Submitted:

29 April 2023

Posted:

29 April 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

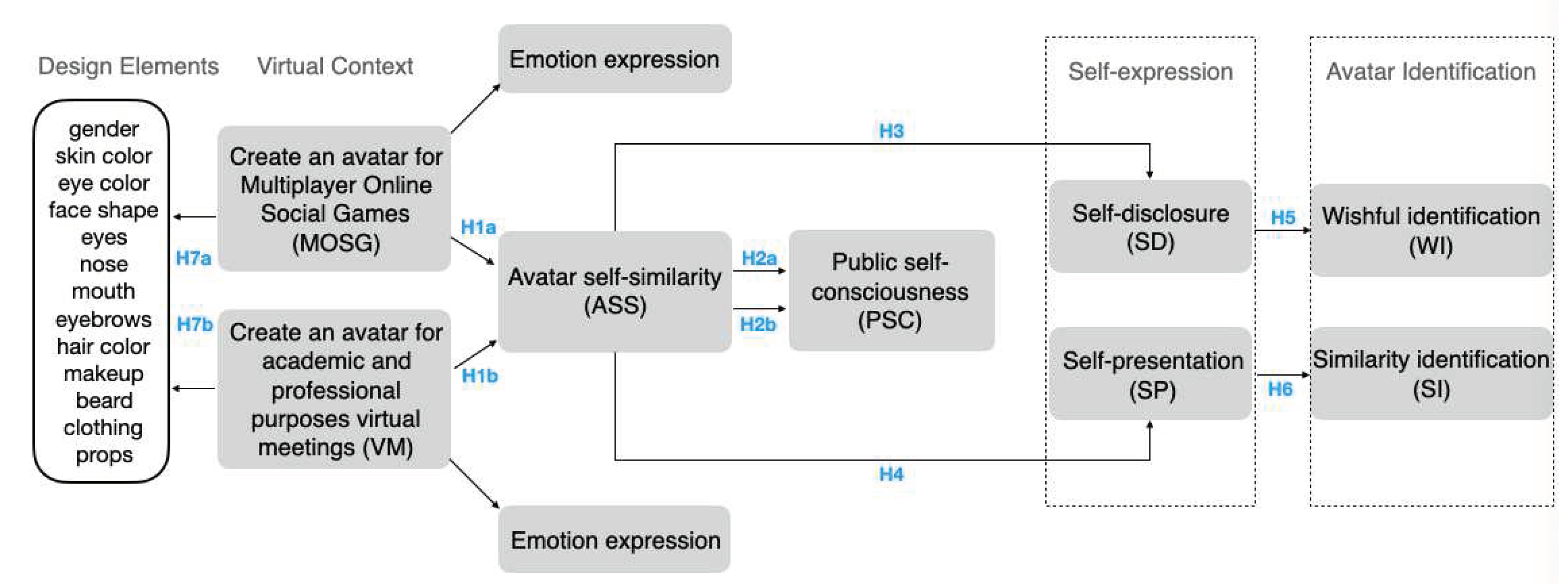

2. Theoretical background and hypotheses

2.1. Subsection Avatar in virtual social environment

2.2. Subsection Avatar customization and similarity

2.3. The effect of public self-consciousness on avatar self-similarity

2.4. Self-expression

2.5. Emotional expression and avatar identification

2.6. Summary

3. Materials and methods

3.1. Experimental Design

3.2. Avatar Custom Platform

3.3. Measurements

3.3.1. Self-similarity measurement

3.3.2. Avatar design elements measurement

3.3.3. Perception factors measurements

3.3.4. Emotion expression measurements

4. Results analysis

4.1. Content reliability

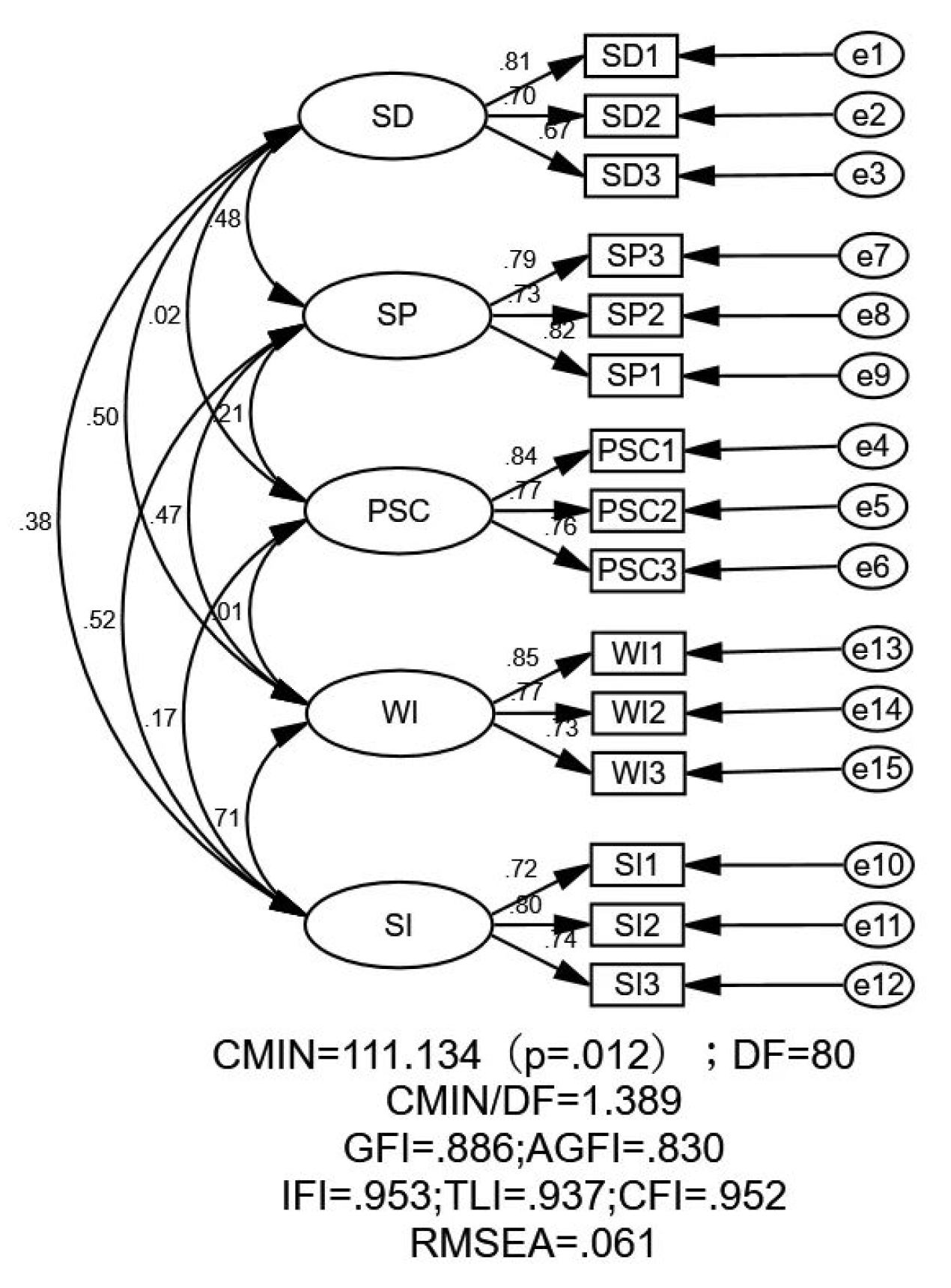

4.2. Content validity

4.3. Avatar self-similarity

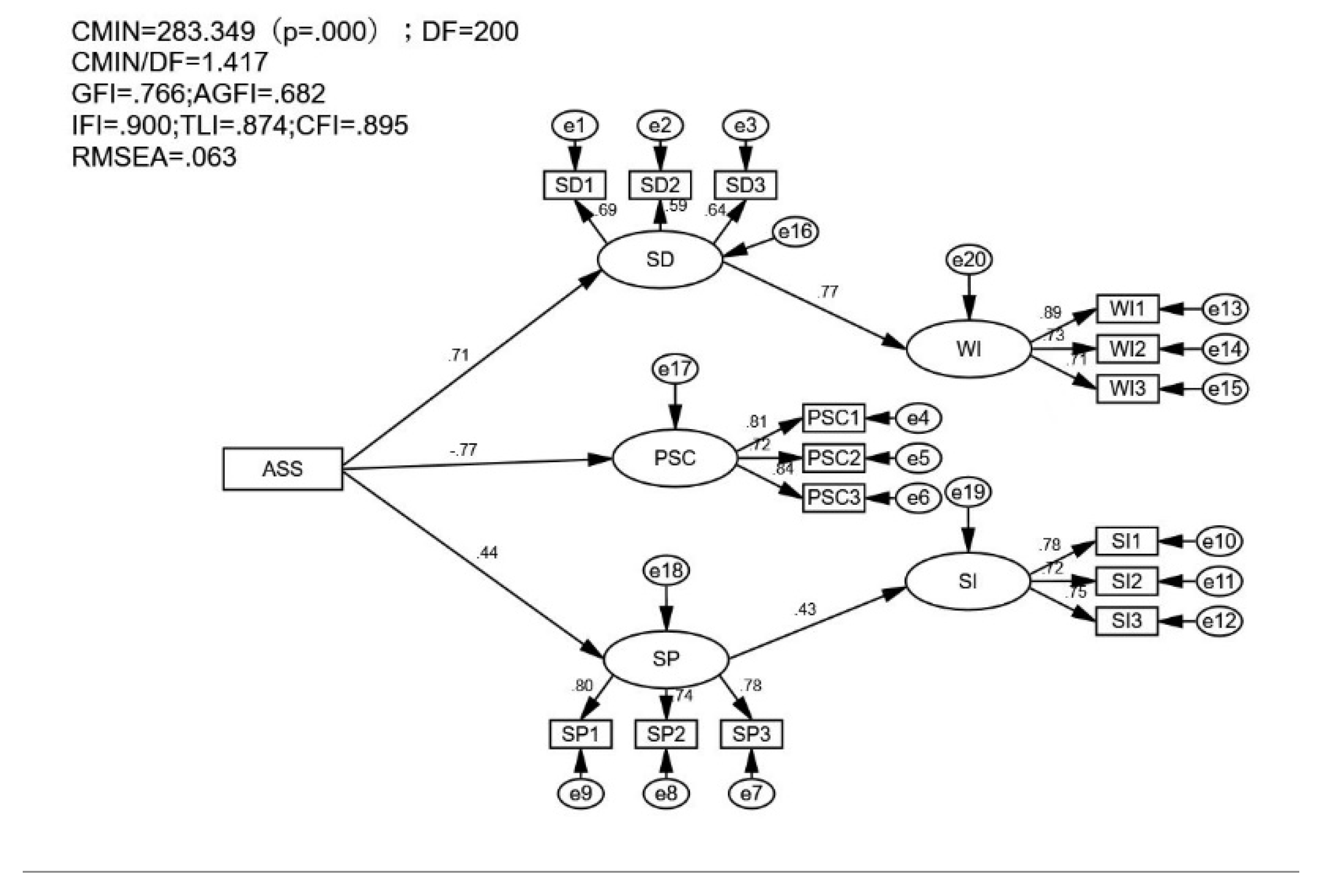

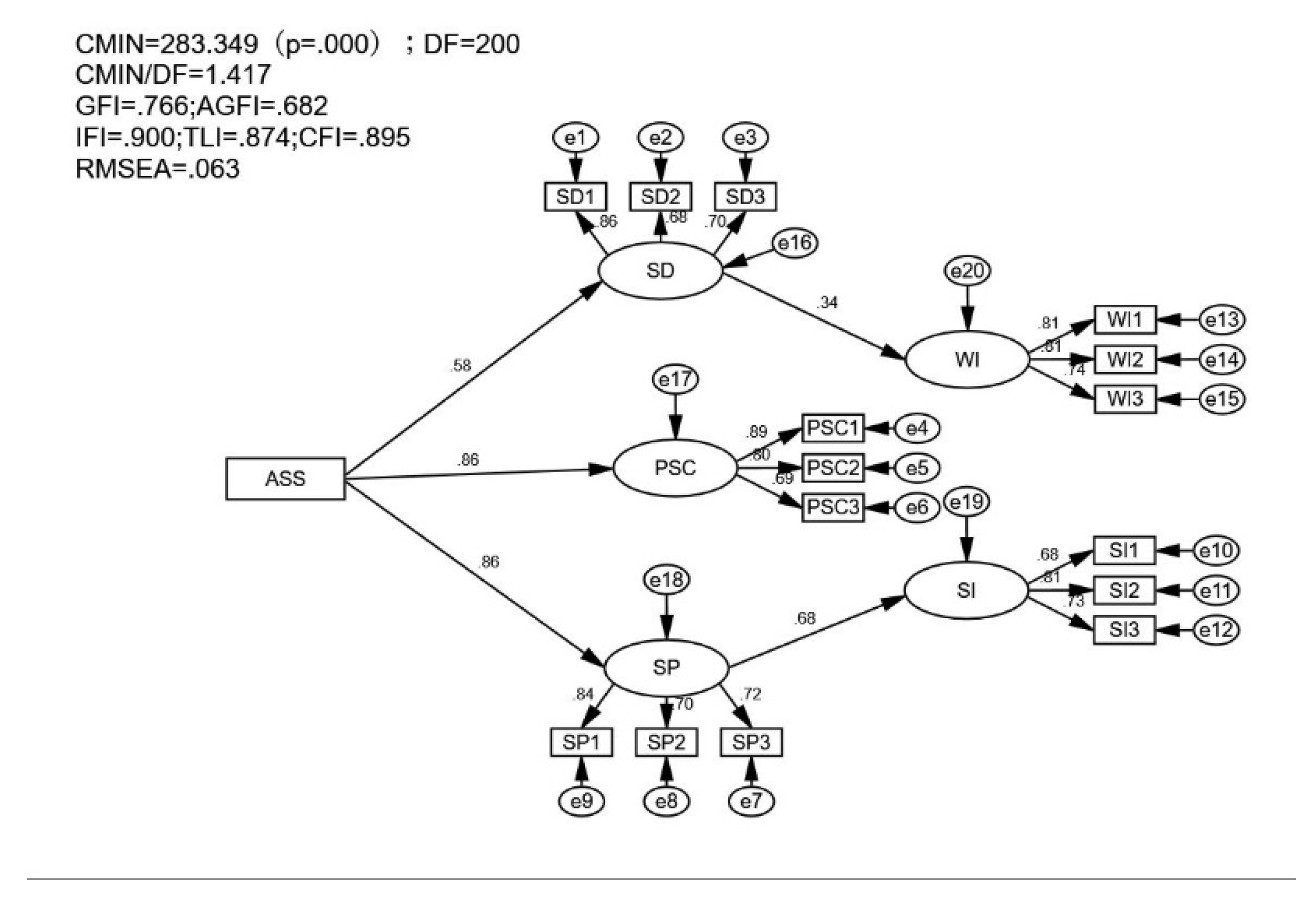

