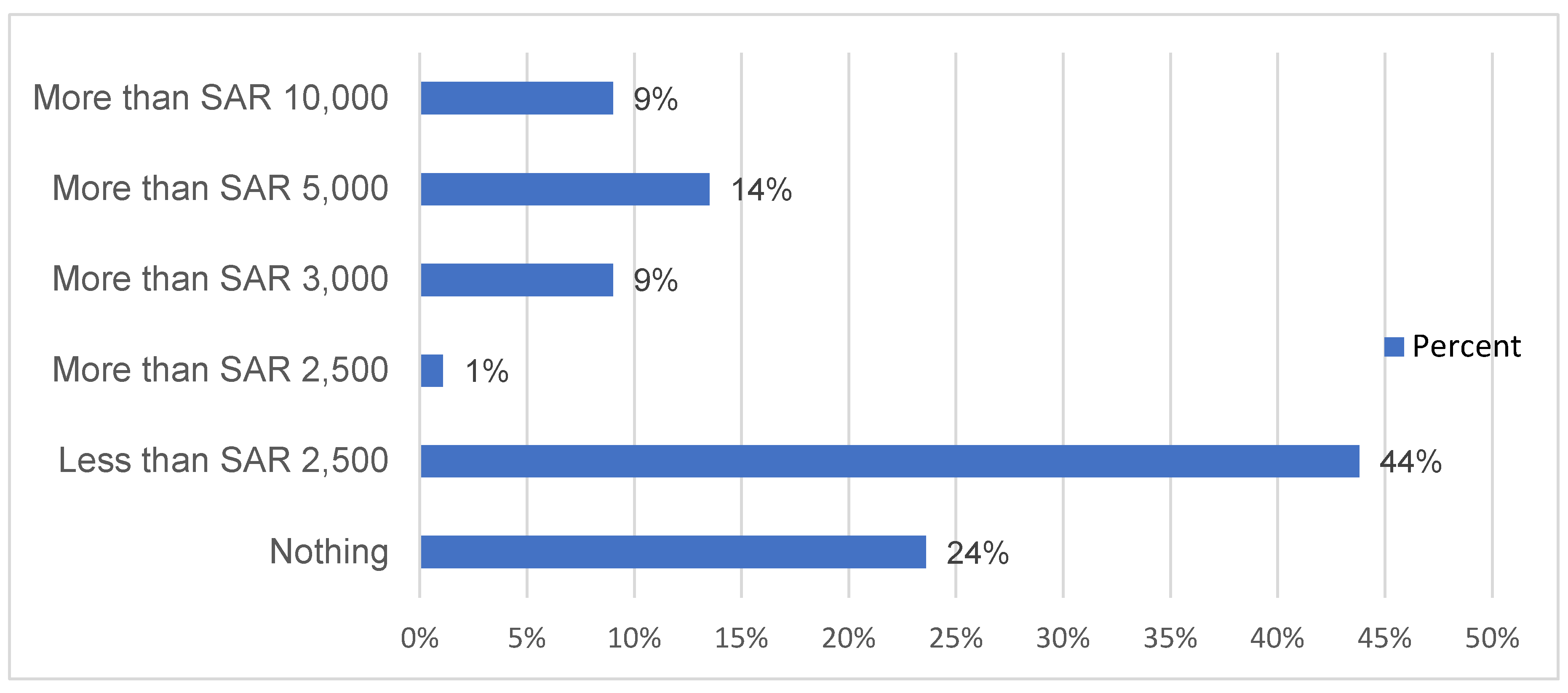

The income profile of the respondents shows that the sample mainly comprised a low-income population. Saudi Arabia’s GDP per capita is estimated at USD 20,110 in 2022 [

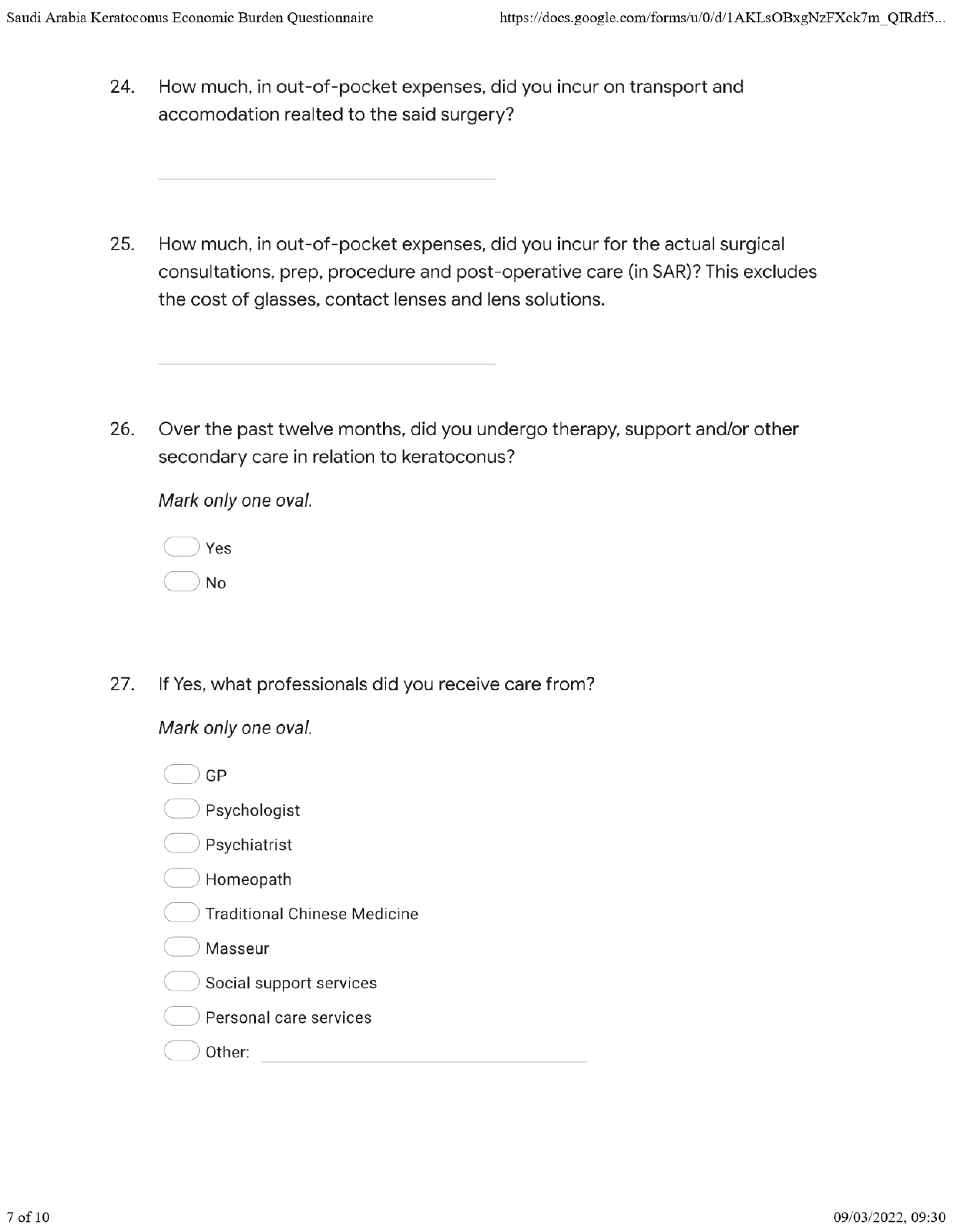

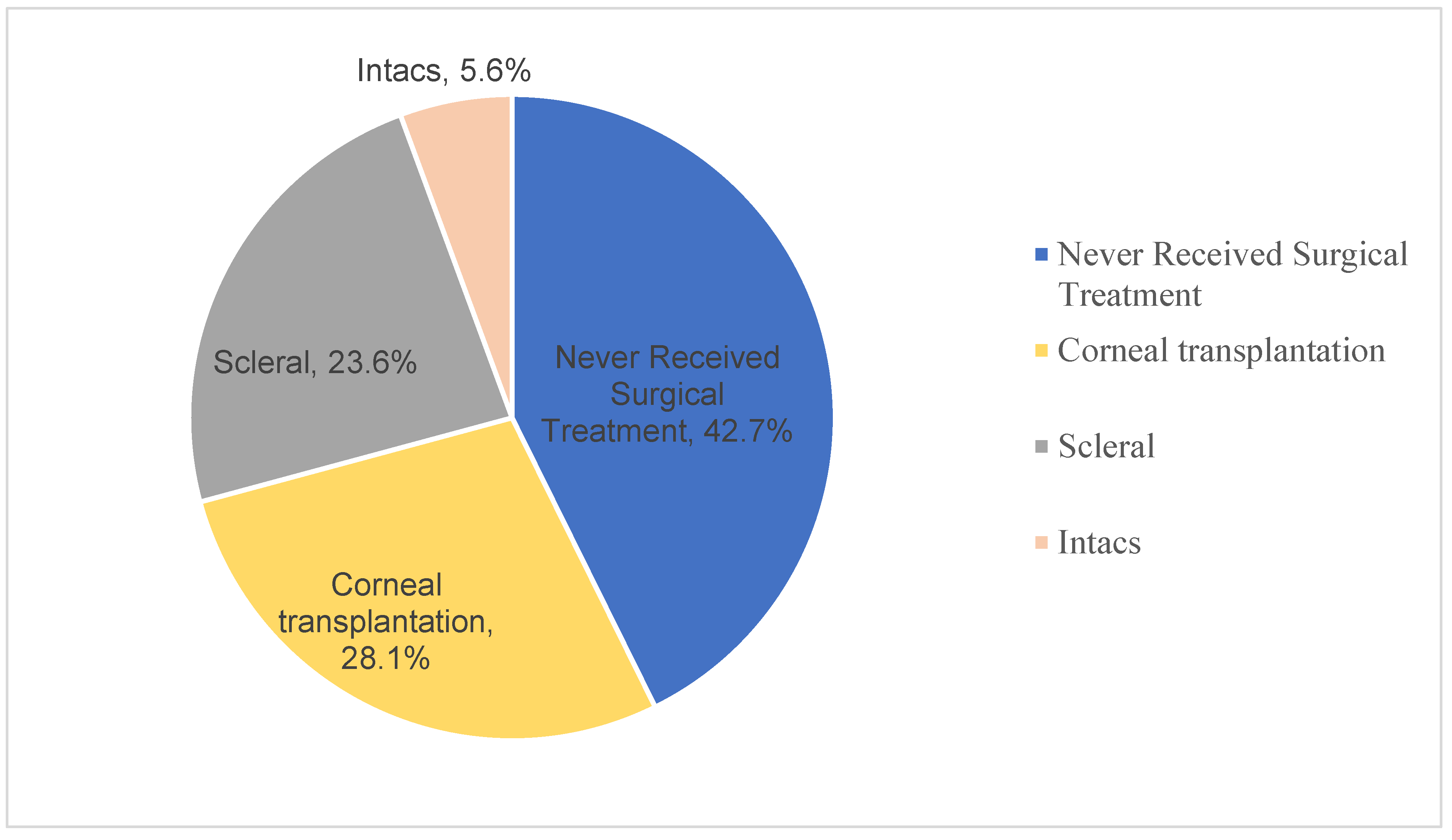

8], implying that only 36% of the sample that had more than SAR 50,000 fall in the average income category, while those with less or without income are either in the lower income brackets or were dependents. An estimated 42% of the respondents reported never having received surgical treatment for keratoconus, which given the fact that

