Submitted:

07 April 2023

Posted:

10 April 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

- First, it focusses on Rwanda’s health-related educational problems and discusses how they might be solved. Throughout this descriptive material we emphasise that providing effective and empowering education depends not only on school resources and what happens in school but also on the context of schooling. Issues of child health and development - often neglected when framing educational policy - have a definite bearing on school success.

- Secondly, therefore, education and health are not separate properties or aspects of a child’s life but combine with the rest of his or her context to create experiences and capabilities or barriers to capability, holistically. The two are often seen as separate areas of policy, generally run from different ministries. In developing countries this ‘blind spot’ can mean that those in schools are not all fit to benefit from the education they are offered : health and child development problems are barriers to education which were neglected in the past. Children under the age of 5 have predominantly been the concern of the Health Sector in Rwanda, and the Ministry did not have school readiness as a prioritised target, while children aged 5+ fell to Education and mostly ceased to be a central concern for Health, except for girls of reproductive age.

- We argue here that good health is not something separate from effective education; the latter depends on the former in terms of both readiness for school and maintenance in a fit state to benefit from it.

2. Contexts: Poverty and Policy

2.1. Poverty and the Political Economy

2.2. Policy and Implementation

3. Overcoming Educational Barriers

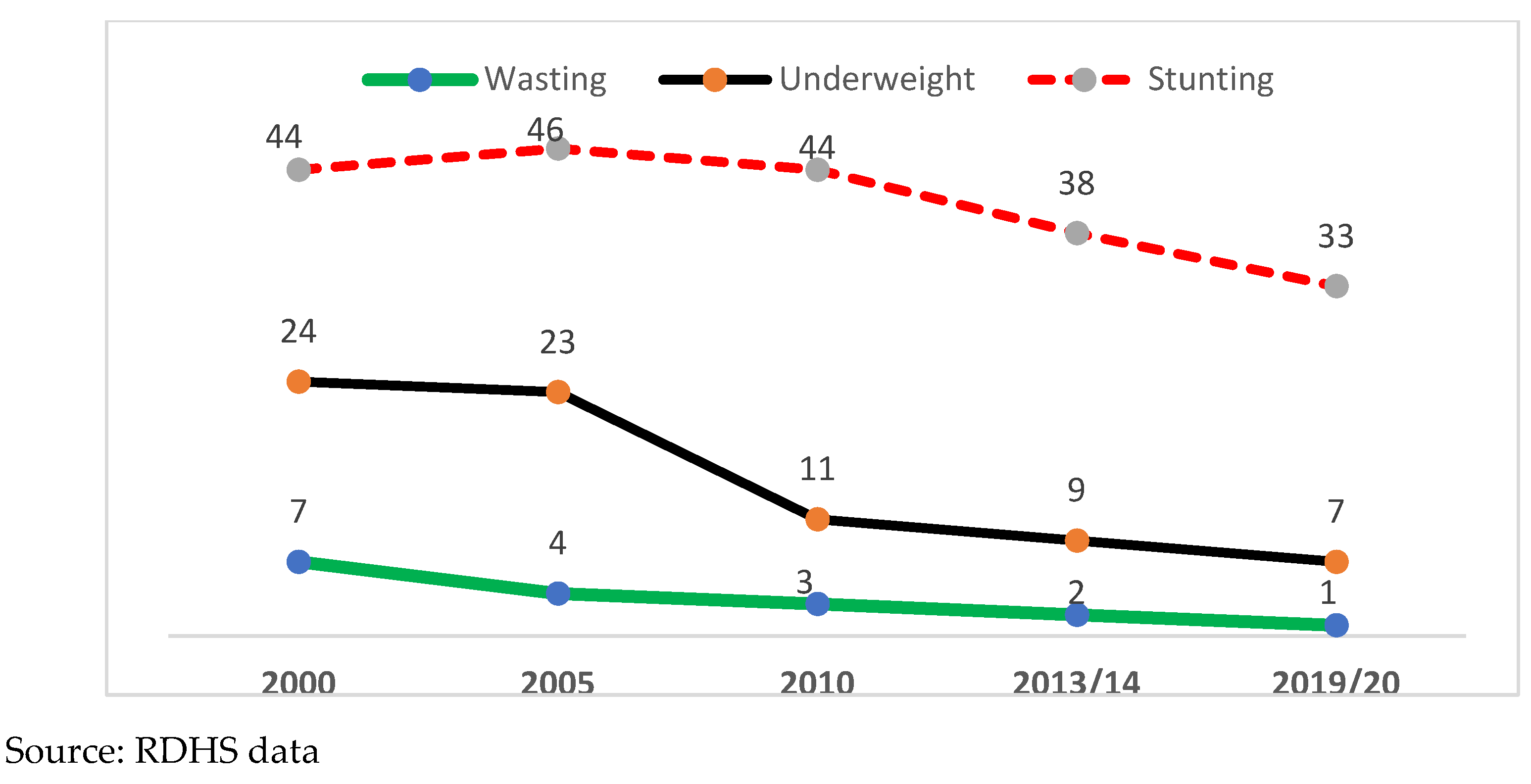

3.1. Stunting

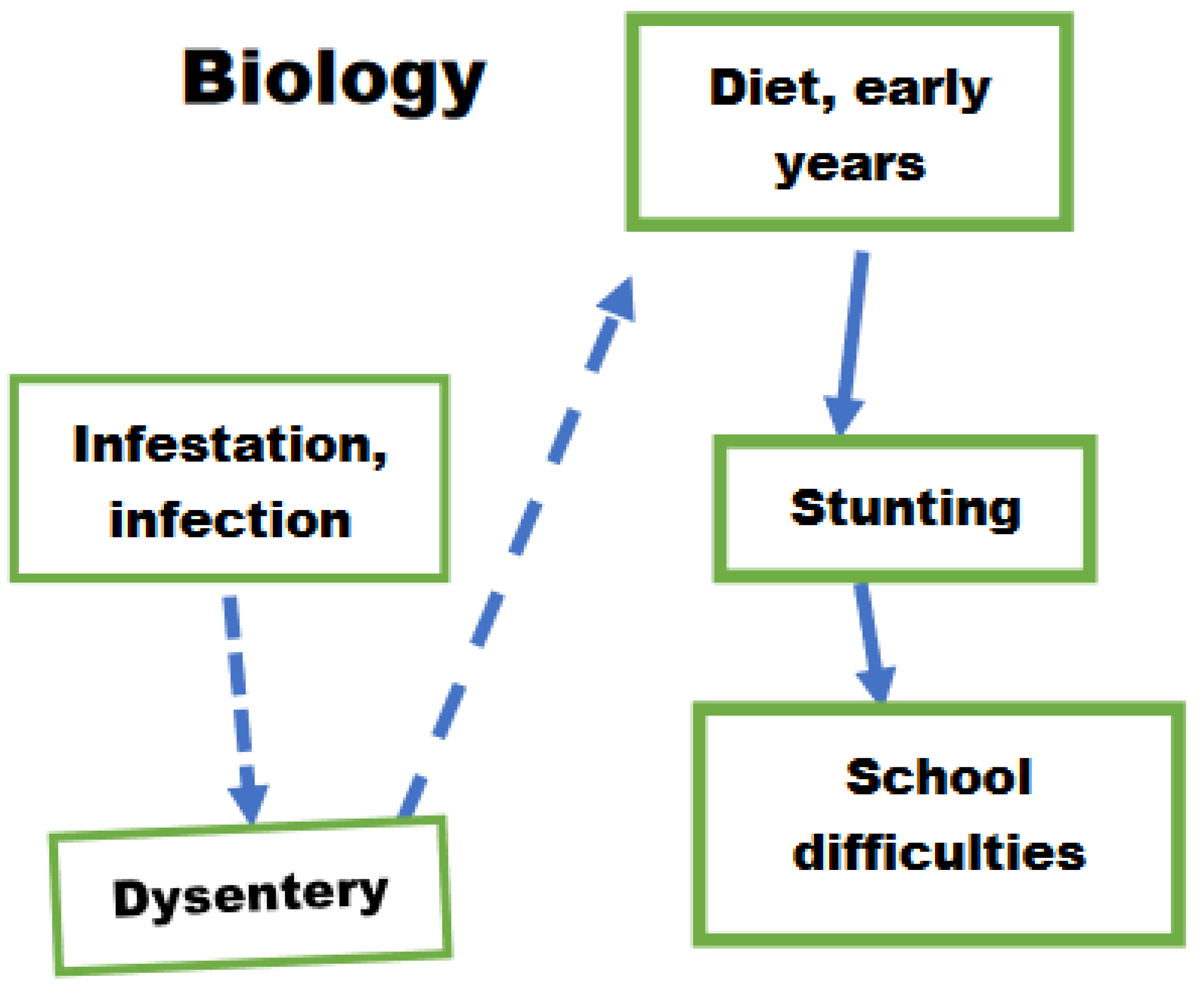

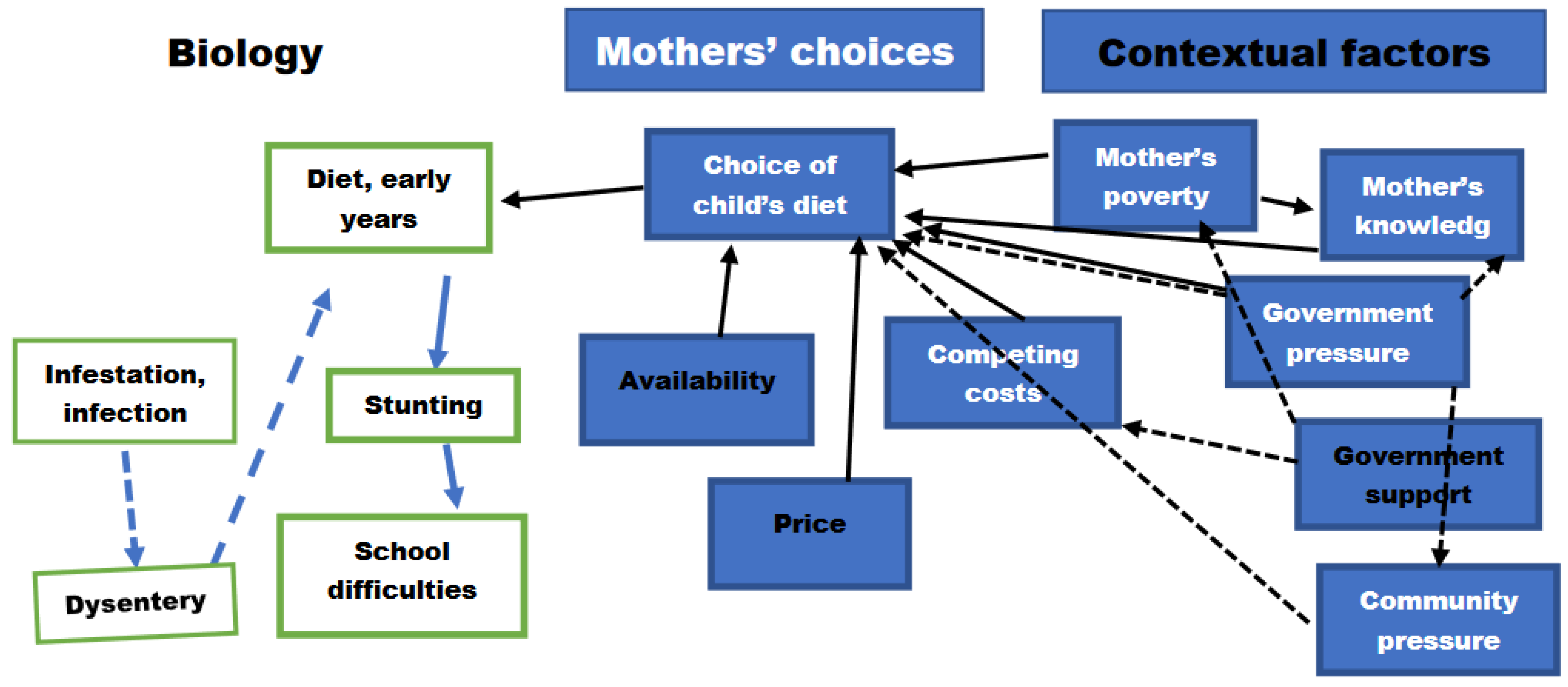

- It is avoidable only by feeding infants a diverse diet to ensure an adequate range of essential micronutrients (Black et al., 2017). Breastfeeding is vital for babies and infants, and because if ‘comes free’ there is a temptation in any poor country to rely exclusively on the breast for well over a year, but the introduction of solids from various food groups should start alongside it at six months to ensure that infants get essential vitamins and minerals (Miller et al., 2015).

- Alternatively, poor hygiene and contaminated water or soil may cause diarrhoea/dysentery, denying the children the benefit of what they eat (Lo et al., 2018).

- Stunting constrains cognitive as well as physical development (Berkman et al., 2002; Crookston et al., 2011; Miller et al., 2015; Powell et al., 1995) and impairs learning at school (Clarke & Grantham-McGregor, 1991; Glewwe et al., 2001; Jamison, 1986; Miller et al., 2015; Sunny et al., 2018), thereby restricting future productivity and earnings (Haywood & Pienaar, 2021). Malnutrition here is better seen as a social problem than a fault of parenting. Most Rwandan households struggle to provide a bare sufficiency to eat and do not typically eat the range of foodstuffs necessary to ensure that children get adequate micronutrients in the early years.

