Submitted:

19 April 2023

Posted:

20 April 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Questionnaire

2.2. Data Analysis

2.3. Ethical Approval

3. Results

3.1. Demographic Data

3.2. Initial Feelings on Diagnosis of PKU

| Parental Feelings/Emotions on PKU diagnosis | % (n) | % (n) | |

| Sad Anxious Overwhelmed Confused Exhausted |

83 (141) 81 (136) 81 (136) 57 (97) 40 (68) |

Lonely Angry Neutral Calm Relaxed |

38 (64) 36 (60) 3 (5) 2 (3) <1 (1) |

| Common thematic open ended responses | |||

| Fear of the unknown/lack of knowledge | 15 (26) | ||

|

I didn’t know what PKU was or what it meant for my baby. Too much to take in, I had never heard of PKU. I didn’t understand it so I was scared. It took a lot of time to understand the condition and to fully comprehend the care needed in order to keep [her] safe. Scared of the unknown. What would the future be like for my child. I actually remember thinking I wish my child had another disease that she could be cured of as she was never going to be free of PKU. I thought she was going to have a very poor quality of life. We were told to get to the hospital immediately. We hadn’t a clue what was happening. |

|||

| Overwhelming | 8 (13) | ||

|

Never got over it - felt been hit by a train. It was heart breaking, I still cry. Felt like a massive life changing event and left to deal with it. When my child was approaching 1 year I had an emotional breakdown coming to terms with his diagnosis and all that it entailed for me. |

|||

| Shock | 5 (9) | ||

|

[He] is my 7th child and my only one with PKU -it came as a complete shock. It was a shock and caused us a lot of worry especially as an older cousin in the family has PKU with learning difficulties. |

|||

| How the diagnosis was conveyed | 5 (8) | ||

|

I was given the diagnosis over the phone out of hours and told to be at the hospital first thing the next morning, this led to a sleepless night as we were provided with minimal information and no support or guidance. We were told face to face in our house and I think this is the best way for this to be done. The midwife told us it could lead to brain damage and learning difficulties, those words stuck in mine and my partners mind when we didn’t know any other information about it or the fact that he will be fine on a low protein diet. I was told over the phone and I didn’t understand at all. There was no emotional support. Before the midwife took the heel prick she said he won’t have any of these conditions they are very rare. GPs just raved about how fantastic it was that it could be treated with diet., I feel the support at diagnosis was really poor/non-existent. I was called by a nurse who gave us the shocking and life-changing diagnosis and told us not to Google it but to look at the information she would email us. We did not receive an email until over an hour later. It’s unrealistic to tell people not to look it up on the internet. |

|||

| Diagnosis with knowledge of PKU i.e. sibling or relative | 5 (8) | ||

|

1st baby (PKU); Absolutely broken. World had come crashing down around me. 2nd & 3rd babies (1 PKU, 1 not); Peace. Acceptance. Intense love. We all deal with whatit is. There are pros and cons but ultimately, PKU is just a difference. If I had a no. 4 it wouldn’t phase me as to whether they had PKU or not. We were already aware of PKU due to another family member and that its manageable by diet so we didn’t have the initial fears that parents that haven’t heard of PKU would have. |

|||

| Guilt | 4 (7) | ||

|

Intense guilt for having wanted my son so badly and yet giving him this burden of a life (as I saw it then). Thinking that it was caused by us as parents. |

|||

| Isolation | 3 (5) | ||

|

Feeling of having to face the illness alone was exacerbated due to lack of any extended family within the county (parents, siblings, grandparents). I felt hugely isolated and lonely in the 1st 5 years. |

|||

| Resignation/acceptance | 3 (5) | ||

|

Me and the husband said it is what it is, having PKU doesn’t affect quality of life, our daughter will still develop normally. We can either cry about it or just get on with it, so we’ve decided to just get on with it and support our daughter in any way we can. Ultimately, PKU is just a difference. |

|||

3.3. Support from and Trust in Healthcare Professionals

| Very helpful/ helpful (score 4,5) |

Neutral (score 3) |

Not very / not helpful (score 1,2) |

Not applicable |

|

| How helpful was the support from different HCPs in the early years of a PKU diagnosis (%) | ||||

| Dietitian | 92 | 4 | 4 | 1 |

| Nurse | 64 | 17 | 9 | 11 |

| Hospital Dr | 50 | 22 | 21 | 7 |

| Health visitor | 22 | 17 | 58 | 3 |

| GP | 12 | 16 | 66 | 7 |

| Psychologist | 5 | 3 | 14 | 78 |

| How much do you trust the information provided by healthcare professionals (%) | ||||

| Dietitian | 94 | 4 | 1 | 1 |

| Nurse | 73 | 12 | 3 | 12 |

| Hospital Dr | 61 | 16 | 16 | 7 |

| Health visitor | 22 | 15 | 58 | 6 |

| GP | 15 | 17 | 59 | 9 |

| Psychologist | 6 | 4 | 13 | 75 |

- It is absolutely crucial to have a consistent person to deal with when learning about PKU. Someone who actually knows your family and the child with PKU.

