1. Introduction

The social losses associated with mental illness are enormous, and long-term declines in social functioning can impact various social situations, including employment, schooling, and interpersonal relationships [

1,

2]. Declines in social functioning are relatively common especially in cases with severe mental illnesses such as psychotic disorders, bipolar disorders, and major depressive disorders, which often have a chronic course [

3,

4]. In people with schizophrenia, the improvement of social functioning, as well as the improvement of psychiatric symptoms, has long been considered an important therapeutic goal, and factors contributing to social functioning have been explored [

5]. Impairments in neurocognition are a core feature of schizophrenia and are representative of contributing factors impacting social functioning [

6,

7]. The associations between social functioning and various neurocognitive domains, including processing speed, verbal memory, working memory, and divergent thinking, have been clarified, and their biological bases have been widely reported [

8,

9,

10,

11]. However, impairments in neurocognition alone cannot fully explain the decline in social functioning, and factors mediating the relationship between neurocognition and social functioning have been explored. One key candidate is social cognition [

12,

13]. Social cognition refers to “the mental operations that underlie social interactions, including perceiving, interpreting, and generating responses to the intentions, dispositions, and behaviors of others” [

14,

15]. The representative domains of social cognition are theory of mind, social perception and knowledge, attributional style/bias, and emotion processing [

14,

16]. Various measures of social cognition have been developed, and a decline in social cognition in people with schizophrenia has been widely reported [

17,

18,

19,

20]. Social cognitive decline is attracting attention as a novel therapeutic target [

21,

22]. A variety of other factors related to social functioning have now been reported, and these factors could affect one other; however, neurocognition and social cognition remain critical factors [

23,

24,

25].

In addition to schizophrenia, impairments in cognitive function in other psychiatric disorders have also been observed. In people with major depressive disorder, a wide range of cognitive impairments has been reported [

26,

27,

28]. Importantly, even after the remission of mood symptoms, cognitive impairments persisted and worsened with each recurrent episode [

29,

30]. These cognitive impairments might be a core feature of major depressive disorder and an independent symptom, rather than a symptom that arises secondarily from mood symptoms [

26,

31,

32]. A growing number of reports on social cognition in major depressive disorder have also reported long-term impairments and associations with social functioning [

33,

34,

35]. As noted above, social cognition in schizophrenia mediates the relationship between neurocognition and social functioning; however, in major depressive disorder, the detailed role of social cognition in social functioning remains poorly understood [

36,

37]. Establishing strategies to improve social functioning is an important issue not only in schizophrenia, but also in major depressive disorder, and there is an urgent need to elucidate mechanisms related to the manifestations of social functioning.

In the present study, we hypothesized that the mediating effects of social cognition on the relationship between neurocognition and social functioning would be similar in both people with schizophrenia and those with major depressive disorder. The purpose of the present study was to examine this relationship in patients with stable schizophrenia and major depressive disorder during the chronic disease phase.

2. Methods

2.1. Study Design and Participants

This study was part of a previous web-based survey [

38]. The cross-sectional survey was conducted from March 5 to March 15, 2021, by a professional agency (Rakuten Insight, Inc., Tokyo, Japan;

https://member.insight.rakuten.co.in/) and included a large internet survey panel of individuals who had previously enrolled as subjects with various mental and physical illnesses or with no history of illness on a self-reported basis. The registration information for this panel was regularly checked and updated by the agency. The agency sent the survey panel a link to the online question form via an email explaining the survey. The inclusion criteria for survey participants were an age of 20 to 59 years, a diagnosis of schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder, or major depressive disorder, continuous outpatient treatment for at least one year, and no history of psychiatric hospitalization within three months of the study assessment. The exclusion criteria were a history of alcohol or substance abuse, and a history of brain injury, convulsive seizure, or severe physical illness.

The survey began with the presentation of a page explaining the purpose of the survey and obtaining the participants’ consent, followed by questions regarding the inclusion/exclusion criteria. To confirm the diagnoses, a question was asked regarding whether the participants had been informed by a clinician that they had schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder, or major depressive disorder; if they had not, they were excluded. Self-reported questions concerning each of the other inclusion/exclusion criteria were also included (i.e., whether the patient had been receiving outpatient treatment for at least one year continuously; whether the patient had been hospitalized within three months; and whether the patient had no episodes of substance abuse, convulsions, or serious physical illness). Participants who met all the criteria were then allowed to proceed to the main question pages; those who did not meet all the criteria exited the survey. After the completion of the survey, respondents who provided the same answer to all the questions (i.e., straight-lining) were excluded. Furthermore, based on a method used for a previous internet survey study [

39], participants who provided fraudulent responses were excluded. Further details regarding this question were described in the previous papers [

38,

39].