4.3. Structural Equation Modeling

4.4.1. The effect of avatar self-similarity on self-consciousness

4.4.2. The effect of avatar self-similarity on self-expression

4.4.3. The effect of self-expression on avatar identification

4.5. Independent sample t-test

4.5.1. T-test for avatar design element importance

4.5.2. T-test for manipulation duration of avatar design elements

5. Discussion

5.1. Findings and Theoretical Implications

5.1.1. Variations in avatar self-similarity across virtual contexts

5.1.2. The effect of avatar self-similarity on self-consciousness and self-expression

5.1.3. The effect of self-expression on avatar identification

5.1.4. Avatar customization and emotion expression

5.2. Research limitations

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Construct | Items | Wording | Source |

| Public self-consciousness | PSC1 PSC2 PSC3 |

I care about what other people think of my avatar I care what other people think of me I worry about others seeing my flaws |

Fenigstein A, Scheier MF, Buss AH. Public and private self-consciousness: Assessment and theory. J Consult Clin Psychol 1975; 43: 522–527. |

| Self-disclosure | SD1 SD2 SD3 |

I want to use this avatar to express my private side I want to express my true self with this avatar This avatar can show what I can't quite show in real life |

Hooi R, Cho H. Avatar-driven self-disclosure: The virtual me is the actual me. Comput Hum Behav 2014; 39: 20–28. |

| Self-presentation | SP1 SP2 SP3 |

This avatar represents a me in real life This avatar can introduce myself Anyone who sees this avatar will know it's me |

Kim H-W, Chan HC, Kankanhalli A. What Motivates People to Purchase Digital Items on Virtual Community Websites? The Desire for Online Self-Presentation. Inf Syst Res 2012; 23: 1232–1245. |

| Wishful identification | WI1 WI2 WI3 |

The avatar I created is my ideal self The avatars I create have the traits I would like to have This avatar is what I want to be |

Huffaker DA, Calvert SL. Gender, identity, and language use in teenage blogs. J Comput-Mediat Commun 2005; 10: JCMC10211 |

| Similarity identification | SI1 SI2 SI3 |

This avatar is related to who I am in real life This avatar looks a lot like me This avatar resembles me in many ways |

Takano M, Taka F. Fancy avatar identification and behaviors in the virtual world: Preceding avatar customization and succeeding communication. Comput Hum Behav Rep 2022; 6: 100176. |

References

- Lloyd D. In Touch with the Future: The Sense of Touch from Cognitive Neuroscience to Virtual Reality. Presence 2014; 23: 226–227. [CrossRef]

- Nowak KL, Fox J. Avatars and computer-mediated communication: a review of the definitions, uses, and effects of digital representations. Rev Commun Res 2018; 6: 30–53.

