Submitted:

08 May 2023

Posted:

09 May 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. The CLE as Complex Adaptive Systems

1.2. Managers’ Approaches to Influencing Complex Systems

1.3. Basic Nursing and Placement Learning

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Design

2.2. Context, Participants, and Settings

2.3. Data Collection

2.4. Analysis

2.5. Recruitment and Ethics

3. Results

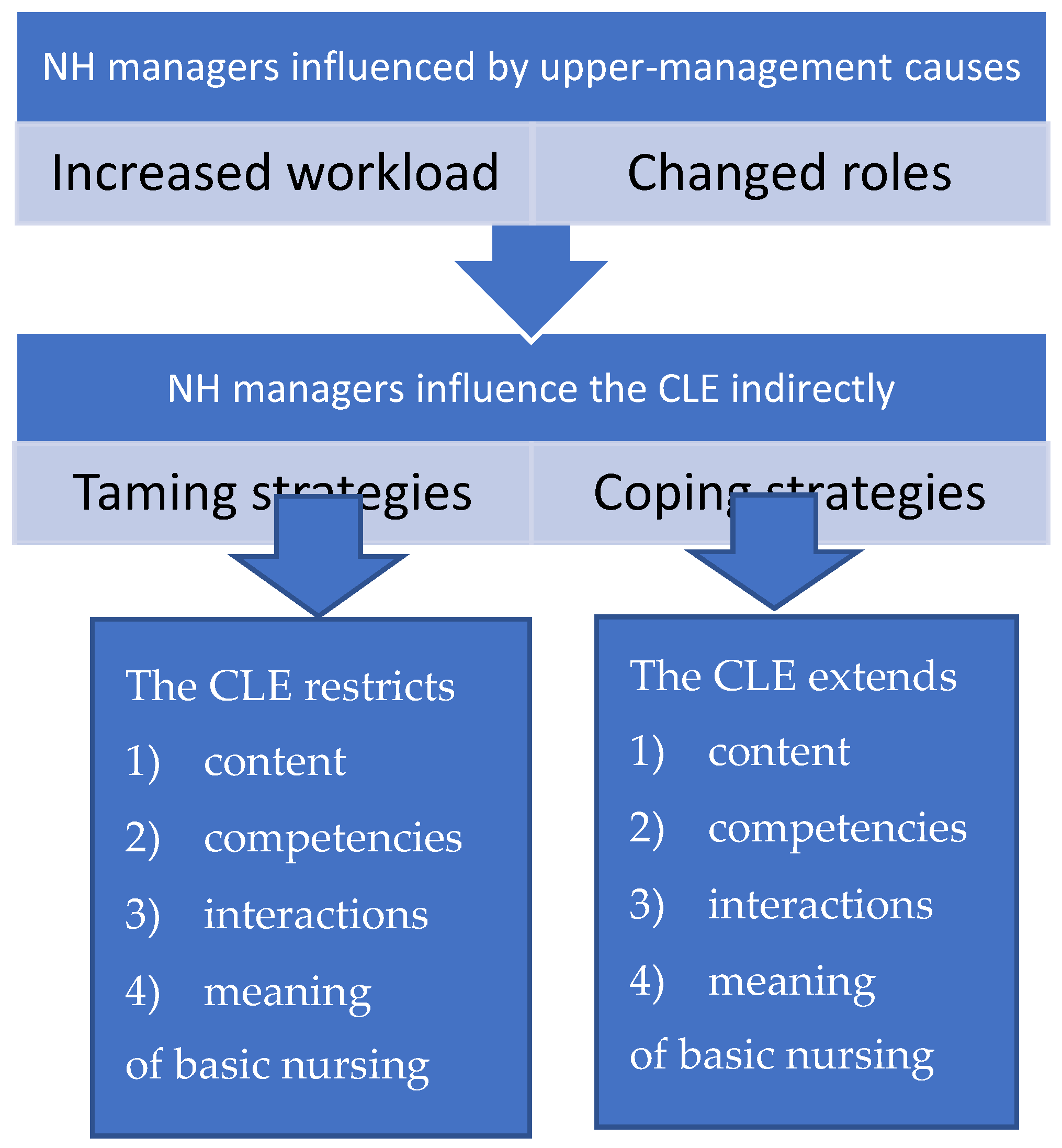

3.1. The Overall Theme: A Constant Struggle to Keep Work Manageable

3.2. Main Theme 1: We Cannot Always be There for Them

3.2.1. Subtheme A: “Keep Organizing Basic Nursing Yourself.”

3.2.2. Subtheme B: “Keep Work Simple.”

3.3. Main Theme 2: The CLE Simplified Basic Nursing to Make Work Manageable

3.3.1. Subtheme A: “Basic Nursing Is Practical Assistance with Everyday Tasks.”

3.3.2. Subtheme B: “Basic Nursing Is the Associate’s and Assistant’s Domain.”

3.3.3. Subtheme C: “Basic Nursing Work Should Be Evenly Distributed and Carried Out without Delay.”

3.4. Main Theme 3: IPLT—An Enrichment of the CLE

3.4.1. Subtheme A: “The Interprofessional Learning Team Is the Future.”

3.4.2. Subtheme B: “Maybe We Do Not Pay Attention to the Right Things.”

4. Discussion

4.1. Methodological Considerations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- WHO. Ageing and health2022. Available from: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/ageing-and-health.

