Submitted:

26 March 2023

Posted:

28 March 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

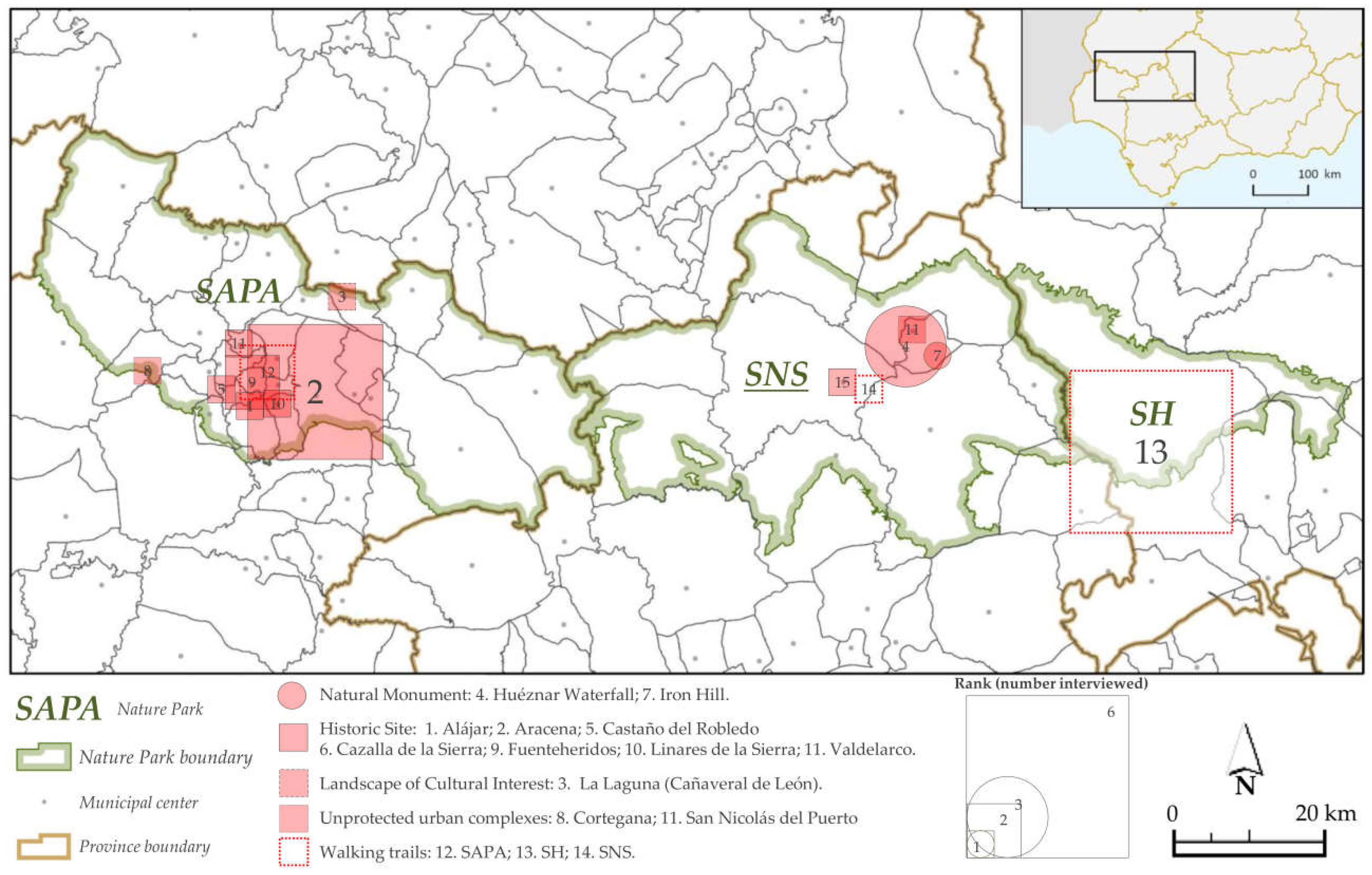

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data and Methods

2.2. Case Study

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. The Environmental Dimension of Local Development

