Introduction

Drug-induced liver injury (DILI) is the most common cause of acute liver failure1. The diagnosis requires presence of a precipitator drug, latency of symptoms, resolution of liver injury once the offending drug is discontinued, and exclusion of other etiologies of liver injury2,3.

Ocrelizumab is a recombinant human anti-CD20 monoclonal antibody approved by the FDA in 2017 for treatment of primary progressive multiple sclerosis in adults <55 years old4. The double-blinded, multicenter, placebo-controlled ORATORIO trial showed slowed disease progression for up to 6.5 years5. However, ocrelizumab has been associated with development of adverse effects in patients >55 years old with inactive disease. Standard administration consists of two loading intravenous infusions of 300 mg two weeks apart, followed by 600 mg every six months thereafter6. Seven percent of patients treated with ocrelizumab developed adverse effects including infections, infusion-related reactions, oropharyngeal pain, and flushing7. To date, one hepatic adverse event has been reported: a fulminant echovirus 25-associated hepatitis in a patient found to be hepatitis B-immune through exposure8. Consequently, ocrelizumab is contraindicated for patients with active hepatitis B9,10. In our case, the patient presented with negative hepatitis B surface antigens and antibodies.

Here, we report a patient with an idiosyncratic, hepatocellular DILI after two doses of ocrelizumab for treatment of multiple sclerosis, proven by improvement with discontinuation of drug.

Case Report

A 51-year-old female with a past medical history of multiple sclerosis (MS), limb-girdle muscular dystrophy, psoriatic arthritis, hypertension, hypothyroidism presented to our tertiary care center with a 4-day history of jaundice and icterus. She endorsed associated symptoms of fatigue, nausea, vomiting, and dark urine.

She had recently been started on ocrelizumab for management of MS, with two loading infusions given 29 and 16 days prior to symptom onset. She denied use of new prescriptions, over-the-counter medications, health supplements, and recreational substances. She admitted one alcoholic drink 1-2 times weekly. There was no personal or family history of liver disease. Physical exam was notable for gross jaundice, but no asterixis, altered mental status, nor other liver-associated findings. Labs at baseline, obtained approximately 10 months prior to hospitalization, revealed AST, ALT, and platelet counts all WNL.

