Submitted:

06 April 2023

Posted:

07 April 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Definitions of Key Concepts

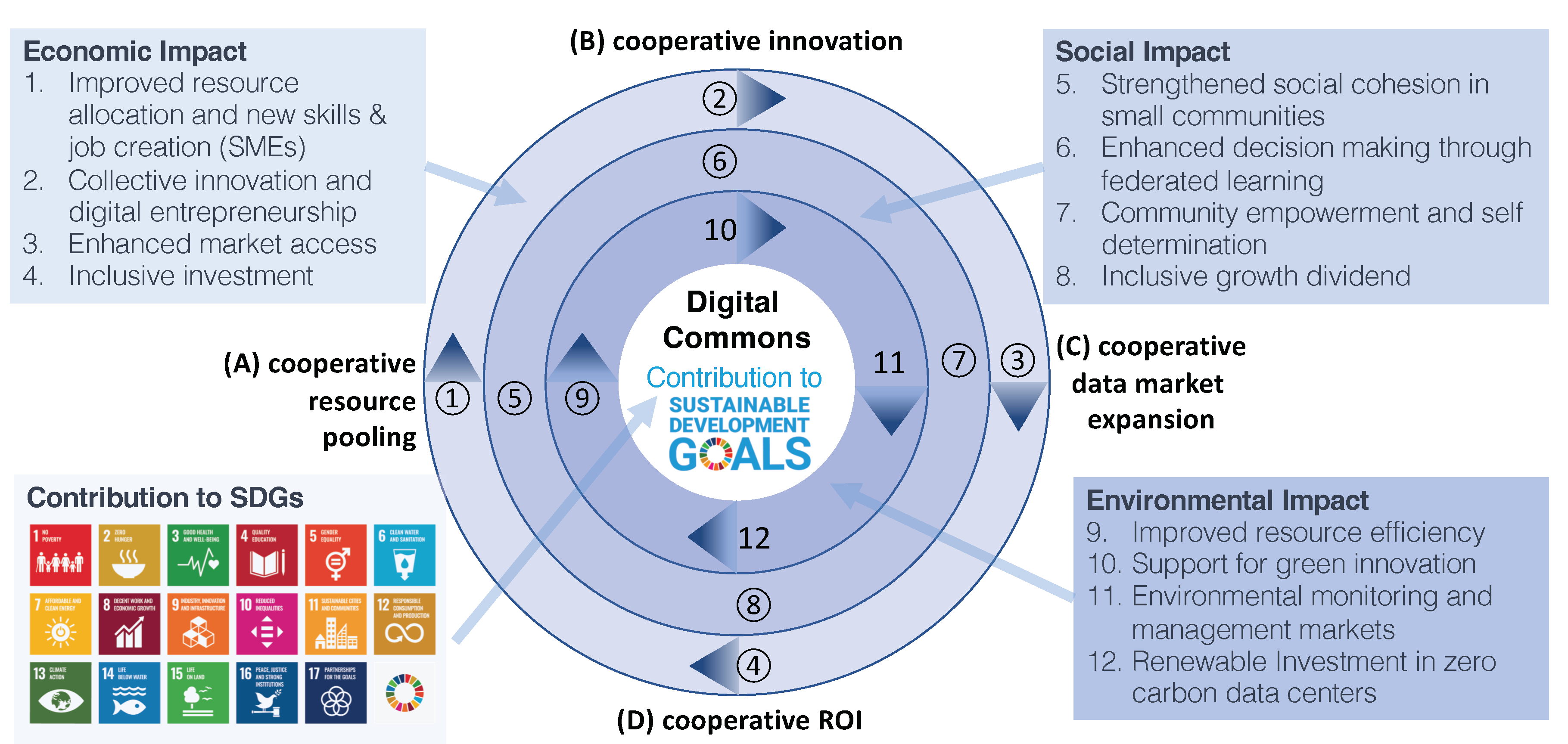

2. Economic, Social and Environmental Impact of Our Proposal

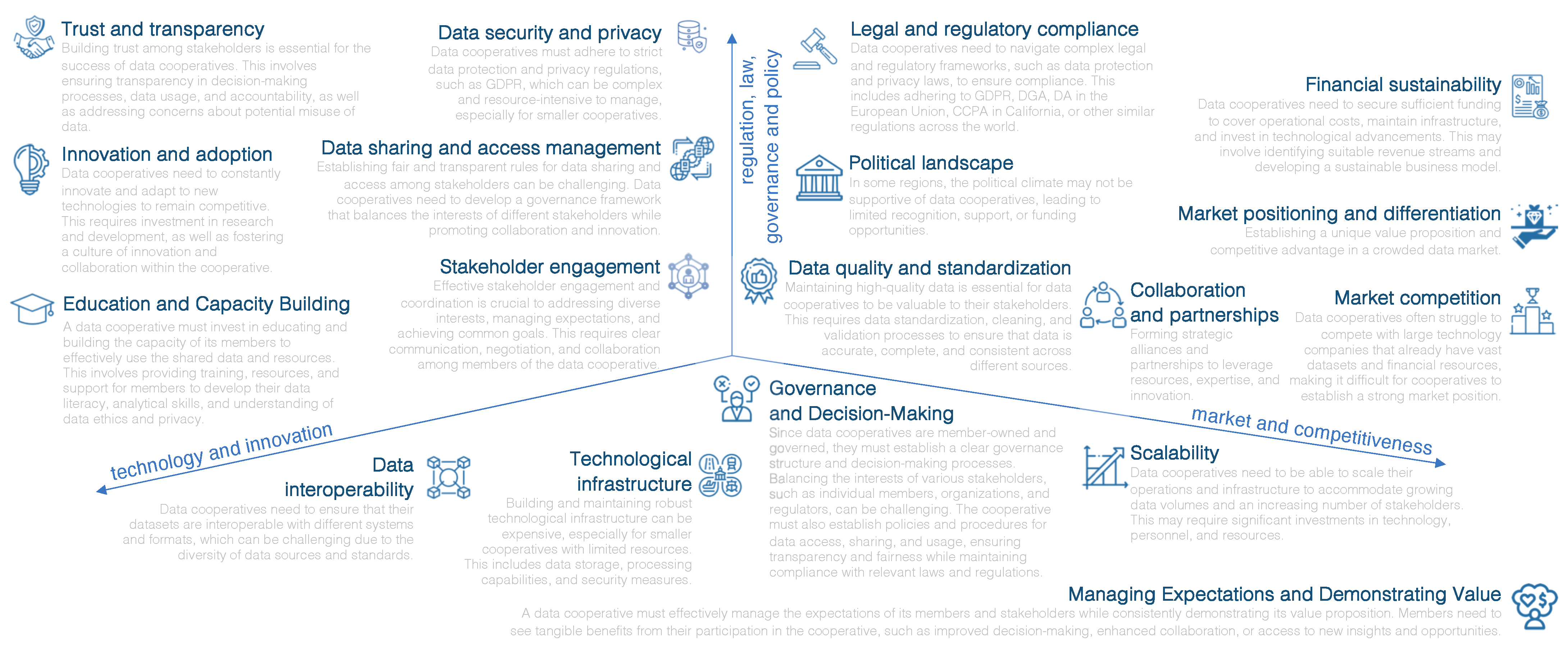

3. Challenges That Must Be Overcome

4. A Path to Transformation – 10 Case Studies

- Regulatory Barriers: Existing regulations in many countries may not adequately support or even hinder the establishment and operation of data cooperatives and digital federation platforms, limiting their potential impact.

- Limited Resources: Small communities and SMEs often face resource constraints that restrict their ability to develop and implement digital governance structures, open standards, and cooperative models.

- Digital Divide: Unequal access to digital infrastructure, skills, and resources exacerbates existing inequalities, making it more challenging for marginalized communities to participate in and benefit from digital transformation efforts.