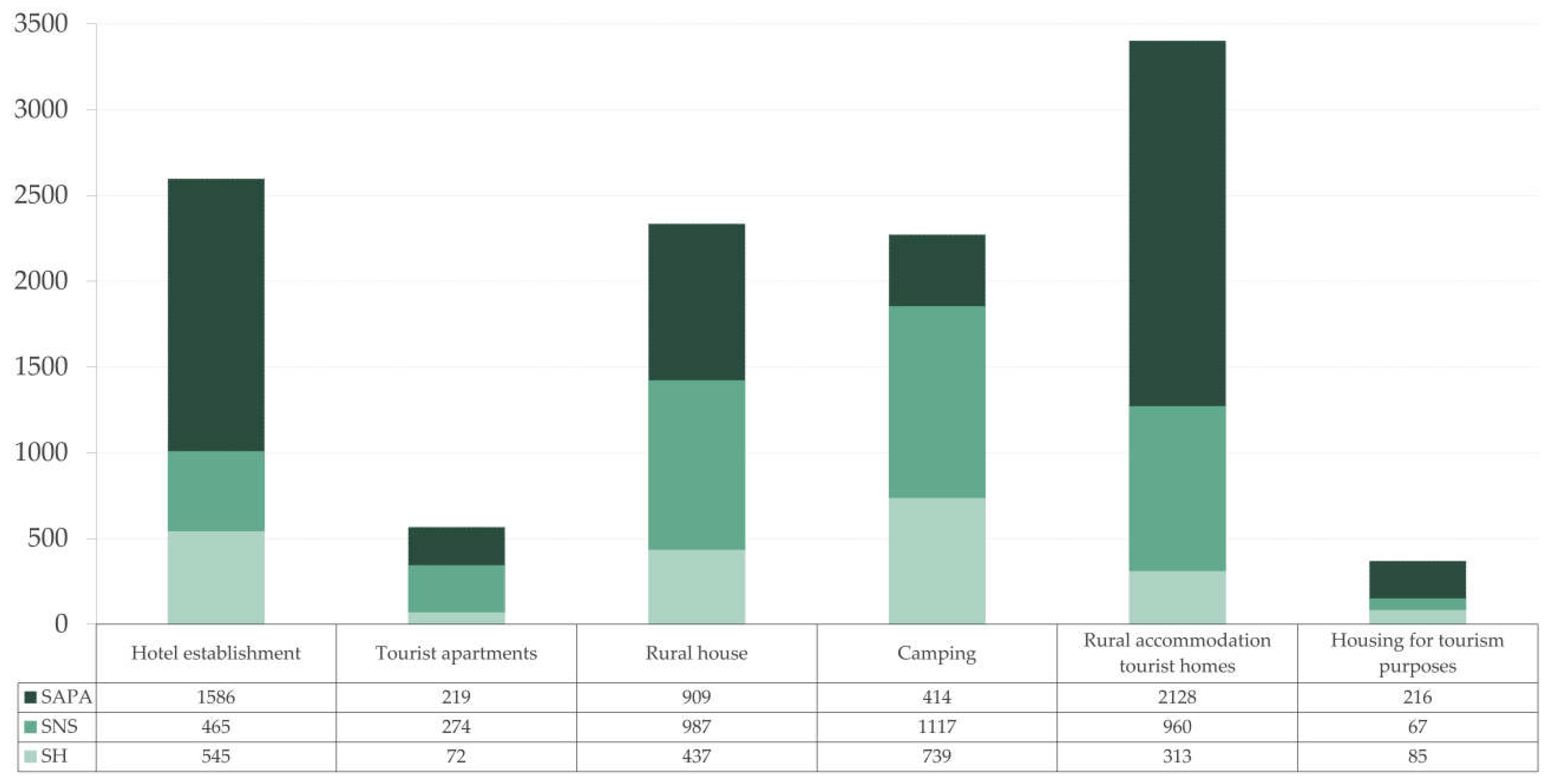

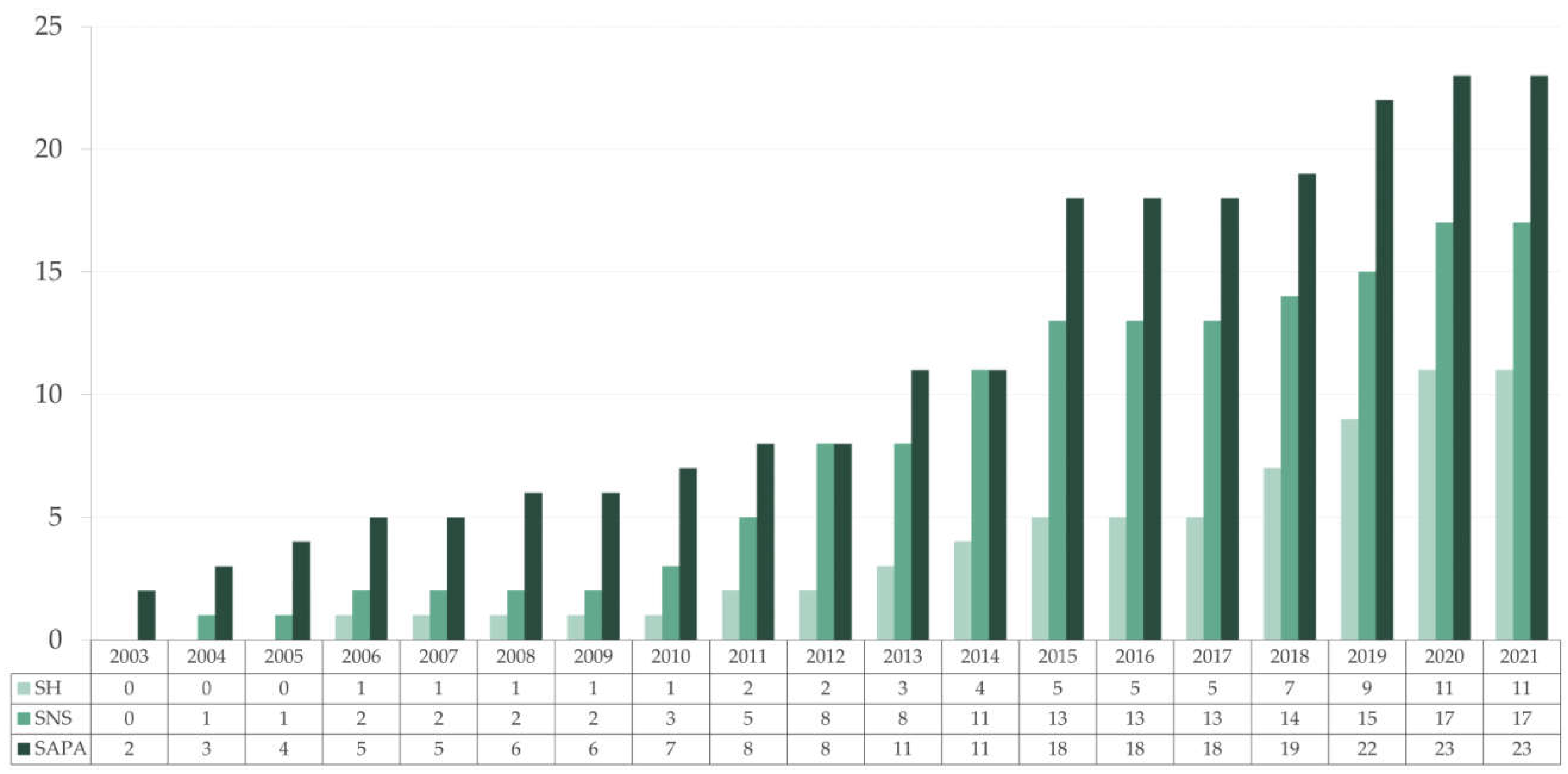

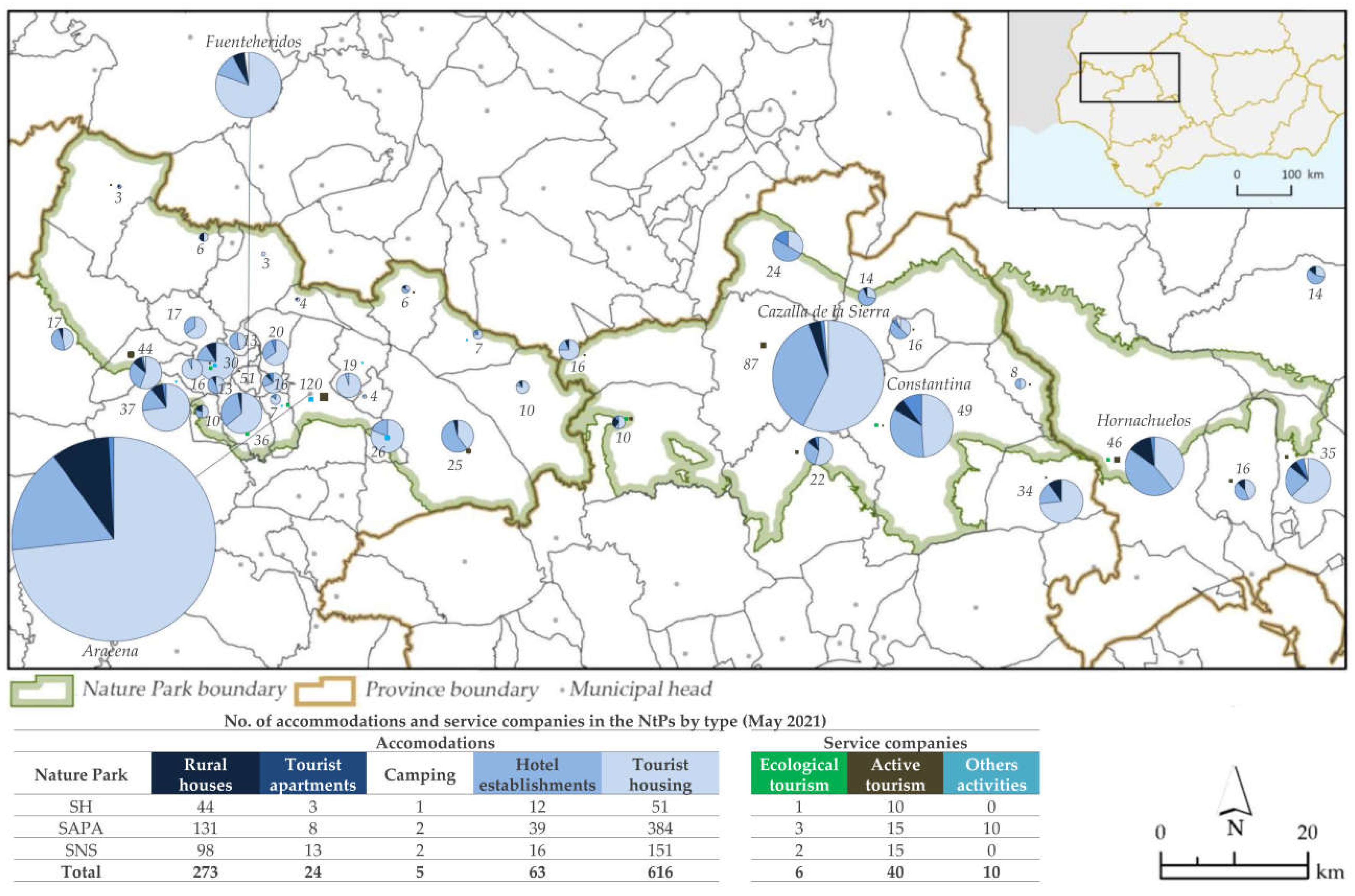

3.2. The Economic Dimension of Local Development

3.3. The Sociocultural Dimension of Local Development

- Tourism contributes to fixing the population (Int18, Int35), slows depopulation, and increases opportunities for women and young people (Int04, Int19). It appears among all the stakeholders and in the three NtPs. Still, the municipal stakeholders are the most optimistic, especially in the municipalities that concentrate on tourist attractions and offers (Int18) and are better connected (Int23).

- Tourism has a limited effect on demography and does not contribute to the fight against depopulation (Int01, Int05, Int21, Int33) since the increase in the population (fixation and attraction) depends on SIEs (technological and communication), as seen during the pandemic (Int01, Int21, Int29). Some recognise that tourism is an opportunity (Int39).