Informed consent was obtained before the participants responded to the questionnaire, and the participants were provided the option to stop the survey at any point. The study protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Medicine, Toho University (A20074 and A22041_ A20074). The internet survey agency respected the Act on the Protection of Personal Information in Japan. This study was performed in accordance with the latest version of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Completed survey data were obtained from 232 patients with schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder and 441 patients with major depressive disorder. Using propensity score matching [

40], 210 patients with schizophrenia (SZ group) and 210 patients with major depressive disorder (MDD group) were extracted based on their ages, sexes, and durations of illness. These variables were used in the logistic regression to generate a propensity score. Using the nearest-neighbor method without replacement and a caliper of 0.20, subjects were matched 1:1.

2.2. Measures

Social cognition was evaluated using the Self-Assessment of Social Cognition Impairments (ACSo). The ACSo is a 12-item self-administered questionnaire examining subjective complaints regarding four domains of social cognitive impairment: emotional processes, social perception and knowledge, theory of mind, and attributional bias [

41]. A higher score on the ACSo indicates a greater difficulty in the social cognition domain. Neurocognition was evaluated using the Perceived Deficits Questionnaire (PDQ) [

42]. The PDQ is a self-administered questionnaire examining self-perceived neurocognitive difficulties within the domains of prospective memory, retrospective memory, attention/concentration, and planning/organization. A higher score on the PDQ indicates a greater difficulty in the neurocognition domain. The PDQ-5, which is a shorter version of the PDQ, was used in the presently reported survey. Social functioning was evaluated using the Social Functioning Scale (SFS), which is a self-administered measure of a wide range of community functioning parameters, including withdrawal, interpersonal behavior, pro-social activities, recreation, independence-performance, independence-competence, and employment [

43,

44,

45]. A higher score on the SFS indicates a more favorable functioning. The total SFS score was used in the presently reported study.

2.3. Data Analysis

First, the demographics and clinical characteristics were compared between the SZ and MDD groups using the t-test for continuous variables and the chi-squared test for categorical variables. Then, the mediation effects of social cognition on the relationship between neurocognition and social functioning were examined in each group using Structural Equation Modeling (SEM). To assess the model fit, the chi-squared/df, the comparative fit index (CFI), and the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) were calculated. A good fit was regarded as a chi-squared/df value < 2, a CFI > 0.97, and an RMSEA < 0.05. An acceptable fit was regarded as a chi-squared/df < 3, a CFI > 0.95, and an RMSEA < 0.08 [

46,

47]. In SEM, the model-building approach was used when the models were improved by adding passes, while considering the modification indices [

48]. The model was adopted if the chi-squared value was significantly (p < 0.05) improved by adding a pass. The indirect effect of neurocognition on social functioning of each group was also assessed using the Sobel test. Finally, invariances of the mediation model across the two groups were examined using a multiple-group SEM. Configural, metric, scalar, residual, and structural invariances across the groups were confirmed step-by-step. To assess the deterioration of the model fit between the configural, metric, scalar, residual, and structural models, changes in CFI (ΔCFI) of < 0.01 and changes in RMSEA (ΔRMSEA) of < 0.015 were regarded as acceptable [

49].

Statistical differences were determined using two-tailed tests and a significance level of p < 0.05. Data were analyzed using SPSS, version 26.0, and AMOS, version 26.0.

3. Results

3.1. Demographics and Clinical Characteristics

The demographics and clinical characteristics are shown in

Table 1. The SZ and MDD groups had mean ages of 44.49 and 45.35 years, were comprised of 42.0% and 42.8% females, and had a mean illness durations of 10.76 and 10.45 years, respectively. The SZ group had significantly greater difficulties than the MDD group for the PDQ-5 Prospective memory, ACSo Emotional processes, ACSo Theory of mind, and ACSo Social perception scales.

