Introduction

Globally the average age of the worlds’ population of older persons continues to upsurge. Two thirds of older persons live in developing regions, whereby their numbers are rising faster than in the developed regions (1). Similarly, a rapid growth spurt is occurring in the middle-income countries like Malaysia. It has a population of 32.7 million currently and 7% of this population consists of older persons aged above 65 years old (2). As population ages social support becomes increasingly relevant to support this vulnerable group.

An exchange of resources between two individuals either the provider or recipient with an aim to enhance the well-being of the recipient is defined as social support (3). It moderates the effects of health-related strain on mental health in older persons. In addition, it may buffer against the ill effects of stress on mental and physical health. The literature shows that social support is associated with mortality, depression and well-being (4,5,6,7,8).

Overall, in Malaysia, social support and networking prevalence was found to be lower among older persons at 30.76% (9). Correspondingly, having low income, being single, no depression, absence of activities of daily living and dependency in instrumental activities of daily living were important factors related to perceived social support (10). It is therefore important to increase social support and networking among older persons by providing avenues for them to actively participate and engage with the community.

Social support is also extremely vital in the tobacco cessation planning among current smokers. Cigarette smoke contains many perilous compounds that can cause morbidity (11). In Malaysia, very few studies have examined the prevalence of smoking in the older population, with most studies focusing on smoking among adolescents. The prevalence rate for current older smokers in Malaysia in 2015 was 11.9% (12). Tobacco usage is recognized as one of the primary causes of non-communicable diseases and premature deaths in low and middle-income countries worldwide (13). An estimated 71% of lung cancers, 42% of chronic respiratory diseases and nearly 10% of cardiovascular diseases are caused by tobacco smoking (14). The risk of communicable diseases such as tuberculosis and lower tract respiratory infections and decreasing life expectancy (15,16) are also attributed to smoking. Smoking is also associated with divorce, depression, and anxiety (17). With relevance to this good social support is essential during quit smoking efforts by the relevant authorities. Additionally, in view of the scarce data on social support and its association with smoking status and its associated factors among the older Malaysian population this study was conducted.

Methods

Data source and study population

We analyzed data from the National Health and Morbidity (NHMS) 2018 survey on health of older Malaysian adults. The NHMS 2018 was a cross-sectional, population-based, nationally representative survey conducted by the Institute for Public Health, National Institutes of Health, Ministry of Health Malaysia. This study was funded by the Ministry of Health, Malaysia in which data collection was conducted between August 2018 and October 2018. The target population of this survey was pre-elderly aged between 50 years and 59 years and older persons aged 60 years and above. There were 3,959 older people recruited into the survey. We included only the 3929 older people aged 60 years and above in the final analysis after excluding non-citizens and missing data The Medical Research and Ethics Committee of the Ministry of Health Malaysia had approved this study (NMRR-17-2655-39047)

Sampling method

The sampling frame of the survey was provided by Department of Statistics of Malaysia, which was updated in 2017. Malaysia is geographically divided into about 83, 000 enumeration blocks (EBs). In each EBs, there were approximately 80 to 120 living quarters (LQs) with average household size of 4. This survey applied multiple-stage cluster sampling. First, Malaysia was stratified into states (primary stratum). Second, each state was further stratified into urban and rural areas (secondary stratum). The total number of EBs selected were proportionate to the population size. A total of 60 EBs from urban areas and 50 EBs from rural areas were randomly selected, which consisted of 5,636 LQs. All the household members aged 50 years and above were recruited into the study. The detailed methodology for this survey was reported elsewhere (9)

Statistical analysis

A weighting factor was applied to each individual data to adjust for non-response and probability of selection to account for the complex samples design to ensure sufficient representative of the elderly population in Malaysia. The sociodemographic information (residential area, gender, age, ethnicity, marital status, education level, employment status and monthly individual Income received), social support, smoking status (non-smoker, former smoker and current smoker) were presented in frequencies and percentages. Univariable logistic regression was conducted to determine the associations between sociodemographic characteristics, smoking status, and risk of having poor social support. The variables with significant level less than 0.25 were entered into multiple variable logistic regression analysis. Multiple variable logistic regression analysis was applied to determine the association between smoking status and risk of having poor social support among the elderly, while adjusting for other confounders in the logistic regression model. Hosmer Lemeshow test was used to examine the goodness of fit of the model and also there were no significant 2-way interactions or multicollinearity found between the variables. All statistical analyses were carried out at 95% significance level using IBM SPSS statistics for Window version 26.

