Submitted:

19 April 2023

Posted:

20 April 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Electrochemical Oxidation (EO)

2.1. Study of electro-oxidation operating parameters

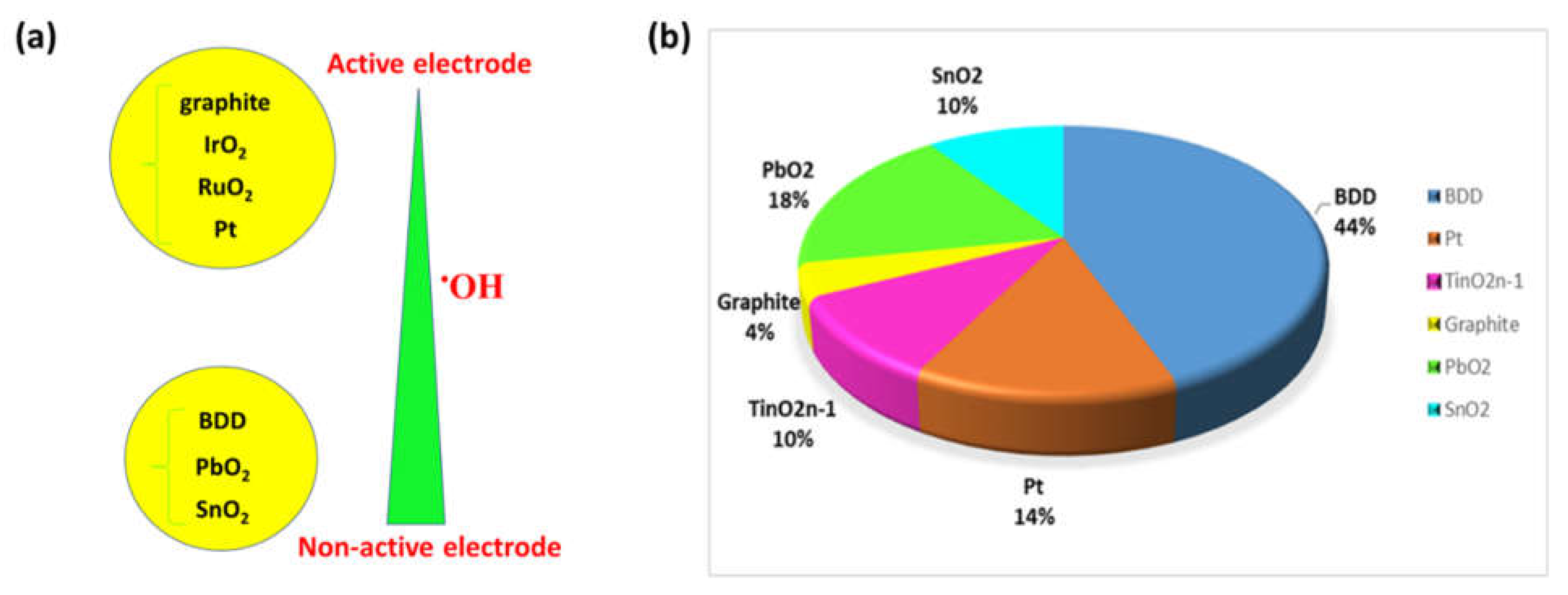

2.1.1. Effect of the anode material

| Electrode (Anode) | Disadvantages | Advantages | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|

| Magneli-phase titanium suboxides TinO2n-1 | Expensive, difficult to manufacture in high volume, the process requires a 2-step process with chemical reduction at >900C | High corrosion resistance in acidic and basic solutions, high electrical conductivity, high electrochemical stability, ability to coat numerous substrates with the Ti4O7 powders including Titanium and the likes, high oxygen evolution rate with high potential | [20] |

| Boron-doped diamond (BDD) | High cost | High stability, produce large amounts of oxidants, high oxygen evolution rate with high potential, low adsorbtion, very resistant to corrosion, inert surface | [21] |

| PbO2 | Toxic effect, lead ions may be released into the test solution and cause problems | High oxygen evolution rate with high potential, availability, low cost, easy manufacturing | [22] |

| Graphite | Corrosion, especially at high potentials, very low efficiency in electrooxidation | Cheap and easily available | [23] |

| Pt | High cost, low efficiency in anodic oxidation | High stability, and easily available; no need for additional processes | [24] |

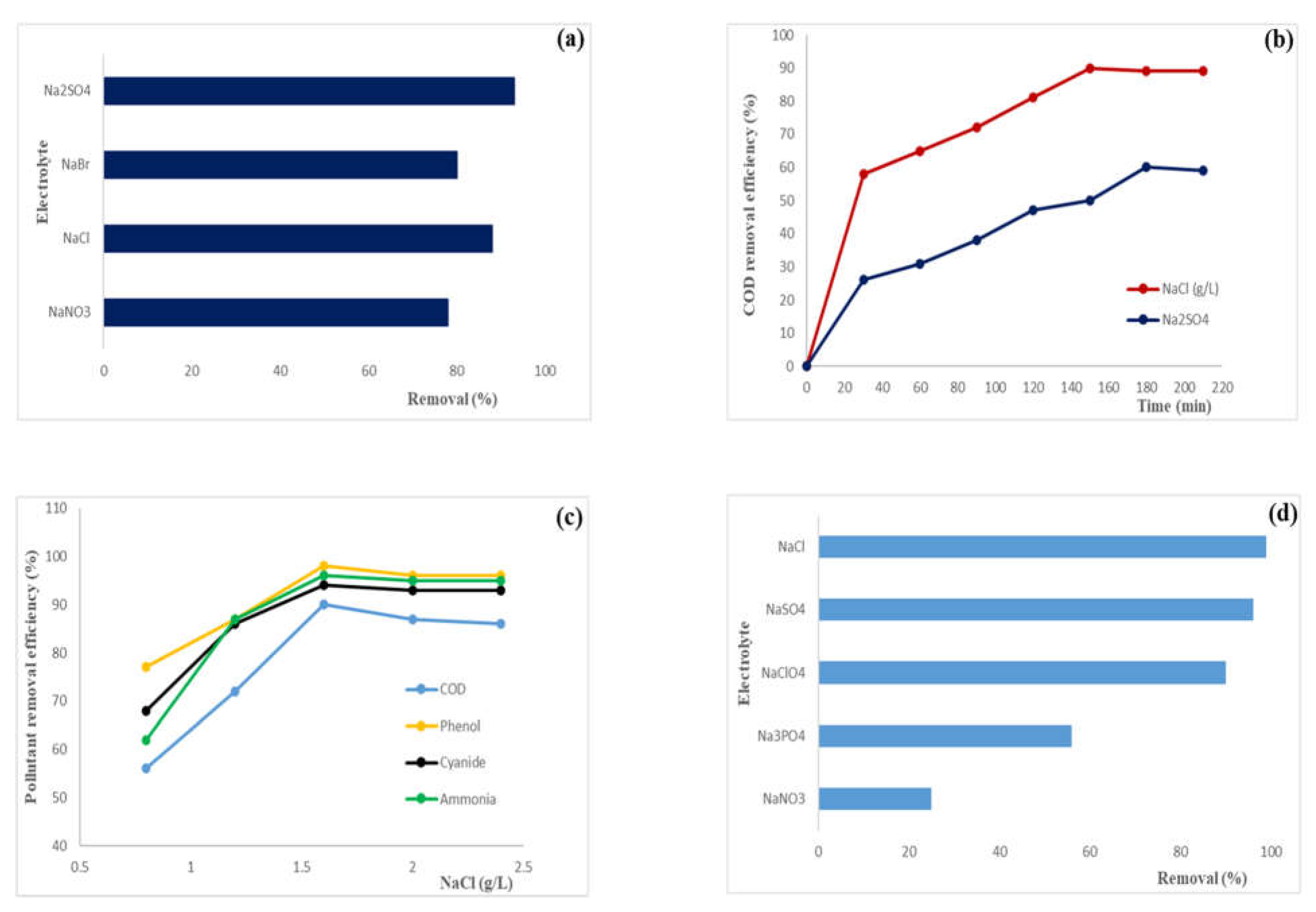

2.1.2. Effect of the supporting electrolyte and electrolyte concentration

| Electrode (Anode) | Pollutants | Electrolyte | Removal efficiency (%) |

Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| BDD | Linear PFOS | Na2SO4 (100 mM) | 85.7% | [27] |

