1. Introduction

Internationalization and alternative ways for strategic management have been an objective for stakeholders in cultural industry, especially after COVID-19 pandemic crisis. During the past years “internationalization” has been almost exclusively related with promoting creation or content to larger audiences. Such a strategy seemed sufficient, even if empirical data did not always support such a belief. Technological progress and costs reduction in developing Virtual Reality (VR) and Augmented Reality (AR) applications, provides to cultural industry the opportunity to reach global audiences and to enrich their experience (Karafotias et al., 2022; Kargas, Loumos, & Varoutas, 2019).

As far as strategic management is concerned, there exist three distinct elements that seem to play a primitive role in developing strategy, namely (a) content, (b) context and finally (c) processes (Andrew M. Pettigrew, 1987; Wit & Meyer, 2010). These elements seem capable not only to develop a strategy but moreover to predict an implemented strategy’s performance (Ketchen, Thomas, & Reuben R. McDaniel, 1996), especially when the relationship between strategy and organizational performance is examined over time (A. Pettigrew & Whipp, 1993). Technological elements are involved in all three elements, changing perceptions, values and practices. Such an approach leads on rethinking strategic management in cultural industry, when new technologies are implemented, such as Virtual Reality (VR) and Augmented Reality (AR) technologies.

Context elements include conditions and forces in each business external environment, while companies have no control on these elements, even though they can adjust their strategies in order to respond to external – environments changes. Context can include socioeconomic, political, competitive and technological conditions, alongside with elements such as market structure, organizational culture, etc. Technologies can act as a mean to reach more easily and to understand external environment and moreover to get faster aware of changes in customers, conditions and international balance. Technology can provide to companies a competitive advantage in both external environment’s divisions, the outer context (environment) and the inner context (environment) (Andrew M. Pettigrew, 1985).

Content elements involve the strategic responses to the various industry’s forces, involving buyers, suppliers and competitors (Porter, 1996). Technological factors is the mean to predict and react to these forces leading to better alignment between a company and its working environment, alongside with better coherence between business’s strategy and resources. Such conditions are associated with higher performance (Ketchen et al., 1996). Technology can provide content element with a larger variety of strategic directions and practices during its attempts to initially formulate and later to reach its planned objectives (Moser, 2001; Wit & Meyer, 2010).

Process element involves all means (including technological means) under which a strategy can be successfully implemented (Huff & Reger, 1987; Andrew M. Pettigrew, 1997). Technology can be associated with the management of methods and activities for such an implementation, while there exist strong evidence that a strategy process is significantly influenced by the context of a strategy (Miles, Snow, Meyer, & Coleman, 1978; A. M. Pettigrew, 1992).

Current research provides evidence about developing VR and AR tools that can act as internationalization facilitators when it comes to cultural industry. The project’s objective was the development of an augmented and virtual tour guide for cultural industry stakeholders (e.g., Galleries, Museums, Libraries, Exhibitions) as a mean for business internationalization to global audience. Main technological aspects of all applications will be presented, alongside with development’s results. Current paper’ s objective is to provide evidence regarding how VR and AR contributes to cultural industry’s internationalization by leading to its digital transformation (Kargas, Karitsioti, & Loumos, 2019; Kargas & Varoutas, 2020; Loumos, Kargas, & Varoutas, 2018).

Research conducted during “VARSOCUL” project was funded by the European Regional Development Fund (ERDF) as part of the Greek National Scope Action entitled “RESEARCH-CREATE-INNOVATE”. The project’s main result, alongside with VR and AR tools developed are presented. In the next section, the theoretical framework of the conducted research is presented, while in

Section 3 the methodology used is provided. Project’s results are presented in

Section 4 with illustrations of what end – users can see.

2. Theoretical Framework

VR is offering a large variety of capabilities for educational purposes and skills development applications (Fowler, 2015). This potential can be used in formal educational processes as Monahan, McArdle and Bertolotto (Monahan, Mcardle, & Bertolotto, 2008) revealed, as well as in informal learning and for experimental purposes (Goodwin, Wiltshire, & Fiore, 2015). Moreover, it should be taken into account that without VR technologies, formal and informal learning are both inevitable in many cases with high risks or physical restrictions (Ott & Freina, 2015). That is why many museums and institutions have been proved more than willing to adopt VR technologies as a mean of engaging new audiences (e.g., in terms of age) when communicating historical information / content (Liaskos et al., 2022; Wang & Liu, 2019). These technologies seem most appropriate for new generations (e.g., Gen Z) which explore new means to enhance their creativity in both cultural and educational experiences (Christopoulos, Mavridis, Andreadis, & Karigiannis, 2011). Various recent projects confirm the significant relationship (Chrysanthakopoulou, Kalatzis, & Moustakas, 2021; Farazis, Thomopoulos, Bourantas, Mitsigkola, & Thomopoulos, 2019; Jung & tom Dieck, 2017; Soto-Martin, Fuentes-Porto, & Martin-Gutierrez, 2020) between Virtual Reality and 3-D modeling with education on cultural heritage for new generations.

Moreover, there is ongoing research on se of VR storytelling experiences and interactive storytelling experiences in cultural heritage and museums, according to the different forms of digital storytelling (J. F. Barber, 2016). Such forms of digital storytelling can be:

Oral histories, being the oldest mean of communication, appearing in most media (Levinson, 1999), while digital storytelling has been directly associated with the ancient art of storytelling (Alexander, 2011).

Podcasting, which includes combination of short videos or images, alongside with voice text and music (J. F. Barber, 2016),

Locative / Interactive narrative, that are collected from participant of an experience so that to create new cultural content evolving (narrative experiences) constantly evolving and often connected with specific locations (J. Barber, 2013).

Multimedia, used either in combination either separately, while multimedia digital storytelling experiences developed in the past included text and images, alongside with video, computer graphics and music (Branch, 2012), to create a deeper dimension and further immersion (Alexander, 2011) to end-user who is being transported to a simulated place (Murray, 1997),

Transmedia, that provide the same subject / story / artefact (narrative experiences) across various media platforms in a way that differentiates from platform to platform, but still connected (J. F. Barber, 2016).

Taking all the above under consideration it is well explained why digital storytelling has been extensively used in video game industry, in several movies and in education as well (Behmer, 2005; Bromberg, Techatassanasoontorn, & Diaz Andrade, 2013; Madej Krystina, 2003), while social media’s expansion to mass audience worldwide to take part in storytelling experiences (Lundby, 2009). Implementing digital storytelling to VR experiences has further helped Virtual Reality market to growth (WEARVR, 2018) and reach not only adults but moreover children aged 8 to 15 years (Yamada-Rice et al., 2017).