corneal cross-linking is arguably the most effective treatment for keratoconus [

9,

10,

11], points to potentially poor access to the best care. This finding is consistent with past empirical evidence that cases of keratoconus in Saudi Arabia (and other countries in the region) are relatively more prevalent and advanced at the time of diagnosis than in other parts of the world[

12].

While studies elsewhere in the world found broad variations in prevalence, they also thought that those were related to factors that include ethnicity, geography, diagnostic criteria, and methodological differences[

13,

14]. In respect to geographic factors, however, environmental factors such as ultraviolent light exposure and altitude may account for variations [

13,

15,

16]. Generally, research shows high keratoconus prevalence in Saudi Arabia, Israel, and India compared to regions in North America, Europe, and parts of Asia [

6,

12]. Against an estimated global prevalence of 1 in every 2000 people for example, Assiri’s study in Asiri province found that the prevalence of keratoconus have shown 20 per 100,000 population and high disease severity, with advanced stage keratoconus mean age of 17.7 (SD=3.6) years [

12].

Further, the treatments received by participants in this study have lower levels of effectiveness, particularly concerning stemming the progression of the disease. The extant empirical evidence shows that INTACS

® are ideally indicated for mild or moderate cases that are intolerant to contact lenses and have clear optical zones [

14,

17,

18,

19] They may be an alternative to rehabilitative lamellar or penetrating keratoplasty, as well as for uncorrected acuity[

14,

20,

21]. Keratoconus is the main indication for scleral contact lenses for enhanced comfort, lens centration, and intolerance to corneal gas-permeable lenses[

20] Empirical evidence shows it can prevent corneal transplantation in up to 80% of severe keratoconus cases, even with lamellar keratoplasty [

14,

20]. Keratoplasty is indicated in cases with corneal scarring and lamellar or full thickness [

21].

While the cost, access, and availability of corneal donors remains an impediment to transplantation[

22], the finding that up to 28% of the respondents had undergone corneal transplantations encouraging but may be accounted for by sampling issues. Given the range of alternatives, differing effectiveness and indications, more research is needed to ascertain the effectiveness, access, and adverse effects of INTACS

®, scleral lenses, and corneal transplants for treating keratoconus in Saudi Arabia against evidence-based indications, as a basis for enhanced efficiency and effectiveness in the management of the condition.