| BDD | Branched PFOS | Na2SO4 (100 mM) | 84.6% | [27] |

| BDD | PFOA | Na2SO4 (14.2 g/L) | 99.5% | [28] |

| BDD (high boron doping) | PFOA (0.1 mg/L) (water matrix) | Phosphate buffer (100 mM) | 95% | [29] |

| BDD (low boron doping) | PFOS (0.1 mg/L) (water matrix) | Phosphate buffer (100 mM) | 84% | [29] |

| [(Ti1− xCex)4O7] | PFOS | NaClO4 (0.1 M) | 98.9 ± 0.3 | [30] |

| Ti4O7 | PFOS | NaClO4 (0.1 M) | 86.2 ± 2.9 | [30] |

| Ti4O7/ amorphous Pd | PFOA | Na2SO4 (50 mM) | 86.7 ± 6.3 | [31] |

| Ti4O7 | Linear PFOS | Na2SO4 (100 mM) | 98.6% | [27] |

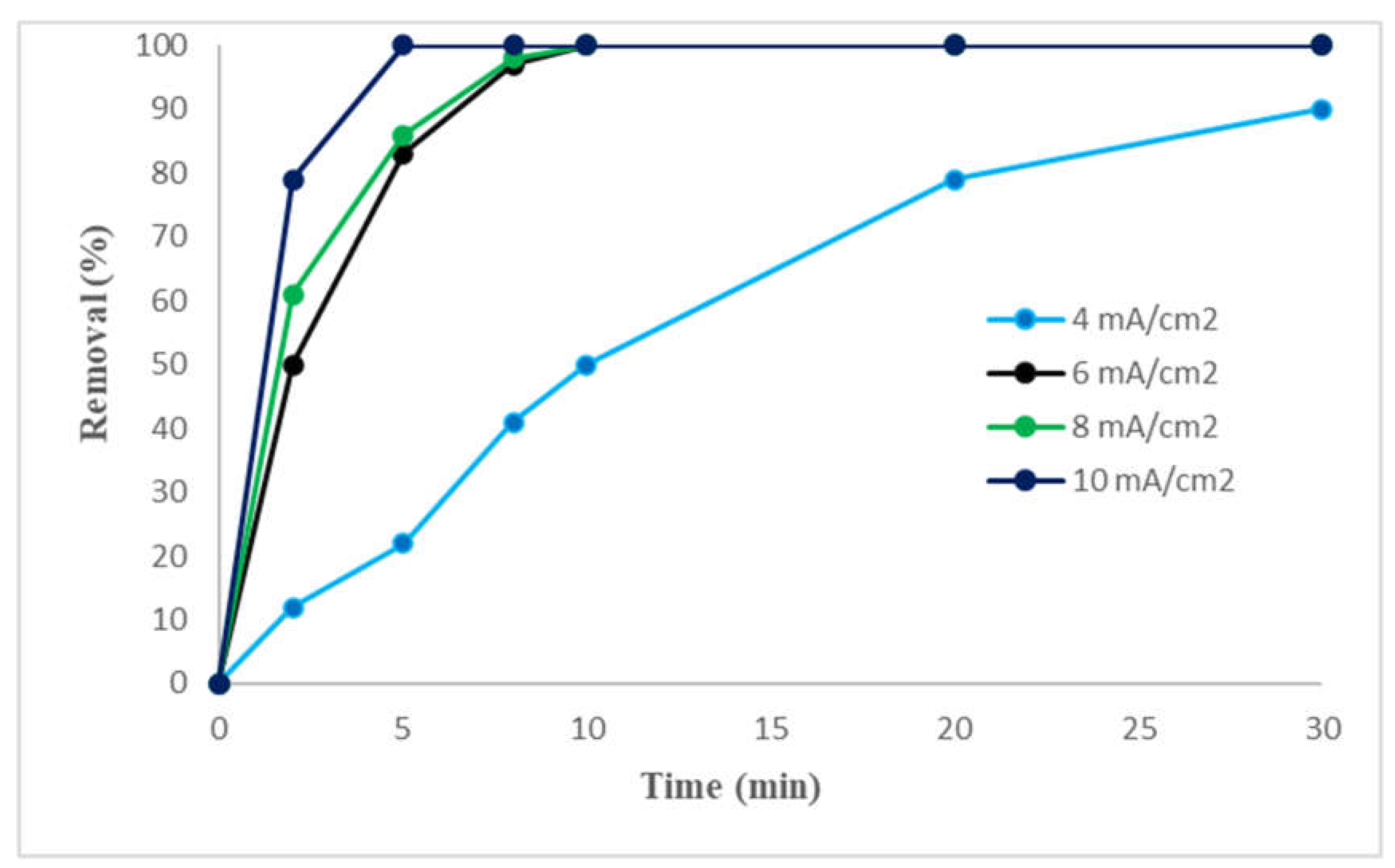

2.1.3. Effect of the current density

2.1.4. Effect of the other operating parameters

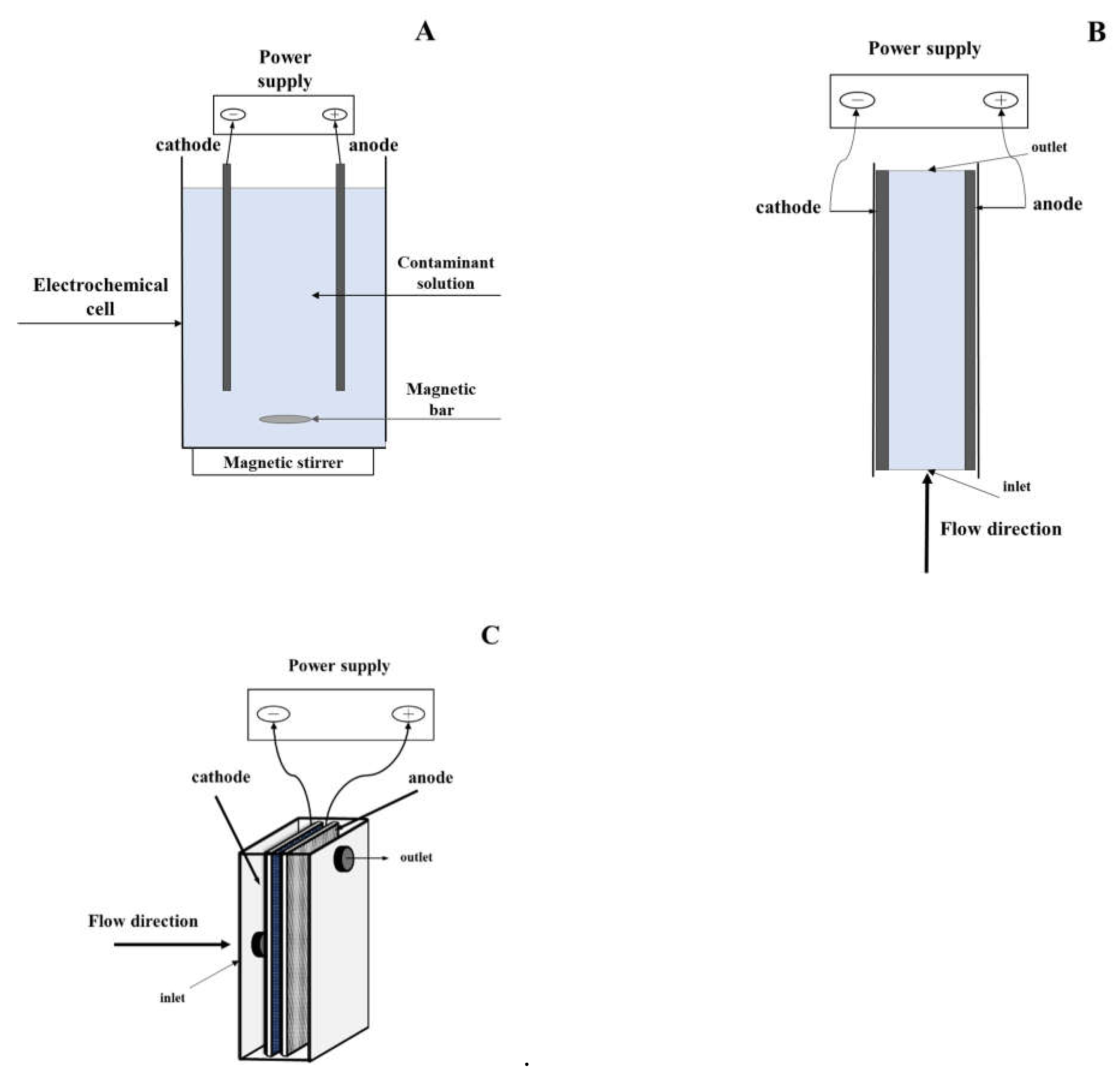

2.2. Electrochemical reactor design

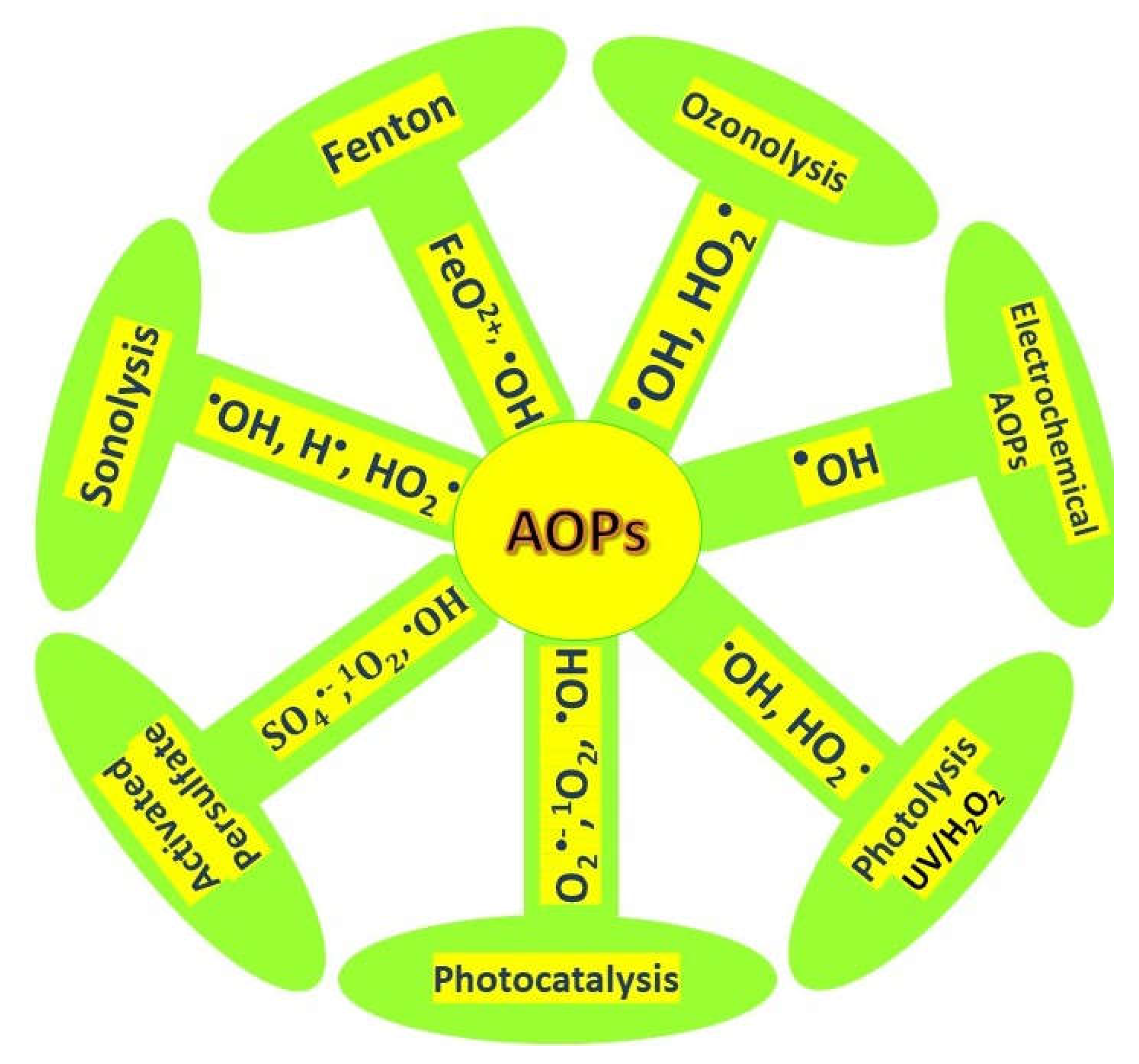

3. Mechanism of electrochemical oxidation of organic pollutants

3.1. Direct EO

3.2. Indirect EO

3.3. EO degradation kinetics

4. Cost analysis and energy consumption

5. Combination of EO with photocatalysis

5.1. Photoelectrocatalysis (PEC)

6. Conclusions and future perspectives

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Okoffo, E.D.; Rauert, C.; Thomas, K. V. Mass Quantification of Microplastic at Wastewater Treatment Plants by Pyrolysis-Gas Chromatography–Mass Spectrometry. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 856, 159251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sandoval, M.A.; Vidal, J.; Calzadilla, W.; Salazar, R. Solar (Electrochemical) Advanced Oxidation Processes as Efficient Treatments for Degradation of Pesticides. Curr. Opin. Electrochem. 2022, 36, 101125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morin-Crini, N.; Lichtfouse, E.; Liu, G.; Balaram, V.; Ribeiro, A.R.L.; Lu, Z.; Stock, F.; Carmona, E.; Teixeira, M.R.; Picos-Corrales, L.A.; et al. Worldwide Cases of Water Pollution by Emerging Contaminants: A Review. Environ. Chem. Lett. 2022, 20, 2311–2338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iovino, P.; Fenti, A.; Galoppo, S.; Najafinejad, M.S.; Chianese, S.; Musmarra, D. Electrochemical Removal of Nitrogen Compounds from a Simulated Saline Wastewater. Molecules 2023, 28, 1306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salvestrini, S.; Fenti, A.; Chianese, S.; Iovino, P.; Musmarra, D. Diclofenac Sorption from Synthetic Water: Kinetic and Thermodynamic Analysis. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2020, 8, 104105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saleem, H.; Arslan, M.; Rehman, K.; Tahseen, R.; Afzal, M. Phragmites Australis — a Helophytic Grass — Can Establish Successful Partnership with Phenol-Degrading Bacteria in a Floating Treatment Wetland. Saudi J. Biol. Sci. 2019, 26, 1179–1186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- George, A.; Dhayal Raj, A.; Albert Irudayaraj, A.; Josephine, R.L.; Venci, X.; John Sundaram, S.; Rajakrishnan, R.; Kuppusamy, P.; Kaviyarasu, K. Regeneration Study of MB in Recycling Runs over Nickel Vanadium Oxide by Solvent Extraction for Photocatalytic Performance for Wastewater Treatments. Environ. Res. 2022, 211, 112970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Najafinejad, M.S.; Mohammadi, P.; Mehdi Afsahi, M.; Sheibani, H. Biosynthesis of Au Nanoparticles Supported on Fe3O4@polyaniline as a Heterogeneous and Reusable Magnetic Nanocatalyst for Reduction of the Azo Dyes at Ambient Temperature. Mater. Sci. Eng. C 2019, 98, 19–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Najafinejad, M.S.; Mohammadi, P.; Mehdi Afsahi, M.; Sheibani, H. Green Synthesis of the Fe3O4@polythiophen-Ag Magnetic Nanocatalyst Using Grapefruit Peel Extract: Application of the Catalyst for Reduction of Organic Dyes in Water. J. Mol. Liq. 2018, 262, 248–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fenti, A.; Jin, Y.; Rhoades, A.J.H.; Dooley, G.P.; Iovino, P.; Salvestrini, S.; Musmarra, D.; Mahendra, S.; Peaslee, G.F.; Blotevogel, J. Performance Testing of Mesh Anodes for in Situ Electrochemical Oxidation of PFAS. Chem. Eng. J. Adv. 2022, 9, 100205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sayadi, M.H.; Chamanehpour, E.; Fahoul, N. Recent Advances and Future Outlook for Treatment of Pharmaceutical from Water: An Overview. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2023, 20, 3437–3454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Espinoza-Montero, P.J.; Vega-Verduga, C.; Alulema-Pullupaxi, P.; Fernández, L.; Paz, J.L. Technologies Employed in the Treatment of Water Contaminated with Glyphosate: A Review. Molecules 2020, 25, 5550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rayaroth, M.P.; Aravindakumar, C.T.; Shah, N.S.; Boczkaj, G. Advanced Oxidation Processes (AOPs) Based Wastewater Treatment - Unexpected Nitration Side Reactions - a Serious Environmental Issue: A Review. Chem. Eng. J. 2022, 430, 133002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Huitle, C.A.; Rodrigo, M.A.; Sirés, I.; Scialdone, O. A Critical Review on Latest Innovations and Future Challenges of Electrochemical Technology for the Abatement of Organics in Water. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2023, 328, 122430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salvestrini, S.; Fenti, A.; Chianese, S.; Iovino, P.; Musmarra, D. Electro-Oxidation of Humic Acids Using Platinum Electrodes: An Experimental Approach and Kinetic Modelling. Water 2020, 12, 2250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radjenovic, J.; Duinslaeger, N.; Avval, S.S.; Chaplin, B.P. Facing the Challenge of Poly- and Perfluoroalkyl Substances in Water: Is Electrochemical Oxidation the Answer? Environ. Sci. Technol. 2020, 54, 14815–14829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Y.; Lin, H.; Guo, Z.; Zhang, W.; Li, H.; Huang, W. Recent Developments and Advances in Boron-Doped Diamond Electrodes for Electrochemical Oxidation of Organic Pollutants. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2019, 212, 802–821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Comninellis, C. Electrocatalysis in the Electrochemical Conversion/Combustion of Organic Pollutants for Waste Water Treatment. Electrochim. Acta 1994, 39, 1857–1862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y. Recent Advances in the Electrochemical Oxidation Water Treatment: Spotlight on Byproduct Control. Front. Environ. Sci. Eng. 2020, 14, 85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwarzer-Fischer, E.; Günther, A.; Roszeitis, S.; Moritz, T. Combining Zirconia and Titanium Suboxides by Vat Photopolymerization. Materials (Basel). 2021, 14, 2394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, D.; Li, H.; Li, M.; Li, C.; Qian, L.; Zhou, B.; Yang, B. Boron-Doped Graphene Directly Grown on Boron-Doped Diamond for High-Voltage Aqueous Supercapacitors. ACS Appl. Energy Mater. 2019, 2, 1526–1536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Guo, M.; Shao, Y.; Yu, H.; Ni, K. Electrocatalytic Properties of a Novel β-PbO 2 /Halloysite Nanotube Composite Electrode. ACS Omega 2021, 6, 5436–5444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Periyasamy, S.; Muthuchamy, M. Electrochemical Oxidation of Paracetamol in Water by Graphite Anode: Effect of PH, Electrolyte Concentration and Current Density. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2018, 6, 7358–7367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pongpichayakul, N.; Themsirimongkon, S.; Maturost, S.; Wangkawong, K.; Fang, L.; Inceesungvorn, B.; Waenkaew, P.; Saipanya, S. Cerium Oxide-Modified Surfaces of Several Carbons as Supports for a Platinum-Based Anode Electrode for Methanol Electro-Oxidation. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2021, 46, 2905–2916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, H.; Bi, Y.; Liu, F.; Zhang, C.; Wei, N.; Fan, L.; Zhou, R. Removal of Ofloxacin from Wastewater by Chloride Electrolyte Electro-Oxidation: Analysis of the Role of Active Chlorine and Operating Costs. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 850, 157963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kevin, M. Tenny; Michael Keenaghan Ohms Law; Europena PMC, Ed. 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, L.; Lu, J.; Li, L.; Wang, Y.; Huang, Q. Effects of Chloride on Electrochemical Degradation of Perfluorooctanesulfonate by Magnéli Phase Ti4O7 and Boron Doped Diamond Anodes. Water Res. 2020, 170, 115254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Uwayezu, J.N.; Carabante, I.; Lejon, T.; van Hees, P.; Karlsson, P.; Hollman, P.; Kumpiene, J. Electrochemical Degradation of Per- and Poly-Fluoroalkyl Substances Using Boron-Doped Diamond Electrodes. J. Environ. Manage. 2021, 290, 112573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pierpaoli, M.; Szopińska, M.; Wilk, B.K.; Sobaszek, M.; Łuczkiewicz, A.; Bogdanowicz, R.; Fudala-Książek, S. Electrochemical Oxidation of PFOA and PFOS in Landfill Leachates at Low and Highly Boron-Doped Diamond Electrodes. J. Hazard. Mater. 2021, 403, 123606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, H.; Xiao, R.; Xie, R.; Yang, L.; Tang, C.; Wang, R.; Chen, J.; Lv, S.; Huang, Q. Defect Engineering on a Ti 4 O 7 Electrode by Ce 3+ Doping for the Efficient Electrooxidation of Perfluorooctanesulfonate. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2021, 55, 2597–2607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, D.; Wang, K.; Niu, J.; Chu, C.; Weon, S.; Zhu, Q.; Lu, J.; Stavitski, E.; Kim, J.-H. Amorphous Pd-Loaded Ti 4 O 7 Electrode for Direct Anodic Destruction of Perfluorooctanoic Acid. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2020, 54, 10954–10963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanni, I.; Karimi Estahbanati, M.R.; Carabin, A.; Drogui, P. Coupling Electrocoagulation with Electro-Oxidation for COD and Phosphorus Removal from Industrial Container Wash Water. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2022, 282, 119992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ken, D.S.; Sinha, A. Dimensionally Stable Anode (Ti/RuO2) Mediated Electro-Oxidation and Multi-Response Optimization Study for Remediation of Coke-Oven Wastewater. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2021, 9, 105025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Li, Z.; Zhang, F.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, X.; Wang, J.; He, X. Comparison of Ti/Ti4O7, Ti/Ti4O7-PbO2-Ce, and Ti/Ti4O7 Nanotube Array Anodes for Electro-Oxidation of p-Nitrophenol and Real Wastewater. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2021, 266, 118600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lebik-Elhadi, H.; Frontistis, Z.; Ait-Amar, H.; Amrani, S.; Mantzavinos, D. Electrochemical Oxidation of Pesticide Thiamethoxam on Boron Doped Diamond Anode: Role of Operating Parameters and Matrix Effect. Process Saf. Environ. Prot. 2018, 116, 535–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Huitle, C.A.; Rodrigo, M.A.; Sirés, I.; Scialdone, O. Single and Coupled Electrochemical Processes and Reactors for the Abatement of Organic Water Pollutants: A Critical Review. Chem. Rev. 2015, 115, 13362–13407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, Y.; Zhao, D.; Lin, H.; Huang, H.; Li, H.; Guo, Z. Design of Diamond Anodes in Electrochemical Degradation of Organic Pollutants. Curr. Opin. Electrochem. 2022, 32, 100878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urtiaga, A.; Fernández-González, C.; Gómez-Lavín, S.; Ortiz, I. Kinetics of the Electrochemical Mineralization of Perfluorooctanoic Acid on Ultrananocrystalline Boron Doped Conductive Diamond Electrodes. Chemosphere 2015, 129, 20–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Tang, J.; Peng, C.; Jin, M. Degradation of Perfluorinated Compounds in Wastewater Treatment Plant Effluents by Electrochemical Oxidation with Nano-ZnO Coated Electrodes. J. Mol. Liq. 2016, 221, 1145–1150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barisci, S.; Suri, R. Electrooxidation of Short and Long Chain Perfluorocarboxylic Acids Using Boron Doped Diamond Electrodes. Chemosphere 2020, 243, 125349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sukeesan, S.; Boontanon, N.; Boontanon, S.K. Improved Electrical Driving Current of Electrochemical Treatment of Per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances (PFAS) in Water Using Boron-Doped Diamond Anode. Environ. Technol. Innov. 2021, 23, 101655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuo, Q.; Xiang, Q.; Yi, H.; Zhang, Z.; Yang, B.; Cui, K.; Bing, X.; Xu, Z.; Liang, X.; Guo, Q.; et al. Electrochemical Oxidation of PFOA in Aqueous Solution Using Highly Hydrophobic Modified PbO 2 Electrodes. J. Electroanal. Chem. 2017, 801, 235–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Y.; Xiao, M.; Li, Z.; Luo, Y.; Zhang, K.; Du, X.; Zhang, T.; Wang, Z.; Liang, H. Degradation of Antibiotics, Organic Matters and Ammonia during Secondary Wastewater Treatment Using Boron-Doped Diamond Electro-Oxidation Combined with Ceramic Ultrafiltration. Chemosphere 2022, 286, 131680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Özcan, A.; Şahin, Y.; Koparal, A.S.; Oturan, M.A. Propham Mineralization in Aqueous Medium by Anodic Oxidation Using Boron-Doped Diamond Anode: Influence of Experimental Parameters on Degradation Kinetics and Mineralization Efficiency. Water Res. 2008, 42, 2889–2898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sirés, I.; Brillas, E.; Oturan, M.A.; Rodrigo, M.A.; Panizza, M. Electrochemical Advanced Oxidation Processes: Today and Tomorrow. A Review. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2014, 21, 8336–8367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Electrochemistry for the Environment; Comninellis, C. , Chen, G., Eds.; Springer New York: New York, NY, 2010; ISBN 978-0-387-36922-8. [Google Scholar]

