Submitted:

02 May 2023

Posted:

03 May 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Strains used in this study

2.2. Time-scaled phylogenetic analyses

2.3. Phylogenetic distance analyses

2.4. Phylodynamic analyses

2.5. Selective pressure analyses

2.6. Construction of the 3D structure of RdRp and VP1 proteins

2.7. Conformational B-cell epitope prediction

3. Results

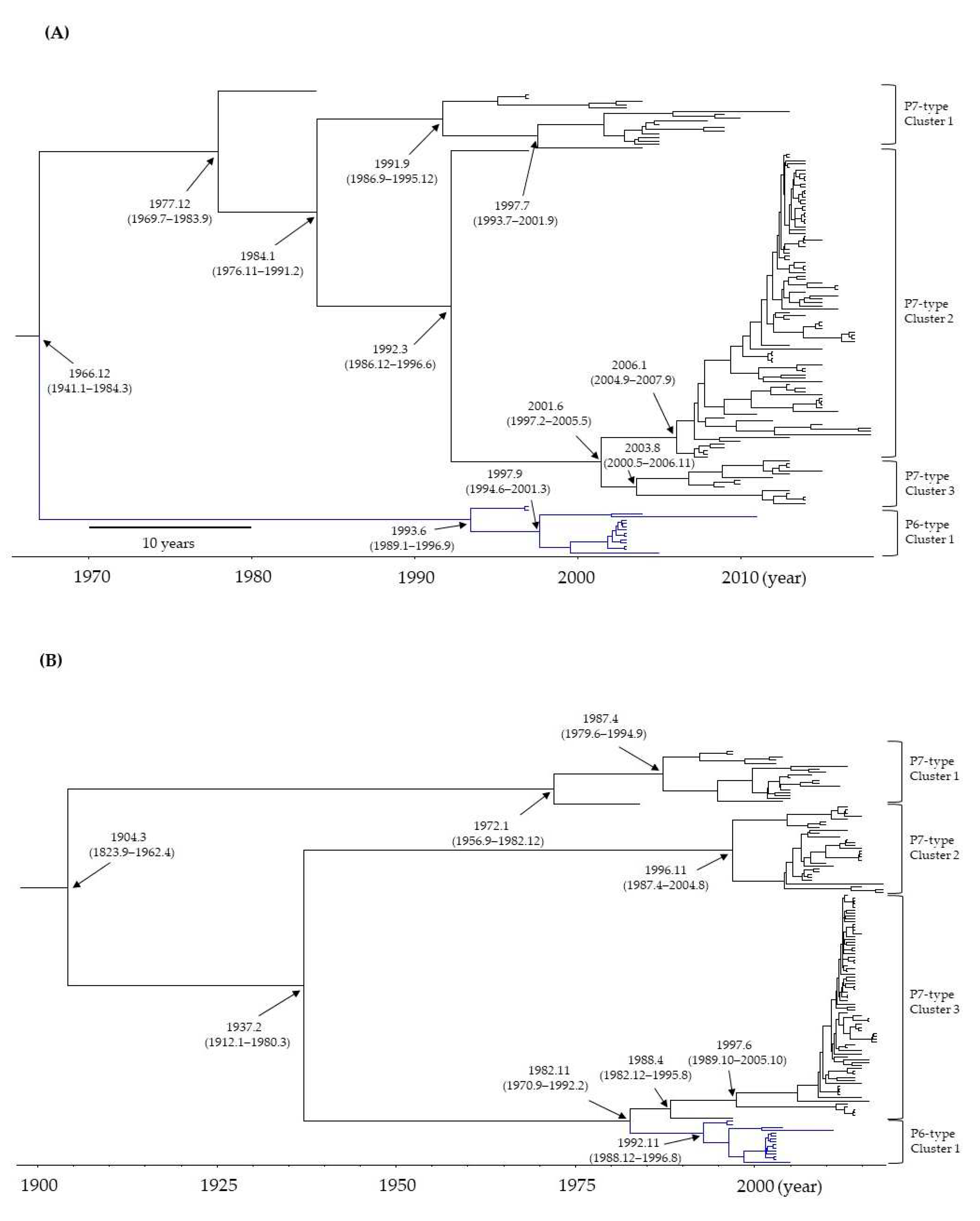

3.1. Time-scaled phylogeny of the RdRp region and VP1 gene in HuNoV GII.P6-GII.6 and GII.P7-GII.6

3.2. Evolutionary rates of the RdRp region and VP1 gene in HuNoV GII.P6-GII.6 and GII.P7-GII.6

