Submitted:

10 May 2023

Posted:

12 May 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

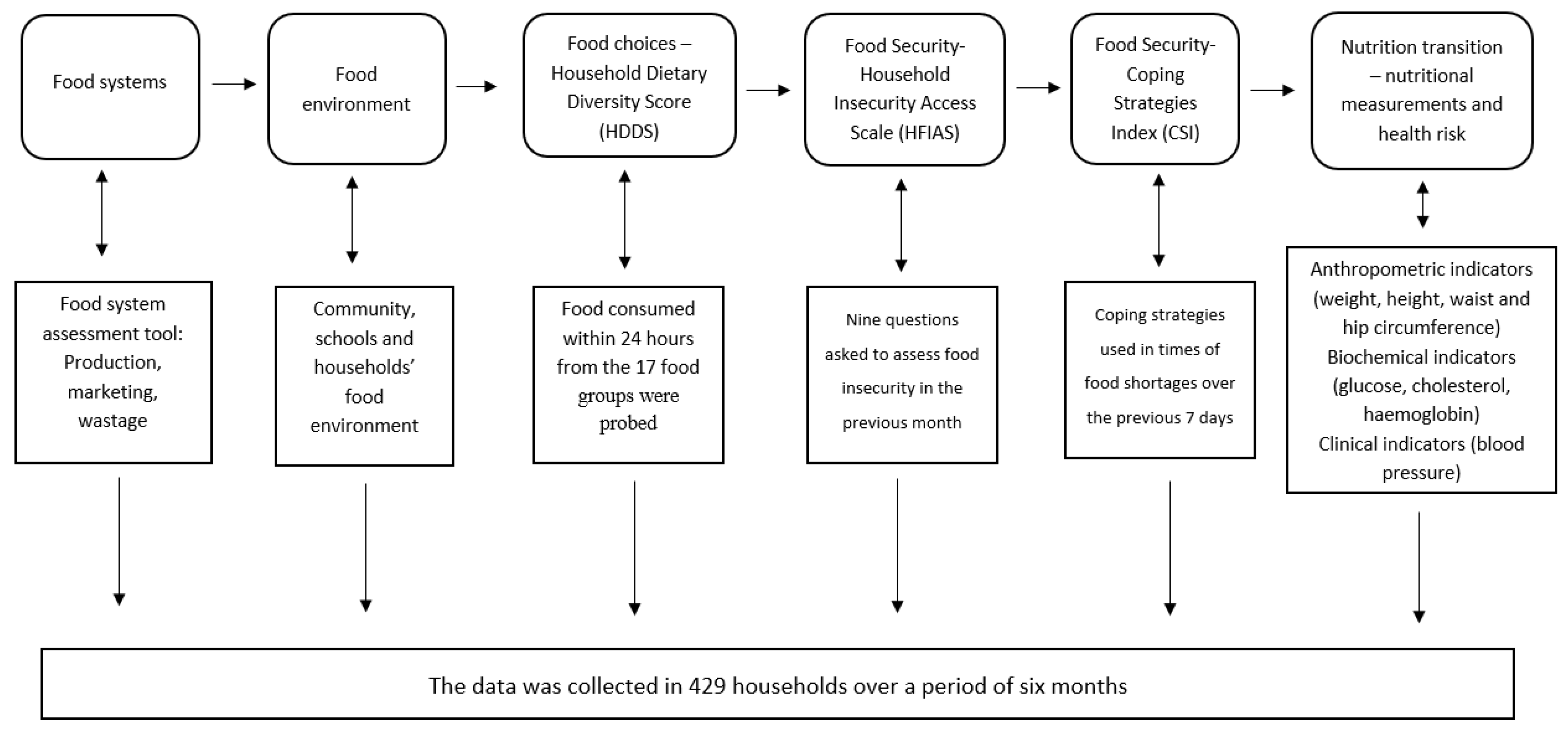

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Setting

2.2. Target Population, Sample Size Calculation and Sampling Technique

2.3. Data Collection Tool and Procedure

2.4. Ethical Clearance

2.5. Data Analysis

2. Results

2.1. Socio-Demographic Information and Biophysical Environment