- GPs don’t know what PKU is. I feel I have to inform them when I see them.

- The support from the health visitor did not extend to making any effort to understand PKU or what that might mean. There appeared to be no attempt to liaise with the hospital.

- There was no emotional support and no follow up at all regarding my own well-being.

3.4. Where Parents Go for Support and Information

- Dietitan – a lot of support, mentally and emotionally.

- Our dietician has been exceptional and couldn’t have provided any higher standard of support…. She has been our rock.

- The most supportive place I have found is the Facebook PKU group. There are always people to answer questions and lots of great food ideas are shared.

| Very helpful/ helpful (score 4,5) |

Neutral (score 3) |

Not very / not helpful (score 1,2) |

Not applicable |

|

| Who do you go to for support, who listens to your concerns and makes you feel better (%) | ||||

| Family | 53 | 22 | 21 | 3 |

| Other PKU parents | 53 | 12 | 13 | 21 |

| NSPKU | 52 | 10 | 21 | 17 |

| Friends | 28 | 30 | 36 | 6 |

| NSPKU conferences | 19 | 10 | 19 | 52 |

| How much do you trust PKU information provided (%) | ||||

| Information books | 74 | 16 | 8 | 2 |

| NSPKU | 68 | 7 | 17 | 9 |

| Other PKU parents | 54 | 16 | 15 | 14 |

| Hospital PKU events | 53 | 6 | 11 | 30 |

| Company learning packages | 43 | 16 | 24 | 17 |

| NSPKU conferences | 27 | 3 | 21 | 49 |

| Family | 12 | 15 | 56 | 17 |

| Friends | 9 | 7 | 63 | 21 |

- the conference was really useful as this was the first time I was able to meet other families and started to feel less isolated.

- Cooking demonstrations were really helpful and gave me confidence with the [low protein] products, which I needed despite being a competent cook with ‘regular’ food.

3.5. Use of Social Media for Support and Information

| Very helpful/ helpful (score 4,5) |

Neutral (score 3) |

Not very / not helpful (score 1,2) |

Not applicable |

|

| How helpful are social media sites at providing support for PKU (%) | ||||

| 68 | 13 | 12 | 9 | |

| 52 | 8 | 9 | 30 | |

| 27 | 11 | 19 | 43 | |

| YouTube | 16 | 16 | 20 | 50 |

| Internet Forums | 7 | 2 | 27 | 67 |

| How helpful are social media sites at providing information for PKU (%) | ||||

| 69 | 11 | 12 | 7 | |

| 59 | 3 | 9 | 29 | |

| 25 | 11 | 19 | 45 | |

| YouTube | 19 | 11 | 20 | 50 |

| Internet Forums | 7 | 2 | 27 | 65 |

| Themes | % (n) |

| Support/understanding, sense of community/belonging | 51 (56) |

|

Offloading, emotional support. Makes you feel like a PKU family as do not know anyone locally with same condition Solidarity and understanding from a community of people who "get it" in a way others don’t. Being able to empathise with other parents who are going/have gone through similar things as well as being able to help other parents feel part of a PKU family where we share ideas and ask for advice. It’s good to know we’re not alone and we can laugh, cry or moan about PKU related stuff. We congratulate each other for a good blood spot test, and support each other when a little one goes off their formula. |

|

| Quick access to hints, tips, advice, solutions to problems and potential ideas | 40 (44) |

|

Answers and ideas from people who live with PKU day in, day out. Quick and helpful responses of things I’m not sure about and need to know quickly. Don’t even have to engage with people as can just search for things people have added in the past. Good for ideas. But for proper information I go to my dietitian. |

|

| Food/meal/recipe ideas | 40 (44) |

|

Loads of recipe ideas and new product finds. Different foods available I may not have seen. I’m able to ask about certain foods which if I didn’t have this group I would be constantly bothering the dietitians! Ideas for meals to cook. |