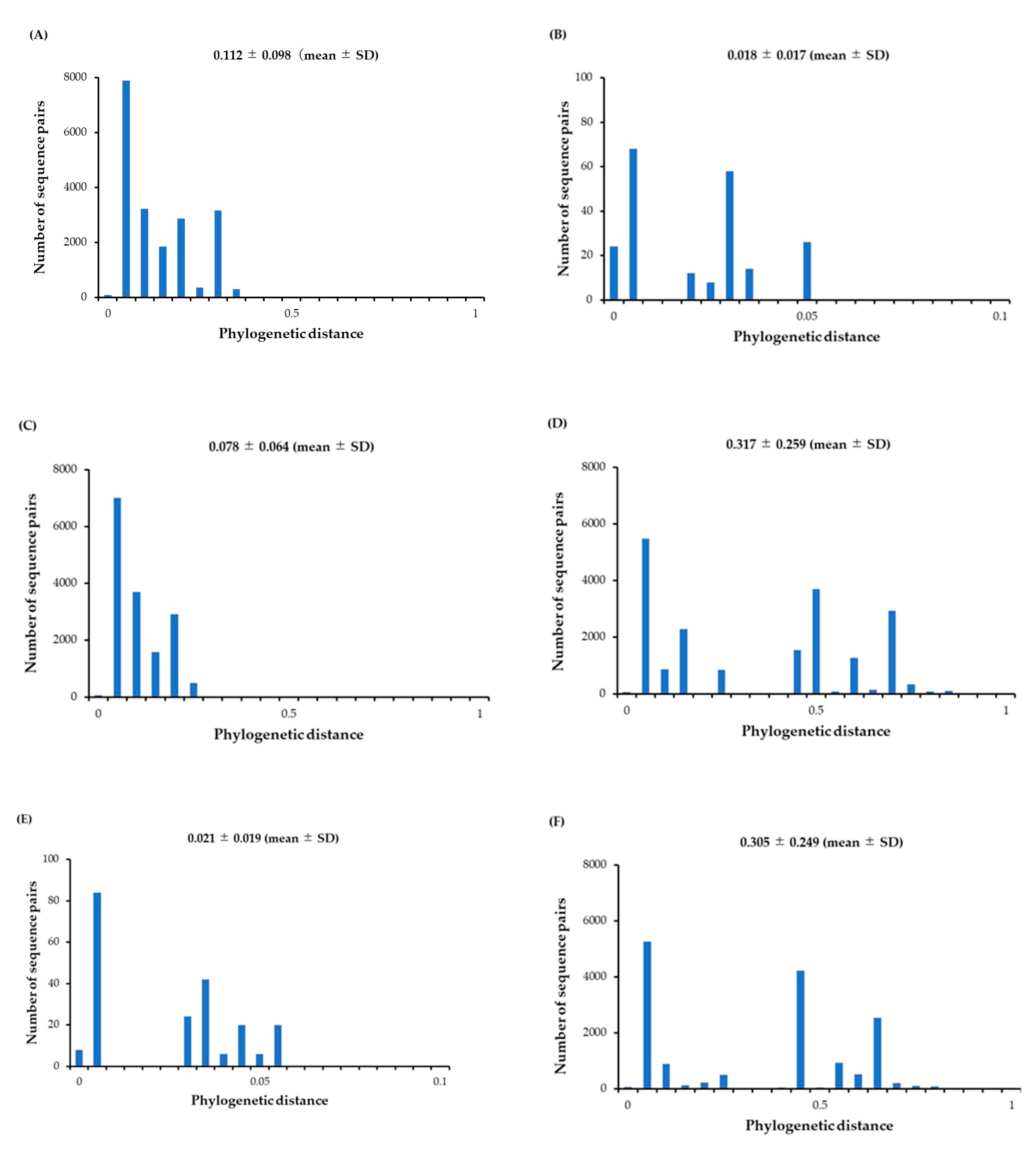

3.3. Phylogenetic distances among the present strains

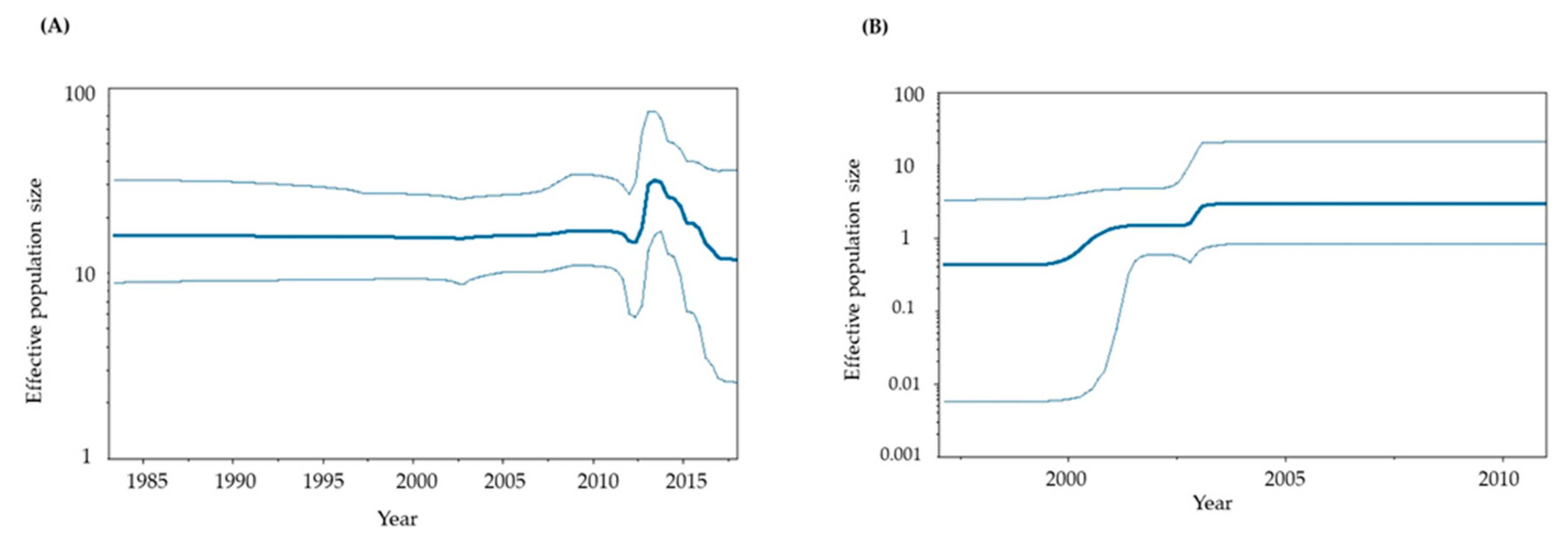

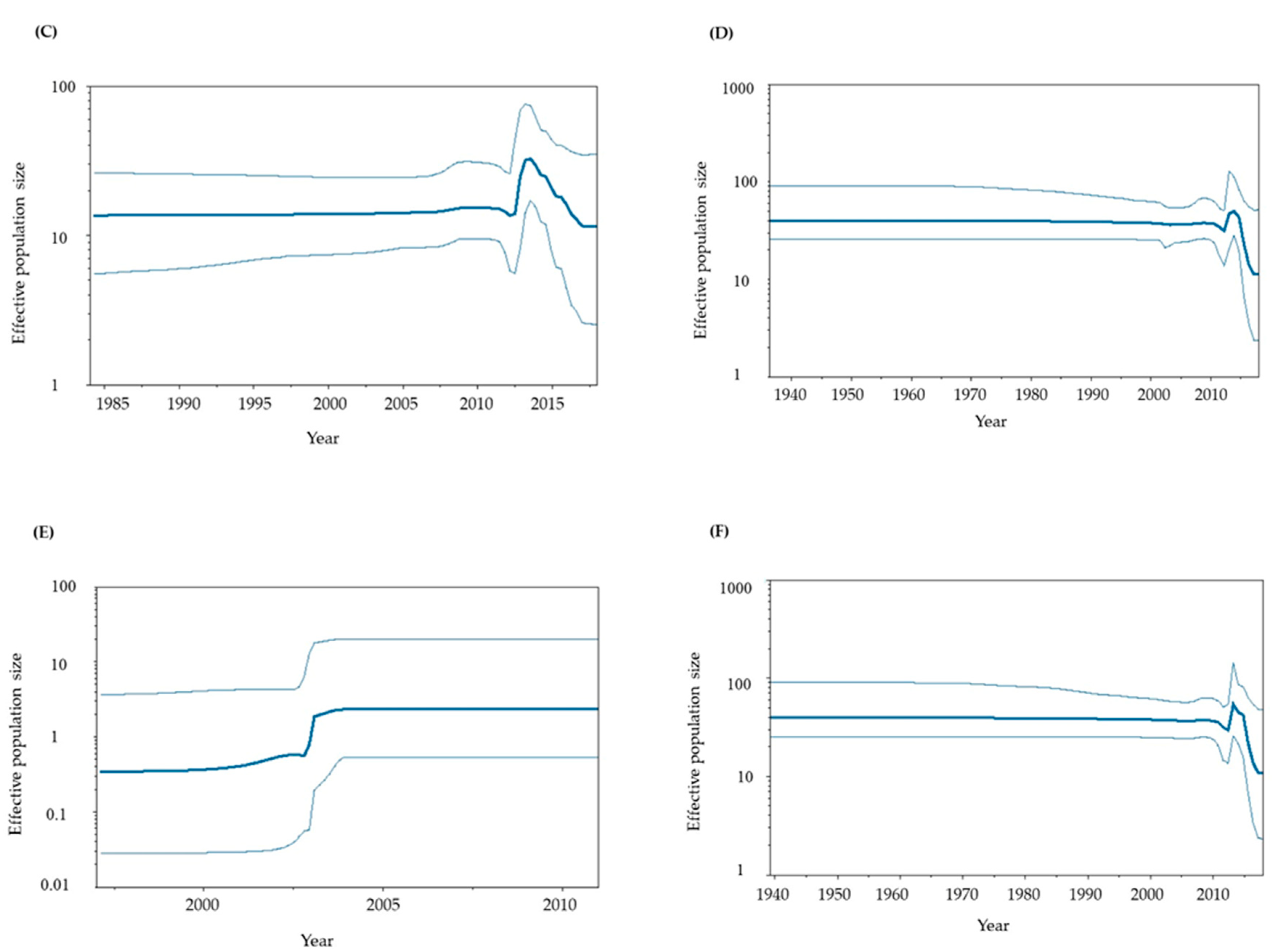

3.4. Phylodynamics of GII.P6-GII.6 and GII.P7-GII.6

3.5. Positive selection sites in the VP1 protein

