Introduction

Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome caused by SARS-CoV-2 emerged at the end of 2019 in Wuhan from Hubei, China, and quickly spread around the world. COVID-19 was declared an International Public Health Emergency on January 30, 2020, and on March 11 of the same year it was declared a pandemic by the World Health Organization (WHO)1. On February 26, 2020, in the state of São Paulo, Brazil registered the first case of the disease2.

As June 3, 2022, COVID-19 has taken the lives of more than 6.2 million people worldwide3. In Brazil cases exceed the 30 million, where more than 660 thousand people died from the virus. These numbers could have been reduced if mass protection measures against COVID-19 were adopted4.

Among the protection measures indicated by national and international organizations, non-pharmacological ones stand out, such as social distancing, hand hygiene, use of masks, cleaning and disinfection of environments, isolation of suspected and confirmed cases, and quarantine for cases of COVID-195.

Preventive behavior is one of the main strategies to contain the spread of the virus, especially at a time when vaccination is not yet adequately covered. Faced with a pandemic, caused by rapid viral spread among humans, it is important to understand the factors that influence people’s behavior in adherence or hesitation to protective measures and the way the population behaves during a health crisis. This understanding can help in the formulation of communication and intervention strategies aimed at minimizing the impact and dissemination of the disease.

Scientific evidence reinforces the importance of adherence to protective measures in combating COVID-196, however in Brazil there are still few studies with this objective, notably to highlight the factors associated with the risk behavior of the population about contracting and disseminating COVID-19. Given the above, the aim of the study was to analyze the behavior of the Brazilian population, adherence to protective measures that contributed to the lack of control and dissemination of the disease, a period in which the vaccine coverage was still incipient.

Method

This is a cross-sectional study, of the Survey type, conducted online between August 2020 and February 2021. The study was conducted according to the recommendations of the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology''7.

For study population was considered the general Brazilian population, who declared themselves resident in Brazil, aged 18 years or older, with access to the internet and who was willing to participate in the study. People who did not fully respond to the research instrument were excluded.

For sample design, the study was based on convenient sample8, using the snowball technique, which is characterized by not adopting margin of error calculations, since it is a non-probabilistic method. For data collection, the survey was "COVID-19 Social Thermometer: Social Opinion", which was developed and validated by researchers from the National School of Public Health of the New University of Lisbon (ENSP/UNL) from Portugal9,10,11. The adaptation of the survey to Brazil proved to be sufficiently valid and reliable for its wide application in the Brazilian population.

Survey is composed of 151 fields, from multiple choice questions, in Checklist format, using Likert scale, with five possibilities for answers (totally agree, partially agree, partially disagree, totally disagree, I don´t know).

The survey was developed and hosted on the Redcap platform of the University of São Paulo (USP) Ribeirão Preto campus. Redcap is a software of electronic data capture (Electronic Data Capture – EDC) browser-based and metadata-oriented with workflow methodology for designing clinical and observational research databases12.

The survey was available to the eligible public through the websites of the research institutions participating in the study and through emails, “WhatsApp”, social networks, media and blogs. When accessing the survey, the Term of Consent was made available (TCLE) to the study participants, with the instructions for completing and presenting the purpose of the research.

From the set of variables of the questionnaire, it was considered as an outcome of interest the adoption of protection measures against COVID-19, which was evaluated by the following question: “Which Measures You Have Taken to Avoid Becoming Infected with COVID-19?” This question was evaluated continuously and included 13 answer options.

The independent variables were: Age (18 to 39, 40 to 59, 60 or more), Gender (Male, Female), Schooling (Incomplete or less higher educations, Complete higher education, Postgraduate or more), Race/Color (White, Black, Brown, Yellow/Indigenous), Marital status (Married/Stable union, Single/Divorced/Discharged/Legally separated, Widowed), Have health insurance (No, Yes), Use of the Public Health System (No, Yes), Receiving a visit from the Community Health Agent (No, Yes), Receiving some government social support (No, Yes), Loss of monetary income during the pandemic (No, Yes), Smoking habit (No, Yes), Religion (some religion/ no religion), Present some chronical disease: Asthma (No, Yes), Hypertension (No, Yes), Diabetes Mellitus (No, Yes), Obesity (No, Yes).

For the study descriptive and inferential analyses were performed. The descriptive occurred through the calculation of frequencies with 95% confidence intervals (95% CI). The descriptive analysis was performed considering the two research outcomes (did not adopt any measures, adopted all measures).

