Introduction

The Covid-19 pandemic changed the life of a large part of the population worldwide. Although the hardest times of the pandemic have passed, we continue to face medium- and long-term complications and consequences on public health, the economy, and society (1). The most important long-term consequences of the pandemic seem to be related with its psychological impact (2).

It is known that Covid-19 quarantine caused important changes in children's routines, especially in terms of nutrition, physical activity, screen time, social activity, and school time (3). Regarding these changes, recent studies show that Covid-19 lockdown was also associated with higher levels of anxiety and depression in children (3, 4).

Confinement conditions can lead to forced inactivity and an increase in sedentary behavior, which is known to be associated with higher risk of physical and psychological adverse conditions such as obesity, muscle atrophy, cardiovascular vulnerability (5), anxiety and depression (6). Besides, fear of becoming infected and a hostile environment brought on by lockdown have been linked to higher levels of anxiety and depression (7) which are related to quantity and quality of sleep.

Getting a good night's sleep is necessary for correct growth and development in childhood and adolescence. Poor sleep or insufficient sleep may affect concentration, memory, and behavior (8). One study with Italian children showed that irritability and sleep disorders were the most frequent problems referred to by children and adolescents during lockdown (4). These sleeping problems included insomnias, difficulty falling asleep and waking up, and night awakenings.

Adolescence is a critical period in which many physical, psychological, and socio-cognitive changes occur that may have long-term implications on health and wellbeing. Adolescents seem to be the most vulnerable to develop sleep problems during confinement. Many studies reported significant changes in subjective wellbeing and an increase in anxiety symptoms in adolescents during lockdown (8, 9). One study carried out in the United States found an increase in the relative mean number of searches for information about suicide, mental health, and financial problems on the Internet (10).

The psychological consequences of the Covid-19 pandemic and lockdown should not be depreciated. The dramatic changes in lifestyle derived from this pandemic generated a real threat to mental health because it raised symptoms in previously healthy persons and it exacerbated symptoms in people with latent disorders. These consequences must be known and studied to adequately treat current patients and to develop preventive strategies to be implemented in the event of similar catastrophes.

Spain was one of the most affected country by the pandemic in Europe, and its lockdown conditions were among the most restrictive ones. On March 14th, 2020, the Spanish Government declared the state of alarm and established a lockdown (RD463/2020) that lasted almost 50 days (until the 2nd of May 2020) and was followed by four phases of de-escalation. During that period, only health care professionals and people in essential services could leave their homes. The rest of the citizens, including children, could only go out to buy food and basic supplies, but not for a walk or working out. The state of alarm and lockdown ended on June 21st, 2020. The main objective of this study was to assess changes in sleep quality of Spanish children during the COVID19.

Methodology

Study Aim, Design and Setting

The SENDO project (“Seguimiento del Niño para un Desarrollo Óptimo” [Child Follow-up for Optimal Development];

www.proyectosendo.es) is a multipurpose, ongoing, prospective pediatric cohort focused on studying the effect of diet and lifestyle on children and adolescent health. Participants are invited to enter the cohort by their pediatrician at their primary care health center or by the research team at school. Recruitment started in 2015 and it is permanently open and inclusion criteria are: 1) age between 4 and 5 years and 2) residence in Spain. The only exclusion criterion is lack of access to an internet-connected device to complete the questionnaires. Further information on this cohort study design has previously been reported in detail elsewhere (11).

Information is collected at baseline and updated every year through online self-administered questionnaires completed by parents. In September 2020 an additional brief questionnaire was sent to participants to collect information on lifestyle changes experienced during the Spanish lockdown between March and June 2020. Answers were collected until December 31st, 2020.

Participants

Among the 832 participants recruited before September 2020, 485 completed the additional questionnaire regarding changes in lifestyle during lockdown (participation proportion: 58%). Participants with missing information in four or more questions regarding sleeping quality were excluded from the analysis (n:7). Participants with fewer missing items were contacted to complete the information. The final sample consisted of 478 participants.

Assessment of the outcome and covariates:

The baseline questionnaire of the SENDO project collects information on sociodemographic, lifestyle and diet-related variables. The information referred to lockdown was collected through a brief additional questionnaire between September and December 2020. This questionnaire included questions related to changes in sleeping habits, dietary habits, physical activities, and sedentary time.