3.6. Negative selection sites in RdRp and VP1 proteins

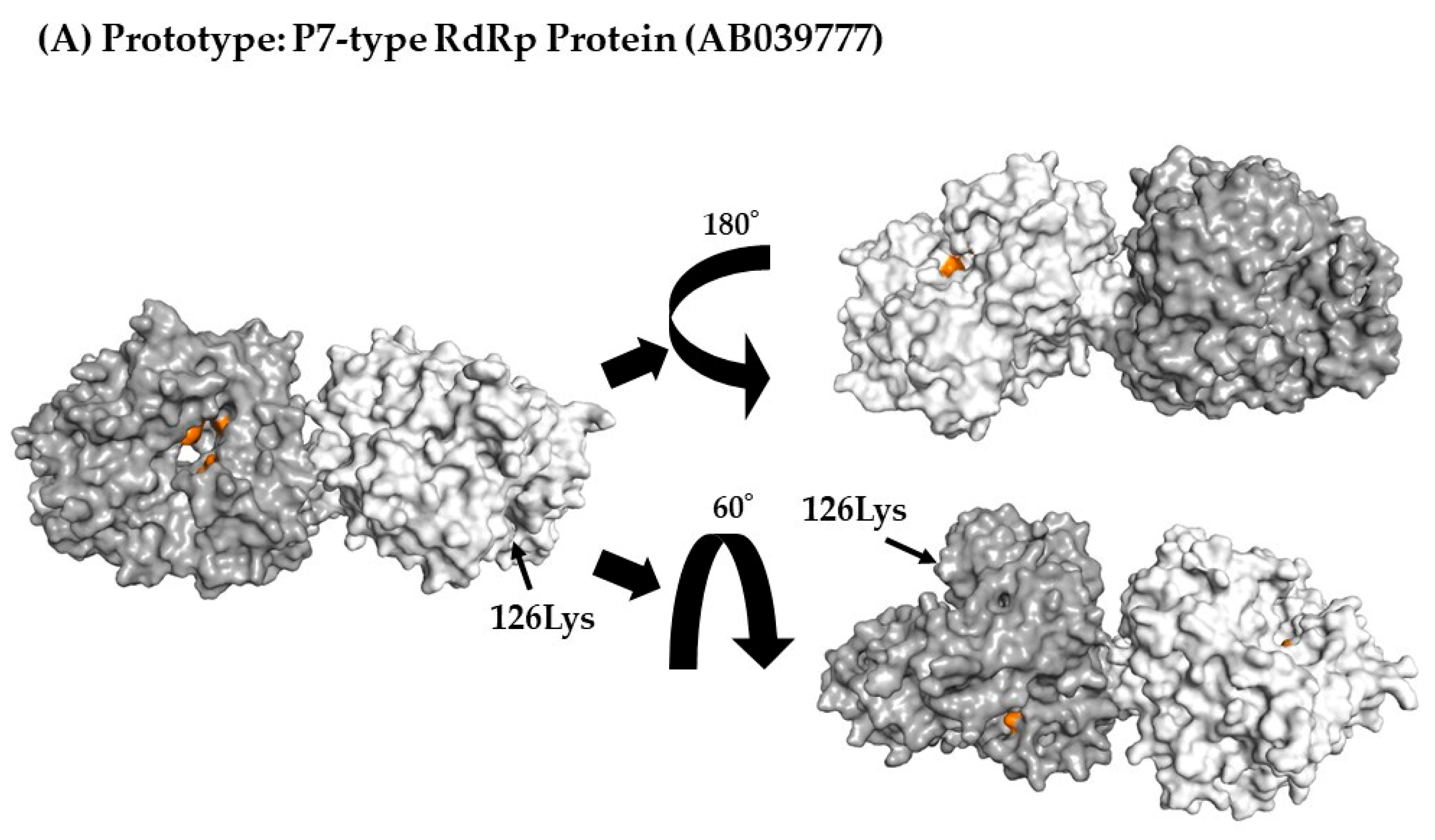

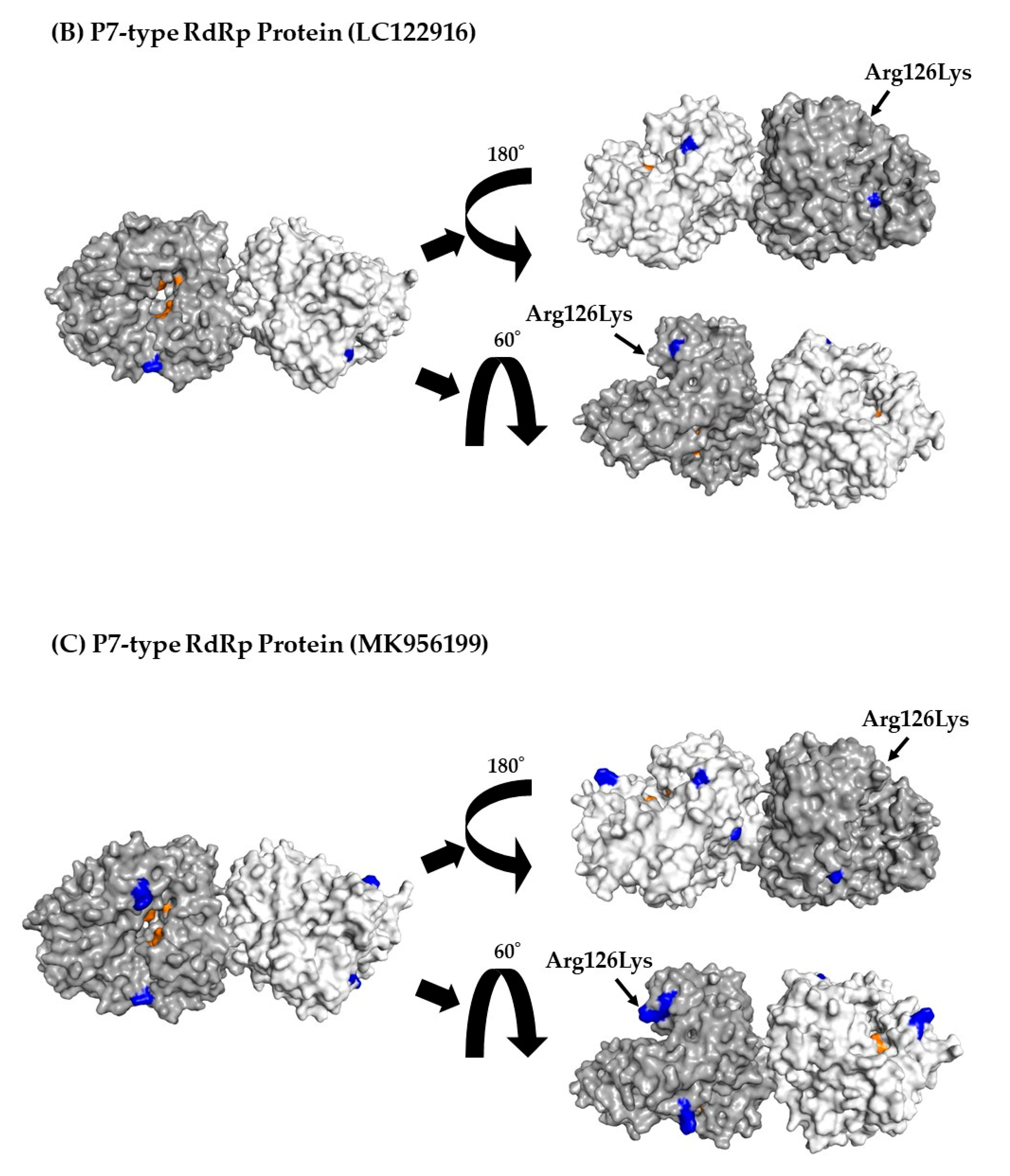

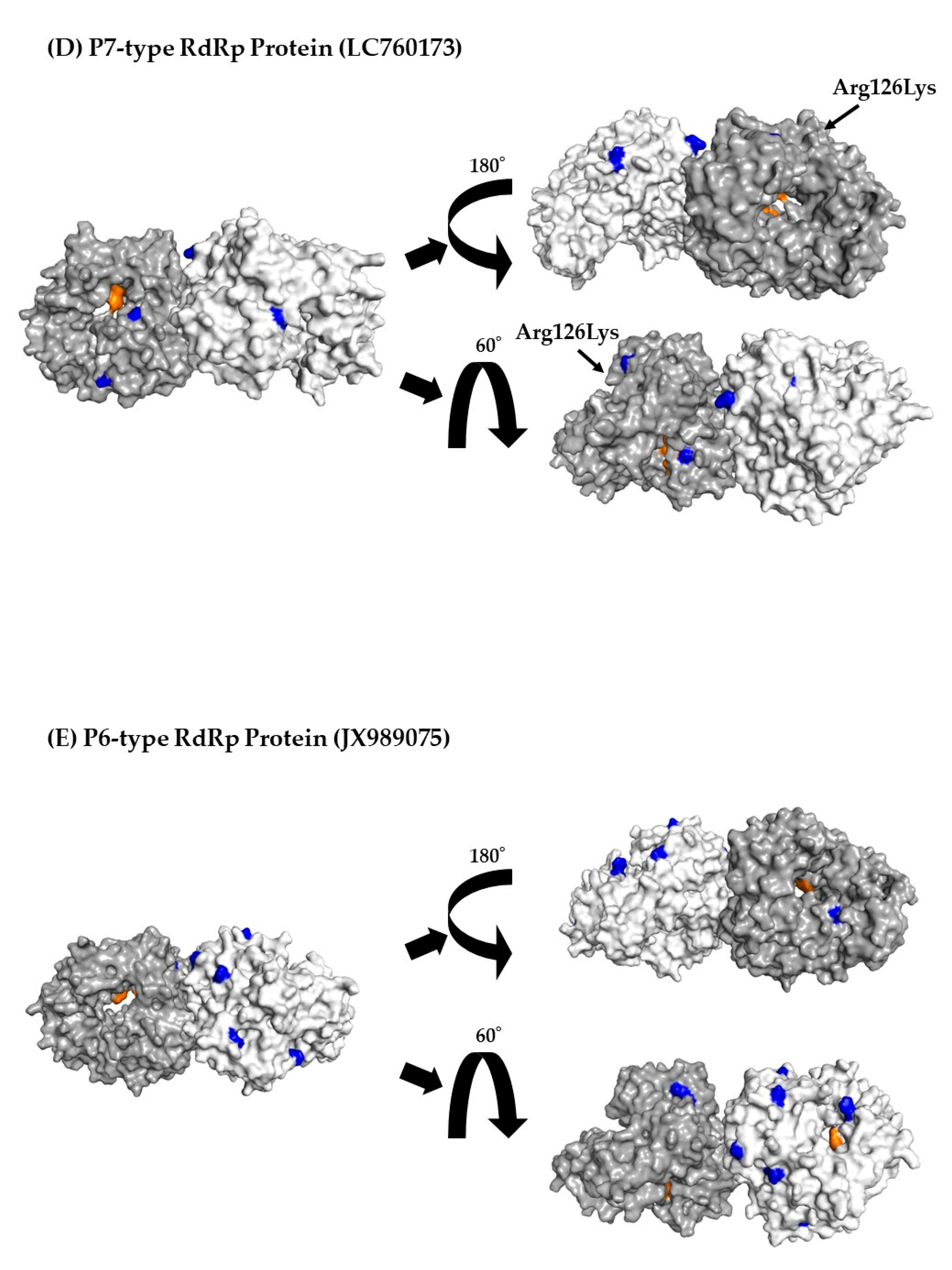

3.7. 3D mapping relationships between amino acid substitutions and active sites of the RdRp dimer proteins