3.2. Early Stimulation

4. Health In School

4.1. Nutrition – Going Hungry to School

- A subsidised Secondary School Feeding Pilot Programme,

- One Cup of Milk per Child in selected pre-primary and lower primary schools and all ECD centres, and

- Home-Grown School Feeding Programmes for 104 schools (85,000 pupils) supported by the World Food Programme (WFP, 2022).

4.2. Parasitic Infestations and Infectious Diseases

4.3. Education for Health

4.4. Control of Attention, Psychological Support and Dealing with Depression

5. Discussion

5.1. Evidence-Based Policy and Material Causation

5.2. The Importance of Contexts

5.3. Choice, Meaning and Agency

References

- EICV – Integrated Household and Living Conditions Survey (National Institute of Statistics of Rwanda): http://www.statistics.gov.rw/datasource/integrated-household-living-conditions-survey-eicv.

- ESYB – Educational Statistics Yearbook (Ministry of Education): https://www.mineduc.gov.rw/publications?tx_filelist_filelist%5Baction%5D=list&tx_filelist_filelist%5Bcontroller%5D=File&tx_filelist_filelist%5Bpath%5D=%2Fuser_upload%2FMineduc%2FPublications%2FEDUCATION_STATISTICS%2FEducation_statistical_yearbook%2F&cHash=f4907f021d7175fc28e6cdebcc8bf83a.

- Mental Health Atlas (World Health Organisation) - data for Rwanda in 2017: https://www.who.int/mental_health/evidence/atlas/profiles-2017/RWA.pdf.

- RDHS – Rwanda Demographic and Health Surveys (National Institute of Statistics of Rwanda): http://www.statistics.gov.rw/datasource/demographic-and-health-survey-dhs.

- SYB – Statistical Yearbooks (National Institute of Statistics of Rwanda): http://www.statistics.gov.rw/statistical-publications/subject/statistical-yearbooks.

- WDI – World Development Indicators (World Bank): https://databank.worldbank.org/source/world-development-indicators.

- World Happiness Reports: https://worldhappiness.report/archive/.

- Abbott, P. , & D’Ambruoso, L. (2019). Rwanda Case Study: Promoting the Integrated Delivery of Early Childhood Development. /: Research Support Centre. https, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Abbott, P.; Sapsford, R. Rwanda: planned reconstruction for social quality. In Handbook of Quality of Life and Sustainability; Martinez, J., Mikkelsen, C., Phillips, R., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2021; pp. 81–100. [Google Scholar]

