Submitted:

06 March 2023

Posted:

06 March 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. Self-regulation in Online Learning at Higher Education

1.2. Peer Collaboration and Digital Communication

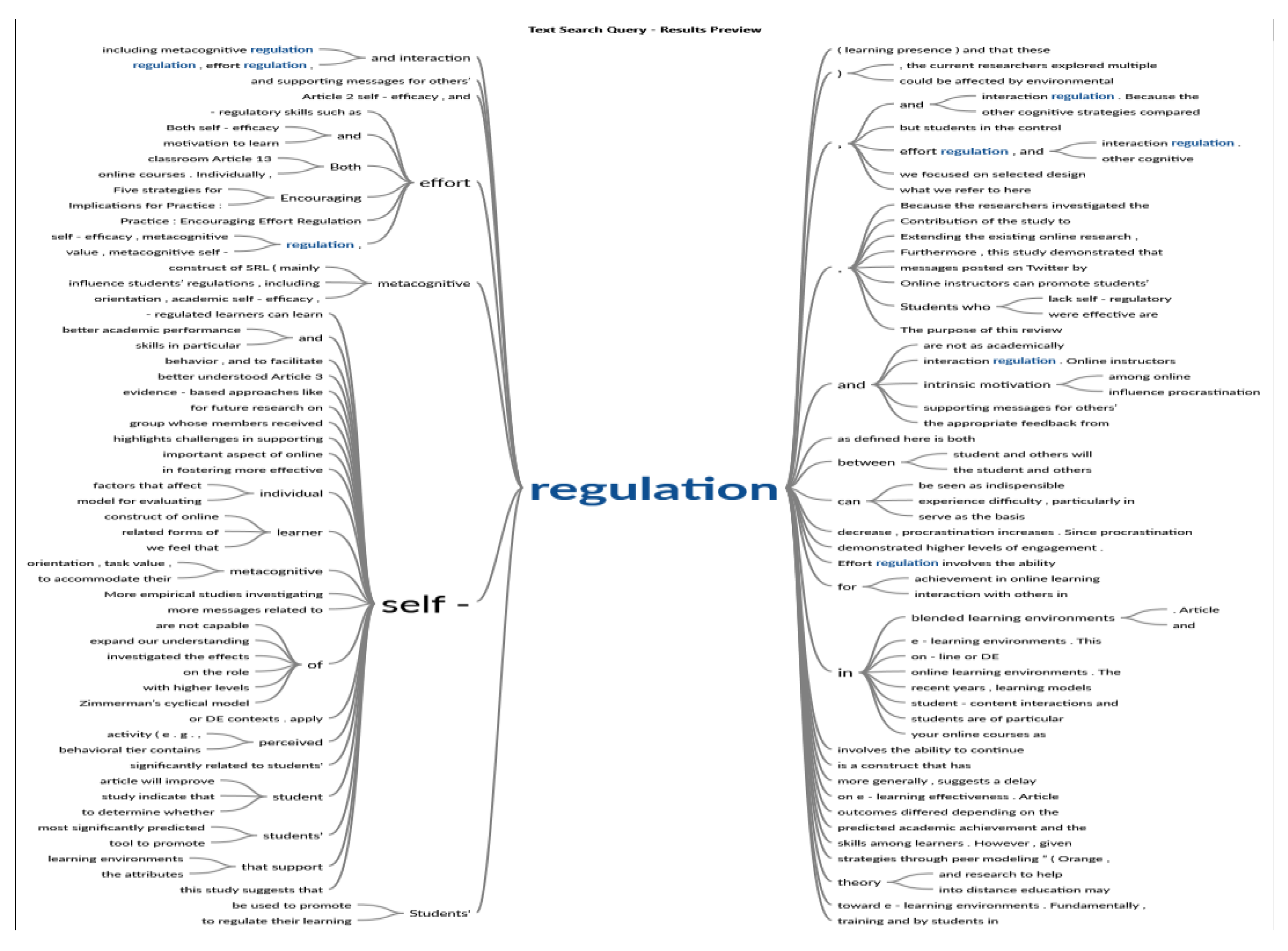

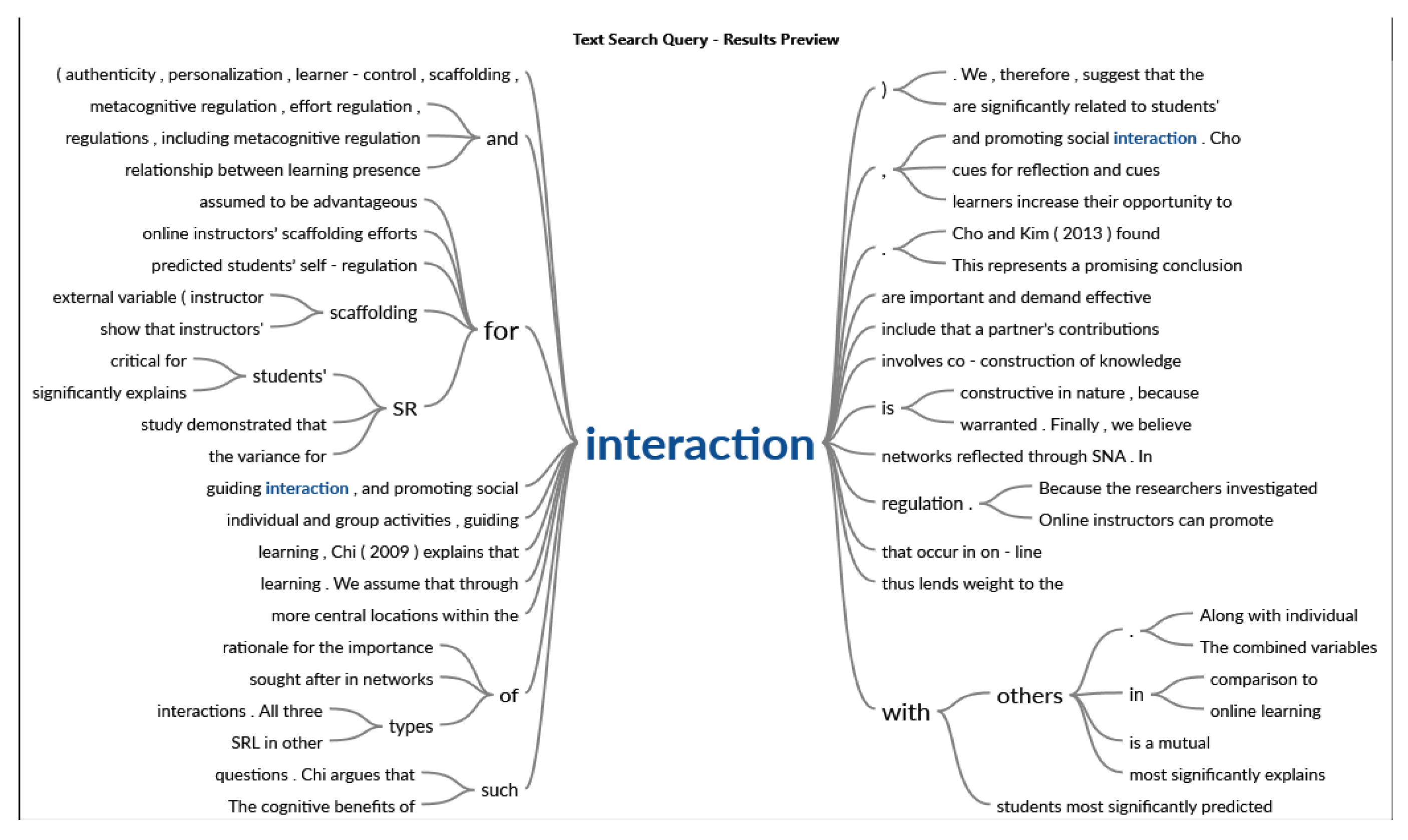

