Submitted:

07 June 2023

Posted:

08 June 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Design

2.2. Sample and Setting

2.4. Instrument

2.5. Data collection

2.6. Ethical Considerations

2.7. Data analysis

3. Results

3.1. Sample characteristic

3.2. Front-of-pack nutrition labelling systems knowledge and suggestions for improvement

3.3. Features and functions of front-of-pack nutrition labelling system vs. Nutri-Score labelling system

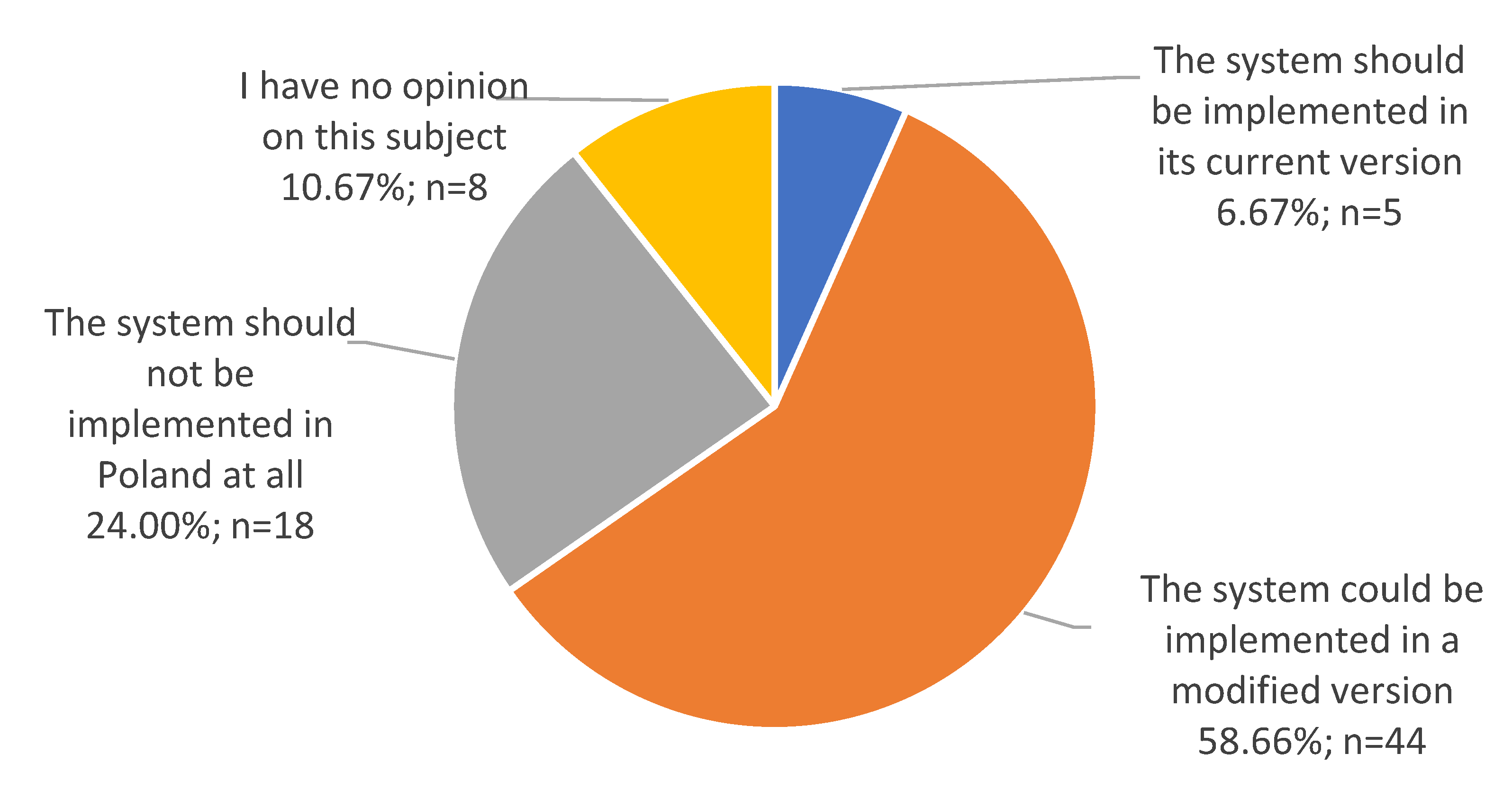

3.4. Implementation of the front-of-pack nutrition labelling system

4. Discussion

4.1. Current food labelling and prospects for development

4.2. Key features of FOPL vs. Nutri-Score system

4.3. Positive features of the Nutri-Score system in light of the desirable characteristics of FOPL

4.4. Features of an ideal FOPL that the Nutri-Score does not meet

4.5. Implementation of the front-of-pack nutrition labelling system

5. Limitations

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Juruć, A. Psychologia Odchudzania. In Psychodietetyka; Brytek-Matera, A., Ed.; PZWL: Warsaw, 2020; pp. 196–212. [Google Scholar]