- Tourism does not stop depopulation (Int02), and emigration is the cause of depopulation (Int06). It is a vision of peripheral municipal stakeholders with little tourist offer.

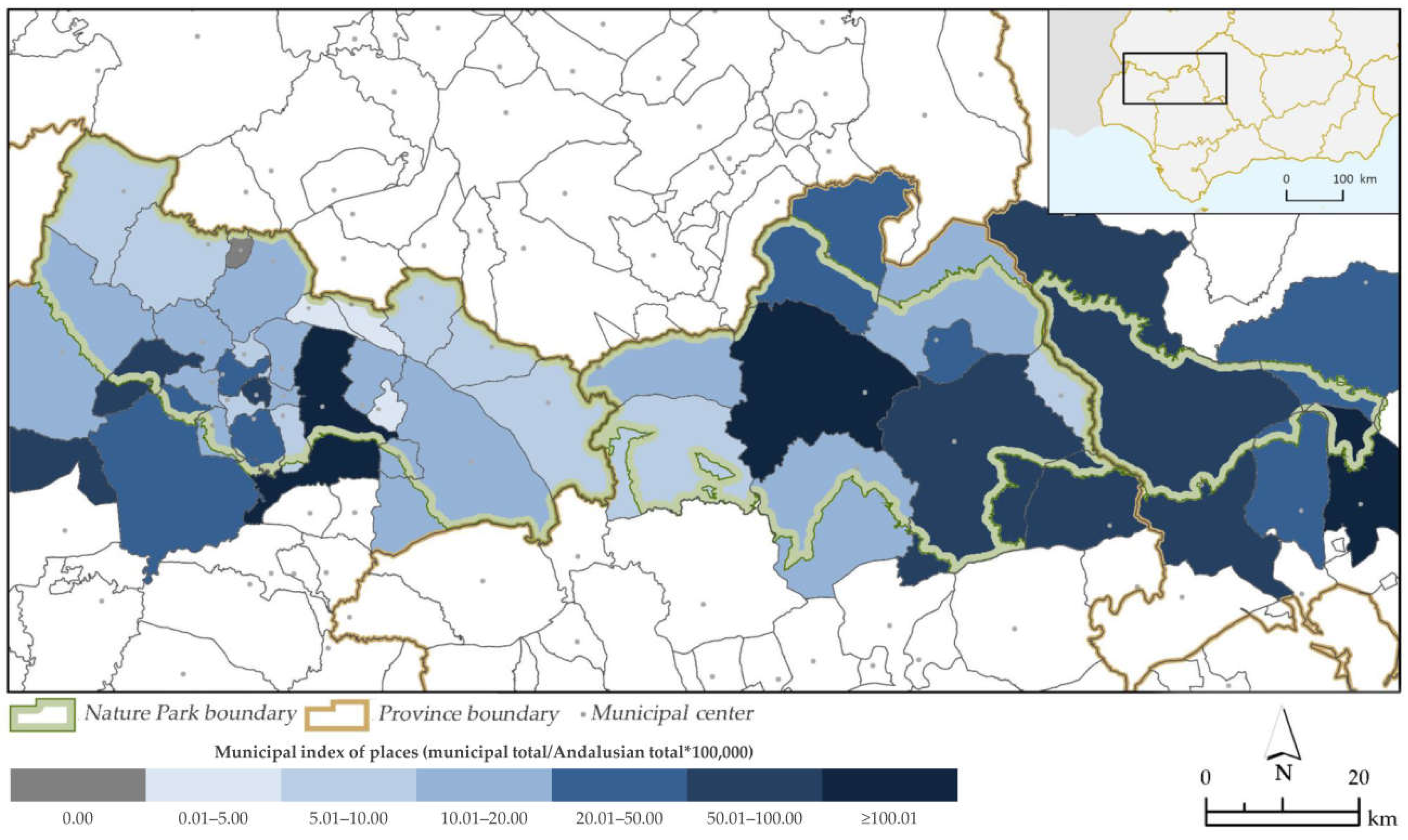

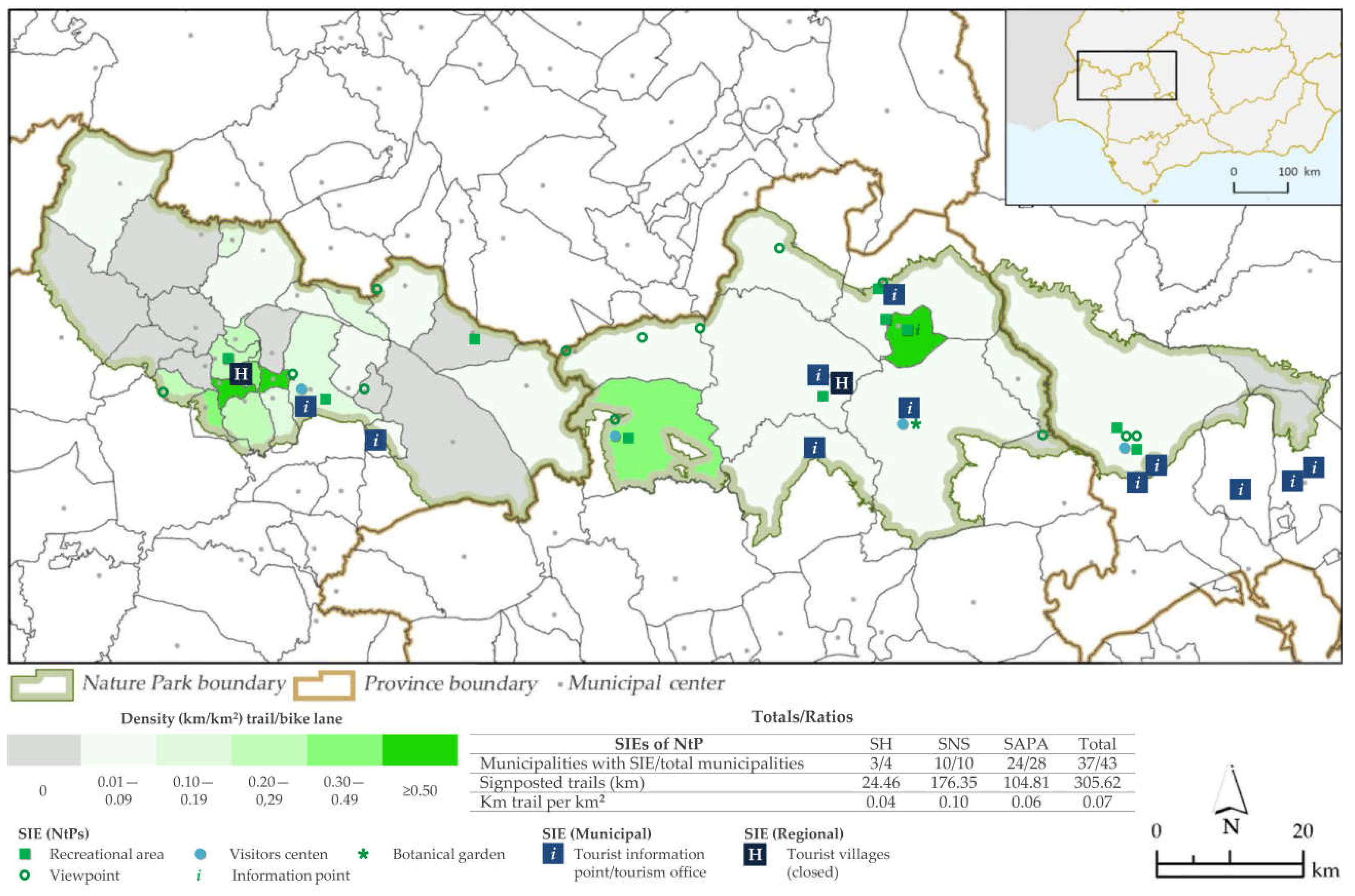

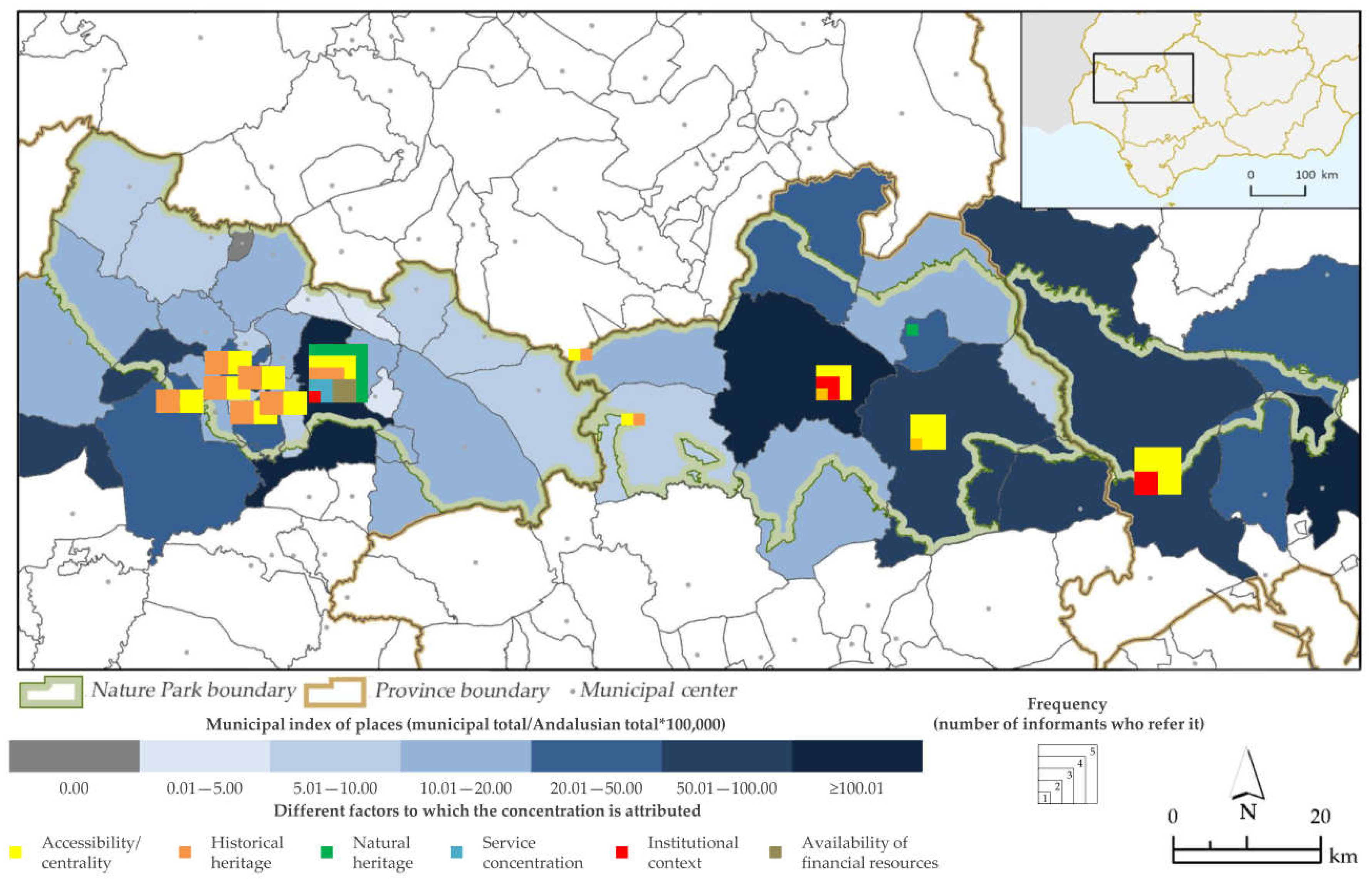

3.4. The Territorial Dimension of Local Development

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgements

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| DSMBR | Dehesas de Sierra Morena Biosphere Reserve |

| Int | Interviews |

| LAGs | Local Action Groups |

| NtP | Nature Park |

| PNA | Protected Nature Areas |

| SAPA | Nature Park Sierra de Aracena y Picos de Aroche |

| SH | Nature Park Sierra de Hornachuelos |

| SIEs | Services, infrastructures and [types of] equipment |

| SNS | Nature Park Sierra Norte de Sevilla |

| UWGpSNS | UNESCO World Geopark Sierra Norte de Sevilla |

| 1 | Among the types of accommodation established by Andalusian legislation are “rural accommodation tourist housing” (VTAR) [105] and “housing for tourism purposes” (VFT) [135]. Both types with some differences between them represent accommodation without services, e.g. food, daily cleaning, or laundry. They are not legally considered business activities, but income from real estate capital. In practice they are not subject to fixed costs and only declare taxes according to their turnover. |

References

- Collantes, F.; Pinilla, V. ¿Lugares que no importan? La despoblación de la España rural desde 1900 hasta el presente; Publicaciones de la Universidad de Zaragoza: Zaragoza, Spain, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Figueiredo, E. Imagine there’s no rural: The transformation of rural spaces into places of nature conservation in Portugal. Eur. Urban Reg. Stud. 2008, 15, 159–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaccaro, I.; Beltran, O. Consuming space, nature and culture: Patrimonial discussions in the hyper-modern era. Tour. Geogr. 2007, 9, 254–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saxena, G.; Clark, G.; Oliver, T.; Ilbery, B. Conceptualizing integrated rural tourism. Tour. Geogr. 2007, 9, 347–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greffe, X. Is rural tourism a lever for economic and social development? J. Sustain. Tour. 1994, 2, 22–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinto-Correia, T.; Breman, B. Understanding marginalization in the periphery of Europe: A multidimensional process. In Sustainable Land Management; Brouwer, F., Van Rheenen, T., Dhillion, S.S., Elgersma, A.M., Eds.; Edward Elgar: Cheltenham, UK, 2008; pp. 11–40. [Google Scholar]