- Data Privacy and Security: Ensuring data privacy and security is critical for the success of digital federation platforms and data cooperatives, requiring the development of robust governance frameworks and technical solutions.

5. Recommendations for Implementation

6. Governments’ Role and Beyond

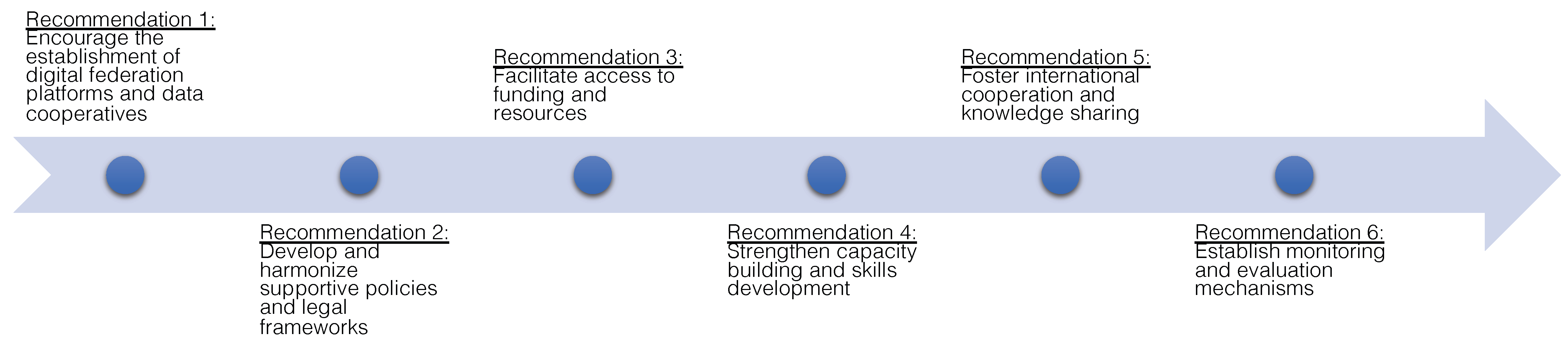

| Recommendation | Description |

|---|---|

| Policy Harmonization | Encourage member countries to develop and align policies that promote digital inclusion, support the establishment of data cooperatives, and foster a more equitable digital economy. This can include measures such as incentives for SMEs to participate in cooperatives and the adoption of open standards and APIs. |

| Financial Support | Facilitate access to funding for the development and implementation of digital federation platforms and data cooperatives, particularly in regions where resources are scarce. This can include grants, low-interest loans, or other financial instruments that help kickstart these initiatives. |