- Baccon LA, Chiarovano E, MacDougall HG. Virtual reality for teletherapy: Avatars may combine the benefits of face-to-face communication with the anonymity of online text-based communication. Cyberpsychology Behav Soc Netw 2019; 22: 158–165.

- Green-Hamann S, Campbell Eichhorn K, Sherblom JC. An exploration of why people participate in Second Life social support groups. J Comput-Mediat Commun 2011; 16: 465–491.

- Takano M, Tsunoda T. Self-disclosure of bullying experiences and social support in avatar communication: analysis of verbal and nonverbal communications. In: Proceedings of the International AAAI Conference on Web and Social Media. 2019: 473–481.

- Birk MV, Atkins C, Bowey JT, et al. Fostering Intrinsic Motivation through Avatar Identification in Digital Games. In: Proceedings of the 2016 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems. San Jose California USA: ACM; 2016: 2982–2995.

- Rahill KM, Sebrechts MM. Effects of Avatar player-similarity and player-construction on gaming performance. Comput Hum Behav Rep 2021; 4: 100131. [CrossRef]

- Steuer J. Defining Virtual Reality: Dimensions Determining Telepresence. J Commun 1992; 42: 73–93. [CrossRef]

- Liao G-Y, Cheng TCE, Teng C-I. How do avatar attractiveness and customization impact online gamers’ flow and loyalty? Internet Res 2019; 29: 349–366. [CrossRef]

- Fosslien L, Duffy MW. How to combat zoom fatigue. Harv Bus Rev 2020; 29: 1–6.

- Vasalou A, Joinson AN. Me, myself and I: The role of interactional context on self-presentation through avatars. Comput Hum Behav 2009; 25: 510–520. [CrossRef]

- Trepte S, Reinecke L, Behr K. Avatar creation and video game enjoyment: effects of life-satisfaction, game competitiveness, and identification with the avatar world. In: Annual Conference of the International Communication Association, Suntec, Singapore. 2010.

- Bailenson JN, Yee N, Merget D, et al. The effect of behavioral realism and form realism of real-time avatar faces on verbal disclosure, nonverbal disclosure, emotion recognition, and copresence in dyadic interaction. Presence Teleoperators Virtual Environ 2006; 15: 359–372.

- Hooi R, Cho H. Avatar-driven self-disclosure: The virtual me is the actual me. Comput Hum Behav 2014; 39: 20–28. [CrossRef]

- Takano M, Taka F. Fancy avatar identification and behaviors in the virtual world: Preceding avatar customization and succeeding communication. Comput Hum Behav Rep 2022; 6: 100176. [CrossRef]

- Olveres J, Billinghurst M, Savage J, et al. Intelligent, Expressive Avatars. : 9.

- Fabri M, Elzouki SYA, Moore D. Emotionally Expressive Avatars for Chatting, Learning and Therapeutic Intervention. In: Jacko JA, Hrsg. Human-Computer Interaction. HCI Intelligent Multimodal Interaction Environments. Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer; 2007: 275–285.

- Neviarouskaya A, Prendinger H, Ishizuka M. User study on AffectIM, an avatar-based Instant Messaging system employing rule-based affect sensing from text. Int J Hum-Comput Stud 2010; 68: 432–450. [CrossRef]

- Schroeder R. The social life of avatars: Presence and interaction in shared virtual environments. Springer Science & Business Media; 2001.

- Bailey R, Wise K, Bolls P. How avatar customizability affects children’s arousal and subjective presence during junk food–sponsored online video games. Cyberpsychol Behav 2009; 12: 277–283.

- Ducheneaut N, Wen M-H, Yee N, et al. Body and mind: a study of avatar personalization in three virtual worlds. In: Proceedings of the SIGCHI conference on human factors in computing systems. 2009: 1151–1160.

- Lim S, Reeves B. Being in the game: Effects of avatar choice and point of view on psychophysiological responses during play. Media Psychol 2009; 12: 348–370.

- Ratan RA, Hasler B. Designing the virtual self: How psychological connections to avatars may influence education-related outcomes of use. Proc First Immersive Educ Summit 2011; 28–29.

- Morie JF. The performance of the self and its effect on presence in virtual worlds. In: Proceedings of the 11th Annual International Workshop on Presence. 2008: 265–269.

