Basic Structure of the Eye[1]

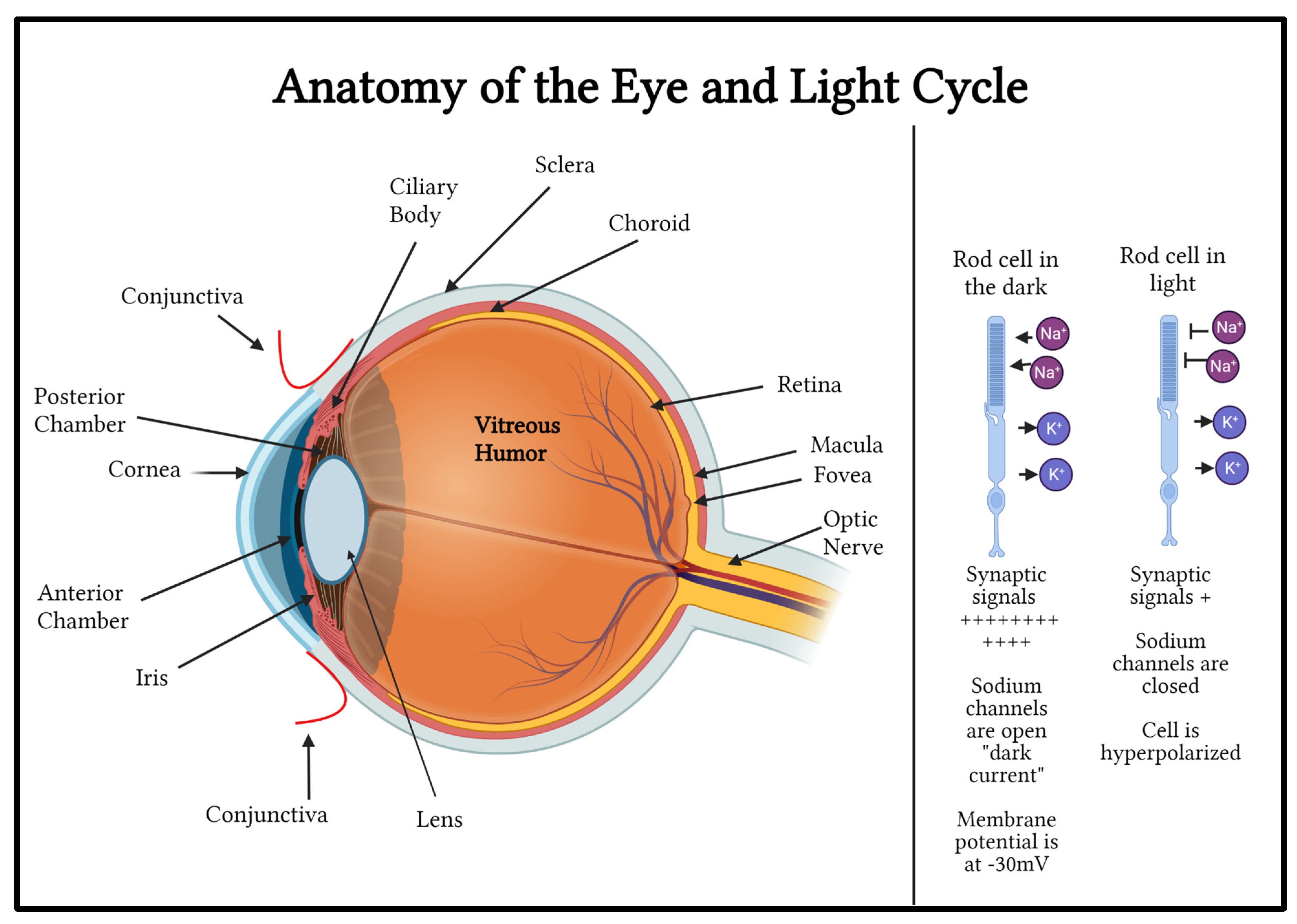

The eye is a complex and incredibly important organ in the human body. The eye contains several key structures, each with important functions in human vision (

Figure 1). The clear conjunctiva covers the sclera and the inner surface of the eyelid. The cornea is the eye’s dome-shaped clear outer layer that is attached to the opaque, white sclera. The curved cornea allows for a wide visual field and has many layers, including the epithelium or the outer layer. One unique aspect of the cornea is that it does not contain blood vessels; instead, it receives oxygen and nutrients from tears, the aqueous humor, and the environment. The pupil is located in the center of the iris. It is a black hole in the center of the muscular curtain-like iris that contracts in brightly lit environments, using its sphincter pupillae muscle, and expands in dark environments to allow more light into the eye, using its dilator pupillae muscle. The iris is the colored part of the eye that surrounds the pupil. Pigment cells in the iris tissue cause it to be colored. The lens is located behind the pupil. The lens changes shape depending on how far an object is from the eye. The ciliary body muscle group is what allows the lens to change shape. The retina is a layer of tissue that relays visual input to the brain. The retina is the innermost layer of the eye and consists of different types of cells, including retinal ganglion cells (RGC), bipolar cells (interneurons), and photoreceptors. Photoreceptors include rods and cones. Rhodopsin (Rho) is a well-known photosensitive protein found in the rod cells of the retina and detects light/dark contrast[

2]. Rho converts photons into chemical signals that can trigger biological processes by allowing the brain to perceive light stimuli. The rods are depolarized in the dark state. Sodium channels are open. When light hits the rods, the rod cells become hyperpolarized because sodium channels close. Cone opsins are also photosensitive receptors in the cone cells of the retina and detect color[

1]. The conversion of light stimuli to chemical stimuli is called signal transduction[

2]. The membrane potential of the photoreceptor rod outer segment is about -30 volts in the dark due to continuous flow of sodium into the rods’ outer segment through sodium-specific channels. These channels are kept open in the dark by second messenger cyclic GMP which is produced continuously by the enzyme guanylate cyclase. When photons of light strike the light sensitive pigments in the rods and cones, the pigment protein changes form and activates transducin which activates phosphodiesterase enzymes. Phosphodiesterase enzyme metabolizes cyclic GMP. Reduced cyclic GMP reduces the dark current caused by sodium conductance, causing hyperpolarization. In the presence of light, photoreceptor cells release fewer neurotransmitter molecules into the synapse with the bipolar cells. This depolarization of photoreceptors in the dark and hyperpolarization of the photoreceptors in the presence of light is called the light cycle[

2].

The yellow-colored macula is located in the center of the retina and allows for detailed vision. The fovea is the center of the macula, and it plays a vital role in detail perception. The cells in the retina convert light into chemical and electrical energy, which is then transmitted to the optic nerve. The optic nerve allows for communication between the eye and the brain. Over one million axons of RGCs converge to form the optic nerve. The retinal pigment epithelium (RPE) is located between the retina and the choroid. It serves many functions, including protecting the retina from excess light exposure, supplying glucose for energy, maintaining the pH level of the retina, removing dead photoreceptor cells, and secreting materials promoting the growth and sustenance of the choroid and retina[

1].

The Eye’s Accommodation for Near and Far Vision

Light is focused onto the retinal photoreceptor layer by the curved cornea, pupil, and the accommodating lens for image capture. The lens has the ability to change its focal length by becoming flatter to focus the light from far objects onto the retinal screen and to become more convex when focusing on near objects.