|

| Reassurance | 10 (11) |

|

Reassurance that things will be okay. To hear other parents struggling with similar issues we have so we know it’s normal to have bad days. Comfort in knowing I’m not the only parent going through this. |

|

| Negative experiences | 7 (8) |

|

Don’t ask for advice as often there are mixed opinions and often turns quite negative Interesting to see other views, but it’s often conflicting and can be quite argumentative if people disagree with your approach. Some people who post I don’t trust their calculations of exchanges. There’s a lot of misinformation out there. I don’t trust what is said. I only trust my dietitian. She knows what she is talking about. |

| Themes | % (n=104) |

| Pros | |

|

For expertise and advice: It would be helpful to have a trusted social media site to visit for reference. Some more professional advice online could be good as PKU is very complicated and not all nutritional information on food packages is easy to understand. Twitter is good because there are dietitians on there who give great support and advice. It’s a good way to communicate. Some people don’t like talking on the phone, can send a quick message on social media more easily. To correct inaccurate information: I find a lot of people’s calculations online are not right. It would be better if health professionals gave this information. Sometimes what has been said may not be correct so if they see wrong information being shared, would be useful for them to set the record straight. This would give me more confidence in the knowledge we receive and stop a lot of conflictive responses. To learn about PKU from a parent/patient perspective: I feel like they would gain a lot more knowledge just from being in the groups and looking at the information others provide and the struggles we all face as parents with children who have PKU or as adults who have PKU. They would have more of an understanding of what our worries are and what sort of questions we ask. |

32 (35) 12 (12) 9 (9) |

| Cons | |

|

People may feel less inclined to share/it is for sharing opinions: People might not open up as much to professionals as they do to other parents, therefore they get more out of it if professionals stay away. Sometimes parents want to write about a particular difficulty they having with a healthcare professional and look to other parents for advice in how to deal with that. Parents should be free to make comments without scrutiny from healthcare professionals. Not their role/too busy/no time: I don’t think health care professionals would have time to become involved in social media groups. It would be helpful for us, but they need their private time and life. Input from different hospitals/centres: They would get lots of questions from people who weren’t in their care. Too vast to control the quantity of people’s ideas and challenge behaviour especially when they are led by varying trusts and dieticians with different principles of care. Professional vulnerability I feel that health care professionals would be vulnerable to the abuse associated with a lot of social media. Professionals could be subjected to difficult comments. |

10 (10) 10 (10) 6 (6) 4 (4) |

| Other options | |

|

Don’t rely on Facebook for facts, would go back to dietitian I would always go back for official advice from our dietitians. It’s tough because I wouldn’t trust the majority of the information on social media as some of it is coming from people who are off diet and think there doing fantastic and some is from people who have no clue. But then I see posts about some people unable to see their consultant or dietictan to ask questions so they turn to Facebook for advice. It’s not ideal but there making the best out of the situation. Separate groups for HCP and parents or specific times for HCPs to join in Perhaps have a drop in slot where they can answer generic questions i.e. on exchange values or suitable medication. It would be helpful if there was a dedicated time on social media where parents could chat about concerns in a more relaxed way, sometimes I don’t want to ring up to the hospital as it feels like I’m being a pain. |