The associations were evaluated by Poisson regression13 and considering the cross-sectional design of the study, the measure of association was the prevalence ratio (PR), with their respective 95% CI. Crude and adjusted analyzes were performed for the variables sex (male, female), skin color (white, black, brown or yellow/indigenous), age (18 to 39 years, 40 to 59, 60 years or older), schooling (incomplete higher education or less, complete higher education, postgraduate or more) and marital status (married, separated/unmarried, widowed). The analyses were performed using Stata software, version 15.1.

For the spatial analysis, all 5,568 Brazilian municipalities14 were considered as the unit of analysis, for which the incidence and mortality rates due to COVID-19 were calculated, with the number of cases (or deaths) in the numerator, the population of the municipality as denominator and the multiplication factor per 1,000 inhabitants.

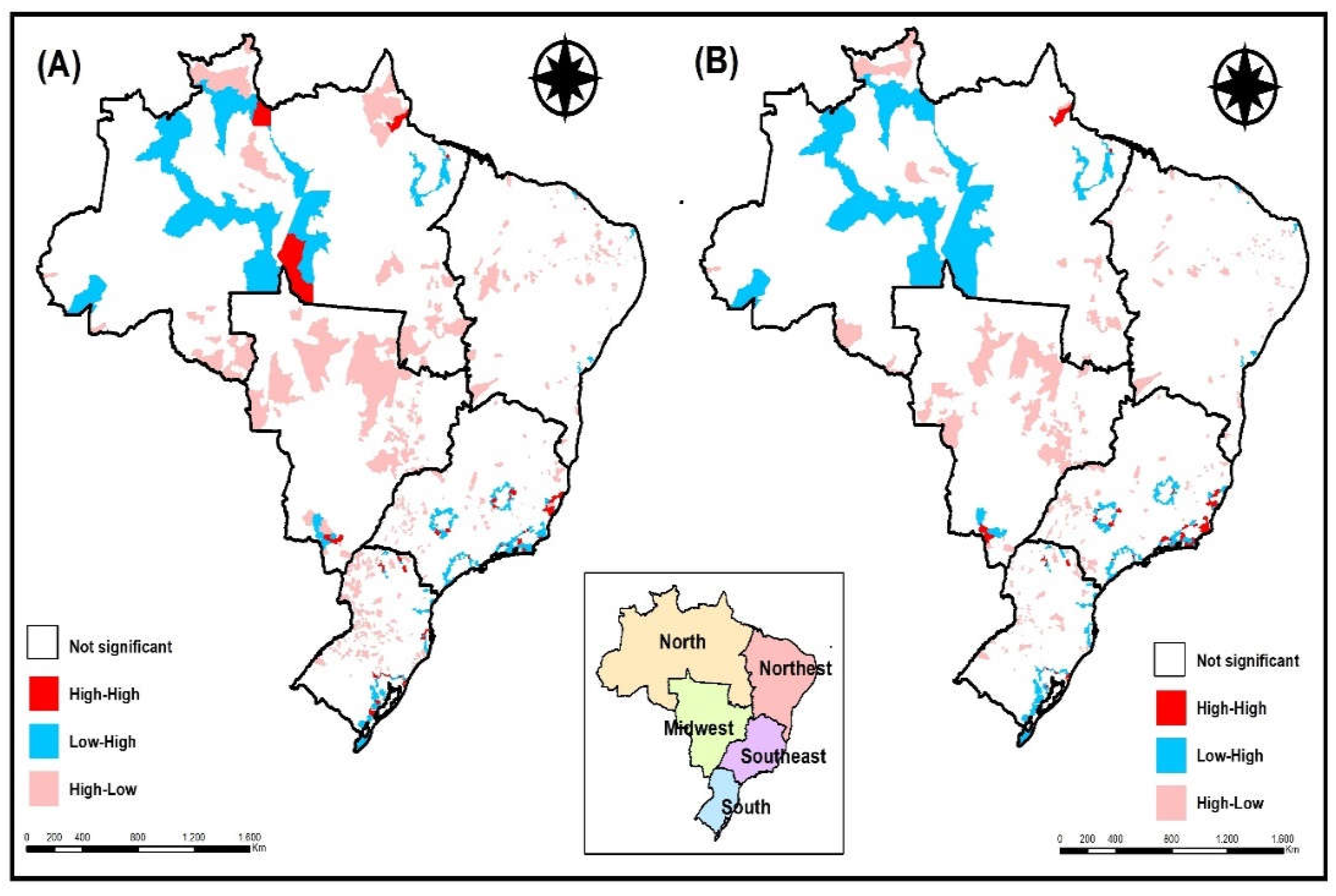

The Local Bivariate Moran Index15 indicates the degree of association (positive or negative) between the value of the variable of interest in each region and another variable in the same region, and thus it is possible to map the statistically significant values, generating a choropletic map according to its classification.

