1. Introduction

Prosociality refers to one’s tendency to act to benefit others and it comes in many ways, such as caring, sharing, and helping [

1]. As a major aspect of social competence, prosociality is critical to child and adolescent normative development [

2]. Research has shown that children and adolescents who exhibit more prosociality often report fewer internalizing symptoms, such as depressive and anxiety symptoms, and loneliness [

3,

4,

5]. These studies suggest that prosociality may serve as a protective factor against becoming psychologically maladjusted. Despite consistent evidence linking prosociality to better psychological functioning, the underlying mechanisms that help to account for these links remain under-investigated [

6]. Drawing from contextual-developmental perspectives [

7], and informed by prior research findings [

8,

9], this study explores the mediating effects of peer preference and self-perceived social competence in the relations between prosociality and psychological maladjustment among a large sample of Chinese children and adolescents.

1.1. Prosociality and Psychological Maladjustment

Engagement in prosocial behavior necessitates good emotion regulation and social-cognitive skills [

2]. For example, being prosocial requires the ability to regulate one’s negative feelings when observing another’s distress [

10]. Thus, the self-regulation abilities that prosocial children display may help them be less prone to emotional problems. A growing body of literature has examined the associations between prosociality and adolescent psychological maladjustment, such as depression and loneliness. For example, longitudinal studies show that prosociality predicted decreases in depressive symptoms in children and adolescents [

3,

11,

12]. A recent meta-analysis also supports that prosocial behavior is negatively related to internalizing problems including depression, although the effect is small [

6]. Similar to depression, children and adolescents with higher prosociality tend to experience lower levels of loneliness [

5,

13]. Taken together, this body of research has stressed that prosocial behavior can work as a protective factor for psychological well-being. However, how prosociality relates to adolescent psychological maladjustment remains relatively unclear. Understanding the underlying mechanisms of these relations may inform prevention and early intervention programs for internalizing problems by leveraging the strength of prosociality among children and adolescents.

1.2. Peer Preference and Self-Perceived Social Competence as Potential Mediators

In addition to direct relations, prosociality is likely to be related to decreased depressive symptoms and loneliness indirectly through peer preference and self-perceived social competence. According to the contextual-developmental perspective [

7], cultural values provide a basis for social evaluations of children’s behaviors, which may in turn shape children’s developmental outcomes. In Chinese society where interpersonal harmony is emphasized, prosocial behavior is highly encouraged and regarded as a behavioral virtue that contributes to effective group functioning [

14]. Accordingly, children with high prosociality are likely to receive positive feedback from their peers, as shown in higher peer preference (i.e., likeability) [

3,

7]. Being well-liked and preferred by peers may provide children with more opportunities to receive instrumental help and emotional support from peers, which ultimately contribute to their fewer internalizing problems, such as depressive symptoms and loneliness [

5,

15]. The mediating effect of peer preference on the relation between prosociality and psychological maladjustment has been investigated once. In this study, researchers found that children with high levels of prosociality were more preferred and well-liked by their peers, which in turn reduced their depressive symptoms [

3].

Aside from peer preference, self-perceived social competence may be the other potential mediator that can explain the relationship between prosociality and psychological maladjustment. Self-perceived social competence refers to one’s subjective perceptions of competence or adequacy in the social domain of functioning [

16]. Children’s social behaviors have long been linked to their self-perceived competence [

17,

18]. Prosocial children and adolescents may regard their sense of self, especially, their social selves, in a more favorable light. This is because taking prosocial actions may enable individuals to feel valued and needed by others, which bolsters feelings about the social self [

19]. Research has shown that prosociality is linked to higher levels of general self-worth and social worth [

19,

20]. Cognitive theories of internalizing disorders posit that individuals with adaptive self-schemas are less vulnerable to developing internalizing problems [

21,

22]. The positive self-perception is thus thought to protect children from developing psychological problems [

23,

24].

Peer preference and self-perceived social competence may mediate the relations between prosociality and psychological maladjustment in a serial manner. The competency-based model suggests that peer experiences, such as peer preference, may impact self-perceptions of one’s ability to function in the social domain (i.e., self-perceived social competence) [

23,

25]. As discussed above, prosocial adolescents are usually accepted and well-liked by peers [

3,

7], and they may integrate positive feedback from peers into their sense of social self, which leads them to perceive that they are socially accepted and competent. This, in turn, could mitigate the risk of experiencing depression and loneliness. Consistent with this theorizing, self-perceived social competence has been found to mediate the link between peer rejection and children’s internalizing problems [

26]. Accordingly, the relations between prosociality and psychological maladjustment might be serially mediated by peer preference and self-perceived social competence.