- Huffaker DA, Calvert SL. Gender, identity, and language use in teenage blogs. J Comput-Mediat Commun 2005; 10: JCMC10211.

- Toma CL, Hancock JT, Ellison NB. Separating fact from fiction: An examination of deceptive self-presentation in online dating profiles. Pers Soc Psychol Bull 2008; 34: 1023–1036.

- Kim Y, Sundar SS. Visualizing ideal self vs. actual self through avatars: Impact on preventive health outcomes. Comput Hum Behav 2012; 28: 1356–1364. [CrossRef]

- Lin H, Wang H. Avatar creation in virtual worlds: Behaviors and motivations. Comput Hum Behav 2014; 34: 213–218.

- Cheng L, Farnham S, Stone L. Lessons learned: Building and deploying shared virtual environments. In: The social life of avatars. Springer; 2002: 90–111.

- Bainbridge WS. Leadership in science and technology: A reference handbook. Sage Publications; 2011.

- Vasalou A, Joinson AN, Pitt J. Constructing my online self: avatars that increase self-focused attention. In: Proceedings of the SIGCHI conference on Human factors in computing systems. 2007: 445–448.

- van der Land SF, Schouten AP, Feldberg F, et al. Does Avatar Appearance Matter? How Team Visual Similarity and Member-Avatar Similarity Influence Virtual Team Performance: Does Avatar Appearance Matter? Hum Commun Res 2015; 41: 128–153. [CrossRef]

- Robinson L. The cyberself: the self-ing project goes online, symbolic interaction in the digital age. New Media Soc 2007; 9: 93–110.

- Markus H, Nurius P. Possible selves. Am Psychol 1986; 41: 954.

- Govern JM, Marsch LA. Development and Validation of the Situational Self-Awareness Scale. Conscious Cogn 2001; 10: 366–378. [CrossRef]

- Fenigstein A, Scheier MF, Buss AH. Public and private self-consciousness: Assessment and theory. J Consult Clin Psychol 1975; 43: 522–527. [CrossRef]

- Williams D, Kennedy TL, Moore RJ. Behind the avatar: The patterns, practices, and functions of role playing in MMOs. Games Cult 2011; 6: 171–200.

- Goffman E. Presentation of self in everyday life. Am J Sociol 1949; 55: 6–7.

- Martey RM, Consalvo M. Performing the Looking-Glass Self: Avatar Appearance and Group Identity in Second Life. Pop Commun 2011; 9: 165–180. [CrossRef]

- Ślot K, Cichosz J, Bronakowski L. Emotion recognition with poincare mapping of voiced-speech segments of utterances. In: International Conference on Artificial Intelligence and Soft Computing. Springer; 2008: 886–895.

- Wu C-H, Yeh J-F, Chuang Z-J. Emotion Perception and Recognition from Speech. In: Tao J, Tan T, Hrsg. Affective Information Processing. London: Springer; 2009: 93–110.

- Maglogiannis I, Vouyioukas D, Aggelopoulos C. Face detection and recognition of natural human emotion using Markov random fields. Pers Ubiquitous Comput 2009; 13: 95–101.

- Rigas G, Katsis CD, Ganiatsas G, et al. A user independent, biosignal based, emotion recognition method. In: International Conference on User Modeling. Springer; 2007: 314–318.

- Fabri M, Moore DJ, Hobbs DJ. The Emotional Avatar: Non-verbal Communication Between Inhabitants of Collaborative Virtual Environments. In: Braffort A, Gherbi R, Gibet S, et al., Hrsg. Gesture-Based Communication in Human-Computer Interaction. Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer; 1999: 269–273.

- Yee N, Bailenson JN, Ducheneaut N. The Proteus Effect: Implications of Transformed Digital Self-Representation on Online and Offline Behavior. Commun Res 2009; 36: 285–312. [CrossRef]

- Yee N, Bailenson J. The Proteus Effect: The Effect of Transformed Self-Representation on Behavior. Hum Commun Res 2007; 33: 271–290. [CrossRef]

- Lee J-ER, Nass CI, Bailenson JN. Does the Mask Govern the Mind?: Effects of Arbitrary Gender Representation on Quantitative Task Performance in Avatar-Represented Virtual Groups. Cyberpsychology Behav Soc Netw 2014; 17: 248–254. [CrossRef]

- Ash E. Priming or Proteus Effect? Examining the Effects of Avatar Race on In-Game Behavior and Post-Play Aggressive Cognition and Affect in Video Games. Games Cult 2016; 11: 422–440. [CrossRef]

- Fox J, Ahn SJ. Avatars: Portraying, Exploring, and Changing Online and Offline Identities. Handb Res Technoself Identity Technol Soc 2013; 255–271. Im Internet: https://www.igi-global.com/chapter/content/www.igi-global.com/chapter/content/70358; Stand: 25.05.2022.

