1. Introduction

This study investigates students’ mental well-being during online (or open) distance learning (henceforth, ODL) in one of the public universities in Malaysia. According to Asirvatham, Kaur, and Abas (2005) as cited in [

1], “[t]he development of e-learning in Malaysia started during the pre e-learning era when the Educational Technology Division was set up by the Ministry of Education in 1972”. This goes to show that the evolution of technology in the field of education is nothing new to the country, but until more recently, the urge to go online can be seen in Malaysia as educational institutions are instructed to conduct lessons online due to the unprecedented COVID-19 crisis. Although technological advances have made the availability to do online learning more economical and practical, the recent COVID-19 pandemic has proven to accelerate the implementation of doing many types of business online, including education. This however, has recognised a number of challenges in relation to student/teacher preparedness, facilities and learning environments as well as teaching/learning style and assessments.

A brief chronological turn of events began with the first announcement of the COVID-19 outbreak in China in December 2019. This then triggered a series of alarm for many countries, including Malaysia in late January 2020. When this happened, Prime Minister Tan Sri Muhyiddin Yassin declared for an official community-wide containment, also known as the Movement Control Order (MCO) that began on the 18th March 2020. During this stage, Malaysians were notified of this form of “emergency” and that all businesses were forced to be closed while everyone stayed at home (except for medical officers and others that were referred to as the “frontliners”). While the MCO continued to be implemented into its third and fourth week, ministries began to devise a plan for how things were going to continue as the COVID-19 pandemic remained to be a threat. For the Ministry of Higher Education (KPM), the closure of higher learning institutions meant that online learning was the only logical solution. However, the abrupt shift towards online learning, combined with the admonition to stay put during MCO (be it on university premises or individual homes) may have significant impact on students.

At UiTM, all traditional face-to-face classes wered moved to open and distance learning that was effective April 13 for the duration of the semester [

2]. This ODL mode is referred to as a combination of synchronous and asynchronous online learning, where interactions online can either be conducted live, i.e. during real time or not. According to Erny Arniza Ahmad, a felo at UiTM’s Centre for Innovative Delivery & Learning Development (CIDL), the Open and Distance Learning (ODL) envisioned at the university “refers to the provision of flexible educational opportunities in terms of access and multiple modes of knowledge acquisition” [

3]. She explains that this form of learning is realised by making learning more flexible and accessible via various means of platforms, usually ones that are online to help resolve issues related to learning like the one experienced during the community-wide containment. In essence, it was promoted so that learning can be conducted regardless of time or place. According to the UiTM’s Career and Counseling Centre website, ODL is ‘a form of open learning that can be done or accessed anytime and anywhere. ODL is not bounded to one particular place like in the classroom or via face-to-face’ (English translation). Although this is not the first time that ODL is practiced, it is widely implemented across all UiTM campuses and branches as a means to continue the teaching and learning process given the impact of COVID-19.

There is thus a need to reflect on this ODL experience, especially feedback from students that would be essential for future improvements. This study focuses on students’ first ODL experience during the COVID-19 MCO period and how it has influenced their mental state of being. A survey that incorporated a mental health screening tool is used to measure students’ emotional states of depression, anxiety and stress during the final week of their ODL experience. The present study aims to explore the impact of ODL on students’ mental well-being, especially during times of a community-wide containment that is a result of a health pandemic.

2. Materials and Methods

The purpose of this paper is to examine student’s well-being throughout the first implementation of classes online as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic. Since this is the first time that a full term is conducted 100% online and plans of reverting back to the traditional classroom is uncertain, it has become necessary to take stock in the unique experience and discover lessons that could be learnt for the future. Given this, a questionnaire was developed to identify students’ responses to the unprecedented situation, followed by a short open discussion that acts as a reflection on their last day of classes. Four classes that comprised two groups of EPE470 (English Pronunciation in Use), one group of EPC565 (Pragmatics for Business Professional Settings) and one group of ELC640 (English for Job Applications) took part in the study. On average, there were about 25 students per class (the highest number is 31), which amounted to over 100 students being taught online during the semester. It is important to bear in mind that three groups are from the English for Professional Communication (LG240) program, while the ELC640 group is from the Arabic for Professional Communication program (LG242).