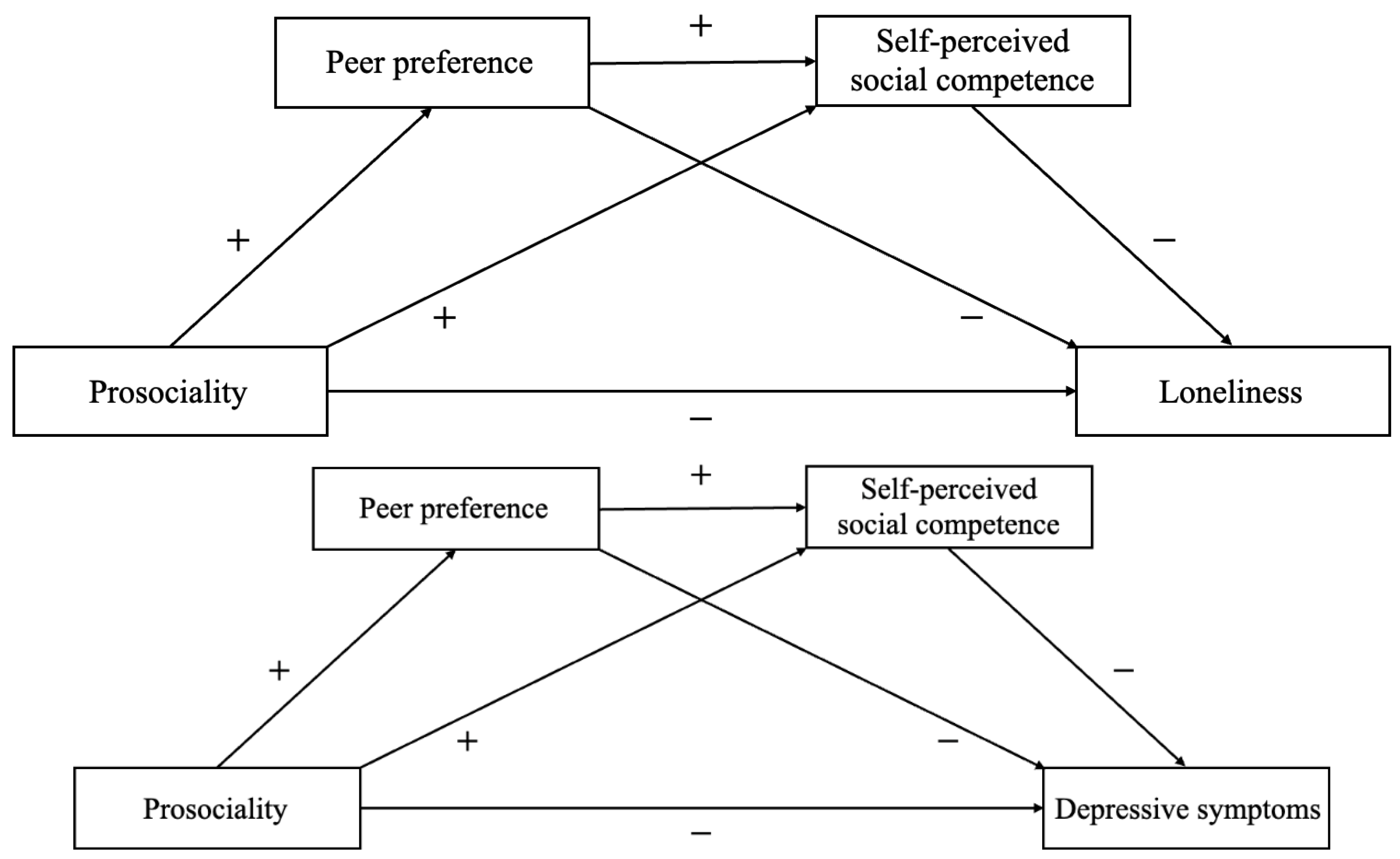

1.3. The Present Study

Although previous studies identified the direct effect of prosociality on psychological maladjustment (i.e., depressive symptoms and loneliness) among children and adolescents [

3,

4,

5], few examined the mechanisms that account for the relations. Therefore, the present study aimed to examine whether peer preference and self-perceived social competence act as mediators of the relations (see

Figure 1). Grounded on the relevant theories and empirical studies reviewed above, the present study proposes the following hypotheses: (a) peer preference and self-perceived social competence would mediate the relations between prosociality and depressive symptoms and loneliness in a parallel way. That is, prosociality would be related to higher peer preference, which in turn would be related to lower depressive symptoms and loneliness. In addition, prosociality would be related to higher self-perceived social competence, which in turn would be related to lower depressive symptoms and loneliness; and (b) peer preference and self-perceived social competence would mediate the relations between prosociality and depressive symptoms and loneliness in a serial way. That is, prosociality would be related to greater peer preference, which in turn would be related to higher levels of self-perceived social competence. Higher self-perceived social competence would then be related to decreased depressive symptoms and loneliness.

2. Method

2.1. Participants

Participants in this study were 951 students (Mage = 11 years, 442 girls) in Grades 3~7 from a primary school and a middle school in the urban area of Shanghai. The sample included 181 third graders (18.7%), 240 fourth graders (24.8%), 169 fifth graders (17.5%), 180 sixth graders (18.6%), and 181 seventh graders (18.7%). All participants in this sample were of the majority Han nationality.

2.2. Procedure

Students completed peer nominations and self-report measures that were group-administered during class time on a school day. The administration of the measures was carried out by trained researchers (i.e., graduate students). The Research Ethics Committee of the Shanghai Normal University approved this study, and it was carried out in compliance with the standards of the Declaration of Helsinki. Written informed consent was obtained from all students and their parents through the school before data collection.

