1. Introduction

A novel synthetic self-assembling peptide, PuraStat (3-D Matrix Ltd., Tokyo, Japan), has been introduced as a surgical or endoscopic hemostatic agent [

1,

2]. PuraStat is indicated for hemostasis of oozing bleeding in the parenchyma of solid organs, vascular anastomoses, and capillaries of the gastrointestinal tract [

2,

3,

4,

5]. The peptide molecule in PuraStat consists of a repeating sequence of three types of amino acids: Arginine, Alanine, and Aspartic Acid, and has a β-sheet structure [

3]. The peptide self-assembles into an extracellular scaffold matrix when activated by a pH change associated with exposure to the blood. The matrix sticks to and seals the blood vessels, thereby achieving hemostasis as a mechanical barrier. In addition, the activated matrix promotes tissue proliferation and facilitates effective mucosa healing [

2]. Therefore, excluding spurting bleeding, general cases of gastrointestinal bleeding are indicated for hemostasis with PuraStat.

Gastrointestinal bleeding is a medical emergency associated with elevated morbidity and mortality and significant costs to the healthcare system. However, there have been few studies on the efficacy of PuraStat for gastrointestinal bleeding during emergency endoscopic hemostasis. The aim of our study was to assess the safety, efficacy, and technical feasibility of PuraStat as a primary hemostat during emergency endoscopy. Herein, we report a case series of endoscopic haemostasis using PuraStat for gastrointestinal bleeding during an emergency endoscopy.

2. Case Description

This retrospective observational study was conducted at the Juntendo University Hospital in Tokyo, Japan. This study included all patients who underwent emergency endoscopic hemostasis using PuraStat for gastrointestinal bleeding between August 2021 and December 2022. Cases in which PuraStat was used during scheduled endoscopic procedures were excluded. Five experienced endoscopists performed all procedures. Patient clinical data, including age, sex, symptoms, underlying disease, use of antithrombotic drugs, necessity of blood transfusion, hemoglobin levels, refractoriness/intractability, causes of gastrointestinal bleeding, endoscopic procedure data, including location of the bleeding, types of bleeding, presence or absence of visible vessels, endoscopic hemostasis method, the clinical effectiveness of endoscopic hemostasis, and presence or absence of rebleeding were reviewed. In this study, rebleeding was defined as the development of fresh hematemesis or hematochezia, shock (defined as a systolic blood pressure of ≤ 90 mmHg or a pulse rate of ≥ 110 beats per minute) with melena after stabilization, or a drop in hemoglobin of more than 2g/dL within 24 hours. Refractory/intractable bleeding was defined as rebleeding requiring emergency endoscopic hemostasis after failing at least one treatment with endoscopic hemostatic therapy. Clinical effectiveness was defined as achieving no rebleeding within one week after the procedure. All patients were followed up for at least one month after the procedure.

The choice of the hemostasis method was left to the endoscopist. Endoscopic hemostasis using PuraStat was attempted in all cases. When a large amount of blood accumulated in the intestinal tract, it was washed thoroughly with water to identify the bleeding points. PuraStat was applied at the bleeding point using a delivery catheter inserted through the endoscope accessory channel. The procedure was completed after confirming that effective hemostasis was achieved after the wound was covered with a transparent jelly substance of PuraStat.

Twenty-five patients were recruited and treated with PuraStat. The clinical characteristics of the patients are summarized in

Table 1. The median age was 73.0 years (range, 40–91 years), and there were 20 men and five women. All but one patient had some underlying medical condition, including cancer, heart disease, diabetes, kidney disease, liver disease, or hypertension, and six were taking antithrombotic drugs. The median hemoglobin level immediately prior to the endoscopic procedure was 7.4 (range 5.0–14.5) g/dL, and 17 patients required red blood cell transfusions. Fifteen of the 25 patients had initial bleeding, while the remaining 10 patients had refractory or intractable bleeding in which at least one endoscopic hemostasis had been performed before this treatment and resulted in failure.

The endoscopic data of the study patients are summarized in

Table 2, and the case numbers in

Table 2 correspond to those in

Table 1.