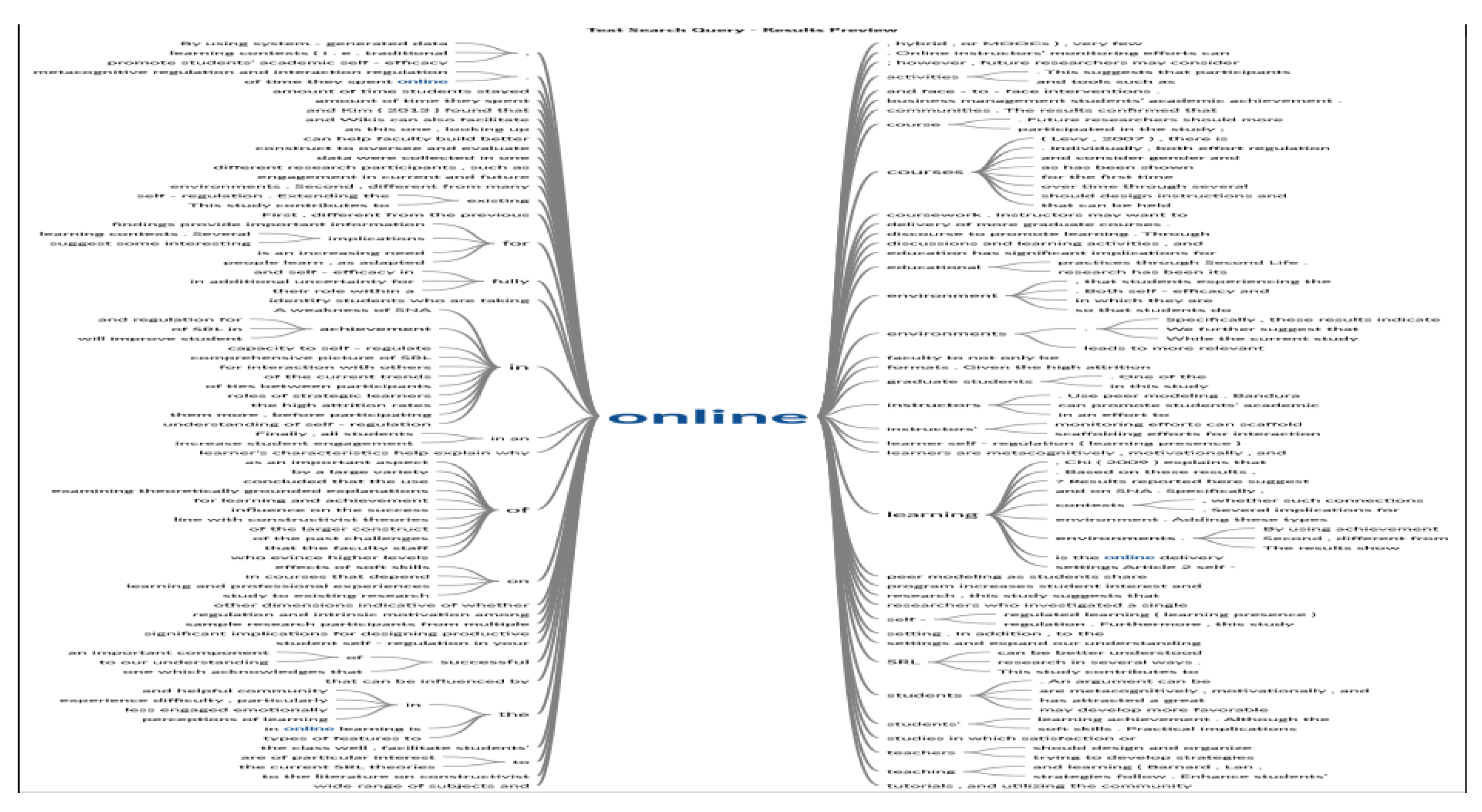

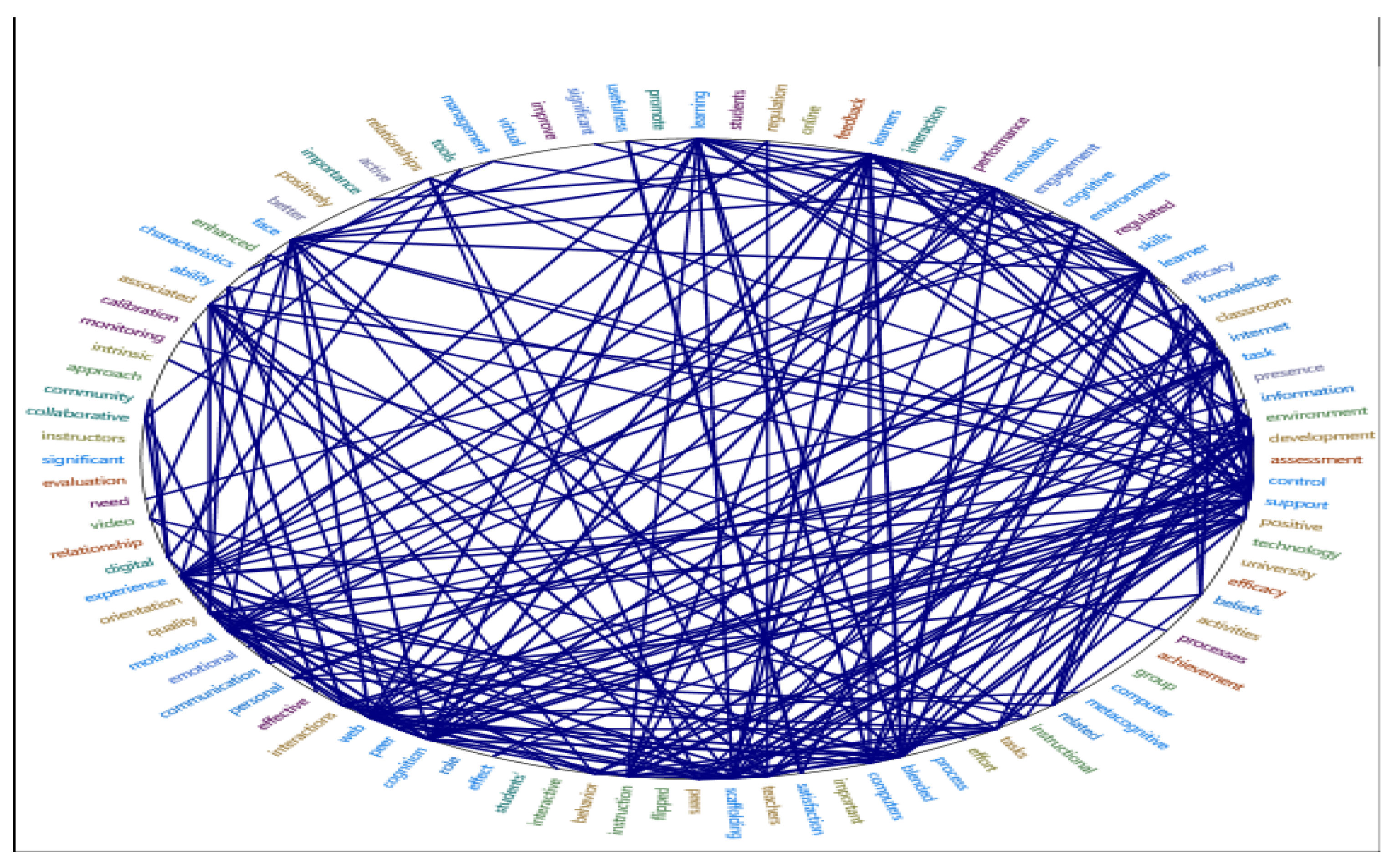

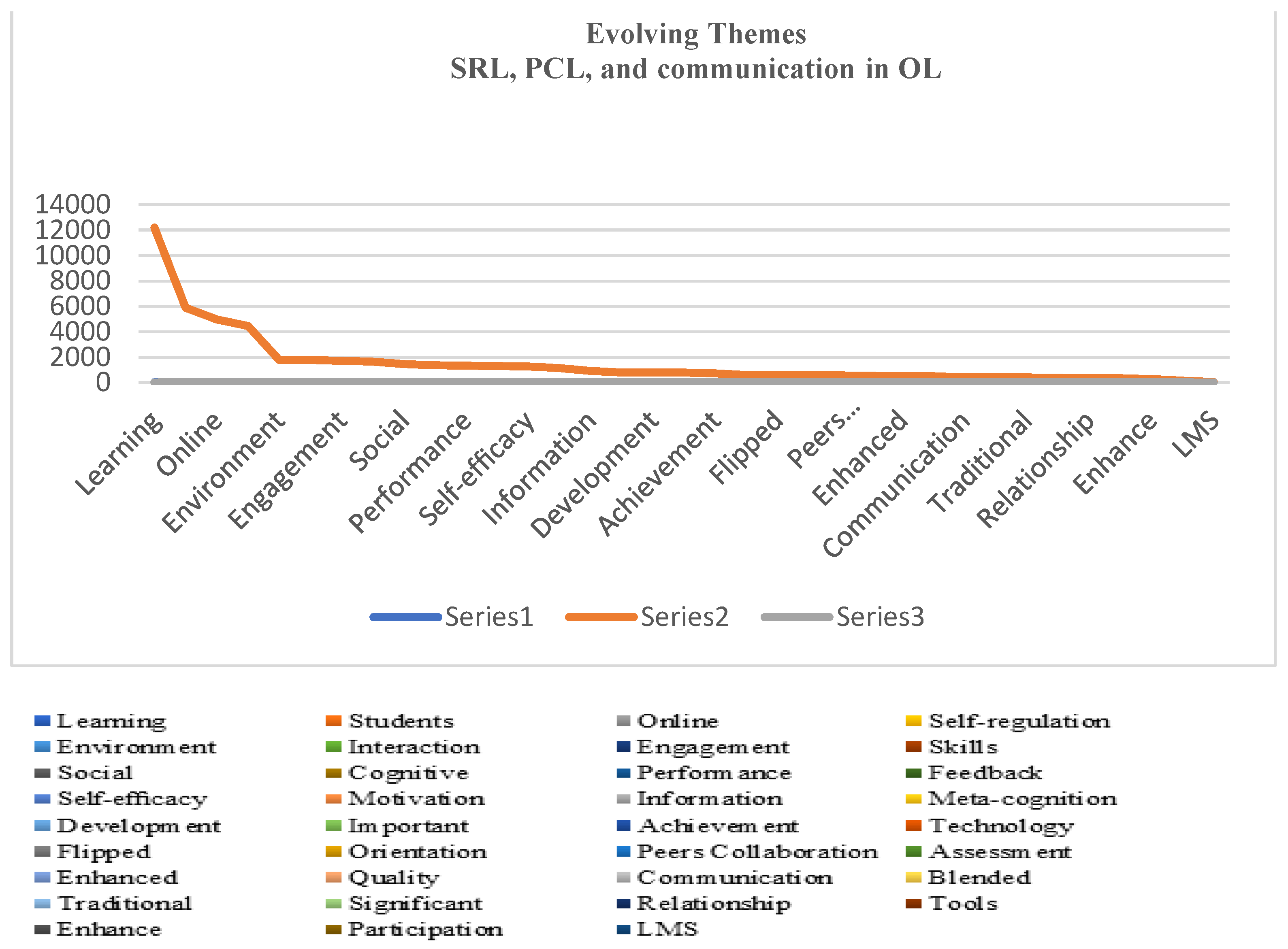

2. Results

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

| Data Source | Crossref | Open Alex | Google Scholar | Scopus | PubMed | Semantic Scholar |