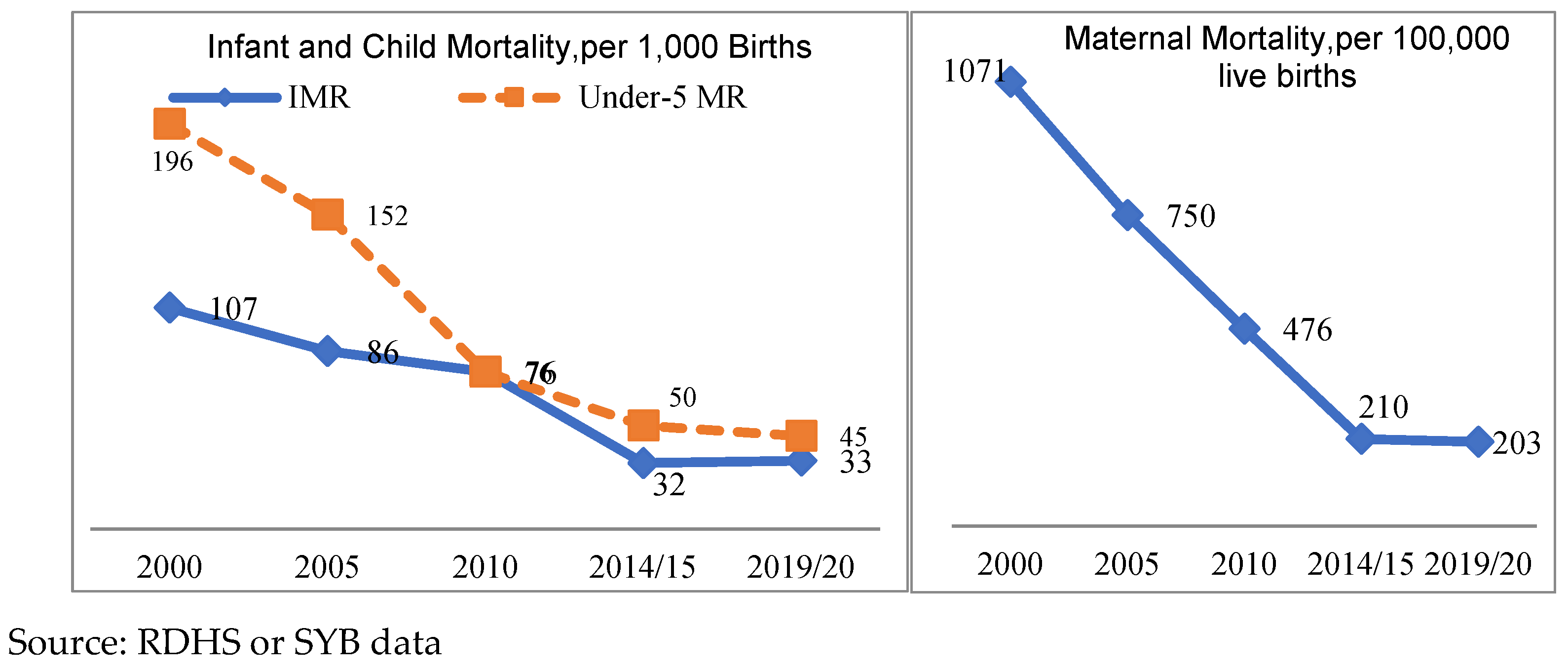

- Abbott, P.; Sapsford, R.; Binagwaho, A. (2017). Learning from success: How Rwanda achieved the Millennium Development Goals for health. World Dev. 2017, 92, 103–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

