Submitted:

16 March 2023

Posted:

20 March 2023

Read the latest preprint version here

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. Mechanisms of Harm

1.2. Therapeutic Mechanisms

1.3. Therapeutics

1.3.1. Establishing a Healthy Microbiome

1.3.2. Preventing Spike Protein Damage

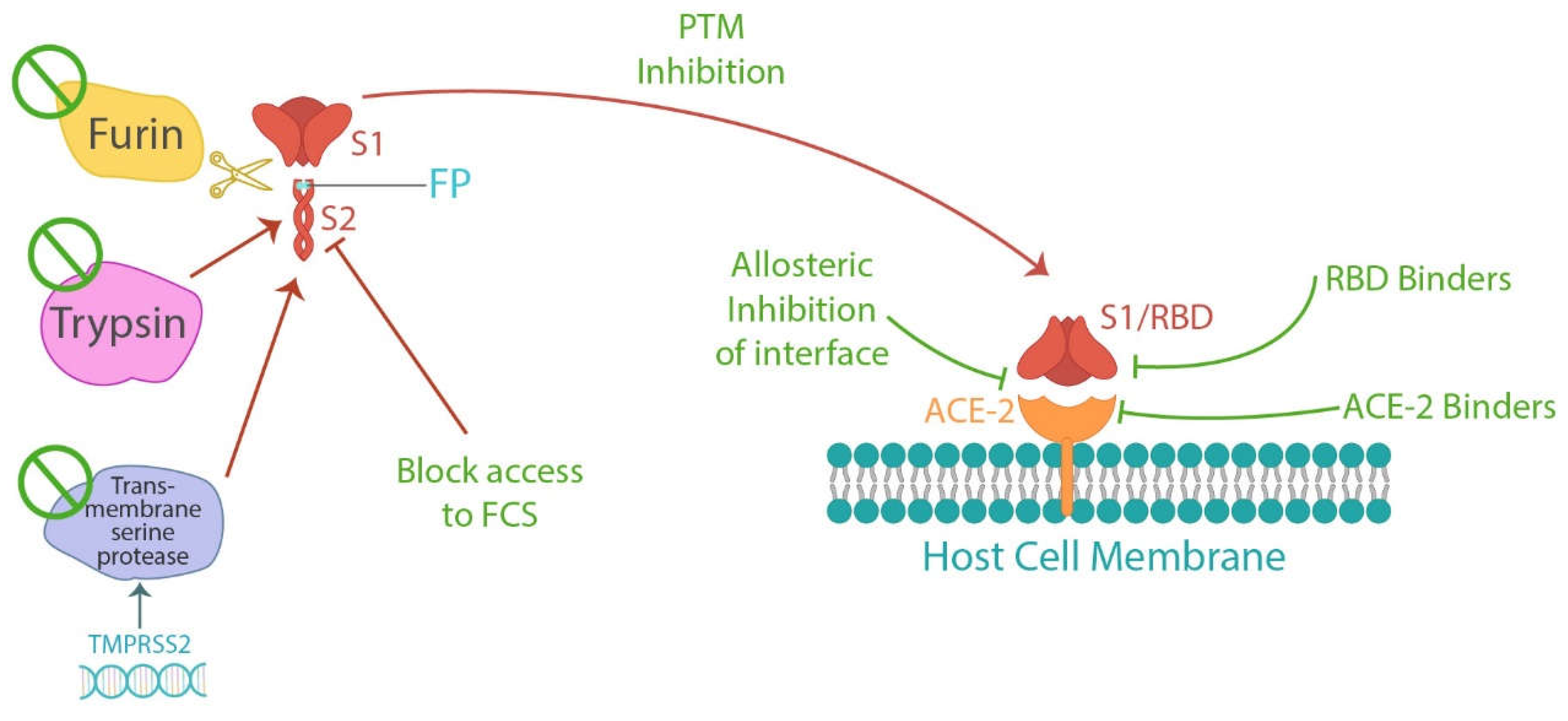

1.3.2. A. Compounds Inhibiting Spike Protein Cleavage

1.3.2. B. Compounds Inhibiting Spike Protein Binding

1.3.3. Clearing Spike Protein

1.3.4. Healing the Damage

2. Methods

3. Results

| Compound | Mechanism | Reference | Clinical Trials | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ivermectin | Multiple Binding of spike protein |

[172,173,174,175,176] | ||

| Corticosteroids | Reducing inflammatory response | [177,178] | NCT05350774 |

Proxy: Significant decrease in breathlessness [179] |

| Antihistamines | Reduced inflammation | [180,181,182] | ||

| Aspirin | Anti-coagulant | [183] | ||

| Low Dose Nalterxone (LDN) | Immunomodulatory | [184,185] | NCT05430152 NCT04604704 |

Significant improvement [185] |

| Colchicine | Reduces inflammation | [186,187,188] | Reduced myocmardial infarction, stroke and cardiovascular death (non Covid-19 or vaccine related) [189] | |

| Metformin | Several | [190] | NCT04510194 | 42% relative decrease in long-covid incidence after treatment of initial C19 infection [191] |

| Compound | Mechanism | Reference | Clinical Trials | Evidence Summary |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vitamin D | Immunomodulatory | [192,193,194] | NCT05356936 | Proxy (C19 severity) [195] |

| Vitamin C | Immune support, antioxidant | [177,178] | NCT05150782 | Reduction in fatigue (not long-covid related) [196] improved oxygenation, decrease in inflammatory markers and a faster recovery were observed in initial covid-19 infection (proxy measure for long-covid) [197] Improvement in general fatigue symptioms when combined with l-arginine [198] Significant improvement [199] |

| Vitamin K2 | Immunomodulatory | [180,181,182] | NCT05356936 | Proxy evidence (severity of covid infection) [200] |

| N-Acetyl Cysteine (NAC) | Antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, cellular metabolism, Blocks S-ACE2 interface (IS [201]) |

[202,203,204,205,206] | NCT05371288 NCT05152849 |

Proxy evidence (severity of covid infection) |

| Glutathione | Antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, cellular metabolism | [207,208,209] | NCT05371288 | Proxy (severity of covid infection) [209,210] |

| Melatonin | Antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, cellular metabolism | [186,187,211,212] | Proxy (higher rate of recovery, lower risk of intensive care unit admission) [213] | |

| Quercetin | Anti-inflammatory Blocks spike-ACE2 interaction [214,215] |

[214,216,217,218] | Proxy (faster time to negative PCR test when combined with Vitamin D and curcumin) [219] | |

| Emodin | Blocks spike-ACE2 interaction [220] | [220] | ||

| Black cumin seed extract (nigella sativa) |

Anti-inflammatory | [221,222,223] | ||

| Resveratrol | Anti-inflammaotry, anti-thrombotic | [224,225,226] | Proxy (lower rates of hospitalization) [227] | |

| Curcumin | Inhibits spike-ACE2 interaction, Inhibits virus encapsulation [228], Binds SC2 proteins (IS) [229] |

[228,230,231,232] | NCT05150782 | Proxy (lowers inflammatory cytokines) [232,233] |

| Magnesium | Multifactorial, nutritional support | [234,235] | Proxy (low magnesium-calcium ratio associated with higher C19 mortality [236], low magnesium associated with higher risk of infection [237]) | |

| Zinc | [238,239,240] | NCT04798677* | Proxy (possibe better acute C19 outcomes [241], other meta-analysis did not confirm efficacy [242]) | |

| Nattokinase | Anti-coagulant, Degrades spike (IV) [154] |

[153,154] | Proxy: Degrades spike protein in vitro [154] | |

| Fish Oil | Anti-coagulant | [243,244,245] | NCT05121766 | Proxy (lowered hospital admission and mortality [243]) |

| Luteolin | Decreases inflammation [246] | [246,247,248] | NCT05311852 | Faster recovery of olfactory dysfunction when combined with Ultramicronized Palmitoylethanolamide and olfactory training [249] |

| St. John’s Wort | Decrease inflammation [250] | [250,251] | ||

| Fisetin | Senolytic [252] Binds SARS-CoV-2 main protease (IS) [253] Binds spike protein (IS) [254] |

[252,254,255] | ||

| Frankincense | Binds to Furin | [256] |

NCT05150782 |

Positive impact [257] |

| Apigenin | Binds SARS-CoV-2 spike (IS [215]), antioxidant [258] | [259,260] | ||

| Nutmeg | Anti-coagulant | [261] | ||

| Sage | Inhibits replication (IV) [262] |

[262,263] | ||

| Rutin | Binds spike [264] | [265] | NCT05387252† | |

| Limonene | Anti-inflammatory | [266] | Antiviral in in vitro assays as whole bark product [267] | |

| Algae | Immunomodulatory [268] | [269,270,271] | NCT05524532 NCT04777981 |

|

| Dandelion leaf extract | Blocks S1-ACE2 interaction (IS+ IVT [272] | [272] [272] | Proxy (reduction of sore throat in combination with other extracts [273] | |

| Cinnamon | Immunomodulatory [274,275] | [276,277] | ||

| Milk thistle extract (Silymarin) | Antioxidant, anti-inflammatory [278] Endothelial protective (IVO [279]) Blocks Spike [279] |

[279] | Evidence for mechanism, but not treatment as of Oct.2022 [278] | |

| Andrographis | Binds ACE2 (IVT), reduction in viral load (IVT) [280] | [281,282,283,284,285,286,287] | Proxy (no decrease in C19 severity [288] | |

| prunella vulgaris | Blocks Spike [186,289] | [290] | ||

| Licorice | Immunomodulatory, anti-inflammatory [291] | [292,293,294,295,296] | Proxy (inhibits virus in vitro [296]) | |

| Cardamom | Anti-inflammatory (IVO [297] | [297] | Proxy (lowers inflammatory markers) [297] | |

| Cloves | Antithrombotic, anti-inflammatory [298], Blocks S1-ACE2 interaction (IS, CFA) [299], stimulates autophagy [300] |

[298] | Prevents post-Covid cognitive impairment [301] | |

| Ginger | [302,303] | Proxy. Reduced hospitalization period in SC2 infection [304] | ||

| Garlic | Immunomodulatory [305] | [305,306,307] | Proxy (faster recovery from C19) [308] | |

| Thyme | Antioxidant, nutrient rich, anti-inflammatory [309] | [310] | Positive impact [257] | |

| Propolis | ACE2 signalling pathways (IS [311],IVT,IVO) [312,313] Immunomodulation [314] |

[312,315,316] | Meta-analysis reveals propolis and honey could probably improve clinical Covid-19 symptoms and decrease viral clearance time [311] |

4. Discussion

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ritchie, H.; Mathieu, E.; Rodés-Guirao, L.; Appel, C.; Giattino, C.; Ortiz-Ospina, E.; Hasell, J.; Macdonald, B.; Beltekian, D.; Roser, M. Coronavirus Pandemic (COVID-19). Our World in Data 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Staff, G. COVID 19 Vaccine production to January 31st 2022Global Commission for Post-Pandemic Policy. Available online: https://globalcommissionforpostpandemicpolicy.org/covid-19-vaccine-production-to-january-31st-2022/ (accessed on 2022).