- Haugan G. Nurse-Patient Interaction: A Vital Salutogenic Resource in Nursing Home Care. 2021. In: Health Promotion in Health Care – Vital Theories and Research [Internet]. Cham: Springer International Publishing : Imprint: Springer. 1st 2021.

- WHO. Health workforce requirements for universal health coverage and the sustainable development goals World Health Organization; 2016.

- Cooke J, Greenway K, Schutz S. Learning from nursing students' experiences and perceptions of their clinical placements in nursing homes: An integrative literature review. Nurse Educ Today. 2021;100:104857. [CrossRef]

- Husebo AML, Storm M, Vaga BB, Rosenberg A, Akerjordet K. Status of knowledge on student-learning environments in nursing homes: A mixed-method systematic review. J Clin Nurs. 2018;27(7-8):e1344-e59.

- Splitgerber H, Davies S, Laker S. Improving clinical experiences for nursing students in nursing homes: An integrative literature review. Nurse Educ Pract. 2021;52:103008. [CrossRef]

- Saarikoski M. The Main Elements of Clinical Learning in Healthcare Education. In: Saarikoski M, Strandell-Laine C, editors. The CLES-Scale: An Evaluation Tool for Healthcare Education. Cham: Springer International Publishing; 2018. p. 7-15.

- Anderson RA, Issel LM, McDaniel Jr RR. Nursing homes as complex adaptive systems: relationship between management practice and resident outcomes. Nursing research. 2003;52, 12.

- Cilliers P. Complexity and Postmodernism: Understanding Complex Systems. London: London: Routledge; 1998. [CrossRef]

- Kristiansen M, Westeren KI, Obstfelder A, Lotherington AT. Coping with increased managerial tasks: tensions and dilemmas in nursing leadership. Journal of Research in Nursing. 2016b;21, 492-502. [CrossRef]

- Orellana K, Manthorpe J, Moriarty J. What do we know about care home managers? Findings of a scoping review. Health Soc Care Community. 2017;25, 366-77. [CrossRef]

- Athlin E, Hov R, Petzäll K, Hedelin B. Being a nurse leader in bedside nursing in hospital and community care contexts in Norway and Sweden. 2014. [CrossRef]

- Raisio H, Puustinen A, Vartiainen P. The Concept of Wicked Problems. Improving the Understanding of Managing Problem Wickedness in Health and Social Care. 2018. In: The Management of Wicked Problems in Health and Social Care [Internet]. New York: Routledge; [18].

- Northouse PG, Northouse PG. Leadership : theory and practice. Ninth Edition. ed. Thousand Oaks, California: SAGE Publishing; 2022.

- Uhl-Bien M, Arena M. Leadership for organizational adaptability: A theoretical synthesis and integrative framework. The Leadership Quarterly. 2018;29:89-104. [CrossRef]

- Joosse H, Teisman G. Employing complexity: complexification management for locked issues. Public Management Review. 2021;23, 843-64. [CrossRef]

- Kitson A, Conroy T, Wengstrom Y, Profetto-McGrath J, Robertson-Malt S. Defining the fundamentals of care. Int J Nurs Pract. 2010;16, 423-34. [CrossRef]

- Act relating to municipal Health and care services, etc, LOV-2011-06-24-30, (2011).

- The dignity guarantee. Regulation on dignified elderly care REG-2010-11-12-1426 2011. Available from: https://lovdata.no/dokument/SF/forskrift/2010-11-12-1426.

- Hoen BT, Abrahamsen DR. Sykehjem og hjemmetjenesten i Norge [Nursing Homes and Home Care Services in Norway]: Statistics Norway; 2023. Available from: https://www.ssb.no/helse/helsetjenester/artikler/sykehjem-og-hjemmetjenesten-i-norge.

- Backhaus R, Rossum Ev, Verbeek H, Halfens RJG, Tan FES, Capezuti E, et al. Work environment characteristics associated with quality of care in Dutch nursing homes: A cross-sectional study. International journal of nursing studies. 2017;66:15-22. [CrossRef]

- Ward A, McComb S. Precepting: A literature review. Journal of professional nursing : official journal of the American Association of Colleges of Nursing. 2017;33, 314-25.

