3.2. Responses to the questionnaire

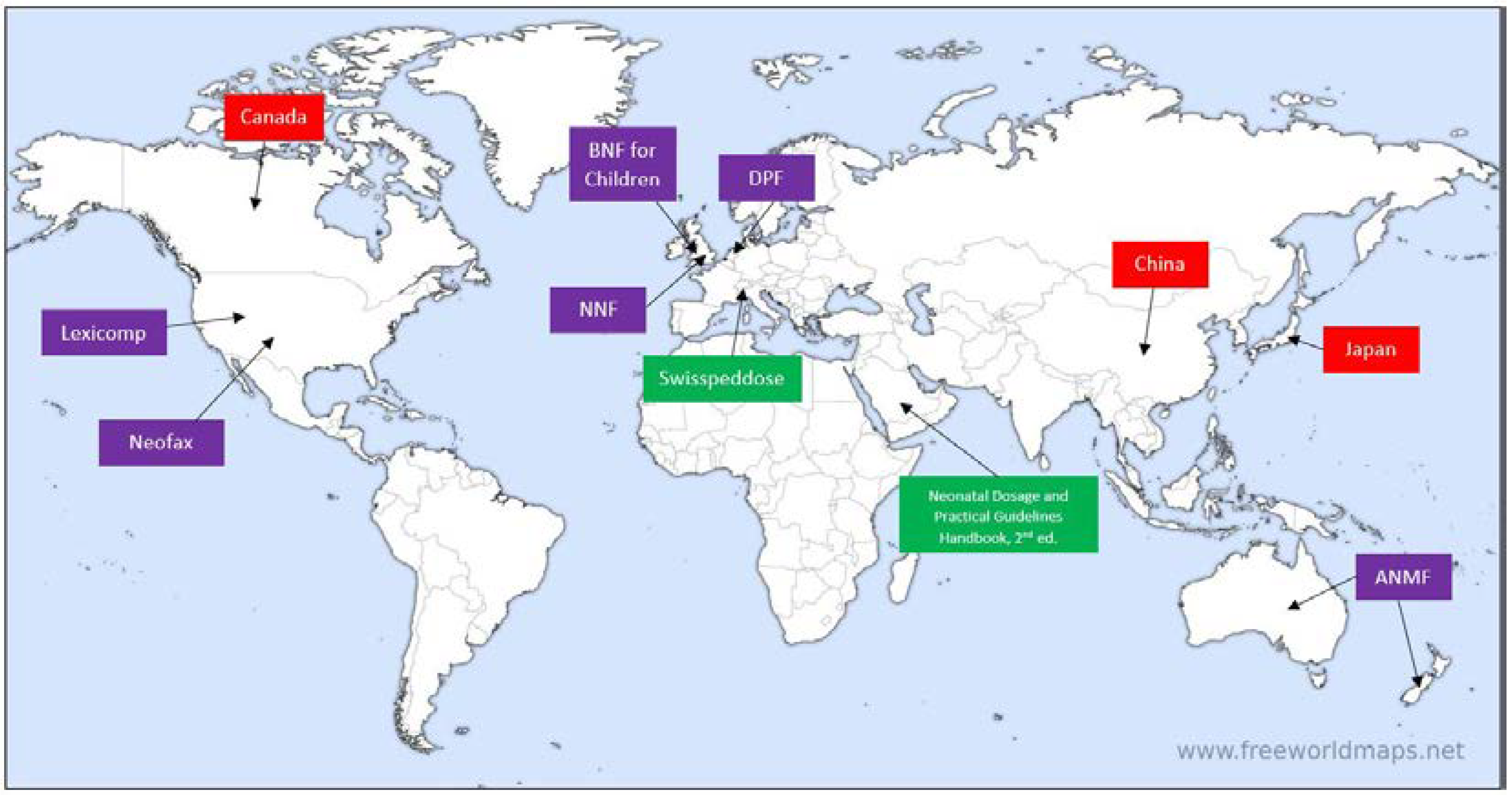

In total, responses were received from representatives of 6 neonatal formularies: the Australasian Neonatal Medicines Formulary (ANMF), the Dutch Pediatric Formulary (DPF) and its international affiliates, Pediatric and Neonatal Lexi-Drugs (Lexicomp), NeoFax (Micromedex), the British National Formulary for Children (BNF for Children) and Neonatal Formulary (NNF); as well as from Canadian, Chinese and Japanese key persons in the field of neonatal pharmacology, who were contacted.

All of these formularies can be considered secondary sources of information, as all distill and aggregate data and recommendations directly from primary sources, such as published papers and reviews dealing with the neonatal population. In contrast, there are differences in aspects related to development and support, workforce and -flow, publication and update, and presentation of monographs. We have summarized the key aspects of these variables for each of the formularies, based on authors’ responses to the questionnaire.

3.2.1. Australasian Neonatal Medicines Formulary (ANMF)

Development and support: The Australasian Neonatal Medicines Formulary (ANMF, previously known as Neomed) is an online formulary led by New South Wales (NSW) clinicians consisting of newborn specialists, pharmacists, nurses and other subspecialist groups, including infectious disease specialists, cardiologists, endocrinologists, gastroenterologists and neurologists, all from tertiary neonatal intensive care units. ANMF group also has international collaborators who are experts in neonatal pharmacology (KA, TY), who provide regular expert advice on all monographs before their release. ANMF standardizes medicinal treatment for (pre)term neonates by developing evidence-based consensus clinical guidelines for drugs used in this population. The project was commenced in late 2013 and as of December 2022, over 150 monographs relevant to the neonatal population have been developed. On average, 40 meetings are held every year to stay agile and dynamic and to keep the content up to date. In addition to digital versions publicly available online, printable versions in pdf formats are circulated by ANMF to all tertiary NICUs and major special care nurseries within Australia and New Zealand.

The project is supported by the Clinical Excellence Commission, NSW Ministry of Health and the Australian and New Zealand Neonatal Network (ANZNN). ANMF monographs are currently the only neonatal drug formulary endorsed by the NSW Ministry of Health and incorporated into electronic medical records in all NICUs statewide. ANMF steering group conducts weekly meetings using a structured agenda. In these 2-hour online meetings, new as well as existing monographs that require review and updating based on feedback from hospitals are discussed. ANMF does not receive sponsorship from any commercial or pharmaceutical industry, nor does it use advertising from any source.

