2. Literature Review

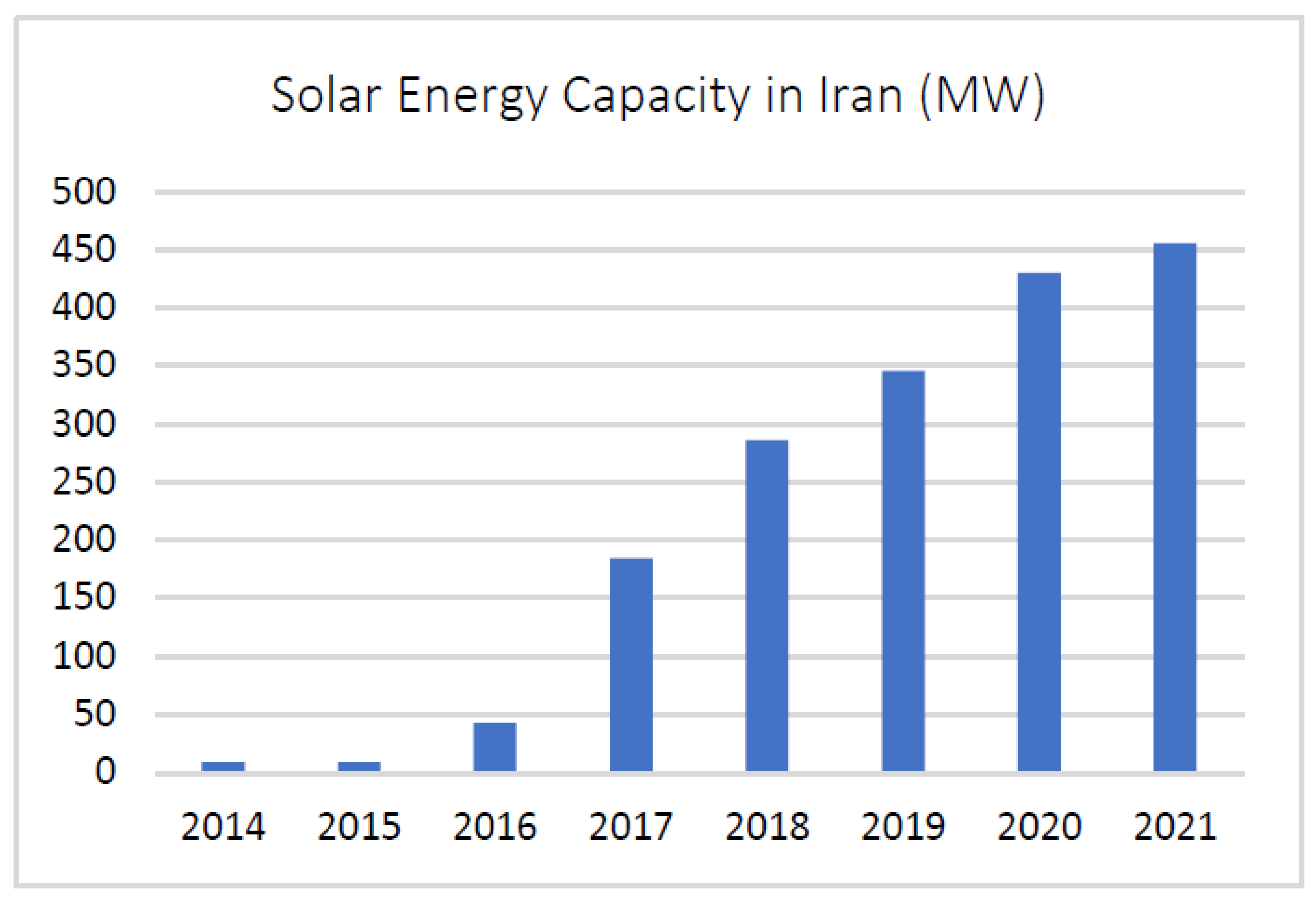

Solar businesses with definition and dimensions under focus of this study, have gained minor attention in academic literature. The literature of social acceptance has either overlooked them or has considered them implicitly as diffusion facilitators. They are investigated mainly in grey literature and in market (ing) field, as one of the co-benefits of energy transition, regarding the high job employment creation via these businesses. Though the sociotechnical transition literature, has mainly focused on solar energy technology development. Here I focus first on empirical global studies on socio-technical aspect to PV development, and then will review the literature in Iran solar energy (specifically) and RE (generally) development.

Penazola et. al., conducting a literature review and survey in 2022 tried to find market and social acceptance effective factors in Europe [

16]. They reported economic factors,

legal issues, business

models, and

lack of information, and

trust as the largest barriers against the businesspeople. Elmustapha et. al. in 2018 conducted a case study research design with a focus on solar PV and thermal niche market development in Lebanon. They wanted to find challenges of business and financial models towards decentralised solar systems, in developing countries context. They interviewed 30 experts from diverse groups of stakeholders, and the data analysis was done against business model and SNM literature. They found

knowledge transfer and

community empowerment [

17] as challenges for business models in decentralised solar systems. Seeking to understand the

success and failure of solar energy technologies diffusion, Elmustapha et. al. in 2018 used SNM framework to compare solar thermal and solar PV niche development in Lebanon, tried to answer first: how solar PV and thermal niche in Lebanon developed? And second, how can SNM help to understand this niche development in the context of a developing country context. They found that solar thermal niche affected solar PV niche, specially in relation to learning and coordination processes. Though both niches lacked a niche manager who was able to coordinate, manage, and maintain dynamics of niche processes, the same with horizontal collaboration between involved key actors [

18].

Warneryd et. al. in 2020 in Sweden, conducted an empirical research based on 15 semi-structured interviews, with a contribution to the sustainability transition theories. They tried to understand first, the

added values of installing PV over large buildings for the owners as the actor groups, and second, they

investigate to find the contribution of these values in PV development in Sweden. They found sustainability, fair cost, and induced innovativeness as the added values, moreover to their contribution to social network development, new role development, positive niche narrative, and niche empowerment [

19]. Pederson et. al. in 2018 set out to investigate the practices and business approaches of private sector in solar mini-grid development in Kenya. The objective in their study is to understand how niche actors are influencing and creating change in the incumbent electrification regime of grid extension in order to strengthen and expand this niche. Moreover to internal niche processes like the alignment of expectations, learning and network building, they analyse that niche actors actively engage in various forms of regulatory institutional work in order to influence legal and economic frameworks. Though niche actors also engage in cognitive institutional work to enhance acceptance of the niche technology by constructing a shared world view between niche and regime actors. Interestingly, niche actors also engage in normative work to establish positive normative associations with the private-sector model, like equity and social justice [

20].

Taking a socio-technical regime concept, Zhang et. al. investigated the barriers towards solar PV development in China, [

21]. They investigated the solar PV policy in China between mid-1990s to 2013 in four episodes. Different combinations of policy programs for each interval are introduced as a reason for the erratic path of PV development. Moreover, wider policy priorities, government’s poor management of policy interaction between manufacturing and deployment solar PV have been reported as the main sets of variables that resulted in the trajectory of solar PV sector. They concluded that subject to some political, economic, and learning forces, the development path to low-carbon transition is likely erratic. Mirzania et. al. conducted a comparative study in South Africa and US in 2020, with a focus on CSP. Utilising the SNM to analysis to investigate the reason for the very low uptake in South Africa vs. US, despite the abundance of natural solar energy. They conclude that consistent policy support in the US, bridging the gap between research and development, the main reason for the successful diffusion and adoption of CSP. Though the development of CSP in South Africa has been hindered mainly due to several technological expertise and economic fundings [

22].

Danielle Denes et. al. in 2018 investigated the challenges and opportunities of PV growth in Brazil. Taking a socio-technical perspective based on qualitative interviews with actors, they combined a MLP and systems perspective for data analysis. Long-term goals establishment, fiscal and financial incentives, attractive opportunities for the investors, and professional transiting courses are some of the main recommendations out of their study. Criticising MLP and innovation system functions is also included in this study [

23]. Darmani et al. in 2017, have categorised the empirical drivers of RE technologies (wind, solar, wave, and biomass) development in 8 European countries. They determined 5 main categories of drivers: incentives for actors, institutional incentives, network incentives, technological incentives, and regional incentives [

24]. Hansen, Wieczorek et. al. have also emphasised the burgeoning field of sustainability transition research in developing countries [

25]. Wieczorek mentions that MLP, SNM, and TM as the major sustainability transitions frameworks, have been mainly applied in better economic level, developed countries in order to motivate and clarify the socio-technical transformations [

26]. Conducting a systematic literature review on 115 articles in the last decade, she presents conceptual lessons and novel methodologies around path-dependency and other issues of sustainability transition literature.