- Kao D. The effects of anthropomorphic avatars vs. non-anthropomorphic avatars in a jumping game. In: Proceedings of the 14th international conference on the foundations of digital games. 2019: 1–5.

- van Reijmersdal EA, Jansz J, Peters O, et al. Why girls go pink: Game character identification and game-players’ motivations. Comput Hum Behav 2013; 29: 2640–2649. [CrossRef]

- Messinger PR, Ge X, Smirnov K, et al. Reflections of the extended self: Visual self-representation in avatar-mediated environments. J Bus Res 2019; 100: 531–546. [CrossRef]

- Birk MV, Mandryk RL. Improving the efficacy of cognitive training for digital mental health interventions through avatar customization: crowdsourced quasi-experimental study. J Med Internet Res 2019; 21: e10133.

- Kao D, Harrell DF. The Effects of Badges and Avatar Identification on Play and Making in Educational Games. In: Proceedings of the 2018 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems. Montreal QC Canada: ACM; 2018: 1–19.

- Van Looy J, Courtois C, De Vocht M, et al. Player Identification in Online Games: Validation of a Scale for Measuring Identification in MMOGs. Media Psychol 2012; 15: 197–221. [CrossRef]

- Dunn RA, Guadagno RE. My avatar and me – Gender and personality predictors of avatar-self discrepancy. Comput Hum Behav 2012; 28: 97–106. [CrossRef]

- Kim H-W, Chan HC, Kankanhalli A. What Motivates People to Purchase Digital Items on Virtual Community Websites? The Desire for Online Self-Presentation. Inf Syst Res 2012; 23: 1232–1245. [CrossRef]

- Izard CE. The face of emotion. 1971;

- Ratan R, Sah YJ. Leveling up on stereotype threat: The role of avatar customization and avatar embodiment. Comput Hum Behav 2015; 50: 367–374. [CrossRef]

- MacKinnon DP, Lockwood CM, Williams J. Confidence Limits for the Indirect Effect: Distribution of the Product and Resampling Methods. Multivar Behav Res 2004; 39: 99–128. [CrossRef]

| variable | number of items | Cronbach α |

|---|---|---|

| Public self-consciousness | 3 | 0.837 |

| Self-disclosure | 3 | 0.763 |

| Self-presentation | 3 | 0.826 |

| Wishful identification | 3 | 0.812 |

| Similarity identification | 3 | 0.797 |

| latent variable | explicit variable | Coef. | SE | z | p | factor loading | AVE | CR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PSC | PSC1 | 1 | - | - | - | 0.845 | 0.633 | 0.838 |

| PSC2 | 0.936 | 0.122 | 7.699 | 0 | 0.775 | |||

| PSC3 | 0.928 | 0.121 | 7.638 | 0 | 0.765 | |||

| SD | SD1 | 1 | - | - | - | 0.811 | 0.533 | 0.773 |

| SD2 | 0.988 | 0.161 | 6.137 | 0 | 0.697 | |||

| SD3 | 0.914 | 0.152 | 6.006 | 0 | 0.674 | |||

| SP | SP1 | 1 | - | - | - | 0.818 | 0.612 | 0.825 |

| SP2 | 0.94 | 0.127 | 7.373 | 0 | 0.735 | |||

| SP3 | 0.986 | 0.126 | 7.823 | 0 | 0.792 | |||

| WI | WI1 | 1 | - | - | - | 0.846 | 0.614 | 0.826 |

| WI2 | 1.136 | 0.14 | 8.111 | 0 | 0.765 | |||

| WI3 | 1.15 | 0.148 | 7.778 | 0 | 0.735 | |||

| SI | SI1 | 1 | - | - | - | 0.718 | 0.569 | 0.798 |

| SI2 | 1.301 | 0.186 | 6.997 | 0 | 0.803 | |||

| SI3 | 1.197 | 0.18 | 6.634 | 0 | 0.739 |

| Factor1 | Factor2 | Factor3 | Factor4 | Factor5 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PSC | 0.795 | ||||

