Introduction

Body-esteem (BE) reflects the self-evaluations of one's body or appearance (Mendelson et al., 2001). Poor body image concerns remain a global phenomenon among adolescent females (Juli, 2017). Body image dissatisfaction has been evidenced in half, to three-quarters of adolescent females (Miranda et al., 2021). This finding is consistent with an earlier one from an international cross-sectional survey of adolescent females from 24 Western countries including Europe, Canada & USA (Al Sabbath, et al., 2009) which revealed up to 60% were dissatisfied with their physical appearance. It is widely acknowledged that poor body-esteem during adolescence is correlated with a range of negative outcomes including poor mental health, low self-esteem (Wichstrøm & von Soest, 2016), high anxiety (Cruz-Sáez et al., 2015), and poor quality of life (Haraldstad et al., 2011). Further, low body-esteem during adolescence can continue into early adulthood (Bucchianeri et al.,2013).

Therefore, low body-image among female adolescents is a worldwide issue and identification of low-cost, easy to implement and scalable interventions to enhance body-image are worth identifying and implementing. Identifying ways to develop a healthy body image during the adolescent period for females remains a challenge (Frisén et al., 2015; Spreckelsen, Glashouwe, Bennik, Tylka, 2012, Wessel & de Jong, 2018; Wojtowicz & Von Ranson, 2012).

As attending school is compulsory for many countries worldwide, schools provide an environment where female adolescent body-esteem attitudes are shaped (Scully et al., 2020). One aspect of school life where body-esteem can be challenge is Physical Education, where students are often made to wear a PE kit to comply with school rules. Physical education can be a double edge sword; on one hand, it is associated with positive effects and enhanced self-esteem, but on the other, it is associated with low body image. It is argued that PE kit, that is, the official kit to be worn as part of school rules present barriers to physical activity in adolescent females (Jang & Jeon, 2018; Standiford, 2013). If wearing a PE kit associates with negative body-esteem, this will have negative effects on attitudes towards doing physical activity. Arguably, opportunities for learning to enjoy physical activity are blighted as the PE environment is often a context that merely produces negative body image experiences (Evans, 2006).

Wang et al. (2019) contends, situational or contextual influences are suggested to be a potent force that influences attitudes towards one’s body (Cash, 2012). Cash (2012) argues that there are multiple and interacting factors of behaviours that can be used to develop interventions. Contextual change can invoke negative emotions, and body-esteem can be impacted by numerous factors (Zanon et al., 2016) including social scrutiny (e.g., other people evaluating your body), social comparisons (e.g., comparing your shape and size with others), body exposure (e.g., undressing in a PE changing room), being physically active (e.g., participating in school sport) and type of clothing worn (e.g., PE kit) (Cash, 2002).

In terms of interventions to support body esteem, evidence suggests that school-based interventions to improve girls’ participation have been inconsistent with varied effects (Duncan et al., 2009; Metcalf et al., 2012). To highlight depth of the challenge, a meta-analysis of 62 body image interventions highlighted that only small-to-moderate improvements in female body image (Alleva et al., 2015).

The primary aim of the present study was to investigate the influence of an intervention in which participants are offered a free choice of kit to wear for PE. Our comparative data was to investigate the stability of body-esteem when participants where the same clothes in the same context. By investigating the effectiveness of this simple intervention, we seek to provide evidence for an easy-to-use, cost effective and scalable intervention. By investigating the relative stability of the body-esteem, we provide an appropriate comparison condition. A control group was not possible because of contamination effects within a school. By investigating the test-retest stability of body-esteem we interrogate the psychometric properties of the scale we used (Kember & Leung, 2008; Thompson, 2004). Assessing the stability and the susceptibility of individual items within a measure to random change is necessary (Nevill et al., 2015). Nevil et al. (2015) demonstrated that subjective constructs assessed via self-report are prone to random error and encouraged researchers to establish the relative stability of the scale being used. If interventions are to be shown to be effective, any differences in a test-retest design need to be understood. Therefore, evaluating the stability of any assessment tool, through observing minimal measurement error in a test-retest assessment, is vital to validating psychometric tools (Lane et al., 2005) and establishing the integrity of research (Patton, 2001).

To address this point, the present study will also control for the effect of context on test administration and outcomes through administering the scale in two contexts; the changing rooms, and the school hall and the overall aims of the present study were:

(i)To examine the test-retest stability of the Body Esteem Scale (Confalonieri et al., 2008). And if the scale was found to have sufficient stability, then it would be possible to scrutinize the effect of context. If, of course, the scale was unstable, then it would not be possible to have confidence in changes in body-esteem scores by context as such differences could be attributed to the poor psychometric properties of the scale.

(ii)To assess the effect of an intervention where students were given a choice of clothes to wear for PE. We hypothesized that the intervention would be associated with improved body-esteem. To contrast this result and show the effect of context, we examined test-retest differences of body-esteem when participants complete the scale in a classroom setting. We hypothesized that body-esteem would be stable.

Methods

Design

An experimental A-B-A within-subjects 2x2 design was used. The independent variables were context on two levels (PE kit or Uniform) and time on two levels (baseline and post- intervention). Dependent variables were the three subscales of the body esteem scale; being BE-appearance, BE-weight, and BE-attribution (Confalonieri et al., 2008). All participants took part in the intervention and no control group was needed as participants acted as their own control. Historically, body image investigations have focussed on young adults, often failing to capitalise on opportunities to investigate body image across adolescent populations (Mellor et al., 2013). Therefore, one suggestion to enhance positive body image remains with opportunities for prevention of poor body image and intervention in schools (Fazel et al., 2014).

Participants

Participants were selected from a school in South Birmingham in the Midlands (UK).

Participants were adolescent females (n = 110) at Key Stage 4. This comprised two different year groups; Year 10 (14-15 years) and Year 11 (15-16 years) (Mage =14.9; SDage = 0.68). The socio- economic demographic revealed a free school meals allocation of 53%. This is higher than the UK national average of 22.5% (DfE, 2022). The schools’ socio-economic demographics outline that White British pupils represent approximately 62.2% of the school population and BME populations approximately 37.8%.

