Submitted:

03 May 2023

Posted:

04 May 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study area

2.2. Sampling and sample size

- n = required sampling size

- N = population size

- ∝ = 1-confidence level

- D = estimated minimum number of positive samples

2.3. Influenza A virus detection

2.4. Sequencing and phylogenic analysis

2.5. Ecological and environmental variables

2.6. Statistical analysis

3. Results

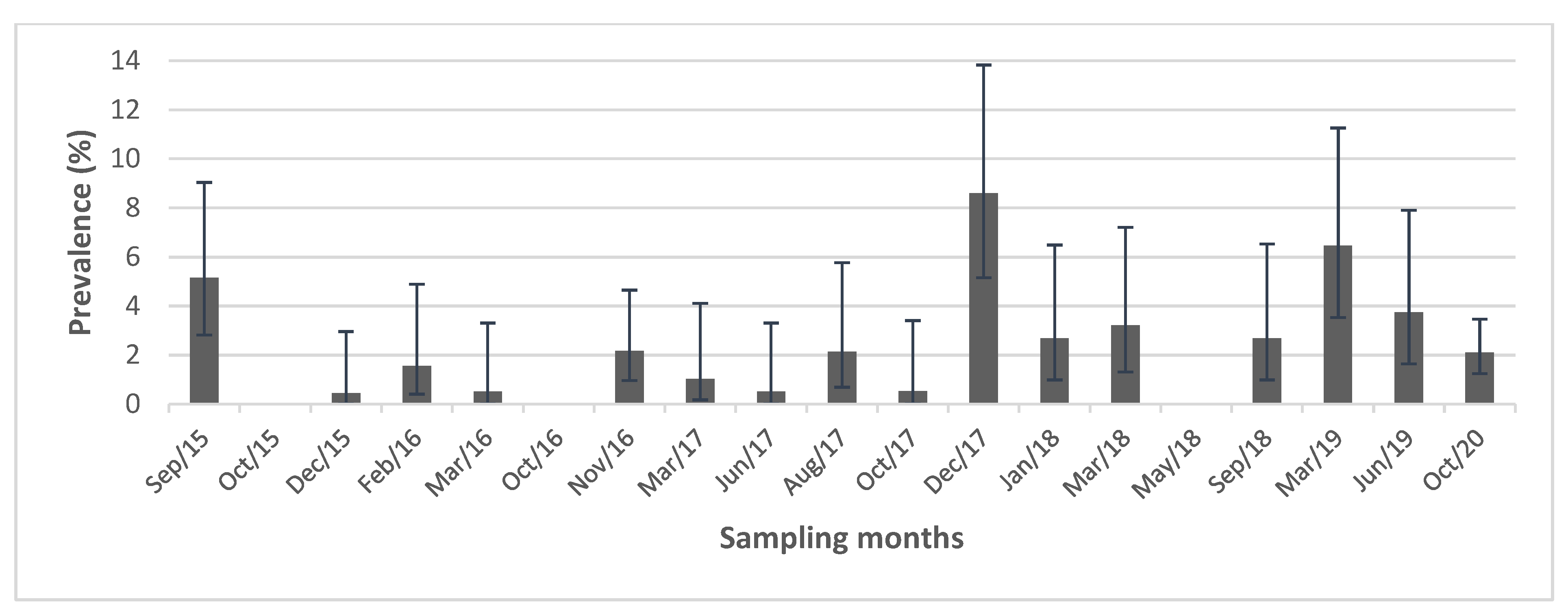

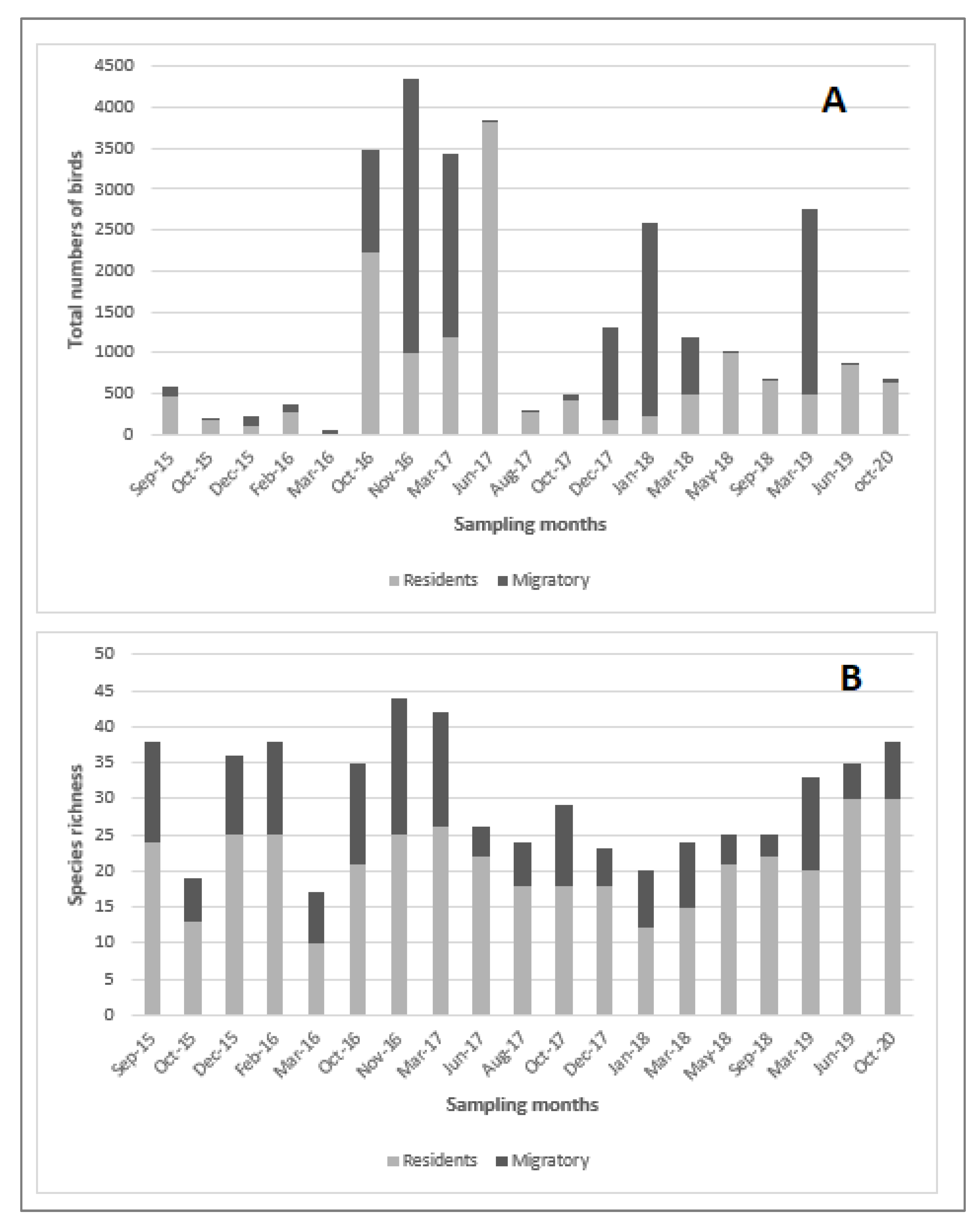