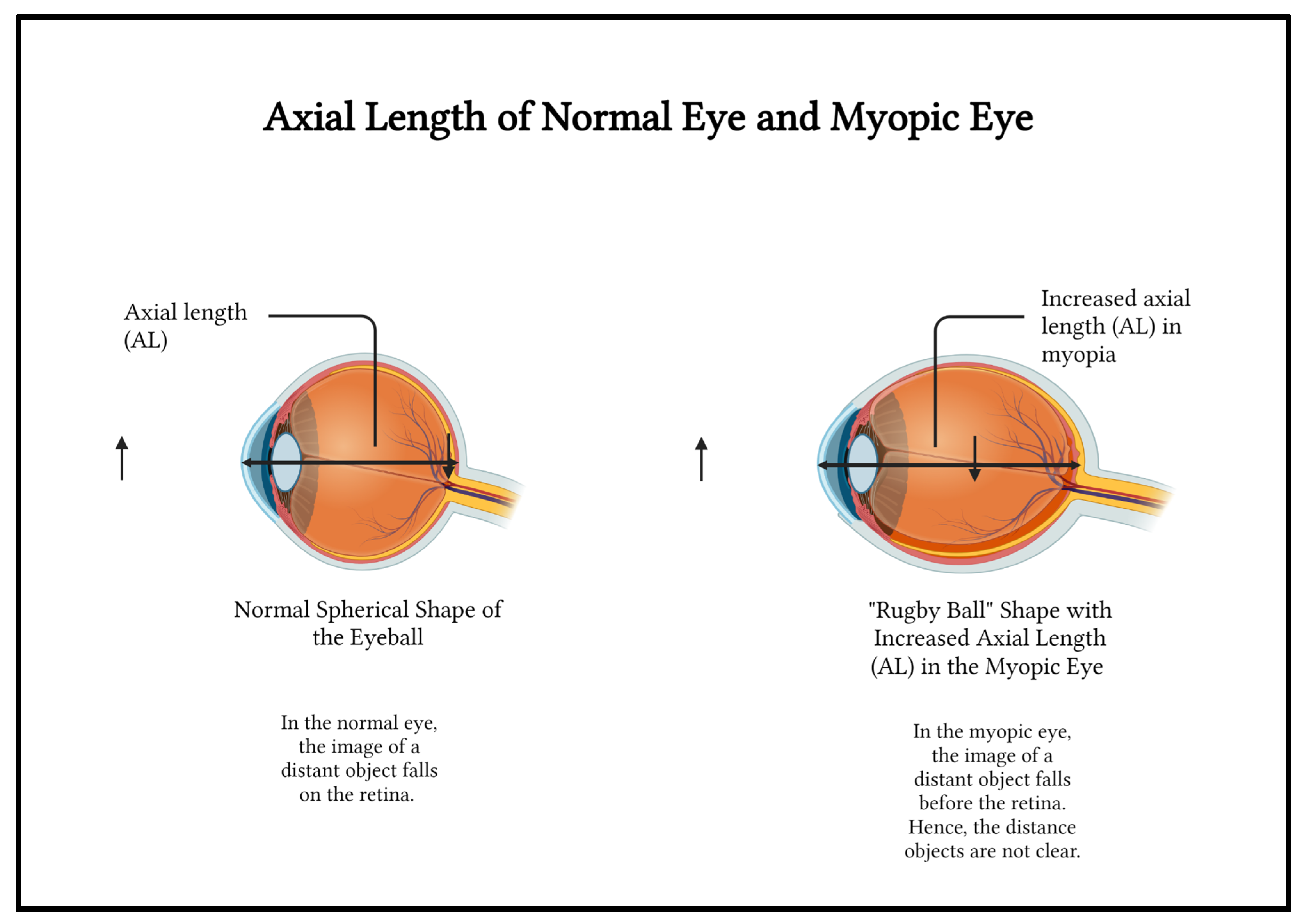

Increased Incidence of Eye Strain, Change in Eye Shape, and Myopia Due to Overuse

The eye was not created to constantly focus on near objects and utilize artificial light. Therefore, when a person focuses on a computer screen or smartphone screen for long periods of time, the accommodation function of the lens becomes slower and strained.

In a person who is physically active and does not overuse their eye, the eye has a spherical basketball-like shape. The eye is able to accommodate for near and far objects and is said to be emmetropic. In the normal eye, the image of a distant object falls on the retina and the image is clearly sensed (

Figure 2).

Overuse causes the eye to grow into a oblong rugby ball-like shape instead of the usual spherical, basketball-like shape if the overuse occurs during the growing years causing myopia or nearsightedness (

Figure 2).[

3,

4,

5] The distance between the anterior pole the most convex point in the front of the eye and the posterior pole the most convex point in the back of the eye is axial length (AL). The axial length (AL) of the myopic eye is greater than the normal eye[

3]. The incidence of myopia has increased with increasing electronic device use[

4]. In the myopic eye, the image of a distant object falls before the retina. Hence, the distance objects are not clear (

Figure 2).

Compared with healthy patients, the aqueous humor of patients with high myopia demonstrates significant differences in metabolites related to nitric oxide synthase (NOS) and oxidative stress, especially in high myopia (HM) patients[

7]. HM patients present with increased levels of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and hepatocyte growth factor (HGF) in the aqueous humor[

8]. These growth factors cause the abnormal growth of the eyeball anteroposteriorly causing the oblong shape. Studies show a disproportionate production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) in patients with myopia compared with healthy patients, confirming that ROS is a cause of the pathogenesis in these diseases. ROS plays an important role in the pathophysiology of many diseases, including myopia. Blue light from monitors causes eye damage[

7,

9].

Excessive digital eye strain (DES) occurs in the small extraocular muscles that rotate the eye and turn the eye inward to focus on a computer or video display terminal (VDT) or smartphone that is kept close to the face[

6]. Symptoms include dry eyes and headaches. There is inadequate blinking leading to dry eye disease (DED). Prolonged eye strain leads to headaches.

Significance of COVID-19 and Increased Incidence of Eye Strain and Myopia

In general, studies suggest that government measures such as mandatory annual vision screening in school-aged children, eye health education, vitamin supplementation, vision screening, and vision benefits through Medicare and Medicaid may help to decrease the incidence and prevalence of eye disorders and vision problems[

10,

11]. However, since digital eye strain is present in 50% of computer, smartphone, and handheld device users, and almost everyone has used a digital screen since the COVID-19 pandemic due to remote learning and social distancing, there is an increased need for public health initiatives to educate parents, children, and the general population about the adverse effects of excessive screen time and the importance of proper nutrition.

The World Health Organization (WHO) recommends no screen time for children less than 2 years and no more than 1 hour for children between the ages of 2 and 5[

12]. Studies in the United States suggest that the pre-pandemic mean total screen time was 4.4 hours per day. This mean screen time increased by 1.75 hours per day in the first pandemic period (December 2020 to April 2021) and 1.11 hours per day in the second pandemic period (May 2021 to August 2021) in adjusted models[

13]. Both recreational screen time and educational screen time increased in the two pandemic periods. In a Malaysian study of school-aged children, the prevalence of myopia increased 1.4 to 3 times in 2020 compared with the previous 5 years. A substantial myopic shift occurred in young children 6-8 years of age, suggesting that their refractive status may be subject to environmental changes compared to older children[

14].

Blue Light Contributes Significantly to Oxidative Stress and Eye Damage

Blue light is light with a wavelength of 380 to 500 nanometers. Blue light is a shorter wavelength that penetrates deeper into the eye with a higher energy compared to other colors. The cornea absorbs light of wavelength less than 295 nanometers. The lens absorbs a wavelength of 400 nanometers[

15]. Blue light causes ROS overproduction retinal apoptosis and damage to mitochondria in photoreceptors and ganglion cell axons.

UV light is light wavelength 100-400 nanometers. UV-A light is a type of UV light with wavelength 320-400 nanometers (long waves) and UV-B is another type of UV light with wavelength 290-320 nanometers (short waves). Excessive UV ray exposure can cause an increase in ROS.

Oxidative Stress and Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS) in Cell Organelles