3. Methodology

An extensive users analysis coming from previous research works and projects was used (Kargas, Loumos, Mamakou, & Varoutas, 2022; M. Vayanou, Loumos, Kargas, & Kakaletris, 2019; M. Vayanou, Loumos, Kargas, Sidiropoulou, et al., 2019; M. Vayanou, Sidiropoulou, Loumos, Kargas, & Ioannidis, 2020; Maria Vayanou, Antoniou, Loumos, Kargas, et al., 2019; Maria Vayanou, Ioannidis, Loumos, & Kargas, 2018; Maria Vayanou, Sidiropoulou, Loumos, Kargas, & Ioannidis, 2020; Maria Vayanou, Ioannidis, Loumos, Sidiropoulou, & Kargas, 2019).

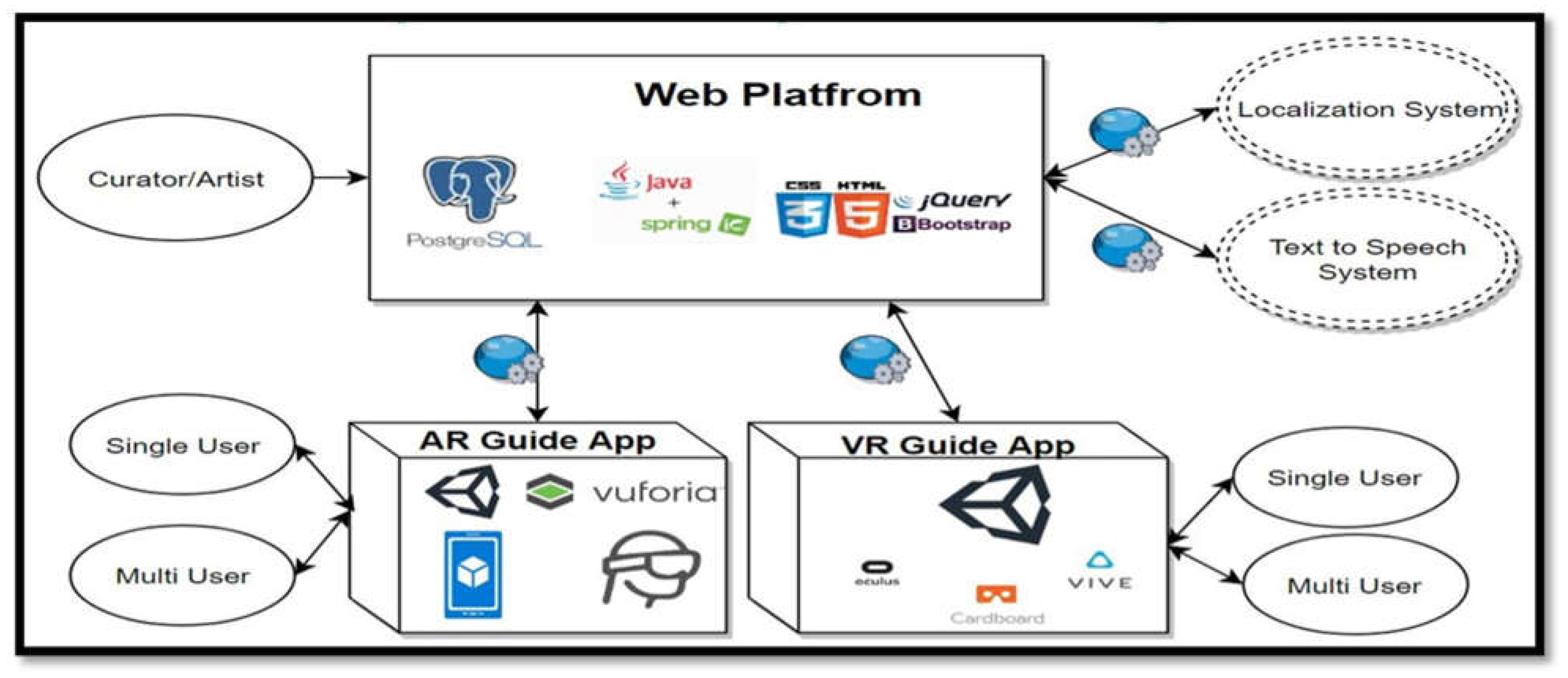

A two, interconnected strings platform was developed (

Figure 1). From the one hand a web platform acting as a repository of digital cultural artefacts and on the other hand end-users’ applications for smartphones and headsets/glasses of virtual, augmented or mixed reality. These applications were implemented for Android and IOS for mobile devices, while it included augmented reality as well as virtual reality platforms, such as: a) Oculus, b) SteamVR and c) GoogleVR.

Unity along with Unreal are the most well-known “Game Engines” that exist now and are available for free. These two machines are designed so that they can be used by small teams to implement projects without having to build everything from scratch. We chose Unity over Unreal as the engine which has invested more in the virtual reality technologies. By using the term “invest” we mean the fact that it has a huge availability in means of developing applications when compared with Unreal. These means vary from structured libraries to automations when it comes to applications’ development. Finally, it is an engine that is much easier to use and has a well-structured online forum.

