1. Introduction

The pandemic of Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) that started from the late December of 2019 and continued affected mental health of people all over the world [

1]. The most affected population was health care workers who suffered from an increased workload to care patients, worry about a high risk of infection by COVID-19, and stigma and discrimination from the community. It is reported that healthcare professionals experienced high levels of depression, anxiety, and posttraumatic stress symptoms [

2,

3]. In particular, nurses experienced poorer mental health than other healthcare professionals during the COVID-19 pandemic [

2,

4]. It is important to improve mental health of nurses in the midst of the continuing COVID-19 pandemic to make their quality of working life better, and to ensure a workforce to provide health care responding to the COVID-19 by preventing sick leave or early retirement due to poor mental health such as burnout.

In a previous infectious disease epidemic, limited research shows effective interventions among health care workers [

3,

5]: a training on Psychological First Aid improved burnout of primary health care workers in the community during the Ebola epidemic [

6]; a comprehensive organizational intervention including infection measures, infection protection training, and psychological support teams for patients and healthcare workers improved depression and sleep of nurses in a hospital in the SARS outbreak [

7]. A few additional studies reported positive responses to a group-based resilience training at a post-survey [

8] and an improvement of self-efficacy and interpersonal problems after taking a web-based resilience training program among healthcare workers in the pandemic influenza [

9].

Since a close face-to-face personal contact is limited in order to prevent COVID-19 infection in an organization or community, using information and communication technology (ICT) to provide training on stress management skills, such as Internet stress management programs [

10,

11], has been encouraged [

12,

13]. Internet programs have also a merit in its accessibility, low-cost, and confidentiality. A previous randomized controlled trial (RCT) reported that an Internet cognitive behavioral therapy (iCBT) program reduced perceived work-related stress among nurses in the US [

14]. We also found that a self-guided iCBT program reduced depression of nurses in Vietnam at 3-month follow-up [

15]. However, these studies were conducted before the COVID-19 pandemic. A recent study in the COVID-19 pandemic reported that an Internet stress management program based on psychoeducation and mindfulness skill training yielded no significant effect on depression, anxiety, or stress at post-intervention among health care workers in Spain [

16]. It is unclear if iCBT programs are effective in improving mental health of health care workers during the COVID-19 pandemic, where health care workers experienced much higher stress than usual.

South-East Asia is one of populous geographical areas in the worlds, where a rapid aging of the society is going on. The shortage of health care workforce has been serious in this region even before the COVID-19 [

17]. To date, the region had a largest total number of mortality due to COVID-19 following Europe and Americas [

18]. We intend to test the effectiveness of a smart-phone iCBT stress management program on improving mental health of nurses in this region in the COVID-19 pandemic, by using a modified version of our previous iCBT program for nurses in Vietnam [

15,

19] adapted to the COVID-19 situations. To increase the generalizability of the study finding, we select two rapidly industrialized middle-income countries of the region, i.e. Vietnam and Thailand, to conduct the effectiveness study as a part of the “COping with COVID-19 helps Nurses to be Active, Tough, and Smiling” (COCONATS) project.

The objective of the present randomized controlled trial (RCT) is to investigate the effectiveness of a smart-phone iCBT stress management program on depression and other health- and work-related outcomes of nurses in Vietnam and Thailand in the COVID-19 epidemic.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Trial design

