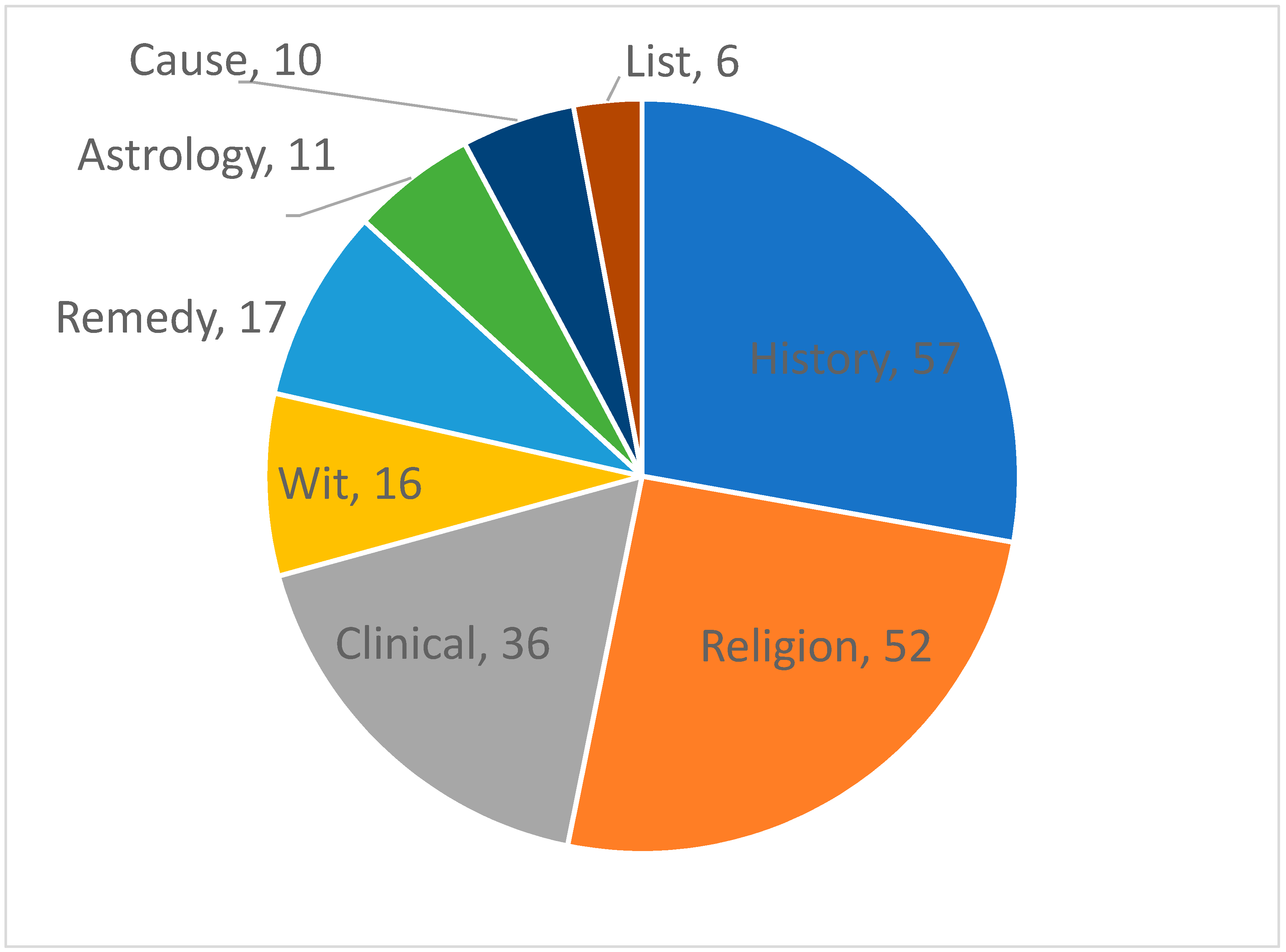

Distribution of references to the Sweat in EEBO

Examples of each category of discourse.

History

And upon the xi. day of October next following, then being the sweating sickness of new begun, dyed the said Thomas Hylle then of London mayor. And for him was chosen as mayre sir william Stokker knight & Draper, which dyed also of the said sickness shortly after.

Cause

Who knows not, that the english sweat, no old sycknes, and twenty other diseases more, come every day of inordinate fedynge?

Clinical

In this year a new sickness did reign, and is so sore and painful, as never was suffered before, the which was called the burning sweat. And this was so intolerable, that men could not keep their beds, but as lunatike persons & out of their wits ran about naked, so that none almost escaped ye were infected therewith.

Remedy

Chapyter treats of a diet and of an order to be used in the Pestyferous time of the pestilence and sweating sycknes.

use temporat meats and drynge. and beware of wine, bear, & cider, use to eat stewed or baken wardens if they can be gotten if not eat stewed or baken peers with comfits, use no gross meats, but those the which be light of digestion.

