1. Introduction

Drug misuse is the use of medicine in a way that is inconsistent with medical guidelines, and often involves prescription medication. While drug abuse is known as using the prescription and over-the-counter (OTC) medicine for a nonmedical reason to achieve euphoria [

1]. Literature showed that some classes of medications including stimulants, laxatives, sedatives, dissociative substances, opiate-containing medicines, and smoking-cessation products can be potentially abused [

2]. Owing to their accessibility and perceived safety, OTC medications have higher tendency to be abused [

2]. Loperamide, an OTC anti-diarrheal agent, acts as an agonist to mu (µ) receptors in the periphery and is expected to have low abuse potential when taken at recommended doses [

3]. However, at high doses it can cross blood brain barriers and thus cause opioid-like euphoria leading to abuse and addiction [

3,

4]. Indeed, cases of Loperamide abuse and misuse were identified in several countries, mainly due its low cost and ease of access [

4]. Reports to the National Poison Data System in the United States between 2010-2015, showed that the intentional misuse, abuse, and Loperamide-related suicide had increased by 91%, and among 26 cases which were identified between 2011-2019 by the ToxIC registry, 12 (67%) were misuse/abuse cases [

5,

6,

7] Consistently, the European Medicines Agency's (EMA) pharmacovigilance report evaluated Loperamide adverse drug reactions (ADRs) the 2005 to 2017 in the European Economic Areas (EAA) and non-EAA. Among 1983 ADRs, the 'drug use disorder' (n=742; 37.4%), 'intentional overdose' (n=502, 25.3%), and 'intentional product misuse' (n=269; 14.9%) were the most common ones. [

2,

8].Therefore, more laboratories are including Loperamide in their standard screening and clinicians should be aware of the potential abuse as it becomes increasingly pivotal to identify these potential cases of inappropriate use since Loperamide overdose can result in addiction as well as serious detrimental adverse effects such as respiratory and Central Nervous System Depression, QTc prolongation and even fatalities [

8,

9,

10].

Pharmacists, accessible healthcare providers, are ideally positioned to identify abuse potential among patients. In addition, they can have a crucial role in preventing further overdoses by characterizing abuse patterns and diversion, educating about risk of Loperamide overdose, and referring risky patients to substance-use treatment [

11]. In the US, an assessment of pharmacists' awareness about Loperamide abuse and their ability to restrict abuse potential is vital since around 72% of pharmacists reported their awareness about Loperamide abuse and had good attitudes about their ability to decrease the quantity obtained or refused to dispense Loperamide in case of abuse potential [

12]. However, only 3.2% of pharmacists had taken measures to minimize abuse potential and placed Loperamide behind the counter [

12]. The ability of pharmacists to identify abuse cases and how to deal with them can be affected by many factors such as years of experience [

13,

14,

15] which has not been widely investigated. According to a Jordanian study in 2016, and more recently in 2022, the most abused drugs in community pharmacies were decongestants, cough/cold preparations, benzodiazepines, and antibiotics [

16]. However, Loperamide abuse patterns in our region have not been investigated thoroughly. Therefore, this study aims to assess the ability of community pharmacists to recognize cases of Loperamide abuse at the point of sale, their perspective, and experience towards potential abuse cases.

2. Materials and Methods

This was a cross-sectional study conducted on Jordanian pharmacists from all governorates (North, center (including capital of Jordan), and South) from September 2021 until July 2022. The data was collected using an electronic self-administered questionnaire using a snowball convenience. Google forms platform was used to run the survey, which was subsequently shared on numerous social media platforms (i.e., WhatsApp, LinkedIn, and Facebook). There was no risk to the respondents and their participation was anonymous and voluntary. Jordanian pharmacists and pharmacy assistants who worked in community pharmacies were eligible for study enrollment. The participant's confidentiality was maintained throughout the data collection process. Ethical approval for the study was obtained from the Faculty of Pharmacy, Applied Science Private University (Approval number: 2021-PHA-33).

2.1. Study Tool

The study questionnaire was mainly adapted from a similar published-validated tool conducted in Jordan [

16,

17]. The questionnaire was administered in Arabic, the native language of Jordan and designed in an Arabic language. The expected filling time of the questionnaire was five minutes. About 5–20 participants per predictor are recommended as being ideal based on Tabachnick and Fidell's recommendations for sample size calculation in analysis [

18]. Considering that the number of independent variables was 12 and the utilization of 10 individuals per predictor in this study, a minimum sample size of 120 or more was thought to be appropriate for this study's goals.