3.2. Mediation Effects of Social Cognition

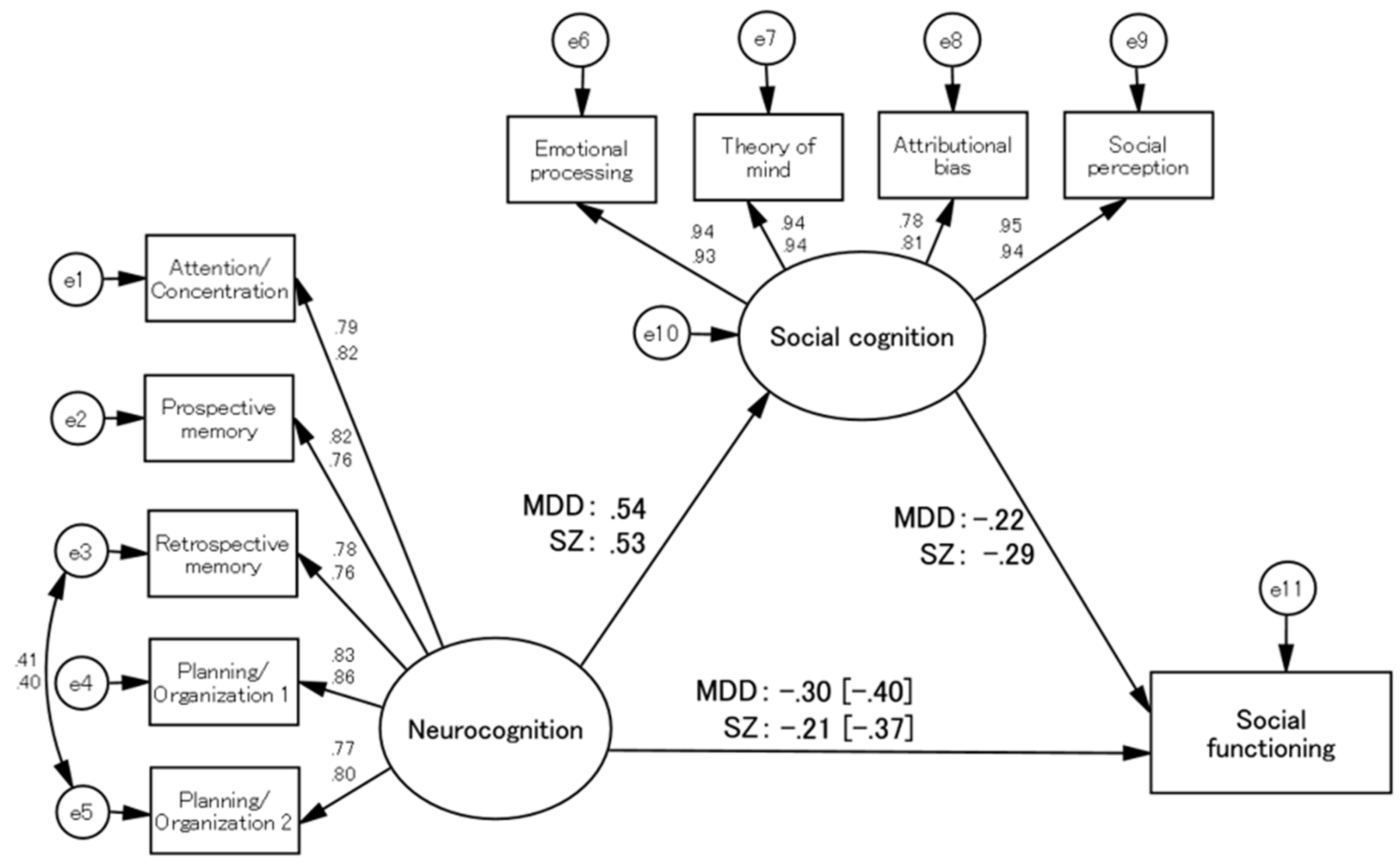

In each group, social cognition had significant mediation effects. After the SEM model-building process, the final models for the SZ and MDD groups showed good and acceptable fit indices: respective chi-squared/df values of 1.960 and 2.378, CFI values of 0.981 and 0.974, and RMSEA values of 0.068 and 0.081, respectively (

Figure 1). Sobel tests revealed significant indirect effects of neurocognition on social functioning in both groups (Sobel test statistic = -3.407, p = 0.001 in the SZ group; Sobel test statistic = -2.718, p = 0.007 in the MDD group).

3.3. Invariances in the Mediation Models across Groups

Configural invariance was first examined by specifying the same mediation model across the SZ and MDD groups, while allowing all other parameters to differ. The fit indices for this model were all acceptable (CFI = 0.978, RMSEA = 0.052), suggesting that a configural invariance of the mediation model across the two groups was established.

Then, metric invariance was examined by requiring the same model and equal factor loadings across the two groups, while all other parameters were allowed to differ. The fit indices were all acceptable, and the CFI and RMSEA were not worsened (∆CFI < 0.001, ∆RMSEA = -0.003), suggesting that metric invariance was established.

Scalar invariance was next examined by requiring the same model and equal factor loadings and item intercepts across the two groups, while all other parameters were allowed to differ. The fit indices were all acceptable, and the deteriorations in CFI and RMSEA were within acceptable ranges (∆CFI = -0.003, ∆RMSEA < -0.001), suggesting that scalar invariance was established.

Next, residual invariance was examined by requiring the same model and equal factor loadings, item intercepts, and error variances across the two groups while all other parameters were allowed to differ. The fit indices were all good, and the deteriorations in CFI and RMSEA were within acceptable ranges (∆CFI = -0.002, ∆RMSEA = -0.001), suggesting that residual invariance was established.

Finally, structural invariance was examined by requiring the same model and equal factor loadings, item intercepts, error variances, and path coefficients across the two groups. The fit indices were all good, and the deteriorations in CFI and RMSEA were within acceptable ranges (∆CFI = 0.001, ∆RMSEA = -0.002), suggesting that structural invariance was established.