- Temple, N.J.; Fraser, J. Food labels: a critical assessment. Nutrition 2014, 30, 257–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cannoosamy, K.; Pugo-Gunsam, P.; Jeewon, R. Consumer knowledge and attitudes toward nutritional labels. J Nutr Educ Behav 2014, 46, 334–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prieto-Castillo, L.; Royo-Bordonada, M.A.; Moya-Geromini, A. Information search behaviour, understanding and use of nutrition labeling by residents of Madrid, Spain. Public Health 2015, 129, 226–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Braesco, V.; Drewnowski, A. Are Front-of-Pack Nutrition Labels Influencing Food Choices and Purchases, Diet Quality, and Modeled Health Outcomes? A Narrative Review of Four Systems. Nutrients 2023, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ikonen, I.; Sotgiu, F.; Aydinli, A.; Verlegh, P.W.J. Consumer effects of front-of-package nutrition labeling: an interdisciplinary meta-analysis. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science 2020, 48, 360–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. WHO State of Play of WHO Guidance on Front-of-the-Pack Labelling. Available online: https://www.who.int/news/item/27-09-2021-state-of-play-of-who-guidance-on-front-of-the-pack-labelling (accessed on 7 June 2023).

- Croker, H.; Packer, J.; Russell, S.J.; Stansfield, C.; Viner, R.M. Front of pack nutritional labelling schemes: a systematic review and meta-analysis of recent evidence relating to objectively measured consumption and purchasing. J Hum Nutr Diet 2020, 33, 518–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feteira-Santos, R.; Fernandes, J.; Virgolino, A.; Alarcão, V.; Sena, C.; Vieira, C.P.; Gregório, M.J.; Nogueira, P.; Costa, A.; Graça, P.; et al. Effectiveness of interpretive front-of-pack nutritional labelling schemes on the promotion of healthier food choices: a systematic review. Int J Evid Based Healthc 2020, 18, 24–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Julia, C.; Hercberg, S.; Organization, W.H. Development of a new front-of-pack nutrition label in France: the five-colour Nutri-Score. Public health panorama 2017, 3, 712–725. [Google Scholar]

- Scientific Committee of the Nutri-Score. Update of the Nutri-Score Algorithm - Yearly report from the Scientific Committee of the Nutri -Score. Available online: https://sante.gouv.fr/IMG/pdf/annual_report_2021.pdf (accessed on 7 June 2023).

- Hercberg, S.; Touvier, M.; Salas-Salvado, J.; On Behalf Of The Group Of European Scientists Supporting The Implementation Of Nutri-Score In, E. The Nutri-Score nutrition label. Int J Vitam Nutr Res 2021. [CrossRef]