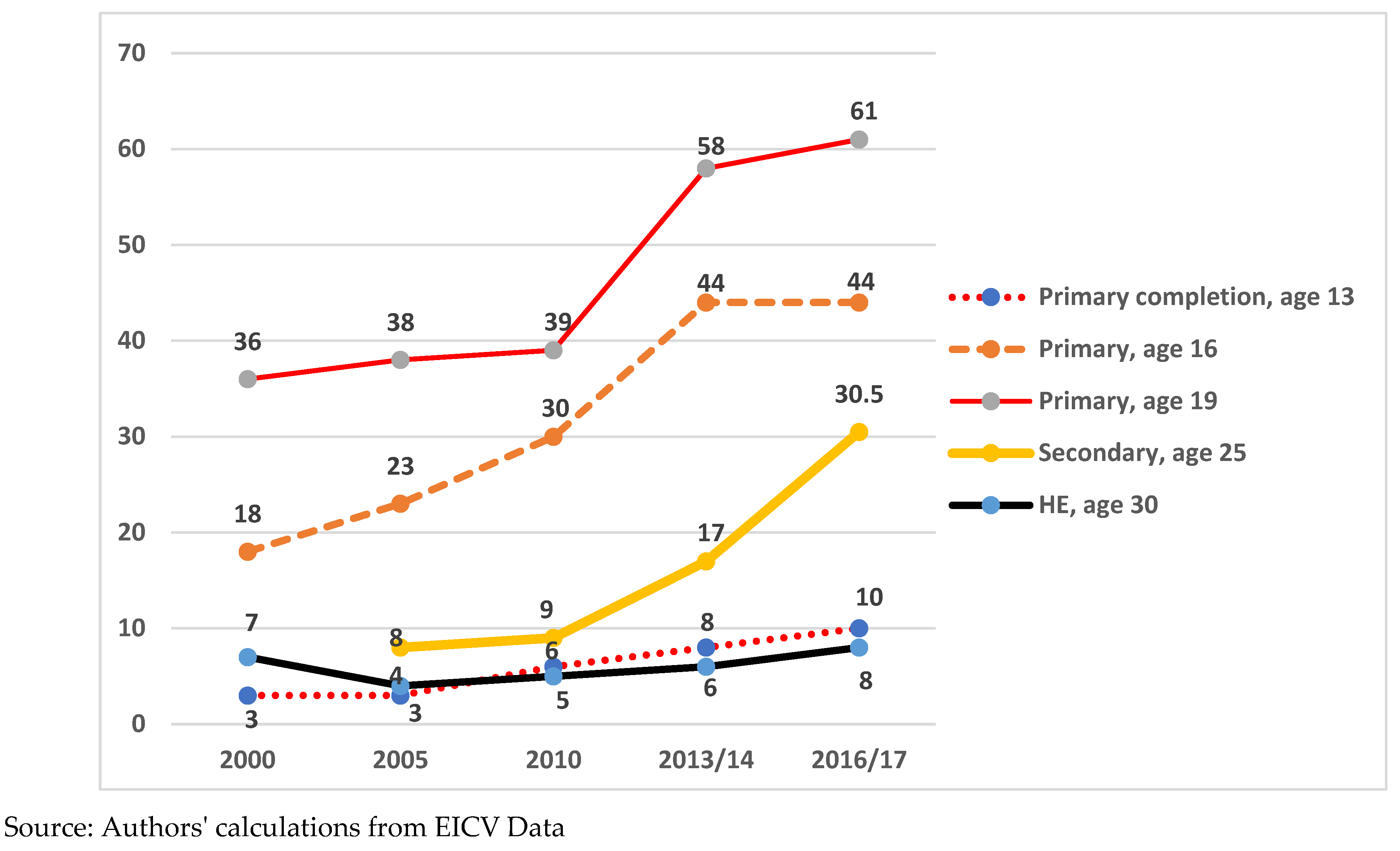

- Abbott, P.; Sapsford, R.; Rwirahira, J. Rwanda’s potential to achieve the millennium development goals for education. Int. J. Educ. Dev. 2015, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbott, P.; Wallace, C.; Sapsford, R. The decent society: Planning for social quality; Routledge: 2016. [CrossRef]

- Addiss, B. Tackling worms in children: school programmes can work - for eyes too. Community Eye Health 2013, 26, 29–31. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ahmed, A. Impact of feeding children in school: Evidence from Bangladesh. International Food Policy Research Institute. 2004. https://documents.wfp.org/stellent/groups/public/documents/liaison_offices/wfp121947.pdf.

- Berkman, D.; Lescano, A.; Gilman, R.; et al. Effects of stunting, diarrhoeal disease, and parasitic infection during infancy on cognition in late childhood: a follow-up study. Lancet 2002, 359, 564–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Black, M.M.; Walker, S.P.; Fernald, L.C.H.; Andersen, C.T.; DiGirolamo, A.M.; Lu, C.; McCoy, D.C.; Fink, G.; Shawar, Y.R.; Shiffman, J.; et al. Early childhood development coming of age: science through the life course. Lancet 2017, 389, 77–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Byrne, D.; Callaghan, G. Complexity Theory and the Social Sciences: the State of the Art. Routledge. 2013. https://www.taylorfrancis.com/books/mono/10.4324/9780203519585/complexity-theory-social-sciences-david-byrne-gillian-callaghan.

- Clarke, N.; Grantham-McGregor, S. Nutrition and health predictors of school failure in Jamaican children. Ecology, Food and Nutrition, 1991, 26, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clist, P.; Whitty, B.; Holden, J.; Abbott, P. Results Based Aid in Rwanda: Final Report. Upper Quartile and IPAR-Rwanda. 2015. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/563272/Results-Based-Aid-Rwandan-Education-final-eval.pdf.

- Crookston, B.; Dearden, K.; Alder, S.; et al. Impact of early and concurrent stunting on cognition. Matern. Child Nutr. 2011, 7, 397–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foucault, M. The subject and power. In H. Dreyfus & P. Rabinow (Eds.), Michel Foucault: Beyond Structuralism and Hermeneutics; Harvester: 1982.

- Glewwe, P.; Jacoby, H.; King, E. Early childhood nutrition and academic achievement: A longitudinal analysis. J. Public Econ. 2001, 84, 345–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- 23. Government of Rwanda. Rwanda 7-year Government Programme: National Strategy for Transformation, 2019-24, /: Rwanda. 2017. https, 2017.

- Haywood, X.; Pienaar, A. Long-term influence of stunting, being underweight and thinness on the education performance of primary school girls: the NW-CHILD study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 8973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hudson, K.; Lawton, R.; Hugh-Jones, S. Factors affecting the implementation of a whole school mindfulness program: A qualitative study using the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2020, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- 26. International Bank for Reconstruction and Development/World Bank. (2011). Rwanda - Education Country Status Report: Towwards Quality Enhancement and Achievement of Universal Nine Year Basic Education, /: https, 6777.

- 27. J-PAL. Deworming to increase school attendance.