2.3. Measures

2.3.1. Prosociality

Prosociality was measured using a peer-nomination measure adapted from the Revised Class Play [

27]. Consistent with the procedure outlined by Masten [

28], participants were asked to nominate up to three classmates who best fit each of the three descriptors assessing aspects of prosocial behavior (e.g., “Helps others when they need it”, “Is polite to others”). Both same-gender and cross-gender nominations were allowed and self-nominations were not allowed. Nominations each child received from all classmates for each item were totaled and standardized within the class to form an index of prosociality. The measure was used and shown to be reliable and valid in other studies with Chinese children [

29]. The internal reliability (Cronbach’s alphas) of the measure is 0.89 in this study.

2.3.2. Depressive Symptoms

Participants' depressive symptoms were assessed using a 14-item measure of the Children’s Depression Inventory (CDI) [

30]. Each item consists of three alternative responses (e.g., “I feel like crying every day”, “I feel like crying most days”, “I feel like crying once in a while”). Children were asked to choose one that best describes them in the past two weeks. Following the procedure outlined by Kovacs [

30], the average score of depressive symptoms was computed, with higher scores indicative of more depressive symptoms. The measure has been demonstrated to be reliable and valid in Chinese children [

3,

31,

32]. In this study, the internal consistency coefficient of the scale was 0.87.

2.3.3. Loneliness

Loneliness was assessed by a self-report measure, adapted from Asher [

33]. 16 items assess the individual's experiences with loneliness, such as feeling isolated, having few close relationships, or feeling left out. The average score of loneliness was computed, with higher scores indicative of greater feelings of loneliness. The measure has been demonstrated to be reliable and valid in Chinese children [

34,

35]. The internal consistency coefficient of the scale was 0.92 in this study.

2.3.4. Peer Preference

Participants were asked to nominate up to three classmates with whom they most liked to be (i.e., positive nominations) and three classmates with whom they least liked to be (i.e., negative nominations). Nominations received from all classmates were totaled and standardized within classrooms to account for different sizes of classes. Peer preference was calculated by subtracting negative nomination scores from positive nomination scores [

36]. The procedure has been used in Chinese children [

37,

38,

39].

2.3.5. Self-Perceived Social Competence

Students’ self-perceived social competence was assessed using the social competence subscale of the Self-Perception Profile for Children (SPPC) [

40]. The subscale consists of 6 items. Each item consists of two opposite descriptions (e.g., “Some kids know how to become popular” BUT “Other kids do not know how to become popular”). Children were asked to choose the description that best fits and then indicate whether the description is somewhat true or very true for them. Thus, each item is scored on a 4-point scale with a higher score reflecting a higher self-perceived social competence. The measure has been demonstrated to be reliable and valid in Chinese children [

41,

42]. The internal consistency coefficient of the scale in this study was 0.83.

2.4. Analytic Plan

Data were analyzed using SPSS 25.0 and SPSS PROCESS macro 4.0 software [

43]. Firstly, descriptive statistics and Pearson correlations were conducted for the main study variables. We then used the PROCESS macro to test the hypothesized multiple mediation models. In PROCESS, model 6 was applied to examine the mediating effect of peer preference and social self-perception on the associations between prosociality and psychological maladjustment. Mediation analyses were conducted using the 5000 bootstraps sampling method to generate 95% bias-corrected confidence intervals (CI) for all the indexes. When zero was not included in the 95% CI, the effects were considered statistically significant. Grade and gender were included in the models as covariates.

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive Statistics

Means and standard deviations for and intercorrelations among study variables are presented in

Table 1. The results showed that prosociality was positively correlated with self-perceived social competence and peer preference but negatively correlated with loneliness and depressive symptoms, whereas self-perceived social competence and peer preference were negatively correlated with loneliness and depressive symptoms.

A multivariate analysis of variance (MANOVA) was conducted to examine the overall effects of gender, grade, and their interactions on study variables. Results showed significant gender differences in peer preference, F (1, 891) = 12.45, p < 0.001, η2 = 0.01, and in prosociality, F (1, 891) = 51.77, p < 0.001, η2 = 0.05. Follow-up univariate analysis revealed that compared to boys, girls had higher scores on peer preference F (1, 891) = 15.13, p < 0.001, η2 = 0.01 and prosociality F (1, 891) = 58.32, p < 0.001, η2 = 0.05. Grade difference was found for depression, F (1, 891) = 11.78, p < 0.001, η2 = 0.05, and for loneliness, F (1, 891) = 2.81, p < 0.05, η2 = 0.05. There was no significant interaction effect between gender and grade.