- Ramsey, D.; Malcolm, C.D. The importance of location and scale in rural and small town tourism product development: The case of the Canadian Fossil Discovery Centre, Manitoba, Canada. Can. Geogr.-Geogr. Can. 2017, 62, 250–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pezzi, M.G.; Faggian, A.; Reid, N. Local entrepreneurship and tourism development in peripheral areas between policies and practices. Reg. Sci. Policy Pract. 2019, 11, 445–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, G. Multifunctional quality and rural community resilience. Trans. Inst. Br. Geogr. 2010, 35, 364–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knickel, K.; Renting, H.; van-der-Ploeg, J. Multifunctionality in European agriculture. In Sustaining Agriculture and the Rural Economy; Brouwer, F., Ed.; Edward Elgar Publishing Inc.: Cheltenham, UK, 2004; pp. 81–103. [Google Scholar]

- Buttel, F.H.; Flinn, W.L. Conceptions of Rural Life and Environmental Concern. Rural Sociol. 1977, 42, 544–55. [Google Scholar]

- EC. The future of rural society; Office for Official Publications of the European Communities: Luxembourg, Luxembourg, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Gómez-Moreno, M.L.; Rubio-Barquero, L.M. Tourism, Development and Protected Areas: Deconstructing the Myth. Europ. Countrys. 2020, 12, 568–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aparicio-Sánchez, M.S. El Reto del turismo en los Espacios Naturales Protegidos españoles: la integración entre conservación, calidad y satisfacción. Ph.D. Thesis, Universidad Complutense de Madrid, Madrid, Spain, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Woodhouse, E.; Bedelian, C.; Dawson, N.; Barnes, P. Social impacts of protected areas: Exploring evidence of trade-offs and synergies. In Ecosystem Services and Poverty Alleviation: Trade-Offs and Governance; Schreckenberg, K., Poudyal, M., Mace, G., Eds.; Routledge: Oxon, UK, 2018; pp. 222–240. [Google Scholar]

- Atauri-Mezquida, J.A.; Muñoz-Santos, M.; Múgica-de-la-Guerra, M. Protected Areas in the Face of Global Change Climate Change Adaptation in Planning and Management; EUROPARC-Spain: Madrid, Spain, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Chamboredon, J.C. La ‘Naturalisation’ de la Campagne: une Autre Manière de Cultiver les Simples? In Protection de la Nature: Histoire et Idéologie – De la Nature à l’Environnement; Cadoret, A., Ed.; L’Harmattan: Paris, France, 1985; pp. 138–151. [Google Scholar]

