Submitted:

18 April 2023

Posted:

19 April 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

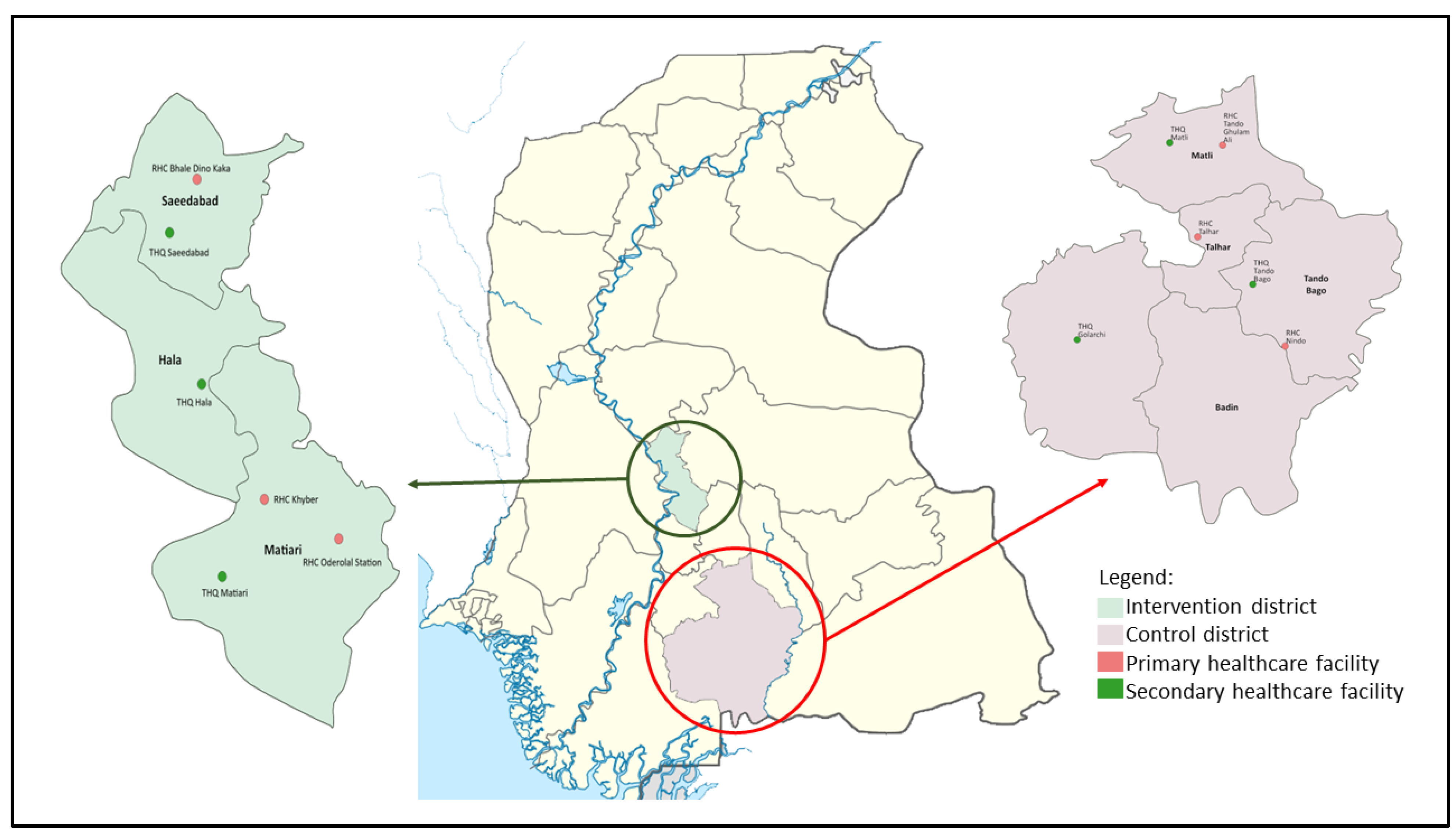

2.2. Study Setting

2.3. Study Sites

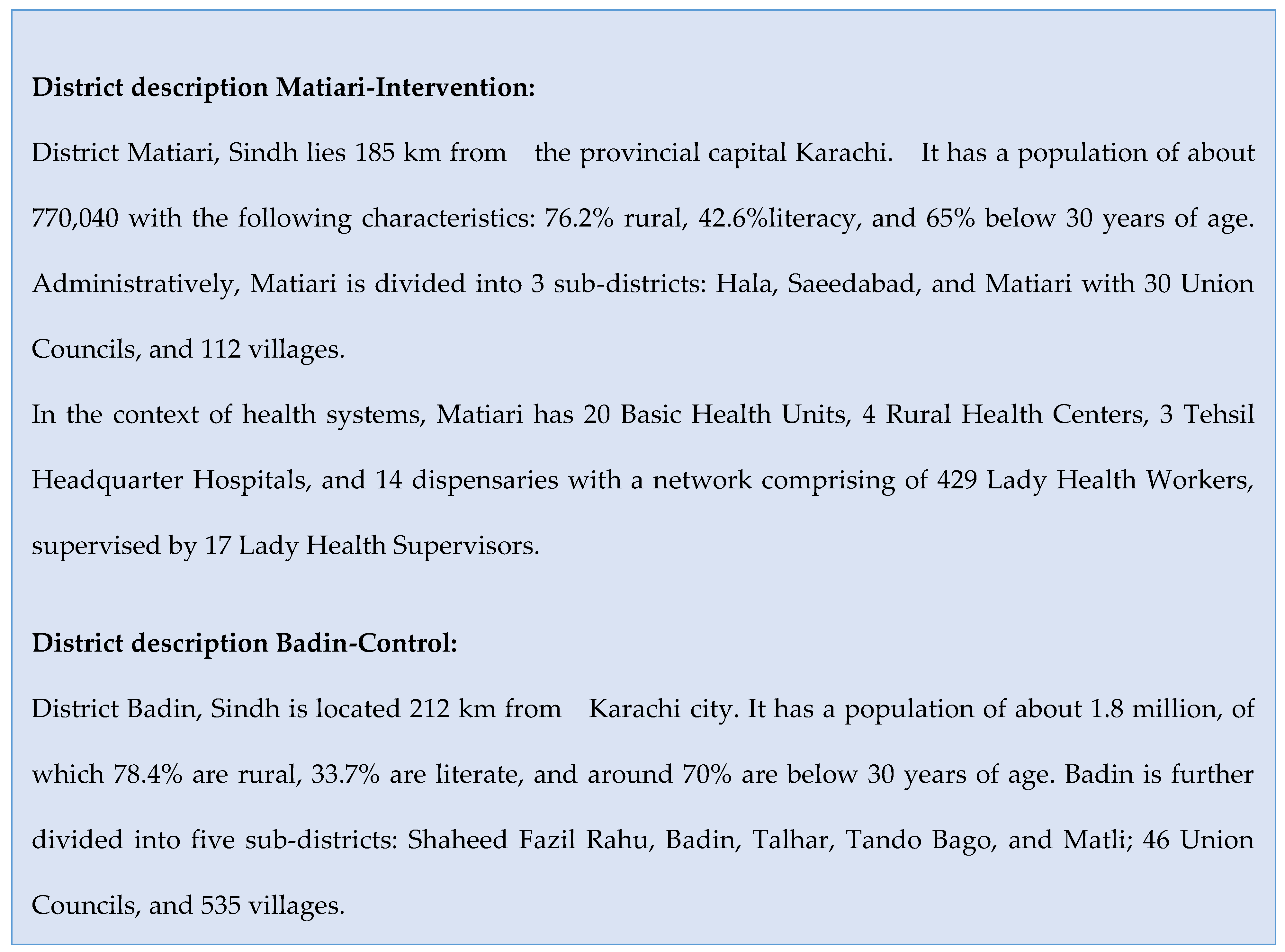

2.4. Intervention Design

2.5. Study Interventions

2.6 Ethical Consideration

3. Results

3.1. Socio demographic characteristics of the study respondents in control and intervention districts

3.2. Effects of Intervention on Primary Outcomes

3.3. Effects of Intervention on Secondary Outcomes

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- National Institute of Population Studies (NIPS) [Pakistan] and ICF International, “ Pakistan Demographic and Health Survey 2012-13.,” Islamabad, Pakistan, and Calverton, Maryland, USA, 2013.

- Simon. Wright, “Ending newborn deaths: Ensuring every baby survives.,” 2014.