- Tuomikoski AM, Ruotsalainen H, Mikkonen K, Kaariainen M. Nurses' experiences of their competence at mentoring nursing students during clinical practice: A systematic review of qualitative studies. Nurse Educ Today. 2020;85:104258. [CrossRef]

- Pramila-Savukoski S, Juntunen J, Tuomikoski A-M, Kääriäinen M, Tomietto M, Kaučič BM, et al. Mentors' self-assessed competence in mentoring nursing students in clinical practice: A systematic review of quantitative studies. Journal of Clinical Nursing. 2020;29(5-6):684-705.

- Walker R, Cooke M, Henderson A, Creedy DK. Characteristics of leadership that influence clinical learning: a narrative review. Nurse Educ Today. 2011;31, 743-56. [CrossRef]

- Aase EL. Nurse managers’ importance for the learning environment of student nurses in nursing homes. Sykepleien Forskning. 2019. [CrossRef]

- Muller-Schoof I, Verbiest MEA, Stoop A, Snoeren M, Luijkx KG. How do practically trained (student) caregivers in nursing homes learn? A scoping review. Journal of Nursing Education and Practice. 2021. [CrossRef]

- Marshall C, Rossman GB. Designing qualitative research. 6th ed. Los Angeles, Calif: SAGE; 2016.

- Sørø VL, Aglen B, Orvik A, Søderstrøm S, Haugan G. Preceptorship of clinical learning in nursing homes – A qualitative study of influences of an interprofessional team intervention. Nurse Education Today. 2021;104:104986. [CrossRef]

- Orvik A, Larun L, Berland A, Ringsberg KC. Situational Factors in Focus Group Studies: A Systematic Review. International Journal of Qualitative Methods. 2013;12, 338-58. [CrossRef]

- Braun V, Clarke V. Thematic analysis : a practical guide. Los Angeles, California: SAGE; 2022. [CrossRef]

- Reeves S, Albert M, Kuper A, Hodges BD. Why use theories in qualitative research? BMJ. 2008;337:a949.

- Solbakken R, Bondas T, Kasén A. Relationships influencing caring in first-line nursing leadership: A visual hermeneutic study. Scand J Caring Sci. 2022;36, 957-68. [CrossRef]

- Havig AK, Hollister B. How Does Leadership Influence Quality of Care? Towards a Model of Leadership and the Organization of Work in Nursing Homes. Ageing International. 2018;43, 366-89. [CrossRef]

- Holm AL, Severinsson E. Effective nursing leadership of older persons in the community – a systematic review. Journal of Nursing Management. 2014;22, 211-24. [CrossRef]

- Bratt C, Gautun H. Should I stay or should I go? Nurses’ wishes to leave nursing homes and home nursing. Journal of Nursing Management. 2018;26, 1074-82. [CrossRef]

- Cronin U, McCarthy J, Cornally N. The Role, Education, and Experience of Health Care Assistants in End-of-Life Care in Long-Term Care: A Scoping Review. J Gerontol Nurs. 2020;46, 21-9. [CrossRef]

- Wakefield BJ. Facing up to the reality of missed care. BMJ Quality Safety. 2014;23, 92. [CrossRef]

- Myhre J, Saga S, Malmedal W, Ostaszkiewicz J, Nakrem S. Elder abuse and neglect: an overlooked patient safety issue. A focus group study of nursing home leaders’ perceptions of elder abuse and neglect. BMC Health Services Research. 2020;20(1).

- MacMillan K. The Hidden Curriculum: What Are We Actually Teaching about the Fundamentals of Care? Nursing leadership (Toronto, Ont). 2016;29, 37-46.

- Gustafsson N, Leino-Kilpi H, Prga I, Suhonen R, Stolt M. Missed Care from the Patient's Perspective - A Scoping Review. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2020;14:383-400.

- Recio-Saucedo A, Dall'Ora C, Maruotti A, Ball J, Briggs J, Meredith P, et al. What impact does nursing care left undone have on patient outcomes? Review of the literature. Journal of clinical nursing. 2018;27(11-12):2248-59. [CrossRef]

- Jones TL, Hamilton P, Murry N. Unfinished nursing care, missed care, and implicitly rationed care: State of the science review. International journal of nursing studies. 2015;52, 1121-37. [CrossRef]

- Myhre J, Malmedal WK, Saga S, Ostaszkiewicz J, Nakrem S. Nursing home leaders' perception of factors influencing the reporting of elder abuse and neglect: a qualitative study. Journal of Health Organization and Management. 2020;34, 655-71. [CrossRef]

- Myhre J, Saga S, Malmedal W, Ostaszkiewicz J, Nakrem S. React and act: a qualitative study of how nursing home leaders follow up on staff-to-resident abuse. BMC Health Services Research. 2020;20(1). [CrossRef]

- Kitson A, Muntlin Athlin A, Conroy T. Anything but Basic: Nursing's Challenge in Meeting Patients’ Fundamental Care Needs. Journal of Nursing Scholarship. 2014;46.