- Flox, C.; Cabot, P.L.; Centellas, F.; Garrido, J.A.; Rodríguez, R.M.; Arias, C.; Brillas, E. Electrochemical Combustion of Herbicide Mecoprop in Aqueous Medium Using a Flow Reactor with a Boron-Doped Diamond Anode. Chemosphere 2006, 64, 892–902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Panizza, M.; Cerisola, G. Removal of Colour and COD from Wastewater Containing Acid Blue 22 by Electrochemical Oxidation. J. Hazard. Mater. 2008, 153, 83–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anglada, A.; Urtiaga, A.; Ortiz, I. Contributions of Electrochemical Oxidation to Waste-Water Treatment: Fundamentals and Review of Applications. J. Chem. Technol. Biotechnol. 2009, 84, 1747–1755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biswas, B.; Goel, S. Electrocoagulation and Electrooxidation Technologies for Pesticide Removal from Water or Wastewater: A Review. Chemosphere 2022, 302, 134709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhuo, Q.; Han, J.; Niu, J.; Zhang, J. Degradation of a Persistent Organic Pollutant Perfluorooctane Sulphonate with Ti/SnO2–Sb2O5/PbO2-PTFE Anode. Emerg. Contam. 2020, 6, 44–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Q.; Liu, L.; Cui, W.; Li, R.; Song, T.; Cui, Z. Electrochemical Degradation of Perfluorooctanoic Acid (PFOA) by Yb-Doped Ti/SnO 2 –Sb/PbO 2 Anodes and Determination of the Optimal Conditions. RSC Adv. 2015, 5, 84856–84864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danial, R.; Sobri, S.; Abdullah, L.C.; Mobarekeh, M.N. FTIR, CHNS and XRD Analyses Define Mechanism of Glyphosate Herbicide Removal by Electrocoagulation. Chemosphere 2019, 233, 559–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behloul, M.; Grib, H.; Drouiche, N.; Abdi, N.; Lounici, H.; Mameri, N. Removal of Malathion Pesticide from Polluted Solutions by Electrocoagulation: Modeling of Experimental Results Using Response Surface Methodology. Sep. Sci. Technol. 2013, 48, 664–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, H.; Niu, J.; Xu, J.; Huang, H.; Li, D.; Yue, Z.; Feng, C. Highly Efficient and Mild Electrochemical Mineralization of Long-Chain Perfluorocarboxylic Acids (C9–C10) by Ti/SnO 2 –Sb–Ce, Ti/SnO 2 –Sb/Ce–PbO 2, and Ti/BDD Electrodes. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2013, 47, 13039–13046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kamaraj, R.; Davidson, D.J.; Sozhan, G.; Vasudevan, S. Adsorption of 2,4-Dichlorophenoxyacetic Acid (2,4-D) from Water by in Situ Generated Metal Hydroxides Using Sacrificial Anodes. J. Taiwan Inst. Chem. Eng. 2014, 45, 2943–2949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walsh, F.C.; Ponce de León, C. Progress in Electrochemical Flow Reactors for Laboratory and Pilot Scale Processing. Electrochim. Acta 2018, 280, 121–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cornejo, O.M.; Murrieta, M.F.; Castañeda, L.F.; Nava, J.L. Electrochemical Reactors Equipped with BDD Electrodes: Geometrical Aspects and Applications in Water Treatment. Curr. Opin. Solid State Mater. Sci. 2021, 25, 100935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magro, C.; Mateus, E.P.; Paz-Garcia, J.M.; Ribeiro, A.B. Emerging Organic Contaminants in Wastewater: Understanding Electrochemical Reactors for Triclosan and Its by-Products Degradation. Chemosphere 2020, 247, 125758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hao, Y.; Ma, H.; Proietto, F.; Galia, A.; Scialdone, O. Electrochemical Treatment of Wastewater Contaminated by Organics and Containing Chlorides: Effect of Operative Parameters on the Abatement of Organics and the Generation of Chlorinated by-Products. Electrochim. Acta 2022, 402, 139480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Periyasamy, S.; Lin, X.; Ganiyu, S.O.; Kamaraj, S.-K.; Thiam, A.; Liu, D. Insight into BDD Electrochemical Oxidation of Florfenicol in Water: Kinetics, Reaction Mechanism, and Toxicity. Chemosphere 2022, 288, 132433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calzadilla, W.; Espinoza, L.C.; Diaz-Cruz, M.S.; Sunyer, A.; Aranda, M.; Peña-Farfal, C.; Salazar, R. Simultaneous Degradation of 30 Pharmaceuticals by Anodic Oxidation: Main Intermediaries and by-Products. Chemosphere 2021, 269, 128753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- H. Vogt The Quantities Affecting the Bubble Coverage of Gas-Evolving Electrodes. Electrochim. Acta 2017, 495–499.

- Andrea Angulo; Peter van der Linde; Han Gardeniers; Miguel Modestino; David Fernández Rivas Influence of Bubbles on the Energy Conversion Efficiency of Electrochemical Reactors. Joule 2020, 555–579.