Measure

To be able to capture adolescent female perceptions and experiences relating to body-esteem the 14-item Body Esteem Scale (BES; Confalonieri et al., 2008) was selected. It is an adapted version of the Body Esteem Scale for Adolescents and Adults (Mendelson et al., 2001). It is a multifaceted measure with subscales that are conceptually divergent. The measure differentiates an individual’s body esteem judgements concerning ‘Appearance’ (general feelings about appearance), ‘Weight’ (weight satisfaction), and ‘Attribution’ (evaluations attributed to others about one’s body and appearance), thus enabling the measurement of specific dimensions of body-esteem, opposed to that of a single construct. Within the construct of the measure, a six-item appearance subscale captures overall satisfaction with appearance, an example item is “I wish I looked like someone else.” The four-item weight subscale denotes satisfaction with one’s weight, for example, “Weighing myself depresses me” and the four-item attribution subscale summarises evaluations attributed to others about one’s body and appearance. For example, “Other people consider me good looking.”

The Likert-scale items range from 1 (never) to 5 (always). After reverse scoring the appropriate items, participants’ responses are averaged across items. Higher scores are indicative of a more positive weight-esteem. The measure is reported to provide good reliability and internal validity with a three-factor solution: attribution (the evaluations of one’s own body and appearance attributed to others), weight (weight satisfaction), and appearance (an overall feeling about one’s appearance). The three subscales have adequate reliability (appearance: alpha = .76; attribution: alpha = .68; weight: alpha = .84) and this measure has been validated for use among 11–16-year-olds (n = 674; M = 13.33, SD = 2.1) (Confalonieri et al., 2008).

Procedure

Ethical approval was obtained from the University of Wolverhampton ethics committee. Parental/carer consent was sought for participants recruited from a secondary school in the Midlands (UK). Data were gathered in one secondary school in the West Midlands, UK. A single school was used as the school could be a possible moderator.

At baseline, the 14-item BES (Confalonieri et al., 2008) was completed in two contexts (uniform in a school hall and PE kit in a PE changing room) within one week. No time limit was provided. Participants first completed the measure in the school hall, where they wore the standard school uniform (school jumper, trousers and shirt and tie). The PE context was in changing rooms wearing PE kit (PE top, shorts, tracksuit bottoms or skorts). This procedure was repeated one week later for the purpose of calculating test-retest statistics at baseline.

At Intervention stage, for a period of two weeks, participants could choose to wear; (1) a plain (with no logo) base layer long sleeve top (black, white, navy blue or grey only), under their PE top (2) Plain (with no logo) black full-length leggings (opposed to shorts or a skort) (3) their school jumper on top of their PE top. School jumpers were part of the school uniform, and not part of the school PE kit. Wearing a standard school jumper would provide a level of consistency, and thus prevent participants from wearing different sporting logos and brands, for which it might be suggested that more expensive branded clothing might have influenced outcomes by facilitating increases in body-esteem, opposed to the actual clothing items. During their standard PE lessons, the lesson content remained the same as no changes were made to the curriculum, as the activity had no bearing on the intervention. The intervention focus was entirely on the opportunity to choose from three additional clothing options or choose to wear their usual clothing.

Post intervention, the BES was administered, again both in the uniform context, and in the PE context. Both administrations of the questionnaire took place within a one-week period and procedures were repeated a week later, again to allow for test-retest statistics to be calculated from follow up data. In total the measure was repeated eight times. Whilst all 110 participants were given choice over PE kit, 90 opted to wear an additional item of a base layer, leggings or a school jumper, with 20 participants opting to wear the standard PE kit.

Data Analysis

Data were cleaned and checked for errors. Allowances were made for missing data within the boundary that only one missing item per subscale would be accepted otherwise data would be removed from the study. Missing values was within an acceptable range (2.4%) according to the guidance of Bennett (2001). All mean scores were calculated. Descriptive statistics were calculated for the three subscales across the two conditions (PE kit and school uniform). To replicate the stability of the BES overtime and within context, the BES was administered twice at each time point and in each context and correlations and t-tests were used to assess stability of the measure within context.

To assess the effect of an intervention on BES scores, baseline scores on the BES were compared with post-intervention follow up scores using a multivariate analysis of variance (MANOVA). To assess whether the context in which BES is measured (PE kit in PE changing room or school hall in school uniform) has any influence on the observed effect of the intervention, measures were taken in both contexts at both time points context was entered as an IV within the same MANOVA.

Results

Baseline: Body Image is Stable in Test-Retest Conditions

Results to investigate the relative stability of the BES indicate that all test-retest correlations (

n = 12) were significant (r= .96-.99, p<.001), and none of the t-tests demonstrated a significant difference between test-retest scores (see

Table 1). Therefore, results support the hypothesis that BES is provides reliable measures.

Intervention Effects

Table 1 presents the means at baseline and post intervention, across contexts and subscales and

Figure 1,

Figure 2,

Figure 3 and

Figure 4 depict differences graphically Dependent variables were the three subscales of the body esteem scale; being BE-Appearance (“feelings about one’s general appearance”), BE-Weight (“feelings about one’s weight”), and BE-Attribution (“evaluations attributed to others about one’s body and appearance”). The highest mean body-esteem scores were found for post intervention data when wearing PE kit across for all three subscales (M = 14.46, SD = 0.55) opposed to uniform (M = 13.44, SD = 2.65). This shows the overall highest means (and therefore greatest) body-esteem scores were identified within the PE clothing intervention group when compared across all conditions: time, contexts, and as combined subscales. All the subscales of body-esteem differed between those wearing PE kit and those in uniform.

Across all subscales, the lowest (and therefore poorest BE scores) were consistently reported as BE-Attribution; despite time (baseline or Post Intervention) or context (PE kit or uniform). With the poorest BE-Attribution scores reported during baseline testing: (M = 11.10, SD = 1.89) and retest phases: (M = 11.09, SD = 1.95). Regardless of time or context, the greatest overall appearance concern for adolescent females was not their own perceptions of their appearance, neither their weight, but their perceptions of how other people see them. Across the subscales, the greatest increases (and therefore largest changes) were seen within BE-Appearance in PE kit during baseline retest (M- 15.92, SD=2.95); BE-Attribution (t=-0.38, p < 0.71) to Post Intervention retest (M- 17.93, SD=3.06); BE-Attribution (t=-0.96, p < 0.34) (see

Table 1). Therefore, results show that wearing PE clothing is a moderator of body-esteem.