- Z. A. Bhutta et al., “Reproductive, maternal, newborn, and child health in Pakistan: Challenges and opportunities.,” Lancet, vol. 381, no. 9884, pp. 2207–18, Jun. 2013. [CrossRef]

- NIPS and ICF, Pakistan Demographic and Health Survey 2017-18. Islamabad, Pakistan, and Rockville, Maryland, USA, 2019.

- B. Zaidi and S. Hussain, “Reasons for low modern contraceptive use—Insights from Pakistan and neighboring countries,” 2015. [Online]. Available: https://knowledgecommons.popcouncil.org/departments_sbsr-rh.

- J. F. May and S. Rotenberg, “A Call for Better Integrated Policies to Accelerate the Fertility Decline in Sub-Saharan Africa,” Stud Fam Plann, vol. 51, no. 2, pp. 193–204, Jun. 2020. [CrossRef]

- D. Tsegaye, M. Tehone, S. Yesuf, and A. Berhane, “Post-Partum Family Planning Integration With Maternal Health Services & Its Associated Factors: An Opportunity to Increase Postpartum Modern Contraceptive Use in Eastern Amhara Region, Ethiopia, 2020,” 2021. [CrossRef]

- K. Ringheim, “Integrating Family Planning and Maternal and Child Health Services: History Reveals a Winning Combination,” Washington DC, 2011.

- Population Welfare Department Government of Sindh, “Sindh Population Policy 2016,” Karachi, 2016.

- C. M. Cooper et al., “Integrated Family Planning and Immunization Service Delivery at Health Facility and Community Sites in Dowa and Ntchisi Districts of Malawi: A Mixed Methods Process Evaluation,” Int J Environ Res Public Health, vol. 17, no. 12, p. 4530, Jun. 2020. [CrossRef]

- S. K. Azmat et al., “Engaging with community-based public and private mid-level providers for promoting the use of modern contraceptive methods in rural Pakistan: Results from two innovative birth spacing interventions,” Reprod Health, vol. 13, no. 1, 2016. [CrossRef]

- In High-Impact Practices in Family Planning (HIP), “Family Planning and Immunization Integration: Reaching Postpartum Women with Family Planning Services.,” Washington, DC, USA, 2013. Accessed: Mar. 26, 2023. [Online]. Available: http://www.fphighimpactpractices.org/briefs/family-planning-and-immunization-integration.

- Z. Memon et al., “Effect of integrating Family Planning with Maternal, Newborn and Child Health services on uptake of voluntary modern contraceptive methods in rural Pakistan: Protocol for a Quasi-experimental study (Preprint),” JMIR Res Protoc, Nov. 2021. [CrossRef]

- M. Caliendo and S. Kopeinig, “SOME PRACTICAL GUIDANCE FOR THE IMPLEMENTATION OF PROPENSITY SCORE MATCHING,” J Econ Surv, vol. 22, no. 1, pp. 31–72, Feb. 2008. [CrossRef]

- Bureau of Statistics Planning & Development Board Government of the Sindh, “Monitoring the situation of children and women Multiple Indicator Cluster Survey 2018-19,” Feb. 2021.

- Z. A. Memon, A. Mian, S. Reale, R. Spencer, Z. Bhutta, and H. Soltani, “Community and Health Care Provider Perspectives on Barriers to and Enablers of Family Planning Use in Rural Sindh, Pakistan: Qualitative Exploratory Study,” JMIR Form Res, vol. 7, p. e43494, Mar. 2023. [CrossRef]

- M. Ali, S. K. Azmat, H. bin Hamza, Md. M. Rahman, and W. Hameed, “Are family planning vouchers effective in increasing use, improving equity and reaching the underserved? An evaluation of a voucher program in Pakistan,” BMC Health Serv Res, vol. 19, no. 1, p. 200, Dec. 2019. [CrossRef]

- E. Pradhan et al., “Integrating postpartum contraceptive counseling and IUD insertion services into maternity care in Nepal: Results from stepped-wedge randomized controlled trial,” Reprod Health, vol. 16, no. 1, p. 69, Dec. 2019. [CrossRef]

- C. E. Warren, T. L. McClair, K. R. Kirk, C. Ndwiga, and E. A. Yam, “Design, adaptation, and diffusion of an innovative tool to support contraceptive decision-making: Balanced Counseling Strategy Plus,” Gates Open Res, vol. 6, p. 2, May 2022. [CrossRef]