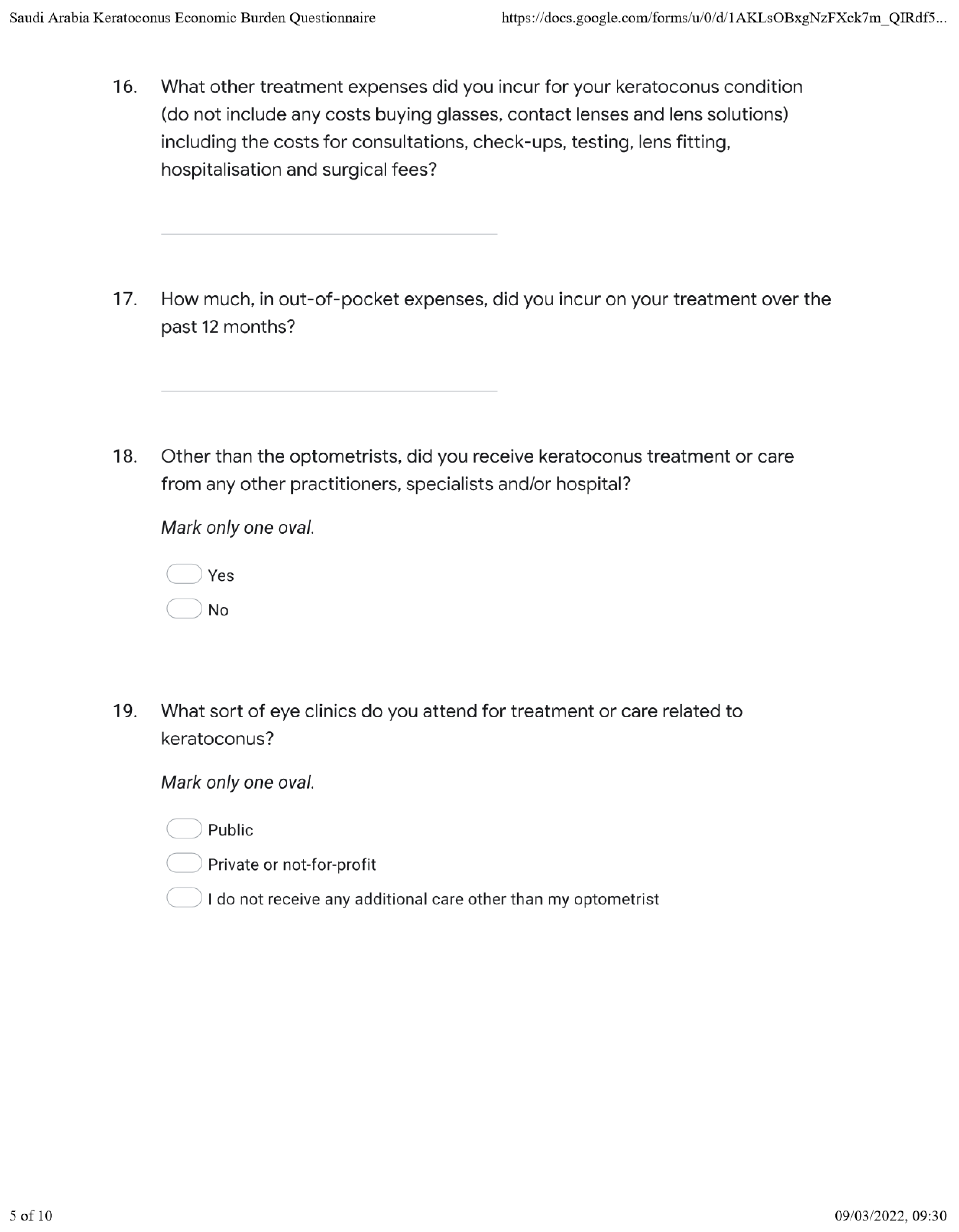

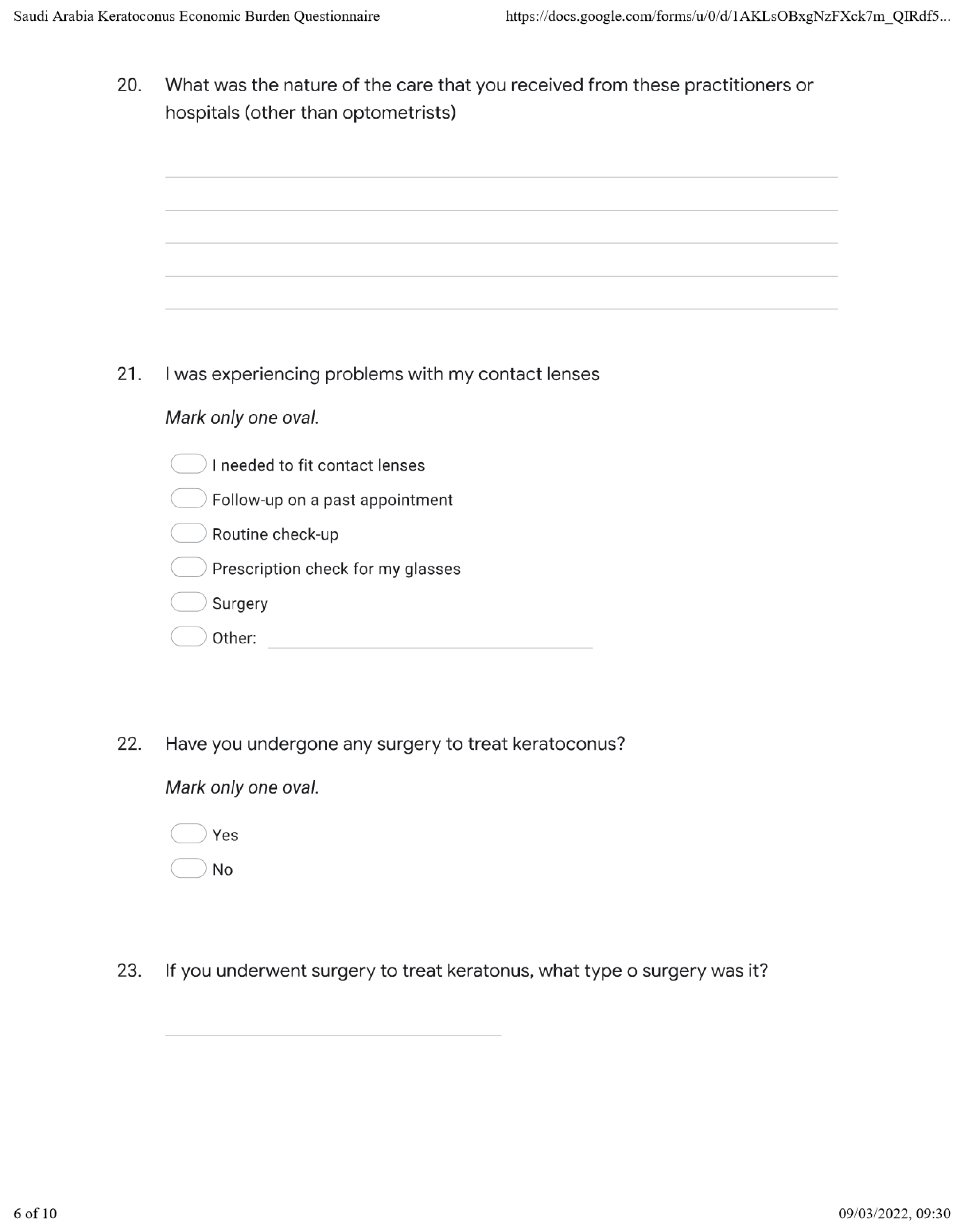

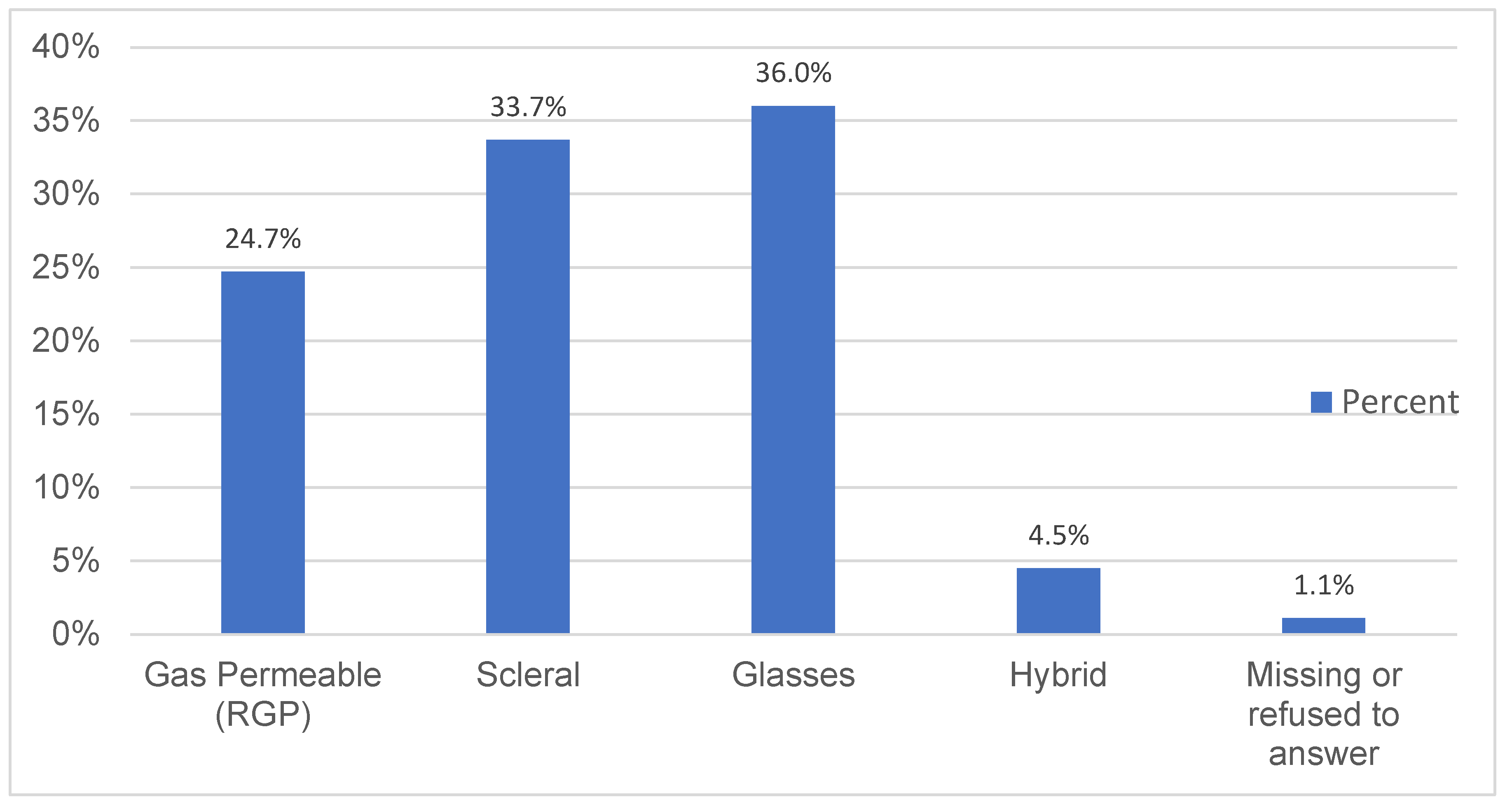

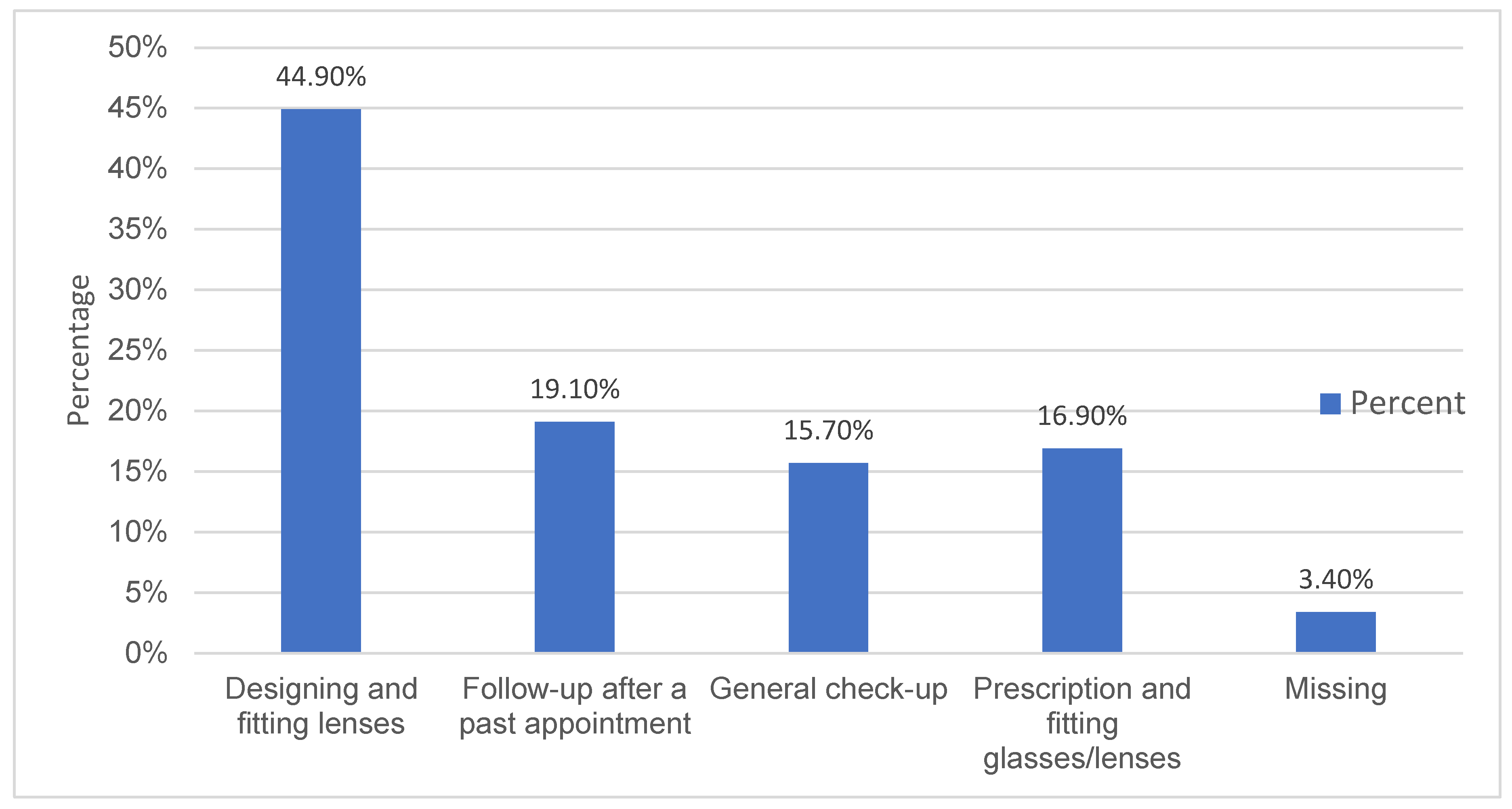

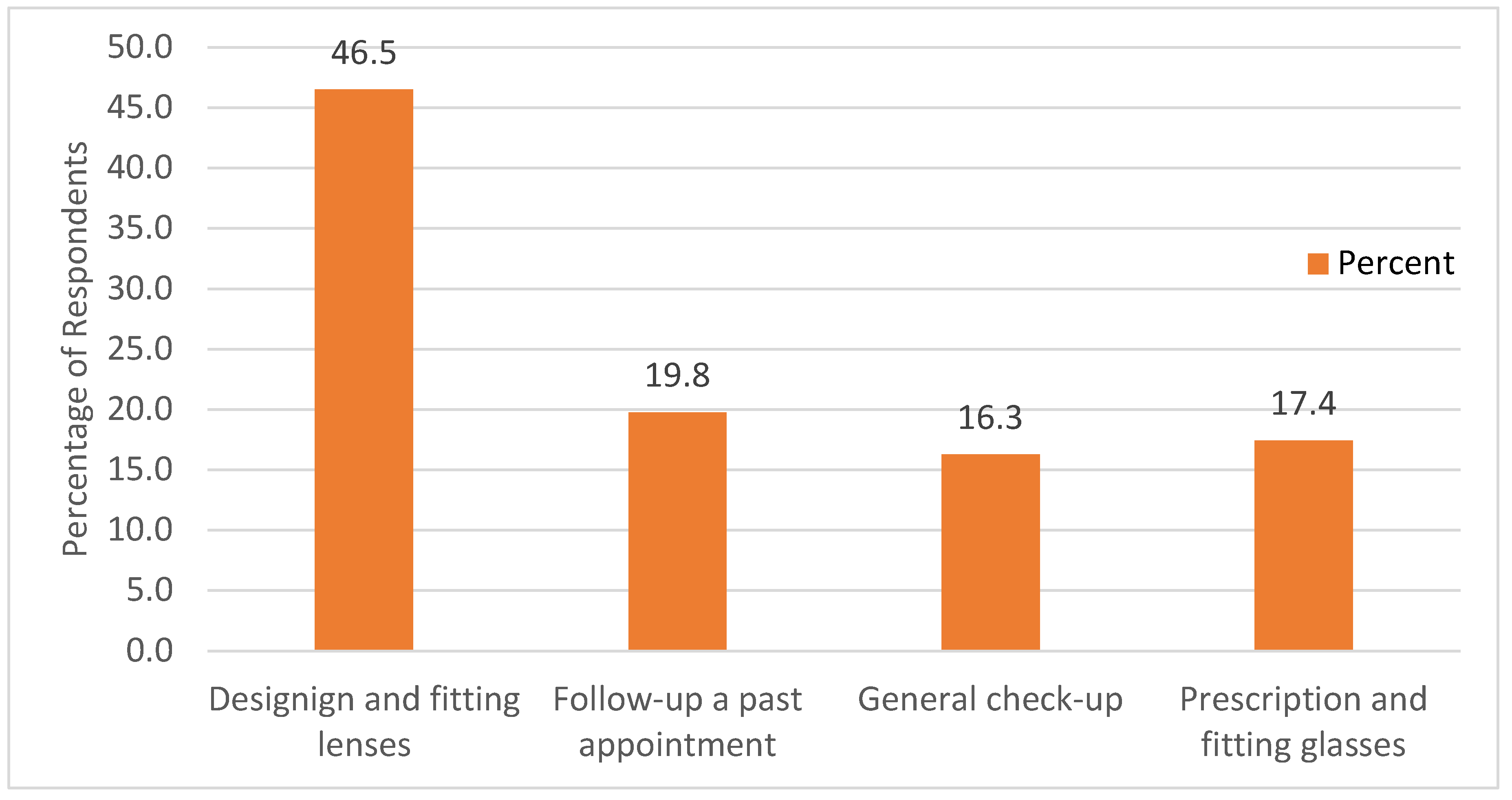

A higher-than-average proportion of the respondents in the present study attended optometric clinics, primarily for prescribing, designing, and fitting glasses or lenses, with about half as many seeking similar services from non-optometric practitioners/facilities. Surgery was not indicated as a reason for visits, even though 28% of the respondents had since undergone corneal transplantation. The proportion of those that had undergone surgery is lower than 48% in Chan et al., and it was unclear whether the surgery involved cross-linking procedures [

1].

Keratoconus disability and productivity losses

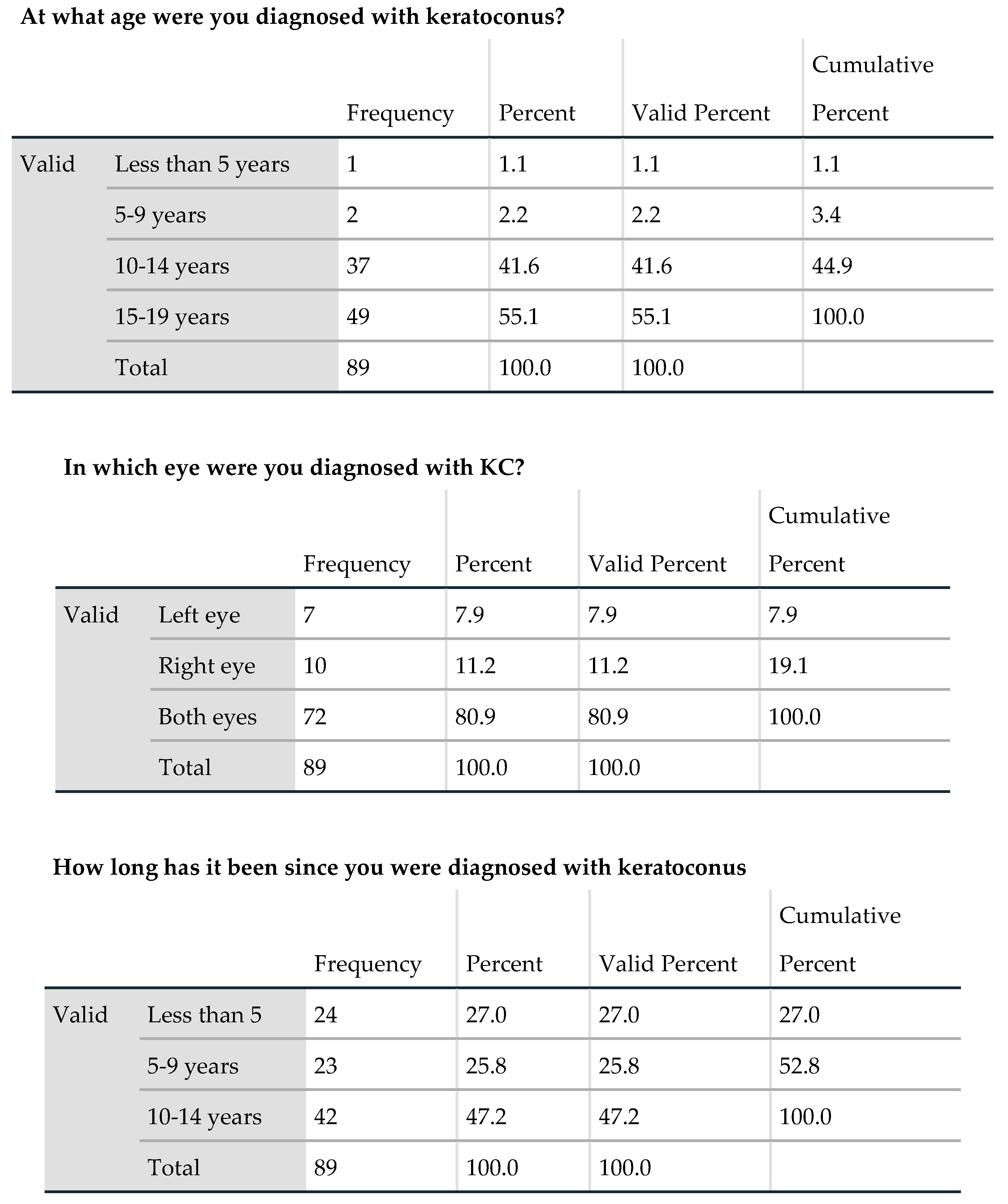

This study shows that keratoconus diagnosis occurs fairly early on in the lives of the patients, and thus the lifetime costs of the condition are likely to be cumulatively high. The age of diagnosis is consistent with small sample studies[

23,

24], but much lower than the estimated age-specific incidence of 1:7500 (13.3/100,000) established in large sample studies [

4]. Godefrooij et al. [

4], for example, determined that the average age of diagnosis is 28.3 years, but it is likely that the age of diagnosis as against the age of onset, depends on access to care[

25]. Other than the age of diagnosis and the fact that keratoconus is not considered a disability in Saudi Arabia (other than in rare cases where patients’ visual acuity is severely compromised), the results show severe symptoms of the condition and resulting occupational and social disability, as well as the financial consequences, are substantial. This may be exacerbated by the evidence of low awareness of keratoconus in the general population in Saudi Arabia, resulting in policy inaction, low health-seeking behaviour, and difficult social/work environments. Al-Dairi et al., for example, find that the prevalence of depression in a sample of keratoconus patients in Saudi Arabia was 40.6%

(n = 134; p<.001) and further that the use of corrective lenses in both eyes heightened the risk of depression even higher [

26].