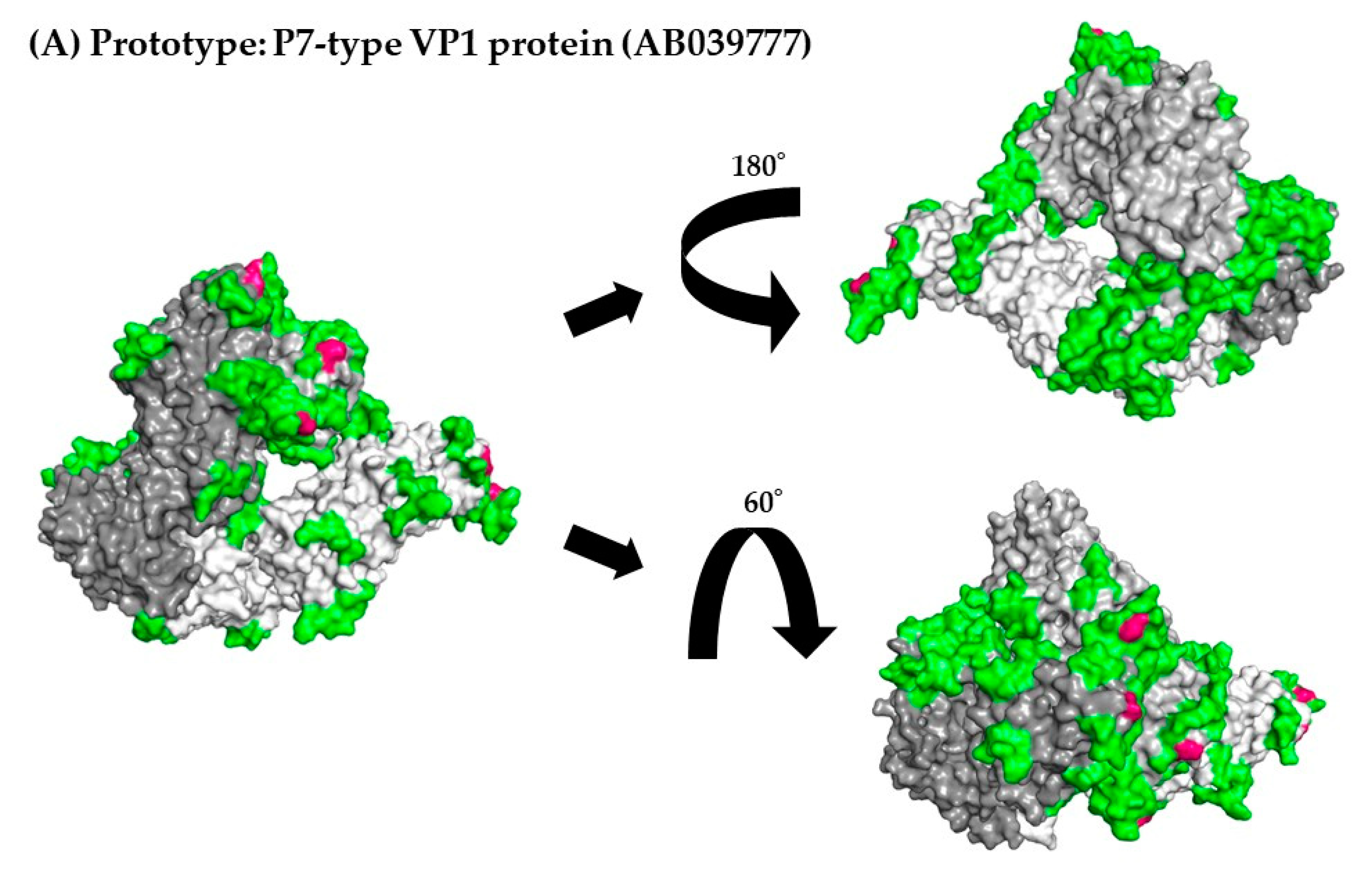

3.8. 3D mapping of the positive selection sites and conformational epitopes in the VP1 trimer proteins