| Capacity Building | Support capacity building and skills development programs for small communities and SMEs, empowering them to participate in the digital economy and make effective use of digital resources. This may involve collaborating with international organizations, educational institutions, NGOs and the private sector to develop and deliver relevant training programs. This could include using the existing knowledge in established and flagship co-operative groups (i.e. Mondragon [99]) to leverage through this organizational model further implementations in the current digital economy and society. |

| Knowledge Sharing | Promote knowledge sharing and the exchange of best practices among member countries regarding the implementation of digital federation platforms and data cooperatives. This can help identify effective models and strategies that can be adapted and scaled across different contexts. |

| International Cooperation | Foster international cooperation and partnerships to support the development of digital federation platforms and data cooperatives, including collaboration with multilateral organizations, regional development banks, and other stakeholders. |

| Monitoring and Evaluation | Establish mechanisms for monitoring and evaluating the impact of digital federation platforms and data cooperatives on small communities and SMEs. This can help to identify areas for improvement and ensure that these initiatives are effectively contributing to the achievement of SDGs 8, 9, and 11. |

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | Whereas data trusts are a different data stewardship model to a data cooperative. The trust model is based on a board of trustees who have a fiduciary duty towards data subjects and aren't necessarily controlled directly be them. Whereas data cooperatives have stronger democratic governance and data decisions are made either by the cooperative members themselves or officers that are employed by the members to act on their behalf. |

| 2 | In the context of data cooperatives, 'democratic' governance emphasizes the representational power of the cooperative, empowering traditionally underrepresented or misrepresented individuals in the digital space by providing them with a self-determined voice and equitable participation in decision-making processes. |

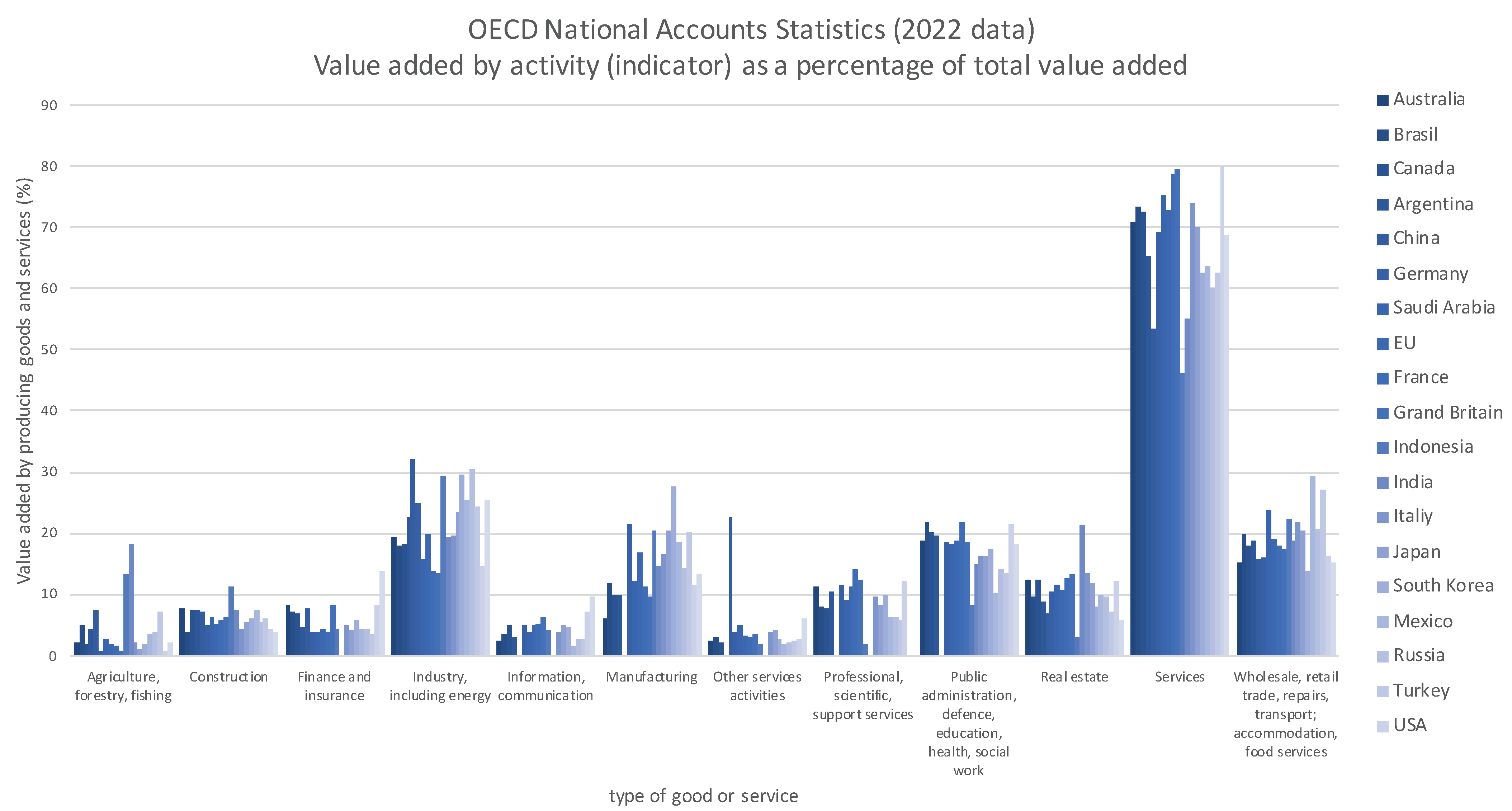

| 3 | Value added by activity shows the value added created by the various industries (such as agriculture, industry, utilities, and other service activities). The indicator presents value added for an activity, as a percentage of total value added. All OECD countries compile their data according to the 2008 System of National Accounts (SNA). |

