1. Introduction

How and why has land become an object of attention from public authorities? This somewhat trivial question helps to understand the problem of “ungovernability” of African cities in the 21

st century. Any social fact can potentially become a "social problem" if it emanates from the volunteer action of various operators as a problematic situation that must be debated and receive responses in terms of public action [

1] (p. 80). In literature, land problem is the subject of several scientific writings and debates. This is because it is the support for any economic development action, urban policies (planning, urban development, housing, roads, etc.) and fiscal policies. The answers to the problems are many and varied. They depend on time but also on changes in political doctrines. Indeed, by reading one realizes that for a long time [

2], it was believed that land problem was of a legal, technical, economic nature and that a good dose of ingenuity would be enough to solve it. However, with the complexity of land functions and uses, we have come up in the course of our research with discovering that land was the most significant political problem that exists there in our contemporary societies confronted with a constant population increase [

3] (p. 159).

Public, economic, urban, tax, social and housing policies for populations are determined by the availability of, and access to, land resources. Consequently, land is a fact of society and therefore a political fact in the broad sense of the term. Only a good land policy will allow access to this resource not only for public state institutions, communities and firms, but also for the middle classes and the most vulnerable.

Benin, in its societal trajectory, shows sustained dynamism in terms of land policy. She has experience in fairly decentralized land management through the municipal land affairs departments. Similarly, local management instruments (Urban Land Register, Rural Land Plan,) put in place from 1989 serve as land data base. These are information systems qualified as simplified and computerized land registries set up in certain municipalities of the country. In most cases, they have enabled an increase in tax revenue, an inventory of presumed municipal ownership, proof of private property rights and support for the emergence of the land market [

4,

5,

6]. However, several problems have arisen from this communal management. Among these are, a questioning of formerly recognized and legitimized transactions, conflicts between municipalities and communities on subdivisions/resettlements, neighborhood conflicts on the topographic limits of plots, land grabbing that threatens families with explosion, the loss of agricultural land, the sale of private State domains, land securitizations on public domains, etc. In order to provide solutions to these problems which have become structural challenges for the Beninese State, an alliance is forged between political actors and technical actors for the establishment and conduct of the development project of a land registry overseen by a centralized national institution, namely the National Agency Estate and Land (NAEL) [

7].

To understand the land question, the reforms initiated for its management lead to perceive the different turns taken by the decisions and conceptions relating to the "land thing" over time. In terms of land, the political decision becomes the raison d’être of technology. The development of a land information system such as the cadastral system can be conceived and prosper if only it enjoys political support. However, even if the political will is acquired and good governance is accepted as a principle [

8,

9], the question of the means of real action arises insofar as from the period of the Structural Adjustment Plans (SAP)

1 Today, Benin’s development policy involves foreign aid. Yet, it must be recognized that receiving aid is not enough to carry out actions that can bring about development; it takes political will to achieve any result. By following the reforms that have been carried out in the land sector in the last decade in the country, we can say that political will is a crucial issue in the Beninese land system. The objective of this article is to describe the public action that surrounds the establishment of the cadastral system in Benin, the legal and technical innovations that furnish its development and the public gaze of the population on this policy.

2. Theoretical framework and methodological approach to the research

2.1. Theoretical frame

The explanation of the notion of public action which would be “the fruit of a desire to put in place the socio-political conditions for dealing with problems” [

10,

11] (p.3, p. 58), in case these problems affect the public sphere, leads us to specify this research in "the theory of change in public action" by [

12]. According to such an approach, there is a change in public policy when we are faced with the following three changes: changes in (i) objectives, (ii) instruments and (iii) institutional frameworks [

12] (p. 157). Contextually, we can notice, beforehand, that the objectives pursued by land management in Benin boil down to: reconciling land tenure systems (customary and modern) with a particular emphasis on the land registration system, promoting land rights, registration at municipal level, increasing tax revenue, developing communal territories through land knowledge. It is with the aim of achieving these objectives that such instruments: Urban Land Register (ULR) and Rural Land Plan (RLP), License to live, have been put in place. All these instruments are managed by various institutions (town halls, ministries of finance and urban planning, technical partners) which do not necessarily have a mechanical linkage connecting them. Faced with results below expectations and alarmist reports on the state of land in Benin changes were introduced and did affect the objectives, instruments and institutions [

13,

14]. The current objectives targeted by the decision-makers are to make of land a lever for economic development, to pacify land relations and to settle the countless disputes that pollute community life and weaken the country's attractiveness in terms of business [

15]. It is in this wake that at the level of the instruments, the cursor is put on the development of a national cadastral system hosted by a new institution with dismemberments in the municipalities. The National Agency for Estate and Land has therefore become the leading land institution in the country, far ahead of town halls and other decentralized services.

Building on these changes, this paper aims at seeing, through the theory of change in public action (by P. Muller cited above), how the cadastral instrument, which will make possible its realization and setting in motion the public action, is developed and how technical aspects are initiated as well.

2.2. Methodological approach to the research

The data for this work are produced in Benin on the Cotonou, Abomey-Calavi, Bohicon roaming. These 3 cities are chosen for the simple reason that they were the first places to host the experimental phases of the cadastral project in the country. They are collected through a methodology based on the qualitative approach to the land issue as is described and the MARP methodology (Active Method of Participatory Research) following the principles of ignorance, participation, triangulation, flexibility and restitution of [

16,

17]. Beforehand, we went through the documents of the scientific literature and the gray literature on public action, land management, the development of land information systems in order to understand the mechanisms and decision-making processes related to the development of a cadastral system. Next, we went on the field to observe in a participatory manner and sometimes as a land expert the procedures for data collection, publication and computer processing. There were also individual interviews and focus groups with authorities and populations involved in the development process of Benin's cadastral system. These semi-structured interviews took place with 8 agents from the Land Registry and Land Information Operations Department (DCOIF), 6 representatives of the Village Land Management Sections (SVGF), 6 traditional chiefs, 10 geo-land experts, 2 officers from the town halls of Abomey-Calavi and Bohicon, 2 officers from the National Geographic Institute. As for the focus groups, they are held with 9 groups in 6 villages/districts.

To account for the answers, transcripts are provided; but for reasons of confidentiality, the names or the function of the interviewees are not mentioned in the text. We rather use the terms “agent”, “responsible”, “beneficiary”, “participant” according to the contexts of the meetings and the responsibility occupied. The information collected is mostly heterogeneous and has not been subject to systematic saturation given the generally reasoned choice of the respondents. The photographic images were collected to support the observations made in the technical process.

3. Results

Through the theoretical framework and the methodology adopted, the results put forward here explain the changes that have taken place in land management policy in Benin, particularly in terms of political will.

This section may be divided into subheadings. It should provide a concise and precise description of the experimental results, their interpretation, as well as the experimental conclusions that can be drawn.