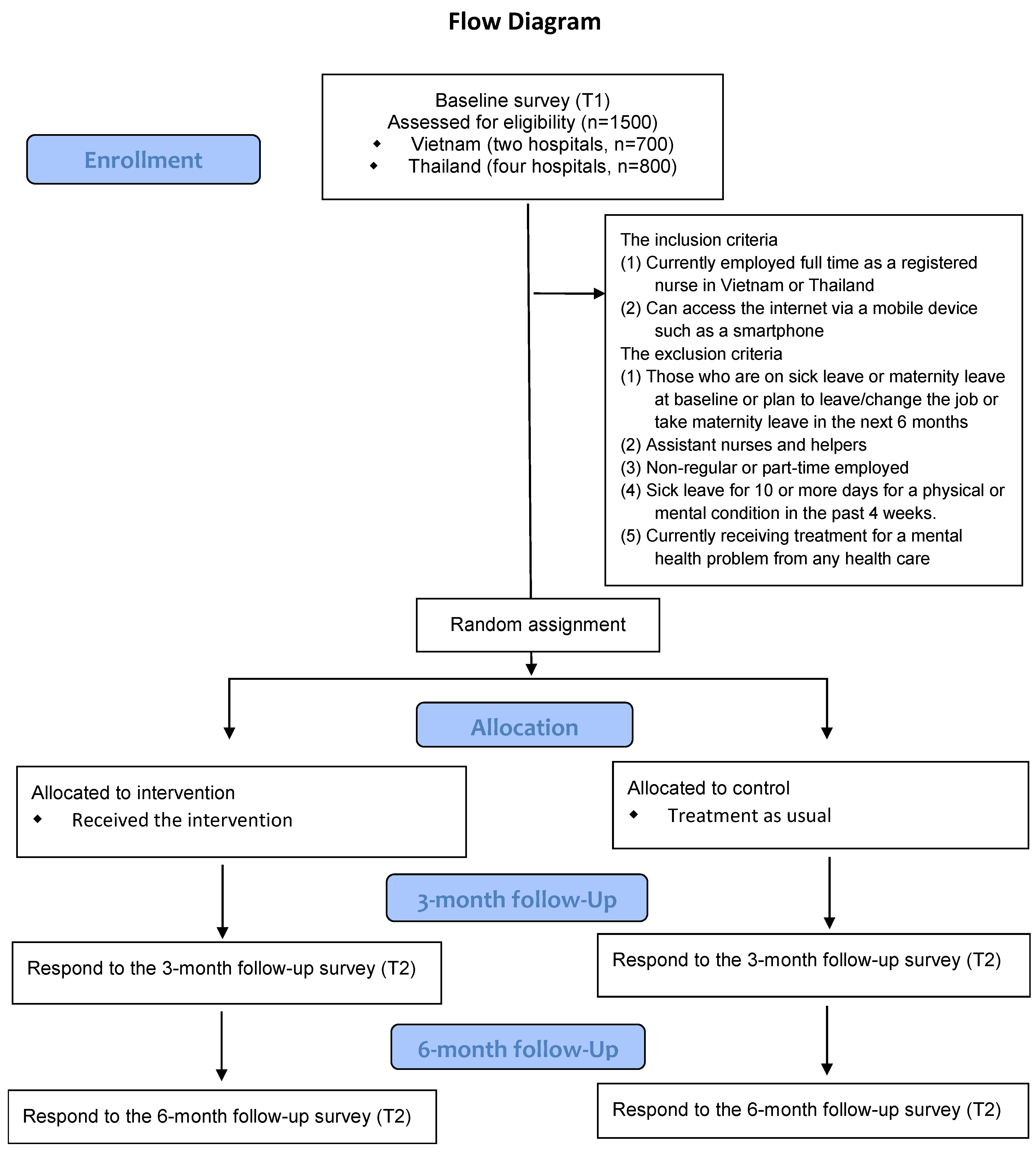

A two-arm RCT with intervention and control groups will be conducted. Participants in the intervention group will be invited to access the program for 6 months. The control group participants will not access to the program until the six-month follow-up survey is done, but receive occupational health and other services in their organizations (treatment as usual). Online questionnaire surveys will be conducted of both intervention and control groups at baseline, 3- and 6-month follow-ups. The study protocol was registered at the UMIN Clinical Trials Registry (UMIN-CTR; ID= UMIN000044145) (version 9, dated on August 17, 2021; last updated on Aug 17, 2022). This protocol manuscript was reported according to the SPIRIT guideline checklist [

20].

2.2. Participants

The target population of the study is nurses working in hospitals in Vietnam and Thailand. Full-time employed nurses in the two countries who meet the following inclusion and exclusion criteria will be invited to participate in the study:

The inclusion criteria

(1) Currently employed full time as a registered nurse in Vietnam or Thailand

(2) Can access the internet via a mobile device such as a smartphone

The exclusion criteria

(1) Those who are on sick leave or maternity leave at baseline or plan to leave/change the job or take maternity leave in the next 6 months

(2) Assistant nurses and helpers

(3) Non-regular or part-time employed

(4) Sick leave for 10 or more days for a physical or mental condition in the past 4 weeks.

(5) Currently receiving treatment for a mental health problem from any health care professional.

2.3. Procedure

In Vietnam, one hospital in Hanoi and another province hospital in the north of Hanoi will be selected as a study field. All nurses (n=700) in these hospitals who meet the following inclusion and exclusion criteria will be invited to participate in the study. In Thailand, a total of four provincial hospitals at tertiary level and above, located in Bangkok and in the central part of Thailand, will be selected as a study field. A total of 800 nurses will be recruited from four hospitals (200 from each hospital) on a voluntary basis.

In Vietnam, researchers of Hanoi University of Public Health (HUPH) will approach to potential target hospitals and send paper broachers to all registered nurses in the target hospitals and recruit potential participants of the study. Researchers of HUPH will send a paper questionnaire or the link to an online questionnaire to them. Informed consent will be obtained face-to-face or online from each possible participant, after providing a document explaining the aim and procedure of the study. The name and contact information (e-mail or SMS) of participants will be collected and kept confidential in HUPH University. Those who agreed to participate in the study will be also asked to complete the baseline survey online or paper-based.

In Thailand, researchers of Mahidol University will approach local collaborators of the target hospitals and send paper broachers to introduce the research project to nurses employed in the target hospitals 1 month prior to recruitment process. The local collaborators will introduce the research project, recruit potential participants, and obtain informed consent face-to-face after providing a document explaining the aim and procedure of the study. The name and contact information (e-mail or SMS) of participants will be collected and kept confidential in Mahidol University. Researchers of Mahidol University will send the link to an online questionnaire to the participants, asking to complete the baseline survey.

These participants in both countries will be randomly allocated to either the intervention group or the control group (

Figure 1). Participants in the intervention group will be asked to study the intervention program for 10 weeks after the baseline survey.

2.4. Intervention program

A 7-week smartphone-based self-guided stress management program for nurses in the COVID-19 pandemic in Vietnam and Thailand, “the ABC Stress Management” – COVID-19 version, will be developed. Briefly, the program included seven modules. The modules will be presented in a fixed order, with one module accessible per week, from module 1 to module 7. Theme of each module is as follows: a transactional model of stress and coping (module 1), self-case formulation based on cognitive behavioral model (module 2), behavioral activation (module 3), cognitive restructuring (module 4), cognitive restructuring and relaxation (module 5), problem-solving (module 6); and stress and coping for better mental health in the COVID-19 pandemic (module 7). These modules will be translated into Vietnamese and Thai languages.