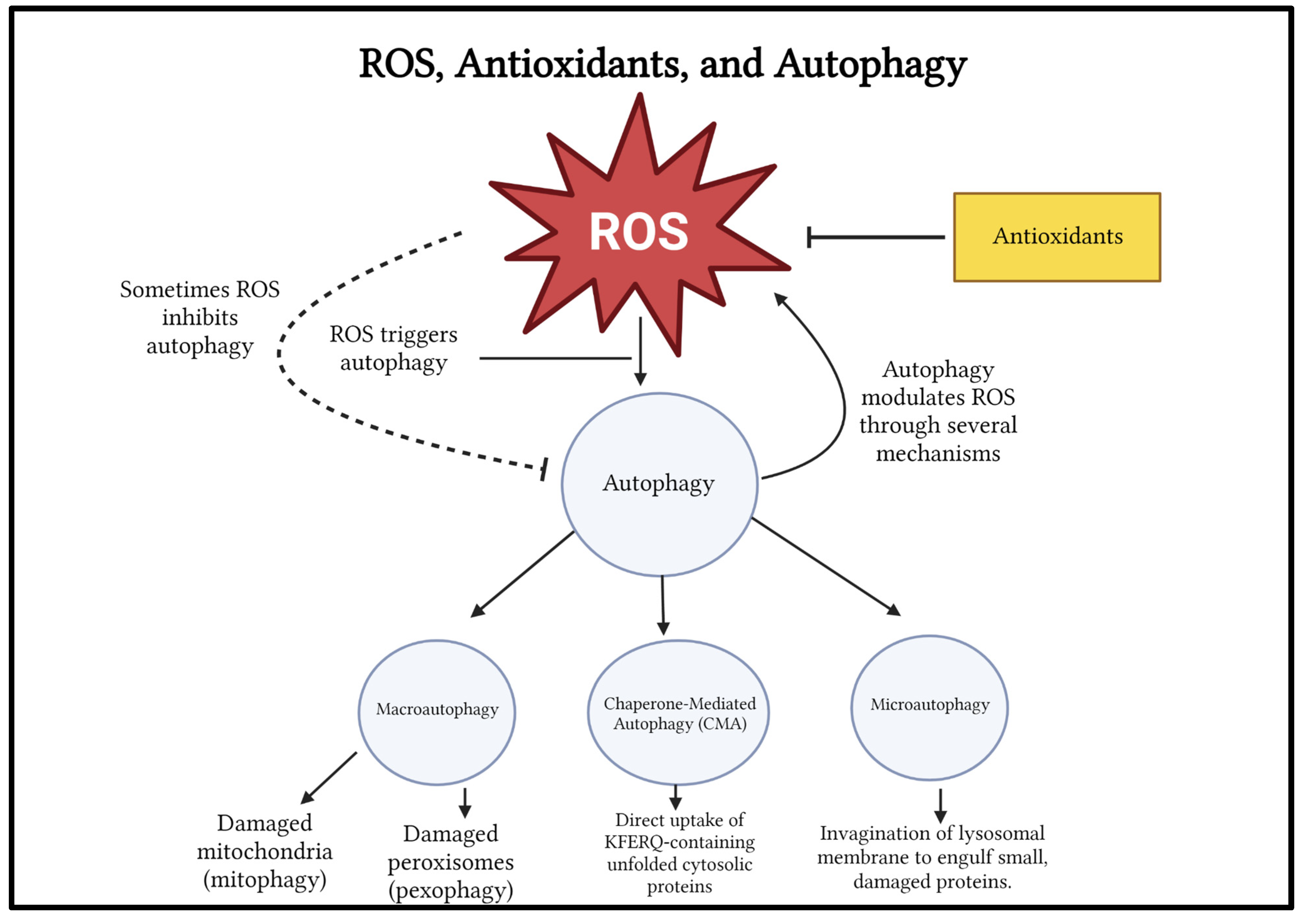

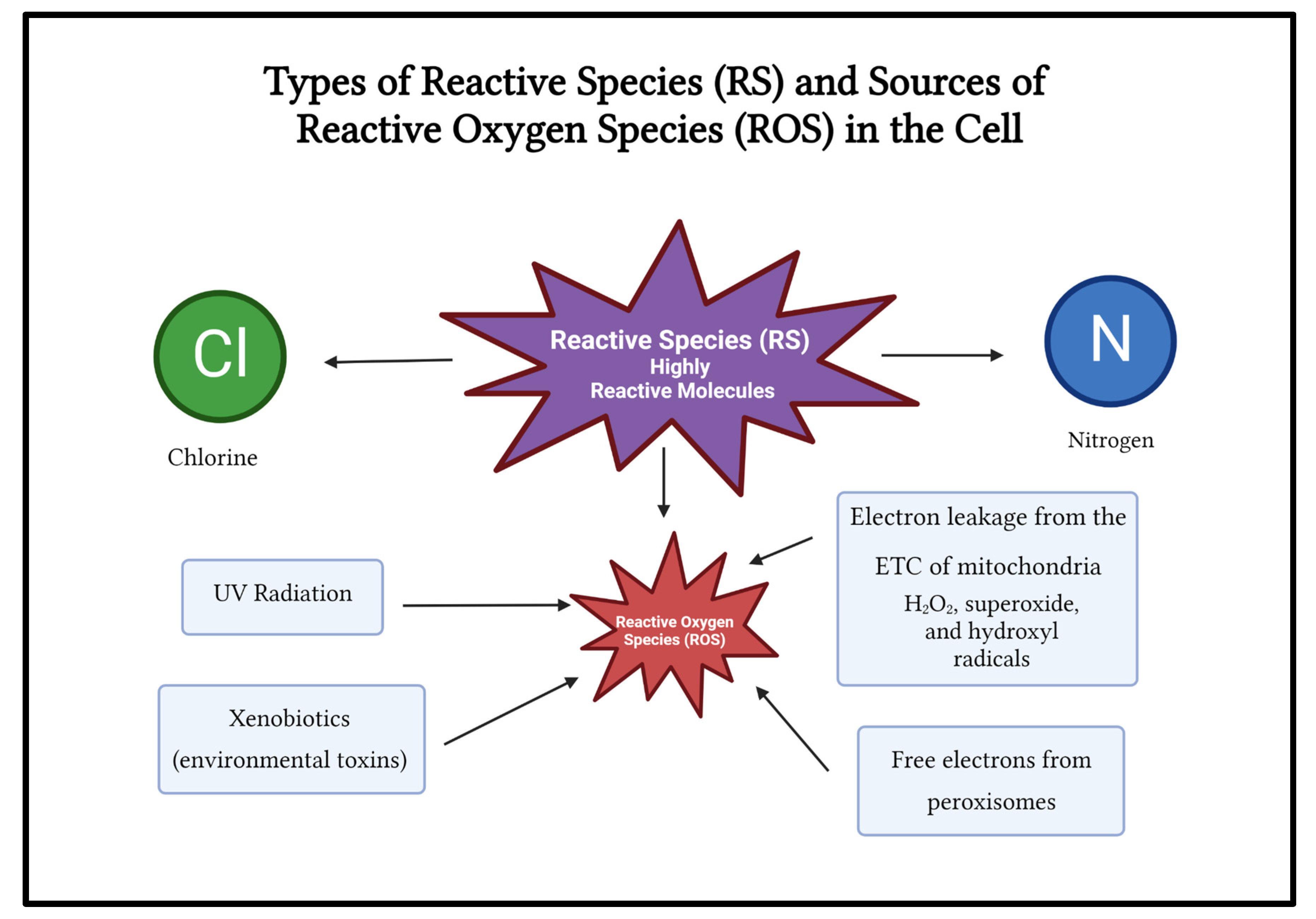

Reactive species (RS) include ROS, free radicals, nitrogen, and chlorine (

Figure 3). Examples of ROS include peroxide, superoxide, hydroxyl radical, singlet oxygen, and alpha oxygen. ROS are involved in metabolic processes such as cell signaling and homeostasis. ROS can be endogenous or exogenous.

Endogenous sources of ROS include intracellular mitochondrial ROS (90%) generated by electron leakage from the electron transport chain (ETC) in the inner membrane of mitochondria and from chemical reactions in peroxisomes[

16].

Mitochondrial ROS such as hydrogen peroxide (H

2O

2), superoxide (O

2-), and hydroxyl (OH-) radicals are usually contained within the ETC of the mitochondria[

16].

When mitochondria are damaged or under stress, electron leakage from the ETC can generate excess ROS which freely diffuse out of the mitochondria and randomly oxidize important biomolecules such as protein, nucleic acids, and lipids, damaging these macromolecules[

17]. Thus, excess ROS causes damage to organelles and proteins by oxidizing them and making them ineffective by irreversible damage to their structure. Endogenous ROS can also be generated through the enzymatic activity of NADH oxidases (Nox enzymes), and Leukotriene oxidases (Lox enzymes).

Excessive ROS leads to damaged mitochondria. Damaged mitochondria are recycled by a process called mitophagy (autophagy of mitochondria). In mitophagy, damaged mitochondria are packaged into autophagosomes and delivered to a lysosome for autophagic breakdown and recycling. Mitochondria-rich tissues absorb blue light. In the presence of excessive blue light, mitochondrial structure and function is destroyed by oxidative stress and mitochondria-signaled cell death occurs[

18]. Photoreceptor cells are prone to ROS-induced mitochondrial damage because the photoreceptors cells of the retina, especially cones, are rich in mitochondria.

The peroxisome is another organelle that produces ROS by releasing free electrons from several oxidases. Peroxisomes contain many antioxidant enzymes to remove excessive ROS, including glutathione peroxidases (GPX), catalase, and superoxide dismutase[

17]. Damaged peroxisomes are removed by pexophagy, a term for the autophagic breakdown of peroxisomes.

Exogenous Sources of ROS

UV radiation is a major environmental source of ROS. UV rays cause much damage to the skin and eyes. UV rays can induce ROS by affecting enzyme catalase and upregulating nitric oxide synthase synthesis (NOS). UV-A light can damage central vision and UV-B light can damage the lens and cornea[

19].

The detoxification of xenobiotic compounds such as environmental toxins and pharmaceutical drugs can generate ROS, potentially damaging organs like the kidneys and liver, the main organs where detoxification occurs.

What is Autophagy?