2.1. Survey Items

The survey presents a novel approach that adopts and adapts from a combination of items taken from the literature. These mainly include two major parts below:

Table 1 presents items that make up the survey used in the present study. In the first part, students were asked to describe a little bit about themselves. Since the university was closed during the MCO period and students were allowed to go home during the semester, it was also important to identify students’ living conditions as significant factors in the online learning environment. This was where Azuddin’s [

4] study seemed relevant and in turn, items from his questionnaire were adopted. In his study, Azuddin argued that “the MCO has exposed the real nature of inequality, starting with our homes. Moving forward, policies should give consideration of mental well-being when designing and developing living spaces, especially for the most vulnerable of society who live in low-cost housing” [

4]. For the present study, this is particularly interesting to see whether any connections can be made between students’ living conditions that may have contributed to their answers in the survey.

The short form of the Depression Anxiety Stress Scales or ‘DASS-21’ [

5] is the second part of the study - a self-report survey that has been used widely in both clinical and non-clinical research [e.g., 6, 7]. The DASS-21 is a set of three self-report scales designed to measure the negative emotional states of depression, anxiety and stress, on a 4-point severity/frequency scale. As the essential development of DASS-21 was carried out with non-clinical samples [

5], it is suitable for screening normal adolescents and adults. In fact, they contend that “the depression, anxiety and tension/stress manifested by non-psychotic clinical outpatients and by normal non-clinical groups differ primarily in severity” [

5] (p. 341). They continue to explain that the three syndromes, labelled depression, anxiety and stress, “may be distinguished from self-report data by the DASS scales” [

5] (p. 342) and that it may be of “considerable use for researchers dealing with complex links between environmental demands and emotional and physical disturbance” [

5] (p. 343). This in turn, made it useful for DASS-21 to be incorporated in the present study.

DASS-21 is a shorter version of the original 42-item self-report questionnaire in which seven statements indicating separate emotional states (depression, anxiety and stress) are posed to reflect respondent’s levels of severity of a particular symptom experienced over the past week.