Our Author commends it also against the Palsy, the Leprosy, Worms, whether in old or young, Ruptures the English Sweating-sickness Plague, and all manner of Poison, as a speedy help in time of need.

Wit

Sweating sickness so fear thou beyond the mark, That winter or summer thou never sweatst at work.

Religion

GOD have mercy of all Christen souls, it was then a merry world, and will never be so good again, until these Gospelling Preachers have a sweating sickness in Smithfield, and their Bible burn.

…..they be Gods instruments to punish the earth. Example we have of mortal pestilence, horrible fevers, and sweating sickness, and of late, a general fever, that this land is often greatly plaged withal. Sweet air to be made in the time of sickness Then one must make a fire in every chimney within the house, and burn sweet perfumes to purge this foul air.

Astrology

Here with us, we have not heard of late days of any such diseases, as the shaking of the sheets, or the sweating sickness ….. as for the cause thereof ….. let others search it out, for my own part I have observed, that this malady hath run through England thrice in the ages afore-going, & yet I doubt not but long before also it did the lik, although it were not recorded in writing. First in the year of our Lord 1485, in which King Henry the seventh first began his reign, a little after the great Conjunction of the superior Planets in Scorpio. A second time yet more mildly, although the Plague accompanied it in the 33d year after, Anno 1518, upon a great opposition of the same Planets in Scorpio & Taurus, at which time it plagued the Netherlands and high Almany als. Last of all 33 years after that again in the year 1551, when another Conjunction of those Planets in Scorpio took their effects: so that by Gods goodness for the space now of these last seventy three years we have not felt that disease. Twice thirty three years & more, and the same Conjunction and opposition of the Planets have passed over, & yet it hath not touched us.

Case Studies

Use of the Sweat as a confirmatory example in astrological prediction

Anno 1527. That great Plague, called the Sweating Sickness began to rage: a great and terrible Comet, of a bloody colour, appeared but a little before in the Heavens. They then laboured also under the weighty effects of a Conjunction of Saturn, Jupiter, and Mars in Risces, a watery sign, perhaps a main reason why that Pestilence was attended with a Sweat.

Four Comets appeared this year, when soon after the Turk besieged Viennal, and became Master of many Cities in Hungary: also the Sweating-sickness odestroy’d many thousands in England.

In the year 1522 Another Comet of a Saturnine colour (as before) broke forth, which ushered in a most dreadful Plague, and that Sweating Sickness which was most peculiar to English Bodies, dogging them (as it were) into all Lands.

Mr. Cambden observes, that Saturn can not (or seldom doth pass through the Fiery Triplicity, but he doth afflict London with a Plague, or some other Epidemical Disease, of which I will give a few Examples : Anno Domini 1348 Saturn was in Aries, an Universal Plague in London: 1485 Saturn in Sagittarius a Sweating Sickness in London: 1507 Saturn in Leo, another Sweating Sickness in London: 1517 Saturn in Sagittarius, the third Sweating Sickness in London: 1530 Saturn in Aries , the fourth Sweating Sickness in London.

Use of the Sweat as a metaphor for “soul slumber”

Sleep not on it, this is no slumbering business, It is like the sweating sickness; I must keep Your eyes still wake, y’re gone if once you sleep

Those who start to faint must be laid on their right side, called by their name and beaten with rosemary branches. A good drink of Guaiacum can be given and the patient must not be allowed to sleep.

It is a report, and a true one of the sweating sickness, that they that were kept avvake by those that were with them escaped, but the sickness was deadly if they were suffered to sleep.

Like those in the time of the sweating sickness that were smitten with Rosemary branches to keep them waking, and from sleeping to death; though they cried out at the smart of the blows against those that smote them, O you kill me, you kill me; whereas alas they had been killed with their disease, if they had not been smitten.

Keep company with waking Christians; such as neither dare sleep in sin themselves, nor suffer any to sleep who are near them. In the sweating sickness (they say) that they who were kept awake by those who were with them, escaped; but their sickness was deadly if they were suffered to sleep. The keeping one another awake is the best fruit of the communion of Saints.