7 (7) 3 (3) |

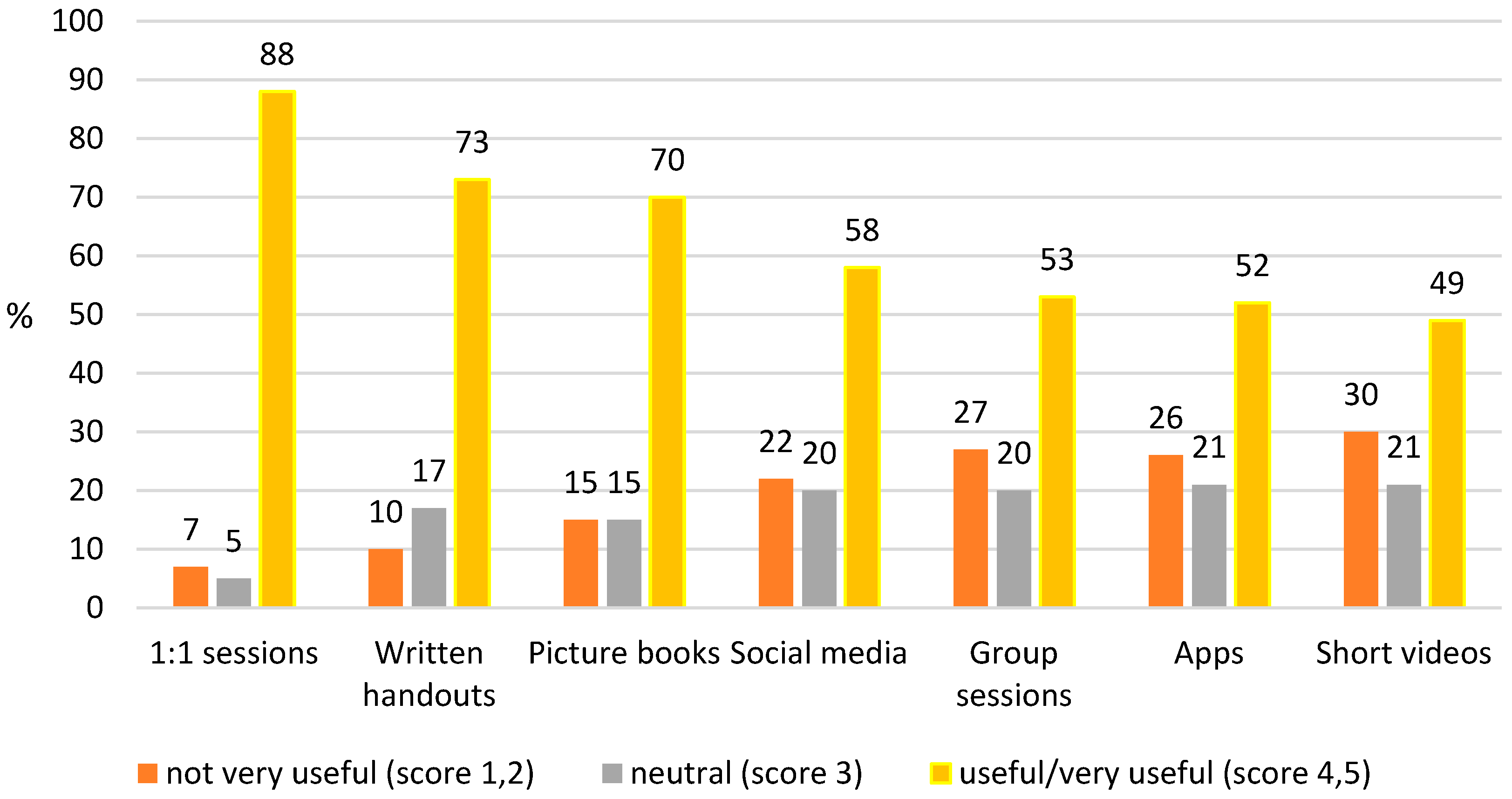

3.6. Preferred Method of Obtaining Dietary Information

- I prefer to do things through my dietitian. We feel safe this way.

- Early on I preferred to have the dietitian there throughout the process, but with time I do feel more confident to do my own research.

3.7. Early Education Received

- I think it was assumed that because I was already breastfeeding, the best thing would be to continue. However we couldn’t get the hang of switching between bottle and breast. I tried expressing but the assumption from support sources seemed to be that this was a temporary measure, and my pump loan was taken back.

- I had a distressing comment from the breastfeeding support worker who told me “Children wouldn’t have survived" with PKU in the past. This terrified me and she clearly had no idea what PKU was as this isn’t true.

- The early feeding support was handled by midwives and breastfeeding advisors but I would have preferred more input from people who knew the specific challenges of early PKU feeding.

- More training for dietitians on [breast] feeding would have been beneficial as I believe they are in the best place to advise and support from the beginning.

| Advice given | % (n) receiving advice |

|---|---|

| How to take a blood test | 93 (156)* |

| When to take a blood test | 82 (137)* |

| Immunisations | 59 (99)** |

| Child development e.g. speech/language | 38 (63)** |

| Vitamin supplements | 30 (50)** |

| Dental hygiene | 25 (42)** |

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- van Wegberg, A. M. J., A. MacDonald, K. Ahring, A. Belanger-Quintana, N. Blau, A. M. Bosch, A. Burlina, J. Campistol, F. Feillet, M. Gizewska, S. C. Huijbregts, S. Kearney, V. Leuzzi, F. Maillot, A. C. Muntau, M. van Rijn, F. Trefz, J. H. Walter, and F. J. van Spronsen. "The Complete European Guidelines on Phenylketonuria: Diagnosis and Treatment." Orphanet J Rare Dis 12, no. 1 (2017): 162. [CrossRef]