- Jamison, D. Child malnutrition and school performance in China. J. Dev. Econ. 1986, 20, 299–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klingbeil, D.; Renshaw, T.; Willenbrink, J.; Copek, R.; Kai Tai Chan Haddock, A.; Yassine, J.; Clifton, J. Mindfulness-based interventions with youth: A comprehensive meta-analysis of group-design studies. J. Sch. Psychol. 2017, 63, 77–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lancet. (Lancet series) Early child development in developing countries. The Lancet, 2007.

- Lancet. (Lancet series) Early child development in developing countries 2011. The Lancet.

- Lancet. (Lancet Series) - Enhancing early childhood development: From science to scale. The Lancet, 2016.

- Lo, N.C.; Snyder, J.; Addiss, D.G.; Heft-Neal, S.; Andrews, J.R.; Bendavid, E. Deworming in pre-school age children: A global empirical analysis of health outcomes. PLoS Neglected Trop. Dis. 2018, 12, e0006500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marx, K. The Eighteenth Brumaire of Louis Bonaparte. In Marx’s “Eighteenth Brumaire” [1852]; Pluto Press: 2007; pp. [CrossRef]

- McEwan, P. The impact of Chile’s school feeding program on education outcomes. Econ. Educ. Rev. 2013, 32, 122–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, A.; Murray, M.; Thomso, D.; Arbour, M. How consistent are associations between stunting and child development? Evidence from a meta-analysis of associations between stunting and multidimensional child development in fifteen low- and middle-income countries. Public Health Nutr. 2015, 19, 1339–1347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- 37. Ministry of Education. Education Sector Strategic Plan, 2003.

- Ministry of Education. Early Child Development Policy, /: Education. 2011. https, 2011.

- Ministry of Education. Education Sector Strategic Plan 2013/14-2017/18. 2013.

- Ministry of Education. National School Health Policy, 2014.

- 41. Ministry of Education. National School Health Strategic Plan, 2014.

- Ministry of Education. National Comprehensive Schoool Feeding Policy, 2019.

- Ministry of Finance. Vision 2020, 2000.

- Ministry of Finance. (Poverty Reduction Strategy Paper. Republic of Rwanda. 2002. https://www.imf.org/external/np/prsp/2002/rwa/01/063102.

- Ministry of Finance. Economic Development and Poverty Reduction Strategy 2008-12, 2008.

- Ministry of Finance. Economic Development and Poverty Reduction Strategy 2 (2013-18), 2013.

- Ministry of Gender and Family Promotion. Early Child Development Policy, 2016.

- Ministry of Gender and Family Promotion. Minimum Standards and Norms for Early Childhood Development and Services in Rwanda. Republic of Rwanda. 2016.

- Ministry of Gender and Family Promotion. National Early Childhood Development Programme: National Strategic Plan 2018-2024, 2017.

- Mukumbang, F. Retroductive theorising: a contribution of Critical Realism to mixed methods research. J. Mix. Methos Res. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Musker, P.; Clist, P.; Abbott, P.; Boyd, C.; Latimer, K. Evaluation of Results Based Aid in Rwandan Education - 2013 Evaluation Report. Upper Quartile. 2014. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/312006/Rwanda-education-results-based-aid-evaluation.

- Ndagijimana, A. Adolescent Mental Health Landscape Assessment in Rwanda. UNICEF Rwanda. 2020. https:://www.unicef.

- 53. NECDP- National Early Childhood Development Programme. National Strategic Plan 2018-2024, 2018.

- NECDP. Integrated ECD Models Guidelines. Republic of Rwanda. 2019.

- 55. NECDP. National Social and Behavioural Change Communication Strategy for Integrated Early Childhood Development , Nutrition and WASH, /: 2019. https, 2019.

- Niwe, L. Rwanda: mental health programme extended to over 800 schools. New Times.

- Nokes, C.; Grantham-McGregor, S.; Sawyer, A.; ]Cooper, E.; et al. Moderate to heavy infections of Trichuris trichiura affect cognitive function in Jamaican school children. Parasitology 1992, 104, 539–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ntirenganya, E. Why RBC started mental health programmes in schools. New Times, t: https://www.newtimes.co.rw/news/why-rbc-started-mental-health-programme-schools#:~.

- Nzohabonimana, D. Water access a top priority for Rwandan schools as they reopen. Infonile, 2 November 2020. [Google Scholar]

- O’Higgins, N. Rwanda: Youth Labour Markets and the School-to-Work Transition. International Labour Organisation. 2020. https://www.ilo.