References

- Bühler, M.M.; Nübel, K.; Jelinek, T.; Riechert, D.; Bauer, T.; Schmid, T.; Schneider, M. Data cooperatives as a catalyst for collaboration, data sharing and the digital transformation of the construction sector. Buildings 2023, 13, 442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tait, J. Open Data Cooperation — Building a data cooperative. Available online: https://www.opendatamanchester.org.uk/947/ (accessed on 4 April 2023s).

- Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). Data-driven innovation: Big data for growth and well-being; OECD Publishing: 2015.

- Corrado, C.; Hulten, C.; Sichel, D. Intangible capital and US economic growth. Review of income and wealth 2009, 55, 661–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bresciani, S.; Ciampi, F.; Meli, F.; Ferraris, A. Using big data for co-innovation processes: Mapping the field of data-driven innovation, proposing theoretical developments and providing a research agenda. International Journal of Information Management 2021, 60, 102347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hummel, P.; Braun, M.; Tretter, M.; Dabrock, P. Data sovereignty: A review. Big Data & Society 2021, 8, 2053951720982012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jarke, M.; Otto, B.; Ram, S. Data sovereignty and data space ecosystems. 2019, 61, 549-550.

- Institute, A.L. Exploring legal mechanisms for data stewardship. Ada Lovelace Institute and UK AI Council 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Calzada, I. Data co-operatives through data sovereignty. Smart Cities 2021, 4, 1158–1172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuno, S.; Bruns, L.; Tcholtchev, N.; Lämmel, P.; Schieferdecker, I. Data governance and sovereignty in urban data spaces based on standardized ICT reference architectures. Data 2019, 4, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Floridi, L. The Fight for Digital Sovereignty: What It Is, and Why It Matters, Especially for the EU. Philosophy & Technology 2020, 33, 369–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jelinek, T. Technology Silos of Today or the End of Global Innovation. In The Digital Sovereignty Trap; Springer: 2023; pp. 19-33.

- Walter, M.; Kukutai, T.; Carroll, S.R.; Rodriguez-Lonebear, D. Indigenous data sovereignty and policy; Taylor & Francis: 2021.

- Bühler, M.; Jelinek, T.; Nübel, K.; Anderson, N.; Ballard, G.; Bew, M.; Bowcott, D.; Broek, K.; Buziek, G.; Cane, I.; et al. A new vision for infratech: governance and value network integration through federated data spaces and advanced infrastructure services for a resilient and sustainable future. In Policy brief; 2021; p. 27.

- Krüger, J. Entwicklung von Anwendungsfällen aus dem Bereich Bauwirtschaft für offene, föderierte digitale Plattformen (Development of use cases from the construction industry for open, federated digital platforms). Master Thesis, University of Applied Sciences Konstanz (HTWG), https://www.htwg-konstanz.de/hochschule/personen/michael-buehler/lehre-abschlussarbeiten/, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Nübel, K.; Bühler, M.M.; Jelinek, T. Federated Digital Platforms: Value Chain Integration for Sustainable Infrastructure Planning and Delivery. Sustainability 2021, 13, 8996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chase, J.S.; Baldin, I. Federated authorization for managed data sharing: Experiences from the ImPACT project. In Proceedings of the 2021 International Conference on Computer Communications and Networks (ICCCN); 2021; pp. 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Gaia-X. Gaia-X: A Federated Secure Data Infrastructure. Available online: https://www.gaia-x.eu/ (accessed on August 29).

- Koshizuka, N.; Mano, H. DATA-EX: Infrastructure for Cross-Domain Data Exchange Based on Federated Architecture. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE International Conference on Big Data (Big Data); 2022; pp. 6145–6152. [Google Scholar]

- Liaqat, M.; Chang, V.; Gani, A.; Ab Hamid, S.H.; Toseef, M.; Shoaib, U.; Ali, R.L. Federated cloud resource management: Review and discussion. Journal of Network and Computer Applications 2017, 77, 87–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oraskari, J.; Schulz, O.; Werbrouck, J.; Beetz, J. Enabling Federated Interoperable Issue Management in a Building and Construction Sector. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 29th EG-ICE International Workshop on Intelligent Computing in Engineering; 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Vernet Sancho, M. Creation of an open data federated platform. Universitat Politècnica de Catalunya, 2022.

- Werbrouck, J.; Pauwels, P.; Beetz, J.; Mannens, E. Data patterns for the organisation of federated linked building data. In Proceedings of the LDAC2021, 2021, the 9th Linked Data in Architecture and Construction Workshop; pp. 1–12.