- Marsden, T.; Murdoch, J.; Lowe, P.; Flynn, A. Constructing the Countryside; UCL Press: London, UK, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Vázquez-Varela, C.; Martín-Gil, F. Problemas de sostenibilidad del turismo rural en España. An. Geogr. Univ. Complut. 2011, 31, 171–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adamowicz, J. Towards synergy between tourism and nature conservation. The challenge for the rural regions: The case of Drawskie Lake District, Poland. Europ. Countrys. 2010, 2, 118–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garzón-García, R.; Ramírez-López, M.L. Las áreas protegidas como territorios turísticos: Análisis crítico a partir del caso de los parques naturales de la Sierra Morena andaluza. Cuad. Tur. 2018, 41, 249–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz-Ballesteros, E. Consumir y consumar naturaleza. Prácticas turísticas en la naturalización de la Sierra de Aracena. Trab. Antropol. Etnol. 2018, 58, 1–17. [Google Scholar]

- Pulido-Fernández, J.I. Gestión turística activa y desarrollo económico en los parques naturales andaluces. Una propuesta de revisión desde el análisis del posicionamiento de sus actuales gestores. RER 2008, 81, 171–203. [Google Scholar]

- Zawilińska, B. Residents’ attitudes towards a national park under conditions of suburbanisation and tourism pressure: A case study of Ojcow National Park (Poland). Europ. Countrys. 2020, 12, 119–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Troitiño-Vinuesa, M.A. Espacios naturales protegidos y desarrollo rural: Una relación territorial. B. Asoc. Geogr. Esp. 1995, 20, 23–37. [Google Scholar]

- Araque-Jiménez, E.; Crespo-Guerrero, J.M. Conservation versus développement? Une nouvelle situation conflictuelle dans les parcs naturels andalous. Collect. EDYTEM. Cah. de Géographie 2010, 10, 113–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anton-Clavé, S.; Blay-Boqué, J.; Salvat-Salvat, J. Turismo, actividades recreativas y uso público en los parques naturales. Propuesta para la conservación de los valores ambientales y el desarrollo productivo local. B. Asoc. Geogr. Esp. 2008, 48, 5–38. [Google Scholar]

- De-Uña-Álvarez, E.; Villarino-Pérez, M. Territorio, turismo y desarrollo en la dimensión local. In Geografía, territorio y paisaje. El estado de la cuestión, Actas del XXI Congreso de Geógrafos Españoles, Ciudad Real, 27–29 de octubre de 2009; Universidad de Castilla-La Mancha: Ciudad Real, Spain, 2009; pp. 207–221. [Google Scholar]

- Cànoves-i-Valiente, G.; Villarino-Pérez, M.V.; Blanco-Romero, M.A.; de-Uña-Álvarez, E.; Espejo-Marín, C. Turismo de interior: renovarse o morir: Estrategias y productos en Catalunya, Galicia y Murcia; Universitat de València: València, Spain, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Nieto-Masot, A.; Ríos-Rodríguez, N. Rural Tourism as a Development Strategy in Low-Density Areas: Case Study in Northern Extremadura (Spain). Sustainability 2021, 13, 239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marzo-Navarro, M.; Pedraja-Iglesias, M.; Vinzón, L. Sustainability indicators of rural tourism from the perspective of the residents. Tour Geogr. 2015, 17, 586–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahamonde-Rodríguez, M.; García-Delgado, F.J.; Šadeikaitė, G. Sustainability and Tourist Activities in Protected Natural Areas: The Case of Three Natural Parks of Andalusia (Spain). Land 2022, 11, 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivona, A. Economic effects of rural tourism. Farm, food-and-wine and enhancement of cultural routes. In The European Pilgrimage Routes for Promoting Sustainable and Quality Tourism in Rural Areas; Bambi, G., Barbari, M., Eds.; University Press: Florence, Italy, 2015; pp. 779–791. [Google Scholar]

- Flather, C.H.; Cordell, H.K. Outdoor recreation: Historical and anticipated trends. In Wildlife and Recreationists. Coexistence through Management and Research; Knight, R.L., Gutzwiller, K.J., Eds.; Island Press: Washington, DC, USA, 1995; pp. 3–16. [Google Scholar]

- Cànoves-i-Valiente, G.; Villarino-Pérez, M. Turismo en espacio rural en España: actrices e imaginario colectivo. D.A.C. 2000, 37, 51–77. [Google Scholar]

- Arnegger, J.; Woltering, M.; Job, H. Toward a product-based typology for nature-based tourism: A conceptual framework. J. Sustain. Tour. 2010, 18, 915–928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hardy, A. Understanding self drive tourism. Rubber tire traffic: A case study of Bella Cool, British Columbia. In Informed Leisure Practice: Cases as Conduits between Theory and Practice; Vaugenois, N.L., Ed.; Malaspina University-College: Nanaimo, BC, Canada, 2006; Volume 2, pp. 46–51. [Google Scholar]

- Simoncini, R.; De-Groot, R.; Pinto-Correia, T. An integrated approach to assess options for multi-functional use of rural areas: Special issue “Regional Environmental Change”. Reg. Environ. Change 2009, 9, 139–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cànoves-i-Valiente, G.; Villarino-Pérez, M.; Herrera-Jiménez, L. Políticas públicas, turismo rural y sostenibilidad: Difícil equilibrio. B. Asoc. Geogr. Esp. 2006, 41, 199–217. [Google Scholar]

- García-Delgado, F.J.; Martínez-Puche, A.; Lois-González, R.C. Heritage, Tourism and Local Development in Peripheral Rural Spaces: Mértola (Baixo Alentejo, Portugal). Sustainability 2020, 12, 9157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prideaux, B. Building visitor attractions in peripheral areas-Can uniqueness overcome isolation to produce viability? Int. J. Tour. Res. 2002, 4, 379–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holden, A. Exploring stakeholders’ perceptions of sustainable tourism development in the Annapurna conservation area: Issues and challenges. Tour. Plan. Dev. 2010, 7, 337–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ray, C. Towards a meta-framework of endogenous development: repertoires, paths, democracy and rights. Sociologia Ruralis 1999, 39, 521–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Courtney, P.; Hill, G.; Roberts, D. The role of natural heritage in rural development: An analysis of economic linkages in Scotland. J. Rural Stud. 2006, 22, 469–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravazzoli, E.; Valero-López, D.E. Social Innovation: An Instrument to Achieve the Sustainable Development of Communities. In Sustainable Cities and Communities. Encyclopedia of the UN Sustainable Development Goals; Leal Filho, W., Azul, A., Brandli, L., Özuyar, P., Wall, T., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Engelmo-Moriche, A.; Nieto-Masot, A.; Mora-Aliseda, J. Territorial Analysis of the Survival of European Aid to Rural Tourism (Leader Method in SW Spain). Land 2021, 10, 1030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belliggiano, A.; Cejudo-García, E.; Labianca, M.; Navarro-Valverde, F.; De-Rubertis, S. The “Eco-Effectiveness” of Agritourism Dynamics in Italy and Spain: A Tool for Evaluating Regional Sustainability. Sustainability 2020, 12, 7080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bock, B.B. Rural marginalisation and the role of social innovation; a turn towards nexogenous development and rural reconnection. Sociologia Ruralis 2016, 56, 552–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bohlin, M.; Brandt, D.; Elbe, J. Tourism as a vehicle for regional development in peripheral areas–myth or reality? A longitudinal case study of Swedish regions. Eur. Plan. Stud. 2016, 24, 1788–1805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andraz, J.M.; Norte, N.M.; Gonçalves, H.S. Effects of tourism on regional asymmetries: Empirical evidence for Portugal. Tour. Manag. 2015, 50, 257–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McAreavey, R.; McDonagh, J. Sustainable rural tourism: Lessons for rural development. Sociol. Rural. 2011, 51, 175–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bull, B. Encouraging tourism development through the EU structural funds: a case study of the implementation of EU programmes on Bornholm. Int. J. Tour. Res. 1999, 1, 149–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dinis, I.; Simões, O.; Cruz, C.; Teodoro, A. Understanding the impact of intentions in the adoption of local development practices by rural tourism hosts in Portugal. J. Rural Stud. 2019, 72, 92–103. [Google Scholar]