3.1. Political will driven by legal reforms

To restructure land management, Law N

o 2013-01 on Land and Domain Code (LDC) in the Republic of Benin was promulgated on August 14, 2013 by the Boni Yayi regime

2 [

18,

19]. From that date until now, reforms have followed one another and no less than 30 legal texts (laws, decrees, orders) have been relatively adopted in the land domain, including 18 for the period 2016-2022

3 alone, which is equivalent to almost 3 texts per year. This manifest legal dynamic is the result of a political will to make of land a lever of the national economy by focusing on the real operationalization of its central management institution: the National Agency for Estate and Land

(Agence Nationale du Domaine et du Foncier-ANDF) [

20].

NAEL is an offshoot of LDC (Land and Domain Code). Article 416 of the said code announces: “a public establishment of a specific technical and scientific nature is created, endowed with legal personality and financial autonomy called: National Agency for Estate and Land (NAEL). It is placed under the supervision of the ministry in charge of finance by law n° 2017-15 of August 10, 2017 which modifies and supplements law n° 2013-01 of August 14, 2013 on the Land and Domain Code in the Republic of Benin [

21]. Already in 2015, the decree n° 2015-405 of July 20, 2015 was adopted to rule on its operation [

22]. Several prerogatives are devolved to it, in particular the confirmation of property rights. It is to contribute to effectively fulfilling its prerogatives that the national cadastral tool is designed. The development of this tool announced in article 452 of the LDC and defined as "computerized unitary system of technical, tax and legal archives of all the lands of the national territory" (Art. 454, LDC) is concretized by the decree n° 2016-726 of November 25, 2016 on the creation, organization, powers and operation of the technical committee for the supervision of the national land registry [

23]. This decree was issued on the “proposal of the President of the Republic, Head of State, Head of Government”, the most central player in government action. Its technical supervision committee is placed by its article 5 under the direct authority of this first official responsible for government action. This shows the political scope of this project. The development of the cadastral system represents an issue at the “highest” of the political summit, as is shown by the decisions that contribute to its implementation and monitoring. For its materialization, the system is sequenced into several national projects.

3.2. A Land Registry developed into sequenced projects

At the operational level, the development of the cadastral system resulted in the launch of the “Modernity and Land Security” projects from 2017 to 2019 and the “Land Administration Modernization Project (LAMP)” thus far 2019.

The Land Modernity and Security project is a project to digitize available land data. It is above all a recovery of files and their centralization. Indeed, through this project, a systematic collection of subdivision and development plans, ortho-photo directories, old land titles, etc. were carried out with various institutions. These are the National Geographic Institute (NGI), the General Directorate of Urban Development (GDUD), municipalities, surveying firms, departments of the Ministry of Lands and Urban Planning. All the data received were mapped and enabled classifications in relation to the territories that have full data, those that have some data and those that do not have any. In terms of results in relation to this project, it appears that nearly 58,000 Land Titles – old and new – have been integrated into the e-Terre database created for the occasion, 95% of the localities have been positioned or repositioned in the cadastral base, 1,961,046 plots have been integrated into the cadastral database. 7% of the plot area, i.e., 8,153 km² out of 79,299 km² of surface area, excluding forests and hydrographic cover, is covered. It also contributed to the launch of the website

www.cadastre.bj which provides primary information on plots. During the process, all the institutions involved cooperated ardently in the principle of making land data available. However, some fears have been expressed by some key players. For example, in the case of municipalities, an agent from the NAEL told us that they only receive appointments from certain town halls, or that they send them to the surveyors who carried out the subdivision whereas the surveyors also claim to have submitted all the files to the town hall after work, but the umbrella organization is well involved in the process and that they had to train with elected officials and explain the merits of this operation before it started”. In other institutions, the data received do not correspond to any reality on the ground and require all work to be resumed. An official said that the data received from the IGN are old-dated, the materials worn out, which means that the projected geodetic data do not align with the plot readings in the field. It is these difficulties that led the NAEL, the Beninese government and its technical and financial partners to develop the Land Administration Modernization Project (LAMP).

LAMP is a support program of the Dutch embassy and the Dutch land registry agency (Kadaster) for the establishment of the Beninese cadastral system. This project aims at strengthening land administration, verifying existing data on the ground, updating data and launching the collection and processing of new data on a larger scale. In its implementation, the NAEL has contracted with private service providers (computer scientists, surveyors, mobilization agents, Rural Land Management Section). The procedures for collecting and processing data can be classified into three phases (

Table 1)

This table showing the procedures followed in the collection of land data points out an administrative innovation which consists in surrounding oneself with private service providers in the conduct of public projects. This public-private partnership about land matters has proven to be useful and necessary when we know the bureaucratic heaviness that generally surrounds public decisions. In this sense, a manager confides to us that for him, having it done is the best thing, contracting with private service providers is a quick solution, for example in the event of an emergency of a data, even on weekends the service provider private can go to the field and send you the information whereas at the level of the public services, the civil servants will send you back on working days, with questions of order of mission and all.

All the data collected are then transmitted to the managers of the interactive land registry data platform.