In this study, spatial autocorrelation between COVID-19 incidence and mortality rates was tested with people who adopted at least one measure of protection against COVID-19.

The classification can be: High-high (high values of incidence or mortality from COVID-19 with a high number of people who have adopted at least one protection measure against COVID-19), Low-low (low values of incidence or mortality from COVID-19 with low number of people who have adopted at least one protection measure against COVID-19), Low-high (low values of incidence or mortality from COVID-19 with a high number of people who have adopted at least one measure of protection against COVID-19) e High-low (high COVID-19 incidence or mortality values with low number of people who have adopted at least one protection measure against COVID-19).

It is noteworthy that the high and low values are classified according to the mean values of the variables of the neighboring regions15.

Results

There were 1,516 participants from the five macro-regions of Brazil.

Table 1 shows the main characteristics of these participants, general and stratified by adoption of protection measures against COVID-19.

Most participants were female (73.0%), reported white skin color (68.1%), aged between 40 and 59 years (41.8%), single (as), divorced (as), discharged (as) or separated (as) judicially (50.4%) and had postgraduate level or more (50.4%). About 73.1% had health insurance and 64.0% used the Health Public System (SUS). It was observed that 19.1% (95%CI: 17.2 - 21.2) of the people did not adopt any protection measure against COVID-19.

Figure 1 shows the application of the Local Bivariate Moran Index, which refers to the incidence rate for COVID-19 with people who have adopted at least one protection measure against COVID-19 (Fig 1 - A), there is a positive spatial association (High-high) in municipalities of all big regions of Brazil, except for the Northeast region, and negative spatial association (Low-low) in all five Brazilian big regions.

Regarding the COVID-19 mortality rate with people who have adopted at least one protection measure against COVID-19 (

Figure 1B), it was possible to observe the same pattern described earlier, with municipalities classified as

High-high (positive spatial association) present in all big regions of Brazil, with the exception of the Northeast, and classified as

Low-low (negative spatial association) in all five Regions of the country.

Regarding the association between protective measures and sociodemographic factors, women took greater care in preventing COVID-19, and adopted protective measures 10% (95%CI: 1.05-1.15) more than men, results that remained significant even after adjustments for confounding factors (PR = 1.09; 95%CI: 1.04-1.14). In a previous studies developed in the United States, being female was considered a protective factor during the COVID-19 pandemic, since the female population has a greater adherence to the use of face masks when compared to men16,17. Historically, evidence shows that women tend to be more aware of their health status as well as seek care more proactively than men 18.

In the analyzes performed in this study, the age group between 40 and 59 years was the one that had the highest adherence to protection measures against COVID-19. Other studies corroborate this finding, since it has been observed that the increase in age is associated with higher morbidity and mortality, especially non-communicable chronic diseases, so that with advancing age, people are more likely to adhere to disease prevention and protection measures16.

A study conducted in Hong Kong during the swine flu pandemic showed that older people tend to take greater precautions with their health. Already during the COVID-19 pandemic in the United States, an observational study showed that the older the age the better adherence to protective measures16,17.

The results show that, even after adjusting for confounding factors, schooling was a protective factor against COVID-19. Those with complete higher education had a prevalence ratio of 8% (95%CI: 1.02-1.15) higher and those with postgraduate education or more 17% (95%CI: 1.11-1.24) had to adopt protective measures compared to those who had incomplete or less superior.

Studies indicate that the level of education is an important factor for adherence to individual and collective protection measures since a lower level of education reflects less access to information19. In Saudi Arabia, the level of knowledge about COVID-19 was directly associated with school level and family income20.

Lower education is a social vulnerability, and the most vulnerable population generally has less access to information for decision-making and less financial conditions to remain in quarantine. Thus, it can be assumed that less favored communities, with lower education, aggravated by lower income and less access to health services, suffer more from health inequities that were even more evident during the pandemic.