- Halma, M.; Rose, J.; Jenks, A.; Lawrie, T. The Novelty of mRNA Vaccines and Potential Harms: A Scoping Review. 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ARCHIVE: Conditions of Authorisation for COVID-19 Vaccine Pfizer/BioNTech (Regulation 174). Available online: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/regulatory-approval-of-pfizer-biontech-vaccine-for-covid-19/conditions-of-authorisation-for-pfizerbiontech-covid-19-vaccine.

- Ball, P. The lightning-fast quest for COVID vaccines — and what it means for other diseases. Nature 2020, 589, 16–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anand, P.; Stahel, V.P. Review the safety of Covid-19 mRNA vaccines: a review. Patient Saf Surg 2021, 15, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Doshi, P. Covid-19 vaccines: In the rush for regulatory approval, do we need more data? BMJ 2021, 373, n1244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bondì, M.L.; Di Gesù, R.; Craparo, E.F. Chapter twelve - Lipid Nanoparticles for Drug Targeting to the Brain. In Methods in Enzymology; Düzgüneş, N., Ed.; Academic Press, 2012; Volume 508, pp. 229–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pottoo, F.H.; Sharma, S.; Javed, M.N.; Barkat, M.A.; Harshita; Alam, M.S.; Naim, M.J.; Alam, O.; Ansari, M.A.; Barreto, G.E.; et al. Lipid-based nanoformulations in the treatment of neurological disorders. Drug Metab Rev 2020, 52, 185–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akinc, A.; Maier, M.A.; Manoharan, M.; Fitzgerald, K.; Jayaraman, M.; Barros, S.; Ansell, S.; Du, X.; Hope, M.J.; Madden, T.D.; et al. The Onpattro story and the clinical translation of nanomedicines containing nucleic acid-based drugs. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2019, 14, 1084–1087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thacker, P.D. Covid-19: Researcher blows the whistle on data integrity issues in Pfizer’s vaccine trial. BMJ 2021, 375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ogata, A.F.; Cheng, C.-A.; Desjardins, M.; Senussi, Y.; Sherman, A.C.; Powell, M.; Novack, L.; Von, S.; Li, X.; Baden, L.R.; et al. Circulating Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) Vaccine Antigen Detected in the Plasma of mRNA-1273 Vaccine Recipients. Clinical Infectious Diseases 2022, 74, 715–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bansal, S.; Perincheri, S.; Fleming, T.; Poulson, C.; Tiffany, B.; Bremner, R.M.; Mohanakumar, T. Cutting Edge: Circulating Exosomes with COVID Spike Protein Are Induced by BNT162b2 (Pfizer–BioNTech) Vaccination prior to Development of Antibodies: A Novel Mechanism for Immune Activation by mRNA Vaccines. The Journal of Immunology 2021, 207, 2405–2410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Röltgen, K.; Nielsen, S.C.A.; Silva, O.; Younes, S.F.; Zaslavsky, M.; Costales, C.; Yang, F.; Wirz, O.F.; Solis, D.; Hoh, R.A.; et al. Immune imprinting, breadth of variant recognition, and germinal center response in human SARS-CoV-2 infection and vaccination. Cell 2022, 185, 1025–1040.e14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spike Protein Behavior. Available online: https://www.science.org/content/blog-post/spike-protein-behavior (accessed on 2022).

- Schlake, T.; Thess, A.; Fotin-Mleczek, M.; Kallen, K.-J. Developing mRNA-vaccine technologies. RNA Biol 2012, 9, 1319–1330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shyu, A.-B.; Wilkinson, M.F.; van Hoof, A. Messenger RNA regulation: to translate or to degrade. EMBO J 2008, 27, 471–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baudrimont, A.; Voegeli, S.; Viloria, E.C.; Stritt, F.; Lenon, M.; Wada, T.; Jaquet, V.; Becskei, A. Multiplexed gene control reveals rapid mRNA turnover. Science Advances 2017, 3, e1700006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patterson, B.; Francisco, E.; Yogendra, R.; Long, E.; Pise, A.; Beaty, C.; Osgood, E.; Bream, J.; Kreimer, M.; Heide, R.V.; et al. SARS-CoV-2 S1 Protein Persistence in SARS-CoV-2 Negative Post-Vaccination Individuals with Long COVID/ PASC-Like Symptom 2022. [CrossRef]