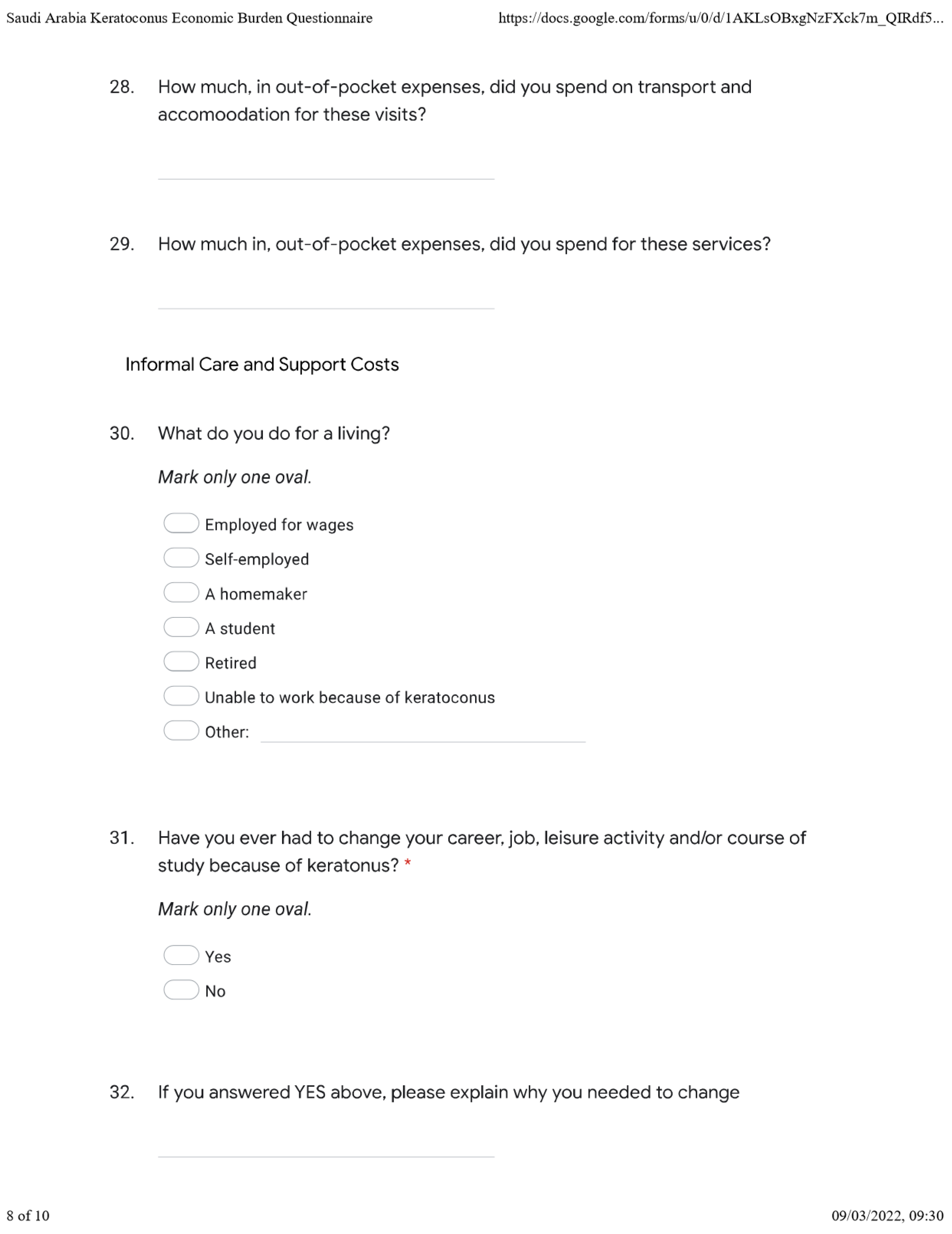

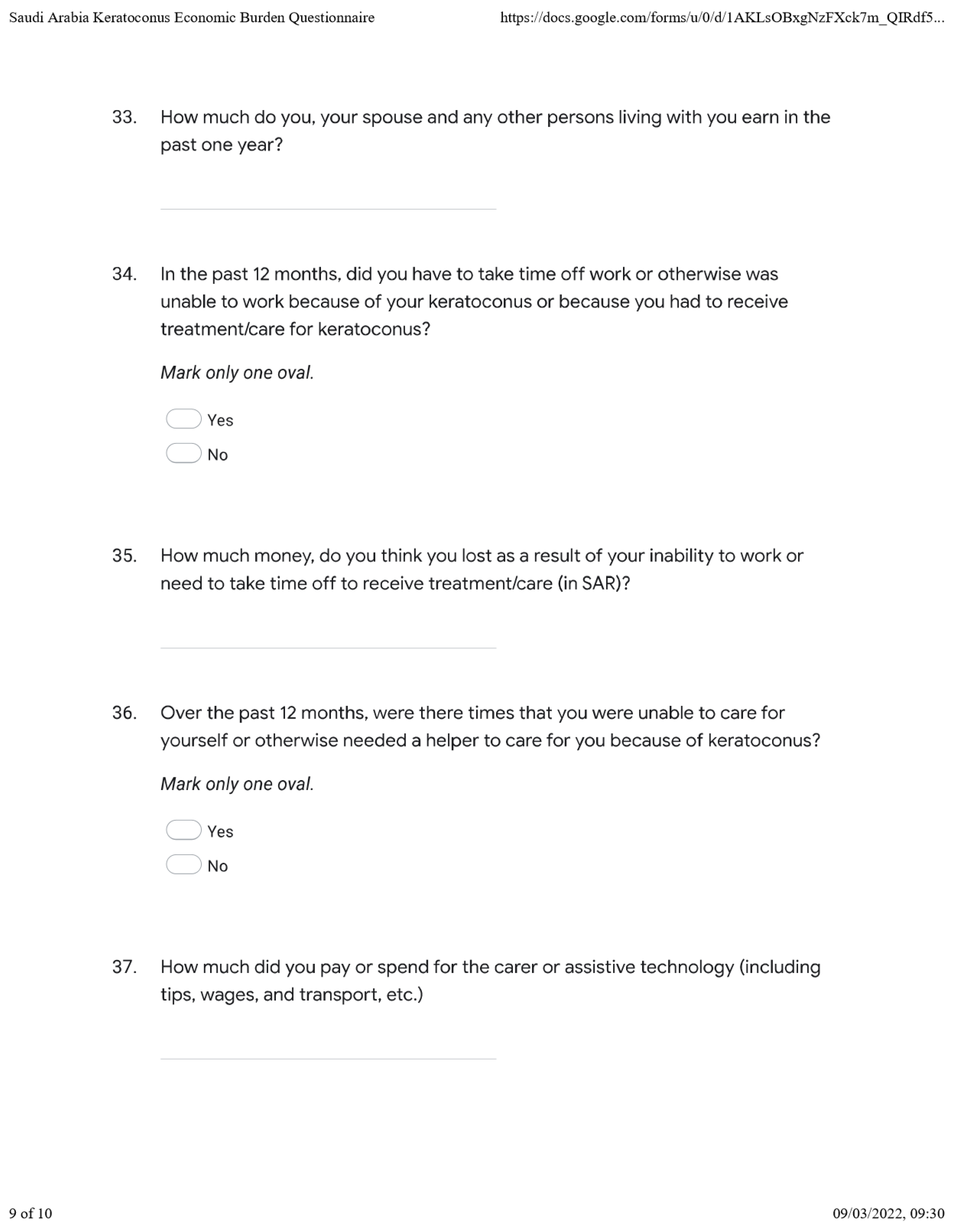

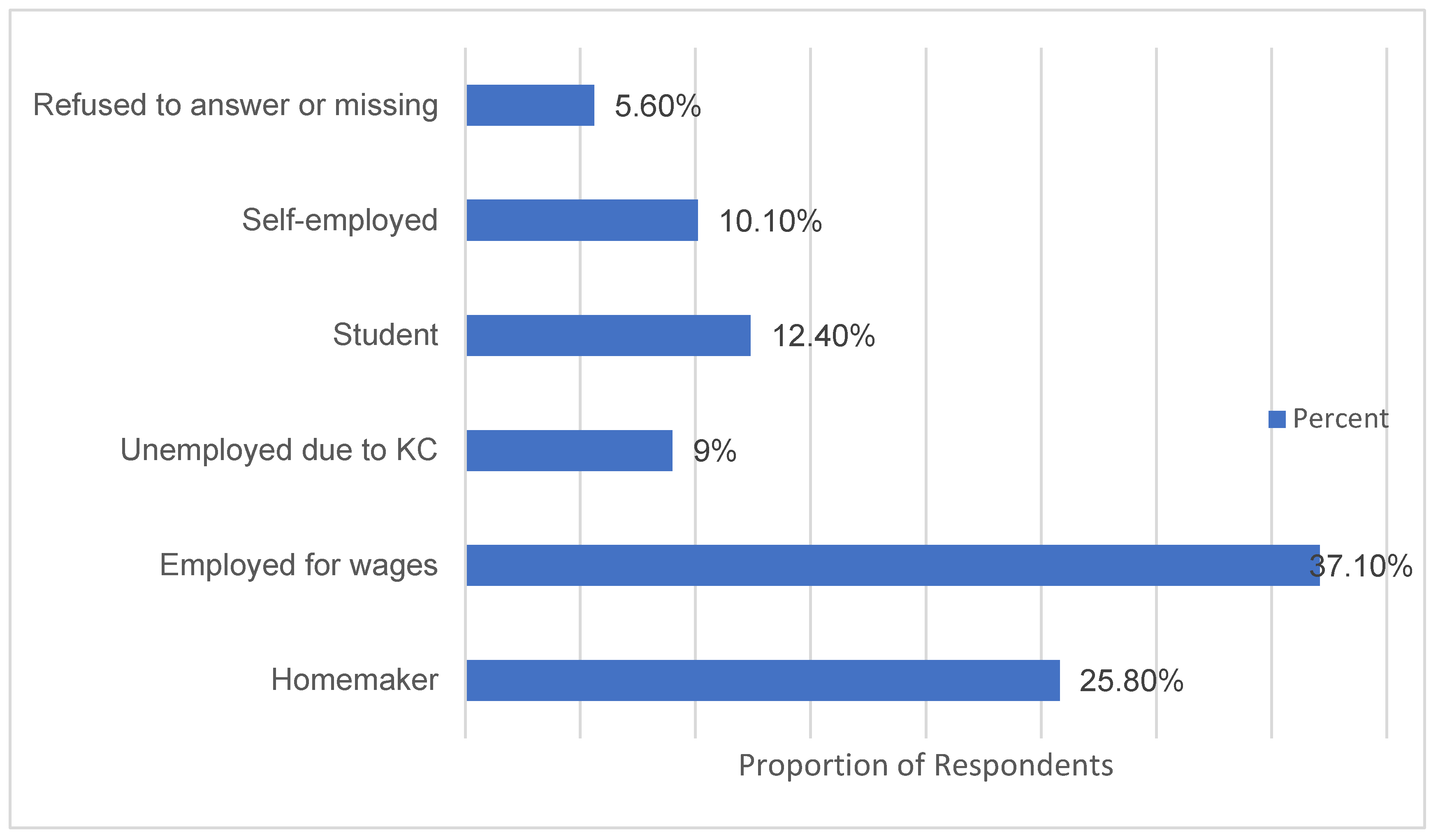

The findings show that close to half of respondents are forced to take time off work or alter their career, leisure, educational, and even professional choices on account of keratoconus, which, potentially implies suboptimal decision-making with equally sub-optimal financial and economic implications. The results show an estimated 10% of the sampled population are completely incapable of working or finding work due to keratoconus. Godefrooij et al. estimated the twelve-month losses at AUD 500 for an Australian sample [

4].