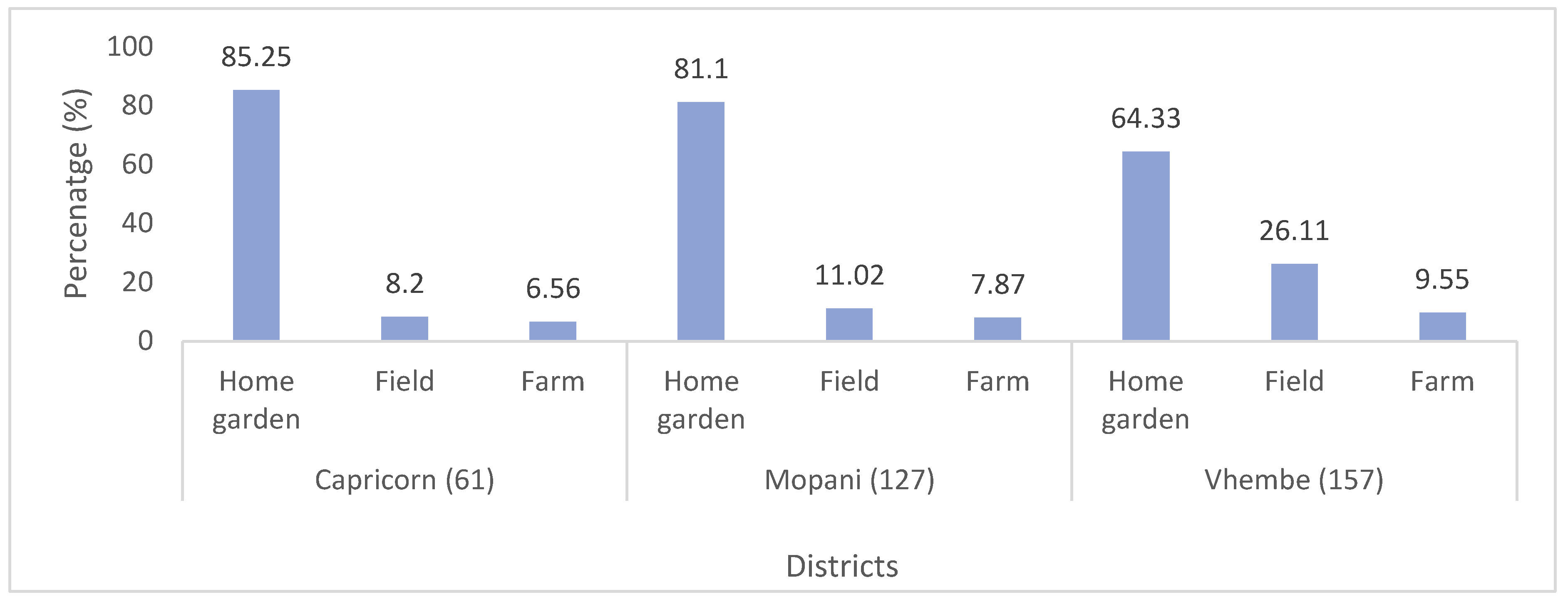

2.2. Food Systems Assessment

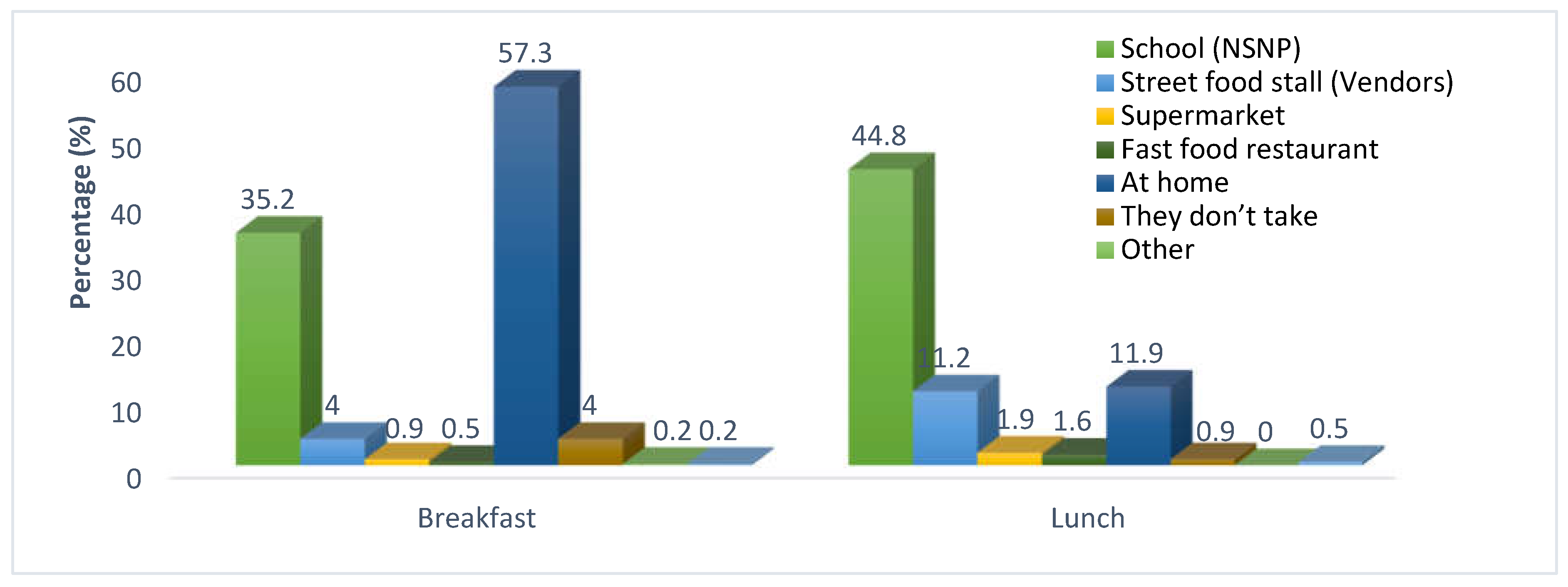

2.3. Food Environment Assessment

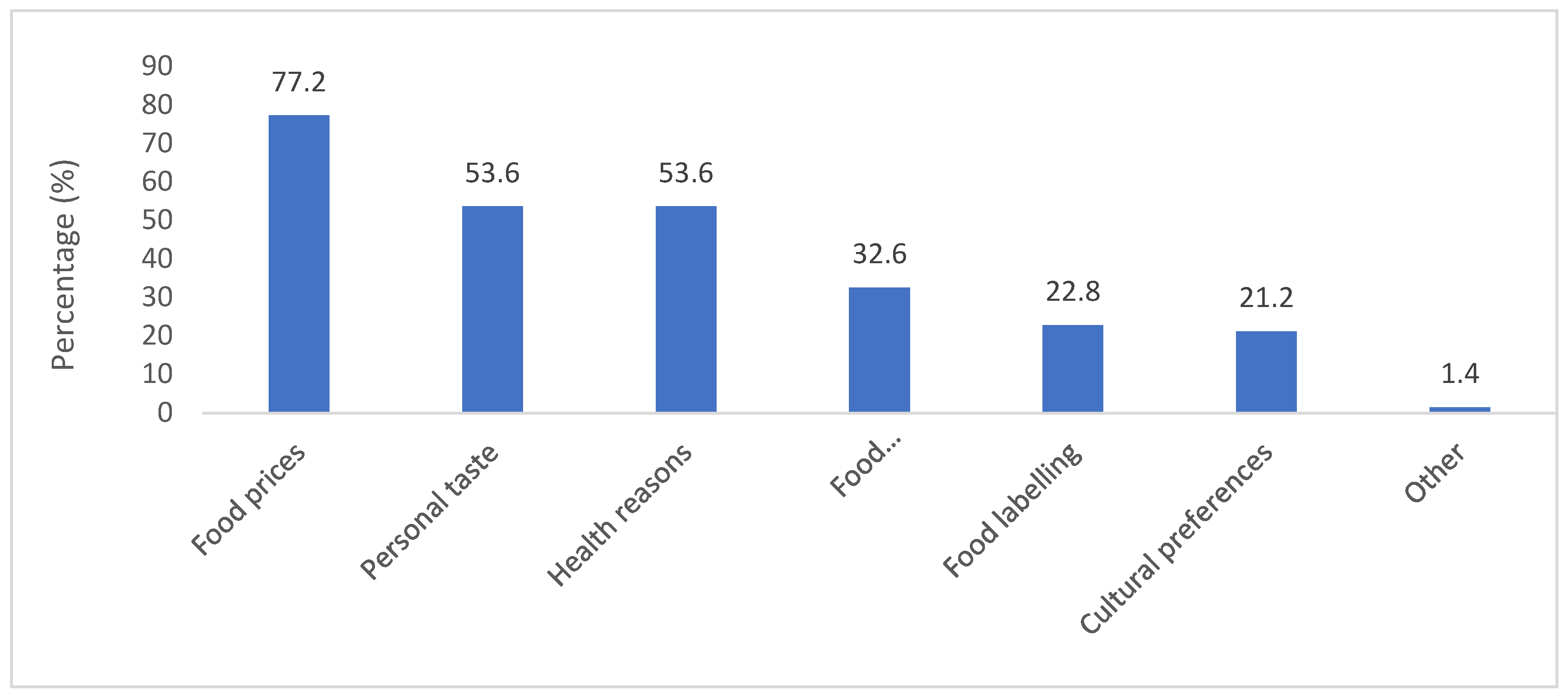

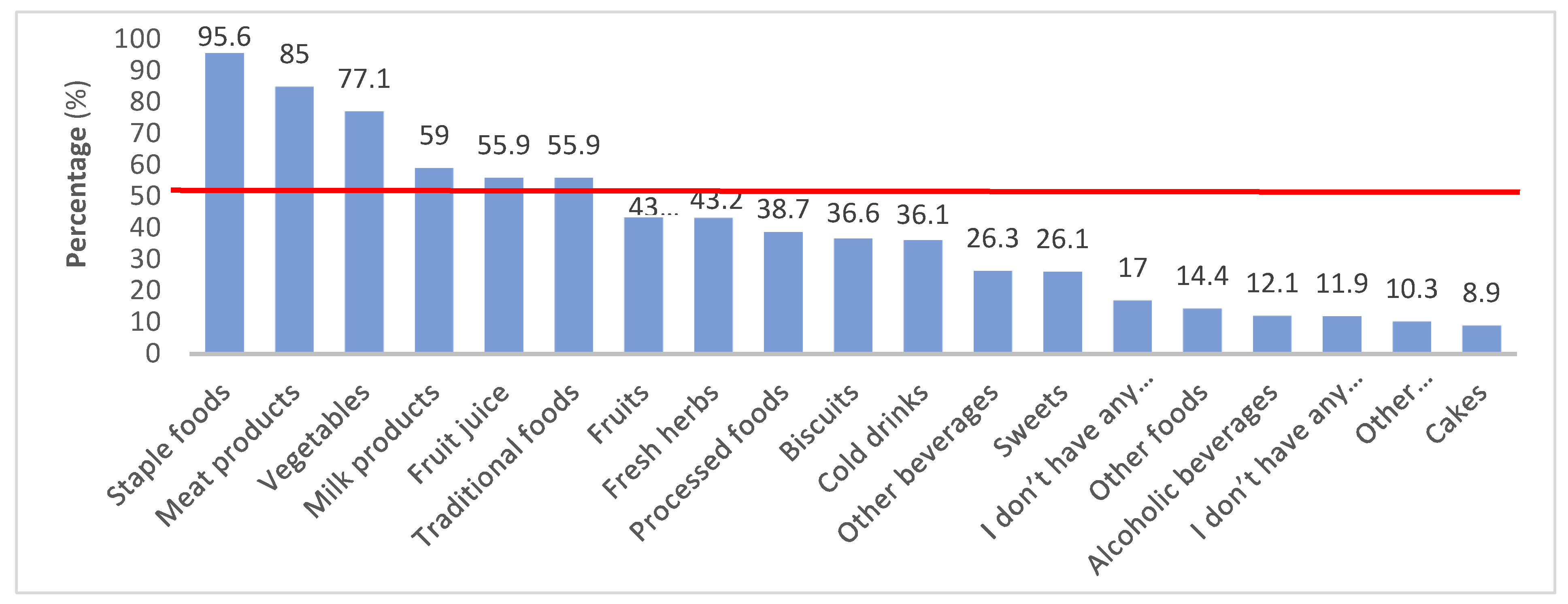

2.4. Food Choices

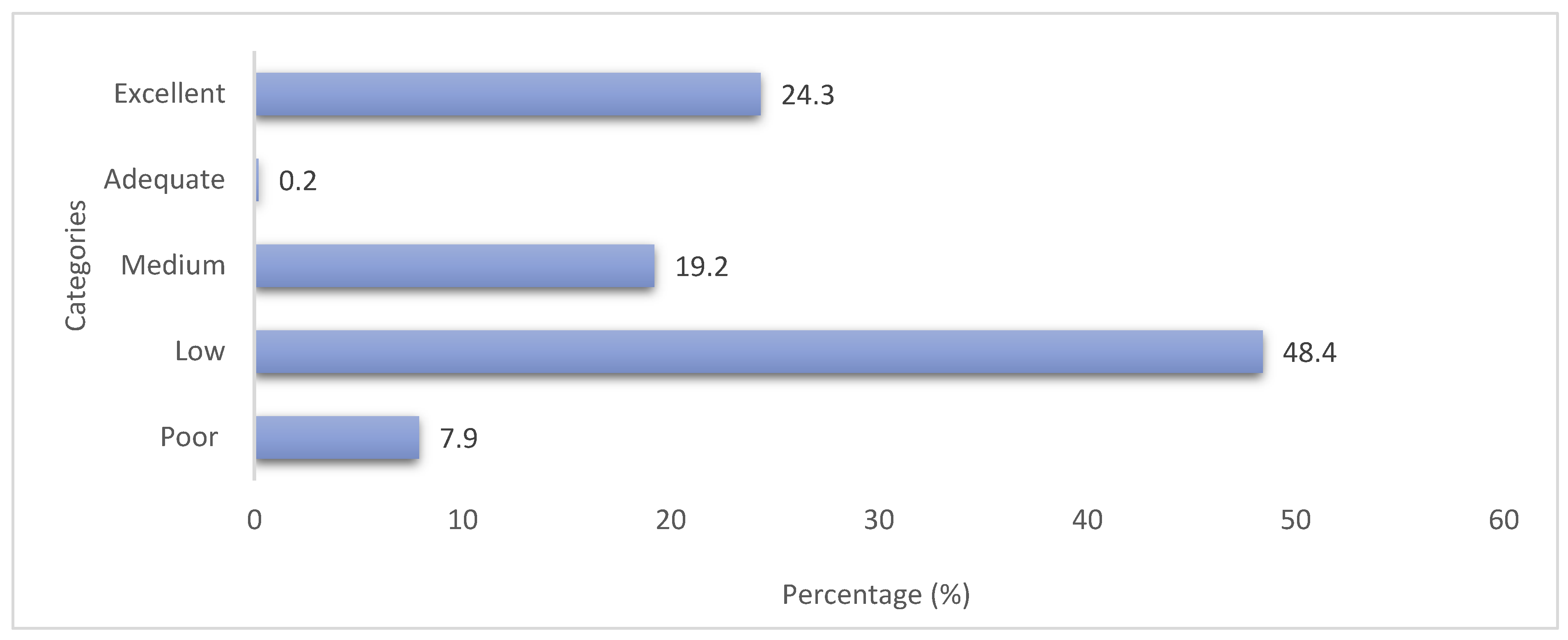

2.5. Household Food Security Status

| Food security characteristics | % |

|---|---|

|

HFIAS domains Anxiety and uncertainty over food Insufficient food quality Insufficient food intake |

45.2 40.2 46.0 |

|

HFIAS conditions Worrying about food intake Not able to eat preferred food Limited variety of food Eating unwanted foods Eating smaller meals Eating fewer meals No food in the house Sleeping hungry The whole day and night without food |

43.7 40.6 39.5 38.9 33.1 26.8 15.6 8.2 6.5 |

|

HFIAS categories Food secure Mildly food insecure Moderately food insecure Severe food insecurity |