| Search Date | 2022-12-11 | 2022-12-11 | 2022-12-11 | 2022-12-11 | 2022-12-11 | 2022-12-11 |

| Papers | 1000 | 8 | 998 | 1 | 84 | 1000 |

| Citations | 12429 | 320 | 65873 | 39 | 0 | 30365 |

| Citations/year | 1035.75 | 29.09 | 5489.42 | 6.50 | 0 | 660.1 |

| Cite/paper | 12.4 | 40.00 | 66.01 | 39.00 | 0.00 | 30.3 |

| Authors/paper | x̄=1.85 | x̄=2.63 | x̄=2.63 | x̄=1.00 | x̄=3.81 | x̄=2.75 |

| High Index & citation % | 52,64.8% | 7, 99.1% | 130,65.0% | 1, 100.0% | 0,0% | 82, 52.3% |

| Annual-H Index Pop | 3.17 | 0.55 | 6.75 | 0.17 | 0.00 | 1.39 |

5. Conclusions

References

- L. Breslow, D. Pritchard, J. DeBoer, … G. S.-R. & P. in, and undefined 2013, “Studying learning in the worldwide classroom research into edX’s first MOOC.,” ERIC, Accessed: Feb. 14, 2023. [Online]. Available: https://eric.ed.gov/?id=ej1062850.

- K. J.-I. R. of R. in O. and undefined 2014, “Initial trends in enrolment and completion of massive open online courses,” erudit.org, vol. 15, no. 1, pp. 133–160, 2014. [CrossRef]

- M. S. Al-Hawamleh, A. F. Alazemi, D. A. H. Al-Jamal, S. al Shdaifat, and Z. Rezaei Gashti, “Online Learning and Self-Regulation Strategies: Learning Guides Matter,” Educ Res Int, vol. 2022, 2022. [CrossRef]

- J. Wong et al., “Supporting self-regulated learning in online learning environments and MOOCs: A systematic review,” Taylor & Francis, vol. 35, no. 4–5, pp. 356–373, Mar. 2018. [CrossRef]

- J. S. Barrot, I. I. Llenares, and L. S. del Rosario, “Students’ online learning challenges during the pandemic and how they cope with them: The case of the Philippines,” Educ Inf Technol (Dordr), vol. 26, no. 6, pp. 7321–7338, Nov. 2021. [CrossRef]

- K. M. Hamdan, A. M. Al-Bashaireh, Z. Zahran, A. Al-Daghestani, S. AL-Habashneh, and A. M. Shaheen, “University students’ interaction, Internet self-efficacy, self-regulation and satisfaction with online education during pandemic crises of COVID-19 (SARS-CoV-2),” International Journal of Educational Management, vol. 35, no. 3, pp. 713–725, 2021. [CrossRef]

- M. V. J. Veenman, “Alternative assessment of strategy use with self-report instruments: A discussion,” Metacogn Learn, vol. 6, no. 2, pp. 205–211, Aug. 2011. [CrossRef]

- H. de Boer, A. S. Donker-Bergstra, and D. D. N. M. Kostons, Effective Strategies for Self-regulated Learning: A Meta-analysis. 2012. Accessed: Feb. 14, 2023. [Online]. Available: https://www.nro.nl/sites/nro/files/migrate/PROO_Effective%252Bstrategies%252Bfor%252Bself-regulated%252Blearning.pdf.

- J. Wong, M. Baars, D. Davis, T. van der Zee, G. J. Houben, and F. Paas, “Supporting Self-Regulated Learning in Online Learning Environments and MOOCs: A Systematic Review,” vol. 35, no. 4–5, pp. 356–373, Mar. 2018. [CrossRef]

- R. A. Carter, M. Rice, S. Yang, and H. A. Jackson, “Self-regulated learning in online learning environments: strategies for remote learning,” Information and Learning Science, vol. 121, no. 5–6, pp. 311–319, Jul. 2020. [CrossRef]

- Y. M. Byrnes, A. M. Civantos, B. C. Go, T. L. McWilliams, and K. Rajasekaran, “Effect of the COVID-19 pandemic on medical student career perceptions: a national survey study,” Med Educ Online, vol. 25, no. 1, Jan. 2020. [CrossRef]

- H. Khiat, “Using automated time management enablers to improve self-regulated learning,” vol. 23, no. 1, pp. 3–15, Jul. 2019. [CrossRef]

- E. K. AGORMEDAH, E. ADU HENAKU, D. M. K. AYİTE, and E. APORİ ANSAH, “Online Learning in Higher Education during COVID-19 Pandemic: A case of Ghana,” Journal of Educational Technology and Online Learning, Sep. 2020. [CrossRef]

