1. Introduction

Obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) is considered a public health problem associated with decreased quality of life and productivity, along with increased morbimortality due to cardiovascular disease, metabolic problems or even cancer, in addition to increased motor vehicles accidents[

1]. Even though the standard treatment for OSA is positive upper airway pressure during the night, compliance is suboptimal in many patients, therefore alternative treatments are needed. These alternative treatments include positional therapy, myofunctional therapy, intraoral devices, bone and soft tissue surgery, and hypoglossal nerve stimulation. In the present time, any of these could be the first choice depending on the patient’s characteristics and preferences[

2].

In recent years, there has been a shift in pharyngoplasty techniques from the resection of the edge of the soft palate and uvula towards remodeling techniques where the mucosa is spared, muscles can be transposed or elevated without resection, and the fat of the supratonsilar fossa might be resected or ablated[

3]. The use of barbed sutures instead of the classic resorbable sutures has the advantage of avoiding knots inside the oral cavity and distributing the tension along the thread instead of one spot[

4].

Different modalities of pharyngoplasty have been described since the first publications with barbed sutures[

4,

5,

6]. The use of this thread does not imply a specific technique, it is a tool that can be incorporated into different pharyngoplasties depending on the anatomical characteristics of the patient and the collapse observed in drug-induced sleep endoscopy (DISE). Moreover, the use of barbed sutures has shown to have similar results as expansion pharyngoplasty, with shorter surgical time and a low learning curve[

7].

As part of the collaboration between the two centers, it was noticed that there were modifications in the barbed technique between them, therefore we wanted to know if these changes could lead to better outcomes.

2. Materials and Methods

This is a retrospective study of consecutive adult patients operated on between 2014 and 2019 with barbed sutures in the Otolaryngology departments of two university hospitals (Ospedale Morgagni-Pierantoni in Forlí, Italy, and University Hospital Dr. Peset in Valencia, Spain). All patients signed an informed consent before surgery. Local ethics approval was not necessary as this was a retrospective non-interventional study.

The pharyngoplasty technique performed by the Italian team was the barbed reposition pharyngoplasty (BRP)[