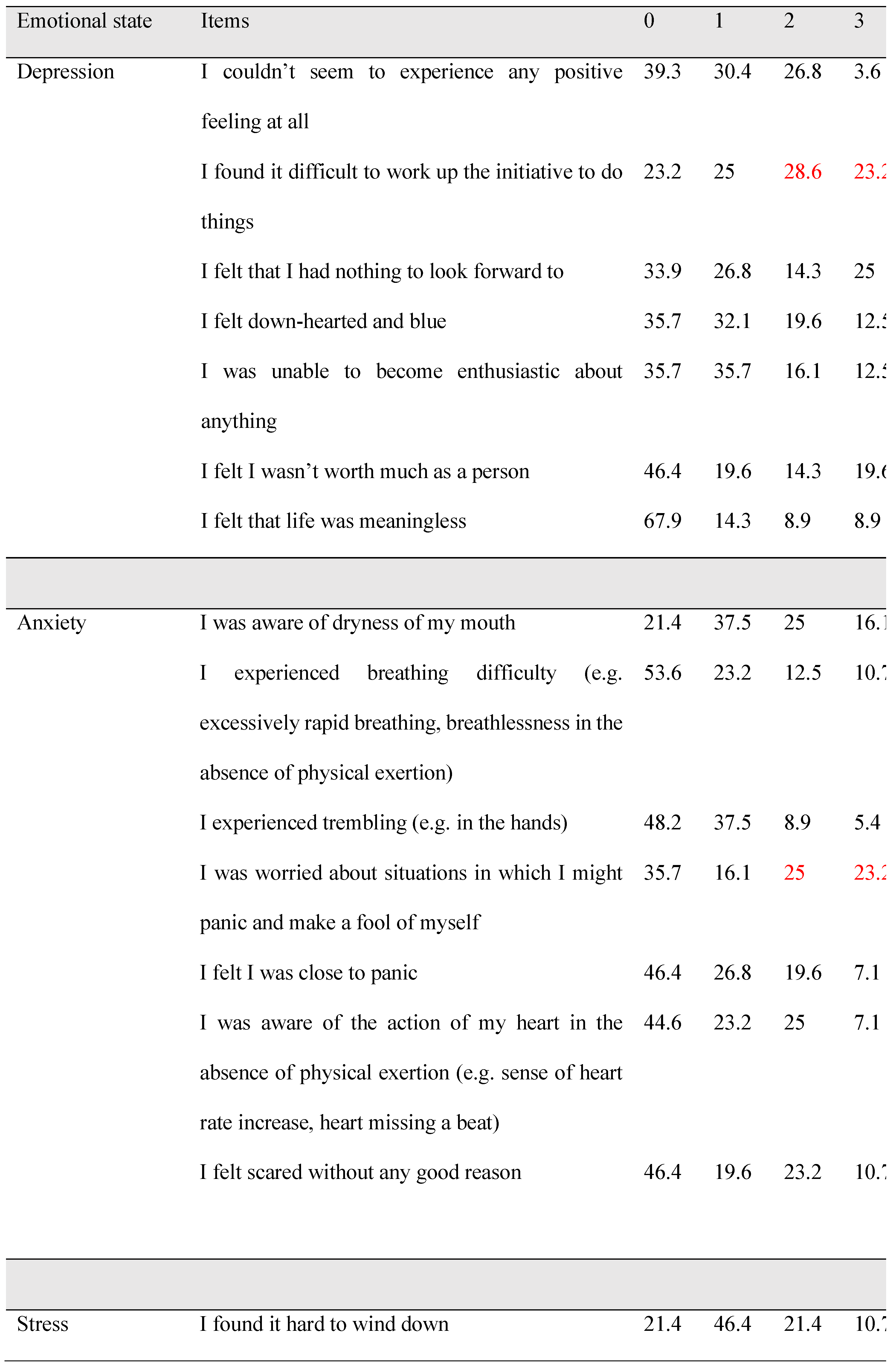

Table 2 below shows the list of items or statements that were included in the survey. The Depression scale seeks to find symptoms related to feelings of anhedonia (inability to feel pleasure in normally pleasurable activities), inertness, hopelessness, dysphoria (opposite of euphoria), lack of interest, self-deprecation and devaluation of life. The Anxiety scale on the other hand assesses autonomic arousal such as palpitation, hyperventilation, or nausea, skeletal muscle effects like trembling, situational anxiety, and subjective experience of anxious affect. Meanwhile, the content of the Stress scale suggests that it is measuring a state of persistent arousal and tension with a low threshold for becoming upset or frustrated [

5] (p. 342). Items for the Stress scale also point to difficulty relaxing, nervous tension, irritability, impatience and agitation.

Students were asked to use 4-point severity/frequency scales (0 being the statement did not apply to them at all, to 3 being a statement which applied to them very much/most of the time) to rate the extent to which they have experienced each emotional state over the past week. Students’ reflection of their past week would then reflect how the ODL experience has impacted them throughout the course, leading up to the final week of lessons. Scores for Depression, Anxiety and Stress are finally summed following the scoring template and then reflected using the score versus severity as illustrated in

Table 3 below.

Similar to [

4], it is important to note that the present study is not diagnostic. This means that results from the survey does not entail that a student is identified with depression, anxiety or stress as a medical condition –only a qualified professional can rule that out – so the caveat lies in treating results from this study as a more generic description of students’ emotions overall. As Lovibond and Lovibond stressed, “the major development of the DASS scales was carried out with normal, non-clinical samples. Thus, the central aim underlying development of the DASS scales was to generate measures of general negative affective syndromes” [

5] (p. 336), and so results from the present study is not diagnostic, but indicative of how students’ feelings may contribute to their overall answers in the questionnaire.

Therefore, as

Table 1 displays, this study adopted and adapted items from Azuddin’s [

4] study of Malaysian’s wellbeing during the MCO as well as incorporating the DASS-21 scales from [

5]. The survey firstly begins with a number of questions about where students lived, who they were staying with and their access to personal space during the MCO period. Since students did not continue their classes on campus, questions related to where they were spending the quarantine equaled to where they conducted their ODL, and in turn, were linked to their levels of depression, anxiety and stress as measured by the DASS-21 scales. Since DASS-21 functions to measure the negative emotional states of depression, anxiety and stress, it constituted the second part of the survey. The present study then concludes with a reflective discussion during the final day of class where students express their opinions about how they felt about the ODL experience overall.

2.2. Procedures

The survey was distributed to students online via Google Forms during the last week of the semester (30th June – 2nd July 2020). Students were informed of the research during the last class and a link to the survey was shared on their respective Google Classroom streams after classes ended. As part of consolidating the entire semester, these final classes focused on a discussion with students reflecting on the whole experience, and so informing students about the research and administering the survey during this time was found to be most appropriate. In addition, students were told that during the online reflection lesson (Live Meet via Google), I would be asking them general questions related to their experiences and specific questions pertaining to the study. Findings from these sessions are recorded (with permission) and reviewed again later for analysis. Students were also notified that taking part in this study was entirely voluntary and participation would include that their answers would be published in an academic work. Furthermore, their names and personal details would not be disclosed for obvious ethical reasons.