- Donat-Vargas, C.; Sandoval-Insausti, H.; Rey-García, J.; Ramón Banegas, J.; Rodríguez-Artalejo, F.; Guallar-Castillón, P. Five-color Nutri-Score labeling and mortality risk in a nationwide, population-based cohort in Spain: the Study on Nutrition and Cardiovascular Risk in Spain (ENRICA). Am J Clin Nutr 2021, 113, 1301–1311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dréano-Trécant, L.; Egnell, M.; Hercberg, S.; Galan, P.; Soudon, J.; Fialon, M.; Touvier, M.; Kesse-Guyot, E.; Julia, C. Performance of the Front-of-Pack Nutrition Label Nutri-Score to Discriminate the Nutritional Quality of Foods Products: A Comparative Study across 8 European Countries. Nutrients 2020, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Finkelstein, E.A.; Ang, F.J.L.; Doble, B.; Wong, W.H.M.; van Dam, R.M. A Randomized Controlled Trial Evaluating the Relative Effectiveness of the Multiple Traffic Light and Nutri-Score Front of Package Nutrition Labels. Nutrients 2019, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Włodarek, D.; Dobrowolski, H. Fantastic Foods and Where to Find Them-Advantages and Disadvantages of Nutri-Score in the Search for Healthier Food. Nutrients 2022, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Romero Ferreiro, C.; Lora Pablos, D.; Gómez de la Cámara, A. Two Dimensions of Nutritional Value: Nutri-Score and NOVA. Nutrients 2021, 13, 2783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peters, S.; Verhagen, H. An Evaluation of the Nutri-Score System along the Reasoning for Scientific Substantiation of Health Claims in the EU-A Narrative Review. Foods 2022, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Folkvord, F.; Bergmans, N.; Pabian, S. The effect of the nutri-score label on consumer’s attitudes, taste perception and purchase intention: An experimental pilot study. Food Quality and Preference 2021, 94, 104303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chouraqui, J.P.; Dupont, C.; Briend, A.; Darmaun, D.; Peretti, N.; Bocquet, A.; Chalumeau, M.; De Luca, A.; Feillet, F.; Frelut, M.L.; et al. Nutri-Score: Its Benefits and Limitations in Children's Feeding. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 2023, 76, e46–e60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Turck, D.; Bohn, T.; Castenmiller, J.; de Henauw, S.; Hirsch-Ernst, K.I.; Knutsen, H.K.; Maciuk, A.; Mangelsdorf, I.; McArdle, H.J.; Naska, A.; et al. Scientific advice related to nutrient profiling for the development of harmonised mandatory front-of-pack nutrition labelling and the setting of nutrient profiles for restricting nutrition and health claims on foods. Efsa j 2022, 20, e07259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schünemann, H.J.; Zhang, Y.; Oxman, A.D. Distinguishing opinion from evidence in guidelines. Bmj 2019, 366, l4606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Parliament and of the Council. The Provision of Food Information to Consumers. 1169/2011 2011, 18–63.

- Głąbska, D.; Włodarek, D. Minerals: Potassium. In Contemporary diet therapy (in Polish: Współczesna Dietoterapia); Lange, E., Włodarek, D., Eds.; PZWL Wydawnictwo Lekarskie: Warsaw, 2023; pp. 143–146. [Google Scholar]

- Weaver, C.M. Potassium and health. Adv Nutr 2013, 4, 368s–377s. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Opazo, M.C.; Coronado-Arrázola, I.; Vallejos, O.P.; Moreno-Reyes, R.; Fardella, C.; Mosso, L.; Kalergis, A.M.; Bueno, S.M.; Riedel, C.A. The impact of the micronutrient iodine in health and diseases. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr 2022, 62, 1466–1479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nairz, M.; Weiss, G. Iron in health and disease. Mol Aspects Med 2020, 75, 100906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cashman, K.D. Calcium and vitamin D. In Proceedings of the Dietary Supplements and Health: Novartis Foundation Symposium 282; 2007; pp. 123–142. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, H.; Chen, W.; Li, D.; Yin, X.; Zhang, X.; Olsen, N.; Zheng, S.G. Vitamin D and chronic diseases. Aging and Disease 2017, 8, 346–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ebara, S. Nutritional role of folate. Congenit Anom (Kyoto) 2017, 57, 138–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Whole Grain Initiative. Food Policy Working Group Open Letter on the Inclusion of Whole Grain in the Proposed Harmonised Mandatory Front-of-Pack Nutrition Labelling for the EU. Available online: https://www.safefoodadvocacy.eu/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/WGI-Open-Letter.pdf (accessed on 7 June 2023).