Workforce and -flow: The ANMF team is comprised of a steering group and reference groups: the steering group is responsible for successful running of the project using a step-wise process of (1) identification of medications requiring a consensus formulary, (2) development of an evidence-based yet pragmatic paper-based and electronic formulary pertinent to Australasian region, (3) collaboration with all 29 tertiary NICUs across Australia and New Zealand and many special nurseries across Australia and New Zealand to achieve a majority consensus, (4) implementation of formulary in the clinical area, (5) feedback and evaluation within 3 months of implementation across Australia and New Zealand and revision as required, based on feedback, (6) regular review of formularies. The primary author is one of the steering group members of the ANMF, often a neonatologist but occasionally a steering group nurse or pharmacist will write the initial draft. Reference groups rigorously discuss the monograph in the weekly meetings, verify the accuracy and interpretation of the studies referenced in the draft and debate the applicability of the available evidence to the bedside practice. In addition, the Chair of the ANMF chooses an expert to contact for each monograph, as required. Thus, each monograph may take 6-8 weeks to complete. Consensus must be reached before content is approved and published.

ANMF protocols follow the National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) hierarchy of levels of evidence and grades for recommendations guide wherever applicable [

10].

Publication and update: Published protocols are available online in English in a searchable library within the ANMF website (

www.anmfonline.org). Content is reviewed periodically (1 to 5 years) according to ANMF review process, with current and next review date stated at the bottom of each monograph.

Monograph presentation: ANMF monographs are provided as PDF files under the ‘Clinical Resources’ section of the ANMF website. This section lists all available monographs in two groups – Current Monographs and New Monograph Releases, both searchable. The monographs have a standard structure, which includes version numbers and dates, scheduled date for review and a list of contributing authors. References are provided in-line, i.e., directly next to most statements, and are also collectively listed in the end of the monograph. One feature that stands out is that each monograph also provides an elaborate section titled ‘Evidence’, which summarizes the literature on important pharmacological aspects of the drug, including but not limited to efficacy, safety, pharmacokinetics, and more.

3.2.2. British National Formulary for Children (BNF for Children)

Development and support: British National Formulary for Children (BNF for Children) was created by the British National Formulary (BNF) in 2005 (BNF was first published in 1949 and served as a joint adults and children drug formulary until the emergence of BNF for Children). BNF for Children was developed originally by collaboration between BNF and Medicines for Children (MfC), an earlier British pediatric formulary first published in 1999 by RCPCH Publications Ltd. BNF for Children combined the knowledge gathered in MfC by British neonatal and pediatric experts from the Royal College of Paediatrics and Child Health (RCPCH) and the Neonatal and Paediatric Pharmacists Group (NPPG) with the expertise of BNF in publishing definitive drug formularies [

11]. BNF and BNF for Children are funded from sales made by the joint publishers, namely, the BMJ Publishing Group, the Pharmaceutical Press, and RCPCH Publications Ltd. BNF for Children is available in print (published annually) and as an online web-based platform, the latter being available either independently (for UK-based users) or as a part of MedicinesComplete® suite (for worldwide subscribers). It is also available as a mobile app in the UK.

Workforce and -flow: Content in BNF for Children is produced by an editorial team, with oversight provided by a Pediatric Formulary Committee (PFC), comprised of pharmacists, doctors, nurses and other healthcare professionals with pediatric background, as well as laypersons, and representatives of government departments, such as the Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (MHRA) and the UK Departments of Health. The work of the PFC is complemented by the Dental Advisory Group, which is responsible for information around dental and oral conditions, the Nurse Prescribers’ Advisory Group, responsible for information in the Nurse Prescribers’ Formulary, and a network of expert advisers from professional societies and advisory bodies.

The editorial team is comprised of experienced pharmacists, some with specific experience in pediatric practice. The team integrates information from a range of sources, including SmPCs, primary literature, consensus guidelines, reference sources (e.g., Martindale: The Complete Drug Reference), government and statutory information, NHS Prescription Services, and expert advice. Recommendations in BNF for Children are evidence-graded according to a five-level grading system from A to E, while evidence is graded by numerical levels from level 1++ (high quality meta-analyses, systematic reviews of randomized controlled trials, etc.) to level 4 (expert advice or clinical experience from respected authorities). Recommendations whose evidence base is weak or contradictory are assessed directly by the PFC and some are additionally subject to peer review before publication. DI is reviewed and updated both in response to new evidence from surveyed literature and proactively, with the aim to consider all recommendations for review every 3-4 years.

Publication and update: the print version of BNF for Children is published – and therefore updated – annually in September; the digital version of BNF for Children is updated monthly in accordance with observed updates to the relevant medical literature. In addition, the most clinically significant updates are collected and listed in a dedicated section of the content.

Monograph presentation (in MedicinesComplete®): BNF for Children monographs are uniformly structured and are divided into sections, and a sidebar is available for easy navigation. Notable monograph sections include (as appropriate): drug action, indications and dose (where neonatal dosing recommendations are specifically indicated, if available), unlicensed use, important safety information, cautions, interactions, side-effects, conception and contraception, pregnancy, breastfeeding, pre-treatment screening, monitoring requirements, directions for administration, prescribing and dispensing information, medicinal forms and other drugs in class. Moreover, each monograph has a digital object identifier (DOI) and the date of last update at the top of the monograph, and includes a link to the SmPC of the manufacturer from the Electronic Medicines Compendium (EMC) of the UK. No specific references are cited in the monograph.

3.2.3. The ‘Dutch’ Pediatric Formulary (DPF, also known as ‘Kinderformularium’)

Development and support: The ‘Dutch’ Pediatric Formulary (DPF) is a freely-available, government-financed, stand-alone online pediatric and neonatal formulary, whose target audience is all healthcare professionals providing, prescribing and administering drugs to children, i.e., physicians, pharmacists, nurses, pharmacy technicians. It was developed to provide dosing guidelines and accompanying DI based on best available evidence from registration data, investigator-initiated research, relevant professional guidelines, clinical experience and consensus [

12].

DPF is also available in country-specific versions in Germany, Austria and Norway with teams in each country adding country-specific information on licensing, availability of formulations and selecting those drugs, indications and age groups that are relevant to the clinical needs in the respective countries. The core pediatric and neonatal DI, however, is synchronized for all countries.