Focusing on empirical studies in Iran, Mostafaeipour et. al. conducted a case study in Alborz Province, based on questionnaire and interviews to discover barriers and challenges of solar energy development in Iran. They categorised the barriers into 5 groups: technical, legal, economic, sociocultural, and support. To find the importance of the identified criteria, they applied the

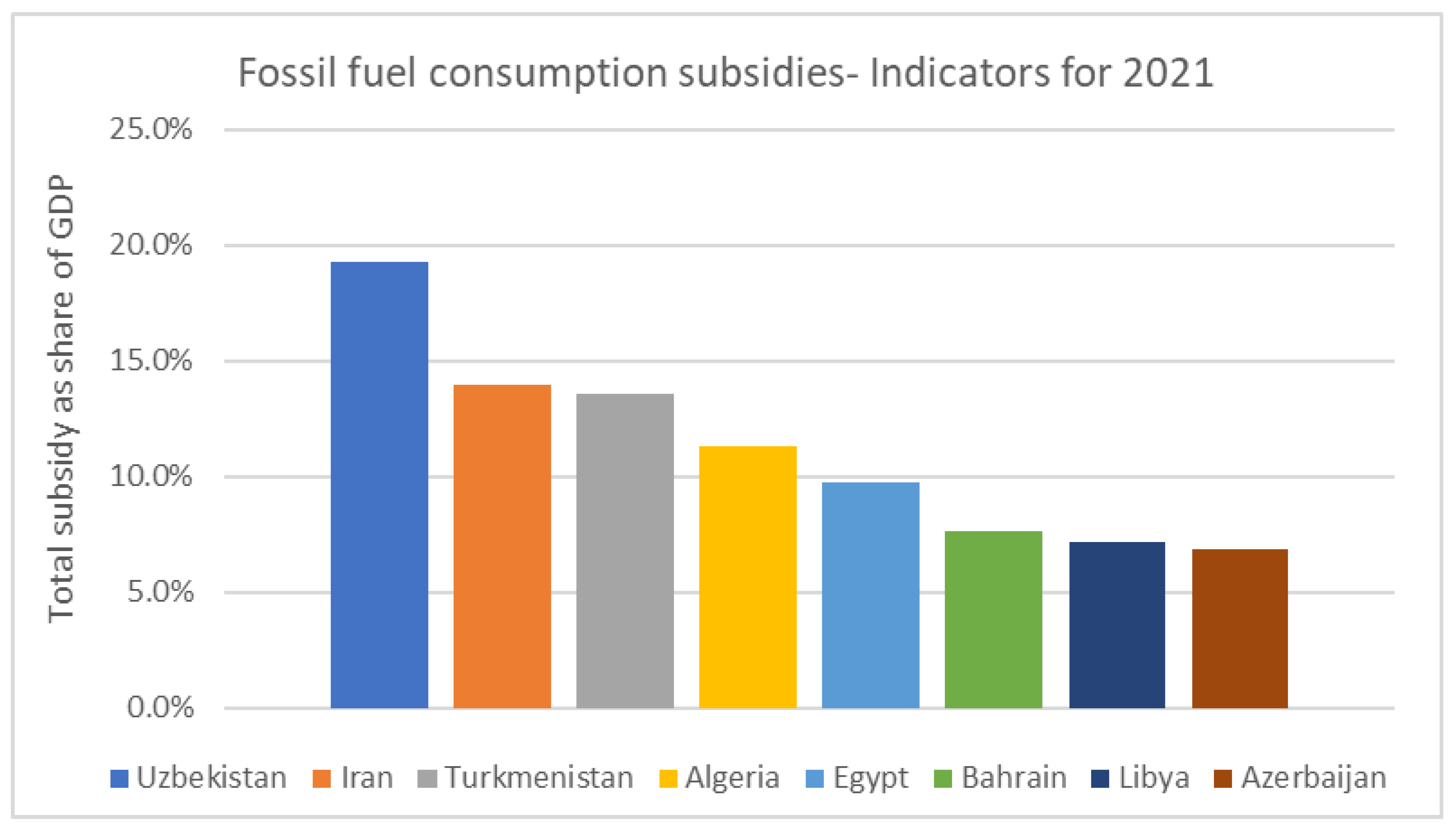

fuzzy Best-Worst method. They prioritised economic barriers with the external effect of sanctions, as well as the high risk of making new business. Though the low price (highly subsidised) fossil fuels. They suggested supporting the private sector by financial incentives to develop the solar energy in Iran [

27]. Massihi et. al. in 2021 conducted a study on

utility-scale solar farms, and investigated the business environment analysis model in Iran [

28]. Using meta synthesis method, they found 8 dimensions containing 34 variables as effective factors in solar energy businesses in Iran. Deriving a priority diagram, causal stock, and flow diagrams, they concluded that solar electricity in the long term is economically efficient and can help to protect the environment. Rezaei et. al. in 2018, conducted a study to identify factors affecting PV application in Iran. They reached to 142 factors through a literature review, all were prioritised then via interviews with energy policy experts. They conclude 10 generic categories of factors to be considered by policy-makers in Iran solar PV sector: policy, institutional, finance, system economy, macroeconomic, socio-cultural, human resources, industry capabilities, technological and infrastructural factors in three levels of

industry, national, and international [

29].

Historical analysis of solar PV development in Iran was also done by Rahimirad in 2018 via the lens of TIS [

15]; and 2017 [

15] Khayyatian et. al. in 2020 via

institutional approach [

30]; focused on policymaking and

governance in 2020 [

31], and by Fartash et. al. in 2020 [

32] (no MLP, SNM, or TIS approach) [

33]. Conducting a mixed method research in 2018 in Iran, Zohre Rahimirad et. al. [

34] asked: which socio-technical barriers exist ahead of transition to solar PV? Though they interviewed

elites mainly, and reported 10 barriers in 4 main categories by the incumbent regime ahead of niche innovation: economic, institutional, political, and technical. The same group of authors in 2017, studied the solar PV as technological innovation systems (TIS) in Iran [

15]. Assuming the developing countries as mainly importing technologies, and the developed countries as mainly TIS emergence, they investigated the TIS based on R&D; as well as diffusion. Though in Iran TIS is mainly based on import and assembling infrastructure, therefore they focused on Diffusion. They introduced the innovation motor in photovoltaic in each interval. To identify

incentives and barriers of Solar PV TIS (Technological Innovation Systems) in Iran, Sadabadi, Rahimirad et. al. conducted a qualitative study in 2022 and they concluded barriers in 4 main categories (Economic, institutional, political, technical); and incentives in 6 categories (political, institutional, economic, social, technical, infrastructural, and geographical) [

4]. Esmailzade et. al. in 2020 conducted a research via combined MLP and TIS to investigate the macro factors influencing the PV in Iran [

35]. They found government policies, oil crisis, economic growth, and downturn as the most influential macro factors (in the socio-technical landscape level) in PV TIS in Iran. Khayatian Yazdi et. al. studied the PV niche development in Iran with strategic niche management SNM aspect in the time interval between 1990-2019 [

33]. That was a qualitative study based on qualitative interviews with elites in solar energy field in Iran. Presenting a historical review, they showed a slow increment in the actors’ network from 1990, and reaching the educational and knowledge network in 2000, to production and service actors in 2010. Moreover, the effective role of external events like JCPOA and external investment on expectations development and PV actors’ network was explained.

In summary, despite a considerable investigation of socio-technical transition via the lens of sustainability transition theories, the empirical studies in developing countries regarding their specific contextual factors is scarce. Second, the role of easy access to fossil fuels as non-renewable energy resources has been minorly paid attention to. Third, the role of a specific group of stakeholders, as RE niche actors has been of little emphasise yet. This could be the diverse transition pathways, and governance forms as well as the contextual factors in countries, that gives diverse priority to different key stakeholder groups in better democratic and developed countries. Global northern countries as not only the origin of sustainability theories, but also the geography of most frequent empirical studies in this field, despite studying the niche actors have paid minor attention to solar PV businesses.