46.0 23.8 26.3 4.0 |

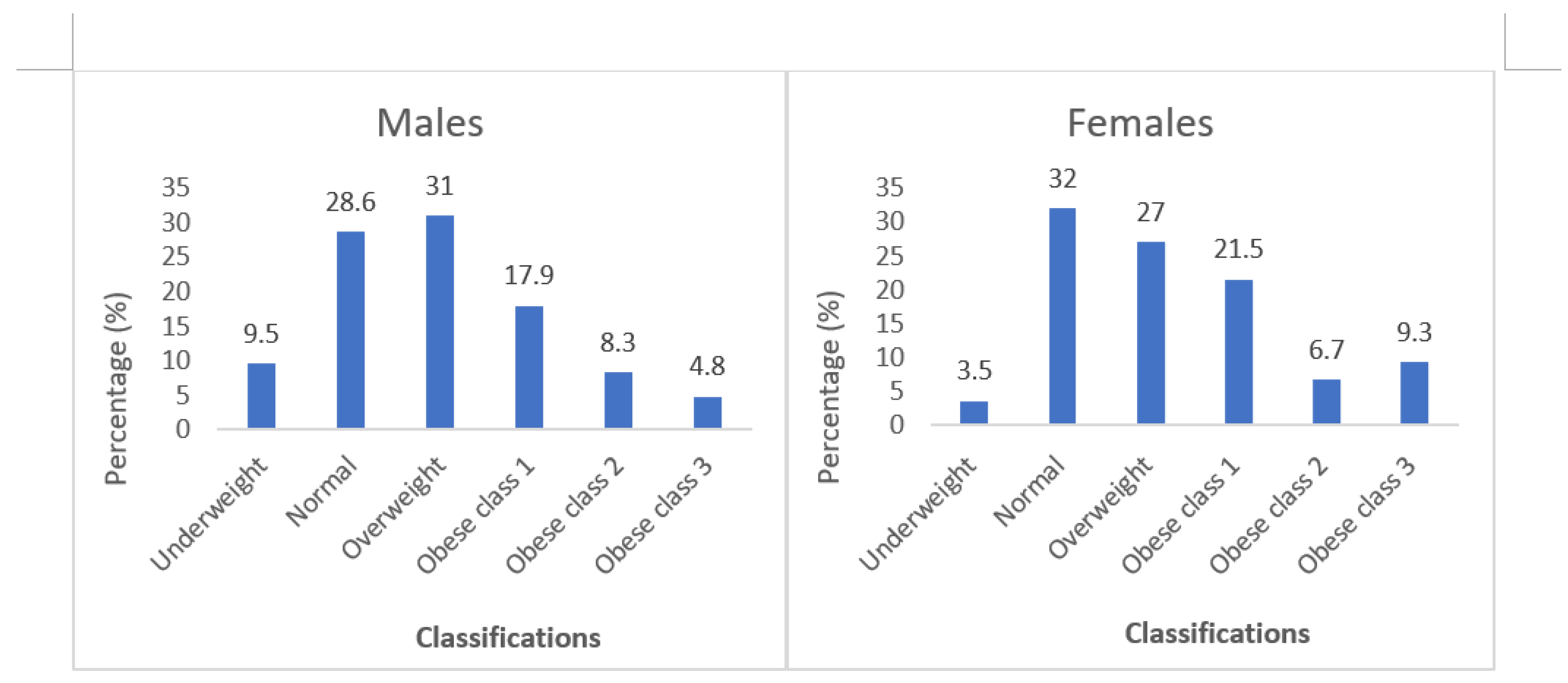

2.6. Nutritional Status and Health Risk

2.6.1. Anthropometric Indicators of Household Informants

2.6.2. Biochemical Indicators of Households’ Informants

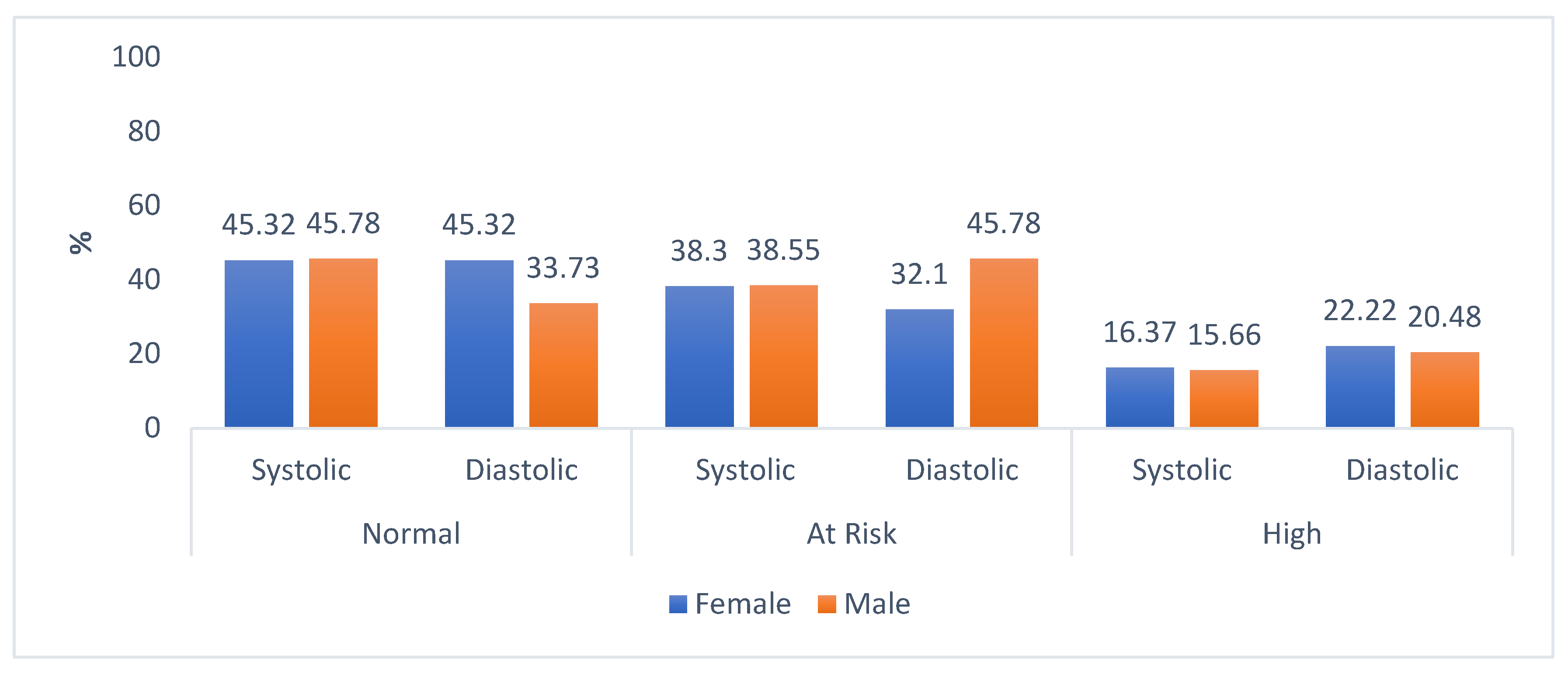

2.6.3. Clinical Indicators of Households’ Informants

3. Discussion

4. Conclusion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflict of interest

References

- World Wildlife Fund-WWF. Food: Agri-food Systems: Facts and Futures. Available online: https://dtnac4dfluyw8.cloudfront.net/downloads/wwf_food_report_facts_and_futures_2019.pdf?27341/agri-food-systems-facts-and-futures (accessed on 17 September 2019).

- Downs, S.M.; Ahmed, S.; Fanzo, J.; Herforth, A. Food environment typology: Advancing an expanded definition, framework, and methodological approach for improved characterization of wild, cultivated, and built food environments toward sustainable diets. Foods 2020, 9, 532. [CrossRef]

- Girard, A.W.; Little, P.; Yount, K.; Dominguez-Salas, P.; Kinabo, J.; Mwanri, A. Understanding the Drivers of Diet Change and Food Choice Among Tanzanian Pastoralists to Inform Policy and Practice; Drivers of Food Choice Research Brief, University of South Carolina: South Carolina, USA, 2020.

- Nyiwul, L. Climate change adaptation and inequality in Africa: Case of water, energy and food insecurity. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 278, 1-11. [CrossRef]