3.2. Testing Multiple Mediation Models

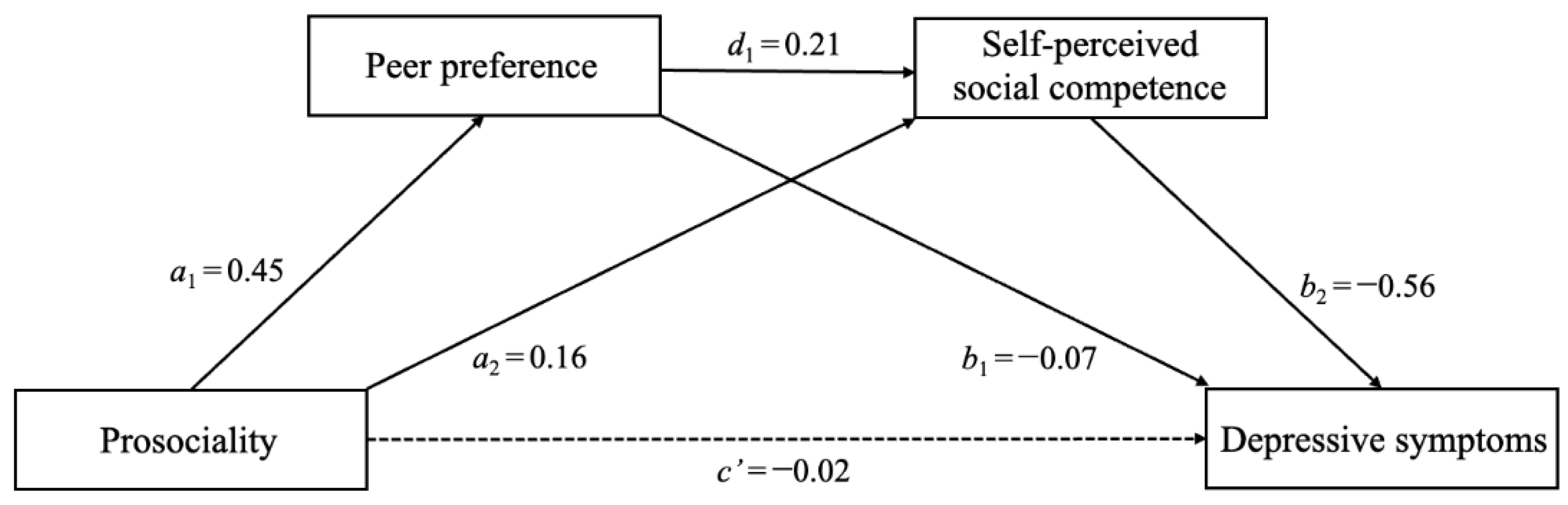

Model 6 of PROCESS was used to test our hypothesized multiple mediation models, with separate models evaluated for each dependent variable. The results of our models are shown in

Figure 2 and

Figure 3 and

Table 2. In the model with depressive symptoms as the dependent variable (

Figure 2), prosociality was positively related to peer preference (a

1 = 0.45,

p < 0.001), which, in turn, was negatively related to depressive symptoms (b

1 = −0.07,

p = 0.025). The indirect effect of prosociality on depressive symptoms through peer preference was significant (a

1b

1 = −0.03, 95% CI [−0.06, −0.01]), thus demonstrating that peer preference served as a mediator. In addition, prosociality was positively related to self-perceived social competence (a

2 = 0.16,

p < 0.001), which, in turn, was negatively related to depressive symptoms (b

2 = −0.56,

p < 0.001). The indirect effect of prosociality on depressive symptoms through self-perceived social competence was significant (a

2b

2 = −0.09, 95% CI [−0.13, −0.05]), thus demonstrating that self-perceived social competence served as a mediator. Moreover, peer preference was positively related to self-perceived social competence (d

1 = 0.21,

p < 0.001). The serial mediating effect of prosociality on depressive symptoms through peer preference and self-perceived social competence was also significant (a

1d

1b

2 = −0.05, 95% CI [−0.07, −0.04]).