4. Results

Drivers of solar business (establishment) acceptance in Iran

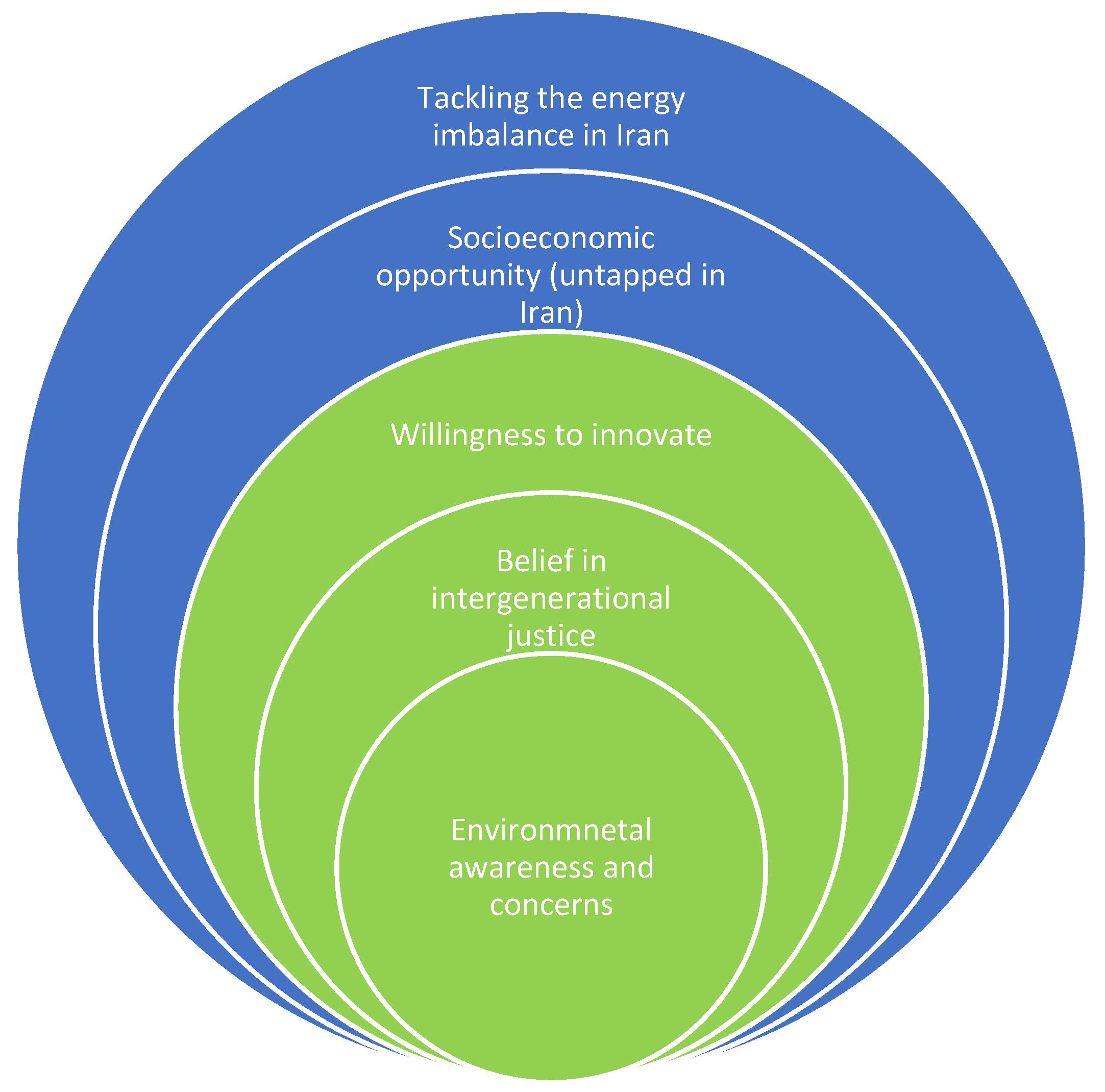

I understand that the businesspeople are driven toward solar PV business via a mix of interlinking intrinsic and extrinsic factors. Based on my analysis, environmental awareness and concerns, belief in intergenerational justice, in addition to willingness to innovate, drive solar business niche actors intrinsically; while the socioeconomic opportunity grounded in untapped solar energy market in Iran, plus tackling (compensating/balancing) the energy imbalance in Iran, do drive them externally in their field of career. I dive into each of these concepts more deeply, citing quotes in the following sub-sections.

Figure 6. Shows a schematically the empirical intrinsic and extrinsic drivers of solar businesses in Iran.

Intrinsic drivers

I find the solar businesspeople environmentally conscious and concerned. Moreover to their love in nature, issues like weather/ water/ plastic pollution and their health impacts, deforestation, mazut burning in power plants (specially after the energy imbalances in Iran [

39]), extreme climate events in Iran and similar topics matter them. According to my interviews, these ecological concerns drive the solar businesspeople partially toward their activity in solar energy field, with the least impact on the environment. Talking about his love in nature and attempts to reserve it, an interviewee explained,

“I can’t imagine living in Tehran1. I have always rejected any job opportunities (even if higher paid positions) there. To me, it is all concrete jungle, and awful air quality. Being originally from north of Iran (rich with greenery), I am in-love with nature, and I do my best to deserve this green paradise” Q4: 21. He continued,

“It has always been my prior mission, in all my career activities, and during my teaching experiences, to expand this vision of environment preservation”Q4: 22. Another young interviewee expressing her regret on waste management and plastic pollution explained:

“Unfortunately, we witness factories around who continue to produce waste without thinking/measuring of their harm to the chain in the environment. All this plastic pollution affects ecosystem and the natural processes, produce chemical pollution, and harmful diseases for human being. Sure, one of the rational justifications for all this investment in SPV as a RE, is its environmentally friendly aspect” Q12: 24. This quotation proves first the interviewee’s ecological awareness, and second its motivating role in his business. Polluting industries in Iran and the death toll attributed to weather pollution toward an unsustainable development have been repeatedly alerted by the Department of Environment in Iran during recent years [

40]. I understand the energy awareness and concerns, in parallel with/included in environmental issues, as a driver toward their career in solar PV. An interviewee uttered her point in this way:

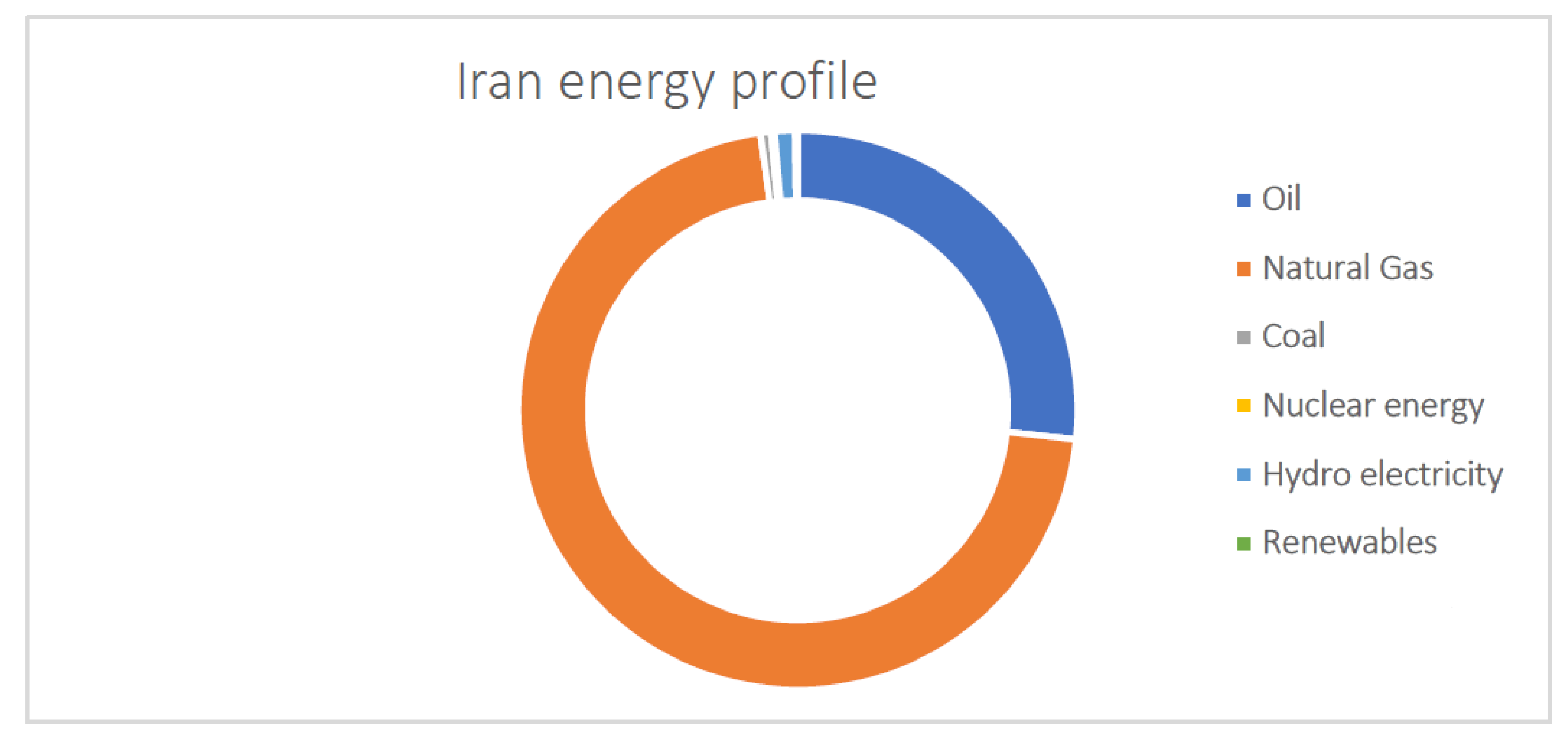

“… with respect to our (bad) consumption pattern in comparison with the global average, I am really afraid of a possible tragedy that we wake up a day and see that we have consumed all our gas and oil as limited underground energy resources, and on the other hand we haven’t invested in RE field yet!” Q14: 8. This quotation reveals that they have apprehensions regarding the least diversified energy sector in Iran and threat of energy poverty, in an energy-resource rich country.