Multivariate Analysis

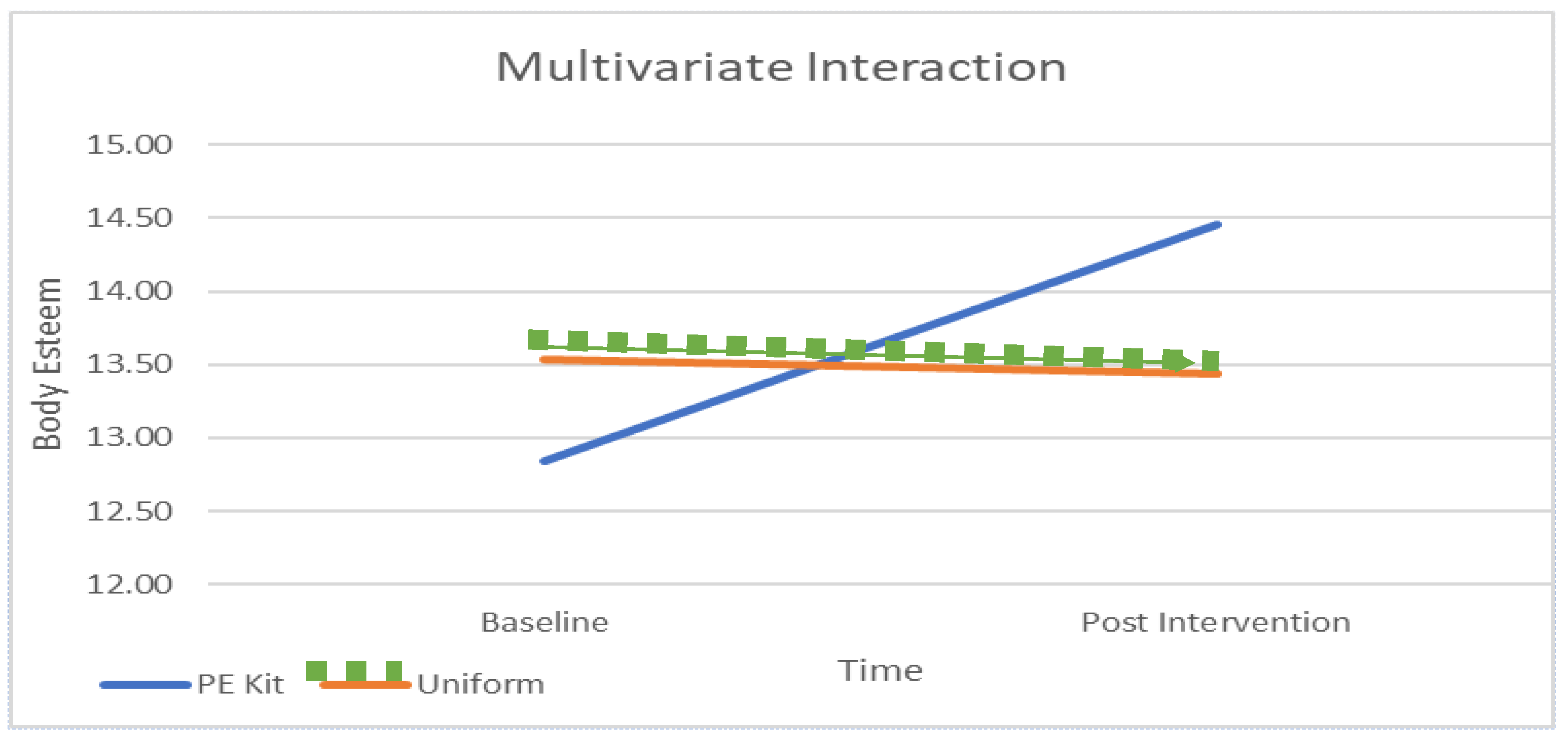

The MANOVA tested the effect of time (pre-post intervention) and context (PE kit and school uniform) on the three subscales measuring body esteem. Results are depicted graphically in

Figure 1,

Figure 2,

Figure 3 and

Figure 4. As

Figure 1 illustrates, results show a significant interaction for changes in body esteem by context (PE v classroom) and time (pre-post) (Wilks Lambda = .40, F (3, 107) = 54.236, p<.01, partial η2 =.60). As shown in

Figure 1, interaction show the positive effects of the intervention with an increase in body esteem, whereas body-esteem remain stable in the classroom context. The effect size for the interaction was large (Murphy & Myors, 2004).