The results indicate that people self-declared black adopted fewer protective measures when compared to people with other skin color. Although the statistical significance of the categories is not maintained after adjusting for confounding factors, it is important to point out that in Brazil there are significant socioeconomic inequalities related to ethnic-racial issues, and most Brazilians with low income, lower education and less access to health services are black21.

In Brazil, 73% of the poor population is black22, it is worth noting that the average of deaths from COVID-19 in the five regions of Brazil was higher among black people, a fact that shows that this population is more exposed to being victims of the disease21. Then it is important to reflect that inequality is of great importance in social determinants in health and that this will reflect on how this population adheres or hesitates to protective measures19,21.

In a meta-analysis carried out during the COVID-19 pandemic, it was found that smokers are in the risk group of those most susceptible to complications of the disease, especially those who need hospitalization23 and this fact was widely publicized in the media, causing greater concern in this group. In the present study, it was identified that people who self-declared as smokers showed more care regarding protection against the infection of the new coronavirus when compared to people who do not have the habit of smoking.

In general, the arrival of the new coronavirus in the world has also shaken global religion, because it is known that historically religion and illness have a strong relation of mutual influence. In Brazil, the conflict between "science and religion" gained notoriety, causing political and social repercussions24. While the world was discussing the closure of mosques, suspension of religious meetings, cults and masses, in Brazil, the Presidential Decree nº 10.292, of March 25, 2020, was published25, establishing that religious activities of all kinds should be regarded as essential services, thus exempt from measures of social isolation.

The findings of this research showed that people with some religion adopted fewer protective measures when compared to people who defined themselves without religion, even after adjusting the confounding factors (

Table 2).

Table 3 shows the association between the adoption of protective measures with situations of vulnerability and health services. The results showed that there was significance between the loss of income during the pandemic and adherence to protective measures, but the results lost statistical significance after adjustments to confounding factors. Similar results were found among those receiving government social support.

Participants who received visits from community health agents adopted fewer protective measures, even after adjusting for confounding factors (PR: 0.93; 95% CI: 0.93-0.98). Compared to those without health insurance, those who had health insurance were more likely to adhere to protective measures against COVID-19, even after adjusting for confounding factors (PR: 1.07; 95%CI: 1.02-1.13). The use of SUS showed no association with the adoption of protective measures.

From a social perspective, it is possible to assume that those who have health insurance have better financial conditions and that those who receive visits from the community agents have a more unfavorable socioeconomic situation, so that adherence to social isolation, for example, would cause loss of source of income, since in Brazil, an important portion of the population works informally. This fact corroborates the findings about the lower income English population, who would like to be in isolation during the pandemic, but has this possibility decreased by up to three times in relation to the higher income segments26.

Therefore, we emphasize the importance of income transfer policies for the portion of the population that cannot isolate themselves, as a way to expand the strategy to combat the pandemic, while minimizing the impact on social well-being.

Table 4 shows the association between adherence to protective measures and carrying non-communicable chronic diseases. Being a carrier of Asthma, Diabetes Melittus, Systemic Arterial Hypertension and Obesity were factors that increased the adherence of protective measures in the fight against COVID-19, even after adjustments to confounding factors.

Although the epidemiological profile of people affected by COVID-19 is not fully understood, studies indicate that the most severe forms of infection are more likely to occur in the elderly and in individuals with comorbidities23. In addition, mortality is also significantly higher among the elderly with pre-existing health conditions, such as systemic arterial hypertension, cardiovascular diseases and diabetes mellitus 27.

Several studies have reported that patients with chronic diseases have more unfavorable outcomes regarding hospitalizations and mortality23, and data from information systems in the country confirm this evidence. In the study "Social Barometer in Portugal", the elderly and those with chronic diseases considered themselves at high risk of developing a severe course of the disease in case of COVID-19 infection9. This self-perception of risk is considered a protective factor, since those who consider themselves more likely to have complications from the disease tend to protect themselves more.

In Brazil, these diseases affect almost half of people aged 65 years or older (44.6%), population vulnerable to COVID-19, namely due to age-related fragility and immune system decline. In fact, morbidity seems to be the strongest determinant of the perception of risk of becoming ill and presenting complications resulting from the disease, which consequently increases adherence to protective measures.

The plausible risk of worsening COVID-19 has been widely reported by the media, medical societies, public health institutes, health authorities and patient organizations. Therefore, it is not surprising that people with comorbidities were particularly concerned about the risk of developing severe outcomes after COVID-19.