4. Results

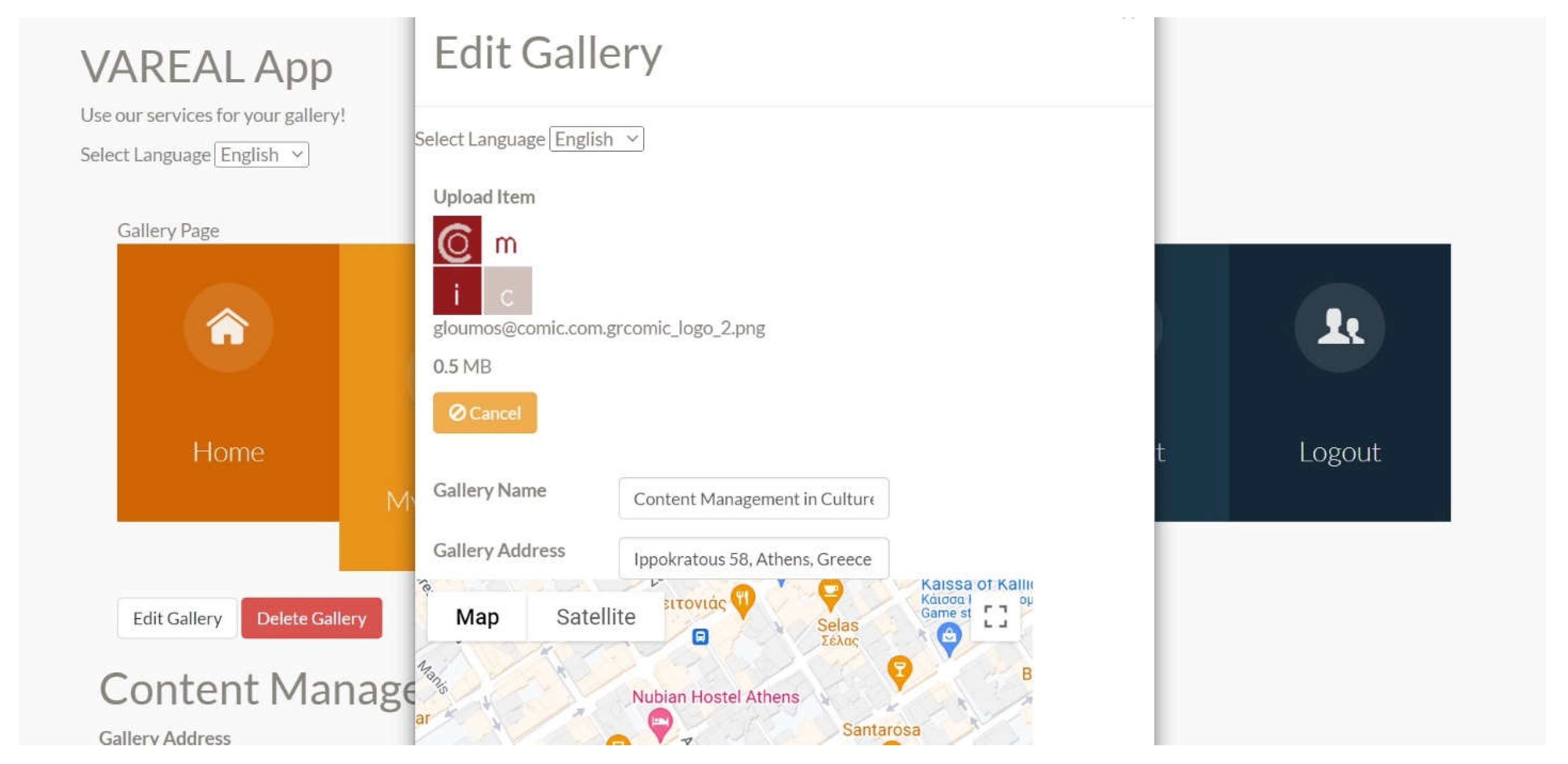

Web platform acts as a repository of digital cultural artefacts. The proposed platforms is not for end – users, but only for curators. Curators can create their unique personal profiles, alongside with their Gallery/Museum’s profile. Web platform acts as a repository of cultural artefacts by permitting to upload digital artefacts and moreover to interconnect them with desired information, such as title, historical information, creator’s information, materials and construction technique, curator’s comments etc. These data are used in a narrative way during end – users tour.

Moreover, curators can create and recommend cultural tours (routes) by defining the order of transition from exhibit to exhibit. At the same time, it will be possible to curate the information per exhibit in order to create a narrative text that will serve the proposed route and offer a resonant and coherent tour in the form of a storytelling experience.

At the final stage, web platform make use of two (2) more subsystems: (a) a translation subsystem and (b) a synthetic voice generation and narration subsystem. Thus, for each cultural artefact, exists voice – information in different languages. Also, for each of the previous languages, narrative audio content is produced to provide end - users with more vivid guided tour in their native language, which facilitates the combination of physical contact with the exhibit alongside with its digital information.

Figure 2 provides a short illustration of web platform’s development.