Moreover to environmental and energy concerns, I find their belief in intergenerational justice, as another significant driver. Some interviewees emphasised their prosocial motivations as driving factor toward their businesses. Having a sustainable mindset, they want to preserve the nature and energy resources for the next generations, and they perceive their activity in solar energy as a renewable and environment-friendly source of energy, as partial contribution. They explain part of their motive, as greater (common) goods for others (mainly next generations), and not only focused on themselves and their own benefits. An interviewee talking about his own obsession about preserving the nature via cutting down on fossil burning said, “I ask myself, why should the next generations get deprived of seeing this beautiful nature, just because of our ignorance in burning the polluting fuels? And not paying attention to preserving the environment? I have the desire to protect the nature for my grandchildren. The protection of natural environment and expanding this attitude has been always my priority in my whole professional work. Trying to expand this perspective, in our job background, we should do our best to change the fossil-cantered visions” Q 13: 5. This quotation shows nicely the confrontation of the incumbent fossil-based vision and the RE vision among these niche actors. I find that this intergenerational aspect (based on environmental concerns), does partially justify the investment in solar business among the businesspeople in Iran. An interviewee answering my question about the economic justification of their business in this field in Iran, as a fossil rich country, explained: “Sure, one of the main factors that justifies our activity and investment in this field, is the green nature of solar energy, vs. fossil fuels, and its intergenerational benefits. Just look at the irresponsible (environmentally) industries. Solar as a type of RE, is really safe for our next generations …” Q 14: 24. Admitting the RE and fossil conflict, regarding their diverse carbon footprint, this quotation addresses the priority of intrinsic drivers to extrinsic (economic benefits) among interviews.

I find solar business owners’ willingness to innovate, as another intrinsic driving factor. Solar PV market in Iran being still in niche level, and approached (generally) as an innovation, is welcomed by a limited range of society (solar businesspeople) who have higher levels of venturesome and can cope with higher levels of uncertainty. This willingness to revolutionise was clear in almost all my interviews, and in diverse shares of businesses. Coming across some initiators, who have left such a positive lasting impression on Iran solar PV development history, an interviewee explained about his innovation story referring to some 40 years ago, “Following my passion in power electric, focusing on solar panel and understanding its function, I installed the first solar PV system (rooftop) in Iran. It refers to 1981, when it wasn’t yet known publicly. It made some troubles first with the Electricity Distribution Company since they couldn’t figure out my house electricity bill. Then, I could persuade them, and explained the system and its functionality. That was a hit at that time, so I got broadcasted via the national TV channels, Channel 1, News Channel, Our Province Channel ... They titled: The first user of solar energy in Iran!” Q4:5. This quotation shows a clear link between solar system which is perceived as an innovation and the interviewee’s motive to innovate. I understand that this motivation, leaving less resistance against new ideas, is not only limited to solar PV, but also drives them in other fields of innovation. Starting new fields of experience, an interviewee explained about his activity in Building Management System (BMS), as a very recent field in Iran: “We have been the 2nd in Iran, that built and offered this computer-controlled system which is installed in buildings. The first was accomplished in Tehran, here we built this controlling and observation system and we do offer an educational syllabus at Technical and Vocational Training Organisation” Q2: 13. As early knowers of this innovation, they have higher levels of venturesome. As this quotation suggests, this willingness to innovate, does link the solar businesspeople with educational and academic institutions as innovation-fostering centres. I find this willingness to innovate as an intrinsic driver which is linked with some extrinsic motives, grounded in the current situation of Iran. I explain two other drivers (extrinsic) in the coming paragraphs, that the innovativeness of interviewees, do also drive them towards. They want to be the pioneers who employ the “untapped solar energy market” in Iran; the same with “tackling the energy imbalance”.

Extrinsic drivers

I find that the socioeconomic opportunity regarding the untapped solar energy market in Iran drive the solar businesspeople (extrinsically). Accounting Iran’s solar irradiation potential (technical potential) with 300 sunny days annually comparing with the image of the prosperous countries, employment opportunities in RE as one of the co-benefits, they are motivated in their business. An interviewee analysing the job opportunity in Iran said, “Our country is on the one hand rich with solar energy, and it must diversify its electricity sector, though the technology is not generally known; the gap btw. NEED and Knowledge just shapes a good market for it. The solar energy market in Iran is literally untapped, and it promises fantastic and colourful job opportunities … though other supportive presumptions are absent yet” Q12: 18. This quotation reveals that the drivers prevail over the barriers, in perception of these solar niche actors who believe in change. Another interviewee regarding his belief in transition from fossil to RE, and the desired socio-economic opportunity said, “The reason we do insist in this job despite the whole un-supportive policies, is that we do believe that the future is based on renewable energy resources. Knowing that fossil era is coming to an end, Iran MUST also join the global transition. The earlier, the merrier! Exploiting the rich solar energy (let alone other RE resources), and narrowing down on fossil subsidies, can ignite huge opportunities for the young workforce in Iran, to name but a few …” Q1: 140. I appreciate that the businesspeople in SPV field, have an up-to-date perspective on energy resources and the necessity of transition. They perceive the shift from fossil to RE as a MUST, and in their attitude, the future is based on renewable energy which is one of their main drivers in their business.

In addition to the untapped solar energy market in Iran, I find tackling the energy imbalance in Iran via solar energy, as the second extrinsic driver among my interviewees. This is a very recent and relative issue; regarding the rapidly growing energy (electricity and gas) demand due to economic and population growth, plus some natural and manmade reasons, imbalance in energy demand and supply resulted in explicit blackouts in summers and gas outages in winters. This trend that is started from summer 2021, has shaped some expectations/motivations among solar PV niche actors. According to my interviews, tackling the energy imbalance via solar PV, mainly over industrial and commercial units (in MW capacity), drives the solar businesses extrinsically. An interviewee admitting the point said,

“... We are now experiencing electricity outages in some provinces of Iran, and this trend is predicted to continue, not only in electricity but also in gas sector, during peak uptake times (summers and winters). It means that with this summer, we have entered a time interval with frequent electricity and gas outages during summers and winters. This circumstance does sure update the attitudes towards solar PV; it will be approached no longer as a luxurious good!” Q8: 30. By “Luxurious good” he addresses the existing limited niche market for solar system in Iran, as approaching solar PV of little consequence. The quotation reveals also implicitly the positive attitude toward energy transition as an

addition to energy supply, than a real

transition, via managing the growing energy intensity and efficiency in the country [

41].

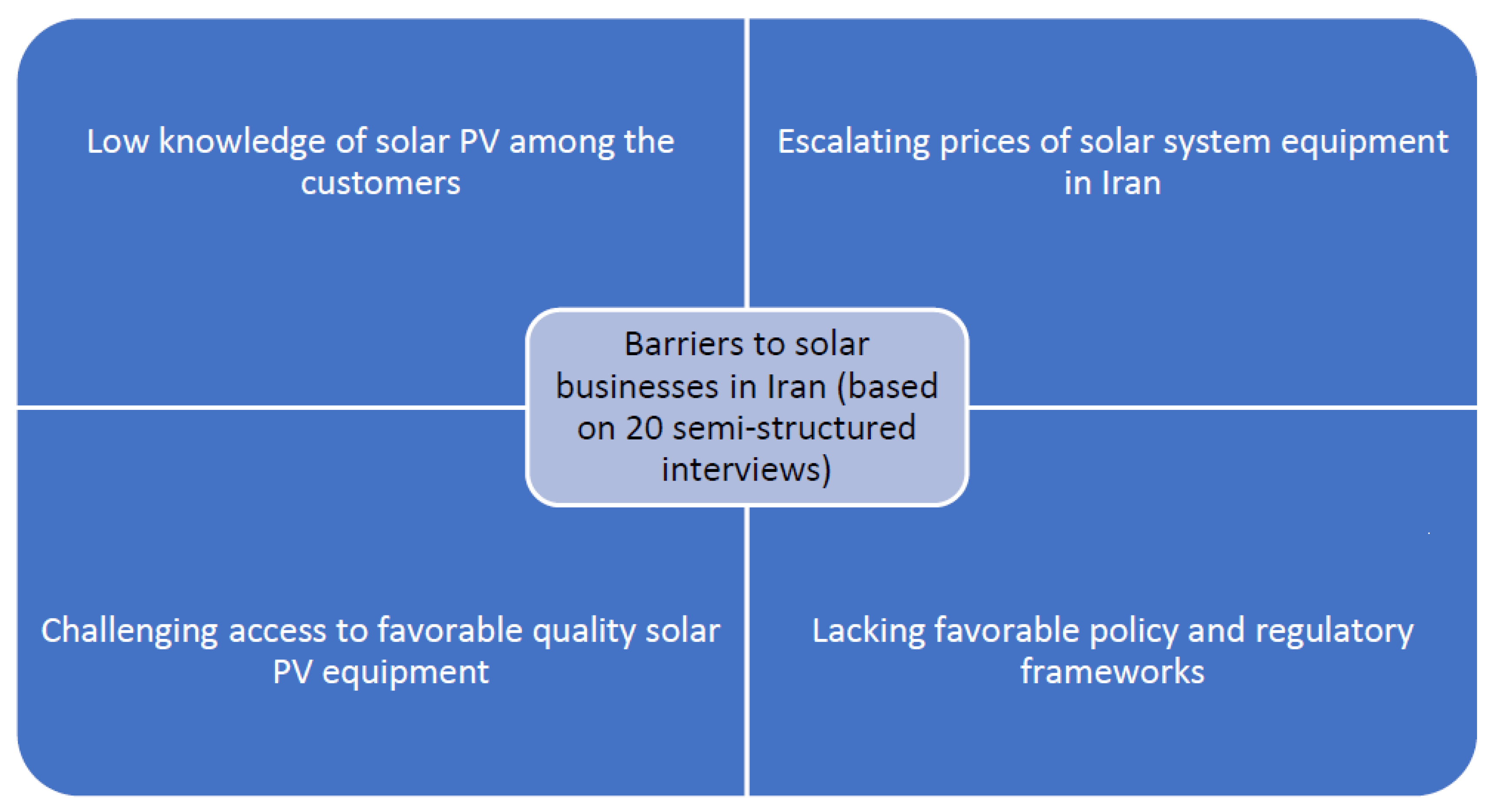

Barriers of solar businesses in Iran

According to my interviews’ analysis, existing barriers ahead of solar businesses, can be distinguished in 4 main interlinked analytical categories: social, economic, technical, and political. All these categories were found in all interviews, and they were further structured in main storylines narrated by the interviewees of their existing market shares. In short, they are providing service, which is first unknown, of not stable prices (overall increasing), of no reasonable quality and with unsupportive policies. In the following sub-sections I explain each category in more details.