- Patterson, B.K.; Francisco, E.B.; Yogendra, R.; Long, E.; Pise, A.; Rodrigues, H.; Hall, E.; Herrera, M.; Parikh, P.; Guevara-Coto, J.; et al. Persistence of SARS CoV-2 S1 Protein in CD16+ Monocytes in Post-Acute Sequelae of COVID-19 (PASC) up to 15 Months Post-Infection. Frontiers in Immunology 2022, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khan, S.; Shafiei, M.S.; Longoria, C.; Schoggins, J.W.; Savani, R.C.; Zaki, H. SARS-CoV-2 spike protein induces inflammation via TLR2-dependent activation of the NF-κB pathway. Elife 2021, 10, e68563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robles, J.P.; Zamora, M.; Adan-Castro, E.; Siqueiros-Marquez, L.; Martinez de la Escalera, G.; Clapp, C. The spike protein of SARS-CoV-2 induces endothelial inflammation through integrin α5β1 and NF-κB signaling. J Biol Chem 2022, 298, 101695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Banks, W.A.; Sharma, P.; Bullock, K.M.; Hansen, K.M.; Ludwig, N.; Whiteside, T.L. Transport of Extracellular Vesicles across the Blood-Brain Barrier: Brain Pharmacokinetics and Effects of Inflammation. Int J Mol Sci 2020, 21, 4407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.Y.; Syed, A.M.; MacMillan, P.; Rocheleau, J.V.; Chan, W.C.W. Flow Rate Affects Nanoparticle Uptake into Endothelial Cells. Adv Mater 2020, 32, e1906274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buzhdygan, T.P.; DeOre, B.J.; Baldwin-Leclair, A.; Bullock, T.A.; McGary, H.M.; Khan, J.A.; Razmpour, R.; Hale, J.F.; Galie, P.A.; Potula, R.; et al. The SARS-CoV-2 spike protein alters barrier function in 2D static and 3D microfluidic in-vitro models of the human blood-brain barrier. Neurobiol Dis 2020, 146, 105131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asandei, A.; Mereuta, L.; Schiopu, I.; Park, J.; Seo, C.H.; Park, Y.; Luchian, T. Non-Receptor-Mediated Lipid Membrane Permeabilization by the SARS-CoV-2 Spike Protein S1 Subunit. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces 2020, 12, 55649–55658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malhotra, A. Curing the pandemic of misinformation on COVID-19 mRNA vaccines through real evidence-based medicine - Part 1. Journal of Insulin Resistance 2022, 5, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gill, J.R.; Tashjian, R.; Duncanson, E. Autopsy Histopathologic Cardiac Findings in 2 Adolescents Following the Second COVID-19 Vaccine Dose. Archives of Pathology & Laboratory Medicine 2022, 146, 925–929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diaz, G.A.; Parsons, G.T.; Gering, S.K.; Meier, A.R.; Hutchinson, I.V.; Robicsek, A. Myocarditis and Pericarditis After Vaccination for COVID-19. JAMA 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karlstad, Ø.; Hovi, P.; Husby, A.; Härkänen, T.; Selmer, R.M.; Pihlström, N.; Hansen, J.V.; Nohynek, H.; Gunnes, N.; Sundström, A.; et al. SARS-CoV-2 Vaccination and Myocarditis in a Nordic Cohort Study of 23 Million Residents. JAMA Cardiology 2022, 7, 600–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patone, M.; Mei, X.W.; Handunnetthi, L.; Dixon, S.; Zaccardi, F.; Shankar-Hari, M.; Watkinson, P.; Khunti, K.; Harnden, A.; Coupland, C.A.C.; et al. Risks of myocarditis, pericarditis, and cardiac arrhythmias associated with COVID-19 vaccination or SARS-CoV-2 infection. Nat Med 2022, 28, 410–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kracalik, I.; Oster, M.E.; Broder, K.R.; Cortese, M.M.; Glover, M.; Shields, K.; Creech, C.B.; Romanson, B.; Novosad, S.; Soslow, J.; et al. Outcomes at least 90 days since onset of myocarditis after mRNA COVID-19 vaccination in adolescents and young adults in the USA: a follow-up surveillance study. The Lancet Child & Adolescent Health, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mansanguan, S.; Charunwatthana, P.; Piyaphanee, W.; Dechkhajorn, W.; Poolcharoen, A.; Mansanguan, C. Cardiovascular Manifestation of the BNT162b2 mRNA COVID-19 Vaccine in Adolescents. Tropical Medicine and Infectious Disease 2022, 7, 196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tai, W.; He, L.; Zhang, X.; Pu, J.; Voronin, D.; Jiang, S.; Zhou, Y.; Du, L. Characterization of the receptor-binding domain (RBD) of 2019 novel coronavirus: implication for development of RBD protein as a viral attachment inhibitor and vaccine. Cell Mol Immunol 2020, 17, 613–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, C.B.; Farzan, M.; Chen, B.; Choe, H. Mechanisms of SARS-CoV-2 entry into cells. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2022, 23, 3–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shin, Y.-H.; Jeong, K.; Lee, J.; Lee, H.J.; Yim, J.; Kim, J.; Kim, S.; Park, S.B. Inhibition of ACE2-Spike Interaction by an ACE2 Binder Suppresses SARS-CoV-2 Entry. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl 2022, 61, e202115695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Flores, D.; Zepeda-Cervantes, J.; Cruz-Reséndiz, A.; Aguirre-Sampieri, S.; Sampieri, A.; Vaca, L. SARS-CoV-2 Vaccines Based on the Spike Glycoprotein and Implications of New Viral Variants. Front Immunol 2021, 12, 701501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Read, A.F.; Baigent, S.J.; Powers, C.; Kgosana, L.B.; Blackwell, L.; Smith, L.P.; Kennedy, D.A.; Walkden-Brown, S.W.; Nair, V.K. Imperfect Vaccination Can Enhance the Transmission of Highly Virulent Pathogens. PLOS Biology 2015, 13, e1002198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lyngse, F.P.; Kirkeby, C.T.; Denwood, M.; Christiansen, L.E.; Mølbak, K.; Møller, C.H.; Skov, R.L.; Krause, T.G.; Rasmussen, M.; Sieber, R.N.; et al. Household transmission of SARS-CoV-2 Omicron variant of concern subvariants BA.1 and BA.2 in Denmark. Nat Commun 2022, 13, 5760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- López-Cortés, G.I.; Palacios-Pérez, M.; Zamudio, G.S.; Veledíaz, H.F.; Ortega, E.; José, M.V. Neutral evolution test of the spike protein of SARS-CoV-2 and its implications in the binding to ACE2. Sci Rep 2021, 11, 18847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gupta, D.; Sharma, P.; Singh, M.; Kumar, M.; Ethayathulla, A.S.; Kaur, P. Structural and functional insights into the spike protein mutations of emerging SARS-CoV-2 variants. Cell Mol Life Sci 2021, 78, 7967–7989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fertig, T.E.; Chitoiu, L.; Marta, D.S.; Ionescu, V.-S.; Cismasiu, V.B.; Radu, E.; Angheluta, G.; Dobre, M.; Serbanescu, A.; Hinescu, M.E.; et al. Vaccine mRNA Can Be Detected in Blood at 15 Days Post-Vaccination. Biomedicines 2022, 10, 1538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bahl, K.; Senn, J.J.; Yuzhakov, O.; Bulychev, A.; Brito, L.A.; Hassett, K.J.; Laska, M.E.; Smith, M.; Almarsson, Ö.; Thompson, J.; et al. Preclinical and Clinical Demonstration of Immunogenicity by mRNA Vaccines against H10N8 and H7N9 Influenza Viruses. Molecular Therapy 2017, 25, 1316–1327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanna, N.; Heffes-Doon, A.; Lin, X.; Manzano De Mejia, C.; Botros, B.; Gurzenda, E.; Nayak, A. Detection of Messenger RNA COVID-19 Vaccines in Human Breast Milk. JAMA Pediatrics 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nuovo, G.J.; Magro, C.; Shaffer, T.; Awad, H.; Suster, D.; Mikhail, S.; He, B.; Michaille, J.-J.; Liechty, B.; Tili, E. Endothelial cell damage is the central part of COVID-19 and a mouse model induced by injection of the S1 subunit of the spike protein. Annals of Diagnostic Pathology 2021, 51, 151682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raghavan, S.; Kenchappa, D.B.; Leo, M.D. SARS-CoV-2 Spike Protein Induces Degradation of Junctional Proteins That Maintain Endothelial Barrier Integrity. Front Cardiovasc Med 2021, 8, 687783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, Y.; Zhang, J.; Schiavon, C.R.; He, M.; Chen, L.; Shen, H.; Zhang, Y.; Yin, Q.; Cho, Y.; Andrade, L.; et al. SARS-CoV-2 Spike Protein Impairs Endothelial Function via Downregulation of ACE 2. Circulation Research 2021, 128, 1323–1326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serviente, C.; Matias, A.; Erol, M.E.; Calderone, M.; Layec, G. The Influence of Covid-19-Based mRNA Vaccines on Measures of Conduit Artery and Microvascular Endothelial Function. The FASEB Journal 2022, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castanares-Zapatero, D.; Chalon, P.; Kohn, L.; Dauvrin, M.; Detollenaere, J.; Maertens de Noordhout, C.; Primus-de Jong, C.; Cleemput, I.; Van den Heede, K. Pathophysiology and mechanism of long COVID: a comprehensive review. Ann Med 2022, 54, 1473–1487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crook, H.; Raza, S.; Nowell, J.; Young, M.; Edison, P. Long covid-mechanisms, risk factors, and management. BMJ 2021, 374, n1648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Y.; Xu, E.; Bowe, B.; Al-Aly, Z. Long-term cardiovascular outcomes of COVID-19. Nat Med 2022, 28, 583–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raman, B.; Bluemke, D.A.; Lüscher, T.F.; Neubauer, S. Long COVID: post-acute sequelae of COVID-19 with a cardiovascular focus. European Heart Journal 2022, 43, 1157–1172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yonker, L.M.; Swank, Z.; Bartsch, Y.C.; Burns, M.D.; Kane, A.; Boribong, B.P.; Davis, J.P.; Loiselle, M.; Novak, T.; Senussi, Y.; et al. Circulating Spike Protein Detected in Post–COVID-19 mRNA Vaccine Myocarditis. Circulation 0. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Liu, Y.; Wang, X.; Yang, L.; Li, H.; Wang, Y.; Liu, M.; Zhao, X.; Xie, Y.; Yang, Y.; et al. SARS-CoV-2 binds platelet ACE2 to enhance thrombosis in COVID-19. J Hematol Oncol 2020, 120–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grobbelaar, L.M.; Venter, C.; Vlok, M.; Ngoepe, M.; Laubscher, G.J.; Lourens, P.J.; Steenkamp, J.; Kell, D.B.; Pretorius, E. SARS-CoV-2 spike protein S1 induces fibrin(ogen) resistant to fibrinolysis: implications for microclot formation in COVID-19. Bioscience Reports 2021, 41, BSR20210611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nyström, S.; Hammarström, P. Amyloidogenesis of SARS-CoV-2 Spike Protein. J Am Chem Soc 2022, 144, 8945–8950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montgomery, J.; Ryan, M.; Engler, R.; Hoffman, D.; McClenathan, B.; Collins, L.; Loran, D.; Hrncir, D.; Herring, K.; Platzer, M.; et al. Myocarditis Following Immunization With mRNA COVID-19 Vaccines in Members of the US Military. JAMA Cardiology 2021, 6, 1202–1206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakraborty, C.; Bhattacharya, M.; Sharma, A.R. Present variants of concern and variants of interest of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2: Their significant mutations in S-glycoprotein, infectivity, re-infectivity, immune escape and vaccines activity. Reviews in Medical Virology 2022, 32, e2270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harvey, W.T.; Carabelli, A.M.; Jackson, B.; Gupta, R.K.; Thomson, E.C.; Harrison, E.M.; Ludden, C.; Reeve, R.; Rambaut, A.; Peacock, S.J.; et al. SARS-CoV-2 variants, spike mutations and immune escape. Nat Rev Microbiol 2021, 19, 409–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collier, A.Y.; Miller, J.; Hachmann, N.P.; McMahan, K.; Liu, J.; Bondzie, E.A.; Gallup, L.; Rowe, M.; Schonberg, E.; Thai, S.; et al. Immunogenicity of BA.5 Bivalent mRNA Vaccine Boosters. N Engl J Med 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, J.-H.; Patel, N.; Haupt, R.; Zhou, H.; Weston, S.; Hammond, H.; Logue, J.; Portnoff, A.D.; Norton, J.; Guebre-Xabier, M.; et al. SARS-CoV-2 spike glycoprotein vaccine candidate NVX-CoV2373 immunogenicity in baboons and protection in mice. Nat Commun 2021, 12, 372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakraborty, C.; Sharma, A.R.; Bhattacharya, M.; Lee, S.-S. A Detailed Overview of Immune Escape, Antibody Escape, Partial Vaccine Escape of SARS-CoV-2 and Their Emerging Variants With Escape Mutations. Front Immunol 2022, 13, 801522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, Y.; Shang, J.; Sun, S.; Tai, W.; Chen, J.; Geng, Q.; He, L.; Chen, Y.; Wu, J.; Shi, Z.; et al. Molecular Mechanism for Antibody-Dependent Enhancement of Coronavirus Entry. J Virol 2020, 94, e02015-19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Regev-Yochay, G.; Gonen, T.; Gilboa, M.; Mandelboim, M.; Indenbaum, V.; Amit, S.; Meltzer, L.; Asraf, K.; Cohen, C.; Fluss, R.; et al. Efficacy of a Fourth Dose of Covid-19 mRNA Vaccine against Omicron. N Engl J Med 2022, 386, 1377–1380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Wang, J.; Xu, J.; Xia, H.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, C.; Chen, W.; Zhang, H.; Liu, Q.; Zhu, R.; et al. Comprehensive investigations revealed consistent pathophysiological alterations after vaccination with COVID-19 vaccines. Cell Discov 2021, 7, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iddir, M.; Brito, A.; Dingeo, G.; Fernandez Del Campo, S.S.; Samouda, H.; La Frano, M.R.; Bohn, T. Strengthening the Immune System and Reducing Inflammation and Oxidative Stress through Diet and Nutrition: Considerations during the COVID-19 Crisis. Nutrients 2020, 12, 1562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakeshbandi, M.; Maini, R.; Daniel, P.; Rosengarten, S.; Parmar, P.; Wilson, C.; Kim, J.M.; Oommen, A.; Mecklenburg, M.; Salvani, J.; et al. The impact of obesity on COVID-19 complications: a retrospective cohort study. Int J Obes 2020, 44, 1832–1837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apicella, M.; Campopiano, M.C.; Mantuano, M.; Mazoni, L.; Coppelli, A.; Del Prato, S. COVID-19 in people with diabetes: understanding the reasons for worse outcomes. The Lancet Diabetes & Endocrinology 2020, 8, 782–792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- E, L.; C, L.; C, F.; E, O.; Js, C.; F, C.; Mf, S.; C, M.; M, B.; E, D.; et al. A Machine-Generated View of the Role of Blood Glucose Levels in the Severity of COVID-19. Frontiers in public health 2021, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Em, H.; Lm, S.; A, M.; S, B.; J, S.; Ja, R.; Cp, H.; Ar, S. Fruit and vegetable consumption and its relation to markers of inflammation and oxidative stress in adolescents. Journal of the American Dietetic Association 2009, 109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yc, C.; Jm, S.; Wl, H.; Yc, H. Polyphenols and Oxidative Stress in Atherosclerosis-Related Ischemic Heart Disease and Stroke. Oxidative medicine and cellular longevity 2017, 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- A, S.; G, S. Protective Role of Polyphenols against Vascular Inflammation, Aging and Cardiovascular Disease. Nutrients 2018, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Y, B.; Tw, H. Role of the microbiota in immunity and inflammation. Cell 2014, 157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeoh, Y.K.; Zuo, T.; Lui, G.C.-Y.; Zhang, F.; Liu, Q.; Li, A.Y.; Chung, A.C.; Cheung, C.P.; Tso, E.Y.; Fung, K.S.; et al. Gut microbiota composition reflects disease severity and dysfunctional immune responses in patients with COVID-19. Gut 2021, 70, 698–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- T, Z.; Q, L.; F, Z.; Gc, L.; Ey, T.; Yk, Y.; Z, C.; Ss, B.; Fk, C.; Pk, C.; et al. Depicting SARS-CoV-2 faecal viral activity in association with gut microbiota composition in patients with COVID-19. Gut 2021, 70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, C.; Viana, S.D.; Reis, F. Gut Microbiota Dysbiosis–Immune Hyperresponse–Inflammation Triad in Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19): Impact of Pharmacological and Nutraceutical Approaches. Microorganisms 2020, 8, 1514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, C.; van Haperen, R.; Gutiérrez-Álvarez, J.; Li, W.; Okba, N.M.A.; Albulescu, I.; Widjaja, I.; van Dieren, B.; Fernandez-Delgado, R.; Sola, I.; et al. A conserved immunogenic and vulnerable site on the coronavirus spike protein delineated by cross-reactive monoclonal antibodies. Nat Commun 2021, 12, 1715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, F. Structure, Function, and Evolution of Coronavirus Spike Proteins. Annu Rev Virol 2016, 3, 237–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pollard, T.D. A Guide to Simple and Informative Binding Assays. Mol Biol Cell 2010, 21, 4061–4067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baer, A.; Kehn-Hall, K. Viral Concentration Determination Through Plaque Assays: Using Traditional and Novel Overlay Systems. J Vis Exp 2014, 52065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puren, A.; Gerlach, J.L.; Weigl, B.H.; Kelso, D.M.; Domingo, G.J. Laboratory operations, specimen processing, and handling for viral load testing and surveillance. J Infect Dis 2010, 201 Suppl 1, S27–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gillette, J.R. Problems in Correlating InVitro and InVivo Studies of Drug Metabolism. In Pharmacokinetics: A Modern View; Benet, L.Z., Levy, G., Ferraiolo, B.L., Eds.; Springer: Boston, MA, USA, 1984; pp. 235–252. ISBN 978-1-4613-2799-8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faraoni, D.; Schaefer, S.T. Randomized controlled trials vs. observational studies: why not just live together? BMC Anesthesiol 2016, 16, 102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, A.; Bashir, M.S.; Joyce, K.; Rashid, H.; Laher, I.; Elshazly, S. An Update on COVID-19 Vaccine Induced Thrombotic Thrombocytopenia Syndrome and Some Management Recommendations. Molecules 2021, 26, 5004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, G.; Couture, F.; Kwiatkowska, A. The Path to Therapeutic Furin Inhibitors: From Yeast Pheromones to SARS-CoV-2. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2022, 23, 3435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, Y.-W.; Chao, T.-L.; Li, C.-L.; Chiu, M.-F.; Kao, H.-C.; Wang, S.-H.; Pang, Y.-H.; Lin, C.-H.; Tsai, Y.-M.; Lee, W.-H.; et al. Furin Inhibitors Block SARS-CoV-2 Spike Protein Cleavage to Suppress Virus Production and Cytopathic Effects. Cell Reports 2020, 33, 108254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, C.; Zheng, M.; Yang, Y.; Gu, X.; Yang, K.; Li, M.