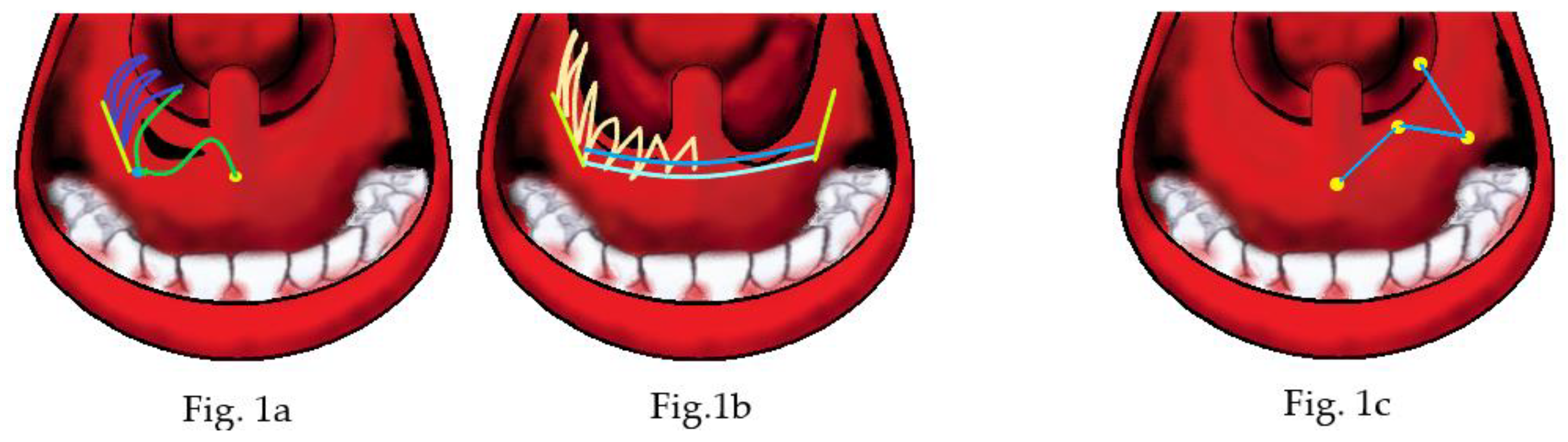

4]. Briefly, after tonsillectomy and weakening of the palatopharyngeus muscle in the lower part of the tonsillar fossa, using a bidirectional barbed suture, a needle was introduced at the center point and then passed laterally within the palate. The needle is reintroduced again close to point of exit, passing around the pterygomandibular raphe, until it comes out into the tonsillectomy bed, then through the upper part of the palatopharyngeus muscle, and comes out near the mucosa of the posterior pillar, without passing through it (

Figure 1c). The posterior pillar is entered at the junction between the upper third and the lower two-thirds. The needle is then passed back through the tonsillectomy bed and this suture is again suspended around the raphe; gentle traction is applied on the thread every time it exits the mouth. Finally, the thread is cut in the upper part of the palate.

The Spanish team performed a modified BRP. After dissection and extraction of the supratonsilar fat[

8], the technique starts the same way as the BRP with the difference of the needle coming out of the hole created, 3 loops are performed between the PP and the pterigomandibular raphe, the rest of the thread is used to close the wound in the soft palate performing zig-zag sutures crossing the palate from the junction of the hard palate till the rim of the soft palate near the uvula[

9] . Additionally, raphe to raphe sutures could be performed if there was any thread left (

Figure 1a,b)

Inclusion criteria were adult patients operated on with a sleep study before and 3 to 6 months after surgery. Exclusion criteria were the absence of a sleep study before or after surgery. Patients in whom multilevel surgery was performed were also included. Multilevel surgery consisted of transoral robotic surgery in the Forlí team and coblation tongue base resection in the Valencia team. Septoplasty and radiofrequency turbinate reduction were performed according to the patient’s need.

The data analyzed were age, body mass index (BMI), tonsillar grade according to the Friedman scale, Epworth sleepiness scale (ESS), nasal or multilevel surgery performed in addition to the barbed pharyngoplasty and the data from pre- and postoperative sleep studies.

Several definitions of success were considered according to the postoperative AHI obtained (<5, <10, <15, and the classical Sher’s definition). Moreover, the pre and post (delta) difference (calculated AHI pre -AHI post) and the relative delta (AHI pre-AHI post/AHI pre x100) were obtained. The relative delta AHI has the advantage of knowing the percentage of reduction in the severity of OSA, providing a number easy to understand for both patients and doctors, independent of the initial AHI.

For the statistical study, the program Stata v12 was used. Continuous variables were compared with a t-paired test between pre and post in each center and with t-test between centers. p <0.05 was considered significant. In addition, a regression model with ANCOVA was constructed with the significant variables comparing the postoperative results between centers.

3. Results

The final sample size was 138 patients (70 from Forlí and 68 from Valencia). The main characteristics of the patients operated on in each center are shown in

Table 1. Patients from Forlí were older than those from Valencia; however, there were no significant differences in the mean BMI and ESS.