Results

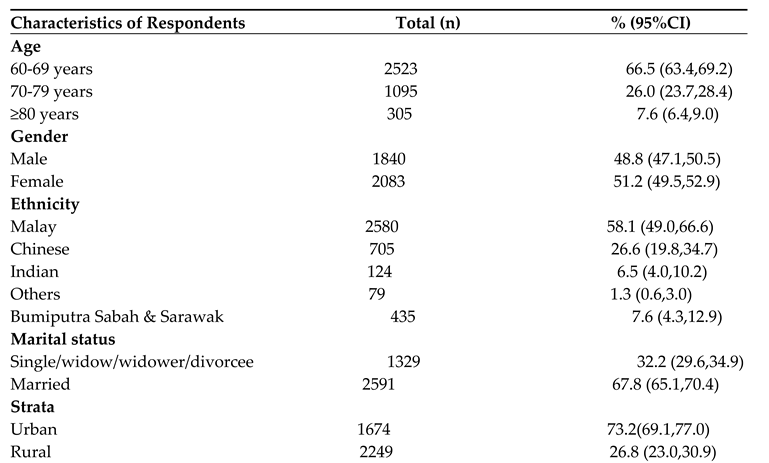

A total of 3923 elderly respondents participated in the study with majority in the 60-69 years age group (66.5%), females (51.2%), Malays following the general Malaysian population (58.1 %), married (67.8%),from urban areas (73.2%), had primary education (43.6 %), unemployed (75.8%), with income less than RM1000 (58.2%), non-smokers (74.3%) and not living alone (93.7%), (

Table 1).

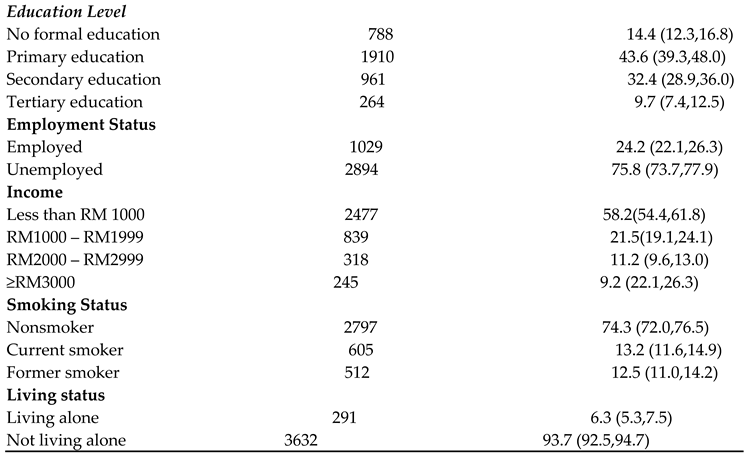

The prevalence of good social support was significantly higher among the 60-69 years old respondents compared to the > 80 years old (73.1%, 95% CI :69.3% -76.5% vs 50.1 %, 95% CI:41.7 %- 58.6%). Multivariate logistic regression analysis showed that the odds of poor social support were 1.7 times (aOR: 1.72 % ,95%CI: 1.19 -2.48) higher for the respondents aged > 80 years old, than those aged 60-69 years, after controlling for the other predictors in the model. Respondents with no formal education were 1.93 higher odds of poor social support than the respondents with tertiary education (aOR: 1.93%, 95%CI: 1.13,3.30). Respondents with income < RM 1000 were 1.94 times more likely to have poor social support compared to respondents with income > RM 3000 (aOR: 1.94, 95% CI : 1.21 -3.13). Former smokers have good social support compared to current smokers (73.6% ,95% CI: 67.7-78.7 vs 65.1 %, 95%CI:58.4 -71.2).For current smokers, the odds of poor social support were 42.0% higher than for non-smokers (aOR: 1.42, 95% CI: 1.05 -1.91), holding the other predictors constant.