3.1. Influenza Prevalence and species richness

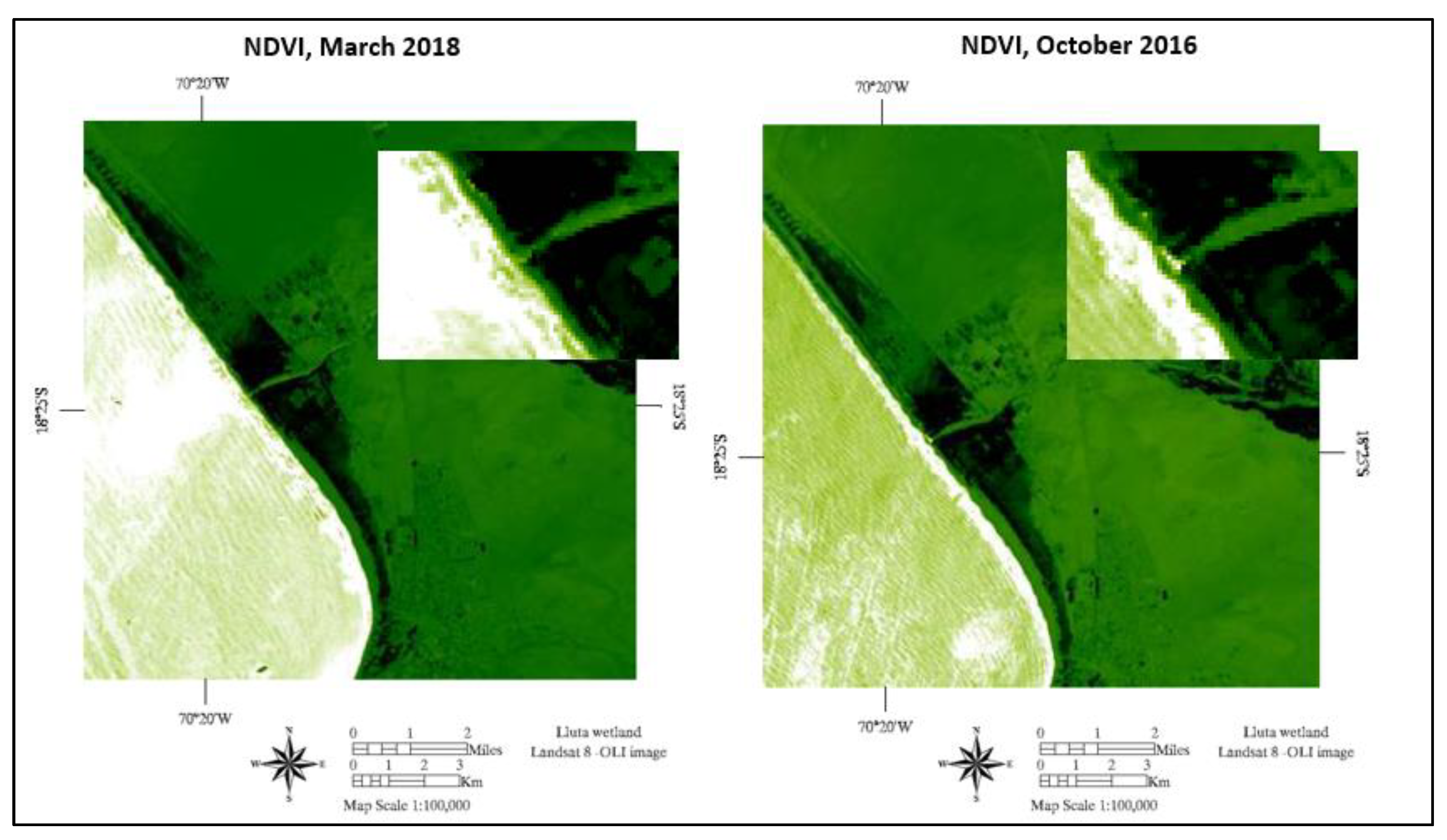

3.2. Environmental Variables

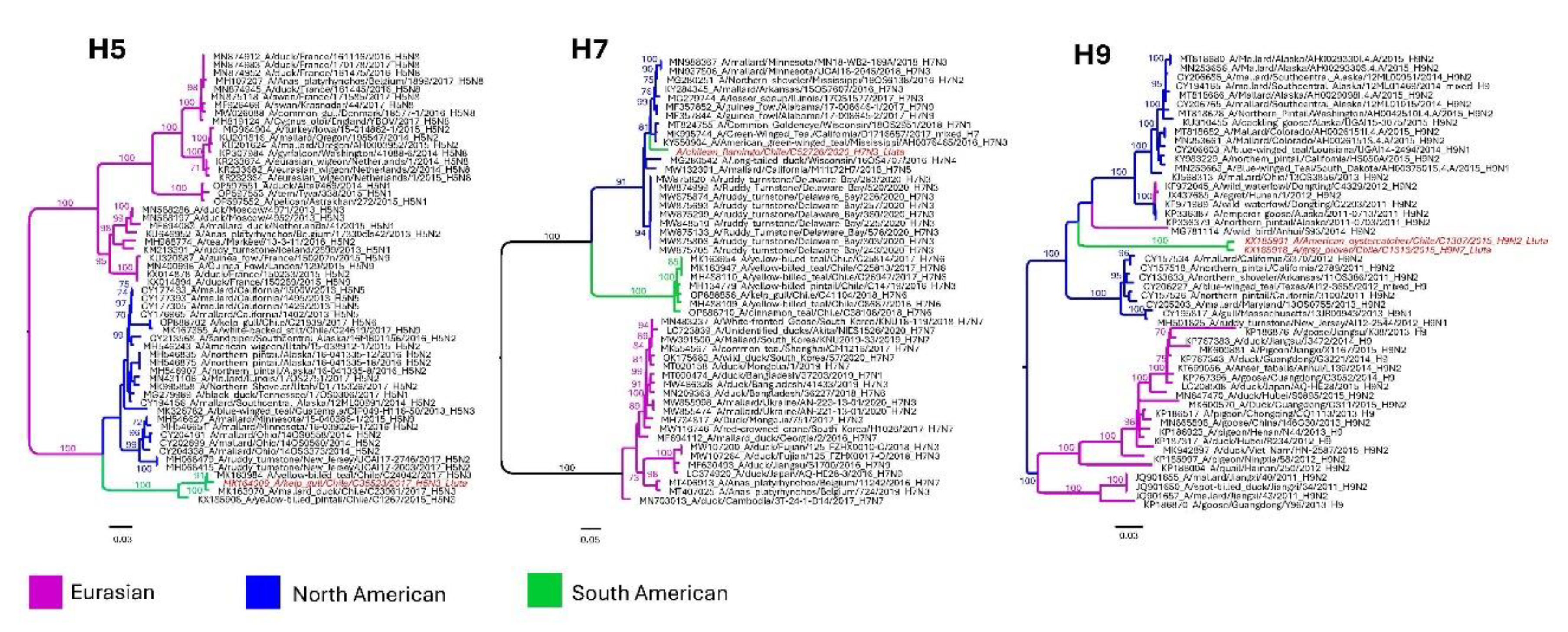

3.3. Subtype diversity and sequence analysis

4. Discussion

5. Conclusion

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgment

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Olsen, B., et al., Global patterns of influenza A virus in wild birds. science, 2006. 312(5772): p. 384-388.

- Webster, R. and D. Hulse, Microbial adaptation and change: avian influenza. Revue Scientifique et Technique-Office International des Epizooties, 2004. 23(2): p. 453-466.

- Webster, R.G., et al., Evolution and ecology of influenza A viruses. Microbiological reviews, 1992. 56(1): p. 152-179.

- Lee, D.-H., et al., Intercontinental spread of Asian-origin H5N8 to North America through Beringia by migratory birds. Journal of virology, 2015. 89(12): p. 6521-6524.

- Hesterberg, U., et al., Avian influenza surveillance in wild birds in the European Union in 2006. Influenza and Other Respiratory Viruses, 2009. 3(1): p. 1-14.

- Hoye, B.J., et al., Surveillance of wild birds for avian influenza virus. Emerging infectious diseases, 2010. 16(12): p. 1827.

- Munster, V. and R. Fouchier, Avian influenza virus: of virus and bird ecology. Vaccine, 2009. 27(45): p. 6340-6344.

- Jiménez-Bluhm, P., et al., Wild birds in Chile Harbor diverse avian influenza A viruses. Emerging microbes & infections, 2018. 7(1): p. 1-4.

- Nelson, M.I., et al., The genetic diversity of influenza A viruses in wild birds in Peru. PloS one, 2016. 11(1): p. e0146059.