- Tveit B, Raustøl A. Lack of compassion or poor discretion? Ways of addressing malpractice. Nursing ethics. 2019;26, 471-9. [CrossRef]

- Armijo-Olivo S, Craig R, Corabian P, Guo B, Souri S, Tjosvold L. Nursing Staff Time and Care Quality in Long-Term Care Facilities: A Systematic Review. The Gerontologist. 2019;60, e200-e17. [CrossRef]

- Feo R, Kitson A, Conroy T. How fundamental aspects of nursing care are defined in the literature: A scoping review. Journal of Clinical Nursing. 2018;27(11-12):2189-229. [CrossRef]

- Eraut M. Improving the quality of work placements. 2011. In: Learning to be Professional through a Higher Education e-book [Internet]. Available from: http://learningtobeprofessional.pbworks.com/w/page/39548725/Improving%20the%20quality%20of%20work%20placements.

- Wu XV, Enskär K, Pua LH, Heng DGN, Wang W. Clinical nurse leaders' and academics' perspectives in clinical assessment of final-year nursing students: A qualitative study. Nursing & health sciences. 2017:287.

- Kukkonen P, Leino-Kilpi H, Koskinen S, Salminen L, Strandell-Laine C. Nurse managers' perceptions of the competence of newly graduated nurses: A scoping review. Journal of Nursing Management. 2020;28, 4-16. [CrossRef]

- Kavanagh JM, Szweda C. A Crisis in Competency: The Strategic and Ethical Imperative to Assessing New Graduate Nurses’ Clinical Reasoning. Nursing Education Perspectives. 2017;38, 57-62. [CrossRef]

- Juthberg C, Sundin K. Registered nurses’ and nurse assistants’ lived experience of troubled conscience in their work in elderly care—A phenomenological hermeneutic study. International journal of nursing studies. 2010;47, 20-9. [CrossRef]

- Corazzini KN, McConnell ES, Day L, Anderson RA, Mueller C, Vogelsmeier A, et al. Differentiating Scopes of Practice in Nursing Homes: Collaborating for Care. Journal of Nursing Regulation. 2015;6, 43-9. [CrossRef]

- Ellström PE. Practice-based innovation: a learning perspective. Journal of Workplace Learning. 2010;22(1/2):27-40. [CrossRef]

- Lindh Falk A, Hult H, Hammar M, Hopwood N, Abrandt Dahlgren M. Nursing assistants matters-An ethnographic study of knowledge sharing in interprofessional practice. Nursing inquiry. 2018;25, e12216.

- Geertz C. Thick description: toward an interpretive theory of culture. In: Geertz C, editor. The interpretation of Cultures - selected essays by Clifford Geertz. New York: Basic Books, Inc., Publishers; 1973. p. 3-30.

- Stenfors T, Kajamaa A, Bennett D. How to … assess the quality of qualitative research. The Clinical Teacher. 2020;17, 596-9. [CrossRef]

- Flick U. Doing Triangulation and Mixed Methods. 2018 2023/03/14. 55 City Road.

- 55 City Road, London: SAGE Publications Ltd. Available from: https://methods.sagepub.com/book/doing-triangulation-and-mixed-methods.

- Malterud K, Siersma VD, Guassora AD. Sample Size in Qualitative Interview Studies: Guided by Information Power. Qual Health Res. 2016;26, 1753-60.

| NH 1 | NH 2 | NH 3 | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unit managers | 1 | 1 | 1 | 3 |

| Ward managers | 1 | 2 | 1 | 4 |

| Wards | 1 | 2 | 2 | 5 |

| Number of patient rooms | 25 | 60 | 24 | 109 |

| Preceptors for students | 2 | 4 | 3 | 9 |

| Students | 6 | 4 | 4 | 14 |

| Preceptors for apprentices | 3 | 4 | 2 | 9 |

| Apprentices | 2 | 4 | 4 | 10 |

| Overall-theme “A constant struggle to keep work manageable” | |

| MAIN THEMES | SUB-THEMES |

| 1. We cannot always be there for them | A. Keep organizing basic nursing yourself. |

| B. Keep work simple. | |

| 2. The CLE simplified basic nursing to make work manageable | A. Basic nursing is practical assistance with everyday tasks. |

| B. Basic nursing is the associates and the assistant’s domain. | |

| C. Basic nursing work should be evenly distributed and carried out without delay. | |

| 3. IPLT—an enrichment of the CLE | A. The interprofessional learning team is the future. |

| B. Maybe we do not pay attention to the right things. | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).