Discussion

To the best of our knowledge this is the first paper exploring role of social support and smoking status and its associated factors in a nationally representative sample of older Malaysians. The prevalence of good social support was 73% in the 60-69 years old compared to 50% in the 80 years and more Malaysians. Additionally, the 80 years and more respondents were more likely to be associated with risk of poorer social support compared to their younger peers. The probable reasons for the poor social support in the 80 years and above was probably due to lack of spousal support due to illness or death (21) and low income (10) contributed by retirement.

Educational profiling found that respondents with no formal education and having an income of < RM 1000 and were almost twice as likely to have poorer social support. This latter finding concurs with the literature in which older respondents with lower income were perceived to have poorer social support (10).

The prevalence for non-smokers, current smokers and former smokers were 74.3% , 13.2% and 12.5% in our study compared to 36.3%,11.9% and 24.4% in 2015 (13). The prevalence of non-smokers and former/ex-smokers has increased (22) and current smokers has reduced. The reasons for this are probably due to an increase in diseases in older respondents hence they quit smoking and the rigorous quit smoking campaigns conducted by the government. In addition, the prevalence of current smoker in our paper was lower than smokers in the middle and older ages in South Korea which was 17.4% (23). This discrepancy was due to their operational definition which had included both middle and older age group in the South Korean study.

In terms of smoking status, our result showed that former smokers had the highest prevalence of good social support, followed by never smokers and current smokers. There was a significant association between smoking and poor social support. This finding concurs with a local study published by Rusdi et al, 2019 (17), which states that current smokers have lower income and lower education level which probably contributed to the poor social support. Furthermore, cessation of smoking depends on good social support through behavioral interventions and strong support from family and friends based on the literature (24).

Strength and limitations

The study's strength is that it is a nationally representative health morbidity survey with a large sample size of Malaysian older adults. Nevertheless, the cross-sectional study design does not allow the causal relationship to be established between social support and smoking status. Additionally, the data on smoking status were self-reported, this may cause response bias. Hence, there may have been underestimating or overestimating of prevalence of smoking.

Conclusions

This study highlighted that there is poor social support among older persons who were current smokers. In addition, there is poor social support in advancing age, those with no formal education and low income However, further longitudinal studies are needed to determine the exact effects of the studied variables. Besides, these findings could assist the policymakers to develop strategies at the national level in to enhance social support among the older smokers to ensure cessation of smoking to promote healthy ageing.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: Krishnapillai A, Kee CC, Ariaratnam S, Omar MA, Sooryanarayana R, Kiau HB, Ghazali SS, Tauhid NM, Sheleaswani Inche Zainal Abidin; Data curation: Kee CC, Omar MA; Formal analysis: Kee CC, Omar MA,Ridwan BS; Investigation: Ambigga Devi Krishnapillai; Methodology: Krishnapillai A, Kee CC, Ariaratnam S, Omar MA, Sooryanarayana R, Kiau HB, Ghazali SS, Tauhid NM, Sheleaswani Inche Zainal Abidin, Ridwan BS; Project administration: Ambigga Devi Krishnapillai, Kee CC, Omar MA; Software: Kee CC; Validation: Kee CC; Writing – original draft: Krishnapillai A, Kee CC, Ariaratnam S, Omar MA; Writing – review & editing: Krishnapillai A, Kee CC, Ariaratnam S, Omar MA, Sooryanarayana R, Kiau HB, Ghazali SS, Tauhid NM, Sheleaswani Inche Zainal Abidin.

Funding

Ministry of Health Malaysia, Award number: NMRR-14-1064-21877, The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish or preparation of the manuscript. The authors received no specific salary for this work.