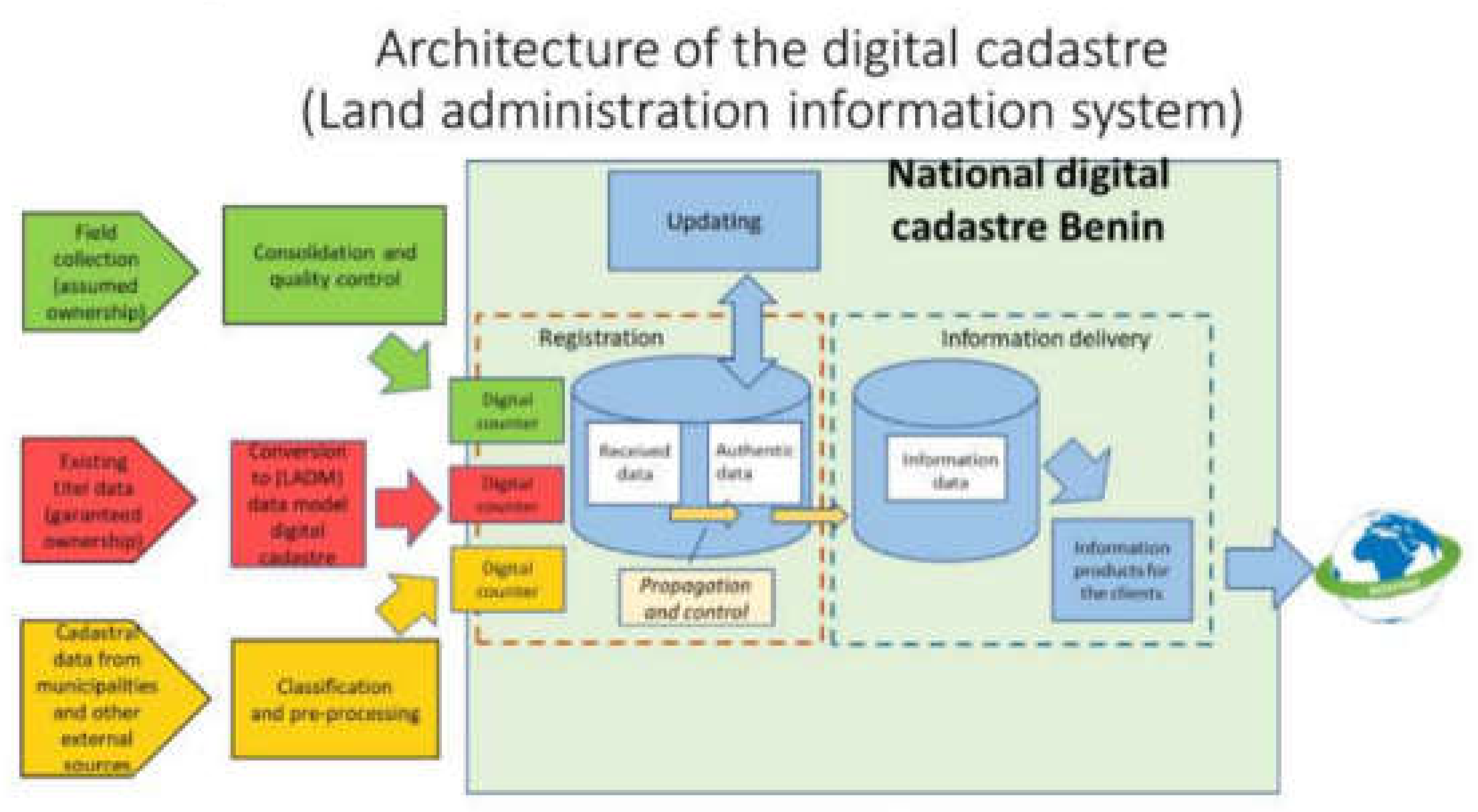

3.2.1. Interactive and dynamic platform for the production of land data

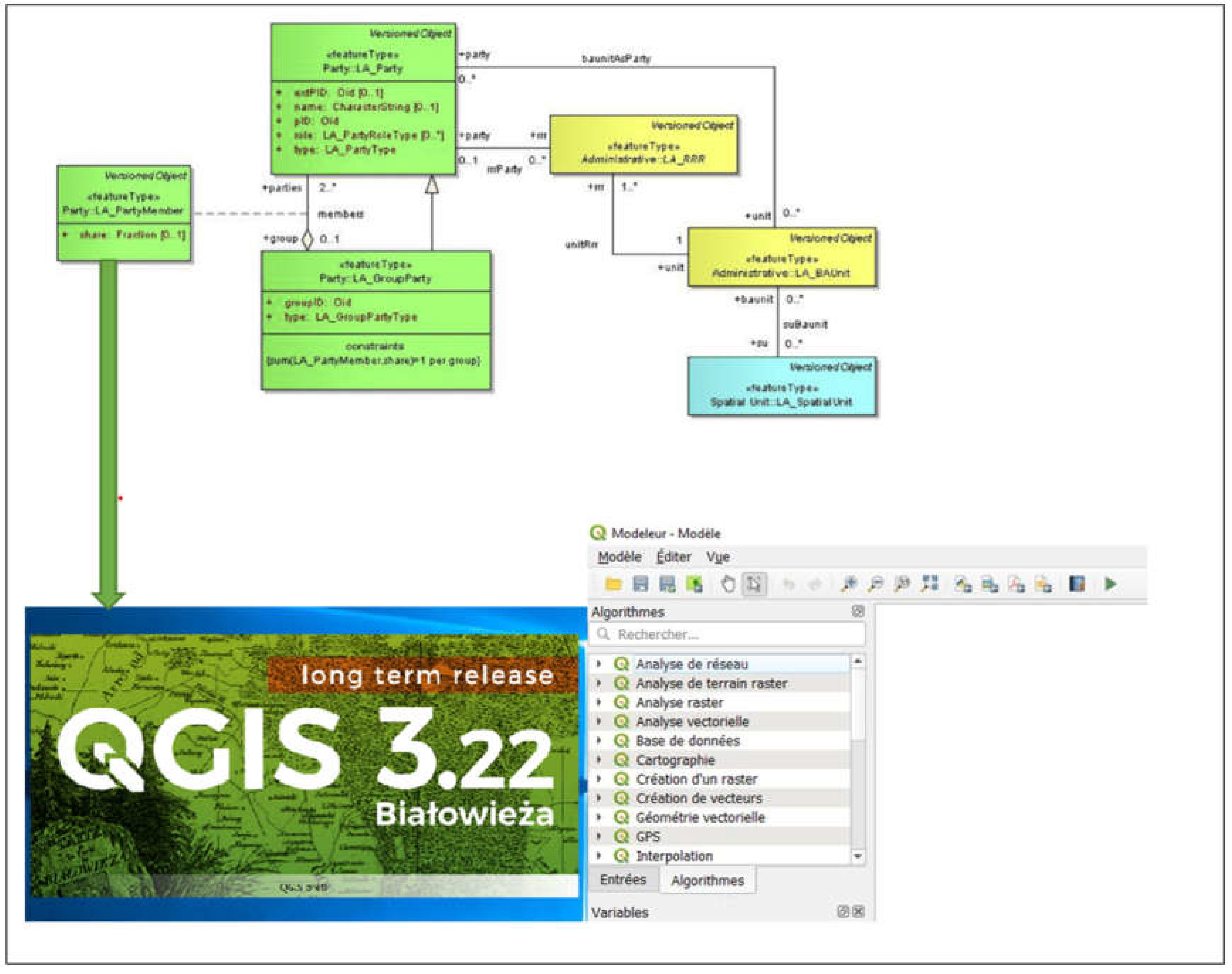

In 2012, the United Nations and the World Bank developed an interoperable and interactive generic land database. This is the ISO 19152 Geographic Information-Land Administration Domain Model (LADM) standard [

24,

25,

26,

27,

28]; it is a global generic base from which each country, like Benin, drew inspiration to design its cadastral system”. It is a standard that provides a formal language to describe the right to property through 4 packages: (i) individuals and organizations, (ii) property rights, (iii) plots and legal space of buildings and networks, (iv) topographic surveys and representations. From this model is deduced the Land Information System (SIF) supposed to provide the objects on which the system operates. It is based on the QGIS software and connected to the e-Terre platform for all data relating to confirmations of land rights and production of Land Titles (

Figure 1).