- Food and Agriculture Organisation-FAO. The state of food and agriculture: food systems for better nutrition. Available online: www.fao.org/docrep/018/i3300e/i3300e00.htm (accessed on 26 June 2021).

- Turner, C.; Kadiyala, S.; Aggarwal, A.; Coates, J.; Drewnowski, A.; Hawkes, C.; Walls H. Concepts and methods for food environment research in low- and middle-income countries; Agriculture, Nutrition and Health Academy Food Environments Working Group (ANH-FEWG), Innovative Methods and Metrics for Agriculture and Nutrition Actions (IMMANA) programme, London, United Kingdom, 2017.

- Swinburn, B.; Vandevijvere, S.; Kraak, V.; Sacks, G.; Snowdon, W.; Hawkes, C.; Walker, C. Monitoring and benchmarking government policies and actions to improve the healthiness of food environments: a proposed Government Healthy Food Environment Policy Index. Obes. Rev. 2013, 14, 24-37. [CrossRef]

- Herforth, A.; Ahmed, S. The food environment, its effects on dietary consumption, and potential for measurement within agriculture-nutrition interventions. Food Secur. 2015, 7, 505-520. [CrossRef]

- Food and Agriculture Organisation - FAO. Influencing food environments for healthy diets. Available online: www.fao.org/3/a-i6484e.pdf (accessed on 13 May 2020).

- Global Panel on Agriculture and Food Systems for Nutrition – GLOPAN. Food systems and diets: Facing the challenges of the 21st century. Available online: www.glopan.org/sites/default/files/ForesightReport.pdf (accessed on 13 May 2019).