- Wu, C.; Wu, F.; Qi, T.; Wang, Y.; Huang, Y.; Xie, X. Game of Privacy: Towards Better Federated Platform Collaboration under Privacy Restriction. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2202.05139. [Google Scholar]

- Baars, H.; Tank, A.; Weber, P.; Kemper, H.-G.; Lasi, H.; Pedell, B. Cooperative Approaches to Data Sharing and Analysis for Industrial Internet of Things Ecosystems. Applied Sciences 2021, 11, 7547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferdinand-Steinbeis-Institut (FSTI). Datengenossenschaft.com (data cooperative). Available online: https://www.datengenossenschaft.com/ (accessed on 14 November 2022).

- Miller, K. Radical Proposal: Data Cooperatives Could Give Us More Power Over Our Data. Available online: https://hai.stanford.edu/news/radical-proposal-data-cooperatives-could-give-us-more-power-over-our-data (accessed on 14 November 2022).

- Scholz, T.R.; Calzada, I. Data cooperatives for pandemic times. In Proceedings of the Scholz, T. & Calzada, Data Cooperatives for Pandemic Times. Public Seminar journal. DOI, 2021., I.(2021). [Google Scholar]

- Tait, J. The Case for Data Cooperatives. Whitepaper Series 2021, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Calzada, I. Postpandemic technopolitical democracy: Algorithmic nations, data sovereignty, digital rights, and data cooperatives. In Made-to-Measure Future (s) for Democracy? Views from the Basque atalaia; Springer International Publishing Cham: 2022; pp. 97-117.

- Hardjono, T.; Pentland, A. Empowering artists, songwriters & musicians in a data cooperative through blockchains and smart contracts. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1911.10433. [Google Scholar]

- Hardjono, T.; Pentland, A. Data cooperatives: Towards a foundation for decentralized personal data management. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1905.08819. [Google Scholar]

- Marjanovic, O.; Zhu, J.; Krivokapic-Skoko, B.; Lewis, C. Will the real data coop stand up!: Data cooperatives in the coop sector–current challenges and future opportunities. In Proceedings of the 14th ICA CCR Asia-Pacific Research Conference; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Salau, A.; Dantu, R.; Morozov, K.; Upadhyay, K.; Badruddoja, S. Towards a Threat Model and Security Analysis for Data Cooperatives. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 19th International Conference on Security and Cryptography-SECRYPT, 2022; pp. 707–713.

- Shah, P.R.; Juenke, E.G.; Fraga, B.L. Here Comes Everybody: Using a Data Cooperative to Understand the New Dynamics of Representation. PS: Political Science & Politics 2022, 55, 300–302. [Google Scholar]

- Mannan, M.; Schneider, N. Exit to community: Strategies for multi-stakeholder ownership in the platform economy. Geo. L. Tech. Rev. 2021, 5, 1. [Google Scholar]

- Mannan, M. Theorizing the emergence of platform cooperativism: drawing lessons from role-set theory. Ondernemingsrecht Tijdschrift 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Mannan, M.; Pek, S. Solidarity in the sharing economy: The role of platform cooperatives at the base of the pyramid; Springer: 2021.

- Bunders, D.J.; Arets, M.; Frenken, K.; De Moor, T. The feasibility of platform cooperatives in the gig economy. Journal of Co-operative Organization and Management 2022, 10, 100167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuncoro, E.A.; SE, M. Platform Cooperative as a Business Model: An Innovation toward a Fair Sharing Economy in Indonesia. 2022.

- Pentzien, J. The Politics of Platform Cooperativism. Institute for Digital Cooperative Economy. https://ia801701. us. archive. org/10/items/jonas-pentziensingle-web_202012/Jonas% 20Pentzien_single_web. pdf.

- Consortium, P.C. Platform Co-op Directory. 2021.

- Scholz, T. Platform cooperativism. Challenging the corporate sharing economy. New York, NY: Rosa Luxemburg Foundation.

- Scholz, T. A Portfolio of Platform Cooperativism, in Progress. Ökologisches Wirtschaften-Fachzeitschrift.

- Calzada, I. Platform and data co-operatives amidst European pandemic citizenship. Sustainability 2020, 12, 8309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, A.; Bradley, H.; Rajkumar, N. Reclaiming the Digital Commons: A Public Data Trust for Training Data. arXiv preprint arXiv:2303.09001, arXiv:2303.09001 2023.

- Dulong de Rosnay, M.; Stalder, F. Digital commons. Internet Policy Review 2020, 9, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, S.; Siddarth, D. Generative AI and the Digital Commons. arXiv preprint arXiv:2303.11074, arXiv:2303.11074 2023.

- Ostrom, E. Governing the commons: The evolution of institutions for collective action; Cambridge university press: 1990.

- Sharma, C. Tragedy of the Digital Commons. North Carolina Law Review, Forthcoming.

- Siddarth, D.E.G.W. The case for the digital commons. 2021.

- Walljasper, J. Elinor Ostrom's 8 Principles for Managing A Commons. On the Commons 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Bechtold, S. Vom Urheber-zum Informationsrecht: Implikationen des Digital Rights Management; Beck München: 2002.