Figure 7. shows a schematic of the empirical barriers ahaed of solar businesses niche in Iran based on 20 semi-structured interviews.

Low knowledge of SPV among customers

I find that solar PV remains largely unknown to many consumers, and this is perceived as a foremost barrier against solar businesspeople. According to my interviews, this low knowledge is due to a lack of awareness and understanding of SPV technology, its ecological benefits, its political and regulatory frameworks governing tariffs, administrative requirements before installation, and financial costs associated with implementation and maintenance of solar system. Despite the low knowledge among public society, no real effort to raise it and fixing the gap, by governors is another part of the problem. According to my interviews, no media plays any active role in rising general knowledge about solar PV among the society. An interviewee said, “to my understanding, the mass media and even above all, their owners and managers have failed (have shortcomings) to introduce solar energy, technically, environmentally, and even the policies, … to the public society!” Q4: 18. It is worth mentioning that regarding the heavy control/govern of the central government over the media in Iran, this limited information provision, is perceived as part of “no political will and vision” toward energy transition. Here, I understand that the solar businesses are playing significant role to compensate the knowledge shortage; I explain that more deeply in section: roles.

I find some major consequences for this low knowledge of consumers, based on my interviews. First, having no knowledge about the potential benefits of solar PV, does hinder its adoption and reduces investment therein. Second, lack of knowledge/awareness about this innovation (in Iran), does lead to scepticism or resistance in cases. According to my interviews, being unable to figure out this technology, and its maintenance, some potential adopters cannot trust, and they perceive it as a risky investment. In the third as the most catastrophic scenario, the lack of sufficient knowledge about this technology, can hinder, if not interrupt its diffusion process. From the perspectives shared by my interviewees, in a still niche market for solar PV, the low technical knowledge about this technology, in combination with constantly rising prices of solar PV system making it less affordable for customers, in addition to limited access to good quality equipment, and no real observation from the top (energy governors or involved governmental organisations) over the deployment process, some (even if scarce) under-qualified solar system installers and technicians have entered the market. The mixture of these obstacles, cantered with the lack of knowledge, can lead to serious unsatisfaction among the limited adopters and spoil the image of solar PV in the public. An interviewee narrated: “… to me the biggest problem in PV -being still an innovation in Iran- is that people have no technical knowledge at all. On the other hand, there is no observation on installers’ activities. Anyone could offer a cheap price and install PV (on or off-grid) for consumers. They spoil even the existing niche market. If you go to X village where the majority of people are using off-grid PV, you see many who are not satisfied. Why? Since they are using the low-quality system offered by the least responsible service providers … If people get aware via broadcasts for example, that will really improve the situation for us” Q7:6. According to my interviews, this low knowledge, is not limited only to the lay people, but it contains some of the governmental organisations’ decision makers. According to my research conversations, lack of awareness among the decision makers in these organisations, has been one of the major factors for failure to enforce the law. An interviewee mentioned: “... in one of our meetings with X governmental organisation, where we were supposed to discuss the roof-top solar power installation for poor families- covered by charity- to get benefitted via FITs, …. the manager of the complex expressing his reluctance, suggested (seriously) raising some domestic animals, sheep, chicken and … aviculture, and animal husbandry instead!!! This way of thinking paralyzes us!” Q3: 4. This reveals that there are still some authorised people in the system, who have not yet believed the necessity of energy transition. This is perceived (by solar businesspeople) as a mix of low knowledge, and no political will & vision among decision-makers.

Escalating prices domestically, despite falling prices globally

I find the constantly escalating prices of solar equipment as a significant barrier ahead of solar businesspeople in Iran. This is just opposite the global statistics and experience of the rapidly declining LCOE of solar PV (as a RE) that makes it more competitive in the energy landscape [

42], [

43], [

44]. According to my interviews, the increasing prices do narrow down the solar energy market and make this investment even none-sense. An interviewee admitting the non-economical investment in Solar PV due to the price rise said:

“With these huge price escalation, solar PV is not cost-effective anymore. It doesn’t really make sense to pay 300-400 million tomans (1 toman= 10 Iranian Rials) for the same solar system that costed 150-200 million tomans last year at this time!” Q6: 3.

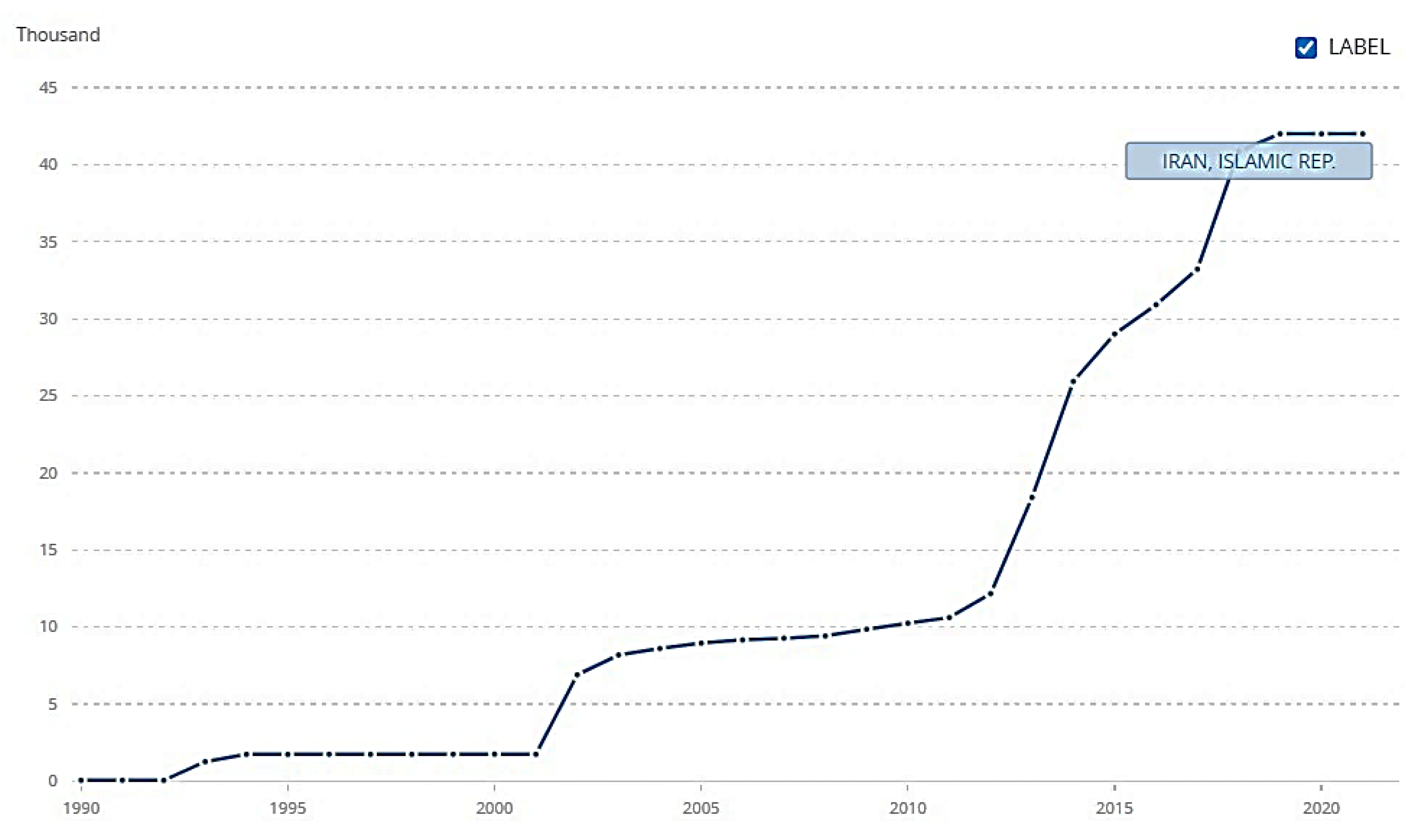

The increasing price of solar equipment has been the result of inflations (

Figure 5, 2010-2021) or domestic currency rates depreciation, as shown in Figure 4 (or both simultaneously). The none self-sufficiency of Iran in solar technology, makes it dependent on the imports, mainly in PV modules and inverters [

15], [

45]. I understand that the increasing prices domestically, do either

deter customers of solar PV adoption at all, or force them to

settle for lower capacities (that has its technical consequences2). Both cases are restrictive for solar businesses. This is reflected in this quotation for example:

“We have witnessed cases where the party had decided to build a power plant when the construction cost was 35 million tomans. He was looking for administrative works, obtaining permits and government loan, when the costs rose to 100 million tomans (almost three times) in a short period of time. That was due to Rials depreciation against Dollar. Of course, the project was cancelled, as it was beyond the financial capacity of the party” Q7: 4.