This study evaluated the adherence of measures to protect the Brazilian population during the COVID-19 pandemic in the country. Data were collected at the first moment of the pandemic, where isolation measures were more restrictive, vaccination was restricted to priority groups (health professionals and the elderly), and much misinformation circulated. The results show that almost one fifth of the sample did not adopt any measures to protect themselves from the new coronavirus, and that sociodemographic determinants and the presence of chronic diseases are associated with preventive behaviors.

Other pandemics have occurred in history, some with repeated cycles for centuries, such as smallpox and measles, or for decades, such as cholera. Influenza pandemics by H1N1, H2N2, H3N3 and H5N1, known respectively as "Spanish flu", "Asian flu", "Hong Kong flu" and "avian flu", however, the COVID-19 numbers are alarming.

In just over two years of the new coronavirus pandemic, there are already more than 530 million confirmed cases in the world, especially Brazil, which is in 3rd place in the ranking of cases, surpassing the range of 31 million infected people, lagging only the United States and India3. Such numbers may be associated with the low adherence of the population to protection measures against COVID-19, which may have been triggered by the little government investment in health education actions, as well as, by economic pressures against the measures of isolation and social distancing6.

Understanding how the population protects itself and what factors are considered protective is part of the process for formulating strategies to contain the virus. Being female, aged 40 to 59 years, higher education, smoking, not having a religion, having health insurance, and being a carrier of chronic diseases were associated with greater adherence to protective measures against COVID-19.

Although the present study sought to obtain a representative sample of the Brazilian population, the method used, as a convenience sample in the online modality, represented a limitation of the study. When it comes to online research, individuals with higher education are the most involved, a fact that can be observed in research with this characteristic approach observed in this study28,29.

The difficulty of access to the internet, as well as the restricted access to some social layers has already been cited in the literature as a research bias, since the possibility that the participants of the research were composed mainly of people with high level of education and higher income, as already demonstrated in other studies30.

Even in the face of the social vulnerability that the pandemic has generated in the country, a key point for its confrontation is the adhesion of protective measures. The survey data showed that most respondents are contributing to this purpose. This refers to the urgency of social protection measures and financial support, primarily for the most vulnerable social segments.

It is suggested in future studies, the continuity of this with isonomy of the sample contemplating the greatest social diversity, since the method used excluded an important portion of the population that did not have access to the online survey. Certainly, a methodological design that includes follow-up or longitudinal measures is important for monitoring the behavior of all segments of the population and at all stages of the pandemic.

Author Contributions

Araújo, JST participated in the design and writing of the manuscript. Delpino,FM participated in the statistical analysis of the study, Nascimento, CM participated as the second reviewer of the article and writing of the manuscript. Moura,HSD; Ramos, ACV; Berra TZ; Soares,DA participated in the revision of the studies.. Arcêncio RA, participated in the writing and revision of the final version of the articleAll authors reviewed and approved the final version to be published, assuming responsibility for all aspects of the work, including ensuring its accuracy and integrity.

Competing Interests

None declared.

Statement of Ethical Approval

This research has been approved by the ethics and research committee under the number CAAE 32210320.1.0000.5240.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank all study participants who shared their experiences and perceptions for coping with COVID-19 in Brazil.

Declaration of conflict of interest

The authors declare that there are no conflicting interests

Apoio Financeiro

The present work was carried out with the support of the Coordination for the Improvement of Higher Education Personnel - Brazil (CAPES) - Funding Code 001 and the São Paulo Research Foundation (FAPESP) - Process 2022/08263-7.

Author list/ Authors' Contribution

Felipe Mendes Delpino, Doctoral Student in Nursing on the Graduate Programme in Public Health Nursing, Nursing College of Ribeirão Preto, University of São Paulo, Brazil,

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-3562-3246, fmdsocial@outlook.com Second reviewer, statistical analysis.

Antônio Carlos Vieira Ramos, PhD Student on the Public Health Nursing Graduate Program. University of São Paulo at Ribeirão Preto College of Nursing, Brazil,

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7862-1355, antonio.vieiraramos@outlook.com Second reviewer and writing of the manuscript.

Murilo César do Nascimento, PhD Student on the Public Health Nursing Graduate Program. University of São Paulo at Ribeirão Preto College of Nursing, Brazil and

2University of Minas Gerais. Departament of Maternal Child Nursing and Public Health/ School of Nursing. Brazil.