Ethics approval

The NHMS 2018 was approved by the Medical Research Ethics Committee, Ministry of Health Malaysia (NMRR-17-2655-39047).

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication not required.

Data availability statement

Data are available upon reasonable request. The dataset used and analyzed in this study is available from the National Institutes of Health, Ministry of Health Malaysia on reasonable request and with permission from the Director General of Health, Malaysia.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the Director General of Health Malaysia for his support and permission to publish this study.

Conflicts of Interest

Non declared.

References

- Department of Economic and Social Affairs. World population ageing highlights, United Nations, 2017.

- Department of Statistic and Economic Planning Unit Malaysia. Current population estimates, 2020, Malaysia.

- Shumaker, S. A. and Brownell, A. (1984), Toward a Theory of Social Support: Closing Conceptual Gaps. Journal of Social Issues, 40: 11-36. [CrossRef]

- Berkman, L. F. and Syme, S. L. (1979) ‘Social networks, host resistance, and mortality: a nine-year follow-up study of Alameda County residents.’, Am J Epidemiol, 109(2), pp. 186–204. [CrossRef]

- Chen, X. and Silverstein, M. (2000) ‘Intergenerational social support and the psychological well-being of older parents in China.’, Research on Aging, 22(1), pp. 43–65.

- Holt-Lunstad, J. , Smith, T. B. and Layton, J. B. (2010) ‘Social relationships and mortality risk: A meta-analytic review’, PLoS Medicine, 7(7). [CrossRef]

- Schwarzbach, M. et al. (2014) ‘Social relations and depression in late life - A systematic review’, International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 29(1), pp. 1–21. [CrossRef]

- Gariepy, G. et al. (2016) ‘Social support and protection from depression: systematic review of current findings in Western countries.’, The British Journal of Psychiatry. Institute for Health and Social Policy, McGill University, Montreal, Canada: Royal College of Psychiatrists, 209(4), pp. 284–293. [CrossRef]

- Institute for Public Health (IPH) 2019. National Health and Morbidity Survey 2018 (NHMS 2018): Elderly Health. Vol. I: Methodology and General Findings, 2018.

- Mahmud MA, Hazrin M, Muhammad EN, Mohd Hisyam MF, Awaludin SM, Abdul Razak MA, Mahmud NA, Mohamad NA, Mohd Hairi NN, Wan Yuen C. Social support among older adults in Malaysia. Geriatr Gerontol Int. 2020 Dec;20 Suppl 2:63-67. PMID: 33370852. [CrossRef]

- Talhout, R.; Schulz, T.; Florek, E.; Van Benthem, J.; Wester, P.; Opperhuizen, A. Hazardous compounds in tobacco smoke. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2011, 8, 613–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lim KH, Teh CH, Pan S, et al. Prevalence and factors associated with smoking among adults in Malaysia: Findings from the National Health and Morbidity Survey (NHMS) 2015. Tob Induc Dis. 2018;16:01. Published 2018 Jan 26. [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Tobacco: key facts. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2018 (https://www.who.int/en/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/tobacco, accessed 20 April 2021).

- Mathers CD, Loncar D. Projections of global mortality and burden of disease from 2002 to 2030. PLoS Med 20.16;3:e442. [CrossRef]

- Line H, Ezzati M, Murray M. Tobacco smoke, indoor air pollution and tuberculosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS Medicine 2007;4:e20. [CrossRef]

- Doll R, Peto R, Boreham J, Sutherland I. Mortality in relation to smoking: 50 years’ observations on male British doctors. BMJ 2004; 328:1519.

- Rusdi AR, Sharmilla K, Mahmoud D, et al. The prevalence of smoking, determinants, and chance of psychological problems among smokers in an urban community housing project in Malaysia. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 2019 May; 6 (10):1762.

- Ismail NR, Hamid AA, Ab Razak A, Hamid NA. factors influencing instrumental activities of daily living (IADL) disability among elderly attending health clinics in Kelantan. Malaysian Applied Biology. 2021 Nov 30;50(2):37-45.