The questionnaire was composed of three main sections: the first section covered sociodemographic characteristics of the participants (age, gender, educational level, monthly incentive status, years of experience, and working shift in the pharmacy). The second section was concerned about the pharmacy information (location, type of the pharmacy, and general socioeconomic status of patients visiting the pharmacies). The third section focused on pharmacists' experience with Loperamide abuse, such as cases of abuse, extent of abuse, as well as characteristics of patients who seek Loperamide such as gender, socioeconomic status. Moreover, the questionnaire assessed pharmacists' attitudes toward suspected abusers, as well as perceived motivation behind their abuse. At the end of the questionnaire there was an open space for further comments that may support the aim of the study.

2.2. Statistical Analysis

Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) 25.0 was used to conduct the statistical analysis. The mean and standard deviations (SD) for all continuous variables were provided, and the frequencies (n) and percentages (%) of all categorical variables were used. To identify the factors linked with the pharmacist-reported cases of Loperamide misuse, binary logistic regression was used. In the bivariate analysis, variables with a p-value of less than 0.25 were included [

19]. Results were shown as odds ratios (OR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI). The two-tailed p-value of 0.05 was used to determine if the relation was statistically significant.

3. Results

3.1. Sociodemographic Characteristics

A total of 250 pharmacists completed the survey, and around half of them (n=135, 54%) were female. Sixty percent (n=150) of the respondents were less than forty years old and the majority had a bachelor's degree 82.8% (207). Regarding the pharmacist's experience in community pharmacy, most of the participants (64%) had monthly incentive system based on the quantity of medicines sold per month, and nearly half of them (47.2 %) had more than 10 years' experience. Most participants (74.4%) were working in pharmacies located on middle region of Jordan and 66% worked in pharmacies located on a main road. Based on the pharmacist perception, pharmacy customers were classified according to their socioeconomic status as low to middle, middle-income (n= 110 ,44 %), (n= 79 ,31.6%) respectively. Most of the participants held a post of "principal pharmacist" in the community pharmacy (n= 221 ,88.4%), who is responsible for pharmacy management and decision making.

Table 1.