- Calzada, I. The right to have digital rights in smart cities. Sustainability 2021, 13, 11438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calzada, I.; Almirall, E. Data ecosystems for protecting European citizens’ digital rights. Transforming Government: People, Process and Policy 2020, 14, 133–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calzada, I.; Pérez-Batlle, M.; Batlle-Montserrat, J. People-centered smart cities: An exploratory action research on the cities’ coalition for digital rights. Journal of Urban Affairs 2021, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monti, A. The Digital Rights Delusion: Humans, Machines and the Technology of Information; Taylor & Francis: 2023.

- Pangrazio, L.; Sefton-Green, J. Digital rights, digital citizenship and digital literacy: What’s the difference? NAER: Journal of New Approaches in Educational Research 2021, 10, 15–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- POLONA, C. Digital rights and principles. 2023.

- Lim, Y. Tech Wars: Return of the Conglomerate-Throwback or Dawn of a New Series for Competition in the Digital Era. J. Korean L. 2020, 19, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). Mapping approaches to data and data flows; OECD: Paris, France, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Reimsbach-Kounatze, C. Enhancing access to and sharing of data: Striking the balance between openness and control over data. In Proceedings of the Data Access, Consumer Interests and Public Welfare; 2021; pp. 25–68. [Google Scholar]

- Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). OECD Digital Economy Outlook 2020; OECD: Paris, France, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 64. Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). Enhancing Access to and Sharing of Data.

- Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). Responding to societal challenges with data: Access, sharing, stewardship and control. OECD Digital Economy Papers, OECD Publishing, Paris, France 2022, 342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- 66. Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). Value added by activity (indicator). National Accounts at a Glance. [CrossRef]

- Jack, W.; Suri, T. Mobile money: The economics of M-PESA; National Bureau of Economic Research: 2011.

- Kingiri, A.N.; Fu, X. Understanding the diffusion and adoption of digital finance innovation in emerging economies: M-Pesa money mobile transfer service in Kenya. Innovation and Development 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mbiti, I.; Weil, D.N. Mobile banking: The impact of M-Pesa in Kenya. In African successes, Volume III: Modernization and development; University of Chicago Press: 2015; pp. 247-293.

- Omwansa, T. M-PESA: Progress and prospects. Innovations 2009, 107. [Google Scholar]

- Van Hove, L.; Dubus, A. M-PESA and financial inclusion in Kenya: of paying comes saving? Sustainability 2019, 11, 568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubé, L.; McRae, C.; Wu, Y.-H.; Ghosh, S.; Allen, S.; Ross, D.; Ray, S.; Joshi, P.K.; McDermott, J.; Jha, S. Impact of the eKutir ICT-enabled social enterprise and its distributed micro-entrepreneur strategy on fruit and vegetable consumption: A quasi-experimental study in rural and urban communities in Odisha, India. Food Policy 2020, 90, 101787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McRae, C.; Annosi, M.; Dubé, L. Tracing Digital Transformation Pathways from Subsistence Farming to Equitable and Sustainable Modern Society: Revisiting the eKutir ICT Platform-Enabled Ecosystem as an Interstitial Space. 2022.

- Moore, S.; Annosi, M.C.; Gilissen, T.; Mandelbaum, J.; Dube, L. The social impact of ICT-enabled interventions among rural Indian farmers as seen through eKutir’s VeggieLite intervention. In How is Digitalization Aff ecting Agri-food?; Routledge: 2020; pp. 93-98.

- Sengupta, T.; Narayanamurthy, G.; Hota, P.K.; Sarker, T.; Dey, S. Conditional acceptance of digitized business model innovation at the BoP: A stakeholder analysis of eKutir in India. Technological Forecasting and Social Change 2021, 170, 120857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senyo, W. Farmerline: a for-profit agtech company with a social Mission. In Digital technologies for agricultural and rural development in the global south; CAB International Wallingford UK: 2018; pp. 123-126.

- Delinthe, L.; Zwart, S.J. Digital Services for Agriculture. 2022.

- Agnihotri, A.; Bhattacharya, S. SOLshare: Revolutionary Peer-to-Peer Solar Energy Trading in a Developing Market. In SAGE Business Cases; SAGE Publications: SAGE Business Cases Originals: 2022.

- Flanagan, K. For the common good. Renew: Technology for a Sustainable Future.

- Groh, S.; Zürpel, C.; Waris, E.; Werth, A. Analytics on pricing signals in peer-to-peer solar microgrids in Bangladesh. Economics of Energy & Environmental Policy 2022, 11, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Sirota, F.; Fratini, G. A case about Nubank: the story of an innovative fintech in Brazil. 2019.