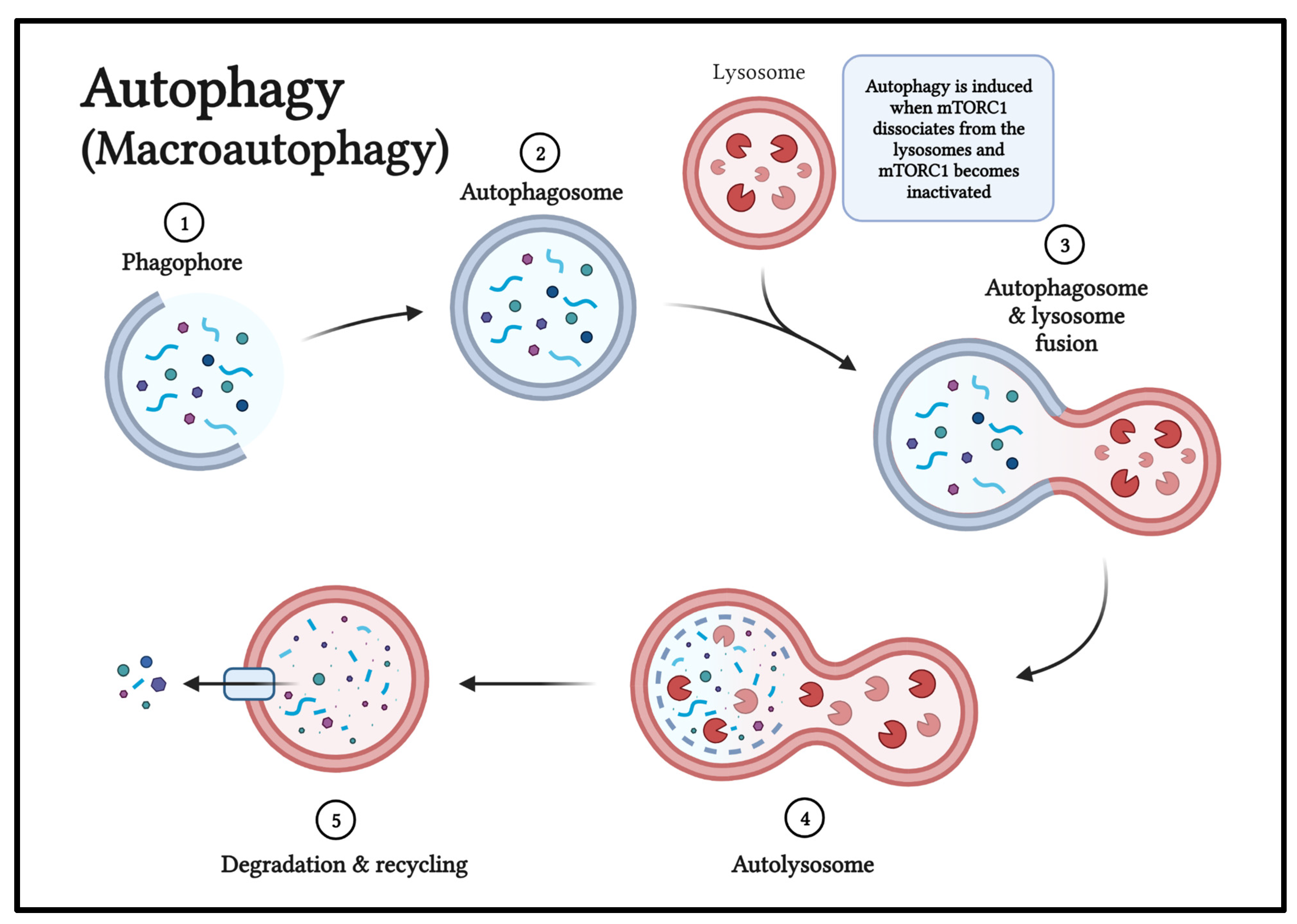

Autophagy is a process by which damaged organelles and unfolded cytoplasmic proteins are delivered to lysosomes and recycled[

20].

Autophagy is a very important quality control system for various cellular components involved in ROS generation. Autophagy involves many phases: initiation, phagophore nucleation, elongation and autophagosome formation, autophagosome-lysosome fusion, and cargo degradation[

21].

Figure 4.

ROS and Autophagy relationship, and different types of autophagy.

Figure 4 created by Sakthishreenidhi “Shree” Manivel using BioRender.com.

Figure 4.

ROS and Autophagy relationship, and different types of autophagy.

Figure 4 created by Sakthishreenidhi “Shree” Manivel using BioRender.com.

Figure 5.

The phases of macroautophagy include: initiation, phagophore nucleation, elongation and autophagosome formation, autophagosome-lysosome fusion, and cargo degradation and recycling. Figure 5 created by Sakthishreenidhi “Shree” Manivel using BioRender.com.

Figure 5.

The phases of macroautophagy include: initiation, phagophore nucleation, elongation and autophagosome formation, autophagosome-lysosome fusion, and cargo degradation and recycling. Figure 5 created by Sakthishreenidhi “Shree” Manivel using BioRender.com.

Excessive ROS Causes Disease Pathogenesis

The elevation of intracellular ROS is known as oxidative stress. Intracellular ROS are involved in regulating cellular physiology. Excess ROS may oxidize organelles, proteins, lipids, and nucleic acids, resulting in cellular damage[

20]. Abnormal ROS production has been implicated in the pathogenesis of many diseases, including neuronal, ocular, and cardiovascular disease[

20,

23,

24].

ROS triggers the autophagy pathway to maintain redox homeostasis and to remove oxidized organelles and other components (

Figure 4).

ROS may inhibit autophagy, most likely by directly oxidizing autophagy-related ATG proteins (macroautophagy signaling proteins) in yeast and ATG homologous proteins in humans (ATG 7 and ATG 10) or by likely inactivating autophagy modulating factors such as transcription factor EB (TFEB) and phosphatase and tensin homolog encoded by the PTEN gene.

ROS-Induced Cell Death

Sometimes, cells die due to excessive ROS. Cysteine and glutamine (antioxidants) supplementation rescue cells from ROS-induced cell death.There are different types of cell-death: necrosis, apoptosis or programmed cell death, ferroptosis characterized by loss of mitochondrial cristae, ROS cell death, and autophagic cell death. This article mainly focuses on ROS, autophagy, and ROS-induced and autophagic cell death.

Why is Autophagy Important to the Normal Functioning of Cells?

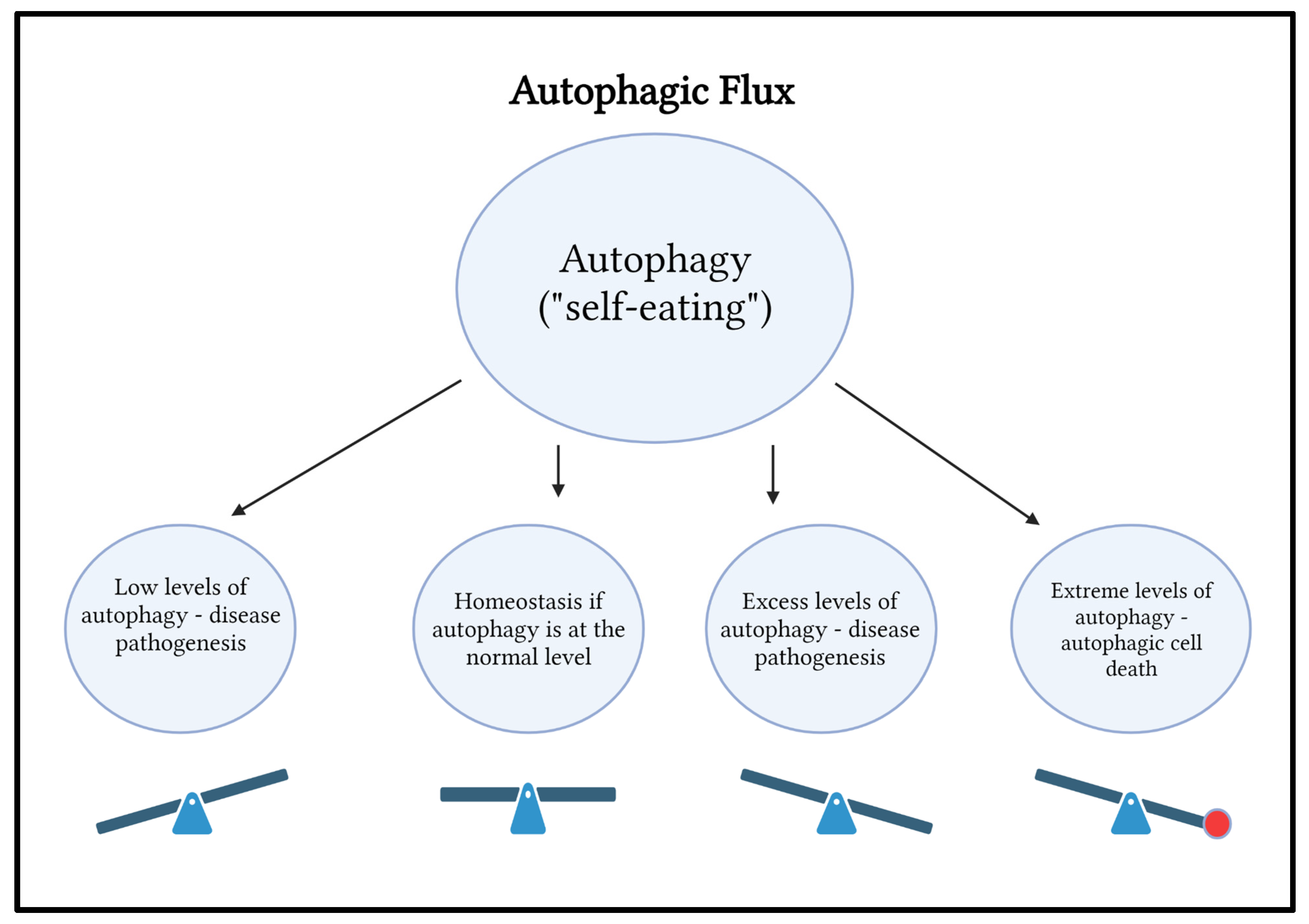

Autophagy is a self-degradative cellular process that helps the human body maintain homeostasis by removing damaged, malfunctioning, pathogenic, or dead organelles and material from the body. This process of “self-eating” can be both beneficial and harmful.