Workforce and -flow: Drugs that are licensed for use in children are included in the formulary by default. If a product is licensed for use in a certain age group, compliance with the SmPC is preferred unless there are strong arguments to deviate from it. If a European SmPC does not explicitly mention use in neonates, DPF considers the drug off-label for use in this age group. Drugs that are not authorized for the pediatric population (off-label use) are included in DPF if deemed necessary by pediatric professionals. For off-label use, a drug monograph is developed by a senior pharmacist using a structured framework, by assessing available scientific evidence that support dose recommendations, efficacy and related safety issues. No minimum level of evidence is required, but information regarding experimental use is not included. Available evidence is summarized in dose rationale (benefit-risk) documents and presented for peer-review to a multidisciplinary editorial board consisting of pediatricians with diverse specialties, clinical pharmacologists, pharmacists, pediatric hospital pharmacists and primary care physicians. Special expert groups are available for neonatology, nephrology and pharmacokinetic model informed dosing, and if deemed necessary, other experts may be consulted. The drugs monographs are published online in the respective DPF platforms of the Netherlands, Germany, Austria and Norway, including citations and references. The full dose rationale summaries are not published, but are available upon request.

A dedicated project to further develop the neonatal dosing regimens (NEODOSE) has recently been reported [

13].

Publication and update: Monographs require unanimous approval by the editorial board prior to publication. Following publication, they are updated every 5 years, or more frequently as new evidence emerges. Changes are indicated within the monographs and are also communicated to users in the form of monthly updates and through learned societies.

Monograph presentation: DPF Monographs are comprised of “best-evidence”, which is scientific evidence on PK, efficacy and safety of the drug, complemented with clinical expertise and extrapolation (preferably using published PK data) where published evidence is limited, as is common in neonatal clinical pharmacology. Monograph content includes common data sections such as drug properties (PK and PD), licensing information, dosing, available formulations including excipients information, dosing in renal impairment (applicable above 3 months of age), side effects, warnings and precautions, contraindications, drug interactions, references and monograph history of changes.

3.2.4. NeoFax

Development and support: NeoFax is a U.S.-based neonatal formulary, first published as a printed book in 1987 and updated annually. Thomson corporation acquired NeoFax in 2007 and discontinued the print edition in 2011, opting for digital delivery exclusively to increase access and frequency of updates. Prior to acquisition, several localized editions were produced, e.g., a German edition titled “NeoFax: Arzneimittelhandbuch für die Neonatologie” (Gedon & Reuss, 2003), a Brazilian edition titled “NeoFax 2006: guia de medicações usadas em recém-nascidos” (São Paulo: Atheneu, 2006) and a Polish edition titled “NeoFax®: leki w neonatologii” (Ośrodek Wydawnictw Naukowych, 2006), among others, but none are still maintained and printed. NeoFax is currently available as an online web-based solution and a native mobile application, both in English only. The content includes neonatal-focused drug monographs, infant formula and human milk fortifier nutritional information (only for formulations available in the United States), as well as age- and indication-specific drug dosing calculators.

NeoFax’s target audience is healthcare professionals working in NICU settings, who may access NeoFax as a stand-alone solution or as part of a larger decision support system called Micromedex® offered by Merative. Additional non-neonatal-specific tools that are available through Micromedex complement NeoFax, e.g., a drug interaction module, an IV compatibility screening tool, toxicology and reproductive effects content and pediatric DI (a module similar to NeoFax but focusing on infants and children).

Workforce and -flow: Monographs are created or updated through weekly surveillance of published neonatal literature and are written and peer-reviewed by internal pharmacist editors, while a final review for new neonatal monographs and new off-label indications is done by an external peer reviewer with neonatal/pediatric expertise. The editorial team also tracks U.S. regulatory product information. If this contains neonatal-specific information, it will be incorporated into the monograph where appropriate. Where dosing recommendations from product information and published literature differ, both will usually be included in the monograph. Extrapolation from pediatric studies is not implemented unless it has been published in the available literature.

Publication and update: NeoFax is updated and published monthly, unless new safety or practice-changing information becomes available, in which case it is updated outside of the regular publishing schedule. Updates are communicated to users via a dedicated section titled ‘What’s New’, which lists new drug monographs, updated monographs, and drugs with dosage recommendation changes.

Monograph presentation: Monographs in NeoFax are divided into sections and subsections as follows (section titles appear between single quotations marks, subsections in parentheses): ‘Dosing/Administration’ (Dose, Uses, Administration), ‘Medication Safety’ (Contraindications/Precautions, Adverse Effects, Black Box Warning, Solution/Drug Compatibility, Monitoring), ‘Mechanism of Action/Pharmacokinetics’ and ‘About’ (Special Considerations/Preparation, References). Monographs do not specify time of latest update or a scheduled time for review. References are provided next to most statements, and are also listed together in a separate subsection.

3.2.5. Neonatal Formulary (NNF)

Development and support: ‘Neonatal Formulary – Drug Use in Pregnancy and the First Year of Life’ is a British formulary in the form of a printed book and an online digital version, currently authored by Dr. Sean Ainsworth, and published by Oxford University Press. The NNF began life in 1978 as a loose-leaf A4 reference folder at the Hospital for Sick Children in Newcastle upon Tyne. Written by Dr. John Inkster (Consultant Paediatric Anaesthetist) and Dr. Edmund Hey (Consultant Paediatrician), the formulary was updated regularly but retained the same format and basic layout. Until 1989, monographs reflected practice in the two neonatal units in Newcastle but then began to draw on accumulated experience throughout the Northern Regional Health Authority when it became known as the ‘Northern Neonatal Pharmacopeia’. Small pocket book versions were published and used in neonatal units in that Health Authority in 1991 and 1993. In 1996, the 9th edition of this pharmacopeia found a national UK-wide audience when it was published by the BMJ Publishing Group as the first edition of the ‘Neonatal Formulary’. Monographs then began to reflect wider use across the UK and other countries. In 2004, publishing moved to Blackwell Publishing before moving to Oxford University Press in 2020.