After examining the invariances of the mediation model across the two groups, all the models at each level of parameter constraint were accepted, and robust invariances were established. The results of the invariance examinations are shown in

Table 2.

4. Discussion

This study examined the mediating effects of social cognition in chronic-phase patients with schizophrenia or major depressive disorder. When the two disease groups were compared, the SZ group showed greater difficulties than the MDD group for some neurocognition scales and for many social cognition scales. Although mixed results have been reported in comparing cognitive function between schizophrenia and major depressive disorder, in general, the levels of cognitive impairments are more severe in patients with schizophrenia than in patients with major depressive disorders [

50,

51,

52]. Furthermore, social cognition is more impaired than neurocognition in patients with schizophrenia, but not in patients with affective disorders [

53], consistent with the results of the present study. On the other hand, a growing number of studies have sought to clarify cognitive impairment profiles in patients with schizophrenia and major depressive disorder in detail, and further investigation is expected [

54,

55,

56].

Mediation effects of social cognition on the relationship between neurocognition and social functioning have been reported in patients with schizophrenia. The mediation model used in the present study is typical for schizophrenia research. The significant mediation effect of social cognition in the present study is consistent with the robust results of previous studies in patients with schizophrenia [

13,

23]. Notably, the present study also showed significant mediation effects in patients with major depressive disorder. To the best of our knowledge, no study has demonstrated a mediation effect of social cognition in major depressive disorder that is similar to the mediation effect seen for schizophrenia. Both schizophrenia and major depressive disorder are characterized by impairments of neurocognition and social cognition, and it is also common for patients with schizophrenia to present with depressive symptoms [

57,

58]. In addition to the commonality of the symptoms, the present results suggested that social cognition has a similar impact on social functioning in both chronic-phase schizophrenia and major depressive disorder.

Furthermore, in the examinations of the invariances of the mediation model across the SZ and MDD groups, all the models at each level of parameter constraint were accepted, and robust invariances were established. In recent years, classification issues arising from conventional diagnostic systems based mainly on symptomatology have been pointed out, and there have been attempts to explore biological factors across illnesses [

59,

60]. Not only do schizophrenia and major depressive disorder share common symptoms, they also reportedly share a common genetic background [

61,

62,

63]. Therefore, it is not surprising that cognitive impairments are a common endophenotype for both illnesses [

64], and the results of the present study support this conclusion. This commonality may be applicable not only to major depressive disorder and schizophrenia, but also to various other mental illnesses.

The present study had some limitations. The study was conducted as an online survey; consequently, the subjects’ diagnoses were based only on self-reported information. Although this study took a cautious view of adopting an online method and implemented methodologies that enhance the reliability and validity of such surveys [

38,

39], these precautions may have been insufficient. Additionally, psychiatric symptoms, including depressive mood, were not assessed or included in the model. However, the fact that we were able to confirm the same mediation model for the self-reported schizophrenia patients in the present study as that reported in previous studies may indicate a certain degree of validity for the present participants. Regarding the measures used in the present study, all the items were self-administered and examined subjective difficulties. Although it is not uncommon for cognitive impairments to differ between objective assessments and subjective ratings, the ACSo, which is a measure of subjective social cognitive difficulties, had a high degree of relationship with social functioning and may help to examine the role of social cognition on social functioning [

38]. Considering the differences between subjective and objective assessments and their confounding factors, the results of the present study need to be interpreted carefully.

5. Conclusions

The role of social cognition in major depressive disorder was similar to that observed in schizophrenia. In both chronic-phase schizophrenia and major depressive disorder, the mediation effect of social cognition on the relationship between neurocognition and social functioning was confirmed to have robust invariances. Social cognitive impairments could be a common endophenotype for various mental illnesses.

Author Contributions

T.U., R.O., and T.N. designed the study and wrote the protocol. Y.T., A.A., I.W., N.H., and S.I. were involved in the conceptualization of the study. T.U. collected the data, undertook the statistical analysis, and wrote the first draft of the manuscript. T.N. managed the study and supervised the writing of the manuscript. All the authors contributed to and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

The present study was supported by a grant from the Japan Agency for Medical Research and Development (AMED) (grant number JP20dk0307092) to R.O., N.H., S.I., and T.N. This funding source had no role in the study design, data collection and analyses, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Medicine, Toho University (approval number: A20074 and A22041_A20074; approval date: Dec 2, 2020, and Sep 7, 2022, respectively).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained before the participants responded to the questionnaire, and the participants were provided the option to stop the survey at any point.