Autophagy Modulates ROS Levels Through Several Mechanisms

Autophagy removes oxidized organelles and proteins to protect cells. Autophagy is a form of quality control for various cellular components like mitochondria, peroxisomes, and proteins that are involved in ROS generation. ROS levels are regulated through transcription factors such as nuclear factor-erythroid factor 2-related factor 2 (NRF2) and p53 in the activation feedback loop and by the clearance of organelles damaged by ROS[

20].

Types of Autophagy

There are different types of autophagy, including macroautophagy, chaperone-mediated autophagy (CMA), and microautophagy[

20].

Macroautophagy In macroautophagy, specific cargo adapters recruit targets such as mitochondria and peroxisome and mark them for delivery to autophagosomes. Sequestome (p62) associates with ubiquitinated (Coenzyme Q) cargo proteins via the ubiquitin-associated motif. NBR1 associates with autophagosomal protein LC3 via the LC3-interacting region (LIR) motif.

Mitophagy is a process of selective autophagy that degrades impaired mitochondria. Pexophagy is a form of selective autophagy that recycles impaired peroxisomes.

Chaperone-mediated autophagy (CMA) is a chaperone (heat shock protein HSC70)-dependent degradation pathway that delivers cytosolic unfolded KFERQ pentapeptide (a degradation signal)-containing proteins to the lysosome by binding with lysosomal-associated membrane protein 2A (LAMP-2A), a transmembrane protein that is involved in protein translocation from the cytosol to the lysosomal lumen. Unfolded proteins containing KFERQ pentapeptide are removed by chaperone-mediated (CMA). In oxidative stress, proteins containing KFERQ pentapeptide become unfolded and expose the KFERQ sequence for binding with constitutive heat shock protein 70 (HSC70). Chaperone-associated complexes are translocated to lysosomes and imported to LAMP-2A for degradation.

Microautophagy is the process by which a micro-portion of the lysosomal membrane engulfs autophagic cargos, including proteins and organelles in cells. It is essential to understand the mode of action of ocular supplements and drugs.

In a sense, autophagy is like a “seesaw” (Figure 6).

Autophagy is like a seesaw (

Figure 6). Both excess autophagy and an insufficient amount of autophagy contribute to infections, cancers, cardiovascular diseases, and impaired immunity. Excessive oxidative stress-induced autophagy may lead to cell death, which is referred to as autophagic cell death.

Although autophagy occurs throughout the body, this paper will focus on the role of autophagy within the eye and its pro-survival and pro-death characteristics. When autophagy removes dangerous and damaged material, it is pro-survival. Autophagy increases the survival of the cell in this instance. However, when the cell has too many damaged organelles and toxic material, there is autophagic cell death.

Role of Autophagy in the Eye

The autophagic pathway plays a protective role in the retina, preventing the buildup of damaged organelles in retinal degenerative diseases. Autophagy inhibitors such as chloroquine and hydroxychloroquine are harmful and can cause eye disease.

The phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3K)/AKT/mTORC1 pathway is a major growth regulatory pathway of the cell and also regulates autophagy. Autophagy is induced when the mammalian target of rapamycin complex 1 (mTORC1) dissociates from the lysosomes and mTORC1 becomes inactivated (

Figure 5). mTOR controls the balance between anabolic (making molecules) and catabolic (breaking down molecules) processes to control cell growth, division, and autophagy/stress response.The mammalian target of rapamycin 1 (mTOR1) pathway is a master regulator of cellular growth and division, and controls processes including autophagy, cell proliferation, and angiogenesis. Activation of the mTOR pathway has been identified in benign and malignant neurofibromatous tumors. Activation of autophagy by inhibition of the mTOR pathway could be one potential therapy for glioblastoma patients.

Role of Autophagic Flux in the Body

Autophagy is protective at certain levels and destructive at others. When the body is well nourished, autophagy keeps the system in an anabolic state.

In fact there is reciprocal regulation of ROS and autophagy (

Figure 4). ROS triggers autophagy, and sometimes ROS inhibits autophagy. Autophagy modulates the levels of ROS through many mechanisms.

Role of Antioxidants in the Eye

Antioxidants are natural substances that chemically react with and neutralize/ decrease reactive oxygen species (ROS) and suppress ROS-induced autophagy. Antioxidants such as Vitamin A, Vitamin C, Vitamin E, beta carotene and other related carotenoids, lutein, zeaxanthin, minerals such as selenium and magnesium, glutathione, coenzyme Q10, alpha lipoic acid, flavonoids, phenols, and polyphenols act as natural defenses in the body by preventing damage from excessive ROS[

25]. Some antioxidants can be synthetic, which are especially used in the food industry.

Where Do Antioxidants Work in the Eye?

Vitamin C Ascorbic acid (Vitamin C) works as a powerful antioxidant in the lens. Vitamin C lowers the risk of developing cataracts and slows the progression of AMD and visual acuity loss in combination with other essential nutrients[

26]. Vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) is a driver of increased leakage of fluid through permeable layers of tiny blood vessels in the retina and macula. Studies suggest that Vitamin C can help prevent VEGF-induced increases in blood vessel permeability and leakage. Vitamin C tightens the vascular endothelium[

26,

27].

Vitamin A is a lipid-soluble antioxidant concentrated in lens fibers and membranes[

28]. Vitamin A is required for photoreceptor rhodopsin (visual purple protein in the rods) regeneration. Rhodopsin is the primary photoreceptor of rods. Vitamin A is essential for night vision. Vitamin A deficiency is the leading cause of childhood blindness in the world. Some scientists think there is a connection between increased axial length and threshold level of Vitamin A in myopia. Vitamin A may inhibit cataract formation by reducing photo-ferroptosis. Ferroptosis is a form of ROS-induced death that occurs when ROS damages lipids and it is a process of regulated necrosis. Photoferroptosis is when excess light-induced cell death characterized by loss of cristae in mitochondria occurs in the lens lipids and stabilizing lens cell membranes. Additionally, Vitamin A is beneficial in the healthy function of the ocular surface cornea and conjunctiva. Vitamin A deficiency leads to softening of the cornea, conjunctival abnormalities, and night blindness.

Vitamin E interacts with selenium and glutathione peroxidase to prevent the formation of damaging oxidative products[

29]. Vitamin E is a helper to the nutrient lutein and protects the RPE cells. Vitamin E is found in foods that contain fat, including vegetable oils such as wheat germ oil, corn oil, and soybean oil. Vitamin E is also found in sunflower seeds, nuts, and dark leafy green vegetables.

Lutein and Zeaxanthin-Carotenoids improve visual function, reduce the risk and slow the progression of age-related macular degeneration and cataracts[

30]. Lutein and zeaxanthin also suppress in diabetic retinopathy and retinopathy of prematurity. A normal diet contains 1 to 3 mg of lutein, while 5 to 10mg is beneficial for the eye. However, 6mg of lutein is required to slow the risk of AMD. Organic vegetables and fresh vegetables have high levels of antioxidants, including lutein and zeaxanthin. Government measures to increase education and to ensure lower priced fresh vegetables availability in all areas, especially food deserts, are important in the fight against eye diseases.

Lutein and zeaxanthin are present in corn egg yolk, carrots, and orange-yellow peppers, giving these foods their bright orange and yellow colors. Lutein and zeaxanthin are found throughout the nervous system but have the highest concentration in the yellow-colored macula of the eye.Lutein and zeaxanthin act as a filter for damaging blue light in the macula. Parsley, kale, spinach, and pistachio are also good sources of lutein and zeaxanthin. Corn and eggs contain both lutein and zeaxanthin, as well[

28,

31].

Magnesium Magnesium is a powerful cofactor to several antioxidant enzymes involved in free radical trapping, especially superoxide dismutase (SOD), involved in free radical trapping[

29,

32,

35]. Magnesium is one of the major elements required to maintain cell membrane function, energy metabolism, and synthesis of nucleic acid. Magnesium has been shown to improve the ocular blood flow in patients with glaucoma and may protect the retinal ganglion cells (RGCs) from oxidative stress and apoptosis.

Magnesium increases ocular blood flow and decreases cytokine and free radical production. Magnesium is required for glutathione production, and it protects neuronal cells in the eye from oxidative stress and apoptosis[

32].