3.2. Pharmacist Experience with Loperamide Use and Abuse

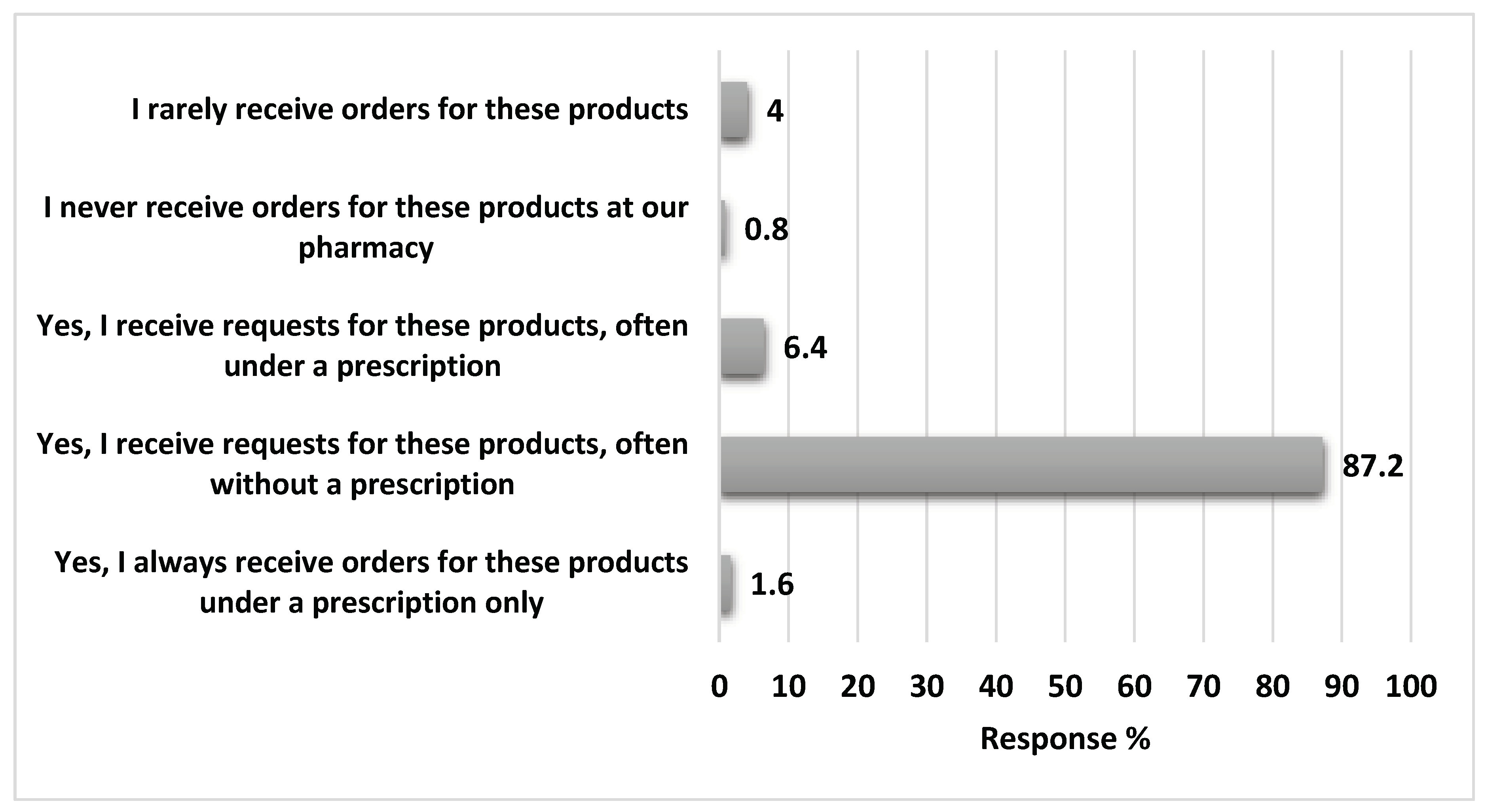

The majority of the pharmacists received requests for Loperamide use without a physician prescription (87.2%) as illustrated in

Figure 1. Almost one-third (n=83, 33.2%) of the participants reported their exposure to suspected cases of Loperamide abuse during last six months. Imodium® caps, Loperium® tab, and Imodium® instant ODT were the most products increasing in its improper use in Jordan (83.1%, 83.1 and 72.3 %, respectively). Pharmacists declared that most of the suspected Loperamide abusers were male (60.2%), of middle-low socioeconomic status (69.9%), and were between 20-30 years of age (57.8%),

Table 2.

The majority of the respondents (85.5%) who reported the suspected Loperamide abuse cases, confirmed that the abuse suspected cases are increasing with time. The largest quantity (packs) of Loperamide requested from the pharmacist by a single patient was around 33 (mean 33.2±14.9). The suspected abusers could be both strangers and regular patients requesting the product without a prescription (81.9%). Moreover, the suspected Loperamide abusers were identified by pharmacists through some remarks including: their mood disturbances management, in ability to control impulses, and thought disturbance (89.2%), exaggeration of medical problem and/or mimicking symptoms to get medication (89.2%), and patients with unusual appearance (74.7%),

Table 2.