The miraculous cure of Thomas More’s daughter

God showed, as it seemed, a miraculous and manifest token of his love, and favour towards him, at such time, as his daughter Roper lay dangerously sick of the sweating sickness (as many others did that year) and continued in such extremity of that disease, that by no skill of Physic, or other art in such case commonly used, (although she had divers both expert and learned Physicians continually attendant about her) she could be kept from sleeping, so that the Physicians themselves utterly despaired of her recovery, and quite gave her over. Her Father Sir Th, More, as one that m intierely loved and tendered he being in great grief and hea, and seeing all human helps to fale, determined t have recourse to God by prayer for remedy. Whereupon going up after his accustomed manner, into his aforesaid New Building, he there in his Chapel, upon his knees with tears, most devoutly besought Almighty God, that it would please his divine Goodness, unto whom nothing was impossible, if it were his blessed will, to vouchsafe graciously to hear his humble petiti ō. And suddenly it came into his mind, that a Glister might be the only way to help her; of which when he had told the Physicians, they all instantly agreed, that if there were any hope of remedy, that was the most likelist; and marveled much, that themselves had not before remembered the same. Then was it instantly ministered unto her sleeping, & after a while she awakened, and contrary to all their expectations immediately began to recover, & in short time was wholly restored unto her former health. Whom, if it had pleased God to have taken away, at that time, her Father said, that he would never after have meddled with worldly business.

The tragic death of the Brandon boys

The Afterlife of the Sweat

This study has sought to explore ways in which the memory of the English Sweat resonated powerfully for 150 years after its last appearance. Despite being only one relatively minor component of the infectious disease burden that continually challenged late mediaeval and early modern society, it obtained a special place in popular culture through its various other uses - as a confirmatory example in astrology, a metaphor in Puritan theology, a miracle story for Catholics and as a human interest story. EEBO ends as the 18th century begins, so it is not possible to pursue the story beyond that point using the comprehensiveness provided by EEBO. By the early 19th century, a genre of retrospective diagnosis of the Sweat had established itself, which continues to this day. Future work will require to join these two periods together.

Acknowledgements

References

- "Critical" (1808) The Inquirer, No. XV. What Was the Cause of the Sweating Sickness? Edinb Med Surg J, 4(16), 464-469.

- Alsted, J. H. (1643) Untitled. London: unlisted.

- Anon. (1652) Printed in the year, that many did fear, that Doomes-day it was nigh: but now we do see, what star-gazers be, for they have fore-told a ly. London: unspecified.

- Anon. (1681) The Petitioning-comet, or, A Brief chronology of all the famous comets and their events that have happen’d from the birth of Christ, to this very day : together with a modest enquiry into this present comet. London: Printed by Nat. Thompson.

- Bacon, F., Godwin, F. & Godwin, M. (1676) The history of the reigns of Henry the Seventh, Henry the Eighth, Edward the Sixth, and Queen Mary the first written by the Right Honourable Francis Lord Verulam, Viscount St. Alban ; the other three by the Right Honourable and Right Reverend Father in God, Francis Godwyn, Lord Bishop of Hereford. Alternative Title(s) Historie of the raigne of King Henry the Seventh. London: Printed by W.G. for R. Scot, T. Basset, J. Wright, R. Chiswell, and J. Edwy.

- Baker, R. (1643) A chronicle of the Kings of England, from the time of the Romans goverment unto the raigne of our soveraigne lord, King Charles containing all passages of state or church, with all other observations proper for a chronicle / faithfully collected out of authours ancient and moderne, & digested into a new method ; by Sr. R. Baker, Knight. London: Printed for Daniel Frere.

- Bate, G., Shipton, J. & Salmon, W. (1694) Pharmacopœia Bateana, or, Bate’s dispensatory translated from the second edition of the Latin copy, published by Mr. James Shipton : containing his choice and select recipe’s, their names, compositions, preparations, vertues, uses, and doses, as they are applicable to the whole practice of physick and chyrurgery : the Arcana Goddardiana, and their recipe’s intersperst in their proper places, which are almost all wanting in the Latin copy : compleated with above five hundred chymical processes, and their explications at large, various observations thereon, and a rationale upon each process : to which are added in this English edition, Goddard’s drops, Russel’s pouder [sic], and the Emplastrum febrifugum, those so much fam’d in the world : as also several other preparations from the Collectanea chymica, and other good authors / by William Salmon ... London: Printed for S. Smith and B. Walford.

- Bauderon, B. (1657) The expert phisician learnedly treating of all agues and feavers, whether simple or compound, shewing their different nature, causes, signes, and cure ... / written originally by that famous doctor in phisick, Bricius Bauderon ; and translated into English by B.W., licentiate in physick by the University of Oxford ... London: by R.I. for John Hancock.

- Boorde, A. (1547) A compendyous regyment or a dyetary of healthe made in Mountpyllyer, by Andrewe Boorde of physycke doctour, newly corrected and imprynted with dyuers addycyons dedycated to the armypotent Prynce and valyent Lorde Thomas Duke of Northfolke. London: In Fletestrete at the sygne of the George nexte to saynte Dunstones churche by Wyllyam Powel.

- Boyle, R. (1700) The works of the Honourable Robert Boyle, Esq., epitomiz’d by Richard Boulton ... ; illustrated with copper plates. London: J. Phillips and J. Taylor.

- Bridson, E. (2001) The English ’sweate’ (Sudor Anglicus) and Hantavirus pulmonary syndrome. British Journal of Biomedical Science, 58(1), 1-6.