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, Q.; Zhang, P.; Wang, Y.; et al. Furin: A Potential Therapeutic Target for COVID-19. iScience 2020, 23, 101642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mykytyn, A.Z.; Breugem, T.I.; Riesebosch, S.; Schipper, D.; van den Doel, P.B.; Rottier, R.J.; Lamers, M.M.; Haagmans, B.L. SARS-CoV-2 entry into human airway organoids is serine protease-mediated and facilitated by the multibasic cleavage site. eLife 2021, 10, e64508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosendal, E.; Mihai, I.S.; Becker, M.; Das, D.; Frängsmyr, L.; Persson, B.D.; Rankin, G.D.; Gröning, R.; Trygg, J.; Forsell, M.; et al. Serine Protease Inhibitors Restrict Host Susceptibility to SARS-CoV-2 Infections. mBio 2022, 13, e0089222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shulla, A.; Heald-Sargent, T.; Subramanya, G.; Zhao, J.; Perlman, S.; Gallagher, T. A transmembrane serine protease is linked to the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus receptor and activates virus entry. J Virol 2011, 85, 873–882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, J.; Hou, Y.; Ge, S.; Wang, X.; Wang, J.; Hu, T.; Lv, Y.; He, H.; Wang, C. Screened antipsychotic drugs inhibit SARS-CoV-2 binding with ACE2 in vitro. Life Sci 2021, 266, 118889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Su, S.; Chen, J.; Wang, Y.; Wong, L.M.; Zhu, Z.; Jiang, G.; Liu, P. Lenalidomide downregulates ACE2 protein abundance to alleviate infection by SARS-CoV-2 spike protein conditioned pseudoviruses. Sig Transduct Target Ther 2021, 6, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramadan, A.A.; Mayilsamy, K.; McGill, A.R.; Ghosh, A.; Giulianotti, M.A.; Donow, H.M.; Mohapatra, S.S.; Mohapatra, S.; Chandran, B.; Deschenes, R.J.; et al. Inhibition of SARS-CoV-2 spike protein palmitoylation reduces virus infectivity. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajpoot, S.; Ohishi, T.; Kumar, A.; Pan, Q.; Banerjee, S.; Zhang, K.Y.J.; Baig, M.S. A Novel Therapeutic Peptide Blocks SARS-CoV-2 Spike Protein Binding with Host Cell ACE2 Receptor. Drugs R D 2021, 21, 273–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kruse, K.B.; Brodsky, J.L.; McCracken, A.A. Autophagy: an ER protein quality control process. Autophagy 2006, 2, 135–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- S, H.; K, H. Modifiable Host Factors for the Prevention and Treatment of COVID-19: Diet and Lifestyle/Diet and Lifestyle Factors in the Prevention of COVID-19. Nutrients 2022, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Losso, J.N.; Losso, M.N.; Toc, M.; Inungu, J.N.; Finley, J.W. The Young Age and Plant-Based Diet Hypothesis for Low SARS-CoV-2 Infection and COVID-19 Pandemic in Sub-Saharan Africa. Plant Foods Hum Nutr 2021, 76, 270–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, R.B. Low dietary sodium potentially mediates COVID-19 prevention associated with whole-food plant-based diets. Br J Nutr 2022, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De, R.; Dutta, S. Role of the Microbiome in the Pathogenesis of COVID-19. Front Cell Infect Microbiol 2022, 12, 736397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramakrishnan, R.K.; Kashour, T.; Hamid, Q.; Halwani, R.; Tleyjeh, I.M. Unraveling the Mystery Surrounding Post-Acute Sequelae of COVID-19. Front Immunol 2021, 12, 686029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haran, J.P.; Bradley, E.; Zeamer, A.L.; Cincotta, L.; Salive, M.-C.; Dutta, P.; Mutaawe, S.; Anya, O.; Meza-Segura, M.; Moormann, A.M.; et al. Inflammation-type dysbiosis of the oral microbiome associates with the duration of COVID-19 symptoms and long COVID. JCI Insight 2021, 6, e152346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Proal, A.D.; VanElzakker, M.B. Long COVID or Post-acute Sequelae of COVID-19 (PASC): An Overview of Biological Factors That May Contribute to Persistent Symptoms. Front Microbiol 2021, 12, 698169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wastyk, H.C.; Fragiadakis, G.K.; Perelman, D.; Dahan, D.; Merrill, B.D.; Yu, F.B.; Topf, M.; Gonzalez, C.G.; Treuren, W.V.; Han, S.; et al. Gut-microbiota-targeted diets modulate human immune status. Cell 2021, 184, 4137–4153.e14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rossi, G.A.; Sacco, O.; Mancino, E.; Cristiani, L.; Midulla, F. Differences and similarities between SARS-CoV and SARS-CoV-2: spike receptor-binding domain recognition and host cell infection with support of cellular serine proteases. Infection 2020, 48, 665–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petersen, E.; Koopmans, M.; Go, U.; Hamer, D.H.; Petrosillo, N.; Castelli, F.; Storgaard, M.; Khalili, S.A.; Simonsen, L. Comparing SARS-CoV-2 with SARS-CoV and influenza pandemics. The Lancet Infectious Diseases 2020, 20, e238–e244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffmann, M.; Kleine-Weber, H.; Pöhlmann, S. A Multibasic Cleavage Site in the Spike Protein of SARS-CoV-2 Is Essential for Infection of Human Lung Cells. Mol Cell 2020, 78, 779–784.e5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coutard, B.; Valle, C.; de Lamballerie, X.; Canard, B.; Seidah, N.G.; Decroly, E. The spike glycoprotein of the new coronavirus 2019-nCoV contains a furin-like cleavage site absent in CoV of the same clade. Antiviral Res 2020, 176, 104742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffmann, M.; Kleine-Weber, H.; Schroeder, S.; Krüger, N.; Herrler, T.; Erichsen, S.; Schiergens, T.S.; Herrler, G.; Wu, N.-H.; Nitsche, A.; et al. SARS-CoV-2 Cell Entry Depends on ACE2 and TMPRSS2 and Is Blocked by a Clinically Proven Protease Inhibitor. Cell 2020, 181, 271–280.e8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hansen, T.; Titze, U.; Kulamadayil-Heidenreich, N.S.A.; Glombitza, S.; Tebbe, J.J.; Röcken, C.; Schulz, B.; Weise, M.; Wilkens, L. First case of postmortem study in a patient vaccinated against SARS-CoV-2. Int J Infect Dis 2021, 107, 172–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Polack, F.P.; Thomas, S.J.; Kitchin, N.; Absalon, J.; Gurtman, A.; Lockhart, S.; Perez, J.L.; Pérez Marc, G.; Moreira, E.D.; Zerbini, C.; et al. Safety and Efficacy of the BNT162b2 mRNA Covid-19 Vaccine. New England Journal of Medicine 2020, 383, 2603–2615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Corbett, K.S.; Flynn, B.; Foulds, K.E.; Francica, J.R.; Boyoglu-Barnum, S.; Werner, A.P.; Flach, B.; O’Connell, S.; Bock, K.W.; Minai, M.; et al. Evaluation of the mRNA-1273 Vaccine against SARS-CoV-2 in Nonhuman Primates. N Engl J Med 2020, 383, 1544–1555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bos, R.; Rutten, L.; van der Lubbe, J.E.M.; Bakkers, M.J.G.; Hardenberg, G.; Wegmann, F.; Zuijdgeest, D.; de Wilde, A.H.; Koornneef, A.; Verwilligen, A.; et al. Ad26 vector-based COVID-19 vaccine encoding a prefusion-stabilized SARS-CoV-2 Spike immunogen induces potent humoral and cellular immune responses. npj Vaccines 2020, 5, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bangaru, S.; Ozorowski, G.; Turner, H.L.; Antanasijevic, A.; Huang, D.; Wang, X.; Torres, J.L.; Diedrich, J.K.; Tian, J.-H.; Portnoff, A.D.; et al. Structural analysis of full-length SARS-CoV-2 spike protein from an advanced vaccine candidate. Science 2020, 370, 1089–1094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pallesen, J.; Wang, N.; Corbett, K.S.; Wrapp, D.; Kirchdoerfer, R.N.; Turner, H.L.; Cottrell, C.A.; Becker, M.M.; Wang, L.; Shi, W.; et al. Immunogenicity and structures of a rationally designed prefusion MERS-CoV spike antigen. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2017, 114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watanabe, Y.; Mendonça, L.; Allen, E.R.; Howe, A.; Lee, M.; Allen, J.D.; Chawla, H.; Pulido, D.; Donnellan, F.; Davies, H.; et al. Native-like SARS-CoV-2 Spike Glycoprotein Expressed by ChAdOx1 nCoV-19/AZD1222 Vaccine. ACS Cent. Sci. 2021, 7, 594–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Q.; Bao, L.; Mao, H.; Wang, L.; Xu, K.; Yang, M.; Li, Y.; Zhu, L.; Wang, N.; Lv, Z.; et al. Development of an inactivated vaccine candidate for SARS-CoV-2. Science 2020, 369, 77–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, M.; Chamblee, M.; Zhang, Y.; Ye, C.; Dravid, P.; Park, J.-G.; Mahesh, K.; Trivedi, S.; Murthy, S.; Sharma, H.; et al. SARS-CoV-2 prefusion spike protein stabilized by six rather than two prolines is more potent for inducing antibodies that neutralize viral variants of concern. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2022, 119, e2110105119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amanat, F.; Strohmeier, S.; Rathnasinghe, R.; Schotsaert, M.; Coughlan, L.; García-Sastre, A.; Krammer, F. Introduction of Two Prolines and Removal of the Polybasic Cleavage Site Lead to Higher Efficacy of a Recombinant Spike-Based SARS-CoV-2 Vaccine in the Mouse Model. mBio 2021, 12, e02648-20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murza, A.; Dion, S.P.; Boudreault, P.-L.; Désilets, A.; Leduc, R.; Marsault, É. Inhibitors of type II transmembrane serine proteases in the treatment of diseases of the respiratory tract - A review of patent literature. Expert Opin Ther Pat 2020, 30, 807–824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rahman, N.; Basharat, Z.; Yousuf, M.; Castaldo, G.; Rastrelli, L.; Khan, H. Virtual Screening of Natural Products against Type II Transmembrane Serine Protease (TMPRSS2), the Priming Agent of Coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2). Molecules 2020, 25, 2271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Azouz, N.P.; Klingler, A.M.; Callahan, V.; Akhrymuk, I.V.; Elez, K.; Raich, L.; Henry, B.M.; Benoit, J.L.; Benoit, S.W.; Noé, F.; et al. Alpha 1 Antitrypsin is an Inhibitor of the SARS-CoV-2-Priming Protease TMPRSS2. Pathog Immun 2021, 6, 55–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Longo, V.D.; Mattson, M.P. Fasting: Molecular Mechanisms and Clinical Applications. Cell Metab 2014, 19, 181–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bagherniya, M.; Butler, A.E.; Barreto, G.E.; Sahebkar, A. The effect of fasting or calorie restriction on autophagy induction: A review of the literature. Ageing Research Reviews 2018, 47, 183–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brandhorst, S.; Longo, V.D. Protein Quantity and Source, Fasting-Mimicking Diets, and Longevity. Advances in Nutrition 2019, 10, S340–S350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shuvayeva, G.; Bobak, Y.; Igumentseva, N.; Titone, R.; Morani, F.; Stasyk, O.; Isidoro, C. Single amino acid arginine deprivation triggers prosurvival autophagic response in ovarian carcinoma SKOV3. Biomed Res Int 2014, 2014, 505041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishimura, K.; Shiina, R.; Kashiwagi, K.; Igarashi, K. Decrease in Polyamines with Aging and Their Ingestion from Food and Drink. The Journal of Biochemistry 2006, 139, 81–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisenberg, T.; Knauer, H.; Schauer, A.; Büttner, S.; Ruckenstuhl, C.; Carmona-Gutierrez, D.; Ring, J.; Schroeder, S.; Magnes, C.; Antonacci, L.; et al. Induction of autophagy by spermidine promotes longevity. Nat Cell Biol 2009, 11, 1305–1314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Summers, C.M.; Valentine, R.J. Acute Heat Exposure Alters Autophagy Signaling in C2C12 Myotubes. Frontiers in Physiology 2020, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McCormick, J.J.; Dokladny, K.; Moseley, P.L.; Kenny, G.P. Autophagy and heat: a potential role for heat therapy to improve autophagic function in health and disease. Journal of Applied Physiology 2021, 130, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Arcy, M.S. A review of biologically active flavonoids as inducers of autophagy and apoptosis in neoplastic cells and as cytoprotective agents in non-neoplastic cells. Cell Biology International 2022, 46, 1179–1195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hasima, N.; Ozpolat, B. Regulation of autophagy by polyphenolic compounds as a potential therapeutic strategy for cancer. Cell Death Dis 2014, 5, e1509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, S.-R.; Fu, Y.-S.; Tsai, M.-J.; Cheng, H.; Weng, C.-F. Natural Compounds from Herbs that can Potentially Execute as Autophagy Inducers for Cancer Therapy. Int J Mol Sci 2017, 18, 1412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pietrocola, F.; Malik, S.A.; Mariño, G.; Vacchelli, E.; Senovilla, L.; Chaba, K.; Niso-Santano, M.; Maiuri, M.C.; Madeo, F.; Kroemer, G. Coffee induces autophagy in vivo. Cell Cycle 2014, 13, 1987–1994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferraresi, A.; Titone, R.; Follo, C.; Castiglioni, A.; Chiorino, G.; Dhanasekaran, D.N.; Isidoro, C. The protein restriction mimetic Resveratrol is an autophagy inducer stronger than amino acid starvation in ovarian cancer cells. Molecular Carcinogenesis 2017, 56, 2681–2691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, G.; Wu, Z.; Shang, J.; Xie, Z.; Chen, C.; zhang, C. The effects of metformin on autophagy. Biomedicine & Pharmacotherapy 2021, 137, 111286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, J.; Nie, J.; Chen, Z.; Wang, X.; Hu, H.; Xu, J.; Lu, J.; Ma, L.; Ji, H.; Yuan, J.; et al. Cold exposure-induced endoplasmic reticulum stress regulates autophagy through the SIRT2/FoxO1 signaling pathway. Journal of Cellular Physiology 2022, 237, 3960–3970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yau, W.W.; Wong, K.A.; Zhou, J.; Thimmukonda, N.K.; Wu, Y.; Bay, B.-H.; Singh, B.K.; Yen, P.M. Chronic cold exposure induces autophagy to promote fatty acid oxidation, mitochondrial turnover, and thermogenesis in brown adipose tissue. iScience 2021, 24, 102434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.-C.; Zhang, S.; Du, T.-Y.; Wang, B.; Sun, X.-Q. Hyperbaric oxygen preconditioning reduces ischemia–reperfusion injury by stimulating autophagy in neurocyte. Brain Research 2010, 1323, 149–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, P.; Xu, W.; Zhao, X.; Zhang, C.; Lin, X.; Gong, M.; Fu, Z. Ozone induces autophagy by activating PPARγ/mTOR in rat chondrocytes treated with IL-1β. Journal of Orthopaedic Surgery and Research 2022, 17, 351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mojtabavi, H.; Saghazadeh, A.; Rezaei, N. Interleukin-6 and severe COVID-19: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur Cytokine Netw 2020, 31, 44–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kell, D.B.; Laubscher, G.J.; Pretorius, E. A central role for amyloid fibrin microclots in long COVID/PASC: origins and therapeutic implications. Biochem J 2022, 479, 537–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pretorius, E.; Vlok, M.; Venter, C.; Bezuidenhout, J.A.; Laubscher, G.J.; Steenkamp, J.; Kell, D.B. Persistent clotting protein pathology in Long COVID/Post-Acute Sequelae of COVID-19 (PASC) is accompanied by increased levels of antiplasmin. Cardiovascular Diabetology 2021, 20, 172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pretorius, E.; Venter, C.; Laubscher, G.J.; Kotze, M.J.; Oladejo, S.O.; Watson, L.R.; Rajaratnam, K.; Watson, B.W.; Kell, D.B. Prevalence of symptoms, comorbidities, fibrin amyloid microclots and platelet pathology in individuals with Long COVID/Post-Acute Sequelae of COVID-19 (PASC). Cardiovasc Diabetol 2022, 21, 148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, J.C.; Hawley, H.B. Vaccine-Associated Thrombocytopenia and Thrombosis: Venous Endotheliopathy Leading to Venous Combined Micro-Macrothrombosis. Medicina 2021, 57, 1163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mainous, A.G.; Rooks, B.J.; Orlando, F.A. The Impact of Initial COVID-19 Episode Inflammation Among Adults on Mortality Within 12 Months Post-hospital Discharge. Frontiers in Medicine 2022, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aydınyılmaz, F.; Aksakal, E.; Pamukcu, H.E.; Aydemir, S.; Doğan, R.; Saraç, İ.; Aydın, S.Ş.; Kalkan, K.; Gülcü, O.; Tanboğa, İ.H. Significance of MPV, RDW and PDW with the Severity and Mortality of COVID-19 and Effects of Acetylsalicylic Acid Use. Clin Appl Thromb Hemost 2021, 27, 10760296211048808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bianconi, V.; Violi, F.; Fallarino, F.; Pignatelli, P.; Sahebkar, A.; Pirro, M. Is Acetylsalicylic Acid a Safe and Potentially Useful Choice for Adult Patients with COVID-19? Drugs 2020, 80, 1383–1396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clissold, S.P. Aspirin and Related Derivatives of Salicylic Acid. Drugs 1986, 32, 8–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Storstein, O.; Nitter-Hauge, S.; Enge, I. Thromboembolic Complications in Coronary Angiography: Prevention with Acetyl-Salicylic Acid. Acta Radiologica. Diagnosis 1977, 18, 555–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Østerud, B.; Brox, J.H. The clotting time of whole blood in plastic tubes: The influence of exercise, prostacyclin and acetylsalicylic acid. Thrombosis Research 1983, 29, 425–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fujita, M.; Nomura, K.; Hong, K.; Ito, Y.; Asada, A.; Nishimuro, S. Purification and Characterization of a Strong Fibrinolytic Enzyme (Nattokinase) in the Vegetable Cheese Natto, a Popular Soybean Fermented Food in Japan. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications 1993, 197, 1340–1347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hsu, R.-L.; Lee, K.-T.; Wang, J.-H.; Lee, L.Y.-L.; Chen, R.P.-Y. Amyloid-Degrading Ability of Nattokinase from Bacillus subtilis Natto. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2009, 57, 503–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oba, M.; Rongduo, W.; Saito, A.; Okabayashi, T.; Yokota, T.; Yasuoka, J.; Sato, Y.; Nishifuji, K.; Wake, H.; Nibu, Y.; et al. Natto extract, a Japanese fermented soybean food, directly inhibits viral infections including SARS-CoV-2 in vitro. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications 2021, 570, 21–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tanikawa, T.; Kiba, Y.; Yu, J.; Hsu, K.; Chen, S.; Ishii, A.; Yokogawa, T.; Suzuki, R.; Inoue, Y.; Kitamura, M. Degradative Effect of Nattokinase on Spike Protein of SARS-CoV-2. Molecules 2022, 27, 5405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kurosawa, Y.; Nirengi, S.; Homma, T.; Esaki, K.; Ohta, M.; Clark, J.F.; Hamaoka, T. A single-dose of oral nattokinase potentiates thrombolysis and anti-coagulation profiles. Sci Rep 2015, 5, 11601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Loh, E.-W. Dose-response Study a Glucoside- and Rutinoside-rich Crude Material in Relieving Side Effects of COVID-19 Vaccines. Available online: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT05387252 (accessed on 2022).

