Submitted:

12 May 2023

Posted:

12 May 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

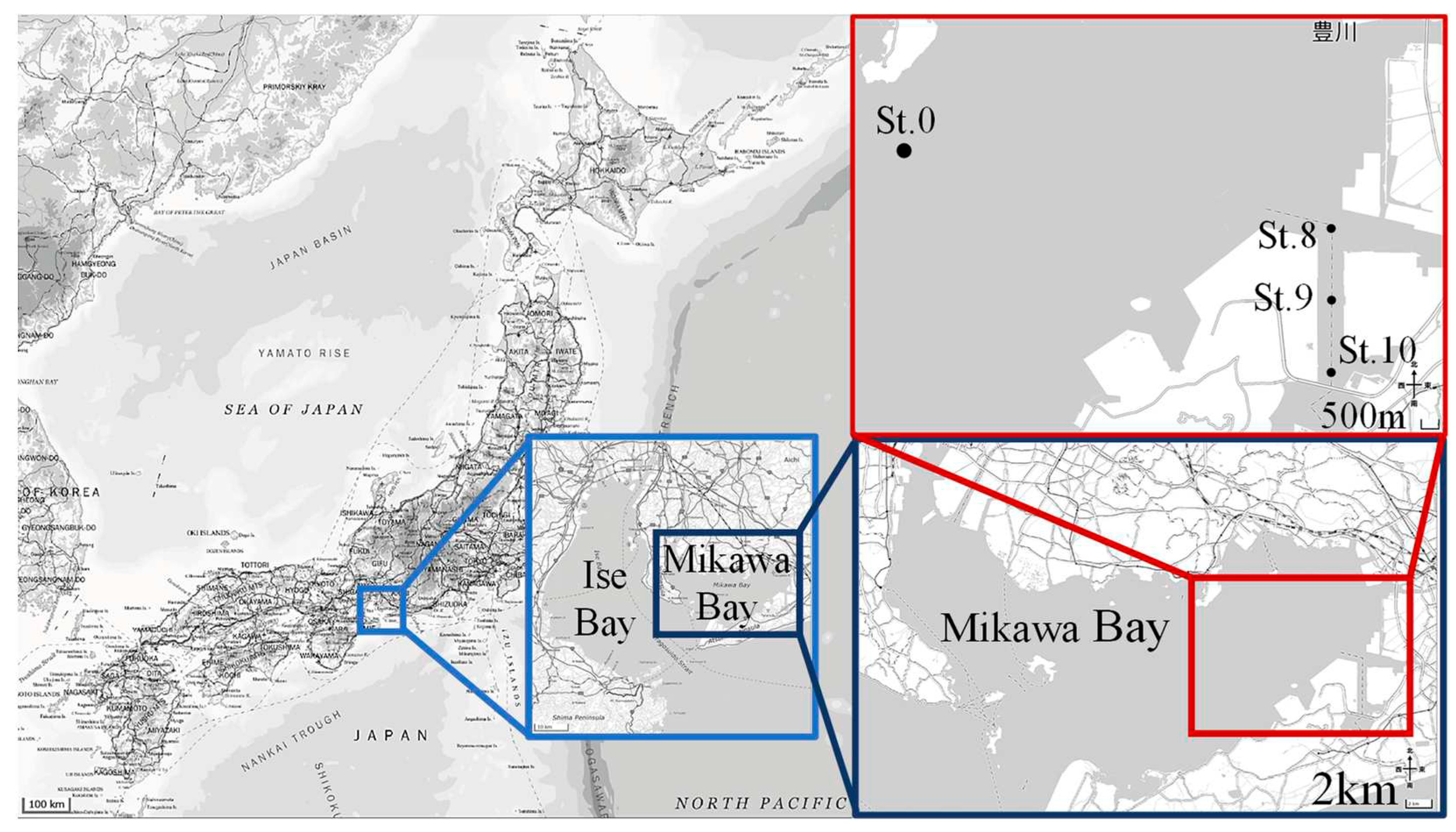

2.1. Study Area

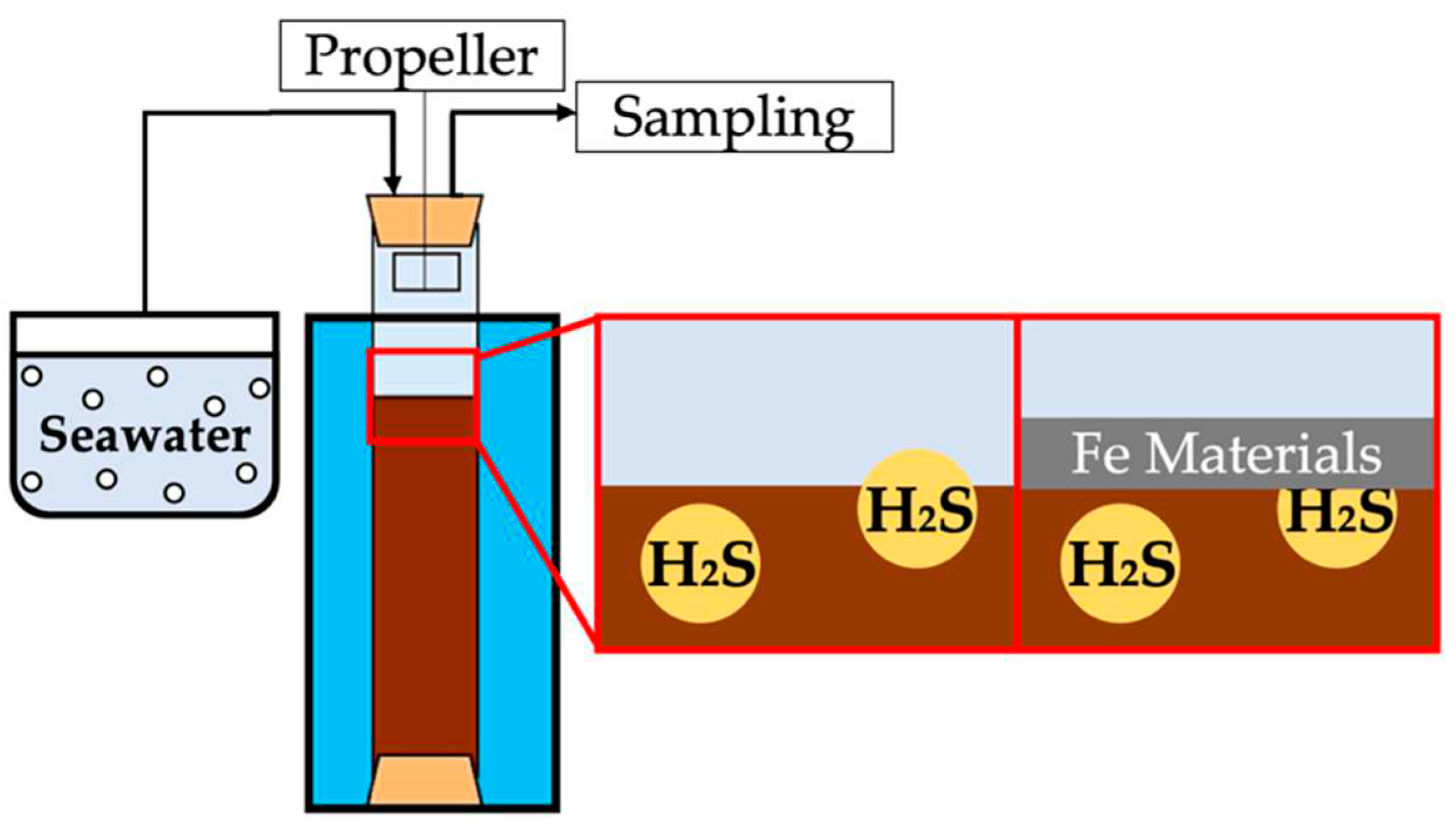

2.2. Experiments on Sulfide Release

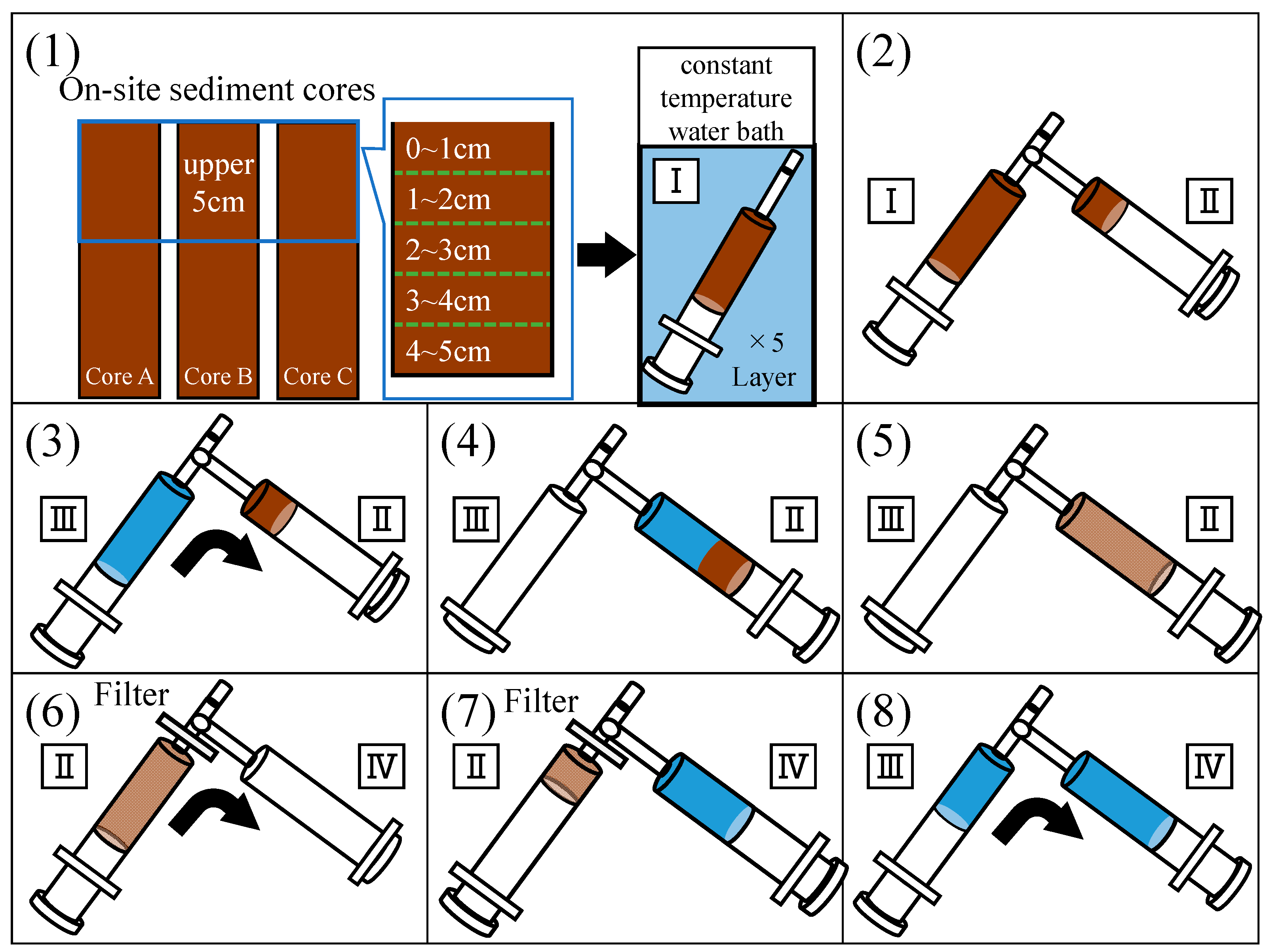

2.3. Experiment on Sulfide Production Rate

2.4. Construction of Sediment Model

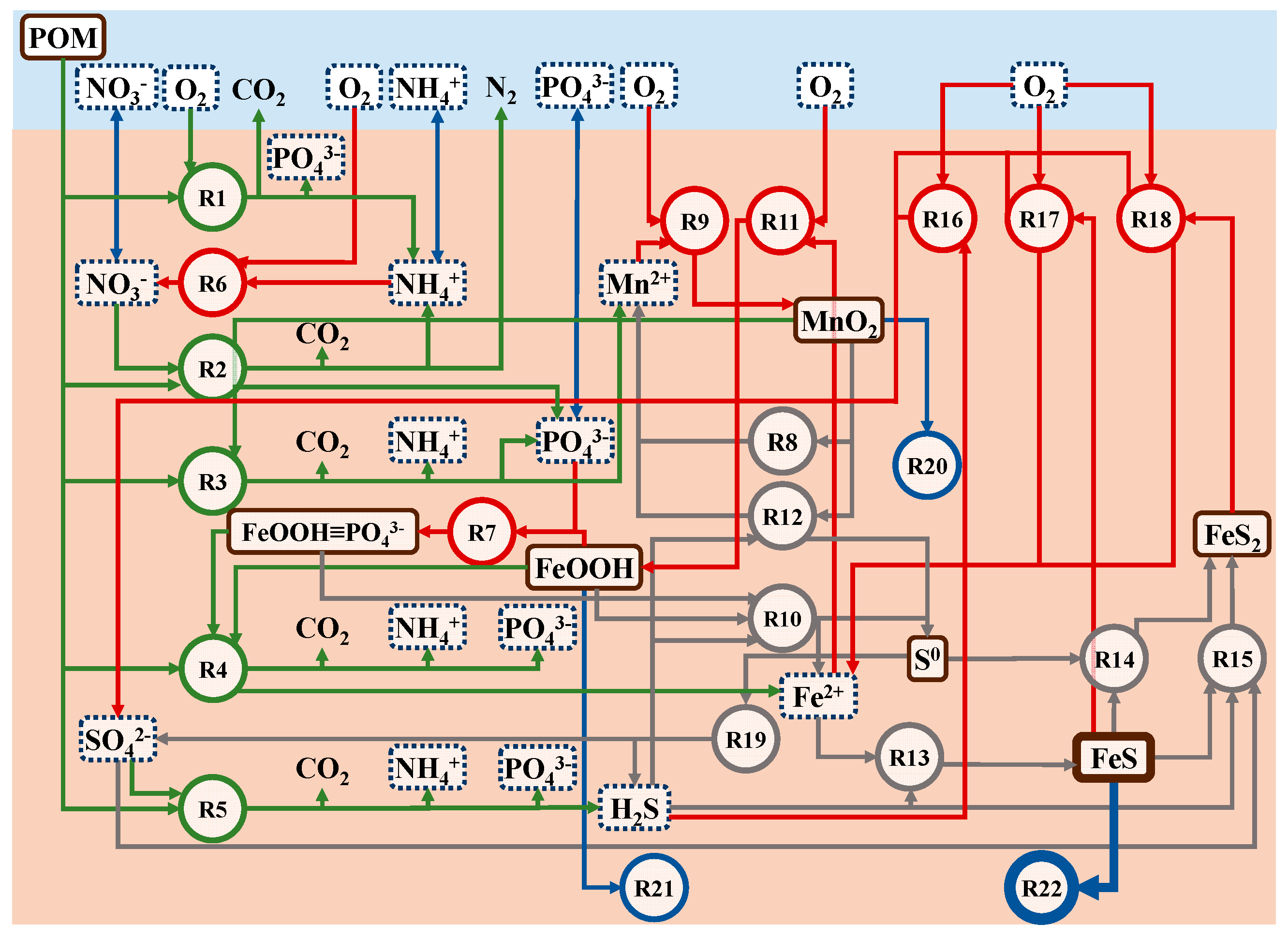

2.4.1. Production and Consumption

| Primary reactions | |

|---|---|

| O2 + CH2O → CO2 + H2O | (R1) |