| SD | 0.005 | 0.724 | |||

| SP | 0.174 | 0.387 | 0.781 | ||

| WI | 0.02 | 0.413 | 0.372 | 0.773 | |

| SI | 0.128 | 0.286 | 0.41 | 0.573 | 0.758 |

| source of difference | sum of square | df | mean square | F | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept | 5158.512 | 1 | 5158.512 | 488.988 | 0.000*** |

| gender | 23.964 | 1 | 23.964 | 2.272 | 0.135 |

| context | 333.486 | 1 | 333.486 | 31.612 | 0.000*** |

| gender * context | 51.921 | 1 | 51.921 | 4.922 | 0.029* |

| Residual | 1076.034 | 102 | 10.549 | ||

| R ²: 0.255 | |||||

| Note. * p<0.05 ** p<0.01 *** p<0.001 | |||||

| MOSG (n=52) |

VM (n=54) |

mean difference | SE | t | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male | 5.29±1.69 | 10.56±5.00 | -5.261 | 1.098 | -4.79 | 0 |

| Female | 5.77±2.22 | 8.06±3.54 | -2.284 | 0.771 | -2.963 | 0.004 |

| Path | MOSG | VM | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Path Coefficient β |

T Statistics |

Path Coefficient β |

T Statistics | |||

| ASS | → | SD | 0.712*** | 4.335 | 0.579*** | 4.313 |

| ASS | → | SP | 0.442** | 2.955 | 0.865*** | 5.939 |

| ASS | → | PSC | -0.768*** | -5.923 | 0.864*** | 8.753 |

| SP | → | SI | 0.427* | 2.41 | 0.676*** | 3.464 |

| SD | → | WI | 0.769*** | 4.016 | 0.339* | 2.043 |

| Context (mean ± standard deviation) | t | p | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MOSG(n=52) | VM(n=54) | |||

| Gender | 3.73±0.95 | 3.67±1.29 | 0.292 | 0.771 |

| Skin color | 3.73±0.82 | 3.67±1.06 | 0.348 | 0.728 |

| Eye color | 3.65±1.05 | 3.44±1.08 | 1.016 | 0.312 |

| Face shape | 3.58±0.89 | 3.44±0.92 | 0.750 | 0.455 |

| Eyes | 3.31±0.96 | 3.26±0.89 | 0.269 | 0.789 |

| Nose | 3.27±0.91 | 3.26±0.89 | 0.057 | 0.955 |

| mouth | 3.12±1.02 | 3.30±0.94 | -0.947 | 0.346 |

| Eyebrows | 3.27±1.03 | 3.41±1.07 | -0.676 | 0.501 |

| Hairstyle | 4.37±0.82 | 2.61±1.50 | 7.524 | 0.000*** |

| Makeup | 4.13±0.79 | 2.48±1.42 | 7.420 | 0.000*** |

| Beard | 2.62±1.16 | 2.96±1.27 | -1.469 | 0.145 |

| Clothing | 4.58±0.70 | 4.19±1.03 | 2.287 | 0.024* |

| Props | 3.62±1.29 | 2.59±1.21 | 4.226 | 0.000*** |

| Context (mean ± standard deviation) | t | p | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MOSG(n=52) | VM(n=54) | |||

| Gender | 1.85±0.87 | 1.37±0.78 | 2.950 | 0.004** |

| Skin color | 2.73±1.17 | 1.89±0.88 | 4.162 | 0.000*** |

| Eye color | 3.04±1.20 | 2.00±0.91 | 4.994 | 0.000*** |

| Face shape | 3.08±0.93 | 2.59±0.79 | 2.902 | 0.005** |

| Eyes | 2.65±0.84 | 2.52±0.88 | 0.808 | 0.421 |

| Nose | 2.54±0.80 | 2.41±0.79 | 0.847 | 0.399 |

| Mouth | 2.50±0.75 | 2.44±0.88 | 0.348 | 0.729 |

| Eyebrows | 2.65±0.84 | 2.52±0.97 | 0.769 | 0.443 |

| Hairstyle | 4.31±0.78 | 3.04±1.18 | 6.509 | 0.000*** |

| Makeup | 4.50±0.75 | 2.63±1.03 | 10.611 | 0.000*** |

| Beard | 2.00±1.01 | 1.96±1.12 | 0.179 | 0.858 |

| Clothing | 4.15±1.18 | 3.59±1.07 | 2.566 | 0.012* |

| Props | 3.50±1.57 | 2.00±1.03 | 5.808 | 0.000*** |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).