Once students were given ample time to respond to the survey (three consecutive days), the survey was closed. Students were reminded of the time when survey was going to close in a post shared on their respective Google Classroom streams. Since students were still completing assessments at the time, it was felt that a reminder was essential to grab their attention back to the study. A total of 52 out of 114 students (45.6%) responded. Recorded sessions of the last classes were also reviewed based on verbal responses that students may have, which would be relevant to the study. Answers were then analysed together with the respective survey findings in order to obtain a more in-depth view of students’ experience. Scores from the DASS-21 scales are calculated by totaling the score following a scoring template and then analysed based on the severity level or range of the three emotions as presented in

Table 2 earlier. This was then followed by a discussion that include students and their learning environment during MCO; students and their mental well-being during MCO; and students’ overall reflections.

3. Results

In this section, findings are presented according to the survey items. This means that the description of results will begin with answers to the first half of the survey, followed by the scores obtained from DASS-21. The remainder part of this section will then attempt to bring these two results together along with findings from the recorded reflective sessions to make sense of students’ overall ODL experience.

3.1. Students and their Learning Environment during MCO

3.1.1. Demographics

In total, 56 students participated in this survey; 49 (87.5%) of them female students while the remaining 7 (12.5%) were male students. These students range from ages 18 to 23 and above.

Table 4.

List of respondents.

Table 4.

List of respondents.

| Group |

% |

| LG2404Bi (EPE470) |

28.6 |

| LG2402Di (EPE470) |

17.9 |

| LG2404Bi (EPC565) |

28.5 |

| LG242Ai (ELC640) |

25 |

3.1.2. Living Descriptions

In terms of their living conditions, students mostly made up of 53.6% urban dwellers, followed by those living in the suburban (30.4%) and rural areas (16.1%). When further asked about their type of residence, majority lived in terrace houses (53.6%), followed by bungalows or semi-Ds (30.4%). Less than 10% lived in low-cost housing areas (7.1%) and apartments or condos (also 7.1%) respectively whereas 1 person stayed in the flats.

Given their state of living, it was then important to know how many residents were occupying the residence. 48.2% of them stated that they shared living conditions among 4-5 people while 30.4% have their homes with 6-7 people. A lesser portion of them live with up to 7 or more people per household (12.5%) and only 5 respondents answered 2-3 people. This gives us an idea that the 5 students may be an only child or living with a single parent. At the time of survey, none were found to be living by themselves during the MCO period.

A further important question to ask then would be to know if students had access to their own personal or private space. This is significant for the study as the learning environment is one of the factors to effective learning [

8]. Fortunately, over half of the respondents answered ‘yes’ (58.9%) with 32.1% of them answered ‘maybe’. Only 5 students replied ‘no’. This could be those that either live in smaller houses or live with more than 4 people. When asked about what they think about their current living conditions, almost 70% of students stated that they were satisfied with their living conditions. Eleven students were not satisfied, while six of them were unsure.

3.1.3. Relationship between Students’ Living Condition and ODL

In terms of their satisfaction towards the ODL experience in the present semester, it is surprising to find that more than half of them were unsure (57.1% responded ‘maybe’). Only 11 students were satisfied while 13 of them answered ‘no’. These preliminary findings suggest that despite their living conditions, students were somewhat not satisfied with their online distance learning experience –their uncertainty to answer this question implies hesitance that most likely contributes to their not being satisfied completely with the experience. In order to find out more about how they felt, the following question had students rate between a scale of 1 to 5 (1 being very unhappy and 5 being very happy) on the ODL experience. Here it was found that there were mixed reviews. A total of 12 students rated their happiness level between 1 and 2, which means that they were unhappy. However, 13 students rated between 4 and 5, tipping the scale towards students that are happy with the ODL, by only 1. The bulk of the number, that is 31 of them (55.4%) answered 3 and this indicates that majority of students are neither happy nor unhappy with the experience. This can be interpreted in two ways: 1) students are unsure of how they felt and so they are described as feeling indifferent, or 2) students are neutral and so the next part of the survey would be more telling of how students actually feel.

3.2. Students and their Mental Well-being during ODL

As described in the previous section, findings have yielded mixed reviews among students especially in terms of how they felt about the ODL experience. In turn, this next section presents further answers from the second half of the survey that tapped into students’ feelings in more detail, through use of DASS-21 scales. It would be important to note that as explained earlier in the administration of DASS-21 items, statements are to be measured by how students felt in the last week of their ODL semester. It would also be useful to explain, for reasons of presentation, that the items in

Table 2 earlier represent the classification of emotional states, but are not necessarily ordered in that particular sequence in the actual survey. To reiterate, students had to rate from a scale of 0 to 3 (0 indicating that the statement did not apply to them and 3 indicating that the statement applied to them very much or most of the time) of the DASS-21 items.