| 4NO3− + 5CH2O + 4H+ → 2N2 + 5CO2 + 7H2O | (R2) |

| 2MnO2 + CH2O + 8H+ → 2Mn2+ +CO2 + 3H2O | (R3) |

| 4FeOOH + CH2O + 8H+ → 4Fe2+ + CO2 +7 H2O | (R4) |

| SO42− + 2CH2O + 2H+ → H2S + 2CO2 + 2H2O | (R5) |

| Secondary reactions | |

|---|---|

| NH4+ + 2O2 → NO3− + H2O + 2H+ | (R6) |

| FeOOH + PO43− → FeOOH≡PO43− | (R7) |

| 2Fe2+ + MnO2 + 2H2O → 2FeOOH + Mn2+ + 2H+ | (R8) |

| 2Mn2+ + O2 + 2H2O → 2MnO2 + 4H+ | (R9) |

| H2S + 2FeOOH≡PO43− + 4H+ → S0 + 2Fe2+ + 4H2O + 2PO43− | (R10a) |

| 4Fe2+ + O2 + 6H2O → 4FeOOH + 8H+ | (R11) |

| H2S + 2FeOOH + 4H+ → S0 + 2Fe2+ + 4H2O | (R10b) |

| H2S + MnO2 + 4H+ → S0 + Mn2+ + 2H2O | (R12) |

| H2S + Fe2+ → FeS + 2H+ | (R13) |

| FeS + S0 → FeS2 | (R14) |

| SO42− + 3H2S + 4FeS + 2H+ → 4FeS2 + 4H2O | (R15) |

| H2S + 2O2 → SO42− + 2H+ | (R16) |

| FeS + 2O2 → Fe2+ + SO42− | (R17) |

| 2FeS2 + 7O2 + 2H2O → 2Fe2+ + 4SO42 + 4H+ | (R18) |

| 4S0 + 4H2O → 3H2S + SO42− + 2H+ | (R19) |

| MnO2A → MnO2B | (R20) |

| FeOOHA → FeOOHB | (R21) |

| FeSA → FeSB | (R22) |