- Koenig HG, Westlund RE, George LK, Hughes DC, Blazer DG, Hybels C. Abbreviating the Duke Social Support Index for use in chronically ill elderly individuals. Psychosomatics. 1993 Jan 1;34(1):61-9.

- Strodl, E. & Kenardy, J. 2008. The 5-item mental health index predicts the initial diagnosis of nonfatal stroke in older women. J Womens Health (Larchmt), 17(6): 979-986.

- Gupta, V, Korte, C. The effects of a confidant and a peer group on the well-being of single elders. Int J Aging Hum Dev 1994; 39: 293–302.

- Yun EH, Kang YH, Lim MK, Oh JK, Son JM. The role of social support and social networks in smoking behavior among middle and older aged people in rural areas of South Korea: a cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health. 2010 Feb 18;10:78. [CrossRef]

- Kuang Hock Lim, Hui Li Lim, Sumarni Mohd Ghazali et al. Prevalence and factors associated with smoking cessation among elderly in Malaysia- A findings from the population-based study. International Journal of Public Health Research Vol 11 No 1 2021, pp (1317-1325).

- Soulakova JN, Tang CY, Leonardo SA, Taliaferro LA. Motivational Benefits of Social Support and Behavioural Interventions for Smoking Cessation. J Smok Cessat. 2018 Dec;13(4):216-226. Epub 2018 Jan 21. PMID: 30984294; PMCID: PMC6459678. [CrossRef]

Table 1.

Sociodemographic characteristics of the participants (N=3923).

Table 1.

Sociodemographic characteristics of the participants (N=3923).

Table 2.

Association between social support with sociodemographic and smoking status.

Table 2.

Association between social support with sociodemographic and smoking status.

| Variables |

Social support |

Crude OR, (95% CI) |

p value |

*AOR( 95%CI) |

P value |

| Good |

Poor |

| n |

% (95% CI) |

n |

% (95% CI) |

| Age |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 60-69 years |

1823 |

73.1(69.3,76.5) |

689 |

26.9(23.5,30.7) |

1.00 |

|

1.00 |

|

| 70-79 years |

688 |

65.0(59.2,70.4) |

401 |

35.0(29.6,40.8) |

1.46(1.17,1.82) |

<0.01 |

1.18(0.92,1.50) |

0.19 |

| ≥80 years |

155 |

50.1(41.7,58.6) |

149 |

49.9(41.4,58.3) |

2.70(1.95,3.73) |

<0.01 |

1.72(1.19,2.48) |

<0.01 |

| Gender |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Male |

1297 |

72.7(68.2,76.8) |

532 |

27.3(23.2,31.8) |

1.0 |

|

1.00 |

|

| Female |

1369 |

65.9(61.6,70.0) |

707 |

34.1(30.0,38.4) |

1.38(1.12,1.70) |

<0.01 |

0.99(0.77,1.28) |

0.94 |

| Ethnicity |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Malay |

1778 |

71.1(66.9,75.0) |

791 |

28.9(25.0,33.1) |

0.89(0.58,1.35) |

0.56 |

1.15(0.73,1.81) |

0.55 |

| Chinese |

450 |

65.8(58.4,72.5) |

248 |

34.2(27.5,41.6) |

1.13(0.70,1.83) |

0.62 |

1.61(0.95,2.74) |

0.08 |

| Indian |

87 |

64.4(51.0,75.9) |

37 |

35.6(24.1,49.0) |

1.20(0.62,2.34) |

0.59 |

1.58(0.79,3.12) |

0.20 |

| Others |

62 |

81.2(66.4,90.5) |

17 |

18.8(9.5,33.6) |

0.50(0.21,1.21) |

0.12 |

0.59(0.23,1.55) |

0.28 |

| Bumiputra Sabah & Sarawak |

289 |

68.5(60.0,75.9) |

146 |

31.5(24.1,40.0) |

1.00 |

|

1.00 |

|

| Marital status |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Single/widow/widower/divorcee |