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-3436-2654, murilo.nascimento@unifal-mg.edu.br Second reviewer and writing of the manuscript.

Thaís Zamboni Berra, PhD Student on the Public Health Nursing Graduate Program. University of São Paulo at Ribeirão Preto College of Nursing, Brazil,

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-4163-8719, thaiszamboni@live.com, Second reviewer and writing of the manuscript.

Débora de Almeida Soares, Institute of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, NOVA – UNL. Lisboa. Portugal

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-4138-9393, deboralsoares@usp.br Second reviewer and writing of the manuscript and translation into English language

Ricardo Alexandre Arcêncio, Nursing College of Ribeirão Preto, University of São Paulo. São Paulo, Brazil

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-4792-8714, ricardo@eerp.usp.br Participated in the final revision and writing of the final version of the manuscript.

References

- OPAS. OMS declares public health emergency of international importance by outbreak of new coronavirus - OPAS/OMS | Organização Pan-Americana da Saúde. Organização Pan-Americana de Saúde https://www.paho.org/pt/news/30-1-2020-who-declares-public-health-emergency-novel-coronavirus (2020).

- https://www.unasus.gov.br/noticia/coronavirus-brasil-confirma-primeiro-caso-da-doenca.

- WORLD HEALTH ORGANIZATION (WHO). Coronavirus disease (COVID-19) Dashboard. Geneva: WHO; 2020b. Disponível em: https://covid19.who.int/. Accessed: 2021 July 2.

- CENTERS FOR DISEASE CONTROL AND PREVENTION (CDC). 2022 Novel coronavirus, Wuhan, China. 2022. Available: https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2022-nCoV/ summary.html. Accessed: 2022 July 3.

- Brasil. Ministério da Saúde. Secretaria de Vigilância em Saúde. Guia de vigilância epidemiológica: emergência de saúde pública de importância nacional pela doença pelo coronavírus 2020 – covid-19 / Ministério da Saúde, Secretaria de Vigilância em Saúde. – Brasília: Ministério da Saúde, 2022. 131 p.: il. ISBN 978-65-5993-025-8.

- Costa, B.C. P; Fernandes, A.C.N.L; Costa, D.A.V; et al.; Adesão da população ao uso de máscaras para prevenção e controle da COVID-19: revisão integrativa da literatura. Research, society and development, v. 11, p. e59311427831, 2022.

- Elm, E. V. et al. The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in.

- Epidemiology (STROBE) Statement: Guidelines for reporting observational studies. International Journal of Surgery 12, 1495e1499, 2014.

- 8. Naderifar, M., Goli, H. & Ghaljaie, F. Snowball Sampling: A Purposeful Method of Sampling in Qualitative Research. Strides Dev. Med. Educ. 14, 2017.

- Pedro, A. R. et al. COVID-19 Barometer: Social Opinion–What Do the Portuguese Think in This Time of COVID-19?. Portuguese Journal of Public Health, v. 38, n. 2, p. 1-9, 2021.

- Laires P.A., Dias S., Gama A., Moniz M., Pedro A. R., Soares P., et al. The association between chronic disease and serious COVID-19 outcomes and its influence on risk perception: Survey study and database analysis. JMIR Public Health and Surveillance [Internet]. 2021 Jan 1 [cited 2021 Sep 24];7(1). Available: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33433397.

- Soares, P. et al. Factors associated with COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy. Vaccines, v. 9, n. 3, p. 300, 2021. [CrossRef]

- Harris, P. A.; Taylor, R.; Minor, B. L.; Elliott, V.; Fernandez, M.; O’neal, L. et al. The REDCap consortium: Building an international community of software platform partners. J Biomed Inform. v. 95, p. 103208, 2019.

- Hilbe, J. (2009) Logistic regression models. London: Chapman and Hall/CRC.

- Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística (IBGE). Brasil em síntese [Internet]. 2022. Access: July 26, 2022. Available from: https://brasilemsintese.ibge.gov.br/.