- University of Oxford. Characterisation of the Effects of Spermidine, a Nutrition Supplement, on the Immune Memory Response to Coronavirus Vaccine in Older People. Available online: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT05421546 (accessed on 2022).

- Université de Sherbrooke. Modulation of Immune Responses to COVID-19 Vaccination by an Intervention on the Gut Microbiota: a Randomized Controlled Trial. Available online: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT05195151 (accessed on 2022).

- AB Biotek. Efficacy and Tolerability of a Nutritional Supplementation With ABBC-1, a Symbiotic Combination of Beta-glucans and Selenium and Zinc Enriched Probiotics, in Volunteers Receiving the Influenza or the Covid-19 Vaccines. Available online: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT04798677 (accessed on 2022).

- Maastricht University Medical Center. The Effect of Plant Stanol Ester Consumption on the Vaccination Response to a COVID-19 Vaccine. Available online: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT04844346 (accessed on 2022).

- Saxe, G. Multicenter Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled RCT of Fomitopsis Officinalis/Trametes Versicolor for COVID-19. Available online: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT04951336 (accessed on 2022).

- Engındenız, Z. Evaluation of Deltoid Muscle Exercises on Injection Site and Arm Pain After Pfizer - BioNTech (BNT162b2) COVID - 19 Vaccination, A Randomized Controlled Study. Available online: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT05157230 (accessed on 2022).

- Sanchez, J. Augmentation of Immune Response to COVID-19 mRNA Vaccination Through Osteopathic Manipulative Treatment Including Lymphatic Pumps. Available online: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT04928456 (accessed on 2022).

- Rowan University. Lymphatic Osteopathic Manipulative Medicine to Enhance COVID-19 Vaccination Efficacy. Available online: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT05069636 (accessed on 2022).