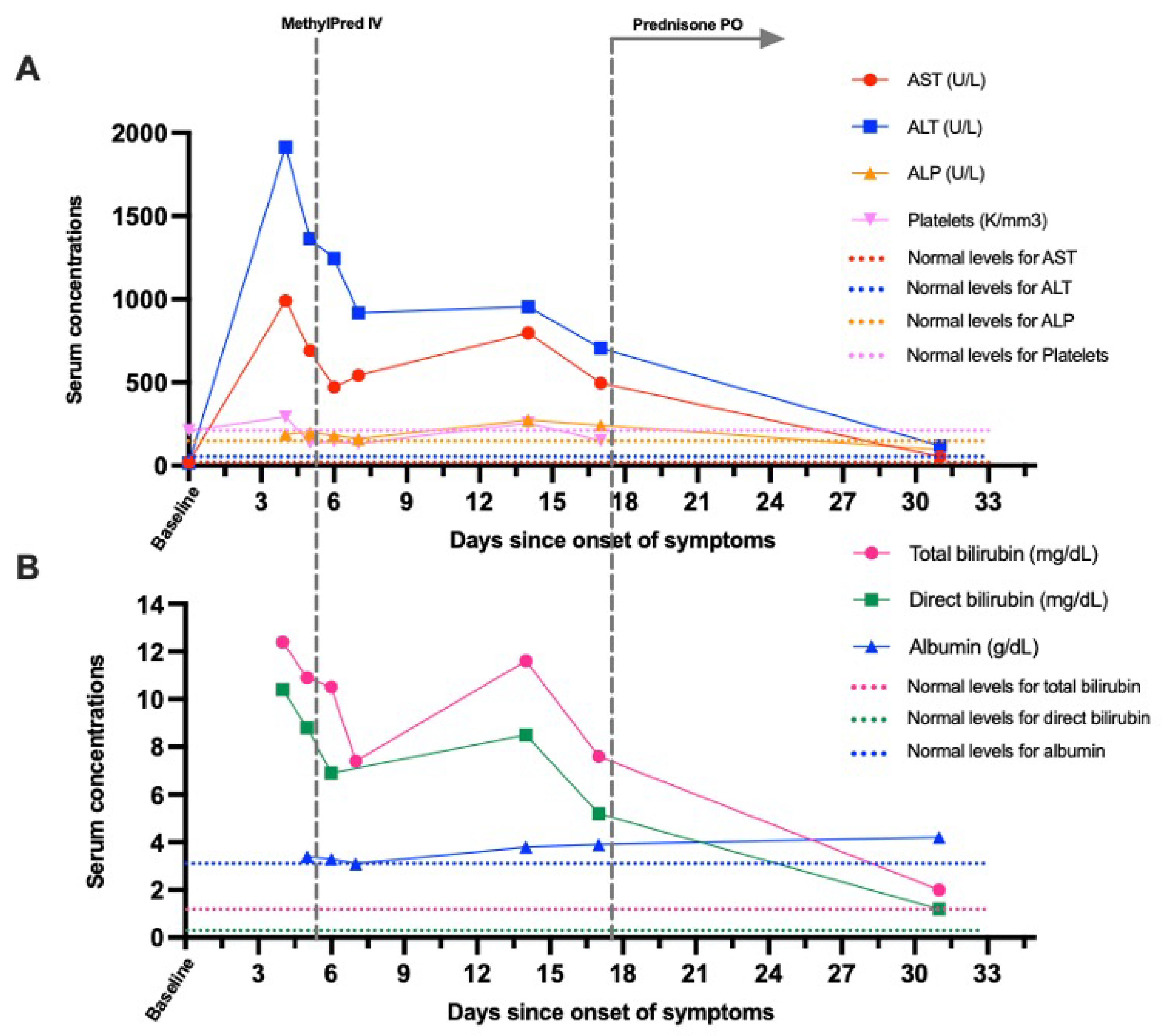

Admission labs revealed severe hepatocellular liver injury with AST 990 U/L, ALT 1914 U/L, GGT 437 U/L, ALP 188 U/L (

Figure 1A), direct 10.4 mg/dL and total bilirubin 12.4 mg/dL (

Figure 1B). Twenty-seven days later, liver enzymes were nearly normal with AST 52 U/L, ALT 119 U/L, ALP 96 U/L, total bilirubin 2 mg/dL. PT was elevated at 14 seconds when obtained on day 4 and 14, and resolved to WNL on day 17. INR remained WNL throughout. Platelet count on admission was WNL at 293

K/mm3 (

Figure 1A). However, when labs were obtained 5 times between days 5 and 17, the serum platelet count transiently dipped below normal range to 132-149 K/mm

3.

On the third day of hospitalization, n-acetylcysteine therapy was initiated. Immediately, she developed a moderate allergic reaction with hives, flushing, moderate difficulty swallowing, and tachycardia. Therapy was discontinued, and the patient received one dose each of diphenhydramine, famotidine, and 125 mg methylprednisolone. Before methylprednisolone administration, her liver chemistries had been down trending.

At 1-week post-discharge (day 14 on

Figure 1), our patient noticed worsening icterus and fatigue. Liver enzymes had also become mildly worse again (

Figure 1A, 1B) despite a general down-trending course. She was prescribed prednisone 40 mg daily for 1 week. Over 4 months after discharge, liver function had monotonically improved to AST 36 U/L, ALT 39 U/L, ALP 69 U/L, T bili 0.4 mg/dL, D bili <0.2 mg/dL, albumin 4.5 g/dL.

Labs were negative for hepatitis A antibody IgM, hepatitis B surface antibody, hepatitis B surface antigen, and hepatitis C antibody. Polymerase chain reactions for infectious etiologies of Epstein-Bar virus and cytomegalovirus were negative. Other laboratory findings including ammonia, ceruloplasmin, iron panel, ferritin, and lactic acid were WNL. Anti-smooth muscle antibody IgG, anti-mitochondrial antibody, and serum IgA were unremarkable. However, ANA titers and IgG (1142 mg/dL) were elevated. Right upper quadrant ultrasound with dopplers detected a hyperechoic, indeterminate right inferior lobe lesion, corresponding to a previously visualized segment lesion on CT, likely a hemangioma.