- da Rosa, S.C.; Schreiber, D.; Schmidt, S.; Junior, N.K. MANAGEMENT PRACTICES THAT COMBINE VALUE COCREATION AND USER EXPERIENCE An Analysis of the Nubank Startup in the Brazilian Market. Revista de gestão, finanças e contabilidade 2017, 7, 22–43. [Google Scholar]

- Kushendriawan, M.A.; Santoso, H.B.; Putra, P.O.H.; Schrepp, M. Evaluating User Experience of a Mobile Health Application ‘Halodoc’using User Experience Questionnaire and Usability Testing. Jurnal sistem informasi 2021, 17, 58–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mangkunegara, C.N.; Azzahro, F.; Handayani, P.W. Analysis of factors affecting user's intention in using mobile health application: a case study of Halodoc. In Proceedings of the 2018 International Conference on Advanced Computer Science and Information Systems (ICACSIS); 2018; pp. 87–92. [Google Scholar]

- Tarmidi, D. The influence of product innovation and price on customer satisfaction in halodoc health application services during COVID-19. Turkish Journal of Computer and Mathematics Education (TURCOMAT) 2021, 12, 1716–1722. [Google Scholar]

- BIDWELL, N.; DE TENA, S.L. 31. ALTERNATIVE PERSPECTIVES ON RELATIONALITY, PEOPLE AND TECHNOLOGY DURING A PANDEMIC: ZENZELENI NETWORKS IN SOUTH AFRICA. COVID-19 FROM THE MARGINS.

- Hussen, T.S.; Bidwell, N.J.; Rey-Moreno, C.; Tucker, W.D. Gender and participation: critical reflection on Zenzeleni networks in Mankosi, South Africa. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the First African Conference on Human Computer Interaction, 2016; pp. 12–23.

- Africa, A.o.S.o.S. Building Profitable and Sustainable Community Owned Connectivity Networks. 2020.

- Pather, S. Op-ed1: Towards an enabling environment for a digital ecosystem: A foundation for entrepreneurial activity. 2021.

- Rey-Moreno, C.; Pather, S. Advancing rural connectivity in south africa through policy and regulation: a case for community networks. In Proceedings of the 2020 IST-Africa Conference (IST-Africa); 2020; pp. 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Bakıcı, T.; Almirall, E.; Wareham, J. A smart city initiative: the case of Barcelona. Journal of the knowledge economy 2013, 4, 135–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bibri, S.E.; Krogstie, J. The emerging data–driven Smart City and its innovative applied solutions for sustainability: The cases of London and Barcelona. Energy Informatics 2020, 3, 1–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capdevila, I.; Zarlenga, M.I. Smart city or smart citizens? The Barcelona case. Journal of strategy and management 2015, 8, 266–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gascó-Hernandez, M. Building a smart city: lessons from Barcelona. Communications of the ACM 2018, 61, 50–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, A.; Martín, P.P. Going beyond the smart city? Implementing technopolitical platforms for urban democracy in Madrid and Barcelona. In Sustainable Smart City Transitions; Routledge: 2022; pp. 280-299.

- Calzada, I.; Cobo, C. Unplugging: Deconstructing the smart city. Journal of Urban Technology 2015, 22, 23–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calzada, I. (Smart) citizens from data providers to decision-makers? The case study of Barcelona. Sustainability 2018, 10, 3252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Driver’s Seat. Driver’s Seat - Know more. Earn more. Use your data to maximize rideshare and delivery earnings and take control of your work. Available online: https://driversseat.co/ (accessed on 3. April).

- Calzada, I. 16. knowledge building and organizational behavior: the Mondragón case from a social innovation perspective. The international handbook on social innovation: Collective action, social learning and transdisciplinary research.

- Massimo, C.; Marina, M.; Jiri, H.; Igor, C.; Steven, L.; Marisa, P.; Jaap, B. Digitranscope: The governance of digitally-transformed society. 2021.

- Bignami, F.; Calzada, I.; Hanakata, N.; Tomasello, F. Data-driven citizenship regimes in contemporary urban scenarios: An introduction. 2022, 1-15.

| Key Challenge | Description |

|---|---|

| Market Concentration | The network effects, economies of scale, and lock-in effects experienced by large technology companies have led to an increasing concentration of digital resources and capabilities. This creates a barrier for new entrants, particularly SMEs and small communities, stifling competition, and innovation. |

| Digital Exclusion | Due to the monopolistic nature of the digital landscape, small communities and SMEs often lack affordable and accessible digital infrastructure and resources, leading to digital exclusion and perpetuating inequality. |

| Insufficient Data Governance |

Many small communities and SMEs lack robust data governance structures and open standards, making it difficult for them to harness the full potential of data-driven insights and decision-making. |

| Underdeveloped Skills and Capacity |

The existing concentration of resources and capabilities in the digital landscape contributes to a skills gap in small communities and SMEs, limiting their ability to participate in the digital economy and adapt to technological advancements. |

| Eroding Self-Determination and Data Sovereignty |

The increasing influence of AI-driven decision-making and the dominance of a few major players in the digital landscape undermine the self-determination of small communities and SMEs, restricting their ability to shape their digital futures through data sovereignty [3]. |

| Case Study | Description |

|---|---|

|

Case Study 1: Mobile Money in Africa (Kenya's M-Pesa) |

M-Pesa, a mobile money platform launched in Kenya, revolutionized financial inclusion by providing affordable, accessible, and secure digital financial services to millions of unbanked individuals [67,68,69]. This example illustrates the transformative potential of a digital platform that effectively empowers small communities and businesses. However, the challenge remains to extend the benefits of such platforms to other sectors, including education, healthcare, and supply chain management, by establishing data cooperatives and adopting open standards [70,71]. |