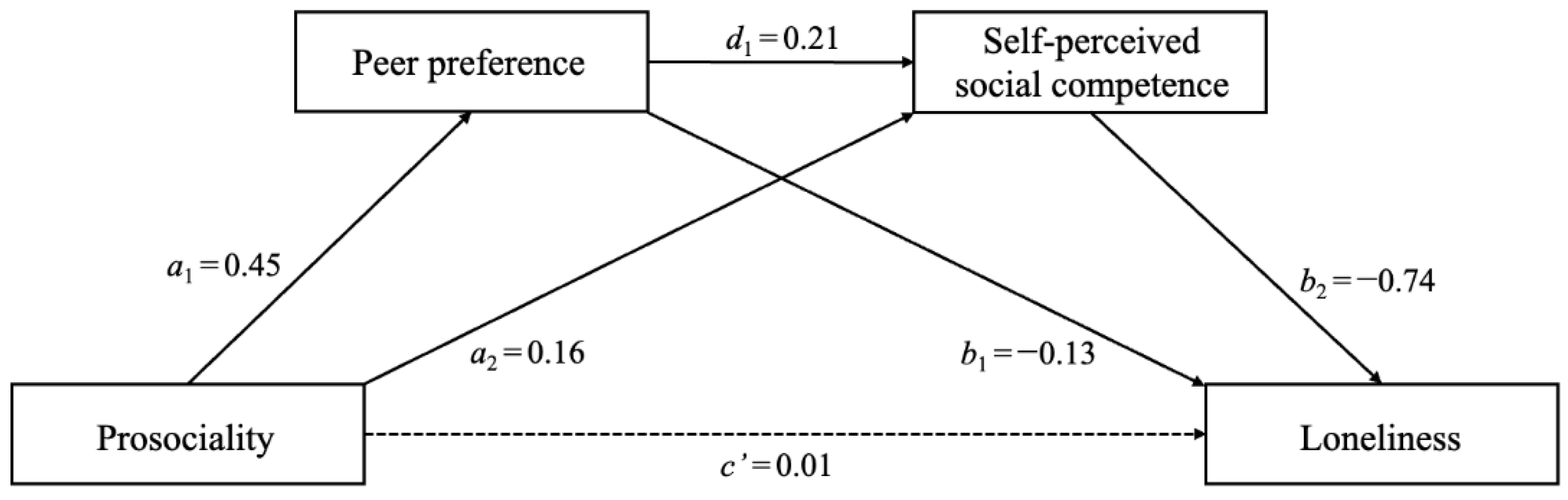

In the model with loneliness as the dependent variable (

Figure 3), prosociality was positively related to peer preference (a

1 = 0.45,

p < 0.001), which, in turn, was negatively related to loneliness (b

1 = −0.13,

p < 0.001). The indirect effect of prosociality on loneliness through peer preference was significant (a

1b

1 = −0.06, 95% CI [−0.09, −0.04]), thus demonstrating that peer preference served as a mediator. In addition, prosociality was positively related to self-perceived social competence (a

2 = 0.16,

p < 0.001), which, in turn, was negatively related to loneliness (b

2 = −0.74,

p < 0.001). The indirect effect of prosociality on loneliness through self-perceived social competence was significant (a

2b

2 = −0.12, 95% CI [−0.17, −0.07]), thus demonstrating that self-perceived social competence served as a mediator. Moreover, the serial mediating effect of prosociality on loneliness through peer preference and self-perceived social competence was also significant (a

1d

1b

2 = −0.07, 95% CI [−0.09, −0.05]).

4. Discussion

Previous research has shown that prosociality is critical to child and adolescent social functioning [

2]. Children and adolescents with high levels of prosociality often report lower levels of internalizing symptoms, such as depressive and anxiety symptoms, and loneliness, which suggest that prosociality may serve as a protective factor for developing psychological maladjustment [

3,

4,

5]. However, the mechanisms that might help to explain the associations are not well understood. Accordingly, in the present study, we evaluated a complex conceptual model to examine the mediating effects of peer preference and self-perceived social competence on the associations between prosociality and psychological maladjustment. Multiple mediation analyses indicate that the association between prosociality and psychological maladjustment is mediated by both peer preference and self-perceived social competence. Additionally, a serial indirect pathway was observed when controlling for grade and gender.

4.1. The Mediation Role of Peer Preference and Self-Perceived Social Competence

In this study, it was found that prosocial behavior may prevent children and adolescents from psychological symptoms. According to the results of this study, peer preference mediates the relations between prosociality and psychological maladjustment. It is consistent with previous findings that showed the reciprocal association between prosocial behaviors and peer relationships, namely positive social behaviors promote good peer relationships and vice-versa [

44,

45]. Moving beyond that, peer difficulties, such as low social preference, have been shown to affect children's symptoms of depression from kindergarten [

46]. This effect may even last through adolescence [

47]. The link from prosocial behavior to peer interaction and then to psychological adjustment can be explained by the contextual-developmental perspective [

7]. Cultural values offer a framework for social assessments of children's behaviors, which can subsequently shape their developmental trajectories. In Chinese culture, where promoting interpersonal harmony is emphasized, prosocial behavior is encouraged and esteemed as a moral virtue that facilitates the smooth functioning of the peer network [

14]. Consistently, studies had reported that children with prosocial behaviors (such as politeness, helping others, leadership, etc.) generally had supportive peers and were favored by teachers. [

48,

49]. These positive interaction experiences enable them to meet their own social, psychological, and instrumental needs, and their emotional experience of depression and loneliness decreases accordingly. The present study found that adolescents who had higher scores on prosociality were more preferred and well-liked by their peers, which in turn reduced their depressive symptoms and loneliness. This finding provided new evidence for the contextual-developmental perspective.

In the present study, self-perceived social competence is another potential mediator that can explain the relations between prosociality and psychological maladjustment. Self-perceived social competence can be defined as the degree to which people’s judgments of how they are seen by others are correct [

50]. Children’s social behaviors have long been linked to their self-concept, and studies have found a significant correlation between self-concept and cooperative behavior [

17,

18,

51]. Prosocial behavior enables individuals to retain their sense of self, especially, their social selves, in a more favorable light, because they may feel valued and needed by others, bolsters feelings about the social self eventually [

19]. On the other hand, according to sociometer theory, perceptions of peer approval are regarded as essential for assessments of one’s worth as a person. Further, adolescents start to evaluate themselves on a variety of life domains, including their social roles and integration in peer groups [

24,

52,

53]. In consistent with prior findings, this study provided evidence that prosocial behavior can be used as a protective factor to allow individuals to experience less psychological maladjustment. The high level of prosociality is positively connected with self-perceived social competence, which mirrored the results that prosociality is linked to higher levels of general self-worth and social worth [

19,

20]. and the positive self-perceived social competence, in turn, may protect children from developing psychological problems [

23].