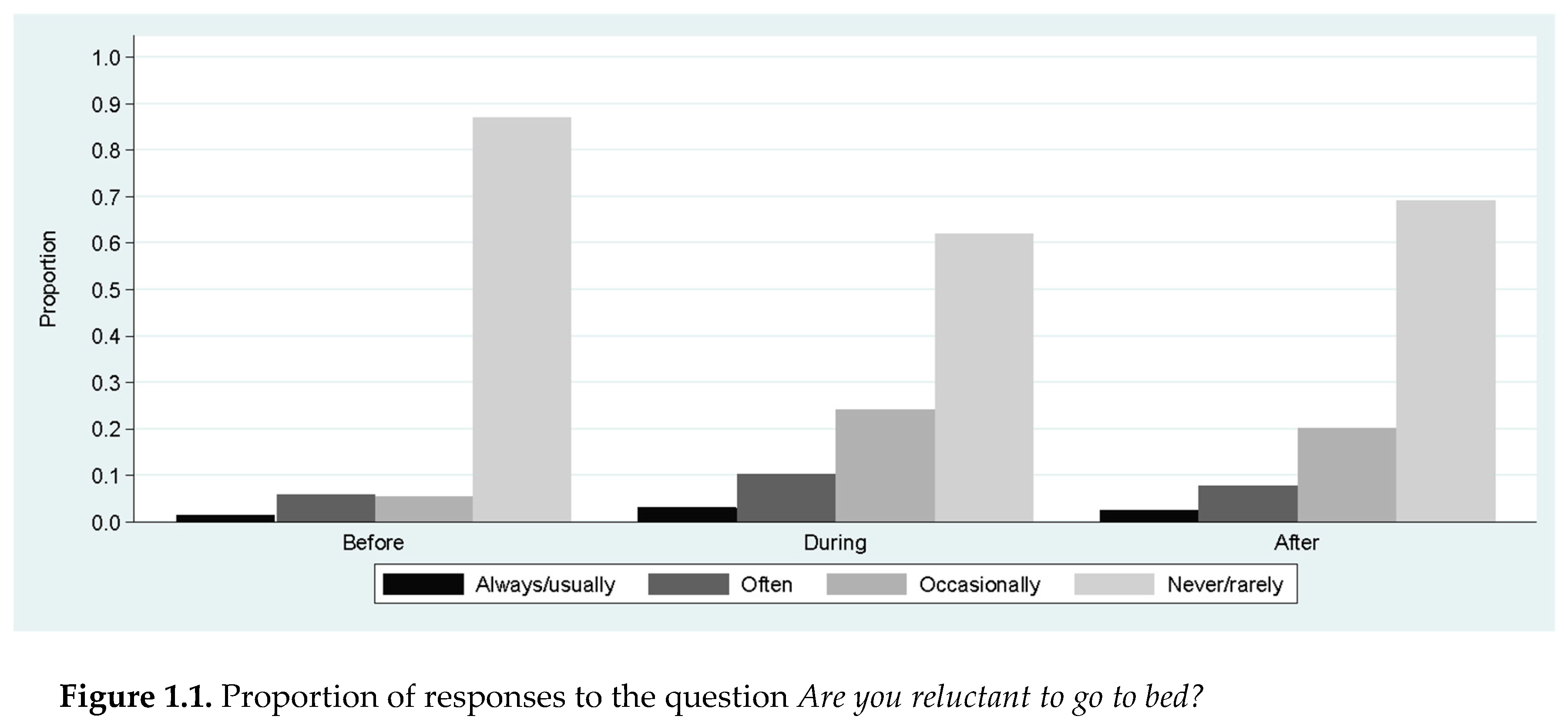

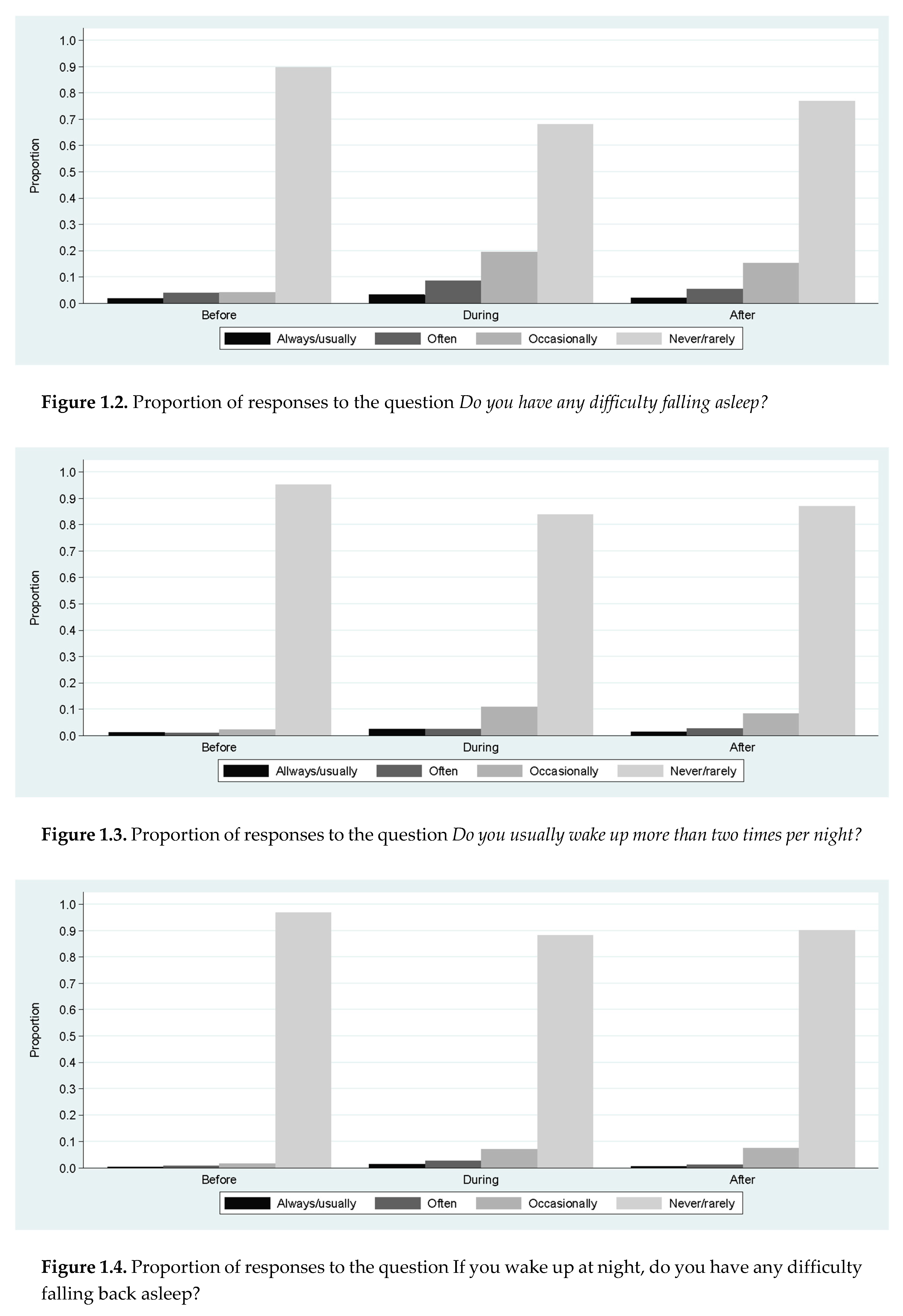

Sleep habits were assessed with the BEAR questionnaire, one of the most used tools to identify sleep problems in children, that has already been validated in Spain (12, 13, 14, 15). It is a user-friendly screening tool that helps identify sleeping problems in children and includes the questions: 1) Are you reluctant to go to bed?, 2) Do you have any difficulty falling asleep?, 3) Do you usually wake up more than two times per night?, 4) If you wake up at night, do you have any difficulty falling back asleep? We assigned points to each answer as follows: always/very often (3 points), often (2 points), occasionally (1 point) or almost never/never (0 points). Each participant completed the BEAR questionnaire thrice (including information for periods before, during and after lockdown). We calculated the total score in each questionnaire adding the punctuation in the four questions. Final scores ranged between 0 and 12 points, with higher scores meaning more sleeping problems. We obtained three total scores in the BEAR questionnaire for each participant referred to periods before, during and after lockdown. For descriptive purposes, participants were divided into two groups based on their basal score on the BEAR questionnaire referred to the period before lockdown (0 vs. ≥1 point).

Statistical Analysis

Participant characteristics are described by basal BEAR score (BEAR score before lockdown 0 vs ≥1). We used mean values and standard deviations for quantitative variables and used percentages for categorical ones. Between-groups comparisons were made using Student t-test for quantitative variables and χ2 tests for qualitative ones.