- Bullein, W. (1564) A dialogue bothe pleasaunte and pietifull wherein is a goodly regimente against the feuer pestilence with a consolacion and comfort against death / newly corrected by Willyam Belleyn, the autour thereof. London: Ihon Kingsto.

- Bullein, W. (1595) The gouernment of health: a treatise written by William Bullein, for the especiall good and healthfull preseruation of mans bodie from all noysome diseases, proceeding by the excesse of euill diet, and other infirmities of nature: full of excellent medicines, and wise counsels, for conseruation of health, in men, women, and children. Both pleasant and profitable to the industrious reader. London: Printed by Valentine Sims dwelling in Adling street, at the signe of the white Swan, neare Bainards caste.

- Caius, J. (1552) A boke, or counseill against the disease commonly called the sweate, or sweatyng sicknesse. Made by Ihon Caius doctour in phisicke. Very necessary for euerye personne, and muche requisite to be had in the handes of al sortes, for their better instruction, preparacion and defence, against the soubdein comyng, and fearful assaultying of the-same disease. London: By Richard Grafton printer to the kynges maiestie.

- Carmichael, A. G. (2003) Sweating Sickness. In: Kiple, K. F. (ed.) The Cambridge Historical Dictionary of Disease. Cambridge, UK ; New York [N.Y.]: Cambridge University Press.

- Cogan, T. (1636) The haven of health. Chiefly gathered for the comfort of students, and consequently of all those that have a care of their health, amplified upon five words of Hippocrates, written Epid. 6. Labour, cibus, potio, somnus, Venus. Hereunto is added a preservation from the pestilence, with a short censure of the late sicknes at Oxford. By Thomas Coghan Master of Arts, and Batcheler of Physicke. London: Printed by Anne Griffin, for Roger Ball, and are to be sold at his, shop without Temple-barre, at the Golden Anchor next the Nags-head Tavern.

- Creighton, C. (1891) A history of epidemics in Britain from A.D. 664 to the extinction of plague. Cambridge: at the Universitry Press.

- Cressy, D. (1977) Levels of Illiteracy in England, 1530–1730. The Historical Journal, 20(1), 1-23. [CrossRef]

- Dugdale, W. (1676) The baronage of England, or, An historical account of the lives and most memorable actions of our English nobility in the Saxons time to the Norman conquest, and from thence, of those who had their rise before the end of King Henry the Third’s reign deduced from publick records, antient historians, and other authorities / by William Dugdale ... London: Printed by Tho. Newcomb, for Abel Roper, John Martin, and Henry Herringman.

- Dyer, A. (1997) The English sweating sickness of 1551: an epidemic anatomized. Med Hist, 41(3), 362-84. [CrossRef]

- Fabyan, R. (1533) Fabyans cronycle newly prynted, wyth the cronycle, actes, and dedes done in the tyme of the reygne of the moste excellent prynce kynge Henry the vii. father vnto our most drad souerayne lord kynge Henry the .viii. To whom be all honour, reuerece, and ioyfull contynaunce of his prosperous reygne, to the pleasure of god and weale of this his realme amen. London: Wyllyam Rastel.

- Fullwood, F. & Fuller, T. (1655) The church-history of Britain from the birth of Jesus Christ until the year M.DC.XLVIII endeavoured by Thomas Fuller. London: Printed for Iohn Williams.

- Gadbury, J. (1665) London’s deliverance predicted in a short discourse shewing the cause of plagues in general, and the probable time (God not contradicting the course of second causes) when the present pest may abate, &c. / by John Gadbury. London: Printed by J.C. for E. Calver.

- Gerster, A. G. (1916) What was the English sweating sickness or sudor anglicus of the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries? Bulletin of the Johns Hopkins Hospital, 27, 332-337.

- Goad, J. (1686) Astro-meteorologica, or, Aphorisms and discourses of the bodies cœlestial, their natures and influences discovered from the variety of the alterations of the air ... and other secrets of nature / collected from the observation at leisure times, of above thirty years, by J. Goad. London: Printed by J. Rawlins for Obadiah Blagrave.

- Godwin, F. (1628) Rerum Anglicarum Henrico VIII¨ Edvvardo VI. et Maria regnantibus, annales. London: Printed by Thomas Harper apud Ioannem Billium, typographum Regiu.

- Godwin, F. & Godwin, M. (1630) Annales of England. Containing the reignes of Henry the Eighth. Edward the Sixt. Queene Mary. Written in Latin by the Right Honorable and Right Reverend Father in God, Francis Lord Bishop of Hereford. Thus Englished, corrected and inlarged with the author’s consent, by Morgan Godwyn. London: Printed by A. Islip, and W. Stansb.