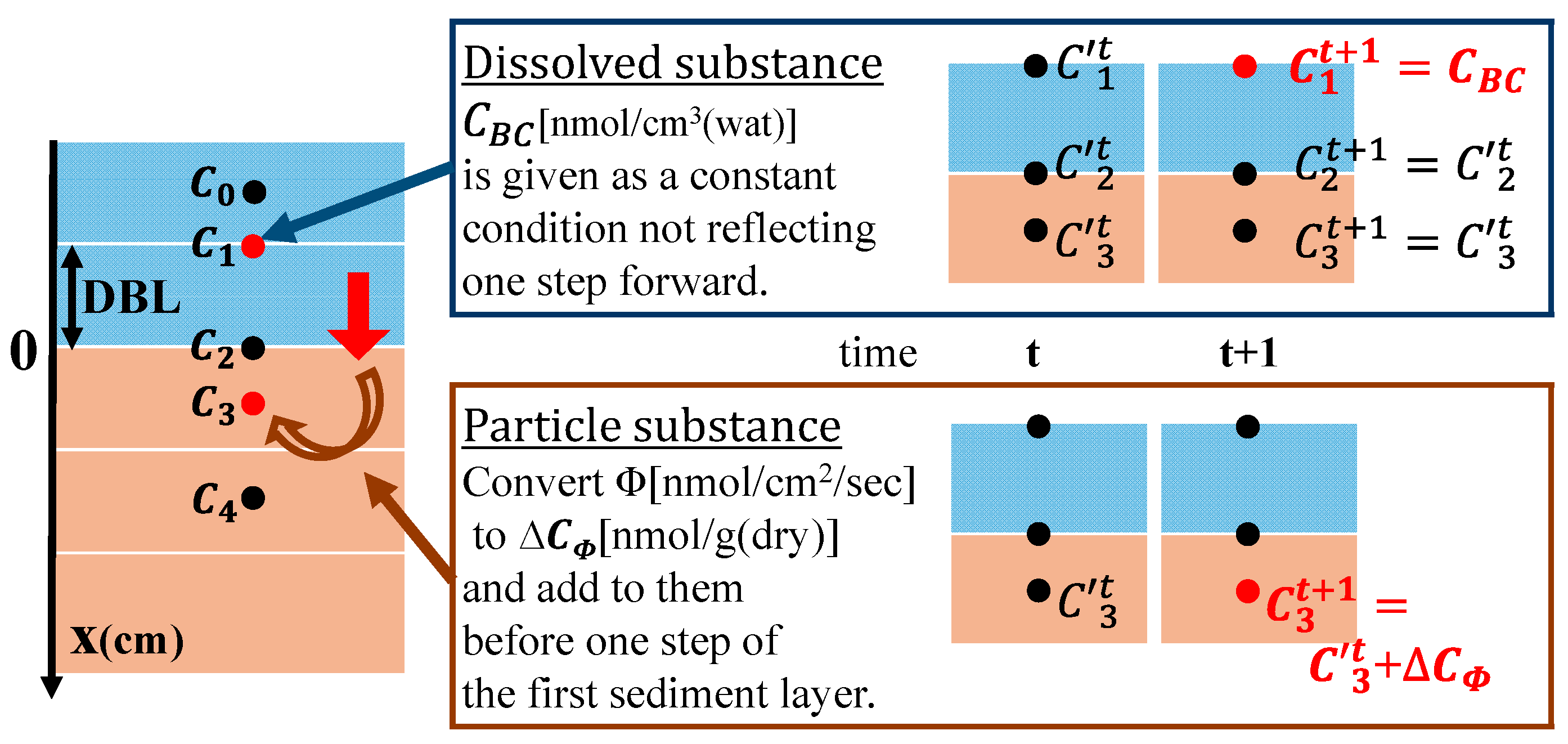

2.4.2. Boundary Condition

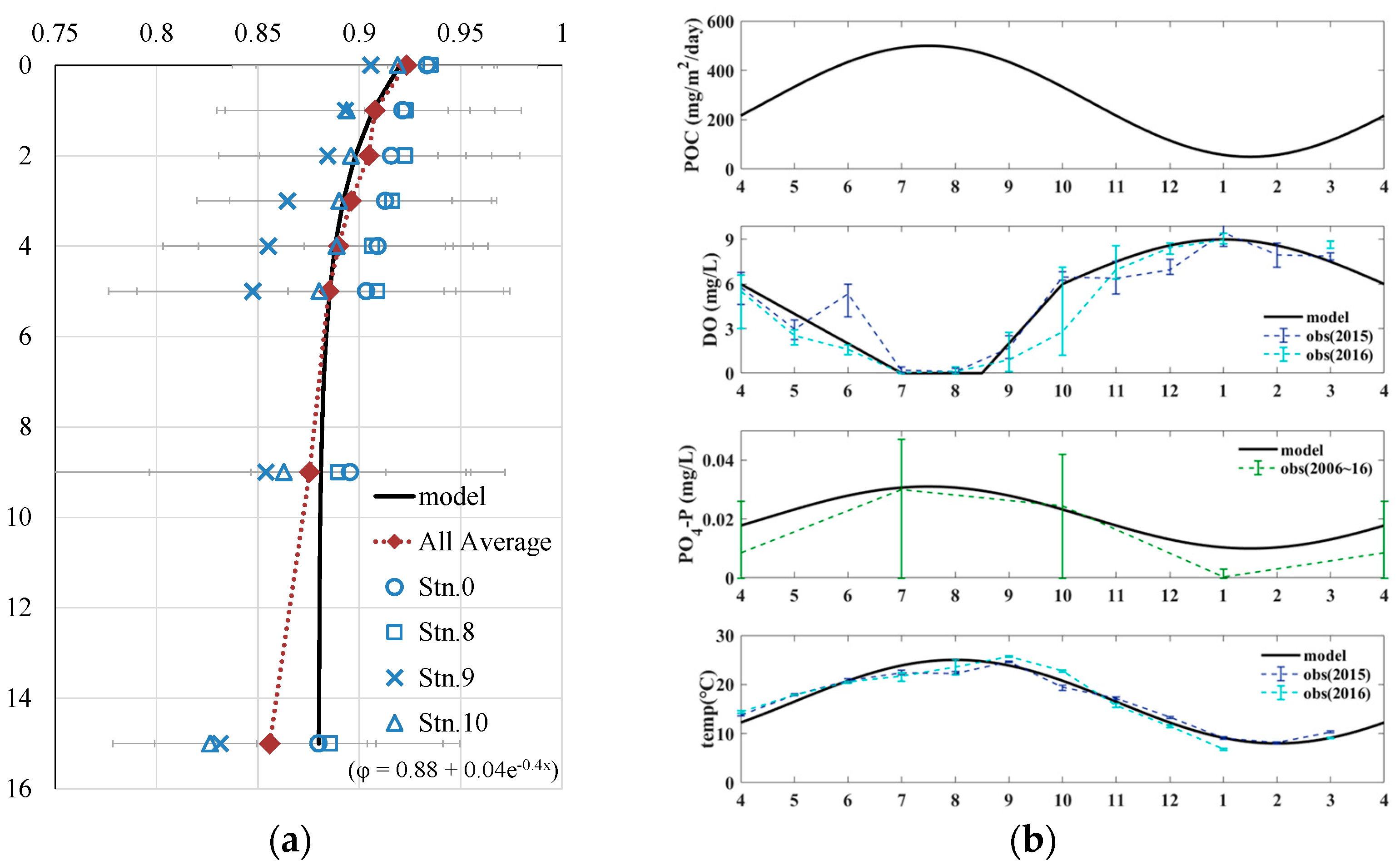

2.4.3. Reproduction of Field Observations

2.4.4. Reproduction of Experiment on Sulfides Release

3. Results

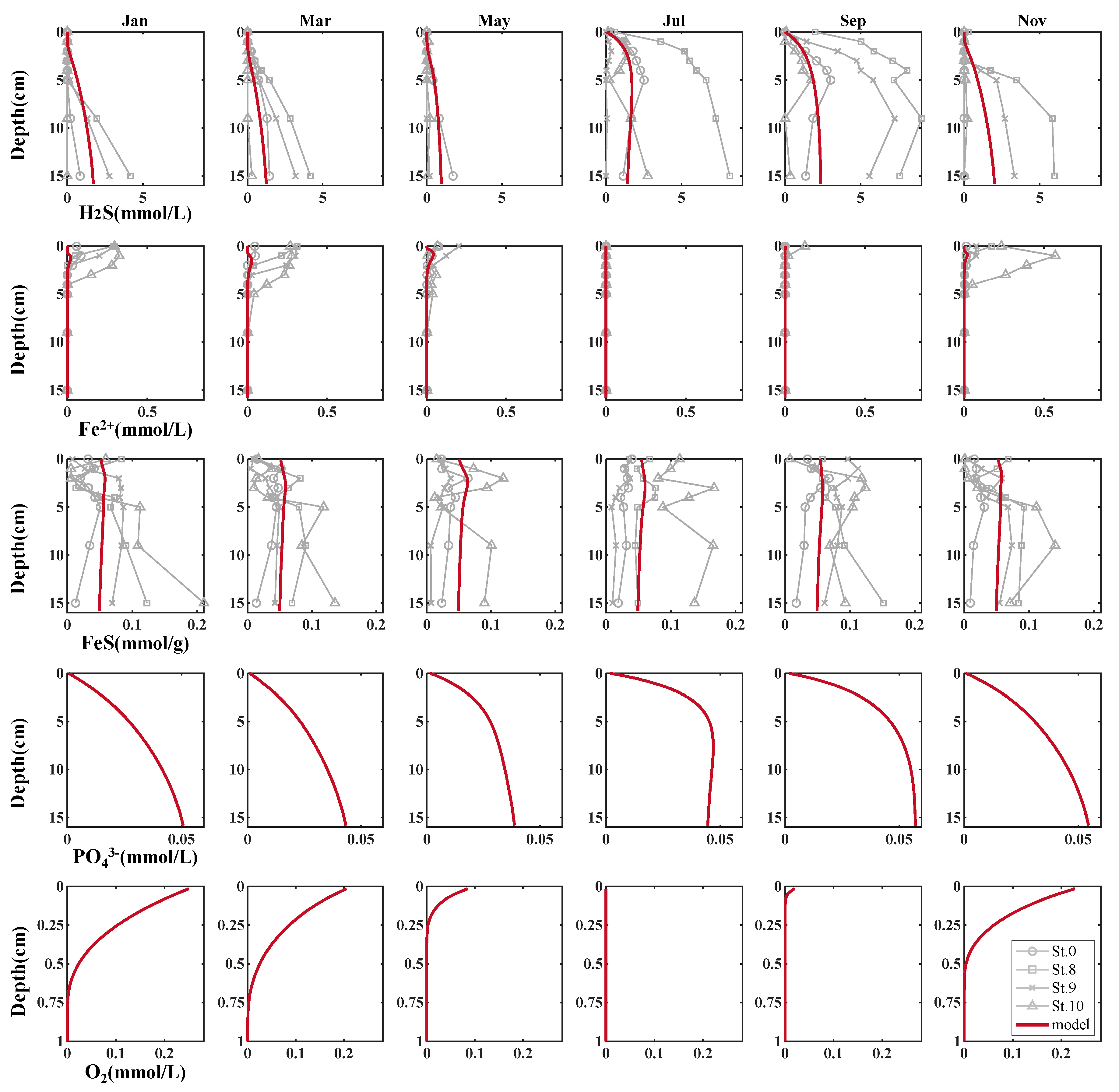

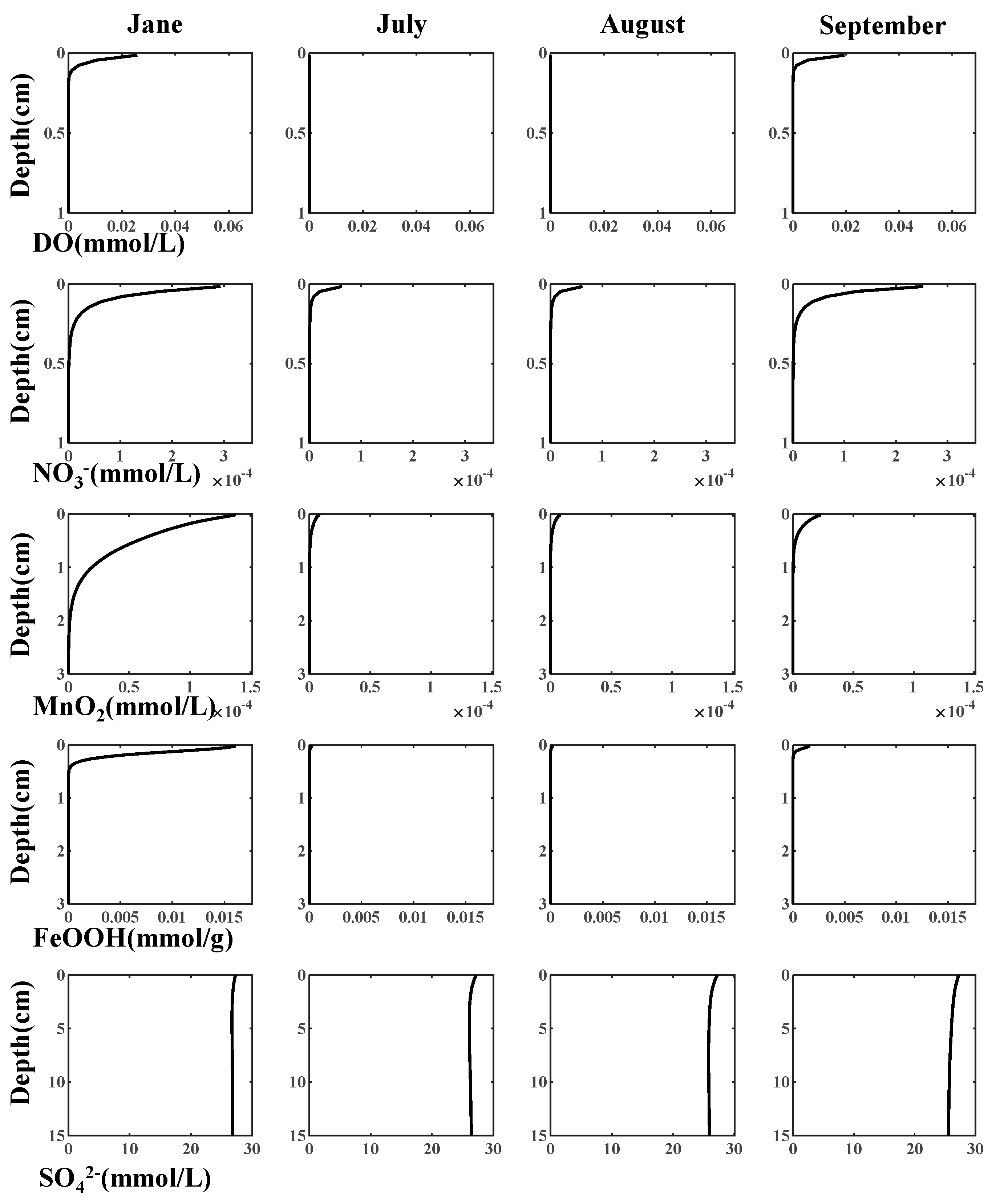

3.1. Reproduction of Field Observations

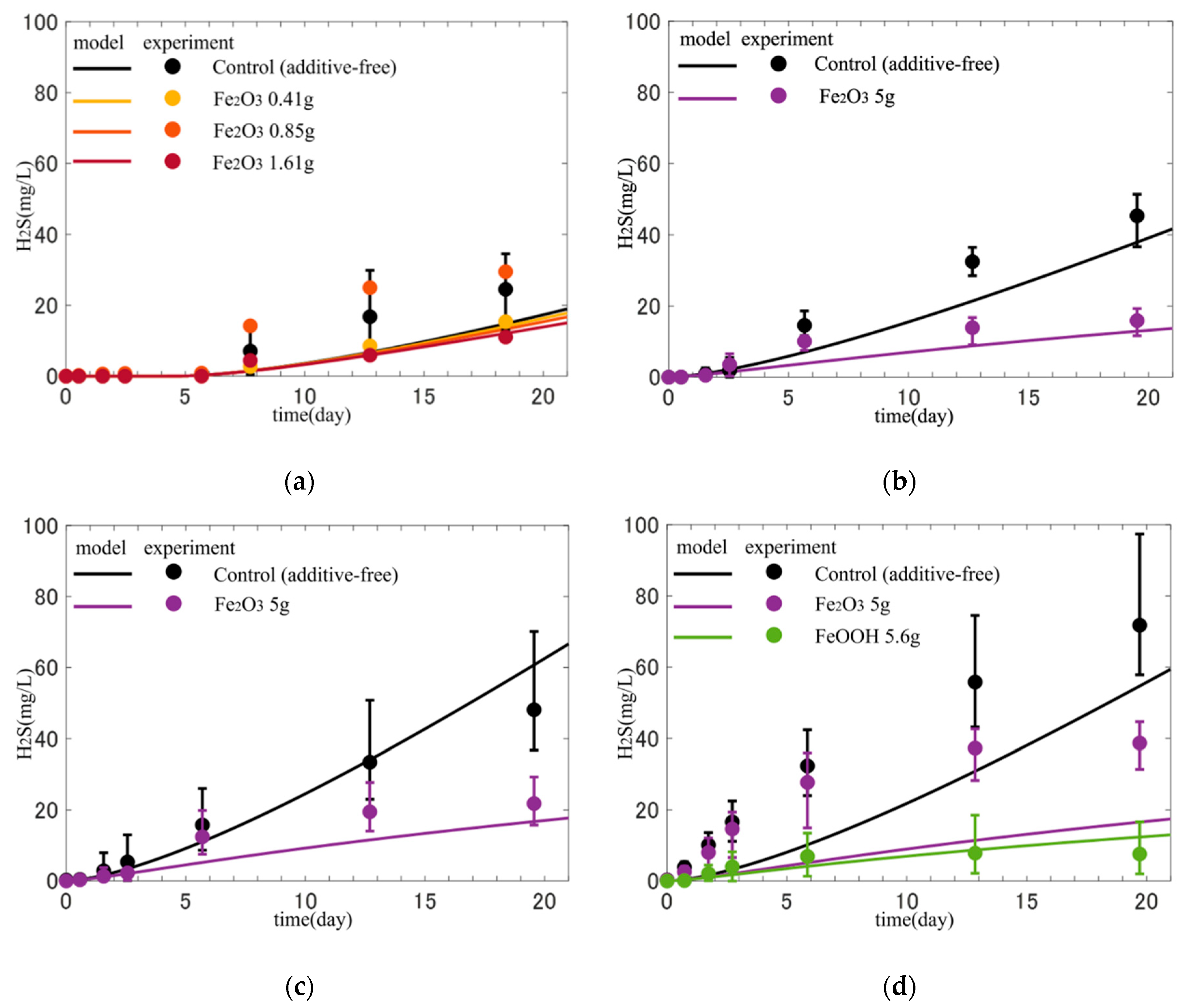

3.2. Reproduction of Sulfide Release Experiment

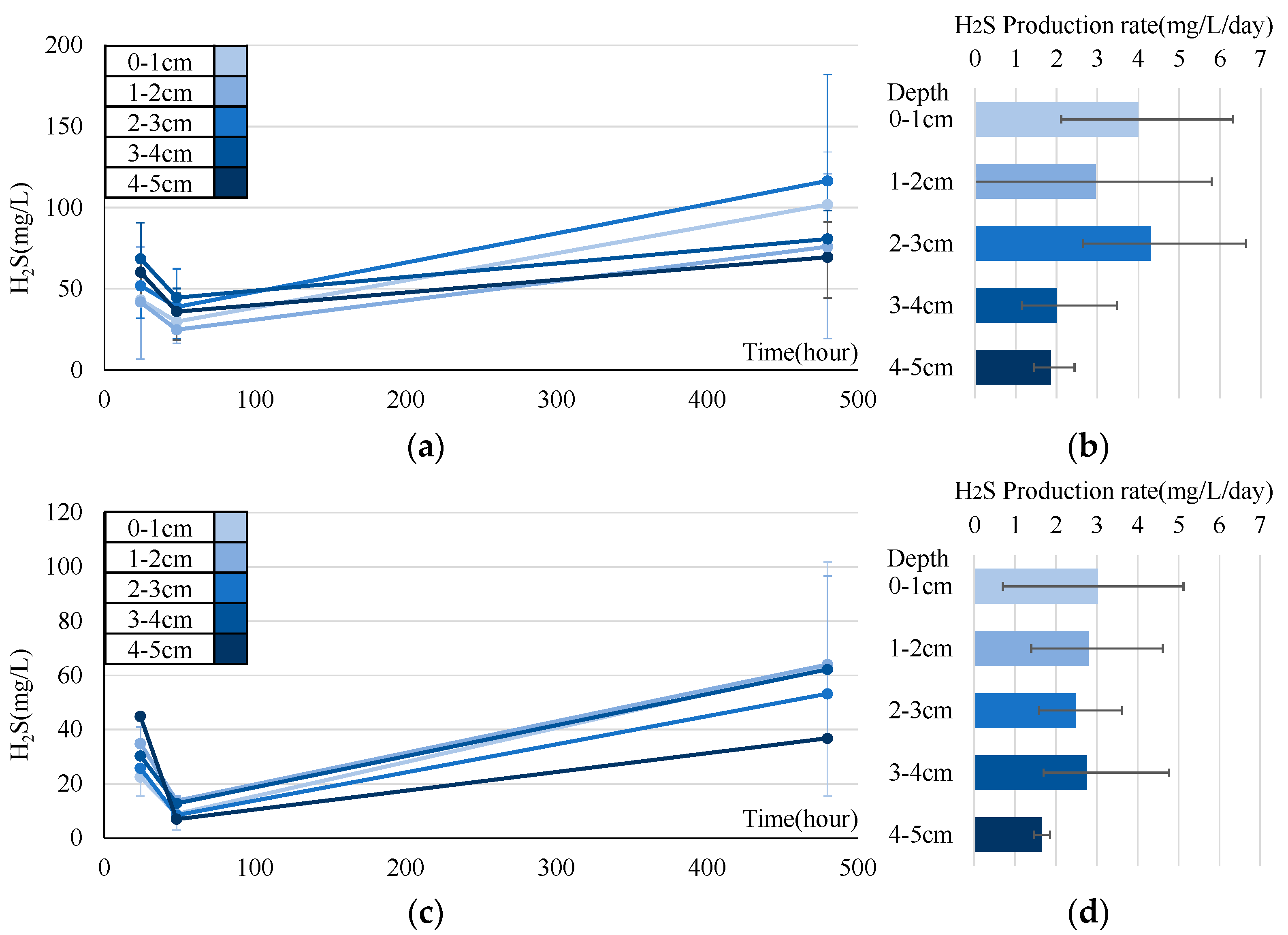

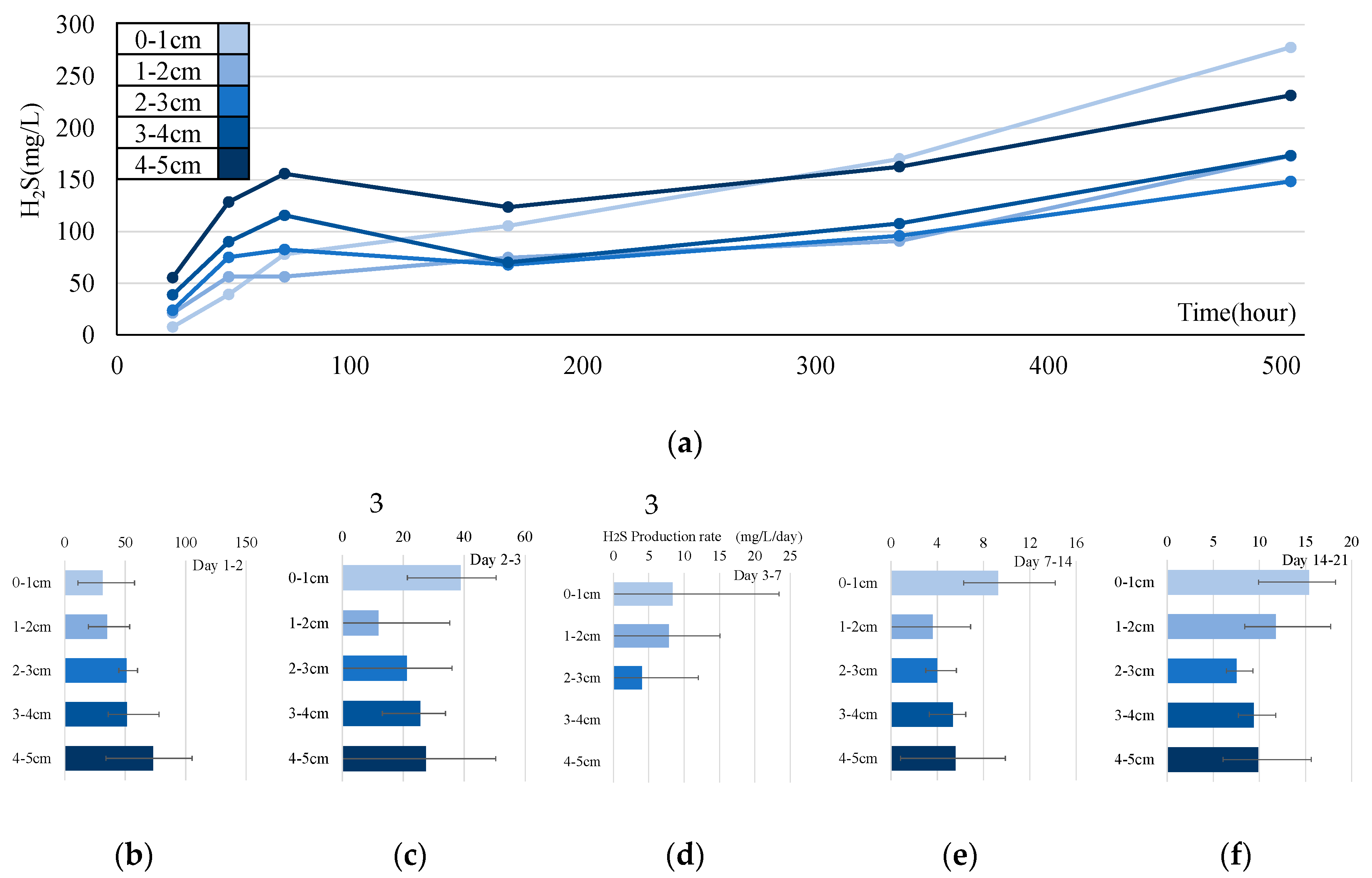