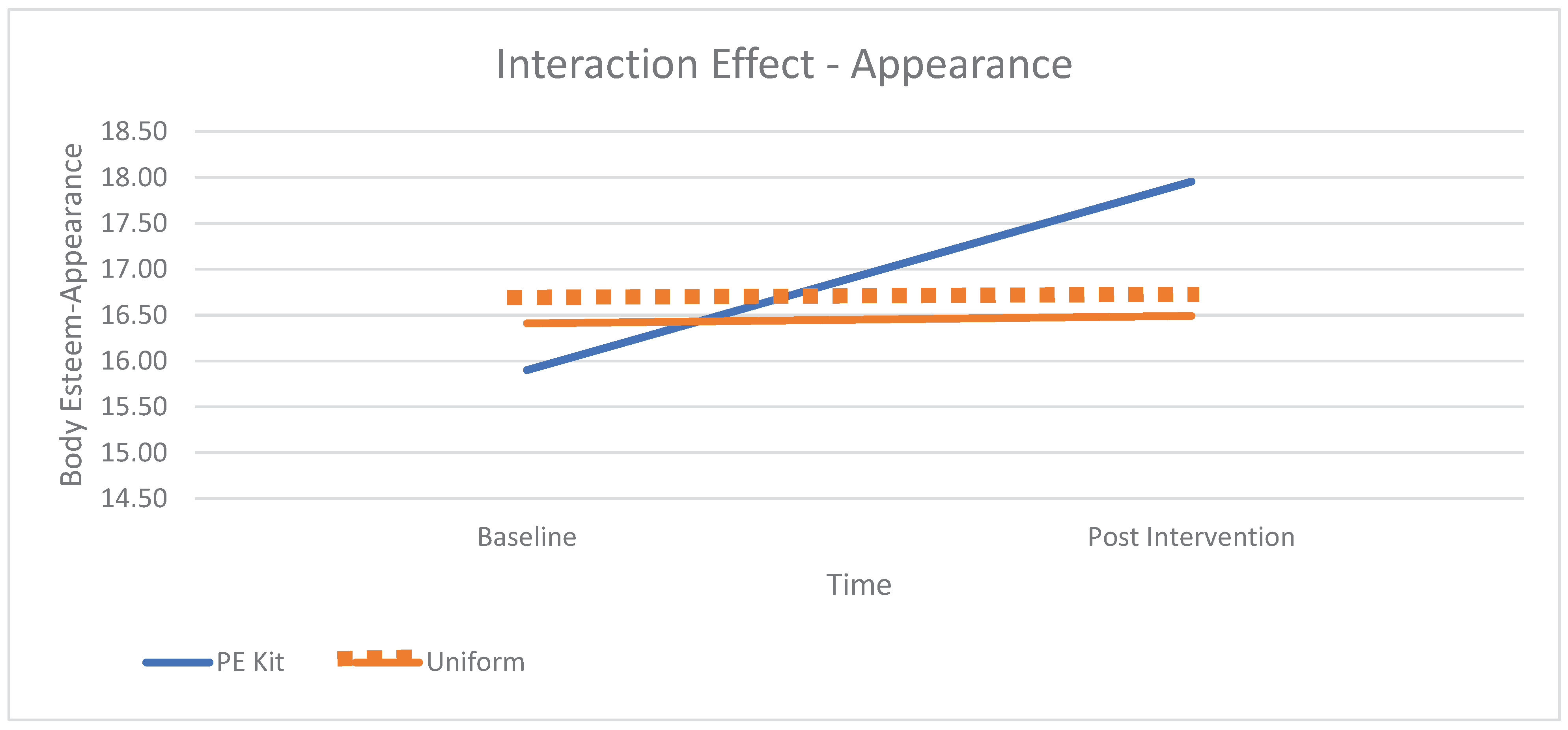

A significant interaction was found for all subscales (Appearance: F (1, 106) = 73.35, p<.01, partial η2 = .40, see

Figure 2, Weight: F (1, 106) = 51.24, p<.01, partial η2 = .32, see

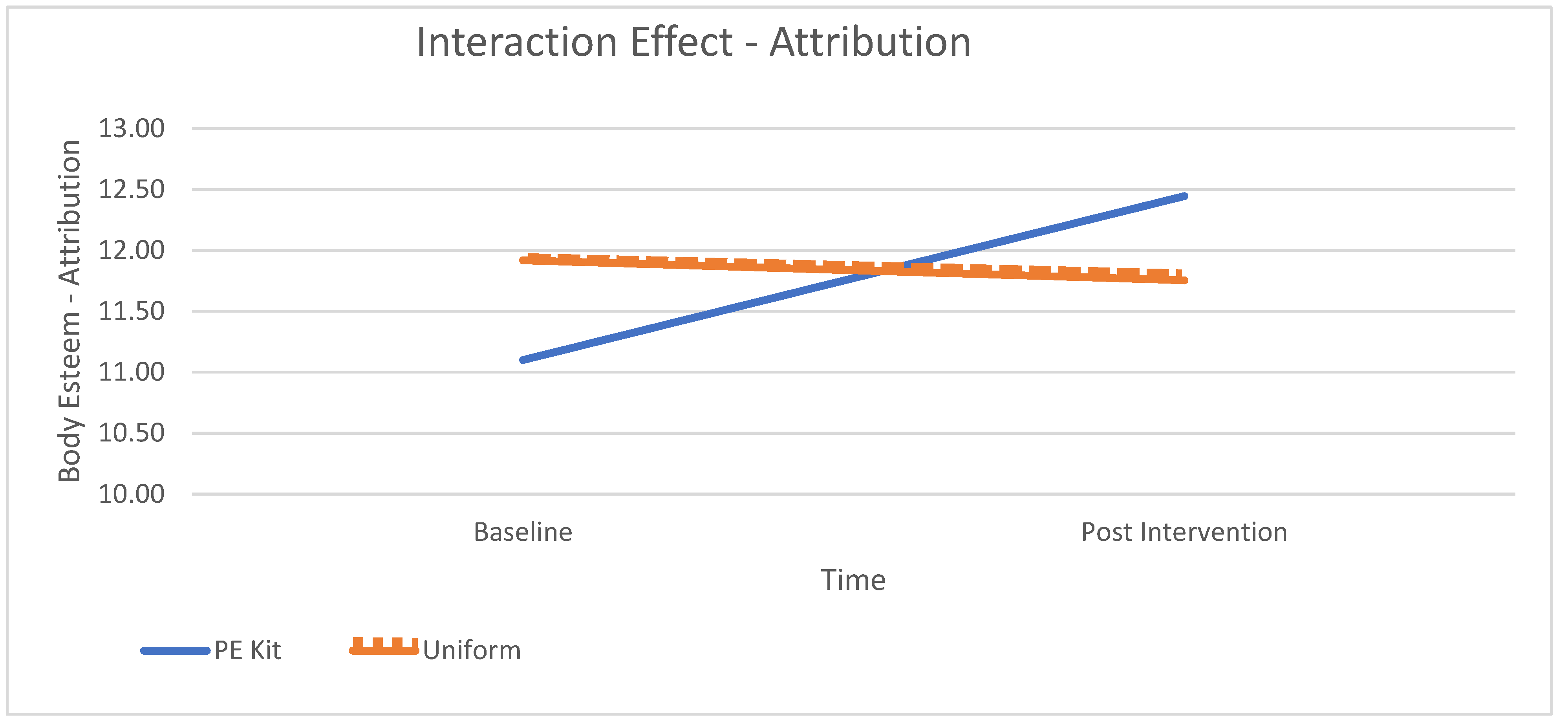

Figure 3; Attribution: F (1, 106) = 63.31, p<.01, partial η2 = .37, see

Figure 4). As observed in

Figure 1,

Figure 2 and

Figure 3, the effect was more pronounced for the weight and attribution subscales, where a decrease in scores was observed in the Uniform context, whereas an increase was observed in the PE context.