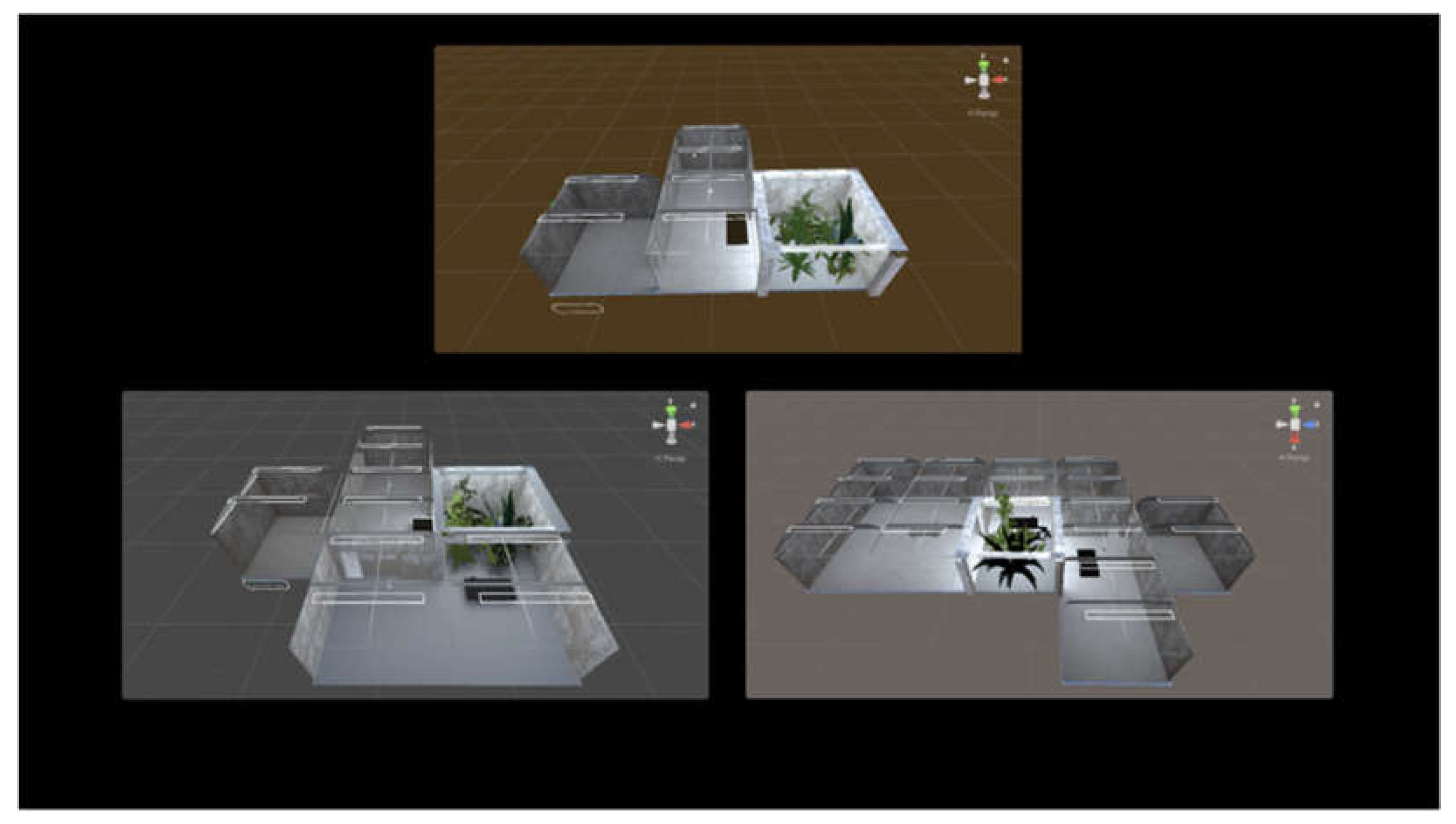

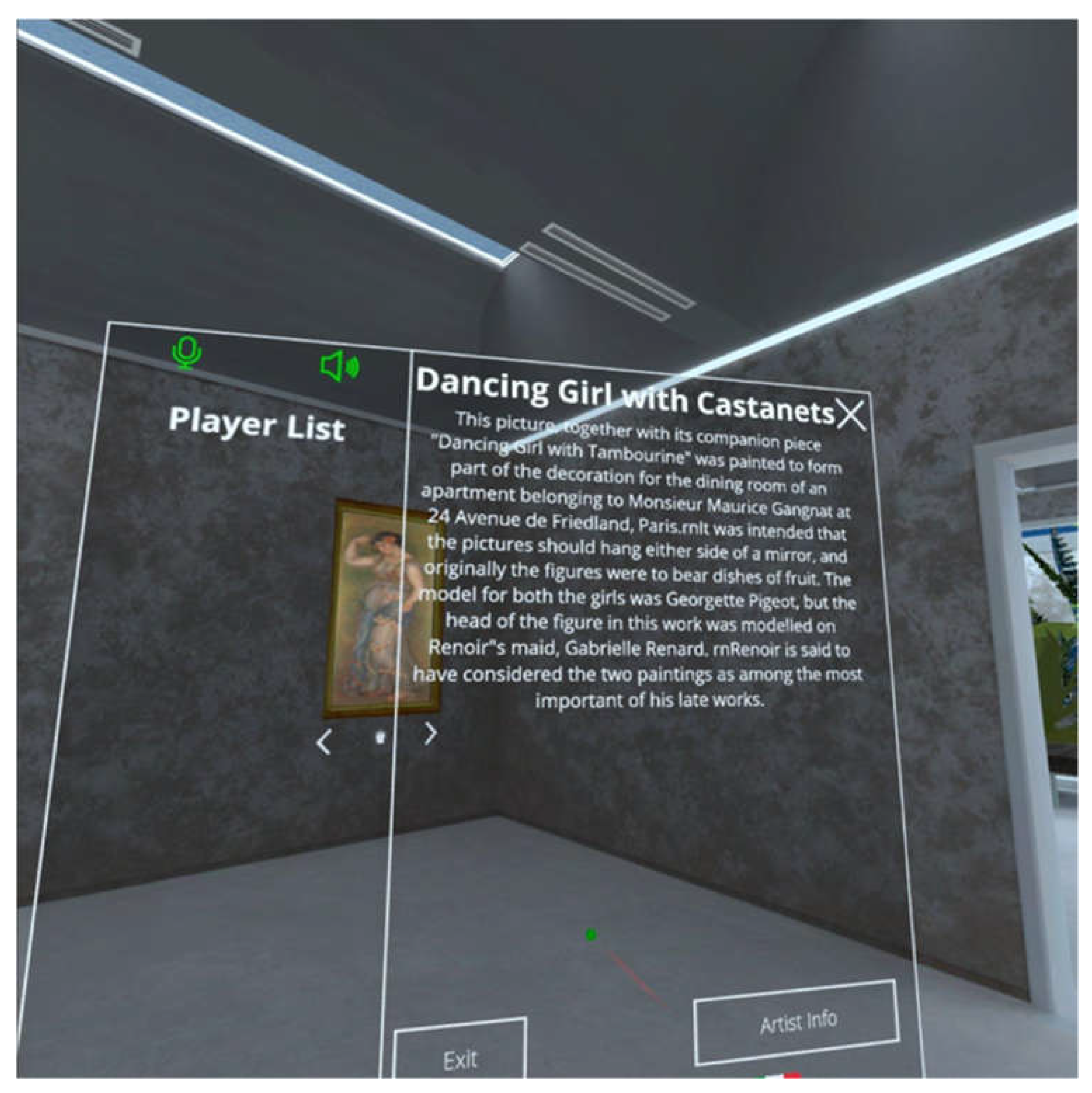

The Virtual Reality (VR) application serves as tour to an “imaginary” gallery or museum, existing or non – existing. A VR mask is required in order the end – user to have access to the VR exhibition. As far as VR application is concerned, both curators and users/visitors can reach the desired content. The former to set up exhibits and to check how their virtual exhibition is formed and the latter to reach an experience. Curators can create various exhibitions, with distinct thematic, by using parts from their total number of exhibits. All this procedure is taking place in VR environment.

Curators can then chose the number of places / rooms of their VR gallery / museum and moving from room to room he sets up the digital exhibits (

Figure 3). The application offers the following opportunities:

moving the exhibits from room to room,

choosing frames for each exhibit,

choosing the color and texture on the walls and

choosing the accompanying music.