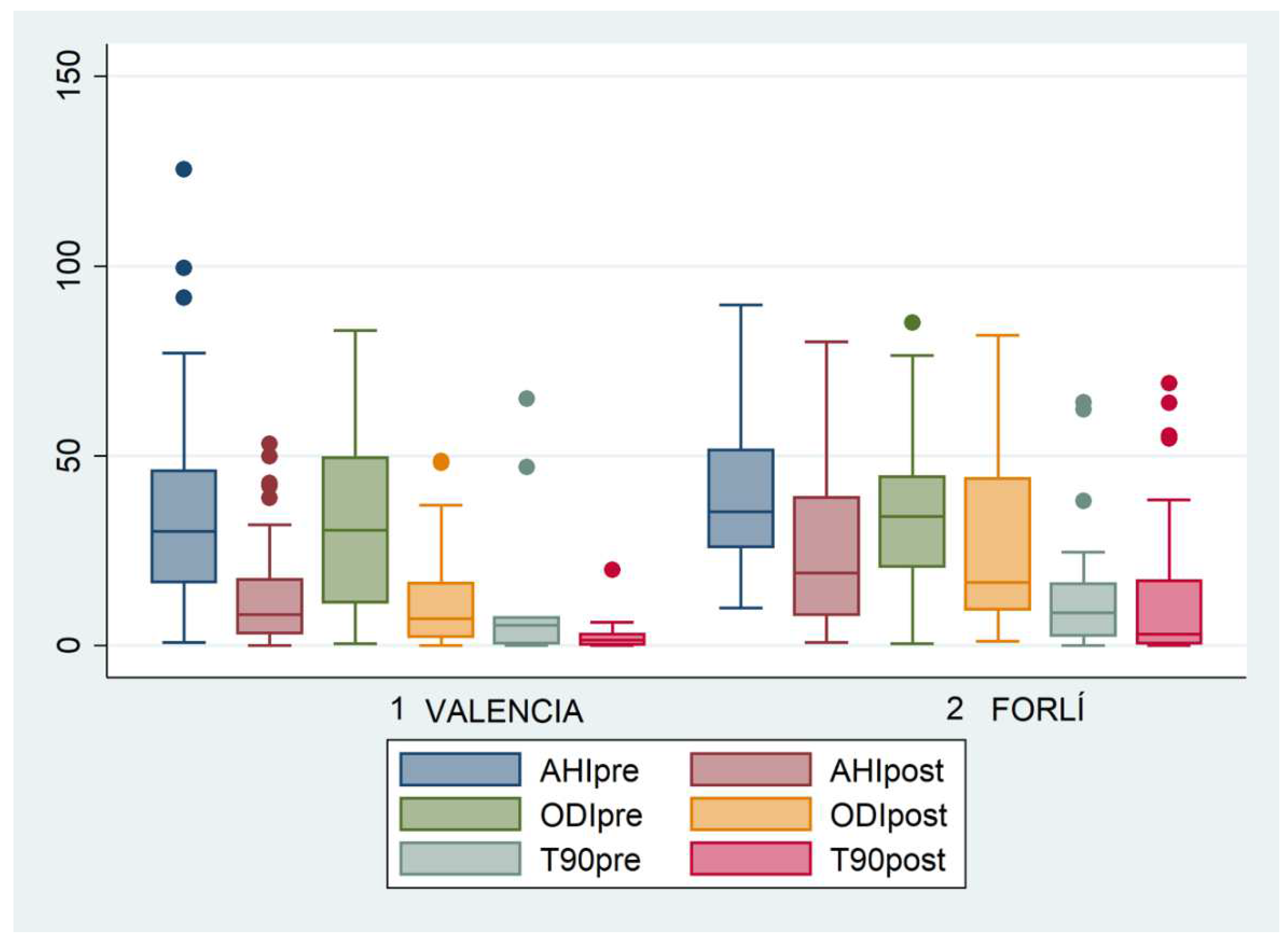

In both series, there was a significant improvement in OSA patients, with significant reductions in the respiratory events unrelated to a BMI reduction, as can be observed in

Figure 2.

When both series were compared, the patients from Valencia had better outcomes in general. According to the different success rates, in Valencia, the results were better as can be observed in

Table 2.

There was a difference in the proportion of tonsil hypertrophy, but the delta AHI was different between centers (

Table 3).

The proportion of nasal or multilevel surgeries performed in both centers was compared to find an explanation for this difference in success rates.

Table 4 shows that, although there were no differences in the number of tonsillectomies, Forlí series had more multilevel and nasal surgeries performed.

A regression model was performed with ANCOVA, showing that the results in Valencia were 11.41 e/h better (

Table 5); after adjusting the model, this difference was reduced but still significant (

Table 6).

4. Discussion

The use of barbed sutures to perform non-resective pharyngoplasties has shown to be useful and to reduce OSA severity and patient sleepiness in both centers, however, the number of loops performed in the LPW and the soft palate may help improve surgical success rates. The study performed by Barbieri et al.[

10], in which an increased surgical rate was obtained by adding a raphe-to-raphe suture in the soft palate to their previous technique supports this theory. Moreover, the intraoperative changes of the different steps with the sutures in one of Valencia’s patients can be observed in Video 1. Apparently, the zig-zag suture performed in the soft palate helps to open the velopharynx in the anteroposterior dimension even more than the raphe-to-raphe sutures, which could help explain the difference in success rates.