- Popkin, B.M.; Adair, L.S.; Ng, S.W. NOW AND THEN: The Global Nutrition Transition: The Pandemic of Obesity in Developing Countries. Nutr. Rev. 2020, 70, 3-21. [CrossRef]

- Willett, W.; Rockström, J.; Loken, B.; Springmann, M.; Lang, T.; Vermeulen, S.; Garnett, T.; Tilman, D.; DeClerck, F.; Wood, A.; et al. Food in the Anthropocene: the EAT-Lancet Commission on healthy diets from sustainable food systems. The Lancet 2019, 393(10170), 447-492. [CrossRef]

- Pillay-van Wyk, V.; Msemburi, W.; Laubscher, R.; Dorrington, R.E.; Groenewald, P.; Glass, T.; Nojilana, B.; Joubert J.D.; Matzopoulos, R.; Prinsloo, M. Mortality trends and differentials in South Africa from 1997 to 2012: second National Burden of Disease Study. Lancet Global Health 2016, 4(9), e642-e653. [CrossRef]

- De Cock, N.; D’Haese, M.; Vink, N.; van Rooyen, CJ.; Staelens, L.; Schönfeldt, H.C.; D’Haese, L. Food security in rural areas of Limpopo province, South Africa. Food security 2013, 5(2), 269-282. [CrossRef]

- Shisana, O., Labadarios, D., Rehle, T., Simbayi, L., Zuma, K., Dhansay, A., Reddy, P., Parker, W., Hoosain, E., Naidoo, P.; et al. South African National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (SANHANES-1). Available online: http://repository.hsrc.ac.za/bitstream/handle/20.500.11910/2864/7844.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y (accessed on 23 October 2019).

- Chase, L.; Grubinger, V.P. Food, Farms and Community; Exploring Food Systems, University of New Hampshire: Durham, England, 2014.

- Harris, J.; Chisanga, B.; Drimmie, S.; Kennedy, G. Nutrition transition in Zambia: Changing food supply, food prices, household consumption, diet and nutrition outcomes. Food Sec. 2019, 11, 371-387. [CrossRef]

- Holdsworth, M.; Landais, E. Urban food environments in Africa: Implications for policy and research. PNS 2019, 1-13. [CrossRef]

- Constantinides, S.V.; Turner, C.; Frongillo, E.A.; Bhandari. S.; Reyes, L.I.; Blake, C.E. Using a global food environment framework to understand relationships with food choice in diverse low- and middle-income countries. Glob. Food Sec. 2021, 29, 100511. [CrossRef]

- Statistics South Africa - Stats SA. 2020 Mid-year population estimates. Available online: http://www.statssa.gov.za/publications/P0302/P03022020.pdf (accessed on 2 June 2021).

- Green, S. H., & Glanz, K. Development of the Perceived Nutrition Environment Measures Survey. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2015, 49(1), 50-61.

- Saelens, B.E., Glanz, K., Sallis J.F., Frank L.D. Nutrition Environment Measures Study in Restaurants (NEMS-R): Development and evaluation. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2007, 32(4), 282-289.

- Glanz, K.; Sallis, J.F.; Saelens, B.E.; Frank, L.D. Nutrition Environment Measures Survey in Stores (NEMS-S): Development and evaluation. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2007, 32(4), 273-281.

- 20 July.

- Coates, J.; Swindale, A.; Bilinsky, P. Household Food Insecurity Access Scale (HFIAS) for Measurement of Household Food Access: Indicator Guide (v3). Washington DC. FHI 360/FANTA. Available online https://www.fantaproject.org/sites/default/files/resources/HFIAS_ENG_v3_Aug07.pdf (accessed on 16 July 2021).

- Food and Agriculture Organisation - FAO. “The Coping Strategies Index: A tool for rapid measurement of household food security and the impact of food aid programs in humanitarian emergencies: Field methods manual”. 2nd ed. Available online: www.fao.org/3/a-ae513e.pdf (accessed on 19 May 2019).

- Food and Agriculture Organisation - FAO. Guidelines for measuring household and individual dietary diversity. Available online: https://www.fao.org/3/i1983e/i1983e.pdf (accessed on 9 February 2022).

- Ninno, C.D.; Dorosh, P.A.; Smith, L.C. Public policy, market and household coping strategies in Bangladesh: Avoiding food security crisis following the 1998 floods. World development 2003, 31, 1221-1238. [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization - WHO. Non-communicable diseases global monitoring framework: Indicator definitions and specifications. Available online: https://www.who.int/nmh/ncd-tools/indicators/GMF_Indicator_Definitions_Version_NOV2014.pdf (accessed on 16 July 2019).

- World Health Organisation – WHO.; International Federation on Diabetes - IDF. Definition and diagnosis of diabetes mellitus and intermediate hyperglycaemia: report of a WHO/IDF Consultation. Available online: https://www.who.int/diabetes/publications/Definition%20and%20diagnosis%20of%20diabetes_new.pdf (accessed on 9 February 2022).

- The Heart and Stroke Foundation South Africa. Cholesterol. Available online: https://www.heartfoundation.co.za/cholesterol/ (accessed on 11 October 2021).

- World Health Organization - WHO. Haemoglobin concentrations for the diagnosis of anaemia and assessment of severity. Available online: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/85839 (accessed on 9 February 2022).

- American College of Cardiology. High Blood Pressure Guidelines. Available online: https://www.cardiosmart.org/news/2017/11/high-blood-pressure-guidelines-2017#:~:text=For%20example%2C%20blood%20pressure%20between,at%20130%2F80%20mm%20Hg (accessed on 9 February 2022).

- Statistics South Africa - Stats SA. General Household Survey. Available online: https://www.statssa.gov.za/publications/P0318/P03182018.pdf (accessed on 3 August 2021).

- Mkhawani, K.; Motadi, S.A.; Mabapa, N.S.; Mbhenyane, X.G.; Blaauw, R. Effects of rising food prices on household food security on female-headed households in Runnymede Village, Mopani District, South Africa. South Afr J Clin Nutr 2016, 29,69-74. Available online: http://www.sajcn.co.za/index.php/SAJCN/article/view/994 (accessed on 8 November 2019).

- Statistics South Africa - Stats SA. South Africa Demographic and Health Survey: Key indicator report. Available online: https://www.statssa.gov.za/publications/Report%2003-00-09/Report%2003-00092016.pdf (accessed on 6 October 2021).