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Robilotti, E.; Deresinski, S.; Pinsky, B.A. Norovirus. CLINICAL MICROBIOLOGY REVIEWS 2015, 28, 134–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mans, J. Norovirus Infections and Disease in Lower-MiddleandLow-Income Countries, 1997⁻2018. Viruses 2019, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan-It, W.; Thongprachum, A.; Khamrin, P.; Kobayashi, M.; Okitsu, S.; Mizuguchi, M.; Ushijima, H. Emergence of a new norovirus GII.6 variant in Japan, 2008-2009. J. Med. Virol. 2012, 84, 1089–1096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, M.M.; Hall, A.J.; Vinjé, J.; Parashar, U.D. Noroviruses: a comprehensive review. J. Clin. Virol. 2009, 44, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patel, M.M.; Widdowson, M.A.; Glass, R.I.; Akazawa, K.; Vinjé, J.; Parashar, U.D. Systematic literature review of role of noroviruses in sporadic gastroenteritis. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2008, 14, 1224–1231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parrón, I.; Álvarez, J.; Jané, M.; Cornejo Sánchez, T.; Razquin, E.; Guix, S.; Camps, G.; Pérez, C.; Domínguez, À.; Catalonia, W.G.f.t.S.o.O.o.A.G.i. A foodborne norovirus outbreak in a nursing home and spread to staff and their household contacts. Epidemiol. Infect. 2019, 147, e225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winder, N.; Gohar, S.; Muthana, M. Norovirus: An Overview of Virology and Preventative Measures. Viruses 2022, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Graaf, M.; van Beek, J.; Koopmans, M.P. Human norovirus transmission and evolution in a changing world. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2016, 14, 421–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, X.; Wang, M.; Wang, K.; Estes, M.K. Sequence and genomic organization of Norwalk virus. Virology 1993, 195, 51–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chhabra, P.; de Graaf, M.; Parra, G.I.; Chan, M.C.; Green, K.; Martella, V.; Wang, Q.; White, P.A.; Katayama, K.; Vennema, H.; et al. Updated classification of norovirus genogroups and genotypes. J. Gen. Virol. 2019, 100, 1393–1406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, X.; Espul, C.; Zhong, W.M.; Cuello, H.; Matson, D.O. Characterization of a novel human calicivirus that may be a naturally occurring recombinant. Arch. Virol. 1999, 144, 2377–2387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ludwig-Begall, L.F.; Mauroy, A.; Thiry, E. Norovirus recombinants: recurrent in the field, recalcitrant in the lab - a scoping review of recombination and recombinant types of noroviruses. J. Gen. Virol. 2018, 99, 970–988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kroneman, A.; Vega, E.; Vennema, H.; Vinjé, J.; White, P.A.; Hansman, G.; Green, K.; Martella, V.; Katayama, K.; Koopmans, M. Proposal for a unified norovirus nomenclature and genotyping. Arch. Virol. 2013, 158, 2059–2068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Beek, J.; de Graaf, M.; Al-Hello, H.; Allen, D.J.; Ambert-Balay, K.; Botteldoorn, N.; Brytting, M.; Buesa, J.; Cabrerizo, M.; Chan, M.; et al. Molecular surveillance of norovirus, 2005-16: an epidemiological analysis of data collected from the NoroNet network. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2018, 18, 545–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khamrin, P.; Kumthip, K.; Yodmeeklin, A.; Jampanil, N.; Phengma, P.; Yamsakul, P.; Okitsu, S.; Kobayashi, T.; Ushijima, H.; Maneekarn, N. Changing Predominance of Norovirus Recombinant Strains GII.2[P16] to GII.4[P16] and GII.4[P31] in Thailand, 2017 to 2018. Microbiol. Spectr. 2022, 10, e0044822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pybus, O.G.; Rambaut, A. Evolutionary analysis of the dynamics of viral infectious disease. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2009, 10, 540–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matsushima, Y.; Mizukoshi, F.; Sakon, N.; Doan, Y.H.; Ueki, Y.; Ogawa, Y.; Motoya, T.; Tsukagoshi, H.; Nakamura, N.; Shigemoto, N.; et al. Evolutionary Analysis of the VP1 and RNA-Dependent RNA Polymerase Regions of Human Norovirus GII.P17-GII.17 in 2013–2017. Front. Microbiol. 2019, 10, 2189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mizukoshi, F.; Nagasawa, K.; Doan, Y.H.; Haga, K.; Yoshizumi, S.; Ueki, Y.; Shinohara, M.; Ishikawa, M.; Sakon, N.; Shigemoto, N.; et al. Molecular Evolution of the RNA-Dependent RNA Polymerase and Capsid Genes of Human Norovirus Genotype GII.2 in Japan during 2004-2015. Front. Microbiol. 2017, 8, 705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagasawa, K.; Matsushima, Y.; Motoya, T.; Mizukoshi, F.; Ueki, Y.; Sakon, N.; Murakami, K.; Shimizu, T.; Okabe, N.; Nagata, N.; et al. Phylogeny and Immunoreactivity of Norovirus GII.P16-GII.2, Japan, Winter 2016-17. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2018, 24, 144–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouckaert, R.; Heled, J.; Kühnert, D.; Vaughan, T.; Wu, C.-H.; Xie, D.; Suchard, M.A.; Rambaut, A.; Drummond, A.J. BEAST 2: a software platform for Bayesian evolutionary analysis. PLOS COMPUTATIONAL BIOLOGY 2014, 10, e1003537–e1003537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saito, M.; Tsukagoshi, H.; Sada, M.; Sunagawa, S.; Shirai, T.; Okayama, K.; Sugai, T.; Tsugawa, T.; Hayashi, Y.; Ryo, A.; et al. Detailed Evolutionary Analyses of the F Gene in the Respiratory Syncytial Virus Subgroup A. Viruses 2021, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darriba, D.; Taboada, G.L.; Doallo, R.; Posada, D. jModelTest 2: more models, new heuristics and parallel computing. Nat. Methods. 2012, 9, 772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kanda, Y. (2013). Investigation of the freely available easy-to-use software ‘EZR’ for medical statistics. Bone Marrow Transplant. 