This formulary offers both prenatal and neonatal DI to provide a narrative of drug effects from fetal to neonatal state. Thus, unlike most neonatal formularies, NNF also offers advice across every critical stage in the life of a neonate, starting with in utero exposure (placental transfer, teratogenicity), through safety in breastfeeding, to postnatal pharmacotherapy. It may be worth noting here that in many countries DI related to pregnancy and lactation is provided by dedicated teratology information services, and therefore is not included in most neonatal formularies.

Workforce and -flow: The data provided in NNF rely on information collected from UK approved SPCs and published literature (including Cochrane reviews where appropriate), and, where no substantial data can be found, on professional expertise of local and overseas collaborators. Special attention is given to renal and hepatic function and their effects on drug exposure, toxicity due to overdosing and the effects of non-pharmacologic treatments such as therapeutic hypothermia (TH) on drug PK, where applicable.

Monograph presentation: NNF is divided into 3 parts: part 1 contains general information about clinical neonatal pharmacotherapy, e.g., adverse reactions, PK/PD, dosing, administration, storage, legal aspects (licensing and prescribing), excipients. These sections provide summaries of important and unique concepts for NICU settings. Part 2 contains individual drug monographs for drugs commonly used in NICUs, in which specific DI is provided in specific subsections, e.g., ‘Use’, ‘Pharmacology’, ‘Fetal and infant implications of maternal treatment’ and ‘Supply’. Additional subsections are present as applicable, such as antidotes, effects of TH, or therapeutic drug monitoring (TDM), making NNF monographs non-uniform in structure. Certain monographs have additional online-only content available at the website of the publisher (see

Table 1). The availability of such content is clearly marked at the top of the monograph, along with the title of the

Supplementary Material. Part 3 is dedicated to exposure to maternal medications

in utero, during labor or in the postpartum period, and provides information on specific aspects of drug safety of maternal medications such as placental transfer, teratogenicity and drug excretion into breastmilk. The information about each drug in this section is concise and abridged, but key references are given for the reader.

Publication and update: the printed version of NNF is being updated every couple of years and a new edition is published and made available for purchase. Online

supplementary material is updated whenever significant changes in dosing occur.

3.2.6. Pediatric and Neonatal Lexi-Drugs (Lexicomp)

Development and support: Lexicomp is a comprehensive DI database powered by Wolters Kluwer®, a global information services company, containing both adult and pediatric/neonatal drug monographs (the latter may be found under the ‘Pediatric and Neonatal Lexi-Drugs’ module) and other specific DI modules (e.g. Trissel’s IV Compatibility, Interactions, Drug I.D., Patient Education and more). ‘Lexicomp Pediatric & Neonatal Dosage Handbook’ was first published in print in 1992 and continues to this day (November 2022 saw the 29th edition in print), while in 2005 the content became available online as a web-based platform. Lexicomp is currently available as a web-based platform, a mobile application and in print. While DI itself is available in English, the online user interface is available in 18 languages.

Neonatal DI is part of the pediatric database and includes a wealth of information, such as dosing information, pregnancy and lactation information (including Briggs’ Drugs in Pregnancy and Lactation, which provides a separate monograph for pregnancy and lactation information on top of information available in Lexicomp), usual IV concentrations, drug interactions, IV compatibility and more. It is designed to support all types of neonatal healthcare professionals, i.e., physicians, nurses, pharmacists, students and others, in inpatient, outpatient and retail pharmacy settings with details on local preparations in a variety of countries and regions around the world. Lexicomp is subscription-dependent, available to individuals and institutions, either as a standalone platform or as part of other information platforms, such as Wolters Kluwer’s UpToDate. It should be noted that certain materials are made widely available for free, usually in response to global healthcare emergencies (e.g., COVID-19).

Workforce and -flow: Pediatric and Neonatal Lexi-Drugs employs a multi-step, peer-reviewed editorial process by in-house pediatric/neonatal residency trained clinical pharmacists and an external neonatal advisory panel, which includes neonatologists and neonatal clinical pharmacists (a detailed list is available online [14]). Pubmed searches are conducted according to specific terms and keywords, and results are evaluated according to an adapted grading system for design, methodology, statistical analysis, results and overall quality of the paper before it is deemed appropriate for inclusion in the drug monograph. Ultimately, best evidence is synthesized from peer-reviewed literature, published clinical guidelines, expert opinions of neonatal practitioners, and any applicable manufacturer labeling. No extrapolation of older children/adult PK data is employed in the formulation of drug dosing recommendations. If available data in a certain aspect are vague or limited, this is clearly indicated adjacently to those data.

Monograph presentation: neonatal DI is provided as part of the Pediatric and Neonatal Lexi-Drugs drug monograph. Drug monographs in Lexicomp are uniformly structured, and include a sidebar containing an outline of the monograph for easy navigation and a main view presenting the various aspects of DI, including dosing recommendations according to indications, preparation and administration instructions, contraindications, adverse events, warnings/precautions, monitoring information, pharmacokinetics (usually adult data unless otherwise noted) and many other fields – all indicate neonatal DI where available. Citations appear in-line and are also grouped together in the references section of the monograph. The PubMed ID (PMID) number is included and leads to the appropriate Pubmed abstract, with external links as well. Boxed warnings (also known as “black box” warnings) are included in the Warnings section per the wording in the U.S. manufacturer labeling.

Publication and update: new content is released online on a daily basis and is available to the user immediately. As new evidence becomes available, it is processed and prioritized based on its importance to healthcare providers. Major updates are implemented immediately (e.g., practice-changing evidence, new medications), while minor updates are published in a timely manner as possible. Updates to users are made through monthly newsletters sent by the marketing department or may be sent by the parent formulary Lexicomp is part of at a specific institution.

3.4. Comparison of Neonatal Formularies

To complement the above narratives of the six neonatal formularies reviewed here – NeoFax, ANMF, DPF, NNF (print version, 8

th edition), Pediatric and Neonatal Lexi-Drugs and BNF for Children (online version, through MedicinesComplete) – a side-by-side comparison of the formularies is presented in

Table 2. This comparison lists the main aspects of the framework and organization of different drug formularies in general, such as the number of available monographs (at the time of writing), listing of references, type of funding etc., as well as aspects that are unique to neonatal drug formularies, such as differentiation in DI between term and preterm neonates, neonatal adverse effects, specific monitoring parameters etc. The table has been constructed based on data provided by formularies’ authors and data gathered from each formulary using a structured data extraction tool [Document S2] for the 10 most commonly used drugs in NICUs in the United States, according to a recent paper by Stark et al. (2022) [

9] – ampicillin, gentamicin, caffeine citrate, poractant alfa, morphine, vancomycin, furosemide, fentanyl, midazolam, and acetaminophen. The full data extracted for these top 10 drugs can be found in the

Supplementary Material [Document S3 and Document S4].