Results revealed a significant main effect for context (PE v Classroom) (Wilks Lambda = .05, F (3, 107) =. 35.180, p<.01, partial η2 =.38). As Table 3 shows, average of all scales across all time points shows a slightly higher score for PE kit than for uniform, a finding influenced by the effects of the intervention. Univariate analyses demonstrated a significant effect was observed on all three subscales (Appearance: F (1, 107) = 66.01, p<.01, partial η2 =.38; Weight: F (1, 107) = 34.99, p<.01, partial η2 = .24; Attribution: F (1, 107) = 37.61, p<.01, partial η2 =.26).

The main effect of time was not significant (Wilks Lambda =.94, F (3, 107) = 2.172, p=.1, partial η2 =.06). In univariate analysis, this pattern was found for all subscales (Appearance: F (1, 107) = 5.96, p=.02, partial η2 = .05; Weight: F (1, 107) = .09, p =.077, partial η2 = 0; Attribution: F (1, 107) = .07, p =.80, partial η2 = 0).

Taken together these findings indicate that the intervention had a significant and positive effect on body esteem, however the increase in body esteem was only detected where measures were taken in the PE context.

Discussion

The present study developed and tested a simple to implement and scalable intervention designed to raise body-esteem in adolescent females in PE. We also tested the relative stability of body-esteem scores and the reliability of the scale. We hypothesized that wearing a PE kit would reduce body-esteem in comparison to wearing a school uniform (Jang & Jeon, 2018; Standiford, 2013) and results of the present study support this assumption. We also found that body-esteem was stable when contextual factors, place and clothes worn were stable. Previous research has found that although physical activity has the potential to improve well-being include body esteem, such effects are not consistently found (Eime et al., 2013) and further, wearing a PE kit can have negative effects (Duncan et al., 2009; Metcalf et al., 2012). We hypothesized that offering students a choice would reduce these negative effects. Results support this hypothesis and findings show that offering students a choice of what to wear for PE offsets the negative effects found when wearing PE kit.

We argue that this finding has considerable practical value as it is an intervention that is easy to implement and does not require complex behavioural change from participants (Michie et al., 2011). Michie et al. (2011) argued that for interventions to work they need to offer participants the opportunity to try the intervention, and clearly, scheduled PE classes offer this opportunity. Michie et al. (2011) argue that participants need to be motivated to do the intervention, that is be active in the treatment. By offering students choice, this increases autonomy, and this should increase motivation. Thirdly, Michie et al. (2011) argued that participants need to be competent and able to do the behaviours required. In this instance, this requires participants to own clothes they are happy to wear in a PE class and so is likely to be achievable by most. This creates a simple to implement intervention. An observation of many interventions to enhance body-esteem indicates that they are complex, require a great deal of activity on behalf of the participant, and can be expensive (Alleva et al., 2015). Many interventions are simply not sustainable on a wider scale, and difficult to effectively re-create and follow up post intervention (Love et al., 2019). Notable additional challenges also are evident for schools in the form of financial restraints, limited staffing resources, and a lack of opportunities for intervention (Milat et al., 2013, 2014). Interventions which are complex are often difficult to implement (Michie et al., 2011) and therefore, many good ideas in theory, fail to work in practice.

In line with our findings, the PE changing room is recognised as a context that may prompt and heightens concerns related to physical appearance (Allender et al., 2006) where negative emotions, and comparisons magnify negative body esteem (Tiggemann, 2015). Also supported by our study outcomes is the contention that social comparisons increase feelings of inferiority and self-consciousness (Fanon, 1952). Our results show body esteem was lower when wearing a PE kit in comparison to wearing school uniform, that is, it deteriorates. In such contexts, it can be suggested that body image issues can be triggered as self-perceptions are fragile and can be manipulated (Liechty et al., 2015) as adolescents internalise body appearance ideals (Smolak, 2009). Such experiences are consequential, as Elliott and Hoyle (2014) advocate that wearing PE kit has the potential to increase feelings of self-consciousness, and lower body-esteem, particularly if poorly fitted (Allender et al., 2006). Tight fitness clothing has the capacity to increase body image concerns (Slater & Tiggemann, 2011), notably clothing and body satisfaction are inexorably linked (Tiggemann & Lacey, 2009). Further, impractical, poorly designed PE kit can limit and restrict participation in physical activities (Norrish et al., 2012). Body conscious females continue to report appearance concerns are related to PE kits that reveal body shape (Velija & Kumar, 2009). Yet a one style fits all approach continues to desecrate opportunities for positive adolescent female PE experiences. For the adolescent female to feel more body confident when physically active, a positive body image (regardless of size or shape), is a driving factor in facilitating improvements in attitudes towards physical activity (Yan et al., 2015). In support of this, adolescence provides an opportune time to intervene due to the most dramatic decreases in female body-esteem (early and mid-adolescence) for both appearance and weight-esteem (Abbott et al., 2012; Holsen et al., 2012). Our study outcomes imply that small, but significant steps can be taken to empower girls through PE kit choice which increases comfort during lessons (Velija & Kumar, 2009) and enhances positivity (Boyes et al., 2007).

A few basic manipulations to PE kit would strengthen and reduce negative perceptions and experiences within the context of physical education, i.e., reducing perceived physical differences of body size or shape (Jachyra, 2016). Allowing choice of PE kit may present protective mechanisms facilitating healthier positive body recognition and increased physical fitness in female adolescents (Mahlo & Tiggemann, 2016). Central to the intervention design was the ideology that suggests that when girls are motivated by choice and autonomy, sustained physical activity behaviours can increase (Ntoumanis et al., 2021).

Our findings indicate that clothing choice, as an intervention can be influential as it offers a more promising area of research therefore could be hypothesised that improvements in PE clothing could lead to an enhanced positive experience within exercise and sport. We would therefore argue that what is needed is not highly sophisticated or innovative interventions that will prove successful in engaging girls through greater satisfaction and experiences within physical activity; rather simple, widely scalable, and effective interventions (Norrish et al., 2012; Watson et al., 2015).