We compared scores on the BEAR questionnaire referred to the three periods (before, during and after lockdown) using repeated measures for each participant. We used hierarchical models with two levels of clustering to account for the intra-cluster correlation between siblings. In further analyses participants were divided into two groups depending on parental educational level (university graduates or above).

Interaction between time and a-priori selected variables (i.e. sex, number of siblings, number of cohabitants, parental education, having a pet, having a mobile phone, physical activity (METS), BMI (kg/m2), moderate or intense activity (hours/week) and adherence to the Mediterranean diet) was assessed by introducing the interaction term into the model and calculating a likelihood ratio test.

Analyses were carried out using the software STATA 15.0. (Stata Corporation, College Station, TX, USA). All p-values were two-tails. Statistical significance was determined at the conventional cut-off point of p < 0.05.

Ethical considerations

The SENDO project follows the rules of the Declaration of Helsinki on the ethical principles for medical research in human beings. This study was approved by the Ethics Committee for Clinical Research of Navarra (Pyto 2016/122). Informed consent was obtained from all participants’ parents at recruitment.

Results

This study includes 479 participants (226 girls) with a mean age of 7.5 years (sd: 1.8). 371 children scored 0 points in the basal BEAR questionnaire (period before lockdown), meaning they did not present any previous sleeping disorder. The mean score on the basal BEAR questionnaire in patients with previous sleeping disorders was 0.52 (sd: 1.24). The mean sleep time before the confinement was 9.2 hours (sd: 0.44).

Basal characteristics of participants by basal BEAR questionnaire are shown in

Table 1. We observed no differences between groups in sociodemographic and lifestyle characteristics of children nor in their family characteristics.

Figure 1 shows the responses to each question in the BEAR questionnaire. For each question, the percentage of responses before, during and after lockdown were represented. The most frequent category of response in all the questions was “almost never/never” either before, during or after lockdown. However, the proportion of participants who answered “never/almost never” decreased during lockdown and increased after it without reaching the initial level.

Mean scores in the BEAR questionnaire referred to the periods before, during and after lockdown were 0.52 (sd 1.25), 1.43 (sd 1.99) and 1.07 (sd 1.55) respectively (

Table 2). Children with previous sleeping disorders (≥1 points in the basal BEAR questionnaire) had significantly higher mean scores in the BEAR questionnaires during (3.11 vs. 0.94 points) and after (2.74 vs.0.59 points) lockdown. We found that the mean score in the BEAR questionnaire significantly increased during lockdown and significantly decreased after it. However, it did not reach the initial level and the mean score in the BEAR questionnaire referred to the period after lockdown was significantly higher than before. That trend was observed in the whole sample and in each group.

Additionally, mean leisure screen time of participants was 1.13 hours/day (sd: 0.81) before the lockdown and 2.65 hours/day (sd: 1.69) during it (p<0.001). Mean time of moderate or vigorous physical activity was 1.27 hours/day (sd: 0.99) before the lockdown and 0.79 hours/day (sd: 0.96) during (p<0.001).

Parental level of education was found to be an effect modifier (p for interaction=0.004). Although similar trends in the mean score were observed in both groups (an increase in the mean score during lockdown and a decrease after it), children whose parents had higher education (university graduate or higher) showed a smaller increase in the comparison before vs. during lockdown (0.86 vs. 1.17 points) and a higher decrease in the comparison during vs. after it (0.38 vs. 0.2 points). Children whose parents did not have high education did not present a significant improvement in sleep quality after the lock down according to their mean score in the BEAR questionnaire (1.75 vs. 1.55 points) (

Table 3). The comparison of mean scores in the questionnaire before lockdown showed no difference between group. However, children whose parents did not have higher education showed significant higher mean scores in the questionnaire referred to both the period during (difference = 0.38 points) and after (difference = 0.56 points) lockdown (

Table 3).