To further illustrate differences and similarities between the examined neonatal formularies, the dosing sections of 3 common drugs in the NICU – caffeine citrate, morphine and gentamicin – were compared and dosing recommendations were subsequently extracted along with directly-related comments (

Table 3). To avoid cluttering and excess of information, only dosing recommendations for the main indication of each drug were extracted. An attempt was made to maintain original wording as much as possible on one hand, while formatting all dosing recommendations as uniformly as possible on the other.

Table 2.

Content Availability and Organization Comparison Between Neonatal Formularies.

Table 2.

Content Availability and Organization Comparison Between Neonatal Formularies.

| Parameters |

Neofax |

ANMF |

DPF |

NNF |

Pediatric and Neonatal Lexi-Drugs |

BNF for Children |

| General characteristics |

Pediatric and Neonatal formulary or neonatal only |

Neonatal only (a parallel module is available for pediatric patients) |

Neonatal |

Neonatal and pediatric |

Neonatal and pediatric (infancy) |

Neonatal and pediatric |

Neonatal and pediatric |

| Number of drug monographs included overall |

304

(pediatric: 804) |

182 |

884 |

265 (covering over 300 unique drugs or drug combinations) |

1460 (376 with neonatal dosing) |

1031 |

| Number of monographs with DI for term neonates |

304 |

182 |

252 |

N/A |

360 |

218 |

| Number of monographs with DI for preterm neonates |

112 |

182 |

73 |

N/A |

336 |

N/A |

| Are references and citations included? |

Yes, in-line and collectively under a ‘References’ section |

Yes, in-line and collectively under a ‘References’ section |

Yes, in-line and collectively under a ‘References’ section |

Yes, collectively in the end of the monograph |

Yes, in-line and collectively under a ‘References’ section |

No |

| Is communication between users and authors possible? |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes,

contact form “suggestions for improvement” is included in each monograph, delivered to editorial team |

Yes (through email to publishers) |

Yes, via online customer support |

Yes, clinical content enquiries can be made via email |

| Peer-reviewed |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

| Funded by public/not for profit or private/commercial |

Commercial |

Public/not for profit |

Public/not for profit |

Commercial |

Commercial |

Commercial |

| Independent from pharmaceutical industry |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

| Are commercial products listed? |

Yes (available formulations and strengths) |

Yes |

Yes (available formulations and strengths are listed) |

Yes |

Yes, in Brand Names sections for US, Canada and International (where appropriate) |

Yes |

| Organization |

Differentiation between preterm and term patients? |

Yes, usually under the ‘Dose’ section |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes, usually under the ‘Dosing: Neonatal’ section |

Yes |

| Categories used for preterm age groups (birthweight, PNA, PMA, current weight) |

Yes, based on the evidence; usually under the ‘Dose’ section |

Where appropriate and indicated |

If available from literature: birthweight; PNA; PMA, PCA |

Where appropriate and indicated |

Where appropriate and indicated; under the ‘Dosing: Neonatal’ section |

Where appropriate. Usually based on weight. Corrected gestational age |

| Dosing recommendations are differentiated by routes of administration? |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes, every dosing recommendation is associated with route(s) of administration |

Yes |

|

Dosing Recommendations

|

Dosing recommendations are differentiated by indication? |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes, every dosing recommendation is associated with indication(s) |

Yes |

| Renal dosage adjustment (if applicable) |

Yes, under the ‘Dose’ section |

Yes, since 2020 |

Yes, specific section, including advice on adjustment based on AKI for > 3 months of age. Dose adjustment for neonatal maturation included in neonatal dosing recommendation |

Yes |

Yes, under the ‘Dosing: Neonatal’ section |

Yes |

| Hepatic dosage adjustment (if applicable) |

Yes, under the ‘Dose’ section |

Yes, since 2020 |

If applicable and available under ‘Warnings and Precautions’ section |

Yes |

Yes, under the ‘Dosing: Neonatal’ section |

Yes |

| Other dosage adjustments (if applicable) |

Yes, under the ‘Dose’ section (e.g., TH, ECMO) |

Yes, since 2020 |

If available from literature (TDM, ECMO, Hypothermia, obesity, pharmacogenetics) |

Yes |

Yes, under ‘Dosing: Neonatal’, as Notes at the top |

Yes |

| Are preparation instructions available? |

Yes, under the ‘Special Considerations/ Preparation’ section |

Yes |

No |

Yes |

Yes, under the ‘Preparation for Administration: Pediatric’. There is a ‘Extemporaneous Preparations’ section for bulk compounding of oral preparations, plus access to Trissel’s IV Compatibility |

Yes |

| Preparation |

Are stability data provided (if applicable)? |

Yes, under the ‘Special Considerations/ Preparation’ section |

Yes |

No |

Yes |

Yes, in the ‘Storage/Stability’ section, plus access to Trissel’s IV Compatibility |

Yes |

| Optimal concentration of preparation (if applicable) |

Yes, under the ‘Special Considerations/ Preparation’ section |

Yes |

No |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

| Maximum concentration of preparation (if applicable) |

Yes, under the ‘Special Considerations/ Preparation’ section |

Yes |

No |

No |

Yes |

Yes |

| Is method of administration indicated? |

Yes, under the ‘Administration’ section |

Yes |

Yes, under the ‘Dosages’ section |

Yes |

Yes, under the ‘Administration: Pediatric’ section |

Yes |

| Administration and Monitoring |

Are monitoring advice and parameters available? |

Yes, under the ‘Monitoring’ section |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes, under the ‘Monitoring Parameters’ and ‘Reference Range’ sections |

Yes |

| If monitoring advice and parameters are indicated, are specific neonatal warnings and precautions mentioned (if applicable)? |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes, if available from literature or clinical expertise |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

| Drug-drug interactions mentioned? |

No; an external drug-drug interactions module is available to Micromedex subscribers |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes, under the ‘Drug Interactions’ section and in a separate module |