Patients with diabetic retinopathy (DR) have low serum magnesium levels. Those with a severe level of DR had the most prominent hypomagnesemia[

32,

34]. Magnesium has been shown to improve the ocular blood flow in glaucoma patients and may protect the RGC from apoptosis[

32,

33]. Magnesium taurate has been reported to reduce the progression of cataracts.

Selenium Selenium is a trace element incorporated into the endogenous antioxidant enzyme glutathione peroxidase, which is found in high concentrations in the lens, particularly in peripheral lens fiber cells where glutathione is synthesized[

36,

37,

38]. Selenium is a crucial element in regulating oxidative stress in the cornea. Selenium is present in seafoods and cereals. Selenium requirement per day is 200 micrograms. Areas in China, Russia, and parts of Europe have low levels of selenium in soil and selenium deficiency.

Glutathione (GSH) is a vital lens antioxidant. Glutathione functions with several antioxidant systems to decompose ROS including hydrogen peroxide and superoxide into water[

37]. Glutathione depletion induces ferroptosis, autophagy, and premature cell senescence in retinal pigment epithelium cells[

37,

38]. Glutathione can help protect the eye from damage caused by UV light. Glutathione is present in unusually high concentrations in the lens, where it acts as an essential antioxidant, vital for the tissue’s transparency[

37,

38].

Selenium dependent glutathione peroxidase activates the PI3-K AKT pathway in the human lens epithelial cells and inhibits 1-dihydroxy naphthalene-induced apoptosis in the lens epithelium[

36].

Lipoic Acid Alpha lipoic acid (ALA) suppresses free radicals in the eye to prevent protein buildup and cell damage. ALA provides protection to the retina, particularly to the ganglion cells, from ischemia-reperfusion injury and optic nerve crush. ALA and its reduced form, dihydrolipoic acid (DHLA), have powerful antioxidant effects[

39].

Flavonoids Bioflavonoids protect against eye disease[

40]. Flavonoids are naturally present in fruits, vegetables, bark, roots, whole grains, flowers, cocoa, tea, and red wine.

Rutin is a bioflavonoid that protects the eye. Rutin is also known as Vitamin P or rutoside. Rutin has potent antioxidant and anti-inflammatory effects. A rutin-forskolin blend was able to prevent a spike in eye pressure after laser eye surgery.

Quercetin is a particular bioflavonoid that reduces allergic reactions. Flavonoid quercetin has an effect on the stability and function of rhodopsin[

40]. Quercetin is found in a variety of fruits in vegetables, including onions, grapes, berries, cherries, broccoli, and citrus fruits.

Anthocyanins present in bilberries, black currants, and blueberries reduce the risk of cataracts and macular degeneration. Anthocyanins may help reduce the risk of cataracts as well as macular degeneration. Anthocyanins help maintain the health of the cornea and keep the blood vessels in the eye healthy. They improve night vision and protect against glaucoma. Anthocyanins reduce inflammation in the eye and may help diabetic retinopathy[

40].

Coenzyme Q10 (Ubiquinone 10) Coenzyme Q10 plays an important role in the electron transport chain within the mitochondria. It is a lipid-soluble antioxidant that inhibits the oxidation of various biomolecules and plays an important role in anti-inflammation and prevents apoptosis and ferroptosis[

41].

Phenols/Polyphenols

Ginkgo biloba, an antioxidant and polyphenolic flavonoid, has been reported to improve visual field parameters in a double-blinded, placebo-controlled study. Ginkgo biloba protects the mitochondria from oxidative stress[

42].

Superoxide Dismutase (SOD) The Superoxide Dismutase (SOD) family of proteins converts Superoxide into molecular oxygen and hydrogen peroxide to maintain homeostasis. SOD is a ROS-scavenging system. Superoxide Dismutase 1 Nanozyme can be used in the treatment of eye inflammation[

43].

Studies Showing Benefits of Antioxidants

Clinical Trials Testing Impact of Supplements Containing Antioxidants, Minerals, and Trace Elements

The Age-Related Eye Disease Study (AREDS/AREDS II) study led by researchers at the National Eye Institute found that a combination of antioxidants, zinc, and copper reduced the risk of developing advanced AMD by 25% and vision loss by 19%[

44]. The AREDS supplement formula consisted of Vitamin C (500 mg), Vitamin E (400 IU), beta-carotene (15mg), and zinc oxide (80mg). The AREDS II supplement formula consisted of zeaxanthin (2mg), Vitamin C (500mg), Vitamin E (400IU), zinc oxide (80mg or 25mg), and cupric oxide (2mg). Zinc and copper supplementation decreased the risk of developing advanced AMD by 21% and vision loss by 11%. Antioxidants alone decreased the risk of developing advanced AMD by 17% and vision loss by 10%.

Diseases of the Eye Caused by Oxidative Stress, Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS), and Autophagy Imbalances

Lifestyle Changes, Diet-Based Prevention, and Some Non-Pharmacological Interventions Working on the ROS-Autophagy Pathway

Computer Vision Syndrome (CVS) and Digital Eye Syndrome (DES) Computer vision syndrome (CVS) occurs in 50% of computer users. Because a computer screen is generally placed at a higher angle gaze (direct look) compared to the lower angle gaze (look down) required to read from a hard copy of a book held in hand, looking at a visual display terminal leads to increased exposure of the cornea to blue light CVS is characterized by incomplete blinks, which are responsible for the syndrome[

45]. Reduced tear thickness over the lower cornea and asthenopia (eye strain, eye fatigue, burning, discomfort, ache, pain, dryness, foreign body sensation, and tearing) are part of the syndrome. A computer screen reduced symptoms in a study[

46]. Eye strain from overexposure to technology has resulted in an increased risk of eye diseases such as myopia and complications such as retinal tears, cataracts, and macular degeneration[

45].

Blue light may cause damage to the photoreceptors and RPE since it has higher energy. Infants with transparent crystalline lenses and those who are aphakic (people whose lenses have been removed and pseudophakic (people with artificial intraocular lenses) may be at higher risk for blue light syndrome[

47].

Myopia (nearsightedness) Myopia is a refractive error in which people are unable to see distant objects clearly because the image is focused at a point in front of the retina instead of on the retina. It is characterized by increased axial length (AL) of the eye. Myopia is increasing in prevalence due to increased screen time, reduced outdoor play in the evening, excessive reading, and intricate work. Purple light and natural light decrease the incidence of myopia. Oxidative stress may cause altered regulatory pathways in myopia[

48].

Working in daylight, increasing purple light exposure, reducing intricate work, reducing screen time, and wearing proper corrective glasses at the correct distance from the eye reduces the progression of this refractive error.

Research has proposed that oxidative damage plays a role in low myopia (LM) and especially in high myopia (HM) by showing statistically significant differences linked to lipid peroxidation between LM and HM patients, as discussed before.

Glaucomarefers to increased intraocular pressure affecting RGC (retinal ganglion cells), eventually leading to optic nerve damage. ROS can cause damage to the trabecular cells that regulate pressure in the eye. Increased intraocular pressure and the mechanical stretch in trabecular meshwork cells lead to autophagy activation. ROS can also produce retinal ganglion cell (RGC) death. RGCs have long axons with a high density of mitochondria and are more susceptible to autophagy.

Rapamycin plays a protective role in chronic hypertensive glaucoma. Ripacidyl is a ROCK1 inhibitor that enhances intraconal autophagy and promotes axonal protection[

49,

50].

Cataracts Cataract is the clouding of the lens, causing blurry vision and leading to blindness in later stages. Cataracts are common during aging. Cataracts are usually treated with lens replacement surgery[

51].

Accumulation of damaged protein in the lens causes opacities that interfere with vision. UV damage and radiation cause lens opacities. ROS are produced by the endogenous metabolism of glucose in the lens and exogenous mechanisms - from light and radiation.

It is important to control ROS in the lens. Autophagy is important in clearing out the damaged proteins. Protection from UV-A and UV-B damage by protective sunglasses is important in preventing cataract formation.

Antioxidants like ascorbate (Vitamin C) and glutathione are important to control ROS in the lens. Antioxidants that target the mitochondria and eye drops containing N-acetylcarnosine have been shown to prevent and partially reverse cataracts after 3-6 months of topical use[

51].

Diabetic Retinopathy Diabetic retinopathy (DR) is a microvascular disease caused by high glucose levels and glycosylation of the vascular endothelium[

26]. High glucose induces autophagosome formation. Vascular damage by advanced glycation end products leads to cell death.

High glucose leads to sorbitol pathway activation. This sorbitol pathway competes for NADPH, which is required for the recycling of glutathione (ROS-scavenging) systems. In diabetics, antioxidant systems cannot keep up with ROS damage. High glucose-induced inflammatory response and increased ROS in the retinal pigment epithelium (RPE)[

52,

53].