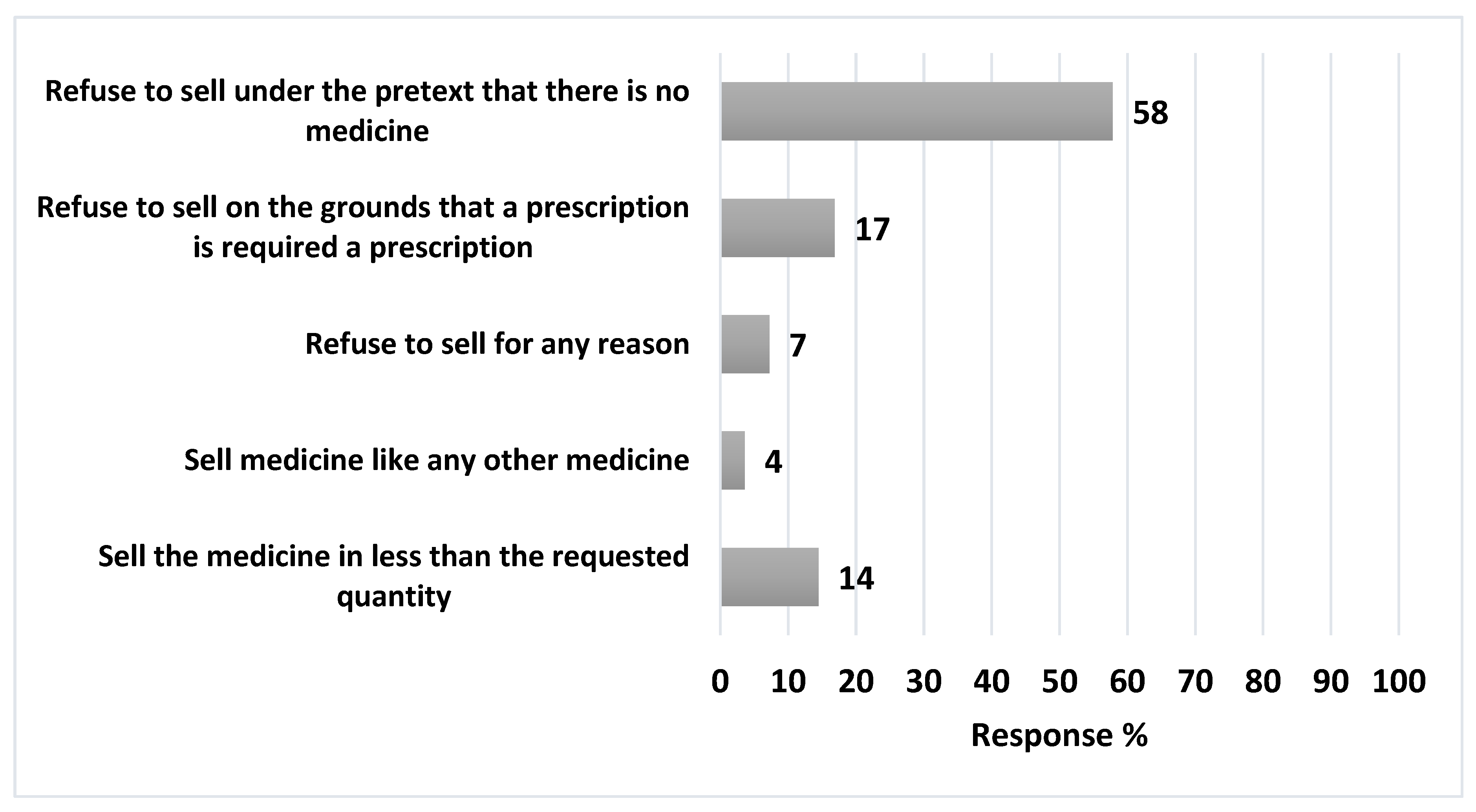

Regarding pharmacist's response towards suspected abusers, out of the 83 pharmacists, 58% (n=48) refused to sell Loperamide under the pretext of lack of medication, while 14% (n=12) dispensed quantity lower than requested. Meanwhile, 17% (n=14) refused to sell on the ground that drug should be prescribed and only 4% sold the medication like any other medicine,