- S. Rahman et al., “Effect of a package of integrated demand- and supply-side interventions on facility delivery rates in rural Bangladesh: Implications for large-scale programs,” PLoS ONE, vol. 12, no. 10, p. e0186182, Oct. 2017. [CrossRef]

- C. M. Cooper et al., “Successful Proof of Concept of Family Planning and Immunization Integration in Liberia,” Glob Health Sci Pract, vol. 3, no. 1, pp. 71–84, Mar. 2015. [CrossRef]

- T. Jongh, I. Gurol-Urganci, E. Allen, N. Jiayue Zhu, and R. Atun, “Barriers and enablers to integrating maternal and child health services to antenatal care in low and middle income countries,” BJOG, vol. 123, no. 4, pp. 549–557, Mar. 2016. [CrossRef]

- W. Hameed et al., “Women’s Empowerment and Contraceptive Use: The Role of Independent versus Couples’ Decision-Making, from a Lower Middle Income Country Perspective,” PLoS ONE, vol. 9, no. 8, p. e104633, Aug. 2014. [CrossRef]

- Z. Kurji, Z. S. Premani, and Y. Mithani, “Analysis Of The Health Care System Of Pakistan: Lessons Learnt And Way Forward.,” J Ayub Med Coll Abbottabad, vol. 28, no. 3, pp. 601–604, 2016.

- R. Nelson et al., “Operationalizing Integrated Immunization and Family Planning Services in Rural Liberia: Lessons Learned From Evaluating Service Quality and Utilization,” Glob Health Sci Pract, vol. 7, no. 3, pp. 418–34, Sep. 2019, [Online]. Available: www.ghspjournal.org.

- M. Komasawa, M. Yuasa, Y. Shirayama, M. Sato, Y. Komasawa, and M. Alouri, “Impact of the village health center project on contraceptive behaviors in rural Jordan: A quasi-experimental difference-in-differences analysis,” BMC Public Health, vol. 19, no. 1, p. 1415, Dec. 2019. [CrossRef]

- M. Douthwaite and P. Ward, “Increasing contraceptive use in rural Pakistan: An evaluation of the Lady Health Worker Programme,” Health Policy Plan, vol. 20, no. 2, pp. 117–123, Mar. 2005. [CrossRef]

- 28. Afsar Habib Ahmed, Younus Muhammad, and Gul Asma, “ Outcome of patient referral made by the lady health workers in Karachi, Pakistan.,” J Pak Med Assoc, vol. 55, no. 5, pp. 209–211, May 2005.

- S. Ariff et al., “Evaluation of health workforce competence in maternal and neonatal issues in public health sector of Pakistan: An Assessment of their training needs,” BMC Health Serv Res, vol. 10, no. 1, p. 319, Dec. 2010. [CrossRef]

- F. Rabbani, L. Shipton, W. Aftab, K. Sangrasi, S. Perveen, and A. Zahidie, “Inspiring health worker motivation with supportive supervision: A survey of lady health supervisor motivating factors in rural Pakistan,” BMC Health Serv Res, vol. 16, no. 1, p. 397, Dec. 2016. [CrossRef]

- Zhu N, Allen E, Kearns A, and Caglia J, “Lady Health Workers in Pakistan: Improving Access to Health Care for Rural Women and Families.,” Boston, MA:, 2014.

- S. Zaidi, M. Huda, A. Ali, X. Gul, R. Jabeen, and M. M. Shah, “Pakistan’s Community-based Lady Health Workers (LHWs): Change Agents for Child Health? ,” Glob J Health Sci, vol. 12, no. 11, pp. 177–187, Oct. 2020, Accessed: Mar. 27, 2023. [Online]. Available: https://ideas.repec.org/a/ibn/gjhsjl/v12y2020i11p177-187.html.

- A. Khan, T. Ahmad, A. Najam, and A. Khan, “Community-Driven Family Planning in Urban Slums: Results from Rawalpindi, Pakistan,” Biomed Res Int, vol. 2023, pp. 1–10, Feb. 2023. [CrossRef]

- H. Tappis, A. Kazi, W. Hameed, Z. Dahar, A. Ali, and S. Agha, “The Role of Quality Health Services and Discussion about Birth Spacing in Postpartum Contraceptive Use in Sindh, Pakistan: A Multilevel Analysis,” PLoS ONE, vol. 10, no. 10, Oct. 2015. [CrossRef]

- L. Mwaikambo, I. S. Speizer, A. Schurmann, G. Morgan, and F. Fikree, “What works in family planning interventions: A systematic review of the evidence,” Stud Fam Plann, vol. 42, no. 2, pp. 67–82, Jun. 2011.