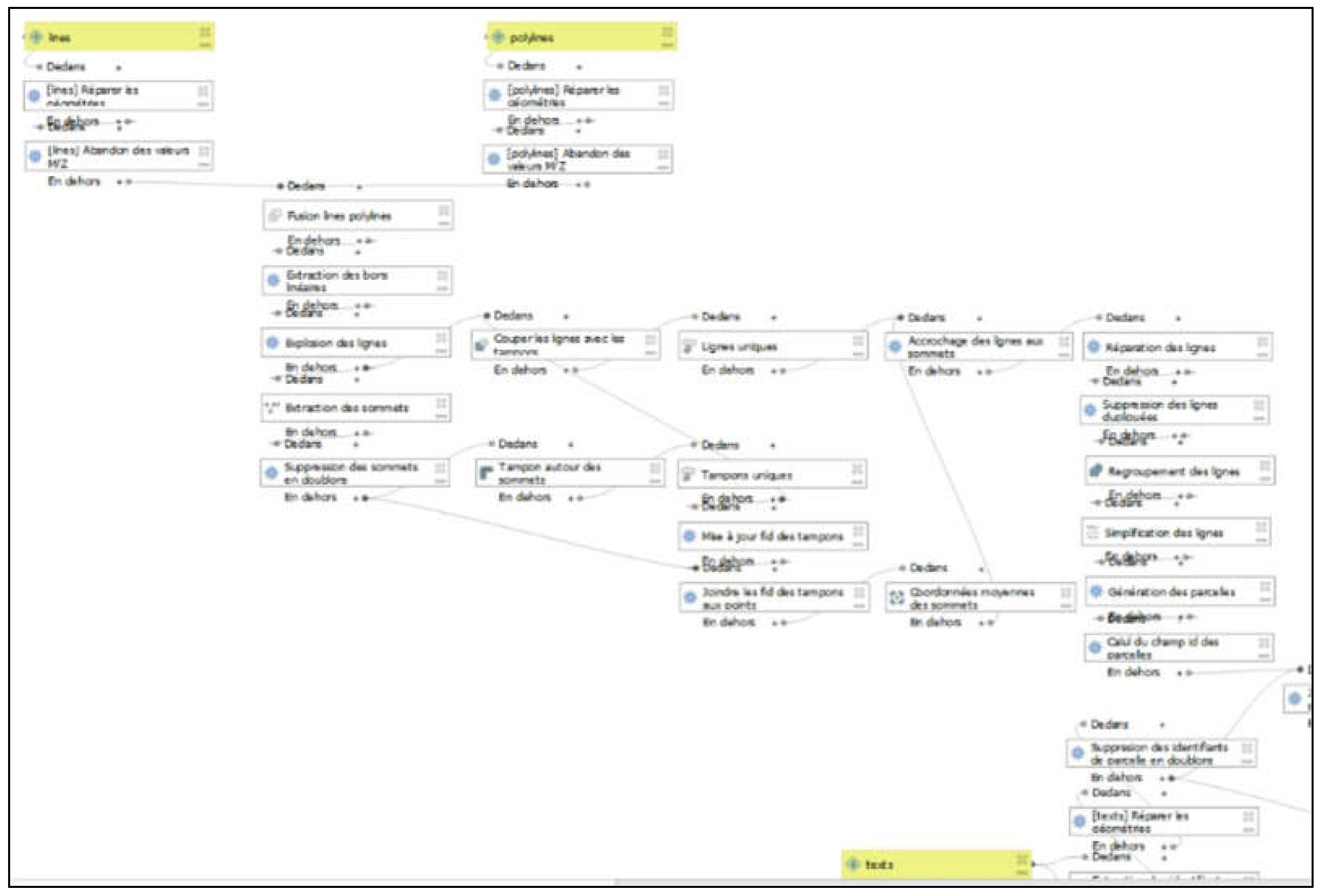

From a technical point of view, it can be seen that the QGIS software makes it possible to carry out a multitude of operations in the SIF. For a computer scientist, the QGIS software is used because it is open source, it is free software which is available and which is easy to use and gives technicians a hand in developing the operation through an interoperable modular. The base is assembled from an algorithm to group all data creation projects into a modular (

Figure 2)

As is shown in

Figure 2, the modular system makes it possible to have data on several computer hardware, permitting the instant processing and storage of data by all authorized on the central server and to ensure a fairly flexible operation of QGIS. However, the production of data is mainly oriented towards one goal: it is the acceleration of the issuance of land titles.

3.2.2. Process of creating of Land Titles: technological interaction

In the process of creating Land Titles (LTs), there is an interaction between several technical actors but also between several systems. This process leads us to understand the functioning in networks of the production of land data. Specifically, the creation of LTs passes through the land registry system in a restrictive way through two technical sets. These are boundary work and data integration work.