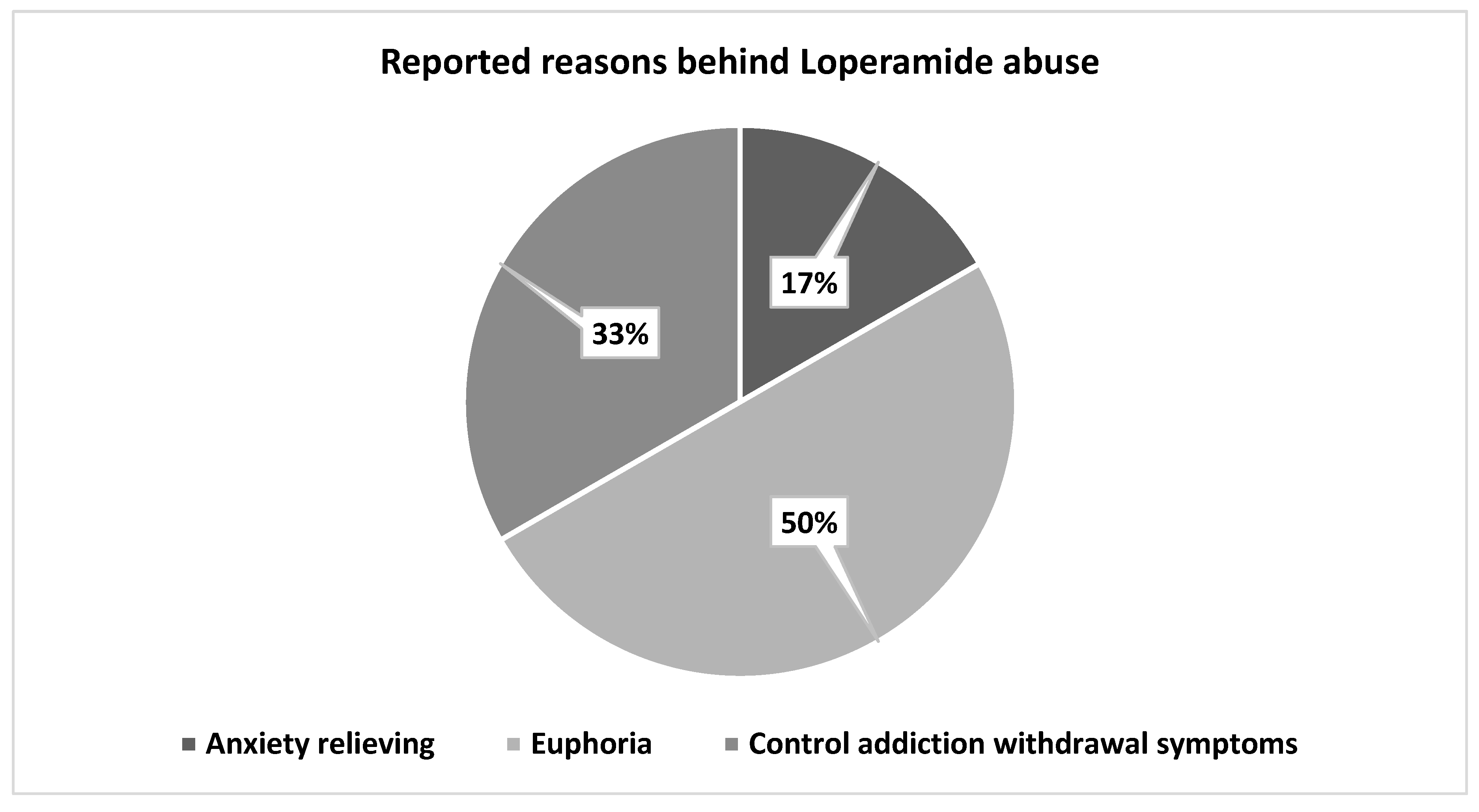

Figure 2. The pharmacist also reported that the possible reasons behind Loperamide abuse included 50% seeking euphoria, 33% controlling addiction (weaning off other opioids), and 17% relieving anxiety,

Figure 3.

The multivariate logistic regression analysis,

Table 3, demonstrated a significant correlation between the participants' reported Loperamide abuse during the last 6 months and the male gender (OR=1.2, 95%CI 0.12-1.59), pharmacy location in the Centre of Jordan (OR=21.2, 95%CI 2.45-183.59) and working in the late-night shift from 12 to 8 AM (Shift C, OR=1.29, 95% CI 0.12-2.08).

4. Discussion

Loperamide, a common anti-motility OTC medication, has been targeted as a drug of abuse due to its euphoric and sedating effects at supratherapeutic doses [

3]. OTC drug abuse in Jordan has been documented in the last few years with the cough and cold preparations as well as the nasal decongestants being the most reported medications [

16,

20]. Although there is no definitive data on the extent of loperamide abuse in Jordan, a recent study conducted by Webb

et al. indicates that non-medical use of Loperamide is common in United Kingdom (UK) and the United States of America (USA) [

21]. Moreover, numerous case reports in addition to the state poison control center reports that have been published in recent years, reports that loperamide abuse is a cause of concern [

6]. Between 2010 and 2015, epidemiological studies carried out in the USA revealed a notable rise in the loperamide abuse, and a significant increase in intentional exposure to Loperamide, with a third of cases occurring in teenagers and young adults [

4,

6]. This is a global health concern, and the current study is the first to examine the perspective of Jordanian pharmacists on loperamide abuse in the community.