The modules 1-6 will be developed using the modules of a previous iCBT program that successfully reduced depression at 3-month follow-up among nurses in Vietnam [

15,

19]. The seventh module will be newly developed to specifically teach awareness of stress and coping with stress in the COVID-19 pandemic, based on the literature review and other information sources [

21,

22,

23,

24], as well as local experiences in the COVID-19 pandemic.

2.5. Intervention group

After the baseline survey, before staring the intervention, researchers of HUPH and Mahidol University will explain the intervention group how to use the program. Then, participants in the intervention groups will be invited to study the intervention program for 10 weeks. During the first seven weeks, the intervention group will be notified every week via e-mail or message/chat app that a new module is available. When a participant does not complete a module within a week, he/she will receive an e-mail reminder to encourage them to complete the module. After the first 7 weeks, the participants in the intervention group will be allowed to access to the program during the additional 3 weeks. If a participant still does not complete all modules, he/she will receive an e-mail or SMS reminder to complete the program. Ten weeks after the baseline survey, the intervention program will be closed.

2.6. Control group

Participants in the control group will not receive any intervention program during the first 6 months. Participants in both the intervention group and the control group will be able to use an internal occupational health service and/or employee assistance program service. Participants in the control group will be provided a chance to use the intervention program after the study.

2.7. Outcomes

All outcome variables will be measured of both the intervention and control groups by using online or paper-based questionnaires at baseline and the 3- and 6-month follow-ups.

Primary outcome

The primary outcome is depression which will be measured by DASS21 at baseline, 3- and 6-month follow-ups. The DASS is a screening tool to assess depression, was well as anxiety and stress in the last 7 days [

25]. Vietnamese and Thai versions of DASS 21 has been developed and tested, and its internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha) and validity [

26,

27]. The depression subscale consists of 7 items measuring dysphoria, hopelessness, and devaluation of life, among others. Each Items are scored on a 4-point scale ranging from 0 (did not apply to me at all) to 3 (applied to me very much, or most of the time). The DASS21 depression score ranged from 0 to 21, with a cut-off score 10 or more [

27].

Secondary outcomes

The secondary outcomes include the following variable to be measured at baseline, 3- and 6-month follow-ups: Fear of COVID-19, psychological distress, anxiety and stress symptoms, work engagement, burnout, health-related quality of life (QOL), sick leave, work performance, intention to leave, quality of nursing care (self-reported).

Fear of COVID-19 will be measured by Fear of COVID-19 Scale [

28] [for Vietnamese [

29] and Thai [

30]]. Psychological distress will be measured by Kessler 6 (K6) scale [

31] [for Vietnamese [

32] and Thai [

33]]. Anxiety and stress symptoms will be measured corresponding subscales of DASS21 [

25] [for Vietnamese, [

27] and Thai [

34]]. Work engagement will be measured by using the 9-item Utrecht Work Engagement Scale (UWES) [

35] [for Vietnamese [

36] and Thai [

37]]. Burnout will be measured by the Copenhagen Burnout Inventory (CBI) [

38] [for Thai [

39]]. The CBI will be translated into Vietnamese and the back-translation will be checked by the original author, with a standardized procedure [

40]. Health-related QOL will be measured by EQ-5D-5L [

41] [for Vietnamese [

42] and Thai [

43]]. The number of sick leave days and work performance (0-10 scale) in the past 4 weeks will be asked using one-item questions adopted from WHO-HPQ [

44]. Both intention to leave the profession and intention to leave the organization will be measured by the following questions [

45]: for intention to leave the profession “How often during the course of the past 3 MONTHS have you thought about giving up nursing?” with 5 response options, (1) ‘never’, (2) ‘sometimes in 3 months’, (3) ‘sometimes a month’, (4) ‘sometimes a week’, (5) ‘every day; for intention to leave the organization, “How often during the course of the past 3 months have you thought about leaving the organization?” with the same 5 response options. The self-reported quality of nursing care was measured by sing a single question [

46]: “How would you describe the quality of nursing care you delivered in the last month?” with 4 response options, 1. Excellent, 2. Good, 3. Fair, and 4. Poor. The questions of intention to leave and self-reported quality of nursing care will be newly translated for Vietnamese and Thai languages.

2.8. Usage data and implementation outcome

Information on the usage of the intervention program by participants in the intervention group will be collected from the records of the server system. Implementation outcomes will be measured with the user version of the Implementation Outcome Scales for Digital Mental Health (iOSDMH) [

47], a 19-item scale, with a 4-point Likert-type response option: 3 items for acceptability; 4 items for appropriateness; 6 items for feasibility; 5 items for harms; and one item for overall satisfaction. The iOSDMH will be translated into Vietnamese and Thai language. Participants in the intervention group will be asked to complete the iOSDMH at 3-month follow-up.

2.9. Demographic and other characteristics

Demographic data, such as sex, age, education, marital status, type of employment contract, work unit, personal income, and chronic physical condition will be collected. Their work experiences related to COVID-19 will be also asked, such as state of vaccination and contact to a patient with COVID-19.