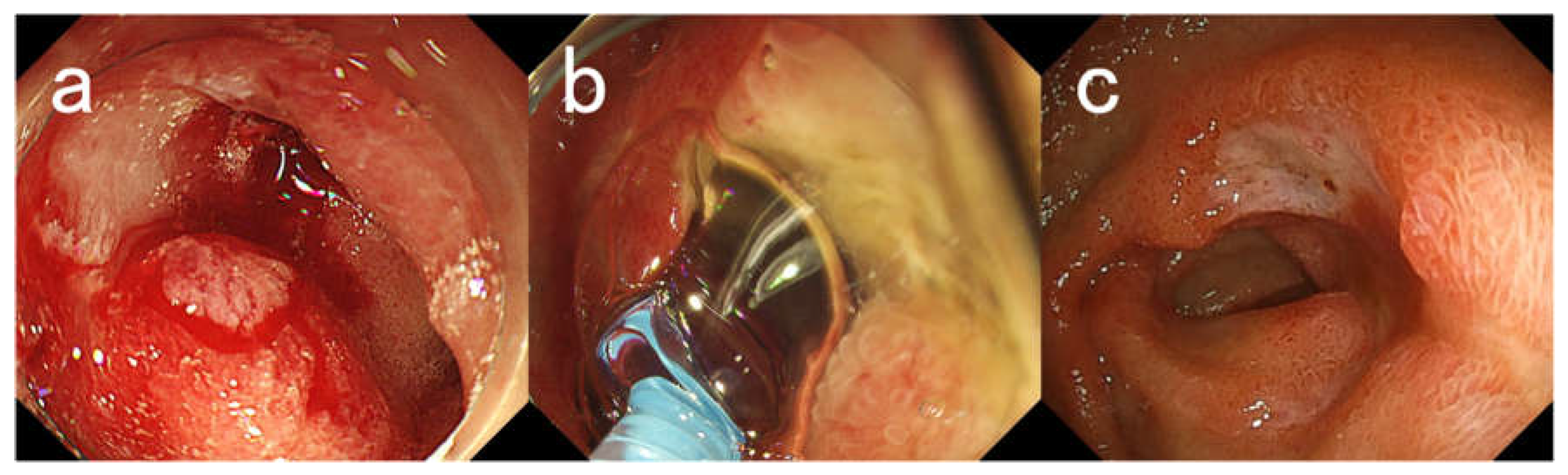

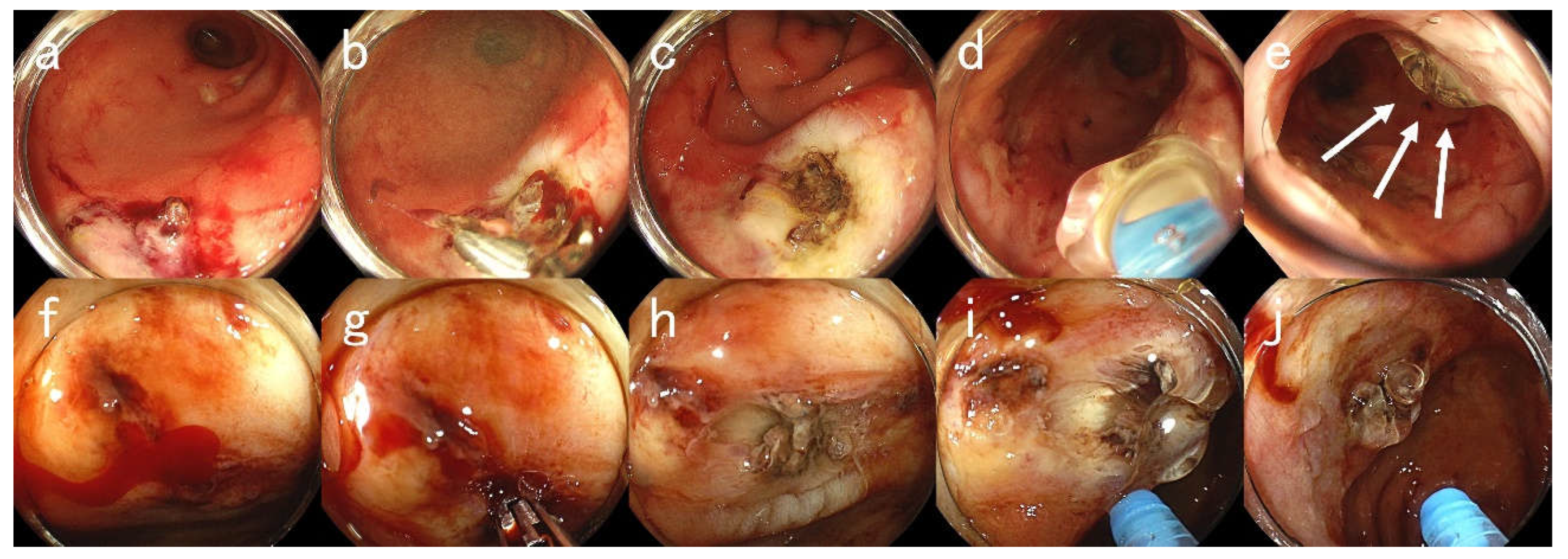

Figure 1 and

Figure 2 show endoscopic images in representative cases. The breakdown of bleeding was gastroduodenal ulcer or erosion, which was the most common type of bleeding; in 12 cases, bleeding after gastroduodenal or colorectal endoscopic resection was observed in 4 cases, acute hemorrhagic rectal ulcer in 2 cases, postoperative anastomotic ulcer in 2 cases, and gastric cancer, diffuse antral vascular ectasia, small intestinal ulcer, colonic diverticular bleeding, and radiation proctitis in each case. Bleeding occurs in various gastrointestinal tracts, including the stomach, duodenum, small intestine, colon, and rectum. The types of bleeding included oozing bleeding in 22 cases and spurting bleeding in three cases. Five cases had visible vessels. The method of hemostasis was only PuraStat application in six cases, and hemostasis in combination with high-frequency hemostatic forceps, hemostatic clip, argon plasma coagulation, and hemostatic agents (i.e., thrombin) in the remaining 19 cases. Rebleeding was observed in only three cases, one of which occurred 10 days after endoscopic hemostasis. Hemostasis was clinically effective in 23 cases (92%), including the aforementioned. All three rebleeding cases underwent endoscopic hemostasis using high-frequency hemostatic forceps and PuraStat and achieved complete hemostasis. No procedure-related side effects were observed in the studied cases.

Figure 1 and

Figure 2 show endoscopic images of hemostasis using PuraStat in representative cases.

Figure 1.