- Mbhenyane, X.G.; Tambe, B.A.; Phooko-Rabodiba, D.A.; Nesamvuni, C.N. The relationship between employment status of the mother, household hunger and nutritional status of children in Sekhukhune district, Limpopo province. African J. Food, Agric. Nutr. Dev. 2020, 20, 15821-15836. [CrossRef]

- Taruvinga, A.; Muchenje, V.; Mushunje, A. Determinants of rural household dietary diversity: The case of Amatole and Nyandeni districts, South Africa. Int. J. Sustain. Dev. Plan. 2013, 2,2233-2247. Available online: https://isdsnet.com/ijds-v2n4-4.pdf (accessed on 1 July 2021).

- Cheteni, P. Youth Participation in Agriculture in the Nkonkobe District Municipality, South Africa. J Hum. Ecol. 2016, 55,207-213. Available at https://www.econstor.eu/bitstream/10419/162735/1/Youth%20Participation%20in%20Agriculture%20in%20the%20Nkonkobe%20District%20Municipality.pdf (accessed on 1 July 2021).

- Cheteni, P.; Khamfula, Y.; Mah, G. Exploring Food Security and Household Dietary Diversity in the Eastern Cape Province, South Africa. Sustainability 2020, 12,1851. [CrossRef]

- Ward, P.R.; Coveney, J.; Verity, F.; Carter, P.; Schilling, M. Cost and affordability of healthy food in rural South Australia. Rural Remote Health 2012, 12, 1938. [CrossRef]

- Pietermaritzburg Economic Justice & Dignity Group - PMBEJD. Household Affordability Index. Available online: https://pmbejd.org.za/wp-content/uploads/2023/01/January-2023-Household-Affordability-Index-PMBEJD_25012023.pdf (accessed on 18 February 2023).

- Department of Employment and Labour. Government gazette on National Minimum Wage Act: Annual Review and Adjustment of the National Minimum Wage for 2021. Available online: https://www.gov.za/sites/default/files/gcis_document/202102/44136gon76.pdf (accessed on 2 July 2021).

- Beyene, M.; Worku, A.G.; Wassie, M.M. Dietary diversity, meal frequency and associated factors among infant and young children in Northwest Ethiopia: a cross- sectional study. BMC Public Health 2015, 3, 1007. [CrossRef]

- Harris-Fry, H.; Azad, K.; Kuddus, A.; Shaha, S.; Nahar, B.; Hossen, M.; Younes, L.; Costello, A.; Fottrell, E. Socioeconomic determinants of household food security and women’s dietary diversity in rural Bangladesh: a cross-sectional study. J Health Popul Nutr. 2015, 10, 2. [CrossRef]

- Mullins, L.; Charlebois, S.; Finch, E.; Music, J. Home Food Gardening in Canada in Response to the COVID-19 Pandemic. Sustainability 2021, 13, 3056. [CrossRef]

- Ogundiran, O.A.; Monde, N.; Agholor, I.; Odeyemi, A.S. The Role of Home Gardens in Household Food Security in Eastern Cape: A Case Study of Three Villages in Nkonkobe Municipality. J. Agric. Sci. 2013, 6, 129-136. [CrossRef]

- Bettencourt, E.M.V.; Tilman, M.; Narciso, V.; da Silva Carvalho, M.L.; de Sousa Henriques, P.D. The Livestock Roles in the Wellbeing of Rural Communities of Timor-Leste. Rev. Econ. Sociol. 2015, 53, S063-S080. [CrossRef]

- Roberto, C.A.; Swinburn, B.; Hawkes, C.; Huang, T.T.; Costa, S.A.; Ashe, M.; Zwicker, L.; Cawley J.H.; Brownell, K.D. Patchy progress on obesity prevention: emerging examples, entrenched barriers, and new thinking. Lancet 2015, 385, 2400-2409. [CrossRef]

- Lang, T. Reshaping the food system for ecological public health. J Hunger Environ Nutr. 2009, 4, 315-335. [CrossRef]

- United Nations Children’s Emergency Fund - UNICEF. The state of food security and nutrition in the world: safeguarding against economic slowdowns and downturns. Available online: https://www.unicef.org/media/55921/file/SOFI-2019-full-report.pdf (accessed on 13 July 2021).

- O’Halloran, S.A.; Eksteen, G.; Polayya, N.; Ropertz, M.; Senekal, M. The Food Environment of Primary School Learners in a Low-to-Middle-Income Area in Cape Town, South Africa. Nutrients 2021, 13, 2043. [CrossRef]

- Marraccini, T.; Meltzer, S.; Bourne, L.; Draper, C.E. A qualitative evaluation of exposure to and perceptions of the Woolworths healthy tuck shop guide in Cape Town, South Africa. Child. Obes. 2012, 8, 369-377. [CrossRef]

- de Villiers, A.; Steyn, N.P.; Draper, C.E.; Fourie, J.M.; Barkhuizen, G.; Lombard, C.J.; Dalais, L.; Abrahams, Z.; Lambert, E.V. “HealthKick”: Formative assessment of the health environment in low-resource primary schools in the Western Cape Province of South Africa. BMC Public Health 2012, 12, 794. [CrossRef]

- Temple, N.J.; Steyn, N.P.; Myburgh, N.G.; Nel, J.H. Food items consumed by students attending schools in different socioeconomic areas in Cape Town, South Africa. Nutr. 2006, 22, 252-258. [CrossRef]

- Kroll, F.; Swart, E.C.; Annan, R.A.; Thow, A.M.; Neves, D.; Apprey, C.; Aduku, L.N.E.; Agyapong, N.A.F.; Moubarac, J.-C.; Toit, A.d.; Aidoo, R.; Sanders, D. Mapping Obesogenic Food Environments in South Africa and Ghana: Correlations and Contradictions. Sustainability 2019, 11, 3924. [CrossRef]

- Chai, W.; Fan, J.X.; Wen, M. Association of individual and neighbourhood factors with home food availability: evidence from the National Health and nutrition examination survey. J Acad Nutr Diet 2018, 118, 815-823. [CrossRef]

- National Agricultural Marketing Council - NAMC. Food Price Monitor: August Issue. Available online: https://www.namc.co.za/wp-content/uploads/2017/09/NAMC-Food-Price-Monitor-31-Aug-2016.pdf (accessed on 2 July 2021).