2.10. Sample size calculation

A required sample size was calculated for the primary outcome variable, i.e., DASS21 depression score. Previous meta-analyses of web-based universal prevention psychological intervention on improving depression and anxiety in the workplace yielded a summary effect size of 0.25 [

48]. Our previous study of an unguided universal prevention iCBT program among nurses in Vietnam reported a small effect size on depression (d=0.18 at 3-month follow-up) [

49]. To detect a minimal effect size of 0.15 at an alpha of 0.05 and a power of 0.80, the estimated sample size was 699 participants in each group. It will be required to collect 1,398 participants in total, combining samples from the two countries. The statistical power was calculated using the G*Power 3 program.

2.11. Randomization

Participants who meet the inclusion criteria will be randomly allocated to the intervention or control group, with being stratified by a country (Vietnam or Thailand), hospitals, and subgroups based on DASS21 depression scores at baseline (10 or greater and less than 10) [

27]. An independent biostatistician (YM) will generate a password-protected stratified permuted block random table by using the SAS (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA). An independent research assistant in The University of Tokyo will conduct the assignment, using the stratified permuted-block random table which is blinded to the researchers.

2.12. Statistical methods

For the primary outcome and the secondary outcomes, a mixed model analysis for repeated measures will be used to test the intervention effect (group × time interactions) for 3- and 6-month follow-ups in the total sample (both from Vietnam and Thailand)), on an intention-to-treat basis, with imputing missing data with restricted maximum likelihood estimation assuming missing values at random. Effect sizes (Cohen ds) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) at 3- and 6-month follow-ups will be calculated among those who completed the baseline and follow-up surveys. All statistical analyses will be conducted using the SPSS Statistics V.26.0 (IBM Corp., USA).

The effectiveness of the program may be greater for participants with depression at baseline. We will conduct similar mixed model analyses for the effectiveness of the program among subgroups with and without symptoms of depression at baseline (with DASS21 depression score of 10 or greater) (indicated prevention). The analyses of a total sample and subgroups will be also conducted separately for Vietnam and Thailand.

2.13. Ethical considerations

The study procedures have been approved by the Research Ethics Review Board of Graduate School of Medicine/Faculty of Medicine, The University of Tokyo (no 32021082NI-(1)), Hanoi University of Public Health (no 353/2021/YTCC-HD3 dated on 06/9/2021), and Mahidol University (MU MOU COA No. 2021-001 dated on October 06, 2021). Informed consent will be obtained by clinical research coordinators (CRCs) from all participants included in this study after full disclosure and explanation of the purpose and procedures of the study. Candidate participants will be informed that their participation is totally voluntary, and that even after voluntarily participating they can withdraw from the study at any time without stating the reason, and that neither participation nor withdrawal will cause any advantage or disadvantage to them. We expect no adverse health effects from this intervention, except possibly for slight deterioration in depressive/anxiety symptoms. We will provide the phone number and e-mail address of each research office. A research assistant will deal with the emergency calls or e-mails first, and then consult with the supervisors (HTN, OK) to provide appropriate care.

Participants will complete baseline and follow-up online questionnaires on a specially designed website. Researchers will collect name, phone number, and e-mail address to identify each participant. The personal identifying information will be stored confidentially in each country research center and used only for the study. Collected data from the questionnaire will be anonymized, linked, and stored in a password-locked file by the CRC and analyzed by researches in each country and researchers of the University of Tokyo.

2.14. Amendments of the trial registration

All these items of the study protocol were fixed before Feb 9, 2022. However, some of the items were not reflected on the UMIN Clinical Trials Registry system due to a technical error, and corrected on Aug 16-17, 2022. An item of the exclusion criteria was corrected from “(5) Currently receiving treatment for a mental health problem from a mental health professional.” to “(5) Currently receiving treatment for a mental health problem from any health care professional.” In the version 8 (Aug 16, 2022); the target sample size was corrected from 1200 to 1500 in the version 7 (Aug 16, 2022); Copenhagen Burnout Inventory (CBI) was correctly added in the version 9 (Aug 17, 2022); the duration of the intervention was corrected from “Participants will be allowed to study the program for 3 months from the beginning.” to “Participants will be allowed to study the program for 10 weeks from the beginning.” on the version 6 (Aug 16, 2022)

3. Results

The recruitment of the participants, the baseline survey, and the intervention were done by May 2022; all follow-ups were completed by November 2022. Data cleaning started in December 2022. The final analysis will be conducted after March-April 2023. We expect to publish the results in 2023.

4. Discussion

This is the first intervention trial to investigate the effectiveness of a smartphone-based self-guided iCBT stress management program on improving symptoms of depression among hospital nurses in selected South-East Asian countries (Vietnam and Thailand) in the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic, using a RCT design. The intervention program will consist of same components of cognitive-behavioral skills such as cognitive restructuring, behavioral activation, and problem solving as for one that was previously effective in reducing depression among hospital nurses in Vietnam before the COVID-19 pandemic [

15,

19]. Moreover, we will add a new module that connects these skills with coping with stress in the COVID-19 situation. The program could be effective for reducing depression among hospital nurses even in the COVID-19 pandemic where nurses would experience higher levels of stress than before.