48 452–458. [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Stecher, G.; Tamura, K. MEGA7: Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis Version 7.0 for Bigger Datasets. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2016, 33, 1870–1874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fourment, M. , Gibbs, M.J. (2006). PATRISTIC: a program for calculating patristic distances and graphically comparing the components of genetic change. BMC Evol. Biol. 2006, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rambaut, A.; Drummond, A.J.; Xie, D.; Baele, G.; Suchard, M.A. Posterior Summarization in Bayesian Phylogenetics Using Tracer 1.7. Syst. Biol. 2018, 67, 901–904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weaver, S.; Shank, S.D.; Spielman, S.J.; Li, M.; Muse, S.V.; Kosakovsky Pond, S.L. Datamonkey 2.0: A Modern Web Application for Characterizing Selective and Other Evolutionary Processes. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2018, 35, 773–777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Webb, B.; Sali, A. Protein structure modeling with MODELLER. Methods Mol. Biol. 2014, 1137, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emsley, P.; Lohkamp, B.; Scott, W.G.; Cowtan, K. Features and development of Coot. Acta. Crystallogr. D. Biol. Crystallogr. 2010, 66, 486–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guex, N.; Peitsch, M.C. SWISS-MODEL and the Swiss-PdbViewer: an environment for comparative protein modeling. Electrophoresis 1997, 18, 2714–2723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kringelum, J.V.; Lundegaard, C.; Lund, O.; Nielsen, M. Reliable B cell epitope predictions: impacts of method development and improved benchmarking. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2012, 8, e1002829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ponomarenko, J.; Bui, H.H.; Li, W.; Fusseder, N.; Bourne, P.E.; Sette, A.; Peters, B. ElliPro: a new structure-based tool for the prediction of antibody epitopes. BMC Bioinformatics 2008, 9, 514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shashkova, T.I.; Umerenkov, D.; Salnikov, M.; Strashnov, P.V.; Konstantinova, A.V.; Lebed, I.; Shcherbinin, D.N.; Asatryan, M.N.; Kardymon, O.L.; Ivanisenko, N.V. SEMA: Antigen B-cell conformational epitope prediction using deep transfer learning. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 960985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, C.; Chen, Z.; Zhang, L.; Yan, D.; Mao, T.; Tang, K.; Qiu, T.; Cao, Z. SEPPA 3.0-enhanced spatial epitope prediction enabling glycoprotein antigens. Nucleic. Acids. Res. 2019, 47, W388–W394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozaki, K.; Matsushima, Y.; Nagasawa, K.; Motoya, T.; Ryo, A.; Kuroda, M.; Katayama, K.; Kimura, H. Molecular Evolutionary Analyses of the RNA-Dependent RNA Polymerase Region in Norovirus Genogroup II. Front. Microbiol. 2018, 9, 3070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bidalot, M.; Théry, L.; Kaplon, J.; De Rougemont, A.; Ambert-Balay, K. Emergence of new recombinant noroviruses GII.p16-GII.4 and GII.p16-GII.2, France, winter 2016 to 2017. Euro. Surveill. 2017, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ao, Y.; Wang, J.; Ling, H.; He, Y.; Dong, X.; Wang, X.; Peng, J.; Zhang, H.; Jin, M.; Duan, Z. Norovirus GII.P16/GII.2-Associated Gastroenteritis, China, 2016. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2017, 23, 1172–1175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, L.T.; Kuo, T.Y.; Wu, C.Y.; Liao, W.T.; Hall, A.J.; Wu, F.T. Recombinant GII.P16-GII.2 Norovirus, Taiwan, 2016. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2017, 23, 1180–1183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siebenga, J.J.; Vennema, H.; Zheng, D.P.; Vinjé, J.; Lee, B.E.; Pang, X.L.; Ho, E.C.; Lim, W.; Choudekar, A.; Broor, S.; et al. Norovirus illness is a global problem: emergence and spread of norovirus GII.4 variants, 2001-2007. J. Infect. Dis. 2009, 200, 802–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vinjé, J. Advances in laboratory methods for detection and typing of norovirus. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2015, 53, 373–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eden, J.S.; Tanaka, M.M.; Boni, M.F.; Rawlinson, W.D.; White, P.A. Recombination within the pandemic norovirus GII.4 lineage. J. Virol. 2013, 87, 6270–6282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kobayashi, M.; Matsushima, Y.; Motoya, T.; Sakon, N.; Shigemoto, N.; Okamoto-Nakagawa, R.; Nishimura, K.; Yamashita, Y.; Kuroda, M.; Saruki, N.; et al. Molecular evolution of the capsid gene in human norovirus genogroup II. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 29400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bull, R.A.; Eden, J.S.; Rawlinson, W.D.; White, P.A. Rapid evolution of pandemic noroviruses of the GII.4 lineage. PLoS Pathog. 2010, 6, e1000831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hutson, A.M.; Atmar, R.L.; Marcus, D.M.; Estes, M.K. Norwalk virus-like particle hemagglutination by binding to h histo-blood group antigens. J. Virol. 2003, 77, 405–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schroten, H.; Hanisch, F.G.; Hansman, G.S. Human Norovirus Interactions with Histo-Blood Group Antigens and Human Milk Oligosaccharides. J. Virol. 2016, 90, 5855–5859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holmes, E.C. Virus evolution. In Fields Virology, 6th ed.; Knipe, D.M., Howley, P.M., Cohen, J.I., Griffin, D.E., Lamb, R.A., Martin, M.A., Racaniello, V.D., Roizman, B., Eds.; Lippincott Williams & Wilkins: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2013; Volume 1, pp. 286–313. [Google Scholar]