In seeking ways to improve an adolescent girls’ PE experience, previous assumptions were made that suggested girls’ negative attitudes were the overriding factor for their disengagement in PE activities, with limited investigations into why (Biddle et al. 2005). For the adolescent female, the benefits of being physically active are vast and associated with a wide range of positive attributes of body image (Gomez-Baya et al., 2019). Such benefits include increased body appreciation (Halliwell et al., 2019), enhanced appearance satisfaction (Ariel-Donges, Gordon, & Perri, 2019), and improved self-concept (Beasley & Garn, 2013). Yet despite the plethora of benefits to body image, negative body image continues to be an obstacle to physical activity participation (Sabiston et al., 2019), as does engagement in girls PE lessons (Croston & Hills, 2017).

A second key finding from the present study is on the relative stability of the body-esteem concept and the BES scale (Confalonieri et al., 2008; Mendelson et al., 2001). Results of the present study support its test-retest stability. This is particularly important as results show that body-esteem as a construct varies in intensity between different contexts. We suggest that demonstration of test-retest stability adds considerably to the literature as it provides evidence that the scale can be used to test the effects of interventions, and that changes over time are less likely to be due to measurement error (Nevil et al., 2015). Our study demonstrated that clothing has a significant effect on adolescent female body-esteem. In comparison, being able to choose PE kit had the effect of improving female body-esteem opposed to wearing standard school PE kit. Reporting body image when wearing school uniform was relatively stable. Contextual difference may have been evidenced through changes to both the environment, and clothing facilitated increases in negative body image. If we were to implement an intervention in the PE context, but only take the measures in the school hall, then no effect would have been observed.

Strengths of this Research

Having captured adolescent girl’s experiences of PE clothing and investigated the implications of contextual changes, these are promising findings. The experience of wearing PE clothing should not be detrimental to an adolescent females’ body-esteem. Therefore, we can present an effective intervention that could be implemented across schools nationally. In striving to meet this challenge, it was necessary to consider the challenges that school practitioners face, to propose an intervention that could be presented as plausible. As such, this study may have far-reaching consequences for body-esteem research in schools.

This intervention provides preliminary evidence in a limited research area, that through the suggested clothing manipulations our body-esteem intervention can integrated with confidence into all PE programmes. presents minimum disruption to the PE curriculum, does not require specialist training or intervention specialists, can be administered whether facilities are limited or not, can be actioned regardless of constraints on a school timetable, can be implemented regardless of a school financial budgets, allows for stake holders that include student voice, parents and carers, teaching staff, senior leaders and school governors to be part of the kit expansion options, recognizes the DFE, 2021 (Cost of School Uniform) statutory guidance which requires schools to make uniforms more affordable, and most importantly can be presented as an intervention that is inclusive of not only specific populations or year groups, but for every female adolescent in the UK.

Limitations and Suggestions for Further Research

Although this intervention study is unique in its approach to identifying how female body- esteem can be influenced through PE clothing, there are limitations that must be accounted for when interpreting these results. Firstly, further research is needed to investigate the impact of body-esteem interventions across younger adolescent female ages, as study participants were Key Stage 4 pupils only (year 10 and 11). Secondly, data collection was based on a self-reporting measure, and qualitative research might provide a more extensive and in-depth analysis within this field. Thirdly, comparisons were done through repeat measures and not with a control group wearing exact clothing, and this may be seen as a limitation; however, this intervention was not exclusively about clothing and context. It was about the freedom to choose.

As these outcomes were recorded over a brief period of time and what would be needed is longitudinal post intervention follow up over a 3, 6 and 12 months to investigate the sustainability of the increases in body-esteem over longer periods of time.

Conclusions

The study outcomes have captured adolescent girl’s appearance experiences of PE clothing and body-esteem. This research makes a significant contribution towards exploring the impact of contextual changes on body-esteem through adolescent female perceptions and providing a basic way for schools to reinforce healthy body-esteem within the context of PE. As such, these exciting results have important ramifications for PE practitioners striving to positively improve female adolescent body esteem experiences, through albeit minor adaptations. Our findings not only expose how contextual differences can impact body-esteem but why extending the range of particular PE clothing items can improve this problematic issue. In addition, these favourable changes can be implemented with speed and delivered at scale within schools across the country, and these adjustments can be implemented in a sustainable manner which makes this a major strength of this intervention. Effective body-esteem interventions are required to improve and impact the female adolescent physical education experience, and indeed the development and efficacy of this intervention is promising.

Conflicts of Interest

None

References

- Abbott, B. D., Barber, B. L., & Dziurawiec, S. (2012). What difference can a year make? Changes in functional and aesthetic body satisfaction among male and female adolescents over a year. Australian Psychologist, 47(4), 224-231. [CrossRef]

- Alleva, J. M., Tylka, T. L., & Kroon Van Diest, A. M. (2017). The Functionality Appreciation Scale (FAS): Development and psychometric evaluation in U.S. community women and men. Body Image, 23, 28-44. [CrossRef]

- Allender, S., G. Cowburn, & Foster, C. (2006). Understanding participation in sport and physical activity among children and adults: A review of qualitative studies. Health Education Research, 21(6), 826-835. [CrossRef]

- Bennett, D. A. (2001). How can I deal with missing data in my study? Australian and New Zealand journal of public health, 25(5), 464-469.

-

Body Image Survey Results (2020): House of Commons Women and Equalities Committee. Retrieved through https://committees.parliament.uk/publications/2691/documents/26657/default/.

- Boyes, A. D., Fletcher, G. J., & Latner, J. D. (2007). Male and female body image and dieting in the context of intimate relationships. Journal of Family Psychology, 21(4), 764.

- Biddle, S. J. H., S. H. Whitehead, T. M. O’Donovan, & M. E. Nevill. (2005). Correlates of Participation in Physical Activity for Adolescent Girls: A Systematic Literature Review and Update. Journal of Physical Activity and Health, 2(4), 423-434.

- Bucchianeri, M. M., Arikian, A. J., Hannan, P. J., Eisenberg, M. E., & Neumark-Sztainer, D. (2013). Body dissatisfaction from adolescence to young adulthood: Findings from a 10-year longitudinal study. Body image, 10(1), 1-7. [CrossRef]

- Cash, T. F., & Pruzinsky, T. (2002). A handbook of theory, research, and clinical practice. New York: Guilford Press.