Yes |

| Pharmacological Data |

Adverse effects mentioned? |

Yes, under the ‘Adverse Effects’ section; frequency is provided where available |

Yes |

Yes; frequency is provided where available |

Yes; a dedicated section is included only in certain monographs |

Yes, under the ‘Adverse Reactions’ section; frequency is provided where available |

Yes; frequency is provided where available |

| If adverse effects are mentioned, are specific neonatal effects mentioned? |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes, If available from literature or clinical expertise |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

| Are notable excipients mentioned? |

Yes, if applicable, under the ‘Contraindications/precautions’ section |

Yes, since 2020 |

Yes (if available from product info, including concentration) |

Yes |

Yes, under the ‘Dosage Forms: US’ and/or ‘Dosage Forms: Canada’ sections |

Yes |

| Neonatal Pharmacokinetic data available? |

Yes, under the ‘Pharmacology’ section |

Yes, wherever available |

Yes, if available from literature |

Yes |

Yes, under the ‘Pharmacokinetics (Adult data unless noted)’ section |

Yes, often under the monitoring section |

| Transparency on how information is compiled |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

| |

Information can be verified by references/source documentation |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

| |

Extrapolation from older pediatric age groups or adults based on available data |

No (would accept published literature with extrapolated data) |

Yes |

Yes |

N/A |

Evidence for dosing provided with inline citations |

Yes |

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Out of the 6 examined neonatal formularies, 3 have a specific focus on neonatology neonatal-specific (ANMF, NeoFax and NNF), whereas the other 3 provide pediatric DI as well. Pediatric and Neonatal Lexi-Drugs has the largest number of monographs overall (1,460), followed by BNF for Children (1,031), DPF (884), NeoFax (304, neonatal only), NNF (265) and ANMF (182). The number of neonatal-specific monographs was not obtainable from all formularies, but they range between slightly less than 200 and over 350 neonatal-specific monographs.

Almost all formularies provide specific references for DI, both in-line and collectively in a designated section of the monograph. References are usually from primary literature and/or product information (SmPC). Only BNF for Children does not provide references, but does offer a direct link to the British SmPC in the Electronic Medicines Compendium (emc), on which at least some of the DI is based (of note, the emc is a freely available resource for DI on medicines licensed for use in the UK, unrelated to BNF for Children). All formularies have been found to be peer-reviewed as part of their validation process, and all are independent from the pharmaceutical industry. Commercial products are listed in all formularies, with each formulary listing some or all of the commercial products available in the country/region it targets.

With regard to organization of information, all formularies differentiate between preterm and term infants, and use conventional and accepted neonatal terminology to differentiate between neonatal subpopulations, as age and birthweight are usually a good indication of the level of maturation of the patient, from which physiological status (e.g., hepatic and renal function, lung and gastrointestinal maturity etc.) – which affects PK parameters and therefore expected level of response to drug therapy – is derived.

Additionally, all formularies denote specifically the route of administration appropriate for each dosing recommendation, and all provide hepatic and renal dosage adjustments as appropriate, as well as other types of dosage adjustments required by altered physiological status (e.g., therapeutic hypothermia, ECMO).

Regarding the drug preparation aspect, all formularies beside DPF offer specific information and guidance on how to best prepare the drug, ranging from manufacturer’s instructions to extemporaneous preparations derived from primary literature. However, some formularies provide more data than others regarding preparation information. Thus, as mentioned, DPF does not provide preparation data at all, while ANMF monographs published since 2020 do provide optimal and maximal concentrations where applicable (notably, no such information was identified for the 10 studied drugs [Document S3 and S4]), and NNF sometimes provides optimal concentrations but no maximal concentrations for any of the 10 drugs studied.

All formularies provide information on the method of administration, i.e., duration of infusion, distance from feeding etc. and all formularies provide monitoring advice, usually in a dedicated section, which details monitoring parameters, suggested timetables and desired plasma levels where appropriate.

All formularies provide drug interactions information and adverse effects in dedicated sections (NNF monographs are inconsistent regarding the inclusion of such section), save for NeoFax, which does not include a drug interactions section within each monograph (a drug interactions module is available separately to Micromedex subscribers). All formularies save for ANMF also provide frequencies of adverse effects where available, either in percentages or categorically.

All formularies mention notable excipients with potential effects on neonates. PK data is also provided in all formularies, although not in the same manner: NeoFax, ANMF and NNF provide only neonatal PK data where available, DPF provides PK data in older children, if available, as a comparison for neonatal data, and Pediatric and Neonatal Lexi-Drugs provides neonatal and pediatric PK data where available, and where unavailable, adult PK data is provided.

Table 3.

Comparison of Dosing Recommendations for Caffeine Citrate, Morphine and Gentamicin.

Table 3.

Comparison of Dosing Recommendations for Caffeine Citrate, Morphine and Gentamicin.

| Drug Name |

ANMF |

BNF for Children |

DPF |

Pediatric and Neonatal Lexi-Drugs |

NeoFax |

NNF |

Caffeine citrate

Indication: Apnea of Prematurity |

Caffeine citrate:

Route: IV, Oral

LD: 20 mg/kg

MD: 10 mg/kg (range 5−20 mg/kg) daily

Post-op apnoea (single dose): 10 mg/kg

Caffeine Base:

Route: IV, Oral

LD: 10 mg/kg

MD: 5 mg/kg (range 2.5−10 mg/kg) daily

Post-op apnoea (single dose): 5 mg/kg

Comments:

● Maintenance dose may be increased or decreased as per the clinical need. |

Caffeine citrate:

Neonate:

Route: IV, Oral

LD: 20 mg/kg

MD: 5 mg/kg once daily, started 24 hours after the loading dose

Comments:

● Dose equivalence and conversion:

Caffeine citrate 2 mg ≡ caffeine base 1 mg

● MD above 20 mg/kg/day can be considered if therapeutic efficacy is not achieved |

GA < 37 weeks

Caffeine citrate:

Route: IV, Oral

LD: 20 mg/kg/day

MD: 5-10 mg/kg/day

Caffeine base:

Route: IV, Oral

LD: 10 mg/kg

MD: 2.5-5 mg/kg/day

Comments:

● The injection solution can be administered orally. |

Manufacturer’s labeling: Preterm neonates:

Route: IV

LD: 20 mg/kg caffeine citrate as a one-time dose

Route: IV, Oral

MD: 5 mg/kg/dose caffeine citrate once daily, beginning 24 hours after loading dose

Alternate dosing: GA < 32 weeks:

Route: IV

LD: 20-40 mg/kg caffeine citrate

Route: IV, Oral

MD: 5-20 mg/kg/dose caffeine citrate once daily starting 24 hours after the loading dose

Comments:

● loading doses as high as 80 mg/kg of caffeine citrate have been reported, but should be utilized with caution.