- H. Baber, “Social interaction and effectiveness of the online learning – A moderating role of maintaining social distance during the pandemic COVID-19,” Asian Education and Development Studies, vol. 11, no. 1, pp. 159–171, Jan. 2022. [CrossRef]

- O. B. Adedoyin and E. Soykan, “Covid-19 pandemic and online learning: the challenges and opportunities,” Interactive Learning Environments, 2020. [CrossRef]

- M. Håkansson Lindqvist and F. Pettersson, “Digitalization and school leadership: on the complexity of leading for digitalization in school,” International Journal of Information and Learning Technology, vol. 36, no. 3, pp. 218–230, May 2019. [CrossRef]

- F. Pettersson, “Understanding digitalization and educational change in school by means of activity theory and the levels of learning concept,” Educ Inf Technol (Dordr), vol. 26, no. 1, pp. 187–204, Jan. 2021. [CrossRef]

- S. Babacan and S. Dogru Yuvarlakbas, “Digitalization in education during the COVID-19 pandemic: emergency distance anatomy education,” Surgical and Radiologic Anatomy, vol. 44, no. 1, pp. 55–60, Jan. 2022. [CrossRef]

- O. Z.-H. B. and Emerging and undefined 2021, “The current state and impact of Covid-19 on digital higher education in Germany,” Wiley Online Library, vol. 3, no. 1, pp. 218–226, Jan. 2020. [CrossRef]

- S. J. Daniel, “Education and the COVID-19 pandemic,” Prospects (Paris), vol. 49, no. 1–2, pp. 91–96, Oct. 2020. [CrossRef]

- R. Chick, G. Clifton, K. Peace, … B. P.-J. of surgical, and undefined 2020, “Using technology to maintain the education of residents during the COVID-19 pandemic,” Elsevier, Accessed: Feb. 14, 2023. [Online]. Available: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1931720420300842.

- B. J. Zimmerman, “Attaining Self-Regulation: A Social Cognitive Perspective,” Handbook of Self-Regulation, pp. 13–39, Jan. 2000. [CrossRef]

- B. Zimmerman, “Achieving Self-Regulation: The Trial and Triumph of Adolescence.,” 2002, Accessed: Feb. 14, 2023. [Online]. Available: https://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED471681.

- J. Lim and T. J. Newby, “Preservice teachers’ attitudes toward Web 2.0 personal learning environments (PLEs): Considering the impact of self-regulation and digital literacy,” Educ Inf Technol (Dordr), vol. 26, no. 4, pp. 3699–3720, Jul. 2021. [CrossRef]

- D. A. P. Pérez and M. C. C. Torres, “Virtual Learning Checkpoints: Autonomy and Motivation Boosters in the English Flipped Classroom,” pp. 325–334, 2022. [CrossRef]

- S. Hosseini, D. H. Peluffo, J. Nganji, and A. Arrona-Palacios, Eds., “Technology-Enabled Innovations in Education,” 2022. [CrossRef]

- G. Tur, L. Castañeda, R. Torres-Kompen, and J. P. Carpenter, “A literature review on self-regulated learning and personal learning environments: features of a close relationship,” 2022. [CrossRef]

- P. van Hardenberg, M. K.-P. of the 7th W. on, and undefined 2020, “PushPin: Towards production-quality peer-to-peer collaboration,” dl.acm.org, Apr. 2020. [CrossRef]

- J. Leighton, T. Kurta, … S. D.-: A. J. of L. S. and, and undefined 2021, “Creating Inter-Learning Connections: Opportunities for Peer Collaboration among Leisure Students,” Taylor & Francis, 2021. [CrossRef]

- G. Jayathirtha, D. Fields, Y. B. Kafai, and J. Chipps, “Supporting making online: the role of artifact, teacher and peer interactions in crafting electronic textiles,” Information and Learning Science, vol. 121, no. 5–6, pp. 371–380, Jul. 2020. [CrossRef]

- D. Vlachopoulos and A. Makri, “Online communication and interaction in distance higher education: A framework study of good practice,” International Review of Education, vol. 65, no. 4, pp. 605–632, Aug. 2019. [CrossRef]

- M. Pazmiño-Sarango, M. Naranjo-Zolotov, and F. Cruz-Jesus, “Assessing the drivers of the regional digital divide and their impact on eGovernment services: evidence from a South American country,” Information Technology and People, vol. 35, no. 7, pp. 2002–2025, Dec. 2022. [CrossRef]

- Y. Shi, P. L. Prieto, T. Zepel, S. Grunert, and J. E. Hein, “Automated Experimentation Powers Data Science in Chemistry,” Acc Chem Res, vol. 54, no. 3, pp. 546–555, Feb. 2021. [CrossRef]

- R. Pérez-López, R. Gurrea-Sarasa, C. Herrando, J. Martín-De Hoyos, V. Bordonaba-Juste, and A. U. Acerete, “The generation of student engagement as a cognition-affect-behaviour process in a Twitter learning experience,” ajet.org.au, vol. 2020, no. 3, p. 36, Accessed: Feb. 15, 2023. [Online]. Available: https://ajet.org.au/index.php/AJET/article/view/5751.