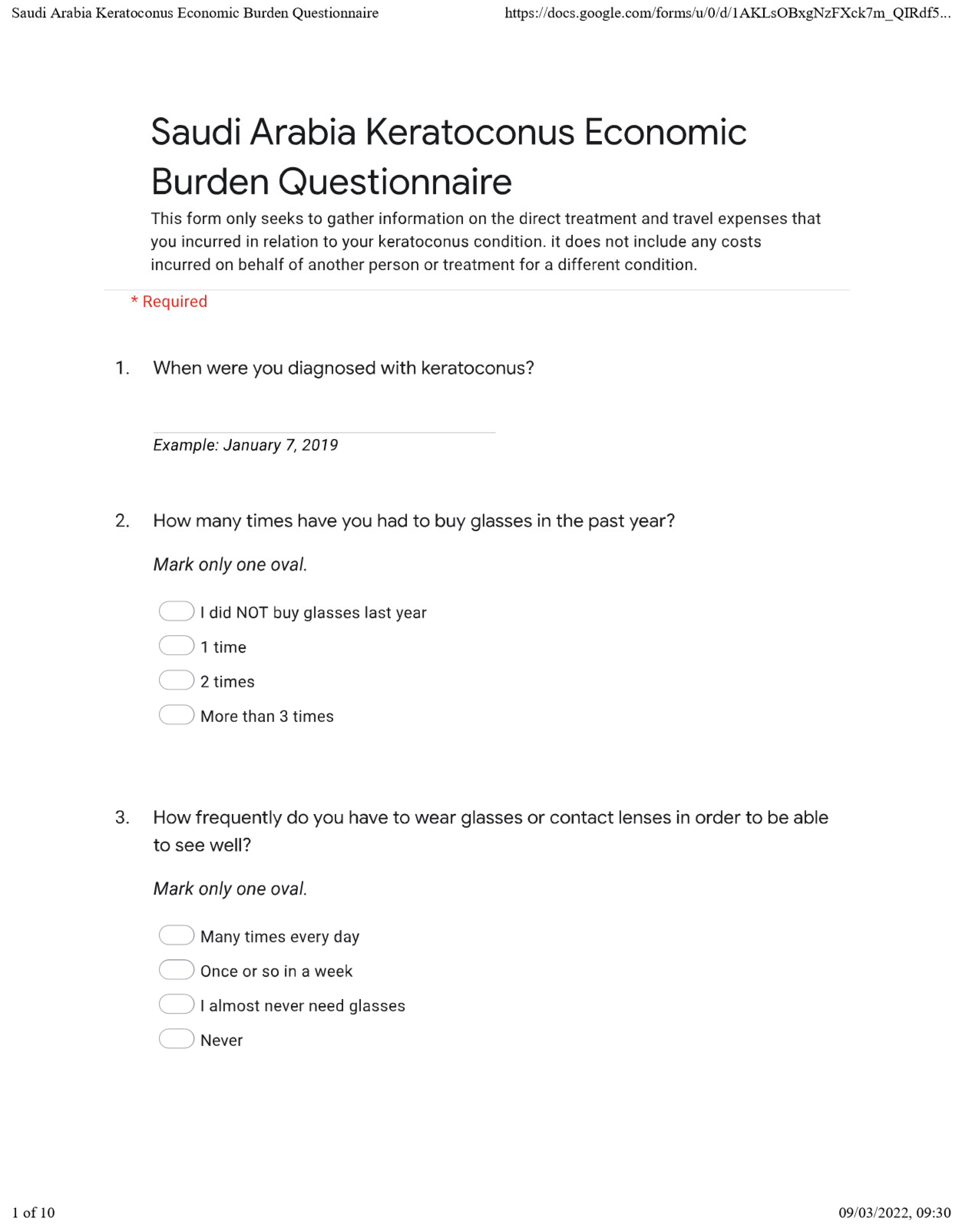

Keratoconus expenditure

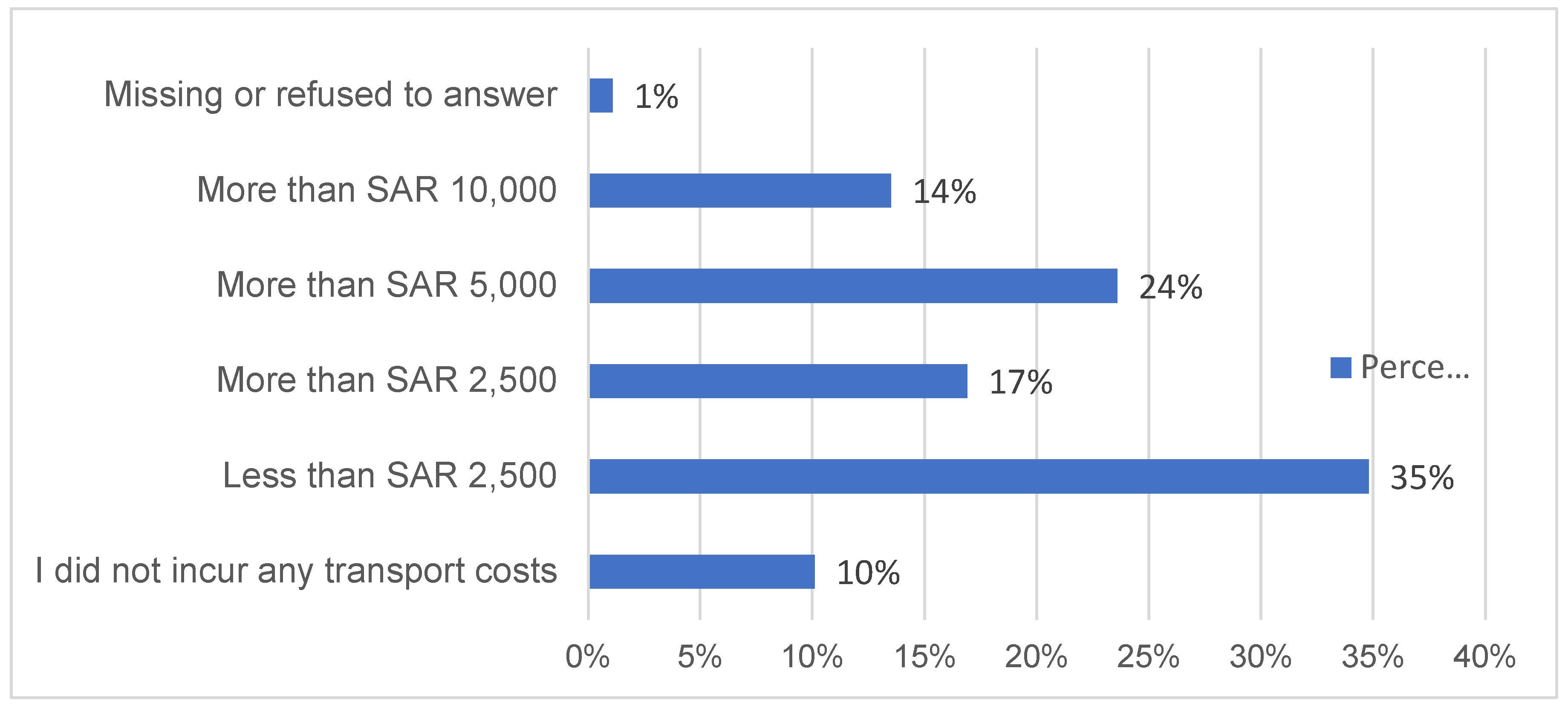

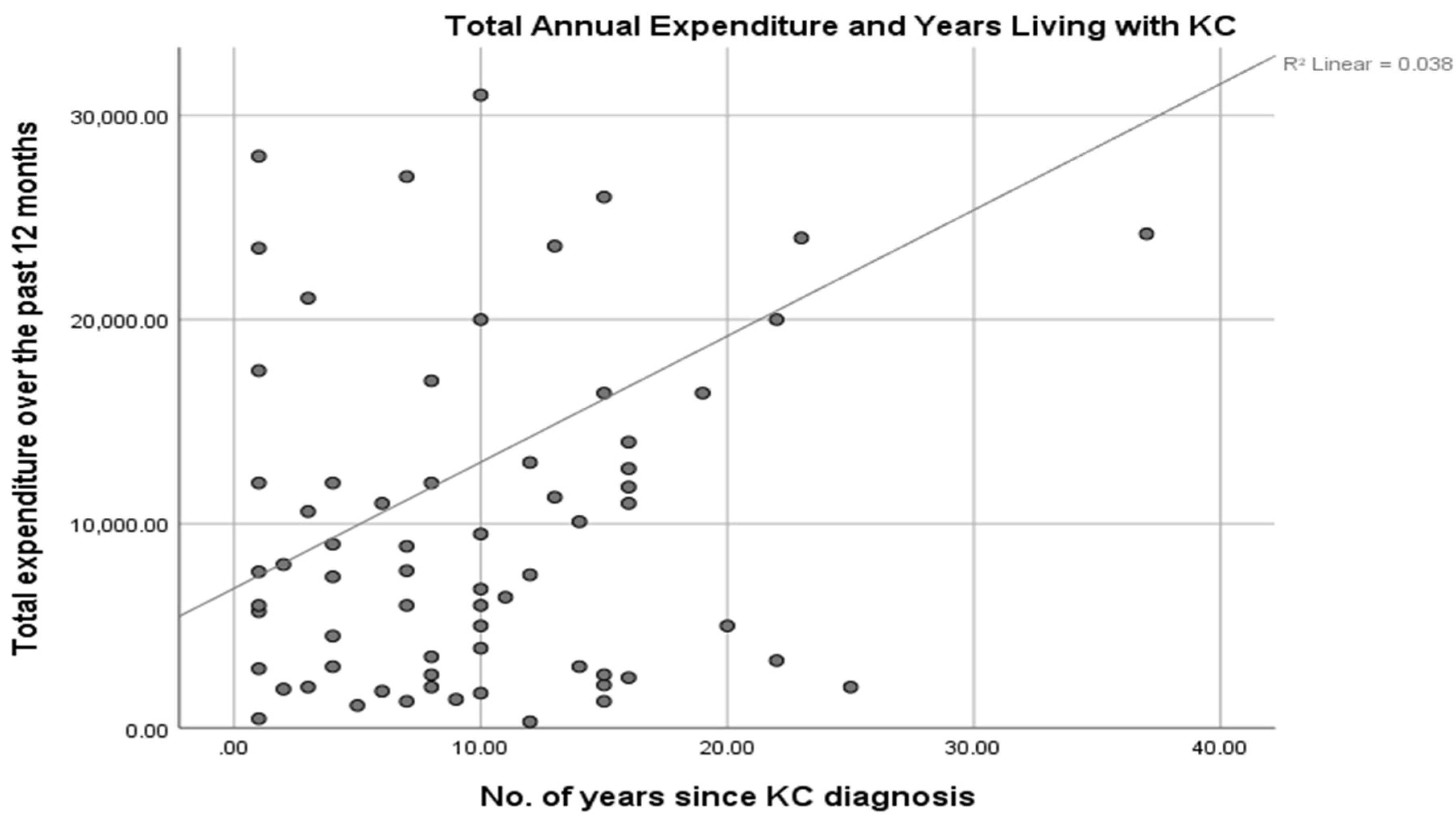

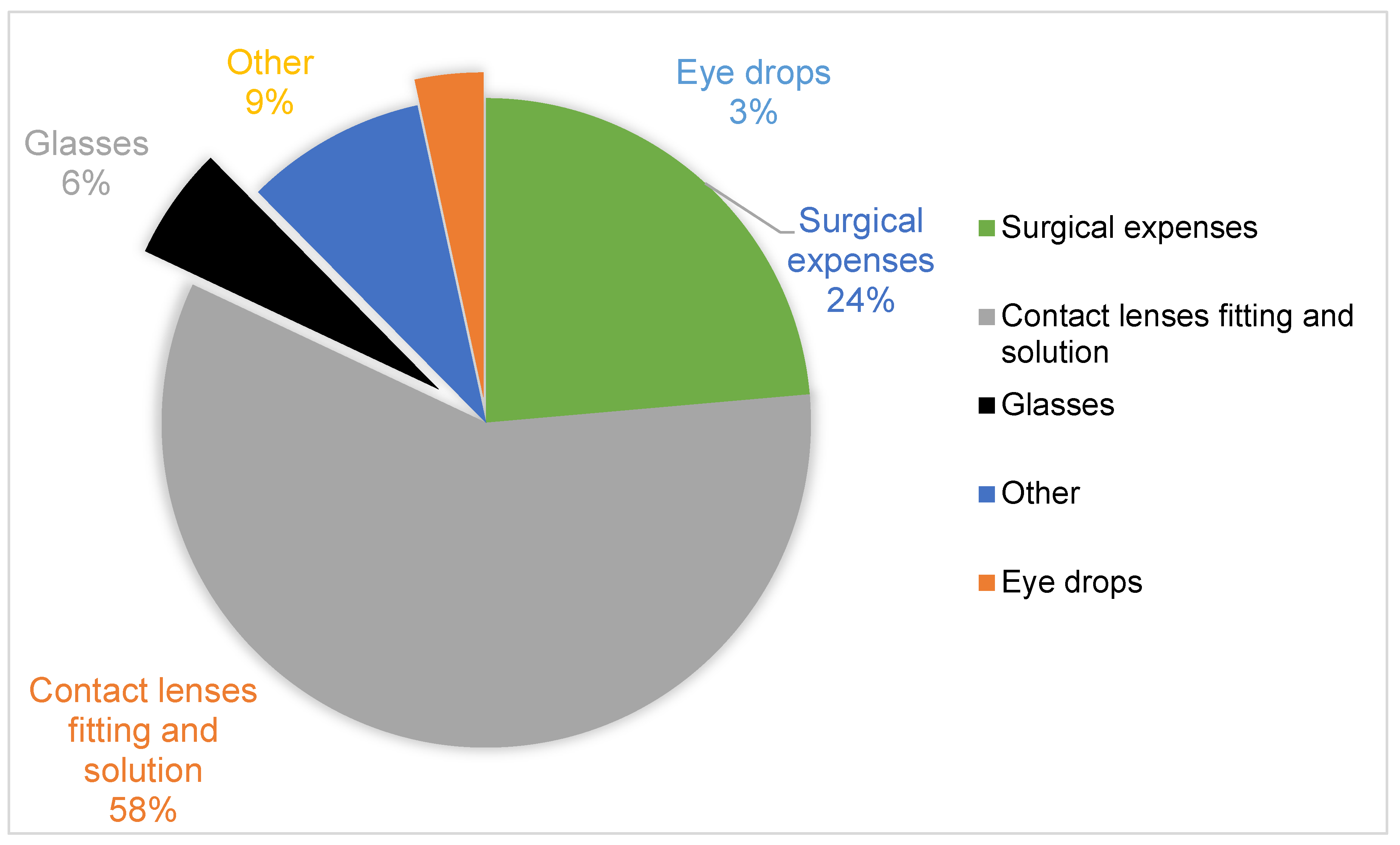

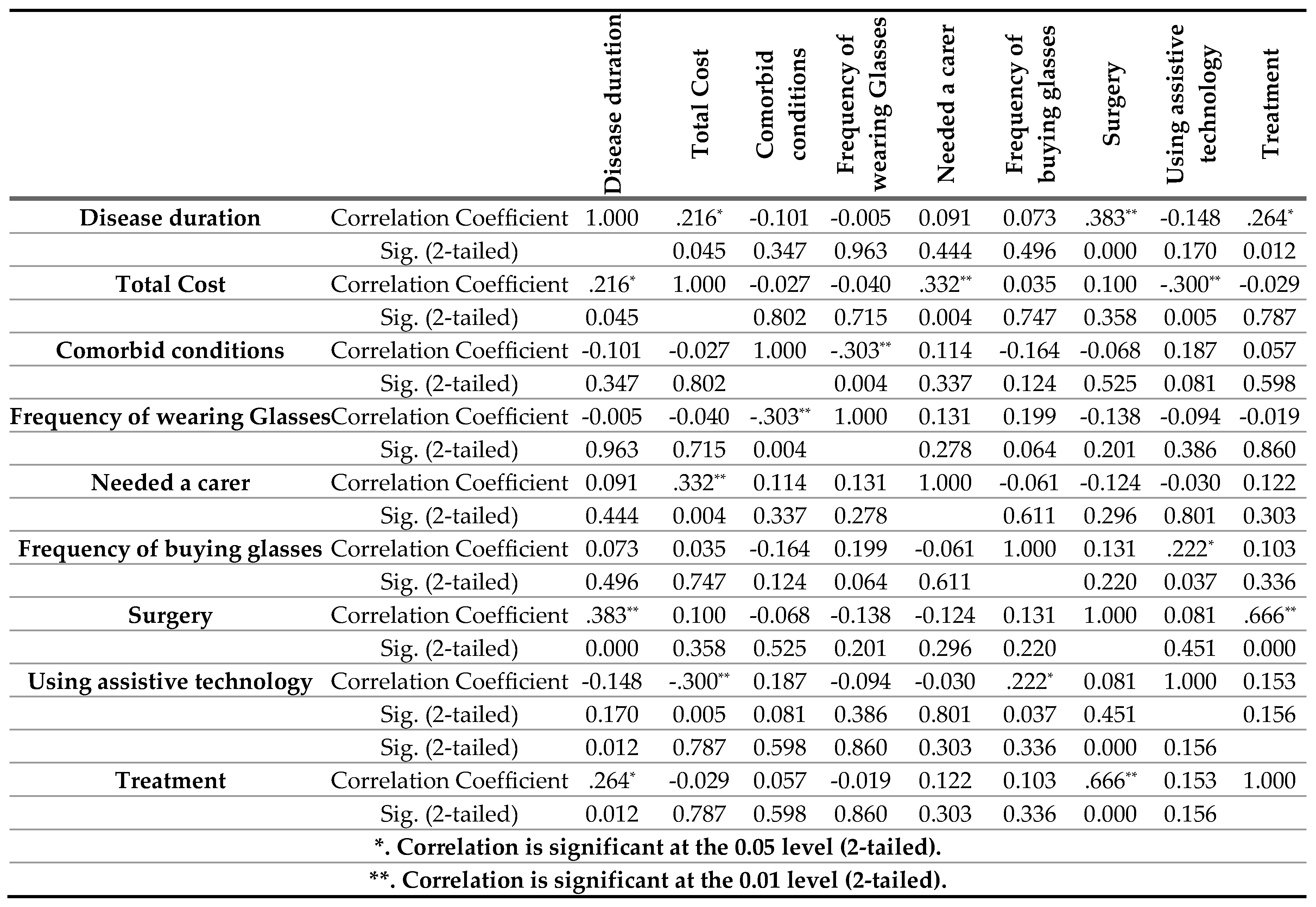

The calculated out-of-pocket costs for treating and managing keratoconus over twelve months, including the out-of-pocket expenses for glasses, contact lenses, and supplies, were SAR 8,673.19. Additionally, the majority of the keratoconus patients incurred SAR 2,500 to SAR 13,000 on transport, accommodation, and other ancillary expenses in seeking treatment. While this study did not verify the participants’ incomes, if indeed 46% of those sampled had no income and 15.73% had an annual income of not more than SAR 8,673.19, keratoconus potentially has debilitating economic effects on the patients. Unlike Godefrooij et al. [