|

Case Study 2: Digital Agriculture in Asia (India's eKutir) |

eKutir [72,73], a social enterprise in India, leverages digital technologies to empower smallholder farmers through data-driven agricultural advice, access to finance, and market linkages. By pooling data and resources from various stakeholders, eKutir demonstrates the potential of a data cooperative to drive sustainable development in rural communities. Yet, scalability and replicability of this model require supportive policies and a robust digital governance framework [74,75] |

|

Case Study 3: Collaborative Land Management in Africa (Ghana's Farmerline) |

Farmerline [76], a Ghanaian agriculture technology company, provides smallholder farmers with timely and accurate agricultural information through mobile technology. By pooling data from various sources, Farmerline exemplifies the potential of data cooperatives to drive sustainable development and food security in rural areas. To scale and replicate this model, supportive policies and a strong digital governance framework are essential, along with financial support from international partners [76,77]. |

|

Case Study 4: Decentralized Renewable Energy in Asia (Bangladesh's SOLshare) |

SOLshare [78], a peer-to-peer energy trading platform in Bangladesh, enables rural communities to access affordable, clean energy by connecting solar home systems in a decentralized network. The platform exemplifies the transformative potential of data cooperatives in promoting sustainable development. Nevertheless, the broader adoption of such models requires the development of open standards, APIs, and legal frameworks that support data sharing and collaboration [79,80]. |

|

Case Study 5: Fintech for Financial Inclusion in South America (Brazil's Nubank) |

Nubank [81], a Brazilian digital bank, has successfully expanded access to financial services for millions of underserved individuals in the region. By leveraging digital technologies and data-driven solutions, Nubank illustrates the potential of innovative platforms to empower small communities and businesses. Further development of data cooperatives in this sector can facilitate better credit access and risk assessment for SMEs, requiring supportive policies and collaboration between stakeholders [82]. |

|

Case Study 6: Telemedicine in Asia (Indonesia's Halodoc) |

Halodoc [83], an Indonesian telemedicine platform, connects patients in remote areas with healthcare professionals through digital consultations, improving access to quality healthcare services. This initiative demonstrates the value of digital platforms in addressing critical challenges faced by rural communities. The expansion of such platforms, combined with the establishment of data cooperatives, can empower local communities and healthcare providers to make more informed decisions. However, this requires the development of robust data governance structures and open standards [84,85]. |

|

Case Study 7: Community Networks in Africa (South Africa's Zenzeleni) |

Zenzeleni [86,87], a community-owned telecommunications network in South Africa, provides affordable internet access to rural communities by leveraging cooperative ownership and management [88]. The initiative highlights the importance of local ownership and collaboration in bridging the digital divide. However, regulatory barriers and limited resources impede the expansion of such initiatives, calling for policy interventions and financial support from G20 countries [89,90]. |

|

Case Study 8: Construction Industry in Bavaria, Germany (Germany's GemeinWerk) |

GemeinWerk [1] proposed the first construction data cooperative in Munich, Germany. The case study of this Bavarian Construction Data Cooperative, which was launched by the Bavarian Construction Industry Association and GemeinWerk Ventures and will be operated by cooperative members, aims to provide small and medium-sized enterprises in the construction industry with access to shared services and construction data via a digital collaborative platform and data cooperative. This platform improves collaboration and organization within the construction value chain. The project primarily targets governance innovations to intensify industry collaboration, enable trust-based data sharing among stakeholders, and create a pre-competitive space of trust that drives productivity and innovation among SMEs through ecosystem collaboration. |

|

Case Study 9: Smart City Initiatives in Europe (Barcelona, Spain and Salus Coop, Spain) |

Barcelona's smart city initiatives [91,92,93] leverage digital technologies and data-driven solutions to improve urban services and enhance the quality of life for its residents. By utilizing data from various sources, such as sensors and citizen feedback, the city has implemented projects related to transportation, waste management, and energy efficiency. This case study demonstrates the potential of data cooperatives and digital federation platforms to facilitate collaboration among stakeholders in urban environments i.e. Salus Coop [9,28,45,56]. However, the expansion of such initiatives requires the development of open standards, robust data governance structures, and the active involvement of citizens in decision-making processes as the case of Barcelona has shown reverting the technocratic approach to smart city paradigm [94,95,96,97]. |

|

Case Study 10: Ride-hailing platform initiative. (Driver’s Seat, US) |

Driver's Seat Cooperative [98] is a driver owned cooperative that operates in a number of cities in the US. It enables gig-economy workers working in the ride-hailing sector to collect, pool and analyse data collected on a smartphone whilst undertaking work for ride-hailing platforms such as Uber and Lyft. The pooled data allows insights to be fed back to members so that they can optimise their incomes. The cooperative also sells data and insights to city agencies to enable better policy decisions with the profits from sales being redistributed back to members. |

| Recommendation | Description |

|---|---|

|

Recommendation 1: Encourage the establishment of digital federation platforms and data cooperatives |

|

|

Recommendation 2: Develop and harmonize supportive policies and legal frameworks |

|

|

Recommendation 2: Develop and harmonize supportive policies and legal frameworks |

|

|

Recommendation 3: Facilitate access to funding and resources |

|

|

Recommendation 4: Strengthen capacity building and skills development |

|

|

Recommendation 5: Foster international cooperation and knowledge sharing |

|

| Recommendation 6: Establish monitoring and evaluation mechanisms |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).