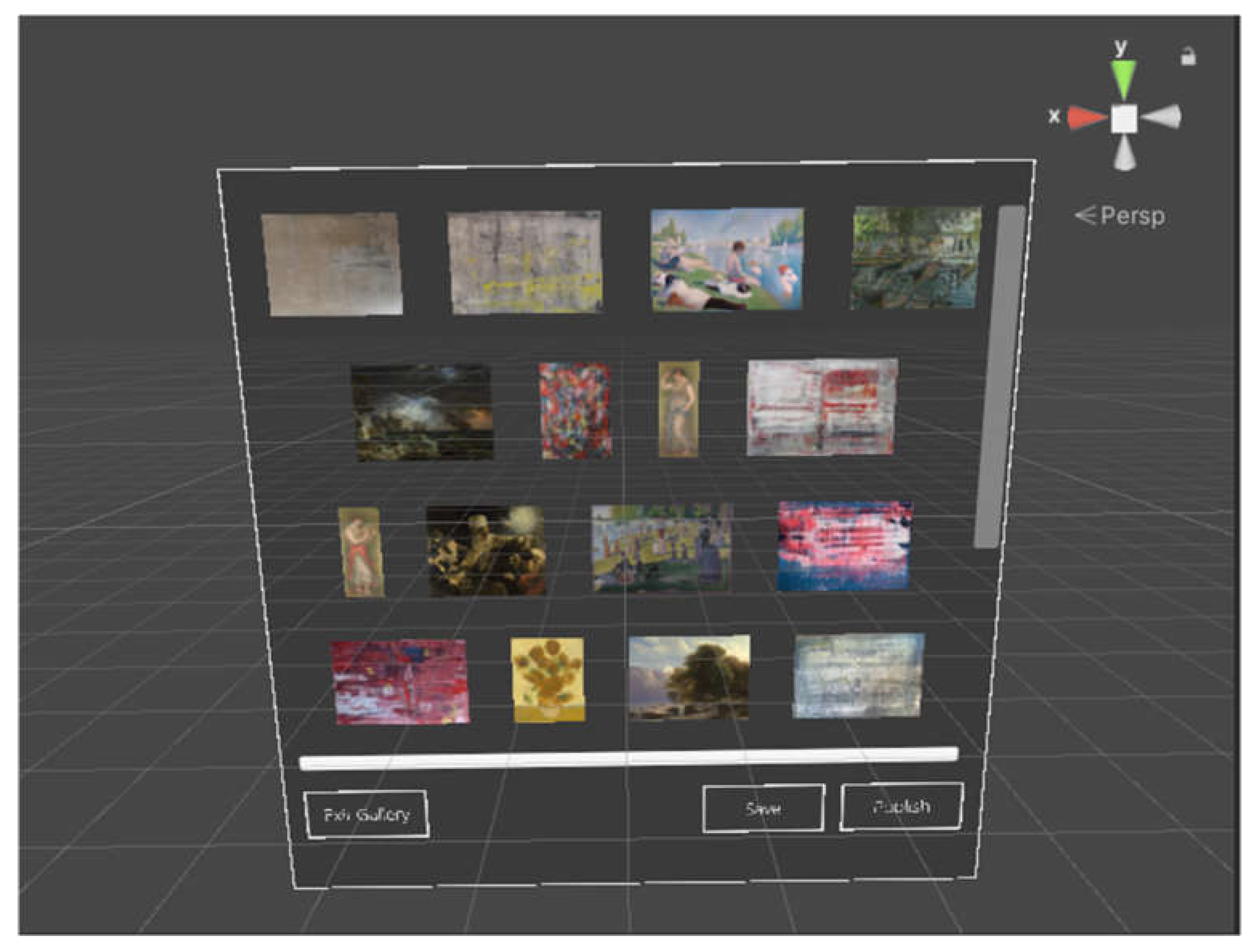

The whole procedure resembles to what would take place in a physical gallery when an exhibition is to be set up (

Figure 4). By finalizing this procedure, curator can release the VR exhibition to the world audience in order to take a tour, to reach digital artefact and to receive information (in text or oral format) regarding the exhibits.

End users should create an account in the virtual exhibition, while they can have access to every VR exhibition available, free of charge or after paying according to gallery’s museum’s policy. When an exhibition is chosen he could reach digital artefacts in rooms, either by his own, or accompanied with other users. Such an alternative can develop VR exhibitions into social “multi-spaces” of culture, with interactions among users. Subsequently, end – user will be able to navigate through the virtual exhibition and receive informative information either visually or audibly.

Furthermore, end – user can choose a guided tour suggested by the curator (predetermined choice) or alternatively to freely browse according to his wishes. Depending on the controllers and the capabilities of end – user’s virtual reality mask, he will be able to navigate with his hands or by giving predetermined commands with his mouth, thus making the experience more alive (

Figure 5).

When multi-visitors exist, e.g., school classes, the application supports group visits, simulating real-world conditions. The application supports audio chat between users (voice chat) and the display of directional messages as well as emoticons to express emotions between end – users. Moreover, avatars have been developed to enrich end – users experience, with an as much as possible realistic movements with zero response delay to the choices of the users who control them (

Figure 6).

Emphasis was put on developing mechanisms to collect and analyze the behavior of virtual users during their presence in the space, both in relation to the exhibits and to the rest of the users. Such mechanisms serve as feedback generators to curators and to decision makers, regarding their digital presence and success or failure of an VR exhibition / tour, as perceived by end – users. Metrics (indicatively) can be delivered, regarding the (mean) time of “engagement” between each exhibit and end - user(s), the overall evaluation of the exhibition, the use of emoticons for user communication, the quality of voice chat as well as the effectiveness of messages for organized group visits (e.g., . by young school students or groups of tourists).

A series of reports can be provided for curators use only, regarding each distinct exhibition. Data can provide insights about the optimal design of exhibitions and experiences, while technical comments can be collected for future improvements in the next version of the application.

The

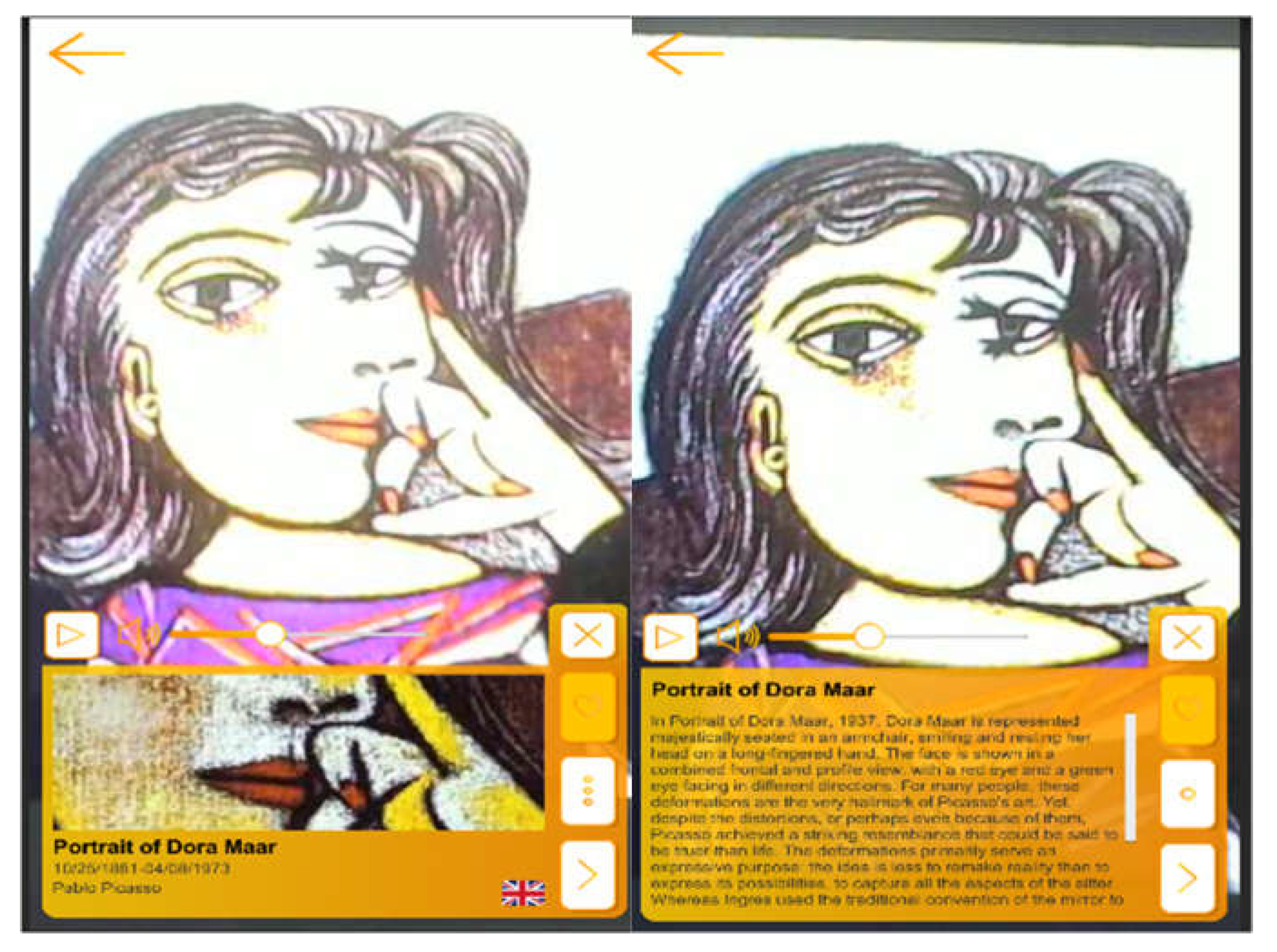

Augmented Reality (AR) application serves to guide the visitor or visitors through the physical space of an exhibition of a gallery or museum. The application works a) through mobile devices (mobile phones, tablets) or b) through augmented reality glasses (

Figure 7). These glasses are still in an experimental stage of use, but they show a rapid technological growth, and it is soon expected to be used for specific purposes such as the experience of a guided tour in cultural places.