Discussion

In this study of 479 children from the SENDO project, we found that the lockdown decreed in Spain between March and June 2020 as consequence of the Covid-19 pandemic was associated with a significant worsening of sleep quality, especially in children whose parents did not have higher education. Furthermore, we found that although it improved after lockdown, the sleep quality did not achieve previous levels, suggesting the consequences of lockdown on sleep quality could have a long-term effect. The increase in anxiety disorders in children, together with the increase in screen time, that persisted after the end of the lock down, may explain the worsening of children's sleep quality. A study with 715 minors from the United Kingdom found that not only they took longer to fall asleep, but also that for every daily hour they spent in front of a screen, nighttime sleep was reduced by 26 minutes (6). A review of more than twenty previous studies and that included more than 125,000 minors pointed that children who used screens before going to sleep double the risk of having insufficient sleep time than those who did not probably because bright light suppresses the production of melatonin, the sleep-inducing hormone (7).

To our knowledge, this is the first study that shows a long-term impact from Covid-19 lockdown on children's quality of sleep. Our results highlight the importance of assessing sleep quality in children and developing preventive measures for future possible lockdowns. Our results agree with previously published articles reporting that Covid-19 pandemic has increased the levels of stress in children and their relatives (18). One cross-sectional study carried out in China with 53,730 participants found that more than 35% of participants developed psychological distress (19), and a similar study also performed in China with 1,304 participants showed that more than 50% presented negative emotional influence during the Covid-19 pandemic (20). Those finding are consistent with previous knowledge that suggested that long periods of social isolation negatively impact people’s psychological wellbeing (21) leading to depression, stress, and anxiety (22). We hypothesize that worsening of sleep quality in Spanish children observed in this study could be at least partially explained by an increase in children’s anxiety level.

Recent studies found that social isolation during the Covid-19 pandemic greatly reduced the level of physical activity in both male and female students (23, 24) which may have worsened their sleep quality. Physical activity can promote positive mood (25), help maintain a healthy weight, and establish self-esteem both in children and adolescents (26). Vigorous physical activity can significantly reduce adolescents´ stress, anxiety, and depression (27) and protect them from metabolic syndrome (28). The use of electronic devices has been associated with worse sleep quality (29, 30) and their use increased during the lockdown (31).

We found that parental education was an effect modifier. In our study children whose parents had a low or middle level of education showed a greater worsening of sleep quality. This finding is not surprising considering recent publications that showed that Covid-19 lockdown had an important impact on parents and caregivers who developed high levels of anxiety, stress, and depression (32). That impact seemed to be greater in mothers (33), especially in those with lower levels of education or unemployed (34). Therefore, we hypothesize that children from parents with medium or low levels of education showed a greater deterioration of sleep quality either because the level of anxiety at their homes was higher or because those parents had fewer resources to help their children sleep.

The Covid-19 pandemic and subsequent lockdown led to an alarming increase in levels of anxiety, depression, irritability, boredom, inattention and sleeping problems in children (35). These consequences are not exclusive to a pandemic and can appear in the event of any other natural or man-made disaster. Public health strategies are needed to prevent this type of consequences through a multidisciplinary approach that helps children to better manage and control stress and anxiety (36).

Despite our results, this study had some limitations. Self-reported information is susceptible to misclassification bias. Since the SENDO project information is updated every year through online questionnaires, families are used to this method of data collection, which reduces the risk of systematic error. Participants in the SENDO project are mostly white children from medium to high-level educated families. Although this may hamper the generalizability of our results, it increases the validity of the responses and reduces confounding by socioeconomic status. Due to the observational design, we cannot deny the possibility of residual confounding by variables that were not accounted for.

In conclusion, many studies have associated the Covid-19 pandemic and lockdown with psychological and lifestyle changes. Our study shows that the Covid-19 lockdown is also associated with a significant worsening of sleep quality. Moreover, although the end of lockdown brought about a slight improvement, mean scores in the BEAR scale remained significantly higher than before, suggesting the consequences on sleep quality could persist overtime. This worsening is higher in children whose parents did not have higher studies. Helping children to maintain healthy sleeping habits despite the circumstances and providing early psychological support when needed is important to prevent negative psycho-physical symptoms from lockdown that could persist over the years. These recommendations should be considered in order to develop preventive strategies to be implemented in the event of similar catastrophes. More studies are needed to determine the long-term effects of the COVID19 lockdownto mitigate them and, if necessary, to define prevention strategies that could be implemented in the event of a similar situation occurring again..

Data Availability

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy reasons.