- C. Assessing Cognitive, Y.-T. Jou, K. Allen Mariñas, and C. Sheena Saflor, “Assessing Cognitive Factors of Modular Distance Learning of K-12 Students Amidst the COVID-19 Pandemic towards Academic Achievements and Satisfaction,” mdpi.com, 2022. [CrossRef]

- N. C. DiDonato, “Effective self- and co-regulation in collaborative learning groups: An analysis of how students regulate problem solving of authentic interdisciplinary tasks,” Instr Sci, vol. 41, no. 1, pp. 25–47, Jan. 2013. [CrossRef]

- F. S. Kia, M. Hatala, … R. B.-… I. L., and undefined 2021, “Measuring students’ self-regulatory phases in LMS with behavior and real-time self report,” dl.acm.org, pp. 259–268, Apr. 2021. [CrossRef]

- A. B. Ustun, K. Zhang, F. G. Karaoğlan-Yilmaz, and R. Yilmaz, “Learning analytics based feedback and recommendations in flipped classrooms: an experimental study in higher education,” Journal of Research on Technology in Education, 2022. [CrossRef]

- L. Schnaubert and D. Bodemer, “Group awareness and regulation in computer-supported collaborative learning,” Int J Comput Support Collab Learn, vol. 17, no. 1, pp. 11–38, Mar. 2022. [CrossRef]

- L. Zheng, J. Niu, L. Zhong, and J. F. Gyasi, “Knowledge-building and metacognition matter: Detecting differences between high- and low-performance groups in computer-supported collaborative learning,” Innovations in Education and Teaching International, 2021. [CrossRef]

- C. Schoor, S. Narciss, H. K.-E. Psychologist, and undefined 2015, “Regulation during cooperative and collaborative learning: A theory-based review of terms and concepts,” Taylor & Francis, vol. 50, no. 2, pp. 97–119, Apr. 2015. [CrossRef]

- S. Järvelä, A. Hadwin, J. Malmberg, and M. Miller, “Contemporary Perspectives of Regulated Learning in Collaboration,” International Handbook of the Learning Sciences, pp. 127–136, Feb. 2019. [CrossRef]

- L. de Backer, H. van Keer, F. de Smedt, E. Merchie, and M. Valcke, “Identifying regulation profiles during computer-supported collaborative learning and examining their relation with students’ performance, motivation, and self-efficacy for learning,” Comput Educ, vol. 179, p. 104421, Apr. 2022. [CrossRef]

- L. de Backer, H. van Keer, F. de Smedt, … E. M.-C. &, and undefined 2022, “Identifying regulation profiles during computer-supported collaborative learning and examining their relation with students’ performance, motivation, and self-efficacy,” Elsevier, Accessed: Feb. 15, 2023. [Online]. Available: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0360131521002980.

- L. de Backer, H. van Keer, M. V.-I. J. of Educational, and undefined 2021, “Examining the relation between students’ active engagement in shared metacognitive regulation and individual learner characteristics,” Elsevier, Accessed: Feb. 15, 2023. [Online]. Available: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0883035521001610.

- “Publish or Perish.” https://harzing.com/resources/publish-or-perish (accessed Feb. 15, 2023).

- R. A.-B. J. of G. Practice and undefined 2017, “Word cloud analysis of the BJGP: 5 years on,” bjgp.org. [CrossRef]

- C. Silver and A. Lewins, Using software in qualitative research: A step-by-step guide. 2014. Accessed: Feb. 15, 2023. [Online]. Available: https://books.google.com/books?hl=en&lr=&id=hfKICwAAQBAJ&oi=fnd&pg=PP1&dq=Silver,+C.,+%26+Lewins,+A.+(2014).+Using+software+in+qualitative+research:+A+step-bystep+guide.+Sage&ots=echd2rG-Sg&sig=WYsOqcwLBkoqJTkQ58wCnf8ADqU.

- M. Inzlicht, K. M. Werner, J. L. Briskin, and B. W. Roberts, “Integrating Models of Self-Regulation,” Annu Rev Psychol, vol. 72, pp. 319–345, Jan. 2021. [CrossRef]

- M. Boekaerts, L. C.-A. psychology, and undefined 2005, “Self-regulation in the classroom: A perspective on assessment and intervention,” Wiley Online Library, vol. 54, no. 2, pp. 199–231, Apr. 2005. [CrossRef]

- M. Weiss, K. K.-R. Q. for E. and Sport, and undefined 1987, “‘Show and tell’ in the gymnasium: An investigation of developmental differences in modeling and verbal rehearsal of motor skills,” Taylor & Francis, Accessed: Feb. 15, 2023. [Online]. Available: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/02701367.1987.10605455.