4.2. The Serial Multiple Mediation Model

This study further found that peer preference and self-perceived social competence play a serial mediation role between prosociality and psychological maladjustment. It provides evidence of a positive connection between peer preference and self-perceived social competence, which is partly consistent with previous research [

48,

49]. Humanism believes that loneliness is an individual’s subjective feeling about the number of friends and quality of friendship as well as the evaluations of their basic social skills. Children feel lonely when the quantity and quality of their social networks are lower than expected [

54]. Hymel and colleagues have explained the relations between loneliness and social status from the perspective of social cognition. They believe that children's loneliness and their actual social status among peers is the individual’s perceived level of interpersonal relationship mediated by social cognition [

55]. Dodge devised a model of social information processing, which stresses the cognitive steps in evaluating social situations. Those children and adolescents who have defects or deviations in social information processing will encounter difficulties in interacting with their peers and be negatively evaluated by their peers, and vice versa [

56]. Adolescents with higher levels of prosociality are likely to possess relatively strong social skills and receive positive feedback from their peers, as shown in higher peer preference (i.e., likeability), and they may integrate the positive feedback from peers into their sense of social self and they may perceive that they are socially accepted and competent. This, in turn, could mitigate the risk of experiencing depression and loneliness.

4.3. Implications, Limitations, and Future Directions

This study examined the impact of prosocial behavior on child and adolescent psychological maladjustment in Chinese culture. The mechanisms of these relations may inform prevention and early intervention programs for internalizing problems through the strength of prosociality among children and adolescents. Additionally, subjective evaluation (self-perceived social competence) of peer interaction and objective assessment from peers (nominations from their social group) are important characteristics of peer relationships to include in any study investigating relations between peers in adolescence [

57]. Therefore, the current study assessed peer relationships from both subjective and objective perspectives when examining their links between prosocial behavior and psychological symptoms, which extends the field of the effect of peer interaction on psychological maladjustment.

Despite the contribution of this research to the extant literature, some limitations should be noted when interpreting the findings. First, a cross-sectional study reduces our ability to establish causal links and the direction of effects between the constructs under investigation. Relatedly, there may be biases when mediation effects are examined using cross-sectional data [

58]. To address these limitations, it is recommended that future research adopt a three-wave longitudinal design which will allow for the testing of mediation effects, as well as the examination of directional and transactional processes over time [

59]. Second, data were derived from self-reports, and the social desirability effect may affect the accuracy of the results. In the future, prosocial behavior and psychological maladjustment together with their associations can be studied through interviews and other methods. Third, children and adolescents are in an important stage of individual development, and their prosocial behavior is easily affected by other factors in daily life, such as their development of the theory of mind and popularity goals [

60,

61]. Therefore, in the future, these variables could be included as an endorsement of boundary conditions in this model to further explore the impact of other factors on prosocial behavior and the psychological mechanism.

5. Conclusion

Our study tested a serial mediation model of peer preference and self-perceived social competence as mediators between prosocial behavior and psychological maladjustment among Chinese children and adolescents. The results suggested that high levels of prosociality had a positive effect on peer preference, which improve the levels of self-perceived social competence, and thus less experience of psychological maladjustment among children and adolescents in Chinese culture. These findings provided implications for future intervention programs to focus on improving peer preference and self-perceived social competence among children and adolescents with low prosociality to reduce their psychological maladjustment.

Funding

This research was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (32000756).

References

- Caprara, G.V.; Alessandri, G.; Eisenberg, N. Prosociality: The contribution of traits, values, and self-efficacy beliefs. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2012, 102, 1289–1303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eisenberg, N.; Eggum-Wilkens, N. D.; Spinrad, T. L. The development of prosocial behavior, In The Oxford H of prosocial behavior.; D. A. Schroeder, & W. G. Graziano, Ed.; Oxford University Press: USA, 2015; pp. 114–136. [Google Scholar]

- Jin, G.; Fu, R.; Li, D.; Chen, X.; Liu, J. Longitudinal Associations Between Prosociality and Depressive Symptoms in Chinese Children: The Mediating Role of Peer Preference. J. Youth Adolesc. 2021, 51, 956–966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Padilla-Walker, L.M.; Millett, M.A.; Memmott-Elison, M.K. Can helping others strengthen teens? Character strengths as mediators between prosocial behavior and adolescents’ internalizing symptoms. J. Adolesc. 2020, 79, 70–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Woodhouse, S.S.; Dykas, M.J.; Cassidy, J. Loneliness and Peer Relations in Adolescence. Soc. Dev. 2011, 21, 273–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Memmott-Elison, M. K.; Holmgren, H. G.; Padilla-Walker, L. M.; Hawkins, A. J. Associations between prosocial behavior, externalizing behaviors, and internalizing symptoms during adolescence: A meta-analysis. J. Adolesc. 2020, 80, 98–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, X. Culture, peer interaction, and socioemotional development. Child. Dev. Perspect. 2012, 6, 27–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spilt, J. L.; van Lier, P. A. C.; Leflot, G. , Onghena, P. ; Colpin, H. Children's social self-concept and internalizing problems: The influence of peers and teachers. Child Dev. 2014, 85, 1248–1256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Pomerantz, E.M.; Qin, L.; Logis, H.; Ryan, A.M.; Wang, M. Characteristics of likability, perceived popularity, and admiration in the early adolescent peer system in the United States and China. Dev. Psychol. 2018, 54, 1568–1581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisenberg, N.; Eggum, N. D. Empathic responding: Sympathy and personal distress. In The social neuroscience of empathy.; J. Decety & W. Ickes Eds.; Boston Review, UK, 2009; pp. 71–83.