Discussion

DILI is classified as direct, indirect, or idiosyncratic, depending on pathophysiology2. Direct hepatotoxicity is dose-dependent, is reproducible in animal models, and typically occurs days after drug onset2,11,12. Idiosyncratic and indirect hepatotoxicities have neither of the first two characteristics of the direct classification, and typically display a variable (days to years) or delayed (months) timeline, respectively11,13. Idiosyncratic hepatotoxicity can further be divided into hepatocellular, cholestatic, or mixed categories, using an R ratio, calculated as the ratio of ALT and alkaline phosphatase divided by their respective ULNs. An R value >5 indicates hepatocellular, <2 indicates cholestatic, and 2<R<5 indicates mixed DILI14,15.

With discontinuation (dechallenge) of ocrelizumab, we expected gradual improvement of liver functions. Labs demonstrated a marked idiosyncratic hepatocellular liver injury pattern and R Factor of 30.48, with daily improvements since admission and near-complete resolution by day 31. Liver biopsy was not obtained from the patient at the time, due to swift improvements after dechallenge.

A critical component of diagnosing DILI was to rule out other differential etiologies that could cause hepatocellular predominant liver injury. We eliminated viral hepatitis, infectious etiologies, Wilson’s disease, hemochromatosis, and ischemic hepatopathy. Since ANA titers and IgG total were mildly abnormal (1142 mg/dL), drug-induced autoimmune liver disease (DIALD) should also be considered amongst potential differentials. DIALD can be divided into several subcategories including autoimmune hepatitis (AIH) with DILI

16, drug induced-AIH

17, and immune-mediated DILI

17. DIALD is still an under-reported and poorly defined category that would benefit from more attention and is frequently misdiagnosed as DILI. Both can be triggered by viruses and drugs

18,19. Castiella et al. reported 65% of DIALD cases relapsed after steroid withdrawal

16. However, our patient had continued to improve over a course of 4 months without steroid withdrawal relapse (

Figure 1). This lack of relapse indicates a greater likelihood of DILI presentation as opposed to DIALD.

Lastly, an abstract report was recently published by Ibrahim et al in October 2022, describing a similar instance of severe liver injury associated with ocrelizumab use20. The report resembles our case due to inception of symptoms occurring weeks after initial infusion, and it was briefly mentioned that the healthcare team administered intravenous and oral corticosteroids upon discharge from the hospital20. The report is nuanced due to greater degree of transaminitis and associated serum inflammatory markers20. A liver biopsy was additionally obtained20. We expect that our report supplements this abstract as well as provide insight into different degrees of severity that can manifest with ocrelizumab-induced liver injury.

Conclusion

The patient’s liver enzyme pattern, timeline of improvement, and recent inciting event with ocrelizumab are all suggestive of idiosyncratic drug-induced liver injury manifesting as acute hepatocellular hepatitis. This case report represents one of the first accounts of drug-induced liver damage from a recently FDA-approved CD20-monoclonal antibody, ocrelizumab. The goal of this report is to increase awareness of practitioners to rarer adverse effects caused by this medication that they may see in patients.

Financial Support or Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Data Availability

The manuscript data used to support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon request.

Consent

Verbal and written informed consents were obtained from the patient for the publication of this case report. Author can supply the written informed consent form upon request.

Abbreviations

DILI, Drug-Induced Liver Injury; AST, Aspartate Aminotransferase; ALT, Alanine Aminotransferase; GGT, Gamma Glutamyl Transferase; ALP, Alkaline Phosphatase; T Bili, Total Bilirubin; D Bili, Direct Bilirubin; HAV, Hepatitis A Virus; HBV, Hepatitis B Virus; HBc, Hepatitis B core; HCV, Hepatitis C Virus; HSV, Herpes Simplex Virus; EBV, Epstein Barr Virus; CMV, Cytomegalovirus; ULN, Upper limit of normal; PT prothrombin time; WNL within normal limit

References

- Reuben A, Koch DG, Lee WM. Drug-induced acute liver failure: results of a U.S. multicenter, prospective study. Hepatology. 2010;52:2065-2076.