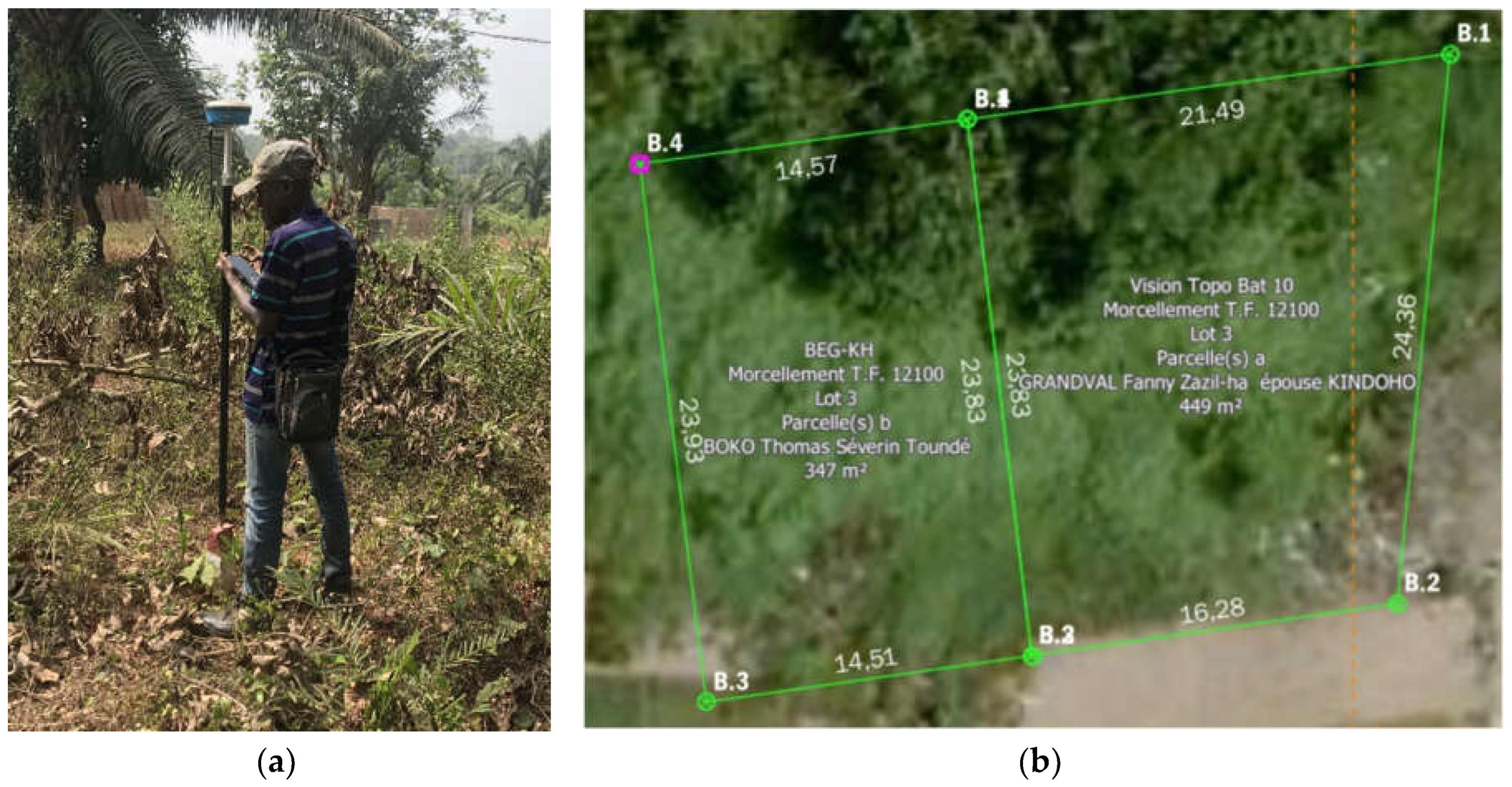

3.2.2.1. From survey to control of demarcation: preliminary and effectiveness of plot boundaries

Equipped with the dual-frequency global positioning system, the geo-topographic agents collect the terminals of the plots. This operation, legally referred to as contradictory survey, makes it possible to hold the boundaries of a plot with a physical presence on the ground and a virtual presence in the land registry base of local residents or of any person with a proven interest or knowledge of land in the area. It is the recognition of the limits of a field by concrete terminals established by the surveyors-topographers. In the GIS land registry data production system, the coordinates (x, y) collected using the GPS are inserted in order to virtually locate the real space. The NAEL in its role as controller of operations, and to avoid awarding a land title to an ill-defined space, passes the surveyor's "delivery" through the survey control operation. This control is very important in the LTs production circuit. It aims to control the position of the coordinates sent on the plot plans introduced and to ensure the conformity of the surveys produced with the real setting on the space. The data is approved in general with a tolerance not exceeding 50 cm (

Figure 3)

This plate shows us in a virtual way (image 2) the coordinates collected by the agent-topographer (image 1). The topographer agent, using his instruments, collects the information that he most often processes by the AutoCAD software and sends to the NAEL for calibration on the GIS. Despite the rigor that surrounds this operation, the anti-dating of several elements of space and of the recovered satellite image does not always favor data conformity and we sometimes end up with LTs produced completely out of step with ground reality. But the control procedure has shown a lot of efficiency in the recognition of plot boundaries.

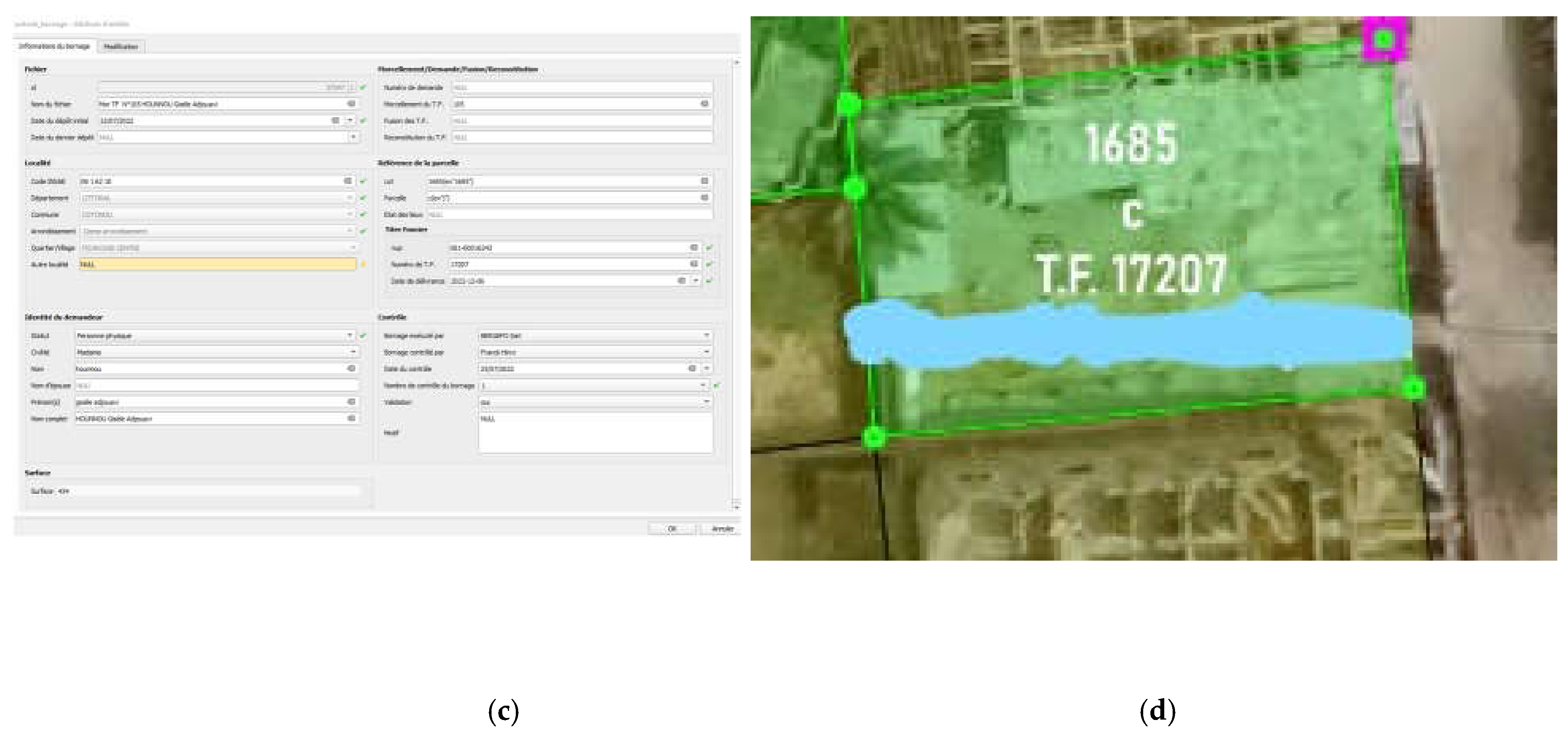

3.2.2.2. Integration of Land Titles and updating of cadastral spaces

It is a process that consists in integrating into the land registry database itself the Land Titles produced for their digital preservation and for their online visibility. This integration makes it possible to fill in all the identities, those of the plot owners and their neighbors as well as all the social information necessary for the recognition of the right of ownership.