Data Availability Statement

Data supporting the findings of this study are available upon reasonable request to the corresponding author. The data will not be made publicly available because of privacy and ethical restrictions.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Walker, E.R.; McGee, R.E.; Druss, B.G. Mortality in Mental Disorders and Global Disease Burden Implications: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. JAMA Psychiatry 2015, 72, 334–341. [CrossRef]

- Whiteford, H.A.; Degenhardt, L.; Rehm, J.; Baxter, A.J.; Ferrari, A.J.; Erskine, H.E.; Charlson, F.J.; Norman, R.E.; Flaxman, A.D.; Johns, N.; et al. Global Burden of Disease Attributable to Mental and Substance Use Disorders: Findings from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. Lancet 2013, 382, 1575–1586. [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization World Report on Disability 2011. World Health Organisation and The World Bank. 2011, 91, 549. [CrossRef]

- GBD 2016 Disease and Injury Incidence and Prevalence Collaborators Global, Regional, and National Incidence, Prevalence, and Years Lived with Disability for 328 Diseases and Injuries for 195 Countries, 1990-2016: A Systematic Analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. Lancet 2017, 390, 1211–1259. [CrossRef]

- Jääskeläinen, E.; Juola, P.; Hirvonen, N.; McGrath, J.J.; Saha, S.; Isohanni, M.; Veijola, J.; Miettunen, J. A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Recovery in Schizophrenia. Schizophr. Bull. 2013, 39, 1296–1306. [CrossRef]

- Green, M.F.; Kern, R.S.; Heaton, R.K. Longitudinal Studies of Cognition and Functional Outcome in Schizophrenia: Implications for MATRICS. Schizophr. Res. 2004, 72, 41–51. [CrossRef]

- Cowman, M.; Holleran, L.; Lonergan, E.; O’Connor, K.; Birchwood, M.; Donohoe, G. Cognitive Predictors of Social and Occupational Functioning in Early Psychosis: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Cross-Sectional and Longitudinal Data. Schizophr. Bull. 2021, 47, 1243–1253. [CrossRef]

- Gebreegziabhere, Y.; Habatmu, K.; Mihretu, A.; Cella, M.; Alem, A. Cognitive Impairment in People with Schizophrenia: An Umbrella Review. Eur. Arch. Psychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 2022, 272, 1139–1155. [CrossRef]

- Khalil, M.; Hollander, P.; Raucher-Chéné, D.; Lepage, M.; Lavigne, K.M. Structural Brain Correlates of Cognitive Function in Schizophrenia: A Meta-Analysis. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2022, 132, 37–49. [CrossRef]

- Nemoto, T.; Kashima, H.; Mizuno, M. Contribution of Divergent Thinking to Community Functioning in Schizophrenia. Prog. Neuropsychopharmacol. Biol. Psychiatry 2007, 31, 517–524. [CrossRef]

- Nemoto, T.; Takeshi, K.; Niimura, H.; Tobe, M.; Ito, R.; Kojima, A.; Saito, H.; Funatogawa, T.; Yamaguchi, T.; Katagiri, N.; et al. Feasibility and Acceptability of Cognitive Rehabilitation during the Acute Phase of Schizophrenia. Early Interv. Psychiatry 2021, 15, 457–462. [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, S.J.; Mueller, D.R.; Roder, V. Social Cognition as a Mediator Variable between Neurocognition and Functional Outcome in Schizophrenia: Empirical Review and New Results by Structural Equation Modeling. Schizophr. Bull. 2011, 37 Suppl 2, S41-54. [CrossRef]

- Kharawala, S.; Hastedt, C.; Podhorna, J.; Shukla, H.; Kappelhoff, B.; Harvey, P.D. The Relationship between Cognition and Functioning in Schizophrenia: A Semi-Systematic Review. Schizophr. Res. Cogn. 2022, 27, 100217. [CrossRef]

- Green, M.F.; Horan, W.P.; Lee, J. Nonsocial and Social Cognition in Schizophrenia: Current Evidence and Future Directions. World Psychiatry 2019, 18, 146–161. [CrossRef]

- Green, M.F.; Penn, D.L.; Bentall, R.; Carpenter, W.T.; Gaebel, W.; Gur, R.C.; Kring, A.M.; Park, S.; Silverstein, S.M.; Heinssen, R. Social Cognition in Schizophrenia: An NIMH Workshop on Definitions, Assessment, and Research Opportunities. Schizophr. Bull. 2008, 34, 1211–1220. [CrossRef]

- Pinkham, A.E.; Penn, D.L.; Green, M.F.; Buck, B.; Healey, K.; Harvey, P.D. The Social Cognition Psychometric Evaluation Study: Results of the Expert Survey and RAND Panel. Schizophr. Bull. 2014, 40, 813–823. [CrossRef]

- Pinkham, A.E.; Harvey, P.D.; Penn, D.L. Social Cognition Psychometric Evaluation: Results of the Final Validation Study. Schizophr. Bull. 2018, 44, 737–748. [CrossRef]