- Loeber, J. Gerard. "Neonatal Screening in Europe; the Situation in 2004." Journal of Inherited Metabolic Disease 30, no. 4 (2007): 430-38. [CrossRef]

- von der Lippe, C., P. S. Diesen, and K. B. Feragen. "Living with a Rare Disorder: A Systematic Review of the Qualitative Literature." Mol Genet Genomic Med 5, no. 6 (2017): 758-73. [CrossRef]

- Gunduz, M., N. Arslan, O. Unal, S. Cakar, P. Kuyum, and S. F. Bulbul. "Depression and Anxiety among Parents of Phenylketonuria Children." Neurosciences (Riyadh) 20, no. 4 (2015): 350-6. [CrossRef]

- Mahmoudi-Gharaei, J., Nargess Mostafavi S Fau - Alirezaei, and N. Alirezaei. "Quality of Life and the Associated Psychological Factors in Caregivers of Children with Pku." Iran J Psychiatry 6 (2011): 66-69.

- Fidika, Astrid, Christel Salewski, and Lutz Goldbeck. "Quality of Life among Parents of Children with Phenylketonuria (Pku)." Health and Quality of Life Outcomes 11, no. 1 (2013): 54. [CrossRef]

- Kazak, A. E., M. Reber, and L. Snitzer. "Childhood Chronic Disease and Family Funcitoning: A Study of Phenylketonuria." Pediatrics 81, no. 2 (1988): 224-30.

- ten Hoedt, A. E., H. Maurice-Stam, C. C. Boelen, M. E. Rubio-Gozalbo, F. J. van Spronsen, F. A. Wijburg, A. M. Bosch, and M. A. Grootenhuis. "Parenting a Child with Phenylketonuria or Galactosemia: Implications for Health-Related Quality of Life." J Inherit Metab Dis 34, no. 2 (2011): 391-8. [CrossRef]

- Casey, L. "Caring for Children with Phenylketonuria." Canadian Family Physician 59, no. 8 (2013): 837-40.

- Bernstein, L. E., J. R. Helm, J. C. Rocha, M. F. Almeida, F. Feillet, R. M. Link, and M. Gizewska. "Nutrition Education Tools Used in Phenylketonuria: Clinician, Parent and Patient Perspectives from Three International Surveys." J Hum Nutr Diet 27 Suppl 2 (2014): 4-11. [CrossRef]

- Pate, T., M. Rutar, T. Battelino, M. Drobnic Radobuljac, and N. Bratina. "Support Group for Parents Coping with Children with Type 1 Diabetes." Zdr Varst 54, no. 2 (2015): 79-85.

- "Facebook Statistics You Must Know in 2023." Herd Digital, https://herd.digital/blog/facebook-statistics-2022/#:~:text=Interesting%20Facebook%20Statistics%201%20Facebook%20is%20the%20most,Stories%20has%20500%20million%20daily%20viewers.%20More%20items (accessed 11 March 2023).

- Duggan, M. "Mobile Messaging and Social Media - 2015." Pew research Center. Available at: http://www.pewinternet.org/2015/08/19/mobile-messaging-and-social-media-2015/ accessed 11/3/23 (2015).

- Hickson, M., J. Child, and A. Collinson. "Future Dietitian 2025: Informing the Development of a Workforce Strategy for Dietetics." Journal of Human Nutrition and Dietetics 31, no. 1 (2018): 23-32. [CrossRef]

- Nowell, Lorelli S., Jill M. Norris, Deborah E. White, and Nancy J. Moules. "Thematic Analysis." International Journal of Qualitative Methods 16, no. 1 (2017).

- Collini, A., H. Parker, and A. Oliver. "Training for Difficult Conversations and Breaking Bad News over the Phone in the Emergency Department." Emerg Med J 38, no. 2 (2021): 151-54. [CrossRef]

- Chudleigh, J., P. Holder, L. Moody, A. Simpson, K. Southern, S. Morris, F. Fusco, F. Ulph, M. Bryon, J. R. Bonham, and E. Olander. "Process Evaluation of Co-Designed Interventions to Improve Communication of Positive Newborn Bloodspot Screening Results." BMJ Open 11, no. 8 (2021): e050773.

- Pelentsov, L. J., A. L. Fielder, T. A. Laws, and A. J. Esterman. "The Supportive Care Needs of Parents with a Child with a Rare Disease: Results of an Online Survey." BMC Fam Pract 17 (2016): 88. [CrossRef]

- Waisbren, S. E. "Parents’ Reactions after the Birth of a Developmentally Disabled Child." AM J Ment Defic 84, no. 4 (1980): 345-51.