Endoscopic Images for Case #13. A 76-year-old woman with a history of myasthenia and diabetes mellitus presented with melena and underwent emergency endoscopy. (a) An ulcer with bleeding oozing in the duodenal bulb. (b) Application of PuraStat. Hemostasis was achieved by applying 3 mL of PuraStat. (c) Endoscopic image taken 2 weeks later. There was a reduction in the size of the ulcer and healing was observed. The patient has not presented with melena for 4 months after her last endoscopy.

Figure 1.

Endoscopic Images for Case #13. A 76-year-old woman with a history of myasthenia and diabetes mellitus presented with melena and underwent emergency endoscopy. (a) An ulcer with bleeding oozing in the duodenal bulb. (b) Application of PuraStat. Hemostasis was achieved by applying 3 mL of PuraStat. (c) Endoscopic image taken 2 weeks later. There was a reduction in the size of the ulcer and healing was observed. The patient has not presented with melena for 4 months after her last endoscopy.

Figure 2.

Endoscopic Images for Case #23. A 80-year-old man with a history of diabetes, chronic kidney disease (on hemodialysis), foot gangrene, and hypertension presented with hematochezia. The patient was taking an aspirin. (a)–(e) First emergency endoscopic views. (a) Ulcers with visible blood vessels in the rectum. (b) High-frequency hemostasis using hemostatic forceps. (c) An ulcer after coagulation. (d) Application of PuraStat. (e) An ulcer attached with PuraStat (arrows). However, 10 days later, massive hematochezia recurred. (f)–(j) Second emergency endoscopy at rebleeding. (f) An ulcer with active oozing bleeding in the rectum. (g) Re-hemostasis using hemostatic forceps. (h) An ulcer after coagulation. (i) Application of PuraStat. (j) An ulcer attached with PuraStat. Hemostasis was achieved by applying 3 mL of PuraStat. It has been a month since the last endoscopy and the patient has yet to present with hematochezia for one month.

Figure 2.