- Kissock, K.R.; Vieux, F.; Mathias, K.C.; Drewnowski, A.; Seal, C.J.; Masset, G.; Smith, J.; Mejborn, H.; McKeown, N.M.; Beck, E.J. Aligning nutrient profiling with dietary guidelines: modifying the Nutri-Score algorithm to include whole grains. Eur J Nutr 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oteng, A.B.; Kersten, S. Mechanisms of Action of trans Fatty Acids. Adv Nutr 2020, 11, 697–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, B.; Gan, L.; Graubard, B.I.; Männistö, S.; Albanes, D.; Huang, J. Associations of Dietary Cholesterol, Serum Cholesterol, and Egg Consumption With Overall and Cause-Specific Mortality: Systematic Review and Updated Meta-Analysis. Circulation 2022, 145, 1506–1520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fialon, M.; Salas-Salvadó, J.; Babio, N.; Touvier, M.; Hercberg, S.; Galan, P. Is FOP Nutrition Label Nutri-Score Well Understood by Consumers When Comparing the Nutritional Quality of Added Fats, and Does It Negatively Impact the Image of Olive Oil? Foods 2021, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ter Borg, S.; Steenbergen, E.; Milder, I.E.J.; Temme, E.H.M. Evaluation of Nutri-Score in Relation to Dietary Guidelines and Food Reformulation in The Netherlands. Nutrients 2021, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Szabo de Edelenyi, F.; Egnell, M.; Galan, P.; Druesne-Pecollo, N.; Hercberg, S.; Julia, C. Ability of the Nutri-Score front-of-pack nutrition label to discriminate the nutritional quality of foods in the German food market and consistency with nutritional recommendations. Arch Public Health 2019, 77, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, M.; Matias, F.; Fontes, T.; Bento, A.C.; Pires, M.J.; Nascimento, A.; Santiago, S.; Castanheira, I.; Rito, A.I.; Loureiro, I.; et al. Nutritional quality of foods consumed by the Portuguese population according to the Nutri-Score and consistency with nutritional recommendations. Journal of Food Composition and Analysis 2023, 120, 105338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kontopoulou, L.; Karpetas, G.E.; Kotsiou, O.S.; Fradelos, E.C.; Papathanasiou, I.V.; Malli, F.; Papagiannis, D.; Mantzaris, D.C.; Julia, C.; Hercberg, S.; et al. Guideline Daily Amounts Versus Nutri-Score Labeling: Perceptions of Greek Consumers About Front-of-Pack Label. Cureus 2022, 14, e32198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savov, R.; Tkáč, F.; Chebeň, J.; Kozáková, J.; Berčík, J. Impact of different FOPL systems (Nutri-Score vs Nutrinform) on consumer behaviour: case study of the Slovak republic. Amfiteatru Economic 2022, 24, 797–816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hercberg, S.; Galan, P.; Touvier, M. European JRC Report: One More Stone for the (Scientific) Building of Nutri-Score. Ann Nutr Metab 2023, 79, 3–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goiana-da-Silva, F.; Cruz, E.S.D.; Nobre-da-Costa, C.; Nunes, A.M.; Fialon, M.; Egnell, M.; Galan, P.; Julia, C.; Talati, Z.; Pettigrew, S.; et al. Nutri-Score: The Most Efficient Front-of-Pack Nutrition Label to Inform Portuguese Consumers on the Nutritional Quality of Foods and Help Them Identify Healthier Options in Purchasing Situations. Nutrients 2021, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguenaou, H.; El Ammari, L.; Bigdeli, M.; El Hajjab, A.; Lahmam, H.; Labzizi, S.; Gamih, H.; Talouizte, A.; Serbouti, C.; El Kari, K.; et al. Comparison of appropriateness of Nutri-Score and other front-of-pack nutrition labels across a group of Moroccan consumers: awareness, understanding and food choices. Arch Public Health 2021, 79, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marczuk, L.; Möser, A.; Teuber, R. The Nutri-Score as an extended nutrition labeling model in food retailing. A stocktaking. Ernahrungs Umschau 2021, 191–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egnell, M.; Galan, P.; Farpour-Lambert, N.J.; Talati, Z.; Pettigrew, S.; Hercberg, S.; Julia, C. Compared to other front-of-pack nutrition labels, the Nutri-Score emerged as the most efficient to inform Swiss consumers on the nutritional quality of food products. PloS one 2020, 15, e0228179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Julia, C.; Arnault, N.; Agaësse, C.; Fialon, M.; Deschasaux-Tanguy, M.; Andreeva, V.A.; Fezeu, L.K.; Kesse-Guyot, E.; Touvier, M.; Galan, P.; et al. Impact of the Front-of-Pack Label Nutri-Score on the Nutritional Quality of Food Choices in a Quasi-Experimental Trial in Catering. Nutrients 2021, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egnell, M.; Talati, Z.; Hercberg, S.; Pettigrew, S.; Julia, C. Objective Understanding of Front-of-Package Nutrition Labels: An International Comparative Experimental Study across 12 Countries. Nutrients 2018, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pivk Kupirovič, U.; Hristov, H.; Hribar, M.; Lavriša, Ž.; Pravst, I. Facilitating Consumers Choice of Healthier Foods: A Comparison of Different Front-of-Package Labelling Schemes Using Slovenian Food Supply Database. Foods 2020, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hau, R.C.; Lange, K.W. Can the 5-colour nutrition label “Nutri-Score” improve the health value of food? Journal of Future Foods 2023, 3, 306–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carruba, M.O.; Caretto, A.; De Lorenzo, A.; Fatati, G.; Ghiselli, A.; Lucchin, L.; Maffeis, C.; Malavazos, A.; Malfi, G.; Riva, E.; et al. Front-of-pack (FOP) labelling systems to improve the quality of nutrition information to prevent obesity: NutrInform Battery vs Nutri-Score. Eat Weight Disord 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Srour, B.; Fezeu, L.K.; Kesse-Guyot, E.; Allès, B.; Méjean, C.; Andrianasolo, R.M.; Chazelas, E.; Deschasaux, M.; Hercberg, S.; Galan, P.; et al. Ultra-processed food intake and risk of cardiovascular disease: prospective cohort study (NutriNet-Santé). Bmj 2019, 365, l1451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schnabel, L.; Buscail, C.; Sabate, J.M.; Bouchoucha, M.; Kesse-Guyot, E.; Allès, B.; Touvier, M.; Monteiro, C.A.; Hercberg, S.; Benamouzig, R.; et al. Association Between Ultra-Processed Food Consumption and Functional Gastrointestinal Disorders: Results From the French NutriNet-Santé Cohort. The American journal of gastroenterology 2018, 113, 1217–1228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schnabel, L.; Kesse-Guyot, E.; Allès, B.; Touvier, M.; Srour, B.; Hercberg, S.; Buscail, C.; Julia, C. Association Between Ultraprocessed Food Consumption and Risk of Mortality Among Middle-aged Adults in France. JAMA Intern Med 2019, 179, 490–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Srour, B.; Hercberg, S.; Galan, P.; Monteiro, C.A.; Szabo de Edelenyi, F.; Bourhis, L.; Fialon, M.; Sarda, B.; Druesne-Pecollo, N.; Esseddik, Y. Effect of a new graphically modified Nutri-Score on the objective understanding of foods' nutrient profile and ultra-processing: a randomised controlled trial. medRxiv 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braesco, V.; Ros, E.; Govindji, A.; Bianchi, C.; Becqueriaux, L.; Quick, B. A Slight Adjustment of the Nutri-Score Nutrient Profiling System Could Help to Better Reflect the European Dietary Guidelines Regarding Nuts. Nutrients 2022, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willett, W.; Rockström, J.; Loken, B.; Springmann, M.; Lang, T.; Vermeulen, S.; Garnett, T.; Tilman, D.; DeClerck, F.; Wood, A.; et al. Food in the Anthropocene: the EAT-Lancet Commission on healthy diets from sustainable food systems. Lancet 2019, 393, 447–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scientific Committee of the Nutri-Score. Update Report from the Scientific Committee of the Nutri-Score 2022. Available online: https://sante.gouv.fr/IMG/pdf/maj__rapport_nutri-score_rapport__algorithme_2022_.pdf (accessed on 7 June 2023).