Furthermore, even though the long-term effect of these two types of pharyngoplasty with barbed sutures was not assessed, it has been suggested that modern pharyngoplasties that do not resect the free edge of the soft palate have better long-term success rates than classic UPPP[

11], and expansion pharyngoplasty and barbed pharyngoplasty appear to be equal in short-term success rate[

7], therefore, it could be plausible that the better results of the barbed pharyngoplasty with more loops continue in the long-term. This will be the goal of further studies, however, if confirmed, it would overcome the problem of being more time consuming, as the more loops performed the longer it takes and the more expensive it is in operating room time.

Having said this, this initial result must be confirmed in future prospective studies given that in the Valencia group there was a higher proportion of patients with tonsillar hypertrophy, which may explain this difference. In addition, the higher proportion of multilevel and nasal surgeries performed in Forlí may indicate a selection bias, the Forlí population being more complex, therefore with a lower success rate from the start.

Another limitation, due to the retrospective nature of the study, is that the DISE data were not available before surgery for all patients. It is unknown whether the group from Forlí had a higher incidence of multilevel or velum complete concentric collapse associated with lower success rates[

12,

13,

14].

Furthermore, Friedman’s Palate Position (FPP), also known as Modified Mallampati Index, could not be recovered from all the patients, therefore success rates cannot be compared with previous series and comparability between our series according to this issue is uncertain. Higher FPP is associated with lower success rates[

15]. Likewise, the objective tonsil volume measured after tonsillectomy is missing. As pointed out by Sundman and Friberg[

16,

17], even the tonsil size measured with the Friedman scale does not show high concordance amongst different explorers in the same center. This low concordance could be also low between our centers, despite the fact that both centers have experienced doctors dedicated to OSA patients. The objective tonsil volume could have resolved this limitation.

In addition, the Forlí group was older than the Valencia group, which could also be part of the better results in Valencia, even though after adjustment there were still significantly better results.

In conclusion, performing a higher number of loops in the LPW and soft palate may be responsible for the outcomes in Valencia’s OSA patients. However, all the limitations mentioned may also explain this apparently better result and the difference could be caused by these biases and not the surgical technique, therefore this hypothesis must be confirmed in future prospective studies.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org. Video S1: Intraoperative changes in modified barbed reposition pharyngoplasty.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.C.L. and C.V.; methodology, P.M.R.A. and G.C.; software, M.C.L., E.G.T., M.M.M., and F.D.C.; validation, M.C.L., P.M.R.A., G.C., and C.V.; formal analysis, M.C.L. and P.M.R.A..; investigation, P.M.R.A. and G.C.; resources, M.C.L. and C.V.; data curation, P.M.R.A., E.G.T., M.M.M and G.C.; writing—original draft preparation, M.C.L.; writing—review and editing, M.C.L. and C.V.; project administration, M.C.L. and C.V. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The institutional review approval was not necessary as this was a retrospective study performed with databases previously approved for other studies.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study before surgery.

Data Availability Statement

Raw data of this study will be provided upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

In this section, you can acknowledge any support given which is not covered by the author contribution or funding sections. This may include administrative and technical support, or donations in kind (e.g., materials used for experiments).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Chang, J.L.; Goldberg, A.N.; Alt, J.A.; Mohammed, A.; Ashbrook, L.; Auckley, D.; Ayappa, I.; Bakhtiar, H.; Barrera, J.E.; Bartley, B.L.; et al. International Consensus Statement on Obstructive Sleep Apnea. Int Forum Allergy Rhinol. 2022. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mediano, O.; González Mangado, N.; Montserrat, J.M.; Alonso-Álvarez, M.L.; Almendros, I.; Alonso-Fernández, A.; Barbé, F.; Borsini, E.; Caballero-Eraso, C.; Cano-Pumarega, I.; et al. International Consensus Document on Obstructive Sleep Apnea. Arch Bronconeumol (Engl Ed) 2021, S0300-2896(21)00115-0. [CrossRef]