- Garrubba, M., and G. Yap. "Trust in Health Professionals." Centre for Clinical Effectiveness, Monash Health, Melbourne, Australia. (2019).

- Young-Hyman, D., M. de Groot, F. Hill-Briggs, J. S. Gonzalez, K. Hood, and M. Peyrot. "Psychosocial Care for People with Diabetes: A Position Statement of the American Diabetes Association." Diabetes Care 39, no. 12 (2016): 2126-40. [CrossRef]

- Batchelor, L.L. , and G. Duke. "Chronic Sorrow in Parents with Chronically Ill Children." Pediatric Nursing 45, no. 4 (2019): 163-73,83.

- Beresford, B. A. "Resources and Strategies: How Parents Cope with the Care of a Disabled Child." j Clin Psychol Psychiatry 35, no. 1 (1994): 171-209. [CrossRef]

- Amichai-Hamburger, Yair, and Shir Etgar. "Intimacy and Smartphone Multitasking—a New Oxymoron?" Psychological Reports 119, no. 3 (2016): 826-38.

- Gerson, Jennifer, Anke C. Plagnol, and Philip J. Corr. "Passive and Active Facebook Use Measure (Paum): Validation and Relationship to the Reinforcement Sensitivity Theory." Personality and Individual Differences 117 (2017): 81-90. [CrossRef]

- Kirk, S., and L. Milnes. "An Exploration of How Young People and Parents Use Online Support in the Context of Living with Cystic Fibrosis." Health Expect 19, no. 2 (2016): 309-21. [CrossRef]

- Cardinali, P., L. Migliorini, and N. Rania. "The Caregiving Experiences of Fathers and Mothers of Children with Rare Diseases in Italy: Challenges and Social Support Perceptions." Front Psychol 10 (2019): 1780. [CrossRef]

- Plantin, L., and K. Daneback. "Parenthood, Information and Support on the Internet. A Literature Review of Research on Parents and Professionals Online." BMC Fam Pract 10 (2009): 34. [CrossRef]

- Witalis, E., B. Mikoluc, R. Motkowski, J. Szyszko, A. Chrobot, B. Didycz, A. Lange, R. Mozrzymas, A. Milanowski, M. Nowacka, M. Piotrowska-Depta, H. Romanowska, E. Starostecka, J. Wierzba, M. Skorniewska, B. I. Wojcicka-Bartlomiejczyk, M. Gizewska, and Phenylketonuria Polish Society of. "Phenylketonuria Patients’ and Their Parents’ Acceptance of the Disease: Multi-Centre Study." Qual Life Res 25, no. 11 (2016): 2967-75. [CrossRef]

- Broom, Alex. "Virtually He@Lthy: The Impact of Internet Use on Disease Experience and the Doctor-Patient Relationship." Qualitative Health Research 15, no. 3 (2005): 325-45. [CrossRef]

- Barak, Azy, Meyran Boniel-Nissim, and John Suler. "Fostering Empowerment in Online Support Groups." Computers in Human Behavior 24, no. 5 (2008): 1867-83. [CrossRef]

- Patel, R., T. Chang, S. R. Greysen, and V. Chopra. "Social Media Use in Chronic Disease: A Systematic Review and Novel Taxonomy." Am J Med 128, no. 12 (2015): 1335-50. [CrossRef]

- Partridge, Stephanie R, Patrick Gallagher, Becky Freeman, and Robyn Gallagher. "Facebook Groups for the Management of Chronic Diseases." J Med Internet Res 20, no. 1 (2018): e21. [CrossRef]

- Schoenebeck, S. "The Secret Life of Online Moms: Anonymity and Disinhibition on Youbemom.Com. ." Proceedings of the international AAAI Conference on Web and Social Media 7, no. 1 (2013): 555-62.

- Leask, J., P. Kinnersley, C. Jackson, F. Cheater, H. Bedford, and G. Rowles. "Communicating with Parents About Vaccination: A Framework for Health Professionals." BMC Pediatr 12 (2012): 154. [CrossRef]

- Taherdoost, H. "What Is the Best Response Scale for Survey and Questionnaire Design; Review of Different Lengths of Rating Scale/ Attitude Scale/ Likert Scale." Int J Acad Res Manag 8, no. 1 (2019): 1-10.

- Bishop, P. A., and R. L. Herron. "Use and Misuse of the Likert Item Responses and Other Ordinal Measures." no. 1939-795X (Print) (2015).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).