- Okano, H.; Kubota, R.; Okubo, R.; Hashimoto, N.; Ikezawa, S.; Toyomaki, A.; Miyazaki, A.; Sasaki, Y.; Yamada, Y.; Nemoto, T.; et al. Evaluation of Social Cognition Measures for Japanese Patients with Schizophrenia Using an Expert Panel and Modified Delphi Method. J. Pers. Med. 2021, 11, 275. [CrossRef]

- Lim, K.; Lee, S.-A.; Pinkham, A.E.; Lam, M.; Lee, J. Evaluation of Social Cognitive Measures in an Asian Schizophrenia Sample. Schizophr. Res. Cogn. 2020, 20, 100169. [CrossRef]

- Kubota, R.; Okubo, R.; Akiyama, H.; Okano, H.; Ikezawa, S.; Miyazaki, A.; Toyomaki, A.; Sasaki, Y.; Yamada, Y.; Uchino, T.; et al. Study Protocol: The Evaluation Study for Social Cognition Measures in Japan (ESCoM). J. Pers. Med. 2021, 11, 667. [CrossRef]

- Horan, W.P.; Green, M.F. Treatment of Social Cognition in Schizophrenia: Current Status and Future Directions. Schizophr. Res. 2019, 203, 3–11. [CrossRef]

- Nahum, M.; Lee, H.; Fisher, M.; Green, M.F.; Hooker, C.I.; Ventura, J.; Jordan, J.T.; Rose, A.; Kim, S.-J.; Haut, K.M.; et al. Online Social Cognition Training in Schizophrenia: A Double-Blind, Randomized, Controlled Multi-Site Clinical Trial. Schizophr. Bull. 2021, 47, 108–117. [CrossRef]

- Halverson, T.F.; Orleans-Pobee, M.; Merritt, C.; Sheeran, P.; Fett, A.-K.; Penn, D.L. Pathways to Functional Outcomes in Schizophrenia Spectrum Disorders: Meta-Analysis of Social Cognitive and Neurocognitive Predictors. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2019, 105, 212–219. [CrossRef]

- Mucci, A.; Galderisi, S.; Gibertoni, D.; Rossi, A.; Rocca, P.; Bertolino, A.; Aguglia, E.; Amore, M.; Bellomo, A.; Biondi, M.; et al. Factors Associated With Real-Life Functioning in Persons With Schizophrenia in a 4-Year Follow-up Study of the Italian Network for Research on Psychoses. JAMA Psychiatry 2021, 78, 550–559. [CrossRef]

- Nemoto, T.; Uchino, T.; Aikawa, S.; Matsuo, S.; Mamiya, N.; Shibasaki, Y.; Wada, Y.; Yamaguchi, T.; Katagiri, N.; Tsujino, N.; et al. Impact of Changes in Social Anxiety on Social Functioning and Quality of Life in Outpatients with Schizophrenia: A Naturalistic Longitudinal Study. J. Psychiatr. Res. 2020, 131, 15–21. [CrossRef]

- Szmulewicz, A.G.; Valerio, M.P.; Smith, J.M.; Samamé, C.; Martino, D.J.; Strejilevich, S.A. Neuropsychological Profiles of Major Depressive Disorder and Bipolar Disorder during Euthymia. A Systematic Literature Review of Comparative Studies. Psychiatry Res. 2017, 248, 127–133. [CrossRef]

- Rock, P.L.; Roiser, J.P.; Riedel, W.J.; Blackwell, A.D. Cognitive Impairment in Depression: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Psychol. Med. 2014, 44, 2029–2040. [CrossRef]

- Knight, M.J.; Baune, B.T. Cognitive Dysfunction in Major Depressive Disorder. Curr. Opin. Psychiatry 2018, 31, 26–31. [CrossRef]

- Semkovska, M.; Quinlivan, L.; O’Grady, T.; Johnson, R.; Collins, A.; O’Connor, J.; Knittle, H.; Ahern, E.; Gload, T. Cognitive Function Following a Major Depressive Episode: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Lancet Psychiatry 2019, 6, 851–861. [CrossRef]

- Varghese, S.; Frey, B.N.; Schneider, M.A.; Kapczinski, F.; de Azevedo Cardoso, T. Functional and Cognitive Impairment in the First Episode of Depression: A Systematic Review. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 2022, 145, 156–185. [CrossRef]

- Bora, E.; Yucel, M.; Pantelis, C. Cognitive Endophenotypes of Bipolar Disorder: A Meta-Analysis of Neuropsychological Deficits in Euthymic Patients and Their First-Degree Relatives. J. Affect. Disord. 2009, 113, 1–20. [CrossRef]

- Christensen, M.V.; Kyvik, K.O.; Kessing, L.V. Cognitive Function in Unaffected Twins Discordant for Affective Disorder. Psychol. Med. 2006, 36, 1119–1129. [CrossRef]