Users can log into the application, and according to their geographical location, they can have access to exhibitions available for a tour that are nearby. The user can reach useful information for nearby cultural places available (such as guide languages per exhibition, information about some of the exhibits, opening hours, ticket price, available infrastructure, etc.).

When visiting an exhibition, the visitor can chose between tours designed from curators or to freely explore the exhibition. In both cases his mobile device (smartphone of AR glasses) scan exhibits and provide information upon request. End – user simply has to point the device towards the exhibit he wants to see and then the application recognizes it and can offer him visual and/or audio information about each object in any chosen language (

Figure 8).

When it comes to the case of AR glasses, the application can receive specific audio commands from the visitor and to provide answers related to the exhibition, the objects or the creators of the artefacts, while following the visitor’s movement is the space.

In the case of mass visits and users in the application, special functions are provided to organize the visitors but also to arouse their interest in specific exhibits. Through a gamification mechanism, the application prompts users/visitors to participate in short collaborative activities (e.g., mini games) focusing on the exhibits and exhibition spaces.

As well as in VR application, AR application has its own mechanisms for metrics, in order to analyze the interaction of visitors with physical exhibits and also with other visitors, when it comes to organized visits. All data are given as reports to the curators of each exhibition, while technical comments are collected by the technical team for future improvements in the next version of the application.

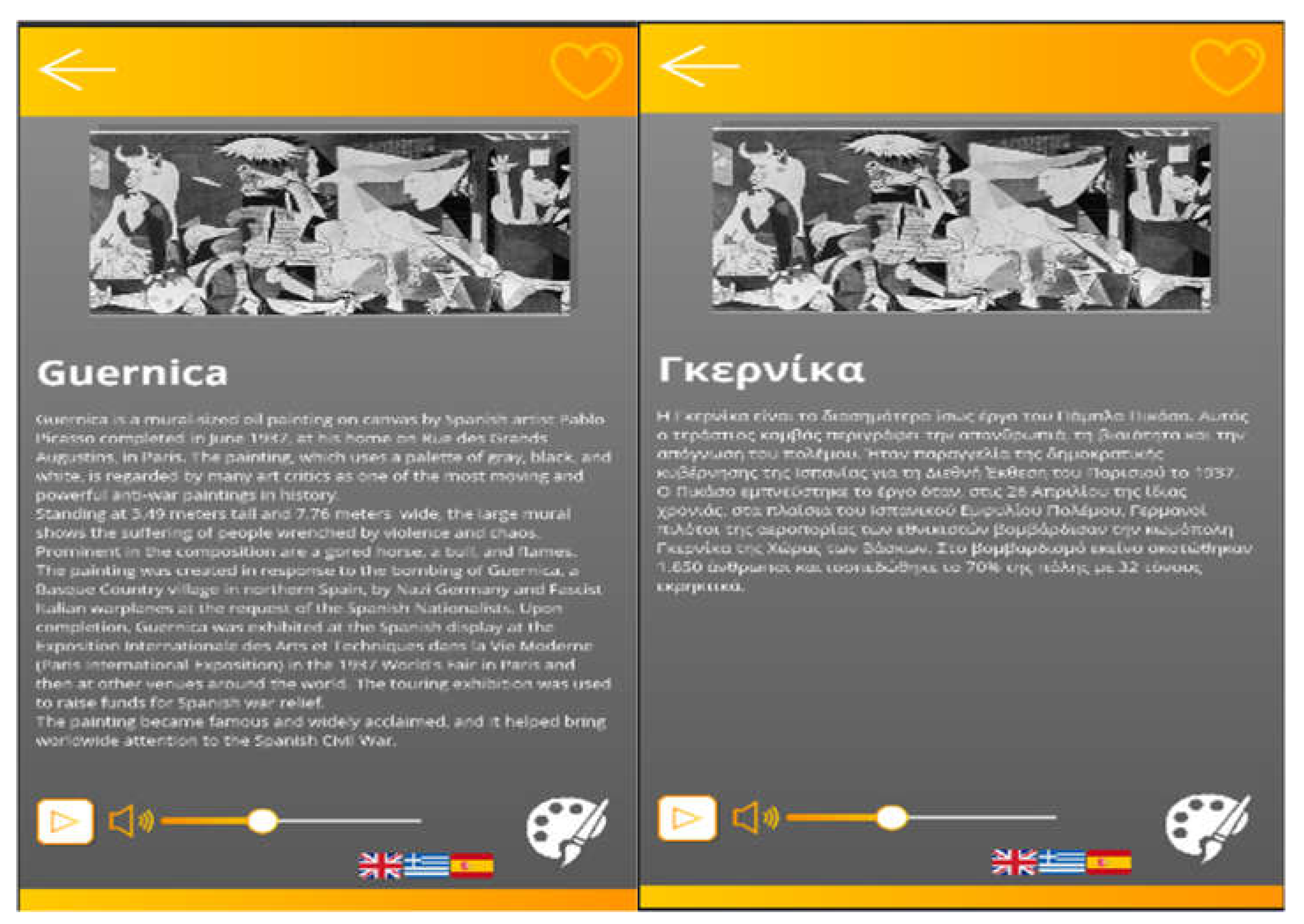

Finally, the application supports multilanguage content (

Figure 9), permitting end – users to change the language preferred at any stage of their tour.

5. Discussion

Presented applications give evidence provide an insight on how cultural content can be implemented in VR and AR applications, while moreover it provides an insight on how digital transformation in cultural industry can reshape existing strategies and business models. Discussion of results starts by taking as granted that a firm’s strategy can be reached be studying its activities (Richardson, 2008), explaining why digital transformation and strategy transformation is interesting era of scientific research (Demil & Lecocq, 2010).