- Wagner AK, Soumerai SB, Zhang F, Ross-Degnan D. Segmented regression analysis of interrupted time series studies in medication use research. J Clin Pharm Ther, 27(4):299-309, 2002. [CrossRef]

- Ávila, F. M. V. P., Nogueira, W. P., Góes, F. G. B., Botelho, E. P., Gir, E., & Silva, A. C. de O. e. (2021). Medidas não farmacológicas para prevenção da covid-19 entre a população idosa brasileira e fatores associados. Estudos Interdisciplinares Sobre O Envelhecimento, 26(2). [CrossRef]

- Haischer, M. H., Beilfuss, R., Hart, M. R., Opielinski, L., Wrucke, D., Zirgaitis, G. & Hunter, S. K. (2020). Who is wearing a mask? Gender-, age-, and location-related differences during the COVID-19 pandemic. Plos one, 15(10). [CrossRef]

- Hearne, B. N., & Niño, M. D. (2021). Understanding how race, ethnicity, and gender shape mask-wearing adherence during the COVID-19 pandemic: evidence from the COVID impact survey. J Racial Ethn Health Disparities, 1-8. [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, B. L. C. A. de, Thomaz, E. B. A. F. e S, Raimundo A. The association between skin color/race and health indicators in elderly Brazilians: a study based on the Brazilian National Household Sample Survey (2008). Cadernos de Saúde Pública [online]. 2014, v. 30, n. 7 [Acesseced August 11, 2022] , pp. 1438-1452. Available: <https://doi.org/10.1590/0102-311X00071413>. ISSN 1678-4464. [CrossRef]

- Alahdal, H., Basingab, F., Alotaibi, R. An analytical study on the awareness, attitude and practice during the COVID-19 pandemic in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. J Infect Public Health. 2020 Oct;13(10):1446-1452. Epub 2020 Jun 17. PMID: 32563674; PMCID: PMC7832465. [CrossRef]

-

Sthel, F.G., Silva, L.S. A crise da pandemia da COVID-19 desnuda o racismo estrutural no Brasil. Revista da Associação Portuguesa Portuguesa de Sociologia.2021. [CrossRef]

- Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística (IBGE). 2020 [Internet]. Censo demográfico. [Accessed 2020 May 22]. Available: https://cidades.ibge.gov.br/brasil.

- Emami, A., Javanmardi, F., Pirbonyeh, N., Akbari, A. Prevalence of Underlying Diseases in Hospitalized Patients with COVID-19: a Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Arch Acad Emerg Med. 2020 Mar 24;8(1):e35. PMID: 32232218; PMCID: PMC7096724.

- Carletti, A. Nobre, F. A Religião Global no Contexto da Pandemia de Covid-19 e como implicações político-religiosas no Brasil. Revista Brasileira de História das Religiões, 2021.

- BRASIL,2020. DECRETO Nº 10.292, DE 25 DE MARÇO DE 2020. Altera o Decreto nº 10.282, de 20 de março de 2020, que regulamenta a Lei nº 13.979, de 6 de fevereiro de 2020, para definir os serviços públicos e as atividades essenciais. Available: https://www2.camara.leg.br/legin/fed/decret/2020/decreto-10292-25-marco-2020-789872-publicacaooriginal-160178-pe.html.

- Atchison, C., Bowman, L.R., Vrinten, C., Redd, R., Pristerà, P., Eaton, J., Ward H. Early perceptions and behavioural responses during the COVID-19 pandemic: a cross-sectional survey of UK adults. BMJ Open. 2021 Jan 4;11(1):e 043577. PMID: 33397669; PMCID: PMC7783373. [CrossRef]

- Étard, J-F., Vanhems, P., Atlani-Duault, L., Ecochard R. Potential lethal outbreak of coronavirus disease (COVID-19) among the elderly in nursing homes and long-term facilities, France, 2020 March. , 2020;25(15):pii=2000448. [CrossRef]

- Szwarcwald, C. L. et al. ConVid - Behavior Survey by the Internet during the COVID-19 pandemic in Brazil: Conception and application methodology. Cad. Saude Publica 37, e00268320 (2021).

- Faleiros, F. et al. Use of virtual questionnaire and dissemination as a data collection strategy in scientific studies. Texto & Contexto - Enfermagem [online]. 2016, v. 25, n. 04 [Accessed August 11 2022], e3880014. Available: <https://doi.org/10.1590/0104-07072016003880014>. Epub 2016 Out 24 . ISSN 1980-265X. [CrossRef]

- Bazán, P. R. et al. COVID-19 information exposure in digital media and implications for employees in the health care sector: findings from an online survey. Einstein Sao Paulo Braz. 18, eAO6127 (2020).

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).