Besides rejecting solar PV, or settling for lower power solar system installation, I find some other consequences of rising prices, and low purchase power of customers. It lengthens the payback period, which reduces the customers confidence in solar PV investment. Moreover, it forces lower quality materials deployment, or not complying the necessary standards mainly due to taking service from under-qualified technicians. The last case is possible since there is no serious observation over the work of installers and complying the standards specially in off-grid solar power plants (as mentioned before). According to my interviews, all the cases, do spoil the image of solar PV which is unfavourable specially in a niche market.

Figure 8.

The World Bank Data on the official exchange rate in Iran 1990-2021.

Figure 8.

The World Bank Data on the official exchange rate in Iran 1990-2021.

Figure 9.

World Bank Data on Iran Inflation rate2010-2021.

Figure 9.

World Bank Data on Iran Inflation rate2010-2021.

Challenges with both domestic and imported equipment.

I find the hard access to good quality materials as a common bottleneck for solar businesspeople. This includes both domestically produced (though limited) and imported products.

According to my interviews, the domestically produced equipment are either of low quality, or are not available in sufficient diversity. An Interviewee talking about inverter as a key element in solar systems that is not available in desired capacities, said: “We have domestically produced inverter that is made via inverse-engineering, but only to 5 KW power. For higher capacities, we should import from abroad” Q13: 11. The ‘inverse-engineering’ method mentioned in this quotation, emphasises on not yet self-sufficiency of this technology in Iran.

Another gap with domestic products, is their low quality and/or efficiency that force reduced power output, or higher costs to compensate reduced power output, and reduced lifespan. An interviewee pointing at domestic solar panels mentioned, “The domestic solar panels of X company, have maximum 17% efficiency, which cannot compete with the common 19-21% efficiency panels (globally). To cover this low efficiency, we need to increase the number of panels that increase the total price of solar system. On the other hand, the nonefficient qualities, reduce the long lifespan we usually advertise talking about solar systems” Q7: 10.

Besides the domestic products’ challenges (and as a partial result of it), I find some bottlenecks in imported equipment as well. According to my interviews, there are in the first step, either national or international (geopolitical) limitations on imports, that restricts the entrance of good quality solar panels, batteries, or inverters. The national limitations refers to the obligations to go domestic products, to empower the domestic economy and industry, addressed as ‘resistance economy’ [

46]; and the international limitations denotes the sanctions under the JCPOA. An interviewee addressing these restrictions said,

“with some lifted sanctions around 2015-2016 we had access to really acceptable brands, X & Y, of panels and inverters while after reimposing the sanctions in 2018, we had to suffice the domestic equipment. This Z national factory that has filled the market with its low-quality panels, doing lobbies and getting supported through ‘resistance economy’, does enforce limitations in imports. We are sort of compelling our customers to accept these qualities” Q16: 10.

Based on my interviews, the second obstacle in the field of imported equipment, is transferring money following the same reimposed sanctions forcing banking limitations. A respondent explaining this obstacle, stated

“To transfer money to China for example, we have to send through the UAE or Turkey. If we send directly from Iran, the money will get blocked regarding the banking limitations. This indirect transference is linked with excessive tariffs that adds to the final price (and is not desirable). This limitation has been forced since reimposing the sanctions” Q13: 9. This refers to the US treasury action that sanctioned some key sectors of Iran’s economy [

46].

I understood that even in case of overcoming these import obstacles, the solar businesspeople are challenging with some after-sales services. From the feedbacks of my interviewees specially for batteries and inverters, taking after-sales services in linked with long waiting time, and high risks. An interviewee stated that, “Importing batteries for example, is desirable for us generally, but it is risky. Taking warranty is not simple and takes long time, sending and then waiting …. It is full of stress for us. We should persuade the customer during the whole time, ….or to make him suffice to replace with a domestic battery substitution in the end” Q2: 8. The quotation reveals the sanctions barriers even in the field of after-sales services for some company’s products, let alone the high import duties imposed by Iran.

Lacking a favourable regulatory framework

I find the cheap price of fossil fuels, like gasoline, gasoil, kerosene, and … as a barrier for solar businesses in Iran.

Solar PV is not cost-competitive with fossil resources. The easy access to these fossil resources, mainly for diesel generators to be utilised at farms to pump water, or for lighting, does limit the market of solar PV as a green alternative. According to my interviews, there exists a considerable gap between solar PV demand in regions with

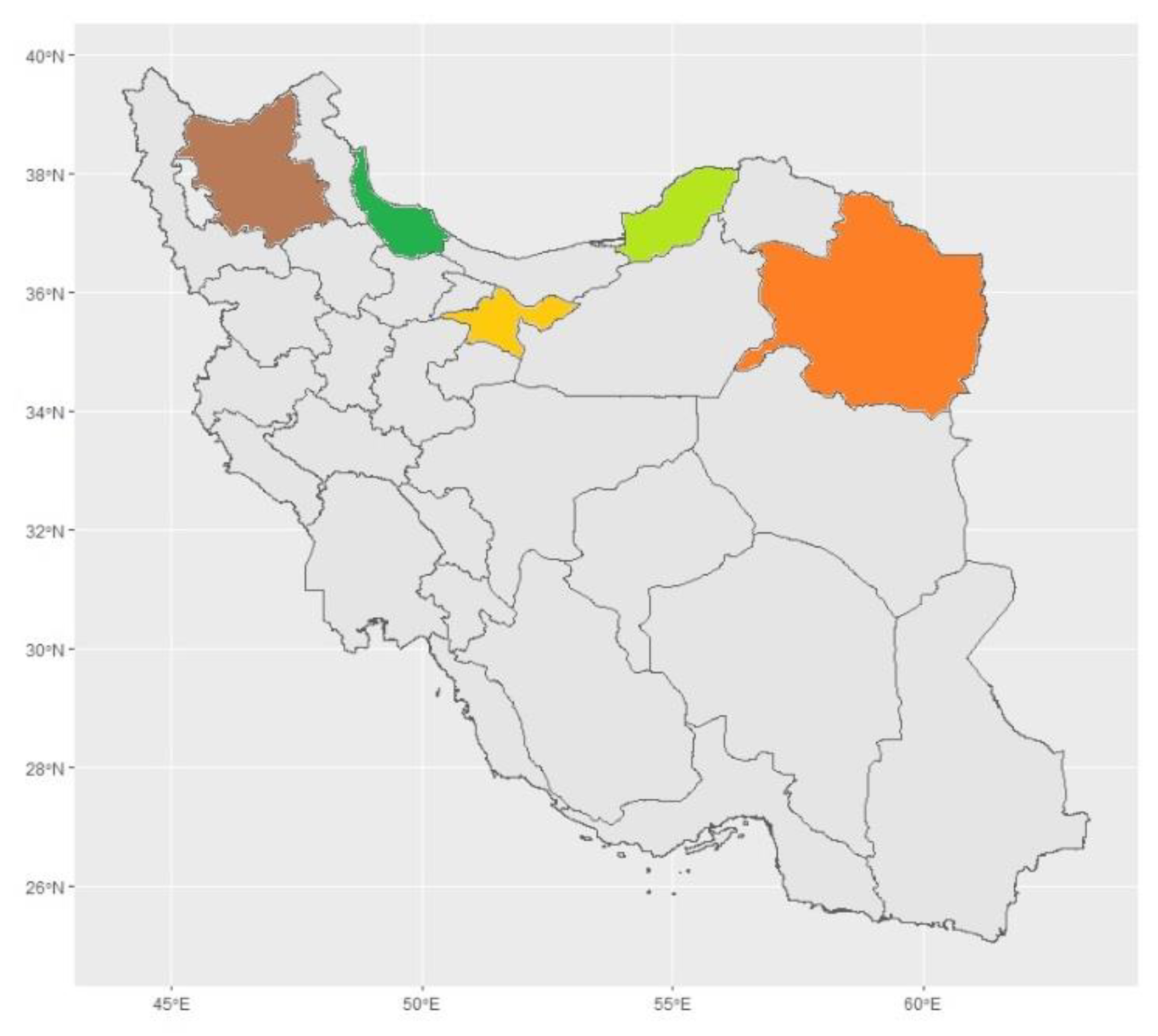

hard and expensive access to fossil fuels, and other regions with easy and cheap access! Comparing the solar PV market in Sistan and Baluchestan

3 with the rest of Iran, regarding the significant role of easy access to cheap fossil, an interviewee explained,

“We also provide service at the border areas of Sistan and Baluchestan. It is literally our best market shares. We install solar systems not only for lighting, but also for running solar water pumps over the farms. We are contractors of big projects there. The price of diesel there, is not only higher but it is hardly accessible there. This forms a great market for solar PV. A typical farmer in Sistan-Baluchestan needs to prepare this hardly accessible diesel to feed his diesel generator for water pumps or lighting. By installing a 5 KW solar system for maximum 60 million tomans, the whole hardship (for farmer) is omitted. This deletes the noise and maintenance linked with diesel generator and would be a considerable cost-saving on top!” Q3: 5. Sistan and Baluchestan Province is one of regions in Iran that regarding the close connection to the neighbour countries, and the considerable price gap between oil and gas in Iran vs. neighbours, the fuel is usually smuggled. The government to control this trend, does increase the price of fossil fuels in Sistan and Baluchestan. A good market for the solar PV business in these regions, is a good benchmark to reveal the direct effect of fossil fuel subsidies in SPV diffusion.