The other unique point of this trial is that it will be a multi-country trial including two parallel trials in Vietnam and Thailand. The first merit of the study design is that it allows us to recruit a large sample in the study. The primary analysis combining samples from the two countries will achieve enough power (0.80) to detect a small effect size (0.15). It would be interesting to observe similar effectiveness of the intervention study in the two countries. These two countries have different languages, cultures, political systems, while the countries share common social and cultural features as these countries are geographically close in the Indochina Peninsula, and a long-time historical interaction. It would increase the generalizability of the effectiveness of the intervention program to multiple countries in this region.

Research is limited concerning effective interventions to improve mental health of health care workers in the COVID-19 pandemic. A previous trial failed to show a significant improvement of depression, anxiety, and stress symptoms of health care workers in Spain by using an Internet psychoeducational and mindfulness intervention program [

16], while it did find a significant improvement among participants already with poor mental health, i.e., who used psychotropic medication. If our trial finds that the iCBT stress management program is effective in reducing depression and improving other outcomes in the total sample, it would suggest that the universal prevention approach is useful to improve mental health of hospital nurses. In that case, the iCBT stress management program may be used as a skill training to enhance coping ability of hospital nurses against stress due to the COVID-19 pandemic.

The main findings of this study will be disseminated via presentations at conferences and publications in peer-reviewed international journals. If the program is effective, a future plan to disseminate the program to hospital nurses in Vietnam and Thailand will be discussed with the government, non-profit organizations, and corporations.

Limitations

Major weaknesses of this study includes that the trial will not be double-blinded, because researchers know who participants are in the intervention group, and participants know if they are in the intervention or control group. This will make vulnerable to information bias. The other possible weakness is that, because we will randomize individuals in a workplace, the psychoeducational information provided by the program may be shared among friends and colleagues. Such a contamination could result in underestimation of the effect of the program. In addition, the iCBT stress management program may have a smaller effect in the COVID-19 pandemic than in our trial before the pandemic [

15], because hospital nurses would be more stressful. Even before the pandemic, the effect of the program was seen only at 3 months, but not at 6 months [

15]. The program may be minimally effective or effective only for a short period. While we are interested in comparing the effectiveness of the program between the two countries, the study design will be slightly difference for the two countries: e.g., sampling all nurses in hospitals in Vietnam and recruiting volunteers from hospitals in Thailand. The other features of the trial may cause the differential effectiveness, such as the quality of language translation and set up of the modules, frequency and mode of reminders, etc. We should be careful in interpreting the findings of the trial considering these possible limitations.

5. Conclusions

This is the first multi-country study to investigate the effectiveness of a self-guided smart-phone stress management program on improving depression and other outcomes among hospital nurses in South-East Asia (Vietnam and Thailand), using a RCT design. The study will explore the potential of a digital mental health intervention that can be disseminated without face-to-face contact to a large number of nurses who experience stress in the COVID-19 pandemic.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org, Table S1: The COCONATS study protocol-SPIRIT-Checklist

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, N.K. H.T.N. O.K. K.I. K.W. and A.T.; methodology, T.T.T.T. N.Sr., P.B. Q.T.N. N.Sa., T.T. K.I. Y.T. A,S. and D.N.; data curation, H.T.N. T.T.T.T. N.T.N. V.T.S. T.T.N. T.T.L. L.D.N. N.T.V.N. B.T.N. O.K. P.B. N.Sr., and T.T.; writing—original draft preparation, N.K.; writing—review and editing, H.T.H and O.K.; project administration, M.I. and H.A..; funding acquisition, N.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by the Grants-in-Aid for Scientific Research (KAKENHI) Fund for the Promotion of Joint International Research (Fostering Joint International Research (B)) from Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS) 2020-2022 (JSPS KAKENHI Grant/Award Number: 20KK0215). The funder has no role in designing, acquiring, analyzing the data.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study procedures have been approved by the Research Ethics Review Board of Graduate School of Medicine/Faculty of Medicine, The University of Tokyo (no 32021082NI-(1)), Hanoi University of Public Health (no 353/2021/YTCC-HD3 dated on 06/9/2021), and Mahidol University (MU MOU COA No. 2021-001 dated on October 06, 2021).

Informed Consent Statement

Written informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

N/A

Conflicts of Interest

NK is a board member of Junpukai Foundation, and receives personal fees from Riken Institute, JAXA, Sekisui Chemical Co. Ltd, and SB@Work, outside the submitted work. NK, IK, AS are employed in Department of Digital Mental Health which is an endowment department, supported with an unrestricted grant from 15 enterprises (

https://dmh.m.u-tokyo.ac.jp/c).