- Pointke, M.; Pawelzik, E. Plant-Based Alternative Products: Are They Healthy Alternatives? Micro- and Macronutrients and Nutritional Scoring. Nutrients 2022, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Bauw, M.; Matthys, C.; Poppe, V.; Franssens, S.; Vranken, L. A combined Nutri-Score and ‘Eco-Score’ approach for more nutritious and more environmentally friendly food choices? Evidence from a consumer experiment in Belgium. Food Quality and Preference 2021, 93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lemken, D.; Zühlsdorf, A.; Spiller, A. Improving Consumers’ Understanding and Use of Carbon Footprint Labels on Food: Proposal for a Climate Score Label. EuroChoices 2021, 20, 23–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Temple, N.J. Front-of-package food labels: A narrative review. Appetite 2020, 144, 104485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dereń, K.; Dembiński, Ł.; Wyszyńska, J.; Mazur, A.; Weghuber, D.; Łuszczki, E.; Hadjipanayis, A.; Koletzko, B. Front-Of-Pack Nutrition Labelling: A Position Statement of the European Academy of Paediatrics and the European Childhood Obesity Group. Ann Nutr Metab 2021, 77, 23–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| n | % | |

|---|---|---|

| Workplace | ||

| Medical university | 27 | 36 |

| Agricultural university | 26 | 35 |

| Other university | 9 | 12 |

| Scientific research institute | 9 | 12 |

| Hospital/clinic/surgery | 12 | 16 |

| Nature of the work | ||

| Conducting research on nutritional labelling of products | 11 | 15 |

| Conducting classes with students (lectures, seminars, exercises) on nutritional labelling of products | 41 | 55 |

| Conducting workshops/training sessions on nutrition labelling issues | 18 | 24 |

| Providing dietary counselling | 26 | 35 |

| Newly designed FOPL | Nutri-Score System | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Feature/function * | M±SD (95%C.I.) |