Policies just on paper and not seriously taken in practice. According to my interviews, a considerable market share for solar PV is shaped following the upstream policies. Not complete implementation of the policy and no observation on the implementation of them, have been mentioned as limiting factors. Taking seriously the implementation of at least the self-authorised obligations, could have helped the solar PV deployment considerably. In addition, in almost all obligations, some defects in definition, has narrowed down the solar energy market in Iran. An interviewee explained the un-successful implementation of policies,

“... of the whole governmental organsiations in our province who were obliged to install the SPV, how many in our province can you imagine who have implemented it?! Less than 20%! Over the paper (emphasising the unserious nature of policy making), they were even supposed to get fined, in case of non-implementation to a deadline. This was neither implemented! The same has happened about other supportive policies, either regarding the budget deficiency or just no priority given to them” Q13: 4. By other supportive policies s/he means policies/obligations in which the energy governor (MoE, or SATBA, or Parliament, or any other governmental administrative) have defined decrees, to develop the solar PV installation/deployment. Some examples are the obligation on governmental organsiations to install SPV to provide at least 20% of their electricity consumption via renewable electricity resources- in 2016 [

47]. Some other similar policies are green management in 2019, and Jihad Roshanaei (2021), Bargh Omid (2020), and … all targeting to increase the solar PV development in diverse groups and mainly focus on charity and in-need people, for which some governmental incentives are considered … to motivate the adoption. On the top of no serious implementation, I find insufficient number of enabling policy frameworks as an obstacle. The solar businesspeople expect better supportive policy frameworks via raising incentives and favourable regulatory frameworks obliging solar PV installation. It is worth mentioning that the absence of serious observation, is not only limited to policies implementation. Based on what my interviewees narrated, lack of control from the involved governmental organsiations, over the qualification and installation process, does allow some under qualified service providers who install solar systems and provide services without complying the standards, or offering the lowest quality material. Specially in an economic limitation, with no knowledge in this field among the lay people, this not qualified business actors, can easily spoil the image of solar PV.

Which roles do solar businesses play in advancing solar PV deployment in Iran?

I understand 3 main roles for the solar businesspeople in Iran, that drive the solar energy development. There is no need to mention that there exists a clear relationship between the level of power and the effectiveness (diversity and significance of roles to be played) of different stakeholders. This is dependent on some contextual factors in each country, the (energy) governance structure, and economic system (liberalised or planned) to name but a few. The three main and prior roles according to my interviews, are educating people in technical and ecological aspect of solar PV, driving the adaptive deployment of solar PV system, and facilitating the diffusion of solar PV due to their extensive networks. I find the whole roles in social category, regarding the main exposure of solar businesses with the public society, and therefore their direct influence on social acceptance of solar PV. below, I dive into each role in more details.

Educating people

I find educating people, as the first and foremost role of solar businesses. According to my interviews, this is done via capacity building activities containing lectures at educational institutes, or at social communities in publicly visited places (like mosques, …), training workshops, holding seminars, webinars, or providing information online: over their websites, blog posts, or social media channels (Telegram, Instagram, WhatsApp), and advertisement over the billboards, publishing banners, and so on. I understand that three main branches for educating people by solar businesspeople: first, raising ecological awareness among the public society. Making them understand the concern of limited resources of underground energy specially in a society who has been left passive via an easy access to cheap energy resources, is perceived as a mission of this solar niche actors. Expanding ideas such as future generations’ right to exploit and get benefited from the natural environment, the emergence of taking measures for better weather quality (in major cities of Iran); and the disadvantages of burning fossil fuels, the need to switch to RE sources, with a focus on solar PV, have been some frequent subjects mentioned in my interviews. By giving this knowledge to the public society, they raise motivations for cooperations by people. I find that solar businesspeople have the will to cultivate society. An interviewee talking about his attempts during 2012-2013, when a small budget was provided by the SATBA said: “I tried hard to cultivate the school students, as the young and very dynamic generation. With the provided budget …during 2012-2013 we installed 950 rooftop solar systems. This was we thought the students see them every day, and ask their teachers about the technology and advantages, … and during the time it gets a common sense, they explain also to their parents at home, …. It slowly settles in their mind” Q9: 8. This shows that providing financial budget and supportive policies, can free a considerable potential among solar businesspeople and raise social acceptance of solar PV. Though, it is not always promised. An interviewee explained about the absence of political will and vision, mentioned: “We sent considerable number of letters to governmental organisations. They have been obliged to install solar PV from 2016. We thought it is necessary for at least the main decision makers in these organisations to gain the basic knowledge in solar energy field. In our letters, we asked to hold some workshops first for them, and then for the public society, in public places like mosques. Though, we received no positive answer and no follow-up at all. It is like there is no real will ….!” Q2:9.

In addition to environmental awareness, I find that solar businesspeople grow technical knowledge on solar PV among people. Solar PV is approached still as an innovation in Iran, and solar businesspeople are the main information desks for people. To get successful to sell their service and product, the solar business owners have no way except producing the minimum knowledge on solar PV. By exhibiting the solar system equipment, like solar panels, or mobile lighting solar packs in their showcases, or via advertising the solar system over billboards, websites, their Instagrams, and other social media they raise not only the curiosity among lay people but also provide considerable technical knowledge about solar system. I find the solar businesspeople motivated enough to provide consultation about the reliability and durability of those systems or designing better business models to the potential adopters. By giving consultations, they persuade the potential adopters, encourage greater investment, and not only raise the adoption possibility, but also hold the bad choice/decision decreasing the possibility of unsatisfaction and blowing the SPV image in long terms. I understand that their role is not only limited to public society, but also expands among other groups of stakeholders, as governmental institutions, and their managers as decision makers. Depending on their situation, they can be effective in small-large scale circles around them. They can sell a technically known device far easier than an unknown, still innovation-perceived tool. They should compensate the whole shortcomings of the media and its governors in environmental/technical awareness raising. I understand that in a low trust society, people have higher levels of trust to the private sector (except than the government), which raises the importance of this group and its functionality.

Third, on administrative side of Solar PV installation process; I find solar businesspeople familiarising people with not only existing tariffs for solar electricity, but also the paperwork needed beforehand specially in on-grid solar system installation. No need to stress, solar PV as an innovation in Iran is majorly unknown regarding the PPA and involved organsiations among the society. According to my interviews, the solar businesspeople do provide information on a wide range of issues from installation site assessment, allowances and permittance, to financing and incentives. Depending on their customers, weather as utility-scale solar power plant, or small scale (kw size) solar system on, or off-grid, or even agriculture solar water pumps, the businesswomen/men offer related administrative, organisational, and official information. I personally observed a utility-scale solar power plant potential investor referring to a solar business of my interview. The referred interviewee, in addition to technical information provision on the existing quality materials, to designing the site, …. offered helpful information on PPA details, and the involved organsiations to refer to, and the existing tariffs assessed.

Drive adaptive/innovative deployment of SPV.

I find solar businesspeople as innovation drivers via developing innovative system designs, in bringing solar PV deployment forward. Depending on each customer’s needs and situations, solar businesspeople design systems tailored to their needs. They do reduce the costs, and by developing new, efficient, and cost-effective systems, they make it better accessible to larger range of users. This is specially a meaningful role in a still niche market level of solar PV development. I find the respondents as very flexible with the specific functionality and potentials of their customers. According to my interviews, designing a solar system, the solar businesses investigate the needs, and make it fit to the context. An interviewee explained, “We consider a combination of factors when we design a solar system for our customers. In addition, we predict some possible changes. If (s)he is a farmer who uses solar water pumps, we consider the depth of their well, if (s)he wants solar system for his recreational residence in a village, we ask how often they travel there; if (s)he is a nomad who invest in solar system to access electricity in desert, we ask of their electrical appliances power, and so on …” Q4: 9. The same interviewee continued, “Powering a refrigerator with solar electricity, can significantly increase the final cost of solar system, which is a common request of our off-grid customers. It affects the inverter power, battery storage size, as well the panels. What we do is to offer a 24 Volt DC-powered refrigerator that can be matched to a 24-Volt battery using solar PV system” Q2: 5. I find this role specially important regarding the fast-rising price of the solar equipment in Iran. This adaptability does help solar businesspeople to compensate the solar PV adoption at a logical level, avoiding its rejection at all. I understand installing upgradable solar system as another factor of adaptability. According to my interviews, this is majorly the financial limitation that forces the adopters to ask for a low-capacity solar system. Either in this case, or any other reason, the solar businesses design an upgradable system with the possibility to increase the capacity as soon as an increment in power use, or provision of financial resources.