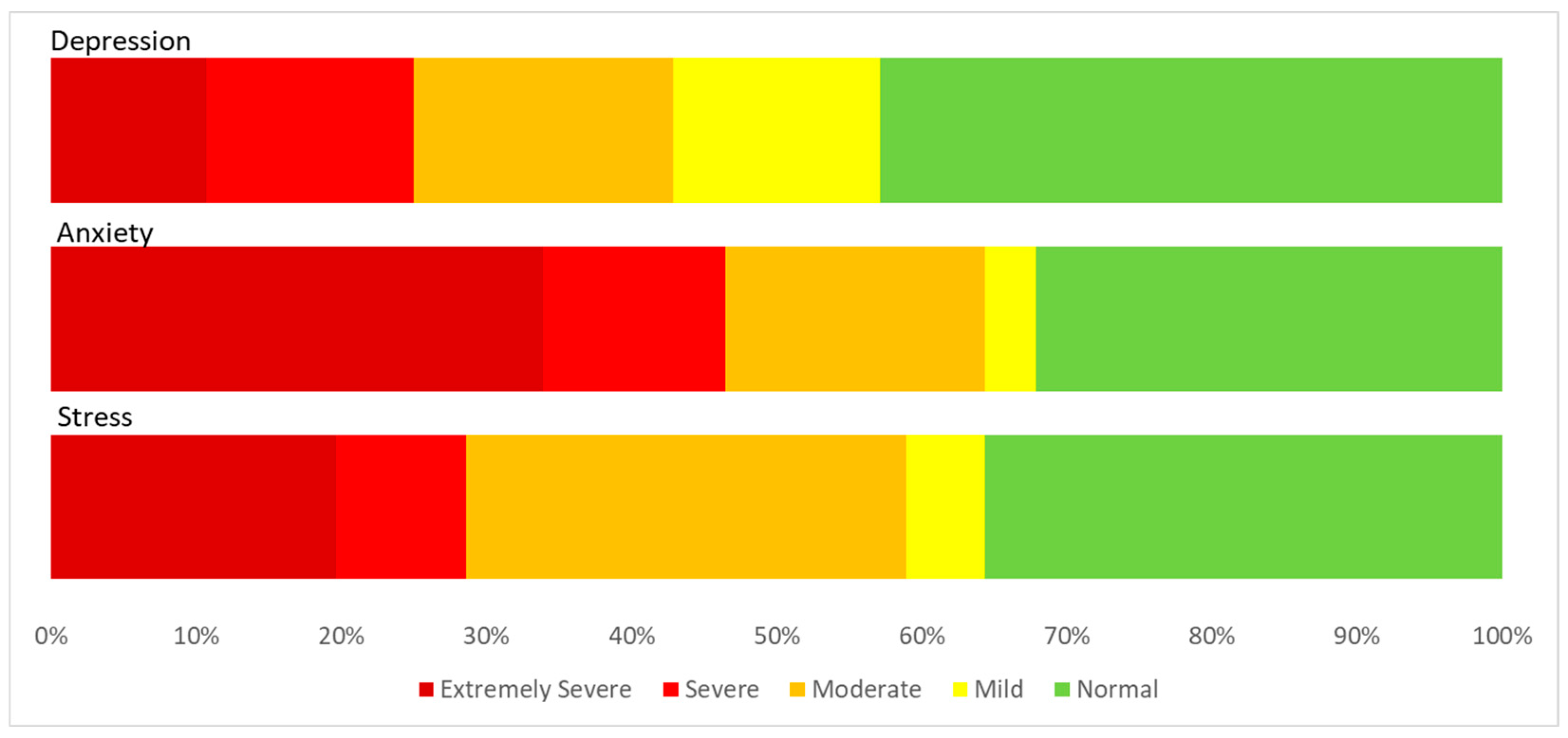

Figure 1 summarizes results for the DASS-21 evaluation. As can be seen, findings show that students suffer huge amount of negative emotions during the ODL with more than 60% of them self-reporting varying degrees of anxiety and stress, while 59% reported experiencing varying levels of depression. Of these, 48% of them self-reported severe and extremely severe anxiety, while less than 30% reported to have experienced similar degrees of stress and depression.