The study found that 87.2% of pharmacists are asked for Loperamide without a prescription, which is a normal expectation as it is classified as an OTC medication. However, we believe that abusers may be shifting to OTC medications for easier access, lower suspicion and lacking their drugs (especially during COVID-19 pandemic). About one-third of the community pharmacists surveyed (33.2%) in our study reported receiving suspicious requests for Loperamide in the past six months, and 85.5% of pharmacists believed that the loperamide abuse is rapidly growing leaving no-doubt about the issue. The study also found that 60.2% of suspected loperamide abusers were male, which is consistent with the US national poison data system where Loperamide is more likely to be abused by male subjects [

6]. In parallel, it has been documented by the United Nation office of drugs and crime (UNDC), that opioids worldwide are abused by males, to which Loperamide belongs[

22]. It is not clear yet why men have more tendency to develop drug abuse, but previous theories attributed that to ease of access by male peers and the enhanced sense of masculinity [

23]. However, 34.9% of pharmacists reported receiving suspicious requests from both genders, suggesting that the gender gap may be narrowing. Internet fora discussing Loperamide have become more prevalent since 2010, with a focus on the drug's euphoric effects and ability to self-treat opioid withdrawal [

24,

25]. The majority of the pharmacists (88%) in our study believed that the feeling of euphoria and addiction control were the main reasons for loperamide abuse [

25].

Pharmacists play a crucial role in controlling OTC medication abuse by monitoring their use among specific populations. The past research has identified various measures that pharmacists usually apply to reduce the likelihood of OTC medication abuse [

26]. Among the most commonly used measures by pharmacists were refraining from selling, concealing the problematic products, and questioning the potential abusers about their purchase [

27,

28]. In this study it was demonstrated that 58% refrain from selling Loperamide under the pretext that the medication is not available which is consistent with the results from another study [

16,

28,

29,

30]. Nonetheless, Jordanian community pharmacists encounter numerous obstacles when addressing OTC medication abuse, one most of the most common being "pharmacy hopping". Therefore, additional urgent measures are indispensable from drug authorities in Jordan. To address the abuse of Loperamide, the US food and drug administration (FDA) has implemented multiple measures, for instance, in June 2016, the FDA issued a Drug Safety Communication warning about the serious and fatal cardiac events associated with loperamide abuse, such as QT-interval prolongation, torsade de pointes (TdP), and cardiac arrest [

6,

31]. Also, patients were cautioned against surpassing the prescribed or OTC doses since this could cause severe heart rhythm problems or even death. Additionally, a black box warning was added to Imodium's package insert, which mentioned the instances of heart issues that had been reported due to the improper use of Imodium in supratherapeutic doses [

6,

31]. Furthermore, to increase the safe use of loperamide products, the FDA approved new packaging for brand-name OTC loperamide in September 2019, which does not limit OTC access for consumers who intend to use Loperamide appropriately [

32]. The new packaging limits each package to a maximum of 48 mg of Loperamide and requires unit-dose blister packaging [

32]. Therefore, similar measures are warranted in Jordan to limit the cases of loperamide abuse. Also, to address this problem, drug regulatory agencies such as the Jordan Ministry of Health (MoH) and Jordan Drug and Food Administration (JFDA) should strengthen their approach and strictly implement drug regulations which are expected to reduce this problem. Although the 2013 Jordanian Drug and Pharmacy Practice Law requires pharmacists to keep records of prescription of Scheduled I-VII drugs, it doesn't mandate such records for other drugs, including Loperamide, that are known to be abused [

16]. Therefore, the law should be updated to include these medications. Another potential approach to address this issue is reclassifying medications to be misused or abused, as seen in the case of alprazolam which was moved to Schedule III medication by the JFDA in 2014. This change led to reduction in access to alprazolam which had previously been a frequently abused drug in Jordan [

16]. In parallel, several studies have presented substantial proof that pharmacists can play a significant role in addressing the opioid crisis through the provision of overdose-prevention training, medication reviews, and counselling [

33].

There are a number of limitations to this study. First, response credibility may be jeopardized by knowledge bias relating to the availability of resources on demand. Second, there may be selection bias with the snowball collection method and lack of random selection. Third, possible unmeasured factors or responses to variables that are directly or indirectly related to Loperamide abuse. Also, using an online survey rather than a face-to-face encounter puts the study data's trustworthiness and authenticity at risk.