- Rimondi, A., et al., Evidence of a fixed internal gene constellation in influenza A viruses isolated from wild birds in Argentina (2006–2016). Emerging microbes & infections, 2018. 7(1): p. 1-13.

- Ruiz, S., et al., Temporal dynamics and the influence of environmental variables on the prevalence of avian influenza virus in main wetlands in central Chile. Transboundary and emerging diseases, 2021. 68(3): p. 1601-1614.

- Xu, K., et al., Isolation and characterization of an H9N2 influenza virus isolated in Argentina. Virus research, 2012. 168(1-2): p. 41-47.

- García-Walther, J., et al., Atlas de las aves playeras de Chile: Sitios importantes para su conservación. Santiago: Universidad Santo Tomás, 2017.

- Bravo-Vasquez, N., et al., Presence of influenza viruses in backyard poultry and swine in El Yali wetland, Chile. Preventive veterinary medicine, 2016. 134: p. 211-215.

- Jimenez-Bluhm, P., et al., Low pathogenic avian influenza (H7N6) virus causing an outbreak in commercial Turkey farms in Chile. Emerging microbes & infections, 2019. 8(1): p. 479-485.

- Jimenez-Bluhm, P., et al., Circulation of influenza in backyard productive systems in central Chile and evidence of spillover from wild birds. Preventive veterinary medicine, 2018. 153: p. 1-6.

- Muñoz-Pedreros, A. and C. Merino, Diversity of aquatic bird species in a wetland complex in southern Chile. Journal of Natural History, 2014. 48(23-24): p. 1453-1465.

- Sielfeld, W., et al., Coastal Wetlands of Northern Chile, in The Ecology and Natural History of Chilean Saltmarshes. 2017, Springer. p. 105-167.

- Navarro, N., et al., The Arid Coastal Wetlands of Northern Chile: Towards an Integrated Management of Highly Threatened Systems. Journal of Marine Science and Engineering, 2021. 9(9): p. 948.

- Peredo, R., La Desembocadura del Río Lluta: un humedal para las aves, en el desierto costero de Chile. 2007.

- Gaidet, N., et al., Understanding the ecological drivers of avian influenza virus infection in wildfowl: a continental-scale study across Africa. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 2012. 279(1731): p. 1131-1141.

- Cumming, G.S., et al., A social–ecological approach to landscape epidemiology: geographic variation and avian influenza. Landscape Ecology, 2015. 30(6): p. 963-985.

- Ferenczi, M., et al., Avian influenza infection dynamics under variable climatic conditions, viral prevalence is rainfall driven in waterfowl from temperate, south-east Australia. Veterinary research, 2016. 47(1): p. 1-12.

- Pérez-Ramírez, E., et al., Ecological factors driving avian influenza virus dynamics in Spanish wetland ecosystems. PLoS One, 2012. 7(11): p. e46418.

- Si, Y., et al., Environmental factors influencing the spread of the highly pathogenic avian influenza H5N1 virus in wild birds in Europe. Ecology and Society, 2010. 15(3).

- Torrontegi, O., et al., Long-term avian influenza virus epidemiology in a small Spanish wetland ecosystem is driven by the breeding Anseriformes community. Veterinary research, 2019. 50(1): p. 1-12.

- Dohoo, I.R., W. Martin, and H.E. Stryhn, Veterinary epidemiologic research. 2003, Charlottetown, P.E.I.: University of Prince Edward Island.

- Organization, W.H., CDC protocol of realtime RTPCR for swine influenza A (H1N1), in CDC protocol of realtime RTPCR for swine influenza A (H1N1). 2009, World Health Organization (WHO).

- Shu, B., et al., Design and performance of the CDC real-time reverse transcriptase PCR swine flu panel for detection of 2009 A (H1N1) pandemic influenza virus. Journal of clinical microbiology, 2011. 49(7): p. 2614-2619.

- Moresco, K.A., D.E. Stallknecht, and D.E. Swayne, Evaluation and attempted optimization of avian embryos and cell culture methods for efficient isolation and propagation of low pathogenicity avian influenza viruses. Avian diseases, 2010. 54(s1): p. 622-626.