- Hohl, A.E.; Tisdell, C.A. Peripheral tourism: Development and management. Ann. Tour. Res. 1995, 22, 517–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharpley, R. Rural tourism and the challenge of tourism diversification: The case of Cyprus. Tour. Manag. 2002, 23, 233–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brouder, P. Creative outposts: Tourism’s place in rural innovation. Tour. Plan. Dev. 2012, 9, 383–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, M.D.; Krannich, R.S. Tourism dependence and resident attitudes. Ann. Tour. Res. 1998, 25, 783–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharpley, R.; Telfer, D.J. (Eds.) Tourism and development: concepts and issues; Channel View Publications: Clevedon, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Henke, R.; Salvioni, C. La multifunzionalità in agricoltura: Dal post-produttivismo all’azienda rurale. In Agricoltura Multifunzionale; Aguglia, L., Henke, R., Salvioni, C., Eds.; ESI: Napoli, Italy, 2008; pp. 15–29. [Google Scholar]

- Saxena, G.; Ilbery, B. Developing integrated rural tourism: Actor practices in the English/Welsh border. J. Rural Stud. 2010, 26, 260–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yubero-Bernabé, C.; García-Hernández, M. El turismo en el medio rural en España desde el enfoque de la transferencia de políticas públicas. B. Asoc. Geogr. Esp. 2019, 81, 1–34. [Google Scholar]

- Cànoves-i-Valiente, G.; Villarino-Pérez, M.; Armas-Diéguez, P.; Seguí-Llinàs, M.; Priestley, G.K.; Blanco-Romero, A.; Cuesta-Fernández, L.; Herrera-Jiménez, L. Turismo rural y desarrollo rural: perspectivas y futuro en Cataluña, Baleares y Galicia. Serie Geográfica 2003, 11, 117–140. [Google Scholar]

- Tisdell, C. A review of tourism economics with some observations on tourism in India. In Proceedings of the 4th IIDS International Seminar on Tourism and Economic Development, Orissa, India, 4–7 June 1997; Nova Science Publishers: Hauppauge, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Ribeiro, M.; Marques, C. Rural tourism and the development of less favoured areas—between rhetoric and practice. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2002, 4, 211–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Delgado, F.J. Los impactos del turismo en la gestión de destinos. In Manual de Gestión de Destinos Turísticos; Flores-Ruiz, D., Coord.; Tirant: Valencia, Spain, 2014; pp. 155–180. [Google Scholar]

- Schmallegger, D.; Carson, D. Is tourism just another staple? A new perspective on tourism in remote regions. Curr. Issues Tour. 2010, 13, 201–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cànoves-i-Valiente, G.; Herrera-Jiménez, L.; Blanco-Romero, A. Turismo rural en España: un análisis de la evolución en el contexto europeo. Cuadernos de Geografía (Universidad de Valencia) 2005, 77, 41–58. [Google Scholar]

- Koster, R.; Baccar, K. Rural First Nations tourism: Examining the relationship between sustainable tourism and capacity. Sustainability planning and collaboration in rural Canada: Taking the next steps; Hallström, L.K., Beckie, M.A., Hvenegaard, G.T., Mündel, K., Eds.; The University of Alberta Press: Edmonton, Canada, 2016; pp. 217–239. [Google Scholar]

- Bramwell, B. Rural tourism and sustainable rural tourism. J. Sustain. Tour. 1994, 2, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murdoch, J.; Marsden, T. The spatialization of politics: local and national actor-spaces in environmental conflict. Trans. Inst. Br. Geogr. 1995, 368–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharpley, R. Tourism and sustainable development: Exploring the theoretical divide. J. Sustain. Tour. 2000, 8, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saxena, G.; Ilbery, B. Integrated rural tourism a border case study. Ann. Tour. Res. 2008, 35, 233–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butler, R.W.; Hall, C.M.; Jenkins, J. (Eds.) Tourism and Recreation in Rural Areas. John Wiley: Chichester, UK, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Koster, R. A regional approach to rural tourism development: Towards a conceptual framework for communities in transition. Society and Leisure 2007, 30, 133–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahamonde-Rodríguez, M.; Šadeikaitė, G.; Pizarro-Gómez, A.; Márquez-Domínguez, J.A.; García-Delgado, F.J. Las rutas turísticas como instrumentos de desarrollo local. Análisis de caso de la «Ruta del Jabugo» (Andalucía, España). In Leyendo el territorio. Homenaje a Miguel Ángel Troitiño; Martínez-Cárdenas, R., Cabrales-Barajas, L.F., de-la-Calle-Vaquero, M., García-Hernández, M., Mínguez-García, M.C., Troitiño-Torralba, L., Coords.; Centro Universitario de Los Altos, de la Universidad de Guadalajara: Guadalajara, México, 2022; pp. 611–624. [Google Scholar]

- Butowski, L. Tourist sustainability of destination as a measure of its development. Curr. Issues Tour. 2017, 22, 1043–1061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renfors, S.M. Stakeholders’ Perceptions of Sustainable Tourism Development in a Cold-Water Destination: The Case of the Finnish Archipelago. Tour. Plan. Dev. 2020, 18, 510–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Twining-Ward, L.; Butler, R.W. Implementing STD on a Small Island: Development and Use of Sustainable Tourism Development Indicators in Samoa. J. Sustain. Tour. 2002, 10, 363–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Registro de Turismo de Andalucía. Available online: https://www.juntadeandalucia.es/organismos/turismoculturaydeporte/servicios/app/buscador-establecimientos-servicios-turisticos.html (accessed on 26 December 2022).

- Cáceres-Feria, R.; Ballesteros, E.R. Forasteros residentes y turismo de base local. Reflexiones desde Alájar (Andalucía, España). Gaz. de Antropol. 2017, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Secor, A.J. Social surveys, interviews, and focus groups. In Research Methods in Geography. A Critical Introduction; Gomez, B., Jones, J.P., III, Eds.; Wiley-Blackwell: Oxford, UK, 2010; pp. 194–205. [Google Scholar]

- Cope, M. Coding Qualitative Data. In Qualitative Research Methods in Human Geography; Hay, I., Ed.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2010; pp. 281–294. [Google Scholar]

- Sá, E.; Casais, B.; Silva, J. Local development through rural entrepreneurship, from the Triple Helix perspective: The case of a peripheral region in northern Portugal. Inter. J. Entrepreneurial Behav. Res. 2019, 25, 698–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nomenclátor. Available online: https://www.ine.es/nomen2/index.do (accessed on 26 December 2022).

- Sistema de Información Multiterritorial de Andalucía. Available online: https://www.juntadeandalucia.es/institutodeestadisticaycartografia/badea/informe/anual?CodOper=b3_151&idNode=23204 (accessed on 26 December 2022).

- Parques Naturales. Available online: https://www.juntadeandalucia.es/medioambiente/portal/parques-naturales?categoryVal= (accessed on 26 December 2022).

- Guía Digital Patrimonio Cultural de Andalucía. Available online: https://guiadigital.iaph.es/ (accessed on 26 December 2022).

- RENPA. Available online: https://www.juntadeandalucia.es/medioambiente/portal/areas-tematicas/espacios-protegidos/configuracion-renpa (accessed on 26 December 2022).

- Silva-Pérez, R.; Fernández-Salinas, V. Claves para el reconocimiento de la dehesa como “paisaje cultural” de Unesco. An. Geogr. Univ. Complut. 2015, 35, 121–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulero-Mendigorri, A.; Silva-Pérez, R. Paisajes de Sierra Morena: Una cuestión de miradas y de escalas. RER 2013, 96, 35–64. [Google Scholar]

- Silva-Pérez, R.; Ojeda-Rivera, J.F. La Sierra Morena sevillana, a la sombra de la urbe y el mercado. Ería 2001, 56, 255–276. [Google Scholar]

- Araque-Jiménez, E.; Cantarero-Quesada, J.M.; Garrido-Almonacid, A.; Moya-García, E.; Sánchez-Martínez, J.D. Sierra Morena, una lectura geográfica para un destino turístico en ciernes. Cuad. de Turismo 2005, 16, 7–48. [Google Scholar]

- Mulero-Mendigorri, A. Protección y gran propiedad en Sierra Morena: el Parque Natural de la Sierra de Hornachuelos (Córdoba) como caso emblemático. Pap. Geogr. 2003, 38, 115–136. [Google Scholar]

- Márquez-Domínguez, J.A.; Jurado-Almonte, J.M.; Felicidades-García, J.; García-Delgado, F.J. Paisajes Agrarios Andaluces. In Conocer Andalucía; Cano-García, G., Ed.; Tartessos: Sevilla, Spain, 2001; Volume I, pp. 243–326. [Google Scholar]

- García-Delgado, F.J. Ámbitos agrícolas, ganaderos, forestales y pesqueros. In Atlas del Suroeste Peninsular; Márquez-Domínguez, J.A., Dir.; Universidad de Huelva: Huelva, Spain; pp. 125–160.