Diffusion facilitators

I find the solar businesspeople as facilitators of solar PV diffusion. This is mainly because of their extensive networking reaching outside their local system, with other groups of stakeholders, in combination with their other potentials (previously addressed under drivers and motivators). Being cosmopolite and via their good networking (guilds, and policymakers) they help to create more enabling environment for SPV development and even to join some people of the incumbent regime (as a mechanism of success to exit of the niche level- Kemp, Schot 1998 [

3]. A respondent explained about his source of great effect via his good networking with a governmental organisation’s CEO (in fossil-fuel field), that his innovation linked with his good networking:

“It is not only my profession but also my obsession. My house has been equipped with solar system since 2000. At that time, there was no familiarity with this technology at all. Mr. X, the CEO of the Y governmental organisation, with whom I had a great relationship, came to visit the solar system at my house. He was impressed and asked me for solar PV installation in all stations of Y organisation. They were the first municipality sites in Iran to be equipped with solar panels. After that, other governmental organisations in more provinces came and visited, and we went gradually to work in other provinces of Iran as well. I have installed power plants in more than 10 provinces for more than 10 governmental organisations”. Q4: 11. This shows that these solar PV niche actors, could get connected with members of the incumbent fossil fuel regime and got the source of a great affect. He facilitated the diffusion and expanded it even in more than 10 provinces in Iran.

5. Discussion

Drawing on a grounded theory approach [

38] and based on empirical findings of solar business owners in Iran, I was able to find that they are driven intrinsically and extrinsically toward developing solar PV deployment (via their business activity). Ecological (and energy) awareness, concerns moreover to prosocial (intergenerational) justice and their willingness to innovate, are driving the Iranian solar businesspeople intrinsically. Furthermore, socio-economic opportunity emanating from the untapped solar energy market in Iran, in addition to tackling the energy crisis (electricity and gas outages) are driving solar businesspeople extrinsically. On the other hand, they are selling something unknown, price-escalating, scarcely available in good quality, with un-supportive policies, that all leave solar energy market still in niche level. Interestingly, despite the whole obstacles (relying on their potentials and drivers) they are playing significant roles in bringing solar PV deployment forward. According to my findings, solar businesspeople are educating people (public society), driving innovative deployment of Solar PV, and in one word they are catalysts of solar PV diffusion. Generally, I identify considerable potential among the solar businesspeople in Iran to expedite the solar energy transition. Though the actualisation of this potential depends either on additional power provision, or better supportive policies from the national policymakers. These findings are relevant, while they provide novel understanding of an effective but majorly overlooked stakeholder group in transition to RE in the context of Iran as a developing country with fossil-based economy. In a centrally governed energy transition, with not sufficient political will and vision toward RE, the solar business owners can play critical role in bringing the solar PV deployment forward, due to their better updated attitude and prosocial motivations. The results out of this research should help first the national policy makers to gain a better understanding of solar energy market and the critical role of solar businesspeople in promoting the solar PV deployment. Second, these results can aid Iranian solar businesspeople to enhance their comprehension of market dynamics, and their pivotal contribution toward fostering solar PV deployment. Third, my outcomes can help the global efforts towards mitigating climate change and hastening the transition towards RE, regarding the highlighted social potentials in Iran despite the economic reliance and political vision on fossil fuels. Following this introduction, I discuss some key findings of this study and their implications.

Table 2. shows the list of empirical drivers, barriers, and roles to be played by solar businesspeople in Iran.

According to my analysis, doing business in solar energy field in Iran, is partially a pro-environmental behaviour of the solar business owners. Having environmental awareness and concerns in parallel with prosocial/intergenerational motivations encourage solar businesspeople toward solar energy development. However, attention to environmental issues, including the concept of environmentalism and modern environmental movements originated in Western Countries, and intensively dealt with (academically) theoretical/empirically by European researchers [

48], [

49], [

50], [

51], [

52]. Admitting my finding on pro-environmental behaviour in Iran, Jahangir Karami et al. conducting a systematic review and meta-analysis, to investigate the pro-environmental behaviour of Iranians (1998-2018) reported that the Iranian citizens have about the average of the global mean index of environmental performance [

53]. In contrary, Monavarian et. al. [

54] introduced RE development drivers in Iran as completely different with other developed countries. Omitting any attention to environment, they prioritised the global energy transition standards and commitments as well as developing new enterprises, as the main RE development drivers. Prioritised environmental issues, even among partial society in Iran as a socio-ecological value, can open the windows of opportunity for a bottom-up transition to RE, and second, promises higher social acceptance as a MUST in any major transition.

The low knowledge and lack of awareness among the public society (solar PV customers) as a key barrier revealed in this study has been frequently mentioned in diverse studies generally [

55] and specifically as a characteristic of developing countries [

56], [

57], [

58], [

59], fossil fuel rich countries [

60], [

61], including Iran [

29]. [

62]. Based on my interviews, the low knowledge of solar PV is not only limited to the public society (lay people), but also contains local and regional governmental institutions. Raising awareness including the educating plans and programs is mainly the key role of governments but has been absent of Iran government agenda. Environmental and RE knowledge needs to be given more space in media, including TV, radio, billboards, and even the physical and online newspapers. … According to my findings, solar business owners are playing the most pivotal role in this field. Educating public society about solar energy (as a type of RE) and its socio-economic benefits, helps these businesses to facilitate the diffusion process [

63]. Higher degrees power [

64] provision for this group of stakeholders: solar businesspeople, can impact their ability to influence promotion of solar PV deployment.

Lack of supportive policies to promote solar PV deployment, and favourable regulatory framework revealed in this research as major barriers, have been disclosed in other studies as well, although they have diverse implications here. Supportive policy frameworks encouraging the investment in RE, coherent policies [

65], [

66], [

67] levelling the playing field for fossil and RE to compete [

68], supporting R&D, and innovation [

15], raising public knowledge and awareness to promote their acceptance and participation, incentivising policies [

4], [

69], [

70] have been some of the most frequent forms of favourable regulatory frameworks. However, depending on the political and social context of countries, the impact degree of favourable regulatory frameworks and their absence can differ considerably. Higher levels of democracy can navigate the energy transition better via leveraging public opinion, rallying citizen activism, and other effective measures that provide more opportunities for diverse stakeholders to participate in decision making and bringing the energy transition forward. Iran as a less democratic (though mixed system of government) can be more vulnerable to this absence of favourable regulatory framework. As with the lack of supportive policy incentives from the top, the potentials and drivers among the solar businesspeople can be limited majorly. With the lack of political will and vision [

54], [

71], [

72] toward energy transition, and the power imbalance among diverse stakeholder groups affecting transition governance, any potential and opportunity from the drivers among businesspeople to the untapped solar energy market in Iran, as well tackling energy imbalance in Iran, would be left fruitless.

Finally, the cheap (highly subsidised)

electricity in Iran, that was frequently mentioned in interviews as a root reason for minor development of solar PV, low social acceptance in Iran. this is also mentioned in some studies, and in the field of levelling the playing field for RE [

68]. Though in this study it reveals partial misunderstanding of the solar market by the businesspeople that needs to be considered. The cheap price of conventional electricity can be a barrier, when higher-price solar electricity is also available as an alternative (unable to compete with the cheap conventional electricity) while it is not the case in Iran. In Iran, according to standards by the EDC for on-grid rooftop solar systems one has either 100% conventional electricity (on-grid connection), or 100% solar electricity (off-grid). Therefore, a simultaneous presence of both options would be omitted. This means that the whole produced solar electricity is inserted into the power network for which the adopter will receive FITs. Having no “prosumer” in Iran, (produce and consuming solar electricity), the lack of a direct competition between conventional electricity and solar PV does mitigate the impact of highly subsidised electricity on solar PV adoption in Iran majorly, which is hidden of majority of solar businesspeople in Iran. However, the highly subsidised gas, or oil, or gasoil can be a barrier, which is the case in off-grid systems. This is because of diesel generators that burn directly diesel and would be better substituted with solar system in regions like Sistan in which the prices are high to control the smuggling from the geographical barrier to other neighbouring countries. Other case, happens among the remote area off-grid adopters for which a new conventional power access does persuade them to sell their solar systems and switch easily to conventional electricity that has mainly technical reasons (regarding efficiency and stability [

73]). Misunderstanding of the market, by solar businesses; and this could shape some less efficient mechanisms to extend/accelerate the diffusion!!!

Moreover, the positive role of energy imbalance in Iran, that has shaped a positive attitude among solar businesspeople and drive them toward; is another issue of a non-sufficient understanding. Going toward RE, is only valuable, when it does narrow down the uptake of fossil resources, and not to add over the top of voracious energy demand, increasing energy intensity, and human made faults in managing energy resources.

Limitations

It is acknowledged that the far distance (between Germany and Iran), plus the financial limitations, did force online interviews in the second round of data gathering. This round of interviews, despite opening new windows of opportunity toward the research objectives, did have the limitations of no physical (in person) contacts with the interviewees, and to lose some gestural and apparent connections. Moreover, this case study can bring better extensive results with raising the number of interviews and case studies in Iran (covering the whole provinces).