- Li, H.-Y.; Lee, L.-A.; Hsin, L.-J.; Fang, T.-J.; Lin, W.-N.; Chen, H.-C.; Lu, Y.-A.; Lee, Y.-C.; Tsai, M.-S.; Tsai, Y.-T. Intrapharyngeal Surgery with Integrated Treatment for Obstructive Sleep Apnea. Biomed J 2019, 42, 84–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vicini, C.; Hendawy, E.; Campanini, A.; Eesa, M.; Bahgat, A.; AlGhamdi, S.; Meccariello, G.; DeVito, A.; Montevecchi, F.; Mantovani, M. Barbed Reposition Pharyngoplasty (BRP) for OSAHS: A Feasibility, Safety, Efficacy and Teachability Pilot Study. “We Are on the Giant’s Shoulders.” Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol 2015, 272, 3065–3070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mantovani, M.; Minetti, A.; Torretta, S.; Pincherle, A.; Tassone, G.; Pignataro, L. The “Barbed Roman Blinds” Technique: A Step Forward. Acta Otorhinolaryngol Ital 2013, 33, 128. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Salamanca, F.; Costantini, F.; Mantovani, M.; Bianchi, A.; Amaina, T.; Colombo, E.; Zibordi, F. Barbed Anterior Pharyngoplasty: An Evolution of Anterior Palatoplasty. Acta Otorhinolaryngol Ital 2014, 34, 434–438. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Neruntarat, C.; Khuancharee, K.; Saengthong, P. Barbed Reposition Pharyngoplasty versus Expansion Sphincter Pharyngoplasty: A Meta-Analysis. Laryngoscope 2020. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olszewska, E.; Woodson, B.T. Palatal Anatomy for Sleep Apnea Surgery. Laryngoscope Investig Otolaryngol 2019, 4, 181–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carrasco Llatas, M.; Valenzuela Gras, M.; Martínez Ruiz de Apodaca, P.; Dalmau Galofre, J. Modified Reposition Pharyngoplasty for OSAS Treatment: How We Do It and Our Results. Acta Otorrinolaringologica Espanola 2020. [CrossRef]

- Barbieri, M.; Missale, F.; Incandela, F.; Fragale, M.; Barbieri, A.; Roustan, V.; Canevari, F.R.; Peretti, G. Barbed Suspension Pharyngoplasty for Treatment of Lateral Pharyngeal Wall and Palatal Collapse in Patients Affected by OSAHS. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol 2019, 276, 1829–1835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martínez Ruiz de Apodaca, P.; Carrasco Llatas, M.; Valenzuela Gras, M.; Dalmau Galofre, J. Improving Surgical Results in Velopharyngeal Surgery: Our Experience in the Last Decade. Acta Otorrinolaringol Esp 2019. [CrossRef]

- Hsu, Y.-S.; Jacobowitz, O. Does Sleep Endoscopy Staging Pattern Correlate With Outcome of Advanced Palatopharyngoplasty for Moderate to Severe Obstructive Sleep Apnea? J Clin Sleep Med 2017, 13, 1137–1144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, H.-S.; Rowley, J.A.; Folbe, A.J.; Yoo, G.H.; Badr, M.S.; Chen, W. Transoral Robotic Surgery for Treatment of Obstructive Sleep Apnea: Factors Predicting Surgical Response. Laryngoscope 2015, 125, 1013–1020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, J.H.; Lee, J.Y.; Cha, J.; Kim, K.; Hong, S.-N.; Lee, S.H. Predictive Models of Objective Oropharyngeal OSA Surgery Outcomes: Success Rate and AHI Reduction Ratio. PLoS One 2017, 12, e0185201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Friedman, M.; Hwang, M.S. Evaluation of the Patient with Obstructive Sleep Apnea: Friedman Tongue Position and Staging. Operative Techniques in Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery 2015, 26, 85–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sundman, J.; Bring, J.; Friberg, D. Poor Interexaminer Agreement on Friedman Tongue Position. Acta Otolaryngol 2017, 137, 554–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sundman, J.; Fehrm, J.; Friberg, D. Low Inter-Examiner Agreement of the Friedman Staging System Indicating Limited Value in Patient Selection. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol 2018, 275, 1541–1545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).