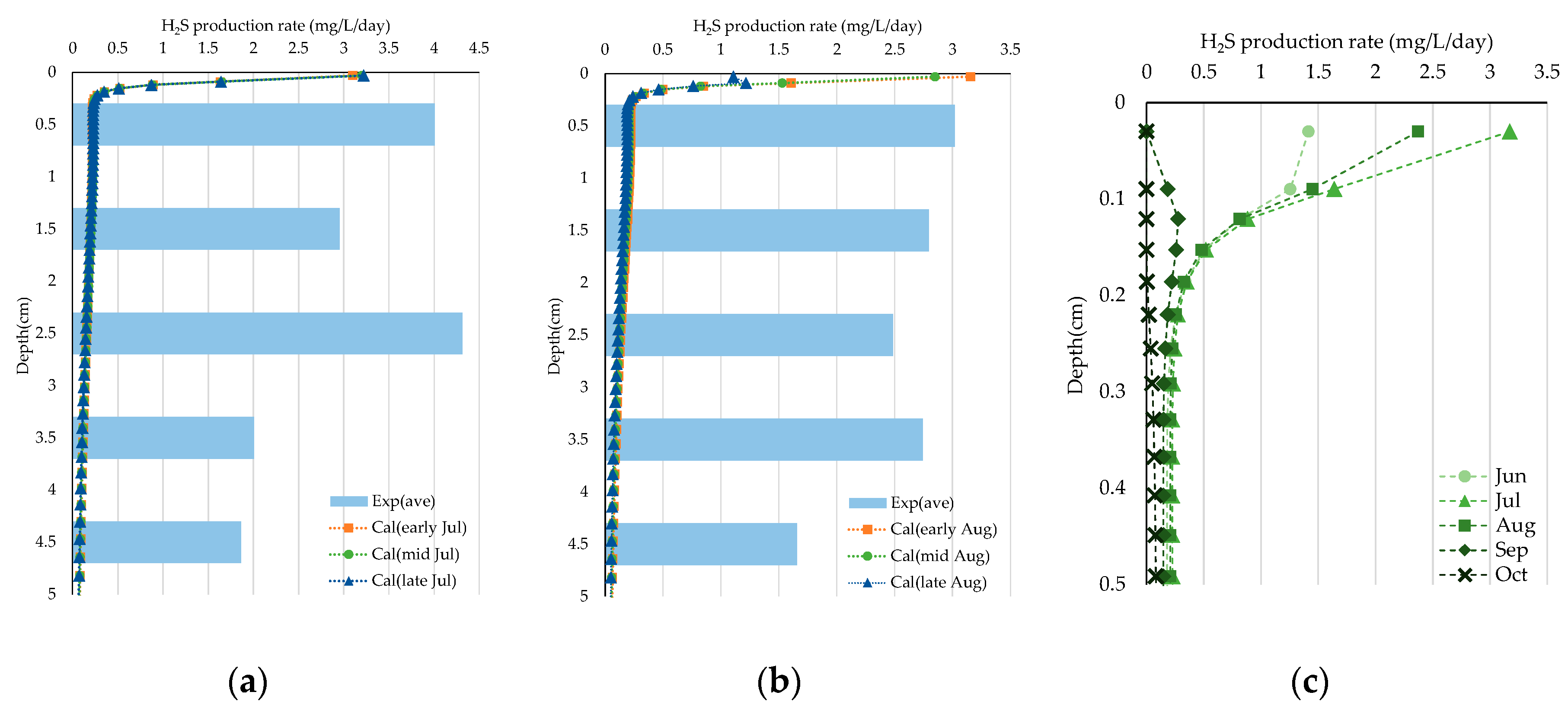

3.3. Experiment on Sulfide Production Rate

4. Discussion

4.1. Analysis of Sulfide Production Rate

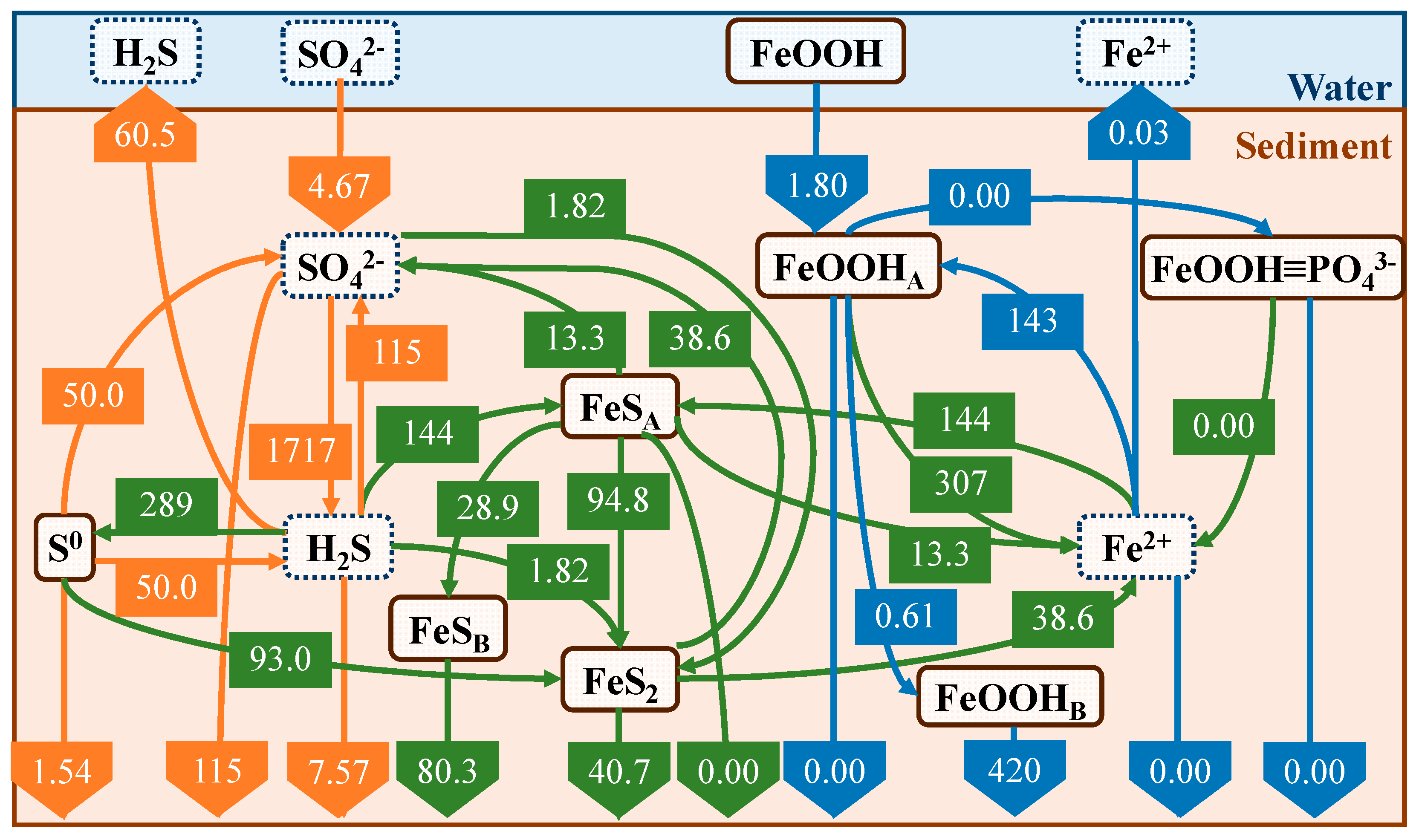

4.2. Annual Cycle of Iron and Sulfur

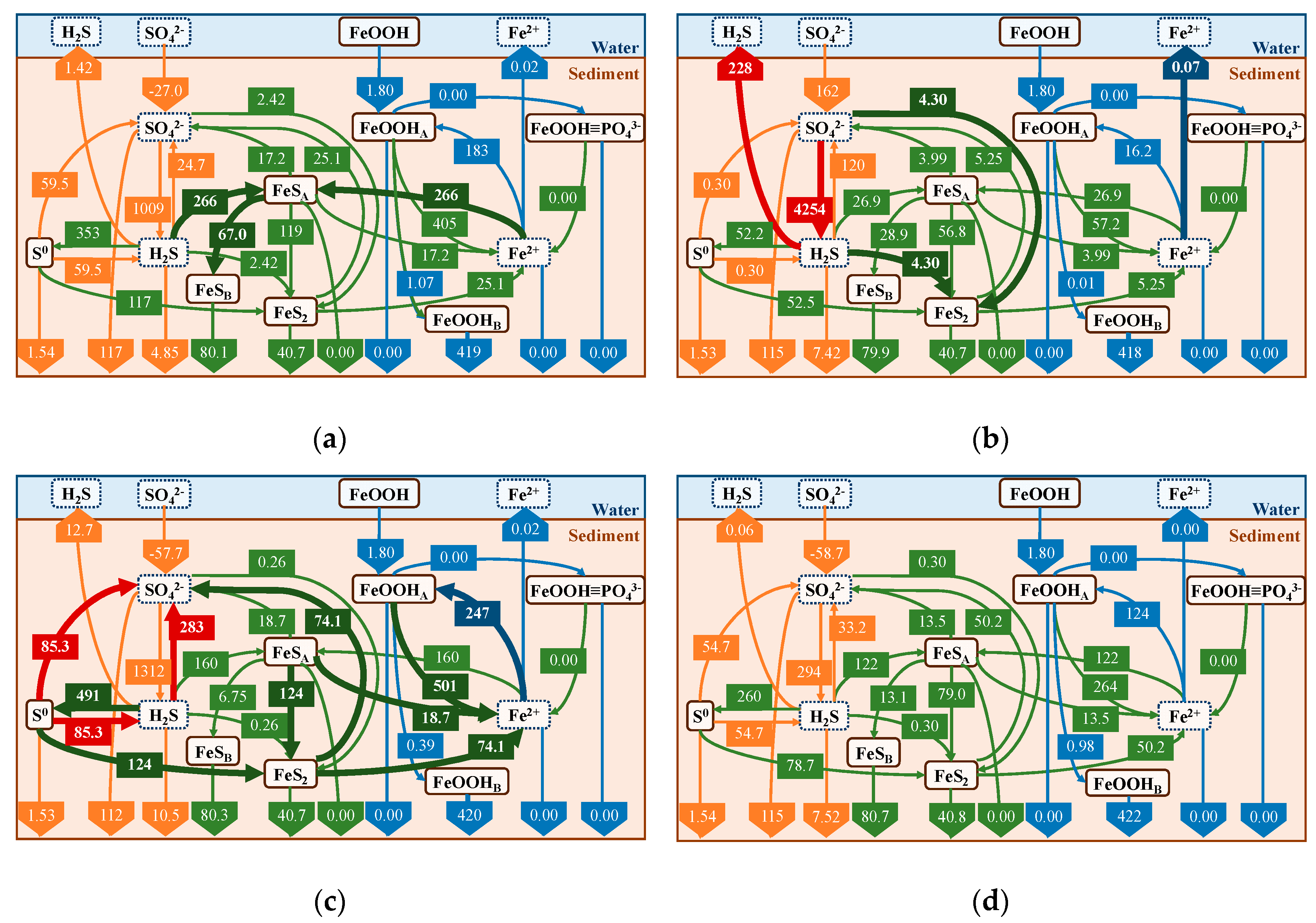

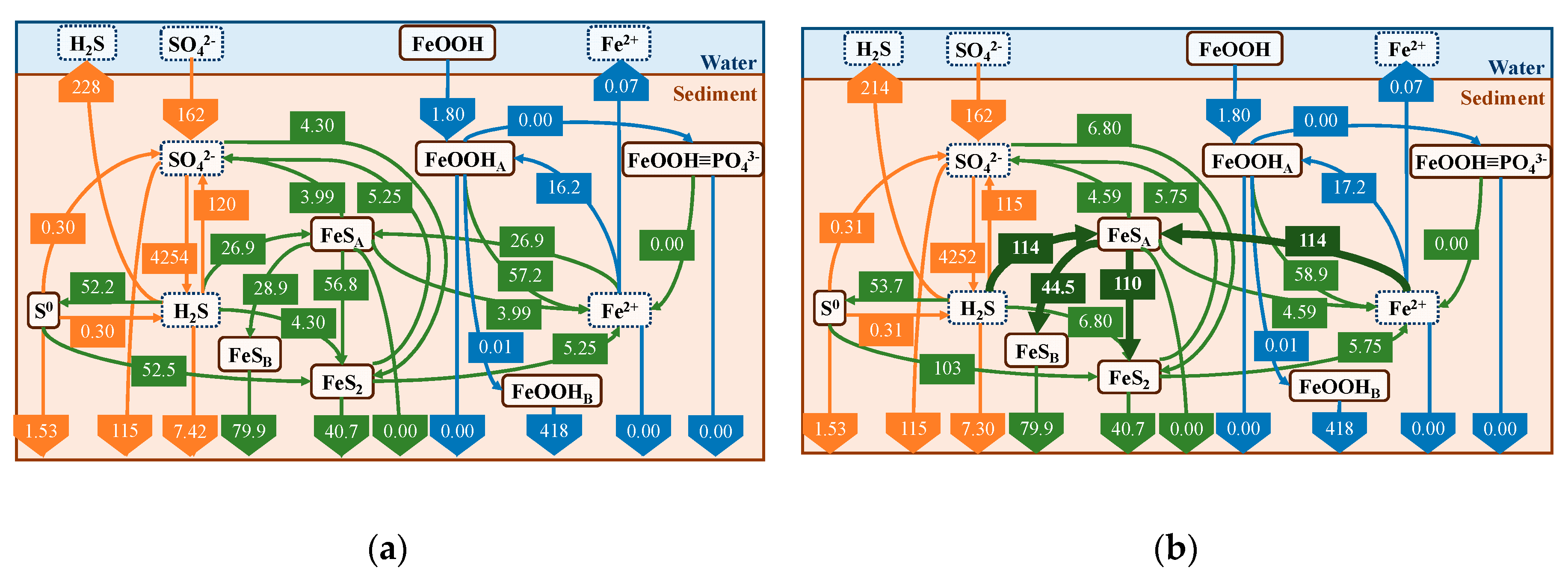

4.3. Effect of Iron Curtain

8FeS + 18O2 + 12H2O → 8FeOOH + 8SO42− + 16H+

4.4. Model Setting Conditions

4.2.1. Improvement of the reproduction accuracy of field sediments

4.2.2. Reaction of Iron Materials with Sulfides

5. Conclusions

- In the sulfide production rate experiment, we calculated the rate based on the concentration in the sediment cores during the summer months. This rate tends to increase in the upper layers over time. However, the reproducibility of the model remains an issue.

- Our model, which was developed by focusing on sulfur and iron dynamics, was able to reproduce the vertical concentration distributions of the major substances in the sediments and their seasonal trends.