Endoscopic Images for Case #23. A 80-year-old man with a history of diabetes, chronic kidney disease (on hemodialysis), foot gangrene, and hypertension presented with hematochezia. The patient was taking an aspirin. (a)–(e) First emergency endoscopic views. (a) Ulcers with visible blood vessels in the rectum. (b) High-frequency hemostasis using hemostatic forceps. (c) An ulcer after coagulation. (d) Application of PuraStat. (e) An ulcer attached with PuraStat (arrows). However, 10 days later, massive hematochezia recurred. (f)–(j) Second emergency endoscopy at rebleeding. (f) An ulcer with active oozing bleeding in the rectum. (g) Re-hemostasis using hemostatic forceps. (h) An ulcer after coagulation. (i) Application of PuraStat. (j) An ulcer attached with PuraStat. Hemostasis was achieved by applying 3 mL of PuraStat. It has been a month since the last endoscopy and the patient has yet to present with hematochezia for one month.

3. Discussion

Endoscopic procedures, surgery, and radiological angiography are the main therapeutic options available for managing gastrointestinal bleeding. Owing to the increasing number of successful endoscopic applications and recent advances in technology, endoscopic procedures are the current standard for hemostasis in patients with gastrointestinal bleeding. In this study, we used PuraStat to treat various gastrointestinal bleeding episodes. The high clinical hemostatic effectiveness of PuraStat was confirmed in patients with underlying disease and/or bleeding diathesis who were taking antithrombotic drugs. It is interesting that hemostatic effectiveness was found in 23 out of 25 cases (92%), including 10 cases of refractory or intractable gastrointestinal bleeding. Rebleeding was observed in three cases, while hemostasis was achieved in all cases by endoscopic treatment using PuraStat. In general, the rebleeding rate in patients with peptic ulcer is expected to be 10–20% and is thought to be 2–3 times higher in patients taking antithrombotic drugs [

6]. In addition, the previous report on acute gastrointestinal bleeding has also shown that rebleeding were significantly associated with patient comorbidities (i.e., cancer, heart disease, diabetes, kidney disease, liver disease, or hypertension) with an odds ratio of 1.2 (95% confidence interval, 1.0–1.4) [

7]. The rebleeding rate in this study was lower than what was estimated, although it could not be compared to that rate. Therefore, endoscopic treatment using PuraStat is expected to have a high hemostatic efficiency.

Hemostasis with endoscopic clipping or high-frequency hemostatic forceps has been increasingly adopted as a method for hemostasis of the bleeding vessel at the ulcer base. Conventional hemostatic clips achieve hemostasis over the bleeding vessel at the ulcer base through the application of mechanical force between the two jaws. However, secure application of hemoclips to the fibrotic ulcer base can be technically difficult at times [

8]. Furthermore, high-frequency hemostatic forceps are endoscopic coagulation devices developed solely for hemostasis. Unlike biopsy forceps, it has a narrow opening angle, small cup, and dull edge to enable pinpoint holding of the target lesion. However, high-frequency coagulation may cause serious complications such as perforation due to tissue damage during or after the procedure [

9]. In contrast, hemostasis using PuraStat involves only applying PuraStat from a dedicated catheter, which is extremely simple. In addition, applying PuraStat does not cause tissue damage due to thermocoagulation; therefore, there is no risk of perforation associated with the procedure. Therefore, hemostasis with PuraStat is a simple and safe procedure. The application of PuraStat can be an option for hemostasis of gastrointestinal bleeding during an emergency endoscopy.

Furthermore, endoscopic hemostasis can be challenging in some scenarios, even for the most experienced endoscopists. The presence of hematic residues and clots in the gastrointestinal tract can pose technical difficulties that may prolong the procedure time or make it impossible [

10]. One of the characteristics of PuraStat is that it is a transparent jelly like substance prone to immiscibility with the blood. Therefore, it is possible to secure a visual field after the application, suggesting that it is easy to identify the bleeding point and confirm hemostasis.

The limitations of the present study include that it was carried out at a single centre and the number of cases was small. Furthermore, PuraStat was not originally indicated for spurting bleeding, although in the present analysis, hemostasis could be achieved by applying PuraStat after weakening the bleeding pressure with hemostatic clips or hemostatic forceps, even in three spurting bleeding cases. These findings suggest that hemostatic efficiency could be enhanced by the combination of PuraStat and other hemostatic methods. However, further investigation is needed to validate our results and to confirm their clinical effectiveness.