- Mulero-Mendigorri, A. Sierra Morena como espacio protegido: del olvido tradicional al interés reciente. Investig. Geogr. 2001, 25, 51–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Delgado, F.J. Industrias Cárnicas, Territorio y Desarrollo en Sierra Morena. Ph.D. Thesis, Universidad de Huelva, Huelva, Spain, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Pizarro-Gómez, A.; García-Delgado, F.J.; Pérez-Mora, C. Cambios en la industria de transformación del cerdo ibérico en la Sierra de Huelva (2002–2020). Cuad. Geogr. 2021, 60, 203–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pizarro-Gómez, A.; Šadeikaitė, G.; García-Delgado, F.J. Changes of Dynamics in Local Productive Systems Based on the Iberian Pig Transformation Industry in Western Sierra Morena (Spain). Land 2021, 10, 1343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Delgado, F.J. El espacio turístico. In Atlas del Suroeste Peninsular; Márquez-Domínguez, J.A., Dir.; Universidad de Huelva: Huelva, Spain; pp. 181–208.

- Fernández-Tabales, A.; Hernández-Martínez, E.; Marchena-Gómez, M.J.; Velasco-Martín, A. Estrategias turísticas en el Parque Natural Sierra de Aracena y Picos de Aroche. In Patrimonio Histórico-Artístico de la Provincia de Huelva: Ponencias de las V Jornadas del Patrimonio de la Sierra de Huelva; Almonaster la Real; Nature Park: Andalusia, Spain, 1993; pp. 69–82. [Google Scholar]

- García-Delgado, F.J.; Delgado-Domínguez, A.; Felicidades-García, J. El turismo en la Cuenca Minera de Riotinto. Cuad. de Turismo 2013, 31, 129–152. [Google Scholar]

- Flores-Ruiz, D. Competitividad Sostenible de los Espacios Naturales Protegidos como Destinos Tur_ısticos: un An_alisis comparativo de los Parques Naturales Sierra de Aracena y Picos de Aroche y Sierras de Cazorla, Segura y las Villas. Ph.D. Dissertation, Universidad de Huelva, Spain, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Ballesteros-Pelegrín, G.A. El turismo de naturaleza en espacios naturales. El caso del Parque Regional de las Salinas y Arenales de San Pedro del Pinatar. Cuad. de Turismo 2014, 34, 33–51. [Google Scholar]

- Decreto 20/2002, de 29 de enero, de Turismo en el Medio Rural y Turismo Activo. Available online: https://www.juntadeandalucia.es/boja/2002/14/1 (accessed on 26 December 2022).

- Butler, R.W. The concept of carrying capacity for tourism destinations: Dead or merely buried? Progr. Tour. Hosp. Res. 1996, 2, 283–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saarinen, J. Conflicting limits to growth in sustainable tourism. Curr. Issues Tour. 2014, 18, 903–907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, C.M. Degrowing tourism: Décroissance, sustainable consumption and steady-state tourism. Anatolia 2009, 20, 46–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paül-Carril, V.; Agrelo-Janza, L.M.; Trillo-Santamaría, J.M. Montañas de Trevinca: ¿undertourism en Galicia y overtourism en Sanabria. In Sostenibilidad Turística: Overtourism vs Undertourism; Pons, G.X., Blanco-Romero, A., Navalón-García, R., Troitiño-Torralba, L., Blázquez-Salom, M., Eds.; Societat d’Història Natural de les Balears: Palma de Mallorca, Spain, 2020; pp. 445–456. [Google Scholar]

- Crosby, A. Introducción. In Desarrollo y gestión del turismo en áreas rurales-naturales; Crosby, A., Ed.; Forum Natura: Madrid, Spain, 1996; pp. 3–8. [Google Scholar]

- Rogowski, M. The Impact of COVID-19 Pandemic on Nature-Based Tourism in National Parks. Case Studies for Poland. J. Environ. Manag. Tour. 2022, 13, 572–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esgalhado, C.; Guimaraes, M.H. Unveiling Contrasting Preferred Trajectories of Local Development in Southeast Portugal. Land 2020, 9, 87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez-Martín, M.B.; Armesto-López, X.A.; Cors-Iglesias, M. Percepción del cambio climático y respuestas locales de adaptación: El caso del turismo rural. Cuad. Tur. 2017, 39, 287–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahamonde-Rodríguez, M.; Šadeikaitė, G.; Pérez-Mora, C.; García-Delgado, F.J. Turismo, paisaje y multifuncionalidad en el Parque Natural de las Sierra de Aracena y Picos de Aroche (Huelva, Andalucía). La percepción de los stakeholders. In ¿Renacimiento rural? Los espacios rurales en época de pos-pandemia; Actas del XXI Coloquio de Geografía Rural de la AGE-IV Coloquio Internacional de Geografía Rural ColoRURAL 2022, Santiago de Compostela, Spain, 5–8 de octubre de 2022; Tirado-Ballesteros, J.B., Piñeiro-Antelo, M.A., Paül-Carril, V., Lois-González, R.C., Eds.; ANTE-Universidad de Santiago de Compostela: Santiago de Compostela, Spain; pp. 159–165.

- Hall, C.M.; Gössling, S.; Scott, D. The evolution of sustainable development and sustainable tourism. In The Routledge Handbook of Tourism and Sustainability; Hall, C.M., Gössling, S., Scott, D., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2015; pp. 15–35. [Google Scholar]

- Jeuring, J.H.G.; Haartsen, T. The challenge of proximity: The (un)attractiveness of nearhome tourism destinations. Tour. Geogr. 2017, 19, 118–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pallarès-Blanch, M. The benefits of Nature Reserve Areas in local development: An opportunity to develop a sustainable strategy in peripheral areas. In Naturbanization; Prados-Velasco, M.J., Ed.; CRC Press: London, UK, 2008; pp. 151–174. [Google Scholar]

- Álvarez-Carreño, S.M.; Hernández-López, S.M. La custodia del territorio como instrumento complementario para la protección de los espacios naturales. Revista Catalana de Dret Ambiental 2011, 2, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- March, H.; Hernández, M.; Saurí, D. Assessing domestic water use habits for more effective water awareness campaigns during drought periods: A case study in Alicante, eastern Spain. Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci. 2015, 15, 963–972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olcina-Cantos, J.; Morales-Gil, A.; Rico-Amorós, A.M. Diferentes percepciones de la sequía en España: adaptación, catastrofismo e intentos de corrección. Investig. Geogr. 2000, 23, 5–46. [Google Scholar]

- Mulero-Mendigorri, A. Fronteras y territorios: La gestión de las áreas protegidas en cuestión. Cuad. Gec. 2018, 57, 61–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morén-Alegret, R.; Milazzo, J.; Romagosa, F.; Kallis, G. ‘Cosmovillagers’ as Sustainable Rural Development Actors in Mountain Hamlets? International Immigrant Entrepreneurs’ Perceptions of Sustainability in the Lleida Pyrenees (Catalonia, Spain). Europ. Countrys. 2021, 13, 267–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mercado-Alonso, I.; Fernández-Tabales, A.; Bascarán-Estévez, M.V. Turismo rural y crecimiento inmobiliario en espacios de montaña media. El caso de la Sierra de Aracena. Polígonos 2012, 23, 181–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domínguez-Gómez, J.A.; Lennartz, T. Turismo rural y expansión urbanística en áreas de interior. Análisis socioespacial de riesgos. Rev. Int. Sociol. 2015, 73, e006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blackstock, K.L.; White, V.; McCrum, G.; Scott, A.; Hunter, C. Measuring responsibility: An appraisal of a Scottish national park’s sustainable tourism indicators. J. Sustain. Tour. 2008, 16, 276–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ARGOS. Available online: https://www.juntadeandalucia.es/servicioandaluzdeempleo/web/argos/buscarContratos.do (accessed on 26 December 2022).