- Hakewill, G. (1627) An apologie of the povver and prouidence of God in the gouernment of the world. Or An examination and censure of the common errour touching natures perpetuall and vniuersall decay diuided into foure bookes: whereof the first treates of this pretended decay in generall, together with some preparatiues thereunto. The second of the pretended decay of the heauens and elements, together with that of the elementary bodies, man only excepted. The third of the pretended decay of mankinde in regard of age and duration, of strength and stature, of arts and wits. The fourth of this pretended decay in matter of manners, together with a large proofe of the future consummation of the world from the testimony of the gentiles, and the vses which we are to draw from the consideration thereof. By G.H. D.D. Oxford: Printed by Iohn Lichfield and William Turner, printers to the famous Vniversit.

- Hardie, A. (2012) CQPweb – combining power, flexibility and usability in a corpus analysis tool. International Journal of Corpus Linguistics, 17(3), 380-409.

- Hardyng, J. & Grafton, R. (1543) The chronicle of Ihon Hardyng in metre, fro[m] the first begynnyng of Engla[n]de, vnto ye reigne of Edwarde ye fourth where he made an end of his chronicle. And from yt time is added with a co[n]tinuacion of the storie in prose to this our tyme, now first emprinted, gathered out of diuerse and sondrie autours of moste certain knowelage [et] substanciall credit, yt either in latin orels in our mother toungue haue writen of ye affaires of Englande. London: In officina Richardi Grafton.

- Hayward, J. & Vaughan, R. (1630) The life, and raigne of King Edward the Sixt. Written by Sr. Iohn Hayward Kt. Dr. of Lawe. London: Printed by Eliot’s Court Press, and J. Lichfield at Oxford, for Iohn Partridge, and are to be sold at the signe of the Sunne in Paules Churchyard.

- Heylyn, P. (1661) Ecclesia restaurata, or, The history of the reformation of the Church of England containing the beginning, progress, and successes of it, the counsels by which it was conducted, the rules of piety and prudence upon which it was founded, the several steps by which it was promoted or retarded in the change of times, from the first preparations to it by King Henry the Eight untill the legal settling and establishment of it under Queen Elizabeth : together with the intermixture of such civil actions and affairs of state, as either were co-incident with it or related to it / by Peter Heylyn. London: Printed for H. Twyford, T. Dring, J. Place, W. Palmer,.

- Heyman, P., Cochez, C. & Hukic, M. (2018) The English Sweating Sickness: Out of Sight, Out of Mind? Acta Med Acad, 47(1), 102-116. 10.5644/ama2006-124.221.

- Heyman, P., Simons, L. & Cochez, C. (2014) Were the English sweating sickness and the Picardy sweat caused by hantaviruses? Viruses, 6(1), 151-71. 10.3390/v6010151.

- Heywood, J. (1560) A fourth hundred of epygrams, newly inuented and made by Iohn Heywood. London: In fleetstrete in the house late Thomas Berthelettes.

- Hoddesdon, J. (1662) The history of the life and death of Sr. Thomas More, Lord High Chancellor of England in King Henry the Eights time collected by J.H., Gent. London: Printed for George Eversden, and Henry Eversden.

- Holwell, J. (1682) Catastrophe mundi, or, Europe’s many mutations until the year 1701 being an astrological treatise of the effects of the triple conjunction of Saturn and Jupiter 1682 and 1683, and of the comets 1680 and 1682, and other configurations concomitant : wherein the fate of Europe for these next 20 years is ... more than probably conjectured ... : also, an ephimeris of all the comets that have appeared from ... 1603 to the year 1682 ... : whereunto is annexed the hieroglyphicks of Nostrodamus ... / by John Holwell. London: Printed for the author and are to be sold by most bookseller.

- Howell, W. (1679) Medulla historiæ Anglicanæ being a comprehensive history of the lives and reigns of the monarchs of England from the time of the invasion thereof by Jvlivs Cæsar to this present year 1679 : with an abstract of the lives of the Roman emperors commanding in Britain, and the habits of the ancient Britains : to which is added a list of the names of the Honourable the House of Commons now sitting, and His Majesties Most Honourable Privy Council, &c. London: Printed for Abel Swalle, and are to be sold by him.

- Jenkyn, W. (1654) Untitled. London: Printed by Tho. Maxey, for Samuel Gellibrand, at the golden Ball in Paul’s Church-yar.

- Lloyd, D. (1670) State-worthies, or, The states-men and favourites of England since the reformation their prudence and policies, successes and miscarriages, advancements and falls, during the reigns of King Henry VIII, King Edward VI, Queen Mary, Queen Elizabeth, King James, King Charles I. London: Printed by Thomas Milbourne for Samuel Speed.

- Mcsweegan, E. (2004) Anthrax and the etiology of the English sweating sickness. Med Hypotheses, 62(1), 155-7. [CrossRef]

- Middleton, T. (1657) No wit, [no] help like a womans a comedy / by Tho. Middleton, Gent. London: Printed for Humphrey Moseley.