Closer inspection reveals that students mostly experienced being worried about situations in which they might panic and make a fool of themselves (48.2%), students experienced to be more sensitive (55.4%), and they found it difficult to work up the initiative to do things (51.8%). These were collectively to be found occurring among students to a considerable degree or most of the time during ODL (see Appendix for detailed scores). Thus, repeated occurrences of these feelings indicate their level of severity, which in turn, reports students’ negative emotions ranging from high-levels of anxiety to a mixed sense of balance between stress and depression during the ODL experience.

As regards neutral responses for satisfaction and happiness on the ODL experience (57.1% and 55.4% as reported earlier), students can be seen to have answered the DASS-21 more differently, suggesting that students did not seem to be happy overall. By examining the DASS-21 responses, we can argue that students experience more negative emotions throughout the ODL, particularly feeling anxious most of the time. However, it is important to remember that the administration of DASS is not diagnostic, i.e. results do not identify students with depression, anxiety or stress as a medical condition here, and that any diagnosis of mental health or mental illness needs to be analysed by a qualified medical professional.

3.3. Students’ Overall Reflection of the ODL Experience

Upon completing the DASS-21 questionnaire, students were asked whether they thought any of their responses were related to the current situation that they were in, i.e. the ODL, the community-wide containment (MCO) or both. 57.1% of them responded ‘Yes’ –their answers were based on what they were going through during this period, while 30.4% responded ‘Maybe’, and 12.5% answered ‘No’. This means that the self-reported findings from DASS tell us students’ experience negative emotions during the ODL and that this has shed more light into their more neutral responses about ODL in the first part of the survey.

The study ended with an open-ended question on what students were most worried about during this time and 50 responses were obtained. Here is where responses from this part of the study will be discussed together with findings from students’ online recorded reflective sessions in their final class of the semester. For reasons of space, only several excerpts are documented here to support the analysis. Overall, students were mostly worried about their academic performance (ranging from not being able to complete assignments to not achieving their expected results) and the inability to keep up with expectations. In the reflective discussion sessions, students expressed how ODL has been challenging and exhausting, and that they wished for ODL not to be continued if possible for fear of ODL-related issues that may jeapordize their academic performance.

“Fail any subjects for this semester and losing my mind because of ODL”

“To be honest, I am really worried on whether I will be able to complete all of the assignments given in time. And I am quite worried about my grade since I think Semester 4 is the toughest phase in my degree life.”

“My grades and gpa. I find some of my groupmates have lack of motivation on doing our groups assignment. It's not apply on this course only but for all courses. They seem to lost track with the due dates of our assignments. The procrastinate more and do not reply to my whatsapp. This situation makes me feel stress. I feel like I'm the only person who stay positive in this situation. I believe this situation happens becuase of the individuals themselves. ODL is not the reason of this issue to happen as if there is no ODL, this situation will still happen.”

“In regard of ODL, what worried me the most is the inability to keep up with all the additional exercises (which are like mini-assignments (mostly doing it for attendance) and the additional assessments to substitute final exams, alongside the originally intended assessments for us. Honestly, I've never worked on my studies as hard as how I was throughout ODL because even as a very lazy person, I had to wake up and do my works early due to the amount of works that were given. I think if the semester was extended for like 1-2 weeks more (not for classes, for submission), ODL would be way better, even if we are comparing it to the normal physical classes.”

Some responded by further expressing their feelings like how “some lecturers are pushy on certain works, so it makes me nervous all the time and I felt as if I wasn’t doing good enough. No physical contact with my classmates is also making me stress”. Discussion from the reflective sessions found that students had mixed feelings about classes online where it was difficult to contact lecturers and some were clueless on what to do. One student confessed that ODL did affect her mental health when she began to lose motivation to wake up and face the same online classes every day. The student explained that this was mainly because she found it more difficult to understand classes that are online compared to the traditional way of learning. Another student voiced out that she barely had enough sleep and this may result in her being moody, which would demotivate students even more.

“I'm worried that my emotions may affect my work performance.

I overthink. A lot. I know it's weird but sometimes when I overthink about all my assignments, I can't function?? It's like I'm stressed that I'm not doing my work but at the same time I don't have the motivation/inspiration to finish them?? These last few weeks have been a series of me just staring at my laptop for hours, reading articles, waiting for ideas to flow out of me. Perhaps because it makes me feel less guilty that I'm not actually making progress? I don't know. Nevertheless, despite the endless procrastination, so far I still manage to finish my assignments on time. I just think that if only I could control my emotions, i.e overthinking, I may be able to produce a better quality of work.”

“the feeling of wanting to do well for my academic results, but i think that this ODL session is not quite helping, thus making me nervous to think about i'm probably not gonna achieve my goal.”