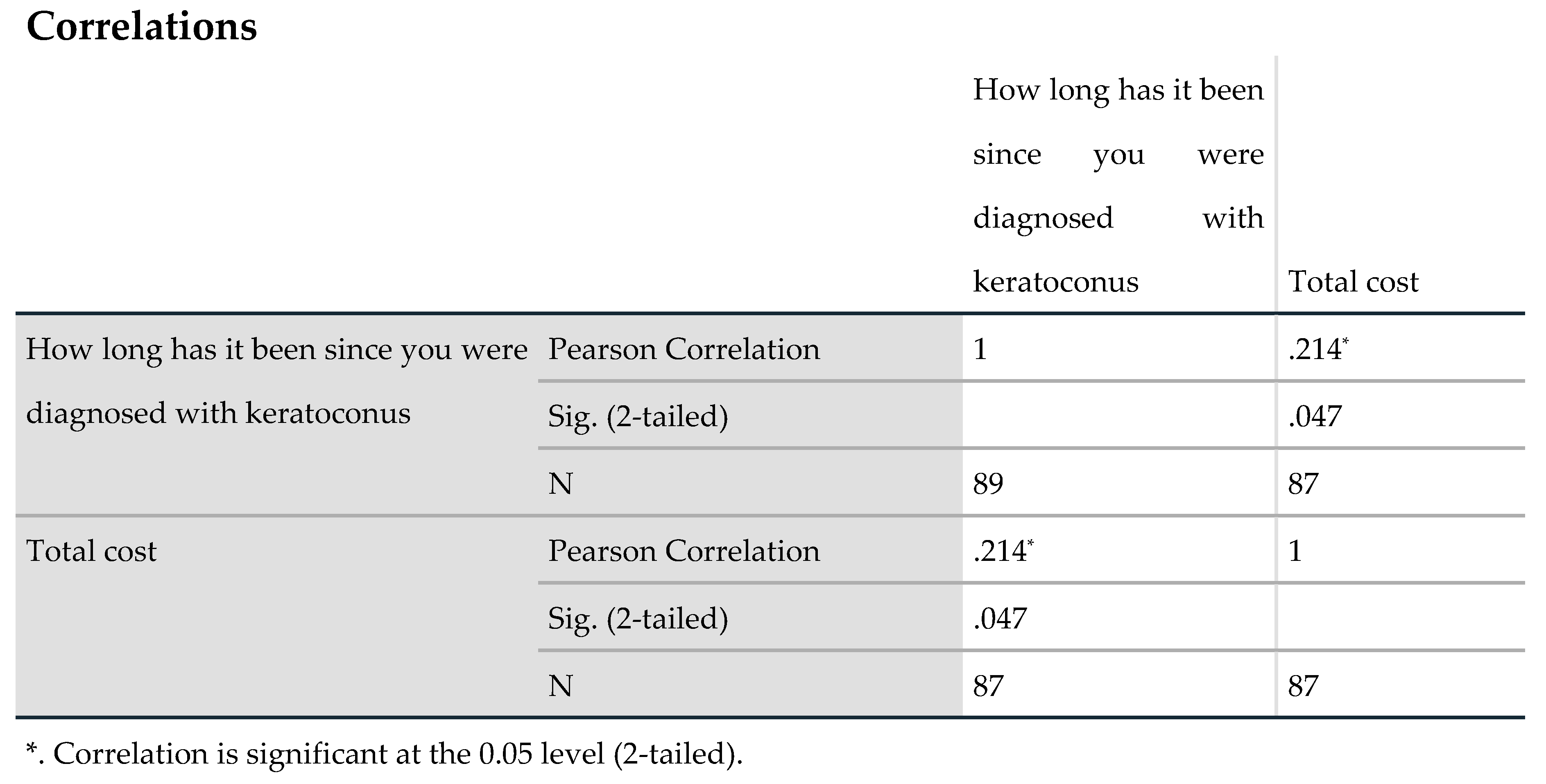

4], this study’s findings show that the expenditure is a positive function of the disease duration, possibly because the costs depend on the quality of treatment/care and whether or not such treatments stem the progression of the condition [

27].

With glasses, the condition is correctable in the early stages but the failure to treat the underlying causal factors often fails to stem its progression [

28]. Corneal collagen cross-linking can stop keratoconus progression, but it’s often not covered by insurers despite leading to lower costs in the long term [

1]. In a study to ascertain the cost-effectiveness of corneal collagen cross-linking in the USA, Canada, and Western Europe, Leung et al. [

9], Salmon et al. [

10], and Lindstrom et al. [

11], established that patients who undergo corneal cross-linking enhance their quality of life, are less likely to require penetrating keratoplasty, and incur lower lifetime costs or productivity losses. They spend 27.9 fewer years in advanced keratoconus stages [

11]. In Lindstrom et al.’s study, the direct medical costs for patients that underwent corneal collagen cross-linking were

$8,677 lower, i.e.,

$30,994 compared to

$39,671. The per capita lifetime productivity gains associated with corneal cross-linking were estimated at

$43,759 [

11].

Unlike Godefrooij et al. [

4], Leung, et al. [

9] and Rebenitsch et al. [

24]., this present study did not estimate the lifetime costs of the disease but focused on the individual cost drivers as predictors of the overall lifetime costs. This is arguably more practically relevant information for patients, practitioners, and policymakers. At 5% significance level, the regression results indicate that comorbid eye conditions, changing glasses frequently, and wearing glasses or contact lenses frequently are likely to result in lower lifestyle and medical costs of keratoconus. There are two possible explanations for this counter-intuitive finding. Past studies show that prescriptions to treat comorbid conditions and medication usage tends to be significantly higher among patients with some other eye conditions like dry eye disease. There is similarly a relationship between ocular comorbidities and systemic diseases such as diabetes with implications for effective and efficient detection and management [

9,

27].

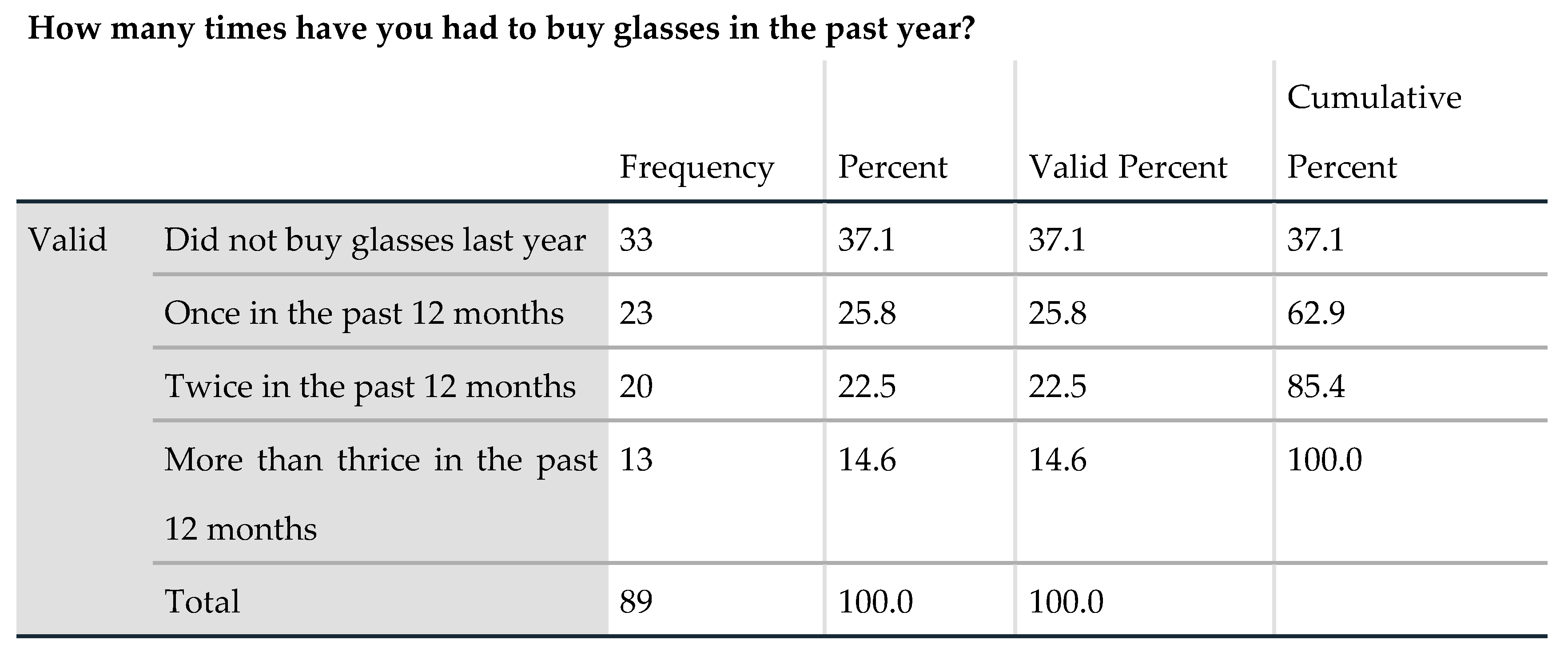

With a third of the sampled population in this study has not changed their glasses, it appears that the direct cost incurred in buying glasses is significantly lower than the indirect costs of either not wearing glasses or using poor glasses. Specifically, changing glasses once in twelve months and wearing either glasses or contact lenses at least once a week are likely to result in SAR 3,479.49 and SAR 10,429.30 lower annual total costs, respectively. On the contrary, a five-year disease duration is likely to result in SAR 5372.36. Patients who attended optometric clinics at least once in twelve months are likely to have SAR 10,759.03 more in total costs. The results are inconclusive on the cost impact of undergoing keratoconus surgery, attending either public or private clinics, and assisted living due to keratoconus. Thus, more research, with larger and more robust sampling is required to settle these findings.

Given the high hospital utilisation by keratoconus patients and the high cost of care, the lack of health insurance and/or government cover for the treatment and other costs has immense implications[

1,

9]. This study found that 73% sought optometric services over the preceding year, and close to 50% sought services from other services, which rates are comparable to higher utilisation rates elsewhere. Similarly, more research is required to investigate the impact of insurance cover on health services utilisation and health outcomes, including the age of diagnosis, health-seeking behaviour for patients with keratoconus, and the treatments open to them. While the actual costs are likely a function of income and lifestyle factors[

1], this study’s finding of comparatively higher average out-of-pocket expenditures relative to the less than SAR 5,000 paid by the majority of respondents in premiums shows a possible need for increased insurance coverage. This study identified an existing need for health insurance policies to cover fitting contact lenses and lens solutions, surgical expenses, and glasses.

Type of care

Keratoconus requires multi-disciplinary management, including primary eye care practitioners, general practitioners, ophthalmologists, and optometrists [

11]. The condition is difficult to detect at early stages and it’s usually possible to achieve good visual acuity with standard glasses, resulting in the unchecked progression of the disease. Studies into the sequence of events leading up to the keratoconus diagnosis show lack of awareness among patients and the criticality of referrals from primary points of contact to optometrists, ophthalmologists, and other specialists[

29,30].

Collaboration is, however, little known and efforts are usually geared towards most prevalent eye diseases, age-related disorders, and primary care referral patterns[

29]. Advanced stage keratoconus is difficult to correct and it’s a common indicator of corneal surgery[

9,

10]. An estimated 20% of keratoconus patients require corneal transplantation [

10]. This study shows acceptably high utilisation of both optometrists and other facilities, but there is a case to be made for the services offered by non-optometrists to increase from 38%. This is not least because the services sought from both optometrists and other practitioners appear to be the same when more differentiated services are possible. The potential for co-management and referral of cases across specialist/practitioner groups and from primary care to specialist care levels exists in the diagnosis and effective and efficient management of keratoconus[

29].