This integration leads to the update of the property directory. If the integration is effective, we directly see a change in the status of the plot through several elements such as the change of visual, the registration number of the plot and titles issued. This update makes it possible to have the data of the Land Titles and the plots updated, for example in the event of a change of name, mutation or fragmentation. The information on the property will then be available and can help answer questions about the identity of the owner, be used for taxation, and contribute to conflict resolution (

Figure 4).

This Figure shows us the process of integrating and updating information in the land registry system. It is through this process that the general public can have access to digitized data and be able to consult certain data online. Its importance is to provide proof of ownership and digitally archived land data. However, it can be noted that access to data is very limited for the population. Any individual cannot seek information such as the name of the owner without going through the administration. It is a limit of the system even if according to a technical agent, it is to keep confidentiality at our level and it is only at the request of a state structure or an authorized person, for example a court, a surveyor that we will provide the names.

One of the aspect that emerges for the success or otherwise of the land registry process and the production of Land Titles is the adhesion of the public, of the owners to register in the land registration process.

3.3. Public support and interest in the national land registry project

To the main question "what importance do you give to the Land Registry?" Various answers have been put forward, but in general many respondents have a rather limited understanding except for the fact that the government seeks to secure the plots for free. It is at the level of people who have already experienced acts of insecurity that we find the interest of such a process. For example, we can count on this statement by a resident of Houedo-centre who explains that the problems that those who live in the Wome district experience with respect to the plot is enormous, and therefore if people’s names are registered by the State, it is good because they can sell their land more easily. Likewise, one of the participants in Alansacomey told us that in 2014, when the surveyor wanted to take stock of the situation in the area , there is a lady who brought her plate to my plot, but God knows how to do things, after 3 days I arrived and found that my plate is removed, a new plate of 8 digits is placed but mine had 6 digits, there was a number below I called and the gentleman sent me back to see the one I think should be the one who sold me the plot: I wanted to build on it but the old man bet me to ask everywhere who he is, then I saw my plate hidden in the bush but the old man and his wife swore they didn't see the plate and we started disputing. In front of the surveyors, they backdated their plot for 12 years while mine was 13 years. It was God who helped me and it was in 2017 that I joined the town planner who asked the surveyor to regularize the situation on my behalf. From 2017 to this day, they have not returned and that is why everything the government does for the security of our plot is good.

These remarks largely express the expectations of the populations regarding this project. However, concerns are raised by some, particularly with regard to the property tax that will come after the registration since, in the words of a participant, the government does nothing for no purpose and we know all that.

4. Discussion

4.1. Public action and the desire to solve a societal problem

The successive land problems in Benin have led governments to rethink land policy and to carry out actions that go through legal, institutional and technical aspects [

29]. Indeed, from 2013, the year of establishment of the LDC to date, reforms follow one another in the Beninese land landscape leading to a process of change. The reforms which are merely an adaptability of the institutions to the social problems are not by themselves reforming. Only political will in the sense understood is likely to bring about a change in public action [

30] (p. 21). For [

30], public action asserts itself only when it is driven by a strong, enlightened and legitimate political will [

30]. This political will, is not the guarantee that a development project will succeed but it activates the decision-making process and the implementation process, specific to public action [

31,

32]. It is this activation that the development process of the land registry project in Benin seems to show. It is declined in our research by the texts taken relating to the cadaster as well as the responsibilities of the various structures, in particular the NAEL in land management. As a new institutional framework, the NAEL seems to be an institution for circumventing the prerogatives of the decentralized structures involved in land domain. We believe that it calls into question the decentralized management policy advocated by the administrative decentralization of land issue.

4.2. Importance of land registry in land information policy

The importance of a land information system in developing countries was first raised in the 1980s [

33,

34]. For [

35] (p. 6) “a land registry system is important for the sustainable development of land management”. Even authors says “in developing countries, the introduction or improvement of land administration systems is a key component of land policy for countries” [

36]. The land registry is a continuation of the modernity of land administration based on the Torrens system. This system introduced in African countries through colonization and preserved after decolonization is focused on the distribution of titles to elites [

36,

37]. The difference that the land registry establishes with the Torrens system is that it goes beyond the registration of land rights, assesses the land market and distributes land information. In the case of Benin, the national political authorities have a desire to recover land management that was neglected in the past. The development process of the cadastral system is based on the LADM (Land Administration Domain Model) prototype but it needs to be legally constituted so that the design data of packages, classes, and system attributes can truly gather [

38]. Is it currently the case? Indeed, no particular legal text enshrines the model except the land registry procedures manual which describes the parts. However, it is progress that formalization follows a process of computerization today in Benin. The availability of computer equipment, the implementation of QGIS software, the e-Terre software package, the dematerialization of procedures and the online land registry are some of the actions noted. This work joins the thought of the author who thinks that the cadastral system is gradually abandoning paper systems in the face of the “technological thrust: internet, (geo)-bases data, modeling standards, open systems, GIS” [

39] (p. 630).

This formalization is fueled by the reflections of [

40]. For him, the main problem of developing countries is not the lack of entrepreneurial spirit but rather the lack of a formal property system integrated into a single information system so that dormant real estate assets can generate more production. Such reflection legitimizes the fight for formalization by the authors [

41] (p. 47). The desire to distribute formal rights instead of the recognition of local land holding rights is at the origin of the cadastral project. It is clearly geared towards the production of land titles in quantity [

42]. The authors even made an assessment according to which: “Of the estimated seven million cadastral plots of land, only 50,000 plots have a land Title and are registered in the NAEL central database”; say approximately 0.7% of the plots [

7] (p. 2). Also, according to the mechanisms of land administration, only the transactions on the titles are brought to the attention of the agency. This means that the majority of transactions escapes the systems and is now the object of covetousness on the part of political and economic authorities.

4.3. Question of adherence to the cadastral system: Between economic strategy and social duplicity

The objective of securing maneuvers through the development of the national cadastral system is multifaceted, but it is above all economic. We could even say that it is an investment from which the State expects a return in the medium and long term. However, the objectives of public policies unacknowledged publicly can be resented by the population. This social perception can condition the success or failure of the project. Authors think in this sense that land reforms often do not achieve their objectives in Africa [

43]. They face several pitfalls including public support. [

44] reports:

the transformation of a society and the development of its economy depend less on the elaboration of technically correct plans and projects than on the capacity of social groups and the popular masses to stimulate and animate a development which they themselves have defined [

44] (p. 513).