● Dose expressed as caffeine citrate; caffeine base is ½ the dose of the caffeine citrate |

FDA-Approved Dosage:

Route: IV, Oral

LD: 20-25 mg/kg of caffeine citrate IV over 30 minutes or orally.

Route: IV, Oral

MD: 5-10 mg/kg/dose of caffeine citrate IV slow push or orally every 24 hours

Off-label Dosage: GA 22-28 weeks:

Route: IV

LD: Median, 20 mg/kg IV (range, 19-23 mg/kg)

Route: IV, Oral

MD: Median, 8 mg/kg/day (range 5-10 mg/kg/day)

Comments:

● May consider an additional loading dose and higher maintenance doses if able to monitor serum concentrations. |

Route: IV, Oral

LD: 20-25 mg/kg of caffeine citrate IV or orally.

MD: 5 mg/kg IV or orally once every 24 hours

Comments:

● As the baby matures it may be necessary to increase the dose of caffeine citrate by an additional 1 mg/kg every one to two weeks to ensure that the minimal caffeine concentrations (15-20 mg/L) that are recommended for treatment of apnoea or prematurity are maintained.

● Drug equivalence: There is 1 mg of caffeine base in 2 mg of caffeine citrate.

|

Morphine

Indication: analgesia |

Route: PO

Starting dose: 50–200 microgram/kg every 3–6 hours.

Route: IV bolus

50 mcg/kg (maximum recommended 100 mcg/kg) every 4 hours.

Route: continuous IV infusion

Range: 5-40 mcg/kg/hour:

Ventilated infants or after surgery:

● PNA 0-7 days:

Starting dose: 10 mcg/kg/hour

Range: 5-40 mcg/kg/hour

● PNA 8-30 days:

Starting dose: 15 mcg/kg/hour

Range: 5-40 mcg/kg/hour

● PNA 31-90 days:

Starting dose: 20 mcg/kg/hour

Range: 5-40 mcg/kg/hour

Comments:

Infants after cardiovascular surgery may need a lower starting dose and be titrated to clinical response. |

Route: SC

Dose: Initially 100 micrograms/kg every 6 hours, adjusted according to response.

Route: IV

Dose: 50 micrograms/kg every 6 hours, adjusted according to response, dose to be administered over at least 5 minutes, alternatively (by intravenous injection) initially 50 micrograms/kg, dose to be administered over at least 5 minutes, followed by (by continuous intravenous infusion) 5–20 micrograms/kg/hour, adjusted according to response. |

Route: PO

Term Neonates

Dose: 0.3-0.6 mg/kg/day in 6 doses.

Route: Rectal

Dose: 0.6–1.2 mg/kg/day in 6 doses.

Route: IV

Premature neonates Gestational age < 37 weeks and term neonates:

Starting dose: 50-100 mcg/kg/dose over 60 minutes

MD: 3-20 mcg/kg/hour, as continuous infusion.

Administer under supervision.

If the effect is insufficient, the hourly dose can be given as a bolus injection, increasing gradually.

|

Route: PO

Dose: 0.05-0.1 mg/kg/dose every 4 to 8 hours as needed.

Route: IM, IV (preferred), SC:

Initial: 0.05-0.1 mg/kg/dose every 4 to 8 hours as needed

Comment: use lowest effective dose and titrate carefully as clinically indicated.

Route: continuous IV infusion:

Preterm and term neonates:

Initial: 0.01 mg/kg/hour (10 mcg/kg/hour); titrate carefully based on patient response and considering benefits and risk of additional opiate exposure

Comments:

● Continuous IV infusion: use caution if patient at risk of hypotension; some experts recommend not using in neonates with GA <27 weeks.

|

Route: IV, IM, SC

Dose: 0.05-0.2 mg/kg per dose. Repeat as required (usually every 4 hours).

Route: IV continuous infusion

LD: 0.1 mg/kg

MD: 0.01 mg/kg/hour

Comment:

postoperatively may be increased further to 20 mcg/kg/hour. |

Short term pain relief:

Route: PO

Dose: 200 mcg/kg

Route: SC, IV (preferred)

Dose: 100 mcg/kg

Comments:

● Rapid intravenous administration does not cause hypotension but may cause respiratory depression.

● A further 50 mcg/kg/dose can usually be given after 6 hours without making ventilator support necessary.

Severe or sustained pain:

Route: IV

LD: 200 mcg/kg

MD: 20 mcg/kg/hour

Comments:

● Provide ventilatory support.

● While this [dosage regimen] will usually control even severe pain in the first 2 months of life, providing a plasma morphine level of 120-160 ng/mL, treatment has to be individualized.

● Staff needs discretion to give further 20 mcg/kg bolus up to once every 4 hours to control any ‘break-through’ pain. |

Gentamicin

Indication: gentamicin-susceptible infection, neonatal sepsis |

Route: IV, IM (only if IV access is not available)

Dose: 5 mg/kg

Dosing interval depends on GA:

● < 30+0 weeks: 48 hourly

● 30+0 – 34+6 weeks: 36 hourly

● ≥ 35+0 weeks: 24 hourly

● Concurrent cyclo-oxygenase inhibitors (indomethacin or ibuprofen): Extend dosing interval by 12 hours

● Therapeutic hypothermia: 36 hourly

Comments:

● Subsequent dosing interval is based on gentamicin concentration at 22 hours after the administration of the second dose (table provided) |

Route: slow IV injection or IV infusion

Dose: 5 mg/kg

Dosing interval depends on age:

● Up to 7 days: every 36 hours, to be given in an extended interval dose regimen.

● 7-28 days: every 24 hours, to be given in an extended interval dose regimen.