Changes taking place in organizations external environment make digital transformation a necessity, followed by a repositioning of current strategy (Pearce & Robbins, 2008). Cultural industry can not be unaffected. COVID-19 led to a strategy’s repositioning regarding technological implementation and adoption of mixed reality technologies. Even though external treats and opportunities is not something new in business strategy theory, little knowledge still exists on how such conditions affect business models (Saebi, Lien, & Foss, 2014). Digital transformation and technological adaptation is part of business model because the latter consists of what an organization “is and does” (Mason & Spring, 2011) alongside with developing mechanism of value creation (Foss & Saebi, 2017).

Technological factors, such as VR and AR applications can differentiate any organizations from its competitors, providing a new competitive strategy or a competitive advantage as a whole (Chesbrough, 2007; Teece, 2010). Implementing such technologies open new era of business development for cultural industry while creates the prospects for a broader strategic transformation. Such a repositioning can take place as a result of a more aggressive ability to manage change and to reach higher level of competitiveness (Chesbrough, 2007; Giesen, Berman, Bell, & Blitz, 2007), alongside with better understanding business environment and potentials of collaborative activities (Neu & Brown, 2008)

Proposed research contributes to a higher understanding on how immersive technologies can be used as a mean for digital transformation and strategic transformation as well. Such a framework creates the need for a change, an a-priori delicate subject when competitive strategies are involved (Kindström, 2010). By implementing such technologies to a non – high – tech oriented industry, with extended digital content (or under digitization content), can lead as future research a research question regarding what capabilities may facilitate the strategic repositioning and the development of a new path for strategic development.

Acknowledgements

The project is part of the National Scope Action “RESEARCH-CREATE-INNOVATE” of the Operational Programme Competitiveness, Entrepreneurship and Innovation, co-funded by the European Regional Development Fund (ERDF) and national resources, under the NSRF 2014-2020.

References

- Alexander, B. (2011). The new digital storytelling : creating narratives with new media. Santa Barbara: Praeger.

- Barber, J. (2013). Walking-Talking: Soundscapes, Flâneurs, and the Creation of Mobile Media Narratives. In J. Farman (Ed.), The mobile story: Narrative practices with locative technologies (pp. 95–109). New York: Routledge. [CrossRef]

- Barber, J.F. Digital storytelling: New opportunities for humanities scholarship and pedagogy. Cogent Arts Humanit. 2016, 3, 1181037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behmer, S. (2005). Literature Review Digital storytelling: Examining the process with middle school students. In Society for Information Technology & teacher education international conference (pp. 1–23).

- Branch, J. “Snow Fall: The Avalanche at Tunnel Creek. Retrieved August 9, 2022. 2012. Available online: http://www.nytimes.com/projects/2012/snow-fall/index.html.

- Bromberg, N.R.; Auckland University of Technology; Techatassanasoontorn, A. A.; Andrade, A.D. Engaging Students: Digital Storytelling in Information Systems Learning. Pac. Asia J. Assoc. Inf. Syst. 2013, 5, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chesbrough, H. (2007). Business model innovation: It’s not just about technology anymore. Strategy and Leadership, 35(6), 12–17. [CrossRef]

- Christopoulos, D.; Mavridis, P.; Andreadis, A.; Karigiannis, J.N. Using Virtual Environments to Tell the Story: "The Battle of Thermopylae". 2011 3rd International Conference on Games and Virtual Worlds for Serious Applications, VS-Games 2011, pp. 84–91.

- Chrysanthakopoulou, A.; Kalatzis, K.; Moustakas, K. Immersive Virtual Reality Experience of Historical Events Using Haptics and Locomotion Simulation. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 11613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- nbsp; Burmeister, C. ; Luettgens, D.; Piller, F.T. Business Model Innovation for Industrie 4.0: Why the ‘Industrial Internet’ Mandates a New Perspective. Die Unternehm. 2010, 43, 227–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farazis, G.; Thomopoulos, C.; Bourantas, C.; Mitsigkola, S.; Thomopoulos, S.C. Digital approaches for public outreach in cultural heritage: The case study of iGuide Knossos and Ariadne's Journey. Digit. Appl. Archaeol. Cult. Heritage 2019, 15, e00126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foss, N.J.; Saebi, T. Fifteen Years of Research on Business Model Innovation. J. Manag. 2017, 43, 200–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fowler, C. Virtual reality and learning: Where is the pedagogy? Br. J. Educ. Technol. 2014, 46, 412–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giesen, E.; Berman, S.J.; Bell, R.; Blitz, A. Three ways to successfully innovate your business model. Strat. Leadersh. 2007, 35, 27–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodwin, M. S. , Wiltshire, T., & Fiore, S. M. (2015). Applying Research in the Cognitive Sciences to the Design and Delivery of Instruction in Virtual Reality Learning Environments (pp. 280–291). [CrossRef]

- Huff, A.S.; Reger, R.K. A Review of Strategic Process Research. J. Manag. 1987, 13, 211–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, T.H.; tom Dieck, M.C. Augmented reality, virtual reality and 3D printing for the co-creation of value for the visitor experience at cultural heritage places. J. Place Manag. Dev. 2017, 10, 140–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karafotias, G. , Gkourdoglou, G., Maroglou, C., Koliniatis, C., Loumos, G., Kargas, A., & Varoutas, D. (2022). Developing VR applications for cultural heritage to enrich users’ experience: The case of Digital Routes in Greek History’s Paths (RoGH project). International Journal of Cultural Heritage, 07, 32–53. Retrieved from http://iaras.org/iaras/journals/ijch.

- Kargas, A. , Karitsioti, N., & Loumos, G. (2019). Reinventing Museums in 21st Century: Implementing Augmented Reality and Virtual Reality Technologies Alongside Social Media’s Logics. In G. Guazzaroni & A. S. Pillai (Eds.), Virtual and Augmented Reality in Education, Art, and Museums (pp. 117–138). IGI Global. [CrossRef]

- Kargas, A.; Loumos, G.; Mamakou, I.; Varoutas, D. Digital Routes in Greek History’s Paths. Heritage 2022, 5, 742–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kargas, A.; Loumos, G.; Varoutas, D. Using Different Ways of 3D Reconstruction of Historical Cities for Gaming Purposes: The Case Study of Nafplio. Heritage 2019, 2, 1799–1811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kargas, A. , & Varoutas, D. (2020). Industry 4.0 in Cultural Industry. A Review on Digital Visualization for VR and AR Applications. In C. M. Bolognesi & S. Cettina (Eds.), Impact of Industry 4.0 on Architecture and Cultural Heritage (pp. 1–19). Hershey, PA: IGI Global. [CrossRef]

- Ketchen, D.J.; Thomas, J.B.; McDaniel, R.R. Process, Content and Context: Synergistic Effects on Organizational Performance. J. Manag. 1996, 22, 231–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kindström, D. Towards a service-based business model – Key aspects for future competitive advantage. Eur. Manag. J. 2010, 28, 479–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levinson, P. (1999). Digital McLuhan : a guide to the information millennium. Routledge. Retrieved from https://www.routledge.com/Digital-McLuhan-A-Guide-to-the-Information-Millennium/Levinson/p/book/9780415249911.