- Cheung, P.P., et al., Identifying the species-origin of faecal droppings used for avian influenza virus surveillance in wild-birds. Journal of clinical virology, 2009. 46(1): p. 90-93.

- Kaplan, B.S., et al., Novel highly pathogenic avian A (H5N2) and A (H5N8) influenza viruses of clade 2.3. 4.4 from North America have limited capacity for replication and transmission in mammals. Msphere, 2016. 1(2): p. e00003-16.

- Prjibelski, A., et al., Using SPAdes de novo assembler. Current protocols in bioinformatics, 2020. 70(1): p. e102.

- Bao, Y., et al., The influenza virus resource at the National Center for Biotechnology Information. Journal of virology, 2008. 82(2): p. 596-601.

- Hall, T.A. BioEdit: a user-friendly biological sequence alignment editor and analysis program for Windows 95/98/NT. in Nucleic acids symposium series. 1999. [London]: Information Retrieval Ltd., c1979-c2000.

- Edgar, R.C., MUSCLE: multiple sequence alignment with high accuracy and high throughput. Nucleic acids research, 2004. 32(5): p. 1792-1797.

- Jones, P., et al., InterProScan 5: genome-scale protein function classification. Bioinformatics, 2014. 30(9): p. 1236-1240.

- Rouse Jr, J.W., et al., Monitoring the vernal advancement and retrogradation (green wave effect) of natural vegetation. 1973.

- Xu, H., Modification of normalised difference water index (NDWI) to enhance open water features in remotely sensed imagery. International journal of remote sensing, 2006. 27(14): p. 3025-3033.

- Team, R.C., R: A language and environment for statistical computing; 2018. 2018.

- EMPRES-i, F. Diseases. 2022; Available from: https://empres-i.apps.fao.org/diseases.

- WAHIS. Sistema Mundial de Información Zoosanitaria. 2022; Available from: https://wahis.woah.org/#/home.

- Jones, Y.L. and D.E. Swayne, Comparative pathobiology of low and high pathogenicity H7N3 Chilean avian influenza viruses in chickens. Avian Diseases, 2004. 48(1): p. 119-128.

- Youk, S., et al., Evolution of the North American Lineage H7 Avian Influenza Viruses in Association with H7 Virus’s Introduction to Poultry. Journal of Virology, 2022. 96(14): p. e00278-22.

- Dietze, K., et al., From low to high pathogenicity—Characterization of H7N7 avian influenza viruses in two epidemiologically linked outbreaks. Transboundary and Emerging Diseases, 2018. 65(6): p. 1576-1587.

- Caron, A., et al., Persistence of low pathogenic avian influenza virus in waterfowl in a Southern African ecosystem. EcoHealth, 2011. 8(1): p. 109-115.

- Van Dijk, J.G., et al., Juveniles and migrants as drivers for seasonal epizootics of avian influenza virus. Journal of Animal Ecology, 2014. 83(1): p. 266-275.

- Di Pillo, F., et al., Novel Low Pathogenic Avian Influenza H6N1 in Backyard Chicken in Easter Island (Rapa Nui), Chilean Polynesia. Viruses, 2022. 14(4): p. 718.

- Mathieu, C., et al., Avian influenza in wild birds from Chile, 2007–2009. Virus research, 2015. 199: p. 42-45.

- Ghersi, B.M., et al., Avian influenza in wild birds, central coast of Peru. Emerging infectious diseases, 2009. 15(6): p. 935.

- Farnsworth, M.L., et al., Environmental and demographic determinants of avian influenza viruses in waterfowl across the contiguous United States. PLoS One, 2012. 7(3): p. e32729.

- Fuller, T., et al., Seasonality dynamics of avian influenza occurrences in Central and West Africa. bioRxiv, 2014: p. 007740.

- Ashok, A., H.P. Rani, and K. Jayakumar, Monitoring of dynamic wetland changes using NDVI and NDWI based landsat imagery. Remote Sensing Applications: Society and Environment, 2021. 23: p. 100547.