- Memmott-Elison, M.K.; Toseeb, U. Prosocial behavior and psychopathology: An 11-year longitudinal study of inter- and intraindividual reciprocal relations across childhood and adolescence. Dev. Psychopathol. 2022, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, A.N.; Carlo, G.; Schwartz, S.J.; Unger, J.B.; Zamboanga, B.L.; Lorenzo-Blanco, E.I.; Cano, M. .; Baezconde-Garbanati, L.; Oshri, A.; Streit, C.; et al. The Longitudinal Associations Between Discrimination, Depressive Symptoms, and Prosocial Behaviors in U.S. Latino/a Recent Immigrant Adolescents. J. Youth Adolesc. 2015, 45, 457–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.; Li, X.; Huebner, E.S.; Tian, L. Parent–child cohesion, loneliness, and prosocial behavior: Longitudinal relations in children. J. Soc. Pers. Relationships 2022, 39, 2939–2963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; French, D. C. Children's social competence in cultural context. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2008, 59, 591–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Y.; Chen, L.; Zhang, L.; Ji, L.; Zhang, W. Developmental changes in associations between depressive symptoms and peer relationships: a four-year follow-up of Chinese adolescents. J. Youth Adolesc. 2020, 49, 1913–1927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harter, S.; Pike, R. The pictorial scale of Perceived Competence and Social Acceptance for Young Children. Child Dev. 1984, 55, 1969–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boivin, M.; Hymel, S. Peer experiences and social self-perceptions: A sequential model. Dev Psychol. 1997, 33, 135–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hymel, S.; Bowker, A.; Woody, E. Aggressive versus withdrawn unpopular children: Variations in peer and self-perceptions in multiple domains. Child Dev. 1993, 64, 879–896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grant, A.M.; Gino, F. A little thanks goes a long way: Explaining why gratitude expressions motivate prosocial behavior. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2010, 98, 946–955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, X.; Padilla-Walker, L. M.; Brown, M. N. Longitudinal relations between adolescents' self-esteem and prosocial behavior toward strangers, friends and family. J Youth Adolesc. 2017, 57, 90–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobs, R.H.; Reinecke, M.A.; Gollan, J.K.; Kane, P. Empirical evidence of cognitive vulnerability for depression among children and adolescents: A cognitive science and developmental perspective. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2008, 28, 759–782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beck, A. T. Cognitive models of depression. J Cong Psychother. 1987, 1, 5–37. [Google Scholar]

- Cole, D. A. Relation of social and academic competence to depressive symptoms in childhood. J Abnorm Psychol. 1990, 99, 422–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Troop-Gordon, W.; Ladd, G.W. Trajectories of Peer Victimization and Perceptions of the Self and Schoolmates: Precursors to Internalizing and Externalizing Problems. Child Dev. 2005, 76, 1072–1091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobs, R.H.; Reinecke, M.A.; Gollan, J.K.; Kane, P. Empirical evidence of cognitive vulnerability for depression among children and adolescents: A cognitive science and developmental perspective. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2008, 28, 759–782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spilt, J. L.; van Lier, P. A. C.; Leflot, G.; Onghena, P.; Colpin, H. Children's social self-concept and internalizing problems: The influence of peers and teachers. Child Dev. 2014, 85, 1248–1256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, X.; Rubin, K. H.; Sun, Y. Social reputation and peer relationships in Chinese and Canadian children: A cross-cultural study. Child Dev. 1992, 63, 1336–1343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masten, A. S.; Morison, P.; Pellegrini, D. S. A revised class play method of peer assessment. Dev Psychol. 1985, 21, 523–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Li, D.; Li, Z.; Li, B.; Liu, M. Sociable and prosocial dimensions of social competence in Chinese children: Common and unique contributions to social, academic, and psychological adjustment. Dev Psychol. 2000, 36, 302–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kovacs, M. The Children’s Depression Inventory (CDI) manual, 1st ed.; Multi-Health Systems: Germany, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Ding, X.; Ooi, L.L.; Coplan, R.J.; Zhang, W.; Yao, W. Longitudinal Relations between Rejection Sensitivity and Adjustment in Chinese Children: Moderating Effect of Emotion Regulation. J. Genet. Psychol. 2021, 182, 422–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, P.; Coplan, R.J.; Zhang, Y.; Ding, X.; Zhu, Z. Assessment and implications of aloneliness in Chinese children and early adolescents. J. Appl. Dev. Psychol. 2023, 85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asher, S.R.; Hymel, S.; Renshaw, P.D. Loneliness in Children. Child Dev. 1984, 55, 1456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, X.; Chen, X.; Fu, R.; Li, D.; Liu, J. Relations of Shyness and Unsociability with Adjustment in Migrant and Non-migrant Children in Urban China. J. Abnorm. Child Psychol. 2019, 48, 289–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ding, X.; Zhang, W.; Ooi, L.L.; Coplan, R.J.; Zhang, S.; Dong, Q. Longitudinal relations between social avoidance, academic achievement, and adjustment in Chinese children. J. Appl. Dev. Psychol. 2022, 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coie, J.; Terry, R.; Lenox, K.; Lochman, J.; Hyman, C. Childhood peer rejection and aggression as predictors of stable patterns of adolescent disorder. Dev. Psychopathol. 1995, 7, 697–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, X.; Chen, X.; Fu, R.; Li, D.; Liu, J. Relations of Shyness and Unsociability with Adjustment in Migrant and Non-migrant Children in Urban China. J. Abnorm. Child Psychol. 2019, 48, 289–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, X.; Fu, R.; Ooi, L.L.; Coplan, R.J.; Zheng, Q.; Deng, X. Relations between different components of rejection sensitivity and adjustment in Chinese children. J. Appl. Dev. Psychol. 2020, 67, 101119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, X.; Zhang, W.; Ooi, L.L.; Coplan, R.J.; Zhu, X.; Sang, B. Relations between social withdrawal subtypes and socio-emotional adjustment among Chinese children and early adolescents. J. Res. Adolesc. 2023, 33, 774–785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harter, S. Manual for the Self-Perception Profile for Children.; University of Denver: Colorado, UK, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Ding, X.; Liu, J.; Li, D.; Sang, B. Psychometric properties of Chinese version of Harter’s Self-Perception Profile for Children. Chin. J. Clin. Psychol. 2014, 22, 251–255. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, J.; Coplan, R. J.; Chen, X.; Li, D.; Ding, X.; Zhou, Y. Unsociability and Shyness in Chinese Children: Concurrent and Predictive Relations with Indices of Adjustment: Unsociability in China. Soc. Dev. 2014, 23, 119–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, A. F. Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach.; Guilford publications: NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Layous, K.; Nelson, S.K.; Oberle, E.; Schonert-Reichl, K.A.; Lyubomirsky, S. Kindness Counts: Prompting Prosocial Behavior in Preadolescents Boosts Peer Acceptance and Well-Being. PLOS ONE 2012, 7, e51380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aikins, J. W.; Litwack, S. D. Popularity in the peer system. In Prosocial skills, social competence, and popularity.; A. H. N., Cillessen., D., Schwartz., L., Mayeux., Eds.; The Guilford Press: NY, USA, 2011; pp. 140–162. [Google Scholar]