* Note: BNF for Children provides more information on gentamicin concentrations and dose adjustment in the ‘Monitoring Requirements’ section. |

Route: IV

Dose:

● GA < 32 weeks and PNA 0-7 days: 5 mg/kg/48 hours

● GA 32-37 weeks and PNA 0-7 days: 5 mg/kg/36 hours

● Preterms, PNA 1-4 weeks: 4 mg/kg/day

● Term neonates: 4 mg/kg/day

● Therapeutic hypothermia:

GA ≥ 36 weeks and PNA 0-1 days:

5 mg/kg/36 hours

Comments:

● Dose should be adjusted according to plasma levels

● It is recommended to determine plasma levels before the second dose of gentamicin

● Empiric use does not necessitate plasma levels determination

|

Route: IV, IM

Dose:

● GA < 30 weeks and PNA ≤ 14 days: 5 mg/kg/dose every 48 hours

● GA < 30 weeks and PNA ≥ 15 days: 5 mg/kg/dose every 36 hours

● GA 30-34 weeks and PNA ≤ 10 days: 5 mg/kg/dose every 36 hours

● GA 30-34 weeks and PNA 11-60 days: 5 mg/kg/dose every 24 hours

● GA ≥ 35 weeks and PNA ≤ 7 days: 4 mg/kg/dose every 24 hours

● GA ≥ 35 weeks and PNA 8-60 days: 5 mg/kg/dose every 24 hours

Comments:

● Determination of dosing interval requires consideration of multiple factors including concomitant medications (e.g., ibuprofen, indomethacin), history of birth depression, birth hypoxia/asphyxia, and presence of cyanotic congenital heart disease.

● Dosage should be individualized based upon serum concentration monitoring.

● Higher doses and different dosing intervals may be required to achieve target concentrations if MIC ≥1 mg/L |

Route: IV

Dose:

● PMA ≤ 29 weeks and PNA 0-7 days: 5 mg/kg/48 hours

● PMA ≤ 29 weeks and PNA 8-28 days: 4 mg/kg/36 hours

● PMA ≤ 29 weeks and PNA ≥ 29 days: 4.5 mg/kg/24 hours

● PMA 30-34 and PNA 0-7 days: 4.5 mg/kg/36 hours

● PMA 30-34 and PNA ≥ 8 days: 4 mg/kg/24 hours

● PMA ≥ 35 weeks: 4 mg/kg/24 hours

Comments:

● Renal function and drug elimination are most strongly correlated with PMA

● PMA is the primary determinant of dosing interval, with Postnatal Age as the secondary qualifier. |

Route: IV, IM

Dose: 5 mg/kg when GA < 44 weeks, thereafter 7 mg/kg

Dosing interval:

● < 30 weeks: every 48 hours

● 30–36 weeks: every 36 hours

● Term infants: every 36 hours in the first week of life, thereafter every 24 hours

Comments:

● Extend the dosing interval if the renal function is poor.

● It may be helpful to measure the level 24 hours after the first dose is given.

● Individualized treatment: a strategy to individualize treatment in very immature infants (≤ 28 weeks gestation) may be followed by measuring the serum gentamicin level 22 hours after a single dose of 5 mg/kg. The timing to the next dose is then calculated according to the level (table provided). |

Dosing recommendations for caffeine, morphine and gentamicin illustrate some similarities and differences between the formularies.

Caffeine usually appears in commercial products as caffeine citrate. All formularies indicate dosing both for caffeine citrate and caffeine base as well as the proportion between them (2:1), and always clearly indicate if the recommended dosing is for the citrate salt or the base compound. Regarding the dosing recommendations themselves, they are fairly consistent across formularies: all formularies mention the need for a loading dose (LD), usually 20 mg/kg of caffeine citrate, although some formularies (NeoFax, NNF) allow for LD of up to 25 mg/kg. Additionally, both Pediatric and Neonatal Lexi-Drugs and NNF provide information for even higher LD (up to 80 mg/kg), and Pediatric and Neonatal Lexi-Drugs states that such dosage should be used with caution, detailing adverse effects observed under such dosage, while NNF mentions such LD not for treatment of apnea of prematurity but for facilitating extubation in neonates born under 30 weeks of gestation. Maintenance doses (MD) range between 5 and 10 mg/kg/day of caffeine citrate across formularies. ANMF, BNF for Children, NeoFax and NNF also recommend adjusting MD based on clinical need. All formularies provide both routes of administration (IV, oral), while BNF for Children, DPF and NNF state explicitly that the injection solution may be administered orally (oral preparations of caffeine, either commercial or extemporaneous, are widely available). Only Pediatric and Neonatal Lexi-Drugs and NeoFax address premature neonates explicitly with specific age-based dosage recommendations.

Morphine may be given to neonatal patients through several routes of administration. All formularies indicate the oral and IV route, which are the most common routes. However, subcutaneous injection is also possible according to BNF for Children, Pediatric and Neonatal Lexi-Drugs, NeoFax and NNF, whereas IM injection is mentioned only by Pediatric and Neonatal Lexi-Drugs and NeoFax, and dosing recommendations for the rectal route are only available on DPF. All formularies suggest IV dosing via a bolus LD followed by continuous infusion MD with similar dosage recommendations, with all but ANMF explicitly stating that doses should be individualized/given as needed.

Dosing recommendations vary according to route of administration, but are overall fairly comparable across formularies. Specific, age-based recommendations for preterm infants are available on ANMF, DPF and Pediatric and Neonatal Lexi-Drugs.

Gentamicin is an antibiotic in common use in neonatal units, mainly for its efficacy in empiric treatment of suspected neonatal sepsis. It is usually given through the IV route, although IM injections are also possible (albeit less preferred). All formularies except DPF state that IM injections are possible (with reservations), where it should be noted that BNF for Children and NeoFax do not provide this information in the neonatal dosing section, but in other sections of the monograph.

Dosing recommendations for gentamicin are largely similar across formularies, as are the dosing intervals, which are affected by the age of the infant, since it has rather good correlation with the degree of renal function, because gentamicin is eliminated mostly renally. The age categories for determining optimal dosing interval slightly differ between formularies, with NeoFax and Pediatric and Neonatal Lexi-Drugs suggesting 6 age categories and on the other end BNF for Children suggests only two age groups. All formularies beside BNF for Children address in the neonatal dosing section the need for therapeutic drug monitoring during treatment with gentamicin. BNF for Children does address this issue, not in the neonatal dosing section but in the ‘monitoring parameters’ section.