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, instances of loperamide abuse continue to increase, it is necessary to tackle this problem. Each member of the healthcare team has a part to play, such as ensuring proper pain management, imparting education, or introducing changes at the state level. It is crucial for the healthcare team to act swiftly and efficiently in order to prevent harm to patients and address this growing concern.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Muna Barakat, Amal Akour, Mayyada Wazaify; methodology Muna Barakat, Amal Akour, Mayyada Wazaify.; software, Muna Barakat. Diana Malaeb; validation, Muna Barakat, Amal Akour, Mayyada Wazaify; formal analysis, Muna Barakat. Sarah Cherri; investigation, Muna Barakat, Amal Akour, Mayyada Wazaify; resources, Muna Barakat.; data curation, , Muna Barakat.; writing—original draft preparation, Muna Barakat, Amal Akour, Sarah Cherri. Walaa Al Safadi, Ala’a AL Safadi; writing—review and editing, Muna Barakat, Diana Malaeb. Amal Akour, Mayyada Wazaify; visualization, Muna Barakat, Diana Malaeb. Amal Akour.; supervision, Mayyada Wazaify.; project administration, Muna Barakat.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Review Board (or Ethics Committee) of Faculty of Pharmacy, Applied Science Private University, Amman, Jordan (Approval number: 2021-PHA-33).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

The authors of this work would like to acknowledge the assistance of Miss Leena Al-Ani in Data collection and continued support received form Applied Science Private university, Jordan.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Tommasello, A.C. Substance abuse and pharmacy practice: what the community pharmacist needs to know about drug abuse and dependence. Harm Reduct J 2004, 1, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Algarni, M.; Hadi, M.A.; Yahyouche, A.; Mahmood, S.; Jalal, Z. A mixed-methods systematic review of the prevalence, reasons, associated harms and risk-reduction interventions of over-the-counter (OTC) medicines misuse, abuse and dependence in adults. J of Pharm Policy and Pract 2021, 14, 76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Powell, J.W.; Presnell, S.E. Loperamide as a Potential Drug of Abuse and Misuse: Fatal Overdoses at the Medical University of South Carolina. J Forensic Sci 2019, 64, 1726–1730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borron, S.W.; Watts, S.H.; Tull, J.; Baeza, S.; Diebold, S.; Barrow, A. Intentional Misuse and Abuse of Loperamide: A New Look at a Drug with “Low Abuse Potential”. The Journal of Emergency Medicine 2017, 53, 73–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lasoff, D.R.; Koh, C.H.; Corbett, B.; Minns, A.B.; Cantrell, F.L. Loperamide Trends in Abuse and Misuse Over 13 Years: 2002-2015. Pharmacotherapy 2017, 37, 249–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vakkalanka, J.P.; Charlton, N.P.; Holstege, C.P. Epidemiologic Trends in Loperamide Abuse and Misuse. Annals of Emergency Medicine 2017, 69, 73–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, V.R.; Vera, A.; Alexander, A.; Ruck, B.; Nelson, L.S.; Wax, P.; Campleman, S.; Brent, J.; Calello, D.P. Loperamide misuse to avoid opioid withdrawal and to achieve a euphoric effect: high doses and high risk. Clinical Toxicology 2019, 57, 175–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schifano, F.; Chiappini, S. Is there such a thing as a'lope'dope? Analysis of loperamide-related European Medicines Agency (EMA) pharmacovigilance database reports. PLoS One 2018, 13, e0204443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antoniou, T.; Juurlink, D.N. Loperamide abuse. Canadian Medical Association Journal 2017, 189, E803–E803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whittaker, G.; Newman, J. Loperamide: an emerging drug of abuse and cause of prolonged QTc. Clin Med 2021, 21, 150–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, S.; White, B. Pharmacist and Prescriber Responsibilities for Avoiding Prescription Drug Misuse. AMA Journal of Ethics 2021, 23, 471–479. [Google Scholar]

- Feldman, R.; Everton, E. National assessment of pharmacist awareness of loperamide abuse and ability to restrict sale if abuse is suspected. Journal of the American Pharmacists Association 2020, 60, 868–873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mobrad, A.M.; Alghadeer, S.; Syed, W.; Al-Arifi, M.N.; Azher, A.; Almetawazi, M.S.; Babelghaith, S.D. Knowledge, Attitudes, and Beliefs Regarding Drug Abuse and Misuse among Community Pharmacists in Saudi Arabia. IJERPH 2020, 17, 1334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barakat, M.; Al-Qudah, R.a.; Akour, A.; Al-Qudah, N.; Dallal Bashi, Y.H. Unforeseen uses of oral contraceptive pills: Exploratory study in Jordanian community pharmacies. PLOS ONE 2020, 15, e0244373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barakat, M.M.; Al-Qudah, R.a.A.; Akour, A.; Abu-Asal, M.; Thiab, S.; Dallal Bashi, Y.H. The Use/Abuse of Oral Contraceptive Pills Among Males: A Mixed-Method Explanatory Sequential Study Over Jordanian Community Pharmacists; Addiction Medicine: 2021/03/12/ 2021.