- By reproducing the sulfide release experiment, our model could reproduce the effect and difference in the amount, type, and time of addition of iron materials.

- Predictive calculations for the addition of iron materials to the sediments, particularly during the summer season when the release was most prevalent, allowed us to quantify the difference in the amount of H2S released with and without the addition of iron materials in terms of fluxes.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Parameter | Value*1 | Unit | Source*2 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| diffusivity in free water | DO | 11.7 + 0.334T + 0.00505T2 | cm2/s | [5] |

| NO3− | 9.72 + 0.365T | cm2/s | [5] | |

| H2S | 8.74 + 0.264T + 0.004T2 | cm2/s | [5] | |

| SO42− | 4.96 + 0.226T | cm2/s | [5] | |

| NH4+ | 9.76 + 0.398T | cm2/s | [5] | |

| Mn2+ | 3.04 + 0.153T | cm2/s | [5] | |

| Fe2+ | 3.36 + 0.148T | cm2/s | [5] | |

| PO43− | 9.76 + 0.398T | cm2/s | [5] | |

| biodiffusivity | Particle | 3.51 × 10−6 | cm2/s | [5] |

| Dissolved | 2.8 × 10−7 | cm2/s | [5] | |

| Q10 | Primary | 3.8 | - | [5] |

| Secondary | 2.0 | - | [5] | |

| adsorption | NH4+ | 2.2 | cm3/g | [5] |

| Mn2+ | 13 | cm3/g | [5] | |

| Fe2+ | 500 | cm3/g | [5] | |

| PO43− | 2.0 | cm3/g | [5] | |

| existence ratio to carbon | C/N | 8 | - | [5] |

| C/P | 80 | - | [5] | |

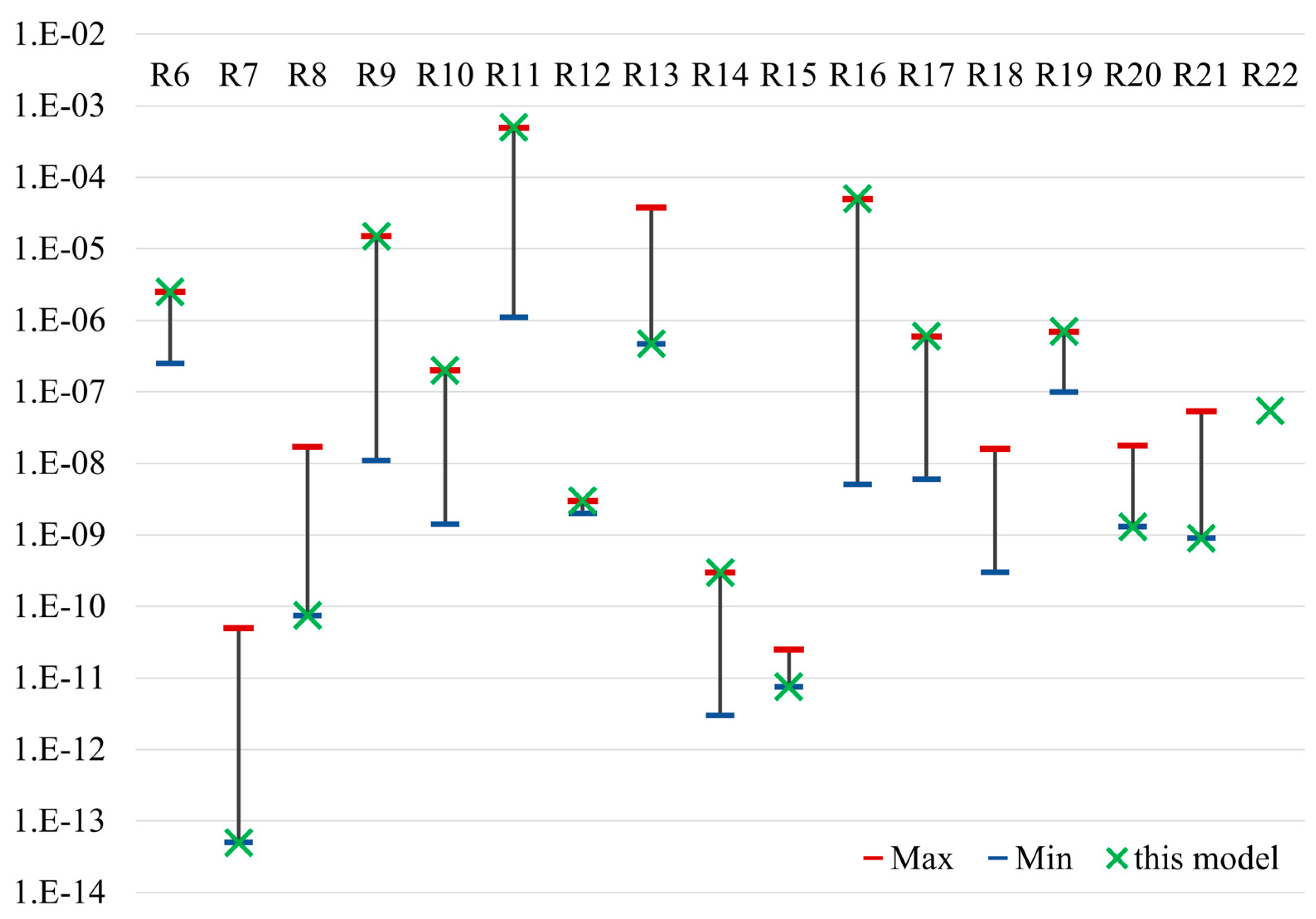

| reaction rate | R6 | 2.5 × 10−6 | /µM/s | [5] |

| R7 | 5.0 × 10−14 | /s | [12] | |

| R8 | 7.5 × 10−11 | /µM/s | [11] | |

| R9 | 1.5 × 10−5 | /µM/s | [5] | |

| R10 | 2.0 × 10−7 | /µM/s | [12] | |

| R11 | 5.0 × 10−4 | /µM/s | [5] | |

| R12 | 3.0 × 10−9 | /µM/s | [5] | |

| R13 | 3.75 × 10−5 | /µM/s | [12] | |

| R14 | 3.0 × 10−12 | cm3/nmol/s | [12] | |

| R15 | 7.5 × 10−12 | /µM/s | [12] | |

| R16 | 5.0 × 10−5 | /µM/s | [5] | |

| R17 | 6.0 × 10−7 | /µM/s | [5] | |

| R18 | 1.6 × 10−8 | /µM/s | [5] | |

| R19 | 7.0 × 10−7 | /s | [5] | |

| R20 | 1.3 × 10−9 | /s | [11] | |

| R21 | 9.0 × 10−10 | /s | [5] | |

References

- Tobler, M.; Schlupp, I.; Heubel, U.K.; Riesch, R.; de León F.J.; Giere, O.; Plath, M.; Life on the edge: hydrogen sulfide and the fish communities of a Mexican cave and surrounding waters. Extremophiles 2006, 10(6), pp.577-585. [CrossRef]

- Tsujimoto, A.; Nomura, R.; Yasuhara, M.; Yamazaki, H.; Yoshikawa, S. Impact of eutrophication on shallow marine benthic foraminifers over the last 150 years in Osaka Bay, Japan. Marine Micropaleontology 2006, 60, pp.258-268. [CrossRef]

- Fisher T. R.; Hagy III, J.D.; Boynton, W.R.; Williams, M.R.; Cultural eutrophication in the Choptank and Patuxent estuaries of Chesapeake Bay. Limnology and Oceanography 2006, 51(1, part2), pp.435-447. [CrossRef]

- Canfield, D.E.; Thamdrup, B.; Hansen, J.W. The anaerobic degradation of organic matter in Danish coastal sediments: Iron reduction, manganese reduction, and sulfate reduction. Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta 1993, 57, pp.3867-3883. [CrossRef]

- Fossing, H.; Berg, P.; Thamdrup, B.; Rysgaard, S.; Sorensen, H. M.; Nielsen, K. A model set-up for an oxygen and nutrient flux model for Aarhus Bay (Denmark). NERI Technical Report 2004, No.483.

- Inoue, T.; Hagino, Y. Effects of three iron material treatments on hydrogen sulfide release from anoxic sediments. Water Science and Technology,2022, 85(1), pp.305–318. [CrossRef]

- Ito, K.; Nishijima, W.; Shoto, E.; Okada, M. Control of Sulfide and Ammonium Release from Coastal Bottom Sediments by Converter Slag (in Japanese). Journal of Japan Society on Water Environment 1997, 20(10), pp.670-673. [CrossRef]

- Kanaya, G.; Kikuchi, E.; Precipitative removal of free hydrogen H2S from estuarine muddy sediment by iron addition (in Japanese). Northeast Asian studies 2009, 13, pp.17-28. http://hdl.handle.net/10097/44070.

- Hagino, Y.; Kobayashi, T.; Shigeoka, Y.; Inoue, T.; Nakamura, Y.; Miyatsuji, T.; An Investigation on Removal Capability of Hydrogen H2S by Iron Materials Addition to Sediments (in Japanese). Annual Conference of Japan Society on Water Environment, Sapporo, Japan, 17th March 2018.