- Ladegaard, N.; Videbech, P.; Lysaker, P.H.; Larsen, E.R. The Course of Social Cognitive and Metacognitive Ability in Depression: Deficit Are Only Partially Normalized after Full Remission of First Episode Major Depression. Br. J. Clin. Psychol. 2016, 55, 269–286. [CrossRef]

- Ladegaard, N.; Lysaker, P.H.; Larsen, E.R.; Videbech, P. A Comparison of Capacities for Social Cognition and Metacognition in First Episode and Prolonged Depression. Psychiatry Res. 2014, 220, 883–889. [CrossRef]

- Bora, E.; Berk, M. Theory of Mind in Major Depressive Disorder: A Meta-Analysis. J. Affect. Disord. 2016, 191, 49–55. [CrossRef]

- Weightman, M.J.; Air, T.M.; Baune, B.T. A Review of the Role of Social Cognition in Major Depressive Disorder. Front. psychiatry 2014, 5, 179. [CrossRef]

- Weightman, M.J.; Knight, M.J.; Baune, B.T. A Systematic Review of the Impact of Social Cognitive Deficits on Psychosocial Functioning in Major Depressive Disorder and Opportunities for Therapeutic Intervention. Psychiatry Res. 2019, 274, 195–212. [CrossRef]

- Uchino, T.; Okubo, R.; Takubo, Y.; Aoki, A.; Wada, I.; Hashimoto, N.; Ikezawa, S.; Nemoto, T. Perceptions of and Subjective Difficulties with Social Cognition in Schizophrenia from an Internet Survey: Knowledge, Clinical Experiences, and Awareness of Association with Social Functioning. Psychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 2022, 76, 429–436. [CrossRef]

- Okubo, R.; Yoshioka, T.; Ohfuji, S.; Matsuo, T.; Tabuchi, T. COVID-19 Vaccine Hesitancy and Its Associated Factors in Japan. Vaccines 2021, 9, 662. [CrossRef]

- Rosenbaum, P.R.; Rubin, D.B. The Central Role of the Propensity Score in Observational Studies for Causal Effects. Biometrika 1983, 70, 41–55. [CrossRef]

- Graux, J.; Thillay, A.; Morlec, V.; Sarron, P.-Y.; Roux, S.; Gaudelus, B.; Prost, Z.; Brénugat-Herné, L.; Amado, I.; Morel-Kohlmeyer, S.; et al. A Transnosographic Self-Assessment of Social Cognitive Impairments (ACSO): First Data. Front. Psychiatry 2019, 10, 847. [CrossRef]

- Sullivan, M.J.; Edgley, K.; Dehoux, E. A Survey of Multiple Sclerosis: I. Perceived Cognitive Problems and Compensatory Strategy Use. Can. J. Rehabil. 1990, 4, 99–105.

- Birchwood, M.; Smith, J.; Cochrane, R.; Wetton, S.; Copestake, S. The Social Functioning Scale. The Development and Validation of a New Scale of Social Adjustment for Use in Family Intervention Programmes with Schizophrenic Patients. Br. J. Psychiatry 1990, 157, 853–859.

- Uchino, T.; Nemoto, T.; Kojima, A.; Takubo, Y.; Kotsuji, Y.; Yamaguchi, E.; Yamaguchi, T.; Katagiri, N.; Tsujino, N.; Tanaka, K.; et al. Effects of Motivation Domains on Social Functioning in Schizophrenia with Consideration of the Factor Structure and Confounding Influences. J. Psychiatr. Res. 2021, 133, 106–112. [CrossRef]

- Nemoto, T.; Fujii, C.; Miura, Y.; Chino, B.; Kobayashi, H.; Yamazawa, R.; Murakami, M.; Kashima, H.; Mizuno, M. Reliability and Validity of the Social Functioning Scale Japanese Version (SFS-J). JPN Bull Soc Psychiat 2008, 17, 188–195.

- Jackson, D.L.; Gillaspy, J.A.; Purc-Stephenson, R. Reporting Practices in Confirmatory Factor Analysis: An Overview and Some Recommendations. Psychol. Methods 2009, 14, 6–23. [CrossRef]

- Schermelleh-Engell, K.; Moosbrugger, H.; Müller, H.; Engell, K. Evaluating the Fit of Structural Equation Models: Tests of Significance and Descriptive Goodness-of Fit Measures. Methods Psychol. Res. Online 2003, 8, 23–74.