- Lindesmith, L.C.; Donaldson, E.; Leon, J.; Moe, C.L.; Frelinger, J.A.; Johnston, R.E.; Weber, D.J.; Baric, R.S. Heterotypic humoral and cellular immune responses following Norwalk virus infection. J. Virol. 2010, 84, 1800–1815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Region/gene | Evolutionary rates (95% HPDs) (substitutions/site/year) |

Compared groups and statistical values |

|---|---|---|

| All RdRp region (141 strains) P6-type 15 strains; P7-type 126 strains |

3.287 × 10-3 (2.489 × 10-3–4.098 × 10-3) | All RdRp region VS All GII.6 VP1 gene p < 0.001 |

| All GII.6 VP1 gene (141 strains) P6-type 15 strains; P7-type 126 strains |

3.345 × 10-3 (2.295 × 10-3–4.419 × 10-3) | |

| P6-type RdRp region (15 strains) | 5.063 × 10-3 (3.525 × 10-3–6.595 × 10-3) | P6-type RdRp region VS P7-type RdRp region p < 0.001 |

| P7-type RdRp region (126 strains) | 3.022 × 10-3 (2.268 × 10-3–3.775 × 10-3) | |

| GII.P6-GII.6 VP1 gene (15 strains) | 3.725 × 10-3 (1.843 × 10-3–5.549 × 10-3) | GII.P6-GII.6 VP1 gene VS GII. P7-GII.6 VP1 gene p < 0.001 |

| GII.P7-GII.6 VP1 gene (126 strains) | 3.482 × 10-3 (2.419 × 10-3–4.568 × 10-3) |

| Region/gene | Phylogenetic distance (mean ± SD) |

Compared groups and statistical values |

|---|---|---|

| All RdRp region (141 strains) P6-type 15 strains; P7-type 126 strains |

0.112 ± 0.098 | All RdRp region VS ALL GII.6 VP1 gene p < 0.001 |

| All GII.6 VP1 gene (141 strains) P6-type 15 strains; P7-type 126 strains |

0.317 ± 0.259 | |

| P6-type RdRp region (15 strains) | 0.018 ± 0.017 | P6 type RdRp region VS P7 type RdRp region p < 0.001 |

| P7-type RdRp region (126 strains) | 0.078 ± 0.064 | |

| GII.P6-GII.6 VP1 gene (15 strains) | 0.021 ± 0.019 | GII.P6-GII.6 VP1 gene VS GII. P7-GII.6 VP1 gene p < 0.001 |

| GII.P7-GII.6 VP1 gene (126 strains) | 0.305 ± 0.249 |

| Region/gene | Number of negative selection sites |

Number of positive selection sites |

Estimated as positive selective sites |

|---|---|---|---|

| P6 type and P7 type RdRp region |

258 | 0 | — |

| P6 type RdRp region | 3 | 0 | — |

| P7 type RdRp region | 205 | 1 | 126Lys, Lys126Arg |

| GII.P6-GII.6 and GII.P7-GII.6 VP1 gene |

298 | 2 | 354Pro, 390Asn |

| GII.P6-GII.6 VP1 gene | 8 | 1 | Lys386His |

| GII.P7-GII.6 VP1 gene | 274 | 2 | Pro354Thr, Ser and Gln, Asn390Thr and Asp |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).