- Gooren, E.M.J.C.; van Lier, P.A.C.; Stegge, H.; Terwogt, M.M.; Koot, H.M. The Development of Conduct Problems and Depressive Symptoms in Early Elementary School Children: The Role of Peer Rejection. J. Clin. Child Adolesc. Psychol. 2011, 40, 245–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Will, G.-J.; van Lier, P.A.C.; Crone, E.A.; Güroğlu, B. Chronic Childhood Peer Rejection is Associated with Heightened Neural Responses to Social Exclusion During Adolescence. J. Abnorm. Child Psychol. 2015, 44, 43–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Sun, H. ; The Relationship of Children’s Loneliness with Peer Relationship, Social Behavior and Self-perceived Social Competence. Psychol Sci. 2007, 01, 84–88+51. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, Z.; Zhao, D.; Chen, J.; Jiang, J.; Rachel, H. Loneliness as a Function of Sociometric Status and Self-Perceived Social Competence in Middle Childhood. Dev. Psychopathol. 2003, 04, 70–74. [Google Scholar]

- Kenny, D. A. Interpersonal perception: A social relations analysis.; Guilford Press: NY, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Cauley, K.; Tyler, B. The relationship of self-concept to prosocial behavior in children. Early Child. Res. Q. 1989, 4, 51–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harter, S. The construction of the self.; Guilford Press: NY, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Fend, H. Eltern und Freunde. Soziale Entwicklung im Jugendalter [Parents and friends. Social development in adolescence]. Hans Huber 1998.

- Bo, L.; Chen, H. Personality psychology. China Light Industry Press: BeiJing, CN, 2004.

- Zou, H. The Developmental Function of Peer Relationship and Its Influencing Factors. Dev Psychol. 1998 14, 40–46.

- Parke, R. D.; Clarke-Stewart, A. A. A World of Their Own. In Social development, 2nd ed.; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Andrea, E.; Michelle, A.; Helmut, A. Subjective and Objective Peer Approval Evaluations and Self-Esteem Development: A Test of Reciprocal, Prospective, and Long-Term Effects. Dev Psychol. 2016, 52, 1563–1577. [Google Scholar]

- Maxwell, S.E.; Cole, D.A.; Mitchell, M.A. Bias in Cross-Sectional Analyses of Longitudinal Mediation: Partial and Complete Mediation Under an Autoregressive Model. Multivar. Behav. Res. 2011, 46, 816–841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacKinnon, D.P.; Luecken, L.J. How and for whom? Mediation and moderation in health psychology. Multivariate Behav Res. 2008, 27, S99–S100. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, X.; Auyeung, B.; Pan, N.; Lin, L.-Z.; Chen, Q.; Chen, J.-J.; Liu, S.-Y.; Dai, M.-X.; Gong, J.-H.; Li, X.-H.; et al. Empathy, Theory of Mind, and Prosocial Behaviors in Autistic Children. Front. Psychiatry 2022, 13, 844578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lansu, T.A. How popularity goal and popularity status are related to observed and peer-nominated aggressive and prosocial behaviors in elementary school students. J. Exp. Child Psychol. 2023, 227, 105590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).