- Albsoul-Younes, A.; Wazaify, M.; Yousef, A.-M.; Tahaineh, L. Abuse and Misuse of Prescription and Nonprescription Drugs Sold in Community Pharmacies in Jordan. Substance Use & Misuse 2010, 45, 1319–1329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Husseini, A.; Abu-Farha, R.; Wazaify, M.; Van Hout, M.C. Pregabalin dispensing patterns in Amman-Jordan: An observational study from community pharmacies. Saudi pharmaceutical journal 2018, 26, 306–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tabachnick, B.G.; Fidell, L.S.; Ullman, J.B. Using multivariate statistics; Pearson Boston, MA: 2007; Volume 5.

- Chowdhury, M.Z.I.; Turin, T.C. Variable selection strategies and its importance in clinical prediction modelling. Family medicine community health 2020, 8.

- Wazaify, M.; Abood, E.; Tahaineh, L.; Albsoul-Younes, A. Jordanian community pharmacists’ experience regarding prescription and nonprescription drug abuse and misuse in Jordan–An update. Journal of Substance Use 2017, 22, 463–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Webb, N.E.; Wood, D.M.; Black, J.C.; Amioka, E.; Dart, R.C.; Dargan, P.I. Non-medical use of loperamide in the UK and the USA. QJM: An International Journal of Medicine 2020, 113, 25–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- (UNDC), U.N.o.o.d.a.c. World drug report, EXECUTIVE SUMMARY POLICY IMPLICATIONS; 2022.

- Chung, C.-H.; Lin, I.-J.; Huang, Y.-C.; Sun, C.-A.; Chien, W.-C.; Tzeng, N.-S. The association between abused adults and substance abuse in Taiwan, 2000–2015. BMC psychiatry 2023, 23, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daniulaityte, R.; Carlson, R.; Falck, R.; Cameron, D.; Perera, S.; Chen, L.; Sheth, A. “I just wanted to tell you that loperamide WILL WORK”: a web-based study of extra-medical use of loperamide. Drug alcohol dependence 2013, 130, 241–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, V.R.; Vera, A.; Alexander, A.; Ruck, B.; Nelson, L.S.; Wax, P.; Campleman, S.; Brent, J.; Calello, D. Loperamide misuse to avoid opioid withdrawal and to achieve a euphoric effect: high doses and high risk. Clinical Toxicology 2019, 57, 175–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Major, C.; Vincze, Z. Consumer habits and interests regarding non-prescription medications in Hungary. Family Practice 2010, 27, 333–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sansgiry, S.S.; Bhansali, A.H.; Bapat, S.S.; Xu, Q. Abuse of over-the-counter medicines: a pharmacist’s perspective. Integrated Pharmacy Research Practice 2016, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes, C.M. Monitoring self-medication. 2003, 2, 1–5.

- Paxton, R.; Chapple, P. Misuse of over-the-counter medicines: a survey in one English county. Pharmaceutical Journal 1996, 256, 313–315. [Google Scholar]

- Bates, D.; Deering, M.J.; Leavitt, M. E-pharmacy: improving patient care and managing risk. Journal of the American Pharmaceutical Association 2002, 42, S20–S21. [Google Scholar]

- Shastay, A. Dangerous Abuse of a 40-Year-Old Over-the-Counter Medication, Loperamide. Home Healthcare Now 2020, 38, 167–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sapra, A.; Bhandari, P.; Gupta, S.; Kraleti, S.; Bahuva, R. A Rising Concern of Loperamide Abuse: A Case Report on Resulting Cardiac Complications. Cureus 2019, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chisholm-Burns, M.A.; Spivey, C.A.; Sherwin, E.; Wheeler, J.; Hohmeier, K. The opioid crisis: origins, trends, policies, and the roles of pharmacists. American journal of health-system pharmacy 2019, 76, 424–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).