- Bjarnason, T.; Stockdale, A.; Shuttleworth, I.; Eimermann, M.; Shucksmith, M. At the intersection of urbanisation and counterurbanisation in rural space: Microurbanisation in Northern Iceland. J. Rural Stud. 2021, 87, 404–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garzón-García, R. Las consecuencias territoriales de la expansión reciente de los espacios naturales protegidos: análisis de la Sierra Morena andaluza, Ph.D. Thesis, Universidad de Córdoba, Spain, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Lane, B. Sustainable rural tourism strategies: A tool for development and conservation. J. Sustain. Tour. 1994, 2, 102–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deller, S. Rural poverty, tourism and spatial heterogeneity. Ann. Tour. Res. 2010, 37, 180–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pato, L. Entrepreneurship and innovation towards rural development evidence from a peripheral area in Portugal. Europ. Countrys. 2020, 12, 209–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hjalager, A.M. Agricultural diversification into tourism: Evidence of a European Community development programme. Tour. Manage. 1996, 17, 103–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LaPan, C.; Barbieri, C. The role of agritourism in heritage preservation. Curr. Issues Tour. 2014, 17, 666–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lordkipanidze, M.; Brezet, H.; Backman, M. The entrepreneurship factor in sustainable tourism development. J. Clean Prod. 2005, 13, 787–798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Decreto 28/2016, de 2 de febrero, de las viviendas con fines turísticos…. Available online: https://www.juntadeandalucia.es/boja/2016/28/6 (accessed on 26 December 2022).

- Cànoves-i-Valiente, G.; Villarino-Pérez, M.; Priestley, G.K.; Blanco-Romero, A. Rural tourism in Spain: an analysis of recent evolution. Geoforum 2004, 35, 755–769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Middleton, V.; Hawkins, R. Sustainable Tourism, A Marketing Perspective; Butterworth-Heinemann: Oxford, UK, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Hall, C.M. Tourism and biodiversity: More significant than climate change? J. Herit. Tour. 2010, 5, 253–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harvey, D. A Brief History of Neoliberalism; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Saarinen, J. Critical sustainability: Setting the limits to growth and responsibility in tourism. Sustainability 2014, 6, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bosak, K. Tourism, development, and sustainability. In Reframing Sustainable Tourism; McCool, S.F., Bosak, K., Eds.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2016; pp. 33–44. [Google Scholar]

- Helgadóttir, G.; Einarsdóttir, A.V.; Burns, G.L.; Gunnarsdóttir, G.Þ.; Matthíasdóttir, J.M.E. Social sustainability of tourism in Iceland: A qualitative inquiry. Scand. J. Hosp. Tour. 2019, 19, 404–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Font, X.; McCabe, S. Sustainability and marketing in tourism: Its contexts, paradoxes, approaches, challenges and potential. J. Sustain. Tour. 2017, 25, 869–883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mowforth, M.; Munt, I. Tourism and sustainability: Development and new tourism in the Thir World, 2nd ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Peng, K.L.; Lin, P.M. Social entrepreneurs: Innovating rural tourism through the activism of service science. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. M. 2016, 28, 1225–1244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, E.; Cohen, S.A. Authentication: Hot and Cool. Ann. Tour. Res. 2012, 39, 1295–1314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romagosa, F.; Mendoza, C.; Mojica, L.; Morén-Alegret, R. Inmigración internacional y turismo en espacios rurales. El caso de los “micropueblos” de Cataluña. Cuad. de Turismo 2020, 46, 319–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trišić, I.; Štetić, S.; Privitera, D. The importance of nature-based tourism for sustainable development-A report from the selected biosphere reserve. J. Geogr. Inst. Jovan Cvijic 2021, 71, 203–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Troitiño-Vinuesa, M.A.; de-Marcos-García-Blanco, F.J.; García-Hernández, M.; del-Río-Lafuente, M.I.; Carpio-Martín, J.; de-la-Calle-Vaquero, M.; Abad-Aragón, L.D. Los espacios protegidos en España: significación e incidencia socioterritorial. B. Asoc. Geogr. Esp. 2005, 39, 227–265. [Google Scholar]

- Marchena-Gómez, M. Las perspectivas de futuro del turismo andaluz: problemas territoriales y funcionales. Treballs de Geografia 1990, 43, 59–70. [Google Scholar]

- García-Delgado, F.J.; Felicidades-García, J. Técnicas y herramientas aplicadas a la gestión de recursos turísticos. In Manual de Gestión de Destinos Turísticos; Flores-Ruiz, D., Coord.; Tirant: Valencia, Spain, 2014; pp. 181–216. [Google Scholar]

- Márquez-Fernández, D.; Foronda-Robles, C.; García-López, A.M.; Galindo-Pérez-de-Azpillaga, L. El precio de la sostenibilidad rural en Andalucía: el valor de Leader II. B. Asoc. Geogr. Esp. 2006, 41, 295–314. [Google Scholar]

- Esparcia-Pérez, J.; Noguera-Tur, J.; Pitarch-Garrido, M.D. LEADER en España: Desarrollo rural, poder, legitimación, aprendizaje y nuevas estructuras. D.A.G. 2000, 37, 95–113. [Google Scholar]

- Engelmo-Moriche, A.; Nieto-Masot, A.; Mora-Aliseda, J. La sostenibilidad económica de las ayudas al turismo rural del Método Leader en áreas de montaña: dos casos de estudio españoles (Valle del Jerte y Sierra de Gata, Extremadura). B. Asoc. Geogr. Esp. 2021, 88, 1–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrzelka, P.; Krannich, R.; Brehm, J.; Trentelman, C. Rural Tourism and Gendered Nuances. Ann. Tour. Res. 2005, 32, 1121–1137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Šadeikaitė, G. Supporting Sustainable Tourism Development through Improved Measurement: A Case Study of European Tourism Destinations. Ph.D. Thesis, Universidad de Alicante, Alicante, Spain, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Bramwell, B.; Sharman, A. Collaboration in local tourism policymaking. Ann. Touris. Res. 1999, 26, 392–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bramwell, B.; Lane, B. Collaboration and partnerships for sustainable tourism. J. Sustain. Tour. 1999, 7, 179–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Code | Question | Topics |

|---|---|---|

| (q1) | What function do the nature park and biosphere reserve have in your destination (and others)? | (2) |

| (q2) | What is the value of the landscape in tourism? | (2) |

| (q3) (a) | How do you perceive sustainable tourism development in your destination? | (2) |

| (q4) (b) | Does sustainability have a substantial effect on the tourism development of your destination? Why? | (1)(2)(3) |

| (q5) (a) | What kind of conflicts related to sustainability exists between stakeholders? | (2)(3) |

| (q6) (a) | Could you give a practical example of sustainable tourism development in your destination? What would you improve? | (2) |

| (q7) | What happens in the context of global change with your destination? | (2)(3) |

| (q8) | Are there difficulties in managing the tourist space? | (2) |

| (q9) (b) | Does tourism contribute to local development? | (1) |

| (q10) | What consequences has COVID-19 had on the destination? | (2)(3) |

| NtP | Province | No. municipalities (a) | Area (ha) | Total population | Population density (pop./km2) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NtP | Total(b) | 1960(b) | 2020(b) | ||||

| SAPA | Huelva | 28 (20) | 186,827 | 280,318 | 72,478 | 36,202 | 12.91 |

| SNS | Sevilla | 10 (4) | 177,484 | 238,486 | 55,452 | 24,790 | 10.39 |

| SH | Córdoba | 5 (0) | 60,031 | 171,094 | 32,213 | 14,998 | 8.77 |

| Total/Mean | 43 | 424,342 | 689,898 | 162,103 | 75,990 | 10.69 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).