References

- Anderson, R.M.; Heesterbeek, H.; Klinkenberg, D.; Hollingsworth, T.D. How will country-based mitigation measures influence the course of the COVID-19 epidemic? Lancet 2020, 395, 931–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cao, W.; Fang, Z.; Hou, G.; Han, M.; Xu, X.; Dong, J. The psychological impact of the COVID-19 epidemic on college students in China. Psychiatry Res. 2020, 287, 112934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zengin, M.; Yayan, E.H.; Vicnelioğlu, E. The effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on children's lifestyles and anxiety levels. J Child Adolesc Psychiatr Nurs. 2021, 34, 236–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uccella, S.; De Grandis, E.; De Carli, F.; D'Apruzzo, M.; Siri, L.; Preiti, D.; Di Profio, S.; Rebora, S.; Cimellaro, P.; Biolcati Rinaldi, A.; et al. Impact of the COVID-19 Outbreak on the Behavior of Families in Italy: A Focus on Children and Adolescents. Front Public Health. 2021, 9, 608358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bortz, W.M. The disuse syndrome. West J Med. 1984, 141, 691–694. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Phillips, C. Brain-derived neurotrophic factor, depression, and physical activity: making the neuroplastic connection. Neural Plast. 2017, 7260130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pisano, S.; Catone, G.; Gritti, A.; Almerico, L.; Pezzella, A.; Santangelo, P.; Bravaccio, C.; Iuliano, R.; Senese, V.P. Emotional symptoms and their related factors in adolescents during the acute phase of Covid-19 outbreak in South Italy. Ital J Pediatr. 2021, 47, 86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dewald, J.F.; Meijer, A.M.; Oort, F.J.; Kerkhof, G.A.; Bögels, S.M. The influence of sleep quality, sleep duration and sleepiness on school performance in children and adolescents: A meta-analytic review. Sleep Med Rev. 2010, 14, 179–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pisano, S.; Catone, G.; Gritti, A.; Almerico, L.; Pezzella, A.; Santangelo, P.; Bravaccio, C.; Iuliano, R.; Senese, V.P. Emotional symptoms and their related factors in adolescents during the acute phase of Covid-19 outbreak in South Italy. Ital J Pediatr. 2021, 47, 86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halford, E.A.; Lake, A.M.; Gould, M.S. Google searches for suicide and suicide risk factors in the early stages of the COVID-19 pandemic. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0236777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romanos-Nanclares, A.; Zazpe, I.; Santiago, S.; et al. Influence of parental healthy-eating attitudes and nutritional knowledge on nutritional adequacy and diet quality among preschoolers: the SENDO project. Nutrients 2018, 10, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bastida-Pozuelo, M.; Sánchez-Ortuño, M. Preliminary analysis of the concurrent validity of the Spanish translation of the BEARS sleep screening tool for children. J Psychiatr Ment Health Nurs 2016, 23, 513–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Owens, J.A.; Dalzell, V. Use of the ‘BEARS’ sleep screening tool in a pediatric residents’ continuity clinic: a pilot study. Sleep Med. 2005, 6, 63–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raynero Mellado, R.C.; Villaizán Pérez, C.; Martínez Gimeno, A. Detección precoz de patología del sueño en Pediatría de Atención Primaria. Utilidad de los cuestionarios de cribado de patología del sueño. Rev Pediatr Aten Primaria. Supl. 2020, 28, 145–146. [Google Scholar]

- Pin Arboledas, G. Sociedad Española de Pediatría Extrahospitalaria y Atención Primaria (SEPEAP). Anexo: cuestionarios y herramientas. Pediatría Integral. 2010, XIV, 749–758. [Google Scholar]

- Cheung, C.; Bedford, R.; Saez De Urabain, I.; et al. Daily touchscreen use in infants and toddlers is associated with reduced sleep and delayed sleep onset. Sci Rep 2017, 7, 46104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carter, B.; Rees, P.; Hale, L.; Bhattacharjee, D.; Paradkar, M.S. Association Between Portable Screen-Based Media Device Access or Use and Sleep Outcomes: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. JAMA Pediatr. 2016, 170, 1202–1208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balenzano, C.; Moro, G.; Girardi, S. Families in the Pandemic Between Challenges and Opportunities: An Empirical Study of Parents with Preschool and School-Age Children. Italian Sociological Review. 2020, 10, 777. [Google Scholar]