- Najafpoor, A.A.; Davoudi, M.; Rahmanpour Salmani, E. Decolorization of Synthetic Textile Wastewater Using Electrochemical Cell Divided by Cellulosic Separator. J. Environ. Heal. Sci. Eng. 2017, 15, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Electro-Oxidation Kinetics of Cerium(III) in Nitric Acid Using Divided Electrochemical Cell for Application in the Mediated Electrochemical Oxidation of Phenol. Bull. Korean Chem. Soc. 2007, 28, 1329–1334. [CrossRef]

- Mora-Gomez, J.; Ortega, E.; Mestre, S.; Pérez-Herranz, V.; García-Gabaldón, M. Electrochemical Degradation of Norfloxacin Using BDD and New Sb-Doped SnO2 Ceramic Anodes in an Electrochemical Reactor in the Presence and Absence of a Cation-Exchange Membrane. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2019, 208, 68–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandoval, M.A.; Calzadilla, W.; Salazar, R. Influence of Reactor Design on the Electrochemical Oxidation and Disinfection of Wastewaters Using Boron-Doped Diamond Electrodes. Curr. Opin. Electrochem. 2022, 33, 100939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirata, H.; Dobrokhotov, O.; Sokabe, M. Coordination between Cell Motility and Cell Cycle Progression in Keratinocyte Sheets via Cell-Cell Adhesion and Rac1. iScience 2020, 23, 101729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trellu, C.; Chaplin, B.P.; Coetsier, C.; Esmilaire, R.; Cerneaux, S.; Causserand, C.; Cretin, M. Electro-Oxidation of Organic Pollutants by Reactive Electrochemical Membranes. Chemosphere 2018, 208, 159–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicholls, T.P.; Schotten, C.; Willans, C.E. Electrochemistry in Continuous Systems. Curr. Opin. Green Sustain. Chem. 2020, 26, 100355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cornejo, O.M.; Murrieta, M.F.; Castañeda, L.F.; Nava, J.L. Characterization of the Reaction Environment in Flow Reactors Fitted with BDD Electrodes for Use in Electrochemical Advanced Oxidation Processes: A Critical Review. Electrochim. Acta 2020, 331, 135373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivera, F.F.; Pérez, T.; Castañeda, L.F.; Nava, J.L. Mathematical Modeling and Simulation of Electrochemical Reactors: A Critical Review. Chem. Eng. Sci. 2021, 239, 116622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nava, J.L.; Oropeza, M.T.; Ponce de León, C.; González-García, J.; Frías-Ferrer, A.J. Determination of the Effective Thickness of a Porous Electrode in a Flow-through Reactor; Effect of the Specific Surface Area of Stainless Steel Fibres, Used as a Porous Cathode, during the Deposition of Ag(I) Ions. Hydrometallurgy 2008, 91, 98–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Chen, M.; Wang, C.; Meng, X.; Zhang, W.; Chen, Z.; Crittenden, J. Electrochemical Degradation of Methylisothiazolinone by Using Ti/SnO2-Sb2O3/α, β-PbO2 Electrode: Kinetics, Energy Efficiency, Oxidation Mechanism and Degradation Pathway. Chem. Eng. J. 2019, 374, 626–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Zhao, X.; Wang, C.; Pan, S. Novel Multistage Electrochemical Flow-through Mode (EFTM) with Porous Electrodes for Reclaimed Wastewater Treatment in Pipes. ACS ES&T Water 2021, 1, 653–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lang, Z.; Zhou, M.; Zhang, Q.; Yin, X.; Li, Y. Comprehensive Treatment of Marine Aquaculture Wastewater by a Cost-Effective Flow-through Electro-Oxidation Process. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 722, 137812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Panizza, M.; Cerisola, G. Direct And Mediated Anodic Oxidation of Organic Pollutants. Chem. Rev. 2009, 109, 6541–6569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghanbari, F.; Wang, Q.; Hassani, A.; Wacławek, S.; Rodríguez-Chueca, J.; Lin, K.-Y.A. Electrochemical Activation of Peroxides for Treatment of Contaminated Water with Landfill Leachate: Efficacy, Toxicity and Biodegradability Evaluation. Chemosphere 2021, 279, 130610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martínez-Huitle, C.A.; Panizza, M. Electrochemical Oxidation of Organic Pollutants for Wastewater Treatment. Curr. Opin. Electrochem. 2018, 11, 62–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nidheesh, P.V.; Kumar, A.; Syam Babu, D.; Scaria, J.; Suresh Kumar, M. Treatment of Mixed Industrial Wastewater by Electrocoagulation and Indirect Electrochemical Oxidation. Chemosphere 2020, 251, 126437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Groenen Serrano, K. Indirect Electrochemical Oxidation Using Hydroxyl Radical, Active Chlorine, and Peroxodisulfate. In Electrochemical Water and Wastewater Treatment; Elsevier, 2018; pp. 133–164.