- Miege, G. (1694) Miscellanea, or, A choice collection of wise and ingenious sayings, &c of princes, philosophers, statesmen, courtiers, and others out of several antient and modern authors, for the pleasurable entertainment of the nobility and gentry of both sexes / by G.M. London: Printed for William Lindsey.

- Miege, G. (1697) Delight and pastime, or, Pleasant diversion for both sexes consisting of good history and morality, witty jests, smart repartees, and pleasant fancies, free from obscene and prophane expressions, too frequent in other works of this kind, whereby the age is corrupted in a great measure, and youth inflamed to loose and wanton thoughts : this collection may serve to frame their minds to such flashes of wit as may be agreeable to civil and genteel conversation / by G.M. London: Printed for J. Sprint ... and G. Conyers.

- More, C. & More, T. (1631) D.O.M.S. The life and death of Sir Thomas Moore Lord high Chancellour of England. Written by M. T.M. and dedicated to the Queens most gracious Maiestie. Douai: Printed by B. Bellièr.

- Morison, R. (1536) A remedy for sedition vvherin are conteyned many thynges, concernyng the true and loyall obeysance, that comme[n]s owe vnto their prince and soueraygne lorde the Kynge. London: In aedibus Thomae Bertheleti regii impressori.

- Mynsicht, A. V. & Partridge, J. (1682) Thesaurus & armamentarium medico-chymicum, or, A treasury of physick with the most secret way of preparing remedies against all diseases : obtained by labour, confirmed by practice, and published out of good will to mankind : being a work of great use for the publick / written originally in Latine by ... Hadrianus áa Mynsicht ...; and faithfully rendred into English by John Partridge ... London: Printed by J.M. for Awnsham Churchill.

- Ness, C. (1681) A philosophical and divine discourse blazoning upon this blazing star divided into three parts; the I. Treating on the product, form, colour, motion, scituation, and signification of comets. II. Contains the prognosticks of comets in general, and of this in particular; together with a chronology of all the comets for the last 400 years. III. Consists of (1.) the explication of the grand concerns of this comet by astrological precepts and presidents. (2.) The application of its probable prognosticks astrologically and theologically. By Christopher Nesse, minister of the gospel, in London, 1681. London: printed for J. Wilkins, and J. Sampson [and L. Curtiss on Ludgate-hill.

- Pell, D. (1659) Untitled. London: printed for Livewell Chapman, and are to be sold at the Crown in Popes-head Alle.

- Porter, T. (1659) A list of books which "Are to be sold by Robert Walton, at the Globe and Compass, in s. Paul’s Churchyard, on the North-sid". London.

- Préchac, J. D. (1678) The English princess, or, The duchess-queen a relation of English and French adventures : a novel : in two parts. London: Printed for Will. Cademan and Simon Neale.

- Préchac, J. D. (1686) The illustrious lovers, or, Princely adventures in the courts of England and France containing sundry transactions relating to love intrigues, noble enterprises, and gallantry : being an historical account of the famous loves of Mary sometimes Queen of France, daughter to Henry the 7th, and Charles Brandon the renown’d Duke of Suffolk : discovering the glory and grandeur of both nations / written original in French, and now done into English. London: Printed for William Whitwood.

- Proquest (1998) Early English Books Online. In: Company., P. I. a. L. (ed.) 3 ed. Ann Arbor, Mich.

- R. B., P. O. N. C. (1681) The surprizing miracles of nature and art in two parts : containing I. The miracles of nature, or the strange signs and prodigious aspects and appearances in the heavens, the earth, and the waters for many hundred years past ... II. The miracles of art, describing the most magnificent buildings and other curious inventions in all ages ... : beautified with divers sculptures of many curiosities therein / by R.B., author of the Hist. of the wars of England, Remarks of London, Wonderful prodigies, Admirable curiosities in England, and Extraordinary adventures of several famous men. London: Printed for Nath. Crouch.

- Roberts, R. S. (1965) A consideration of the nature of the English sweating sickness. Med Hist, 9(4), 385-9. [CrossRef]

- Roper, W. (1626) The mirrour of vertue in worldly greatnes. Or The life of Syr Thomas More Knight, sometime Lo. Chancellour of England. Paris i.e. Saint-Omer: Printed at the English College Press.

- Seller, J. (1696) The history of England giving a true and impartial account of the most considerable transactions in church and state, in peace and war, during the reigns of all the kings and queens, from the coming of Julius Cæsar into Britain : with an account of all plots, conspiracies, insurrections, and rebellions ... : likewise, a relation of the wonderful prodigies ... to the year 1696 ... : together with a particular description of the rarities in the several counties of England and Wales, with exact maps of each county / by John Seller ... London: Printed by Job and John How, for John Gwillim.