References

- Cénat, J.M.; Blais-Rochette, C.; Kokou-Kpolou, C.K.; Noorishad, P.G.; Mukunzi, J.N.; McIntee, S.E.; Dalexis, R.D.; Goulet, M.A.; Labelle, P.R. Prevalence of Symptoms of Depression, Anxiety, Insomnia, Posttraumatic Stress Disorder, and Psychological Distress among Populations Affected by the Covid-19 Pandemic: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Psychiatry Res 2021, 295, 113599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pappa, S.; Ntella, V.; Giannakas, T.; Giannakoulis, V.G.; Papoutsi, E.; Katsaounou, P. Prevalence of Depression, Anxiety, and Insomnia among Healthcare Workers During the Covid-19 Pandemic: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Brain Behav Immun 2020, 88, 901–907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Serrano-Ripoll, M.J.; Meneses-Echavez, J.F.; Ricci-Cabello, I.; Fraile-Navarro, D.; Fiol-deRoque, M.A.; Pastor-Moreno, G.; Castro, A.; Ruiz-Perez, I.; Zamanillo Campos, R.; Goncalves-Bradley, D.C. Impact of Viral Epidemic Outbreaks on Mental Health of Healthcare Workers: A Rapid Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J Affect Disord 2020, 277, 347–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muller, A.E.; Hafstad, E.V.; Himmels, J.P.W.; Smedslund, G.; Flottorp, S.; Stensland, S.; Stroobants, S.; Van de Velde, S.; Vist, G.E. The Mental Health Impact of the Covid-19 Pandemic on Healthcare Workers, and Interventions to Help Them: A Rapid Systematic Review. Psychiatry Res 2020, 293, 113441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pollock, A.; Campbell, P.; Cheyne, J.; Cowie, J.; Davis, B.; McCallum, J.; McGill, K.; Elders, A.; Hagen, S.; McClurg, D.; Torrens, C.; Maxwell, M. Interventions to Support the Resilience and Mental Health of Frontline Health and Social Care Professionals During and after a Disease Outbreak, Epidemic or Pandemic: A Mixed Methods Systematic Review. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2020, 11, Cd013779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sijbrandij, M.; Horn, R.; Esliker, R.; O'May, F.; Reiffers, R.; Ruttenberg, L.; Stam, K.; de Jong, J.; Ager, A. The Effect of Psychological First Aid Training on Knowledge and Understanding About Psychosocial Support Principles: A Cluster-Randomized Controlled Trial. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2020, 17, 484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, R.; Chou, K.R.; Huang, Y.J.; Wang, T.S.; Liu, S.Y.; Ho, L.Y. Effects of a Sars Prevention Programme in Taiwan on Nursing Staff's Anxiety, Depression and Sleep Quality: A Longitudinal Survey. Int J Nurs Stud 2006, 43, 215–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aiello, A.; Khayeri, M.Y.; Raja, S.; Peladeau, N.; Romano, D.; Leszcz, M.; Maunder, R.G.; Rose, M.; Adam, M.A.; Pain, C.; Moore, A.; Savage, D.; Schulman, R.B. Resilience Training for Hospital Workers in Anticipation of an Influenza Pandemic. J Contin Educ Health Prof 2011, 31, 15–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maunder, R.G.; Lancee, W.J.; Mae, R.; Vincent, L.; Peladeau, N.; Beduz, M.A.; Hunter, J.J.; Leszcz, M. Computer-Assisted Resilience Training to Prepare Healthcare Workers for Pandemic Influenza: A Randomized Trial of the Optimal Dose of Training. BMC Health Serv Res 2010, 10, 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joyce, S.; Modini, M.; Christensen, H.; Mykletun, A.; Bryant, R.; Mitchell, P.B.; Harvey, S.B. Workplace Interventions for Common Mental Disorders: A Systematic Meta-Review. Psychol Med 2016, 46, 683–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan Mohd Yunus, W.M.A.; Musiat, P.; Brown, J.S.L. Systematic Review of Universal and Targeted Workplace Interventions for Depression. Occup Environ Med 2018, 75, 66–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giorgi, G.; Lecca, L.I.; Alessio, F.; Finstad, G.L.; Bondanini, G.; Lulli, L.G.; Arcangeli, G.; Mucci, N. Covid-19-Related Mental Health Effects in the Workplace: A Narrative Review. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2020, 17, 7857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Yang, L.; Zhang, C.; Xiang, Y.T.; Liu, Z.; Hu, S.; Zhang, B. Online Mental Health Services in China During the Covid-19 Outbreak. Lancet Psychiatry 2020, 7, e17–e18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hersch, R.K.; Cook, R.F.; Deitz, D.K.; Kaplan, S.; Hughes, D.; Friesen, M.A.; Vezina, M. Reducing Nurses' Stress: A Randomized Controlled Trial of a Web-Based Stress Management Program for Nurses. Appl Nurs Res 2016, 32, 18–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Imamura, K.; Tran, T.T.T.; Nguyen, H.T.; Sasaki, N.; Kuribayashi, K.; Sakuraya, A.; Bui, T.M.; Nguyen, A.Q.; Nguyen, Q.T.; Nguyen, N.T.; Nguyen, K.T.; Nguyen, G.T.H.; Tran, X.T.N.; Truong, T.Q.; Zhang, M.W.; Minas, H.; Sekiya, Y.; Watanabe, K.; Tsutsumi, A.; Kawakami, N. Effect of Smartphone-Based Stress Management Programs on Depression and Anxiety of Hospital Nurses in Vietnam: A Three-Arm Randomized Controlled Trial. Sci Rep 2021, 11, 11353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fiol-DeRoque, M.A.; Serrano-Ripoll, M.J.; Jiménez, R.; Zamanillo-Campos, R.; Yáñez-Juan, A.M.; Bennasar-Veny, M.; Leiva, A.; Gervilla, E.; García-Buades, M.E.; García-Toro, M.; Alonso-Coello, P.; Pastor-Moreno, G.; Ruiz-Pérez, I.; Sitges, C.; García-Campayo, J.; Llobera-Cánaves, J.; Ricci-Cabello, I. A Mobile Phone-Based Intervention to Reduce Mental Health Problems in Health Care Workers During the Covid-19 Pandemic (Psycovidapp): Randomized Controlled Trial. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth 2021, 9, e27039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guilbert, J.J. The World Health Report 2006: Working Together for Health. Educ Health (Abingdon) 2006, 19, 385–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. WHO Coronavirus (Covid-19) Dashboard. Available online: https://covid19.who.int (accessed on 19 March 2023).