- Qiu, J.; Shen, B.; Zhao, M.; Wang, Z.; Xie, B.; Xu, Y. A nationwide survey of psychological distress among Chinese people in the COVID-19 epidemic: Implications and policy recommendations. Gen. Psychiatry. 2020, 33, e100213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Pan, R.; Wan, X.; Tan, Y.; Xu, L.; Ho, C.S.; Ho, R.C. Immediate Psychological Responses and Associated Factors during the Initial Stage of the 2019 Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) Epidemic among the General Population in China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 1729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brooks, S.K.; Webster, R.K.; Smith, L.E.; Woodland, L.; Wessely, S.; Greenberg, N.; Rubin, G.J. The psychological impact of quarantine and how to reduce it: Rapid review of the evidence. Lancet 2020, 395, 912–920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McAlonan, G.M.; Murphy, D.G.; Edwards, A.D. Multidisciplinary research priorities for the COVID-19 pandemic. Lancet Psychiatry 2020, 7, e35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lippi, G.; Henry, B.M.; Sanchis-Gomar, F. Physical inactivity and cardiovascular disease at the time of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) Eur. J. Prev. Cardiol. 2020, 27, 906–908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schrempft, S.; Jackowska, M.; Hamer, M.; Steptoe, A. Associations between social isolation, loneliness, and objective physical activity in older men and women. BMC Public Health 2019, 19, 74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, X.; Zhu, W.; Kang, S.; Qiu, L.; Lu, Z.; Sun, Y. Association between Physical Activity and Mood States of Children and Adolescents in Social Isolation during the COVID-19 Epidemic. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2020, 17, 7666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peluso, M.A.M.; de Andrade, L.H.S.G. Physical activity and mental health: The association between exercise and mood. Clinics 2005, 60, 61–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, B.; Zhu, B. Mental health of university students in Shanghai and its relationship with physical exercise. Psychol. Sci. 1997, 20, 235–238. [Google Scholar]

- Norris, R.; Carroll, D.; Cochrane, R. The effects of physical activity and exercise training on psychological stress and well-being in an adolescent population. J. Psychosom. Res. 1992, 36, 55–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hale, L.; Guan, S. Screen time and sleep among school-aged children and adolescents: a systematic literature review. Sleep Med Rev. 2015, 21, 50–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hale, L.; Kirschen, G.W.; LeBourgeois, M.K.; Gradisar, M.; Garrison, M.M.; Montgomery-Downs, H.; Kirschen, H.; McHale, S.M.; Chang, A.M.; Buxton, O.M. Youth Screen Media Habits and Sleep: Sleep-Friendly Screen Behavior Recommendations for Clinicians, Educators, and Parents. Child Adolesc Psychiatr Clin N Am. 2018, 27, 229–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arufe Giráldez, V.; Cachón Zagalaz, J.; Zagalaz Sánchez, M.L.; Sanmiguel-Rodríguez, A.; González Valero, G. Equipamiento y uso de Tecnologías de la Información y Comunicación (TIC) en los hogares españoles durante el periodo de confinamiento. Asociación con los hábitos sociales, estilo de vida y actividad física de los niños menores de 12 años. Revista Latina De Comunicación Social, 2020; 183–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curtis, R.G.; Olds, T.; Ferguson, T.; Fraysse, F.; Dumuid, D.; Esterman, A.; Hendrie, G.A.; Brown, W.J.; Lagiseti, R.; Maher, C.A. Changes in diet, activity, weight, and wellbeing of parents during COVID-19 lockdown. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0248008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kimura, M.; Kimura, K. Ojima, T. Relationships between changes due to COVID-19 pandemic and the depressive and anxiety symptoms among mothers of infants and/or preschoolers: a prospective follow-up study from pre-COVID-19 Japan. BMJ Open 2021, 11, e044826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malkawi, S.H.; Almhdawi, K.; Jaber, A.F.; Alqatarneh, N.S. COVID-19 Quarantine-Related Mental Health Symptoms and their Correlates among Mothers: A Cross Sectional Study. Matern Child Health J. 2021, 25, 695–705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Panda, P.K.; Gupta, J.; Chowdhury, S.R.; Kumar, R.; Meena, A.K.; Madaan, P.; Sharawat, I.K.; Gulati, S. Psychological and Behavioral Impact of Lockdown and Quarantine Measures for COVID-19 Pandemic on Children, Adolescents and Caregivers: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J Trop Pediatr. 2021, 67, fmaa122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panchal, U.; Salazar de Pablo, G.; Franco, M.; Moreno, C.; Parellada, M.; Arango, C.; Fusar-Poli, P. The impact of COVID-19 lockdown on child and adolescent mental health: systematic review. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2021, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).