From there, we notice that the failure imputed to the antecedent instruments of management in particular the Urban Land Register (RFU) or the Rural Land Plan (PFR) is partly found in the low adhesion of the popular masses in its policies taking into account their low contribution to the everyday life of the population. This observation is consistent with that established in a report on the functioning of the RFUs. Indeed, the experts raised on this occasion that “the lack of communication around the operation of the RFU maintains a poor understanding of the benefits of local tax collection by the populations” [

5] (p. 42). It would then be wise for governments to follow the example of the failures of other tools in the development of the national cadastral system.

5. Conclusions

From the foregoing, we will ultimately recall that the basis for a politico-technical change in land management is undeniably linked to the political will of the first actors. Public action in land matters in this case is the consequence of the institutional and legal reforms undertaken and the will to follow up what is promoted. That being said, the development of the national land registry in Benin benefits, according to the activities carried out in its constitution, from sustained technical dynamism. By basing its development on the LADM standard and the SIF QGIS, the cadastral system achieved its objective of dematerializing, producing the TFs and updating the information relating to the TF available on the national territory, but there is still a lot to do in terms of sensitization and explanation of cadastral procedures to the population. The population’s understanding of the technical aspects will be of a great use to membership and the future of the system.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: M.K.N. K.M.N. and T.S..; methodology, G.N validation, M.K.N.., K.M.N.,T.S. and G.N..; formal analysis, K.MN. investigation, M.K.N..; resources, C.C.A.; data curation, M.K.N..; writing—original draft preparation, M.K.N. writing—review and editing: K.M.N., T.S., G.N. and C.C.A. visualization, M.K.N..; supervision, G.N..; project administration, M.K.N..; funding acquisition, M.K.N., T.S., C.C.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.”.

Funding

“This research received no external funding”.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

We thank CERVIDA-DOUNEDON and NAEL offices for administrative and technical support in data collection in Benin. We also thank A4 Langues-Traductions, Guézohouèzon Moustafa, CHOKPON Estelle and DEGLE Koudjo Mario for reading and proofreading. As well as the evaluators who have bee, accepted to enrich this paper with their reading and contribution.

Conflicts of Interest

Declare conflicts of interest or state “The authors declare no conflict of interest.”.

Appendix A

This appendix gives an overview of the sections included in the questionnaire

The main questions of the interview guide

Section# 1: Questions to various institutions

Tell us about the genesis of Benin's national Registry project

Explain to us how the cadastral services work (the tasks that are carried out by the agents).

Tell us about your procedures for obtaining land data in the city? (various sources given).

Tell us about the tools available to the cadastral service in the exercise of its activities?

Tell us about the transformations carried out at the legal level and at the technical level for the development of the national cadastral system.

Tell us about the production circuit of the land title at the National Agency for Domain and Land.

How effective is the LADM in the production, management and overall operation of the cadastral system?

Section# 2: questions for land data producers

How do you, surveyors, topographers, make the link between land administration and land buyers?

As surveyors, topographers, what tools do you use in the production of land data?

As a land manager, tell us about the importance of the national cadastral system compared to the information system.

Section #3: Question to project beneficiaries

Tell us about your knowledge of procedures for confirming land rights

What land issues do you encounter?

What importance should be given to the national Registry project?

Appendix B

System and data production

Figure A1.

Land Administration Domain Model (LADM) on application.

Figure A1.

Land Administration Domain Model (LADM) on application.

Figure A2.

Cadastral plan displayed for the population.

Figure A2.

Cadastral plan displayed for the population.

Notes

| 1 |

According to the African Development Bank, the SAP covered a period from 1989 to 1995 |

| 2 |

Boni Yayi is the president of Benin from 2006 to 2016 |

| 3 |

Current presidency of Patrice Talon |

References

- Hassenteufeul, P. Sociologie politique : l’action publique. Hassenteufel P. (dir.), Armand Colin, France, 2011 ; p. 318, https//hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-00814391.

- Pisani, E. Utopie foncière : l’espace pour l’homme, Gaillimard, Paris, 1977 ; Vol. 1, p. 212.

- Natacha, A. Les marchés fonciers à l’épreuve de la mondialisation, nouveaux enjeux pour la théorie économique et pour les politiques publiques, Sciences de l’Homme et de la Société, Université Lumière-Lyon II, 2005, p.211, https://tel.archives-ouvertes.fr/tel-00394000.

- Simmoneau,C. Gérer la ville au Bénin : La mise en œuvre du Registre foncier urbain à Cotonou, Porto-Novo et Bohicon, Thèse présentée à la Faculté de l’Aménagement en vue de l’obtention du grade de Ph.D, Aménagement, Université de Montréal, 2015.

- Rapport Groupehuit. Mission d’évaluation du fonctionnement des Registres Fonciers Urbains (RFU) des communes de Cotonou, Parakou, Porto-Novo et Kandi, Cotonou, République du Bénin, 2017.

- Guinin Asso, I. Appropriation et efficacité des approches de sécurisation du foncier rural au nord du Bénin, Thèse présenté pour l’obtention du grade de docteur, sociologie des ressources naturelles, Université de Parakou, 2022.

- Mekking,S.; Kougblenou, D. V.; Vranken, M., Kossou, F. G.; Van Der Berg, C. Upscaling Land Administration in Benin Towards National Coverage Balancing Between Time, Quality and Costs. FIG e-Working Week 2021.

- Programme des Nations Unies pour le Développement. Bonne gouvernance et développement durable, Rapport sur le Développement Humain du Burundi ; Gouvernement du Burundi, 2009.

- Ministère d’Etat chargé du Plan et du Développement. Plan National du Développement, 2018-2025, République du Bénin ; 2018.

- Dubois, V. l’Etat, l’action publique et la sociologie des champs, Revue Suisse de Science politique, 2014, 20(1), 25-30, https://tel.archives-ouvertes.fr/tel-00394000.

- Levêque, A. La sociologie de l’action publique In : (Chp. 2) Espitémologie de la sociologie. Paradigmes pour le XXIè siècle, Editions De Boeck, Bruxelles, Belgique, 2008, pp. 53-67, https://hdl.handle.net/2268/87215.

- Muller, P. Esquisse d’une théorie du changement dans l’action publique : Structures, acteurs et cadres cognitifs. Revue française de science politique,2005, 55, 155-187, https://www.cairn.info/revue-francaise-de-science-politique-2005-1-page-155.htm.