- Castro, I.A.; Majmundar, A.; Williams, C.B.; Baquero, B. Customer Purchase Intentions and Choice in Food Retail Environments: A Scoping Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 2493. [CrossRef]

- Faber, M.; Witten, C.; Drimie, S. Community-based agricultural interventions in the context of food and nutrition security in South Africa. South Afr J Clin Nutr 2011, 24, 21-30. [CrossRef]

- Tambe, B.A.; Tchuenchieu, A.K.; Tchuente, B.T.; Edoun, F.E.; Mouafo, H.T.; Kesa, H.; Medou, G.N. The state of food security and dietary diversity during the Covid-19 pandemic in Cameroon. J. Health Res. 2021, 6, 1-11. Available online: https://www.ikprress.org/index.php/JOMAHR/article/view/6216 (accessed on 16 July 2022).

- Chakona, G.; Shackleton, C. Minimum Dietary Diversity Scores for Women Indicate Micronutrient Adequacy and Food Insecurity Status in South African Towns. Nutrients 2017, 9, 812. [CrossRef]

- Morseth, M.S.; Grewal, N.K.; Kaasa, I.S.; Hatloy, A.; BarikmoI, I.; Henjum, S. Dietary diversity is related to socioeconomic status among adult Saharawi refugees living in Algeria. BMC Public Health 2017, 17, 621. [CrossRef]

- Taruvinga, A.; Muchenje, V.; Mushunje, A. Determinants of rural household dietary diversity: The case of Amatole and Nyandeni districts, South Africa. Int. J. Sustain. Dev. 2013, 2, 2233-2247. https://isdsnet.com/ijds-v2n4-4.pdf (accessed on 1 July 2021).

- Nabuuma, D.; Ekesa, B.; Faber, M.; Mbhenyane, X.G. Food security and food sources linked to dietary diversity in rural smallholder farming households in central Uganda. AIMS Agric. Food 2021, 6, 644-662. [CrossRef]

- World Food Programme - WFP. Comprehensive Food Security and Vulnerability Analysis (CFSVA): Democratic Republic of Congo. Available online: https://documents.wfp.org/stellent/groups/public/documents/ena/wfp266329.pdf (accessed on 13 July 2021).

- Sharma, J.R.; Mabhida, S.E.; Myers, B.; Apalata, T.; Nicol, E.; Benjeddou, M.; Muller, C.; Johnson, R. Prevalence of Hypertension and Its Associated Risk Factors in a Rural Black Population of Mthatha Town, South Africa. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 1215. [CrossRef]

- Crush, J.; Caesar, M. City Without Choice: Urban Food Insecurity in Msunduzi, South Africa. Urban Forum 2014, 25, 165-175. [CrossRef]

- World Health Organisation - WHO (2021). Fact sheet: Overweight and Obesity. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/obesity-and-overweight (accessed on 6 October 2021).

- Cois, A.; Day, C. Obesity trends and risk factors in the South African adult population. BMC Obesity 2015, 2,42. [CrossRef]

- Statistics South Africa - Stats SA. South Africa Demographic and Health Survey: Key indicator report. Available online: https://www.statssa.gov.za/publications/Report%2003-00-09/Report%2003-00-092016.pdf (accessed on 6 October 2021).

- Cheteni, P. Youth Participation in Agriculture in the Nkonkobe District Municipality, South Africa. J Hum. Ecol. 2016, 55,207-213. Available at https://www.econstor.eu/bitstream/10419/162735/1/Youth%20Participation%20in%20Agriculture%20in%20the%20Nkonkobe%20District%20Municipality.pdf (accessed on 1 July 2021).

- World Health Organisation - WHO. Global report on diabetes. Available online: https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/204871/9789241565257_eng.pdf (accessed on 7 October 2021).

- The Heart and Stroke Foundation South Africa. Cholesterol. Available online: https://www.heartfoundation.co.za/cholesterol/ (accessed on 11 October 2021).

- Virani, S.S. Alonso, A.; Aparicio, H.J.; Benjamin, E.J.; Bittencourt, M.S.; Callaway, C.W.; Carson, A.P.; Chamberlain, AM.; Cheng, S.; Delling, S.F.; et al. Heart disease and stroke statistics-2021 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation 2021, 143, e254-e743. [CrossRef]

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence - NICE. Hypertension in adults: diagnosis and management. Available online: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng136/resources/hypertension-in-adults-diagnosis-and-management-pdf-66141722710213 (accessed on 7 October 2021).

| Interpretation | Classifications (kg/m²) |

|---|---|

| Underweight | < 18.5 |

| Normal | 18.5 - 24.99 |

| Overweight | 25 - 29.99 |

| Obese class 1 | 30 - 34.99 |

| Obese class 2 | 35 - 39.99 |

| Obese class 3 | > 40 |

| Frequency (n) | Percentage (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Age (years)* | ||

| 18-35 | 210 | 49.2 |

| 36-55 | 156 | 36.5 |

| >55 | 61 | 14.3 |

| Marital status | ||

| Single | 248 | 57.8 |

| Married | 119 | 27.7 |

| Divorced | 13 | 3.0 |

| Widowed | 25 | 5.8 |

| Cohabitation | 22 | 5.1 |

| Other | 2 | 0.5 |

| Gender | ||

| Female | 345 | 80.4 |

| Male | 84 | 19.6 |

| Education | ||

| Never attended school | 21 | 4.9 |

| Primary education (grade 1-7) | 26 | 6.1 |

| Secondary education (grade 8-12) | 232 | 54.1 |

| Tertiary education (degree, diploma, etc.) | 146 | 34.0 |

| Other | 4 | 0.9 |

| Variables | % | Mean | Std. Deviation |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Random blood glucose (mmol/L) Normal (< 11.1) Diabetes (>11.1) |

67.5 32.5 |

9.7386 | 3.4863 |

|

Total blood cholesterol (mmol/L) Normal (<5.0) At risk (< 7.5) |

93.2 6.8 |

3.6893 | 0.7421 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).