- Cash, T.F. (2012). Cognitive-behavioral perspectives on body image. In T.F Cash (Ed.), Encyclopedia of Body Image and Human Appearance (pp. 334-342). London, UK, and San Diego, CA: Academic Press (Elsevier).

- Confalonieri, E., Gatti, E., Ionio, C., & Traficante, D. (2008). Body Esteem Scale: A Validation on Italian Adolescents. Psychometrics: Methodology in Applied Psychology, 15(3), 153-165.

- Croston, A., & Hills, L. A. (2017). The challenges of widening ‘legitimate’ understandings of ability within physical education. Sport, Education and Society, 22(5), 618–634. [CrossRef]

- Cruz-Sáez, S., Pascual, A., Salaberria, K., & Echeburúa, E. (2015). Normal-weight and overweight female adolescents with and without extreme weight-control behaviours: Emotional distress and body image concerns. Journal of Health Psychology, 20(6), 730-740. [CrossRef]

- Department for Education. (2019): Schools, pupils and their characteristics: England. Retrieved from https://explore-education-statistics.service.gov.uk/find-statistics/school-pupils-and-their-characteristics/2019-20.

- Department for Education (2021): Principles behind Ofsted’s research reviews and subject reports. Retrieved from https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/principles-behind-ofsteds-research- reviews-and-subject-reports.

- Department for Education (2022): Schools, pupils and their characteristics. Retrieved from https://explore-education-statistics.service.gov.uk/find-statistics/school-pupils-and-their-characteristics.

- Duncan, M. J., Al-Nakeeb, Y., & Nevill, A. M. (2009). Effects of a 6-week circuit training intervention on body esteem and body mass index in British primary school children. Body Image, 6(3), 216-220. [CrossRef]

- Elliott, D., & Hoyle, K. (2014). An examination of barriers to physical education for Christian and Muslim girls attending comprehensive secondary schools in the UK. European Physical Education Review, 20(3), 349-366. [CrossRef]

- Eime, R. M., Young, J. A., Harvey, J. T., Charity, M. J., & Payne, W. R. (2013). A systematic review of the psychological and social benefits of participation in sport for children and adolescents: Informing development of a conceptual model of health through sport. International journal of behavioral nutrition and physical activity, 10(1), 1-21. [CrossRef]

- Evans, B. (2006). ‘I’d feel ashamed’: Girls' bodies and sports participation. Gender, Place and Culture 13(5): 547–561. [CrossRef]

- Fanon, F. 1952 (2008). Black skin, white masks. London: Pluto Press.

- Fazel, M., Patel, V., Thomas, S., & Tol, W. (2014). Mental health interventions in schools in low-income and middle-income countries. The Lancet Psychiatry, 1(5), 388-398. [CrossRef]

- Frisén, A., Lunde, C., & Berg, A. I. (2015). Developmental patterns in body esteem from late childhood to young adulthood: A growth curve analysis. European Journal of Developmental Psychology, 12(1), 99-115. [CrossRef]

- Gomez-Baya, D., Mendoza, R., Matos, M. G. D., & Tomico, A. (2019). Sport participation, body satisfaction and depressive symptoms in adolescence: A moderated-mediation analysis of gender differences. European Journal of Developmental Psychology, 16(2), 183-197. [CrossRef]

- Halliwell, E., Dawson, K., & Burkey, S. (2019). A randomized experimental evaluation of a yoga-based body image intervention. Body Image, 28, 119-127. [CrossRef]

- Haraldstad, K., Christophersen, K. A., Eide, H., Nativg, G. K., & Helseth, S. (2011). Predictors of health-related quality of life in a sample of children and adolescents: A school survey. Journal of clinical nursing, 20(21-22), 3048-3056. [CrossRef]

- Jachyra, P. (2016). Boys, bodies, and bullying in health and physical education class: 5 implications for participation and well-being. Asia-Pacific Journal of Health, Sport and Physical Education 7(2): 121–138. [CrossRef]

- Jang, H. Y., Ahn, J. W., & Jeon, M. K. (2018). Factors affecting body image discordance amongst Korean adults aged 19–39 years. Osong Public Health and Research Perspectives, 9(4), 197-206. [CrossRef]

- Jones, L. E., Buckner, E., & Miller, R. (2014). Chronological progression of body dissatisfaction and drive for thinness in females 12 to 17 years of age. Pediatric nursing, 40(1).

- Juli, M.R. (2017). Perception of body image in early adolescence. An investigation in secondary schools. Psychiatr Danub.29(Suppl 3):409–415.

- Liechty, T., Sveinson, K., Willfong, F., & Evans, K. (2015). ‘It doesn't matter how big or small you are… there's a position for you’: Body image among female tackle football players. Leisure Sciences, 37(2), 109-124.

- Love, R., Adams, J., & van Sluijs, E. M. (2019). Are school-based physical activity interventions effective and equitable? A meta-analysis of cluster randomized controlled trials with accelerometer-assessed activity. Obesity Reviews, 20(6), 859-870. [CrossRef]

- Mahlo, L., & Tiggemann, M. (2016). Yoga and positive body image: A test of the embodiment model. Body Image, 18, 135-142. [CrossRef]

- Mellor, D., Waterhouse, M., Mamat, N. H. b., Xu, X., Cochrane, J., McCabe, M., & Ricciardelli, L. (2013). Which body features are associated with female adolescents’ body dissatisfaction? A cross-cultural study in Australia, China and Malaysia. Body Image, 10, 54-61. [CrossRef]

- Mendelson, M. J., Mendelson, B. K., & Andrews, J. (2000). Self-esteem, body esteem, and body-mass in late adolescence: Is a competence importance model needed? Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology, 21(3), 249-266. [CrossRef]

- Mendelson, B. K., Mendelson, M. J., & White, D. R. (2001). Body-esteem scale for adolescents and adults. Journal of Personality Assessment, 76(1), 90-106. [CrossRef]

- Metcalf, B., Henley, W. & Wilkin, T. (2012). Effectiveness of intervention on physical activity of children: Systematic review and meta-analysis of controlled trials with objectively measured outcomes (Early Bird 54). British Medical Journal; 345. [CrossRef]