- Bartley, J. Vaccination Efficacy With Metformin in Older Adults: A Pilot Study. Available online: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT03996538 (accessed on 2020).

- Karanja, P. S. Iron and Vaccine-preventable Viral Disease. Available online: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT04915820 (accessed on 2021).

- Materia Medica Holding. Multicenter, Double-blind, Placebo-controlled, Randomized, Parallel-group Clinical Trial to Evaluate the Efficacy and Safety of Ergoferon as Non-specific COVID-19 Prevention During Vaccination Against SARS-CoV-2. Available online: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT05069649 (accessed on 2022).

- Gnessi, L. COVID-19 Vaccination in Subjects With Obesity: Impact of Metabolic Health and the Role of a Ketogenic Diet. Available online: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT05163743 (accessed on 2021).

- Wang, A. X. Impact of Immunosuppression Adjustment on the Immune Response to SARS-CoV-2 mRNA Vaccination in Kidney Transplant Recipients (ADIVKT). Available online: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT05060991 (accessed on 2022).

- University Hospital Inselspital, Berne. Registry Study for COVID19 Vaccination Efficacy in Patients With a Treatment History of Rituximab. Available online: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT04877496 (accessed on 2021).

- Webster, K.E.; O’Byrne, L.; MacKeith, S.; Philpott, C.; Hopkins, C.; Burton, M.J. Interventions for the prevention of persistent post-COVID-19 olfactory dysfunction. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behera, P.; Patro, B.K.; Singh, A.K.; Chandanshive, P.D.; S R, R.; Pradhan, S.K.; Pentapati, S.S.K.; Batmanabane, G.; Mohapatra, P.R.; Padhy, B.M.; et al. Role of ivermectin in the prevention of SARS-CoV-2 infection among healthcare workers in India: A matched case-control study. PLoS One 2021, 16, e0247163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaidi, A.K.; Dehgani-Mobaraki, P. The mechanisms of action of ivermectin against SARS-CoV-2—an extensive review. J Antibiot (Tokyo) 2022, 75, 60–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caly, L.; Druce, J.D.; Catton, M.G.; Jans, D.A.; Wagstaff, K.M. The FDA-approved drug ivermectin inhibits the replication of SARS-CoV-2 in vitro. Antiviral Res 2020, 178, 104787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bryant, A.; Lawrie, T.A.; Dowswell, T.; Fordham, E.J.; Mitchell, S.; Hill, S.R.; Tham, T.C. Ivermectin for Prevention and Treatment of COVID-19 Infection: A Systematic Review, Meta-analysis, and Trial Sequential Analysis to Inform Clinical Guidelines. Am J Ther 2021, 28, e434–e460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kory, P.; Meduri, G.U.; Varon, J.; Iglesias, J.; Marik, P.E. Review of the Emerging Evidence Demonstrating the Efficacy of Ivermectin in the Prophylaxis and Treatment of COVID-19. Am J Ther 2021, 28, e299–e318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Griesel, M.; Wagner, C.; Mikolajewska, A.; Stegemann, M.; Fichtner, F.; Metzendorf, M.-I.; Nair, A.A.; Daniel, J.; Fischer, A.-L.; Skoetz, N. Inhaled corticosteroids for the treatment of COVID-19. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2022, 3, CD015125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Paassen, J.; Vos, J.S.; Hoekstra, E.M.; Neumann, K.M.I.; Boot, P.C.; Arbous, S.M. Corticosteroid use in COVID-19 patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis on clinical outcomes. Crit Care 2020, 24, 696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goel, N.; Goyal, N.; Nagaraja, R.; Kumar, R. Systemic corticosteroids for management of ‘long-COVID’: an evaluation after 3 months of treatment. Monaldi Archives for Chest Disease 2022, 92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morán Blanco, J.I.; Alvarenga Bonilla, J.A.; Homma, S.; Suzuki, K.; Fremont-Smith, P.; Villar Gómez de las Heras, K. Antihistamines and azithromycin as a treatment for COVID-19 on primary health care – A retrospective observational study in elderly patients. Pulm Pharmacol Ther 2021, 67, 101989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinto, M.D.; Lambert, N.; Downs, C.A.; Abrahim, H.; Hughes, T.D.; Rahmani, A.M.; Burton, C.W.; Chakraborty, R. Antihistamines for Postacute Sequelae of SARS-CoV-2 Infection. The Journal for Nurse Practitioners 2022, 18, 335–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reznikov, L.R.; Norris, M.H.; Vashisht, R.; Bluhm, A.P.; Li, D.; Liao, Y.-S.J.; Brown, A.; Butte, A.J.; Ostrov, D.A. Identification of antiviral antihistamines for COVID-19 repurposing. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications 2021, 538, 173–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tantry, U.S.; Bliden, K.P.; Gurbel, P.A. Further evidence for the use of aspirin in COVID-19. Int J Cardiol 2022, 346, 107–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choubey, A.; Dehury, B.; Kumar, S.; Medhi, B.; Mondal, P. Naltrexone a potential therapeutic candidate for COVID-19. J Biomol Struct Dyn 2022, 40, 963–970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Kelly, B.; Vidal, L.; McHugh, T.; Woo, J.; Avramovic, G.; Lambert, J.S. Safety and efficacy of low dose naltrexone in a long covid cohort; an interventional pre-post study. Brain Behav Immun Health 2022, 24, 100485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karatza, E.; Ismailos, G.; Karalis, V. Colchicine for the treatment of COVID-19 patients: efficacy, safety, and model informed dosage regimens. Xenobiotica 2021, 51, 643–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chiu, L.; Lo, C.-H.; Shen, M.; Chiu, N.; Aggarwal, R.; Lee, J.; Choi, Y.-G.; Lam, H.; Prsic, E.H.; Chow, R.; et al. Colchicine use in patients with COVID-19: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One 2021, 16, e0261358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rabbani, A.B.; Parikh, R.V.; Rafique, A.M. Colchicine for the Treatment of Myocardial Injury in Patients With Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19)—An Old Drug With New Life? JAMA Network Open 2020, 3, e2013556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fiolet, A.T.L.; Opstal, T.S.J.; Mosterd, A.; Eikelboom, J.W.; Jolly, S.S.; Keech, A.C.; Kelly, P.; Tong, D.C.; Layland, J.; Nidorf, S.M.; et al. Efficacy and safety of low-dose colchicine in patients with coronary disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized trials. European Heart Journal 2021, 42, 2765–2775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ibrahim, S.; Lowe, J.R.; Bramante, C.T.; Shah, S.; Klatt, N.R.; Sherwood, N.; Aronne, L.; Puskarich, M.; Tamariz, L.; Palacio, A.; et al. Metformin and Covid-19: Focused Review of Mechanisms and Current Literature Suggesting Benefit. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 2021, 12, 587801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bramante, C.T.; Buse, J.B.; Liebovitz, D.M.; Nicklas, J.L.; Puskarich, M.A.; Cohen, K.; Belani, H.; Anderson, B.; Huling, J.D.; Tignanelli, C.J.; et al. Outpatient treatment of Covid-19 with metformin, ivermectin, and fluvoxamine and the development of Long Covid over 10-month follow-up. medRxiv 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prodromos, C.; Rumschlag, T. Hydroxychloroquine is effective, and consistently so when provided early, for COVID-19: a systematic review. New Microbes New Infect 2020, 38, 100776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsanovska, H.; Simova, I.; Genov, V.; Kundurzhiev, T.; Krasnaliev, J.; Kornovski, V.; Dimitrov, N.; Vekov, T. Hydroxychloroquine (HCQ) Treatment for Hospitalized Patients with COVID- 19. Infect Disord Drug Targets 2022, 22, 66–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barrea, L.; Verde, L.; Grant, W.B.; Frias-Toral, E.; Sarno, G.; Vetrani, C.; Ceriani, F.; Garcia-Velasquez, E.; Contreras-Briceño, J.; Savastano, S.; et al. Vitamin D: A Role Also in Long COVID-19? Nutrients 2022, 14, 1625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gönen, M.S.; Alaylıoğlu, M.; Durcan, E.; Özdemir, Y.; Şahin, S.; Konukoğlu, D.; Nohut, O.K.; Ürkmez, S.; Küçükece, B.; Balkan, İ.İ.; et al. Rapid and Effective Vitamin D Supplementation May Present Better Clinical Outcomes in COVID-19 (SARS-CoV-2) Patients by Altering Serum INOS1, IL1B, IFNg, Cathelicidin-LL37, and ICAM1. Nutrients 2021, 13, 4047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vollbracht, C.; Kraft, K. Feasibility of Vitamin C in the Treatment of Post Viral Fatigue with Focus on Long COVID, Based on a Systematic Review of IV Vitamin C on Fatigue. Nutrients 2021, 13, 1154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vollbracht, C.; Kraft, K. Oxidative Stress and Hyper-Inflammation as Major Drivers of Severe COVID-19 and Long COVID: Implications for the Benefit of High-Dose Intravenous Vitamin C. Front Pharmacol 2022, 13, 899198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tosato, M.; Calvani, R.; Picca, A.; Ciciarello, F.; Galluzzo, V.; Coelho-Júnior, H.J.; Di Giorgio, A.; Di Mario, C.; Gervasoni, J.; Gremese, E.; et al. Effects of l-Arginine Plus Vitamin C Supplementation on Physical Performance, Endothelial Function, and Persistent Fatigue in Adults with Long COVID: A Single-Blind Randomized Controlled Trial. Nutrients 2022, 14, 4984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Izzo, R.; Trimarco, V.; Mone, P.; Aloè, T.; Capra Marzani, M.; Diana, A.; Fazio, G.; Mallardo, M.; Maniscalco, M.; Marazzi, G.; et al. Combining L-Arginine with vitamin C improves long-COVID symptoms: The LINCOLN Survey. Pharmacol Res 2022, 183, 106360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mangge, H.; Prueller, F.; Dawczynski, C.; Curcic, P.; Sloup, Z.; Holter, M.; Herrmann, M.; Meinitzer, A. Dramatic Decrease of Vitamin K2 Subtype Menaquinone-7 in COVID-19 Patients. Antioxidants (Basel) 2022, 11, 1235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Debnath, U.; Dewaker, V.; Prabhakar, Y.S.; Bhattacharyya, P.; Mandal, A. Conformational Perturbation of SARS-CoV-2 Spike Protein Using N-Acetyl Cysteine, a Molecular Scissor: A Probable Strategy to Combat COVID-19. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Z.; Puyo, C.A. N-Acetylcysteine to Combat COVID-19: An Evidence Review. Ther Clin Risk Manag 2020, 16, 1047–1055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poe, F.L.; Corn, J. N-Acetylcysteine: A potential therapeutic agent for SARS-CoV-2. Med Hypotheses 2020, 143, 109862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, K.K.; Lee, S.W.H.; Kua, K.P. N-Acetylcysteine as Adjuvant Therapy for COVID-19 – A Perspective on the Current State of the Evidence. J Inflamm Res 2021, 14, 2993–3013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sengupta, P.; Dutta, S. N-acetyl cysteine as a potential regulator of SARS-CoV-2-induced male reproductive disruptions. Middle East Fertil Soc J 2022, 27, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Debnath, U.; Mitra, A.; Dewaker, V.; Prabhakar, Y.S.; Tadala, R.; Krishnan, K.; Wagh, P.; Velusamy, U.; Subramani, C.; Agarwal, S.; et al. N-acetyl cysteine: A tool to perturb SARS-CoV-2 spike protein conformation. 2021. [CrossRef]

- Amin, A.N. The Role of Glutathione Deficiency and MSIDS Variables in Long COVID-19. Available online: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT05371288 (accessed on 2022).