- Okito, M. Rwanda poverty debate: summarising the debate and estimating consistent historical trend. Rev. Afr. Political Econ. 2019, 36, 665–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patience, B.; Nnagozie, B.; Obumneke-Okeke, I. Impact of national home school feeding programme on enrolment and academic performance of primary school pupils. J. Emerg. Trends Educ. Res. Policy Stud. 2019, 10, 152–158. [Google Scholar]

- Paxson, C.; Schady, N. Cognitive development among young children in Ecuador: The roles of wealth, health, and parenting. J. Hum. Resour. 2007, 42, 49–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pillay, K.; Eagle, G. (2021). The case for mindfulness interventions for traumatic stress in high violence, low resource settings. Curr. Psychol. 2021, 40, 2400–2414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Powell, C.; Walker, S.; Himes, J.; et al. (1995). Relationships between physical growth, mental development and nutritional supplementation in stunted children: The Jamaican study. Acta Paediatr. 1995, 84, 22–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- 66. Presidential Order. Order Establishing the National Child Development Agency. Official Gazette, 2020.

- Ramadhani, J. K. An Assessment of the Effects of School Feeding Programme on the School Enrolment, Attendance and Academic Performance in Primary Schools in Singida District, Tanzania [Open University of Tanzania]. 2014. http://repository.out.ac.tz/599/1/JAPHARI_KINDI_RAMADHANI.

- 68. RESYST. A target for UHC: How much should governments spend on health? (Web page), t: School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine. 2017. https://resyst.lshtm.ac.uk/resources/a-target-for-uhc-how-much-should-governments-spend-on-health#:~, 2017.

- Ritz, B. Comparing abduction and retroduction in Peircean pragmatism and critical realism. J. Crit. Realism 2020, 14, 456–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rujeni, N.; Morona, D.; Ruberanziza, E.; Mazigo Humphrey, D.; Ruberanziza, E.; Mazigo, H.D. Schistosomiasis and soil-transmitted helminthiasis in Rwanda: an update on their epidemiology and control. Infect. Dis. Poverty 2017, 6, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rwanda Biomedical Centre. Rwanda Mental Health Survey. Rwanda Biomedical Centre. 2018.

- Sayer, A. Realism and Social Science. Routledge. 1999. https://uk.sagepub. 2079. [Google Scholar]

- Sayer, A. Critical realism and the limits to critical social science. J. Theory Soc. Behav. 2001, 27, 473–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sen, A. Rationality and Freedom. ): Harvard University Press. 2004.

- Sen, A. The Idea of Justice. Penguin. 2009.

- Soulakova, B.; Butzer, B.; Winkler, P. Meta-review on the effectiveness of classroom-based psychological interventions aimed at improving student mental health and well-being, and preventing mental illness. J. Prim. Prev. 2019, 40, 255–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sunny, B.; DeStavola, B.; Dube, A.; Kondowe, S.; Crampin, A.; Glyn, J. Does early linear growth failure influence later school performance? A cohort study in Karonga district, northern Malawi. PLoS-ONE 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tikley, L. What works, for whom, and in what circumstances? Towards a critical realist understanding of learning in international and comparative education. Int. J. Educ. Dev. 2015, 40, 237–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNESCO. Global Education Monitoring Report: Finance.

- UNICEF Rwanda. For Every Child: Rwanda, 2521.

- United Nations. Convention on the Rights of the Child.

- van de Kuilena, H.; Altinyelkena, H.; Voogt, J.; Nzabalirwa, W. Policy adoption of learner-centred pedagogy in Rwanda: a case study of its rationale and transfer mechanisms. Int. J. Educ. Dev. 2019, 67, 64–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WFP. Saving Lives, Changing Lives (World Food Programme website), 1448.

- Williams, M. Realism and Complexity in the Social Sciences. Routledge. 2021. https://www.taylorfrancis.com/books/mono/10.4324/9780429443701/realism-complexity-social-science-malcolm-williams#:~:text=Realism and Complexity in Social Science is an,complexity science%2C probability theory and social research methodology.

- Williams, T. *Education at our school is not free”: The hidden costs of fee-free schooling in Rwan. Comp. J. Comp. Int. Educ. 2014, 45, 931–952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, T. The political economy of primary education: Lessons from Rwanda. World Dev. 2017, 96, 550–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Bank, & Government of Rwanda. Future drivers of growth in Rwanda. World Bank. 2019.

- 88. World Bank Independent Evaluation Group. Later impacts of early childhood interventions: a systematic review, 2015.

- World Food Programme. Home-Grown School Feeding in Rwanda, 2020.

- World Health Organisation. Nurturing Care for Early Childhood Development, 1066.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).