- Imamura, K.; Tran, T.T.T.; Nguyen, H.T.; Kuribayashi, K.; Sakuraya, A.; Nguyen, A.Q.; Bui, T.M.; Nguyen, Q.T.; Nguyen, K.T.; Nguyen, G.T.H.; Tran, X.T.N.; Truong, T.Q.; Zhang, M.W.B.; Minas, H.; Sekiya, Y.; Sasaki, N.; Tsutsumi, A.; Kawakami, N. Effects of Two Types of Smartphone-Based Stress Management Programmes on Depressive and Anxiety Symptoms among Hospital Nurses in Vietnam: A Protocol for Three-Arm Randomised Controlled Trial. BMJ Open 2019, 9, e025138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chan, A.W.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Gøtzsche, P.C.; Altman, D.G.; Mann, H.; Berlin, J.A.; Dickersin, K.; Hróbjartsson, A.; Schulz, K.F.; Parulekar, W.R.; Krleza-Jeric, K.; Laupacis, A.; Moher, D. Spirit 2013 Explanation and Elaboration: Guidance for Protocols of Clinical Trials. BMJ 2013, 346, e7586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inter-Agency Standing Committee (IASC). IASC Guidance on Basic Psychosocial Skills- a Guide for Covid-19 Responders; Inter-Agency Standing Committee (IASC), 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Mind. Available online: https://www.mentalhealthatwork.org.uk/resource/how-to-look-after-your-mental-health/ (accessed on 19 March 2023).

- Royal College of Psychiatrists. Covid-19: Guidance for Clinicians. Available online: https://www.rcpsych.ac.uk/about-us/responding-to-covid-19/responding-to-covid-19-guidance-for-clinicians (accessed on 19 March 2023).

- U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Healthcare Personnel and First Responders: How to Cope with Stress and Build Resilience During the Covid-19 Pandemic. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/hcp/mental-health-healthcare.html (accessed on 19 March 2023).

- Henry, J.D.; Crawford, J.R. The Short-Form Version of the Depression Anxiety Stress Scales (Dass-21): Construct Validity and Normative Data in a Large Non-Clinical Sample. Br J Clin Psychol 2005, 44 Pt 2, 227–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Supasiri, T.; Lertmaharit, S.; Rattananupong, T.; Kitidumrongsuk, P.; Lohsoonthorn, V. Mental Health Status and Quality of Life of the Elderly in Rural Saraburi. Chulalongkorn Medical Journal 2019, 62, 95–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, T.D.; Tran, T.; Fisher, J. Validation of the Depression Anxiety Stress Scales (Dass) 21 as a Screening Instrument for Depression and Anxiety in a Rural Community-Based Cohort of Northern Vietnamese Women. BMC Psychiatry 2013, 13, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahorsu, D.K.; Lin, C.Y.; Imani, V.; Saffari, M.; Griffiths, M.D.; Pakpour, A.H. The fear of Covid-19 Scale: Development and Initial Validation. Int J Ment Health Addict 2022, 20, 1537–1545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, H.T.; Do, B.N.; Pham, K.M.; Kim, G.B.; Dam, H.T.B.; Nguyen, T.T.; Nguyen, T.T.P.; Nguyen, Y.H.; Sørensen, K.; Pleasant, A.; Duong, T.V. Fear of COVID-19 Scale-Associations of Its Scores with Health Literacy and Health-Related Behaviors among Medical Students. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2020, 17, 4164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karawekpanyawong, N.; Likhitsathian, S.; Juntasopeepun, P.; Reznik, A.; Srisurapanont, M.; Isralowitz, R. Thai Medical and Nursing Students: COVID-19 Fear Associated with Mental Health and Substance Use. Journal of Loss and Trauma 2022, 27, 474–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kessler, R.C.; Andrews, G.; Colpe, L.J.; Hiripi, E.; Mroczek, D.K.; Normand, S.L.; Walters, E.E.; Zaslavsky, A.M. Short Screening Scales to Monitor Population Prevalences and Trends in Non-Specific Psychological Distress. Psychol Med 2002, 32, 959–976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kawakami, N.; Thi Thu Tran, T.; Watanabe, K.; Imamura, K.; Thanh Nguyen, H.; Sasaki, N.; Kuribayashi, K.; Sakuraya, A.; Thuy Nguyen, Q.; Thi Nguyen, N.; Minh Bui, T.; Thi Huong Nguyen, G.; Minas, H.; Tsutsumi, A. Internal Consistency Reliability, Construct Validity, and Item Response Characteristics of the Kessler 6 Scale among Hospital Nurses in Vietnam. PLoS One 2020, 15, e0233119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suraaroonsamrit, B.; Arunpongpaisal, S. Reliability and Validity Testing of the Thai Version of Kessler 6-Item Psychological Distress Questionnaire. J Psychiatr Assoc Thailand 2014, 59, 299–312. [Google Scholar]

- Psychology Foundation of Australia. DASS21 Website. Available online: http://www2.psy.unsw.edu.au/groups/dass/ (accessed on 19 March 2023).