797 |

60.0(54.6,65.1) |

527 |

40.0(34.9,45.4) |

1.86(1.46,2.38) |

<0.01 |

1.44(1.08,1.91) |

0.01 |

| Married |

1867 |

73.6(69.4,77.4) |

711 |

26.4(22.6,30.6) |

1.00 |

|

1.00 |

|

| Strata |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Urban |

1161 |

69.9(64.9,74.4) |

506 |

30.1(25.6,35.1) |

1.00 |

|

1.00 |

|

| Rural |

1505 |

67.5(62.9,71.8) |

733 |

32.5(28.2,37.1) |

1.12(0.82,1.51) |

0.48 |

0.99(0.77,1.28) |

0.92 |

| Education Level |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| No formal education |

430 |

54.0(48.0,59.9) |

357 |

46.0(40.1,52.0) |

3.93(2.33,6.62) |

<0.01 |

1.93(1.13,3.30) |

0.02 |

| Primary education |

1301 |

68.4(64.0,72.6) |

595 |

31.6(27.4,36.0) |

2.13(1.29,3.53) |

<0.01 |

1.19(0.72,1.95) |

0.49 |

| Secondary education |

722 |

73.2(67.1,78.5) |

236 |

26.8(21.5,32.9) |

1.70(1.09,2.64) |

0.02 |

1.24(0.82,1.87) |

0.31 |

| Tertiary education |

213 |

82.2(74.2,88.1) |

51 |

17.8(11.9,25.8) |

1.00 |

|

1.00 |

|

| Employment |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Employed |

751 |

75.7(70.9,80.0) |

273 |

24.3(20.0,29.1) |

1.00 |

|

1.00 |

|

| Non employed |

1915 |

67.2(63.1,71.0) |

966 |

32.8(29.0,36.9) |

1.53(1.23,1.90) |

<0.01 |

1.14(0.89,1.47) |

0.29 |

| Income |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Less than RM 1000 |

1557 |

62.6(58.1,66.9) |

911 |

37.4(33.1,41.9) |

2.60(1.52,4.45) |

<0.01 |

1.94(1.21,3.13) |

<0.01 |

| RM1000 – RM1999 |

619 |

74.4(69.4,78.9) |

215 |

25.6(21.1,30.6) |

1.50(0.88,2.55) |

0.14 |

1.28(0.80,2.06) |

0.30 |

| RM2000 – RM2999 |

261 |

83.4(77.6,88.0) |

56 |

16.6(12.0,22.4) |

0.87(0.49,1.54) |

0.62 |

1.24(0.82,1.87) |

0.31 |

| ≥RM3000 |

203 |

81.3(71.3,88.4) |

41 |

18.7(11.6,28.7) |

1.00 |

|

1.00 |

|

| Living status |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Living alone |

177 |

60.3(51.8,68.2) |

113 |

39.7(31.8,48.2) |

1.53(1.03,2.25) |

0.03 |

0.96(0.62,1.48) |

0.84 |

| Not living alone |

2489 |

69.8(65.9,73.5) |

1126 |

30.2(26.5,34.1) |

1.00 |

|

1.00 |

|

| Smoking status |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Non smoker |

1907 |

69.2(65.3,72.9) |

883 |

30.8(27.1,34.7) |

1.00 |

|

1.00 |

|

| Former smoker |

353 |

73.6(67.7,78.7) |

158 |

26.4(21.3,32.3) |

0.67(0.46,0.97) |

0.04 |

0.99(0.74,1.32) |

0.95 |

| Current smoker |

406 |

65.1(58.4,71.2) |

197 |

34.9(28.8,41.6) |

0.83(0.66,1.04) |

0.11 |

1.42(1.05,1.91) |

0.02 |

| *Multiple variable logistic regression analysis was performed after adjusted for other potential confounders in the model. No interaction was found among the independent factors (p-value >0.05). Classification of table showed the model correctly predicts 70.2% of the cases. Receiver operating characteristics curve analysis area under the curve was 0.64, p<0.001 |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).