- République du Bénin/Conseil Economique et Social. Le foncier au Bénin : Problèmes domaniaux et perspectives. Rapport d’étude, juillet 2005, Assemblée Nationale.

- Rapport MCA-Bénin. Projet Accès au Foncier : Etude sur la politique et l’administration foncières, République du Bénin, 2009.

- Ministère de l’urbanisme, de l’habitat, de la réforme foncière et de la lutte contre l’érosion côtière. Livre blanc de politique foncière et domaniale, République du Bénin, 2011.

- Le Meur, P-Y. Approche qualitative de la question foncière : note méthodologique. Ird Refo, 2002, 4, 2-23.

- Boulier, F. Intégration d’outils et de méthodes MARP dans une démarche globale d’analyse du milieu rural. Application à l’étude de la diversité des stratégies paysannes dans la zone de Koba (Guinée). Contribution au programme ICRA 1993, Montpellier France, ICRA, 1993.

- Loi n° 2013-01 du 14 août 2013 portant Code Foncier et Domanial en République du Bénin, (http://www.droit-afrique.com/upload/doc/benin/Benin-Code-foncier-domanial-2013.pdf.

- Ekpodessi, S. N. G.; Nakamura, H. Land use and management in Benin Republic: An evaluation of the effectiveness of Land Law 2013-01. Land Use Policy, 2018, 78, 61-69.

- Lavigne Delville, P. Analyzing the Benin Land Law: An alternative viewpoint of progress. Land Use Policy, 2020, 94, p. 3.

- Loi n° 2017-15 du 10 août 2017 modifiant et complétant la loi n° 2013-01 du 14 août portant Code Foncier et Domanial en République du Bénin.

- Décret n° 2015-405 du 20 juillet 2015 portant nomination du président et des membres du Conseil d’Administration de l’Agence Nationale du Domaine et d Foncier (ANDF).

- Décret n° 2016-726 du 25 novembre 2016 portant création, organisation, attributions et fonctionnement du comité technique de supervision de la réalisation du cadastre national.

- Iso/Tc211. Geographic information - Land administration domain model (LADM). First Edition 2012–12-01. Lysaker, Norway: ISO: 118 p., https://www.iso.org/standard/51206.html. landusepol.2015.01.014.

- Lemmen, C.; Van Oosterom, P.; Bennett, R. The land administration domain model. Land use policy, 2015, 49, 535–545. https://doi.org/10.1016/j. [CrossRef]

- Van Oosterom, P.J.M.; Lemmen, C.H.J. The Land Administration Domain Model (LADM): Motivation, standardisation, application and further development. Land Use Policy, 49, 2015, 527 – 534. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landusepol.2015.09.032. [CrossRef]

- Van Oosterom, P.J.M.; Unger, E.-M.; Lemmen, C.H.J. The second themed article collection on the land administration domain model (LADM). Land Use Policy, 2022, 120. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landusepol.2022.106287. [CrossRef]

- Unger, E-M.; Lemmen C.; Bennett R. Women’s access to land and the Land Administration Domain Model (LADM) : Requirements, modelling and assesment », Land Use Policy, 2023, 126, 1- 15, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landusepol.2023.106538. [CrossRef]

- Polat, A. Z.; Alkan, M.; Sürmeneli G. H. Determining strategies for a cadastre 2034 vision using an AHP-Based SWOT analysis : A case study for the turkish cadastral and land administration system. Land Use Policy, 2017, 67, 151-166, http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.landusepol.2017.05.004. [CrossRef]

- Rocard, M. Le développement de l’Afrique, affaire de volonté politique. Etudes, 2003, 398, 21-31, https://www.cairn.info/revue-etudes-2003-1-page-21.htm.

- Simoulin, V., Quand ambition ne rime pas avec réalisation : l’action publique face aux limites de la volonté politique. Sciences de la société, 2010, 79, 145-158, https://doi.org/10.4000/sds.2823. [CrossRef]

- Lavigne Delville, P. Un projet de développement qui n’aurait jamais dû réussir ? la réhabilitation des polders de Prey Nup (Cambodge). Anthropologie et développement, 2015, 42-43, 59-84, https://doi.org/10.4000/anthropodev.366. [CrossRef]

- Williamson, P. I. Cadastral and Land Information Systems in Developing Countries. Australian Surveyor, 1986, 33 n° 1, 27-43, https://doi.org/10.1080/00050326.1986.1043520. [CrossRef]

- Williamson, I. P. The justification of cadastral systems in developing countries. Geomatica,, 1997, 51, 21-36, http://hdl.handle.net/11343/34003.

- Österberg, T. The Importance of Cadastral Procedures for Sustainable Development. Cadastral Innovation II, FIG XXII International Congress, Washington, D. C. USA, 2002.

- Williamson, P. I. Land administration “best practice” providing the infrastructure for land policy implementation. Land Use Policy, 2001, 18, 297-307, www.elsevier.com/locate/landusepol.

- Cemellini, B.; Van Oosterom, P.; Thompson, R.; de Vries M. Design, development and usability testing of an LADM compliant 3D Cadastral prototype system. Land Use Policy, 2019, article in press.

- Zhuo, Y.; Ma Z.; Lemmen C.; Bennett M. R.; Application of LADM for the integration of land and housing information in China: The legal dimension. Land Use Policy, 2015, 49, 634-648, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landusepol.2015.09.005. [CrossRef]

- van Oosterom, P.; Lemmen C.; Ingarvsson, T.; van der Molen, P.; Ploeger H.; Quak, W.; Stoter J.; Zevenbergen J. The core cadastral domain model. Computers, Environnment and Urban Systems, 2006, 30, 5, 627-660. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compenvurbsys.2005.12.002. [CrossRef]

- de Soto, H. le Mystère du capital : pourquoi le capitalisme triomphe en Occident et échoue partout ailleurs. Flammarion, Paris, France 2005; pp. 1-304.

- Lavigne Delville, P. ; Saïah C. Politiques foncières et mobilisation sociale au Bénin, des organisations de la société civile face au Code domanial et foncier. Les Cahiers du pôle foncier, 2016, 14, 1-57, www.horizon.documentation.ird.fr.

- Aditya, T.; Santosa, B. P.; Yulaihkah, Y.; Widjajanti, N.; Atunggal, D.; Sulistyawati, M. Title validation and collaborative mapping to accelerate quality assurance of land registration. Land Use Policy, 2021, 109, 2-14, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landusepol.2021.105689. [CrossRef]

- Hull, S.; Whittal J. Human rights in tension: guiding cadastral systems development in customary land rights contexts. Survey Review, 2017, 1-17, https://doi.org/10.1080/00396265.2017.1381396. [CrossRef]

- Dumas, A. Participation et projets de développement. Tiers-Monde, 1983, 95, 513-536. https://doi.org/10.3406/tiers.1983.4306. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).