“I'm worried of my performance for my semester 4 which i'm scared i performed very poorly due to my mental state and my surroundings which somehow prevents me from doing my work and assignments properly.”

Another frequent finding is on technology woes such as internet connection, software compatibility for certain subjects, and laptop problems/issues. Most of the discussion during the reflective sessions were also about technological problems. These range from households with no wi-fi that resulted in huge internet data being consumed, issues concerning certain online learning platforms that were not as effective for learning purposes (e.g. Microsoft Teams, WhatsApp), and longer preparation time for students to complete assessments especially for recording pair or group presentations. WhatsApp in particular was not favoured to be the main platform for online learning because students find it potentially confusing as communication can be at a fast pace and become too lengthy for discussions to be sustained (WhatsApp however, was viewed as convenient for communicating purposes). In terms of groupwork, this may be extra challenging for students without smooth and fast internet connection. For instance, one student claimed that she felt guilty to her group mates for not being able to contribute much given her issues with the Internet and computer, and this may affect her negative emotions as well. One student likened the ODL experience to a ‘double-edged sword’: although ODL may be convenient and really efficient to do work at one’s own pace, it also provides an option for students to procrastinate. Another expressed that online consultations are few, and if any, they are not as helpful as consulting the instructor face to face. This is particularly problematic when students need to consult their instructors for more clarification on particular assessments or their final year projects. Students also find it concerning that they experience headaches and migraines from staring on the screen for long periods of time. Other examples include:

“At first, as usual, i lost my internet connection during submission. But then my laptop hang n automatically turned off.. and i rushed to computer's shop and repaired it..”

“I had to borrow my little brother's laptop, but his laptop is not compatible with that software 🥴 hahaha.”

One person raised concerns about their family’s health and how it is taking a toll on their studies (“The health of my family members is my main concern at the moment. It is on some level affecting my studies”). On another end, another person pointed out that they struggled doing ODL with their family. Students say that learning from home can have many distractions like having to do chores and harder to concentrate with little children in the house. Others may have to tend to smaller children or the elderly and this may make it harder for them to keep up with their academics. One student replied that his family thinks he’s on vacation -similar experiences like this thus show how family can be more problematic than supportive in the ODL, which may contribute to students’ overall negative emotions. One particular response was alarming since the student replied that he/she worry of taking his/her own life. As UiTM’s Psychiatry Department Faculty of Medicine clinical psychologist, Associate Professor Dr Azlina Wati Nikmat explained, “the restriction on movement and social contact might lead to intense boredom, emotional instability and other psychological issues” [

9]. In this case, the student’s response to the open-ended question of the survey striked a red-flag, showing how the ODL experience during these times may be more overwhelming than some might have thought and hence, examining how students feel during this time is very important. Students who reported to have been overwhelmed by the whole experience were quite candid with their feelings and stated that they felt like waking up just to sign the attendance form and then go back to sleep. This is a clear sign of depressive symptoms that were found in the survey, revealing that students experienced negative emotions throughout the ODL.

Nevertheless, there were students that reported to have enjoyed ODL eventhough they viewed online learning to be demanding. Students expressed that despite being exhausted, they learnt a great deal of technology skills such as how to join online meetings, recording, compressing and uploading videos online that were viewed to be essential for the future. Students were also seen to have become more understanding of one another as they emphatised with the ODL challenges that many of them had to face. Students preferred for live, synchronous type of learning where it is easier to communicate (questions can be asked and replied immediately and more clearly), and that students mostly value for instructors to reveal their faces (switch on their webcams) even if these sessions are recorded and viewed later. In terms of assessments, students mainly found them doable and that students appreciate when deadlines were extended. Some found that working collaboratively may be difficult at times, but at least for the students involved in this study, no serious problems were reported. It was also interesting to find that a number of students enjoyed ODL because they view themselves as introverts –these students expressed that they are normally shy in the classroom and so ODL works better for them as they can seek comfort behind the screen.

4. Discussion

Covid-19 is an example of how when push comes to shove, decisions have to be made, but not everyone will be satisfied or happy. As the present study has hoped to have shown, majority or if not all of these students seem to be struggling in one way or another and in retrospect, their feelings or mental well-being are a result of either the ODL or MCO –or even a combination of both. Almost 70% of students self-reported that they experienced varying levels of anxiety, but it is concerning to see that more than half of this number experience high-levels of anxiety because they feel it most of the time. Closer inspection revealed that students frequently experience feeling anxious of situations where they are worried of panicking, feeling sensitive (emotionally), and feeling less motivated to do anything. This made sense to some of the open-ended responses and post-reflective sessions where students expressed their concern for keeping up with ODL and achieving their academic expectations, which contributed to their high-level of anxiety.