- Sennert, D. (1658) Nine books of physick and chirurgery written by that great and learned physitian, Dr Sennertus. The first five being his Institutions of the whole body of physick: the other four of fevers and agues: with their differences, signs, and cures. London: printed by J.M. for Lodowick Lloyd, at the Castle in Corn-hil.

- Sennert, D., Culpeper, N. & Cole, A. (1660) Two treatises. The first, of the venereal pocks: Wherein is shewed, I. The name and original of this disease. II. Histories thereof. III. The nature thereof. IV. Its causes. V. Its differences. VI. Several sorts of signs thereof. VII. Several waies of the cure thereof. VIII. How to cure such diseases, as are wont to accompany the whores pocks. The second treatise of the gout, 1. Of the nature of the gout. 2. Of the causes thereof. 3. Of the signs thereof. 4. Of the cure thereof. 5. Of the hip gout or sciatica. 6. The way to prevent the gout written in Latin and English. By Daniel Sennert, Doctor of Physick. Nicholas Culpeper, physitian and astrologer. Abdiah Cole, Doctor of Physick, and the liberal arts. London: printed by Peter Cole, printer and book-seller, at the sign of the Printing-press in Cornhil, neer the Royal Exchang.

- Shaw, M. B. (1933) A Short History of the Sweating Sickness. Ann Med Hist, 5(3), 246-274.

- Sibbes, R., Goodwin, T. & Nye, P. (1639) Bovvels opened, or, A discovery of the neere and deere love, union and communion betwixt Christ and the Church, and consequently betwixt Him and every beleeving soule. Delivered in divers sermons on the fourth fifth and sixt chapters of the Canticles. By that reverend and faithfull minister of the Word, Doctor Sibs, late preacher unto the honourable societie of Grayes Inne, and Master of Katharine Hall in Cambridge. Being in part finished by his owne pen in his life time, and the rest of them perused and corrected by those whom he intrusted with the publishing of his works. . London: Printed by GM for George Edwards in the Old Baily in Greene-Arbour at the signe of the Angel.

- Spelman, H. (1698) The history and fate of sacrilege discover’d by examples of scripture, of heathens, and of Christians; from the beginning of the world continually to this day / by Sir Henry Spelman ... London: Printed for John Hartley.

- Spelman, H. & Spelman, C. (1646) Untitled. Oxford: Printed by Henry Hall printer to the Universiti.

- Spencer, J. (1658) Kaina kai palaia Things new and old, or, A store-house of similies, sentences, allegories, apophthegms, adagies, apologues, divine, morall, politicall, &c. : with their severall applications / collected and observed from the writings and sayings of the learned in all ages to this present by John Spencer ... London: Printed by W. Wilson and J. Streater, for John Spencer.

- Stonham, B. (1676) The parable of the ten virgin’s opened, or, Christ’s coming as a bridegroom cleared up and improved from Matthew XXV, ver. 1,2,3 &c. / by Benjamin Stonham. London: No publisher given.

- Stow, J. & Howes, E. (1618) The abridgement of the English Chronicle, first collected by M. Iohn Stow, and after him augmented with very many memorable antiquities, and continued with matters forreine and domesticall, vnto the beginning of the yeare, 1618. by E.H. Gentleman. There is a briefe table at the end of the booke. London: By Edward Allde and Nicholas Okes for the Company of Stationer.

- Stubbe, H., Tartaglia, N., Sardi, P. & Henshaw, T. (1670) Legends no histories, or, A specimen of some animadversions upon The history of the Royal Society wherein, besides the several errors against common literature, sundry mistakes about the making of salt-petre and gun-powder are detected and rectified : whereunto are added two discourses, one of Pietro Sardi and another of Nicolas Tartaglia relating to that subject, translated out of Italian : with a brief account of those passages of the authors life ... : together with the Plus ultra of Mr. Joseph Glanvill reduced to a non-plus, &c. / by Henry Stubbe ... London.

- Swan, J. & Marshall, W. (1635) Speculum mundi¨ Or A glasse representing the face of the world shewing both that it did begin, and must also end: the manner how, and time when, being largely examined. Whereunto is joyned an hexameron, or a serious discourse of the causes, continuance, and qualities of things in nature; occasioned as matter pertinent to the work done in the six dayes of the worlds creation. Cambridge: Printed by Thomas Buck and Roger Daniel, the printers to the Vniversitie of Cambridg.

- Swinnock, G. (1665) The works of George Swinnock, M.A. containing these several treatises ... . London: Printed by J.B. for Tho. Parkhurst.

- Symons, H. (1658) Timåe kai timåoria, A beautifull swan with two black feet, or, Magistrates deity attended with mortality & misery affirmed & confirmed before the learned and religious Judge Hales, at the assize holden at Maidstone, July 7, 1657, for the county of Kent / by Henry Symons ... London: Printed by J. Hayes and are to be sold by H. Crips.