Dry DR is due to a lack of blood flow/microinfarct of the retinal cells, which appear as paper white areas in the retina. Wet DR is caused by neovascularization and retinal hemorrhage (leaking of blood into the retina). This proliferative retinopathy interferes with vision. The mTOR inhibitor rapamycin decreases the high glucose-induced inflammatory response and ROS in the RPE.

Temsirolimus (which is in the kinase inhibitor class of drugs) acts by blocking the abnormal proteins that instruct cancer cells to multiply. In the eye, temsirolimus inhibits RPE and endothelial cell proliferation and migration and decreases vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and Derived Growth factor PDGF expression in DR.

Age-Related Macular Degeneration Age-Related Macular Degeneration (AMD) is a progressive disease of the retina. Late-stage AMD leads to loss of central vision and blindness[

54]. AMD affects the macula, the yellow-colored area in the retina responsible for central vision.

In AMD, there is oxidative damage to the retinal pigment epithelium (RPE), with thickening and calcification of the RPE. There is ROS-induced cell death. Dysfunctional autophagy contributes to the pathogenesis of AMD[

54].

Rapamycin inhibits mTOR1 signaling, thereby preventing AMD-related aging of RPE cells. Temsirolimus inhibits RPE and endothelial cell proliferation and migration and decreases VEGF and PDGF expression in AMD.

Participants in the AREDS study took 500 mg of Vitamin C daily in combination with beta-carotene, Vitamin E, and zinc. In these patients, the progression of AMD decreased by 25%, and vision loss slowed by 19%[

44].

Optic Nerve Crush Injury causes problems in vision. Blunt trauma can cause optic nerve injury. Increased ROS triggers autophagy in the retinal ganglion cells (RGC), Muller cells, and the primary visual cortex. Pharmacological induction of autophagy by rapamycin promotes RGC survival in optic nerve crush injury.

Gliomas of the Optic Nerve Autophagy is important in helping tumors grow by disposing of damaged proteins and feeding tumors with released metabolites.

Autophagy-induced cell death can limit cancer growth. ROS at low levels can help tumor growth, but at high levels can limit cancer growth and metastasis.

Some Simple Interventions for the Prevention of Vision and Ocular Diseases

Primary prevention includes maintaining proper, balanced nutrition with a diet rich in natural antioxidants, minerals, and trace elements. Additionally, prevention includes using supplements containing vitamins, minerals, antioxidants, and trace elements after discussing with a physician. eye protection with UV-A/UV-B blocking sunglasses. Blue light glasses help to avoid excessive blue light exposure from computer screens, in addition to reducing computer/handheld screen time to recommended levels, especially in school-age children. Also, using eye exercises can decrease eye strain, especially following the 20-20-20 rule of focusing on a spot 20 feet away for 20 seconds for every 20 minutes of screen time. Topical prevention includes artificial tears for dry eye prevention, antioxidant drops for environmental exposure and glutathione drops for eye inflammation. Natural antioxidants, supplements, and various medications that act on ROS and autophagy have been discussed in the disease section.

Standard Medical and Surgical Treatments: Standard medical therapies and surgical treatments have not been discussed in this article as they are outside the scope of this article.

Conclusion

Relevance/Importance of Work:

The National Eye Institute estimates that vision loss, eye diseases, and vision disorders in the US cost

$139 billion. Viable preventions and treatments can reduce this enormous economic burden[

55]. Eye disease prevalence is increasing due to increased screen time, digitization of society, increasing lifespan, harmful sunlight exposure, and poor dietary choices. Myopia is considered an epidemic in certain countries. Increasing life span contributes to many cases of cumulative damage from the sun and environmental exposures.

Lifestyle modification, including adequate protection from UV-A and UV-B light exposure with proper sunglasses, computer glasses, proper screen placement of computer monitors for glare prevention, the 20-20-20 rule, and a balanced diet with adequate antioxidants will be beneficial to all.

Antioxidant supplements and early screening and correction of refractive errors, amblyopia, and early screening for diabetes, hypertension, and glaucoma in high-risk individuals will help in early identification and prevent the progression of the disease.

Educational campaigns aimed at parents, students, and at-risk individuals to reduce screen time to recommended levels are critical. The need is acute for school-aged children when the eye is still growing. Government measures must increase accessibility to fresh green vegetables and fruits containing the necessary quantity of antioxidants for people in all parts of the society, especially in inner-city food deserts that lack access to nutritious foods[

56]. Recently, the US Department of Agriculture (USDA) has increased funding by

$155 million for the Healthy Food Financing Initiative, which benefits communities by offering grants and loans to entities that offer healthy food to individuals in food deserts[

57].

A randomized control trial with an antioxidant diet, personal protective devices, computer blue screen filters, and reduced screen time in a large study group consisting of male and female subjects in different age groups in the United States, measuring axial length, refractive error, intraocular pressure, retinal scans, visual acuity, color vision, visual field, astigmatism, presence and absence of diabetic retinopathy, age-related macular degeneration, gliomas, and retinoblastoma, can shed light on the role of these interventions in decreasing or delaying the onset of eye diseases and the identifying the age at which these measures are most effective. The results of this type of study will be relevant to the current digital lifestyle and can lead to a much reduction in morbidity and disability associated with eye diseases.

References

- Garin M. Eye Anatomy: How do our eyes work? EyeHealthWeb.com. https://www.eyehealthweb.com/eye-anatomy/. Published September 28, 2015.

- The Brain from Top to Bottom. McGill University. https://thebrain.mcgill.ca/flash/d/d_02/d_02_m/d_02_m_vis/d_02_m_vis.html.

- Ohsugi H, Ikuno Y, Shoujou T, Oshima K, Ohsugi E, Tabuchi H. Axial length changes in highly myopic eyes and influence of myopic macular complications in Japanese adults. PLoS One. 2017;12(7):e0180851. Published 2017 July 7. [CrossRef]

- Carr BJ, Stell WK. The Science Behind Myopia. In: Kolb H, Fernandez E, Nelson R, eds. Webvision: The Organization of the Retina and Visual System. Salt Lake City (UT): University of Utah Health Sciences Center; November 7, 2017.

- Blehm C, Vishnu S, Khattak A, Mitra S, Yee RW. Computer vision syndrome: a review. Surv Ophthalmol. 2005;50(3):253-262. [CrossRef]

- Barbas-Bernardos C, Armitage EG, García A, Mérida S, Navea A, Bosch-Morell F, Barbas C. Looking into aqueous humor through metabolomics spectacles-exploring its metabolic characteristics in relation to myopia. J Pharm Biomed Anal. 2016;127:18–25.

- Costanza MA. Visual and ocular symptoms related to the use of video display terminals. J Behav Optom. 1994;5:31–6.

- Mérida S, Villar VM, Navea A, et al. Imbalance between oxidative stress and growth factors in human high myopia. Frontiers. Published April 16, 2020. [CrossRef]

- Rosenfield, Mark. (2016). Computer vision syndrome (a.k.a. digital eye strain). Optometry in practice. 17. 1-10.

- National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine; Health and Medicine Division; Board on Population Health and Public Health Practice; Committee on Public Health Approaches to Reduce Vision Impairment and Promote Eye Health; Welp A, Woodbury RB, McCoy MA, et al., editors. Making Eye Health a Population Health Imperative: Vision for Tomorrow. Washington (DC): National Academies Press (US); 2016 September 15. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK385157/?report=classic. [CrossRef]

- Vision Health Initiative. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/visionhealth/resources/features/vision-health-children.html. Published February 24, 2023.

- To grow up healthy, children need to sit less and play more. World Health Organization. https://www.who.int/news/item/24-04-2019-to-grow-up-healthy-children-need-to-sit-less-and-play-more.

- Hedderson MM, Bekelman TA, Li M, et al. Trends in Screen Time Use Among Children During the COVID-19 Pandemic, July 2019 Through August 2021. JAMA Network Open. 2023;6(2):e2256157. [CrossRef]

- Wang J, Li Y, Musch DC, et al. Progression of Myopia in School-Aged Children After COVID-19 Home Confinement. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2021;139(3):293–300. [CrossRef]

- Sliney DH. How light reaches the eye and its components. Int J Toxicol. 2002;21(6):501-509. [CrossRef]

- Murphy MP. How mitochondria produce reactive oxygen species. Biochem J. 2009;417(1):1–13.

- Nita M, Grzybowski A. The Role of the Reactive Oxygen Species and Oxidative Stress in the Pathomechanism of the Age-Related Ocular Diseases and Other Pathologies of the Anterior and Posterior Eye Segments in Adults. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2016;2016:3164734. [CrossRef]

- Tao JX, Zhou WC, Zhu XG. Mitochondria as Potential Targets and Initiators of the Blue Light Hazard to the Retina. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2019;2019:6435364. Published 2019 Aug 21. [CrossRef]

- Jager TL, Cockrell AE, Du Plessis SS. Ultraviolet Light Induced Generation of Reactive Oxygen Species. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2017;996:15-23. [CrossRef]

- Chang, KC., Liu, PF., Chang, CH. et al. The interplay of autophagy and oxidative stress in the pathogenesis and therapy of retinal degenerative diseases. Cell Biosci 12, 1 (2022). [CrossRef]

- He C, Klionsky DJ. Regulation mechanisms and signaling pathways of autophagy. Annu Rev Genet. 2009;43:67-93. [CrossRef]

- Shadel GS, Horvath TL. Mitochondrial ROS signaling in organismal homeostasis. Cell. 2015;163(3):560–9. 50.