- Rossier, J.; Zecca, G.; Stauffer, S.D.; Maggiori, C.; Dauwalder, J.-P. Career Adapt-Abilities Scale in a French-Speaking Swiss Sample: Psychometric Properties and Relationships to Personality and Work Engagement. J. Vocat. Behav. 2012, 80, 734–743. [CrossRef]

- Cheung, G.W.; Rensvold, R.B. Evaluating Goodness-of-Fit Indexes for Testing Measurement Invariance. Struct. Equ. Model. A Multidiscip. J. 2002, 9, 233–255. [CrossRef]

- Krabbendam, L.; Arts, B.; van Os, J.; Aleman, A. Cognitive Functioning in Patients with Schizophrenia and Bipolar Disorder: A Quantitative Review. Schizophr. Res. 2005, 80, 137–149. [CrossRef]

- Schaub, A.; Goerigk, S.; Kim T, M.; Hautzinger, M.; Roth, E.; Goldmann, U.; Charypar, M.; Engel, R.; Möller, H.-J.; Falkai, P. A 2-Year Longitudinal Study of Neuropsychological Functioning, Psychosocial Adjustment and Rehospitalisation in Schizophrenia and Major Depression. Eur. Arch. Psychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 2020, 270, 699–708. [CrossRef]

- Schaub, A.; Neubauer, N.; Mueser, K.T.; Engel, R.; Möller, H.-J. Neuropsychological Functioning in Inpatients with Major Depression or Schizophrenia. BMC Psychiatry 2013, 13, 203. [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Altshuler, L.; Glahn, D.C.; Miklowitz, D.J.; Ochsner, K.; Green, M.F. Social and Nonsocial Cognition in Bipolar Disorder and Schizophrenia: Relative Levels of Impairment. Am. J. Psychiatry 2013, 170, 334–341. [CrossRef]

- Kriesche, D.; Woll, C.F.J.; Tschentscher, N.; Engel, R.R.; Karch, S. Neurocognitive Deficits in Depression: A Systematic Review of Cognitive Impairment in the Acute and Remitted State. Eur. Arch. Psychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 2022. [CrossRef]

- van Neerven, T.; Bos, D.J.; van Haren, N.E. Deficiencies in Theory of Mind in Patients with Schizophrenia, Bipolar Disorder, and Major Depressive Disorder: A Systematic Review of Secondary Literature. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2021, 120, 249–261. [CrossRef]

- Weiss, E.M.; Deisenhammer, E.A.; Fink, A.; Marksteiner, J.; Canazei, M.; Papousek, I. Disorder-Specific Profiles of Self-Perceived Emotional Abilities in Schizophrenia and Major Depressive Disorder. Brain Sci. 2022, 12. [CrossRef]

- Upthegrove, R.; Marwaha, S.; Birchwood, M. Depression and Schizophrenia: Cause, Consequence, or Trans-Diagnostic Issue? Schizophr. Bull. 2017, 43, 240–244. [CrossRef]

- Sönmez, N.; Romm, K.L.; Andreasssen, O.A.; Melle, I.; Røssberg, J.I. Depressive Symptoms in First Episode Psychosis: A One-Year Follow-up Study. BMC Psychiatry 2013, 13, 106. [CrossRef]

- Michelini, G.; Palumbo, I.M.; DeYoung, C.G.; Latzman, R.D.; Kotov, R. Linking RDoC and HiTOP: A New Interface for Advancing Psychiatric Nosology and Neuroscience. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2021, 86, 102025. [CrossRef]

- Shah, J.L.; Scott, J.; McGorry, P.D.; Cross, S.P.M.; Keshavan, M.S.; Nelson, B.; Wood, S.J.; Marwaha, S.; Yung, A.R.; Scott, E.M.; et al. Transdiagnostic Clinical Staging in Youth Mental Health: A First International Consensus Statement. World Psychiatry 2020, 19, 233–242. [CrossRef]

- Machlitt-Northen, S.; Keers, R.; Munroe, P.B.; Howard, D.M.; Pluess, M. Gene-Environment Correlation over Time: A Longitudinal Analysis of Polygenic Risk Scores for Schizophrenia and Major Depression in Three British Cohorts Studies. Genes (Basel). 2022, 13. [CrossRef]

- Cross-Disorder Group of the Psychiatric Genomics Consortium Identification of Risk Loci with Shared Effects on Five Major Psychiatric Disorders: A Genome-Wide Analysis. Lancet 2013, 381, 1371–1379. [CrossRef]

- Schulze, T.G.; Akula, N.; Breuer, R.; Steele, J.; Nalls, M.A.; Singleton, A.B.; Degenhardt, F.A.; Nöthen, M.M.; Cichon, S.; Rietschel, M.; et al. Molecular Genetic Overlap in Bipolar Disorder, Schizophrenia, and Major Depressive Disorder. World J. Biol. Psychiatry 2014, 15, 200–208. [CrossRef]

- Ma, M.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, X.; Yan, H.; Zhang, D.; Yue, W. Common and Distinct Alterations of Cognitive Function and Brain Structure in Schizophrenia and Major Depressive Disorder: A Pilot Study. Front. psychiatry 2021, 12, 705998. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).