- Trapp, J. (1646) Untitled. London: Printed by G.M. for Iohn Bellamy, and are to be sold at his shop, at the signe of the three Golden-Lyons in Cornehill, near the Royall Exchang.

- Trapp, J. (1649) Untitled. London: Printed for Timothy Garthwait, at the George in Little-Brittai.

- Trapp, J. (1657) A commentary or exposition upon the books of Ezra, Nehemiah, Esther, Job and Psalms wherein the text is explained, some controversies are discussed ... : in all which divers other texts of scripture, which occasionally occurre, are fully opened ... / by John Trapp ... London: Printed by T.R. and E.M. for Thomas Newberry ... and Joseph Barber.

- Trapp, J. (1660) A commentary or exposition upon these following books of holy Scripture Proverbs of Solomon, Ecclesiastes, the Song of Songs, Isaiah, Jeremiah, Lamentations, Ezekiel & Daniel : being a third volume of annotations upon the whole Bible / by John Trapp ... London: Printed by Robert White, for Nevil Simmons.

- Trapp, J. & Trapp, J. (1647a) Brief commentary or exposition upon the Gospel according to St John. London: Printed by A.M. for John Bellamie, at the sign of the three golden-Lions near the Royall-Exchang.

- Trapp, J. & Trapp, J. (1647b) A commentary or exposition upon all the Epistles, and the Revelation of John the Divine wherein the text is explained, some controversies are discussed, divers common-places are handled, and many remarkable matters hinted, that had by former interpreters been pretermitted : besides, divers other texts of Scripture, which occasionally occur, are fully opened, and the whole so intermixed with pertinent histories, as will yeeld both pleasure and profit to the judicious reader : with a decad of common-places upon these ten heads : abstinence, admonition, alms, ambition, angels, anger, apostasie, arrogancie, arts, atheisme / by John Trapp ... London: Printed by A.M. for John Bellamie, at the sign of the three golden-Lions near the Royall-Exchang.

- Wall, J. (1648) Untitled. London: Printed for Ralph Smith, at the signe of the Bible in Cornhill neer the Royall Exchang.

- Watson, T. (1692) A body of practical divinity consisting of above one hundred seventy six sermons on the lesser catechism composed by the reverend assembly of divines at Westminster : with a supplement of some sermons on several texts of Scripture / by Thomas Watson ... London: Printed for Thomas Parkurst.

- Webster, C. (1979) Health, Medicine, and Mortality in the Sixteenth Century. Cambridge [Eng.] ; New York: Cambridge University Press.

- Willis, T. & Pordage, S. (1684) Dr. Willis’s practice of physick being the whole works of that renowned and famous physician wherein most of the diseases belonging to the body of man are treated of, with excellent methods and receipts for the cure of the same : fitted to the meanest capacity by an index for the explaining of all the hard and unusual words and terms of art derived from the Greek, Latine, or other languages for the benefit of the English reader : with forty copper plates. London: Printed for T. Dring, C. Harper, and J. Leig.

- Wirsung, C. & Mosan, J. (1605) The general practise of physicke conteyning all inward and outward parts of the body, with all the accidents and infirmities that are incident vnto them, euen from the crowne of the head to the sole of the foote: also by what meanes (with the help of God) they may be remedied: very meete and profitable, not only for all phisitions, chirurgions, apothecaries, and midwiues, but for all other estates whatsoeuer; the like whereof as yet in english hath not beene published. Compiled and written by the most famous and learned doctour Christopher VVirtzung, in the Germane tongue, and now translated into English, in diuers places corrected, and with many additions illustrated and augmented, by Iacob Mosan Germane, Doctor in the same facultie. London: Printed by Richard Field Impensis Georg. Bisho.

- Wood, A. Á. (1692) Athenæ Oxonienses an exact history of all the writers and bishops who have had their education in the most ancient and famous University of Oxford, from the fifteenth year of King Henry the Seventh, Dom. 1500, to the end of the year 1690 representing the birth, fortune, preferment, and death of all those authors and prelates, the great accidents of their lives, and the fate and character of their writings : to which are added, the Fasti, or, Annals, of the said university, for the same time ... London: Printed for Tho. Bennet.

- Wylie, J. a. H. & Collier, L. H. (1981) The English Sweating Sickness (Sudor-Anglicus) - a Reappraisal. Journal of the History of Medicine and Allied Sciences, 36(4), 425-445.

- Younge, R. (1641) Untitled. London: Printed by J.B. and S.B., and are to be sold by Philip Nevill.

- Younge, R. (1660) A Christian library, or, A pleasant and plentiful paradise of practical divinity in 37 treatises of sundry and select subjects ... / by R. Younge ... London: Printed by M.I. and are to be sold onely by James Crumps.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).