- B. J. Schmeichel and A. Zell, “Trait Self-Control Predicts Performance on Behavioral Tests of Self-Control,” J Pers, vol. 75, no. 4, pp. 743–756, Aug. 2007. [CrossRef]

- K. Zahrai, E. Veer, P. W. Ballantine, and H. Peter de Vries, “Conceptualizing Self-control on Problematic Social Media Use,” Australasian Marketing Journal, vol. 30, no. 1, pp. 74–89, Feb. 2022. [CrossRef]

- D. Akamatsu, M. Nakaya, R. K.-B. Sciences, and undefined 2019, “Effects of metacognitive strategies on the self-regulated learning process: The mediating effects of self-efficacy,” mdpi.com, 2019. [CrossRef]

- B. Zimmerman and D. Schunk, Handbook of self-regulation of learning and performance. 2011. Accessed: Feb. 15, 2023. [Online]. Available: https://psycnet.apa.org/record/2011-12365-000.

- P. P.-H. of self-regulation and undefined 2000, “The role of goal orientation in self-regulated learning,” Elsevier, Accessed: Feb. 15, 2023. [Online]. Available: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/B9780121098902500433.

- N. Zakiah, D. F.-J. of P. C. Series, and undefined 2020, “Self regulated learning for social cognitive perspective in mathematics lessons,” iopscience.iop.org. [CrossRef]

- M. F. Zalazar-Jaime and L. A. Medrano, “An Integrative Model of Self-Regulated Learning for University Students: The Contributions of Social Cognitive Theory of Carriers,” Journal of Education, vol. 201, no. 2, pp. 126–138, Apr. 2021. [CrossRef]

- M. Odinokaya, T. Krepkaia, I. Karpovich, T. I.-E. sciences, and undefined 2019, “Self-regulation as a basic element of the professional culture of engineers,” mdpi.com. [CrossRef]

- T. Ulfatun, F. Septiyanti, A. L.-I. and E. Technology, and undefined 2021, “University students’ online learning self-efficacy and self-regulated learning during the COVID-19 pandemic,” ijiet.org. [CrossRef]

- S. S. Oyelere, S. A. Olaleye, O. S. Balogun, and Ł. Tomczyk, “Do teamwork experience and self-regulated learning determine the performance of students in an online educational technology course?,” Educ Inf Technol (Dordr), vol. 26, no. 5, pp. 5311–5335, Sep. 2021. [CrossRef]

- S. Paris, A. P.-E. psychologist, and undefined 2003, “Classroom applications of research on self-regulated learning,” taylorfrancis.com, vol. 36, no. 2, pp. 89–101, 2001. [CrossRef]

- E. Handoko, S. Gronseth, S. McNeil, C. B.-… D. Learning, and undefined 2019, “Goal setting and MOOC completion: A study on the role of self-regulated learning in student performance in massive open online courses,” erudit.org, vol. 20, no. 3, 2019. [CrossRef]

- M. B.-T. L. Teacher and undefined 2013, “Self-regulated learning: Goal setting and self-monitoring,” jalt-publications.org, Accessed: Feb. 15, 2023. [Online]. Available: http://jalt-publications.org/files/pdf-article/37.4tlt_art2.pdf.

- A. B.-P. selection and classification and undefined 2013, “Regulative function of perceived self-efficacy,” taylorfrancis.com, Accessed: Feb. 15, 2023. [Online]. Available: https://www.taylorfrancis.com/chapters/edit/10.4324/9780203773918-22/regulative-function-perceived-self-efficacy-albert-bandura-261.

- D. Cervone, “The Role of Self-Referent Cognitions in Goal Setting, Motivation, and Performance,” Cognitive Science Foundations of Instruction, pp. 57–96, Apr. 2020. [CrossRef]

- E. Panadero, “A review of self-regulated learning: Six models and four directions for research,” Front Psychol, vol. 8, no. APR, 2017. [CrossRef]

- D. Bylieva, J. C. Hong, V. Lobatyuk, and T. Nam, “Self-regulation in e-learning environment,” Educ Sci (Basel), vol. 11, no. 12, Dec. 2021. [CrossRef]

- O. Sadi, M. U.-J. of B. S. Education, and undefined 2013, “The relationship between self-efficacy, self-regulated learning strategies and achievement: A path model,” search.proquest.com, Accessed: Feb. 15, 2023. [Online]. Available: https://search.proquest.com/openview/951e194932ea4673217f3933fed8f77b/1?pq-origsite=gscholar&cbl=4477238.

- P. Shea, T. B.-C. & education, and undefined 2010, “Learning presence: Towards a theory of self-efficacy, self-regulation, and the development of a communities of inquiry in online and blended learning environments,” Elsevier, Accessed: Feb. 15, 2023. [Online]. Available: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0360131510002095.

- J. Broadbent, W. P.-T. internet and higher education, and undefined 2015, “Self-regulated learning strategies & academic achievement in online higher education learning environments: A systematic review,” Elsevier, vol. 27, pp. 1–13, 2015. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).