- H. Nsubuga, J. N. Sekandi, H. Sempeera, and F. E. Makumbi, “Contraceptive use, knowledge, attitude, perceptions and sexual behavior among female University students in Uganda: A cross-sectional survey,” BMC Womens Health, vol. 16, no. 1, p. 6, Dec. 2016. [CrossRef]

| Indicator | Intervention health facilities | Control health facilities |

|---|---|---|

| Type of Health Facility | ||

|

3 | 3 |

|

3 | 3 |

| Total number of health facilities | 6 | 6 |

| Number of LHWs attached to the health facilities | 133 | 142 |

| Delivery clients (Mean and SD) | 277 ± 53 | 294. ± 87 |

| ANC-1 (Mean and SD) | 908 ± 175 | 1082. ± 242 |

| ANC-Revisit (Mean and SD) | 990 ± 183 | 580. ± 188 |

| New FP Clients (Mean and SD) | 354 ± 111 | 212. ± 59 |

| Follow-up FP Clients (Mean and SD) | 69 ± 62 | 41. ± 19 |

| Immunization:3rd Pentavalent (Mean and SD) | 567 ± 200 | 679 ± 329 |

| Variable Baseline |

Intervention N=860 |

Control N=824 |

p value(t-test/Chi-square) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Matiari | Badin | ||||||

| mean | SD | mean | SD | ||||

| Household Size | 7.5 | [±2.2] | 7.0 | [±3.3] | 0.570 | ||

| Respondent’s age | 33.4 | [± 7.8] | 31.3 | [± 6.5] | 0.342 | ||

| Husband’s Age | 38.1 | [± 9.6] | 34.8 | [±7.5] | 0.021 | ||

| Number of Children (Parity) | 4.0 | [±2.0] | 4.0 | [± 2.0] | 0.249 | ||

| Number of Pregnancies | 4.5 | [±2.4] | 4.0 | [± 2.3] | 0.006 | ||

| n | % | n | % | ||||

| Mother’s Education | |||||||

| No education | 619 | (73.4) | 612 | (74.2) | 0.891 | ||

| Primary | 121 | (14.2) | 103 | (12.9) | 0.645 | ||

| Middle | 25 | (2.8) | 33 | (4.1) | 0.252 | ||

| Secondary | 42 | (4.3) | 26 | (3.5) | 0.654 | ||

| Intermediate or above | 53 | (5.3) | 50 | (5.3) | 0.984 | ||

| Wealth Quantile | |||||||

| Poorest | 59 | (6.6) | 276 | (32.9) | <0.001 | ||

| Poor | 167 | (20.2) | 169 | (20.2) | 0.990 | ||

| Middle | 214 | (25.4) | 125 | (16.0) | 0.009 | ||

| Rich | 202 | (24.0) | 136 | (16.6) | 0.039 | ||

| Richest | 218 | (23.8) | 118 | (14.2) | 0.090 | ||

| Baseline | Endline | DiD* | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Matiari N=860 |

Badin N=824 |

Matiari N= 860 |

Badin N=873 |

diff | p value | |||||||||

| N | n | % | N | n | % | N | n | % | N | n | % | |||

| Currently using any method to delay pregnancy | 860 | 242 | (28.0) | 824 | 220 | (26.7) | 880 | 353 | (40.0) | 873 | 251 | (28.4) | (10) | 0.003 |

| Currently using a modern method to delay pregnancy | 860 | 224 | (25.9) | 824 | 217 | (26.4) | 880 | 334 | (37.9) | 873 | 224 | (26.9) | (11.3) | <0.001 |

| Female Sterilization | 860 | 68 | (8.0) | 824 | 41 | (5.2) | 880 | 62 | (7.3) | 873 | 52 | (5.3) | (-1.4) | 0.531 |

| Male Sterilization | 860 | 0 | (0.0) | 824 | 1 | (0.2) | 880 | 1 | (0.1) | 873 | 0 | (0.0) | (0.2) | 0.312 |

| IUD (Intrauterine Device) | 860 | 7 | (0.9) | 824 | 5 | (0.5) | 880 | 10 | (1.1) | 873 | 3 | (0.2) | (0.6) | 0.339 |