- Schaufeli, W.B.; Salanova, M.; González-romá, V.; Bakker, A.B. The Measurement of Engagement and Burnout: A Two Sample Confirmatory Factor Analytic Approach. J Happiness Stud 2002, 3, 71–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, T.T.T.; Watanabe, K.; Imamura, K.; Nguyen, H.T.; Sasaki, N.; Kuribayashi, K.; Sakuraya, A.; Nguyen, N.T.; Bui, T.M.; Nguyen, Q.T.; Truong, T.Q.; Nguyen, G.T.H.; Minas, H.; Tsustumi, A.; Shimazu, A.; Kawakami, N. Reliability and Validity of the Vietnamese Version of the 9-Item Utrecht Work Engagement Scale. J Occup Health 2020, 62, e12157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oraphan, T. The Effect of Job Demands, Job Resources, and Off-Job Recovery on Mental and Physical Health among Registered Nurses in Thailand [Unpublished Phd’s Thesis]. The University of Tokyo, Tokyo, 2020. [CrossRef]

- Kristensen, T.S.; Borritz, M.; Villadsen, E.; Christensen, K.B. The Copenhagen Burnout Inventory: A New Tool for the Assessment of Burnout. Work & Stress 2005, 19, 192–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wongtrakul, W.; Dangprapai, Y.; Saisavoey, N.; Sa-Nguanpanich, N. Reliability and Validity Study of the Thai Adaptation of the Copenhagen Burnout Inventory-Student Survey (CBI-SS) among Preclinical Medical Students at the Faculty of Medicine Siriraj Hospital, Mahidol University, Thailand. PLoS One 2021, 16, e0261887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wild, D.; Grove, A.; Martin, M.; Eremenco, S.; McElroy, S.; Verjee-Lorenz, A.; Erikson, P. Principles of Good Practice for the Translation and Cultural Adaptation Process for Patient-Reported Outcomes (PRO) Measures: Report of the Ispor Task Force for Translation and Cultural Adaptation. Value Health 2005, 8, 94–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Herdman, M.; Gudex, C.; Lloyd, A.; Janssen, M.; Kind, P.; Parkin, D.; Bonsel, G.; Badia, X. Development and Preliminary Testing of the New Five-Level Version of Eq-5d (Eq-5d-5l). Qual Life Res 2011, 20, 1727–1736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mai, V.Q.; Sun, S.; Minh, H.V.; Luo, N.; Giang, K.B.; Lindholm, L.; Sahlen, K.G. An Eq-5d-5l Value Set for Vietnam. Qual Life Res 2020, 29, 1923–1933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pattanaphesaj, J.; Thavorncharoensap, M.; Ramos-Goñi, J.M.; Tongsiri, S.; Ingsrisawang, L.; Teerawattananon, Y. The Eq-5d-5l Valuation Study in Thailand. Expert Rev Pharmacoecon Outcomes Res 2018, 18, 551–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kessler, R.C.; Barber, C.; Beck, A.; Berglund, P.; Cleary, P.D.; McKenas, D.; Pronk, N.; Simon, G.; Stang, P.; Ustun, T.B.; Wang, P. The World Health Organization Health and Work Performance Questionnaire (Hpq). J Occup Environ Med 2003, 45, 156–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hasselhorn, H.-M.; Muller, B.H.; Tackenberg, P. University of Wuppertal Next-Study Coordination. Next Scientific Report July 2005. Available online: http://www.econbiz.de/archiv1/2008/53602_nurses_work_europe.pdf (accessed on 19 March 2023).

- Aiken, L.H.; Clarke, S.P.; Sloane, D.M. Hospital Staffing, Organization, and Quality of Care: Cross-National Findings. Nurs Outlook 2002, 50, 187–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sasaki, N.; Obikane, E.; Vedanthan, R.; Imamura, K.; Cuijpers, P.; Shimazu, T.; Kamada, M.; Kawakami, N.; Nishi, D. Implementation Outcome Scales for Digital Mental Health (Iosdmh): Scale Development and Cross-Sectional Study. JMIR Form Res 2021, 5, e24332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carolan, S.; Harris, P.R.; Cavanagh, K. Improving Employee Well-Being and Effectiveness: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Web-Based Psychological Interventions Delivered in the Workplace. J Med Internet Res 2017, 19, e271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imamura, K.; Tran, T.T.T.; Nguyen, H.T.; Sasaki, N.; Kuribayashi, K.; Sakuraya, A.; Bui, T.M.; Nguyen, Q.T.; Nguyen, N.T.; Nguyen, G.T.H.; Zhang, M.W.; Minas, H.; Sekiya, Y.; Watanabe, K.; Tsutsumi, A.; Shimazu, A.; Kawakami, N. Effect of Smartphone-Based Stress Management Programs on Depression and Anxiety of Hospital Nurses in Vietnam: A Three-Arm Randomized Controlled Trial. Scientific Reports 2021, in press. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).