- Wu, X., et al., Normalized difference vegetation index dynamic and spatiotemporal distribution of migratory birds in the Poyang Lake wetland, China. Ecological indicators, 2014. 47: p. 219-230.

- Gaidet, N., Ecology of avian influenza virus in wild birds in tropical Africa. Avian diseases, 2016. 60(1s): p. 296-301.

- Mathieu, C., et al., Pandemic (H1N1) 2009 in breeding turkeys, Valparaiso, Chile. Emerging infectious diseases, 2010. 16(4): p. 709.

- Pereda, A.J., et al., Avian influenza virus isolated in wild waterfowl in Argentina: evidence of a potentially unique phylogenetic lineage in South America. Virology, 2008. 378(2): p. 363-370.

- Sullivan, B.L., et al., eBird: A citizen-based bird observation network in the biological sciences. Biological conservation, 2009. 142(10): p. 2282-2292.

| Variables | Definition | |

|---|---|---|

|

Wild bird community |

Total abundance | Total number of birds present at the time of sampling |

| Species richness | Number of species present at the time of sampling | |

| Abundance of migrants | Number of migratory birds present at the time of sampling | |

|

Landscape |

Vegetation coverage |

Mean NDVI for the month of sampling, one month before, two months before and three months before sampling. |

|

Water body size (km2) |

Water body size for the month of sampling, one month before, two months before and three months before sampling. | |

|

Meteorological data |

Maximum monthly temperature (°C) |

Monthly mean of maximum daily temperature for the month of sampling, one month before, two months before and three months before sampling. |

| Minimum monthly temperature (°C) | Monthly mean of minimum daily temperature for the month of sampling, one month before, two months before and three months before sampling. | |

| Total monthly rainfall (mm) | Total rainfall at the month of sampling, one month before, two months before and three months before sampling. | |

| Humidity (%) | Relative air humidity at the month of sampling, one month before, two months before and three months before sampling. | |

| Variables | Categories | Estimate | p-value | OR | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Intercept) | -5.5872 | <0.001 | 0.003 | (0.001-0.01) | |

| NDVI | Low (< 0.27) | Reference | |||

| High (≥ 0.27) | 1.2949 | 0.00230 | 3.65 | (1.58-8.39) | |

| Abundance of Migrants | Low (< 113) | Reference | |||

| High (≥ 113) | 1.2727 | 0.00733 | 3.57 | (1.41- 9.05) |

| Strain name | Year | Isolate Subtype | Hot species | Order | Accession Number |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A/American oystercatcher/Chile/C1307/2015 (H9N2) | 2015 | H9N2 | Haematopus palliatus | Charadriiformes | KX185901 |

| A/Grey plover/Chile/C1313/2015 (H9N7) | 2015 | H9N7 | Pluvialis squatarola | Charadriiformes | KX185918 |

| A/American oystercatcher/Chile/C17359/2016 (H3N8) | 2016 | H3N8 | Haematopus palliatus | Charadriiformes | MH499035 |

| A/American oystercatcher/Chile/C17400/2016 (H3N8) | 2016 | H3N8 | Haematopus palliatus | Charadriiformes | MH498968 |

| A/Franklin’s gull/Chile/C17421/2016 (H13N9) | 2016 | H13N9 | Larus pipixcan | Charadriiformes | MH498978 |

| A/Franklin’s gull/Chile/C17422/2016 (H13N9) | 2016 | H13N9 | Larus pipixcan | Charadriiformes | MH499057 |

| A/Kelp gull/Chile/C27733/2017 (H13N8) | 2017 | H13N8 | Larus dominicanus | Charadriiformes | MH499142 |

| A/Kelp gull/Chile/C35523/2017 (H5N3) | 2017 | H5N3 | Larus dominicanus | Charadriiformes | MK164009 |

| A/blackish oystercatcher/Chile/C40194/2018 (H13N2) | 2018 | H13N2 | Haematopus ater | Charadriiformes | OP888556 |

| A/Chilean flamingo/Chile/C52796/2020(H7N9) | 2020 | H7N3 | Phoenicopterus chilensis | Phoenicopteriformes | OQ820949 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).