4. Conclusions

In this case series, a self-assembling peptide hemostatic hydrogel, PuraStat, was effective in achieving hemostasis of gastrointestinal bleeding during emergency endoscopy. The use of PuraStat should be considered in emergency endoscopic hemostasis of gastrointestinal bleeding.

Author Contributions

T.M. mainly contributed to this work and wrote the manuscript. E.K., K.H., Y.A., H.U., T.S., M.H., and A.N. contributed equally to this work. All authors have read and approved the final version of this manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Institutional Review Board and the Ethical Committee of Juntendo University Hospital (reference number: #E22-0454).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets of the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Yoshida, M.; Goto, N.; Kawaguchi, M.; Koyama, H.; Kuroda, J.; Kitahora, T.; Iwasaki, H.; Suzuki, S.; Kataoka, M.; Takashi, F.; Kitajima, M. Initial clinical trial of a novel hemostat, TDM-621, in the endoscopic treatments of the gastric tumors. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2014, 29 (Suppl. 4), 77–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Uraoka, T.; Ochiai, Y.; Fujimoto, A.; Goto, O.; Kawahara, Y.; Kobayashi, N.; Kanai, T.; Matsuda, S.; Kitagawa, Y.; Yahagi, N. A novel fully synthetic and self-assembled peptide solution for endoscopic submucosal dissection-induced ulcer in the stomach. Gastrointest. Endosc. 2016, 83, 1259–1264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, MF.; Ma, Z.; Ananda, A. A novel haemostatic agent based on self-assembling peptides in the setting of nasal endoscopic surgery, a case series. Int. J. Surg. Case. Rep. 2017, 41, 461–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giritharan, S.; Salhiyyah, K.; Tsang, G.M.; Ohri, S.K. Feasibility of a novel, synthetic, self-assembling peptide for suture-line haemostasis in cardiac surgery. J. Cardiothorac. Surg. 2018, 13, 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Nucci, G.; Reati, R.; Arena, I.; Bezzio, C.; Devani, M.; Corte, C.D.; Morganti, D.; Mandelli, E.D.; Omazzi, B.; Redaelli, D.; Saibeni, S.; Dinelli, M.; Manes, G. Efficacy of a novel self-assembling peptide hemostatic gel as rescue therapy for refractory acute gastrointestinal bleeding. Endoscopy. 2020, 52, 773–779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gralnek, I.M.; Stanley, A.J.; Morris, A.J.; Camus, M.; Lau, J.; Lanas, A.; Laursen, S.B.; Radaelli, F.; Papanikolaou, I.S.; Cúrdia Gonçalves, T.; Dinis-Ribeiro, M.; Awadie, H.; Braun, G.; de Groot, N.; Udd, M.; Sanchez-Yague, A.; Neeman, Z.; van Hooft, J.E. Endoscopic diagnosis and management of nonvariceal upper gastrointestinal hemorrhage (NVUGIH): European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ESGE) Guideline - Update 2021. Endoscopy. 2021, 53, 300–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nagata, N.; Sakurai, T.; Moriyasu, S.; Shimbo, T.; Okubo, H.; Watanabe, K.; Yokoi, C.; Yanase, M.; Akiyama, J.; Uemura, N. Impact of INR monitoring, reversal agent use, heparin bridging, and anticoagulant interruption on rebleeding and thromboembolism in acute gastrointestinal bleeding. PLoS. One. 2017, 12, e0183423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grupka, M.J.; Benson, J. Endoscopic clipping. J. Dig. Dis. 2008, 9, 72–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ninomiya, S.; Shiroshita, H.; Bandoh, T.; Soma, W.; Abe, H.; Arita, T. Delayed perforation 10 days after endoscopic hemostasis using hemostatic forceps for a bleeding Dieulafoy lesion. Endoscopy. 2013, 45, Supplement 2 UCTN: E99-100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.I.; Kim, S.S.; Park, S.; Han, J.; Kim, J.K.; Han, S.W.; Choi, K.Y.; Chung, I.S.; Chung, K.W.; Sun, H.S. Endoscopic hemoclipping using a transparent cap in technically difficult cases. Endoscopy. 2003, 35, 659–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).