- Cai, J.; Zhou, M.; Liu, Y.; Savall, A.; Groenen Serrano, K. Indirect Electrochemical Oxidation of 2,4-Dichlorophenoxyacetic Acid Using Electrochemically-Generated Persulfate. Chemosphere 2018, 204, 163–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, S.; Tu, Y.; Chen, J.; Shao, G.; Zhou, Z.; Ren, Z. Persulfate Enhanced Electrochemical Oxidation of Phenol with CuFe2O4/ACF (Activated Carbon Fibers) Cathode. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2021, 279, 119727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, H.; Yan, L.; Ma, J.; Jiang, J.; Cai, G.; Zhang, W.; Zhang, Z.; Zhang, J.; Yang, T. Nonradical Oxidation from Electrochemical Activation of Peroxydisulfate at Ti/Pt Anode: Efficiency, Mechanism and Influencing Factors. Water Res. 2017, 116, 182–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Almasi, A.; Esmaeilpoor, R.; Hoseini, H.; Abtin, V.; Mohammadi, M. Photocatalytic Degradation of Cephalexin by UV Activated Persulfate and Fenton in Synthetic Wastewater: Optimization, Kinetic Study, Reaction Pathway and Intermediate Products. J. Environ. Heal. Sci. Eng. 2020, 18, 1359–1373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mazivila, S.J.; Ricardo, I.A.; Leitão, J.M.M.; Esteves da Silva, J.C.G. A Review on Advanced Oxidation Processes: From Classical to New Perspectives Coupled to Two- and Multi-Way Calibration Strategies to Monitor Degradation of Contaminants in Environmental Samples. Trends Environ. Anal. Chem. 2019, 24, e00072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganiyu, S.O.; Sable, S.; Gamal El-Din, M. Advanced Oxidation Processes for the Degradation of Dissolved Organics in Produced Water: A Review of Process Performance, Degradation Kinetics and Pathway. Chem. Eng. J. 2022, 429, 132492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilk, B.K.; Szopińska, M.; Luczkiewicz, A.; Sobaszek, M.; Siedlecka, E.; Fudala-Ksiazek, S. Kinetics of the Organic Compounds and Ammonium Nitrogen Electrochemical Oxidation in Landfill Leachates at Boron-Doped Diamond Anodes. Materials (Basel). 2021, 14, 4971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, S.; Bejan, D.; McDowell, M.S.; Bunce, N.J. Mixed First and Zero Order Kinetics in the Electrooxidation of Sulfamethoxazole at a Boron-Doped Diamond (BDD) Anode. J. Appl. Electrochem. 2008, 38, 151–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, Y.H.; Feng, Y.J.; Li, X.Y. Kinetics and Efficiency Analysis of Electrochemical Oxidation of Phenol: Influence of Anode Materials and Operational Conditions. Chem. Eng. Technol. 2011, 34, 265–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganiyu, S.O.; Oturan, N.; Raffy, S.; Cretin, M.; Esmilaire, R.; van Hullebusch, E.; Esposito, G.; Oturan, M.A. Sub-Stoichiometric Titanium Oxide (Ti4O7) as a Suitable Ceramic Anode for Electrooxidation of Organic Pollutants: A Case Study of Kinetics, Mineralization and Toxicity Assessment of Amoxicillin. Water Res. 2016, 106, 171–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oturan, M.A.; Aaron, J.-J. Advanced Oxidation Processes in Water/Wastewater Treatment: Principles and Applications. A Review. Crit. Rev. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2014, 44, 2577–2641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Öztürk, H.; Barışçı, S.; Turkay, O. Paracetamol Degradation and Kinetics by Advanced Oxidation Processes (AOPs): Electro-Peroxone, Ozonation, Goethite Catalyzed Electro-Fenton and Electro-Oxidation. Environ. Eng. Res. 2020, 26, 180332–0. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hai, H.; Xing, X.; Li, S.; Xia, S.; Xia, J. Electrochemical Oxidation of Sulfamethoxazole in BDD Anode System: Degradation Kinetics, Mechanisms and Toxicity Evaluation. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 738, 139909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olvera-Vargas, H.; Oturan, N.; Aravindakumar, C.T.; Paul, M.M.S.; Sharma, V.K.; Oturan, M.A. Electro-Oxidation of the Dye Azure B: Kinetics, Mechanism, and by-Products. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2014, 21, 8379–8386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brillas, E.; Garcia-Segura, S.; Skoumal, M.; Arias, C. Electrochemical Incineration of Diclofenac in Neutral Aqueous Medium by Anodic Oxidation Using Pt and Boron-Doped Diamond Anodes. Chemosphere 2010, 79, 605–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, P.; Kushwaha, J.P.; Sangal, V.K. Evaluation and Disposability Study of Actual Textile Wastewater Treatment by Electro-Oxidation Method Using Ti/RuO2 Anode. Process Saf. Environ. Prot. 2017, 111, 13–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolton, J.R.; Bircher, K.G.; Tumas, W.; Tolman, C.A. Figures-of-Merit for the Technical Development and Application of Advanced Oxidation Technologies for Both Electric- and Solar-Driven Systems (IUPAC Technical Report). Pure Appl. Chem. 2001, 73, 627–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pica, N.E.; Funkhouser, J.; Yin, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Ceres, D.M.; Tong, T.; Blotevogel, J. Electrochemical Oxidation of Hexafluoropropylene Oxide Dimer Acid (GenX): Mechanistic Insights and Efficient Treatment Train with Nanofiltration. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2019, 53, 12602–12609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Singh, S.; Srivastava, V.C. Electro-Oxidation of Nitrophenol by Ruthenium Oxide Coated Titanium Electrode: Parametric, Kinetic and Mechanistic Study. Chem. Eng. J. 2015, 263, 135–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cañizares, P.; Paz, R.; Sáez, C.; Rodrigo, M.A. Costs of the Electrochemical Oxidation of Wastewaters: A Comparison with Ozonation and Fenton Oxidation Processes. J. Environ. Manage. 2009, 90, 410–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chatzisymeon, E.; Xekoukoulotakis, N.P.; Coz, A.; Kalogerakis, N.; Mantzavinos, D. Electrochemical Treatment of Textile Dyes and Dyehouse Effluents. J. Hazard. Mater. 2006, 137, 998–1007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subbaramaiah, V.; Srivastava, V.C.; Mall, I.D. Catalytic Wet Peroxidation of Pyridine Bearing Wastewater by Cerium Supported SBA-15. J. Hazard. Mater. 2013, 248–249, 355–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaur, R.; Kushwaha, J.P.; Singh, N. Electro-Oxidation of Ofloxacin Antibiotic by Dimensionally Stable Ti/RuO2 Anode: Evaluation and Mechanistic Approach. Chemosphere 2018, 193, 685–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sales Solano, A.M.; Costa de Araújo, C.K.; Vieira de Melo, J.; Peralta-Hernandez, J.M.; Ribeiro da Silva, D.; Martínez-Huitle, C.A. Decontamination of Real Textile Industrial Effluent by Strong Oxidant Species Electrogenerated on Diamond Electrode: Viability and Disadvantages of This Electrochemical Technology. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2013, 130–131, 112–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsantaki, E.; Velegraki, T.; Katsaounis, A.; Mantzavinos, D. Anodic Oxidation of Textile Dyehouse Effluents on Boron-Doped Diamond Electrode. J. Hazard. Mater. 2012, 207–208, 91–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, H.; Yoshida, G.; Andriamanohiarisoamanana, F.J.; Ihara, I. Electro-Oxidation Combined with Electro-Fenton for Decolorization of Caramel Colorant Aqueous Solution Using BDD Electrodes. J. Water Process Eng. 2022, 47, 102672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antonelli, R.; Malpass, G.R.P.; Carlos da Silva, M.G.; Vieira, M.G.A. Ofloxacin Degradation in Chloride-Containing Medium by Photo-Assisted Sonoelectrochemical Process Using a Mixed Metal Oxide Anode. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2022, 10, 107174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mousset, E.; Dionysiou, D.D. Photoelectrochemical Reactors for Treatment of Water and Wastewater: A Review. Environ. Chem. Lett. 2020, 18, 1301–1318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Li, Y.; Xiong, Z.; Yao, G.; Lai, B. The Electrochemical Advanced Oxidation Processes Coupling of Oxidants for Organic Pollutants Degradation: A Mini-Review. Chinese Chem. Lett. 2019, 30, 2139–2146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alulema-Pullupaxi, P.; Espinoza-Montero, P.J.; Sigcha-Pallo, C.; Vargas, R.; Fernández, L.; Peralta-Hernández, J.M.; Paz, J.L. Fundamentals and Applications of Photoelectrocatalysis as an Efficient Process to Remove Pollutants from Water: A Review. Chemosphere 2021, 281, 130821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pirsaheb, M.; Hoseini, H.; Abtin, V. Photoelectrocatalytic Degradation of Humic Acid and Disinfection over Ni TiO2-Ni/ AC-PTFE Electrode under Natural Sunlight Irradiation: Modeling, Optimization and Reaction Pathway. J. Taiwan Inst. Chem. Eng. 2021, 118, 204–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bessegato, G.G.; Guaraldo, T.T.; de Brito, J.F.; Brugnera, M.F.; Zanoni, M.V.B. Achievements and Trends in Photoelectrocatalysis: From Environmental to Energy Applications. Electrocatalysis 2015, 6, 415–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alulema-Pullupaxi, P.; Fernández, L.; Debut, A.; Santacruz, C.P.; Villacis, W.; Fierro, C.; Espinoza-Montero, P.J. Photoelectrocatalytic Degradation of Glyphosate on Titanium Dioxide Synthesized by Sol-Gel/Spin-Coating on Boron Doped Diamond (TiO2/BDD) as a Photoanode. Chemosphere 2021, 278, 130488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandis, P.K.; Kalogirou, C.; Kanellou, E.; Vaitsis, C.; Savvidou, M.G.; Sourkouni, G.; Zorpas, A.A.; Argirusis, C. Key Points of Advanced Oxidation Processes (AOPs) for Wastewater, Organic Pollutants and Pharmaceutical Waste Treatment: A Mini Review. ChemEngineering 2022, 6, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peleyeju, M.G.; Arotiba, O.A. Recent Trend in Visible-Light Photoelectrocatalytic Systems for Degradation of Organic Contaminants in Water/Wastewater. Environ. Sci. Water Res. Technol. 2018, 4, 1389–1411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asahi, R.; Morikawa, T.; Irie, H.; Ohwaki, T. Nitrogen-Doped Titanium Dioxide as Visible-Light-Sensitive Photocatalyst: Designs, Developments, and Prospects. Chem. Rev. 2014, 114, 9824–9852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zarei, E.; Ojani, R. Fundamentals and Some Applications of Photoelectrocatalysis and Effective Factors on Its Efficiency: A Review. J. Solid State Electrochem. 2017, 21, 305–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Li, C.; Zhang, T.; Xu, Z.; Li, Y.; Li, B.; Tian, S. UV Facilitated Synergistic Effects of Polymetals in Ore Catalyst on Peroxymonosulfate Activation: Implication for the Degradation of Bisphenol S. Chem. Eng. J. 2022, 431, 133989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, F.; Li, M.; Li, W.; Feng, C.; Jin, Y.; Guo, X.; Cui, J. Degradation of Phenol by a Combined Independent Photocatalytic and Electrochemical Process. Chem. Eng. J. 2011, 175, 349–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montenegro-Ayo, R.; Morales-Gomero, J.C.; Alarcon, H.; Cotillas, S.; Westerhoff, P.; Garcia-Segura, S. Scaling up Photoelectrocatalytic Reactors: A TiO2 Nanotube-Coated Disc Compound Reactor Effectively Degrades Acetaminophen. Water 2019, 11, 2522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, K.; Zhang, H.; Ma, Y.; Sun, T.; Jia, J. Nanostructured Polypyrrole Cathode Based Dual Rotating Disk Photo Fuel Cell for Textile Wastewater Purification and Electricity Generation. Electrochim. Acta 2019, 303, 329–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, H.; Zong, M.; Dong, F.; Yang, P.; Ke, G.; Liu, M.; Nie, X.; Ren, W.; Bian, L. Simultaneous Removal and Recovery of Uranium from Aqueous Solution Using TiO2 Photoelectrochemical Reduction Method. J. Radioanal. Nucl. Chem. 2017, 313, 59–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Domene, R.M.; Sánchez-Tovar, R.; Lucas-granados, B.; Muñoz-Portero, M.J.; García-Antón, J. Elimination of Pesticide Atrazine by Photoelectrocatalysis Using a Photoanode Based on WO3 Nanosheets. Chem. Eng. J. 2018, 350, 1114–1124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Gan, X.; Zhou, B.; Xiong, B.; Li, J.; Dong, C.; Bai, J.; Cai, W. Photoelectrocatalytic Degradation of Tetracycline by Highly Effective TiO2 Nanopore Arrays Electrode. J. Hazard. Mater. 2009, 171, 678–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, X.; Zhou, Y.; Zhang, G.; Liu, T.; Dong, W. In Situ Photoelectrochemical Activation of Sulfite by MoS2 Photoanode for Enhanced Removal of Ammonium Nitrogen from Wastewater. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2019, 244, 396–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subba Rao, A.N.; Venkatarangaiah, V.T. Preparation, Characterization, and Application of Ti/TiO2-NTs/Sb-SnO2 Electrode in Photo-Electrochemical Treatment of Industrial Effluents under Mild Conditions. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2018, 25, 11480–11492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, Y.-P.; Chen, H.; Huang, C.P. The Synergistic Effect of Photoelectrochemical (PEC) Reactions Exemplified by Concurrent Perfluorooctanoic Acid (PFOA) Degradation and Hydrogen Generation over Carbon and Nitrogen Codoped TiO 2 Nanotube Arrays (C-N-TNTAs) Photoelectrode. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2017, 209, 437–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.; Maimaiti, H.; Xu, B.; Feng, L.; Bao, J.; Zhao, X. Photoelectrocatalytic Degradation of Wastewater and Simultaneous Hydrogen Production on Copper Nanorod-Supported Coal-Based N-Carbon Dot Composite Nanocatalysts. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2022, 585, 152701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Electrode (Anode) | Pollutants | Different current densities | Optimum current density | Removal efficiency (%) |

Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Magneli-phase titanium suboxides TinO2n-1 | PFOS | 30, 40, 50 mA/cm2 | 40 mA/cm2 | Over 99% | [10] |

| BDD | PFOA | 25,75mA/cm2 | 75 mA/cm2 | 79% | [29] |

| BDD | PFOA | 50, 100 and 200 A/m2 | 100 A/m2 | 84.1% | [38] |

| Nano-ZnO coated electrodes | perfluorinated compounds PFCs |

5, 10, 15, 20 and 25 mA/cm2 | 20 mA/cm2 | 66% | [39] |

| BDD | PFOA | 2.5, 6, 12, 25 mA cm−2 | 25 mA/cm2 | more than 90% | [40] |

| Si/BDD | PFAS | 1.8, 20, 27 and 40 mA/cm2 | 1.8 mA/cm2 | 76% - 83% | [41] |

| modified PbO2 |

PFOA | 10, 20, 30 mA/cm2 | 30 mA/cm2 | 91.3% | [42] |

| Material | OEP (VSHE) | |

|---|---|---|

| Active anodes | graphite | 1.7 |

| IrO2 | 1.5 | |

| RuO2 | 1.5 | |

| Pt | 1.6 | |

| Non-Active anodes | BDD | 2.3 |

| PbO2 | 1.9 | |

| SnO2 | 1.9 |

| Type of pollutants treated | Electrical energy consumed (kWh m−3) |

Cost of electrical energy (€ m−3) |

Cost of electrodes (€ m−3) |

Total operating cost (€ m−3) |

Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| p-nitrophenol | 96 | 6.7 | 220 | 226.7 | [101] |

| Eriochrome Black T | / | / | / | 52 | [102] |

| Textile effluent | 5.6 | 0.56 | / | 0.56 | [103] |

| pyridine | / | 0.038 | / | 248 | [104] |

| Butirric acid | / | / | / | 12 | [101] |

| Pharmaceuticals wastewater | 0.542 | 0.033 | 1.99 | 2.02 | [105] |

| Textile effluent | 43.82 | 7.22 | / | 7.22 | [106] |

| Textyle dyehouse | 1.93 | 0.13 | / | 0.13 | [107] |

| PFOS | 4.0 | 0.45 | / | 0.45 | [10] |

| Semiconductor Materials Applied as photoanode |

Supporting Electrolyte |

Light Source | Contaminant | Degradation Efficiency (%) and/or (Process Time(h)) |

Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Thin layer of the TiO2 slurry onto the surface of two PVC plates (16 cm ×6 cm) | [NaCl] = 0.3 g/L | power of UV lamp was 8 W | for 40% phenol removal and TOC0 = 38.30 mg/L | ∼0.35 (h) | [121] |

| TiO2NTs/Ti | 0.02M Na2SO4 | 14 UV lamp (275 nm) | Acetaminophen, 10 mg/L | Act > 95%, (5 h) |

[122] |

| TiO2NTs/Ti | --------- pH=3 |

11 W Hg lamp (254nm) | Real textile wastewater COD, 108 mg/L |

COD—74.1%, (4 h) |

[123] |

| TiO2/FTO Nanorods |

0.1 M NaCl, | 300W Xe lamp (AM 1.5 G filter) | U(VI), 0.5 mM | >99% (12 h) |

[124] |

| WO3/Ti Nanosheets |

0.1 M H2SO4 | 1000 W Xe lamp (360 nm), | Atrazine 20 mg/L | Atr—100% (3 h), TOC—72% (22h) |

[125] |

| TiO2/FTO NPs Nano porous |

0.02 M Na2SO4 | 4W UV lamp (254 nm) | Tetracycline, 10 mg/L |

80% (3 h) |

[126] |

| MoS2/ITO Nanosheets |

0.1 M Na2SO3 | 300WXe lamp (> 420 nm), | Ammonia nitrogen, 20 mg/L Bovine Serum Albumine, 10 mg/L |

AN—80% (6 h) BSA—70% (4 h) |

[127] |

| TiO2NTs/Sb-SNO2/Ti | ------------- | UV light (365 nm), | Textile industrial wastewater (TWW-COD = 237 mg/L),. Wastewater (CWW-COD = 686 mg/L) |

TWW-COD—58%, CWW-COD—54% (5 h) |

[128] |

| N-C-TNTAs/Ti | pH = 4 | 100 W Hg lamp, | Perfluorooctanoic acid, 40 mg/L |

56.1% (3 h) |

[129] |

| N-CDs/Cu NRs | 0.05M Na2SO4 | Hg lamp (250 W) | Cotton pulp black liquor | 94.33% (1h) |

[130] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).