| Injection | 860 | 33 | (3.8) | 824 | 30 | (3.6) | 880 | 85 | (9.5) | 873 | 26 | (4.5) | (8.7) | <0.001 |

| Implants | 860 | 26 | (2.9) | 824 | 15 | (1.8) | 880 | 39 | (4.3) | 873 | 11 | (1.7) | (1.3) | 0.279 |

| Pills | 860 | 43 | (5.6) | 824 | 40 | (4.8) | 880 | 62 | (7.0) | 873 | 51 | (7.6) | (0.5) | 0.831 |

| Condom | 860 | 45 | (5.2) | 824 | 42 | (5.1) | 880 | 66 | (7.5) | 873 | 28 | (2.4) | (5.2) | 0.006 |

| SDM (Standard Days Method) | 860 | 1 | (0.1) | 824 | 0 | (0.0) | 880 | 2 | (0.2) | 873 | 4 | (0.3) | (-0.4) | 0.186 |

| Lactation Amenorrhea Method (LAM) | 860 | 2 | (0.2) | 824 | 4 | (0.4) | 880 | 9 | (0.8) | 873 | 49 | (5.0) | (-3.4) | 0.003 |

| Currently using a traditional method to delay pregnancy | 860 | 18 | (2.1) | 824 | 4 | (0.4) | 880 | 19 | (2.1) | 873 | 27 | (1.6) | (-1.0) | 0.381 |

| Rhythm method | 860 | 1 | (0.1) | 824 | 2 | (0.2) | 880 | 3 | (0.4) | 907 | 2 | (0.2) | (0.2) | 0.102 |

| Withdrawal | 860 | 17 | (1.9) | 824 | 2 | (0.2) | 880 | 16 | (1.7) | 907 | 25 | (1.4) | (0.7) | 0.513 |

| Aware of a method to delay pregnancy | 860 | 725 | (84.9) | 824 | 530 | (65.1) | 880 | 776 | (88.24) | 873 | 835 | (95.2) | (-27.1) | <0.001 |

| Baseline | Endline | DiD* | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Matiari N=413 |

Badin N=448 |

Matiari N=395 |

Badin N=427 |

diff | P-Value | |||||||||

| N | n | % | N | n | % | N | n | % | N | n | % | |||

| ANC Sought | 413 | 379 | (92.8) | 448 | 387 | (86.4) | 390 | 373 | (95.8) | 426 | 395 | (94.4) | (-.9) | 0.093 |

| 4 or more ANC Visits | 413 | 205 | (49.1) | 448 | 166 | (37.9) | 390 | 224 | (57.4) | 426 | 234 | (47.4) | (10.50) | 0.003 |

| FP counseling during ANC Check-up | 413 | 11 | (2.0) | 448 | 34 | (7.9) | 390 | 148 | (38.0) | 426 | 70 | (16.43) | (15.60) | <0.001 |

| LHW Visited during pregnancy | 413 | 214 | (55.1) | 448 | 389 | (87.0) | 390 | 318 | (82.2) | 426 | 419 | (98.7) | (15.1) | 0.021 |

| Facility births | 413 | 304 | (75.3) | 448 | 374 | (83.7) | 390 | 369 | (94.5) | 426 | 386 | (86.4) | (15.3) | <0.001 |

| Skilled Birth Attendant | 413 | 305 | (75.5) | 448 | 373 | (83.5) | 390 | 372 | (95.3) | 426 | 386 | (86.0) | (16.4) | <0.001 |

| PNC checkup-mother | 413 | 180 | (43.9) | 448 | 337 | (75.4) | 390 | 272 | (70.3) | 426 | 343 | (78.0) | (25.2) | <0.001 |

| LHW Visited after delivery | 413 | 155 | (38.9) | 448 | 363 | (81.3) | 390 | 295 | (75.7) | 426 | 414 | (97.5) | (20.4) | <0.001 |

| LHW advised for family planning in PNC visit | 413 | 72 | (19.5) | 448 | 118 | (25.4) | 390 | 183 | (46.5) | 426 | 136 | (32.0) | (14.50) | 0.030 |

| Fully Immunized a | 310 | 108 | (37.7) | 336 | 72 | (21.9) | 394 | 234 | (59.4) | 426 | 269 | (64.3) | (-17) | 0.027 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).