- Liaskos, O.; Mitsigkola, S.; Arapakopoulos, A.; Papatzanakis, G.; Ginnis, A.; Papadopoulos, C.; Peppa, S.; Remoundos, G. Development of the Virtual Reality Application: “The Ships of Navarino”. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 3541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loumos, G. , Kargas, A., & Varoutas, D. (2018). Augmented and Virtual Reality Technologies in cultural Sector: Exploring their Usefulness and the Perceived Ease of Use. Journal of Media Critiques [JMC], 4(14). [CrossRef]

- Lundby, K. (2009). Digital storytelling, mediatized stories : self-representations in new media. New York: P. Lang.

- Madej, K. Towards digital narrative for children. Comput. Entertain. 2003, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mason, K.; Spring, M. The sites and practices of business models. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2011, 40, 1032–1041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miles, R.E.; Snow, C.C.; Meyer, A.D.; Coleman, H.J. Organizational Strategy, Structure, and Process. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1978, 3, 546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monahan, T.; McArdle, G.; Bertolotto, M. Virtual reality for collaborative e-learning. Comput. Educ. 2008, 50, 1339–1353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moser, T. MNCs and Sustainable Business Practice: The Case of the Colombian and Peruvian Petroleum Industries. World Dev. 2001, 29, 291–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murray, J. H. (1997). Hamlet on the Holodeck: The Future of Narrative in Cyberspace. (Simon and Schuster, Ed.), Free Press. Retrieved from https://books.google.com/books/about/Hamlet_on_the_Holodeck.html?id=bzmSLtnMZJsC.

- Neu, W. A. , & Brown, S. W. (2008). Manufacturers forming successful complex business services: Designing an organization to fit the market. International Journal of Service Industry Management, 19(2), 232–251. [CrossRef]

- Ott, M. , & Freina, L. (2015). A LITERATURE REVIEW ON IMMERSIVE VIRTUAL REALITY IN EDUCATION: STATE OF THE ART AND PERSPECTIVES. In he International Scientific Conference eLearning and Software for Education. Retrieved from https://www.semanticscholar. 3892. [Google Scholar]

- Pearce, J.A.; Robbins, D.K. Strategic transformation as the essential last step in the process of business turnaround. Bus. Horizons 2008, 51, 121–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pettigrew, A. M. (1992). The Character and Significance of Strategy Process Research on JSTOR. Strategic Management Journal, 13, 5–16. Retrieved from https://www.jstor.org/stable/2486363.

- Pettigrew, A. , & Whipp, R. (1993). Pettigrew: Managing change for competitive success - Google Scholar. Oxford: Blackwell. Retrieved from https://www.wiley.com/en-us/Managing+Change+for+Competitive+Success-p-9780631191421.

- Pettigrew, Andrew M. (1985). The awakening giant : continuity and change in Imperial Chemical Industries. Oxford: Routledge. Retrieved from https://www.routledge.com/The-Awakening-Giant-Routledge-Revivals-Continuity-and-Change-in-ICI/Pettigrew/p/book/9780415668767. 9780.

- Pettigrew, A.M. Context and action in the transformation of the firm. J. Manag. Stud. 1987, 24, 649–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pettigrew, A.M. What is a processual analysis? Scand. J. Manag. 1997, 13, 337–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porter, E. (1996). What Is Strategy? Harvard Business Review, 74, 61–78. Retrieved from https://hbr. 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Richardson, J. The business model: an integrative framework for strategy execution. Strat. Chang. 2008, 17, 133–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saebi, T.; Lien, L.; Foss, N.J. What Drives Business Model Adaptation? The Impact of Opportunities, Threats and Strategic Orientation. Long Range Plan. 2014, 47, 132–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soto-Martin, O.; Fuentes-Porto, A.; Martin-Gutierrez, J. A Digital Reconstruction of a Historical Building and Virtual Reintegration of Mural Paintings to Create an Interactive and Immersive Experience in Virtual Reality. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teece, D.J. Business Models, Business Strategy and Innovation. Long Range Plan. 2010, 43, 172–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vayanou, M.; Loumos, G.; Kargas, A.; Kakaletris, G. The IIIσETO project: Storytelling games for groups of visitors in fine art exhibitions. In CEUR Workshop Proceedings (Vol. 2412).

- Vayanou, M.; Loumos, G.; Kargas, A.; Sidiropoulou, O.; Apostolopoulos, K.; Ioannidis, E.; Kakaletris, G.; Ioannidis, Y. (2019). Cultural Mobile Games: Designing for ‘Many’. 2019 11th International Conference on Virtual Worlds and Games for Serious Applications, VS-Games 2019 - Proceedings.

- Vayanou, M.; Sidiropoulou, O.; Loumos, G.; Kargas, A.; Ioannidis, Y. Investigating the Artist’s Role in Social Group Games. EAI Endorsed Trans. Creative Technol. 2020, 6, 163157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vayanou, M.; Antoniou, A.; Loumos, G.; Kargas, A.; Kakaletris, G.; Ioannidis, Y. Towards Personalized Group Play in Gallery Environments. CHI PLAY 2019 - Extended Abstracts of the Annual Symposium on Computer-Human Interaction in Play; pp. 739–746.

- Vayanou, M.; Ioannidis, Y.; Loumos, G.; Kargas, A. How to play storytelling games with masterpieces: from art galleries to hybrid board games. J. Comput. Educ. 2018, 6, 79–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vayanou, M.; Ioannidis, Y.; Loumos, G.; Sidiropoulou, O.; Kargas, A. Designing Performative, Gamified Cultural Experiences for Groups. CHI '19: CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems. LOCATION OF CONFERENCE, United KingdomDATE OF CONFERENCE; p. LBW0179.

- Vayanou, Maria, Sidiropoulou, O., Loumos, G., Kargas, A., & Ioannidis, Y. (2020). Playing with the artist. Lecture Notes of the Institute for Computer Sciences, Social-Informatics and Telecommunications Engineering, LNICST, 328 LNICST, 566–579. [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Liu, Y. The Research on Application of Virtual Reality Technology in Museums. J. Physics: Conf. Ser. 2019, 1302, 042049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WEARVR. (2018). ICO White Paper: Introducing WEAVE from WEARVR. Retrieved August 9, 2022, from https://documentsn.com/document/4eaa4_weave-whitepaper-2-digitalcoindata-com.html.

- Wit, B. de. , & Meyer, R. (2010). Strategy: process, content, context; an international perspective. London: Cengage Learning. Retrieved from https://books.google.com/books/about/Strategy.html?hl=el&id=tCspQP0CYgcC.

- Yamada-Rice, D. , Mushtaq, F., Woodgate, A., Bosmans, D., Douthwaite, A., Douthwaite, I., … Whitley, S. (2017). Children and Virtual Reality: Emerging Possibilities and Challenges. Retrieved August 9, 2022, from https://researchonline.rca.ac.uk/3553/.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).