- Ahmad Seiar, Y.; Nakamura, Y.; Miyatsuji, T.; Hagino, Y.; Kobayashi, T.; Shigeoka, Y.; Inoue, T. Remediation of Coastal Marine Sediment using Iron, ONM-CozD 2019 (In Proceedings of the 5th International Conference on Geographical Information Systems Theory, Applications and Management (GISTAM 2019)) 2019, pp.335-339. [CrossRef]

- Berg, P.; Rysgaard; S.; Thamdrup, B. Dynamic Modeling of Early Diagenesis and Nutrient Cycling. A Case Study in an Arctic Marine Sediment. American Journal of Science 2003, 303, pp.905–955. [CrossRef]

- Kasih, G. A. A.; Chiba, S.; Yamagata, Y.; Shimizu, Y.; Haraguchi, K. Numerical model on the material circulation for coastal sediment in Ago Bay, Japan. J. Marine Systems, 2009, 77, pp.4-60. [CrossRef]

- Inoue, T.; Nakamura, Y. Response of benthic soluble reactive phosphorus transfer rates to step changes in flow velocity, Journal of Soils Sediments 2012, 12, pp.1559–1567. [CrossRef]

- Inoue, T.; Sugahara, S.; Seike, Y.; Kamiya, H.; Nakamura, Y. Short-term variation in benthic phosphorus transfer due to discontinuous aeration/oxygenation operation. Limnology 2017, 18, pp.195-207. [CrossRef]

- Nagao, K.; Hata, K.; Yoshikawa, S.; Hosoda, M.; Fujiwara, T. Biogeochemical Model with Benthic-Pelagic Coupling Applied to Tokyo Bay (in Japanese). Proceedings of Coastal Engineering, JSCE 2008, 55, pp.1191-1195. [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, Y.; Nakamura, Y.; Suzuki, K.; Inoue, T.; Nishimura, Y.; Uchida, Y.; Shirasaki, M. Development of a Pelagic Ecosystem Model Considering the Microbial Loop and Field Evaluation in Ise Bay (in Japanese). Journal of Japan Society of Civil Engineers, Ser. B2 (Coastal Engineering), 2011, 67(2), pp. I_1041-I_1045. [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.; Nakamura, Y.; Sasaki, J.; Inoue, T.; Higa, H.; Suzuki, T.; Hafeez, M. A. An effective process-based modeling approach for predicting hypoxia and blue tide in Tokyo Bay. Coastal Engineering Journal, 2022, 64(3), pp.458–476. [CrossRef]

- Inoue, T., Komuro, T. Analysis of Lower Trophic Ecosystem Model and Fish Catches Using a New Fish Ecosystem Model (in Japanese). Technical Note of the Port and Airport Research Institute, 2020, 1368, pp.1–38. URL(https://www.pari.go.jp/en/report_search/detail.php?id=20200417155802).

- Kamohara, S.; Sone, R. Effect of hypoxia and sulfide on habitat and reproduction of fishes and shellfishes in Mikawa Bay. In: Proposals of the Effective Countermeasures against the Attack of Oxygen Depleted Water Mass and Blue Tide to Tidal Flat and Sea Grass Beds Enclosed by Artificial Coastline, Final Report of the Environment Research and Technology Development Fund (5-1404). 2017, pp.27-46. URL (https://www.erca.go.jp/suishinhi/seika/db/search.php?research_word).

- Miyatsuji, T.; Ahmad Seiar, Y..; Nakamura, Y.; Inoue, T.; Sugahara, S.; Hagino, Y.; Kobayashi, T.; Shigeoka, Y.; Experimental Study on Hydrogen Sulfide Release from and its Production Rates in the Sediment of Mikawa Bay (in Japanese). Annual Conference of Japan Society on Water Environment, Sapporo, Japan, 17th March 2018.

- Aoyama, H.; Kai, M.; Suzuki, T.; Nakao, T.; Imao, K. The formulation of the mortality of Japanese littleneck clam (Ruditapes phillippinarum) caused by a deficiency of dissolved oxygen in Mikawa Bay -The second attempt- (in Japanese). Journal of Advanced Marine Science and Technology Society 1998, 4(1), pp.35-40. [CrossRef]

- Sugahara, S.; Yurimoto, T.; Ayukawa, K.; Kikmoto, K.; Senga, Y.; Okumura, M.; Seike, Y. A Simple in situ Extraction Method for Dissolved Sulfide in Sandy Mud Sediments Followed by Spectrophotometric Determination and Its Application to the Bottom Sediment at the Northeast of Ariake Bay (in Japanese). The Japan Society for Analytical Chemistry 2010, 59(12), pp.1155-1161. [CrossRef]

- Yamamoto Y.; Nakata, K.; Suzuki, T. Research on process of formation of oxygen depleted water mass in Mikawa Bay (in Japanese). Journal of Advanced Marine Science and Technology Society 2008, 14(1), pp.1-14. [CrossRef]

- Wide-area Comprehensive Water Quality Survey by the Ministry of the Environment URL (https://water-pub.env.go.jp/water-pub/mizu-site/mizu/kouiki/dataMap.asp) (measurement site: Aichi Prefecture No.61, reference period: 2006-2016).

- Smolders, A. J. P.; Lamers, L. P. M.; Lucassen, E. C. H. E. T.; Van der velde, G.; Roelofs, J. G. M. Internal eutrophication: How it works and what to do about it – a review. Chemistry and Ecology 2006, 22(2), pp.93-111. [CrossRef]

- Holmer, M.; Storkholm, P. Sulphate reduction and sulphur cycling in lake sediments: a review. Freshwater Biology, 2001, 46, pp.431-451. [CrossRef]

- Lamers, L. P. M.; Els ten dolle, G.; Van den berg, S. T. G.; Van delft, S. P. J.; Roelofs, J. G. M. Differential responses of freshwater wetland soils to sulphate pollution. Biogeochemistry, 2001, 55, pp.87–102. [CrossRef]

- Iwata, S.; Endo, T.; Inoue, T.; Yokota, K.; Okubo, Y. Runoff Characteristics of Nutrient Loads from Small Rivers - Case of the Hamada River, Aichi Prefecture -. Journal of Japan Society on Water Environment 2013, 36(2), pp.39-47. [CrossRef]

- Otsuka, H.; Furuta, M.; Yamamoto, H.; Arakawa, Y. Estimation of yearly mass loading of iron, phosphorus and manganese in a river by the use of concentration correlations to automatically monitored turbidity. Bulletin of Aichi Environmental Research Center, 1981, 9, pp.40-45.

- Wijsman, J. W. M.; Herman, P. M. J.; Middelburg, J. J.; Soetaert, K. A model for Early Diagenetic Processes in Sediments of the Continental Shelf of the Black Sea, Estuarine, Coastal and Shelf Science 2002, 54(3), pp.403-421. [CrossRef]

- Sum, j.; Zhou, J.; Shang, C.; Kikkert, G.A. Removal of aqueous hydrogen sulfide by granular ferric hydroxide—Kinetics, capacity and reuse. Chemosphere 2014, 117, pp.324–329. [CrossRef]

- Afonso, M.D.S.; Stumm, W. Reductive dissolution of iron (III) (hydr)oxides by hydrogen sulfide. Langmuir 1992, 8(6), pp.1671-1675. [CrossRef]

| June | July | August | September |

|---|---|---|---|

| control (3)* | control (3) | control (3) | control (3) |

| Fe2O3 0.41 g (1) 0.85 g (1) 1.61 g (1) |

Fe2O3 5 g (3) |

Fe2O3 5 g (3) |

Fe2O3 5 g (3) |

| FeOOH 5.6 g (3) |

| Dissolved | Particle | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| No adsorption | Adsorption | ||

| DO | NH4+ | S0 | MnO2 |

| NO3− | Mn2+ | FeS2 | FeOOH |

| H2S | Fe2+ | FeS | FeOOH≡PO43− |

| SO42− | PO43− | POC | |

| Symbol | Parameter | Unit |

|---|---|---|

| concentration | dissolved: nmol/cm3(wat)* particle: nmol/g(dry) |

|

| time | s | |

| vertical coordinates | cm (sed) | |

| porosity | cm3 (wat)/cm3 (sed) | |

| sedimentation rate | cm (sed)/s | |

| density | g (dry)/cm3 (dry) | |

| adsorption coefficient | cm2 (wat)/g (dry) | |

| biodiffusivity of solutes | cm2 (sed)/s | |

| biodiffusivity of solids | cm2 (sed)/s | |

| sediment diffusivity | cm2 (sed)/s | |

| production and consumption | nmol/cm3(sed)/s | |

| particle = 0, dissolved = 1 | ||

| particle or dissolved with adsorption = 1 dissolved without adsorption = 0 |

||

| Parameter | Value | Unit | Source*1 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| porosity | Figure 6(a) | - | [19] | |

| density | 2.69 | g (dry)/cm3 | ||

| sedimentation rate | 0.5 | cm (sed)/year | ||

| yotal POC flux | Figure 6(b) | mg/m2/d | [23] | |

| POC ratio (f:s:n) | 1:2:7 | - | ||

| decomposition rate | POCf | 1.4 × 10−7 | /s | [12] |

| POCs | 1.4 × 10−8 | /s | [12] | |

| POCn | 1.4 × 10−10 | /s | [12] | |

| flux (B.C.)*2 | MnO2 | 2.0 × 10−2 | mmol/m2/d | [11] |

| FeOOH | 1.8 | mmol/m2/d | [11] | |

| MnO2A/MnO2B | 0.5 | - | [5] | |

| FeOOHA/FeOOHB | 0.5 | - | [5] | |

| concentration (B.C.) | SO42− | 2500 | mmol/cm3 (wat) | [5] |

| H2S | 0 | mmol/cm3 (wat) | [5] | |

| DO | Figure 6(b) | mg/L (wat) | [19] | |

| NO3− | 0.01 | mmol/cm3 (wat) | [5] | |

| NH4+ | 0.09 | mmol/cm3 (wat) | [5] | |

| PO4−P | Figure 6(b) | mg/L (wat) | [24] | |

| Mn2+ | 0 | mmol/cm3 (wat) | [5] | |

| Fe2+ | 0 | mmol/cm3 (wat) | [5] | |

| reaction rate (R22) | 2.5 × 10−9 | /s | ||

| water temperature | Figure 6(b) | ℃ | [19] | |

| Parameter | Value | Unit | Source* | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| reaction rate | (R23) | 2.5 × 10−9 | µM/s | - |

| (R24) | 2.5 × 10−8 | µM/s | - | |

| water temperature | (Jun) | 20.3 | ℃ | [9,10] |

| (Jul) | 21.7 | ℃ | [9,10] | |

| (Aug) | 25.7 | ℃ | [9,10] | |

| (Sep) | 24.0 | ℃ | [9,10] | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).