It is interesting to have found that students repeatedly experience feeling (emotionally) sensitive during ODL and this may be attributed to their living conditions and whether it is conducive for ODL. While the study did not investigate this further, it is important to empathise with students and their living conditions because this inadvertently may result in stress, case in point, students not being able to complete additional class exercises and family members viewing students as being on vacation. The first experience of ODL during the MCO period has also found that long periods of no face-to-face or physical contact demotivate students and therefore, lecturers may find it more challenging to provide a more attractive and entertaining classroom experience online. What is more distressing is the possibility of a student to be too overwhelmed to the brink of having suicidal thoughts. These are very serious matters and although only one student responded to be worried for taking his/her own life, the study has definitely showed how ODL during a community-wide containment like the MCO poses numerous issues.

It may be argued that students have been informed much earlier about this transition and therefore are expected to be prepared for the changes to take place. This to me is a lousy assumption and findings from the present study has hopefully revealed that this is truly not the case. Many still are without proper internet connection and even so, their living conditions are not conducive for learning. Hence, I would argue that the government still needs to ensure these amenities are available or made conducive in order for ODL to be conducted more smoothly in the future. In addition, it cannot be denied that the student also has choices whether to continue or defer (to put on hold) their study –at least for the duration of when community-wide containment is implemented. And in this regard, it is the department or university’s responsibility to make this clear to all students in order for them to make an informed decision about their academic choices. Further research would include investigating how institutions and instructors on the other hand, reacted during this time. Eventually, ODL is not for everyone. Those who are more honest with themselves would definitely find that the struggles are real and in hindsight, it would be more critical that students realise this for themselves since they are the stakeholders and, in this case, it is their future that is at stake.

Author Contributions

This study is solely authored by one person.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical review and approval were waived for this study due to informed consent that was obtained from all participants involved in the study.

Informed Consent Statement

“Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.”.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Acknowledgments

I would like to express my heartfelt gratitude to the students who took part in this study of which we would not have come to realise their side of the story. I understand the difficulties that some of these students face/are facing and it is my duty to make their voices heard.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

References

- Goi, C. L., & Ng, P. Y. (2009). E-learning in Malaysia: Success Factors in Implementing E-learning Program. International Journal of Teaching and Learning in Higher Education, 20(2), 237-246.

- Mohd Zahari, M. S. (2020). Switching to eLearning due to COVID-19: UiTM Open Distance Learning (ODL) practice and experience. https://inqka.uitm.edu.my/main/images/stories/Comm/WebD3/INQKA-Prof-Salehuddin.pdf. Accessed 17 October 2020.Ahmad, E. A. (2020). Open And Distance Learning (ODL). https://cidl.uitm.edu.my/CG-Open-Distance-Learning.php. Accessed 17 October 2020.

- Ahmad, E. A. (2020). Open And Distance Learning (ODL). https://cidl.uitm.edu.my/CG-Open-Distance-Learning.php. Accessed 17 October 2020.

- Azuddin, A. (2020, April 28). MCO and Mental Well-Being: Home Sweet Home? The Centre. Accessed 1 July 2020 from https://www.centre.my/post/mco-and-mental-health-living.

- Lovibond, S. H. & Lovibond, P. F. (1995). The structure of negative emotional states: Comparison of the Depression Anxiety Stress Scales (DASS) with the Beck Depression and Anxiety Inventories. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 33(3), 335-343. [CrossRef]

- Abdul Majid, H. S., Abd Hamid, H. S., Alwi, A., & Sulaiman, M. K. (2019). Psychometric properties of the English version of DASS in a sample of Malaysian nurses. Jurnal Psikologi Malaysia, 33(1), 65-69.Author 1, A.B. Title of Thesis. Level of Thesis, Degree-Granting University, Location of University, Date of Completion.

- Othman, Z., & Sivasubramaniam, V. (2019). Depression, anxiety, and stress among secondary school teachers in Klang, Malaysia. International Medical Journal, 26(2), 71-74.

- Brown, H. D. (2000). Teaching by principles: An interactive approach to language pedagogy (2nd ed.). San Francisco: Longman.

- Nikmat, A. W. (2020, April 8). Handling students' mental health during MCO. The New Straits Times (online). Accessed 17 October 2020 from https://www.nst.com.my/education/2020/04/582504/handling-students-mental-health-during-mco.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).