- Schrader M, Fahimi HD. Peroxisomes and oxidative stress. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2006;1763(12):1755–66.

- Pizzino G, Irrera N, Cucinotta M, Pallio G, Mannino F, Arcoraci V, Squad- rito F, Altavilla D, Bitto A. Oxidative stress: harms and benefits for human health. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2017;2017:8416763.

- Ung L, Pattamatta U, Carnt N, Wilkinson-Berka JL, Liew G, White AJR. Oxidative stress and reactive oxygen species: a review of their role in ocular disease. Clin Sci (Lond). 2017;131(24):2865–83.

- Incalza MA, D’Oria R, Natalicchio A, Perrini S, Laviola L, Giorgino F. Oxidative stress and reactive oxygen species in endothelial dysfunction associated with cardiovascular and metabolic diseases. Vascul Pharmacol. 2018;100:1–19.

- Lim JC, Caballero Arredondo M, Braakhuis AJ, Donaldson PJ. Vitamin C and the Lens: New Insights into Delaying the Onset of Cataract. Nutrients. 2020;12(10):3142. Published 2020 Oct 14. [CrossRef]

- Antioxidants. The Nutrition Source. https://www.hsph.harvard.edu/nutritionsource/antioxidants/. Published March 3, 2021.

- Rasmussen HM, Johnson EJ. Nutrients for the aging eye. Clin Interv Aging. 2013;8:741-748. [CrossRef]

- Scripsema NK, Hu DN, Rosen RB. Lutein, Zeaxanthin, and Meso-Zeaxanthin in the Clinical Management of Eye Disease. J Ophthalmol. 2015;2015:865179. [CrossRef]

- Abdel-Aal el-SM, Akhtar H, Zaheer K, Ali R. Dietary sources of lutein and zeaxanthin carotenoids and their role in eye health. Nutrients. 2013;5(4):1169-1185. Published 2013 Apr 9. [CrossRef]

- Zheltova AA, Kharitonova MV, Iezhitsa IN, Spasov AA. Magnesium deficiency and oxidative stress: an update. Biomedicine (Taipei). 2016;6(4):20. [CrossRef]

- Ajith TA. Possible therapeutic effect of magnesium in ocular diseases. J Basic Clin Physiol Pharmacol. 2019;31(2):/j/jbcpp.2020.31.issue-2/jbcpp-2019-0107/jbcpp-2019-0107.xml. Published 2019 Nov 14. [CrossRef]

- P McNair, C Christiansen, S Madsbad, E Lauritzen, O Faber, C Binder, I Transbøl; Hypomagnesemia, a Risk Factor in Diabetic Retinopathy. Diabetes 1 November 1978; 27 (11): 1075–1077. [CrossRef]

- Ekici F, Korkmaz Ş, Karaca EE, et al. The Role of Magnesium in the Pathogenesis and Treatment of Glaucoma. Int Sch Res Notices. 2014;2014:745439. Published 2014 Oct 13. [CrossRef]

- Zhu X, Guo K, Lu Y. Selenium effectively inhibits 1,2-dihydroxynaphthalene-induced apoptosis in human lens epithelial cells through activation of PI3-K/Akt pathway. Molecular Vision. 2011. PMID: 21850177; PMCID: PMC3154130.

- Giblin FJ. Glutathione: a vital lens antioxidant. J Ocul Pharmacol Ther. 2000;16(2):121-135. [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y., Zheng, Y., Wang, C. et al. Glutathione depletion induces ferroptosis, autophagy, and premature cell senescence in retinal pigment epithelial cells. Cell Death Dis 9, 753 (2018). [CrossRef]

- Ajith TA. Alpha-lipoic acid: A possible pharmacological agent for treating dry eye disease and retinopathy in diabetes. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol. 2020;47(12):1883-1890. [CrossRef]

- Davinelli S, Ali S, Scapagnini G, Costagliola C. Effects of Flavonoid Supplementation on Common Eye Disorders: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Clinical Trials. Front Nutr. 2021;8:651441. Published

2021 May 25. [CrossRef]

- Zhang X, Tohari AM, Marcheggiani F, et al. Therapeutic Potential of Co-enzyme Q10 in Retinal Diseases. Curr Med Chem. 2017;24(39):4329-4339. [CrossRef]

- Kalt W, Hanneken A, Milbury P, Tremblay F. Recent research on polyphenolics in vision and eye health. J Agric Food Chem. 2010;58(7):4001-4007. [CrossRef]

- Kost OA, Beznos OV, Davydova NG, et al. Superoxide Dismutase 1 Nanozyme for Treatment of Eye Inflammation. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2015;2015:5194239. [CrossRef]

- Age-Related Eye Disease Study Research Group. A randomized, placebo-controlled, clinical trial of high-dose supplementation with vitamins C and E, beta carotene, and zinc for age-related macular degeneration and vision loss: AREDS report no. 8 [published correction appears in Arch Ophthalmol. 2008 Sep;126(9):1251]. Arch Ophthalmol. 2001;119(10):1417-1436. | AREDS/AREDS2 Clinical Trials. National Eye Institute. https://www.nei.nih.gov/research/clinical-trials/age-related-eye-disease-studies-aredsareds2/about-areds-and-areds2. [CrossRef]

- McMonnies CW. Incomplete blinking: exposure keratopathy, lid wiper epitheliopathy, dry eye, refractive surgery, and dry contact lenses. Cont Lens Anterior Eye. 2007;30(1):37-51. [CrossRef]

- Miyake-Kashima M, Dogru M, Nojima T, Murase M, Matsumoto Y, Tsubota K. The effect of antireflection film use on blink rate and asthenopic symptoms during visual display terminal work. Cornea. 2005;24(5):567-570. [CrossRef]

- Lanca, C., & Saw, S. M. (2020). The Association Between Digital Screen Time and Myopia: A Systematic Review. Ophthalmic and Physiological Optics, 40(2), 216–229. [CrossRef]

- Francisco, Bosch-Morell, et al. “Oxidative stress in myopia.” Oxidative medicine and cellular longevity vol. 2015 (2015): 750637. [CrossRef]

- Hamano T, Shirafuji N, Yen SH, Yoshida H, Kanaan NM, Hayashi K, Ikawa M, Yamamura O, Fujita Y, Kuriyama M, et al. Rho-kinase ROCK inhibitors reduce oligomeric tau protein. Neurobiol Aging. 2020;89:41–54.

- Kitaoka Y, Sase K, Tsukahara C, Kojima K, Shiono A, Kogo J, Tokuda N, Takagi H. Axonal protection by ripasudil, a rho kinase inhibitor, via modulating autophagy in TNF-induced optic nerve degeneration. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2017;58(12):5056–64.

- Babizhayev, Mark A. “Generation of reactive oxygen species in the anterior eye segment. Synergistic codrugs of N-acetylcarnosine lubricant eye drops and mitochondria-targeted antioxidant act as a powerful therapeutic platform for the treatment of cataracts and primary open-angle glaucoma.” BBA clinical vol. 6 49-68. April 19. 2016. [CrossRef]

- Roberts DJ, Tan-Sah VP, Ding EY, Smith JM, Miyamoto S. Hexokinase-II positively regulates glucose starvation-induced autophagy through TORC1 inhibition. Mol Cell. 2014;53(4):521–33.

- Ulker E, Parker WH, Raj A, Qu ZC, May JM. Ascorbic acid prevents VEGF-induced increases in endothelial barrier permeability. Mol Cell Biochem. 2016;412(1-2):73-79. [CrossRef]

- Golestaneh N, Chu Y, Xiao YY, Stoleru GL, Theos AC. Dysfunctional autophagy in RPE, a contributing factor in age-related macular degeneration. Cell Death Dis. 2017;8(1):e2537.

-

Eye Disease Statistics Fact Sheet - National Institutes of Health. (n.d.). Retrieved from https://www.nei.nih.gov/sites/default/files/2019-04/NEI_Eye_Disease_Statistics_Factsheet_2014_V10.pdf.

- Lawrenson JG, Downie LE. Nutrition and Eye Health. Nutrients. 2019;11(9):2123. Published 2019 Sep 6. [CrossRef]

- USDA announces framework for shoring up the food supply chain and transforming the food system to be fairer, more competitive, more resilient. Food and Nutrition Service U.S. Department of Agriculture. https://www.fns.usda.gov/news-item/usda-0116.22. Published June 1, 2022.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).