- Guloyan, V.; Oganesian, B.; Baghdasaryan, N.; Yeh, C.; Singh, M.; Guilford, F.; Ting, Y.-S.; Venketaraman, V. Glutathione Supplementation as an Adjunctive Therapy in COVID-19. Antioxidants (Basel) 2020, 9, E914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Polonikov, A. Endogenous Deficiency of Glutathione as the Most Likely Cause of Serious Manifestations and Death in COVID-19 Patients. ACS Infect Dis 2020, 6, 1558–1562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silvagno, F.; Vernone, A.; Pescarmona, G.P. The Role of Glutathione in Protecting against the Severe Inflammatory Response Triggered by COVID-19. Antioxidants (Basel) 2020, 9, 624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jarrott, B.; Head, R.; Pringle, K.G.; Lumbers, E.R.; Martin, J.H. “LONG COVID”-A hypothesis for understanding the biological basis and pharmacological treatment strategy. Pharmacol Res Perspect 2022, 10, e00911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardinali, D.P.; Brown, G.M.; Pandi-Perumal, S.R. Possible Application of Melatonin in Long COVID. Biomolecules 2022, 12, 1646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lan, S.-H.; Lee, H.-Z.; Chao, C.-M.; Chang, S.-P.; Lu, L.-C.; Lai, C.-C. Efficacy of melatonin in the treatment of patients with COVID-19: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Journal of Medical Virology 2022, 94, 2102–2107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Derosa, G.; Maffioli, P.; D’Angelo, A.; Di Pierro, F. A role for quercetin in coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). Phytother Res 2021, 35, 1230–1236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuli, H.; Sood, S.; Pundir, A.; Choudhary, D.; Dhama, K.; Kaur, G.; Seth, P.; Vashishth, A.; Kumar, P. Molecular Docking studies of Apigenin, Kaempferol, and Quercetin as potential target against spike receptor protein of SARS COV. Journal of Experimental Biology and Agricultural Sciences 2022, 10, 144–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ÖNAL, H.; ARSLAN, B.; ÜÇÜNCÜ ERGUN, N.; TOPUZ, Ş.; YILMAZ SEMERCİ, S.; KURNAZ, M.E.; MOLU, Y.M.; BOZKURT, M.A.; SÜNER, N.; KOCATAŞ, A. Treatment of COVID-19 patients with quercetin: a prospective, single center, randomized, controlled trial. Turk J Biol 2021, 45, 518–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pan, B.; Fang, S.; Zhang, J.; Pan, Y.; Liu, H.; Wang, Y.; Li, M.; Liu, L. Chinese herbal compounds against SARS-CoV-2: Puerarin and quercetin impair the binding of viral S-protein to ACE2 receptor. Comput Struct Biotechnol J 2020, 18, 3518–3527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manjunath, S.H.; Thimmulappa, R.K. Antiviral, immunomodulatory, and anticoagulant effects of quercetin and its derivatives: Potential role in prevention and management of COVID-19. Journal of Pharmaceutical Analysis 2022, 12, 29–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, A.; Iqtadar, S.; Mumtaz, S.U.; Heinrich, M.; Pascual-Figal, D.A.; Livingstone, S.; Abaidullah, S. Oral Co-Supplementation of Curcumin, Quercetin, and Vitamin D3 as an Adjuvant Therapy for Mild to Moderate Symptoms of COVID-19—Results From a Pilot Open-Label, Randomized Controlled Trial. Front Pharmacol 2022, 13, 898062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ho, T.-Y.; Wu, S.-L.; Chen, J.-C.; Li, C.-C.; Hsiang, C.-Y. Emodin blocks the SARS coronavirus spike protein and angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 interaction. Antiviral Res 2007, 74, 92–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maideen, N.M.P. Prophetic Medicine-Nigella Sativa (Black cumin seeds) - Potential herb for COVID-19? J Pharmacopuncture 2020, 23, 62–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, M.T. Potential benefits of combination of Nigella sativa and Zn supplements to treat COVID-19. J Herb Med 2020, 23, 100382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Banerjee, A.; Kanwar, M.; Das Mohapatra, P.K.; Saso, L.; Nicoletti, M.; Maiti, S. Nigellidine (Nigella sativa, black-cumin seed) docking to SARS CoV-2 nsp3 and host inflammatory proteins may inhibit viral replication/transcription and FAS-TNF death signal via TNFR 1/2 blocking. Nat Prod Res 2021, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giordo, R.; Zinellu, A.; Eid, A.H.; Pintus, G. Therapeutic Potential of Resveratrol in COVID-19-Associated Hemostatic Disorders. Molecules 2021, 26, 856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pasquereau, S.; Nehme, Z.; Haidar Ahmad, S.; Daouad, F.; Van Assche, J.; Wallet, C.; Schwartz, C.; Rohr, O.; Morot-Bizot, S.; Herbein, G. Resveratrol Inhibits HCoV-229E and SARS-CoV-2 Coronavirus Replication In Vitro. Viruses 2021, 13, 354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramdani, L.H.; Bachari, K. Potential therapeutic effects of Resveratrol against SARS-CoV-2. Acta Virol 2020, 64, 276–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCreary, M.R.; Schnell, P.M.; Rhoda, D.A. Randomized double-blind placebo-controlled proof-of-concept trial of resveratrol for outpatient treatment of mild coronavirus disease (COVID-19). Sci Rep 2022, 12, 10978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zahedipour, F.; Hosseini, S.A.; Sathyapalan, T.; Majeed, M.; Jamialahmadi, T.; Al-Rasadi, K.; Banach, M.; Sahebkar, A. Potential effects of curcumin in the treatment of COVID-19 infection. Phytother Res 2020, 34, 2911–2920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suravajhala, R.; Parashar, A.; Malik, B.; Nagaraj, A.V.; Padmanaban, G.; Kishor, P.K.; Polavarapu, R.; Suravajhala, P. Comparative Docking Studies on Curcumin with COVID-19 Proteins 2020. [CrossRef]

- Jena, A.B.; Kanungo, N.; Nayak, V.; Chainy, G.B.N.; Dandapat, J. Catechin and curcumin interact with S protein of SARS-CoV2 and ACE2 of human cell membrane: insights from computational studies. Sci Rep 2021, 11, 2043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rattis, B.A.C.; Ramos, S.G.; Celes, M.R.N. Curcumin as a Potential Treatment for COVID-19. Frontiers in Pharmacology 2021, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vahedian-Azimi, A.; Abbasifard, M.; Rahimi-Bashar, F.; Guest, P.C.; Majeed, M.; Mohammadi, A.; Banach, M.; Jamialahmadi, T.; Sahebkar, A. Effectiveness of Curcumin on Outcomes of Hospitalized COVID-19 Patients: A Systematic Review of Clinical Trials. Nutrients 2022, 14, 256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelazeem, B.; Awad, A.K.; Elbadawy, M.A.; Manasrah, N.; Malik, B.; Yousaf, A.; Alqasem, S.; Banour, S.; Abdelmohsen, S.M. The effects of curcumin as dietary supplement for patients with COVID-19: A systematic review of randomized clinical trials. Drug Discoveries & Therapeutics 2022, 16, 14–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iotti, S.; Wolf, F.; Mazur, A.; Maier, J.A. The COVID-19 pandemic: is there a role for magnesium? Hypotheses and perspectives. Magnes Res 2020, 33, 21–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, C.-F.; Ding, H.; Jiao, R.-Q.; Wu, X.-X.; Kong, L.-D. Possibility of magnesium supplementation for supportive treatment in patients with COVID-19. Eur J Pharmacol 2020, 886, 173546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerrero-Romero, F.; Mercado, M.; Rodriguez-Moran, M.; Ramírez-Renteria, C.; Martínez-Aguilar, G.; Marrero-Rodríguez, D.; Ferreira-Hermosillo, A.; Simental-Mendía, L.E.; Remba-Shapiro, I.; Gamboa-Gómez, C.I.; et al. Magnesium-to-Calcium Ratio and Mortality from COVID-19. Nutrients 2022, 14, 1686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tian, J.; Tang, L.; Liu, X.; Li, Y.; Chen, J.; Huang, W.; Liu, M. Populations in Low-Magnesium Areas Were Associated with Higher Risk of Infection in COVID-19’s Early Transmission: A Nationwide Retrospective Cohort Study in the United States. Nutrients 2022, 14, 909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabatabaeizadeh, S.-A. Zinc supplementation and COVID-19 mortality: a meta-analysis. Eur J Med Res 2022, 27, 70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pal, A.; Squitti, R.; Picozza, M.; Pawar, A.; Rongioletti, M.; Dutta, A.K.; Sahoo, S.; Goswami, K.; Sharma, P.; Prasad, R. Zinc and COVID-19: Basis of Current Clinical Trials. Biol Trace Elem Res 2021, 199, 2882–2892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prasad, A.S.; Malysa, A.; Bepler, G.; Fribley, A.; Bao, B. The Mechanisms of Zinc Action as a Potent Anti-Viral Agent: The Clinical Therapeutic Implication in COVID-19. Antioxidants 2022, 11, 1862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedrosa, L.F.C.; Barros, A.N.A.B.; Leite-Lais, L. Nutritional risk of vitamin D, vitamin C, zinc, and selenium deficiency on risk and clinical outcomes of COVID-19: A narrative review. Clinical Nutrition ESPEN 2022, 47, 9–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balboni, E.; Zagnoli, F.; Filippini, T.; Fairweather-Tait, S.J.; Vinceti, M. Zinc and selenium supplementation in COVID-19 prevention and treatment: a systematic review of the experimental studies. Journal of Trace Elements in Medicine and Biology 2022, 71, 126956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, Y.; Zhang, L.; Zeng, R.; Luo, D.; Jiang, R.; Wu, H.; Zhuo, Z.; Yang, Q.; Li, J.; Leung, F.W.; et al. Associations of habitual fish oil use with risk of SARS-CoV-2 infection and COVID-19-related outcomes in UK: national population based cohort study 2022. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merritt, R.J.; Bhardwaj, V.; Jami, M.M. Fish oil and COVID-19 thromboses. J Vasc Surg Venous Lymphat Disord 2020, 8, 1120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torrinhas, R.S.; Calder, P.C.; Lemos, G.O.; Waitzberg, D.L. Parenteral fish oil: An adjuvant pharmacotherapy for coronavirus disease 2019? Nutrition 2021, 81, 110900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Theoharides, T.C.; Cholevas, C.; Polyzoidis, K.; Politis, A. Long-COVID syndrome-associated brain fog and chemofog: Luteolin to the rescue. Biofactors 2021, 47, 232–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shadrack, D.M.; Deogratias, G.; Kiruri, L.W.; Onoka, I.; Vianney, J.-M.; Swai, H.; Nyandoro, S.S. Luteolin: a blocker of SARS-CoV-2 cell entry based on relaxed complex scheme, molecular dynamics simulation, and metadynamics. J Mol Model 2021, 27, 221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Theoharides, T.C. COVID-19, pulmonary mast cells, cytokine storms, and beneficial actions of luteolin. Biofactors 2020, 46, 306–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Di Stadio, A.; D’Ascanio, L.; Vaira, L.A.; Cantone, E.; De Luca, P.; Cingolani, C.; Motta, G.; De Riu, G.; Vitelli, F.; Spriano, G.; et al. Ultramicronized Palmitoylethanolamide and Luteolin Supplement Combined with Olfactory Training to Treat Post-COVID-19 Olfactory Impairment: A Multi-Center Double-Blinded Randomized Placebo- Controlled Clinical Trial. Current Neuropharmacology 2022, 20, 2001–2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masiello, P.; Novelli, M.; Beffy, P.; Menegazzi, M. Can Hypericum perforatum (SJW) prevent cytokine storm in COVID-19 patients? Phytother Res 2020, 34, 1471–1473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamed, F.F.; Anhlan, D.; Schöfbänker, M.; Schreiber, A.; Classen, N.; Hensel, A.; Hempel, G.; Scholz, W.; Kühn, J.; Hrincius, E.R.; et al. Hypericum perforatum and Its Ingredients Hypericin and Pseudohypericin Demonstrate an Antiviral Activity against SARS-CoV-2. Pharmaceuticals 2022, 15, 530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verdoorn, B.P.; Evans, T.K.; Hanson, G.J.; Zhu, Y.; Langhi Prata, L.G.P.; Pignolo, R.J.; Atkinson, E.J.; Wissler-Gerdes, E.O.; Kuchel, G.A.; Mannick, J.B.; et al. Fisetin for COVID-19 in skilled nursing facilities: Senolytic trials in the COVID era. J Am Geriatr Soc 2021, 69, 3023–3033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oladele, J.O.; Oyeleke, O.M.; Oladele, O.T.; Olowookere, B.D.; Oso, B.J.; Oladiji, A.T. Kolaviron (Kolaflavanone), apigenin, fisetin as potential Coronavirus inhibitors: In silico investigatio. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandey, P.; Rane, J.S.; Chatterjee, A.; Kumar, A.; Khan, R.; Prakash, A.; Ray, S. Targeting SARS-CoV-2 spike protein of COVID-19 with naturally occurring phytochemicals: an in silico study for drug development. J Biomol Struct Dyn 1–11. [CrossRef]