Mdn | Meets [%] (95%C.I.) |

Does not meet [%] (95%C.I.) | No opinion [%] (95%C.I.) |

| Clear, understandable, simple | 4.92±0.27 (4.86; 4.98) |

5 | 48.0 (37.3; 58.7) |

25.3 (16.0; 36.0) |

26.7 (17.3; 36.0) |

| Compliant with healthy eating recommendations | 4.91±0.29 (4.84; 4.97) |

5 | 36.0 (25.3; 46.7) |

34.7 (25.3; 46.7) |

29.3 (20.0; 40.0) |

| Allows an objective comparison between products from the same product group (e.g., cereals) offered by different manufacturers | 4.59±0.50 (4.47; 4.70) |

5 | 46.7 (34.7; 57.3) |

28.0 (18.7; 38.7) |

25.3 (14.7; 36.0) |

| Helpful for nutrition education | 4.57±0.57 (4.44; 4.71) |

5 | 34.7 (24.0; 45.3) |

28.0 (18.7; 38.7) |

37.3 (26.7; 49.3) |

| Facilitates the composition of a balanced diet | 4.53±0.55 (4.41; 4.66) |

5 | 5.3 (1.3; 10.7) |

80.0 (70.7; 89.3) |

14.7 (6.7; 22.7) |

| Gives an overall assessment of the nutritional value | 4.33±0.70 (4.17; 4.50) |

4 | 65.3 (54.7; 76.0) |

8.0 (2.7; 13.3) |

26.7 (17.3; 37.3) |

| Applicable to all product groups | 4.32±0.70 (4.16; 4.48) |

4 | 2.7 (0.0; 6.7) |

57.3 (46.7; 68.0) |

40.0 (29.3; 52.0) |

| Takes into account the degree of processing of the product | 4.23±0.86 (4.03; 4.43) |

4 | 1.3 (0.0; 4.0) |

76.0 (66.7; 85.3) |

22.7 (13.3; 32.0) |

| Encourages a thorough understanding of the composition and nutritional value of the product | 4.20±0.70 (4.04; 4.36) |

4 | 29.3 (18.7; 40.0) |

38.7 (26.7; 50.7) |

32.0 (20.0; 42.7) |

| Pushes companies to improve their recipes from a nutritional perspective without having the main objective of obtaining a more favourable rating under the labelling scheme | 4.19±0.82 (4.00; 4.37) |

4 | 46.7 (36.0; 58.7) |

24.0 (14.7; 33.3) |

29.3 (18.7; 40.0) |

| Allows the customer to make a quick purchasing decision | 4.17±0.79 (3.99; 4.36) |

4 | 81.3 (72.0; 90.7) |

6.7 (1.3; 13.3) |

12.0 (5.3; 20.0) |

| Takes into account the full nutritional value of the products (macronutrients, minerals, vitamins, bioactive compounds, etc.) | 4.08±0.94 (3.86; 4.30) |

4 | 2.7 (0.0; 6.7) |

74.7 (64.0; 84.0) |

22.7 (13.3; 32.0) |

| Universal for all EU countries | 4.07±0.86 (3.87; 4.26) |

4 | 32.0 (22.7; 44.0) |

33.3 (22.7; 44.0) |

34.7 (22.7; 45.3) |

| Does not depreciate regional, traditional and organic products | 4.07±0.78 (3.89; 4.25) |

4 | 21.3 (12.0; 32.0) |

30.7 (20.0; 41.3) |

48.0 (36.0; 60.0) |

| Allows objective comparisons between different product groups (e.g., a group of sweets to a group of cheeses) | 3.76±1.18 (3.49; 4.03) |

4 | 16.0 (8.0; 25.3) |

46.7 (36.0; 58.7) |

37.3 (26.7; 48.0) |

| Does not depreciate any product group | 3.57±1.07 (3.33; 3.82) |

4 | 4.0 (0.0; 9.3) |

64.0 (52.0; 74.7) |

32.0 (21.3; 44.0) |

| Includes the carbon footprint | 3.20±0.97 (2.98; 3.42) |

3 | 5.3 (1.3; 10.7) |

54.7 (42.7; 66.6) |

40.0 (29.3; 52.0) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).