- Hoofnagle JH, Björnsson ES. Drug-induced liver injury—types and phenotypes. New England Journal of Medicine. 2019;381(3):264-73.

- Björnsson, ES. Drug-induced liver injury: Hy's rule revisited. Clinical Pharmacology & Therapeutics. 2006;79:521-528.

- Calabresi PA. B-Cell Depletion - A Frontier In Monoclonal Antibodies For Multiple Sclerosis. New England Journal of Medicine. 2017 Jan 19;376(3):280-282.

- Montalban, X, Hauser, SL, Kappos, L. Ocrelizumab versus placebo in primary progressive multiple sclerosis. New England Journal of Medicine. 2017;376: 209–220.

- Ocrevus Medication Guides. US Food & Drug Administration. 2022, August 8. Retrieved December 31, 2022, directly downloaded from: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/scripts/cder/daf/index.cfm?event=medguide.page.

- Ng HS, Rosenbult CL, & Tremlett H. Safety profile of ocrelizumab for the treatment of multiple sclerosis: a systematic review. Expert Opinion on Drug Safety. 2020;19(9):1069-1094.

- Nicolini LA, Canepa P, Caligiuri P. Fulminant Hepatitis Associated With Echovirus 25 During Treatment With Ocrelizumab For Multiple Sclerosis. JAMA Neurology. 2019;76(7):866-867.

- Ciardi MR, Iannetta M, Zingaropoli MA, Salpini R, Aragri M, Annecca R, Pontecorvo S, Altieri M, Russo G, Svicher V, Mastroianni CM, Vullo V. Reactivation of Hepatitis B Virus With Immune-Escape Mutations After Ocrelizumab Treatment for Multiple Sclerosis. Open Forum Infect Diseases. 2019;6(1):ofy356.

- LiverTox: Clinical and Research Information on Drug-Induced Liver Injury [Internet]. Ocrelizumab. 2012. Directly downloaded from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK548145/.

- Kaplowitz, N. Idiosyncratic drug hepatotoxicity. Nature Reviews Drug Discovery. 2005;4,489-499.

- Reuben, A. et al. Outcomes in adults with acute liver failure between 1998 and 2013: An observational cohort study. Annals of Internal Medicine. 2016;164,724-732.

- Chen M, Borlak J, and Tong W. High lipophilicity and high daily dose of oral medications are associated with significant risk for drug-induced liver injury. Hepatology. 2013;58,388-96.

- Robles-Diaz, M. et al. Use of Hy’s law and a new composite algorithm to predict acute liver failure in patients with drug-induced liver injury. Gastroenterology. 2014;147,109–118.

- Hayashi, PH. et al. Death and liver transplantation within 2 years of onset of drug-induced liver injury. Hepatology. 2017;66,1275-1285.

- Castiella A, Zapata E, Lucena MI, Andrade RJ. Drug-induced autoimmune liver disease: A diagnostic dilemma of an increasingly reported disease. World Journal of Hepatology. 2014;6(4):160-168.

- Liu ZX, Kaplowitz N. Immune-mediated drug-induced liver disease. Clinal Liver Disease. 2002;6:755-774.

- Alla V, Abraham J, Siddiqui J, Raina D, Wu GY, Chalasani NP, Bonkovsky HL. Autoimmune hepatitis triggered by statins. Journal of Clinical Gastroenterology. 2006;40:757-761.

- Grasset L, Guy C, Ollagnier M. Cyclines and acne: pay attention to adverse drug reactions! A recent literature review. Revue de Medicine Interne. 2003;24:305-31.

- Ibrahim AM, Jafri SM. A Rare Case of Refractory Drug Induced Liver Injury Following Ocrelizumab Use for Multiple Sclerosis. The American Journal of Gastroenterology. 2022;117:2914-2917. DOI 10.14309/01.ajg.0000868304.44094.3b.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).