- Willyard, C. How anti-ageing drugs could boost COVID vaccines in older people. Nature 2020, 586, 352–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dey, D.; Dey, N.; Ghosh, S.; Chandrasekaran, N.; Mukherjee, A.; Thomas, J. Potential combination therapy using twenty phytochemicals from twenty plants to prevent SARS- CoV-2 infection: An in silico Approach. Virusdisease 2021, 32, 108–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawkins, J.; Hires, C.; Keenan, L.; Dunne, E. Aromatherapy blend of thyme, orange, clove bud, and frankincense boosts energy levels in post-COVID-19 female patients: A randomized, double-blinded, placebo controlled clinical trial. Complementary Therapies in Medicine 2022, 67, 102823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fajri, M. The potential of Moringa oleifera as immune booster against COVID 19. IOP Conf. Ser.: Earth Environ. Sci. 2021, 807, 022008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bachar, S.C.; Mazumder, K.; Bachar, R.; Aktar, A.; Al Mahtab, M. A Review of Medicinal Plants with Antiviral Activity Available in Bangladesh and Mechanistic Insight Into Their Bioactive Metabolites on SARS-CoV-2, HIV and HBV. Front Pharmacol 2021, 12, 732891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaves, O.A.; Lima, C.R.; Fintelman-Rodrigues, N.; Sacramento, C.Q.; de Freitas, C.S.; Vazquez, L.; Temerozo, J.R.; Rocha, M.E.N.; Dias, S.S.G.; Carels, N.; et al. Agathisflavone, a natural biflavonoid that inhibits SARS-CoV-2 replication by targeting its proteases. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules 2022, 222, 1015–1026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Janssens, J.; Laekeman, G.M.; Pieters, L.A.; Totte, J.; Herman, A.G.; Vlietinck, A.J. Nutmeg oil: identification and quantitation of its most active constituents as inhibitors of platelet aggregation. J Ethnopharmacol 1990, 29, 179–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le-Trilling, V.T.K.; Mennerich, D.; Schuler, C.; Sakson, R.; Lill, J.K.; Kasarla, S.S.; Kopczynski, D.; Loroch, S.; Flores-Martinez, Y.; Katschinski, B.; et al. Identification of herbal teas and their compounds eliciting antiviral activity against SARS-CoV-2 in vitro. BMC Biology 2022, 20, 264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Le-Trilling, V.T.K.; Mennerich, D.; Schuler, C.; Sakson, R.; Lill, J.K.; Kopczynski, D.; Loroch, S.; Flores-Martinez, Y.; Katschinski, B.; Wohlgemuth, K.; et al. Universally available herbal teas based on sage and perilla elicit potent antiviral activity against SARS-CoV-2 variants of concern by HMOX-1 upregulation in human cells 2022, 2020. 11.18.38 8710. [CrossRef]

- Omoboyowa, D.A.; A, B.T.; Chukwudozie, O.; Nweze, V.; Saibu, O.; Abdulahi, A. SARS-COV-2 Spike Glycoprotein as Inhibitory Target for Insilico Screening of Natural Compound. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumari, A.; Rajput, V.S.; Nagpal, P.; Kukrety, H.; Grover, S.; Grover, A. Dual inhibition of SARS-CoV-2 spike and main protease through a repurposed drug, rutin. J Biomol Struct Dyn 2022, 40, 4987–4999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagoor Meeran, M.F.; Seenipandi, A.; Javed, H.; Sharma, C.; Hashiesh, H.M.; Goyal, S.N.; Jha, N.K.; Ojha, S. Can limonene be a possible candidate for evaluation as an agent or adjuvant against infection, immunity, and inflammation in COVID-19? Heliyon 2021, 7, e05703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamed, M.E.; Tawfeek, N.; Elbaramawi, S.S.; Fikry, E. Agathis robusta Bark Essential Oil Effectiveness against COVID-19: Chemical Composition, In Silico and In Vitro Approaches. Plants 2022, 11, 663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ziyaei, K.; Ataie, Z.; Mokhtari, M.; Adrah, K.; Daneshmehr, M.A. An insight to the therapeutic potential of algae-derived sulfated polysaccharides and polyunsaturated fatty acids: Focusing on the COVID-19. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules 2022, 209, 244–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sami, N.; Ahmad, R.; Fatma, T. Exploring algae and cyanobacteria as a promising natural source of antiviral drug against SARS-CoV-2. Biomed J 2021, 44, 54–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tzachor, A.; Rozen, O.; Khatib, S.; Jensen, S.; Avni, D. Photosynthetically Controlled Spirulina, but Not Solar Spirulina, Inhibits TNF-α Secretion: Potential Implications for COVID-19-Related Cytokine Storm Therapy. Mar Biotechnol 2021, 23, 149–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.; Singh, R.P.; Kumar, I.; Yadav, P.; Singh, S.K.; Kaushalendra; Singh, P.K.; Gupta, R.K.; Singh, S.M.; Kesawat, M.S.; et al. Algal Metabolites Can Be an Immune Booster against COVID-19 Pandemic. Antioxidants (Basel) 2022, 11, 452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, H.T.T.; Gigl, M.; Le, N.P.K.; Dawid, C.; Lamy, E. In Vitro Effect of Taraxacum officinale Leaf Aqueous Extract on the Interaction between ACE2 Cell Surface Receptor and SARS-CoV-2 Spike Protein D614 and Four Mutants. Pharmaceuticals (Basel) 2021, 14, 1055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vavilova, V.P.; Петрoвна, В.В.; Vavilov, A.M.; Михайлoвич, В.А.; Tsarkova, S.A.; Анатoльевна, Ц.С.; Nesterova, O.L.; Леoнидoвна, Н.О.; Kulyabina, A.A.; Андреевна, К.А.; et al. One of the possibilities of optimizing the therapy of a new coronavirus infection in children with the inclusion of an extract from marshmallow root, chamomile flowers, horsetail grass, walnut leaves, yarrow grass, oak bark and dandelion grass: prospective open comparative cohort study. Pediatrics. Consilium Medicum 2022, 322–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucas, K.; Ackermann, M.; Leifke, A.L.; Li, W.W.; Pöschl, U.; Fröhlich-Nowoisky, J. Ceylon cinnamon and its major compound Cinnamaldehyde can limit overshooting inflammatory signaling and angiogenesis in vitro: implications for COVID-19 treatment. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucas, K.; Fröhlich-Nowoisky, J.; Oppitz, N.; Ackermann, M. Cinnamon and Hop Extracts as Potential Immunomodulators for Severe COVID-19 Cases. Frontiers in Plant Science 2021, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zareie, A.; Soleimani, D.; Askari, G.; Jamialahmadi, T.; Guest, P.C.; Bagherniya, M.; Sahebkar, A. Cinnamon: A Promising Natural Product Against COVID-19. Adv Exp Med Biol 2021, 1327, 191–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yakhchali, M.; Taghipour, Z.; Mirabzadeh Ardakani, M.; Alizadeh Vaghasloo, M.; Vazirian, M.; Sadrai, S. Cinnamon and its possible impact on COVID-19: The viewpoint of traditional and conventional medicine. Biomed Pharmacother 2021, 143, 112221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Musazadeh, V.; Karimi, A.; bagheri, N.; Jafarzadeh, J.; Sanaie, S.; Vajdi, M.; Karimi, M.; Niazkar, H.R. The favorable impacts of silibinin polyphenols as adjunctive therapy in reducing the complications of COVID-19: A review of research evidence and underlying mechanisms. Biomedicine & Pharmacotherapy 2022, 154, 113593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Speciale, A.; Muscarà, C.; Molonia, M.S.; Cimino, F.; Saija, A.; Giofrè, S.V. Silibinin as potential tool against SARS-Cov-2: In silico spike receptor-binding domain and main protease molecular docking analysis, and in vitro endothelial protective effects. Phytother Res 2021, 35, 4616–4625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Intharuksa, A.; Arunotayanun, W.; Yooin, W.; Sirisa-ard, P. A Comprehensive Review of Andrographis paniculata (Burm. f.) Nees and Its Constituents as Potential Lead Compounds for COVID-19 Drug Discovery. Molecules 2022, 27, 4479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sa-Ngiamsuntorn, K.; Suksatu, A.; Pewkliang, Y.; Thongsri, P.; Kanjanasirirat, P.; Manopwisedjaroen, S.; Charoensutthivarakul, S.; Wongtrakoongate, P.; Pitiporn, S.; Chaopreecha, J.; et al. Anti-SARS-CoV-2 Activity of Andrographis paniculata Extract and Its Major Component Andrographolide in Human Lung Epithelial Cells and Cytotoxicity Evaluation in Major Organ Cell Representatives. J Nat Prod 2021, 84, 1261–1270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Banerjee, S.; Kar, A.; Mukherjee, P.K.; Haldar, P.K.; Sharma, N.; Katiyar, C.K. Immunoprotective potential of Ayurvedic herb Kalmegh (Andrographis paniculata) against respiratory viral infections - LC-MS/MS and network pharmacology analysis. Phytochem Anal 2021, 32, 629–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]