- Michie, S., Van Stralen, M. M., & West, R. (2011). The behaviour change wheel: A new method for characterising and designing behaviour change interventions. Implementation science, 6(1), 1-12. [CrossRef]

- Milat, A. J., King, L., Bauman, A. E., & Redman, S. (2013). The concept of scalability: Increasing the scale and potential adoption of health promotion interventions into policy and practice. Health promotion international, 28(3), 285-298. [CrossRef]

- Milat, A. J., King, L., Newson, R., Wolfenden, L., Rissel, C., Bauman, A., & Redman, S. (2014). Increasing the scale and adoption of population health interventions: Experiences and perspectives of policy makers, practitioners, and researchers. Health Research Policy and Systems, 12(1), 1-11. [CrossRef]

- Miranda, V. P., Amorim, P. R. S., Bastos, R. R., Souza, V. G., Faria, E. R., Franceschini, S. C., & Priore, S. E. (2021). Body image disorders associated with lifestyle and body composition of female adolescents. Public Health Nutrition, 24(1), 95-105. [CrossRef]

- Murphy, K. R., & Myors, B. (2004). Statistical power analysis: A simple and general model for traditional and modern hypothesis tests (2nd ed.). Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

- Nelson, S. C., Kling, J., Wängqvist, M., Frisén, A., & Syed, M. (2018). Identity and the body: Trajectories of body esteem from adolescence to emerging adulthood. Developmental psychology, 54(6), 1159.

- Nevill, A. M., Lane, A.M., & Duncan, M. (2015). Stability of self-report body-image: Implications for health and well-being. Journal of Sports Sciences, 33(18), 1-9.

- Ntoumanis, N., Ng, J. Y., Prestwich, A., Quested, E., Hancox, J. E., Thøgersen-Ntoumani, C., & Williams, G. C. (2021). A meta-analysis of self-determination theory-informed intervention studies in the health domain: Effects on motivation, health behavior, physical, and psychological health. Health psychology review, 15(2), 214-244. [CrossRef]

- Norrish, H., Farringdon, F., Bulsara, M., & Hands, B. (2012). The effect of school uniform on incidental physical activity among 10-year-old children. Asia-Pacific Journal of Health, Sport and Physical Education, 3(1), 51-63. [CrossRef]

- Pawlowski, C. S., Schipperijn, J., Tjørnhøj-Thomsen, T., & Troelsen, J. (2018). Giving children a voice: Exploring qualitative perspectives on factors influencing recess physical activity. European Physical Education Review, 24(1), 39-55. [CrossRef]

- Ricciardelli, L,A. & Yager, Z. (2016) Adolescence and Body Image: From Development to Preventing Dissatisfaction. New York, NY: Routledge.

- Rubin, B., Gluck, M. E., Knoll, C. M., Lorence, M., & Geliebter, A. (2008). Comparison of eating disorders and body image disturbances between Eastern and Western countries. Eating and Weight Disorders-Studies on Anorexia, Bulimia and Obesity, 13(2), 73-80. [CrossRef]

- Sabiston, C. M., Pila, E., Vani, M., & Thogersen-Ntoumani, C. (2019). Body image, physical activity, and sport: A scoping review. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 42, 48-57. [CrossRef]

- Scully, M., Swords, L., & Nixon, E. (2020). Social comparisons on social media: Online appearance-related activity and body dissatisfaction in adolescent girls. Irish Journal of Psychological Medicine, 1-12. [CrossRef]

- Smolak, L. (2009). Risk factors in the development of body image, eating problems, and obesity.

- Slater, A., & Tiggemann, M. (2011). Gender differences in adolescent sport participation, teasing, self-objectification and body image concerns. Journal of adolescence, 34(3), 455-463. [CrossRef]

- Sport England (2008). Sport England Strategy: 2008–2011, London, UK.

- Spreckelsen, P. V., Glashouwer, K. A., Bennik, E. C., Wessel, I., & de Jong, P. J. (2018). Negative body image: Relationships with heightened disgust propensity, disgust sensitivity, and self-directed disgust. PLoS ONE, 13(6), e0198532. [CrossRef]

- Standiford, A. (2013). The secret struggle of the active girl: A qualitative synthesis of interpersonal factors that influence physical activity in adolescent girls. Health Care for Women International, 34(10), 860-877. [CrossRef]

- Tiggemann, M., & Lacey, C. (2009). Shopping for clothes: Body satisfaction, appearance investment, and functions of clothing among female shoppers. Body Image, 6(4), 285-291. [CrossRef]

- Tiggemann, M. (2015). Considerations of positive body image across various social identities and special populations. Body Image, 14, 168-176. [CrossRef]

- Thompson, J. K. (2004). The (mis)measurement of body image: Ten strategies to improve assessment for applied and research purposes. Body Image, 1(1), 7-14. [CrossRef]

- Velija, P, & Kumar, G. (2009). GCSE Physical education and the embodiment of gender. Sport, Education and Society, 14 (4), 383 - 399. [CrossRef]

- Yan, F., M Johnson, A., Harrell, A., Pulver, A., & Zhang, J. (2015). Perception or reality of body weight: Which matters the most to adolescents’ emotional well-being? Current Psychiatry Reviews, 11(2), 130-146. [CrossRef]

- Wang, S. B., Haynos, A. F., Wall, M. M., Chen, C., Eisenberg, M. E., & Neumark-Sztainer, D. (2019). 638 Fifteen-year prevalence, trajectories, and predictors of body dissatisfaction from adolescence to 639 middle adulthood. Clinical Psychological Science, 7(6), 1403-1415. [CrossRef]

- Watson, A., Eliott, J., & Mehta, K. (2015). Perceived barriers and facilitators to participation in physical activity during the school lunch break for girls aged 12-13 years. European Physical Education Review, 21(2), 257-271. [CrossRef]

- Wichstrøm, L. & von Soest, T. (2016). Reciprocal relations between body satisfaction and selfesteem: A large 13-year prospective study of adolescents. Journal of adolescence 47: 16-27. [CrossRef]

- Zanon, A., Tomassoni, R., Gargano, M., Granai, M. G. (2016). Body image and health behaviors: Is there a relationship between lifestyles and positive body image? La Clinica Terapeutica, 167(3), 63–69. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).